Abstract

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common malignant tumors worldwide. Human WW domain-containing oxidoreductase (WWOX) gene has been identified as a tumor suppressor gene in multiple cancers. We hypothesize that genetic variations in WWOX are associated with HCC risk.

Methodology/Principal findings

Five single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of the WWOX gene were evaluated from 708 normal controls and 354 patients with HCC. We identified a significant association between a WWOX single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), rs73569323, and decreased risk of HCC. After adjustment for potential confounders, patients with at least one T allele at rs11545028 of WWOX may have a significantly smaller tumor size, reduced levels of α-fetoprotein and alanine aminotransferase (ALT). Moreover, the A allele at SNP rs12918952 in WWOX conferred higher risk of vascular invasion. Additional in silico analysis also suggests that WWOX rs12918952 polymorphism tends to affect WWOX expression, which in turn contributes to tumor vascular invasion.

Conclusions

In conclusion, genetic variations in WWOX may be a significant predictor of early HCC occurrence and a reliable biomarker for disease progression.

Introduction

Primary liver cancer, particularly hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), has emerged as the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide[1] and has been ranked as the second most prevalent malignant cancer in Taiwan. Currently, hepatic resection and liver transplantation are widely recognized as effective therapeutic options for HCC [2, 3]. However, the tumor recurrence rate at 5 years after hepatic resection is approximately 70% [4, 5]. Etiologically, HCC is a complex malignancy that has been associated with various risk factors, including chronic hepatitis B (HBV) infection, excessive alcohol intake, and metabolic diseases [6]. In addition to known etiologies, studies have also suggested that the impact of genetic factors within the coding and noncoding regions of tumor suppressor genes decreases gene expression and increases the carcinogenesis of HCC or intrahepatic metastasis of the primary tumor [7–9].

The human WW domain-containing oxidoreductase (WWOX) gene, located on chromosome 16q23.3–24.1, spans one of the most active fragile sites, which contains the FRA16D. WWOX is a bona fide tumor suppressor gene, which plays a pivotal role in regulating signaling pathways and cellular functions [10–16]. Studies have suggested that WWOX can induce apoptosis both in vivo and in vitro by interacting with p53, p73, and JNK1 [11, 17]. Moreover, Hsu et al. concluded that TGF-β1 and hyaluronan can activate HYAL-2-WWOX-SMAD4 signaling to cause cell death [15]. Additionally, evidence from in vivo overexpression studies suggests that WWOX might suppress the carcinogenetic effect of MDA-MB-435 breast cancer cells [18]. However, low or decreased expression and aberrant transcription of WWOX has been reported in several types of cancer, including nonsmall cell lung cancer (85%), prostate cancer (84%), breast cancer (63%), and oral cancer (40%) [19–24]. Moreover, Aqeilan et al. created mice carrying a targeted deletion of the WWOX gene to observe incidence of tumor formation. The results shown that WWOX is a bona fide tumor suppressor [25]. In addition, the loss of WWOX expression is correlated with higher tumor stages and less favorable outcomes in patients [26].

Recently, the genetic alteration of the WWOX gene showed a high incidence of loss of expression in squamous cell lung carcinoma [27, 28]. Notably, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in various genes reportedly modulate their expression and are associated with the risk of several cancers [29, 30]. In addition, SNPs within the WWOX gene have been identified as a potentially genetic risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma and multiple myeloma [31, 32]. Recently, genome-wide linkage analysis studies for SNPs in prostate cancer patients have revealed that WWOX polymorphic variants may be associated with cancer susceptibility [33]. Of these, the WWOX polymorphism is considered to be a useful and tractable measure to evaluate the associations between the SNPs and clinicopathological characteristics of cancers.

Considering the potential function of the WWOX gene in the neoplastic process, SNPs in this gene may be associated with HCC risk. To test this hypothesis, we performed a hospital-based study to evaluate the impact of gene variations of WWOX on the development of HCC and observed an association of a WWOX SNP (rs12918952) with the risk and progression of HCC.

Materials and methods

Patient specimens

In 2007–2015, for the case group, we recruited 354 patients (252 men and 102 women; mean age = 62.97 ± 11.60 years; age range = 30–90 years) at Chung Shan Medical University Hospital in Taichung, Taiwan. During the same study period, the 708 individuals (504 men and 204 women) were enrolled as these subjects received a physical examination at the same hospital. Patients with only HCC were recruited. Patients and normal controls were excluded if having any history of other cancers. For both groups, we administered a questionnaire to obtain information on their exposure to tobacco use, and alcohol consumption. Medical information of the patients, including TNM clinical staging, primary tumor size, and lymph node involvement was obtained from their medical records. Before commencing the study, approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, and informed written consent was obtained from each individual.

Sample preparation and DNA extraction

The whole blood specimens, collected from controls and HCC patients, were placed in tubes containing EDTA and were immediately centrifuged. The genomic DNA was extracted from buffy coats using a QIAamp DNA blood mini kits as described in detail previously [34]. DNA was dissolved in TE buffer and used as the template in polymerase chain reactions.

SNP selection and genotyping

In this study, the selection of 5 well-characterized common polymorphisms from WWOX gene is based on their wide associations with the development of cancer [35, 36]. We included rs11545028 in the 5’UTR region. Rs12918952 and rs3764340, which are located in the exon of WWOX, were selected in this study since these 2 SNPs may result from amino acid changes and thus the loss of the tumor suppression function of WWOX [37]. The allelic discrimination of WWOX rs11545028 (Assay ID: C_2813530_10), rs12918952 (Assay ID: C_57888_20), rs3764340 (Assay ID: C_25654217_20), rs73569323 (Assay ID: C_25761998_10), and rs383362 (Assay ID: C_2395473_20) polymorphisms were assessed using an ABI StepOne TM Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and analyzed using SDS v3.0 software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Bioinformatics analysis

Several semi-automated bioinformatics tools were applied to assess whether WWOX rs12918952 SNPs are associated with a putative function that might affect patient outcomes. GTEx database[38] from the ENCODE project [39] were used to identify the regulatory potential of candidate functional variants. The GTEx data were used to identify correlations between SNPs and whole blood-specific gene expression levels.

Statistical analysis

Mann–Whitney U-test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare the age, gender differences and demographic characteristic distributions between the controls and patients with HCC. The odds ratio and 95% CIs of the association between the genotype frequencies and HCC risk and the clinical pathological characteristics were estimated using multiple logistic regression models. p < 0.05 was considered significant. The data were analyzed on SAS statistical software (Version 9.1, 2005; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Characteristics of study participants

The demographic characteristics and clinical parameters of the 2 study groups, including age, sex, and alcohol and tobacco consumption, are shown in Table 1. A significant difference in the alcohol consumption (p < 0.001) was observed between healthy controls and HCC patients, whereas no such significant between-group difference was observed in the tobacco consumption (p = 0.350). However, neither age (p = 0.287) nor sex (p = 1.000) elevated the HCC risk.

Table 1. The distributions of demographical characteristics and clinical parameters in 708 controls and 354 patients with HCC.

| Variable | Controls (N = 708) | Patients (N = 354) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | |||

| ≤60 | 274 (38.7%) | 149 (42.1%) | p = 0.287 |

| >60 | 434 (61.3%) | 205 (57.9%) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 504 (71.2%) | 252 (71.2%) | p = 1.000 |

| Female | 204 (28.8%) | 102 (28.8%) | |

| Alcohol consumption | |||

| No | 597 (84.3%) | 224 (63.3%) | p<0.001 |

| Yes | 111 (15.7%) | 130 (36.7%) | |

| Tobacco consumption | |||

| No | 441 (62.3%) | 210 (59.3%) | p = 0.350 |

| Yes | 267 (37.7%) | 144 (40.7%) | |

| Stage | |||

| I+II | 233 (65.8%) | ||

| III+IV | 121 (34.2%) | ||

| Tumor T status | |||

| ≤T2 | 237 (66.9%) | ||

| >T2 | 117 (33.1%) | ||

| Lymph node status | |||

| N0 | 342 (96.6%) | ||

| N1+N2 | 12 (3.4%) | ||

| Metastasis | |||

| M0 | 336 (94.9%) | ||

| M1 | 18 (5.1%) | ||

| vascular invasion | |||

| No | 292 (82.5%) | ||

| Yes | 62 (17.5%) |

Association between WWOX gene polymorphisms and HCC

Table 2 shows the genotype distributions and associations between HCC patients and healthy controls with WWOX polymorphisms. The alleles with the highest distribution frequency at WWOX rs11545028, rs12918952, rs3764340, rs73569323, and rs383362 in HCC patients and controls were homozygous for C/C, homozygous for G/G, homozygous for C/C, homozygous for C/C, and homozygous for G/G, respectively. After adjustment for several variables, individuals with polymorphisms at rs11545028, rs12918952, rs3764340, and rs383362 showed no reduction in the risk of HCC. However, compared with the wild-type individuals, individuals carrying C/T or C/T+T/T at rs73569323 exhibited a 0.305-fold (95% CI: 0.126–0.741) or 0.299-fold (95% CI: 0.123–0.724; both p <0.05) lower risk of HCC, respectively.

Table 2. Distribution frequency of WWOX genotypes in 708 controls and 354 patients with HCC.

| Variable | Controls (N = 708) n (%) | Patients (N = 354) n (%) | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs11545028 | ||||

| CC | 410 (57.9%) | 212 (59.9%) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| CT | 261 (36.9%) | 124 (35.0%) | 0.919 (0.701–1.204) | 0.950 (0.719–1.255) |

| TT | 37 (5.2%) | 18 (5.1%) | 0.941 (0.523–1.692) | 0.939 (0.513–1.719) |

| CT+TT | 298 (42.1%) | 142 (40.1%) | 0.922 (0.711–1.195) | 0.949 (0.726–1.239) |

| rs12918952 | ||||

| GG | 637 (90.0%) | 310 (87.6%) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| GA | 70 (9.9%) | 42 (11.9%) | 1.233 (0.822–1.850) | 1.179 (0.775–1.793) |

| AA | 1 (0.1%) | 2 (0.5%) | 4.110 (0.371–45.496) | 3.933 (0.333–46.441) |

| GA+AA | 71 (10.0%) | 44 (12.4%) | 1.273 (0.854–1.899) | 1.218 (0.806–1.840) |

| rs3764340 | ||||

| CC | 594 (83.9%) | 290 (81.9%) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| CG | 106 (15.0%) | 63 (17.8%) | 1.217 (0.865–1.714) | 1.236 (0.869–1.757) |

| GG | 8 (1.1%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0.256 (0.032–2.057) | 0.241 (0.029–2.007) |

| CG+GG | 114 (16.1%) | 64 (18.1%) | 1.150 (0.821–1.610) | 1.163 (0.823–1.646) |

| rs73569323 | ||||

| CC | 669 (94.5%) | 348 (98.3%) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| CT | 38 (5.4%) | 6 (1.7%) | 0.304 (0.127–0.725)* | 0.305 (0.126–0.741)* |

| TT | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) | ---- | ---- |

| CT+TT | 39 (5.5%) | 6 (1.7%) | 0.296 (0.124–0.705)* | 0.299 (0.123–0.724)* |

| rs383362 | ||||

| GG | 529 (74.7%) | 282 (79.7%) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| GT | 170 (24.0%) | 70 (19.8%) | 0.772 (0.564–1.057) | 0.744 (0.538–1.028) |

| TT | 9 (1.3%) | 2 (0.6%) | 0.265 (0.089–1.943) | 0.481 (0.101–2.290) |

| GT+TT | 179 (25.3%) | 72 (20.3%) | 0.755 (0.554–1.028) | 0.732 (0.532–1.006) |

The odds ratios (ORs) and with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated by logistic regression models. The adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated by multiple logistic regression models after controlling for alcohol consumption.

* p value < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Correlation between polymorphic genotypes of WWOX and clinical status of HCC

The distributions of the clinicopathological characteristics and WWOX genotypes in HCC patients were further explored (Tables 3 and 4). As shown in Table 3, patients with at least one polymorphic allele of rs11545028 (C/T or T/T genotype) were less prone to develop large tumors (p = 0.039). In addition, we observed that the trend of G/A+G/G genotype of WWOX rs12918952 for vascular invasion risk (p = 0.024) was higher in male patients with HCC. Furthermore, we also examined the potential association between WWOX gene polymorphisms and the clinicopathological markers of HCC, including α-fetoprotein, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and the AST/ALT ratio. However, we observed significantly lower α-fetoprotein and ALT levels in patients who carried the rs11545028 C/T or T/T genotypes (p = 0.013 and 0.041, respectively; Table 5). Furthermore, in HCC patients, compared with the C/C genotype, the C/G and G/G genotype of WWOX rs3764340 were associated with higher AST and ALT levels (both p < 0.05).

Table 3. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of clinical status and WWOX rs11545028 genotypic frequencies in 354 HCC patients.

| Variable | Genotypic frequencies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC (N = 212) | CT+TT (N = 142) | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Clinical Stage | ||||

| Stage I/II | 132 (62.3%) | 101 (71.1%) | 1.00 | p = 0.085 |

| Stage III/IV | 80 (37.7%) | 41 (28.9%) | 0.670 (0.424–1.058) | |

| Tumor size | ||||

| ≦ T2 | 133 (62.7%) | 104 (73.2%) | 1.00 | p = 0.039* |

| > T2 | 79 (37.3%) | 38 (26.8%) | 0.615 (0.387–0.979) | |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||

| No | 205 (96.7%) | 137 (96.5%) | 1.00 | p = 0.911 |

| Yes | 7 (3.3%) | 5 (3.5%) | 1.069 (0.332–3.436) | |

| Distant metastasis | ||||

| No | 202 (95.3%) | 134 (94.4%) | 1.00 | p = 0.700 |

| Yes | 10 (4.7%) | 8 (5.6%) | 1.206 (0.464–3.134) | |

| Vascular invasion | ||||

| No | 175 (82.5%) | 117 (82.4%) | 1.00 | p = 0.970 |

| Yes | 37 (17.5%) | 25 (17.6%) | 1.011 (0.578–1.767) | |

| Child-Pugh grade | ||||

| A | 163 (76.9%) | 107 (75.4%) | 1.00 | p = 0.739 |

| B or C | 49 (23.1%) | 35 (24.6%) | 1.088 (0.662–1.790) | |

| HBsAg | ||||

| Negative | 123 (58.0%) | 87 (61.3%) | 1.00 | p = 0.542 |

| Positive | 89 (42.0%) | 55 (38.7%) | 0.874 (0.566–1.349) | |

| Anti-HCV | ||||

| Negative | 114 (53.8%) | 66 (46.5%) | 1.00 | p = 0.178 |

| Positive | 98 (46.2%) | 76 (53.5%) | 1.340 (0.875–2.051) | |

| Liver cirrhosis | ||||

| Negative | 41 (19.3%) | 29 (20.4%) | 1.00 | p = 0.802 |

| Positive | 171 (80.7%) | 113 (79.6%) | 0.934 (0.549–1.590) | |

The ORs with analyzed by their 95% CIs were estimated by logistic regression models.

> T2: multiple tumor more than 5 cm or tumor involving a major branch of the portal or hepatic vein(s)

* p value < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Table 4. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of clinical status and WWOX rs12918952 genotypic frequencies in 252 male HCC patients.

| Variable | Genotypic frequencies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG (N = 224) | GA+AA (N = 28) | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Clinical Stage | ||||

| Stage I/II | 139 (62.1%) | 22 (78.6%) | 1.00 | p = 0.086 |

| Stage III/IV | 85 (37.9%) | 6 (21.4%) | 0.446 (0.174–1.144) | |

| Tumor size | ||||

| ≦ T2 | 140 (62.5%) | 22 (78.6%) | 1.00 | p = 0.094 |

| > T2 | 84 (37.5%) | 6 (21.4%) | 0.455 (0.177–1.166) | |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||

| No | 115 (96.0%) | 27 (96.4%) | 1.00 | p = 0.909 |

| Yes | 9 (4.0%) | 1 (3.6%) | 0.885 (0.108–7.257) | |

| Distant metastasis | ||||

| No | 211 (94.2%) | 27 (96.4%) | 1.00 | p = 0.627 |

| Yes | 13 (5.8%) | 1 (3.6%) | 0.601 (0.076–4.778) | |

| Vascular invasion | ||||

| No | 190 (84.8%) | 19 (67.9%) | 1.00 | p = 0.024* |

| Yes | 34 (15.2%) | 9 (32.1%) | 2.647 (1.106–6.338) | |

| Child-Pugh grade | ||||

| A | 174 (77.7%) | 21 (75.0%) | 1.00 | p = 0.749 |

| B or C | 50 (22.3%) | 7 (25.0%) | 1.160 (0.466–2.886) | |

| HBsAg | ||||

| Negative | 120 (53.6%) | 16 (57.1%) | 1.00 | p = 0.721 |

| Positive | 104 (46.4%) | 12 (42.9%) | 0.865 (0.391–1.913) | |

| Anti-HCV | ||||

| Negative | 127 (56.7%) | 15 (53.6%) | 1.00 | p = 0.753 |

| Positive | 97 (43.3%) | 13 (46.4%) | 1.135 (0.516–2.496) | |

| Liver cirrhosis | ||||

| Negative | 47 (21.0%) | 4 (14.3%) | 1.00 | p = 0.406 |

| Positive | 177 (79.0%) | 24 (85.7%) | 1.593 (0.527–4.816) | |

The ORs with analyzed by their 95% CIs were estimated by logistic regression models.

> T2: multiple tumor more than 5 cm or tumor involving a major branch of the portal or hepatic vein(s)

* p value < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Table 5. Association of WWOX genotypic frequencies with HCC laboratory status.

| Characteristic | α-Fetoprotein a (ng/mL) | AST a(IU/L) | ALT a(IU/L) | AST/ALT ratio a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs11545028 | ||||

| CC | 5119.4 ± 1411.9 | 156.8 ± 23.3 | 134.4 ± 18.4 | 1.55 ± 0.12 |

| CT+TT | 799.5 ± 229.9 | 101.1 ± 14.4 | 84.6 ± 11.1 | 1.36 ± 0.07 |

| p value | 0.013* | 0.072 | 0.041* | 0.232 |

| rs12918952 | ||||

| GG | 3785.0 ± 975.8 | 136.5 ± 16.9 | 116.5 ± 13.5 | 1.46 ± 0.08 |

| GA+AA | 579.4 ± 345.3 | 120.3 ± 25.3 | 99.6 ± 15.2 | 1.54 ± 0.23 |

| p value | 0.218 | 0.725 | 0.642 | 0.729 |

| rs3764340 | ||||

| CC | 3655.0 ± 991.4 | 99.9 ± 8.5 | 93.9 ± 8.5 | 1.40 ± 0.06 |

| CG+GG | 2170.3 ± 1520.9 | 291.0 ± 71.7 | 290.96 ± 71.7 | 1.78 ± 0.31 |

| p value | 0.506 | <0.001* | <0.001* | 0.059 |

| rs73569323 | ||||

| CC | 3443.6 ± 871.7 | 135.5 ± 15.4 | 115.1 ± 12.1 | 1.48 ± 0.08 |

| CT+TT | 78.1 ± 37.1 | 70.7 ± 25.6 | 72.7 ± 29.1 | 1.08 ± 0.11 |

| p value | 0.613 | 0.581 | 0.647 | 0.507 |

| rs383362 | ||||

| GG | 3317.0 ± 931.6 | 138.8 ± 18.6 | 116.8 ± 14.5 | 1.53 ± 0.10 |

| GT+TT | 3659.3 ± 2122.9 | 117.3 ± 16.2 | 105.1 ± 15.0 | 1.24 ± 0.06 |

| p value | 0.873 | 0.569 | 0.695 | 0.124 |

Mann-Whitney U test was used between two groups.

a Mean ± S.E.

* p value < 0.05 as statistically significant.

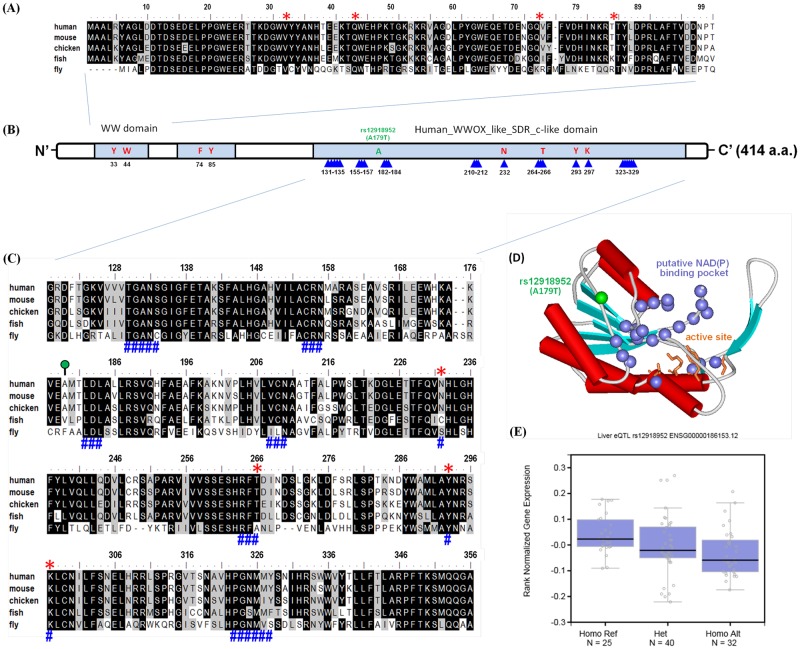

Functional analysis of the WWOX rs12918952 locus

To validate whether the Ala-179-Thr substitution influenced gene expression levels, we used multiple sequence alignment and 3-dimensional (3D) structures to understand the locations of amino acid residues and protein structures for the preliminary assessment of the putative functional roles of SNPs. Multiple alignment data showed the portion of the amino acid sequence of the WW domain within WWOX, and the Ala-179-Thr variation, which was located near the key amino acid of the cofactor binding site in human WWOX like SDR c-like domain (Fig 1A–1C). The homology-based 3D protein structure of WWOX shows the putative coenzyme NAD (P)-binding pocket and predicts the active site using the SWISS-MODEL base on the M. abscessus short chain dehydrogenase or the reductase crystal structure as a template. The rs12918952 variants are positioned within the functional cofactor binding of the WWOX gene (Fig 1D). In addition, given the association of WWOX genetic substitution with gene expression, we used the Genotype–Tissue Expression (GTEx) database to explore whether rs12918952 was associated with the expression of WWOX in human HCC. Individuals carrying rs121918952-variant genotypes (GA or AA) showed a trend of decreased expression of WWOX compared with that of the wild-type homozygous GG genotype (Fig 1E). The rs12918952 G to A substitution probably affects catalytic activity, decreases WWOX mRNA expression, and subsequently enhances the vascular invasion of HCC.

Fig 1. Structural characterization and SNP (rs12918952) in human WWOX protein (NP_057457.1).

Alignments of conserved domain-based sequences of (A) two conserved tryptophans domain (WW; cd00201) and (C) classical-like SDR domain (human_WWOX-like_SDR_c-like; cd09809) by use of multiple sequence alignment format and numbered according to the human WWOX is shown above the sequences. Strick consensus amino acids in the putative active centers of compact structural units are shown: the key amino acids of active site and cofactor binding site are highlighted in red star and blue pound signs, respectively. The WWOX-relative sequences are as follows: human (H. sapiens, NP_057457.1); mouse (M. musculus, NP_062519.2); chicken (G. gallus, NP_001025745.1); fish (D. rerio, NP_957207.1) and fly (D. melanogaster, NP_609171.1). (B) Schematic representation of the overall human WWOX protein; domain symbols are drawn approximately to scale. The rectangle represents the WW and human_WWOX-like_SDR_c-like domain; the key residues of active site and cofactor binding site are highlighted in red and triangle sign, respectively. The N-terminal and C-terminal ends are indicated (N’ and C’, respectively). (D) Ribbon diagram showing the homologous 3D model of the SDR_c-like domain of human WWOX using the SWISSMODEL server based on M. abscessus short chain dehydrogenase or reductase crystal structure (PDB ID: 3RIH). The side chains of the amino acids characterized catalytic tetrad of Asn232-Thr266-Tyr293-Lys297 are shown as sticks and labeled which aligned well with the ‘classical’ type of short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) enzyme. The blue spheres represent the putative coenzyme NAD (P)-binding pocket is drawn to illustrate the location of the cofactor binding site. The ribbons indicate the backbone course of human WWOX and the arrows represent b-strands, and cylinders indicate a-helices. The figure was prepared using ViewerLite™ 5.0 software. (E) Expression quantitative trait locus association between rs12918952 genotype and WWOX expression in whole blood (GTEx data set). Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of cases.

Discussion

Several studies have suggested that WWOX polymorphic variants are consistently associated with more aggressive phenotypes and poor outcomes in numerous malignant diseases, including esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, thyroid carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, and lung cancer [36, 40–42]. In the current study, we evaluated variations in the WWOX gene and the clinicopathological development of HCC across 2 independent individuals. Furthermore, we reported the additional finding that WWOX expression was downregulated in HCC, which strengthened the evidence of a link between polymorphic variations and susceptibility to HCC.

Alcohol consumption, HBV or HCV infection, history of liver cirrhosis, and family history of HCC are the major etiologic factors for HCC in Taiwan [43, 44]. Our data show that the number of individuals with a history of alcohol consumption was higher among the HCC patient group (36.7%) than among the control participants (15.7%), indicating that alcohol consumption is highly associated with increased HCC risk. Alcohol abuse is known to be carcinogenic in humans and causes oxidative stress in hepatic cells, which play a pivotal role in the etiology of liver damage [45]. Chronic alcohol abuse accelerates hepatobiliary tumors by upregulating miR-122-mediated HIF-1α activity and stemness [46]. Interestingly, moderate alcohol intake altered autophagy- and apoptosis-signaling networks in a pig model [47]. Indeed, exposure to such carcinogens frequently altered genes at fragile sites, which led to the loss of WWOX suppressor function. Consistent with our data, patients with alcohol consumption had a higher risk of developing HCC. Moreover, in the current study, our result shown that SNP rs12918952 in WWOX conferred higher risk of vascular invasion, however, no difference was found regarding the HBsAg and anti-hepatitis C virus (Table 4). WWOX is known to regulate virus-associated immunodeficiency and various cancers, including HCC [9, 48–51]. Further investigation is warranted to explore the potential role of WWOX polymorphism and viral regulation of HCC progression.

WWOX, a protein bearing the WW domain, interacts with several proteins and plays a principle role in preventing tumorigenesis. Decreased expression or genetic alteration of WWOX has been detected in various malignant tumors. The influence of WWOX expression on the regulation of carcinogenesis, cell cycle, and apoptosis has also been recently reported [52–54]. However, these initial associations were not consistent with our expectation that the genetic variants rs73569323 (C1442T) and rs11545028 (C121T) would be significantly associated with a lower risk of HCC and tumor size. Furthermore, the 2 SNPs, C121T in the Kozak translation initiation site and C1442T in a closely micro-RNA target region in 3'-UTR, did not alter critical residues of the WW or SDR domain. Nevertheless, we have previously observed that C121T represents an oncogenic target for the translational dysregulation of WWOX expression in OSCC [55]. The clinicopathological implications of micro-RNA targeting the 3'-UTR region and the regulation of gene expression are well determined. Previously, genome-wide studies have investigated the link among WWOX genetic variations, such as SNPs and diseases, and have identified a cis-regulatory variation in the intron of WWOX [56, 57]. Our results suggest that the polymorphic variants C121T and C1442T seen in HCC are driven by potential enhancer elements within the noncoding regions rather than the variants in the protein-coding regions; this finding indicates that natural variants may be the key primary contributors to WWOX protein expression.

The aforementioned abnormality of WWOX expression contributes to HCC tumorigenesis, which may be associated with all-cause mortality, particularly in people with high AST and ALT levels [7, 58]. Moreover, serum α-fetoprotein level was found to be a pathological biomarker of inflammation and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B patients [59]. With regard to the clinical status, our results showed that compared with those who carried the CC genotype, the rs11545028 of patients who carried the CT or TT genotype was significantly correlated with low α-fetoprotein and ALT levels; this finding may be related to the cis-enhancing effect within the 5'-flanking region. However, α-fetoprotein levels are an independent predictor for the severity of inflammation and prognosis of HCC, even in chronic hepatitis B patients whose normal or low α-fetoprotein levels still indicated a severe condition [59, 60]. By contrast, the serum ASL and ALT levels in polymorphic rs3764340 are significantly higher in the CG+GG composition with CC. The rs3764340 SNP has been predicted to cause an alteration of the protein structure at codon 282 of WWOX, where an α-helix is disrupted, and this is associated with an elevated risk of developing multiple neoplasias, thereby reflecting the contribution of rs3764340 C>G substitution to high AST and ALT levels [35, 41, 42, 61]. According to these criteria, α-fetoprotein, AST, and ALT are promising biomarkers for the diagnosis of HCC on the basis of the genetic variations of WWOX rs11545028 and rs3764340.

In addition, we identified one synonymous variant, rs12918952, in exon 6, which was significantly associated with the vascular invasion of HCC. Further exploration using the GTEx dataset for liver tissue and expression quantitative trait loci analysis revealed that the rs12918952 A allele was associated with decreased WWOX expression. A clinical study of 101 primary bladder tumor samples demonstrated that the low expression of WWOX was correlated with advanced cancer stages and tumor progression [62]. A similar proportion of WWOX downregulation associated with aggressive phenotypes and poor prognosis has been observed in many cancers. Intriguingly, we showed that rs12918952 was mapped in the coding region near the typical coenzyme binding site within the SDR domain. Single-nucleotide substitution in coding or regulatory sequences affects the protein structure, and conformation has been demonstrated. To the best of our knowledge, no previous evidences have revealed that rs12918952 G>A substitution has the potential to modify the biological activity and protein stability of WWOX. Recently, the deletion of WWOX exon 6–8 was identified in lung cancer, resulting in a loss of the tumor suppressor function [63]. In the present study, the missense polymorphism rs12918952 G>A located in exon 6 conferred a decreased expression of WWOX, which is partially responsible for the higher vascular invasion of HCC. However, the direct testing of this hypothesis beyond the purpose of the current study is difficult. Nevertheless, it is a unique feature and warrants further investigation.

In conclusion, the present study reports a potential clinically significant finding that several variants of WWOX are associated with the clinical status and susceptibility of HCC. Although the clinical and pathological features differ among the various polymorphisms of WWOX, our findings still provide a deeper insight into the genetic variations. Additional bioinformative analyses should be conducted to evaluate the clinical utility of predicting the likelihood of patient susceptibility to HCC. Comprehensive variant detection and analysis are prerequisites for developing optimal therapeutic approaches that can eventually ameliorate the clinical phenotype in patients harboring the corresponding lesions.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by a grant (CSH-2016-C-016, CSH-2016-E-002-Y2) from Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taiwan. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray FI, Devesa SS. Cancer burden in the year 2000. The global picture. European journal of cancer. 2001;37 Suppl 8:S4–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Llovet JM, Di Bisceglie AM, Bruix J, Kramer BS, Lencioni R, Zhu AX, et al. Design and endpoints of clinical trials in hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100(10):698–711. 10.1093/jnci/djn134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. The New England journal of medicine. 1996;334(11):693–9. 10.1056/NEJM199603143341104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imamura H, Matsuyama Y, Tanaka E, Ohkubo T, Hasegawa K, Miyagawa S, et al. Risk factors contributing to early and late phase intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. Journal of hepatology. 2003;38(2):200–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamiyama T, Nakanishi K, Yokoo H, Kamachi H, Tahara M, Suzuki T, et al. Recurrence patterns after hepatectomy of hepatocellular carcinoma: implication of Milan criteria utilization. Annals of surgical oncology. 2009;16(6):1560–71. 10.1245/s10434-009-0407-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365(12):1118–27. 10.1056/NEJMra1001683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li YP, Wu CC, Chen WT, Huang YC, Chai CY. The expression and significance of WWOX and beta-catenin in hepatocellular carcinoma. APMIS: acta pathologica, microbiologica, et immunologica Scandinavica. 2013;121(2):120–6. 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2012.02947.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin J, Wang B, Huang AM, Wang XJ. [The relationship between FHIT and WWOX expression and clinicopathological features in hepatocellular carcinoma]. Zhonghua gan zang bing za zhi = Zhonghua ganzangbing zazhi = Chinese journal of hepatology. 2010;18(5):357–60. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2010.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park SW, Ludes-Meyers J, Zimonjic DB, Durkin ME, Popescu NC, Aldaz CM. Frequent downregulation and loss of WWOX gene expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma. British journal of cancer. 2004;91(4):753–9. Epub 2004/07/22. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Del Mare S, Salah Z, Aqeilan RI. WWOX: its genomics, partners, and functions. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2009;108(4):737–45. 10.1002/jcb.22298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang NS, Doherty J, Ensign A, Lewis J, Heath J, Schultz L, et al. Molecular mechanisms underlying WOX1 activation during apoptotic and stress responses. Biochemical pharmacology. 2003;66(8):1347–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aqeilan RI, Croce CM. WWOX in biological control and tumorigenesis. Journal of cellular physiology. 2007;212(2):307–10. 10.1002/jcp.21099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang NS. Bubbling cell death: A hot air balloon released from the nucleus in the cold. Experimental biology and medicine (Maywood, NJ). 2016;241(12):1306–15. Epub 2016/04/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo JY, Chou YT, Lai FJ, Hsu LJ. Regulation of cell signaling and apoptosis by tumor suppressor WWOX. Experimental biology and medicine (Maywood, NJ). 2015;240(3):383–91. Epub 2015/01/18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu LJ, Chiang MF, Sze CI, Su WP, Yap YV, Lee IT, et al. HYAL-2-WWOX-SMAD4 Signaling in Cell Death and Anticancer Response. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology. 2016;4:141 Epub 2016/12/22. 10.3389/fcell.2016.00141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abu-Remaileh M, Joy-Dodson E, Schueler-Furman O, Aqeilan RI. Pleiotropic Functions of Tumor Suppressor WWOX in Normal and Cancer Cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2015;290(52):30728–35. Epub 2015/10/27. 10.1074/jbc.R115.676346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aqeilan RI, Pekarsky Y, Herrero JJ, Palamarchuk A, Letofsky J, Druck T, et al. Functional association between Wwox tumor suppressor protein and p73, a p53 homolog. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(13):4401–6. 10.1073/pnas.0400805101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bednarek AK, Keck-Waggoner CL, Daniel RL, Laflin KJ, Bergsagel PL, Kiguchi K, et al. WWOX, the FRA16D gene, behaves as a suppressor of tumor growth. Cancer research. 2001;61(22):8068–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gourley C, Paige AJ, Taylor KJ, Scott D, Francis NJ, Rush R, et al. WWOX mRNA expression profile in epithelial ovarian cancer supports the role of WWOX variant 1 as a tumour suppressor, although the role of variant 4 remains unclear. International journal of oncology. 2005;26(6):1681–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guler G, Uner A, Guler N, Han SY, Iliopoulos D, Hauck WW, et al. The fragile genes FHIT and WWOX are inactivated coordinately in invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;100(8):1605–14. 10.1002/cncr.20137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aqeilan RI, Kuroki T, Pekarsky Y, Albagha O, Trapasso F, Baffa R, et al. Loss of WWOX expression in gastric carcinoma. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2004;10(9):3053–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nunez MI, Ludes-Meyers J, Abba MC, Kil H, Abbey NW, Page RE, et al. Frequent loss of WWOX expression in breast cancer: correlation with estrogen receptor status. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2005;89(2):99–105. 10.1007/s10549-004-1474-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pimenta FJ, Gomes DA, Perdigao PF, Barbosa AA, Romano-Silva MA, Gomez MV, et al. Characterization of the tumor suppressor gene WWOX in primary human oral squamous cell carcinomas. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2006;118(5):1154–8. 10.1002/ijc.21446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qin HR, Iliopoulos D, Semba S, Fabbri M, Druck T, Volinia S, et al. A role for the WWOX gene in prostate cancer. Cancer research. 2006;66(13):6477–81. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aqeilan RI, Trapasso F, Hussain S, Costinean S, Marshall D, Pekarsky Y, et al. Targeted deletion of Wwox reveals a tumor suppressor function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(10):3949–54. 10.1073/pnas.0609783104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nunez MI, Rosen DG, Ludes-Meyers JH, Abba MC, Kil H, Page R, et al. WWOX protein expression varies among ovarian carcinoma histotypes and correlates with less favorable outcome. BMC cancer. 2005;5:64 10.1186/1471-2407-5-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yendamuri S, Kuroki T, Trapasso F, Henry AC, Dumon KR, Huebner K, et al. WW domain containing oxidoreductase gene expression is altered in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer research. 2003;63(4):878–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iliopoulos D, Guler G, Han SY, Johnston D, Druck T, McCorkell KA, et al. Fragile genes as biomarkers: epigenetic control of WWOX and FHIT in lung, breast and bladder cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24(9):1625–33. 10.1038/sj.onc.1208398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garg R, Wollan M, Galic V, Garcia R, Goff BA, Gray HJ, et al. Common polymorphism in interleukin 6 influences survival of women with ovarian and peritoneal carcinoma. Gynecologic oncology. 2006;103(3):793–6. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.08.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yarden RI, Friedman E, Metsuyanim S, Olender T, Ben-Asher E, Papa MZ. MDM2 SNP309 accelerates breast and ovarian carcinogenesis in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers of Jewish-Ashkenazi descent. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2008;111(3):497–504. 10.1007/s10549-007-9797-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gu J, Ajani JA, Hawk ET, Ye Y, Lee JH, Bhutani MS, et al. Genome-wide catalogue of chromosomal aberrations in barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma: a high-density single nucleotide polymorphism array analysis. Cancer prevention research. 2010;3(9):1176–86. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agnelli L, Mosca L, Fabris S, Lionetti M, Andronache A, Kwee I, et al. A SNP microarray and FISH-based procedure to detect allelic imbalances in multiple myeloma: an integrated genomics approach reveals a wide gene dosage effect. Genes, chromosomes & cancer. 2009;48(7):603–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lange EM, Beebe-Dimmer JL, Ray AM, Zuhlke KA, Ellis J, Wang Y, et al. Genome-wide linkage scan for prostate cancer susceptibility from the University of Michigan Prostate Cancer Genetics Project: suggestive evidence for linkage at 16q23. The Prostate. 2009;69(4):385–91. 10.1002/pros.20891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su SC, Hsieh MJ, