Abstract

Aims:

To find cytology changes among women attending obstetrics and gynaecology clinic with complaints of vaginal discharges.

Settings and Design:

This descriptive hospital-based cytological study was conducted at the outpatient clinic of the obstetrics and gynaecology department.

Materials and Methods:

Two hundred women with complaints of vaginal discharge were selected. Their detailed histories were documented on a special request form. Pap smears were then obtained and sent for cytological examination to the cytopathology department. All low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) cases were advised to follow-up with Pap smears in the next 6–12 months. Those with high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) were further investigated by a cervical biopsy and managed accordingly.

Statistical Analysis Used:

The statistical analysis was performed using, the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS). Chi-square and cross-tabulation were used in this study.

Results:

The cytological examination of Pap smears showed no changes (i.e. negative findings) in 88 (44%) cases, while Candida species infection was the most prevalent, which was found in 67 (33.5%) of the cases. Bacterial vaginosis was found in 39 women (19.5%); 6 women (3%) were reported with dyskaryotic changes. Two cases were found to have LSIL and 4 women had HSIL.

Conclusion:

Infection is common among the illiterate group of women. Women with vaginal discharges should undergo screening tests for evaluation by cervical smear for the early detection of cervical precancer conditions. There is an urgent need to establish a screening program for cervical cancer in Sudan.

Keywords: Cytology, Sudan, vaginal discharge

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer in the world among women, and is the leading cancer in women from developing countries.[1] Cervical infections are common problems among women of reproductive age and are associated with clinical complaints of vaginal discharge.[2,3] There are numerous risk factors for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer such as cervical infection[4,5] because abnormal vaginal flora can produce carcinogenic nitrosamines. Furthermore, bacterial vaginosis is similar, with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in epidemiologic features.[6] Bacterial vaginosis and vaginal discharge might have a role in the development of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. There have been several studies on this subject but with inconsistent results. Vaginal discharge is a very common gynecological symptom in Sudan. Pap smear is a screening test performed on cells from the uterine cervix.[7,8] The Pap test, introduced as a cervical screening test by George Papanicolaou, is a simple, quick, and painless procedure. To perform this test, a sample of cells is taken from in and around the cervix with a wooden scraper and placed on a glass slide, fixed in fixative, and sent to a laboratory for examination.[9] The objective of this study was to determine the frequency of different cytopathological conditions of the cervix in women with vaginal discharge; all the women included in the study attended the outpatient clinic operated by Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department. During the period from April 2010 to February 2011, 200 women were examined using Pap smear screening.

Patients and Methods

Study design

This was a descriptive hospital-based study conducted to determine the cytological changes among women complaining of vaginal discharge.

Study area

This study was conducted in the Red Sea State of Eastern Sudan at a Teaching Hospital's Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department together with the Histopathology and Cytology Department from April 2010 to February 2011.

Study population and sample size

Two hundred women attending the gynaecology clinic at a hospital agreed to participate in this study. Selection criteria were complaints of gynaecological symptoms, vaginal discharge, different tribes, and ages. Those with known long-standing pathology such as cancer or chronic inflammatory conditions were excluded from the study.

Sample collection and preparation

Specimen preparation was as follows. Cytological samples were taken by the consultant gynecologist by asking the patient to lie in the lithotomy position. The cervix was exposed by passing a speculum into the vagina. A cervical scrape was taken with Szalay Cyto-Spatula (Swiss Quality Szalay Cyto-Spatula Manufacturer, Swaziland). This was a modified plastic spatula with different sizes and shapes such that the correct spatula could be chosen. The tongue of the spatula was introduced into the endocervical canal, while its shoulder was positioned on 3 o’clock position of the ectocervix, and the spatula was rotated in a clockwise direction through 360°. The sample was smeared on a glass slide and immediately fixed in 95% ethanol for 15 minutes and then stained with a Papanicolaou stain, as described by George Papanicolaou in 1960. Smears were hydrated by using 90% alcohol for 2 minutes, 70% alcohol for 2 minutes, rinsed in water for 2 minutes, stained by Harris haematoxylin for 5 minutes, rinsed in water for 2 minutes, differentiated in 0.5% hydrochloric acid for 10 seconds, rinsed in water for 2 minutes, blued in tap water for 10 minutes, dehydrated in 70% alcohol for 2 minutes, treated with two changes of 95% alcohol for 2 minutes in each and stained by orange G.6 for 2 minutes, washed in 95% alcohol for 2 minutes, and finally, stained by EA50 for 2 minutes. Then, the smears were washed in 95% alcohol and dehydrated in absolute alcohol and cleared in xylene and mounted in DPX. Then, all the slides were screened by a cytotechnologist and results were confirmed by a cytopathologist.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using a software program, the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Chi-square and cross-tabulation were used in this study.

