Abstract

Dracaena cochinchinensis Lour. is an ethnomedicinally important plant used in traditional Chinese medicine known as dragon's blood. Excessive utilization of the plant for extraction of dragon's blood had resulted in the destruction of the important niche. During a study to provide a sustainable way of utilizing the resources, the endophytic Actinobacteria associated with the plant were explored for potential utilization of their medicinal properties. Three hundred and four endophytic Actinobacteria belonging to the genera Streptomyces, Nocardiopsis, Brevibacterium, Microbacterium, Tsukamurella, Arthrobacter, Brachybacterium, Nocardia, Rhodococcus, Kocuria, Nocardioides, and Pseudonocardia were isolated from different tissues of D. cochinchinensis Lour. Of these, 17 strains having antimicrobial and anthracyclines-producing activities were further selected for screening of antifungal and cytotoxic activities against two human cancer cell lines, MCF-7 and Hep G2. Ten of these selected endophytic Actinobacteria showed antifungal activities against at least one of the fungal pathogens, of which three strains exhibited cytotoxic activities with IC50-values ranging between 3 and 33 μg·mL−1. Frequencies for the presence of biosynthetic genes, polyketide synthase- (PKS-) I, PKS-II, and nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) among these 17 selected bioactive Actinobacteria were 29.4%, 70.6%, and 23.5%, respectively. The results indicated that the medicinal plant D. cochinchinensis Lour. is a good niche of biologically important metabolites-producing Actinobacteria.

1. Introduction

Actinobacteria, especially the genus Streptomyces, are major producers of bioactive metabolites [1] and account for nearly 75% of the total antibiotic production available commercially [2, 3]. A few decades ago, antibiotics were considered as wonder drugs since they warded off deadly pathogens leading to eradication of infectious diseases. However, the unprecedented deployment of antibiotics over a period of time has resulted in evolution of multidrug-resistant pathogens. There is increasing attention to bioprospecting of Actinobacteria from different biotopes. With limiting bioresources, it is now imperative for search of unexplored or underexplored habitats. One such overlooked and promising niche is the inner tissues of plants, especially those with ethnomedicinal value [4–10].

The plant Dracaena cochinchinensis Lour. has been used as a traditional folk medicine in the oriental countries including China [11]. D. cochinchinensis Lour. has many medicinally important properties, like antimicrobial, antiviral, antitumor, cytotoxic, analgesic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, haemostatic, antidiuretic, antiulcer, and wound healing activities [10, 12]. The plant is the source of deep red resin having medicinal properties which is also known as dragon's blood. The main components of dragon's blood are flavonoids and stilbenoids [13]. Apart from its medicinal use, it also finds applications as colouring materials and wood varnish [12]. The slow growth of the plant along with low yield of dragon's blood extracts, however, led to the destruction of large number of these plants, thereby endangering the plant. The current study described the diversity of culturable Actinobacteria associated with this medicinal plant and also indicated the cytotoxic potential of these Actinobacteria. The study, in a way, proposed a means for sustainable use of the plant resources without destroying the natural niche.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Isolation of Endophytic Actinobacteria

Healthy plant samples (leaves, stems, and roots) of medicinal plant D. cochinchinensis Lour. were collected from four different provinces located in two countries: Pingxiang, Guangxi province, China (20°06′02′′N, 106°45′01′′E; elevation, 236 m); Xishuangbanna, Yunnan province, China (21°55′41′′N, 101°25′49′′E; 984 m); Bach Ma National Park, Thua Thien Hue province, Vietnam (16°9′55′′N, 107°55′19′′E; 1450 m), and Cuc Phuong National Park, Ninh Binh province, Vietnam (20°19′8′′N, 105°37′20′′E; 338 m). The plant samples were packed in sterile plastics, taken to the laboratory, and subjected to isolation procedures within 96 h. The samples were washed thoroughly with running tap water and in ultrasonic bath to remove any adhering soil particles and air-dried at ambient temperature for 48 h.

Two methods were employed for the isolation of the endophytic Actinobacteria using seven specific isolation media (Table 1).

Table 1.

Composition of the seven media used for the isolation of endophytic Actinobacteria from Dracaena cochinchinensis Lour.

| Medium | Name and composition (g L−1of water) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Tap water-yeast extract agar (TWYE) Yeast extract 0.25, K2HPO4 0.5, agar 15 |

[3, 5] |

|

| ||

| 2 |

Trehalose agar Trehalose 6, KNO3 0.5, CaCl2 0.3, Na2HPO4 0.3, MgSO4·7H2 O 0.2, agar 15 |

[5] |

|

| ||

| 3 |

Sodium propionate agar Sodium propionate 2, NH4NO3 0.1, KCl 0.1, MgSO4·7H2 O 0.05, FeSO4·7H2 O 0.05, agar 15 |

[5] |

|

| ||

| 4 |

Starch agar Starch 2, KNO3 1, NaCl 0.4, K2HPO4 0.5, MgSO4·7H2 O 0.5, FeSO4·7H2 O 0.01, agar 15 |

[5] |

|

| ||

| 5 |

Citrate agar Citric acid 0.12, ferric ammonium citrate 0.12, NaNO3 1.5, K2 HPO4·3H2 O 0.4, MgSO4·7H2 O 0.1, CaCl2·H2O 0.05, EDTA 0.02, Na2CO3 0.2, agar 15 |

This study |

|

| ||

| 6 |

Sodium propionate-asparagine-salt agar Sodium propionate 4, asparagine 1, casein 2, K2HPO4 1, MgSO4·7H2 O 0.1, FeSO4·7H2 O 0.01, NaCl 30, agar 15 |

[5] |

|

| ||

| 7 |

Dulcitol-proline agar Dulcitol 2, proline 0.5, K2HPO4 0.3, NaCl 0.3, MgSO4·7H2 O 1, CaCl2·2H2 O 1, agar 15 |

This study |

Method 1 . —

The plant parts of D. cochinchinensis Lour. were excised and subjected to a five-step surface-sterilization procedure: a 4 min wash in 5% NaOCl, followed by 10 min wash in 2.5% Na2S2O3, a 5 min wash in 75% ethanol, a wash in sterile water, and a final rinse in 10% NaHCO3 for 10 min. After drying thoroughly under sterile conditions, the surface sterilized tissues were disrupted aseptically in a commercial blender and distributed on isolation media [5, 7].

