Abstract

Cytochrome c1 from mitochondrial complex III and the di-heme cytochromes c in the corresponding enzyme from ε-proteobacteria have so far been considered to represent unrelated cytochromes. A missing link protein discovered in the genome of the hyperthermophilic bacterium Aquifex aeolicus, however, provides evidence for a close evolutionary relationship between these two cytochromes. The mono-heme cytochrome c1 from A. aeolicus contains stretches of strong sequence homology toward the ε-proteobacterial di-heme cytochromes. These di-heme cytochromes are shown to belong to the cytochrome c4 family. Mapping cytochrome c1 onto the di-heme sequences and structures demonstrates that cytochrome c1 results from a mutation-induced collapse of the di-heme cytochrome structure and provides an explanation for its uncommon structural features. The appearance of cytochrome c1 thus represents an extension of the biological protein repertoire quite different from the widespread innovation by gene duplication and subsequent diversification.

Keywords: cytochrome bc1 complex, protein repertoire extension, bioenergetic electron transfer, lateral gene transfer

Protein-based enzymes in extant organisms catalyze a virtually boundless multitude of metabolic reactions. In the early days of life on Earth, only a limited number of polypeptide modules probably evolved to take over specific catalytic roles previously fulfilled by bioinorganic catalysts (1, 2) and/or ribozymes (3). In the course of the last decade, it has become increasingly clear that this de novo invention of polypeptide modules was most probably restricted to a very short time interval after the emergence of protein-assisted metabolism. The question of how these early proteinaceous enzymes evolved into true proteins and subsequently diversified into the present-day variety of enzyme structures, functions, and interactions represents a major topic of evolutionary biology. Analysis of the rapidly growing sample of enzyme structures and primary sequences shows that, in most cases, protein modules of a basic set were duplicated, recombined, rearranged, and diversified, thus extending nature's enzyme repertoire (4). Metalloenzymes involved in bioenergetic reactions are prominent examples of such a construction-kit evolution (5–7).

Complex III (the “cytochrome bc1 complex”) is one of the three energy-coupling transmembrane complexes of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Its functional core consists of three redox proteins, a di-heme membrane integral cytochrome b, a membrane anchored [2Fe2S] protein (the so-called “Rieske protein”), and the mono-heme cytochrome c1, attached to the membrane by means of a hydrophobic helix. 3D structures show that cytochrome b and the Rieske protein form compact molecules each (with the exception of the membrane-anchoring helix of the Rieske protein sticking out of the bulk of the subunit) (8–10). Cytochrome c1, by contrast, contains a loop that protrudes 25 Å out of its globular core (Fig. 1 and 4a). This loop runs parallel to the plane of the membrane on the periplasmic surface of the complex and is stabilized by contacts solely with the symmetry-related cytochrome c1 in the second half of the dimeric bc1 complex (Fig. 1). The loop motif is conserved in the 3D-structures from avian, mammalian, and fungal mitochondrial complexes, suggesting that it is inherited from the proteobacterial ancestor of mitochondria. Indeed, multiple sequence alignments of mitochondrial and α-proteobacterial cytochrome c1 sequences demonstrate the presence of a corresponding sequence stretch in all these enzymes.

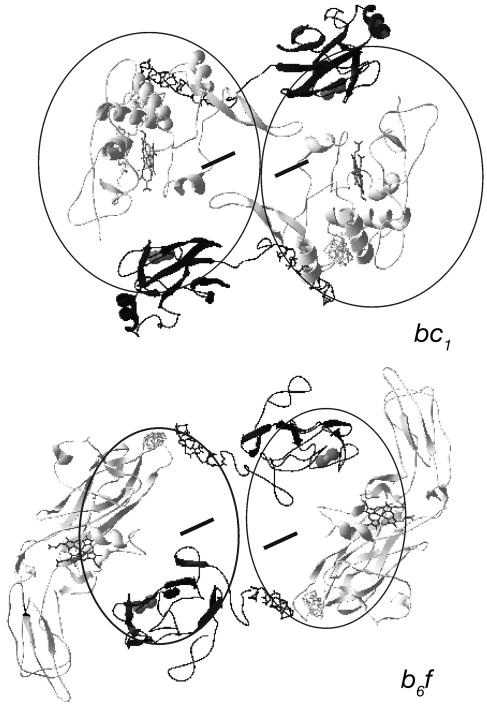

Fig. 1.

Structure and positioning of the extramembranous redox subunits in the cytochrome bc1 complex from S. cerevisae (PDB ID code 1KB9) and the cytochrome b6f complex from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (PDB ID code 1Q9O) as seen from the periplasmic/stromal side of the membrane. The direction of view is perpendicular to the membrane. Rieske proteins are depicted in gray, and cytochrome c1/f is shown in black. The contours of the transmembrane subunits of both enzymes are represented by black circles, and the hemes bL of the cytochrome b subunits are depicted as black bars.

Fig. 4.

Schematic structure and sequence comparison between cytochromes c1 and c4. (a) P. stutzeri cytochrome c4 (PDB ID code 1ETP) and cytochrome c1 from S. cerevisae (PDB ID code1KB9). The orientation of the two proteins with respect to one another was obtained by superposition of the structures with an rms of 1.5 Å for 200 Cα atoms. The heme of the di-heme cytochrome that is lost in the transition to cytochrome c1 corresponds to the heme colored in white in the cytochrome c4 structure. (b) Schematic representation of the sequence alignment of proteobacterial cytochrome c1, A. aeolicus cytochrome c1, ε-proteobacterial di-heme cytochrome c, and cytochrome c4. α-Helices are colored in blue (A, A′), green (B, B′), magenta (C, C′), and yellow, heme-binding sites are shown in red, and the PxL motif is in cyan. Putative methionine ligands are colored in black and marked with an asterisk. The region of the transmembrane helix is yellow/black. The strongly conserved (Fig. 2) CxxCH motifs, the region containing the sixth heme ligand, and the C-terminal transmembrane helix are in boxes.

In contrast to cytochrome c1 from mitochondrial complex III, the analogous subunit (cytochrome f) in the corresponding enzyme from chloroplasts and cyanobacteria, the so-called cytochrome b6f complex, has a completely different, compact structure (11–13) (Fig. 1). Functioning of the complex thus is compatible with the presence of structurally very different proteins in this segment of the enzyme. Correspondingly, an evolutionary analysis of this enzyme in a large variety of prokaryotic species demonstrated that the invariant functional core of the enzyme consists of the membrane-integral cytochrome b and the Rieske protein; thus, the term “Rieske/cytb” complex was proposed to replace the misleading notion of the bc-complexes (14). The role of the third subunit was found to be played by different mono- and di-heme cytochromes, which were so far assumed to have been integrated independently into the complex in different phyla. In particular, the di-heme cytochrome c of ε-proteobacteria was supposed to have been replaced by cytochrome c1 in the lineage leading to the α-, β-, and γ-proteobacteria and further on to the mitochondria.

The data presented here, however, establish an evolutionary relationship between cytochrome c1 and the ε-proteobacterial di-heme cytochrome. An organism has been discovered that has a typical (mono-heme) cytochrome c1 with strong sequence homologies to the ε-proteobacterial di-heme cytochrome c, thus representing the missing link between those two proteins. Their evolutionary relationship furthermore provides an explanation for the peculiar loop motif of cytochrome c1.