Results

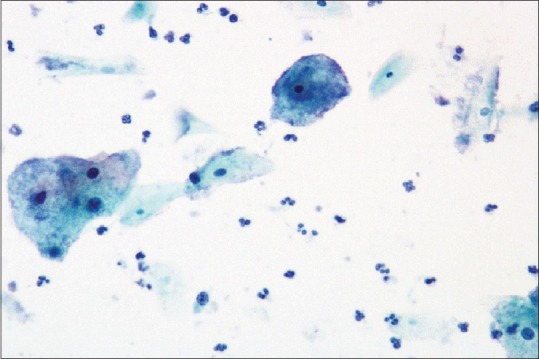

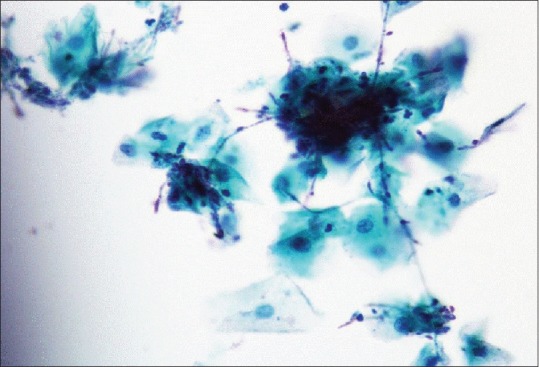

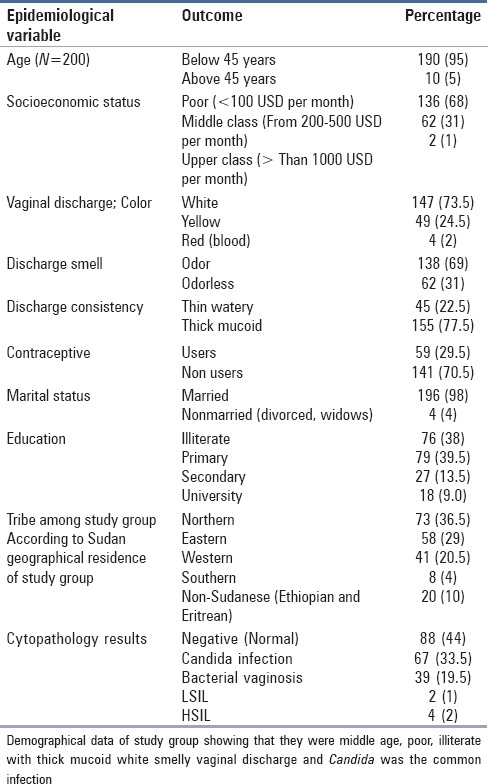

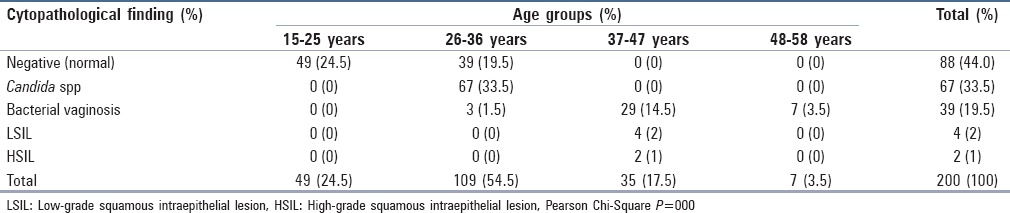

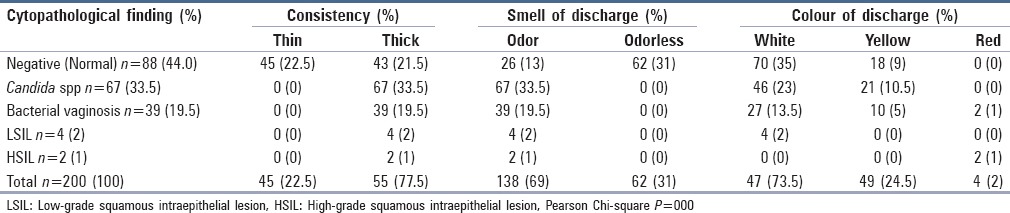

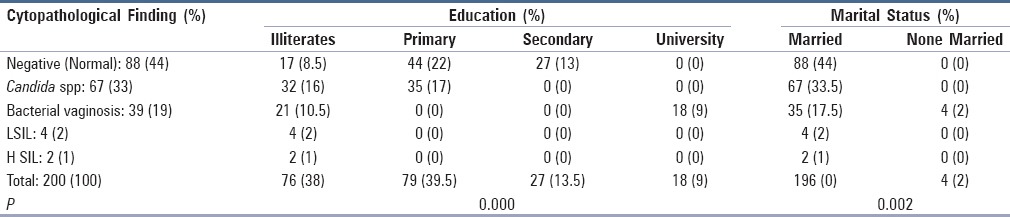

In the present study, a total of 200 cervical smears were studied. The age of participants ranged from 15 years to 58 years with the mean age being 30.62 years. Ten (5%) patients were of premenopausal age. All patients had complaints of vaginal discharge of variable colors (147/200 white, 49/200 yellow, and 4/200 red) and different consistency. The majority were mucoid and thick 155/200. One of the most common signs and symptoms, mentioned by 138 women (69%), was smelly odor. Sixty-two (31%) also complained of odorless vaginal discharge. Most patients (196 women, or 98%) were married; and 76 (38%) patients were illiterate. Only 18 (9%) had university education. One hundred and thirty-six (68%) patients were of low socioeconomic status. Seventy-three patients (36.5%) were from Sudanese tribes from northern Sudan, whereas 20 (10%) were not Sudanese (Ethiopian and Eritrean). The diagnosis of dyskerosis was given in 6 (3%) cases; 2 cases had LSIL and 4 had HSIL. Candida species [Figure 1] was the most prevalent infection found in 67 (33.5%) cases. Bacterial vaginosis [Figure 2] was found in 39 (19.5%) [Table 1]. Table 2 shows the age distribution of cytological changes among different age groups. All LSIL and HSIL cases occurred in the third decade (37–47 years). The cytomorphological features and their association with demographical data are given in detail in Tables 3 and 4.

Figure 1.

Bacterial vaginosis clue cells (Pap stain ×200)

Figure 2.

Candida infection (Pap stain ×100)

Table 1.

Patient data

Table 2.

Cytopathological finding and age groups

Table 3.

Discharge characteristics and cytopathological finding

Table 4.

