Abstract

The robust regenerative capacity of planarian flatworms depends on the orchestration of signaling events from early wounding responses through the stem cell enacted differentiative outcomes that restore appropriate tissue types. Acute signaling events in excitable cells play an important role in determining regenerative polarity, rationalized by the discovery that sub-epidermal muscle cells express critical patterning genes known to control regenerative outcomes. These data imply a dual conductive (neuromuscular signaling) and instructive (anterior-posterior patterning) role for Ca2+ signaling in planarian regeneration. Here, to facilitate study of acute signaling events in the excitable cell niche, we provide a de novo transcriptome assembly from the planarian Dugesia japonica allowing characterization of the diverse ionotropic portfolio of this model organism. We demonstrate the utility of this resource by proceeding to characterize the individual role of each of the planarian voltage-operated Ca2+ channels during regeneration, and demonstrate that knockdown of a specific voltage operated Ca2+ channel (Cav1B) that impairs muscle function uniquely creates an environment permissive for anteriorization. Provision of the full transcriptomic dataset should facilitate further investigations of molecules within the planarian voltage-gated channel portfolio to explore the role of excitable cell physiology on regenerative outcomes.

Keywords: Voltage-operated Ca2+ channels, neuromuscular signaling, regeneration, transcriptome

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The purpose of Ca2+ signaling processes is to effect information delivery (Boulware and Marchant, 2008). This encompasses a dual ‘conductive’ and ‘instructive’ role for Ca2+: namely, understanding how Ca2+ signals are built and transmitted in a variety of guises across different distance and time scales (the ‘conductive’ role) but also how information is decoded from specific Ca2+ signaling cues to impact cell fate (the ‘instructive’ role). A range of methodological advances have propelled our understanding of the mechanics of Ca2+ signaling in diverse cells and tissues, progress that has arguably eclipsed our understanding of the instructive role of Ca2+ in shaping transcriptional outcomes and cell fate in vivo, questions which intellectually intrigued the field during the early decades of Ca2+ signaling research. Visualization of endogenous Ca2+ signals in developmental models, yet alone their manipulation, has proven challenging underscoring the difficulty of establishing links between Ca2+ signaling and paradigms of axis/tissue specification (Webb and Miller, 2003; Whitaker, 2006; Rosenberg and Spitzer, 2011; Deng et al., 2015; Delling et al., 2016; Hao et al., 2016).

One model that has captivated our interest for studying the instructive role of Ca2+ signaling on stem cell behavior is the planarian flatworm, a classic model for studying tissue regeneration. Planarian flatworms have long been used as a model for studying regenerative biology because of their inherent ability to regenerate and rejuvenate their tissues (Newmark and Sánchez-Alvarado, 2002; Elliot and Sanchez Alvarado, 2012). Over the last decade, remarkable progress has been made in defining the signaling pathways and stem cell populations that underpin this ability (Forsthoefel and Newmark, 2009; Reddien, 2011; Elliot and Sanchez Alvarado, 2012; Rink, 2013) enabling targeted manipulation of regenerative capacities (Wagner et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2013; Sikes and Newmark, 2013). Ca2+ signaling events have been shown to play a role in determination of anterior-posterior polarity during the early phase of planarian tissue regeneration: several drugs that perturb Ca2+ homeostasis cause polarity defects if applied contemporaneously, or shortly after, tissue amputation (Nogi et al., 2009). Knockdown (in vivo RNAi) of specific voltage-operated Ca2+ channels can differentially impact regenerative polarity outcomes (Zhang et al., 2011).

Most intriguingly, planarians exemplify a system where the conductive and instructive roles of Ca2+ signaling coalesce, as planarian polarity controlling genes reside in a subpopulation of muscle cells. Myocytes appear to act as a coordinating nexus of positional signaling, with a subepidermal set of muscle cells expressing all the relevant ‘position control genes’ known to regulate the body plan, from which positionally appropriate transcriptional responses are engaged on injury (Witchley et al., 2013). The muscle framework therefore supports a traditional myoactive conductive and contractile role, while also engaging an unexpected instructive role in polarity signaling. Such findings merit exploration of the planarian system to understand the orchestration of excitable cell Ca2+ signaling events and their downstream role in regulating stem cell behavior and regenerative fate.

To facilitate molecular studies (e.g. in vivo RNAi) and bioinformatic analyses, we report here initial efforts to define the voltage-gated ionotropic toolkit of the model planarian organism (Dugesia japonica) through transcriptomic profiling. Provision of the transcriptomic dataset detailed herein, should facilitate further adoption of this model by the broader ion channel signaling community. The utility of such a resource is exemplified here through experimental manipulation of the voltage-gated Ca2+ channel (Cav) family in this system.

2. Materials & Methods

2.1 RNAseq and de novo transcriptome assembly

Total RNA from regenerating D. japonica head fragments and whole, intact worms (biological triplicates of each sample) was extracted using Trizol reagent and mRNA purified using oligo(dT) beads (Dynal). RNA-seq libraries were prepared as described in the Illumina mRNA-Seq Sample Prep kit and Illumina TruSeq kit manufacturer protocols. Libraries were sequenced on Illumina HiSeq 2000 machines in technical duplicates (Sanger Center, Hinxton). The resulting 100bp paired end reads were processed with Trimmomatic version 0.22 (Bolger et al., 2014) to remove adapter sequences and low quality reads (sliding window quality filter, window size = 4, minimum average quality score = 25), retaining reads ≥ 50bp. In order to generate the assembly, overlapping paired-end reads were merged using FLASH (Magoc and Salzberg, 2011). The resulting reads were fed into the Trinity pipeline for de novo assembly (Hamdan and Ribeiro, 1999), carried out with a minimum k-mer coverage of 2 and default k-mer size of 25. Graphs not resolving within a 6 hour window were excised to allow the assembly to proceed and the minimum contig or transcript length was set to 100nt. In order to estimate transcript abundance, trimmed reads were aligned to the assembly using bowtie (version 2) and RSEM (version 1.2.11) to estimate FPKM values. The TransDecoder package was used to obtain the putative translated open reading frames, and these were annotated using the NCBI Conserved Domain Database.

2.2 Identification of ion channels

Sequences belonging to the voltage-gated ion channel superfamily (Yu et al., 2005) were curated by searching the translated D. japonica transcriptome against the NCBI Conserved Domain Database to identify Pfam protein family hits corresponding to domains such as ion transport (00520, 07885, 08412), Cav (08763), Nav (06512), PKD (08016), BK (03493), SK (035630) or cyclic nucleotide gated channels (08412, 00027). Sequences were filtered to verify the presence of the appropriate number of pore forming domains and expected architecture/topology for each family of ion channels. Predicted amino acid sequences were aligned using MUSCLE and cladograms generated using NINJA (Wheeler, 2009) and visualized using FigTree (version 1.4.0).

2.3 Planarian mobility assays

Dugesia japonica (GI strain) were maintained at room temperature and fed strained chicken liver puree weekly (Chan and Marchant, 2011). For photoaversion assays, planarians were placed in the middle of a petri dish (50ml) centered over a backlit light source. Animals were scored for their ability to escape into the shaded perimeter within five minutes. For generalized monitoring of worm mobility, planarians were tracked within an illuminated watchglass as previously described (Chan et al., 2016). Regenerative assays were performed using 5 day-starved worms (n>30) in pH-buffered Montjuïch salts (1.6mM NaCl, 1.0mM CaCl2, 1.0mM MgSO4, 0.1mM MgCl2, 0.1mM KCl,1.2mM NaHCO3, pH 7.4 buffered with 1.5mM HEPES) and regenerative polarity scored after 1 week. Drugs were immediately applied after cutting according to the concentrations and durations noted in figure legends and data was analysed using unpaired t-tests (significance at p<0.05).

2.4 In vivo RNAi

Knockdown was performed over several feeding/regeneration cycles (Nogi et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2011). Cav fragments were subcloned into the IPTG-inducible pDONRdT7 vector and transfected into RNaseIII deficient HT115 E. coli. A Schmidtea mediterranea gene (Smed-six-1) was used as a negative RNAi control. To assess knockdown, qPCR was performed using SYBR GreenER qPCR SuperMix Universal (Invitrogen). cDNA (not containing the RNAi targeted sequence) for each gene was cloned into pGEM-Teasy vector (Promega) and used as a template to create gene-specific standard curves in samples isolated at equivalent regenerative timepoints from different worms. Planarian β-actin was used to normalize RNA input.

