Abstract

Diseases of the liver related to metabolic syndrome have emerged as the most common and undertreated hepatic ailments. The cause of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the aberrant accumulation of lipid in hepatocytes, though the mechanisms whereby this leads to hepatocyte dysfunction, death, and hepatic fibrosis are still unclear. Insulin-sensitizing thiazolidinediones have shown efficacy in treating nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), but their widespread use is constrained by dose-limiting side effects thought to be due to activation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ). We sought to determine whether a next-generation thiazolidinedione with markedly diminished ability to activate PPARγ (MSDC-0602) would retain its efficacy for treating NASH in a rodent model. We also determined whether some or all of these beneficial effects would be mediated via an inhibitory interaction with the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier 2 (MPC2), which was recently identified as a mitochondrial binding site for thiazolidinediones, including MSDC-0602. We found that MSDC-0602 prevented and reversed liver fibrosis and suppressed expression of markers of stellate cell activation in livers of mice fed a diet rich in trans-fatty acids, fructose, and cholesterol. Moreover, mice with liver-specific deletion of MPC2 were protected from development of NASH on this diet. Finally, MSDC-0602 directly reduced hepatic stellate cell activation in vitro, and MSDC-0602 treatment or hepatocyte MPC2 deletion also limited stellate cell activation indirectly by affecting secretion of exosomes from hepatocytes.

Conclusion

Collectively, these data demonstrate the effectiveness of MSDC-0602 for attenuating NASH in a rodent model and suggest that targeting hepatic MPC2 may be an effective strategy for pharmacologic development.

Keywords: liver, NASH, thiazolidinedione, fibrosis, MPC

The epidemic of obesity has dramatically increased the incidence of a variety of related metabolic diseases, including nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (1). NAFLD encompasses a spectrum of disease from isolated steatosis to steatohepatitis (NASH), which includes steatosis with inflammation, hepatocyte ballooning injury, and fibrosis (2). NASH is a leading cause of cirrhosis and liver failure (2), increases risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (3), and is currently the second leading indication for liver transplantation in the United States (4, 5). Fibrosis, and thus parenchymal remodeling, is the best predictor of progression, need for liver transplant, and mortality (6–8). Despite the prevalence of NAFLD and the related public health problems, there are currently no approved medical therapies beyond weight loss and exercise (9, 10), which are difficult to achieve and maintain (11)

Pioglitazone (ActosR) and rosiglitazone (AvandiaR) have been used clinically as insulin sensitizing agents and evaluated for their effects on NASH in experimental models and clinical trials. Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) reduced liver injury, lowered circulating transaminases, and improved histologic measures of NASH (12–17). Recently, pioglitazone was shown to reverse hepatic fibrosis and other NASH measures in an 18 month trial (18). TZDs elicit many of their effects by serving as activating ligands for the nuclear receptor, the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ)(19). While these drugs are clearly effective insulin sensitizers and anti-inflammatories, their use is limited by a number of known side effects that are also mediated through activation of PPARγ (20). Recently, we have postulated that some of the beneficial effects of TZDs might be separable from their ability to activate PPARγ and have developed “PPARγ-sparing” TZDs (MSDC-0602 and MSDC-0160) with limited ability to bind and activate PPARγ, but that retain the beneficial metabolic effects (21, 22), even in hepatocytes with complete deletion of PPARγ (21).

Thiazolidinediones also bind to the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC) at physiological concentrations (23, 24) and acutely suppress pyruvate metabolism in isolated mitochondria in an MPC-dependent manner (24, 25). The MPC comprises two proteins, MPC1 and MPC2, that form a carrier complex in the inner mitochondrial membrane (26). Transport into the mitochondrial matrix is required for pyruvate metabolism and is critical for a number of metabolic pathways. The effects of MSDC-0602 on reducing hepatocyte glucose production in vitro were abolished in MPC2-deficient hepatocytes (24), suggesting that at least some of the beneficial metabolic effects of this PPARγ-sparing TZD are mediated via an interaction with MPC2.

The objective of the present study was to determine whether MSDC-0602 might have therapeutic effects in an experimental model of NASH and, if so, to define whether binding to the MPC was involved. We found that MSDC-0602 treatment reduced histologic fibrosis, toxic lipid accumulation, and molecular markers of hepatic stellate cell activation in mice. We showed that these effects were dependent on MPC2 and that hepatocyte-specific deletion of MPC2 by itself was protective from the development of liver injury. Finally, we show that MSDC-0602 directly prevents stellate cell activation in vitro and also acts indirectly to regulate activation by modulating exosome release by hepatocytes in an MPC2-dependent manner. These data demonstrate the effectiveness of MSDC-0602 at reducing liver fibrosis and stellate cell activation through effects on MPC2 and suggest that targeting the MPC is a potential therapeutic avenue for treating NASH.

Experimental Procedures

Animal Studies

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Studies Committee of the Washington University School of Medicine and comply with the criteria outlined in the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” by the National Academy of Sciences. Wild-type C57BL6/J male mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. LS-Mpc2−/− mice in the C57BL6/J background have been previously described (24). Littermate mice not expressing Cre (fl/fl mice) were used as controls. All diet studies were initiated in 6–9 week old mice.

Male mice were placed on a diet enriched with fat (40% Kcal, mainly trans-fat; trans oleic and trans linoleic acids), fructose (20% Kcal), and cholesterol (2% w/w) (HTF-C diet) (D09100301 Research Diets Inc.) described to cause hepatic injury and inflammation (27). Control mice were fed a matched low fat (10% Kcal) control diet that was not supplemented with fructose or cholesterol (LF diet) (D09100304, Research Diets Inc.) (28). After remaining on the designated diets for 4 weeks, a subset of randomly-selected HTF-C-fed mice were placed on HTF-C diet containing MSDC-0602 potassium salt (331 ppm) for the remaining 12 weeks prior to sacrifice. This dose was chosen based on previous studies showing that 331 ppm in diet resulted in a concentration of 2–5 µM MSDC-0602 in the blood of obese mice (unpublished observation), is effective at insulin sensitizing (21), and compares with plasma exposures examined in clinical trials (29). In a second trial, diet feeding was for a total of 19 weeks, and a fourth group of mice were placed on plain HTF-C diet for 16 weeks, and then switched to HTF-C +331 ppm MSDC-0602 for the remaining 3 weeks.

Body weight was checked weekly. Mice were sacrificed and tissues were harvested after a 4 h fast. Liver, gonadal, subcutaneous, and intrascapular brown fat tissue samples were weighed, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

Materials

Production scale synthesis of all TZDs for mouse studies was conducted by USV (Mumbai, India) and TZDs were incorporated into the experimental diets by Research Diets Inc.

