Abstract

Introduction:

Despite its efficacy and widespread use, methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) continues to be widely stigmatized. Reducing the stigma surrounding MMT will help improve the accessibility, retention, and treatment outcomes in MMT.

Methods:

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 18 adults undergoing MMT. Thematic content analysis was used to identify overarching themes.

Results:

In total, 78% of participants reported having experienced stigma surrounding MMT. Common stereotypes associated with MMT patients included the following: methadone as a way to get high, incompetence, untrustworthiness, lack of willpower, and heroin junkies. Participants reported that stigma resulted in lower self-esteem; relationship conflicts; reluctance to initiate, access, or continue MMT; and distrust toward the health care system. Public awareness campaigns, education of health care workers, family therapy, and community meetings were cited as potential stigma-reduction strategies.

Discussion and Conclusion:

Stigma is a widespread and serious issue that adversely affects MMT patients’ quality of life and treatment. More efforts are needed to combat MMT-related stigma.

Keywords: methadone maintenance treatment, stigma, substance abuse, opioid use disorder

Introduction

In recent years, the increasing ease of access to opioids and overreliance on prescription painkillers have resulted in a global opioid abuse epidemic, with 26.4 million to 36 million people suffering from opioid use disorder worldwide.1 Opioid use disorder, in turn, brings about serious health, social, and economic consequences. In the United States alone, prescription opioid abuse results in more than 16 000 deaths1 and $55.7 billion in workplace, health care, and criminal justice costs every year.2 Similarly, in Canada, public programs spend $93 million per year on opioid addiction treatment.3 Although Canada-wide statistics on opioid overdose are not available, in the province of Ontario alone opioid overdose led to 1359 deaths between 2006 and 2008.4 These statistics are so grim, in fact, that in March 2016 President Barack Obama has personally called for action to “escalate the fight against the prescription opioid abuse and heroin epidemic.”5

Although opioid use disorder is a complex condition often resistant to treatment, opioid substitution programs have been shown to be relatively successful, with methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) being the most commonly used treatment.6 Methadone is an opioid receptor agonist whose slow onset of action and long half-life allow it to be used in maintenance or detoxification therapy.6 Meta-analyses have shown that MMT is more effective than placebo, detoxification, drug-free rehabilitation, wait-list controls, or buprenorphine in retaining patients and preventing illicit opioid use.7,8

Despite its efficacy and widespread use, MMT continues to be largely misunderstood and stigmatized. For instance, in a survey of 1067 randomly selected participants, Matheson et al9 found that the public held strong negative attitudes and doubts over the efficacy of MMT. Similarly, public opinion polls and surveys in Canada show that while most of the Canadians support harm-reduction programs, a significant number of individuals disapprove of harm reduction based on the misguided assumption that such programs promote illegal drug use and bring violence into communities.10

Due to the widespread public misunderstanding and distrust toward MMT, patients often experience stigma and discrimination surrounding their treatment.11–14 For instance, a qualitative study of 24 elderly MMT patients found that stigma posed a barrier to substance abuse and mental health care.11 As a result, respondents often tried to conceal their treatment status from health care workers, which is extremely dangerous as it can lead to prescription of interacting medications and opioid overdose.11 Similarly, Anstice et al12 and Harris and McElrath13 both reported that institutional stigma is commonly found in MMT programs; institutional stigma refers to when negative attitudes and beliefs toward methadone are reflected in organization’s policies, practices, or cultures. For instance, patients reported hearing condescending or distrusting remarks from pharmacists and other health care workers, whereas dispensing spaces often made patients feel humiliated and exposed under the public gaze.13 Finally, a survey of 114 MMT patients found moderate to high levels of self-stigma and perceived stigma among patients, with higher experiences of stigma associated with unemployment, intravenous drug use, incarceration, and heroin use.14

Therefore, stigma is a widespread problem in the MMT population. This is particularly concerning as accessibility and retention in MMT tend to be quite low; less than 10% of patients requiring treatment worldwide receive it,15 and only about 60% of patients successfully remain in treatment for more than a year.16 Higher retention, in turn, is linked with positive treatment outcomes such as reduced criminal activity and opioid use and improved employment and school performance.17

These findings show that there is a need for a framework for better understanding and combating MMT-related stigma. Such a framework would help identify common public misconceptions regarding methadone as well as key stigma-reduction strategies. This would, in turn, lead to more effective stigma-reduction strategies that directly target common negative stereotypes surrounding methadone, thus helping to improve methadone treatment accessibility, retention, and outcomes.

Therefore, in this study, we conducted semi-structured interviews with patients undergoing MMT to expand our current understanding of MMT patients’ experiences of stigma and create a framework for combating MMT-related stigma. We hoped to build on the existing literature by going beyond simple categorization of stigma experiences and conducting a more thorough investigation of the exact sources and impact of stigma. Specifically, we aimed to explore (1) the prevalence, sources, and types of stigma faced by MMT patients; (2) the common negative stereotypes associated with MMT; (3) the impact of stigma on patients’ quality of life and treatment; and (4) potential strategies for combating negative stereotypes regarding MMT. The relationship between stigma experiences and socioeconomic status (SES) and location was also explored in a preliminary fashion by comparing patient responses between 2 cities with large disparity in mean SES.

Methods

This study was approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (HIREB #0168).

Participants

Participants were recruited from 2 methadone clinics located in Hamilton and Oakville, ON, between September 2015 and January 2016. The 2 locations were chosen to diversify the study sample, as Hamilton and Oakville are known to have vastly different socioeconomic landscapes. Oakville is a relatively affluent, suburban city with a median household income of $118 671 and poverty rate of 8.6%18; however, Hamilton is a large metropolitan area with a median income of $78 52019 and poverty rate of 18.8%.20 Due to the large differences between the 2 cities, we hoped to compare participant responses between Hamilton and Oakville and look for a potential relationship between stigma and SES.

To be part of the study, participants had to be (1) either currently receiving MMT or enrolled in MMT in the past, (2) 18 years of age or older, (3) able to understand and speak English, and (4) able to provide informed consent. Saturation method was used to determine the sample size, whereby we aimed to continue recruiting participants until no new ideas or themes were being collected in each location.21

Two methods of recruitment were used: flyers and direct approach. Flyers were placed in the waiting areas of the clinics, and patients were encouraged to contact the investigators for more information regarding the study. In addition, with the permission of the methadone clinic staff, 2 trained study investigators (J.W. and A.B.) approached patients in the waiting room to seek potential participants. Both written and verbal consent were obtained from each participant regarding their willingness to participate in the study and have the interview audio-recorded for data collection purposes. Participants were compensated with a $5 coffee shop gift card at the end of each interview.

Demographic questionnaire

Prior to each interview, participants were asked to answer several questions regarding their demographic and SES characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, education, income, employment, and housing.

Semi-structured interview

Two study investigators (J.W. and A.B.) conducted semi-structured, in-person interviews with each participant regarding their experiences of stigma surrounding MMT. Prior to the interviews, both investigators received training from an experienced addiction researcher and psychiatrist (Z.S.) regarding proper interview methodology and ethics. Each interview ran for 30 to 60 min and was audio-recorded.

Stigma was broadly defined as any negative stereotype or discrimination surrounding MMT or MMT patients. Specifically, 3 forms of stigma were addressed through the interviews: public, interpersonal, and self-stigma.22 Public and interpersonal stigma refer to negative remarks, attitudes, or behaviors the participants have heard, witnessed, or experienced from members of the public or through their interpersonal relationships. However, self-stigma refers to negative attitudes and beliefs participants may have toward themselves.

The overall format of the interviews is shown in Table 1. Participants were asked open-ended questions regarding whether or not they have ever experienced MMT stigma; common sources, types, and examples of stigma; their perception of how the public views MMT patients; strategies used to cope with stigma; the impact of stigma experiences on their quality of life and treatment; and suggestions for reducing negative stereotypes regarding MMT. Some questions were derived from a previous study by Wahl,23 which examined mental health care consumers’ experiences of stigma using a combination of quantitative and qualitative methodologies. In addition, 5 questions about perceived stigma (Table 1, question 4b) were derived from the 12-item Perceived Devaluation Discrimination Scale,24 a reliable and validated measure of individuals’ perception of how the public treats and thinks of patients with mental illness.

Table 1.

Overall format of the semi-structured interviews.

| 1. Have you ever experienced stigma related to methadone maintenance treatment? |

| a. If yes, how frequently do you experience stigma? |

| 2. Based on your experience, what is the most common source of stigma regarding methadone? |

| 3. Could you describe 1 or 2 specific stigma experiences? |

| 4. Could you describe how the general public treats/feels about methadone patients? |

| a. Could you tell us, on a scale of 1 to 5, how much you agree with these following statements? (1 being you strongly disagree and 5 being you strongly agree) |

| i. Most people would willingly accept someone who is undergoing methadone treatment as a close friend. |

| ii. Most people believe that someone who is undergoing methadone treatment is just as trustworthy as the average citizen. |

| iii. Most people think less of a person who is receiving methadone treatment. |

| iv. Most employers will hire someone who is receiving methadone treatment if he or she is qualified for the job. |

| v. Most people would be willing to date someone who is receiving methadone treatment. |

| b. How do you think the public perceives the methadone maintenance program? |

| i. Based on your experience, would you say that most people are aware of what methadone is and how it is used for? |

| ii. Have you noticed any public misconceptions or misunderstanding regarding methadone? If so, provide specific examples. |

| iii. Do you believe that the public perceives methadone patients in a more negative manner than individuals undergoing other addiction treatments like abstinence programs? |

| 5. Do you think some of the negative stereotypes about methadone patients are true? |

| a. Do you feel ashamed about being in methadone treatment? |

| 6. Has stigma affected your methadone treatment in any manner? |

| 7. Has stigma affected your daily life in any manner? |

| 8. How do you usually cope with the stigma surrounding methadone? |

| 9. Could you provide some suggestions on how the stigma surrounding drug addiction and methadone could be reduced? |

| 10. If there were one message you would like to give people about drug addiction and methadone, what would it be? |

Following each open-ended question, participants were asked several follow-up questions based on their initial response. As a result, the actual structure and duration of the interviews differed considerably between participants. Participants were always asked whether there was anything else they wished to add or clarify before moving on to the next open-ended question.

Thematic analysis

Interview recordings were transcribed and analyzed using NVivo. Following each interview, 2 study investigators (J.W. and A.B.) independently read and coded each transcript regarding the 4 main research questions: (1) prevalence, sources, and types of stigma; (2) common negative stereotypes associated with MMT; (3) impact of stigma on daily life or treatment; and (4) potential stigma-reduction strategies. This was followed by a reconciliation process, in which the investigators discussed any disagreements between their coding strategies and decided on a final set of codes. Finally, the codes were categorized and combined to identify overarching themes.

Quantitative analysis

The quantitative data were summarized using descriptive statistics, for instance, by calculating the median score on the perceived public stigma questions or the proportion of participants who reported having experienced MMT-related stigma. The descriptive statistics were, in turn, calculated for each of the Hamilton and Oakville sites. However, due to the small size and limited power of our sample, no statistical tests were conducted to look for significant differences between Hamilton and Oakville.

Results

Characteristics of the study sample

A total of 18 individuals participated in this study, with 10 from Hamilton and 8 from Oakville. Originally, 2 additional participants had consented to be in the study from the Oakville site; however, 1 participant failed to show up for the interview and another participant had to be excluded due to his limited English-speaking abilities. In total, 16 participants were undergoing MMT at the time of recruitment. Two participants were receiving Suboxone at the time of recruitment but had received MMT at least 1 year prior.

The sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample are shown in Table 2. The mean age of the participants was 36.11 (SD = 10.01) years. Most of the participants were female (67%) and white (89%). Compared with the Hamilton participants, individuals from Oakville had a higher mean income ($35 000 vs $48 750) and were more likely to be employed (40% vs 63%). However, as no statistical tests were conducted, we are unable to determine whether these differences were statistically significant.

Table 2.

Characteristics of study sample.

| Hamilton (n = 10) | Oakville (n = 8) | Overall (n = 18) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years (SD) | 37.80 (9.51) | 34.00 (10.86) | 36.11 (10.01) |

| Gender (% female) | 7 (70%) | 5 (63%) | 12 (67%) |

| Ethnicity (% white) | 9 (90%) | 7 (88%) | 16 (89%) |

| Mean annual household income, $ (SD) | 35 000 (24 010) | 48 750 (29 246) | 24 000 (11 005) |

| Employment | |||

| % on disability benefits | 4 (40%) | 2 (25%) | 6 (33%) |

| % employed for wages | 4 (40%) | 5 (63%) | 9 (50%) |

| % homemaker/not looking for a job | 2 (20%) | 1 (13%) | 3 (17%) |

| Education | |||

| % with elementary/high school diploma | 6 (60%) | 5 (63%) | 11 (61%) |

| % with college education or higher | 4 (40%) | 3 (38%) | 7 (39%) |

| Introduction to opioids | |||

| Physician’s prescription | 4 (40%) | 5 (63%) | 9 (50%) |

| Friends/family | 5 (50%) | 3 (38%) | 8 (44%) |

| Street | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) |

Overview of stigma experiences

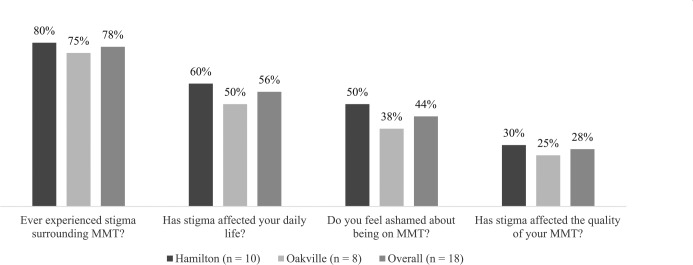

The proportions of participants in Hamilton, Oakville, and the overall study sample who reported experiencing or being affected by stigma are shown in Figure 1. Overall, most of the participants reported having experienced MMT-related stigma at least once (78%). In general, the prevalence of stigma experiences was higher in Hamilton compared with Oakville. Table 3 shows participant responses regarding their stigma experiences. The most commonly cited sources of stigma were friends (56%), health care workers (44%), family (33%), and community members (33%).

Figure 1.

Proportions of participants who reported experiencing or being affected by stigma surrounding methadone maintenance treatment (MMT).

Table 3.

Number of participants reporting each frequency, stigma source, coping strategy, stigma-reduction strategy, and message for the public (n = 18).

| Frequency of stigma experiences | |

| Never | 4 |

| Rarely | 2 |

| Sometimes | 6 |

| Often | 4 |

| Daily | 2 |

| Sources of stigma | |

| Friends | 10 |

| Health care workers | 8 |

| Family | 6 |

| Community members | 6 |

| Employers/coworkers | 3 |

| Coping strategies | |

| Concealment | 11 |

| Avoidance | 10 |

| Confrontation/education | 9 |

| Suggested strategies for reducing stigma | |

| Public awareness campaigns | 13 |

| Education of health care workers | 8 |

| Inviting family to clinic appointments | 5 |

| Community meetings | 2 |

| Messages for the public | |

| Don’t judge those on methadone treatment without getting to know them first | 7 |

| Methadone is extremely helpful for many people; it saves lives | 5 |

| Plea to the public to educate themselves about methadone treatment | 4 |

| No message | 2 |

| Stay away from methadone treatment | 1 |

Negative public perception

Participant responses regarding perceived public stigma are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Participant responses regarding perceived stigma surrounding methadone maintenance treatment (MMT; n = 18).

| Questions regarding public perception | No. reporting yes |

|---|---|

| Do you think the public thinks negatively of MMT patients? | 16 |

| Do you think people think more negatively of MMT compared with abstinence programs? | 14 |

| Do you agree with some of the negative stereotypes about MMT patients? | 9 |

| Do you think the average person knows what methadone is and what it is used for? | 5 |

| Statements regarding perceived stigma | Median score (75% interquartile range)a |

| Most people would willingly accept someone who is undergoing MMT as a close friend | 4 (3-4) |

| Most people believe someone undergoing MMT is as trustworthy as the average citizen | 2.5 (1-3) |

| Most people think less of a person receiving MMT | 4 (4-5) |

| Most employers will hire someone undergoing MMT if he or she is qualified for the job | 2.5 (2-3) |

| Most people would be willing to date someone who is receiving MMT | 3 (2-3.75) |

On a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 = “strongly disagree” and 5 = “strongly agree.”

The following overarching themes were identified.

Methadone as a way to get high, not get better

Although most interviewees reported that the average person is not aware of what methadone is and what it is for (72%), they felt that those who do know what methadone is think negatively of MMT patients (89%). When asked about the common misconceptions surrounding MMT, the most commonly reported answer was the notion that methadone gets patients “high” in the same way as other opioids. Although methadone is not known to induce the feelings of euphoria and intoxication associated with substances such as heroin and morphine, interviewees felt that in the eyes of the public, they were not any different from illegal drug users. A mother reported that even her motive for accessing MMT was often questioned, with others suspecting that they were simply accessing MMT as a way to get high: “I always hear people say—you are just replacing one drug with another drug . . . and that you are still addicted to opioids, you are just using something else to get high.”

Incompetent and untrustworthy

The stereotype that methadone causes patients to get “high” led to the notion that MMT patients are incompetent and unfit to work. A young working man expressed frustration at the discrepancy between the public’s assumptions and his actual lifestyle:

Most people think that people who are on methadone don’t have jobs, they don’t work, they just do nothing all day, get high all day, stuff like that. That’s not true, you know. I work full-time, I have an active life, I have a girlfriend.

Although interviewees believed that being on methadone did not make them any less capable or reliable, they reported that most people would consider an MMT patient to be less trustworthy than the average citizen and that most employers would hesitate to hire someone on MMT even if he or she was qualified for the job (Table 4). A woman described how revealing her methadone status to her employer led to facing stigma and discrimination in the workplace:

I work at a hospital and I take care of people’s medication. So I was on a floor where the boss found out and said, “Well you shouldn’t be giving out narcotics.” Even though I’ve been working here for a long time and I have no interest in stealing narcotics . . . And it was really hurtful . . . I love my job and it’s a big part of who I am. Yes, methadone is part of me, but people just assume that I’m going to try to steal drugs just because I’m on methadone . . . my record shows that I can be trusted.

Lack of willpower

In all, 78% of interviewees believed that the public thinks more negatively of MMT compared with other addiction treatment programs such as abstinence. When asked to elaborate on why that might be, lack of willpower was frequently mentioned as a key stereotype associated with MMT patients: “They think that the person who is able to stay away from everything and doesn’t need any help is stronger than the person who needs methadone to help them.” One interviewee commented on how others find it difficult to understand the challenges of overcoming opioid use disorder: “They look at methadone patients and think, ‘Suck it up and go through withdrawal!’”

Heroin junkies

The last common stereotype associated with MMT was the myth that all individuals on MMT were first introduced to opioids through illegal, street drugs such as heroin. A young man who was first introduced to opioids at an early age showed frustration at people’s tendency to make blanket statements about all MMT patients, when in reality each individual has a unique reason for joining the program: “When they hear you’re on methadone they think you’re a heroin addict . . . and they think that methadone users are criminals. But that’s not everybody . . . people sometimes get in shitty situations.” In fact, this myth was quite far from the truth, considering that 50% of the participants were introduced to opioids through physician’s prescriptions, 44% through friends/family, and only 6% were introduced through street drugs.

This myth was associated with the notion that MMT patients have brought this fate upon themselves and that they are responsible for their opioid use disorder. A female participant who joined MMT due to physician-prescribed painkillers found this generalization particularly unfair and upsetting, claiming that she had little control over their situation:

Maybe they know that you are trying to get better, but they think that you’re still a drug addict. You know, I didn’t take these pills by choice, I actually needed them. Even you, if you were on painkillers for 6 months you’d also be addicted.

Impact of stigma

Self-stigma and lower self-esteem

Interestingly, 50% of participants agreed with at least some of the negative stereotypes associated with MMT. That being said, most interviewees believed that the stereotypes applied to other MMT patients they knew, not directly to themselves. Several interviewees admitted that they personally knew of 1 or 2 individuals who were continuing to use street drugs while on MMT. For instance, a woman stated, “There is some true to the stereotype that people use it as a free crack house. People do do that sometimes. When they don’t have money to do other drugs they come here instead.”

Although some participants directed the stigma toward others, 50% reported that the stigma has caused them to feel ashamed about being on MMT. This self-stigma often led to lower self-esteem and feelings of guilt. A woman who almost lost custody over her daughter due to her methadone status said about her experience: “It was hard. Because I was questioning myself—Am I a drug addict? Am I kidding myself? And I was even considering stopping the medication, and just go through the withdrawal. But I couldn’t, because I had a baby.” Similarly, a young man who faced difficulties finding an employer willing to accommodate for his daily methadone clinic visits described that the stigma left a lasting impact on him: “I felt like shit. I also felt very depressed . . . I lost a lot of weight from like, being depressed over what people’s opinions were of me about being on methadone.”

Conflicts with friends and family

Due to the stigma and misunderstanding surrounding methadone, most interviewees reported that they try not to disclose their methadone status to others, including even close friends and family members. This habit of avoidance and secrecy led to the feeling that they were forced to hide a major aspect of their lives from their loved ones, often putting a strain on their relationships. For instance, a woman described,

I won’t tell a lot of my close friends because I’m fearful they will judge me . . . That causes curiosity I think. Because I’m like, “I gotta go I have an appointment.” And they ask what kind of appointment. And I’m like, “Just an appointment.” And they’re like, “Where? You never tell us.”

However, when participants did decide to disclose their situation to loved ones, it often led to stigmatizing comments and even conflicts. In fact, friends and family were 2 of the most common sources of stigma, reported by 56% and 33% of participants, respectively. Family and friends often struggled to understand the challenges of getting off of methadone, prompting the patients to lower their dosage or leave the program altogether: These familial conflicts could get extreme at times, with a young participant describing how his parents locked him up inside his room when they found out that he was thinking of starting MMT, causing him to undergo extreme symptoms of withdrawal:

My parents found out . . . I was hearing about the program, so they kind of locked me up inside my house and they disconnected the phone from the outside and I wasn’t allowed to leave the house and I was on house arrest unless my parents let me. My uncle told my parents if he leaves the house, call the cops right away . . . And I started feeling the effects, my parents couldn’t handle it because there’s a lot of vomiting . . . One time I picked up the phone when my mom put it on and my uncle was saying, “Oh you know you can’t just let him go on methadone program, he’s just using something else instead to get high, he’s going to get addicted to taking something every day.”

Reluctance to initiate, access, or continue MMT

In all, 30% of interviewees reported that the stigma surrounding methadone has negatively affected the quality of their treatment. Several participants confessed that it took them years between first hearing about methadone and actually deciding to join MMT as they were concerned about the negative stereotypes associated with the program and wished to seek other alternatives before turning to MMT as a last resort. Discouragement from friends and family also played a large role in delaying patients’ entry into MMT.

Moreover, even after patients did commence MMT, they still continued to be extremely wary of accessing it in public, lest their friends, family, employers, or neighbors found out. Few interviewees confessed that they visited a clinic that was hours away from their home and avoided clinics within walking distance—in other words, they felt that they would rather sacrifice hours of their time every day than to risk running into somebody they knew. A woman described how the stigma can make a seemingly simple act such as parking in front of the clinic stressful:

I realized that I have to keep it a secret. I don’t tell people anymore. Even some of my closest friends. A friend was with us and I had to come into the clinic to sample and I had to tell my husband to park way over there so the friend wouldn’t know I was going into the clinic. And I was like, scared, I was saying, “You have to park down the street. You can’t park in the No Frills parking lot because he might see me walking across the street.” It was a big deal.

In addition, the self- and interpersonal stigma surrounding methadone led some patients to contemplate lowering their dosage prematurely, resulting in withdrawal. The mother described her experiences:

They (my family) want me to go down and get off of this stuff. But I don’t want to rush it . . . I kind of have tried to go down a few times but when I try to go down, I went down really quickly. I started to have withdrawals and got sick and I had to go back up again.

Finally, several participants reported that although the stigma caused them to contemplate leaving the program altogether at times, they were never able to put it into action. One participant felt that he was not far enough in his recovery to leave MMT: “I’d probably die if I wasn’t on methadone because I know I’m not strong enough without it,” whereas another man showed resilience and defiance in the face of stigma: “I’ve thought about leaving. But it’s just too hard to do. And in the end I’ve decided that it’s my body, it’s my mind, not theirs.”

Distrust toward health care system

Health care workers were cited as the second most common source of stigma (44%). Participants had faced stigma and discrimination from health care workers in various settings, ranging from family physicians to the emergency room. For instance, those who were first introduced to opioids through physician-prescribed painkillers felt that their own physicians were unequipped to deal with their addiction, often laying the blame on the patients to avoid responsibility. A young woman described the traumatizing effects of this experience:

I don’t have a family doctor at the time. My family doctor, when I was 20, was the one who started prescribing me narcotic painkillers. And when I told him I wanted to get off of them, and that I was going to need either methadone or suboxone to get off of the medications, he said, “Well that’s because you’re an addict.” And he said if you weren’t an addict, a junkie, that you wouldn’t have this problem . . . and he kicked me out of his practice.

Moreover, numerous interviewees described how they are faced with scrutiny and skepticism every time they visit the hospital, with health care workers assuming that they are exaggerating symptoms to access opioids. A woman recounted a story of when she recently visited the emergency room due to severe abdominal pain a couple of years ago:

I told the nurse. I threw up my sleeves and said, “Do you see any needle marks on me?” I even had one nurse say to me, “You probably just came in because you wanted a shot of morphine or something” . . . I cried, I sat in the bed and I cried . . . and I ended up with an obstruction and having a surgery, 5 days later . . . So I wasn’t there just for a shot of morphine. . .

As a result, many participants felt that the greatest impact of stigma surrounding methadone was “just not being able to get the help that I need from the doctors and nurses. Because they believe I’m an addict, a drug seeker. That I’m faking my symptoms or whatever just to get drugs.” This led many to avoid accessing the health care system unless absolutely necessary, for instance, opting to visit walk-in clinics as opposed to making regular appointments with a family physician or choosing not to visit the emergency room despite extreme pain. Some reported even concealing the fact that they are on methadone from health care workers due to fear of stigma.

Suggested stigma-reduction strategies

Public awareness campaigns

The most commonly suggested stigma strategies are shown in Table 3. Public awareness campaigns were suggested by 72% of participants as a potential stigma-reduction strategy. Specifically, participants wished that there was an easy, accessible way for community members to obtain accurate information about what methadone is its mechanisms, what it is used for, and its positive effects on patients and society. One interviewee suggested, “it would be nice if there was like a website that people can go on,” whereas others suggested “more pamphlets and TV ads.” Having pamphlets in “public areas such as Tim Hortons” was also suggested by 1 interviewee. Another idea suggested by an interviewee was to have a “Methadone user recognition day, something that can celebrate people trying to better their lives . . . something to bring awareness to the problem.”

In addition to providing general information about methadone, participants hoped that such campaigns would target specific stereotypes associated with MMT patients, such as the notion that all patients are heroin junkies or that they are incompetent and untrustworthy. A young worker wished to spread the message that MMT patients are indeed trying to get better and overcome their addiction:

I think just educating people that they are trying to get healthy and looking towards a better future. They are not druggies or scum of the earth, and that they are actively looking towards turning things around and trying to be a productive members of society . . . Our motivation is good and positive . . . We don’t want the lifestyle that got us where we are, and this is just one of the tools that we have to assist in getting there.

Participants believed that spreading messages such as these would allow others to approach MMT patients with a more accepting, open-minded manner. One interviewee explained that fear stems from lack of understanding: “People don’t know, so they are afraid,” and thus suggested that education would be the most effective way to target the public’s fear of methadone.

Educating health care workers

The second most common strategy for reducing stigma was education of health care workers, suggested by 44% of participants. Several interviewees believed that nurses and physicians who do not frequently see patients with substance abuse may not fully understand the mechanisms and benefits of methadone. Participants suggested incorporating substance abuse treatment into the continuing education of health care workers through day-long seminars, workshops, or conferences. For instance, a participant with medical condition described her frustration at some physicians’ lack of awareness of methadone and how it may affect prescription patterns:

Some doctors, I have to explain [methadone treatment] to them. When I go in for those vomiting episodes, they only want to give me be 2 mg oral hydromorphine. And I’m telling them I need 8 mg orally, because [methadone] blocks those receptors and renders the opioids ineffective, in a way. Right? So I need a much higher dose. But they don’t understand that. So yeah, some training would be nice for them.

In addition to providing more education on the mechanisms and effects of methadone, participants explained that health care workers should also be trained to be more mindful of any subconscious biases they might have about the program and encouraged to treat MMT patients in a more empathetic, caring manner. A woman suggested,

Healthcare workers should absolutely be educated on how to treat people who are on methadone or are addicted to drugs, instead of looking at them in a negative way. Try to reach out and see if there’s any way they can help out. For me, even though I’m on methadone, if I’m not showing any signs that I’m problematic, then they should treat me just the same as everybody else. The medical profession should really be aware.

Inviting family members to clinic appointments

Greater incorporation of family members into clinic appointments was another suggestion made by 28% of interviewees. As family and friends were the most commonly cited sources of stigma, interviewees felt that having the chance to invite their loved ones to their clinic appointments would help clarify any questions and concerns they may have about the program. For instance, 1 participant discussed how inviting her parent to her psychiatrist appointments truly allowed them to better understand the effects of depression and suggested that the same strategy would be helpful for individuals on MMT:

I invited my dad . . . and they [the psychiatrist] explained everything to my dad, “He can’t control this himself . . . You can’t tell him get off the antidepressants and you’ll be fine. It’s not your brain, it’s his.” And he understood. But my mom, on the other hand, was at home. So my mom kept saying the same thing, but then my father explained it to her. So bringing your parents in . . . is the first step you should do if you are having arguments at home while on a program and they are disagreeing . . .

In other words, by discussing the program with the health care provider, family members may be able to better understand the patient’s reasons for remaining in MMT and in turn act as an advocate for the patient.

Community meetings

Finally, 2 participants—1 from each site—suggested holding regular community meetings in places such as churches, as currently “a methadone user can’t go to church on Wednesday night for example, and they can’t sit around and talk about ways to make methadone treatment better.” Such communal meetings would serve a dual purpose. First, they could create a sense of community for MMT patients and allow them to support one another through the difficult times as well as work together to brainstorm ways on how the stigma can be reduced. Second, the meetings could also be open to the general public and feature MMT patients as well as providers, helping to answer any questions or misconceptions community members may have about the program.

Participants believed that both community meetings and public awareness campaigns would be particularly beneficial in neighborhoods that are about to introduce a new methadone clinic, as such proposals often face a great deal of backlash from the community members. Four interviewees provided a new pain clinic in Burlington as an example:

In Burlington there was a pain clinic that was going to open, and the people living in there were fighting not to have it and they said they didn’t want to have “these” kinds of people around there . . . And I believe that it is society’s fault by not explaining more to people. Having pamphlets in here for us guys to read, but there’s nothing in here for someone who is out on the street and wants to come in and wants to learn . . . Just don’t throw methadone at somebody and here’s a bunch of people without knowing all the facts about it.

Messages for the public

When the interviewees were asked about one message to the public, similar themes emerged in their answers. Overarching themes in the messages are shown in Table 3. The most common answer was a request to not judge those on MMT simply based on their methadone status and to understand that these individuals are simply trying to get better: “Help is help. It’s somebody trying to get better, whether they are doing it wrong or doing it right.” Many also wanted the public to understand that receiving methadone may not be much different from taking any other medication, sending messages such as “we are not any different than the normal person,” “don’t judge a book by its cover,” and “just because you’re on methadone, doesn’t mean you are a bad person.”

Another common theme was the usefulness of methadone and its positive effects on patients, with participants calling it “a tool to turn your life around.” “Methadone helps people; it saves lives,” said one interviewee.

The young man who faced backlash from his family regarding his MMT enrollment explained how methadone allowed him to drastically improve his life:

I graduated top of my school and I was the only person on methadone. But if it wasn’t for the methadone, I wouldn’t have gone to school to begin with. I want people to know that it helps a lot of people. Methadone also helped a lot of people get out of that addiction and start living a sober life and feeling good about themselves again.

Participants also requested the public to educate themselves regarding MMT, which would also help to reduce the stigma surrounding the treatment. One individual requested others to “talk to an actual person who is on methadone and get all the information from them,” whereas another asked the public to “walk a mile in our shoes.” Finally, a man suggested that those in need of treatment for their substance abuse should stay away from MMT if possible, as it continues to be widely stigmatized and misunderstood in the public’s eyes.

Discussion

Through semi-structured interviews with 18 patients undergoing MMT, we found that the stigma surrounding MMT is a prevalent and serious concern experienced by 78% of participants. The most commonly reported stigma sources were friends, health care workers, family, community members, and employers/coworkers. Participants reported often engaging in concealment, avoidance, and education/confrontation as coping strategies. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies on MMT patients and generally among those utilizing the mental health system.14,23,25

In terms of perceived stigma, participants cited 5 common negative stereotypes surrounding MMT: methadone as a way to get high, lack of willpower, incompetence, untrustworthiness, and heroin junkies. Although only participant-perceived stigma was measured, these findings are consistent with those from surveys of the general public. For instance, Matheson et al9 conducted a survey on a random sample of 1067 community members and found that respondents were likely to believe that the only way of helping substance abusers was to make them stop taking drugs altogether and that methadone is unhelpful in combating crime and substance abuse. Similarly, a comprehensive review of public opinion polls between 2003 and 2007 across Canada found that although most of the Canadians support harm-reduction programs, some negative public views prevailed, such as the notion that such programs promote illegal drug use and bring violent individuals into peaceful communities.10

Past research in mental illness stigma suggests that these stigmatizing attitudes may arise from the belief that mental illnesses including addiction are genetic, chronic, and therefore difficult—if not impossible—to treat.26 For instance, in a study of 202 nurses, physicians, medical students, and patients, a biomedical explanation of schizophrenia was associated with more stigmatizing attitudes toward patients with schizophrenia, compared with environmental explanations.26 Similarly, a survey of 85 individuals with severe mental illness and 50 members of the public found that among patients, endorsement of genetic models was correlated with stronger feelings of guilt, fear, and self-stigma.27 Patients reported that the biogenetic model often makes them feel “trapped” and “fundamentally flawed,” as it provides little hope of recovery or being “freed” from the condition.27 Such findings show that a potential stigma-reducing strategy may be to raise greater awareness of psychosocial explanations for mental illnesses.

In terms of the impact of stigma, 28% to 56% of interviewees reported that the stigma has adversely affected their daily life and treatment, leading to lower self-esteem; conflicts with friends/family; reluctance to initiate, access, or continue MMT; and distrust toward the health care system. What is particularly concerning is that many of these effects seem to take away the social and emotional support that MMT patients need to succeed in their recovery. For instance, individuals with substance abuse disorder are significantly more likely than the general population to suffer from other mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety.28,29 In addition, research has shown that patients with stronger social support systems are more likely to enter and remain in MMT.30,31 Thus, by lowering patients’ self-esteem and causing relationship conflicts, stigma may lead to even poorer mental health and treatment outcomes overall.

The finding that stigma poses a barrier to MMT accessibility is similar to the findings by Hunt et al,32 who collected data from 368 current MMT patients and 142 narcotics users. They found that MMT patients were often perceived as incompetent and unemployed, while misguided fears about the long-term effects of methadone also prevailed. These perceptions, in turn, made individuals reluctant to enroll in the program and, once in MMT, ambivalent about their treatment.32 Similarly, in a survey of 124 physicians, most respondents indicated that the social stigma surrounding methadone has caused them to be reluctant about prescribing it for chronic pain, and when methadone was prescribed, patients often refused to take it due to the stigma.33 Such findings show that stigma reduction is a key step in increasing accessibility and retention of MMT, a treatment program already suffering with frequent early dropouts.16

Perhaps, one of the most alarming findings was that health care workers were cited as the second most common source of stigma. The stigma from health care workers can prevent patients from accessing the health care that they need, which is particularly concerning as MMT patients are more likely than the general population to experience other mental physical illnesses and report poorer health outcomes.34 Previous studies have also shown that individuals who perceive higher levels of stigma from MMT clinic staff are more likely to drop out early from treatment.35 Moreover, the stigma can cause patients to conceal their MMT status from health care workers, which has serious potential consequences such as prescription of interfering drugs, opioid overdose, and even death.36

That being said, it is important not to overgeneralize these findings; several participants did note that they have also had positive experiences with helpful and empathetic health care workers. Furthermore, some of the health care workers’ concerns regarding MMT patients are understandable, particularly in a fast-paced, busy setting such as the emergency department. For instance, providers may have valid reasons to be wary of patients visiting hospitals to access opioids, as this could potentially lead to overdose and further spiral into drug dependence. Perhaps, the key is for health care providers to communicate these concerns in a more sensitive, empathetic manner to help create an environment where patients can feel comfortable about disclosing their MMT status.

Implications

Considering the widespread prevalence of stigma experiences and their negative impact on patients’ quality of life and treatment, it is vital that more efforts are made to help reduce the stigma surrounding MMT—particularly the ones suggested by the participants: public awareness campaigns, family therapy, education of health care workers, and community meetings.

Interestingly, the patient-reported strategies seem to capture 2 of the 3 key methods frequently used and reviewed in mental illness stigma literature: educate and contact.37 Brief courses on mental illness have been proven to reduce stigma among variety of populations ranging from the police to high school students.37 Furthermore, research shows that individuals who have met and socialized with members of the minority are less likely to stigmatize against the latter.37 Education coupled with contact is in fact the most effective method of combating stigma as it allows the public to dispel misinformation while also fostering new, positive perceptions of the minority group.37 In that sense, public awareness campaigns and community meetings appear to be promising strategies for combating MMT-related stigma.

Methadone clinics could help organize regular community meetings, some of which are exclusive to MMT patients, while others are open to the public. This would help create a safe space for patients to discuss the challenges they face in the program while also allowing the general public to be more educated about methadone. In fact, recent studies have shown that 12-step, self-help programs similar to Alcoholics Anonymous may lead to reduced opioid use, higher patient satisfaction, as well as reduced self-stigma among MMT patients.38–41 For instance, a study of 53 heroin addicts on MMT found that the length of time in Methadone Anonymous was correlated with decreased use of alcohol, cocaine, and marijuana.38 Patients also rated Methadone Anonymous to be more helpful than the MMT itself, in terms of promoting emotional coping and self-acceptance.38

Moreover, stigma should be more actively incorporated into ongoing methadone treatment and care. MMT providers should actively bring up the topic of stigma in clinic appointments to determine whether the patient is experiencing MMT-related stigma, and if so, whether it is adversely affecting their ability to continue in the treatment. If the provider determines that the patient is indeed being stigmatized, an active discussion should take place between the patient and physician about what steps could be taken to cope with the situation. For instance, inviting family members to clinic appointments should be offered to all patients as an option early on in their treatment.

