Abstract

Erikson’s (1950) model of adult psychosocial development outlines the significance of successful involvement within one’s relationships, work, and community for healthy aging. He theorized that the consequences of not meeting developmental challenges included stagnation and emotional despair. Drawing on this model, the present study uses prospective longitudinal data to examine how the quality of assessed Eriksonian psychosocial development in midlife relates to late-life cognitive and emotional functioning. In particular we were interested to see whether late-life depression mediated the relationship between Eriksonian development and specific domains of cognitive functioning (i.e., executive functioning and memory).

Participants were 159 men from the over 75 year longitudinal Study of Adult Development. The sample was comprised of men from both higher and lower socio-economic strata. Eriksonian psychosocial development was coded from men’s narrative responses to interviews between the ages of 30–47 (Vaillant and Milofsky, 1980). In late life (ages 75–85) men completed a performance - based neuropsychological assessment measuring global cognitive status, executive functioning, and memory. In addition depressive symptomatology was assessed using the Geriatric Depression Scale.

Our results indicated that higher midlife Eriksonian psychosocial development was associated with stronger global cognitive functioning and executive functioning, and lower levels of depression three to four decades later. There was no significant association between Eriksonian development and late-life memory. Late-life depression mediated the relationship between Eriksonian development and both global cognition and executive functioning. All of these results controlled for highest level of education and adolescent intelligence.

Findings have important implications for understanding the lasting benefits of psychosocial engagement in mid-adulthood for late-life cognitive and emotional health. In addition, it may be that less successful psychosocial development increases levels of depression making individuals more vulnerable to specific areas of cognitive decline.

Keywords: Erikson Model, Psychosocial Development, Adult Development, Aging, Cognition, Neuropsychology, Executive Functioning, Memory, Late-life Depression, Longitudinal

Introduction

Erikson’s (1950, 1968) model of psychosocial development is routinely utilized as a foundational framework for understanding adult human development across the lifespan (Busch & Hofer, 2012; Schoklitsch & Baumann, 2012; Slater, 2003; Sneed, Whitbourne, Schwartz, & Huang, 2012; Vaillant, 1993, 2012; Westermeyer, 2004; Whitbourne, Sneed, & Sayer, 2009; Wilt, Cox, & McAdams, 2010). Consistent with this model, a growing body of empirical research indicates that relationships, work, and the identity one forms in psychosocial contexts have important implications for healthy aging (Cohen, 2004; Everard, Lach, Fisher, & Baum, 2000; Sato et al., 2008; Thomas, 2011). However, there is surprisingly little research examining how Erikson’s developmental framework links with cognitive and psychological functioning as people age.

Erikson (1950) proposed that individuals navigate a series of psychosocial developmental tasks from infancy to death (see Table 1). In his book Childhood and Society, he outlined a series of primary tasks in adult life: forming intimate relationships, experiencing generativity (i.e., being productive and committed to guiding younger generations), and finally experiencing “ego integrity” (i.e., coming to terms with the past and future in the face of upcoming death) with wisdom in the culmination of one’s life (Erikson, 1950). Those who have difficulty meeting these developmental challenges were thought by Erikson to be more vulnerable to emotional distress (e.g., depression or despair) and stagnation (e.g., lack of creativity and productivity) as they aged.

Table 1.

Eriksonian Psychosocial Development

| Approximate Developmental Phase | Erikson’s (1950) Developmental Crises | Vaillant (1980, 2012) Developmental Tasks | Description of Developmental Task From Erikson (1950) | Vaillant’s (1980, 2012) operationalization of Adult Developmental tasks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | Infancy | Trust vs. Mistrust | Basic Trust | Ability to rely on the continuity of caregivers and ultimately the self | |

| Stage 2 | Early Childhood | Autonomy vs. Shame & Doubt | Autonomy | Development of increased independence and ability for “free choice” | |

| Stage 3 | Play Age | Initiative vs. Guilt | Initiative | Ability to approach what one desires with increased accuracy, planning, and energy | |

| Stage 4 | School Age (Latency) | Industry vs. Inferiority | Industry | Learning to work, be productive, and be a potential provider | |

| Stage 5 | Adolescence | Identity vs. Role Confusion | Identity | The development of a new sense of “continuity and sameness” in one’s own eyes while being aware of the being in the “eyes of others” | “to live independently of family and to be self-supporting” (Vaillant, 2012, p. 150) |

| Stage 6 | Young Adulthood | Intimacy vs. Isolation | Intimacy | The ability to commit to others in partnership and maintain this even at the cost of compromise and sacrifice | “the capacity to live with another person in an emotionally attached, interdependent and committed relationship for 10 or more years” (p. 151) |

| Stage 6a | Middle Adulthood | Career Consolidation | Developing a “career” characterized by commitment, compensation, contentment, and competence | ||

| Stage 7 | Generativity vs. Stagnation | Generativity | Concern for establishing and guiding the next generation | Concern for establishing and guiding the next generation | |

| Stage 7a | Old Age | Keepers of the Meaning or Guardianship | Concern and active commitment for preserving values that benefit culture as a whole | ||

| Stage 8 | Ego Integrity vs. Despair | Integrity | The acceptance and emotional integration regarding one’s own life, the human life-cycle, and a place in one’s culture/history | “The capacity to come to terms constructively with our pasts and futures in the face of inevitable death” (p. 157). |

In the present study, we utilized data from an over 75-year prospective longitudinal study of adult men to determine whether midlife Eriksonian psychosocial development was associated with late-life emotional wellbeing and cognitive functioning after controlling for intelligence (assessed in adolescence upon entry into the study) and highest level of education. We hypothesized that individuals classified as having more successfully navigated through the psychosocial challenges outlined by Erikson in midlife would manifest better psychological and cognitive health in their seventies and eighties. Based on Erikson’s (1950) idea that failure to successfully negotiate these developmental tasks hinders emotional wellbeing, we proposed a mediation model to assess whether the relationship between midlife Eriksonian developmental stage and late-life neuropsychological functioning would be accounted for by the presence of late-life depression. Specifically, individuals who had not mastered developmental tasks related to having meaningful experiences in their work and relationships would be vulnerable to depression, which in turn would account for greater neuropsychological difficulties. Or said in reverse, adaptive paths of life development would be tied to better neuropsychological functioning, in part due to lower levels of depression.

In this work we aim to better understand the ways in which mid-adult psychosocial antecedents contribute to cognitive decline and depression in later life. This research has important implications given that a growing body of literature suggests that depression impacts multiple domains of neuropsychological functioning (Clark, Chamberlain, & Sahakian, 2009; Dotson, Resnick, & Zonderman, 2008; Reischies & Neu, 2000).

Erikson’s Model

Erikson’s model is based on assessment of individuals’ observable adaptive functioning as they meet the evolving challenges or crises of life from infancy to old age. (See Table 1 for an overview). He describes his work as an epigenetic model comprised of levels on a developmental ladder in which each stage lays the foundation for the next in a vertical across the lifespan (Erikson, 1984; Erikson & Erikson, 1998). Over the last 50 years, Erikson’s original conceptualization of stages of development tied to specific ages has been modified such that development is now seen more as a series of developmental challenges that one engages with and revisits across the adult lifespan (e.g., Vaillant and Milofsky [1980] use the metaphor of a spiral as one may revisit aspects of former struggles) (see e.g., McAdams, 2001; Schoklitsch & Baumann, 2012; Vaillant, 1993, 2012; Wilt et al., 2010). As an example, longitudinal studies have shown that issues of intimacy and identity continue to be important issues in later stages of development (Sneed et al., 2012; Whitbourne et al., 2009). In addition, adult psychosocial development is no longer seen as narrowly tied to age ranges as developmental milestones may occur at different times based on experiences and self-concept (Lachman, 2004; Vaillant & Milofsky, 1980).