Materials and Methods

The known 3D structures from Bos tauris cytochrome c1 [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 1NTZ)], Saccharomyces cerevisae cytochrome c1 (PDB ID code 1KB9), and Pseudomonas stutzeri cytochrome c4 (PDB ID code 1ETP) were analyzed. Least-squares superposition of cytochrome c1 and cytochrome c4 structures were obtained by using swiss pdb viewer 3.7 (ref. 15; www.expasy.org/spdbv/). Database searches were performed with blastp (16) on the amino acid sequence database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Secondary structure prediction was performed for all proteins with no structure available to determine the positions of the α-helices and the transmembrane helix of cytochrome c1 and the di-heme cytochromes c of the ε-proteobacterial Rieske/cytb complex by using the programs psaam (www.life.uiuc.edu/crofts/ahab/psaam.html) and hydrophobic cluster analysis (ref. 17; http://smi.snv.jussieu.fr/hca/hca-form.html). The sequence alignment was guided by conserved secondary structural elements and sequence regions showing patterns of strong conservation. Conserved sequence segments and segments devoid of obvious structural or residue conservation were aligned separately with the help of the program clustalx (18) using the Blossom matrix.

Twenty-nine sequences of cytochrome c1, 4 of ε-bacterial di-heme cytochrome c, and 8 of cytochrome c4 were included in the analysis. Cytochrome c1 sequences came from the mitochondria of Arabidopsis thaliana (gi|15237497|ref|NP_198897.1|), Bos tauris (gi|117757|sp|P00125|), Homo sapiens (gi|21359867|ref|NP_001907.2|), Neurospora crassa (gi|117760|sp|P07142|), Saccharomyces cerevisae (gi|24158774|pdb|1KB9|D), Schizosaccharomyces pombe (gi|3006154|emb|CAA18395.1|), and Solanum tuberosum (gi|7547401|gb|AAB28813.2|); the α-proteobacteria Agrobacterium tumefaciens (gi|15889513|ref|NP_355194.1|), Bradyrhizobium japonicum (gi|27377597|ref|NP_769126.1|), Blasto-chloris viridis (gi|79560|pir∥JQ0347), Caulobacter crescentus (gi|16124729|ref|NP_419293.1|), Paracoccus denitrificans (gi|117761|sp|P13627|), Rhodobacter capsulatus (gi|79533|pir∥ C25405), Rhodospirillum rubrum (gi|65578|pir∥CCQF1R), Rhodobacter sphaeroides (gi|461870|sp|Q02760|), and Rickettsia prowazekii (gi|3860834|emb|CAA14734.1|); the β-proteobacteria Bordetella bronchiseptica (gi|33603845|ref|NP_891405.1), Chromobacterium violaceum (gi|34499461|ref|NP_903676.1|), Neisseria meningitidis (gi|15677873|ref|NP_275041.1|), and Ralstonia solanacearum (gi|17547646|ref|NP_521048.1|); the γ-proteobacteria Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans (gi|8547221|gb|AAF76300.1|), Allochromatium vinosum (gi|3929344|sp|O31216|), Microbulbifer degradans (gi|23027819|ref|ZP_00066251.1), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (gi|9950662|gb|AAG07817.1|), Shewanella oneidensis (gi|24372201|ref|NP_716243.1|), Vibrio vulnificus (gi|37678782|ref|NP_933391.1|), Vibrio cholerae (gi|9655006|gb|AAF93743.1|), Xanthomonas campestris (gi|21113466|gb|AAM41600.1|), and Xylella fastidiosa (gi|9105829|gb|AAF83720.1|); and the Aquificales Aquifex aeolicus (gi|15605643|ref|NP_213018.1). ε-Proteobacterial di-heme cytochrome c sequences were from Campylobacter jejuni (gi|15792508|ref|NP_282331.1), Helicobacter pylori (gi|15612526|ref|NP_224179.1), Helicobacter hepaticus (gi|32266504|ref|NP_860536.1), and Wolinella succinogenes (gi|34558433|ref|NP_908248.1). Cytochrome c4 sequences were from the β-proteobacteria Chromobacterium violaceum (gi|34499841|ref|NP_904056.1) and Neisseria meningitidis (gi|7227059|gb|AAF42142.1) and the γ-proteobacteria Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans (gi|34811346|pdb|1H1O), Azotobacter vinelandii (gi|23103051|ref|ZP_00089542.1), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (gi|15600683|ref|NP_254177.), Pseudomonas stutzeri (gi|2493972| sp|Q52369|), Vibrio vulnificus (gi|27364346|ref|NP_759874.1), and Vibrio cholerae (gi|15640144|ref|NP_229771.1).