Method 2 . —

The surface sterilized plant parts (1-2 g) were sliced, grounded with mortar and pestle, and mixed with 0.5 g CaCO3. The samples were kept in a laminar flow cabinet for 14 d, incubated at 80°C for 30 min, and plated onto isolation media [7].

Each medium was supplemented with nalidixic acid (25 mg·L−1), nystatin (50 mg·L−1), and K2Cr2O7 (50 mg·L−1) to inhibit the growth of Gram-negative bacteria and fungi; polyvinyl pyrrolidone (2%) and tannase (0.005%) were also added to improve the development of colonies on media. Colonies grown on these isolation media were selected and purified by repeated streaking on YIM 38 medium. The pure cultures were preserved as glycerol suspensions (20%, v/v) at −80°C and as lyophilized spore suspensions in skim milk (15%, w/v) at 4°C.

2.2. Identification and Diversity Profiling

For phylogenetic characterization, genomics DNAs of all isolates were extracted using an enzyme hydrolysis method. About 50 mg of the freshly grown culture was taken in an autoclaved 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube. To the culture, 480 μL TE buffer (1x) and 20 μL lysozyme solution (2 mg·mL−1) were added. The bacterial suspension was thoroughly mixed and incubated for 2 h under shaking conditions (160 rpm, 37°C). The mixture was treated with 50 μL SDS solution (20%, w/v) and 5 μL Proteinase K solution (20 μg·mL−1) and kept on a water bath (55°C, 1 h). DNA was then extracted twice with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25 : 24 : 1 v/v/v), followed by precipitation with 80 μL sodium acetate (3 mol·L−1, pH 4.8–5.2) and 800 μL absolute ethanol. The resulting DNA precipitate was centrifuged at 4°C (12,000 rpm, 10 min), washed with 70% ethanol, and then air-dried. The extracted DNA was resuspended in 30 μL TE buffer and stored at −20°C. PCR amplification for 16S rRNA gene from the extracted DNA samples was done using the primer pair PA-PB (PA: 5′-CAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCT-3′; PB: 5′-AGGAGGTGATCCAGCCGCA-3′) as described previously [14]. Amplified PCR products were purified and sequenced by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai). Identification of phylogenetic neighbours and calculation of pairwise 16S rRNA gene sequence similarities were achieved using the EzTaxon server (http://www.eztaxon.org/) [15] and BLAST analysis (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The alignment of the sequences was done using CLUSTALW [16]. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the aligned sequences by the neighbour-joining method [17] using Kimura 2-parameter distances [18] in the MEGA 6 software [19]. To determine the support of each clade, bootstrap analysis was performed with 1,000 replications [20].

2.3. Selection of Bioactive Actinobacteria Strains

Each of the isolated Actinobacteria was screened for antimicrobial activity and anthracyclines production. The antibacterial activities were evaluated against Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE) ATCC 35984, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) ATCC 25923, Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) ATCC 29213, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883, Aeromonas hydrophila ATCC 7966, and Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 using the agar well diffusion method [21]. Anthracycline productivity was screened using the pigment production test as described by Trease [22]. Based on the results of the two screenings, bioactive strains were selected for further assays.

2.4. Antifungal and Cytotoxicity Tests

Antifungal activity of the selected bioactive strains was tested against Fusarium graminearum, Aspergillus carbonarius, and Aspergillus westerdijkiae (strains producing the mycotoxins deoxynivalenol and ochratoxin A) [23, 24]. These test pathogens were provided by CIRAD, UMR QUALISUD, France, and maintained on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA).

The cytotoxic activity of the selected strains was tested by sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay as described earlier [25–27]. The human breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7) and human hepatocellular carcinoma (Hep G2) cells lines used for the test were procured from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Boulevard, Manassa, VA 20110, USA). Ellipticine was used as the positive control.

2.5. Screening for Biosynthetic Genes

Three sets of PCR primers A3F/A7R, K1F/M6R, and KSαF/KSαR were used for amplification of nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS), polyketide synthase- (PKS-) I, and PKS-II specific domains [6, 28]. PCR amplifications were performed in a Biometra thermal cycler in a final volume of 25 μL containing 0.2 μmol·L−1 of each primer, 0.1 μmol·L−1 of each of the four dNTPs (Takara, Japan), 2.5 μL of extracted DNA, 0.5 unit of Taq DNA polymerase (with its recommended reaction buffer), and 10% of DMSO. Amplifications were performed according to the following profile: initial denaturation at 96°C for 5 min; 30 cycles of denaturation at 96°C for 1 min, primer annealing at either 57°C (for K1F/M6R, A3F/A7R) or 58°C (for KSαF/KSαR) for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The sizes of amplicons were 1,200–1,400 bp (K1F/M6R), 613 bp (KSαF/KSαR), and 700–800 bp (A3F/A7R).

