A Boston Globe exposé published in October 2015 put a spotlight on the practice of concurrent surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital.1 In this report and a related editorial, journalists focused on revenue generation, while implicating financial considerations as the primary motivator for surgeons running multiple operating rooms simultaneously.2 The articles ignored the role of adequately skilled and appropriately supervised physicians-in-training during these procedures. Although financial considerations are relevant, the journalists failed to recognize a reality of the health care training system and an essential element of pedagogy in medical education—trainee responsibility for patient care.

Trainee Involvement in Patient Care

Training physicians who are capable of safe, unsupervised practice is a primary goal of our medical education system.3 To reach this goal, physicians-in-training must be given “graded and progressive” responsibility in evaluating and treating patients.4 Although some aspects of medicine can be learned from a textbook or a simulator, many lessons require direct interaction with patients. As a result, every physician has an innumerable list of “first time” patient care experiences, from taking a medical history to performing complex procedures. Increasing autonomy is essential in this developmental process. Medical education depends on progressive responsibility and conditional independence to ensure that trainees mature from observer to assistant to supervising physician.

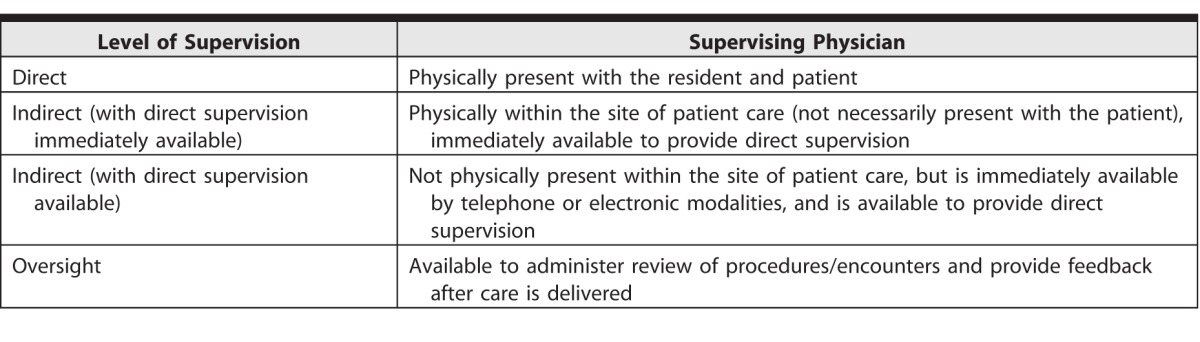

Ultimately, no amount of experience as an assistant can provide the insight or expertise that comes from being the primary medical decision maker or proceduralist. However, this reality often is ignored because it is disquieting and potentially objectionable. Fortunately, the need for learning through clinical experiences is balanced by graduated levels of supervision defined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), shown in the table.4 An appropriate level of supervision allows trainees to function safely as both learner and clinician—a duality that is essential in medical education.

Table.

Levels of Supervision Defined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education4

The integration of patient care and medical education involves pragmatic and ethical considerations, including professional duty, nonmaleficence, beneficence, justice, veracity, and autonomy.5 Principally, physicians serve patients' best interests (beneficence) while posing the least risk of harm (nonmaleficence).6 At the same time, training competent physicians, who have had experience being directly responsible for patient care, remains an essential professional responsibility. Accordingly, there is an apparent conflict of medical ethics and education: a patient should be cared for by the most capable physician (usually not a trainee), yet trainees need to be responsible for patient care.

This inconsistency is mitigated by the dual role of attending physicians, who not only teach but also supervise and manage clinical care.3 Health care in teaching institutions is delivered by both the trainee and the supervisor. As trainees progressively gain competencies, they are allowed to practice more broadly and with less direct supervision, but not without any supervision.7 This developmental process has been formalized by the ACGME through the Milestone Project (outcomes-based evaluations), entrustable professional activities, and supervision scales.8–10 Through these processes, trainees learn when to ask for assistance as they develop toward the goal of unsupervised medical practice.