Plasma and liver chemistries

Plasma ALT and AST were measured by kinetic absorbance assays (Teco Diagnostics). Liver triglyceride was measured by solubilizing 100 mg liver tissue in saline and solubilizing lipid with 0.5% sodium deoxycholate and determined by colorimetric assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Histologic Analyses

Liver sections were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 h and then embedded in paraffin blocks. Sections were cut and stained for either Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) or Mason’s trichrome stains. Livers were analyzed by a liver pathologist (either E.M.B. or I.N.), blinded to treatment group and genotype. Steatosis, inflammation, hepatocyte ballooning, and fibrosis were scored according to NAFLD activity score (NAS) and fibrosis scoring (30).

Mass Spectrometry and Lipid Quantification

Oxidative stress markers (oxysterols and organic aldehydes) were extracted with methanol from homogenized liver tissues and quantified by a liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS; Shimadzu, and Applied Biosystems) system using deuterated compounds (In House Preparation and Cayman Chemical) as internal standards and methods as previously described (31). Protein concentrations in the liver homogenates were also determined by bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA; Pierce) for normalization.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the RNAzol method (RNA-Bee, Tel-Test). cDNA was made by use of a high capacity reverse transcription kit for liver tissues (Applied Biosystems) and a Vilo reverse transcription kit for isolated stellate cells (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was performed using an ABI PRISM 7500 sequence detection system and a SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems). Arbitrary units of target mRNA were corrected by measuring the levels of 36B4 mRNA. Oligonucleotide sequences are available upon request.

REporter Sensitive to PYRuvate (RESPYR)

Potential drug interactions with the MPC were assessed using a BRET-based MPC activity system called RESPYR (32, 33). Briefly, previously described MPC2-RLuc8 and MPC1-Venus fusion proteins were stably expressed in HEK293 cells using lentiviral transduction. Assays were performed as published (32, 33), with the addition of drug compounds after baseline readings in the absence of pyruvate. Bioluminescence and energy transfer were assessed using a kinetic plate reader (Biotek Synergy 2) at 460 ± 40 nm and 528 ± 20 nm at 37°C.

Stellate cell isolation and culture

Primary mouse hepatic stellate cells were isolated by collagenase perfusion during hepatocyte isolations (24). Stellate cells were then purified by density gradient centrifugation using Optiprep (Sigma) as previously described (34). Cells were seeded onto standard 6-well tissue culture dishes and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1X Pen/Strep. A subset of cells was harvested after 24 h to serve as quiescent control cells. All other cells were treated as indicated and harvested after 3–7 days (34).

Exosome isolation, western blotting, and stellate cell treatment

Plasma exosomes were enriched from frozen plasma collected at the end of the HTF-C diet feeding trials. 500µL of plasma was first defibrinated using purified thrombin, and then exosomes were purified using ExoQuick reagent (System Biosciences). For western blotting analysis, whole blood or plasma exosome samples were solubilized in HNET (25mM Hepes, 150mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1% TritonX–100) protein lysate buffer. 75µg of protein lysate were run down polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes. Membranes were then probed with primary antibodies for the vesicle marker flotillin-1 (1:500, Abcam ab50671) and the cell marker calnexin (1:1000, Abcam ab22595). Membranes were then probed with an Anti-Rabbit IRDye® 800CW secondary antibody (1:10,000, LI-COR) and blots were developed on an infrared Odyssey developer (LI-COR). For stellate cell treatments, exosome pellets were solubilized in 300µL PBS and day 2 stellate cell 6-well cultures were treated with either PBS vehicle control or exosomes for 24 hour before harvest for RNA analyses.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical comparisons were made using t-test or ANOVA where appropriate. All data unless specified are presented as mean ± SEM, with a statistically significant difference defined as p ≤ 0.05.

Results

MSDC-0602 improves liver injury induced by HTF-C feeding in mice

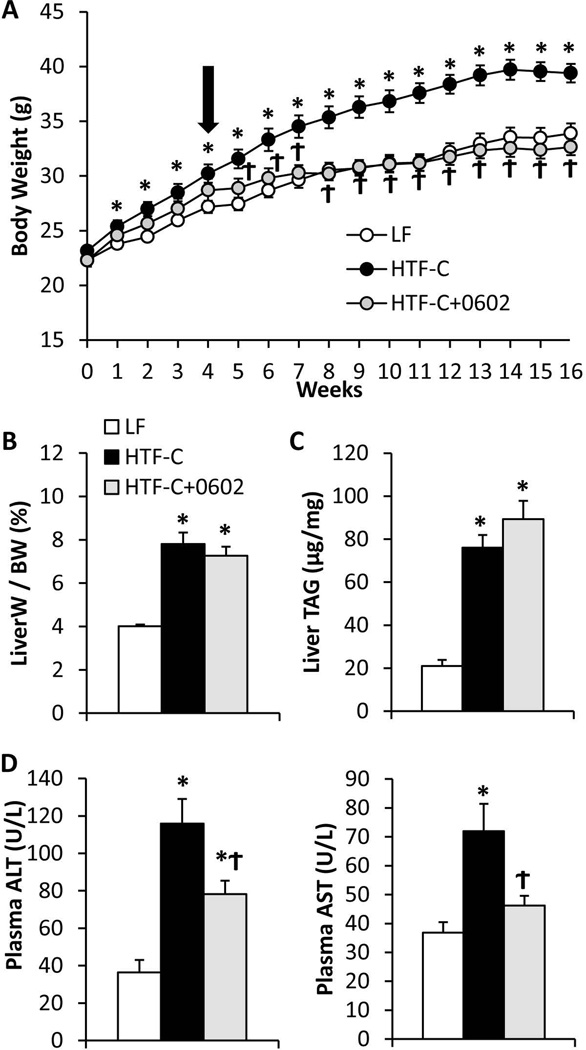

Diets containing high levels of trans-fat in the context of elevated fructose and/or cholesterol provoke liver injury and development of fibrosis in mice (27, 28, 35). We fed diet high in fat (including trans-fat), fructose, and cholesterol (HTF-C diet) to C57BL6/J mice for 16 weeks and evaluated hepatic steatosis and liver injury. Compared to a matched low fat (LF) control diet, the HTF-C diet induced significant weight gain (Figure 1A) and adiposity (Supplemental Figure 1A,B). HTF-C diet also caused an increase in the liver to body weight ratio (Figure 1B), and increased liver triglyceride content (Figure 1C). In a subset of mice, HTF-C diet was fed for 4 weeks, and then MSDC-0602 was added to the HTF-C diet for the remaining 12 weeks (HTF-C+0602). MSDC-0602 feeding suppressed body weight gain (Figure 1A) and adiposity (Supplemental Figure 1A,B) independently of changes in food intake (Supplemental Figure 1C). The attenuation in body weight gain and adiposity was correlated with a marked increase in the mass of the intrascapular brown adipose tissue (Supplemental Figure 1D), consistent with MSDC-0602 directly stimulating differentiation of brown adipocyte progenitor cells (23) and suggesting that increased energy expenditure explains the effects on body weight. However, this aspect of the phenotype was not explored further. MSDC-0602 did not reverse the effects of HTF-C on liver to body weight ratios (Figure 1B) or improve the hepatic triglyceride accumulation observed with HTF-C feeding (Figure 1C), allowing measurements of inflammation, hepatocyte ballooning, and fibrosis to be made in an unbiased manner.