2.5 In situ hybridization

Planarians were fixed in Carnoy’s solution (2hrs, ice) and processed for whole-mount hybridization performed at 55°C for 36hrs. (Nogi et al., 2009). Digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes were synthesized using in vitro RNA polymerase (Roche). Probe regions and accession numbers were: Cav1A (1027-1865bp; 2229-4133bp, HQ724315); Cav1B (2722-4010bp; 4380-6059bp, HQ724316); Cav2A (120-962bp, HQ724317); Cav2B (21-1150bp, HQ724318); Cav3 (1856-2870bp, HQ724319); PC2 (1-2285bp).

2.6 Co-immunoprecipitation Assays

Cavα residues were codon optimized for mammalian expression. The domain I/II linker (containing the Cavα/β interaction site) was PCR amplified (Cav1B, residues 558–684 from HQ724316.1) and affinity tags incorporated (myc:Cav1B; 6xHis:Cavβ1). The mutated Cav1B[W593A]AID sequence was also generated by PCR. Transiently transfected HEK293 cells (T75 flask) were harvested and resuspended in 750µL of IP buffer (PBS, supplemented with 1% TritonX-100 and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail; Roche). Cells were sonicated (3×10s on ice) and centrifuged (16,000g, 15min, 4°C) prior to harvesting supernatant. For pre-clearing, Protein G beads (20µL of a 50% slurry in IP buffer; Roche) were added and the mixture incubated on a shaker (20mins, 4°C). After centrifugation (13,000g, 5mins, 4°C), the supernatant was carefully collected. For each reaction (~250µg protein in 500µl), samples were incubated with antibody (1µg; rabbit/anti-myc, Sigma) on a rotator (1hr, 4°C) and protein G beads (15µl of a 50% slurry, IP buffer) added prior to overnight incubation (4°C). Immunoprecipitates were separated (13,000g, 1min) from the supernatant. Beads were washed and resuspended three times (500µl IP buffer, 10mins shaking at 4°C) before gel loading. Western blotting was performed after separation and transfer (4–20% Mini-PROTEAN® TGX Gel, BioRad; PVDF membrane) using mouse/anti-His or mouse/anti-myc 1° antibodies and goat/anti-mouse Alexa Fluor®680 2° antibodies (Invitrogen).

3. Results

3.1 De novo transcriptome assembly

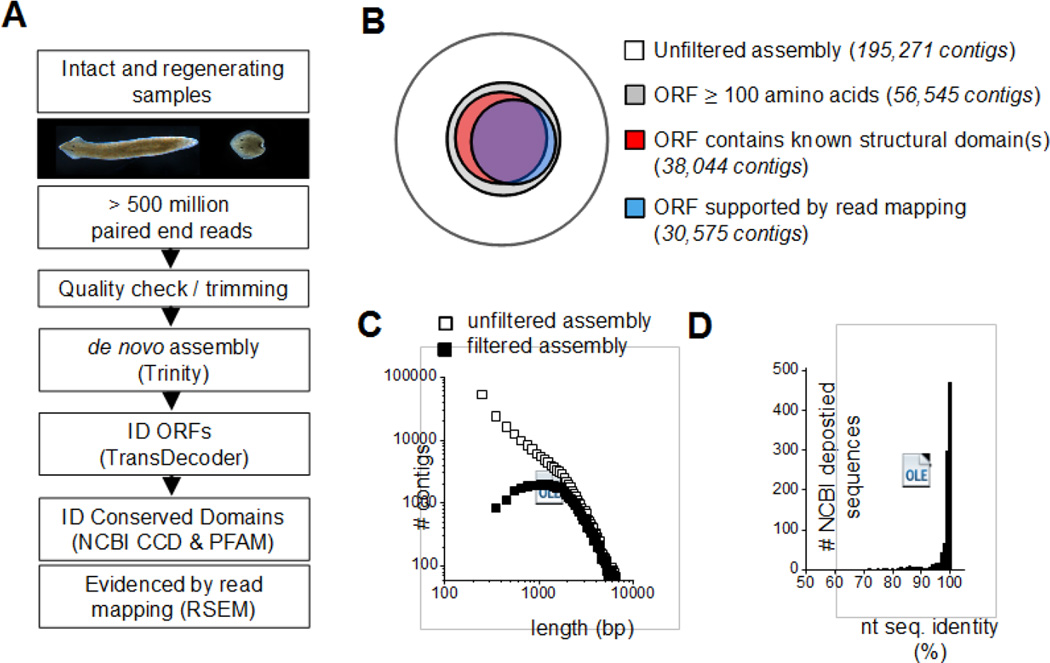

In order to generate a Dugesia japonica transcriptome representing a diverse range of expressed gene products, mRNA from intact and regenerating planarian samples was sequenced at high read depth and assembled according to the workflow outlined in Figure 1A. The initial de novo assembly of RNAseq data using Trinity yielded a dataset with 195,271 sequences and an N50 of 1,587bp (white circle, Figure 1B). This number of contigs is an order of magnitude greater than the number of predicted gene models in published planarian genomes (Dugesia japonica, ~28,000, (Nishimura et al., 2015); S. mediterranea, ~30,000, (Robb et al., 2008; Robb et al., 2015)), likely due to a high number of redundant or incorrectly/partially assembled transcripts. Therefore, the preliminary assembly was filtered to retain only (i) sequences with predicted open reading frames (ORFs) ≥ 100 amino acids that contain an assignment to a known PFAM structural domain, or (ii) sequences with predicted open reading frames (ORFs) ≥ 100 amino acids that were evidenced by read mapping (Figure 1B). The resulting filtered assembly retained 44,857 sequences with an N50 of 2,444bp (Figure 1C). These statistics are consistent with de novo assemblies of other planarian species (Girardia tigrina, Dendrocoelum lacteum, Schmidtea mediterranea; Table 1). A high level of coverage in this assembly is evidenced by the fact that, of 983 manually cloned D. japonica nucleotide sequences deposited on NCBI, 982 are represented with a high degree of sequence identity (Figure 1D). Sequences from the unfiltered assembly (white circle, Figure 1B) are provided as a Supplementary data file (Supplementary Dataset 1). The filtered ORF assembly of 44,857 sequences (blue and red circles, Figure 1B) is also provided (Supplementary Dataset 2). These files provide nucleotide sequence for all gene products referenced in this work, and should enable identification of sequences of interest for other research projects.

Figure 1. Generation of a D. japonica transcriptome by de novo assembly.

(A) Workflow for de novo assembly of the D. japonica transcriptome, from sample isolation and sequencing to read mapping against the assembly. (B) Overview of sequence numbers within unfiltered assembly (white) and assembly subject to indicated filters (colors). Both the unfiltered assembly and assembly filtered by structural domain prediction (red) and read mapping (blue) are provided as supplementary datasets. (C) Comparison of length distribution for contigs in the unfiltered and filtered assemblies. (D) Coverage of the D. japonica transcriptome assessed by BLAST of 983 manually cloned sequences deposited NCBI (NCBI tax. ID 6161).

Table 1. Summary of D. japonica transcriptome metrics.

Descriptive statistics for the transcriptome of D. japonica (black) relative to assemblies reported for three other planarian species (G. tigrina, D. lacteum, S. mediterrenea).

| D. japonica | G. tigrina | D. lacteum | S. mediterrenea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N50 | 2444 | 1293 | 1699 | 1981 |

| Min length | 297 | 51 | 201 | 201 |

| Max length | 17617 | 16092 | 29521 | 19524 |

| Mean length | 1989.7 | 910.1 | 1096.8 | 1340.6 |

| # of contigs | 44857 | 33643 | 79575 | 38633 |

| GC content | 30.54% | 35.8% | 36.5% | 34.4% |

| Reference | (Kao et al., 2013) | (Liu et al., 2013) | (Liu et al., 2013) |

3.2 Analysis of the ionotropic channel portfolio

Dissecting the planarian ionotropic toolkit is of interest given the known role of voltage-dependent signaling in neurogenic events (Deisseroth et al., 2004; Spitzer, 2006), as well as the importance of this model for studying CNS regeneration given the phylogenetic position of planaria (Sarnat and Netsky, 2002; Cebrià, 2007; Sandmann et al., 2011). Also significant is the clinical relevance of flatworm ion channels as targets for drug discovery as the druggability of flatworm neuromusculature is an effective strategy for impairing parasite viability (Wolstenholme, 2011; Greenberg, 2014), including clinically important human diseases (Schistosoma spp; Chan 2013, Chan 2015).

