Abstract

Background

Physician burnout is common and associated with significant consequences for physicians and patients. One mechanism to combat burnout is to enhance meaning in work.

Objective

To provide a trainee perspective on how meaning in work can be enhanced in the clinical learning environment through individual, program, and institutional efforts.

Methods

“Back to Bedside” resulted from an appreciative inquiry exercise by 37 resident and fellow members of the ACGME's Council of Review Committee Residents (CRCR), which was guided by the memoir When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi. The exercise was designed to (1) discover current best practices in existing learning environments; (2) dream of ideal ways to enhance meaning in work; (3) design solutions that move toward this optimal environment; and (4) support trainees in operationalizing innovative solutions.

Results

Back to Bedside consists of 5 themes for how the learning environment can enhance meaning in daily work: (1) more time at the bedside, engaged in direct patient care, dialogue with patients and families, and bedside clinical teaching; (2) a shared sense of teamwork and respect among multidisciplinary health professionals and trainees; (3) decreasing the time spent on nonclinical and administrative responsibilities; (4) a supportive, collegial work environment; and (5) a learning environment conducive to developing clinical mastery and progressive autonomy. Participants identified actions to achieve these goals.

Conclusions

A national, multispecialty group of trainees developed actionable recommendations for how clinical learning environments can be improved to combat physician burnout by fostering meaning in work. These improvements can be championed by trainees.

But in residency, something else was gradually unfolding. In the midst of this endless barrage of head injuries, I began to suspect that being so close to the fiery light of such moments only blinded me to their nature, like trying to learn astronomy by staring directly at the sun. I was not yet with patients in their pivotal moments, I was merely at those pivotal moments. I observed a lot of suffering; worse, I became inured to it. Drowning, even in blood, one adapts, learns to float, to swim, even to enjoy life, bonding with the nurses, doctors, and others who are clinging to the same raft, caught in the same tide.

—Paul Kalanithi, When Breath Becomes Air1

Introduction

Physician burnout is characterized by a constellation of symptoms that includes losing enthusiasm for work, feeling detached from patients, and having a sense that work is no longer meaningful.2 Growing awareness of physician burnout by the medical community and the general public is reflected in the number of articles published on the topic in medical literature, and in publications such as US News & World Report3 and The New York Times.4 Burnout has been linked to severe consequences for both the patient and the physician, including reduced quality of care, an increased likelihood of making medical errors,5,6 and increased odds for physician depression and suicidal ideation.7

Physician burnout is common; in some studies nearly 60% of physicians or physicians in training meet burnout criteria.8,9 Burnout is prevalent during all stages of a physician's career, and can take effect as early as medical school.10 Residents have been shown to be particularly at risk for developing burnout,9 which has been linked to a variety of factors, including excessive workload, lack of autonomy, increased administrative duties, perceived lack of mentors, and lack of control over their work schedule.11 One promising strategy to mitigate physician burnout is to foster meaning and joy in work through systematic changes in the clinical learning environment.5,12,13

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Council of Review Committee Residents (CRCR), which encompasses the resident and fellow members of all Review Committees, met in May 2016 to discuss the importance of enhancing meaning in trainee work. This group is geographically, culturally, and gender diverse, with representatives from medical, surgical, and hospital-based specialties. We used a modified appreciative inquiry14 approach with a premeeting literary stimulus to identify how meaning in work is nurtured through the clinical learning environment at the level of the individual, program, institution, CRCR, and ACGME.

Methods

Thirty-seven residents (19 medical, 14 surgical, 4 hospital-based specialties) participated in the appreciative inquiry exercise to explore how to enhance meaning in trainee work. Members gave verbal consent to have data from the session included in this article. Appreciative inquiry has been previously used by this group,15 and was chosen for its focus on building upon the best available current resources while avoiding a focus on the negative.14 The general steps of appreciative inquiry are to (1) discover the “best of what is”; (2) dream about “what might be”; then (3) design “what can be”; and (4) develop a path toward the destiny of “what should be.”14

Prior to the meeting, members were asked to read the memoir When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi.1 The book was used as a starting point for the “discovery” portion of the exercise. Trainees were assigned to triads, and asked to interview each other using the appreciative inquiry prompts.

Following an in-depth exploration of the information from the discovery portion, each triad was then assigned to 1 of 4 small groups for the rest of the exercise. The groups followed the other steps of the appreciative inquiry process with a facilitator. The questions used for this portion of the exercise are provided as online supplemental material. At the conclusion of the exercise, participants convened in a large group for a report-out session that highlighted each small group's “destiny” findings. Each trainee was then given 5 votes from which to help prioritize these items that represent potential actionable ideas.