3. Results

3.1. Isolation of Endophytic Actinobacteria

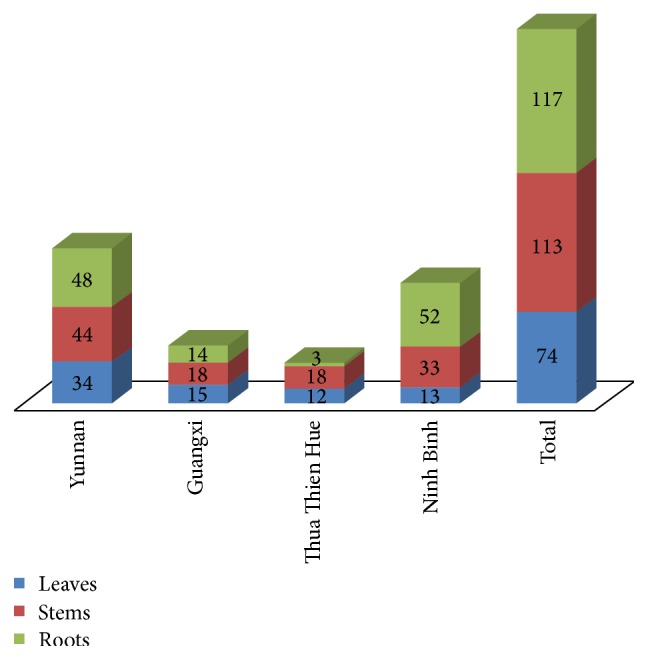

A total of 304 putative endophytic Actinobacteria were isolated from three different tissues of D. cochinchinensis Lour. The highest number of Actinobacteria was isolated from roots (117 strains, 38.49%), followed by stems (113 strains, 37.17%) and leaves (74 strains, 24.34%) (Figure 1). Among the sites, more Actinobacteria were isolated from Xishuangbanna (Yunnan province, China) and Cuc Phuong National Park (Ninh Binh province, Vietnam) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of endophytic Actinobacteria isolated from the different tissues of Dracaena cochinchinensis Lour. among the different sampling sites.

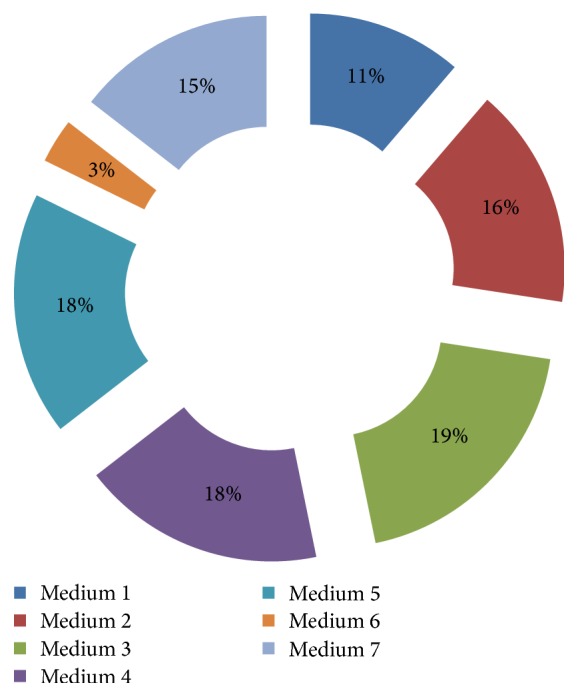

During the present study, Method 2 was found to be more suitable for the isolation of endophytic Actinobacteria from tissues of D. cochinchinensis Lour. and accounted for nearly 65% of the total isolation. All the media used in the current study, except for sodium propionate-asparagine-salt agar, were suitable for isolation of endophytic Actinobacteria (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of media on the isolation of endophytic Actinobacteria.

3.2. Diversity Profiling

Based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis, the most abundant Actinobacteria genera were Streptomyces (86.84%), followed by Nocardiopsis (4.93%), Brevibacterium (1.64%), Microbacterium (1.64%), Tsukamurella (1.64%), Arthrobacter (0.66%), Brachybacterium (0.66%), Nocardia (0.66%), Rhodococcus (0.66%), Kocuria (0.33%), Nocardioides (0.33%), and Pseudonocardia (0.33%). The relative abundance of the endophytic Actinobacteria among the different sites is shown in Table 2. Among the different sampling sites, Yunnan and Ninh Binh yielded the highest diversity, each contributing eight genera of Actinobacteria. Yunnan samples yielded the genera Streptomyces, Nocardiopsis, Brevibacterium, Microbacterium, Brachybacterium, Rhodococcus, Kocuria, and Tsukamurella, while Ninh Binh samples yielded Streptomyces, Tsukamurella, Nocardiopsis, Arthrobacter, Nocardia, Brevibacterium, Nocardioides, and Pseudonocardia. Thua Thien Hue samples contained Streptomyces, Nocardiopsis, and Microbacterium, while Streptomyces and Nocardiopsis were present in Guangxi samples.

Table 2.

Distribution of endophytic Actinobacteria isolated from the different tissues of D. cochinchinensis Lour. among the different sampling sites.

| Genera | Yunnan China |

Guangxi China |

Thua Thien Hue Vietnam |

Ninh Binh Vietnam |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthrobacter | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Brachybacterium | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Brevibacterium | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Kocuria | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Microbacterium | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Nocardia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Nocardioides | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Nocardiopsis | 8 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 15 |

| Pseudonocardia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Rhodococcus | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Streptomyces | 104 | 46 | 30 | 82 | 262 |

| Tsukamurella | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 |

|

| |||||

| Total | 126 | 47 | 33 | 98 | 304 |

3.3. Selection of Bioactive Actinobacteria Strains

All 304 Actinobacteria isolates were tested for antimicrobial activity and anthracycline production. Table 3 represents the distribution of bioactive Actinobacteria. These bioactive strains were distributed in the genera Streptomyces, Nocardiopsis, Nocardioides, Pseudonocardia, and Tsukamurella. The genus Streptomyces possessed the highest proportion of isolates with antimicrobial activities. Anthracyclines are important group of antitumor antibiotics and are being used in cancer treatment [29, 30]. Of the 304 strains, 49 strains tested positive for anthracycline production.

Table 3.

Bioactivity profiles of the endophytic Actinobacteria isolated from D. cochinchinensis Lour.

| Genera | Antimicrobial activity | Anthracycline production | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATCC 35984 | ATCC 25923 | ATCC 29213 | ATCC 13883 | ATCC 7966 | ATCC 25922 | ||

| Arthrobacter | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Brachybacterium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Brevibacterium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kocuria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Microbacterium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nocardia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nocardioides | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Nocardiopsis | 0 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Pseudonocardia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Rhodococcus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Streptomyces | 70 | 68 | 70 | 70 | 96 | 53 | 46 |

| Tsukamurella | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

|

| |||||||

| Total | 70 | 71 | 76 | 72 | 98 | 53 | 49 |

|

| |||||||

| Proportion (%) | 23.03 | 23.26 | 25.00 | 23.68 | 32.43 | 17.43 | 16.11 |

Note. Number indicates number of isolates positive for the particular bioactivity.

