Abstract

Recently, MHC class I molecules have been shown to be important for the retraction of synaptic connections that normally occurs during development [Huh, G.S., Boulanger, L. M., Du, H., Riquelme, P. A., Brotz, T. M. & Shatz, C. J. (2000) Science 290, 2155-2158]. In the adult CNS, a classical response of neurons to axon lesion is the detachment of synapses from the cell body and dendrites. We have investigated whether MHC I molecules are involved also in this type of synaptic detachment by studying the synaptic input to sciatic motoneurons at 1 week after peripheral nerve transection in β2-microglobulin or transporter associated with antigen processing 1-null mutant mice, in which cell surface MHC I expression is impaired. Surprisingly, lesioned motoneurons in mutant mice showed more extensive synaptic detachments than those in wild-type animals. This surplus removal of synapses was entirely directed toward inhibitory synapses assembled in clusters. In parallel, a significantly smaller population of motoneurons reinnervated the distal stump of the transected sciatic nerve in mutants. MHC I molecules, which traditionally have been linked with immunological mechanisms, are thus crucial for a selective maintenance of synapses during the synaptic removal process in neurons after lesion, and the lack of MHC I expression may impede the ability of neurons to regenerate axons.

Keywords: β2-microglobulin, motoneuron, spinal cord, synapse elimination, nerve lesion

The wiring of the brain is an immensely complex process, dependent not only on the “making” of new communication points, synapses, but also on the elimination of exuberant or inappropriate synapses during development. The underlying mechanisms for this elimination in the central nervous system (CNS) have been virtually unknown, but recently a role in this process has been suggested for MHC class I molecules. Thus, in mice with gene depletions for crucial components of MHC class I signaling, there was a disruption of the normally occurring perinatal segregation of retinal afferents in the lateral geniculate nucleus (1). This finding led to the conclusion that MHC class I signaling is important for the removal of exuberant synaptic connections during development, and, because many populations of neurons have been shown to harbor mRNAs for MHC class I molecules (2, 3), it was suggested that the neurons themselves were involved in the signaling.

Synapses may be eliminated or detached also in the adult. Such an elimination can be induced by axon transection, which is followed by an extensive detachment of presynaptic terminals from perikarya and dendrites of axotomized neurons (4-12). We have previously shown that mRNAs for MHC class I and, in particular, β2-microglobulin (β2m), which is a cosubunit for MHC class I, are up-regulated in spinal motoneurons after peripheral axotomy (13). Axotomy also induces an increase in the expression of the MHC class I protein (14). In vitro, cytokines may induce MHC class I expression in neurons (13, 15). Here we have tested the hypothesis that the elimination of synapses after lesion in the adult depends, at least in part, on the presence of MHC class I expression in the same way as has been shown for synapse elimination during normal development. Thus, a peripheral nerve transection was performed in β2m or transporter associated with antigen processing 1 (TAP1)-null mutant mice. In these mice, the expression of MHC class I molecules at the cell surface is severely impaired, in that β2m is the obligatory light chain of most MHC class I molecules (16) and TAP1 is a required transporter for loading peptides onto MHC class I molecules before their transport to the cell surface (17).

Materials and Methods

Animals. B6.129P2-B2mtm1Unc stock no. 002087 and B6.129S2-TaptmArp stock no. 002944 transgenic mice were generated as described (17, 18). The mutant mice and C57BL/6J stock no. 000664 control mice were bred and maintained at the Microbiology and Tumor Biology Center, Karolinska Institutet. β2m-/- and TAP1-/- mice were backcrossed for 6-11 generations on the C57BL/6 background. Animals were used at an age of 6-8 weeks, and all experimental procedures were approved by the local ethics committee (Stockholms Norra Djurförsöksetiska Nämnd).