The alignment of 17 selected sequences of representatives from α-, β-, γ-, and ε-proteobacteria, mitochondria, and the A. aeolicus cytochrome c1 is available as Fig. 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Results and Discussion

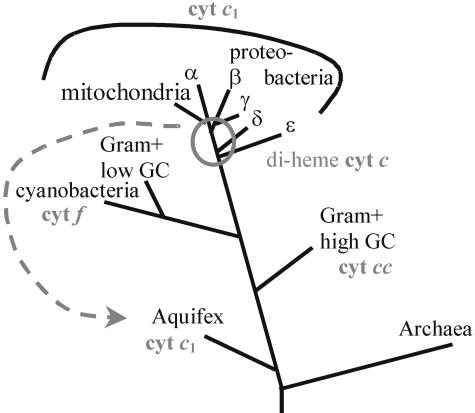

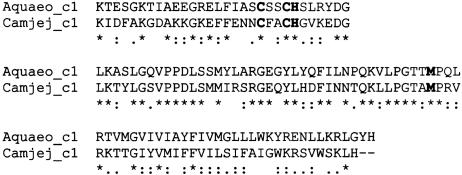

Cytochrome c1 and the ε-Proteobacterial Di-Heme Cytochromes Are Evolutionarily Related. We recently have reported the biochemical and biophysical characterization of the cytochrome bc1 complex from the hyperthermophilic bacterium A. aeolicus (6). According to both 16S rRNA (19) and whole-genome (20) analyses, the Aquificales form a very early branching phylum on the phylogenetic tree of Bacteria (Fig. 2). The Rieske protein and cytochrome b from the A. aeolicus Rieske/cytb complex, however, cluster close to the homologous proteins from ε-proteobacteria (14). Such a close relationship to (mostly γ-, δ-, or ε-) proteobacterial counterparts was found for a substantial number of genes from the A. aeolicus genome. According to our gene-by-gene analysis (M. Brugna, personal communication), about one-fifth of A. aeolicus genes cluster together with their proteobacterial homologs. The fact that the phylogenetic positioning of the large majority of A. aeolicus genes agrees with that of their parent organism on 16S rRNA trees (M. Brugna, personal communication) indicates that the “proteobacterial” complement of the A. aeolicus genome results from a massive lateral gene transfer from one or more proteobacterial donors into the Aquificales (Fig. 2). The genes of the Rieske/cytb complex in A. aeolicus belong to the proteobacterial heritage in its genome, and biochemical and biophysical analyses indeed characterized the enzyme as a genuine cytochrome bc1 complex (6). In particular, the c-type cytochrome clearly is a mono-heme cytochrome c1 (6, 14). A more detailed comparison of the A. aeolicus cytochrome c1 sequence to other cytochrome c1 and ε-proteobacterial di-heme cytochrome sequences, however, comes up with a contiguous sequence stretch of 43 residues in the A. aeolicus cytochrome c1, showing 63% identical and 81% conserved residues with a respective stretch in the di-heme cytochrome of the ε-proteobacterium C. jejuni (Fig. 3 Middle). The sequence homologies are highest for C. jejuni but extend to all known ε-proteobacterial representatives (see Fig. 5). The conserved sequence region precedes the methionine residue that most likely serves as sixth ligand to the iron atom of the sole heme in the A. aeolicus cytochrome c1 and of the heme contained in the second heme domain (see below) of the C. jejuni di-heme cytochrome. Significant sequence homologies also were found in two further stretches of the respective sequences from A. aeolicus and the ε-proteobacteria (Fig. 3 Top and Bottom). One of these two homologous stretches (Fig. 3 Bottom) consists in the ≈30 C-terminal hydrophobic residues. This region is conserved in all ε-proteobacterial di-heme cytochromes. The 3D structure of the mitochondrial bc1 complex shows the corresponding sequence region to be folded into a transmembrane α-helix anchoring cytochrome c1 to the complex and the membrane. The mode of membrane-anchoring therefore is conserved between ε-proteobacterial di-heme cytochromes and cytochromes c1. The high homology in parts of these two proteins, including the membrane anchor, provides clear evidence for an evolutionary link between the di-heme cytochromes of ε-proteobacteria and the mono-heme cytochromes c1 and thus raises the question of the evolutionary events that relate the two structurally different classes of hemoproteins.