Education, marital Status, and cytopathological finding

Discussion

All patients in our study presented to our clinic complaining of abnormal vaginal discharge. This corroborated with the findings of several international studies.[10,11,12,13] The prevalence of the clinically-diagnosed vaginal discharge, including all members of our study population, raises great concern regarding the underlying causes for this high rate. As 53% of our study population were found to have infections causing their discharges, the figure is considerably higher than the 14.5% reported by Patel et al,[14] however, similar to the 52% reported by Younis et al. in Egypt.[15] These differences could be due to the characteristics of these communities and study populations. The present study emphasized the significance of red-colored discharges and consistency and smells, as well as their association with abnormal cytopathological finding and bacterial vaginitis. Our results correspond with many previous studies.[16,17,18] The majority of our patients with abnormal cytopathological changes (including infectious LSIL and HSIL) were in the 37–47 years age group. Low-income women were found to be at high risk of developing cytopathological changes, which is attributable not only to the higher prevalence of risk factors in this population but also to the lack of regular health clinic visits. All the LSIL, HSIL, 25% of bacterial infection, and 24% of candidiasis were detected among low socioeconomic status, which was a commonly associated risk factor for cytopathological abnormalities and was seen in 136 (68%) women. This is comparable to the study conducted in California, which showed that low-income women were at higher risk of developing cervical cancer.[19,20] Awareness regarding the Pap test was very poor in our study population, especially among poor women because no women ever previously had a Pap test. The overall frequency of normal, dyskaryotic, and infective smears was 44%, 3%, and 53%, respectively. Most of the patients (54.5%) were of child-bearing age, with the mean age being 30.62 years. In the present study, of 6 positive cases, 2 women (1%) had LSIL, while 4 patients (2%) had HSIL. There were 67 (33.5%), 39 (19.5%), and 88 (44%) cases of Candida, bacterial vaginosis, and normal conditions, respectively. A study conducted by Roeters et al. (2010) supported our finding in that cytology is a valuable tool for the detection of cervical cytopathological abnormalities.[21] Furthermore, the study emphasizes the need for proper education of women of low socioeconomic class. Public health campaigns need to raise awareness regarding hazards and risk factors of cervical cancer as well as management and cure of the disease. There were 39 (19.5%) cases of bacterial vaginosis in our study. Marconi et al.[22] found in their study that 30.1% (23 women) had bacterial vaginosis. The prevalence of bacterial vaginosis in another study by Caixeta et al.[23] was 41.0% based on the conventional cervical smear method. This difference could be because of the different method used for detection of the condition. In addition, they screened only symptomatic women, and thus, were more likely to report positive results. Our frequency is also not consistent with the report of Barouti et al., who found a low frequency of these infections (17%) in their study.[24] To our knowledge, the current study is the only study in which Pap-stained cervical smears were used for the detection of bacterial vaginosis in the Red Sea State. However, PAP-stain analysis of vaginal smears for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis is likely to provide variable results, which are less reliable than those obtained by the microbiological method. The latter should be the first choice, and every effort should be made to set up this service in gynecological clinics. During the cytological examination of cervical smears, Candida species was found in 67 (33.5%) patients; these findings are consistent with studies that found a similar frequency of this organism at 30.10% which is close to our findings.[25] Our frequency is not consistent, however, with another study conducted in Sudan by Kafi et al.,[7] which reported only 10.1% frequency. This difference could be due to the method used for the detection of these organisms as Kafi et al. used direct microscopic examination of urine samples. Our frequency is also not consistent with Güdücü et al.,[25] who found a higher frequency of these parasites (43.3%) in their study. In our country, especially in the eastern region, people suffer from poverty. At the same time, they have unlimited access to antibiotics, including antifungal drugs, and use them at will. This may account for the wide variation in the presence of the organisms in the cervix among women in this study compared to other countries. The immune status, hygiene, level of education, and level of infection among patients may also have a profound influence on the ability of C. albicans to cause an infection in the cervix; we found a 33.5% incidence of C. albicans in the cervical smears of patients who presented with vaginal discharge. A limitation of the present study was the small sample. Other screening tests like visual inspection with acetic acid test (VIA) and human papilloma virus (HPV) DNA tests were not done. Until the time centrally-organized screening programs for cervical cancer are established in Sudan, arrangements should be made for hospital-based opportunistic screening for all women attending the hospital. The cost-effectiveness of various screening tests for cervical cancer should be evaluated.