Based on in-depth study of the lives of men from age 19 through age 60, Vaillant and Milofsky (1980) revised Erikson’s initial model to add a stage of career consolidation – occurring between the stages of intimacy and generativity – that is considered a precursor to the capacity to invest fully in both mentees and the wellbeing of the next generation. They suggested that career consolidation occurs through the internalization of one’s own mentors, allowing an individual to become less self-absorbed and more able to see him/herself as contributing to a specific role within broader society.

Erikson’s theory has also been subsequently evaluated in terms of its implicit and explicit statements regarding gender socialization (Franz & White, 1985; Gilligan, 1982; Helson, Stewart, & Ostrove, 1995; Stewart & McDermott, 2004; Stewart & Ostrove, 1998). The theory been criticized for conclusions about the relationship between anatomy and gender identity, an underdeveloped perspective on the centrality of intimacy and attachment, and for both falsely differentiating men and women or at other times overgeneralizing from men on to women (Franz & White, 1985; Gilligan, 1982; Sorell & Montgomery, 2001). In addition, there is evidence that cohort effects tied to particular socio-historical periods that relate to gender socialization in identity development (Helson et al., 1995; Whitbourne et al., 2009). Erikson (1968) believed that men and women followed the same sequence of development (stages and order). In thinking about differences between men and women, he speculated that women would achieve identity later than men and more in the context of intimate relationships. In contrast, Gilligan (1982) suggested, that instead of identity preceding intimacy, these processes might develop more simultaneously in women. It is notable, that Erikson’s model reflected an effort to broaden Freud’s (1905) psychosexual stages to also consider how the external world impacted development. As part of this effort he emphasized that societal structures facilitated and constricted aspects of development (Erikson, 1968). This is particularly important to consider in the present study given that it is comprised of all men born in the early twentieth century living in the United States where there were specific expectations from society regarding gender norms about development in one’s career and relationships.

The stages of development particularly associated with middle adulthood in the revised Erikson model include career consolidation and generativity (see Table 1). However, Erikson was clear that preceding developmental tasks remained important throughout the lifespan (Erikson, 1959, 1986). For example, Marcia (1966) drew upon Erikson’s concept of developmental crises to propose that identity development is defined by an individual’s crisis and commitment such that there is a willingness to engage with both exploring and decision making that is followed by a resolution in which one chooses and defines oneself as a person. Kroger (2014) illustrates how Marcia’s identity development classifications can be applied to later adulthood and allow for the study of change and stability of identity as one navigates challenges associated with middle and late adulthood and balances the need to explore and define themselves at multiple periods of life.

Developmental theory suggests that generativity may have particular significance for successful aging as it draws on a range of cognitive and emotional capacities (McAdams, 2001; McAdams & St. Aubin, 1992; Schoklitsch & Baumann, 2012; Slater, 2003). In their empirical study of generativity, McAdams and St. Aubin (1992) describe the “actions” of generativity as including “creating”, “maintaining” and “offering” which lead to a personal narrative. Based on this conceptualization, we hypothesized that generativity would require relatively intact neuropsychological capacities to remember, organize, be selective of salient moments, and ultimately formulate meanings. Generativity reflects not simply productivity but the interplay of internal needs with connections to society that leads to concern for and active nurturance of a new generation (Erikson, 1950).

In previous research with our own longitudinal sample, we found that Erikson psychosocial development at age 47 was relatively independent of chronological age (Vaillant & Milofsky, 1980). In addition, social class and level of education were only weakly tied to level of maturation. Finally, the developmental stages occurred rather sequentially such that the ability to support another’s development (the hallmark of the stage of generativity) evolves from the abilities developed in forming intimate connections with others and consolidating one’s career.

Eriksonian Psychosocial Development and Neuropsychological Abilities

At each phase of adulthood, an individual’s development within relational and occupational contexts requires adequately maintained cognitive engagement and abilities. For example in the life phase focused on generativity one draws heavily upon various cognitive domains as he or she articulates, models, and instills their experience with a new generation (e.g., organizational capacities, verbal abilities, working memory, performance). In contrast to this optimal development, failures of different psychosocial development tasks (e.g., social isolation, loneliness, and lack of engagement with one’s career) are tied to cognitive decline as assessed by neuropsychological batteries and functional MRI (Berkman, Glass, Brissette, & Seeman, 2000; Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009; DiNapoli, Wu, & Scogin, 2013; Krueger et al., 2009; Shankar, Hamer, McMunn, & Steptoe, 2013; Small, Dixon, McArdle, & Grimm, 2012).

In this study we utilized standardized performance-based neuropsychological assessments designed for adults in late life. Such batteries remove the biases of subjective self- or observer reports, allowing us to actually compare how individuals navigated cognitive challenges using standardized approaches, replicable tasks, and statistical norms (Stuss & Levine, 2002). In addition, clinical neuropsychological batteries allow us to look not only at global functioning as assessed by a measure tapping a range of abilities (e.g., the Mini Mental Status Exam; MMSE; Folstein et al., 1975) but also at specific neuropsychological domains (i.e., executive functioning and memory) with links in the literature to late-life depression and psychosocial functioning (Snyder, 2013; Stuss & Levine, 2002). Executive functioning tasks assess an individuals ability to rely on working memory to maintain focus on a goal while also inhibiting other dominant responses (Miyake et al., 2000). Components of neuropsychological testing batteries are regularly used to assess executive functioning (Burgess, 2010; Burgess, Alderman, Evans, Emslie, & Wilson, 1998). We chose tests involving “set shifting” (which demonstrate the ways in which an individual is able to repeatedly and flexibly disengage with an irrelevant tasks in order to reengage with a more relevant task) and “inhibition” referring to the inability to inhibit a dominant response (Miyake et al., 2000). The memory tasks used in this study examine the ability to recall newly learned semantic information immediately, following a delay, with the help of recognition cues, and in the face of distractions (Morris et al., 1989).

Within a number of longitudinal studies, global late-life cognitive functioning (primarily assessed with the MMSE or similar performance-based measures) correlates with positive aspects of one’s social relationships, the complexity and degree of engagement with one’s occupation, having diverse leisure activities, and being involved with the broader community (Holtzman et al., 2004; Hsu, 2007; Kåreholt, Lennartsson, Gatz, & Parker, 2011; Lee, Kim, & Back, 2009; McGue & Christensen, 2007; Menec, 2003; Seeman, Lusignolo, Albert, & Berkman, 2001; Small et al., 2012; Zunzunegui, Alvarado, Del Ser, & Otero, 2003)– all of which are facets of mature psychosocial development in Erikson’s framework. However, to our knowledge, no studies have examined directly the relationship of Erikson’s model to late-life neuropsychological functioning.