Figure 1. MSDC-0602 prevents weight gain and increased circulating transaminases on HTF-C diet.

[A] Body weight gain by C57BL6/J mice on diets that were low fat (LF) or high in trans fatty acids, fructose, and cholesterol (HTF-C). After 4 weeks on HTF-C diet, some mice were switched to HTF-C diet containing MSDC-0602. [B] Liver weight to body weight ratio for mice fed LF, HTF-C, or HTF-C containing MSDC-0602 chow. [C] Liver triglyceride content of mice fed LF, HTF-C, or HTF-C containing MSDC-0602 chow. [D] Plasma ALT and AST concentrations of mice fed LF, HTF-C, or HTF-C containing MSDC-0602 chow. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM. N=10, * indicates p<0.05 vs LF-fed group. ϯ indicates p<0.05 vs HTF-C fed group.

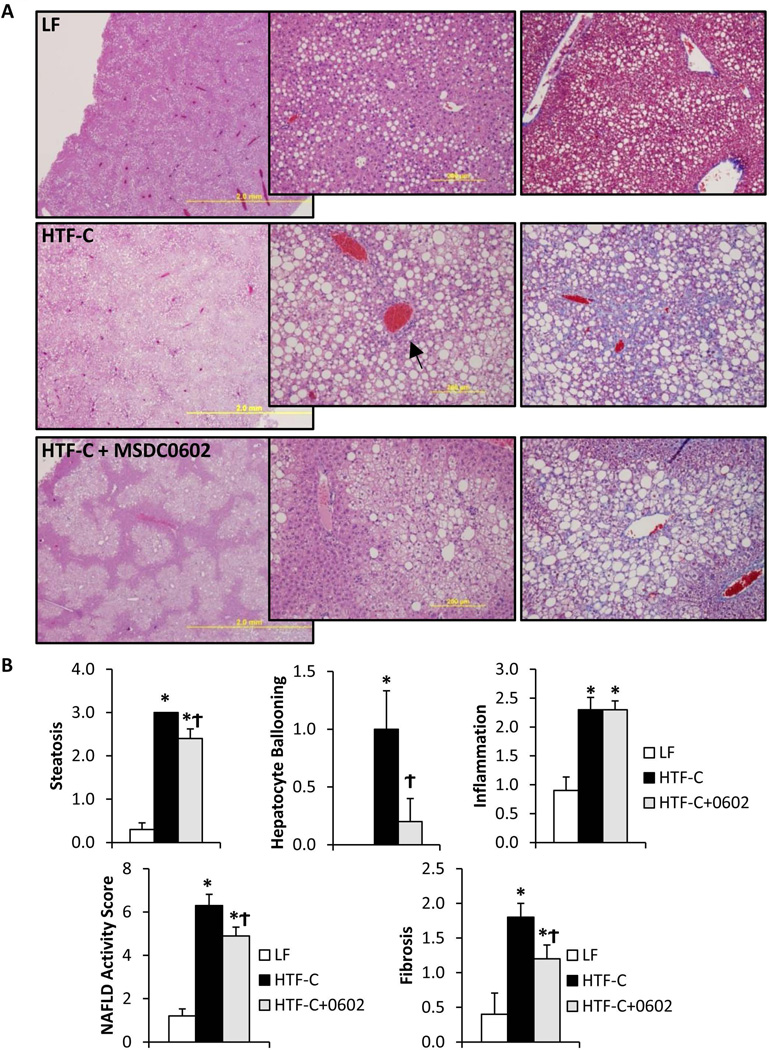

Plasma ALT and AST concentrations were markedly increased by HTF-C diet (Figure 1D). However, MSDC-0602 significantly improved plasma ALT and AST concentrations, suggesting decreased liver injury. Histologic evidence of steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning, and inflammatory cell infiltration was observed in HTF-C diet-fed livers (Figure 2A). Ductular reactions involving progenitor cells and matrix deposition were readily apparent in HTF-C livers (Figure 2A, arrow). Collagen or matrix deposition was also abundant in HTF-C livers (Figure 2A, arrowhead) and appeared reduced in livers of MSDC-0602-fed animals. When analyzed by a histopathologist blinded to treatment groups, the NAFLD Activity Score (NAS) (sum of steatosis + ballooning + inflammation) was significantly elevated by HTF-C diet, and reduced by MSDC-0602 (Figure 2B). Fibrosis scoring was also significantly elevated by HTF-C diet, and reduced by MSDC-0602 (Figure 2B). Interestingly, although triglyceride accumulation was not quantitatively affected (Figure 1C), treatment with MSDC-0602 restored characteristic zonality to lipid deposition with periportal zone 1 hepatocytes being spared from steatosis (Figure 2A). The mechanisms driving this effect can only be speculated upon; perhaps being related to greater drug effectiveness in zone 1 due to higher tissue perfusion, oxygen tension, and anabolic metabolism (36), or differences in lipid profiles (37) of periportal zone 1 hepatocytes. Additionally, expression of cytochrome P450 and other xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes is higher in perivenous zone 3 hepatocytes (36), suggesting greater drug metabolism and lower drug effectiveness in zone 3 hepatocytes. Of note, the appearance of the remaining zone 2/3 steatosis is not significantly altered, with most hepatocytes containing a mixture of micro and macrosteatosis.

Figure 2. Histologic markers of NASH in HTF-C-fed mice are improved by MSDC-0602 treatment.

[A] Representative H&E-stained liver sections from mice from each experimental group are shown. Magnification increases from left to right. [B] Liver NAFLD Activity Score (NAS) scoring (the sum of steatosis, ballooning, and inflammation scores) as well as fibrosis scoring was performed by a trained pathologist blinded to treatment group. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM. N=10, * indicates p<0.05 vs LF-fed group. ϯ indicates p<0.05 vs HTF-C fed group.

