Abstract

Craniosynostosis, the premature ossification of one or more skull sutures, is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous congenital anomaly affecting approximately 1 in 2,500 live births. In most cases, it occurs as an isolated congenital anomaly, i.e. nonsyndromic craniosynostosis (NCS), the genetic and environmental causes of which remain largely unknown. Recent data suggest that at least some of the midline NCS cases may be explained by two loci inheritance. In approximately 25–30% of patients craniosynostosis presents as a feature of a genetic syndrome due to chromosomal defects or mutations in genes within interconnected signaling pathways. The aim of this review is to provide a detailed and comprehensive update on the genetic and environmental factors associated with NCS, integrating the scientific findings achieved during the last decade. Focus on the neurodevelopmental, imaging and treatment aspects of NCS is also provided.

Keywords: Craniosynostosis, skull sutures, gene mutations, craniofacial malformation

INTRODUCTION

Major anomalies affect 1 in 33 newborns or about 125,000 live births annually in the U.S. and are a leading cause of infant mortality [Parker et al., 2010; Petrini et al., 2002]. Craniofacial anomalies account for close to one-third of all anomalies. They contribute significantly to infant morbidity and disability and the expenditure of millions of dollars annually in health care costs [Weiss et al., 2009; Dolk et al., 2010; Wehby and Cassell, 2010]. Craniosynostosis (CS) is one of the most common anomalies occurring in approximately 1 in 2,500 live births [Cohen, 2000; Gorlin et al., 2001; Boulet et al., 2008; Boyadjiev, 2014], and represents a clinically and genetically heterogeneous congenital anomaly.

The main phenotypic manifestation of CS is an abnormal head shape due to restriction of skull growth in a direction that is perpendicular to the closed suture [Virchow, 1851; Persing et al., 1989] (Figure 1). This congenital anomaly may lead to skull constraints, which may affect brain growth, resulting in a number of morphologic and functional abnormalities. True CS is to be differentiated from positional plagiocephaly, which represents a deformation of the skull in the absence of sutural fusion [Komotar et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2008]. This is an important, but not always easy task as posterior skull flattening may affect close to 20% of healthy infants at 4 months of age [Rogers, 2011].

Figure 1.

Craniofacial features and three-dimensional computed tomography images of individuals with craniosynostosis. (A–C) Nonsyndromic sagittal craniosynostosis. (D–F) Nonsyndromic metopic craniosynostosis. (G–I) Nonsyndromic unilateral right coronal craniosynostosis. (J–L) Nonsyndromic bilateral coronal craniosynostosis. (M–O) Nonsyndromic unilateral left lambdoid craniosynostosis. (P–R) Nonsyndromic bilateral lambdoid craniosynostosis. (S–W) Images of individuals with Muenke syndrome demonstrate extreme clinical variability and overlap of the milder cases with nonsyndromic coronal craniosynostosis. (X) Mild case of Saethre-Chotzen syndrome resembles unicoronal craniosynostosis. The images on the bottom row demonstrate the need of molecular testing of the coronal cases for proper diagnosis.

According to an etiological classification, CS can be defined as primary, due to intrinsic genetic causes acting alone or in combination with environmental factors; or secondary, due to disorders affecting the developing suture [Shetty et al., 1998; Higashino and Hirabayashi, 2013]. Conditions associated with secondary CS include hyperthyroidism, hypercalcemia, hypophosphatasia, sickle cell disease and thalassemia, vitamin D deficiency, renal osteodystrophy, and Hurler syndrome, among others. Finally, secondary CS may also be due to conditions that restrict growth across the open suture, such as microcephaly, encephalocele and shunted hydrocephalus [Khanna et al., 2011].

Primary craniosynostoses are usually classified, based on the possible association with additional clinical features, as syndromic or nonsyndromic (NCS). Syndromic CS manifests with additional anomalies and/or developmental delays, and is thought to account for 25–30% of all cases [Wilkie et al., 2007; Wilkie et al., 2010; Passos-Bueno et al., 2008]. Monogenic mutations or chromosomal defects are typically found in 75–80% of the syndromic patients [Johnson and Wilkie, 2011]. Conversely, NCS occurs in the absence of associated anomalies or developmental delays [Boyadjiev, 2007].

NCS occurs in approximately 75% of all patients with CS [Cohen, 2000; Greenwood et al., 2014]. It is usually classified based on the type of suture fusion (sagittal, metopic, bi- or unicoronal, and bi- or unilambdoid synostoses), that leads to an abnormal skull shape (dolichocephaly, trigonocephaly, brachycephaly, anterior or posterior plagiocephaly, respectively). Sagittal synostosis is the most frequent form, accounting for 45–58% of all NCSs (1,9–2,3 per10,000 live births) [Lajeunie et al., 1996; Di Rocco et al., 2009a; Ursitti et al., 2011; Lattanzi et al., 2012]. Recent epidemiological studies have suggested that metopic synostosis has become the second most prevalent form (occurring in over 25% of all NCS patients), as a result of a significantly increased incidence in the Western World over the last two decades. This may be due to a number of factors, including increased exposure to environmental risk factors or improved diagnosis [Selber et al., 2008; van der Meulen et al., 2009]. Unicoronal synostosis has become the third most prevalent NCS, accounting for less than 15% of NCS in the large cohorts analyzed to date [Selber et al., 2008; van der Meulen et al., 2009; Di Rocco et al., 2009a, b]. Bicoronal synostosis, leading to brachycephaly, is approximately half as frequent as the unicoronal form [Lajeunie et al. 1995]. Lambdoid synostosis, resulting in posterior plagiocephaly, is the least common type, representing 1% of all CS and 3% of NCS [Lattanzi et al., 2012; Heuzé et al., 2014]. Although NCS are mainly sporadic, a positive family history has been reported in 2–10% of the patients depending on the involved suture [Greenwood et al., 2014].

NCS appears to be a heterogeneous group of anomalies based on the type of suture closure patterns as suggested by the various population incidences and discrepant male/female ratios (2.5:1 to 3:1 for sagittal and metopic NCS and around 1:2 for unicoronal NCS) [Selber et al., 2008]. NCS is thought to be a multifactorial condition, with both genetic and environmental factors contributing to the phenotype. The evidence for genetic determinants of NCS is based on observations of multiplex families, the increased recurrence risk in the affected families and twin studies documenting increased concordance rates among monozygotic as compared to dizygotic twins (60.9% versus 5.3%) [Lakin et al., 2012]. However, the lack of complete concordance among monozygotic twins suggests that environmental, epistatic, and/or epigenetic factors play a role in the etiology of CS. We have found that the highest incidence of recurrence among first-degree relatives, mostly in siblings, was for metopic NCS, followed by complex NCS, sagittal NCS, lambdoid NCS, and coronal NCS [Greenwood et al., 2014]. In this same cohort, patients with complex NCS showed the highest frequency of associated symptoms (including ear infections, palate abnormalities, and hearing problems) while sagittal NCS presented mostly as a truly isolated form [Greenwood et al. 2014]. Previous epidemiological studies [Alderman et al., 1988; Kallen, 1999; Zeiger et al., 2002; Reefhuis et al., 2003; Reefhuis and Honein, 2004; Sanchez-Lara et al., 2010; Gill et al., 2012; Boyadjiev, 2014] have suggested that male sex, non-Hispanic white race/ ethnicity, advanced maternal age and maternal age <20 years are associated with NCS. Such studies showed mixed results for twinning, intrauterine head constraint, plurality, parity, prematurity, and macrosomia. Prenatal exposures to maternal tobacco smoking and other hypoxemia-inducing agents [Carmichael et al., 2008], sodium valproate [Lajeunie et al., 2001], retinoic acid [James et al., 2010], antidepressants [Alwan et al., 2007], and infertility medications [Ardalan et al., 2012] have been suggested, but have not been conclusively proven to be related. The equivocal findings for environmental exposures may be due to small sample sizes, limited co-variable data, limited subtype analysis, and differently defined intervals for the critical period of exposure.

The public health burden of CS is substantial. Infants with CS typically require extensive surgical treatment in the first year of life. The most frequent and serious perioperative complication is the occurrence of intraoperative hemorrhages that can cause significant blood loss and require transfusions in approximately 80% of patients [Mathijssen and Arnaud, 2007]. Re-synostosis occurs in approximately 6% of NCS patients and in 15% of those with syndromic CS [Foster et al., 2008]. Patients with complex and/or syndromic forms typically require multiple surgeries, with increased burden and consequently worse prognosis [Wilkie et al., 2010]. With current surgical treatment methods, the mortality is less than 1% [Nguyen et al., 2013]; but even after successful surgery, children with sagittal NCS or metopic NCS can experience ongoing medical problems, such as increased intracranial pressure [Thompson et al., 1995a, b; Shimoji et al., 2002], developmental disabilities [Magge et al., 2002; Shipster et al., 2003; Chieffo et al., 2010], vision problems [Gupta et al., 2003], Chiari I malformation [Tubbs et al., 2001], and even sudden death [Rabl et al., 1990].

In this paper we provide a comprehensive review of the genetic causes of CS, with a specific focus on the molecular mechanisms associated with NCS and newly categorized syndromes. This work is an update of our previous reviews on this topic [Boyadjiev and International Craniosynostosis Consortium, 2007; Kimonis et al., 2007; Lattanzi et al., 2012] and provides the reader with a broader insight into CS, its developmental aspects, the diagnostic imaging techniques and available surgical options.