Surgical Procedures and Tissue Preparation for Synaptological Study. Animals were anesthetized with a mixture of midazolam (Dormicum, Roche Diagnostics; 1.25 mg/ml) and a combination of fentanyl citrate (0.08 mg/ml) and fluanisone (2 mg/ml) (combined in Hypnorm, Janssen). The mixture was given i.p. at 0.2 ml per 25 g of body weight. The mice were then subjected to a left sciatic nerve transection at the obturator tendon level. A 2-mm-long segment of the distal stump was removed to avoid regeneration. Unoperated mice of the same litters were used as controls. All mice (operated animals at 1 week after lesion) were killed by CO2 inhalation, and the vascular system was rinsed by transcardial perfusion with Millonig's buffer (300 mOsm; pH 7.4). For immunohistochemical detection of synaptophysin (B6, β2m-/-, and TAP1-/- lesioned and unoperated; n = 6 in each group) or electron microscopy (B6 and β2m-/-, lesioned and unoperated; n = 3 in each group), the animals were fixed, and the spinal cords were dissected out and cut for immunofluorescence or ultrastructural analysis by using standard protocols (9, 19). A detailed description is given in Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

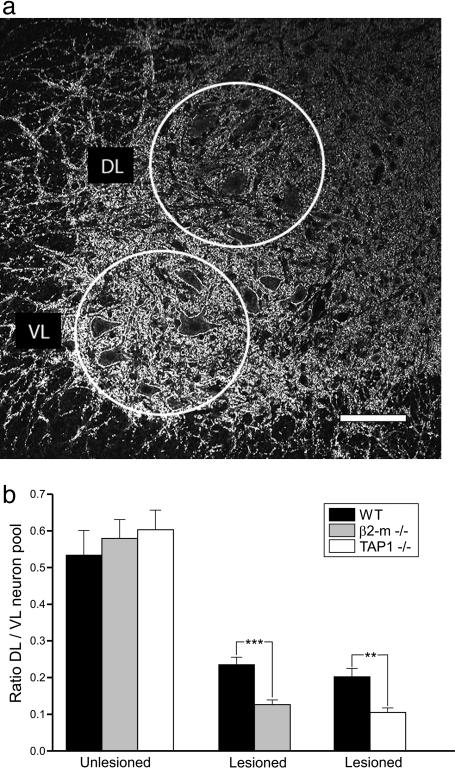

Immunohistochemistry. A primary rabbit anti-human synaptophysin antibody (Dako, 1:100) was used. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C in a humid chamber with primary antiserum diluted in a solution containing BSA and Triton X-100 in 0.01 M PBS. After rinsing in PBS, the sections were incubated with a Cy2-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch; 1:200) for 45 min in a humid chamber at room temperature. The sections were then rinsed in PBS, mounted in a mixture of glycerol/PBS (3:1), and observed with a laser scanning confocal microscope (Bio-Rad). Excitation wavelength was 488 nm for Cy2 fluorescence. For quantitative measurements of synaptophysin immunoreactivity, images of the L5 ventral horn were captured at a final magnification of ×200, with microscopical setting kept the same for all slides. Quantification was performed with the enhance contrast and density slicing feature of image software (version 1.55; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda). The number of positively stained pixels was measured in two areas in the lateral motor nucleus in three to six serial sections from each spinal cord (total number: 12 operated wild-type, 6 operated β2m-/-, 6 operated TAP1-/-, and 3 of each of unoperated wild-type, β2m-/-, and TAP1-/- animals) using an elliptic capturing figure. The dorsolateral (DL) area of the motor nucleus, in which injured sciatic motoneurons were located, was compared with the ventrolateral (VL) pool containing motoneurons with intact axons innervating proximal hind limb muscles. The DL/VL ratio of the pixel density between injured and intact neuron pools was calculated for each section and then as mean value for each spinal cord.

Analysis of Ultrathin Sections. Neurons with large cell bodies (>35 μm in diameter), found in the sciatic motoneuron pool and cut in the nuclear plane, were identified as α motoneurons by the presence of C-type nerve terminals (20). Neurons were identified as axotomized based on the occurrence of chromatolytic changes in the cell bodies (9). The surface of the cells was then photographed at a magnification of ×8,000, printed at a final magnification of ×19,520, and mounted together. Synaptic terminals apposing the motoneuron somata were identified, and their numbers per 100-μm cell membrane and the membrane covering of all terminals in percent of membrane length were calculated. The terminals were classified in type F (with flattened synaptic vesicles), type S (with spherical synaptic vesicles), and type C (with a subsynaptic cistern), according to the nomenclature of Conradi (20). The distance between consecutive nerve terminals covering the motoneurons was also determined. A total of 24 sciatic motoneurons (two neurons per animal in four groups of three animals: normal wild-type, normal β2m-/-, axotomixed wild-type, and axotomized β2m-/-) were studied in this way.