Education of health care workers is another important step in combating stigma. Studies have shown that health care workers’ personal values affect their attitudes toward drug addicts42 and that some practicing physicians and nurses continue to have little knowledge about methadone and its effects on patient care.43,44 However, not all hope is lost; education and training regarding harm reduction have been shown to be effective in improving health care workers’ attitudes toward and acceptance of MMT.45 Thus, there appears to be benefit in incorporating substance abuse treatment and care into ongoing education of health care workers. For instance, the Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario has published a set of guidelines titled “Supporting Clients on Methadone Maintenance Treatment,” which provides detailed information on the mechanisms and benefits of methadone, MMT-related stigma and barriers to treatment, and ways of developing a collaborative care plan with the patient.46 Similar guidelines should be provided to all health care workers who may come in contact with MMT patients, which includes anyone working in walk-in clinics, family physician’s offices, and emergency departments.

Finally, all of the aforementioned strategies must target specific misconceptions and stereotypes surrounding MMT to be the most effective. For instance, providing statistics on what proportion of patients were first introduced to opioids through prescribed painkillers, and how many patients continue to be employed and high functioning throughout their MMT, may help dispel the myth that all MMT patients are unemployed, incompetent illegal drug users. Information on the molecular mechanisms of methadone could also reduce some of the fears regarding its effects. Moreover, MMT providers should take the time to explain to frustrated families that it can be extremely difficult to be completely independent from methadone, and that remaining in MMT is not a sign of weakness but rather a desire to get better.

Limitations

Our findings are limited by several factors. Although our sample size reached the saturation point for qualitative analyses, it was relatively small for quantitative analyses. Thus, the generalizability of the quantitative findings is limited. Our study was also subject to sampling bias; most of the participants were white, and half were unemployed. The latter may be because individuals who were employed were less likely to consent to participate in the study, as they were often in a rush to get to their workplace from the clinic. Thus, it is possible that our findings do not adequately capture stigma in the workplace or the experiences of cultural and ethnic minorities.

That being said, we did not formally record demographic characteristics of nonresponders and their reasons for declining to participate in the study. As a result, we are unable to compare characteristics of responders and nonresponders or determine whether there was a significant difference between the 2 groups. Similarly, data regarding how long patients have been on MMT were also not collected, although this may have been an important factor in how individuals experience and cope with stigma.

In addition, this study relied entirely on self-reporting of stigma experiences, making it subject to recall, social desirability, and confirmation biases. For instance, individuals may remember negative experiences more strongly than positive ones, resulting in over-reporting of stigma. Furthermore, participants gave examples of their stigma experiences, as opposed to being asked whether they have experienced each potential form of stigma or discrimination; it is possible that some participants forgot to mention certain examples, and as a result, the study may not have captured all relevant stigma experiences. Finally, comparisons in responses between Hamilton and Oakville sites were done in a preliminary fashion, and no statistical tests were conducted due to the small sample size. Thus, no conclusions can be drawn about the impact of SES and clinic location on stigma experiences.

Future research

In the future, studies of larger sample sizes are needed to increase the generalizability of these findings. This could be done by combining quantitative and qualitative methodologies, similar to the methods used by Wahl.23; quantitative surveys could be conducted on a larger sample, followed by in-depth qualitative interviews with a smaller number of participants. Recruitment should be conducted in a greater number of cities and clinics to maximize the diversity of interviewees and their experiences. Furthermore, potential determinants of stigma—such as age, gender, race, income, education, clinic location, and length of time since initiating MMT—should be explored further to determine which patients are at the greatest risk of experiencing and being adversely affected by stigma. Doing so would help produce stigma-reduction programs specifically targeted to each vulnerable group. Moreover, patients’ perceptions of stigma could be compared with the public’s knowledge and attitudes and beliefs about MMT to look for potential similarities and differences between perceived and public stigma. Finally, self-reported stigma experiences could be compared with other measures in a longitudinal manner to ascertain whether stigma truly leads to worse quality of life and treatment outcomes over time. For instance, comparing treatment retention, mental well-being, and employment over time between low- vs high-stigma groups may be useful in further elucidating the relationship between stigma and other outcomes in MMT.

Conclusion

Our findings show that stigma is a prevalent and serious issue faced by many MMT patients. Stigma has important negative consequences on MMT patients’ mental and physical well-being, relationships, and quality of treatment. More active measures need to be taken to address the findings of this study and help reduce the stigma surrounding methadone, for instance, through public awareness campaigns at local levels, continuing education of health care providers regarding substance abuse treatment, and greater incorporation of family members into the program. Doing so would not only lead to greater accessibility of MMT, higher retention, and better treatment outcomes but may also help ensure that patients receive the social and emotional support they need to succeed in their treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants for taking the time to be part of this study.

Footnotes

Peer Review:4 peer reviewers contributed to the peer review report. Reviewers’ reports totaled 1355 words, excluding any confidential comments to the academic editor.

Funding:The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study received in-kind support from the Peter Boris Center for Addiction Research, namely, in the form of reimbursement gift cards for participants. The study was also supported by a research grant from the Hamilton Academic Health Sciences Organization (HAHSO).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: JW, AB, MBhatt, BD, and ZS conceived and designed the experiments. JW and AB interviewed participants and collected data. JW and AB analyzed data. JW, AB, MBawor, MBhatt, BD, LZ, and ZS jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper. JW and AB wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure and Ethics: The authors have read and are in agreement with the ICMJE authorship and conflict of interest criteria. The authors also confirm that this article is unique and not under consideration or published in any other publication and that they have permission from rights holders to reproduce any copyrighted material.

References

- 1. Volkow N. America’s Addiction to Opioids: Heroin and Prescription Drug Abuse. Washington, DC: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Birnbaum HG, White AG, Schiller M, Waldman T, Cleveland JM, Roland CL. Societal costs of prescription opioid abuse, dependence, and misuse in the United States. Pain Med. 2011;12:657–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Howlett K. How opioid abuse takes a rising financial toll on Canada’s health-care system. The Globe and Mail. August 24, 2016. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/investigations/opioids/article31464607/. Accessed November 6, 2016.