SKULL AND SUTURE ORIGIN AND GROWTH

Human skull development begins around 23–26 days post-fertilization, when a multipotent cranial neural crest cell population migrates from the dorsal aspect of the neural tube into the head region of the embryo to give rise to craniofacial structures. Upon completion of neural crest migration the head has mesenchyme originating from both paraxial mesoderm and cranial neural crest [Noden, 1983; Noden, 1986]. While the neural crest is widely recognized as the embryonic origin of the facial bones [Couly et al., 1992; Couly et al., 1993; Opperman, 2000], the origin of the other intramembranous calvarial bones is still debatable. Experiments with a quail-chick chimera system have suggested that the intramembranous bones of the cranial vault and the sutures originate from paraxial mesoderm [Noden, 1986]. However, these data were later disputed by studies using the same experimental system that suggested the cephalic neural crest cells were an initial source of the membranous bones of the skull [Couly et al., 1992; Couly et al., 1993]. Even if there is no contribution of neural crest cells to the membranous bones, the dura, which arises from neural crest cells, plays a major role in regulating the growth of the membranous vault and maintaining suture patency [Yu et al., 1995; Lee et al., 2006; Bifari et al., 2015]. The current view of the embryonic origin of the skull is that the neural crest gives rise to the frontal bone and the interparietal portion of the occipital bone, while the rest of the skull vault is derived mostly from mesoderm, with some minor contribution from the cranial neural crest cell population [Jiang et al., 2002; Ting et al., 2009].

The growth of the skull is driven by the growth of the underlying brain, which reaches 90% of adult size in the first year and 95% of adult size by 6 years of age [Williams, 2008]. The mature skull has two main components: the neurocranium and the viscerocranium. The neurocranium includes the membranous skull roof that surrounds the brain and is comprised of the frontal bone, the paired parietal and temporal bones, and the occipital bone, which has both cartilaginous and membranous parts. It also includes the cartilaginous skull base with the greater wings of the sphenoid, the ethmoid, and the petrous part of the temporal bones [Shapiro and Robinson, 1976]. The viscerocranium consists of the cartilaginous facial bones that articulate with the skull base, and may be distorted to a various degree in CS.

The cranial sutures form around the 16–18th week post-fertilization as dense fibrous tissue membranes bridging the gaps between the cranial bones [Wilkie, 1997; Mathijssen et al., 1999]. The calvarial sutures allow molding of the head in the birth canal, serve as growth sites of the skull, and absorb mechanical trauma in the first years of life. During that period, the cells within the suture must proliferate without differentiating to maintain patency while those at the bone margins differentiate to ensure growth [Morriss-Kay and Wilkie, 2005; Lana-Elola et al., 2007]. This balance between cell proliferation and differentiation ensures suture patency and the coordinated growth of the cranial vault. Indeed, slow cycling, self-renewing stem cells are found within the suture midline which represent a calvarial-specific skeletogenic niche, ensuring bone modeling, remodeling, regeneration, and healing over an extensive time period during skeletal development [Lattanzi et al., 2015; Zhao and Chai, 2015; Maruyama et al., 2016]. The metopic suture is the first to close at approximately 9 months of age [Blaser, 2008] while the fusion of the remaining calvarial sutures does not occur until the third decade of life. In contrast, the sutures of the viscerocranium remain open until the seventh or eighth decade of life. The postnatal shape of the skull is characterized by the cephalic index (CI = head width/head length ×100), with the normal range 76 to 81. Anything less than 76 is labeled dolichocephaly and above 81 is brachycephaly [Hall et al., 2013].

It is important to point out that CS is not the sole result of an abnormal growth of the calvarial bones. A recent report indicated that congenital absence of the sagittal suture does not necessarily manifest with dolichocephaly [Padmalayam et al., 2013]. This suggests that CS may not be an entirely skeletal phenotype; deviations from the normal brain growth patterns with subsequent abnormal distention of the dura may also be implicated in suturefusion [Yu et al., 2001; Aldridge et al., 2002].

GENETIC ETIOPATHOGENESIS OF CRANIOSYNOSTOSIS

In the attempt to comprehensively dissect the molecular causes of CS, we will first briefly introduce the genetic causes of the best defined CS syndromes in this section. We will then focus on the most recent findings regarding the genetic etiology of previously undefined simple and complex CS cases, including truly nonsyndromic forms, with the intent of depicting possible genotype/phenotype correlations between mutated genes and pattern of suture closure.

Syndromic CS: genes and chromosomal aberrations

Significant progress in the last few decades has been made in understanding the genetic causes of syndromic forms of CS [Wilkie et al., 2007; Johnson and Wilkie, 2011; Twigg and Wilkie, 2015a]. In recent years, converging evidence suggests a stronger influence of genetic factors in the etiopathogenesis of NCS thanks to genome-wide analyses aimed at identifying new mutations and disease-associated loci in large patient cohorts. The complete list of genetic syndromes with a CS phenotype currently includes around 170 entries in the OMIM database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/?term=craniosynostosis) [Heuzé et al., 2014; Twigg and Wilkie, 2015a; Lattanzi, 2016].

Although syndromic craniosynostoses are mostly regarded as monogenic disorders, reliable information on the molecular etiopathogenesis can also be gathered from chromosomal aberrations found in patients. These are observed in about 14% of patients with predominantly complex/syndromic CS, the majority of these being of uncertain significance [Wilkie et al., 2010]. The incidence of chromosomal aberrations detected by routine karyotype and various molecular techniques was as high as 42% in a group of 45 patients with syndromic CS, while submicroscopic defects were present in 28% of those with normal karyotypes [Jehee et al., 2008]. The causative role of many of these, however, is uncertain considering the large number of neutral copy number variants in the genome. Hence, the true incidence of causative chromosomal defects is yet to be determined.

Several loci have been recurrently described, but their significance also remains partially unclear [Lattanzi et al., 2012]. In particular, 1p36.3 dosage imbalance has been studied in detail in the attempt to identify candidate genes involved in suture closure. Deletion of chromosome 1p36, the most common terminal deletion observed in humans, is associated with delayed suture closure, along with additional craniofacial features, intellectual disability, hearing impairment, seizures, growth impairment, and heart defects [Gajecka et al., 2005]. Conversely, duplication and triplication of this locus are extremely rare; they have been associated with complex malformation syndromes, which include either metopic [Heilstedt et al., 1999] or coronal craniosynostosis [Garcia-Heras et al., 1999]. Increased copy number of the matrix metalloproteinase-23 (MMP23) -A and -B genes which are involved in extracellular matrix remodeling and map to 1p36, play a role in cranial suture patency and closure [Gajecka et al., 2005].

The short arm of chromosome 7 has also been found to be involved in interstitial deletions found in patients with complex phenotypes, often resembling Saethre-Chotzen syndrome [Kosaki et al., 2005; De Marco et al., 2011; Fryssira et al., 2011]. Indeed the 7p21 locus houses TWIST1 along with the HOXA gene cluster; hence, plausible deletions cause haploinsufficiency leading to a complex impairment of systemic development [Chotai et al., 1994; Tsuji et al., 1995; Zneimer et al., 2000].

The 9p22.3 region represents a specific hotspot for metopic CS (OMIM #158170) [Jehee et al., 2005; Kawara et al., 2006; Swinkels et al., 2008; Vissers et al., 2011; Choucair et al., 2015]. Deletions at this locus are found in over 15% of patients with syndromic trigonocephaly who may also have additional suture involvement, developmental delay and facial dysmorphisms, including midface hypoplasia [Jehee et al., 2005]. A careful revision of the clinical and the neuroradiological findings of the 9p deletion syndrome has been recently proposed to assist with the differential diagnosis of those patients wth trigonocephaly who are more likely to have an underlying chromosomal aberration [Spazzapan et al., 2016]. The FRAS1-related extracellular matrix 1 (FREM1) gene is the most likely candidate in this region. FREM1 is believed to bind fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) within the intrasutural mesenchyme. Therefore, with FREM1 haploinsufficiency the availability of FGF growth factors is expected to increase, which ultimately leads to premature ossification [Yu et al., 2001; Vissers et al., 2011]. More recently, the receptor-type protein tyrosine phosphatase gene (PTPRD), located in the 9p24.1-p23 region, was deleted in a patient with trigonocephaly, dysmorphic facial features, and severe intellectual disability [Choucair et al., 2015]. This gene is expressed in cortical neurons and plays an important role in synaptic organization. Besides its role in cognitive functions, it is also postulated to represent an additional plausible candidate in the 9p22.3 region for metopic CS [Mitsui et al., 2013; Choucair et al., 2015].

Interstitial duplications involving chromosome 11q have been associated with syndromic CS phenotypes. In particular, 11q11-q13.3 duplications have been reported in patients with either coronal [Grillo et al., 2014] or multisuture CS [Jehee et al., 2007], featuring a plethora of additional signs including congenital heart defects and developmental delay. Fibroblast growth factor-3 (FGF3) and -4 (FGF4), mapping to 11q13.3, represent the most plausible candidates causing abnormal craniofacial development as a result of increased dosage [Jehee et al., 2007; Grillo et al., 2014].

11q23-q24 represents another recurrent hotspot in syndromic CS with characteristic facial dysmorphisms and psychomotor delay (Jacobsen syndrome, OMIM#147791), particularly involving the metopic suture [Azimi et al., 2003; Jehee et al., 2005; Foley et al., 2007; Passariello et al., 2013]. Genes mapping in this chromosome region include the lysine methyltransferase 2A (KMT2A) gene, which interacts in multiprotein complexes that regulate the expression of multiple HOX genes, among others [Milne et al., 2002; Nakamura et al., 2002]. Interestingly, Kmt2a heterozygous deletion in mice causes homeotic transformation of the axial skeleton and malformations of the membranous bones [Yu et al., 1995.]