After the initial CRCR meeting, the ideas resulting from the appreciative inquiry exercise were analyzed for common themes. The 4 members of the writing team (D.M.H., K.L.R., K.N., D.A.J.) independently reviewed and categorized the ideas by broad themes.

Results

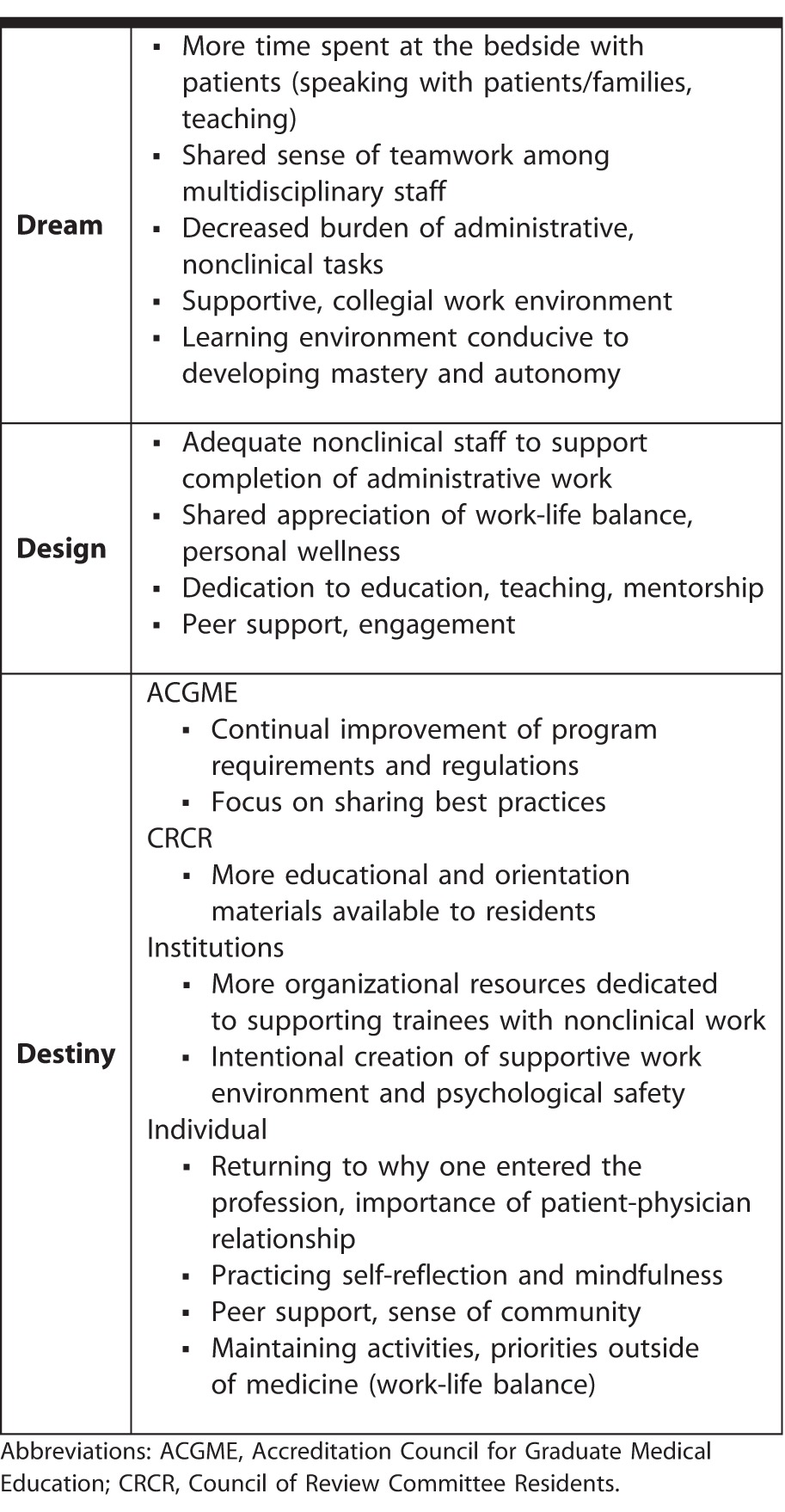

The individual reflection and group discussion generated through reading When Breath Becomes Air provided rich content and great enthusiasm for all CRCR members involved. Qualitative analysis of the broad consensus themes generated by the study questions are presented in the table.

Table.