ATCC 35984, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE); ATCC 25923, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA); ATCC 29213, Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA); ATCC 13883, Klebsiella pneumoniae; ATCC 7966, Aeromonas hydrophila; ATCC 25922, Escherichia coli.

Based on the results of the bioactivity screening, 17 strains (HUST001-HUST011, HUST013-HUST015, HUST017, HUST018, and HUST026) were selected for further antifungal and cytotoxicity studies (Table 4). Of the 17 strains, 14 belonged to the genera Streptomyces while the rest comprised Nocardioides, Nocardiopsis, and Pseudonocardia (Figure 3).

Table 4.

Isolation and characterization profile of the 17 selected endophytic Actinobacteria.

| Strain | Sampling site∗ | Isolation medium | Isolation method | Source | Accession number | Closest homologs | Pairwise similarity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HUST001 | NB | 3 | 2 | Stem | KT033860 | Streptomyces puniceus NBRC 12811T | 100.0 |

| HUST002 | GX | 2 | 1 | Stem | KP317660 | Streptomyces violarus NBRC 13104T | 99.45 |

| HUST003 | TTH | 5 | 1 | Stem | KT033861 | Streptomyces cavourensis NBRC 13026T | 99.70 |

| HUST004 | YN | 3 | 2 | Root | KT033862 | Streptomyces cavourensis NBRC 13026T | 100.0 |

| HUST005 | NB | 4 | 2 | Stem | KT033863 | Streptomyces parvulus NBRC 13193T | 99.73 |

| HUST006 | NB | 3 | 2 | Stem | KT033864 | Streptomyces rubiginosohelvolus NBRC 12912T | 99.72 |

| HUST007 | YN | 5 | 1 | Root | KT033865 | Streptomyces puniceus NBRC 12811T | 100.0 |

| HUST008 | TTH | 6 | 2 | Stem | KT033866 | Streptomyces puniceus NBRC 12811T | 99.80 |

| HUST009 | YN | 3 | 2 | Stem | KT033867 | Streptomyces puniceus NBRC 12811T | 98.66 |

| HUST010 | YN | 2 | 1 | Root | KT033868 | Streptomyces pluricolorescens NBRC 12808T | 100.0 |

| HUST011 | GX | 3 | 1 | Root | KT033869 | Streptomyces parvulus NBRC 12811T | 100.0 |

| HUST013 | NB | 4 | 1 | Root | KT033870 | Pseudonocardia carboxidivorans Y8T | 100.0 |

| HUST014 | TTH | 5 | 1 | Root | KT033871 | Streptomyces augustmycinicus NBRC 3934T | 99.85 |

| HUST015 | TTH | 7 | 2 | Stem | KT033872 | Streptomyces violarus NBRC 13104T | 99.57 |

| HUST017 | YN | 2 | 2 | Leaf | KT033873 | Nocardiopsis dassonvillei subsp. albirubida DSM 40465T | 100.0 |

| HUST018 | NB | 1 | 2 | Root | KT033874 | Streptomyces graminisoli JR-19T | 99.45 |

| HUST026 | NB | 1 | 2 | Root | KT033859 | Nocardioides ganghwensis JC2055T | 98.26 |

∗YN, Xishuangbanna, Yunnan province, China; GX, Pingxiang, Guangxi province, China; TTH, Bach Ma National Park, Thua Thien Hue province, Vietnam; NB, Cuc Phuong National Park, Ninh Binh province, Vietnam.

Figure 3.

Neighbour-joining phylogenetic dendrogram based on 16S rRNA gene sequences showing the relationship of the selected 18 endophytic Actinobacteria with their closest species.

3.4. Evaluation of Antifungal and Cytotoxicity Effects of the Bioactive Strains

Several strains among the selected bioactive Actinobacteria were positive for antifungal activities against the mycotoxins-producing F. graminearum, A. carbonarius, and A. westerdijkiae strains. Frequencies of the antifungal activities against the indicator fungal pathogens were as follows: F. graminearum: 58.8%; A. carbonarius: 41.2%; and A. westerdijkiae: 23.5%. Table 5 summarizes the antifungal profile of the selected 17 strains.

Table 5.

Antifungal, cytotoxic, and biosynthetic gene profiles of the 17 selected endophytic Actinobacteria isolated from D. cochinchinensis Lour.

| Strain | Test pathogens | Cytotoxicity on MCF-7 (given in % inhibition) | Cytotoxicity on Hep G2 (given in % inhibition) | Biosynthetic genes | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fusarium graminearum | Aspergillus carbonarius | Aspergillus westerdijkiae | Concentration (μg·ml−1) | |||||||||||||||

| 10000 | 2000 | 400 | 80 | 16 | IC50 | 10000 | 2000 | 400 | 80 | 16 | IC50 | PKS-I | PKS-II | NRPS | ||||

| HUST001 | + | − | − | 101.74 | 94.48 | 70.47 | 63.70 | 48.84 | 19 | 103.92 | 103.29 | 102.75 | 56.25 | 12.42 | 68 | − | + | − |

| HUST002 | − | − | − | 112.12 | 89.42 | 62.60 | 31.86 | 15.99 | 194 | 105.66 | 94.93 | 45.31 | 17.74 | 4.48 | 547 | − | + | − |

| HUST003 | + | + | + | 106.71 | 97.45 | 67.50 | 44.38 | 19.33 | 120 | 109.97 | 109.29 | 90.54 | 54.56 | −4.41 | 56 | + | + | + |

| HUST004 | + | + | + | 105.40 | 88.68 | 73.52 | 62.87 | 56.94 | 3 | 109.18 | 107.70 | 103.23 | 87.50 | 62.08 | 10 | + | + | + |

| HUST005 | + | + | + | 107.96 | 106.95 | 103.59 | 58.13 | 44.02 | 25 | 109.38 | 95.95 | 97.89 | 56.33 | 37.92 | 33 | − | + | + |

| HUST006 | − | − | − | 78.54 | 17.16 | 5.59 | −1.08 | −10.50 | 5710 | 88.18 | 13.60 | 9.25 | −2.98 | −5.14 | 5745 | − | − | − |

| HUST007 | + | − | − | 97.06 | 82.03 | 33.40 | 25.28 | 18.73 | 832 | 125.34 | 107.26 | 35.64 | −3.78 | −5.46 | 587 | + | − | − |

| HUST008 | − | − | − | 99.71 | 81.92 | 42.76 | 30.32 | 11.34 | 399 | 105.41 | 103.72 | 27.53 | 8.78 | −2.05 | 633 | − | − | − |

| HUST009 | − | − | − | 94.51 | 84.24 | 26.54 | 16.43 | 8.34 | 870 | 121.62 | 104.90 | 18.83 | −6.83 | −17.04 | 688 | + | + | − |

| HUST010 | + | + | − | 98.86 | 98.72 | 68.98 | 29.28 | 11.93 | 166 | 98.50 | 97.87 | 58.09 | 34.39 | 13.29 | 271 | − | + | − |

| HUST011 | + | + | − | 98.10 | 54.71 | 47.71 | 39.48 | 24.42 | 695 | 85.25 | 47.37 | 27.53 | 13.06 | −14.29 | 1721 | + | + | − |

| HUST013 | − | − | − | 53.93 | 0.62 | −3.91 | −5.34 | −6.81 | 9517 | 9.34 | −3.28 | −14.36 | −19.50 | −13.38 | >10000 | − | + | − |

| HUST014 | + | − | − | 91.67 | 80.05 | 52.38 | 43.63 | 11.27 | 249 | 109.90 | 106.17 | 86.86 | 46.85 | −6.02 | 77 | − | − | − |

| HUST015 | − | − | − | 99.05 | 83.68 | 70.60 | 37.20 | 15.59 | 129 | 101.49 | 97.87 | 76.25 | 32.02 | −4.37 | 172 | − | + | − |

| HUST017 | − | − | − | 22.66 | −0.40 | −1.00 | −2.63 | −8.75 | >10000 | −1.27 | −1.70 | −2.76 | −1.54 | −12.18 | >10000 | − | − | − |

| HUST018 | + | + | − | 42.02 | 6.29 | 4.41 | −1.26 | 0.57 | >10000 | 32.18 | −0.88 | −2.25 | −12.44 | −15.58 | >10000 | − | + | + |

| HUST026 | + | + | + | 92.08 | 86.55 | 37.72 | 28.64 | 22.61 | 623 | 104.63 | 86.23 | 38.05 | 21.95 | 10.72 | 691 | − | + | − |

Of the 17 strains, three strains (HUST001, HUST004, and HUST005) exhibited cytotoxic effects against the two tested human cancer cell lines, MCF-7 and Hep G2 (Table 5). Strain HUST004 showed significant inhibition toward MCF-7 cells with IC50-value of 3 μg·mL−1, while strains HUST001 and HUST005 showed moderate activity with IC50-values of 19 and 25 μg·mL−1, respectively. Against Hep G2 cell lines, IC50-values for the strains HUST004 and HUST005 were 10 and 33 μg·mL−1, respectively. The remaining strains were inactive against the two cancer cell lines.

3.5. Screening of Biosynthetic Genes

All 17 bioactive strains were investigated for the presence of PKS-I, PKS-II, and NRPS genes. Frequencies of positive PCR amplification of the three biosynthetic systems were 29.41%, 70.59%, and 23.53%, respectively (Table 5). All these three genes were detected in two strains (HUST003, HUST004), which were identified as members of the genus Streptomyces. PKS-II gene was detected at highest frequencies in both Streptomyces and non-Streptomycetes genera, while PKS-I and NRPS genes were detected only in the genus Streptomyces.

4. Discussion

The plant source D. cochinchinensis is known for the production of dragon's blood [11]. Traditional practices of folk medicine involved extraction of dragon's blood from the plant. During its extraction, large scale exploitation of the plant is necessary owing to the low yield of plant's extract and slow growth of the plant, thereby resulting in destruction of large number of century old plant [13]. It is, therefore, imperative to search for alternative source of the plant's metabolites to preserve the plant in its natural niche. One such means is to study the endophytic microbes associated with the plant. In an earlier study by Cui et al. [35], D. cochinchinensis collected from Beijing, China, had been used to study the endophytic fungal diversity. The study resulted in the isolation of 49 fungal strains distributed into 18 genera. In another study of endophytic microbe associated with D. cochinchinensis, Khieu et al. [10] had isolated a Streptomyces strain, producing two potent cytotoxic compounds, from plant samples collected from Cuc Phuong National Park, Ninh Binh province, Vietnam. But neither of these studies described the diversity profile of the Actinobacteria communities living in association with the plant. As endophytic Actinobacteria from medicinal plants have been a major research area in the search of new antibiotic-producing strains [4, 7, 8, 36–39], we have selected the same plant source for in-depth analysis of Actinobacteria community structure. The present study resulted in the isolation of 304 Actinobacteria strains.

Many reports suggested that maximum endophytes were recovered from roots, followed by stems and leaves [9, 31–34]. Similar observation was found during our study whereby more number of isolates was obtained from roots than from stems or leaves (Table 6). This may be due to the fact that rhizospheric regions of the soil have higher concentration of nutrients. A report also suggested that microorganism enters various tissues of plant from rhizosphere and switched to endophytic lifestyles [40, 41]. Isolation of more isolates using the second method may be attributed to the enrichment of the samples with calcium carbonate. Qin et al. [7] have reported that calcium carbonate altered the pH to alkaline conditions which favour the growth of Actinobacteria.

Table 6.

Comparative endophytic Actinobacteria diversity profile from different plant sources.

| Plant sources | Number of isolates from different tissues | Diversity profile∗ | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | Roots | Stems | Others | |||

| Artemisia annua (Yunnan, China) | / | / | / | / | Streptomyces (123); Promicromonospora (26); Pseudonocardia (15); Nocardia (11); Nonomuraea (10); Rhodococcus (8); Kribbella (7); Micromonospora (7); Actinomadura (6); Amycolatposis (3); Streptosporangium (3); Dactylosporangium (2); Blastococcus (1); Glycomyces (1); Gordonia (1); Kocuria (1); Microbispora (1); Micrococcus (1); Phytomonospora (1) | [6] |

|

| ||||||

| Maytenus austroyunnanensis (Yunnan, China) | 102 | 126 | 84 | / | Streptomyces (208); Pseudonocardia (22); Nocardiopsis (21); Micromonospora (17); Promicromonospora (6); Streptosporangium (6); Actinomadura (4); Amycolatopsis (4); Nonomuraea (4); Mycobacterium (3); Glycomyces (2); Gordonia (2); Microbacterium (2); Plantactinospora (2); Saccharopolyspora (2); Tsukamurella (2); Cellulosimicrobium (1); Janibacter (1); Jiangella (1); Nocardia (1); Polymorphospora (1) | [9] |

|

| ||||||

| 36 plant species (Chiang Mai, Thailand) | 97 | 212 | 21 | / | Streptomyces (277); Microbispora (14); Nocardia (8); Micromonospora (4); uncharacterized (27) | [31] |

|

| ||||||

| Azadirachta indica A. Juss. (Varanasi, India) | 12 | 30 | 13 | / | Streptomyces (27); Streptosporangium (8); Microbispora (6); Streptoverticillium (3); Saccharomonospora (3); Nocardia (2) | [32] |

|

| ||||||

| 7 plant species (Mizoram, India) | 6 | 22 | 9 | 2 | Streptomyces (23); Microbacterium (9); Leifsonia (1); Brevibacterium (1); Uncharacterized (3) | [33] |

|

| ||||||

| 26 species (Sichuan, China) | 78 | 326 | 156 | / | Streptomyces, Micromonospora, Nonomuraea, Oerskovia, Promicromonospora, Rhodococcus | [34] |

|

| ||||||

| Dracaena cochinchinensis Lour. (China and Vietnam) | 74 | 117 | 113 | / | Streptomyces (264); Nocardiopsis (15); Brevibacterium (5); Microbacterium (5); Tsukamurella (5); Arthrobacter (2); Brachybacterium (2); Nocardia (2); Rhodococcus (2); Kocuria (1); Nocardioides (1); Pseudonocardia (1) | This study |

∗Number within parentheses indicates the number of strains from each genera; / indicates no data.

Among various genera isolated, Streptomyces is predominantly present in the plant D. cochinchinensis. The finding is consistent with similar studies of endophytic bacteria [6, 9, 32, 33, 36]. In the present study, rare Actinobacteria of the genera Arthrobacter, Brevibacterium, Kocuria, Microbacterium, Nocardia, Nocardioides, Nocardiopsis, Pseudonocardia, Rhodococcus, and Tsukamurella were also isolated. Though Arthrobacter, Brevibacterium, Microbacterium, Nocardia, Nocardioides, Nocardiopsis, Pseudonocardia, Rhodococcus, and Tsukamurella have been reported as endophytic Actinobacteria of medicinal plant [6, 7, 31–34], this study forms the first report for the isolation of Brachybacterium and Kocuria (Table 6).

Endophytic Actinobacteria are often associated with antimicrobial properties [6, 7, 31]. This is shown by the high proportion of antibacterial activities by endophytic Actinobacteria associated with D. cochinchinensis Lour.: 23.03% against ATCC 35984, 23.26% against ATCC 25923, 25% against ATCC 29213, 23.68% against ATCC 13883, 32.43% against ATCC 7966, and 17.43% against ATCC 25922. Based on the preliminary bioactivity profile, a set of 17 Actinobacteria were further studied for antifungal and cytotoxic properties. Of the 17 strains selected, 10 strains were significant against F. graminearum, seven against A. carbonarius, and four against A. westerdijkiae. Similar findings have been reported in related studies of Streptomyces strains [42–44]. Four strains (HUST003, HUST004, HUST005, and HUST026) showed remarkable antifungal activity against all test fungi (Table 5). In contrast to above strains, HUST002, HUST006, HUST008, HUST009, HUST013, HUST015, and HUST017 did not show any antifungal activity.

In the study of Cui et al. [35], it was indicated that 71% of the fungal isolates obtained from D. cochinchinensis exhibited varied antitumor activities against five human cancer cell lines: HepG2, MCF7, SKVO3, Hl-60, and 293-T. Similarly, in the study of Khieu et al. [10], the compounds (Z)-tridec-7-3n3-1,2,13-tricarboxylic acid and Actinomycin-D produced by a Streptomyces sp. exhibited cytotoxic effect against two human cancer cell lines HepG2 and MCF-7. During the current study, three of the Streptomyces strains (HUST001, HUST004, and HUST005) produced potential cytotoxic activities. All the three studies on D. cochinchinensis indicated that the endophytic microbes associated with the plant are alternative sources for extraction of cytotoxic compounds. These studies further indicated that endophytic microbes can serve as a means for sustainable utilization of the plant resources by preserving the natural niche.

The cytotoxic abilities (IC50-values) of the three strains HUST001, HUST004, and HUST005 against the human cancer cell lines MCF-7 and/or Hep G2 range in between 3 and 33 μg·mL−1. This finding is significant with reference to related studies [44–47]. Lu and Shen [45] isolated naphthomycin K from endophytic Streptomyces strain CS which exhibit cytotoxic activity against P388 and A-549 cell lines with IC50-values of 0.07 and 3.17 μmol·L−1. Kim et al. [48] isolated salaceyins A and B from Streptomyces laceyi MS53 having IC50-values of 3.0 and 5.5 μg·mL−1 against human breast cancer cell line SKBR3.

The biosynthetic genes are involved in microbial natural product biosynthesis. The antitumor drug bleomycin from Streptomyces verticillus ATCC 15003 involved a hybrid NRPS-PKS system [49]. Genomic analysis of the specific strain will, however, be necessary for illustration of the presence of biosynthetic gene clusters. Despite this fact, positive reaction for the amplification of specific domains for the three biosynthetic gene clusters is an indirect indication for the presence of the biosynthetic gene. In the present study, 13 of the 17 bioactive strains were found to have at least one of the three biosynthetic gene clusters. Among them, strains HUST003 and HUST004 showed positive results for the presence of PKS-I, PKS-II, and NRPS genes and also exhibited antifungal activity against all test pathogens (Table 5). Strains HUST006, HUST008, and HUST017 were negative both for the presence of PKS-I, PKS-II, and NRPS genes and for antifungal activity. The results indicated that the antifungal metabolites of these bioactive strains might be products of these biosynthetic genes. Li et al. [4] and Qin et al. [7] had reported that number of isolates having antimicrobial property need not correlate with the percentage of isolates showing the presence of PKS and NRPS gene and vice versa. Strains HUST002, HUST009, HUST013, and HUST015 did not show any antifungal activity but they encoded at least one of these biosynthetic genes. Similarly strain HUST014 was absent for PKS or NRPS gene products but showed antifungal activity.

5. Conclusions

Relatively fewer studies have been done to explore the endophytic microbes associated with medicinal plant. This study showed that endophytic Actinobacteria associated with the medicinal plant D. cochinchinensis Lour. could be an alternate source for production of bioactive compounds that were previously obtained from the medicinal plant. It thereby provides a sustainable way of utilizing the medicinal plant without destroying the plant.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Project no. 2016M602566), Visiting Scholar Grant of State Key Laboratory of Biocontrol, Sun Yat-Sen University (Project no. SKLBC14F02), Vietnam Ministry of Education and Training (Project no. B2014-01-79), and Guangdong Province Higher Vocational Colleges & Schools Pearl River Scholar Funded Scheme (2014) for financial support for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Nimaichand Salam and Thi-Nhan Khieu contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Bérdy J. Thoughts and facts about antibiotics: where we are now and where we are heading. Journal of Antibiotics. 2012;65(8):385–395. doi: 10.1038/ja.2012.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodrigues Sacramento D., Rodrigues Coelho R. R., Wigg M. D., et al. Antimicrobial and antiviral activities of an actinomycete (Streptomyces sp.) isolated from a Brazilian tropical forest soil. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2004;20(3):225–229. doi: 10.1023/b:wibi.0000023824.20673.2f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee L.-H., Zainal N., Azman A.-S., et al. Diversity and antimicrobial activities of actinobacteria isolated from tropical mangrove sediments in Malaysia. The Scientific World Journal. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/698178.698178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li J., Zhao G.-Z., Chen H.-H., et al. Antitumour and antimicrobial activities of endophytic streptomycetes from pharmaceutical plants in rainforest. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 2008;47(6):574–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J., Zhao G.-Z., Qin S., Zhu W.-Y., Xu L.-H., Li W.-J. Streptomyces sedi sp. nov., isolated from surface-sterilized roots of Sedum sp. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 2009;59(6):1492–1496. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.007534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li J., Zhao G.-Z., Huang H.-Y., et al. Isolation and characterization of culturable endophytic actinobacteria associated with Artemisia annua L. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2012;101(3):515–527. doi: 10.1007/s10482-011-9661-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qin S., Li J., Chen H.-H., et al. Isolation, diversity, and antimicrobial activity of rare actinobacteria from medicinal plants of tropical rain forests in Xishuangbanna, China. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2009;75(19):6176–6186. doi: 10.1128/aem.01034-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qin S., Xing K., Jiang J.-H., Xu L.-H., Li W.-J. Biodiversity, bioactive natural products and biotechnological potential of plant-associated endophytic actinobacteria. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2011;89(3):457–473. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2923-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin S., Chen H.-H., Zhao G.-Z., et al. Abundant and diverse endophytic actinobacteria associated with medicinal plant Maytenus austroyunnanensis in Xishuangbanna tropical rainforest revealed by culture-dependent and culture-independent methods. Environmental Microbiology Reports. 2012;4(5):522–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2012.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khieu T.-N., Liu M.-J., Nimaichand S., et al. Characterization and evaluation of antimicrobial and cytotoxic effects of Streptomyces sp. HUST012 isolated from medicinal plant Dracaena cochinchinensis Lour. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2015;6, article 574 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang X.-H., Zhang C., Yang L.-L., Gomes-Laranjo J. Production of dragon's blood in Dracaena cochinchinensis plants by inoculation of Fusarium proliferatum. Plant Science. 2011;180(2):292–299. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta D., Bleakley B., Gupta R. K. Dragon's blood: botany, chemistry and therapeutic uses. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;115(3):361–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan L.-L., Tu P.-F., He J.-X., Chen H.-B., Cai S.-Q. Microscopical study of original plant of Chinese drug “Dragons Blood” Dracaena cochinchinensis and distribution and constituents detection of its resin. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 2008;33(10):1112–1117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li W.-J., Xu P., Schumann P., et al. Georgenia ruanii sp. nov., a novel actinobacterium isolated from forest soil in Yunnan (China), and emended description of the genus Georgenia. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 2007;57(7):1424–1428. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64749-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim O.-S., Cho Y.-J., Lee K., et al. Introducing EzTaxon-e: a prokaryotic 16s rRNA gene sequence database with phylotypes that represent uncultured species. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 2012;62(3):716–721. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.038075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Plewniak F., Jeanmougin F., Higgins D. G. The CLUSTAL X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Research. 1997;25(24):4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saitou N., Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 1987;4(4):406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimura M. The Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2013;30(12):2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39(4):783–791. doi: 10.2307/2408678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holder I. A., Boyce S. T. Agar well diffusion assay testing of bacterial susceptibility to various antimicrobials in concentrations non-toxic for human cells in culture. Burns. 1994;20(5):426–429. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(94)90035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trease G. E. A Textbook of Pharmacognosy. 14th. London, UK: Bailliere Tindall Ltd; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boost M. V., O'Donoghue M. M., James A. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus carriage among dogs and their owners. Epidemiology and Infection. 2008;136(7):953–964. doi: 10.1017/s0950268807009326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khamna S., Yokota A., Lumyong S. Actinomycetes isolated from medicinal plant rhizosphere soils: diversity and screening of antifungal compounds, indole-3-acetic acid and siderophore production. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2009;25(4):649–655. doi: 10.1007/s11274-008-9933-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monks A., Scudiero D., Skehan P., et al. Feasibility of a high-flux anticancer drug screen using a diverse panel of cultured human tumor cell lines. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1991;83(11):757–766. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.11.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shoemaker R. H., Scudiero D. A., Melillo G., et al. Application of high-throughput, molecular-targeted screening to anticancer drug discovery. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 2002;2(3):229–246. doi: 10.2174/1568026023394317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thao D. T., Phuong D. T., Hanh T. T. H., et al. Two new neoclerodane diterpenoids from Scutellaria barbata D. Don growing in Vietnam. Journal of Asian Natural Products Research. 2014;16(4):364–369. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2014.882912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huffman J., Gerber R., Du L. Review recent advancements in the biosynthetic mechanisms for polyketide-derived mycotoxins. Biopolymers. 2010;93(9):764–776. doi: 10.1002/bip.21483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kremer L. C. M., Van Dalen E. C., Offringa M., Ottenkamp J., Voûte P. A. Anthracycline-induced clinical heart failure in a cohort of 607 children: long-term follow-up study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2001;19(1):191–196. doi: 10.1200/jco.2001.19.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fischer C., Lipata F., Rohr J. The complete gene cluster of the antitumor agent gilvocarcin V and its implication for the biosynthesis of the gilvocarcins. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2003;125(26):7818–7819. doi: 10.1021/ja034781q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taechowisan T., Peberdy J. F., Lumyong S. Isolation of endophytic actinomycetes from selected plants and their antifungal activity. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2003;19(4):381–385. doi: 10.1023/A:1023901107182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verma V. C., Gond S. K., Kumar A., Mishra A., Kharwar R. N., Gange A. C. Endophytic actinomycetes from Azadirachta indica A. Juss.: isolation, diversity, and anti-microbial activity. Microbial Ecology. 2009;57(4):749–756. doi: 10.1007/s00248-008-9450-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Passari A. K., Mishra V. K., Saikia R., Gupta V. K., Singh B. P. Isolation, abundance and phylogenetic affiliation of endophytic actinomycetes associated with medicinal plants and screening for their in vitro antimicrobial biosynthetic potential. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2015;6, article 273 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao K., Penttinen P., Guan T., et al. The diversity and anti-microbial activity of endophytic actinomycetes isolated from medicinal plants in Panxi Plateau, China. Current Microbiology. 2011;62(1):182–190. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9685-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cui J.-L., Guo S.-X., Dong H., Xiao P. Endophytic fungi from Dragon's blood specimens: isolation, identification, phylogenetic diversity and bioactivity. Phytotherapy Research. 2011;25(8):1189–1195. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cao L., Qiu Z., You J., Tan H., Zhou S. Isolation and characterization of endophytic Streptomyces strains from surface-sterilized tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) roots. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 2004;39(5):425–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.2004.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gu Q., Luo H., Zheng W., Liu Z., Huang Y. Pseudonocardia oroxyli sp. nov., a novel actinomycete isolated from surface-sterilized Oroxylum indicum root. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 2006;56(9):2193–2197. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64385-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Castillo U. F., Browne L., Strobel G., et al. Biologically active endophytic streptomycetes from Nothofagus spp. and other plants in patagonia. Microbial Ecology. 2007;53(1):12–19. doi: 10.1007/s00248-006-9129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duangmal K., Thamchaipenet A., Ara I., Matsumoto A., Takahashi Y. Kineococcus gynurae sp. nov., isolated from a Thai medicinal plant. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 2008;58(10):2439–2442. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65671-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenblueth M., Martínez-Romero E. Bacterial endophytes and their interactions with hosts. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2006;19(8):827–837. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Compant S., Clément C., Sessitsch A. Plant growth-promoting bacteria in the rhizo- and endosphere of plants: their role, colonization, mechanisms involved and prospects for utilization. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2010;42(5):669–678. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.11.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rahman M. A., Islam M. Z., Khondkar P., Islam M. A. U. Characterization and antimicrobial activities of a polypeptide antibiotic isolated from a new strain of Streptomyces parvulus. Bangladesh Pharmaceutical Journal. 2010;13(1):14–17. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Usha R., Ananthaselvi P., Venil C. K., Palaniswamy M. Antimicrobial and antiangiogenesis activity of Streptomyces parvulus KUAP106 from mangrove soil. European Journal of Biological Sciences. 2010;2(4):77–83. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jemimah Naine S., Subathra Devi C., Mohanasrinivasan V., Vaishnavi B. Antimicrobial, antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of marine Streptomyces parvulus VITJS11 crude extract. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology. 2015;58(2):198–207. doi: 10.1590/s1516-8913201400173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu C., Shen Y. A novel ansamycin, naphthomycin K from Streptomyces sp. The Journal of Antibiotics. 2007;60(10):649–653. doi: 10.1038/ja.2007.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gontang E. A., Gaudêncio S. P., Fenical W., Jensen P. R. Sequence-based analysis of secondary-metabolite biosynthesis in marine actinobacteria. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2010;76(8):2487–2499. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02852-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rambabu V., Suba S., Manikandan P., Vijayakumar S. Cytotoxic and apoptotic nature of migrastatin, a secondary metabolite from Streptomyces evaluated on HepG2 cell line. International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2014;6(2):333–338. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim N., Shin J. C., Kim W., et al. Cytotoxic 6-alkylsalicylic acids from the endophytic Streptomyces laceyi. Journal of Antibiotics. 2006;59(12):797–800. doi: 10.1038/ja.2006.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Du L., Sánchez C., Chen M., Edwards D. J., Shen B. The biosynthetic gene cluster for the antitumor drug bleomycin from Streptomyces verticillus ATCC15003 supporting functional interactions between nonribosomal peptide synthetases and a polyketide synthase. Chemistry and Biology. 2000;7(8):623–642. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]