Retrograde Tracing. The technique for retrograde labeling of motoneurons with Fast Blue and counting procedures has been described (21). Motoneurons were labeled at 3 weeks after a 1-mm-long resection of the sciatic nerve, either proximal or distal to the lesion. A detailed description of the methods, including quantification procedures, is given in Supporting Text.

Statistical Analysis. Data were analyzed with a two-tailed Student t test at P < 0.05 (*), P < 0.01 (**), and P < 0.001 (***), using statistical functions in prism 4.0 (GraphPad, San Diego), or with a two-tailed Mann-Whitney rank sum test.

Results

Larger Loss of Synaptophysin Immunoreactivity in Lesioned Motor Pools of β2m-/- and TAP1-/- Mice. Quantitative measurements of the immunoreactivity for the synaptic protein synaptophysin were performed in the spinal cord motor nuclei 1 week after lesion. We compared the DL ventral horn containing lesioned sciatic motoneurons with the VL part harboring motoneurons supplying more proximal hind limb muscles not affected by the lesion (Fig. 1a). In both unoperated wild-type and mutant mice, the immunoreactivity in the DL was quantitatively similar but had a significantly lower density when compared to the VL (DL/VL ratio wild-type, 0.53 ± 0.07 mean ± SEM; β2m-/-, 0.58 ± 0.05; TAP1-/-, 0.60 ± 0.05; n = 3 for all groups; Fig. 1b). One week after sciatic nerve transection, there was a 62% reduction of synaptophysin immunoreactivity in the DL in wild-type mice (DL/VL ratio, 0.20 ± 0.02, n = 6), but in both β2m-/- (DL/VL ratio, 0.13 ± 0.01, n = 6) and TAP1-/- (DL/VL ratio, 0.11 ± 0.01, n = 6) animals, the decrease in immunoreactivity was significantly more prominent (78% in β2m-/- and 82% in TAP1-/-) (Fig. 1b; P < 0.001 and P < 0.01, respectively; two-tailed Student's t test) that is there was a 50% further decrease in synaptophysin immunoreactivity after lesion as compared to wild-type animals.

Fig. 1.

The reduction of synaptophysin immunoreactivity in axotomized motor pools is stronger in animals lacking functional MHC class I than in wild-type mice. (a) Immunofluorescence micrograph showing the studied areas in the spinal motor nuclei, the DL area representing the location of lesioned sciatic motoneurons, and the VL area intact motoneurons to the proximal hind limb. (Scale bar, 100 μm.) (b) Quantitative estimates of levels of immunoreactivity at 1 week after sciatic nerve transection show significantly stronger reductions in β2m-/- and TAP1-/- than in wild-type animals.

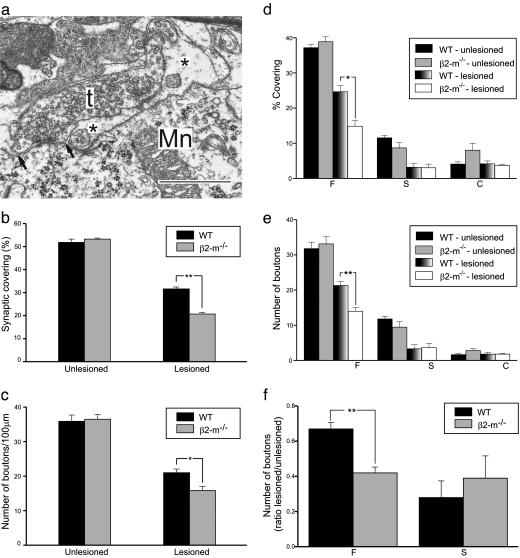

Larger Elimination of Synapses from Axotomized Motoneurons in β2m-/- Mice. Also at the ultrastructural level, the general density of synaptic terminals and other cellular elements appeared identical in normal β2m-/- and wild-type motor nuclei. One week after a sciatic nerve transection in β2m-/- and wild-type mice, axotomized α-motoneurons (mean diameter, >35 μm) were identified ultrastructurally with morphological changes characteristic for axotomized neurons, i.e., chromatolysis, displacement of the cell nucleus, and an elimination of synapses from the cell body (9). For three wild-type and three β2m-/- mice, two motoneurons in each animal were analyzed in detail with regard to synaptic covering, as well as number and types of synapses on the cell body, and compared with motoneurons with a corresponding location in unoperated animals. In the latter group, the cell soma synaptic covering and number of synapses on motoneurons in wild-type and β2m-/- mice were very similar (covering 53.3 ± 0.5% versus 51.9 ± 1.4%; number of synapses 35.9 ± 1.1 versus 36.5 ± 2.0 per 100-μm membrane) (Fig. 2). After lesion, nerve terminals were partially displaced from the cell body membrane by astrocyte-like processes (Fig. 2a), and quantitative analysis revealed a clear reduction in covering in both types of animals (Fig. 2b). This effect was significantly larger in β2m-/- mice, with a mean synaptic cell soma covering of only 20.7 ± 0.8% compared with 31.6 ± 1.1% in wild-type animals. Thus, the reduction was ≈50% larger in mutant mice. The absolute number of remaining, attached synapses after lesion did not differ as much between mutant (15.9 ± 0.9 per 100-μm membrane) and wild-type animals (21.0 ± 1.5 per 100-μm membrane) as the covering values, but there was still a significantly more extensive reduction in the mutants (>30%; Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Synaptic detachment from cell bodies of axotomized motoneurons is stronger in animals lacking functional MHC class I than in wild-type mice with a selective surplus removal of putatively inhibitory type F nerve terminals. (a) Electron micrograph showing a partially detached nerve terminal (t) on an axotomized sciatic motoneuron (Mn) in the spinal cord at 1 week after lesion. Note the presence of a finger-like astrocytic process (*) between the motoneuron membrane and a large part of the terminal. The arrows denote the borders for the apposition of the terminal to the motoneuron. (Bar, 1 μm.) The detachment of synaptic terminals (b) and the reduction in number of nerve terminals apposing the motoneuron cell soma (c) are larger from motoneurons in β2m-/- mice than in wild-type animals at 1 week after sciatic nerve transection. Detailed analysis of the synaptic covering and number of synaptic terminals on the cell body of axotomized motoneurons reveals that the surplus removal of synapses in mutant mice is confined to type F nerve terminals with a putative inhibitory function (d and e). The extra removal of type F terminals in mutants abolishes the selective maintenance of a pool of type F terminals in wild-type animals (f).

Surplus Elimination of Synapses in β2m-/- Mice Is Confined to Putative Inhibitory Synapses in Clusters. To explore whether there was a qualitative difference in the pattern of synaptic detachment between β2m-/- and wild-type mice, the fate of various types of synapses was analyzed. Two main categories of synaptic terminals on motoneurons can be classified based on the shape of their synaptic vesicles, type S terminals with spherical vesicles, and the F type with flattened vesicles, both seen in aldehyde-fixed material (20). The latter type contains the inhibitory amino acid glycine (22), whereas a large proportion of type S terminals harbor glutamate as excitatory transmitter (12). A minority of the type S terminals are large and termed C type, with acetylcholine (23) as transmitter substance. The quantitative analysis showed that the more extensive synapse detachment in β2m-/- animals could be entirely attributed to type F nerve terminals, whereas type S terminals were removed to the same extent in wild-type and mutant mice (Fig. 2 d and e). The pattern in β2m-/- animals, where the proportion of remaining type F and S terminals is the same, sharply contrasts to the normal response to axotomy, which leads to a larger elimination of excitatory type S compared to inhibitory type F inputs (12) (Fig. 2f).

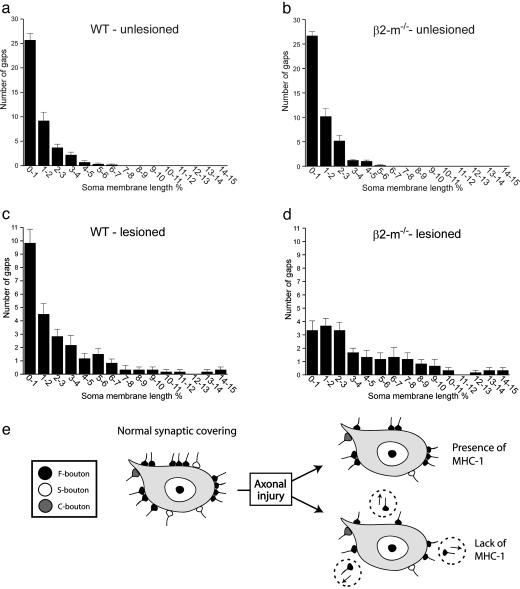

One characteristic feature of the synaptic elimination process after axon lesion in normal animals is that there are remaining “clusters” of nerve terminals at specific points along the cell membrane of the injured motoneuron; that is, many remaining nerve terminals are located close together (Fig. 3 a and c). This pattern was strikingly different in β2m-/- mice with a profound loss of tightly located (<1% of the cell body circumference in the nuclear plane) terminals, whereas the spacing of terminals with larger distances in between remained very similar in β2m-/- and wild-type animals (Fig. 3 a-d).

Fig. 3.

The surplus removal of synaptic terminals in β2m-/- mice is preferentially directed toward clusters of nerve terminals. Graphs show the distribution of distances between nerve terminals along the cell soma membrane of motoneurons. The distances are calculated in percentage of total soma membrane length of the neuron in the nuclear plane. In unlesioned motoneurons, the intervals between nerve terminals are very similar in mutant and wild-type animals (a and b). In lesioned motoneurons at 1 week after axotomy, there is a distinct difference between the two groups of animals with a much more prominent loss of closely spaced terminals in β2m-/- mice compared with wild-type mice (c and d). The schematic drawing in e summarizes the main differences in the synaptic removal process between wild-type and β2m-/- mice.

Taken together, the interpretation of the morphological data suggests that the apparently preferential removal of excitatory inputs to motoneurons after axon lesion in normal animals should rather be seen as an elimination process, in which a subset of inhibitory inputs is kept in clusters on the cell body surface. This selective maintenance of an inhibitory influence seems to depend directly on an intact MHC class I expression (Fig. 3e).

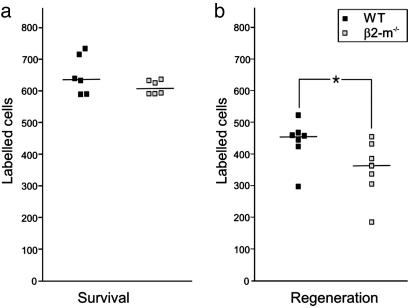

Impaired Axon Regeneration in β2m-/- Mice. To test the possibility that a remaining inhibitory input after lesion in wild-type mice inf luences motoneuron survival and/or regeneration, we counted the number of sciatic motoneurons surviving a 1-mm-long resection of the sciatic nerve and regenerating new axons into the distal nerve stump after this lesion. Thus, the retrograde tracer Fast Blue was applied either to the proximal nerve stump counting the number of surviving motoneurons or to the distal stump counting the number of motoneurons that had succeeded to bridge the nerve gap and sent new axons into the distal nerve stump. This test was performed at 3 weeks after the sciatic nerve resection, when both axon regeneration (W. Wallquist, personal communication) and motoneuron death (24) can be expected to have occurred. No difference in the number of surviving motoneurons capable of retrograde transport of Fast Blue was noted between wild-type and β2m-/- mice (Fig. 4a), whereas there was a significantly lower number of regenerating sciatic motoneurons in β2m-/- mice compared to wild-type animals (P < 0.05; two-tailed Mann-Whitney rank sum test; Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Hampered axon regeneration, but no difference in motoneuron number in β2m-/- compared with wild-type mice at 3 weeks after a 1-mm resection of the sciatic nerve. The number of motoneurons retrogradely labeled with Fast Blue after application to the proximal stump is shown in a. The numbers are very similar in the two groups of animals. (b) The number of retrogradely labeled motonerons after application to the distal stump is significantly lower in β2m-/- animals. The numbers from individual animals are given, with horizontal lines denoting median values.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that expression of the immune recognition molecule MHC I has a direct influence on the outcome of a neuron after lesion. Thus, MHC I is crucial for the selective maintenance of putative inhibitory synapses in clusters on neurons after lesion, and, in its absence, fewer lesioned neurons are able to regenerate new axons. Our results contrast previous observations of aberrant and excessive synaptic contacts present in certain CNS regions in animals lacking functional MHC I, presumably because of a less efficient developmental pruning of the synaptic network (1). These opposite patterns may seem less paradoxical when considering the divergent effects of MHC I molecules in the immune system. Some effector mechanisms are triggered, whereas other are prevented by MHC I molecules. This divergence depends on different receptors transducing activating or inhibitory signals upon MHC I recognition. Such different receptor types can even be expressed by the same cells, particularly in cells of the innate immune system (e.g., the different families of natural killer cell receptors, which can be directed against classical as well as nonclassical MHC I molecules; refs. 25-28). There are situations where the presence of MHC class I on a cell membrane can exert a dominating influence and inhibit interacting immune cells from attacking it. It cannot be excluded that the phenomenon observed here may represent a similar phenomenon exerted at the synaptic level.

One obvious task for future research is to identify in which cells the MHC I molecules exert their effect on the synaptic detachment: the motoneuron itself, presynaptic neurons, or glial cells. Although the mere existence of MHC class I molecules within the CNS has been debated for many years, it now seems obvious that a number of subsets of neurons normally express these molecules in vivo (2, 3, 13). Also, various experimental conditions may regulate MHC class I levels in neurons. For example, an up-regulation of MHC class I expression is seen in motoneurons after axotomy (13, 14) and hippocampal neurons in response to kainate-induced seizures (2), whereas there is a down-regulation in lateral geniculate nucleus neurons deprived of visual input (2). After axotomy of motoneurons, MHC class I is also up-regulated in microglia surrounding axotomized motoneurons (13, 29, 30), and may be induced in astrocytes both in vitro and in vivo (31). The fact that neurons seem to express “nonclassical” non- or oligomorphic MHC Ib molecules, whereas glial cells express “classical” polymorphic MHC Ia (30), may offer an opportunity to further characterize the recognition and signaling pathways in the response described here. However, because the only spinal cord element that is directly affected by the injury that induces the response in the spinal cord is the axotomized motoneuron, it is reasonable to believe that the motoneuron itself has a pivotal role in the signaling events leading to this response.

The reason for stripping off synapses from the cell surface of axotomized neurons has been related to a shifting state of the neurons from one subserving distribution of information to one where mechanisms for survival and repair are warranted (9). By removing synaptic contacts, the full capacity of the metabolic machinery of the injured neuron may then be used for repair. With this background, it may appear puzzling that the functional consequence of the maintenance of synaptic contacts by MHC class I expression seen here seems to be a higher degree of successful axon regeneration among severed motoneurons. One plausible explanation may be that the inhibitory input in clusters maintained by MHC class I serves to counteract any excitotoxic influence on lesioned cells, which could seriously affect the necessary basic machinery for cell survival, or in this case axon regeneration (32, 33). Indications that it may be essential to maintain a particular kind of input have been given previously in a study of amino acid-containing nerve terminals on cat motoneurons after axotomy in the ventral funiculus of the spinal cord (12). After this very proximal lesion to the axon, there was an almost complete disappearance of the excitatory, glutamatergic input to lesioned motoneurons, whereas a much larger proportion of inhibitory, glycinergic inputs remained.

In summary, our data provide evidence that MHC class I molecules, traditionally viewed as solely involved in immuno-recognition, play an important role for stabilizing specific synaptic contacts in the adult nervous system after lesion, which may in turn be important for the ability of lesioned neurons to generate new axons after axotomy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council, Marianne och Marcus Wallenbergs Stiftelse, Stiftelsen Marcus och Amalia Wallenbergs Minnesfond, and the Karolinska Institutet. A.L.R.O. was supported by a Postdoctoral Scholarship from Fundaçao de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Sao Paulo. K.K. was supported by The Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research.

Author contributions: A.L.R.O., S.T., F.P., and S.C. designed research; A.L.R.O., S.T., O.L., and H.L. performed research; A.L.R.O., S.T., O.L., and H.L. analyzed data; and T.H., K.K., and S.C. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: β2m, β2-microglobulin; TAP1, transporter associated with antigen ing 1; DL, dorsolateral; VL, ventrolateral.