Consensus Themes of Specific Recommendations

When asked to describe the ideal learning environment that enhances meaning in daily work, 5 themes emerged: (1) more time spent at the bedside with patients, with more engagement in direct care, dialogue with patients and families, and bedside clinical teaching; (2) a shared sense of teamwork and respect among multidisciplinary health care professionals and trainees; (3) reduced time spent on nonclinical or administrative responsibilities; (4) a supportive, collegial work environment; and (5) a learning environment conducive to developing clinical mastery and progressive autonomy.

From the weighted voting exercise, a single predominant theme emerged: finding innovative methods to free up residents to have more time to engage directly in meaningful contact with patients, which became a term that was shortened to “Back to Bedside.” The results of the exercise are shown in the box. In working toward this “dream” learning environment, the following design and systems principles were identified as important by CRCR members during the design and destiny portions of the exercise: (1) adequate nonclinical and support staff to support timely completion of administrative or nonclinical tasks; (2) a shared appreciation and commitment to supporting trainee personal balance and wellness; (3) dedication of time and resources toward activities to enhance medical education, clinical teaching, and mentorship of trainees; and (4) a culture of peer support, community, and engagement. The general consensus among participants was that all trainees and health professionals should be consciously dedicated to supporting these design principles, and that while many programs and institutions excel in some aspects, much work remains to be done to design systems that universally and avidly pursue all of these aims.

Box Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Actionable Items With Votes per Item

What can the ACGME do?

Share best practices (13 votes)

Develop program and/or institutional requirements to assess well-being (23 votes)

Develop requirements for mental health coverage (25 votes)

Remove barriers, free/accessible mental health services (10 votes)

“Back to Bedside” (45 votes)

Prioritize honesty on surveys (1 vote)

Foster accountability for program coordinators (12 votes)

More time with patients (enforce ACGME Program Requirements section II.C) (39 votes)

To achieve this ideal learning environment, participants identified 3 actionable themes:

First, adequate organizational resources need to be allocated at the institutional level to support trainees and health care professionals facing an increasing burden of administrative and nonclinical tasks. These tasks too often drive health professionals away from the bedside.

Second, ensuring a supportive working and learning environment is critical to high-quality, safe, and effective patient care, and is optimal for resident learning and professional development. At a national level, the ACGME plays an important role in fostering continuous improvement in the learning environment through the ongoing updates of program requirements, sharing of best practices, and the Clinical Learning Environment Review.16 The CRCR plays an important role in advocating for residents and providing residents with reliable, accessible information about graduate medical education.

Third, individual trainees should be engaged in this work through practicing self-reflection and mindfulness in accordance with their values and background, and in the context of their specialty, institution, and community.

Discussion

Reflecting on the current state of graduate medical education, several national efforts are underway to develop strategies to reduce physician burnout during training years. The ACGME has spearheaded several programs directly or indirectly aimed at reducing resident burnout, such as the Symposium on Physician Well-Being.17 Other organizations have also addressed physician well-being, including the Institute for Healthcare Improvement,18 the STEPS Forward program through the American Medical Association,19 and the Association of American Medical Colleges 2016 Leadership Forum.20 Although these programs have encouraged awareness of burnout and the development of strategies to reduce fatigue of physicians in training, more work is needed in this area.

Leveraging the use of internal motivators is a particularly promising approach for combating burnout in several workplaces, including the clinical arena. Studies show that internal motivators are more powerful and effective than external motivators used in traditional “carrot and stick” models. In Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, Daniel H. Pink21 describes 3 proven internal motivators that drive individuals to succeed at complex tasks: (1) a sense of mastery or the potential to attain mastery; (2) autonomy; and (3) a sense of purpose or meaning to what they are doing. Presently, few initiatives exist in graduate medical education that specifically emphasize enhancing meaning in work; accordingly, this was chosen as the primary area for intervention by our group.

The relationship between meaning in work and burnout has been studied in several medical specialties, including medicine, surgery, and primary care, with findings suggesting that enhancing meaning in work significantly reduces burnout.12,22,23 Provision of patient care is 1 way physicians find meaning in work. However, internal and external pressures have increasingly created barriers that limit direct interaction with patients. Time-motion studies have shown current requirements result in a 2:1 ratio of time spent on documentation compared to direct patient care, with only approximately 10% of physician time spent actually providing care to patients.24 A more recent study showed that the ratio of documentation to direct patient care may be as high as 5:1.25

The ideal environment for finding meaning in work appears to conflict directly with the existing environment. Physicians in training and in practice are being pulled away from caring for patients to deal with increasing administrative and nonclinical obligations. This was captured in the discussions of our diverse panel, as residents and fellows believed the most efficacious way to increase meaning in their work would be to have more time in direct patient care. Furthermore, we identified the best place to influence change was at the level of the institution and the individual, as opposed to the national (ie, ACGME) level. Finally, we believe that the best agents for driving this change could be residents and fellows—the individuals on the front lines with direct understanding of the unique barriers to spending meaningful time with their patients.