Liver samples were analyzed by mass spectrometry for lipid markers of oxidative stress. HTF-C diet caused elevated levels of oxysterols 7-keto-cholesterol and 3β,5α,6β-cholestantriol, as well as organic aldehydes hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) and hydroxyhexanol (4-HHE) (Figure 3A). MSDC-0602 feeding either tended to, or significantly reduced these lipid markers of oxidative stress. Lastly, liver gene expression markers of inflammatory cytokine production, macrophage infiltration, hepatic stellate cell activation, and fibrosis were also increased by HTF-C diet feeding (Figure 3B). MSDC-0602 treatment did not improve markers of inflammation or macrophage infiltration (Tnfa, Tgfb, Il1b, Cd68, and Thbs1). However, MSDC-0602 significantly improved markers of stellate cell activation, fibrosis, and extracellular matrix remodeling (Col1a1, Col3a1, Spp1, Timp1, Timp3, and Mmp2) (Figure 3B). These data strongly suggest that MSDC-0602 alleviates oxidative stress, stellate cell activation, and matrix deposition in mice fed an HTF-C diet.

Figure 3. Reduced oxidative damage and expression of markers of stellate cell activation after treatment with MSDC-0602.

[A] The graphs depict the liver content of toxic lipids and reactive nitrogen products in mice fed LF, HTF-C, or HTF-C containing MSDC-0602 chow. [B] The hepatic expression of indicated genes encoding proinflammatory cytokines, macrophage markers, and markers of stellate cell activation in mice fed LF, HTF-C, or HTF-C containing MSDC-0602 chow is shown. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM. N=10, * indicates p<0.05 vs LF-fed group. ϯ indicates p<0.05 vs HTF-C fed group.

MSDC-0602 reverses liver injury induced by HTF-C feeding

We also sought to determine whether MSDC-0602 could reverse, as opposed to prevent, diet-induced liver injury and stellate cell activation by beginning drug treatment after 16 weeks on diet, when liver injury and fibrosis is fully manifest. Switching HTF-C mice to HTF-C chow containing MSDC-0602 for 3 weeks beginning at 16 weeks caused significant weight loss (Figure 4A). Providing mice with chow containing MSDC-0602 starting at 4 weeks slightly reduced liver TAG content, while 3 weeks of MSDC-0602-containing diet had no effect on liver TAG (Figure 4B). However, both long-term and short-term MSDC-0602 treatment significantly reduced plasma ALT and AST concentrations (Figure 4C) and improved NAS and fibrosis scoring (Figure 4D,E). As observed in the previous trial, early switch to diet containing MSDC-0602 strongly reduced markers of stellate cell fibrogenesis (Figure 4F). Additionally, the 3 weeks of treatment with MSDC-0602 also significantly reduced all markers of stellate cell fibrogenesis and extracellular matrix regulation (Figure 4F).

Figure 4. MSDC-0602 can reverse liver injury after 16 weeks of HTF-C diet feeding.

[A] Body weight gain by C57BL6/J mice on diets that were low fat (LF) or high in trans fatty acids, fructose, and cholesterol (HTF-C). After 4 weeks on HTF-C diet, some mice were switched to HTF-C diet containing MSDC-0602. Another sub-group was switched to HTF-C diet containing MSDC-0602 after 16 weeks. [B] Liver triglyceride content of mice fed LF, HTF-C, or HTF-C containing MSDC-0602 chow. [C] Plasma ALT and AST concentrations of mice fed LF, HTF-C, or HTF-C containing MSDC-0602 chow. [D] Liver NAS scoring and [E] fibrosis scoring was performed by a trained pathologist blinded to treatment group. [F] Hepatic expression of indicated fibrotic, stellate cell activation, and extracellular matrix regulating genes. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM. N=7–9, except for n=6 per group in panel F. * indicates p<0.05 vs LF-fed group. ϯ indicates p<0.05 vs HTF-C fed group. 1 indicates p<0.05 comparing the MSDC-0602 @4 and @16 groups.

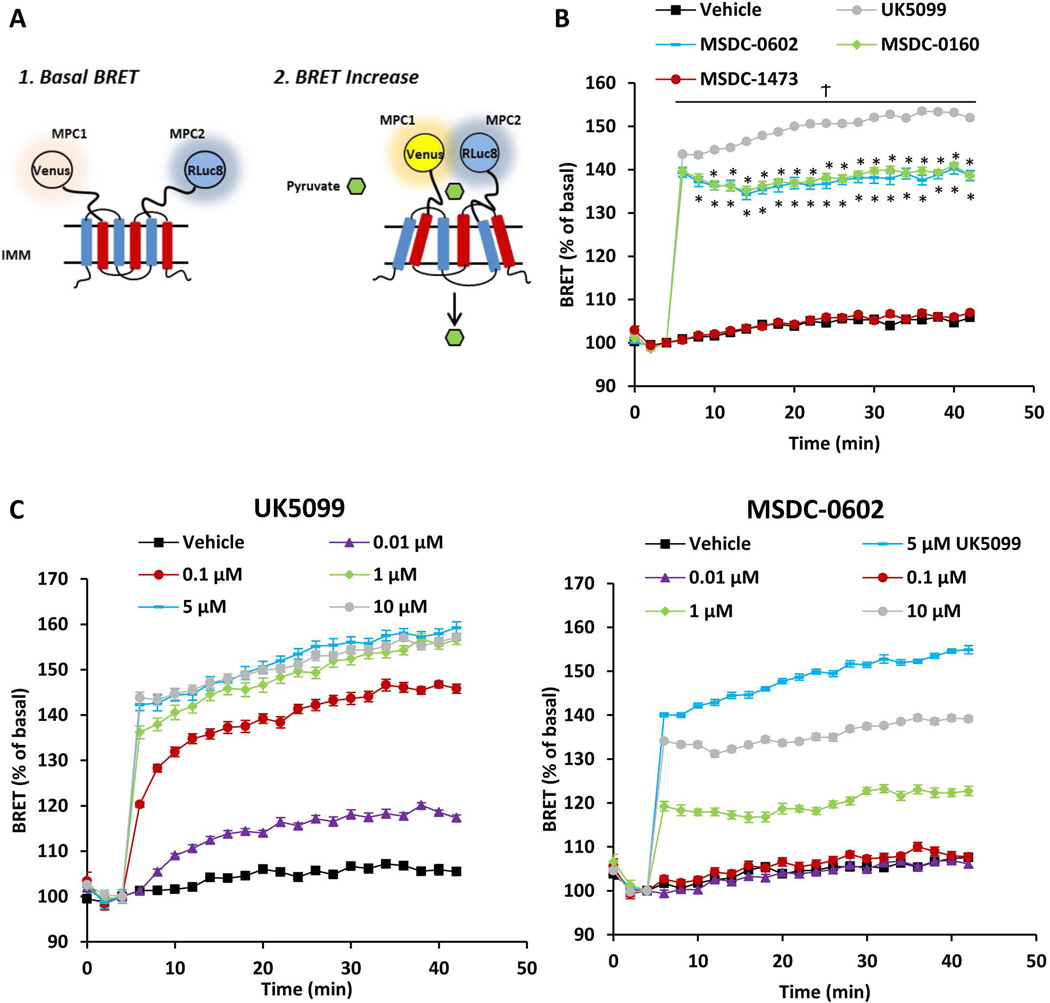

MSDC-0602 interacts with the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier

MSDC-0602 and other TZDs bind to the MPC complex and reduce flux through this carrier (24, 25). To demonstrate a direct interaction between MSDC-0602 and the MPC, we used the recently described REporter Sensitive to PYRuvate (RESPYR) system (32) (Figure 5A). Interaction with pyruvate, the substrate of the MPC, leads to a conformational change and an increase in energy transfer in this BRET-based sensor (32). Interestingly, a high-potency, irreversible MPC inhibitor (UK-5099) also produces a robust increase in RESPYR activity (Figure 5B). Similarly, addition of MSDC-0602 or MSDC-0160 provoked a significant increase in RESPYR activity (Figure 5B). We believe that these chemical MPC inhibitors result in increased BRET activity due to their interaction with the same binding pocket of the MPC as pyruvate, inducing a similar conformational change in the complex. In contrast, another TZD compound that lacks insulin-sensitizing properties (MSDC-1473)(23) fails to stimulate RESPYR activity (Figure 5B). Dose response curves demonstrated that MSDC-0602 was 100-fold less potent than UK-5099 and failed to elicit the same maximal increase in RESPYR activity (Figure 5C). These data are consistent with a direct interaction between MSDC-0602 and the MPC, though the affinity of binding and/or mechanism of interaction may be different than other traditional inhibitors.

Figure 5. MSDC-0602 stimulates the activity of a BRET-based biosensor of MPC activity.

[A] Schematic of RESPYR BRET assay. [B] BRET kinetics of HEK-293 cells expressing RLuc8 fused to MPC2 and Venus yellow fluorescent protein fused to MPC1. Cells were stimulated after 5 minutes with vehicle (DMSO), 5 µM UK-5099, 10 µM MSDC-0602, 10 µM MSDC-0160, or 10 µM MSDC-1473. [C] Graphs represent BRET activity in dose response studies conducted with UK-5099 and MSDC-0602. Data were analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA in Prism. Post Hoc analysis was performed using Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM. N=10, 2 independent experiments with 4–5 technical replicates per experiment.

Mice with liver-specific deletion of MPC2 are refractory to liver injury induced by HTF-C diet and the effects of MSDC-0602

To examine the effects of loss of MPC function on the response to HTF-C diet and MSDC-0602, we used previously-described mice with liver-specific deletion of MPC2 (24). There was no effect of this mouse genotype on weight gain on HTF-C diet and loss of MPC in the liver did not affect the ability of MSDC-0602 to suppress weight gain (Figure 6A). Loss of MPC activity in liver resulted in reduced circulating ALT and AST in HTF-C-fed mice and the ability of MSDC-0602 to reduce plasma transaminase activity was lost in liver MPC2 null mice. Similarly, fibrosis scoring and the expression of markers of stellate cell activation were also suppressed by genetic loss of MPC in liver and MSDC-0602 did not further repress the expression of these genes in LS-Mpc2−/− (Figure 6C,D). MSDC-0602 tended to reduce fibrosis scoring in the knockout. However, this was not significant (p=0.13). Interestingly, this improvement in hepatic fibrosis with genetic deletion of Mpc2 was despite no improvement in hepatic steatosis as liver triglyceride levels were unaltered (Figure 6E). Thus, both genetic deletion and pharmacologic inhibition of the MPC appear to improve hepatic fibrosis without significantly altering hepatic steatosis in this HTF-C diet-induced NASH model.

Figure 6. MPC2 deletion in hepatocytes protects mice from liver injury, fibrosis, and stellate cell activation.

[A] Body weight gain by WT and LS-Mpc2−/− mice on HTF-C diet. After 4 weeks on HTF-C diet, some mice were switched to HTF-C diet containing MSDC-0602. [B] Plasma ALT and AST concentrations of WT and LS-Mpc2−/− mice on HTF-C diet or HTF-C diet containing MSDC-0602. [C] Liver fibrosis scoring was performed by a trained pathologist blinded to treatment group. [D] The hepatic expression of indicated genes encoding markers of stellate cell activation in WT and LS-Mpc2−/− mice on HTF-C diet or HTF-C diet containing MSDC-0602 is shown. [E] Liver triglyceride content of WT and LS-Mpc2−/− mice fed HTF-C or HTF-C containing MSDC-0602 chow. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM. N=7–10, * indicates p<0.05 vs fl/fl HTF-C-fed group.