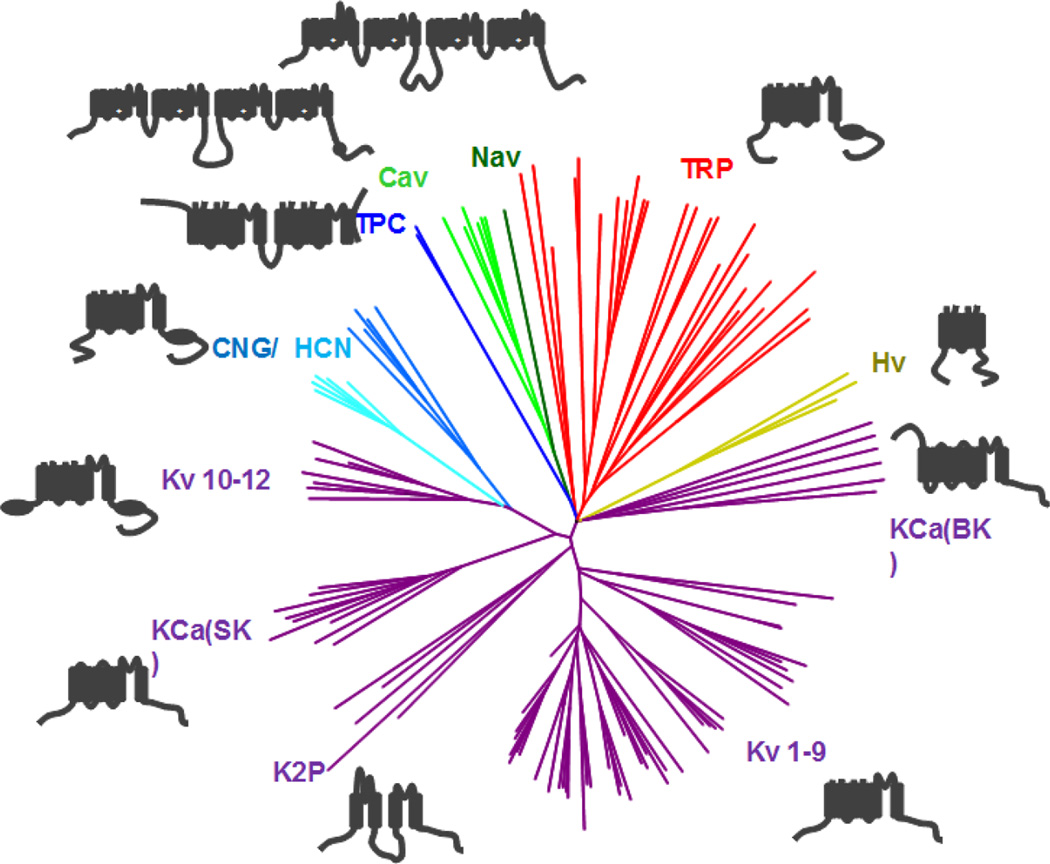

Therefore, we set about mining the D. japonica assembly for members of the voltage-gated-like (VGL) ion channel superfamily (Yu et al., 2005). Translated D. japonica ORFs were searched against the PFAM database and all sequences containing hits to domains characteristic of VGL members were curated (identified contigs with domain accession numbers are provided in Supplementary Table 2). Candidates were manually inspected for (1) architecture: presence of the expected number of transmembrane domains (i.e. four contiguous domains for voltage operated Ca2+ (Cav) channels, two contiguous domains for two pore channels (TPCs)), (2) known structural domains: (features such as ion transport, PKD and IQ domains) and (3) conservation of ion selectivity motifs (e.g. E/E/E/E sequence for HVA Cavs or E/E/D/D sequence for LVA Cavs). This analysis which resulted in the prediction of 114 discrete pore-containing channel sequences that could be assigned to VGL ion channel families, clustered through homology as shown in the cladogram represented in Figure 2. This approach was intentionally conservative, selecting for complete conservation of channel architecture/motifs with mammalian counterparts and notwithstanding any variation in structural and functional motifs of flatworm ion channels, as well as excluding the numerous partial sequences assignment which would require additional verification. Accessory ion channel subunits (non-pore forming) are not included in this analysis, nor are other ion permeation pathways outside the core VGL ion channel superfamily (Yu et al., 2005).

Figure 2. The ionotropic portfolio of D. japonica.

Cladogram representing the D. japonica voltage-gated-like (VGL) ion channel superfamily sequences. Predicted amino acid sequences from contigs (Supplementary Table 2) were aligned using MUSCLE and degapped using GapStreeze (50%). Cladogram was generated using NINJA (Wheeler, 2009) and visualized using FigTree (version 1.4.0). Schematic of channel transmembrane helix organization is shown adjacent to clades colored as follows: four transmembrane domain channels (Cav, Nav; green), two-pore channels (TPCs, navy), cyclic-nucleotide gated channels (CNG/HCN, light blue), K+ channels (purple), proton channels (Hv, yellow), transient receptor potential channels (TRP, red).

The number of planarian VGL sequences (114) is lower than the number of genes in the human voltage-gated ion channel gene set (130 pore forming subunits [voltage-gated ion channel set 178 from the HUGO Gene nomenclature committee]). Only two channel clades were absent in planarians compared with the human VGL superfamily. First, there was no evidence for Pfam domains PF01007, PF08466 (inward rectifying K+ channels, Kir) in this assembly, or among S. mediterranea or S. mansoni gene models. Possibly the physiological role of Kir is assumed by other types of K+ channels in flatworms (Klassen et al., 2006). Second, as expected, no CatSper channels were found in these non-sexualized planaria. The number of planarian sequences is however higher than the number of VGL genes identified in C. elegans (~104 genes, (Hobert, 2013)): likely an accurate prediction of increased planarian VGL diversity as several channel classes present in D. japonica are absent in C. elegans (Nav channels, HCN channels, TPCs) and other groupings contain a greater number of representatives. Supplementary Table 2 details the contig identifier and assignment of each of the D. japonica sequences based upon our assembly and current filtering methods. Within each class, assignments are ordered by FPKM values (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads) to convey which transcripts predominate within each class of channels. Obviously, verification of each of these assignments will require further biological interrogation, but this resource provides opportunity to address the roles of individual channels in planarian physiology and regenerative events such as wound healing and subsequent instructive signaling. We exemplify this by exploring the role of the entire family of planarian Cavs, as discussed below.

3.3 Properties of planarian voltage operated Ca2+ channels

Ca2+ signaling processes are integral to flatworm neuromuscular physiology, supporting neuronal coordination of muscular tone as well as the muscle contractile cycle itself (Cobbett and Day, 2003; Novozhilova et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2013). Therefore, the discovery that planarian muscle cells express a suite of ‘position control genes’ (Witchley et al., 2013) refocuses interest on observations that Ca2+ signaling events and voltage-operated Ca2+ (Cav) channels impact AP patterning (Nogi et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2011).