From these discussions, we created the Back to Bedside initiative to empower residents and fellows to develop transformative projects to combat burnout by fostering meaning in work within their learning environments. Supported by the ACGME, this initiative will include a competitive funding opportunity for residents and fellows to innovate within the 5 areas identified by the CRCR for enhancing meaning in work. Funded research teams will form a learning collaborative to allow exchange of ideas, identification of barriers to success, and discussion of strategies for broad national dissemination of successful projects. The goal of this initiative is to allow those closest to the problem to develop and test future solutions.

Conclusion

With an increasing national emphasis on physician well-being, and a focus on identifying ways to combat physician burnout, a multispecialty, nationally representative group of fellows and residents identified 5 key areas that define the ideal learning environment for enhancing meaning in work. From this work, the ACGME is developing a national initiative to provide resources to empower residents and fellows to be agents of change to improve their clinical learning environments, and return a sense of meaning into their daily work.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Kalanithi P. . When Breath Becomes Air. New York, NY: Random House; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Hoogduin K, et al. . On the clinical validity of the Maslach burnout inventory and the burnout measure. Psychol Health. 2001; 16 5: 565– 582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sternberg S. . Diagnosis: burnout. US News & World Report. September 8, 2016. http://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2016-09-08/doctors-battle-burnout-to-save-themselves-and-their-patients. Accessed February 22, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wachter RM. . How meansurement fails teachers and doctors. The New York Times. January 16, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/17/opinion/sunday/how-measurement-fails-doctors-and-teachers.html?_r=0. Accessed February 22, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5. West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, et al. . Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy: a prospective longitudinal study. JAMA. 2006; 296 9: 1071– 1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA. . Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator. Lancet. 2009; 374 9702: 1714– 1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Dyrbye L, et al. . Special report: suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2011; 146 1: 54– 62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. . Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015; 90 12: 1600– 1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. . Burnout among US medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general US population. Acad Med. 2014; 89 3: 443– 451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. . Burnout and suicidal ideation among US medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008; 149 5: 334– 341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T. . A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Med Educ. 2016; 50 1: 132– 149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shanafelt TD. . Enhancing meaning in work: a prescription for preventing physician burnout and promoting patient-centered care. JAMA. 2009; 302 12: 1338– 1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, et al. . Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016; 388 10057: 2272– 2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bushe G. . Foundations of appreciative inquiry: history, criticism and potential. AI Practitioner. 2012; 14 1: 8– 20. http://www.gervasebushe.ca/Foundations_AI.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Daskivich TJ, Jardine DA, Tseng J, et al. . Promotion of wellness and mental health awareness among physicians in training: perspective of a national, multispecialty panel of residents and fellows. J Grad Med Educ. 2015; 7 1: 143– 147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bagian JP, Weiss KB; . CLER Evaluation Committee. The overarching themes from the CLER National Report of Findings 2016. J Grad Med Educ. 2016; 8 2 suppl 1: 21– 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Physician well-being. http://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Initiatives/Physician-Well-Being. Accessed February 22, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Joy in work. http://www.ihi.org/Topics/Joy-In-Work/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed February 22, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Linzer M, Guzman-Corrales L, Poplau S. AMA STEPS. Forward. Preventing physician burnout. https://www.stepsforward.org/modules/physician-burnout. Accessed February 22, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Association of American Medical Colleges. Well-being in academic medicine. https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/462280/wellbeingacademicmedicine.html. Accessed February 22, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pink DH. . Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. New York, NY: Riverhead Books; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sloan JA, et al. . Career fit and burnout among academic faculty. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169 10: 990– 995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. . Avoiding burnout: the personal health habits and wellness practices of US surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012; 255 4: 625– 633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mamykina L, Vawdrey DK, Hripcsak G. . How do residents spend their shift time? A time and motion study with a particular focus on the use of computers. Acad Med. 2016; 91 6: 827– 832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wenger N, Méan M, Castioni J, et al. . Allocation of internal medicine resident time in a Swiss hospital: a time and motion study of day and evening shifts. Ann Intern Med. Jan 31, 2017. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.