Public Perception

The public comments to the Boston Globe article suggest that many patients may not consent to trainees having a substantial role in their procedures, even if these roles represent the long-time “industry standard” in teaching hospitals across the United States. This reaction may be a function of the scenario presented; that is, members of the public are reacting to the journalistic portrayal of profit seeking combined with an unfortunate surgical complication, rather than focusing on education and safe, supervised care. Surely patients would understand that adhering to a strict “assistant” role would result in physicians-in-training entering practice unprepared, having never functioned autonomously. Unfortunately, this trend toward inexperience may already be reflected in the growing number of graduates entering fellowship, and in reports that new physicians are less skilled than those in prior generations.11–13

Veracity is essential to maintain public trust in the judgment of supervising physicians, who determine when trainees are competent to function with conditional independence.10 Some patients may be uncomfortable with trainee involvement in their care, but physicians should always fully disclose the roles of all members of the health care team. Without some difficult conversations, patients may not understand the evolution of physicians-in-training and the need for graduated autonomy. This dialogue also provides an opportunity to improve informed consent and shared decision making. Uninformed patients are rightfully surprised and angry when they learn that elements of their procedure were not performed by their surgeon. Much of the bad press in Boston could have been mitigated by clearly defining the role of trainees as part of the process of informed consent. Patients should meet trainees, know their experience, and expect full disclosure of their involvement.

Patients can remain autonomous in their decisions about trainee involvement in their clinical care, if they are informed. In the teaching setting, respect for individual agency involves transparency and accountability for trainees under an attending physician's supervision. Justice dictates that we offer all patients the same level of care, regardless of any discriminating factors. If they find the trainees' roles objectionable, patients may reject trainee involvement in their care by choosing another physician who does not work with trainees. However, it is unlikely that patients will turn away from teaching institutions, which are often recognized for renowned faculty and cutting-edge medical expertise. Teaching hospitals necessarily involve trainees in patient care, and it is not reasonable to expect changes in this model. Limiting the involvement of trainees would surely be detrimental to education and potentially dangerous to future patients by creating a generation of inexperienced physicians.

The medical profession should engage the public in a conversation about how medical education integrates with health care delivery. As suggested in the conclusion of the Boston Globe exposé, openly discussing the realities of trainee involvement, faculty supervision, and progressive responsibility in teaching institutions will avoid the appearance of concealment and profit mongering.2 Meanwhile, journalists who sensationalize a common practice at academic institutions (whether due to ignorance or to exaggeration) lack professionalism, as their writing may only confuse and anger patients. Full disclosure of our practices, and respectful and socially responsible reporting of trainee involvement in teaching settings, will serve to inform and align patient expectations with the teaching community's goals of providing excellent care while training tomorrow's physicians.

References

- 1. Abelson J, Saltzman J, Kowalczyk L, et al. Clash in the name of care. The Boston Globe. October 25, 2015. https://apps.bostonglobe.com/spotlight/clash-in-the-name-of-care/story/. Accessed December 20, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vennochi J. . With double-booked surgeries, the patient has a right to know. The Boston Globe. October 26, 2015. https://www.bostonglobe.com/opinion/2015/10/26/with-double-booked-surgeries-patient-has-right-know/YFOTniVrFDa9pKld1DczMI/story.html. Accessed December 20, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schumacher DJ, Bria C, Frohna JG. . The quest toward unsupervised practice: promoting autonomy, not independence. JAMA. 2013; 310 24: 2613– 2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements. July 1, 2016. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_07012016.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gillon R. . Medical ethics: four principles plus attention to scope. BMJ. 1994; 309 6948: 184– 188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gifford RW., Jr. Primum non nocere. JAMA. 1977; 238 7: 589– 590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carraccio C, Wolfsthal SD, Englander R, et al. Shifting paradigms: from Flexner to competencies. Acad Med. 2002; 77 5: 361– 367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. ten Cate O. . Nuts and bolts of entrustable professional activities. J Grad Med Educ. 2013; 5 1: 157– 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Englander R, Carraccio C. . From theory to practice: making entrustable professional activities come to life in the context of milestones. Acad Med. 2014; 89 10: 1321– 1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sterkenburg A, Barach P, Kalkman C, et al. When do supervising physicians decide to entrust residents with unsupervised tasks? Acad Med. 2010; 85 9: 1408– 1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mattar SG, Alseidi AA, Jones DB, et al. General surgery residency inadequately prepares trainees for fellowship: results of a survey of fellowship program directors. Ann Surg. 2013; 258 3: 440– 449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Coleman JJ, Esposito TJ, Rozycki GS, et al. Early subspecialization and perceived competence in surgical training: are residents ready? J Am Coll Surg. 2013; 216 4: 764– 771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Napolitano LM, Savarise M, Paramo JC, et al. Are general surgery residents ready to practice? A survey of the American College of Surgeons Board of Governors and Young Fellows Association. J Am Coll Surg. 2014; 218 5: 1063– 1072.e31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]