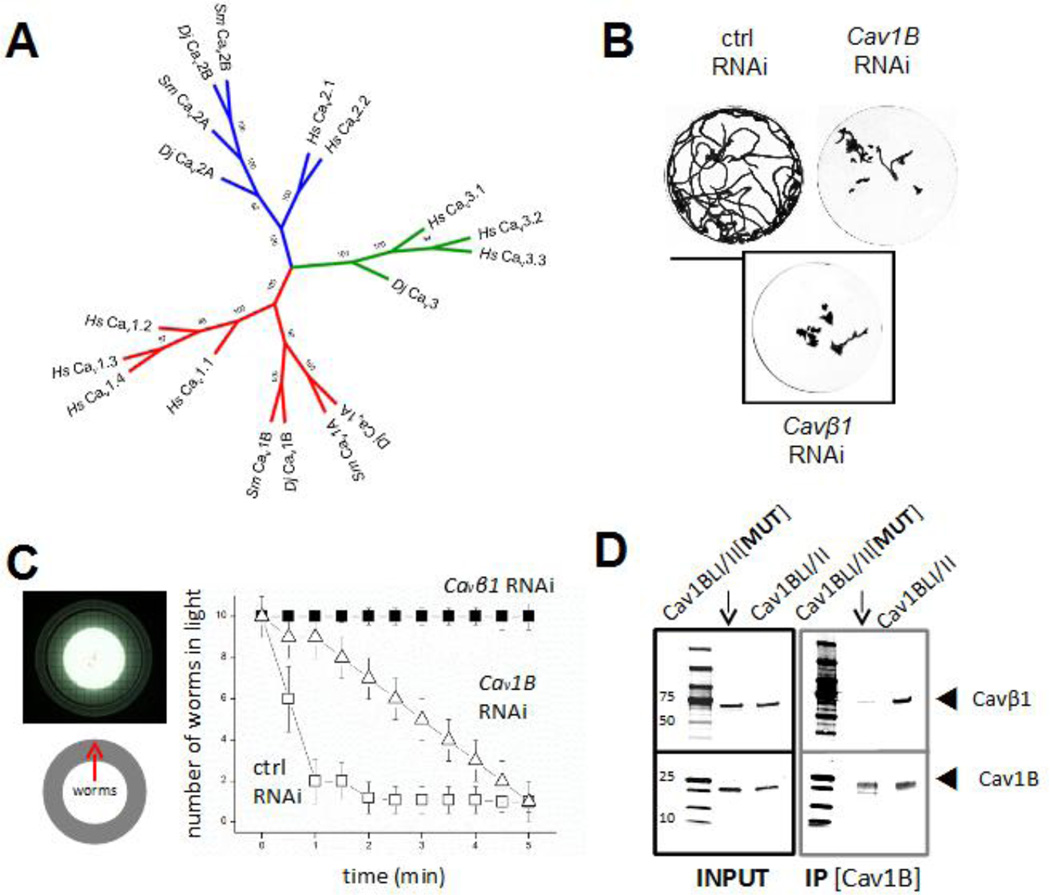

Analysis of the D. japonica transcriptome assembly confirmed the existence of five discrete voltage-operated Ca2+ channel α subunits, previously identified by degenerate PCR (Zhang et al., 2011). Full length sequences had previously been obtained for only two of these isoforms (Cav1A and Cav1B, (Zhang et al., 2011)), and the availability of the new assembly was used to generate an updated phylogeny (Figure 3A). Four of these sequences comprise high-voltage activated (HVA; Cav1A&B, Cav2A&B) subunits, with the fifth sequence identified as a low voltage activated isoform (LVA, Cav3), a more diverse portfolio that other invertebrate models (three Cavs in C. elegans and Drosophila, (Chan et al., 2013)). Comparison of FPKM values for each Cav evidences a reasonable equivalency in expression across the five isoforms, with no single channel predominating (Supplementary Table 2). The availability of the transcriptomic sequence information enabled RNAi analyses of each of Cav channels. RNAi experiments of all five Cav channels were performed in parallel to assess phenotypes in both intact and regenerating worms.

Figure 3. Knockdown of planarian Cav1B inhibits worm mobility.

(A) Unrooted neighbor joining tree of Cavα sequence identity in human (Hs), the parasitic flatworm Schistosoma mansoni (Sm) and the planarian Dugesia japonica (Dj). Relationships are represented by a neighbor joining method (100 bootstrap replicas) inferred from multiple sequence alignment using MUSCLE. Confidence values are indicated at major nodes. High- (blue, red) and low-voltage (green) activated Cav channels are indicated. (B) RNAi of either a Cavα subunit (Cav1B RNAi, top right) or a Cavβ subunit (Cavβ1 RNAi, bottom) impairs planarian mobility. Images show minimal intensity overlay from a 2 minute recording of respective RNAi cohorts (10 worms) within a watchglass to enable easy visual comparison of worm movements. Scale bar, 25mm. (C) Photoaversion data. Left, Schematic of photoaversion assay to assess worm motility. Worms are centered on an illuminated surface and number of worms escaping to the dark periphery of the petri dish is quantified over time. Graph depicts effects of either Cav1B or Cavβ1 RNAi on worm motility, measured by counting the number of worms (from a total of 10) remaining within the central, illuminated portion of petri dish. (D) Co-immunoprecipitation reveals Cav1B (residues 558–684, IP anti-myc) interacts with Cavβ1 (anti-His).

In intact worms, the most obvious RNAi phenotype was observed on knockdown of the Cav1B channel: Cav1B RNAi worms displayed a clear mobility defect (Figure 3B). This defect could easily be observed by compiling minimal intensity projections of worm motility within an illuminated watch glass over a fixed period of recording time. These projections demonstrated a restricted range of motion of Cav1B RNAi worms compared to RNAi controls (Figure 3B). Quantification of this defect was made in a separate assay by analyzing the planarian photoaversion response, exploiting the preference of worms to mobilize quickly away from bright light. Here, ten worms were placed in the center of a recording chamber and the number of worms remaining within the illuminated center, as opposed to the shaded periphery, was made over time (Figure 3C). Figure 3C displays results from experiments comparing control RNAi worms (which quickly escape away from the illuminated center) with Cav1B RNAi worms, to assess any defect in mobility. In these assays, Cav1B RNAi worms displayed impaired mobility (Figure 3C). This mobility defect was reminiscent to the mobility defect previously seen in cohorts of planaria subject to knockdown of the voltage-operated Ca2+ channel accessory subunit, Cavβ1 (Nogi et al., 2009). Given RNAi of both Cavβ1/Cav1B precipitated similar mobility defects (Figure 3B&C), we reasoned these subunits may interact. To assess interactivity we performed co-immunoprecipitation assays in vitro using His-Cavβ1 and a region of Cav1B spanning the domain I-domain II linker (myc-Cav1BLI/II), which contains the alpha interaction domain for the Cavβ subunit. As a negative control, a mutated myc-Cav1BLI/II[MUT] construct was used which harbored a single amino acid change (W593A) known to decrease subunit interaction affinity. Co-immunoprecipitation assays demonstrated an interaction between His-Cavβ1 and myc-Cav1BLI/II, which was attenuated with myc-Cav1BLI/II[MUT] (Figure 3D). No pulldown was observed when a similar region of the planarian Cav3 channel was used, which is expected to display low affinity for Cavβ (data not shown). These data suggest Cav1B interacts with Cavβ1 in the same Cav complex in vivo and a support the observed similar RNAi movement phenotypes after targeting these subunits in vivo.

RNAi analyses of each of the Cav channels in regenerating worms were also performed. Here, we had previously shown that the two Cav1 isoforms (Cav1A, Cav1B) exerted opposing effects on a drug-evoked anteriorization stimulus. Specifically we examined incubation with praziquantel (PZQ) which evoked a robust bipolar (two-headed) phenotype during regeneration of D. japonica trunk fragments (Nogi et al., 2009). Knockdown of Cav1A attenuated the ability of PZQ to evoke bipolarity, whereas knockdown of Cav1B yielded the opposite effect, potentiating the generation of two-headed worms (Zhang et al., 2011). However, the uniqueness of these effects within the broader complement of the five planarian Cav channels remains unknown.

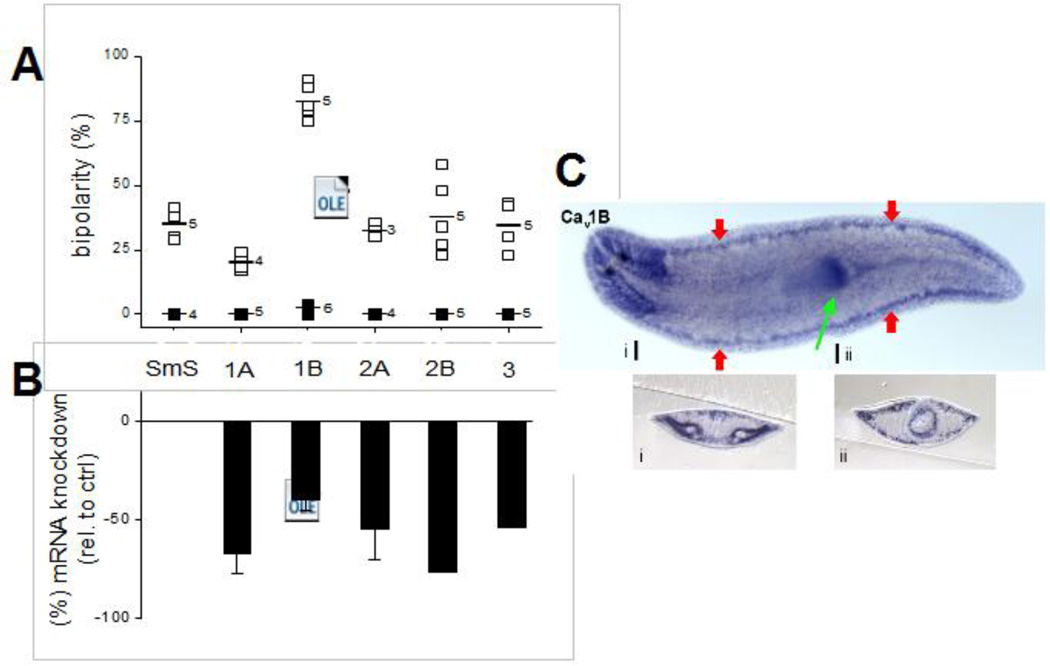

Analysis of RNAi data targeting each of the five Cav channels demonstrated that only the Cav1 channels modulated PZQ-evoked bipolarity: Cav1B RNAi uniquely potentiated the number of two-headed regenerants evoked by a submaximal PZQ concentration (35±2% to 83±3%, Figure 4A). In contrast, in vivo RNAi of Cav2A, Cav2B or Cav3 failed to modulate PZQ efficacy at causing bipolarity (Figure 4A), or intact worm mobility (data not shown). The number of two-headed worms was similar between control (35±2%) and these RNAi cohorts (33±2% for Cav2A RNAi, 38±7% for Cav2B RNAi, 35±5% for Cav3 RNAi; Figure 4A). This lack of effect was not due to inefficient RNAi as qPCR analysis confirmed decreased mRNA levels for these three channels (50–80%, Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Regenerative effects and distribution of Cav1B.