CS is observed also as a recurrent feature in 22q11 deletion syndrome [Dean et al., 1998]. Variable degrees of CS severity have been described in this condition, ranging from metopic [Yamamoto et al., 2006], or bicoronal CS [McDonald-McGinn et al., 2005; Rojnueangnit and Robin, 2013], to severe multisutural CS [Al-Hertani et al., 2013], indicating the markedly variable expressivity of the anomaly [De Silva et al., 1995; Dean et al., 1998]. The molecular etiopathogenesis of the CS phenotype observed in this contiguous gene syndrome has not been clarified to date. Finally, metopic synostosis has also been described in a single patient with mosaic trisomy 13 [Aypar et al., 2011]. Table I summarizes the recurrent chromosomal loci discussed in this section and provides a tentative association with the pattern of suture closure. Taken together, these data seem to suggest that the prevalence of chromosomal aberrations is around 50% when the CS affects the metopic suture.

Table I.

Chromosomal hotspot loci for CS, with putative candidate genes.

| Chromosomal locus |

Candidate gene(s) |

Affected suturea | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sagittal | Metopic | Coronalb | Multiple | |||

| 1p36 |

MMP23A MMP23B |

+ | + | Heilstedtl, 1999; Garcia-Heras, 1999. | ||

| 9p22.3 |

FREM1 PTPRD |

+ |

Jehee, 2005; Kawara, 2006; Swinkels, 2008; Vissers, 2011; Mitsui, 2013; Choucair, 2015. |

|||

| 11q11-q13.3 |

FGF3 FGF4 |

+ | + |

Grillo, 2014; Jehee, 2007; Yu, 1995; |

||

| 11q23-q24 | KMTM2A? | + |

Milne, 2002; Nakamura, 2002; Azimi, 2003; Jehee, 2005; Foley, 2007; Passariello, 2013. |

|||

| 22q11 | CGSc | + | + | + |

Yamamoto, 2006; Rojnueangnit, 2013; McDonald-McGinn, 2005; Al-Hertani, 2013. |

|

Always in syndromic phenotypes;

Both uni- and bicoronal cases are considered;

contiguous gene syndrome.

Given the recurrence and the extreme heterogeneity of chromosomal and submicroscopic rearrangements, chromosomal microarray has been recommended as a first-tier genetic test for patients with congenital anomalies and/or developmental delays [Miller et al., 2010], and is justified for all patients with any unclassified syndromic CS. Whether chromosomal microarray is indicated for patients with sporadic NCS is debatable, but may be reasonable for patients with familial occurance of NCS.

Molecular genetics of NCS

NCS is often considered a multifactorial disorder rather than a truly genetic condition; however, the putative role of environmental risk factors is still widely debated [Lajeunie et al., 2005; Boyadjiev and International Craniosynostosis Consortium, 2007; Di Rocco et al., 2009a]. In recent years, evidence from genome-wide association studies and exome sequencing analyses suggests a stronger influence of genetic factors in the etiopathogenesis of NCS. In a limited number of patients, selected mutations in known genomic hotspots and in new loci have been described [Boyadjiev et al., 2002; Twigg and Wilkie, 2015a]. In some patients, low penetrance mutations in genes associated with syndromic forms may contribute to the etiology of NCS [Heuzé et al., 2014]. Recently Timberlake et al. [2016] documented SMAD6 mutations in 7% of patients with midline (sagittal and/or metopic) NCS by using an exome sequencing approach. Importantly, transmitted SMAD6 mutations were present in 25% (4 of 17) of the patients with familial occurance of midline CS. These authors suggested two-loci inheritance for NCS due to epistatic interaction where the effect of SMAD6 mutations with reduced penetrance is augmented by the previously identified risk allele of the common SNP rs1884302 in the vicinity of BMP2 [Justice et al., 2012]. These observations would place at least a portion of NCS in the relatively small list of human disorders with digenic inheritance [Lupski, 2012].

Given that the genetic component is believed to be suture-specific [Zeiger et al., 2002], here we will attempt to categorize all recent molecular genetic findings in NCS, including simple/complex (multi-suture) NCS phenotypes with subtle associated features that are not yet classified as syndromes. Table II provides a detailed list of genes involved in different suture closure patterns in such cases.

Sagittal NCS

Sagittal NCS (sNCS) occurs in 1 in 5,000 live births, being the most prevalent NCS. The genetic causes in the majority of patients remain unknown. Our group has completed the first genome wide association study of 130 patient-parent trios with sagittal NCS and identified strong and reproducible associations with BMP2 and BBS9 [Justice et al., 2012]. Preliminary data suggest that BMP2 is upregulated due to a putative enhancer effect of the associated region [Justice, 2014]. Rare SMAD6 mutations in combination with the risk C allele of rs1884302 near BMP2 were identified in 2.7% (3 of 113) of patients with NCS [Timberlake et al., 2016]. The same authors found SPRY1 and SPRY4 mutations in one sporadic and one familial occurance of sNCS, respectively.

Mutation screening of FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, or TWIST1 has identified causative mutations in rare cases [Boyadjiev et al., 2002; Zeiger et al., 2002]. Weber and colleagues identified a c.943G>A transition leading to missense A315T mutation in FGFR2 in one out of 29 patients (3%) with sNCS [Weber et al., 2001]. A point mutation in the C-terminal domain of TWIST1 has been found in one of 83 patients (1.2%) with sagittal synostosis and minor associated dysmorphisms [Seto et al. 2007]. The same sequence variant was previously interpreted as a polymorphism, rather than a disease-causing mutation [Kress et al., 2006]. Very recently Ye and colleagues identified two rare variants in a selected cohort of 93 sNCS cases: a FGFR1 insertion c.730_731insG, which led to a premature stop codon, and a c.439C>G variant in TWIST1 [Ye et al., 2016]. The latter variant was found in the patient's mother presenting with jaw abnormalities.

Gain-of-function variants in the coding region of ALX4, account for about 1.5% of sNCS patientes [Yagnik et al., 2012]. Since these ALX4 variants were also found in an unaffected parent, they may represent low penetrance mutations that, as is the case of SMAD6 [Timberlake et al., 2016], require predisposing variants at a second locus. The incomplete penetrance of MSX2 mutations, leading to an extremely variable expression of the Boston-type CS, may also explain selected cases of isolated sagittal and/or unicoronal synostosis [Janssen et al., 2013]. By sequencing 27 candidate genes in 186 patients with sNCS, Cunningham and colleagues found five missense mutations in the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R), a gene involved in calvarial suture development [Cunningham et al., 2011; Al-Rekabi et al., 2016]. In particular, distinct private variants were identified in two out of 94 (2%) patients with sagittal involvement, although in one patient the same mutation was found in the unaffected mother, indicating possibly incomplete penetrance [Cunningham et al., 2011]. More recently, Twigg et al. found mutations in ERF by exome sequencing of 412 unrelated CS patients [Twigg et al., 2013]. Although the mutations were mainly associated with either syndromic or complex NCS, a mutation was also described in a single patient (out of 70) with a truly nonsyndromic form of sagittal craniosynostosis.

The mutations in the above genes account for approximately 10% of patients with sNCS, and appear to have incomplete penetrance confirming the perception that NCS is a multifactorial or oligogenic disorder with considerable genetic heterogeneity.

Metopic NCS

The metopic NCS (mNCS) incidence is reported to range between 1/7,000 and 1/15,000 births, according to recent updates [van der Muelen, 2012] and seems to have a stronger genetic component compared to sNCS. Familiar recurrence has been described in up to 10% of patients and the incidence rate of the phenotype observed in first-degree relatives is 6.4%, a rate higher than in any other NCS [Greenwood et al., 2014].

Cytogenetic abnormalities are relatively frequent among the causes of metopic CS, and are believed to occur in at least 6% of the patients [Kini et al., 2010]. Since these rearrangements can be subtle, a chromosomal microarray screening is indicated for patients with metopic CS and developmental delays.

Conversely, gene mutations are rare in mNCS. SMAD6 mutations were identified in 12.8 % (10 of 78) of the probands with single suture or complex mNCS and 7 of the probands also carried the risk C allele of rs1884302 near BMP2. Seven of the eight unaffected parents in the kindreds who carried SMAD6 mutations were homozygous for the common T allele of rs1884302 and the only affected parent carried the risk C allele. These facts were interpreted as evidence for a two-loci inheritance of midline NCS [Timberlake et al., 2016]. An unusual FGFR1 I300W mutation has been reported in a girl with mNCS and facial skin tags [Kress et al., 2000]. The mutation was not present in the mother DNA (the father could not be tested) nor in 300 control chromosomes [Kress et al., 2000]. Recently, FREM1 was suggested as a candidate gene for mNCS. FREM1 is expressed in intrasutural mesenchyme and may play a key role in maintaining suture patency. FREM1 mutations were identified in eight out of 104 (5.8%) patients with metopic CS, including two patients with mNCS [Vissers et al., 2011]. Finally, premature closure of the sagittal and metopic sutures has been found associated with hearing impairment, crumpled ear, widely spaced eyes, and developmental delay in the syndromic phenotype associated with an intronic breakpoint in PTH2R [Kim et al., 2015].