Direct and indirect effects of MSDC-0602 on stellate cell activation

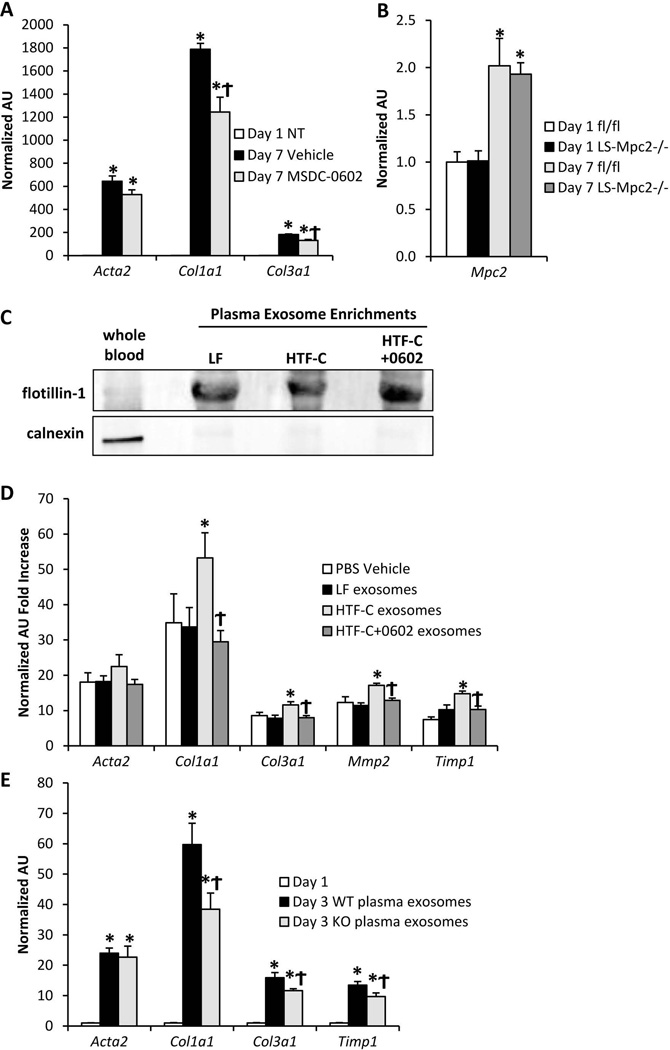

One of the most consistent phenotypes across our mouse studies was that MSDC-0602 suppressed expression of the markers of stellate cell fibrogenesis. Treatment of isolated stellate cells with MSDC-0602 during the 7 day in vitro differentiation process moderately reduced the expression of the stellate cell fibrotic markers Col1a1 and Col3a1 (Figure 7A).

Figure 7. MSDC-0602 or genetic deletion of MPC2 in hepatocytes controls stellate cell activation status via exosome release.

[A] Expression of markers of stellate cell activation in day 1 quiescent (NT= not treated) and day 7 activated stellate cells treated with vehicle or 15 µM MSDC-0602. Values are normalized (=1.0) to day 1 quiescent expression levels. [B] Hepatic stellate cells were isolated from WT or LS-Mpc2−/− mice and activated in vitro. The expression of Mpc2 was quantified in day 1 quiescent and day 7 activated cells. [C] Western blot of either whole blood or plasma exosome-enriched protein lysates probed for the membrane-bound vesicle marker flotillin-1 and the cell marker calnexin [D] Hepatic stellate cells were isolated from WT mice and treated with exosomes isolated from plasma of mice fed LF diet, HTF-C diet, or HTF-C diet containing MSDC-0602 as well as vehicle control (PBS). The expression of markers of stellate cell activation was quantified after 24 h exposure to exosomes between day 2 and 3 in culture. Values are normalized (=1.0) to day 1 quiescent expression levels. [E] Hepatic stellate cells were isolated from WT mice and treated with exosomes isolated from plasma of WT or LS-Mpc2−/− mice for 24 h between days 2 and 3 in culture. Values are normalized (=1.0) to day 1 quiescent expression levels. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM. N=6, with 2 independent stellate cell isolations and 3 technical replicates per experiment.

We found that genetic deletion of Mpc2 in the liver also led to reduced activation of stellate cells in vivo (Figure 6C,D). It has been suggested that the albumin promoter may be active in stellate cells and leads to Cre-mediated recombination in that cell type (38). To determine whether Mpc2 expression was affected in stellate cells of the LS-Mpc2−/− mice, we isolated hepatocytes and stellate cells from these mice. In our hands, while the LS-Mpc2−/− hepatocyte fraction shows the expected deletion of Mpc2 (24), its expression was not affected in the LS-Mpc2−/− stellate cells in either the day 1 quiescent, or day 7 activated states (Figure 7B). This suggests that the beneficial effects of genetic inhibition of the Mpc2 in LS-Mpc2−/− mice were likely not mediated via direct effects in stellate cells. Taken together with the modest effect of MSDC-0602 on stellate cell activation in vitro (Figure 7A), these data suggest that the effects of modulating MPC2 specifically in hepatocytes may produce an anti-fibrotic paracrine signal that contributes to the reduced stellate cell activation.

Suppression of stellate cell activation may be mediated by hepatocyte-derived exosomes

Recent work has suggested that extracellular vesicles, called exosomes, that are released by hepatocytes and other cell types can signal to stellate cells by transferring DNA, RNA, protein, or lipid contents (39–43). Increased exosome release by steatotic hepatocytes in vitro and in vivo has also been suggested (44, 45). Therefore, we next isolated exosome-enriched plasma fractions from our LF and HTF-C-fed mice to test whether a paracrine signal was being released from hepatocytes to stellate cells to affect fibrogenesis. The plasma exosome samples were enriched for the membrane vesicle marker flotillin-1, and were devoid of the cell marker calnexin (Figure 7C). When stellate cell cultures were treated with these plasma exosome fractions between day 2 and 3 of culture, plasma exosomes isolated from HTF-C-fed mice increased the expression of Col1a1, Col3a1, Mmp2, and Timp1 in stellate cells isolated from naïve WT mice (Figure 7D). However, plasma exosomes isolated from mice fed HTF-C diet containing MSDC-0602 failed to enhance the expression of these genes (Figure 7D). Lastly, plasma exosomes from HTF-C diet-fed LS-Mpc2−/− mice also reduced the expression of stellate cell fibrogenic markers in comparison to plasma exosomes from HTF-C diet-fed WT mice (Figure 7E). Altogether, these data suggest that MSDC-0602 treatment or genetic deletion of MPC2 in hepatocytes modifies exosomes containing or lacking a factor that subsequently controls stellate cell activation status.

Discussion

Available evidence suggests a strong interconnection among insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis, and development of NASH. Indeed, a number of studies have suggested that insulin-sensitizing TZDs may have efficacy for treating NASH and potentially even reverse hepatic fibrosis (12–18). In this study, we evaluated the efficacy of a next-generation TZD that has extremely weak binding to PPARγ but still directly interacts with and inhibits the MPC. We found that MSDC-0602 prevented and reversed stellate cell activation and fibrosis in a mouse model of NASH. Moreover, we show that loss of the MPC2 protein in mouse hepatocytes also has similar protective effects on these parameters. The present in vivo and in vitro findings suggest that modulating MPC activity in hepatocytes leads to production of signaling factor(s) that regulate stellate cell activation and fibrogenesis.

Whereas we did observe a direct effect of MSDC-0602 on stellate cell activation in vitro, several other findings in this study suggest that drug effects on the expression of these genes are also mediated through effects in hepatocytes. Indeed, exosomes isolated from plasma of HTF-C diet-fed mice promoted expression of markers of stellate cell activation in vitro while exosomes from MSDC-0602 treated or knockout mice did not. The caveat is that exosomes isolated from plasma could be derived from any organ and the drug effect may not be specific to the liver. However, the data with exosomes isolated from LS-Mpc2−/− mice strongly suggest that hepatocyte-derived exosomes play an important role in this response. In support of our findings, an unidentified signal released from steatotic hepatocytes has previously been proposed to induce hepatic stellate cell activation (46). We also found that MPC2, which is up-regulated in stellate cells during activation, was not deleted in stellate cells from LS-Mpc2−/− mice. This indicates that the albumin promoter is not active in stellate cells in our hands, which contrasts a recently-published report (38), but is consistent with a paracrine factor being elicited from MPC2-deficient hepatocytes.

It remains to be determined what cargo of exosomes is responsible for communicating with stellate cells in this model of NASH and in our pharmacologic and genetic manipulations. Exosomes are small lipid vesicles that contain a variety of materials including lipids, proteins, and RNAs (47). Delivery and uptake of these vesicles to other cells is a relatively recently-identified mechanism of cell-to-cell communication and this process is incompletely understood. Previous work has suggested that hepatocyte-derived exosomes can regulate stellate cell activation (39–43). Candidate mediators would include mtDNA (43), microRNAs including let-7 and miR-122-5p (41) and miR-214 (39, 40), and other non-coding RNAs (42). Future studies will be needed to identify the mediator(s) that signal between hepatocytes and stellate cells in our system, as well as how altering hepatocyte pyruvate metabolism leads to these beneficial effects on exosome cargo.

In summary, the present data suggest that the novel insulin-sensitizer MSDC-0602 has beneficial pharmacological effects to prevent and reverse stellate cell activation and fibrosis in a mouse model of NASH. Importantly, the effects of this agent, which has inhibitory effects on the activity of the MPC, were recapitulated by genetic deletion of MPC2 in hepatocytes and the effects of MSDC-0602 were lost when MPC2 was deleted. The data presented herein supports a model that hepatocyte-derived exosomes mediate a beneficial effect of MPC2 deletion on stellate cell activation. Though more work is needed to completely understand mechanisms and mediators, the present data support further studies using MPC modulators for treating NASH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support:

NIH grants R01 DK078187 and R01 DK104735 to BNF, R42 AA021228 to RFK and BNF, and R01 DK108357 to JES. Cores of the Digestive Diseases Research Core Center (P30 DK52574), Diabetes Research Center (P30 DK020579), and the Nutrition Obesity Research Center (P30 DK56341) at the Washington University School of Medicine also supported this work. KSM is a Diabetes Research Postdoctoral Training Program fellow (T32 DK 007120 and T32 DK007296).

Conflicts of Interest: WGM and JRC are interest holders in MSDC, developer of MSDC-0602, and Octeta Therapeutics, which is currently evaluating MSDC-0602K in subjects with NASH in trial NCT02784444.

List of abbreviations (in order of appearance)

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma

- MPC

mitochondrial pyruvate carrier

- TZD

thiazolidinedione

- HTF-C

High trans-fat, fructose, cholesterol diet

- LF

low fat diet

- ALT

alanine transaminase

- AST

aspartate transaminase

- NAS

NAFLD activity score

- RESPYR

REporter Sensitive to PYRuvate

- BRET

bioluminescence energy transfer

References Cited

- 1.Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Diehl AM, Brunt EM, Cusi K, Charlton M, et al. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Gastroenterological Association. Hepatology. 2012;55:2005–2023. doi: 10.1002/hep.25762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baffy G, Brunt EM, Caldwell SH. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an emerging menace. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1384–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charlton MR, Burns JM, Pedersen RA, Watt KD, Heimbach JK, Dierkhising RA. Frequency and outcomes of liver transplantation for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1249–1253. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong RJ, Aguilar M, Cheung R, Perumpail RB, Harrison SA, Younossi ZM, Ahmed A. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:547–555. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Rafiq N, Makhlouf H, Younoszai Z, Agrawal R, Goodman Z. Pathologic criteria for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: interprotocol agreement and ability to predict liver-related mortality. Hepatology. 2011;53:1874–1882. doi: 10.1002/hep.24268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekstedt M, Hagstrom H, Nasr P, Fredrikson M, Stal P, Kechagias S, Hultcrantz R. Fibrosis stage is the strongest predictor for disease-specific mortality in NAFLD after up to 33 years of follow-up. Hepatology. 2015;61:1547–1554. doi: 10.1002/hep.27368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angulo P, Kleiner DE, Dam-Larsen S, Adams LA, Bjornsson ES, Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Mills PR, et al. Liver Fibrosis, but No Other Histologic Features, Is Associated With Long-term Outcomes of Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:389–397. e310. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hannah WN, Jr, Harrison SA. Effect of Weight Loss, Diet, Exercise, and Bariatric Surgery on Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2016;20:339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2015.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed A, Wong RJ, Harrison SA. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Review: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcomes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:2062–2070. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dudekula A, Rachakonda V, Shaik B, Behari J. Weight loss in nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease patients in an ambulatory care setting is largely unsuccessful but correlates with frequency of clinic visits. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111808. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Brunt EM, Wehmeier KR, Oliver D, Bacon BR. Improved nonalcoholic steatohepatitis after 48 weeks of treatment with the PPAR-gamma ligand rosiglitazone. Hepatology. 2003;38:1008–1017. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caldwell SH, Patrie JT, Brunt EM, Redick JA, Davis CA, Park SH, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. The effects of 48 weeks of rosiglitazone on hepatocyte mitochondria in human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2007;46:1101–1107. doi: 10.1002/hep.21813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boettcher E, Csako G, Pucino F, Wesley R, Loomba R. Meta-analysis: pioglitazone improves liver histology and fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:66–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04912.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanyal AJ, Chalasani N, Kowdley KV, McCullough A, Diehl AM, Bass NM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, et al. Pioglitazone, vitamin E, or placebo for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1675–1685. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nan YM, Fu N, Wu WJ, Liang BL, Wang RQ, Zhao SX, Zhao JM, et al. Rosiglitazone prevents nutritional fibrosis and steatohepatitis in mice. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:358–365. doi: 10.1080/00365520802530861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupte AA, Liu JZ, Ren Y, Minze LJ, Wiles JR, Collins AR, Lyon CJ, et al. Rosiglitazone attenuates age- and diet-associated nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in male low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice. Hepatology. 2010;52:2001–2011. doi: 10.1002/hep.23941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cusi K, Orsak B, Bril F, Lomonaco R, Hecht J, Ortiz-Lopez C, Tio F, et al. Long-Term Pioglitazone Treatment for Patients With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis and Prediabetes or Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016 doi: 10.7326/M15-1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehmann JM, Moore LB, Smith-Oliver TA, Wilkison WO, Willson TM, Kliewer SA. An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR gamma) J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12953–12956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.12953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soccio RE, Chen ER, Lazar MA. Thiazolidinediones and the promise of insulin sensitization in type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2014;20:573–591. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Z, Vigueira PA, Chambers KT, Hall AM, Mitra MS, Qi N, McDonald WG, et al. Insulin resistance and metabolic derangements in obese mice are ameliorated by a novel peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-sparing thiazolidinedione. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:23537–23548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.363960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colca JR, VanderLugt JT, Adams WJ, Shashlo A, McDonald WG, Liang J, Zhou R, et al. Clinical proof-of-concept study with MSDC-0160, a prototype mTOT-modulating insulin sensitizer. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;93:352–359. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colca JR, McDonald WG, Cavey GS, Cole SL, Holewa DD, Brightwell-Conrad AS, Wolfe CL, et al. Identification of a mitochondrial target of thiazolidinedione insulin sensitizers (mTOT)--relationship to newly identified mitochondrial pyruvate carrier proteins. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61551. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCommis KS, Chen Z, Fu X, McDonald WG, Colca JR, Kletzien RF, Burgess SC, et al. Loss of Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier 2 in the Liver Leads to Defects in Gluconeogenesis and Compensation via Pyruvate-Alanine Cycling. Cell Metab. 2015;22:682–694. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Divakaruni AS, Wiley SE, Rogers GW, Andreyev AY, Petrosyan S, Loviscach M, Wall EA, et al. Thiazolidinediones are acute, specific inhibitors of the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:5422–5427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303360110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCommis KS, Finck BN. Mitochondrial pyruvate transport: a historical perspective and future research directions. Biochem J. 2015;466:443–454. doi: 10.1042/BJ20141171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clapper JR, Hendricks MD, Gu G, Wittmer C, Dolman CS, Herich J, Athanacio J, et al. Diet-induced mouse model of fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis reflecting clinical disease progression and methods of assessment. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;305:G483–G495. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00079.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soufi N, Hall AM, Chen Z, Yoshino J, Collier SL, Mathews JC, Brunt EM, et al. Inhibiting monoacylglycerol acyltransferase 1 ameliorates hepatic metabolic abnormalities but not inflammation and injury in mice. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:30177–30188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.595850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colca JR. The TZD insulin sensitizer clue provides a new route into diabetes drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2015;10:1259–1270. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2015.1100164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, Behling C, Contos MJ, Cummings OW, Ferrell LD, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41:1313–1321. doi: 10.1002/hep.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Porter FD, Scherrer DE, Lanier MH, Langmade SJ, Molugu V, Gale SE, Olzeski D, et al. Cholesterol oxidation products are sensitive and specific blood-based biomarkers for Niemann-Pick C1 disease. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:56ra81. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Compan V, Pierredon S, Vanderperre B, Krznar P, Marchiq I, Zamboni N, Pouyssegur J, et al. Monitoring Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier Activity in Real Time Using a BRET-Based Biosensor: Investigation of the Warburg Effect. Mol Cell. 2015;59:491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCommis KSH, W T, Bricker DK, Wisidagama DR, Compan V, Remedi MS, Thummel CS, Finck BF. An ancestral role for the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Molecular Metabolism. 2016;5:602–614. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2016.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen A, Tang Y, Davis V, Hsu FF, Kennedy SM, Song H, Turk J, et al. Liver fatty acid binding protein (L-Fabp) modulates murine stellate cell activation and diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2013;57:2202–2212. doi: 10.1002/hep.26318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trevaskis JL, Griffin PS, Wittmer C, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Brunt EM, Dolman CS, Erickson MR, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonism improves metabolic, biochemical, and histopathological indices of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G762–G772. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00476.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braeuning A, Ittrich C, Kohle C, Hailfinger S, Bonin M, Buchmann A, Schwarz M. Differential gene expression in periportal and perivenous mouse hepatocytes. FEBS J. 2006;273:5051–5061. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hall Z, Bond NJ, Ashmore T, Sanders F, Ament Z, Wang X, Murray AJ, et al. Lipid zonation and phospholipid remodeling in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2016 doi: 10.1002/hep.28953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hyun J, Choi SS, Diehl AM, Jung Y. Potential role of Hedgehog signaling and microRNA-29 in liver fibrosis of IKKbeta-deficient mouse. J Mol Histol. 2014;45:103–112. doi: 10.1007/s10735-013-9532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen L, Charrier A, Zhou Y, Chen R, Yu B, Agarwal K, Tsukamoto H, et al. Epigenetic regulation of connective tissue growth factor by MicroRNA-214 delivery in exosomes from mouse or human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2014;59:1118–1129. doi: 10.1002/hep.26768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen L, Chen R, Kemper S, Charrier A, Brigstock DR. Suppression of fibrogenic signaling in hepatic stellate cells by Twist1-dependent microRNA-214 expression: Role of exosomes in horizontal transfer of Twist1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015;309:G491–G499. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00140.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsuura K, De Giorgi V, Schechterly C, Wang RY, Farci P, Tanaka Y, Alter HJ. Circulating let-7 levels in plasma and extracellular vesicles correlate with hepatic fibrosis progression in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2016;64:732–745. doi: 10.1002/hep.28660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seo W, Eun HS, Kim SY, Yi HS, Lee YS, Park SH, Jang MJ, et al. Exosome-mediated activation of toll-like receptor 3 in stellate cells stimulates interleukin-17 production by gammadelta T cells in liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2016;64:616–631. doi: 10.1002/hep.28644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Inzaugarat ME, Wree A, Feldstein AE. Hepatocyte mitochondrial DNA released in microparticles and toll-like receptor 9 activation: A link between lipotoxicity and inflammation during nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2016;64:669–671. doi: 10.1002/hep.28666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Povero D, Eguchi A, Niesman IR, Andronikou N, de Mollerat du Jeu X, Mulya A, Berk M, et al. Lipid-induced toxicity stimulates hepatocytes to release angiogenic microparticles that require Vanin-1 for uptake by endothelial cells. Sci Signal. 2013;6:ra88. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Povero D, Eguchi A, Li H, Johnson CD, Papouchado BG, Wree A, Messer K, et al. Circulating extracellular vesicles with specific proteome and liver microRNAs are potential biomarkers for liver injury in experimental fatty liver disease. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wobser H, Dorn C, Weiss TS, Amann T, Bollheimer C, Buttner R, Scholmerich J, et al. Lipid accumulation in hepatocytes induces fibrogenic activation of hepatic stellate cells. Cell Res. 2009;19:996–1005. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cai S, Cheng X, Pan X, Li J. Emerging role of exosomes in liver physiology and pathology. Hepatol Res. 2016 doi: 10.1111/hepr.12794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.