(A) Effect of Cavα subunit RNAi on two-headed regeneration in the presence (open) or absence (solid) of PZQ (70µM, 24hrs). Number of independent trials are indicated. Solid line represents mean value of control RNAi cohort. (B) qPCR assessment of Cavα knockdown relative to RNAi control. (C) Whole mount in situ hybridization of Cav1B mRNA distribution to highlight expression in CNS, pharyngeal muscle (green arrow) and subepidermal tissue (red arrow). Sections at the (i) brain and (ii) pharynx are shown.

On account of the Cav1B RNAi phenotypes, we examined the distribution of Cav1B by in situ hybridization. These experiments indicate Cav1B is expressed in the nervous system (shown by staining of cephalic ganglia and ventral nerve cords) and muscle (most obviously in the pharynx, Figure 4C). Closer inspection also revealed subepidermal expression (Figure 4C), similar to reported subepidermal staining patterns of muscle containing known planarian polarity genes (Witchley et al., 2013). Other Cav mRNAs also resided in excitable tissue (Supplementary Figure 1), but none of these staining patterns revealed as prominent subepidermal staining as evident with Cav1B.

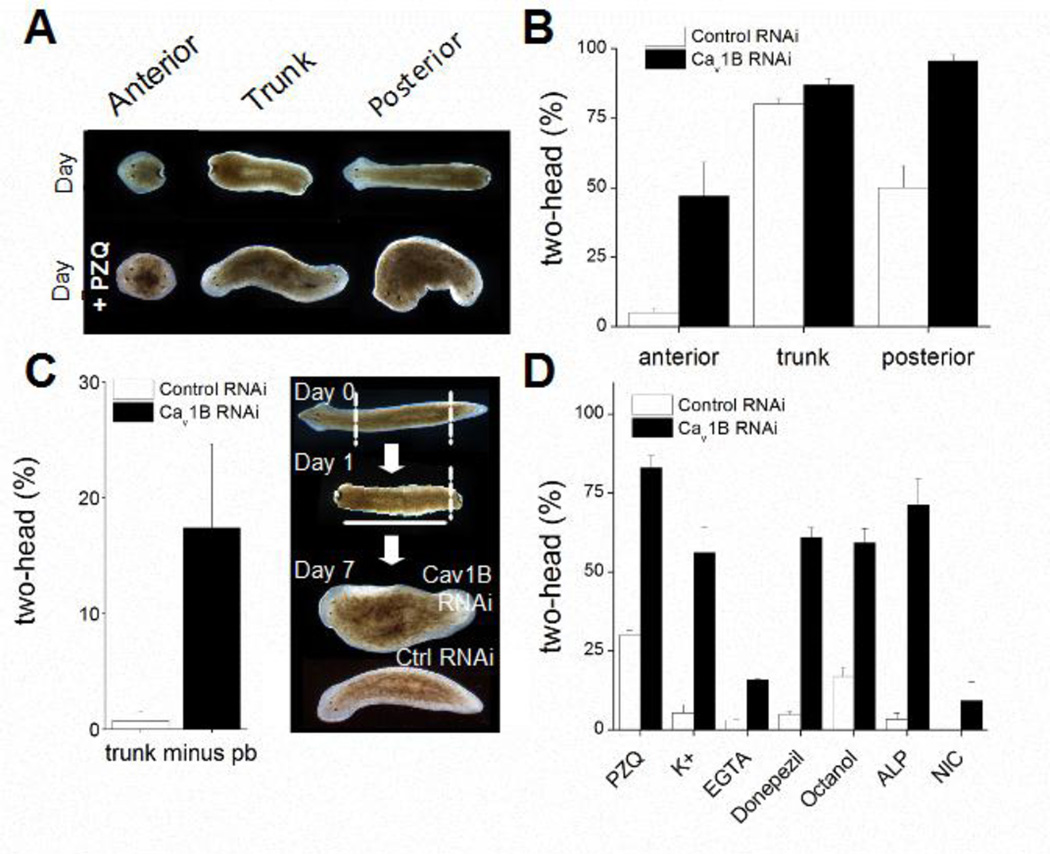

3.4 Cav1B RNAi creates a permissive environment for anteriorization

To assess the scope over which Cav1B impacted polarity signaling, we investigated the effects of Cav1B RNAi in different types of amputated fragments and in responses to other drugs. First, single-cut fragments were isolated with amputations behind the head (‘anterior’ cut fragment) or tailwards (‘posterior’ cut fragment, Figure 5A). Consistent with the long characterized inhibitory influence of the planarian brain on ectopic head regeneration (Marsh and Beams, 1952; Lange and Steele, 1978; Cebria et al., 2002; Yazawa et al., 2009; Oviedo et al., 2010), PZQ exposure yielded a higher proportion of two-headed worms from single-cut ‘posterior’ fragments (50±8% bipolar, n=3; Figure 5B) compared with ‘anterior’ fragments (6±1% bipolar, n=3), where the original brain tissue remained closely juxtaposed. In Cav1B RNAi worms treated with PZQ, the numbers of two-headed worms regenerating from all fragments was higher than control RNAi worms. For posterior fragments, the proportion of two-headed regenerants was ~2-fold greater than controls, while for anterior fragments the potentiation was ~9-fold (owing to lower levels of drug-induced bipolarity in controls, Figure 5B). Although little potentiation was observed from trunk fragments under optimal conditions, potentiation of bipolarity by Cav1B RNAi was clearly observed when the PZQ concentration was lowered (Figure 4A).

Figure 5. Cav1B RNAi anteriorizes regenerative outcomes.

(A) Top, representative images showing different amputations and bottom, resultant bipolar phenotypes following PZQ exposure (75µM, 48hrs) scored 7 days after cutting. (B) Number of two-headed worms after PZQ treatment in control RNAi (open) and Cav1B RNAi fragments (solid). (C) Cav1B RNAi increased the frequency of bipolar worms in the absence of drug. Left, The small proportion of two-headed worms regenerating from trunk fragments after amputation of the posterior blastema (after 24hrs) was potentiated in a Cav1B RNAi background. Right, amputations (dashed) performed in these assays. (D) Cav1B RNAi increased bipolar regeneration from trunk fragments in response to multiple pharmacological agents. Conditions: PZQ (50µM, 24hrs), K+ (30mM, 24hrs), EGTA (1mM, 24hrs), donepezil (10µM, 24hrs), octanol (125µM, 72hrs), alsterpaullone (5µM, 24hrs), nicotine (100µM, 48hrs).

Does Cav1B RNAi anteriorize regeneration in the absence of drug? First, Cav1B RNAi resulted in a tiny percentage of two-headed worms regenerating from trunk fragments without drug exposure (Figure 4A). Second, although the polarity determining mechanisms during regeneration are robust, certain amputations elicit bipolarity at extremely low penetrance. For example, removing the posterior blastema of regenerating trunk fragments after 24 hours can miscue the regenerative polarity of the residual trunk fragment. In our hands this protocol generated the occasional two-headed animal (~1%; Figure 5C). However, the same manipulation in Cav1B RNAi worms resulted in higher bipolarity (17±5%, n=3; Figure 5C).

Does Cav1B RNAi increase the effectiveness of other drugs that anteriorize regeneration? We investigated the polarity miscuing effects of several compounds reported in the literature (Nogi and Levin, 2005; Nogi et al., 2009; Oviedo et al., 2010), each of which yielded some proportion of two-headed worms in regenerative assays (Figure 5D). In a Cav1B RNAi background, all these compounds evoked higher levels of bipolarity (Figure 5D) and bipolar regeneration was seen even for compounds (e.g. nicotine) that failed to cause bipolarity in control RNAi (or naïve) backgrounds (Figure 5D).