Coronal NCS

Coronal NCS (cNCS; incidence 1:10,000 live births) is thought to have a stonger genetic component compared to the other forms of NCS [Lajeunie et al., 1995; Wilkie et al., 2010] with specific monogenic mutations present in about 60% of patients with bicoronal and 30% of patients with unicoronal CS [Twigg et al., 2015c]. Indeed, diverse genes may account for the higher incidence of monogenic variants in cNCS. These include FGFR3, TWIST1, EFNB1, and TCF12, which were also associated with syndromic forms of craniosynostosis [Twigg and Wilkie, 2015b].

The P250R substitution in FGFR3 was initially thought to cause cNCS but was later defined as the cause of Muenke syndrome [Muenke et al., 1997]. It represents the most frequent genetic anomaly observed in all CS patients (5.6% tested patients; 24% of all causative mutations [Wilkie et al., 2010]). Lajeunie et al. [1999] observed this mutation in 17% of patients with sporadic and 74% of patients with familial cCS. Due to the phenotype variability of Muenke syndrome, detailed clinical examination and molecular testing is mandatory for all patients diagnosed with coronal CS, even in apparently nonsyndromic forms. Emphasizing the importance of molecular testing is the fact that surgical outcomes and prognosis of patients undergoing surgery for coronal CS is significantly and specifically affected by the presence of the P250R mutation [Wilkie et al., 2010].

Seto and collaborators [Seto et al., 2007] found a c.556G>T (p.Ala186Thr) substitution in TWIST1 in a patient diagnosed with unicoronal right cNCS who also had mild nonspecific dysmorphic features. The mutation was considered pathogenic as it falls within the highly evolutionary conserved TWIST Box, which is needed for inhibition of RUNX2 transactivation [Seto et al., 2007]. The same authors also identified an 18bp deletion in the polyglycine tract of TWIST1, interpreted as a rare sequence variant with unclear pathogenetic significance [Seto et al., 2007]. TWIST1 mutations were found in six out of 43 Korean patients (14%) with uni/bicoronal CS, including a single nonsyndromic patient (2.3%) [Ko et al., 2012]. As a further confirmation of the somewhat specific role of TWIST1 in coronal suture patterning, Twist+/− mutant mice exhibit a brachycephalic skull consistent with the involvement of the coronal suture in craniofacial dysmorphism [Parsons et al., 2014]. Based on these facts TWIST1 mutational analysis should be considered for patients with coronal CS even in the absence of clear syndromic traits.

A recent exome sequencing study identified heterozygous mutations in TCF12, which is functionally related to TWIST1 and plays a critical role in coronal suture development [Sharma et al., 2013]. In particular, TCF12 mutations were found in 10% of patients with unicoronal and 37% of patients with bicoronal CS. Although 81% of the individuals with TCF12 mutations presented with apparent cNCS, some of the affected individuals had developmental delays and dysmorphic features overlapping with the Saethre-Chotzen syndrome [Sharma et al., 2013]. More recently, the phenotypic spectrum of TCF12 mutations has been extended to include possible facial and limb anomalies, and intellectual disability [Di Rocco et al., 2014; Le Tanno et al., 2014; Paumard-Hernandez et al., 2015; Piard et al., 2015]. Based on these observations, it is reasonable to recommend TCF12 testing for all patients with cCS, with or without associated anomalies.

As already mentioned above, due to the variable expression and incomplete penetrance of MSX2 mutations (associated with the Boston-type craniosynostosis syndrome), MSX2 testing should be also considered for cCS patients with a positive family history, even if the anomaly appears to be nonsyndromic [Janssen et al., 2013].

A novel FGFR2 A315S mutation was reported in a patient with right unicoronal NCS born following a pregnancy complicated by breech presentation and skull compression [Johnson et al., 2000]. Both the patient’s mother and maternal grandfather carried the mutation and had mild facial asymmetry but no CS, suggesting that the mutation predisposes individuals to synostosis in the presence of intrauterine constraint. More recently, new genes have been associated with cNCS. Rare IGF1R variants have been found in three out of 46 (6.5%) cNCS patients. Although considered to be “nonsyndromic”, all patients (with both sagittal and coronal involvement) with IGF1R variants in this study had reduced scores on neuropsychometric testing and/or subtle cognitive delay [Cunningham et al., 2011].

Zinc finger protein of cerebellum 1 (ZIC1) belongs to a family of Zn-finger transcription factors that, in vertebrates, play crucial roles in vertebrate neurogenesis, left-right axis formation, myogenesis, and skeletal patterning [Aruga et al., 2006; Merzdorf, 2007]. A heterozygous mutation in the last exon of ZIC1 was identified by exome sequencing in a proband with severe bicoronal CS, autism and developmental delay [Twigg et al., 2015c]. In order to clarify the significance of ZIC1 in the etiology of CS, the authors screened a cohort of 307 patients with various types of syndromic and nonsyndromic CS and identified 4 additional probands with bicoronal CS who had mutations in the last exon of ZIC1. Three of the affected individuals presented with bony defects of the sutures or the skull, and various brain anomalies were identified in four of the five probands. Because developmental disabilities and associated clinical features were present, the CS of these patients cannot be defined as nonsyndromic. Given the variable clinical severity in one multiplex family in this study, ZIC1 testing should be considered in all cCS patients in whom mutations in commonly associated genes have been excluded [Twigg et al., 2015c]. In the Xenopus embryo, Zic1 expression overlaps with that of Engrailed 1 (En1) in the supraorbital region that directs coronal suture development and patterning, which is plausibly disrupted as a consequence of ZIC1 mutations [Twigg et al., 2015c]. ZIC orthologues in Drosophila and Xenopus are upstream regulators of the Wnt pathway [Merzdorf and Sive, 2006], being required for the activation of expression of the engrailed segment polarity gene [Benedyk et al., 1994; Kuo et al., 1998]. In mice, En1 is expressed in cells that migrate from the paraxial cephalic mesoderm to form and populate the coronal suture [Deckelbaum et al., 2012]. Indeed, mice with homozygous loss of En1 function have abnormal coronal suture fusion and an overall malformed skull [Deckelbaum et al., 2006].

Lambdoid NCS

Lambdoid CS (lNCS) is the least common type (1 in 33,000 live births), representing 1% of all CS and 3% of NCS [Boyadjiev and International Craniosynostosis Consortium, 2007; Wilkie et al., 2010; Greenwood et al., 2014; Heuzé et al., 2014]. Posterior plagiocephaly due to true lNCS must be differentiated from the much more common positional molding [Rhodes et al., 2014]. The synostosis may be unilateral or bilateral, and occurs more frequently as part of a complex CS [Rhodes et al., 2014].

The genetic basis of simple lNCS is unknown. Familial recurrence has been reported in two patients [Fryburg et al., 1995; Kadlub et al., 2008], and the reported incidence of CS in first-degree relatives is 3.9% [Greenwood et al., 2014]. Chromosomal rearrangements have been rarely described [Odell et al., 1987; Park et al., 1988]. More recently, Twigg and colleagues identified a c.256C>T (p.Arg86Cys) mutation in ERF, associated with reduced gene expression, in 1 out of 13 (7.6%) patients with either unilateral, bilateral, or complex lambdoid synostosis [Twigg et al., 2013]. This patient was a member of an affected family in which the mutation was accosiated with different clinical expressions. Rice et al. described that mice with a Gli3-null allele exhibited lambdoid CS due to the increased proliferation and differentiation of osteoprogenitor cells in the calvarial mesenchyme [Rice et al., 2010]. This study defined the first available animal model of lambdoid CS and confirmed the role of the Hedgehog (HH)-signaling pathway in membranous ossification of the skull.

Complex NCS

Complex CS (cxCS) presents with more than one fused suture and causes more severe distortion of the skull. Fusion of multiple sutures is more difficult to explain by intra-uterine constraint and is more likely to result from an abnormal genetic background. Although the involvement of multiple sutures can occur even in the absence of a clearly recognizable phenotype, the chances of a syndromic diagnosis are indeed higher among this group of patients [Cohen, 2000]. CxNCS accounted for 5.5% in a cohort of 144 patients with NCS [Wilkie et al., 2010], and ranged from 3% to 7.5 %, in more heterogeneous cohorts of 200 [Bessenyei et al., 2015] and 518 [Greene et al., 2008] CS patients, respectively. Within the cohort recruited through the International Craniosynostosis Consortium (https://genetics.ucdmc.ucdavis.edu/icc.cfm), 70 out of 660 (11%) NCS patients had cxNCS [Greenwood et al., 2014]. Mutations in CS-associated genes may result in atypical phenotypes, often misdiagnosed as unusual cxNCS. In particular, pathogenic FGFR2 mutations have been found in patients with apparently cxNCS [Wilkie et al., 2010]. SMAD6 mutations were identified in 2 of 8 (25%) probands with complex CS of both metopic and sagittal sutures from multi-generational families. Both probands and one of the affected parents carried the risk C allele of rs1884302, while an unaffected parent with SMAD6 mutation did not, a fact strengthening the proposed two-loci inheritance for at least some patients with NCS. There have also been reported patients with cxNCS involving sagittal, metopic and coronal sutures who were found to have TWIST1 mutations. Mutations in TWIST1 also cause Saethre-Chotzen syndrome [Sauerhammer et al., 2014a; Tahiri et al., 2015]. Therefore, genetic testing of SMAD6, FGFR1, 2, 3 and TWIST1 is indicated for individuals with cxNCS, and TCF12 and ZIC1 sequencing should be considered when mutations in other genes have been excluded.