In addition to examining measures of global cognitive functioning, some research has examined specific neuropsychological domains and outcomes of psychosocial functioning. For example, in a longitudinal study Seeman et al. (2001) found that lower executive functioning in individuals over 65 is associated with declining social engagement, higher levels of social strain or conflict, and less social contact, while memory scores were only associated with amount of social contact and declining engagement.

Despite this growing body of research linking characteristics of psychosocial development with late-life cognition, results across studies are not entirely consistent, even when using comparable neuropsychological assessment measures. For example in a prospective longitudinal study, Aartsen and colleagues (2002) did not find significant associations between social, experiential, or developmental (e.g., pursuing a course of study) experiences and outcomes of global cognitive functioning or specific neuropsychological domains (e.g., memory and executive functioning) and suggest that retained neuropsychological capacities may be more tied to socioeconomic status. Fritsch et al. (2007) found that late-life cognition, memory, and verbal fluency were associated with education level but not other expected midlife factors (from retrospective reports) such as physical, social, or mental occupational demands.

Therefore, while a number of prospective longitudinal studies indicate that global cognition, memory, and executive functioning in late life are associated with not only concurrent but also earlier occurring psychosocial variables, the results are not conclusive. Erikson’s developmental model provides a potential framework for understanding how engagement with one’s psychosocial world may relevant to maintaining stronger cognitive abilities into late life.

In the present study, maturity of psychosocial development (as indexed by Eriksonian development stages coded by independent raters) provides an alternative to previous studies that utilize self-report of discrete individual variables of psychosocial functioning. By examining midlife Eriksonian psychosocial development in this paper, a theoretically rich picture emerges as to how the quality or levels of one’s psychosocial engagement may contribute to late-life global cognition, memory, and executive functioning. The advantage of this approach is that it relies on clinically trained raters who consider the person’s overall engagement with the social world from a developmental perspective.

Depression as a Mediator

While prior theory and research suggest that midlife psychosocial development predicts late-life neuropsychological abilities, we anticipated that this relationship would be partially mediated by late-life depression. Specifically we expected that difficulties meeting developmental goals in relationships, work, and experiences of generativity would lead to higher levels of despair and that would exacerbate cognitive decline. This is consistent not only with Erikson’s theoretical framework, but also with empirical evidence which suggests that social factors such as a sustained close relationships (Zhanga & Lia, 2011), fulfillment of career identity (Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999), connectedness and commitment to the community and others (McGue & Christensen, 2007) are all associated with greater psychological well being and lower rates of depression as people age.

It is well established that depression directly linked to neuropsychological functioning, specifically executive functioning (Alexopoulos et al., 2000; Beblo, Sinnamon, & Baune, 2011; Butters et al., 2000; Porter, Bourke, & Gallagher, 2007) and memory (Baune et al., 2010; Bhalla et al., 2006). With regard to executive functioning, Dotson et al. (2008) suggest that the connection between higher depression and lower executive functioning may be stronger in old age than at other life stages. Older adults with depression also consistently show greater deficits in executive functioning compared to older adults without depression (Lockwood, Alexopoulos, & van Gorp, 2002). In contrast, memory impairment may be associated not simply with concurrent depression but also with the chronicity of depression across the lifespan (Basso & Bornstein, 1999; Fossati et al., 2004; Rapp et al., 2005). A number of studies report that recurrent depression has toxic effects that may actually lead to hippocampal atrophy (Ballmaier et al., 2008; Gorwood, Corruble, Falissard, & Goodwin, 2008; Sheline, 1996; Steffens et al., 2000).

In sum, through the integration of theory and research we expected that Eriksonian psychosocial development in midlife would be associated with both late-life depression and cognitive functioning, even after controlling for intelligence and highest level of education. In addition, based on the empirical research linking depression and cognitive domains, we hypothesized that late-life depression would mediate the relationship between midlife Eriksonian psychosocial development and outcomes of overall cognitive functioning, executive functioning, and memory even when controlling for the effects of intelligence and highest level of education.

Method

Participants & Procedures

Participants were a subsample of 159 men drawn from the Study of Adult Development, an over 75 year longitudinal study that has followed two cohorts of men from late adolescence until late life. The College cohort was comprised of 85 men taken from a larger sample of 268 Harvard college sophomores (born between 1915–1924) in a study of male psychological health. Original selection criteria included absence of physical and mental illness and satisfactory freshman academic record (Heath, 1945). These men were all Caucasian and primarily of middle and upper socioeconomic status. The Inner City cohort consisted of 74 men selected from an original sample of 456 men, chosen when they were adolescents as the non-delinquent control group for a longitudinal study of juvenile delinquency (Glueck & Glueck 1968). Participants were matched with members of the delinquent group with respect to IQ, economic disadvantage, and residence in high crime neighborhoods. All Inner City participants were Caucasian and primarily of Irish-American and Italian-American heritage. The subset of men used in the current study was selected based on availability of midlife Erikson data and late-life neuropsychological data1. Demographic data are included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations for Cohorts and Overall sample (N=159)

| College (N=85) | Inner City (N=74) | t | Total (N=159) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | ||

|

|

|||||||

| Age | 85.98 | 1.65 | 78.58 | 1.83 | 26.63** | 82.53 | 4.08 |

| Education | 18.64 | 1.64 | 12.53 | 2.57 | 17.57** | 15.80 | 3.72 |

| Adolescent IQ | 137.07 | 11.65 | 87.48 | 13.99 | 23.92** | 114.06 | 27.90 |

| Erikson Stage | 4.47 | .77 | 4.08 | 1.00 | 2.72* | 4.29 | .90 |

| Late-life Depression | 5.96 | 4.44 | 6.49 | 5.13 | −.68 | 6.21 | 4.77 |

| MMSE | 26.55 | 2.13 | 24.89 | 2.51 | 4.48** | 25.77 | 2.45 |

| Memory | |||||||

| CERAD List Learning | 17.18 | 4.83 | 14.90 | 3.74 | 3.27** | 16.13 | 4.49 |

| CERAD Delayed Recall | 4.36 | 2.58 | 3.89 | 2.01 | 1.27 | 4.14 | 2.34 |

| CERAD Recognition | 18.43 | 1.81 | 17.96 | 1.82 | 1.63 | 18.21 | 1.83 |

| Free recall | 25.32 | 8.19 | 26.53 | 7.69 | −.94 | 25.89 | 7.96 |

| Free and cued | 46.63 | 2.19 | 46.36 | 3.65 | .55 | 46.50 | 2.96 |

| Executive Functioning | |||||||

| FAS | 40.93 | 13.08 | 30.12 | 11.72 | 5.42** | 35.90 | 13.55 |

| Category | 32.77 | 10.32 | 32.16 | 8.44 | .40 | 32.49 | 9.47 |

| Trails B | 145.81 | 76.15 | 150.87 | 65.52 | −.43 | 148.17 | 71.20 |

p<.01;

p≤.001

Key: MMSE: Mini Mental State Exam; CERAD: Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease;

On entry into the study, the men in both cohorts were assessed by internists, psychiatrists, psychologists, and anthropologists. Parents were also interviewed. Over the next 60 years, men completed questionnaires approximately every two years, their medical records were obtained every five years, and they were interviewed by study staff approximately every 10–15 years. When men were in their 70s and 80s, they were given a full neuropsychological battery to assess domains of cognitive functioning. These were performance-based assessments conducted in participants’ homes by trained examiners that allowed for the examination of cross-sectional and longitudinal associations with psychosocial factors. As part of this assessment, participants also completed self-report measures and clinical interviews to describe their current psychosocial functioning.

Procedures

Measures

Midlife Eriksonian Psychosocial Development

Independent coders rated the men’s midlife psychosocial development (between ages 30–47) using a scale based on Vaillant’s modified version of Erikson’s model (see Vaillant & Milofsky, 1980 for detailed description). Ratings were made on a 5 point scale (1= less than stage 5, 2= stage 5 Identity, 3=stage 6 Intimacy, 4=stage 6a Career Consolidation, 5=stage 7 Generativity) indicating the highest stage achieved. The scale differed from the Eriksonian model in two ways. The sixth stage, intimacy versus isolation, was split into stage 6, intimacy, and stage 6a, career consolidation. Stage 7, generativity versus stagnation, became stage 7, generativity and stage 7a, guardianship (see Table 1). Vaillant & Milofsky (1980) indicated that as part of the applied coding scheme the individual’s life as a whole was taken into account based on the vast available data in the participants file (lengthy narrative interviews, self-report data, medical records). For example, a Catholic priest was coded generative although he was unmarried based on the experiences in his life that showed long-standing commitment within close partnerships. Relatedly, if a man became physically ill and could no longer pursue his career he was not rated at a lower psychosocial stage because of this loss in physical functioning. In both sub-samples, Eriksonian developmental stage was coded based on the written summary of a two-hour narrative interview with the men at age 47. Initial reliability on ratings of level of Eriksonian development was established using the college sample (r[94]=.61), and discrepancies were resolved by consensus of the coders and research team. For the Inner City sample, the rating was the consensus judgment of two clinicians who were familiar with all the data about participants between ages 30 and 47. This data included data from a midlife interview and self-report questionnaires (completed approximately every 2 years). Previous research using this scale in our study found that level of Eriksonian development was largely independent of social class and education, but did correlate in meaningful ways with expected outcomes of length and satisfaction of marriage, success in career, subjective happiness, adaptive personality defenses, and general positive qualities of their childhood experiences (Vaillant, 2012; Vaillant & Drake, 1985; Vaillant & Milofsky, 1980). Evidence for reliability and support for concurrent validity of the stages has been demonstrated in other samples using this same coding system (including Vaillant’s additional stage of Career Consolidation) in midlife for both men and women (Vaillant & Vaillant, 1990; Westermeyer, 2004).

Depression

Late-life depression was measured using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS, Yesavage et al., 1983). The GDS is a 30-item self-rating scale used to screen for depression in older adults. It is scored by summing the number of depressed responses, resulting in a range from normal to moderately/severely depressed (high scores indicate more severe depression). The test is meant to pick up on psychological symptoms of depression rather than somatic complaints, as to avoid confounding depression with common physical complaints of the elderly population. Validity of the GDS has been demonstrated by good agreement with depression ratings using the Research Diagnostic Criteria, the Zugn Self-Rating Depression Scale, and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Yesavage et al., 1983). The measure has good internal consistency and test-retest reliability.

Neuropsychological Variables

Global Cognitive Function was assessed using the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE, Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975). The MMSE is a 30-item measure that provides a global estimate of cognitive function or global cognition and is sensitive to the detection of dementia (Cacho et al., 2010; Folstein et al., 1975; Mitchell, 2009). The MMSE consists of 5 sections: orientation, immediate recall, attention and calculation, and memory recall and language/visuoconstructions. Scores on each section are summed to create a total score. Scores are then factored by age and fall within the categories of normal, mild, or moderate/severe impairment in cognitive status. The MMSE has been shown to have good validity and reliability (Folstein et al., 1975).

Executive functioning was assessed using an aggregate score derived from three tests: The Trail Making Test Part B, Controlled Oral Word Association (F-A-S) Test and the Category Generation (CAT) test (Monsch, Bondi, Butters, Katzman, & Thal, 1992; Reitan, 1958).

The Trail Making Test Part B is a timed test that requires individuals to sequentially connect numbers and letters in alternative sequence (e.g., 1-A-2-B… etc). This test requires individuals to inhibit dominant responses and alternate between cognitive sets. The test discriminates between brain injured subjects and controls (Retain 1958).

The FAS and the CAT Tests measure both frontal and temporal lobe functioning (semantic and phonemic/lexical knowledge). These timed tasks require participants to rely on working memory to generate words that begin with specific letters or fall in certain categories (e.g., animals). Participants generate words that begin with certain letters and categories for one minute each. Raw scores are derived from the sum of the number of words generated on each timed set. Performance is strongly associated with both verbal IQ and age (Bolla, Gray, Resnick, Galante, & Kawas, 1998). Combining FAS and CAT scores has shown greater sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value of both executive and cognitive functioning than examining them alone (Monsch et al., 1992).

Burgess and colleagues (1998) demonstrated that these and other neuropsychological tests presumed to measure executive functioning deficits have ecological validity. Participants completed a self-report questionnaire that assessed dysfunction in domains of executive functioning including what they called inhibition (e.g., response suppression problems, impulsivity, lack of concern for social rules, and impaired abstract reasoning) and executive memory (e.g., confabulation, temporal sequencing problems, and perseveration). Inhibition difficulties were significantly associated with worse performance on the neuropsychological tasks of Trails B, FAS, and CAT (r=.27–.43). Executive memory difficulties were significantly associated with poorer performance on the FAS and CAT tasks (r=.30–.40).

In this study, scores from all three tests were standardized and then averaged to create a composite variable of executive functioning. Means and standard deviations for each individual measure in the full sample and broken down by cohorts are included in Table 2.

Memory was measured by creating a composite score from the scales of two widely-used tests, the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) 10 Word List and the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT). Memory tests were geared specifically to the recall and recognition of semantic information.

The CERAD has three parts: Word Recall, Delayed Recall, and Recognition. The Word Recall Task or list learning task asks participants to read 10 words aloud and then recall any words they can remember in 90 seconds. This is repeated two more times. The Delayed Recall task asks participants to remember any words from the list after a period of five minutes. The Recognition task asks participants to identify if any words on a new list of 20 words were on the original list. Validity of this assessment is supported by good agreement with clinical diagnosis of dementia. Interrater reliability ranged from .92 to 1.0, test-retest reliability ranges from .43 to .83 (Morris et al., 1989).

The FCSRT is a 16-item free and cued recall test that uses category words to present items for learning and then uses the same category words to cue the participant when the item is not freely recalled. The scores are the number of correctly recalled words, without cues (free recall) and with and without cues (total recall). Scores range from 0 to 48, with higher scores indicating better performance. The FCSRT is sensitive to age and dementia-related memory decline (Grober, Sanders, Hall, & Lipton, 2010). To create the composite memory score, participants’ scores on the three CERAD subtests and two FCSRT subtests were first individually standardized and then averaged.

Results

We first examined the means and standard deviations of demographic variables and neuropsychological variables in the full sample and separately in the College sample and Inner City sample. As can be seen in Table 2, t-tests revealed that on average the college sample were older, had higher adolescent IQs and levels of education. The college men were classified as having achieved a higher Eriksonian psychosocial stage (when assessed within the time frame of ages 30–47) and had higher scores on the Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE) than their Inner City counterparts. There were no differences in the samples with respect to scores for depression and most of the individual tests of executive functioning and memory. In all further analyses we utilized standardized MMSE scores, composite executive functioning scores, and composite memory scores.

We next examined correlations among the variables, which revealed that higher midlife Eriksonian development was associated with both lower levels of late-life depression and better executive functioning and MMSE scores (See Table 3). Eriksonian development was unrelated to the composite late-life memory score. Greater depression was associated with worse performance on all concurrent neuropsychological tests. Based on the significant correlations we conducted two sets of mediation analyses. First, we examined whether the relationship between Eriksonian development and MMSE was mediated by depression. Second, we examined whether the relationship between Eriksonian development and later executive functioning was mediated by depression. We did not test a mediation model for memory as there was no significant association between Eriksonian development and memory, thus ruling out a precondition for mediation. In all mediation analyses we also controlled for adolescent IQ and highest level of education.

Table 3.

Correlations of Standardized Neuropsychological Tests and Composite Variables (N=159)

| Midlife Erikson Stage | Late-life Dep. | MMSE | Memory | CERAD LL | CERAD DR | CERAD Rec | Free Rec | Free & Cued | Exec Funct | FAS | CAT | Trails B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midlife Erikson Stage | - | ||||||||||||

| Late-life Depression | −.29*** | - | |||||||||||

| MMSE | .22** | −.24** | - | ||||||||||

| Memory Composite | .06 | −.22** | .47*** | - | |||||||||

| CERAD List Learning | .10 | −.12 | .49*** | .80*** | - | ||||||||

| CERAD Delayed Recall | .00 | −.21** | .40*** | .85*** | .71*** | - | |||||||

| CERAD Recognition | .01 | −.05 | .21** | .78*** | .53*** | .63*** | - | ||||||

| Free recall | .02 | −.23** | .46*** | 78*** | .46*** | .59*** | .41*** | - | |||||

| Free and cued | .07 | −.19* | .21* | .70*** | .34*** | .36*** | .46*** | .54*** | - | ||||

| Executive Functioning Composite | .20* | −.30*** | .45*** | .57*** | .54*** | .48*** | .35*** | .45*** | .37*** | - | |||

| FAS | .18* | −.19* | .43*** | .38*** | .41*** | .32*** | .23** | .26** | .26** | .81*** | - | ||

| Category | .17* | −.23** | ..35*** | .55*** | .46*** | .42*** | .34*** | .47** | .32*** | .81*** | .53*** | - | |

| Trails B | .08 | −.27** | .24** | .42*** | .40*** | .42*** | .27** | .32*** | .29*** | .75*** | .38*** | .38*** | - |

p<.05;

p<.01

p≤.001;

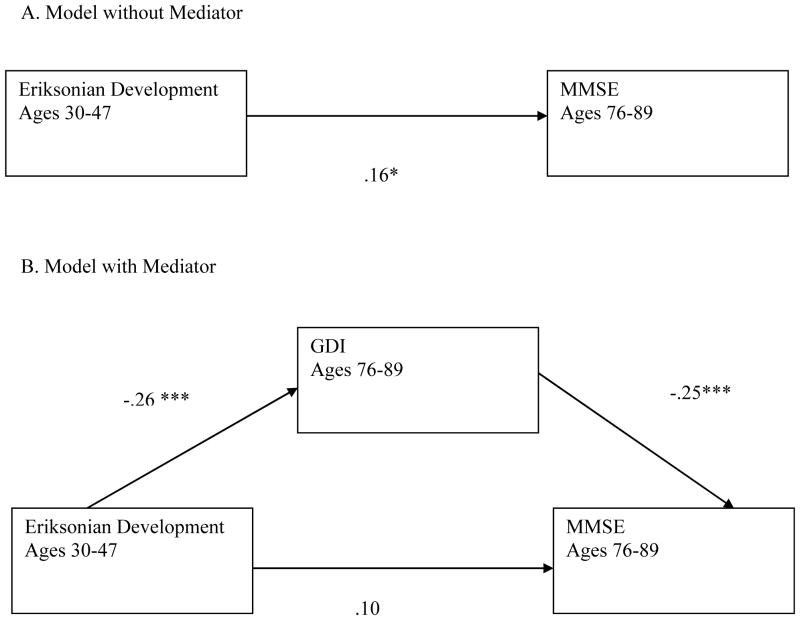

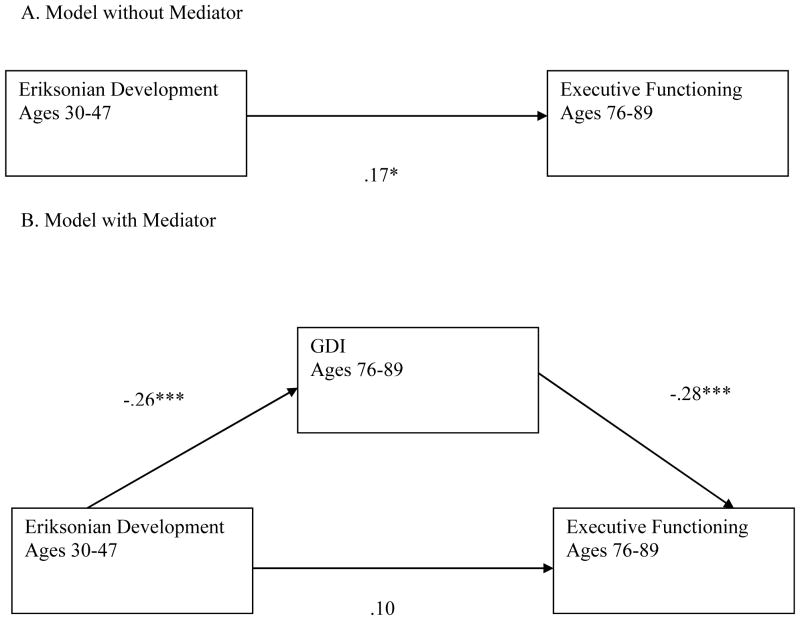

To test whether late-life depression mediated the relationship between Eriksonian development and outcomes of MMSE and executive functioning we followed the recommendations of Baron and Kenny (1986) (see Figures 1 and 2). In completing the analyses we used the SPSS macro for simple mediation developed by Preacher and Hayes (2004), which provides estimates of both direct and indirect effects using the Sobel method and also utilizes non-parametric bootstrapping procedures.

Figure 1.

Concurrent late-life Depression as a Mediator of Midlife Eriksonian Development and Late-life Global Cognition†

* p<.05, **p≤.01, ***p≤.001

Figure 2.

Concurrent late-life Depression as a Mediator of Midlife Eriksonian Development and Late-life Executive Functioning§

* p<.05, **p≤.01, ***p≤.001

Figure 1 shows the standardized coefficients for the regression equations of the mediation analysis. The total effect of Eriksonian development on MMSE was significant as was the effect of Eriksonian development on depression. The effect of the mediating variable, depression, controlling for Eriksonian development was also significant, suggesting that regardless of Eriksonian development, those reporting higher levels of depression had lower levels of global cognitive functioning. Finally, we examined the direct effect of Eriksonian development on MMSE while controlling for depression. This effect was not statistically significant, indicating that when controlling for depression, Eriksonian development no longer was associated with global cognitive functioning as measured by the MMSE. In examining the indirect effect, the Sobel test (z = 2.34; p < .05) was significant, indicating significant partial mediation. We next derived a bootstrapped sampling distribution the bootstrap output supported with 95% confidence that the indirect effect was different from zero (.02 to .19). Thus these analyses support that depression mediates the effects of Eriksonian development on MMSE.

We followed the same procedures to test whether depression mediated the relationship between Eriksonian development and executive functioning, controlling for IQ and highest level of education (Figure 2). The mediation was again supported in our regression model, with level of Eriksonian development no longer being a significant predictor of late life executive functioning when depression was included in the model. We used the Sobel test to examine the indirect effect (z = 2.38; p <.05) and found support for partial mediation. Using a bootstrapped sampling distribution we found additional support for the mediation with a 95% confidence interval that the indirect effect was different than zero (.03 to .17).

To understand our results further, we conducted reverse path analyses to determine whether the relationship between Eriksonian development and depression was mediated by either MMSE or executive functioning. In these analyses, there was no evidence supporting MMSE as a mediator, as both Eriksonian development and MMSE remained significant in the final model. Similarly, executive functioning also failed to function as a mediator of Eriksonian development and late-life depression, as both Eriksonian development and executive functioning remained significant in the final model. In these reverse path mediation analyses we continued to control for highest level of education and adolescent IQ.

Discussion

Erikson’s model of psychosocial development has been central to modern understanding of the ways in which individuals adaptively engage with relationships, vocations, and community across the lifespan (Busch & Hofer, 2012; Kroger, 2014; Sneed et al., 2012; Vaillant, 1993, 2012; Wilt et al., 2010). Yet empirical study of the model is under-developed. This may be due to the complexity of the model, which requires in-depth knowledge of an individual’s life across many domains. Previous research from our longitudinal study drew upon extensive qualitative and quantitative data to code Eriksonian development in midlife and to examine the concurrent psychosocial correlates (Vaillant & Milofsky, 1980; Vaillant, 2012). In the present study, we extended these earlier findings and found that, even after controlling for adolescent intelligence and highest level of education, maturity of Eriksonian developmental stage in midlife is associated with less depression and better global cognition and executive functioning in late life. Our results suggest that a developing and productive engagement with the world during middle age may be an important factor for building a foundation for sustained cognitive flexibility (i.e., response inhibition, abstract thinking, and flexibly shifting between activities or ideas). Our findings are consistent with previous research suggesting the quality of one’s psychosocial engagement is related to better psychological and cognitive health (Berkman et al., 2000; Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009; Diener et al., 1999; Seeman et al., 2001; Small et al., 2012; Zhanga & Lia, 2011).

In this study, our hypothesis that late-life depression would mediate the relationship between midlife Eriksonian development and late-life cognition was partially supported. Specifically, depression partially mediated the relationship between midlife Eriksonian development and late-life global cognition (MMSE) and between midlife Eriksonian development and late-life executive functioning. These results provide some initial support for the idea that individuals who are more engaged with different psychosocial domains in their lives (as indicated by having accomplished a series of cumulative developmental tasks) may maintain better cognitive functioning into old age, in part because they are less depressed. Our findings are consistent with a rapidly growing body of research highlighting the ways in which depression in late life may diminish cognitive functioning in numerous domains (Beblo et al., 2011; Bhalla et al., 2006; Porter et al., 2007). Due to the concurrent assessment of late-life depression and cognition in this study, we cannot make causal statements about the impact of depression on cognition. However, our results are compatible with the hypothesis that Eriksonian development may impact overall cognition and the specific domain of executive functioning via the presence of concurrent late-life depression. In addition, confidence in our mediation findings is strengthened by the failure of either global cognition or executive functioning to mediate the relationship between midlife Eriksonian development and late-life depression in reverse path analyses.

Interestingly, there was no support for late-life depression mediating the relationship between Erikson stage and late-life memory. While greater depression was associated with weaker memory, late-life memory appeared to be independent of one’s earlier psychosocial functioning. These findings highlight the ways in which psychosocial functioning may correlate to specific domains of neuropsychological functioning in late life rather than a general profile.

The results of this study are important for adult development, given that more adults are now living into late life. Findings suggest that individuals who cultivate satisfying and successful engagement with their careers, intimate relationships, and then invest in the nurturance of others in midlife, may in fact be setting the stage for better emotional and cognitive health in old age. For example, generativity requires the use of sophisticated communication, emotional capacities, and systematic thought as one reflects on his or her own achievements and then coherently conveys this to another person to whom they are investing in.

This study has a number of strengths including using prospectively-collected data from a longitudinal study to examine the relationship between midlife development and late-life wellbeing. Study assessments include multiple methods – independent ratings of psychosocial functioning, self-report data on late-life depression, and performance-based measures of cognitive functioning. Our study is also the first that we are aware of to prospectively examine the contributions of the widely used Eriksonian model of adult development to late-life neuropsychological outcomes. Our results may have particular utility for thinking about how interventions at the psychosocial level may have implications for better cognitive and emotional health many years later. For example, the developmental demands of generativity may be contributing the preservation of flexible and abstract thinking or the ability to thoughtfully reflect on the bigger picture before blurting out an initial response. Therefore, nurturing identity development of individuals in midlife may have significant health implications for later in life.

This study also has a number of important limitations. While our sample included significant socioeconomic diversity, study participants were all Caucasian men born in the early twentieth century. As noted in the introduction, Erikson’s original theoretical work had limitations in terms of its understanding of gender socialization and may be influenced by the impact of socio-historical cohort effects (Franz & White, 1985; Helson et al., 1995; Stewart & Ostrove, 1998). Thus, we must use caution in considering the generalizability of these results. Next, there are many variables across a number of domains that may have influenced the outcomes of late-life depression and cognition including alcoholism (Delaloye et al., 2010; Schafer et al., 1991), cardiovascular disease (Barnes, Alexopoulos, Lopez, Williamson, & Yaffe, 2006), or psychosocial loss (Ward, Mathias, & Hitchings, 2007). While this study provides an initial picture of how midlife psychosocial functioning relates to late-life outcomes, future studies will benefit from examining how longitudinal trajectories of psychosocial development relate to domains of late-life wellbeing. In considering our findings, it is also important to acknowledge that the rating of Eriksonian psychosocial development had modest inter-rater reliability and relied heavily on resolution of coding discrepancies via discussions to reach consensus. In addition, when coding the Eriksonian stage, coders were not blind to psychosocial functioning and may have been biased by their broad range of knowledge when assigning individuals to a particular stage. It would be beneficial for future studies to test the validity of our approach by comparing the present study’s method of coding Erikson stages with other measures of psychosocial development, generativity, and identity. Despite these weakness, it is notable that the resulting Eriksonian scores have been shown in previous work to correlate in meaningful and expected ways with measures of psychosocial functioning across the lifespan (Soldz & Vaillant, 1999; Vaillant, 1985, 1993, 2012; Vaillant & Davis, 2000; Vaillant & Drake, 1985; Vaillant & McCullough, 1987; Vaillant & Milofsky, 1980). Finally, while our performance-based neuropsychological battery was sophisticated and rigorous in its approach, we only performed these assessments at a single time point. While we were able to control for adolescent IQ and highest level of education, we were unable to control for baseline neuropsychological functioning at the time of evaluation of Eriksonian development. This limits our ability to claim not only cause and effect but also temporal precedence. The fact that our results did not provide a uniform picture that all cognitive outcomes were associated to earlier Eriksonian development (i.e., memory was not) suggests that there may be unique relationships between neuropsychological domains, depression, and earlier psychosocial functioning. In future research it would be beneficial to assess levels of depression prior to neuropsychological testing in order to have temporal separation of the variables within the mediation model. This would also help better delineate apart the relationship between depression and particular domains of neuropsychological functioning.

In conclusion, Erikson (1950) was interested in broadening the study of human development into the later stages of adulthood. His suggestion that there are consequences such as stagnation and emotional despair when individuals fail to successfully navigate developmental challenges may have important implications for understanding and supporting interventions aimed at adult development, health, and wellbeing.

Footnotes

Analyses comparing the participating subsample of College and Inner City men with those in their respective cohorts showed no significant differences on measures of adolescent intelligence, midlife social and marital adjustments, or occupational success at midlife (all t’s<2.0, p’s>.05). However, in both study cohorts, those participating used less alcohol in midlife, and had higher levels of education (all t’s>2.0, p’s<.05).

All analyses controlled for highest level of education and adolescent IQ.

All analyses controlled for highest level of education and adolescent IQ.

References

- Aartsen MJ, Smits CH, van Tilburg T, Knipscheer KC, Deeg DJ. Activity in older adults cause or consequence of cognitive functioning? A longitudinal study on everyday activities and cognitive performance in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57:153–162. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.2.p153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, Kalayam B, Kakuma T, Gabrielle M, … Hull J. Executive dysfunction and long-term outcomes of geriatric depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:285. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballmaier M, Schlagenhauf F, Toga AW, Gallinat J, Koslowski M, Zoli M, … Heinz A. Regional patterns and clinical correlates of basal ganglia morphology in non-medicated schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2008;106:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes DE, Alexopoulos GS, Lopez OL, Williamson JD, Yaffe K. Depressive symptoms, vascular disease, and mild cognitive impairment: findings from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:273. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso MR, Bornstein RA. Relative memory deficits in recurrent versus first-episode major depression on a word-list learning task. Neuropsychology. 1999;13:557–563. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.13.4.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baune BT, Miller R, McAfoose J, Johnson M, Quirk F, Mitchell D. The role of cognitive impairment in general functioning in major depression. Psychiatry Research. 2010;176:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beblo T, Sinnamon G, Baune BT. Specifying the neuropsychology of affective disorders: clinical, demographic and neurobiological factors. Neuropsychology review. 2011;21:337–359. doi: 10.1007/s11065-011-9171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science Medicine. 2000;51:843–857. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla RK, Butters MA, Mulsant BH, Begley AE, Zmuda MD, Schoderbek B, … Becker JT. Persistence of neuropsychologic deficits in the remitted state of late-life depression. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14:419–427. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000203130.45421.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolla KI, Gray S, Resnick SM, Galante R, Kawas C. Category and letter fluency in highly educated older adults. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1998;12:330–338. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess PW. Assessment of executive function. In: Gurd J, Kischka U, Marshall J, editors. Handbook of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 349–371. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess PW, Alderman N, Evans J, Emslie H, Wilson BA. The ecological validity of tests of executive function. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 1998;4:547–558. doi: 10.1017/s1355617798466037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch H, Hofer J. Self-regulation and milestones of adult development: Intimacy and generativity. Developmental psychology. 2012;48:282–293. doi: 10.1037/a0025521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butters MA, Becker JT, Nebes RD, Zmuda MD, Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, Reynolds CF. Changes in cognitive functioning following treatment of late-life depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1949–1954. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacho J, Benito-León J, García-García R, Fernández-Calvo B, Vicente-Villardón JL, Mitchell AJ. Does the combination of the MMSE and clock drawing test (mini-clock) improve the detection of mild Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment? Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2010;22:889–896. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in cognitive sciences. 2009;13:447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L, Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ. Neurocognitive mechanisms in depression: Implications for treatment. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2009;32:57–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Social relationships and health. American Psychologist. 2004;59:676–684. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaloye C, Moy G, de Bilbao F, Baudois S, Weber K, Hofer F. Neuroanatomical and neuropsychological features of elderly euthymic depressed patients with early- and late-onset. Journal of Neurological Science. 2010;299:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith HL. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:276–302. [Google Scholar]

- DiNapoli EA, Wu B, Scogin F. Social isolation and cognitive function in Appalachian older adults. Research on Aging. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0164027512470704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotson VM, Resnick SM, Zonderman AB. Differential association of concurrent, baseline, and average depressive symptoms with cognitive decline in older adults. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;16:318–330. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181662a9c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Childhood and society. New York: Norton; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: W W Norton & Company; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Reflections on the last stage—and the first. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child. 1984;39:155–165. doi: 10.1080/00797308.1984.11823424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH, Erikson JM. The life cycle completed (extended version) New York: WW Norton & Company; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Everard KM, Lach HW, Fisher EB, Baum MC. Relationship of activity and social support to the functional health of older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2000;55:S208–S212. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.4.s208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossati P, Harvey PO, Le Bastard G, Ergis AM, Jouvent R, Allilaire JF. Verbal memory performance of patients with a first depressive episode and patients with unipolar and bipolar recurrent depression. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2004;38:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz CE, White KM. Individuation and attachment in personality development: Extending Erikson’s theory. Journal of personality. 1985;53:224–256. [Google Scholar]

- Freud S. Three essays on the theory of sexuality. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume VII (1901–1905): A Case of Hysteria, Three Essays on Sexuality and Other Works. 1905:123–146. [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch T, McClendon MJ, Smyth KA, Lerner AJ, Friedland RP, Larsen JD. Cognitive functioning in healthy aging: the role of reserve and lifestyle factors early in life. The Gerontologist. 2007;47:307–322. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan C. In a different voice. Harvard University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Glueck S, Glueck E. Unraveling juvenile delinquency. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Gorwood P, Corruble E, Falissard B, Goodwin GM. Toxic effects of depression on brain function: Impairment of delayed recall and the cumulative length of depressive disorder in a large sample of depressed outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:731–739. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07040574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grober E, Sanders AE, Hall C, Lipton RB. Free and cued selective reminding identifies very mild dementia in primary care. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2010;24:284. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181cfc78b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath C. What people are. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Helson R, Stewart AJ, Ostrove J. Identity in three cohorts of midlife women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:544. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.3.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman RE, Rebok GW, Saczynski JS, Kouzis AC, Doyle KW, Eaton WW. Social network characteristics and cognition in middle-aged and older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004;59:278–284. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.6.p278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu HC. Does social participation by the elderly reduce mortality and cognitive impairment? Aging & mental health. 2007;11:699–707. doi: 10.1080/13607860701366335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kåreholt I, Lennartsson C, Gatz M, Parker MG. Baseline leisure time activity and cognition more than two decades later. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2011;26:65–74. doi: 10.1002/gps.2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroger J. Identity development through adulthood: The move toward “wholeness”. In: McLean KC, Syed M, editors. The Oxford handbook of identity development. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014. pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger KR, Wilson RS, Kamenetsky JM, Barnes LL, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Social engagement and cognitive function in old age. Experimental aging research. 2009;35:45–60. doi: 10.1080/03610730802545028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME. Development in midlife. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:305–331. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Kim J, Back JH. The influence of multiple lifestyle behaviors on cognitive function in older persons living in the community. Preventitive Medicine. 2009;48:86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood KA, Alexopoulos GS, van Gorp WG. Executive dysfunction in geriatric depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1119–1126. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE. Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1966;(5):551. doi: 10.1037/h0023281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP. Generativity in midlife. In: Lachman M, editor. Handbook of midlife deveopment. New York: Wiley; 2001. pp. 395–443. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP, St Aubin ED. A theory of generativity and its assessment through self-report, behavioral acts, and narrative themes in autobiography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62:1003–1015. [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Christensen K. Social activity and healthy aging: A study of aging Danish twins. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2007;10:255–265. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menec VH. The relation between everyday activities and successful aging: A 6-year longitudinal study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2003;58:S74–S82. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.2.s74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ. A meta-analysis of the accuracy of the mini-mental state examination in the detection of dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2009;43:411–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive psychology. 2000;41:49–100. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1999.0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsch AU, Bondi MW, Butters N, Salmon D, Katzman R, Thal LJ. Comparisons of verbal fluency tasks in the detection of dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Archives of Neurology. 1992;49:1253–1258. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530360051017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Fillenbaum G, … Clark C. The consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Archives of Neurology. 1989;49:1253–1258. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.9.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter RJ, Bourke C, Gallagher P. Neuropsychological impairment in major depression: its nature, origin and clinical significance. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;41:115–128. doi: 10.1080/00048670601109881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp MA, Dahlman K, Sano M, Grossman HT, Haroutunian V, Gorman JM. Neuropsychological differences between late-onset and recurrent geriatric major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:691–698. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reischies FM, Neu P. Comorbidity of mild cognitive disorder and depression - a neuropsychological analysis. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2000;250:186–193. doi: 10.1007/s004060070023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1958;8:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Kishi R, Suzukawa A, Horikawa N, Saijo Y, Yoshioka E. Effects of social relationships on mortality of the elderly: How do the influences change with the passage of time? Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2008;47:327–339. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer K, Butters N, Smith T, Irwin M, Brown S, Hanger P, … Schuckit M. Cognitive performance of alcoholics: a longitudinal evaluation of the role of drinking history, depression, liver function, nutrition, and family history. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1991;15:653–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoklitsch A, Baumann U. Generativity and aging: A promising future research topic? Journal of Aging Studies. 2012;26:262–272. [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Lusignolo TM, Albert M, Berkman L. Social relationships, social support, and patterns of cognitive aging in healthy, high-functioning older adults: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology. 2001;24:243–255. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.4.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar A, Hamer M, McMunn A, Steptoe A. Social isolation and loneliness: Relationships with cognitive function during 4 years of follow-up in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2013;75:161–170. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31827f09cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheline YI. Hippocampal atrophy in major depression: A result of depression-induced neurotoxicity? Molecular Psychiatry. 1996;1:298–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater CL. Generativity versus stagnation: An elaboration of Erikson’s adult stage of human development. Journal of Adult Development. 2003;10:53–65. doi: 10.1023/a:1020790820868. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Small BJ, Dixon RA, McArdle JJ, Grimm KJ. Do changes in lifestyle engagement moderate cognitive decline in normal aging? Evidence from the Victoria Longitudinal Study. Neuropsychology. 2012;26:144–155. doi: 10.1037/a0026579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneed JR, Whitbourne SK, Schwartz SJ, Huang S. The relationship between identity, intimacy, and midlife well-being: Findings from the Rochester Adult Longitudinal Study. Psychology and aging. 2012;27:318. doi: 10.1037/a0026378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder HR. Major depressive disorder is associated with broad impairments on neuropsychological measures of executive function: a meta-analysis and review. Psychological Bulletin. 2013;139(1):81. doi: 10.1037/a0028727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldz S, Vaillant GE. The Big Five personality traits and the life course: A 45-year longitudinal study. Journal of Research in Personality. 1999;33:208–232. [Google Scholar]

- Sorell GT, Montgomery MJ. Feminist perspectives on Erikson’s theory: Their relevance for contemporary identity development research. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research. 2001;1:97–128. [Google Scholar]

- Steffens DC, Byrum CE, McQuoid DR, Greenberg DL, Payne ME, Blitchington TF, … Krishnan K. Hippocampal volume in geriatric depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2000;48:301–309. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00829-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AJ, McDermott C. Gender in psychology. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:519–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AJ, Ostrove JM. Women’s personality in middle age: Gender, history, and midcourse corrections. American Psychologist. 1998;53:1185. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.11.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuss DT, Levine B. Adult clinical neuropsychology: lessons from studies of the frontal lobes. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:401–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas PA. Trajectories of social engagement and limitations in late life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2011;52:430–443. doi: 10.1177/0022146511411922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant GE. An empirically derived hierarchy of adaptive mechanisms and its usefulness as a potential diagnostic axis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1985;71(S319):171–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1985.tb08533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant GE. The wisdom of the ego. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant GE. Triumphs of Experience: The men of the Harvard Grant study. Cambridge, MA: Belknap, Harvard; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant GE, Davis JT. Social/emotional intelligence and midlife resilience in schoolboys with low tested intelligence. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000 doi: 10.1037/h0087783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant GE, Drake RE. Maturity of ego defenses in relation to dsm-iii axis ii personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1985;42:597–601. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790290079009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant GE, McCullough L. The Washington University Sentence Completion Test compared with other measures of adult ego development. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;144:1189–1194. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.9.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant GE, Milofsky E. Natural history of male psychological health: IX. Empirical evidence for Erikson’s model of the life cycle. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1980;137:1348–1359. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.11.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant GE, Vaillant CO. Determinants and consequences of creativity in a cohort of gifted women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1990;14:607–616. [Google Scholar]

- Ward L, Mathias JL, Hitchings SE. Relationships between bereavement and cognitive functioning in older adults. Gerontology. 2007;53:362–372. doi: 10.1159/000104787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermeyer JF. Predictors and characteristics of Erikson’s life cycle model among men: A 32-year longitudinal study. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2004;58:29–46. doi: 10.2190/3VRW-6YP5-PX9T-H0UH. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbourne SK, Sneed JR, Sayer A. Psychosocial development from college through midlife: a 34-year sequential study. Developmental psychology. 2009;45:1328. doi: 10.1037/a0016550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilt J, Cox KS, McAdams DP. The Eriksonian life story: Developmental scripts and psychosocial adaptation. Journal of Adult Development. 2010;17:156–161. [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer VO. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhanga B, Lia B. Gender and marital status differences in depressive symptoms among elderly adults: The roles of family support and friend support. Aging & mental health. 2011;15:844–854. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.569481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zunzunegui MV, Alvarado BE, Del Ser T, Otero A. Social networks, social integration, and social engagement determine cognitive decline in community-dwelling Spanish older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2003;58:S93–S100. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.2.s93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]