Fig. 2.

Simplified phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA sequence comparisons (19, 28). Only the topological relationship of phyla relevant to the topic addressed in the text are included. Branch lengths are arbitrary.

Fig. 3.

Sequence stretches conserved between cytochrome c1 from A. aeolicus and the di-heme cytochrome from C. jejuni, surrounding the N-terminal heme-binding motif of the di-heme and the sole heme-binding motif of cytochrome c1 (Top), preceding the methionine ligand (Middle), and forming the predicted transmembrane α-helix (Bottom).

The ε-Proteobacterial Di-Heme Cytochromes Belong to the Cytochrome c4 Family. Sequence analysis of di-heme cytochromes from the Rieske/cytb complex of four ε-proteobacterial species unambiguously identifies them as members of the cytochrome c4 family. Cytochromes c4 have been characterized from β- and γ-proteobacteria and are thought to serve as electron donors to oxidases (21). Cytochromes c4 are di-heme cytochromes built up from a tandem repeat of two mono-heme, class I-type cytochrome domains. Each domain carries a CxxCH sequence in its N-terminal half and the sixth heme ligand methionine toward the C terminus (see Fig. 4). Two crystal structures of soluble cytochromes c4 (22, 23) are available and show the two heme domains to be related by a C2-symmetry operation with the exposed heme edges of the individual domains facing each other at the center of the protein (Fig. 4a). The specific dimeric organization of the two type-I heme domains appears to be the most favorable association of the two molecules, as illustrated by the mono-heme cytochrome c551 from Pseudomonas nautica, which in solution and in crystals spontaneously organizes into a homodimeric structure, mimicking exactly the protein and heme arrangement of cytochromes c4 (24).

Like cytochrome c4, the ε-proteobacterial di-heme cytochromes are built up from a tandem repeat of two mono-heme, class I-type cytochrome domains that show detectable sequence conservation toward each other. The di-heme cytochromes of Rieske/cytb complexes from C. jejuni, W. succinogenes, H. pylori, and H. hepaticus have 22% to 27% identical and 36% to 47% conserved residues between both domains. Secondary structure prediction reveals that their heme pockets, as in soluble cytochrome c4, feature three conserved α-helices (A, B,C and A′,B′, C′ in Fig. 4a) (22, 23). Furthermore, the PxL motif that forms, together with the CxxCH side chains from the heme-binding stretch, the surface of the heme cavity opposite to the methionine ligand in cytochrome c4 is strongly conserved (see Fig. 4). In this article, we therefore consider the 3D structure of cytochrome c4 as representative for the global structural features of the ε-proteobacterial di-heme subunits.

Correlation of Structural Elements in Cytochrome c1 and in the ε-Proteobacterial Di-Heme Cytochromes. As detailed above, the two classes of proteins are structurally quite dissimilar. ε-Proteobacterial di-heme cytochromes have a two-domain structure made up from two individual type-I cytochrome units. Cytochrome c1 basically is a single type-I cytochrome but presents, in between the CxxCH motif and the sixth ligand of the heme, an additional long sequence stretch that forms a loop motif, which does not interact with the bulk of the cytochrome. Their evolutionary relatedness is, despite their divergent structures, unambiguously demonstrated by sequence stretches with high homologies between the A. aeolicus mono-heme cytochrome c1 and the ε-proteobacterial di-heme cytochromes. The scenario that first comes to mind, consisting of a fission of the two domains of the ε-proteobacterial di-heme cytochrome and a subsequent insertion of the additional sequence stretch to give cytochrome c1, is not supported by the pattern of sequence conservation. Two of the homologous sequence stretches (Fig. 3 Middle and Bottom) are within the C-terminal domain of the di-heme cytochrome. The region surrounding the CxxCH motif in the A. aeolicus cytochrome c1, however, is significantly more homologous to the heme-binding motif of the N-terminal domain (32% identical, 61% conserved) in the ε-proteobacterial di-heme cytochrome than to the C-terminal domain (14% identical, 36% conserved). Furthermore, the sequence stretch between the N-terminal CxxCH motif and the C-terminal Met-containing patch of the ε-proteobacterial di-heme cytochrome shows weak homologies to the loop motif in the A. aeolicus cytochrome c1 connecting the CxxCH motif to the methionine ligand. Fig. 4b schematically shows the sequence alignment of mono-heme cytochrome c1 to the ε-proteobacterial di-heme cytochromes, highlighting the correspondence of structural elements.

The obtained multiple alignment indicates that nearly the entire length of the di-heme cytochrome c sequence is preserved and refolded into the mono-heme cytochrome c1, therefore suggesting the following scenario for the di-heme to cytochrome c1 transition (see also Fig. 4). (i) Damage of the covalent heme binding in the C-terminal heme domain (by mutation of cysteine residues or by deletion of a stretch containing the CxxCH motif). (ii) Collapse of the di-heme structure. The heme attached to the CxxCH motif after helix A′ of the N-terminal domain moves into the position of the (lost) heme in the C-terminal domain. Helix A′ substitutes for helix A, reforming the typical three-helix motif of the heme pocket as A′, B, C (Fig. 4a). The polypeptide chain between helix A′ and B is expelled from the heme domain, resulting in the characteristic loop of c1 cytochromes protruding away from the globular heme-binding core. A deleterious mutation in the di-heme subunit has thus resulted in the appearance of the singular structure of mono-heme cytochrome c1.

Conclusion

The data discussed above demonstrate that cytochrome c1 arose from a structural collapse of a c4-type di-heme cytochrome because of a mutational-induced corruption or deletion of its C-terminal heme-binding CxxCH motif. This appearance of a new protein structure represents an evolutionary extension of the protein repertoire quite unlike the “standard” construction-kit model involving gene duplication and diversification (4).

The loop seems to have adopted a particular function in the cytochrome bc1 complex because it is present in all cytochromes c1 ranging from 44 residues for Neismenia meningitis to 66 residues for R. capsulatus. The fact that the loop is outside the compact structural core of cytochrome c1 but interacting with the other subunits of the complex might be responsible for isolated cytochrome c1 being structurally unstable in solution (25, 26). Furthermore, during biogenesis, folding to the tertiary structure occurs as a late step in cytochrome c1 maturation, after the integration of the subunit into the complex (27). These observations support our conclusion that the structure of cytochrome c1 evolved in the context of the complex and not as a soluble mono-heme cytochrome c.

Particularly amazing in this specific case is the fact that the sequence evidence for the evolutionary relationship between the di-heme cytochrome in ε-proteobacteria and cytochrome c1 comes from a cytochrome c1 representative imported by means of horizontal gene transfer into an organism that could hardly be phylogenetically more distant from proteobacteria (see Fig. 2). No genuine proteobacterial cytochrome c1 sequence known so far would have allowed us to detect the family relationship described. It seems tempting to speculate that it is attributable to the hyperthermophilic lifestyle of A. aeolicus, generally considered to go hand-in-hand with a low rate of mutational change, that the above-discussed homologies are still recognizable despite the long time of divergence (certainly exceeding a billion years) from the Rieske/cytb complexes in ε-proteobacteria to cytochrome bc1 complex, making A. aeolicus a sequence archive of selected proteobacterial enzymes.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviation: PDB, Protein Data Bank.

References

- 1.Martin, W. & Russell, M. J. (2003) Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London B 358, 59–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milner-White, E. J. & Russell, M. J., Origins Life Evol. Biosphere, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.North, G. (1987) Nature 328, 18–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chothia, C., Gough, J., Vogel, C. & Teichmann, S. A. (2003) Science 300, 1701–1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beinert, H., Holm, R. H. & Münck, E. (1997) Science 277, 653–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schütz, M., Schoepp-Cothenet, B., Lexa, D., Woudstra, M., Lojou, E., Dolla, A., Durand, M.-C. & Baymann, F. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 10800–10808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baymann, F., Lebrun, E., Brugna, M., Schoepp-Cothenet, B., Guidici-Orticoni, M.-T. & Nitschke, W. (2003) Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London B 358, 267–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang, Z., Huang, L., Shulmeister, V. M., Chi, Y. I., Kim, K. K., Hung, L. W., Crofts, A. R., Berry, E. A. & Kim, S. H. (1998) Nature 392, 677–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwata, S., Lee, J. W., Okada, K., Lee, J. K., Iwata, M., Rasmussen, B., Link, T. A., Ramaswamy, S. & Jap, B. K. (1998) Science 281, 64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunte, C., Koepke, J., Lange, C., Rossmanith, T. & Michel, H. (2000) Structure (London) 8, 669–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stroebel, D., Choquet, Y., Popot, J.-L. & Picot, D. (2003) Nature 426, 413–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurisu, G., Zhang, H., Smith, J. L. & Cramer, W. A. (2003) Science 302, 1009–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez, S. E., Huang, D., Szczepaniak, A., Cramer, W. A. & Smith, J. L. (1994) Structure (London) 2, 95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schütz, M., Brugna, M., Lebrun, E., Baymann, F., Huber, R., Stetter, K.-O., Hauska, G., Toci, R., Lemesle-Meunier, D., Tron, P., Schmidt, C. & Nitschke, W. (2000) J. Mol. Biol. 300, 663–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guex, N. & Peitsch, M. C. (1997) Electrophoresis 18, 2714–2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. (1990) J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callebaut, I., Labesse, G., Durand, P., Poupon, A., Canard, L., Chomilier, J., Henrissat, B. & Mornon, J. P. (1997) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 53, 621–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins, D. G. & Sharp, P. M. (1989) Comput. Appl. Biosci. 5, 151–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olsen, G. J., Woese, C. R. & Overbeek, R. (1994) J. Bacteriol. 176, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snel, B., Bork, P. & Huynen, M. A. (1999) Nat. Genet. 21, 108–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rey, L. & Maier R. J. (1997) J. Bacteriol. 179, 7191–7196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kadziola, A. & Larsen, S. (1997) Structure (London) 5, 203–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abergel, C., Nitschke, W., Malarte, G., Bruschi, M., Claverie, J.-M. & Guidici-Orticoni, M.-T. (2003) Structure (London) 11, 547–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown, K., Nurizzo, D., Besson, S., Shepard, W., Moura, J., Moura, I., Tegoni, M. & Cambillau, C. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 289, 1017–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finnegan, M. G., Knaff, D. B., Qin, H., Gray, K. A., Daldal, F., Yu, L., Yu, C.-A., Kleis-San Francisco, S. & Johnson, M. K. (1996) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1274, 9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, J., Darrouzet, E., Dhawan, I. K., Johnson, M. K., Osyczka, A., Daldal, F. & Knaff, D. B. (2002) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1556, 175–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thöny-Meyer, L. (1997) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61, 337–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gruber, T. M. & Bryant, D. A. (1997) J. Bacteriol. 179, 1734–1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.