A characteristic head shape associated with bilateral lambdoid and sagittal synostosis (BLSS) known as cranial dyssynostosis (OMIM #218350) presents with frontal bossing, turribrachycephaly, biparietal narrowing, occipital concavity, inferior ear displacement, and frequent developmental delay [Moore et al., 1998; Hing et al., 2009]. The resulting posterior vault constraint often leads to Chiari I malformation, and requires surgical cranial remodeling [Shukla, 2016]. In the original description of the syndrome, Neuhauser and colleagues [Neuhäuser et al., 1976] suggested an autosomal recessive inheritance within a family, though this was not confirmed in further studies [Bermejo et al., 2005]. Rhodes and colleagues reported the occurrence of this complex pattern in 11 out of 802 CS patients (1.4%), characterized by phenotypic variablity [Rhodes et al., 2010]. In particular, the exclusive fusion of sagittal and lambdoid sutures was observed only in 8 of the 11 patients, reducing the estimated prevalence to less than 1% in the CS cohort while two patients were later diagnosed as having Opitz and Potocki-Shaffer syndromes. BLSS with syndromic phenotype has been associated with chromosome abnormalities, involving the loci of putative genes regulating skull vault development such as MSX2 on 5q [Shiihara et al., 2004] and SOX6 on 11p [Tagariello et al., 2006]. Hing and colleagues described the largest series of 11 patients with BLSS diagnosed among 701 patients with various CS types. No mutations were identified in TWIST1, MSX2 and SOX6 and in the selected hot-spot regions of FGFR1, FGFR2, and FGFR3. An Xp11.22 deletion was documented in one of five tested individuals, who had spasticity, progressive apnea, and seizures and died at 4 months [Hing et al., 2009]. A patient with complex CS involving metopic and bicoronal sutures was reported to have a heterozygous 9.0 Mb deletion in the chromosomal region 7p21.1-p21.3 [Di Rocco et al., 2015].

Genes and developmental pathways as related to CS

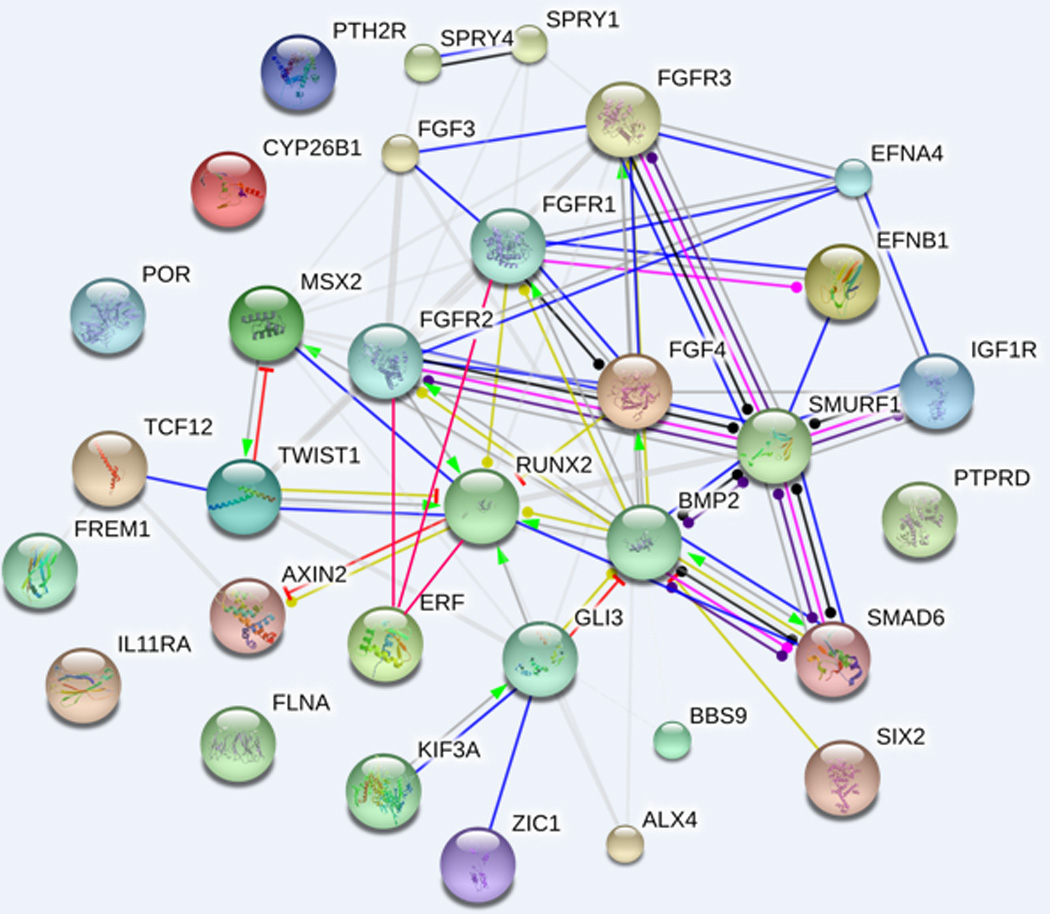

The following section will provide a more detailed description of the complex molecular networks integrating the genes that have been associated with CS. The extreme genetic heterogeneity of CS reflects the complex molecular networks underlying head morphogenesis, which comprises concerted skull/brain development. A diagram schematizing known interactions among the main CS-associated molecular pathways is proposed in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Craniosynostosis gene network.

The diagram shows known and predicted interactions among candidate genes implicated in the etiopathogenesis of craniosynostosis, discussed in the different sections (see text for details). The network was drawn using String (version 10.0) license-free software (http://string-db.org/), using the “molecular action” display format. Rounded nodes refer to gene/protein symbol included in the query; small nodes are for proteins with unknown 3D structure, while large nodes are for those with known structures. The lines connecting nodes represent the most relevant and best characterized types of protein-protein association within the networking genes, according to the following color codes: green = activation, red = inhibition, blue = binding, violet= catalysis, pink= post-translation modification, black= reaction, yellow= transcriptional regulation. Grey lines symbolize predicted links based on literature search (i.e. genes/proteins are co-mentioned in PubMed abstracts). Thicker lines represent stronger associations between proteins. The line ending shape represents the effect (whenever applicable) of the molecular action: arrow end= positive, transverse line end= negative, ball end= unspecified. The interactions were automatically integrated in the network by the software, with the medium confidence value set at 0.0400 (i.e. a 40% probability that a predicted link exists between two enzymes in the same metabolic map in the KEGG database: http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html). Additional interactions among ERF, RUNX2, FGFR1-3, GLI3 and BMP2, were added manually, given their functional implication in the molecular background described in this review.

The bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)/transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), hedgehog (HH), eph-ephrin and wingless-type MMTV integration site family (WNT) signaling pathways are the best understood developmental cascades governing the development of the skull. Individual genes within these pathways have been implicated in the etiology of CS, both in humans and animal models [Snider and Mishina, 2014]. Interestingly, most of these pathways are known to play pivotal roles in neural crest development, hence driving the morphogenesis of the craniofacial complex [Twigg and Wilkie, 2015b; Mishina and Snider, 2014].

Homeoproteins and homeotic genes

The msh homeobox 2 (MSX2) was the first CS causing gene discovered more than 20 years ago when a gain-of-function missense mutation was found in a family with syndromic Boston type CS [Jabs et al., 1993]. A second MSX2 mutation was described in an unrelated family [Florisson et al., 2013]. MSX2 is a homeodomain transcription factor expressed in the developing skull. In particular, MSX2 is primarily expressed in the neural crest which gives rise to frontal and craniofacial bones [Han et al., 2007], acting as a master regulator of gene expression in the embryo [Khadka et al., 2006; Attanasio et al., 2013]. Skull development is indeed tightly regulated by MSX2 dosage: gain-of-function (GoF) mutations and copy number increase, due to 5q35 trisomy, result in CS while MSX2 loss of function (LoF) results in parietal foramina (i.e. deficit of skull ossification) [Wilkie et al., 2000; Shiihara et al., 2004; Spruijt et al., 2005; Kariminejad et al., 2009]. MSX2 is thought to act upstream of the FGF pathway and appears to stimulate proliferation while inhibiting differentiation of osteogenic precursors in the suture. It was proposed that GoF mutations in the gene delay osteogenic differentiation and increase the pool of proliferating osteogenic cells that ultimately orchestrate suture ossification [Liu et al., 1999].

Aristaless-like homeobox 4 (ALX4), a homeodomain transcription factor involved in osteoblast regulation, is closely related to MSX2. It is required for neural crest cell migration and differentiation; hence, playing a critical role in craniofacial development [Kayserili et al., 2009; Dee et al., 2013]. Similarly to MSX2, GoF mutations of ALX4 cause CS (specifically sagittal NCS) [Yagnik et al., 2012], while LoF mutations result in parietal foramina [Mavrogiannis et al., 2001].

SIX2, another member of the aristaless gene family, was recently found deleted in patients with syndromic complex or sagittal synostosis [Hufnagel et al., 2016]. This gene is functionally involved in specifying the proliferation and migratory properties of neural crest cells during early embryo development. Along with other SIX genes, it is required for correct brain development and morphogenesis of the frontal craniofacial skeleton, counteracting HoxA2 function in mice [Garcez et al., 2014]. Interestingly, Six1-2-4 inactivation affects Bmp signaling through the downregulation of Bmp antagonists in facial neural crest cells.

ZIC1 is among the latest identified CS-associated genes and is discussed in section 3.2.3. This gene acts through the regulation of engrailed 1 (En1) expression in the embryo [Twigg et al., 2015c]. This homeoprotein is expressed in the skeletogenic mesenchyme and drives membranous calvarial ossification by regulating FGF signaling in calvarial osteoblasts [Deckelbaum et al., 2006].