References

- 1.Huh, G. S., Boulanger, L. M., Du, H., Riquelme, P. A., Brotz, T. M. & Shatz, C. J. (2000) Science 290 2155-2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corriveau, R. A., Huh, G. S. & Shatz, C. J. (1998) Neuron 21 505-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindå, H., Hammarberg, H., Piehl, F., Khademi, M. & Olsson, T. (1999) J. Neuroimmunol. 101 76-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blinzinger, K. & Kreutzberg, G. (1968) Z. Zellforsch. Mikrosk. Anat. 85 145-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sumner, B. E. H. (1975) Exp. Neurol. 49 406-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, D. H., Chambers, W. W. & Liu, C. N. (1977) Exp. Neurol. 57 1026-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delgado-Garcia, J. M., Del Pozo, F., Spencer, R. F. & Baker, R. (1988) Neuroscience 24 143-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindå, H., Cullheim, S. & Risling, M. (1992) J. Comp. Neurol. 318 188-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aldskogius, H. & Svensson, M. (1993) Adv. Struct. Biol. 2 191-223. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tseng, G. F. & Hu, M. E. (1996) Acta Anat. 155 184-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brännström, T. & Kellerth, J.-O. (1998) Exp. Brain Res. 118 1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindå, H., Shupliakov, O., Örnung, G., Ottersen, O. P., Storm-Mathisen, J., Risling, M. & Cullheim, S. (2000) J. Comp. Neurol. 425 10-23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindå, H., Hammarberg, H., Cullheim, S., Levinovitz, A., Khademi, M. & Olsson, T. (1998) Exp. Neurol. 150 282-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maehlen, J., Nennesmo, I., Olsson, A. B., Olsson, T., Schröder, H. D. & Kristensson, K. (1989) Brain Res. 481 368-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neumann, H., Cavalie, A., Jenne, D. E. & Wekerle, H. (1995) Science 270 720-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zijlstra, M., Bix, M., Simister, N. E., Loring, J. M., Raulet, D. H. & Jaenisch, R. (1990) Nature 344 742-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Kaer, L., Ashton-Rickardt, P. G., Ploegh, H. L. & Tonegawa, S. (1992) Cell 71 1205-1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koller, B. H., Marrack, P., Kappler, J. W. & Smithies, O. (1990) Science 248 1227-1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hellström, J., Arvidsson, U., Elde, R., Cullheim, S. & Meister, B. (1999) J. Comp. Neurol. 411 578-590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conradi, S. (1969) Acta Physiol. Scand. Suppl. 332 5-48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Novikova, L., Novikov, L. & Kellerth, J.-O. (1997) J. Neurosci. Methods 74 9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Örnung, G., Shupliakov, O., Lindå, H., Ottersen, O. P, Storm-Mathisen, J., Ulfhake, B. & Cullheim, S. (1996) J. Comp. Neurol. 365 413-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Connaughton, M., Priestly, J. V., Sofroniew, M. V., Eckenstein, F. & Cuello, A. C. (1986) Neuroscience 17 205-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baba, N. Koji, T., Itoh, M. & Mizuno, A. (1999) Brain Res. 827 122-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kärre, K., Ljunggren, H. G., Piontek, G. & Kiessling, R. (1986) Nature 319 675-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ljunggren, H. G. & Kärre, K. (1990) Immunol. Today 11 237-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moretta, L., Biassoni, R., Bottino, C., Cantoni, C., Pende, D., Mingari, M. C. & Moretta, A. (2002) Microbes Infect. 4 1539-1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Natarajan, K., Dimasi, N., Wang, J., Mariuzza, R. A. & Margulies, D. H. (2002) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20 853-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Streit, W. J., Graeber, M. B. & Kreutzberg, G. W. (1989) J. Neuroimmunol. 21 117-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lidman, O., Olsson, T. & Piehl, F. (1999) Eur. J. Neurosci. 11 4468-4472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jarosinski, K. W. & Massa, P. T. (2002) J. Neuroimmunol. 122 74-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi, D. W. (1992) J. Neurobiol. 23 1261-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heath, P. R. & Shaw, P. J. (2002) Muscle Nerve 26 438-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.