Conclusion and Recommendation

This study concludes that the cytological examinations of cervical smears were helpful in the diagnosis of cervical infections. Moreover, it is clear that Candida, associated with bacterial vaginosis, is a major problem in our study group, especially in low socioeconomic patients. It is necessary to increase awareness among women regarding the vaginal discharge and consequences of cancer cervix, and particular attention should be given to appropriate education. Its time to establish cervical screening program in Sudan.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Haworth R, Margalit R, Ross C, Nepal T, Soliman A. Knowledge attitudes and practices for cervical cancer screening among the Bhutanese refugee community in Omaha Nebraska. J Community Health. 2014;39:872–8. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9906-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marconi C, Duarte M, Silva D, Silva M. Prevalence of and risk factors for bacterial vaginosis among women of reproductive age attending cervical screening in southeastern Brazil. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;131:137–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sivaranjini R, Jaisankar T, Thappa DM, Kumari R, Chandrasekhar L, Malathi, et al. Spectrum of vaginal discharge in a tertiary care setting. Trop Parasitol. 2013;3:135–9. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.122140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jahic M, Mulavdic M, Hadzimehmedovic A, Jahic E. Association between aerobic vaginitis, bacterial vaginosis and squamous intraepithelial lesion of low grade. Med Arch. 2013;67:94–6. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2013.67.94-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Junior J, Giraldo P, Gonüalves A, Amaral R, Linhares I. Uterine cervical ectopy during reproductive age: Cytological and microbiological findings. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42:401–4. doi: 10.1002/dc.23053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyle D, Barton S, Uthayakumar S, Hay PE, Pollock JW, Steer, et al. Is bacterial vaginosis associated with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003;13:159–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2003.13007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kafi S, Mohamed A, Musa H. Prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases (STD) among women in a suburban Sudanese community. Ups J Med Sci. 2000;105:249–53. doi: 10.3109/2000-1967-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lojindarat S, Luengmettakul J, Puangsa S. Clinical significance of atypical glandular cells in cervical Papanicolaou smears. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95:975–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khattak S, Khattak I, Naheed T, Akhtar S, Jamal T. Detection of abnormal cervical cytology by pap smears. Gomal J Med Sci. 2006;4:747–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yasmin S, Mukherjee A. A cyto-epidemiological study on married women in reproductive age group (15-49 years) regarding reproductive tract infection in a rural community of West Bengal. Indian J Public Health. 2012;56:204–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.104233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dasgupta A, Sarkar M. A study on reproductive tract infections among married women in the reproductive age group (15-45 years) in a slum of Kolkata. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2008;58:518–22. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samanta A, Ghosh S, Mukherjee S. Prevalence and health seeking behavior of reproductive tract infection/sexually transmitted infection symptomatics: A cross sectional study of a rural community in the Hooghly district of West Bengal. Indian J Public Health. 2011;55:38–41. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.82547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma P, Rahi M, Lal P. A community-based cervical cancer screening program among women of Delhi using camp approach. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:86–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.62576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel V, Pednekar S, Weiss H, Rodrigues M, Barros P, Nayak, et al. Why do women complain of vaginal discharge? A population survey of infectious and pyschosocial risk factors in a South Asian community. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:853–62. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Younis N, Khattab H, Zurayk H, Elmouelhy M, Amin M. A community study of gynecological and related morbidities in rural Egypt. Stud Fam Plann. 1993;24:175–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pradhan N, Giri K, Rana A. Cervical cytology study in unhealthy and healthy looking cervix. N J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;2:42–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kenneth D, Yao S. Novak's Gynecology. 13th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002. Cervical and vaginal cancer; pp. 471–93. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coker A, Eggleston K, Meyer T, Luchok K, Das I. What predicts adherence to follow-up recommendations for abnormal Pap tests among older women.? Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engelstad L, Stewart S, Nguyen B, Bedeian K, Rubin M, Pasick, et al. Abnormal Pap smear follow-up in a high-risk population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:1015–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roeters A, Boon ME, van Haaften M, Vernooij F, Bontekoe TR, Heintz AP. Inflammatory events as detected in cervical smears and squamous intraepithelial lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010;38:85–93. doi: 10.1002/dc.21169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marconi C, Marli T, Daniela D, Silva C, Márcia G. Silva Prevalence of and risk factors for bacterial vaginosis among women of reproductive age attending cervical screening in Southeastern Brazil. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;38:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caixeta R, Ribeiro A, Segatti K, Saddi V, Figueiredo A, Carneiro, et al. Association between the human papillomavirus, bacterial vaginosis and cervicitis and the detection of abnormalities in cervical smears from teenage girls and young women. Diagn Cytopathol. 2015;38:14–18. doi: 10.1002/dc.23301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barouti E, Farzaneh F, Sene A, Tajik Z, Jafari B. The pathogenic microorganisms in papanicolaou vaginal smears and correlation with inflammation. J Family Reprod Health. 2013;7:23–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Og A, Oe O, To A. Sensitivity of a Papanicolaou smear in the diagnosis of candida albicans infection of the cervix. N Am J Med Sci. 2010;2:97–9. doi: 10.4297/najms.2010.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Güdücü N, Gönenç G, Işçi H, Yiğiter A, Başsüllü N, Dünder I. Clinical importance of detection of bacterial vaginosis, trichomonas vaginalis, candida albicans and actinomyces in Papanicolaou smears. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39:333–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]