BMP/TGFβ pathway

Both MSX2 and ALX4 are targets of the BMP/TGFβ pathway [Ishii et al., 2003; Rice et al., 2003]. This is consistent with our observation of a strong association of BMP2 with sNCS [Justice et al., 2012] with evidence of increased expression of this gene [Justice, 2014]. The identification of SMAD6 mutations acting in concert with the risk C allele of rs1884302 further corroborates the importance of this pathway in the etiology of NCS. SMURF1 LoF mutation was described in a case of metopic craniosynsotosis [Timberlake et al., 2016]. Both SMAD6 and SMURF1 mutations appear to enhance osteoblast differentiation through unopposed expression of RUNX2. Interestingly, BMP2 has been also associated with osteoporosis [Styrkarsdottir et al., 2003], and brachydactyly type A2 [Dathe et al., 2009] suggesting that, as is the case with MXS2 and ALX4, the BMP2 GoF mutation may be a factor in CS while decreased expression results in the opposite phenotype of skeletal under-development. Also, the BMP2-related intracellular osteogenic cascade is activated in calvarial cells isolated from prematurely fused sutures of affected individuals [Lattanzi et al., 2013]. The importance of the BMP pathway in the pathogenesis of CS is further corroborated by studies of animal models: BMP3 variants are found in brachycephalic dog breeds [Schoenebeck et al., 2012], mice with loss of BMP13 (also known as growth differentiation factor 6, Gdf6,) have coronal CS [Clendenning and Mortlock, 2012], while metopic CS is observed in mice with enhanced BMP signaling through constitutive activation of bmp receptor, type 1A (Bmpr1a) expression in cranial neural crest-derived structures [Komatsu et al., 2013]. In these models, craniosynostosis is believed to originate from an upregulation of Smad-dependent BMP signaling in the neural crest, resulting in enhanced ossification of the derived cranial bones [Komatsu et al., 2013]. Furthermore, there are observations that recombinant human BMP2 accelerates sutural bone formation in rabbits [Liu et al., 2009], whereas the BMP-antagonist Noggin, a candidate gene for nonsyndromic cleft lip/palate [Leslie et al., 2015], inhibits postoperative resynostosis in a mouse suturectomy model [Cooper et al., 2009].

Deregulation of TGFβ isoforms was observed in the sutural complex of a rabbit CS model [Poisson et al., 2004]. These isoforms appear to regulate suture patency and fusion through phosphorylation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (Erk1/2, ERK-MAPK cascade) and SMAD family member 2 (Smad2) proteins; thus, integrating the action of both the FGF and BMP signaling pathways [Opperman et al., 2006]. The importance of BMP/TGFβ signaling in the pathogenesis of CS is also underscored by the frequent occurrence of this finding in Loeys-Dietz syndrome, caused by TGFβ receptor-1 and -2 (TGFBR1, TGFBR2), SMAD3, and TGFB2 mutations [Loeys and Dietz, 1993], and in Shprintzen-Goldberg syndrome, caused by mutations in SKI proto-oncogene (SKI), a repressor of TGFβ [Doyle et al., 2012].

TWIST1 gene and related signaling

TWIST1 forms heterodimers with TCF12, a critical process in the molecular control of coronal suture development [Connerney et al., 2006]. Indeed, haploinsufficiency of either of these genes has been associated with coronal CS and Saethre-Chotzen phenotype [Sharma et al., 2013]. TCF12 mutations may exert their pathogenic effect through either FGF, BMP or HH signalling, given the pleiotropic role of TWIST1 in these pathways [Hornik et al., 2004]. TCF12 also functions as a SMAD cofactor, furhter implicating that the BMP/TGFβ pathway is the etiopathogenesis of CS [Yoon et al., 2011].

The fibroblast growth factor pathway

The fibroblast growth factor (FGF) pathway is one of the best understood signaling systems associated with CS etiopathogenesis. It comprises at least 23 ligands (FGF1–FGF23) and five receptors (FGFR1–FGFR5), essential for the initial stages of skeletal development. GoF mutations in either FGFR1, FGFR2 and FGFR3 genes or LoF of the TWIST family transcription factor 1 (TWIST1), a repressor of the FGR signaling, account for approximately 20% of patients with syndromic CS [Jabs et al., 1994; Muenke et al., 1994; Reardon et al., 1994; Meyers et al., 1995; Schell et al., 1995; Wilkie et al., 1995; Przylepa et al., 1996; el Ghouzzi et al., 1997; Howard et al., 1997; Muenke et al., 1997]. The complex CS syndromes (Saethre-Chotzen, Pfeiffer, Crouzon, Apert, Jackson-Weiss, Beare-Stevenson, Muenke, and Crouzon with acanthosis nigricans syndromes), caused by more than 60 mutations in these genes, are well defined and not the subjects of this review. The interested reader is referred to several comprehensive reviews of the molecular and clinical characteristics of these syndromes [Wilkie, 1997; Jabs, 1998; Passos-Bueno et al., 2008; Johnson and Wilkie, 2011].

The majority of the FGFR mutations result in constitutive activation of the receptor due to ligand-independent dimerization and activation, and/or changes in ligand specificity. The common thread of the syndromes caused by perturbations of FGF signaling is the excessive activation of the downstream Ras/MAPK pathway, with enhanced phosphorylation of Erk1/2 kinases [Kim et al., 2003; Park et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012]. Importantly, TGFβ-2 also activates the Erk-MAPK [Lee et al., 2006] cascade, suggesting that HH, FGF and BMP/TGFβ pathways may all converge on Erk1/2 or its downstream effectors, including the osteogenic master gene runt-related transcription factor (RUNX2). Our group, however, did not find enhanced ERK1/2 phosphorylation in primary osteoblasts from patients with sagittal NCS [Kim et al., 2014] suggesting an alternative causative pathway or genetic alteration in MAPK/ERK components downstream of ERK1/2. ERF encodes the Ets2 repressor transcription factor expressed in migratory cells of the neural crest that act downstream of Erk1/2 [Paratore et al., 2002]. Indeed, it was recently documented that ERF mutations cause coronal and complex syndromic CS [Twigg et al., 2013].

Ephrin genes

Eph-ephrin is another important developmental pathway that includes at least 14 tyrosine kinase receptors and 8 ligands [Lisabeth et al., 2013]. This signaling pathway plays a critical role in the formation of tissue boundaries in vertebrates. Two members of the Eph-ephrin signaling pathway have been implicated in CS. LoF mutations of ephrin-B1 (EFNB1) cause craniofrontonasal syndrome, an X-linked developmental disorder with features of frontonasal dysplasia and predominantly coronal CS [Twigg et al., 2004]. These authors proposed that, at least in females, disturbed tissue boundary formation at the developing coronal suture is responsible for the phenotype. Ephrin-A4 (EFNA4) was identified as a potential target for CS through studies of Twist1+/− mice strains exhibiting coronal CS due to defective fronto-parietal boundary. Enhanced Msx2 and reduced Epha4 expression were observed and suppression of the Msx2 in Msx2+/−; Twist1+/− double-mutant mice restored Epha4 levels and rescued the CS phenotype. Indeed, loss-of-function EFNA4 mutations were identified in three of 81 individuals with cNCS [Merrill et al., 2006]. Importantly, these studies demonstrate that at least part of the Eph-ephrin signaling system is integrated with the developmental pathways discussed above. This is corroborated by the fact that EphA4, through its interaction with Twist1, regulates both Erk1/2 and the BMP pathway complex Smad1/5/8 [Ting et al., 2009].

Hedgehog and Wnt signaling: the primary cilium environment in CS etiopathogenesis

HH and BMPs are both members of a complex signaling pathway that regulates early patterning events in fetal skeletogenesis [Iwasaki et al., 1997]. The role of HH signaling in the etiology of CS was unveiled by the identification of LoF mutations in member RAS oncogene family 23 (RAB23) gene in patients with Carpenter syndrome [Jenkins et al., 2007]. RAB23 is a repressor of HH signaling, which in turn induces members of the BMP gene family [Bitgood and McMahon, 1995]. Mutations in GLI family zinc finger 3 (GLI3), a downstream mediator of the Sonic HH, cause several multiple congenital anomaly syndromes and has been associated with metopic CS with polydactyly [McDonald-McGinn et al., 2010]. Indian HH is a pro-osteogenic factor that positively regulates intramembranous calvarial ossification by modulating BMP signaling [Lenton et al., 2011]. Interestingly, in a pattern analogous of BMP2 and BMP14 [Plöger et al., 2008], heterozygous missense mutations in Indian HH also result in brachydactyly [Ma et al., 2011].

The Wnt pathway promotes osteoblast differentiation and function. FGFR2-activating mutations downregulate a number of Wnt target genes [Mansukhani, 2005]. Mice with targeted disruption of the canonical Wnt inhibitor axis inhibition protein (Axin2) develop CS. Axin2 is needed for neural crest-derived frontal bone development [Yu et al., 2005; Li et al., 2015]. Indeed, studies of the Axin2−/− mice provided additional evidence for the interactions between the Wnt, BMP and FGF pathways in calvarial morphogenesis. Axin2 null mice displayed enhanced β-catenin activation, with expansion of osteoprogenitor cells, and activation of the BMP pathway, suggested by increased SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation [Yu et al., 2005; Yan et al., 2009]. Even though the precise mechanisms integrating these signaling systems are not well understood, it appears that β-catenin induces the BMP signaling, through FGF, by inhibiting its antagonist Noggin [Warren et al., 2003] thus promoting osteoblast differentiation while canonical Wnt signaling suppresses the FGF pathway by inducing TWIST1 [Reinhold et al., 2006].

Our group observed strong and reproducible association of sagittal CS with the Bardet-Biedl syndrome associated gene-9 (BBS9), named after the eponymous ciliopathy [Justice et al., 2012]. We have also observed significant BBS9 upregulation during in vitro osteogenic induction of calvarial osteoprogenitors, isolated from CS patients, and during the physiologic ossification of rat sutures (Lattanzi, unpublished data), suggesting the involvement of this gene in calvarial suture morphogenesis. Considering the lack of a reproducible craniofacial phenotype occurring in the best known ciliopathies, the view of CS as a manifestation of a ciliopathy may be unexpected. Nonetheless, sagittal CS is present in at least 50% of the patients with Sensenbrenner syndrome, a cranioectodermal dyplasia caused by mutations in four genes involved in ciliary biogenesis and function [Arts et al., 2011]. In addition to this paradigm example, other syndromes that may include CS phenotypes are those associated with mutations in ciliary genes: Mainzer-Saldino (mutations in IFT140), Carpenter (mutations in RAB23), and cranioectodermal dysplasias 2 and 4 (mutations in WDR35 and WDR19, respectively). Furthermore, the phenotype of mice deficient of kinesin family member 3A (Kif3a), a protein needed for cilia formation, includes metopic CS with other midline anomalies [Liu et al., 2014]. In this model the cranial neural crest cells in which Kif3a was conditionally deleted showed evidence of hyper-proliferation and ectopic Wnt responsiveness, linking this ciliopathy to the signaling pathways discussed above.

Besides direct inference from human CS phenotypes and animal models, it is worth noting that most of the key signaling pathways involved in craniofacial morphogenesis and CS molecular pathogenesis are somehow featured in the intense signaling and trafficking that occurs inside the primary cilium. In particular, Wnt and HH pathways are known to play pivotal role in cilium-related signaling. This is particularly relevant in the processes of neural crest induction and development [Chang et al., 2015]. Indeed, a craniofacial phenotype is observed in the ciliopathic Fuz mutant mouse due to excessive neural crest, leading to maxillary hyperplasia [Tabler et al., 2013]. Fuz is essential for normal trafficking inside vertebrate cilia, and closely interact with hedgehog signaling. Interestingly, the authors identified dysregulation of Fgf8 as the cause of the craniofacial defect observed in this ciliopathic mutant model, suggesting a shared pathogenic event between ciliopathies and craniofacial syndromes due to overactive FGF signaling [Tabler et al., 2013].

Interleukins

The interleukins IL-1 and IL-6 are involved in the regulation of bone homeostasis and bone cell functions. The initial indications that interleukins (ILs) may be implicated in the pathophysiology of the skull malformations came from observations that these molecules modulate the production of extracellular matrix molecules in periosteal fibroblasts of patients with Apert syndrome [Bodo et al., 1997]. The direct evidence that IL defects can cause CS came from the description of a novel autosomal recessive CS syndrome due to homozygous mutations of the interleukin receptor alpha gene (IL11RA) [Nieminen et al., 2011]. Since IL11RA and its ligand IL11 support both osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation it remains unclear if the CS occurs due to stimulation of osteoblast differentiation or inhibition of osteoclast function causing a defect of bone resorption. The integration of IL and BMP signaling is supported by their synergistic effect in enhancing bone formation in a rat model [Suga et al., 2003]. The overlapping phenotype of supernumerary teeth in patients with IL11 and RUNX2 mutations and mice with abnormal Wnt signaling [Wang et al., 2009] suggests that these genes may interact within the Wnt developmental pathway.

While enhanced osteoblast differentiation is the generally accepted mechanism of premature sutural fusion, it is plausible that inhibited osteoclast function with deficient bone resorption is at least partially responsible for this phenotype. Interleukin 11 receptor, alpha (Il11ra) deficient mice have a cell-autonomous inhibition of osteoclast differentiation resulting in CS [Nieminen et al., 2011]; another mice model with increased β-catenin has massively increased bone mass, and a decreased number of osteoclasts, but normal number of osteoblasts [Cohen, 2006]; and EphA4 receptor is a documented suppressor of osteoclast activity [Stiffel et al., 2014].

Other signaling pathways involved in CS etiopathogenesis

Based on these observations, one can safely predict that variants in other members of the signaling pathways discussed above will be associated with CS. Nevertheless, genes that are not directly related to these pathways have been associated with CS phenotypes. Antley-Bixler syndrome manifests with CS, long bone fractures, elbow synostosis and other anomalies. Overlapping clinical features, including coronal and lambdoid CS, are found in patients carrying null or hypomorphic mutations of CYP26B1 encoding a retinoic acid (RA)-metabolizing enzyme [Laue et al., 2011; Morton et al., 2016]. RA signaling has well documented effects in skeletal development; it induces premature osteoblast-to-preosteocyte transitioning during calvarial morphogenesis [Jeradi and Hammerschmidt, 2016]. In addition, an autosomal recessive phenotype resembling that of Antley-Bixler syndrome, associated with coronal CS plus genital anomalies due to steroid biogenesis defects, is caused by cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (POR) mutations [Flück et al., 2004]. The POR enzyme is also involved in RA signaling, and POR-dependent cholesterol synthesis is essential during limb and skeletal development [Ribes et al., 2007; Schmidt et al., 2009]. It is worth mentioning that a similar phenotype, without genital defects, has been attributed to heterozygous FGFR2 or FGFR3 mutations [Huang et al., 2005]. Additionally, Pfeiffer syndrome can feature elbow synostosis that may resemble that of Antley-Bixler syndrome [Hurley et al., 2004].

DNA repair and transcription defects are responsible for disorders with significant clinical heterogeneity known as DNA helicase disorders [Suhasini and Brosh, 2013]. Baller-Gerold syndrome, also known as CS-radial defects syndrome, is caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in the recQ helicase-like (RECQL4) gene. RECQL4 mutations have been also described in patients with Rothmund-Thompson and RAPADILINO syndrome and all three conditions share some clinical features (e.g., poikiloderma and radial ray defects) [Van Maldergem et al., 2006]. This has raised the possibility that these syndromes are phenotypic variants of the same disorder and not distinct disorders. The clinical phenotype of Baller-Gerold syndrome is complex and the differential diagnosis also includes VATER association, Roberts syndrome and Fanconi anemia. A patient with radial aplasia and bicoronal synostosis without additional malformations (i.e. narrow definition of Baller-Gerold syndrome) was found to have a nonsense TWIST1 mutation [Gripp et al., 1999] which causes Saethre-Chotzen syndrome. The contribution and significance of the DNA repair pathway to the pathogenesis of CS remains unclear at this time.

Finally, mutations in the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor gene (IGF1R) were found in three out of 186 patients with cNCS and sNCS [Cunningham et al., 2011]. IGF1 signaling plays an essential role during skeletal development and regulation of cellular adhesion and migration. Specifically, it is involved in cellular contractility and migration of suture calvarial osteoblasts of CS patients [Al-Rekabi et al., 2016]. Interestingly, among the consequences of the phosphorylation of IGF1R targets, RUNX2 and Wnt signaling are disinhibited, leading to the activation of the corresponding osteoblast differentiation cascades [Stamper et al., 2012].

The pivotal role of RUNX2

However diverse, the BMP/TGFβ, FGF, HH, eph-ephrin and WNT developmental pathways appear to share an important commonality: they all converge on the same downstream effector RUNX2 through SMAD or ERK1/2 [Hanai et al., 1999; Xiao et al., 2002; Suga et al., 2003; Lenton et al., 2011; Lisabeth et al., 2013]. This transcription factor acts as a key regulator of osteogenesis. RUNX2 deficiency results in deficient skull ossification in the context of cleidocranial dysplasia. Importantly, RUNX2 duplication [Mefford et al., 2010], triplication [Varvagiannis et al., 2013] and quadruplication [Greives et al., 2013] have been reported in patients with syndromic CS and there appears to be a direct correlation between the gene copy number and the severity of the phenotype. Our group identified two rare missense variants, M175R and R237C in two of 137 patients with sNCS. A variant of RUNX2 that has been presumed neutral is an in-frame deletion of 18 base pairs in the QA domain located in exon 2, resulting in a shorter stretch of 11 instead of 17 alanine residues. We documented that the shorter RUNX2 isoform is overrepresented 10-fold among the patients with sagittal craniosynostosis as compared to controls: 24% versus 2.3%, respectively [Yagnik et al., 2010]. Early expression of Runx2 causes CS and other skeletal defects in mice [Maeno et al., 2011] while loss of Runx2 causes a complete lack of ossification of both intramembranous and endochondral bone [Komori et al., 1997]. Osterix (Osx), a zinc finger-containing transcription factor downstream of Runx2, is also necessary for bone formation as no bone formation occurs in Osx null mice [Nakashima et al., 2002]. NEL-like 1 (NELL-1) is another downstream mediator of RUNX and direct transcriptional target of OSX (Sp7 transcription factor) that promotes osteoblastic differentiation through activation of MAPK. NELL-1 is upregulated in the fused coronal suture in humans. Similar to Runx2, MSX2, and ALX4, Nell-1 deficient mice present with deficient skull ossification [Desai et al., 2006] while over expression of Nell-1 cause CS in mice [Zhang et al., 2002].