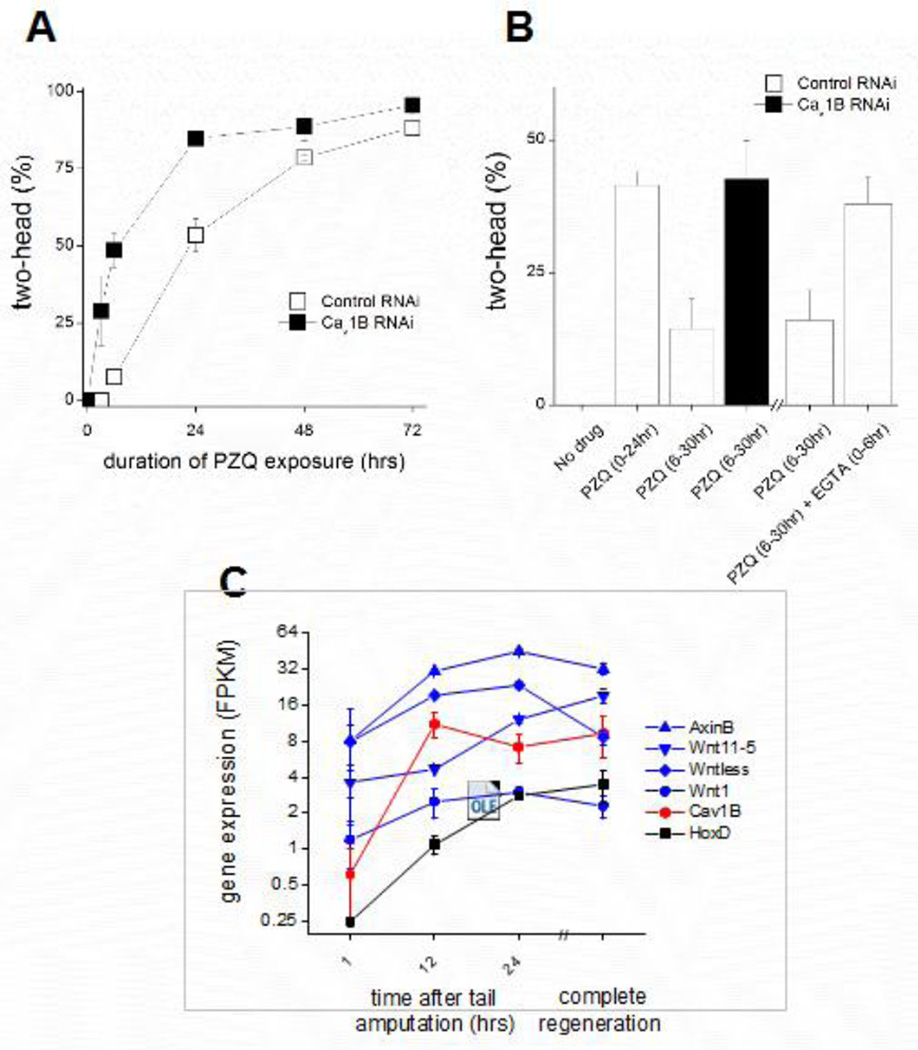

3.5 Cav1B mediated Ca2+ influx at early regenerative timepoints

When does Cav1B act to impact polarity outcomes during regeneration? While planarians take a week or more to fully regenerate missing structures, the signaling pathways that determine regenerative outcomes are rapidly cued after injury: positional control genes are upregulated within hours after injury (median time of ~4 hours, (Wurtzel et al., 2015)). Exposure to the anteriorizing compound PZQ resulted in an increased number of two-headed worms in Cav1B RNAi compared with control RNAi cohorts (Figure 6A). This effect was seen over all durations of PZQ exposure, including the early 3–6 hour time window during which positional control genes are engaged. Therefore knockdown of Cav1B impairs the normal “tail” determining events occurring at the earliest regenerative timepoints (Figure 6A). Furthermore, drugs such as PZQ are only efficacious at miscuing polarity if administered immediately after amputation (Nogi et al., 2009; Oviedo et al., 2010), becoming less effective if exposure is delayed as determination events occur. For example, in control RNAi worms, PZQ shows reduced penetrance if treatment is delayed until 6 hours after injury (Figure 6B). However, Cav1B RNAi worms anteriorize to a delayed stimulus with similar efficacy as worms treated with drug immediately following amputation (Figure 6B). This early “tail” determining window is Ca2+ dependent as it is impaired by Ca2+ chelation (EGTA 1mM) at early timepoints, as demonstrated by a retained effectiveness of a delayed PZQ exposure after EGTA treatment. (Figure 6B). Therefore, inhibition of Ca2+ influx genetically (Cav1B RNAi) or pharmacologically (by Ca2+ chelation at early regenerative timepoints) impaired posterior determination as evidenced by the preserved ability of PZQ to anteriorize regeneration at timepoints when normally inefficacious. These data suggest Cav1B mediated Ca2+ influx acts as an early, posterior-determining cue.

Figure 6. Cav1B rapidly impacts posterior determination after wounding.

(A) Cav1B regulates posteriorization at early time points after amputation. Cav1B RNAi increased bipolarity over any PZQ (90µM) incubation period. (B) Delayed exposure to anteriorizing compound (PZQ) decreased the number of two-headed regenerants. This effect was blunted by either Cav1B RNAi or incubation in Ca2+-free media (EGTA: 1mM, 6hrs) immediately after amputation and prior to PZQ addition (PZQ: 6–30hrs versus 0–24hrs). (C) Expression of anterior-posterior patterning genes in head fragments collected at various time points following tail amputation (1, 12, 24hrs) and completely regenerated, intact worms (>1 week). Positional control genes mediating Wnt signaling (Wntless, Wnt1, AxinB, Wnt11-5; blue), posterior “tail” marker (HoxD; black) and Cav1B (red). FPKM values reflect average ± S.E.M. for three biological replicates at each time point.

Analysis of transcriptomic data also demonstrates a rapid change in Cav1B transcripts after injury coinciding with the upregulated expression of known posterior “positional control genes” (Petersen and Reddien, 2009; Wenemoser et al., 2012; Witchley et al., 2013). Analysis of RNAseq data isolated from regenerating D. japonica samples at varying time-points (1, 12 and 24 hours, n=3) following “tail” amputation revealed a dynamic increase in Cav1B within 12 hours after injury (>17 fold increase between 1hr and 12hr post amputation timepoints, Figure 6C). This window coincides with increased expression of genes involved in canonical Wnt signaling that rapidly express to reset “tail” positional identity at posterior wounds (Adell et al., 2009; Petersen and Reddien, 2009; Iglesias et al., 2011), and is temporally consistent with prior data that Cav1B activity regulates posteriorization through neuronal Hedgehog/Wnt signaling (Yazawa et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2011).

4. Discussion

The robust regenerative and rejuvenative capacity of planarian flatworms has enthralled generations of scientists. Ongoing optimization of tools and technologies in this system has catalyzed an increasing adoption of planarians as a model for dissecting the molecular choreography of tissue regeneration, and for studying fundamental aspects of flatworm biology (Newmark and Sánchez-Alvarado, 2002; Rink, 2013). Such investigations have impact beyond ‘basic’ science: planarian research potentially illuminates vulnerabilities of parasitic flatworms which cause significant disease burden worldwide (Nogi et al., 2009; Collins and Newmark, 2013; Chan et al., 2014; Chan et al., 2015). Further, the majority of genes causing planarian RNAi phenotypes display significant homology to genes in other metazoan genomes: indeed, one of the earliest planarian RNAi studies established than dozens of genes displaying RNAi phenotypes correlate with known human disease genes (Reddien et al., 2005). Such work has established the broader utility of the planarian model system beyond the obvious relevance of this system for understanding stem cell engagement, coordination and correct lineage and positional differentiation after injury.

While certain methodological roadblocks (notably transgenesis) in the planarian system remain, our understanding of regenerative signaling and the scope of experimental capabilities within this model have been transformed over the last two decades. One example of this progress has been the accumulation of bioinformatic data deriving from planarian genome studies (best exemplified in Schmidtea mediterranea, (Robb et al., 2008; Robb et al., 2015) and the proliferation of transcriptomic datasets. Dugesia japonica, the planarian species studied here, is finding particular utility owing to its drug responsiveness. Several Dugesia japonica transcriptomic datasets have recently been reported (Qin et al., 2011; Abnave et al., 2014; Nishimura et al., 2015; Pang et al., 2016; Shibata et al., 2016), although provision of assembled sequences as publically accessible, interrogable resources has in some cases lagged their formal description. This serves as a barrier for encouraging adoption of this system by non-planarian laboratories. Analysis of the D. japonica transcriptome (Supplementary Dataset 1) reveals an organism endowed with a diverse voltage-gated ionotropic toolkit (Figure 2), and scrutiny of this resource will enable further investigations of the role of ion channels, and Ca2+ signaling in planarian regenerative physiology.

In terms of the Ca2+ signaling toolkit planarians express numerous Ca2+ entry pathways, intracellular Ca2+ release channels, and a variety of Ca2+ pumps/exchangers. In this study, we started an exploration of these pathways by using the transcriptomic resource to interrogate the role of the planarian Cav family. Knockdown of a specific Cav (Cav1B) inhibited planarian mobility (Figure 3) and uniquely potentiated drug-evoked anteriorization (Figure 4A), providing support to the surprising correlation between muscle function and instructive signaling during regeneration (Witchley et al., 2013). Indeed, Cav1B RNAi created a permissive environment for anteriorization across a variety of regenerative paradigms (Figure 5), a potentially useful manipulation as a genetic background for enhancer screening. The mechanistic basis of how Cav1B impacts muscle physiology nevertheless remains to be established. Cav1B mediated Ca2+ influx could impact muscle function by altering neurotransmission, or by directly impacting muscle Ca2+ signaling – mRNA localization data suggests expression in both excitable cell types (Figure 4C, (Wurtzel et al., 2015)). Numerous studies evidence that dysregulation of the excitable cell niche by perturbation of CNS or muscle biology can impact regenerative polarity signaling (Yazawa et al., 2009; Oviedo et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2011; Cowles et al., 2013; Cowles et al., 2014; Durant et al., 2016; Lei et al., 2016), and it seems reasonable to speculate that a broad range of pharmacological agents that miscue regenerative polarity share the capacity to target the excitable cell niche and dysregulate muscle function (Chan et al., 2015). This would provide an unexpected commonality amongst a lengthy historical pharmacopeia of exogenous agents that impact regeneration (Rustia, 1925; Teshirogi, 1955; Kanatani, 1958; Flickinger, 1959; Rodriguez and Flickinger, 1971; Nogi and Levin, 2005; Nogi et al., 2009; Salvetti et al., 2009; Oviedo et al., 2010; Beane et al., 2011) and prioritize further investigation of excitable cell physiology, voltage-operated ion channels and Ca2+ signals in the control of regenerative outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Table 2. Number of sequences within discrete voltage-gated-like ion channel families predicted by the D. japonica transcriptome.

Ion channels are defined by transmembrane helix organization and conserved structural domains elaborated in Supplementary Table 2. Assignment conservatively reflects the D. japonica VGL ionotropic repertoire, as partially assembled sequences are omitted.

| Ion channel | Number of sequences |

|---|---|

| Voltage gated Ca2+ channels (Cav) − HVA + LVA | 4 + 1 |

| Voltage gated Na+ channels (Nav) | 1 |

| Cyclic nucleotide gated channels (CNGC) | 5 |

| Hyperpolarization activated CNGCs (HCN) | 5 |

| Two pore channels (TPC) | 2 |

| Voltage gated K+ channels (Kv) | 43 |

| Two pore K+ channels (K2P) | 10 |

| Ca2+ activated K+ channels (KCa) | 15 |

| Voltage gated proton channels (Hv) | 3 |

| Transient receptor potential cation channels (TRP) | 25 |

Highlights.

Broad portfolio of voltage-gated ion channels within a planarian transcriptome

This resource facilitates future study of the role of individual planarian ion channels

A specific voltage gated Ca2+ channel regulates posteriorization events after injury

Acknowledgments

Supported by the NSF (MCB1615538, JSM) and a Stem Cell Biology Training Grant (T32 GM113846, JDC). We thank the Parasite Genomics Group at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute for their assistance with sequencing samples.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abnave P, Mottola G, Gimenez G, Boucherit N, Trouplin V, Torre C, Conti F, Ben Amara A, Lepolard C, Djian B, et al. Screening in planarians identifies MORN2 as a key component in LC3-associated phagocytosis and resistance to bacterial infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16(3):338–350. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adell T, Salo E, Boutros M, Bartscherer K. Smed-Evi/Wntless is required for βcatenin-dependent and -independent processes during planarian regeneration. Development. 2009;136:905–910. doi: 10.1242/dev.033761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beane WS, Morokuma J, Adams DS, Levin M. A chemical genetics approach reveals H,K-ATPase-mediated membrane voltage is required for planarian head regeneration. Chemistry and Biology. 2011;18(1):77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulware MJ, Marchant JS. Timing in cellular Ca2+ signalling. Current Biology. 2008;18(17):R769–R776. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cebrià F. Regenerating the central nervous system: how easy for planarians! Development Genes and Evolution. 2007;217:733–748. doi: 10.1007/s00427-007-0188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cebria F, Kobayashi C, Umesono Y, Nakazawa M, Mineta K, Ikeo K, Gojobori T, Itoh M, Taira M, Sanchez Alvarado A, et al. FGFR-related gene nou-darake restricts brain tissues to the head region of planarians. Nature. 2002;419:620–624. doi: 10.1038/nature01042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JD, Agbedanu PN, Grab T, Zamanian M, Dosa PI, Day TA, Marchant JS. Ergot Alkaloids (Re)generate New Leads as Antiparasitics. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2015;9(9):e0004063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JD, Grab T, Marchant JS. Kinetic profiling an abundantly expressed planarian serotonergic GPCR identifies bromocriptine as a perdurant antagonist. International Journal for Parasitology: Drugs and Drug Resistance. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JD, Marchant JS. Pharmacological and functional genetic assays to manipulate regeneration of the planarian Dugesia japonica. J Vis Exp. 2011;(54) doi: 10.3791/3058. pii: 3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JD, Agbedanu PN, Zamanian M, Gruba SM, Haynes CL, Day TA, Marchant JS. Death and axes'; unexpected Ca2+ entry phenologs predict new antischistosomal agents. PLoS Pathogens. 2014;10(2):e1003942. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JD, Zarowiecki M, Marchant JS. Ca2+ channels and Praziquantel: a view from the free world. Parasitology International. 2013;62(6):619–628. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobbett P, Day TA. Functional voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in muscle fibers of the platyhelminth Dugesia tigrina. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 2003;(134):593–605. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(02)00350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JJ, 3rd, Newmark PA. It's no fluke: the planarian as a model for understanding schistosomes. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(7):e1003396. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowles MW, Brown DD, Nisperos SV, Stanley BN, Pearson BJ, Zayas RM. Genome-wide analysis of the bHLH gene family in planarians identifies factors required for adult neurogenesis and neuronal regeneration. Development. 2013;140(23):4691–4702. doi: 10.1242/dev.098616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowles MW, Omuro KC, Stanley BN, Quintanilla CG, Zayas RM. COE loss-of-function analysis reveals a genetic program underlying maintenance and regeneration of the nervous system in planarians. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(10):e1004746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deisseroth K, Singla S, Toda H, Monje M, Palmer TD, Malenka RC. Excitation-neurogenesis coupling in adult neural stem/progenitor cells. Neuron. 2004;42:535–552. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delling M, Indzhykulian AA, Liu X, Li Y, Xie T, Corey DP, Clapham DE. Primary cilia are not calcium-responsive mechanosensors. Nature. 2016;531(7596):656–660. doi: 10.1038/nature17426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H, Gerencser AA, Jasper H. Signal integration by Ca(2+) regulates intestinal stem-cell activity. Nature. 2015;528(7581):212–217. doi: 10.1038/nature16170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant F, Lobo D, Hammelman J, Levin M. Physiological controls of large-scale patterning in planarian regeneration: a molecular and computational perspective on growth and form. Regeneration (Oxf) 2016;3(2):78–102. doi: 10.1002/reg2.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot SA, Sanchez Alvarado A. The history and enduring contributions of planarians to the study of animal regeneration. WIREs Dev Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1002/wdev.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flickinger RA. A gradient of protein synthesis in planaria and reversal of axial polarity of regenerates. Growth. 1959;23:251–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsthoefel DJ, Newmark PA. Emerging patterns in planarian regeneration. Current Opinion in Genetics and Development. 2009;19(4):412–420. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg RM. Ion channels and drug transporters as targets for anthelmintics. Curr Clin Microbiol Rep. 2014;1(3–4):51–60. doi: 10.1007/s40588-014-0007-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdan FF, Ribeiro P. Characterization of a stable form of tryptophan hydroxylase from the human parasite Schistosoma mansoni. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(31):21746–21754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao B, Webb SE, Miller AL, Yue J. The role of Ca(2+) signaling on the self-renewal and neural differentiation of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) Cell Calcium. 2016;59(2–3):67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobert O. The neuronal genome of Caenorhabditis elegans. In: The C. elegans Research Community, editor. WormBook. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias M, Almuedo-Castillo M, Aboobaker AA, Salo E. Early planarian brain regeneration is independent of blastema polarity mediated by the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Developmental Biology. 2011;358(1):68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanatani H. Formation of bipolar heads induced by demecolcine in the planarian Dugesia gonocephala. J. Fac. Sci. Tokyo Univ. 1958;8:253–270. [Google Scholar]

- Kao D, Felix D, Aboobaker A. The planarian regeneration transcriptome reveals a shared but temporally shifted regulatory program between opposing head and tail scenarios. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:797. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klassen TL, Buckingham SD, Atherton DM, Dacks JB, Gallin WJ, Spencer AN. Atypical phenotypes from flatworm Kv3 channels. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2006;95(5):3035–3046. doi: 10.1152/jn.00858.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange CS, Steele VE. The mechanism of anterior-posterior polarity control in planarians. Differentiation. 1978;11(1):1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1978.tb00965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei K, Thi-Kim Vu H, Mohan RD, McKinney SA, Seidel CW, Alexander R, Gotting K, Workman JL, Sanchez Alvarado A. Egf Signaling Directs Neoblast Repopulation by Regulating Asymmetric Cell Division in Planarians. Developmental Cell. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SY, Selck C, Friedrich B, Lutz R, Vila-Farre M, Dahl A, Brandl H, Lakshmanaperumal N, Henry I, Rink JC. Reactivating head regrowth in a regeneration-deficient planarian species. Nature. 2013;500(7460):81–84. doi: 10.1038/nature12414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magoc T, Salzberg SL. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(21):2957–2963. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh G, Beams HW. Electrical control of morphogenesis in regenerating Dugesia tigrina. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 1952;39(2):191–213. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030390203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmark PA, Sánchez-Alvarado A. Not your father's planarian: a classic model enters the era of functional genomics. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2002;3:210–219. doi: 10.1038/nrg759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura O, Hosoda K, Kawaguchi E, Yazawa S, Hayashi T, Inoue T, Umesono Y, Agata K. Unusually Large Number of Mutations in Asexually Reproducing Clonal Planarian Dugesia japonica. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(11):e0143525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogi T, Levin M. Characterization of innexin gene expression and functional roles of gap-junctional communication in planarian regeneration. Developmental Biology. 2005;287:314–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogi T, Zhang D, Chan JD, Marchant JS. A Novel Biological Activity of Praziquantel Requiring Voltage-Operated Ca2+ Channel β subunits: Subversion of Flatworm Regenerative Polarity. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2009;3(6):e464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novozhilova E, Kimber MJ, Qian H, McVeigh P, Robertson AP, Zamanian M, Maule AG, Day TA. FMRFamide-Like Peptides (FLPs) Enhance Voltage-Gated Calcium Currents to Elicit Muscle Contraction in the Human Parasite Schistosoma mansoni. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2010;4(8):e790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo NJ, Morokuma J, Walentek P, Kema IP, Gu MB, Ahn JM, Hwang JS, Gojobori T, Levin M. Long-range Neural and Gap Junction Protein-mediated Cues Control Polarity During Planarian Regeneration. Developmental Biology. 2010;339(1):188–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang Q, Gao L, Hu W, An Y, Deng H, Zhang Y, Sun X, Zhu G, Liu B, Zhao B. De Novo Transcriptome Analysis Provides Insights into Immune Related Genes and the RIG-I-Like Receptor Signaling Pathway in the Freshwater Planarian (Dugesia japonica) PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0151597. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen CP, Reddien PW. A wound-induced Wnt expression program controls planarian regeneration polarity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(40):17061–17066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906823106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin YF, Fang HM, Tian QN, Bao ZX, Lu P, Zhao JM, Mai J, Zhu ZY, Shu LL, Zhao L, et al. Transcriptome profiling and digital gene expression by deep-sequencing in normal/regenerative tissues of planarian Dugesia japonica. Genomics. 2011;97(6):364–371. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddien PW. Constitutive gene expression and the specification of tissue identity in adult planarian biology. Trends in Genetics. 2011;27(7):277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddien PW, Bermange AL, Murfitt KJ, Jennings JR, Sánchez Alvarado A. Identification of genes needed for regeneration, stem cell function, and tissue homeostasis by systematic gene perturbation in planaria. Developmental Cell. 2005;8:635–649. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rink JC. Stem cell systems and regeneration in planaria. Development Genes and Evolution. 2013;223(1–2):67–84. doi: 10.1007/s00427-012-0426-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb SMC, Ross E, Sanchez Alvarado A. SmedGD: the Schmidtea mediterranea genome database. Nucleic Acids Research. 2008;36:D599–D606. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb SM, Gotting K, Ross E, Sanchez Alvarado A. SmedGD 2.0: The Schmidtea mediterranea genome database. Genesis. 2015;53(8):535–546. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez LV, Flickinger RA. Bipolar head regeneration in planaria induced by chick embryo extracts. Biological Bulletin. 1971;140:117–124. doi: 10.2307/1540031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg SS, Spitzer NC. Calcium signaling in neuronal development. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3(10):a004259. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustia CP. The control of biaxial development in the reconstitution of pieces of planaria. Journal of Experimental Zoology. 1925;42(1):111–142. [Google Scholar]

- Salvetti A, Rossi L, Bonuccelli L, Lena A, Pugliesi C, Rainaldi G, Evangelista M, Gremigni V. Adult stem cell plasticity: neoblast repopulation in non-lethally irradiated planarians. Developmental Biology. 2009;328(2):305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandmann T, Vogg MC, Owlarn S, Boutros M, Bartscherer K. The head-regeneration transcriptome of the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Genome Biol. 2011;12(8):R76. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-8-r76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnat HB, Netsky MG. When does a Ganglion Become a Brain? Evolutionary Origin of the Central Nervous System. Seminars in Pediatric Neurology. 2002;9:240–253. doi: 10.1053/spen.2002.32502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata N, Kashima M, Ishiko T, Nishimura O, Rouhana L, Misaki K, Yonemura S, Saito K, Siomi H, Siomi MC, et al. Inheritance of a Nuclear PIWI from Pluripotent Stem Cells by Somatic Descendants Ensures Differentiation by Silencing Transposons in Planarian. Developmental Cell. 2016;37(3):226–237. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikes JM, Newmark PA. Restoration of anterior regeneration in a planarian with limited regenerative ability. Nature. 2013;500(7460):77–80. doi: 10.1038/nature12403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer NC. Electrical activity in early neuronal development. Nature. 2006;444:707–712. doi: 10.1038/nature05300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teshirogi W. The effects of lithium chloride on head-frequency in Dugesia Gonocephela. Bulletin of the Marine Biological Station of Asamushi. 1955;7:141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner DE, Wang IE, Reddien PW. Clonogenic neoblasts are pluripotent adult stem cells that underlie planarian regeneration. Science. 2011;332(6031):811–816. doi: 10.1126/science.1203983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb SE, Miller AL. Calcium signaling during early embryonic development. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2003;4(7):539–551. doi: 10.1038/nrm1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenemoser D, Lapan SW, Wilkinson AW, Bell GW, Reddien PW. A molecular wound response program associated with regeneration initiation in planarians. Genes and Development. 2012;26(9):988–1002. doi: 10.1101/gad.187377.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler TJ. Large-scale neighbor-joining with NINJA. In: Salzberg SL, Warnow T, editors. Proceedings of the 9th Workshop on Algorithms in Bioinformatics. Berlin: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker M. Calcium at fertilization and in early development. Physiological Reviews. 2006;86:25–88. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witchley JN, Mayer M, Wagner DE, Owen JH, Reddien PW. Muscle Cells Provide Instructions for Planarian Regeneration. Cell Reports. 2013;4(4):633–641. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolstenholme AJ. Ion channels and receptor as targets for the control of parasitic nematodes. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2011;1(1):2–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtzel O, Cote LE, Poirier A, Satija R, Regev A, Reddien PW. A Generic and Cell-Type-Specific Wound Response Precedes Regeneration in Planarians. Developmental Cell. 2015;35(5):632–645. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazawa S, Umesono Y, Hayashi T, Tarui H, Agata K. Planarian Hedgehog/Patched establishes anterior-posterior polarity by regulating Wnt signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:22329–22334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907464106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu FH, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Gutman GA, Catterall WA. Overview of molecular relationships in the voltage-gated ion channel superfamily. Pharmacological Reviews. 2005;57(4):387–395. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Chan JD, Nogi T, Marchant JS. Opposing roles of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in neuronal control of stem cell differentiation in vivo. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(44):15983–15995. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3029-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.