- 4. Carter CI, Graham B. Oopid Overdose Prevention & Response in Canada. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Drug Policy Coalition; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Office of the Press Secretary. Obama administration announces additional actions to address the prescription opioid abuse and heroin epidemic. The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2016/03/29/fact-sheet-obama-administration-announces-additional-actions-address. Published March 29, 2016. Accessed June 29, 2016.

- 6. Stotts AL, Dodrill CL, Kosten TR. Opioid dependence treatment: options in pharmacotherapy. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10:1727–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;3:CD002209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mattick RP, Kimber J, Breen C, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2:CD002207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Matheson C, Jaffray M, Ryan M, et al. Public opinion of drug treatment policy: exploring the public’s attitudes, knowledge, experience and willingness to pay for drug treatment strategies. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25:407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Law S, Gogolishvili D, Globerman JM. Public Perception of Harm Reduction Interventions. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Ontario HIV Treatment Network; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Conner KO, Rosen D. “You’re nothing but a junkie”: multiple experiences of stigma in an aging methadone maintenance population. J Soc Work Pract Addict. 2008;8:244–264. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Anstice S, Strike CJ, Brands B. Supervised methadone consumption: client issues and stigma. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44:794–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harris J, McElrath K. Methadone as social control: institutionalized stigma and the prospect of recovery. Qual Health Res. 2012;22:810–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Etesam F, Assarian F, Hosseini H, Ghoreishi FS. Stigma and its determinants among male drug dependents receiving methadone maintenance treatment. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17:108–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organization. The methadone fix. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:161–240.18368195 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Levine AR, Lundahl LH, Ledgerwood DM, Lisieski M, Rhodes GL, Greenwald MK. Gender-specific predictors of retention and opioid abstinence during methadone maintenance treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;54:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Health Canada. Literature Review: Methadone Maintenance Treatment. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Health Canada; http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/alt_formats/hecs-sesc/pdf/pubs/adp-apd/methadone/litreview_methadone_maint_treat.pdf. Published 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Halton Region. Oakville at a Glance. Oakville, Ontario, Canada: Halton Region; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Statistics Canada. Median Total Income, by Family Type, by Census Metropolitan Area. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Statistics Canada; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Social Planning and Research Council of Hamilton. City of Hamilton: Action on Poverty Profile. Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: Social Planning and Research Council of Hamilton; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fusch PI, Ness LR. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qual Rep. 2015;20:1408. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vogel DL, Wade NG, Hackler AH. Perceived public stigma and the willingness to seek counseling: the mediating roles of self-stigma and attitudes toward counseling. J Couns Psychol. 2007;54:40–50 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wahl OF. Mental health consumers’ experience of stigma. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:467–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Link BG. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: an assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. Am Sociol Rev. 1987;52:96–112. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Earnshaw V, Smith L, Copenhaver M. Drug addiction stigma in the context of methadone maintenance therapy: an investigation into understudied sources of stigma. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2013;11:110–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Serafini G, Pompili M, Haghighat R, et al. Stigmatization of schizophrenia as perceived by nurses, medical doctors, medical students and patients. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18:576–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rüsch N, Todd AR, Bodenhausen GV, Corrigan PW. Biogenetic models of psychopathology, implicit guilt, and mental illness stigma. Psychiatry Res. 2010;179:328–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ostacher MJ. Comorbid alcohol and substance abuse dependence in depression: impact on the outcome of antidepressant treatment. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30:69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Davis L, Uezato A, Newell JM, Frazier E. Major depression and comorbid substance use disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21:14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kelly SM, O’Grady KE, Schwartz RP, Peterson JA, Wilson ME, Brown BS. The relationship of social support to treatment entry and engagement: the Community Assessment Inventory. Subst Abus. 2010;31:43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhou K-N, Li H-X, Wei X-L, Li X-M, Zhuang G-H. Relationships between perceived social support and retention patients receiving methadone maintenance treatment in China mainland. Chin Nurs Res. 2016;3:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hunt DE, Lipton DS, Goldsmith DS, Strug DL, Spunt B. “It takes your heart”: the image of methadone maintenance in the addict world and its effect on recruitment into treatment. Int J Addict. 1985;20:1751–1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shah S, Diwan S. Methadone: does stigma play a role as a barrier to treatment of chronic pain? Pain Physician. 2010;13:289–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Garcia-Portilla MP, Bobes-Bascaran MT, Bascaran MT, Saiz PA, Bobes J. Long term outcomes of pharmacological treatments for opioid dependence: does methadone still lead the pack? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77:272–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brener L, von Hippel W, von Hippel C, Resnick I, Treloar C. Perceptions of discriminatory treatment by staff as predictors of drug treatment completion: utility of a mixed methods approach. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bohnert AB, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305:1315–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rusch N, Angermeyer MC, Corrigan PW. Mental illness stigma: concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20:529–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gilman SM, Galanter M, Dermatis H. Methadone anonymous: a 12-step program for methadone maintained heroin addicts. Subst Abuse. 2001;22:247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, et al. A preliminary trial of twelve-step facilitation and acceptance and commitment therapy with polysubstance-abusing methadone-maintained opiate addicts. Behav Ther. 2004;35:667–688. [Google Scholar]

- 40. McGonagle D. Methadone anonymous: a 12-step program. Reducing the stigma of methadone use. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1994;32:5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ronel N, Gueta K, Abramsohn Y, Caspi N, Adelson M. Can a 12-step program work in methadone maintenance treatment? Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2011;55:1135–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Brener L, Von Hippel W, Kippax S, Preacher KJ. The role of physician and nurse attitudes in the health care of injecting drug users. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45:1007–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Taghva A, Amnollahi F, Khoshdel A, Kazemi MR, Alizadeh K. Cardiologists’ knowledge and attitudes about methadone and buprenorphine maintenance treatment: a survey study in Tehran, Iran. Thrita. 2014;3:e20689. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bride BE, Abraham AJ, Kintzle S, Roman PM. Social workers’ knowledge and perceptions of effectiveness and acceptability of medication assisted treatment of substance use disorders. Soc Work Health Care. 2013;52:43–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shen Y-M, Lin S-R, Chen C-L, et al. The dual pathway of professional attitude among health care workers serving HIV/AIDS patients and drug users. AIDS Care. 2013;25:309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO). Supporting Clients on Methadone Maintenance Treatment. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: RNAO; http://rnao.ca/sites/rnao-ca/files/Supporting_Clients_on_Methadone_Maintenance_Treatment.pdf. Published 2009. [Google Scholar]