Figure 2 synthesizes the network of molecular interactions among the best characterized CS candidate genes discussed in this paper; it is noteworthy that the main signaling pathways included in the picture tend to merge on the downstream interaction with RUNX2, as previously discussed.

NEURODEVELOPMENTAL ASPECTS OF CS

Long-term assessment of neurobehavioral outcomes identified learning disabilities (most often language or visual perception deficits) in 47% of affected school-aged children [Kapp-Simon, 1994] compared to 10% of unaffected children in the general population [Altarac and Saroha, 2007]. Another study showed that 30–50% of children with NCS may have neurocognitive deficits (problems with attention and planning, processing speed, visual spatial skills, language, reading, and spelling) that become more apparent as cognitive demands increase during school age [Kapp-Simon et al., 2007]. Nearly 30% of children with metopic CS have some form of speech and/or language delay, regardless of whether they had surgical repair [Kelleher et al., 2006], and deficits in executive function affect 50% of those with sagittal CS [Beckett et al., 2014]. Longitudinal evaluation of a large and carefully characterized group of children with single-suture CS documented consistently lower neurodevelopmental scores as compared to controls [Starr et al., 2012]. Neuropsychological testing in adolescents who underwent early surgery for NCS during infancy (<1 yr) documented visuospatial and constructional ability defects with associated visual memory recall deficits and attention deficits in 7% and 17% sNCS cases, respectively, while language deficits occurred in 30% of those with cNCS, all otherwise nonsyndromic [Chieffo et al., 2010]. It has been suggested that the cognitive profile of the affected individuals may result from increased intracranial pressure [Tamburrini et al., 2005; Inagaki et al., 2007]. It is likely, however, that the neurocognitive deficits in this population are a reflection of the changes in the brain that cannot be explained by skull constraint alone [Aldridge et al., 2002; Aldridge et al., 2005]. A recent study has further strengthened this notion by documenting altered neocortical connectivity in patients with sNCS [Beckett et al., 2014]. Thus, a primary abnormality of brain growth and development may be responsible for the long-term developmental outcomes in CS. Aberrant brain development may also play a role as an etiologic factor for CS through altered brain-dura-suture homeostasis.

IMAGING AND TREATMENT APPROACHES IN CS

Often the abnormal head shape is present at birth but the diagnosis is not suspected until the first months of life. Plain radiograph, three-dimensional computed tomography (3D-CT), and ultrasound (US) are the imaging modalities for patients with CS; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is reserved for complex syndromic cases with possible brain abnormalities. Although it has been suggested that imaging is not necessary for patients with typical sNCS [Agrawal et al., 2005], in practice some imaging could still be necessary for precise diagnosis and pre-surgical planning. In cases of plagiocephaly, careful clinical assessment may differentiate positional plagiocephaly from unilateral coronal or lambdoidal CS. When this is difficult, skull radiography remains a rapid and cost-effective option with low radiation load and specificity of 95% [Vannier et al., 1989] for children with a low probability of CS. However, this method has poor sensitivity for more complex and partial sutural synostosis.

High resolution US of the calvarial sutures has been successfully used both for confirmation of positional plagiocephaly [Regelsberger et al., 2006; Krimmel et al., 2012] and as a primary diagnostic method for CS with correct diagnosis in 95% of the patients [Simanovsky et al., 2009]. However, the inter-operator variability and the longer time required for detailed study have been deterrents. Since majority of children with positive US findings will still be examined by 3D-CT, most consider US to be a screening modality.

Traditionally 3D-CT has been the gold standard for diagnosis of CS. However, concerns with the high radiation load and its long-term biological effects including cancer have led to revision of this technique. It has been shown that with a carefully designed diagnostic protocol 3D-CT is rarely necessary for children with single suture CS [Schweitzer et al., 2012]. Given the fact that 3D-CT will remain a necessity for patients with complex and syndromic CS, significant efforts have been made to reduce the CT radiation load [Badve et al., 2013]. Recent work suggests a radiation dose reduction of 90% is possible without compromising image quality [Eckel et al., 2013].

Surgery in the first year of life remains the only treatment for CS. The main objective is to expand the intracranial volume in order to prevent the functional consequences of increased intracranial pressure, and to restore the cosmetic appearance of the head and face. The initial approach to treat CS with strip craniectomy in the 1890’s evolved to extensive cranial vault remodeling and has come full-circle back to endoscopic suturectomy and innovative techniques as spring-mediated cranioplasty [Okada and Gosain, 2012]. Cranial vault remodeling, while widely accepted as a standard of care in many centers, is associated with significant morbidity, extensive blood loss and prolonged anesthesia and hospitalization time. Developed in the late 1990’s [Jimenez and Barone, 1998], endoscopic suturectomy with subsequent orthotic helmet therapy is becoming an increasingly attractive option for both single-suture and complex CS [Jimenez and Barone, 2010; Rivero-Garvia et al., 2012; Sauerhammer et al., 2014b; Rottgers et al., 2016]. Despite reports that endoscopic suturectomy requires shorter operative and hospitalization times, less blood transfusion, and costs about half as much [Abbott et al., 2012] as does cranial vault remodeling, there is no consensus on the best operative techniques.

Although non-surgical treatment of CS is not available at this time, the increased awareness of the molecular mechanisms causing these defects has led to identification of potential targets for therapeutic interventions. FGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors are capable of preventing CS in mice with Fgfr2 mutation causing Crouzon syndrome [Eswarakumar et al., 2006]. Another proof-of-concept study of the mouse model of Apert syndrome has demonstrated that prenatal delivery of small molecule inhibiting the overactivated Ras/MAPK pathway not only completely rescued the skull phenotype but, when repeatedly administered postnatally, resulted in viable and fertile animals [Shukla et al., 2007].

These observations demonstrate that designing pharmacological compounds for prevention and treatment of CS is a realistic goal. Identification of at risk pregnancies through specific biomarkers or fetal DNA analysis of the maternal serum is a prerequisite to this task.

Table II.

Genes associated with different types of craniosynostosis.

| Gene | Affected suture | Syndromic | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sagittal | Metopic | Coronal | Lambdoid | Multiple | |||

| ALX4 | + | no | Mavrogiannis, 2001 | ||||

| BBS9 | + | no | Justice, 2012 | ||||

| BMP2 | + | no | Justice, 2012 | ||||

| EFNA4 | + | no | Merrill, 2006 | ||||

| EFNB1 | + | no | Twigg, 2015c | ||||

| + | yes | Twigg and Wilkie, 2015b | |||||

| ERF | + | + | + | yes+ | Twigg, 2013 | ||

| FGFR1 | + | no | Ye, 2016 | ||||

| + | no+ | Kress, 2000 | |||||

| FGFR2 | + | yes/no | Weber, 2001 | ||||

| + | yes/no | Johnson, 2000 | |||||

| + | yes/no | Wilkie, 2010 | |||||

| FGFR3 | + | yes/no | Wilkie, 2010 | ||||

| FREM1 | + | no | Vissers, 2011 | ||||

| IGF1R | + | + | no | Cunningham, 2011 | |||

| MSX2 | + | + | yes | Janssen, 2013 | |||

| PTH2R | + | + | yes | Kim, 2015 | |||

| RAB23 | + | yes | Jenkins, 2007 | ||||

| RUNX2 | + | no+ | Mefford, 2010 | ||||

| SIX2 | + | yes | Hufnagel, 2016 | ||||

| SMAD6 | + | + | + | no | Timberlake, 2016 | ||

| SMURF1 | + | no | Timberlake, 2016 | ||||

| SPRY1 | + | no | Timberlake, 2016 | ||||

| SPRY4 | + | no | Timberlake, 2016 | ||||

| TCF12 | + | yes/no | Sharma, 2013 | ||||

| + | yes | Di Rocco, 2014 | |||||

| + | yes | Le Tanno, 2014 | |||||

| + | yes | Paumard-Hernandez, 2015 | |||||

| + | yes | Piard, 2015 | |||||

| TWIST1 | + | + | no | Seto, 2007 | |||

| + | yes + | Ko, 2012 | |||||

| + | no + | Ye, 2016 | |||||

| + | no | Sauerhammer, 2014 | |||||

| + | no | Tahiri, 2015 | |||||

| ZIC1 | + | yes | Twigg, 2015c | ||||

no+ : only minor syndromic features present;

yes+: syndromic in most cases, rare NCS cases are described;

yes/no: both syndromic and NSC cases are described

SUMMARY.

The genetic causes of NCS remain largely unknown. Mutations in the genes causing CS syndromes and chromosomal abnormalities are not a common cause of NCS.

The causative role of the environment in NCS is yet to be confirmed.

Recent studies have shown that animal models and some patients with presumably NCS have mutations in specific genes (i.e., TCF12, ERF, TWIST, ALX4, RUNX2, FREM1) within interconnected signaling pathways. This may suggest that CS is a “developmental pathway disorder” where mutations in various members of the same or related pathways result in the same or similar phenotype. Oligogenic inheritance, incomplete penetrance, epigenetic factors or gene modulators are possible explanation for the general lack of Mendelian segregation.

Linkage, association and targeted candidate gene approaches have not yielded the expected results and exome or genome association and sequencing studies may allow identification of the causative genes and loci.

Early diagnosis and referral to a center with substantial experience in evaluation and treatment of CS substantially improves outcomes. There is a tendency for less radiation-intensive imaging techniques and less invasive surgical techniques.

Neurodevelopmental issues are common and cannot be entirely attributed to the skull phenotype or the surgical trauma. Better understanding of the brain-dura-suture axis may allow better treatment approaches.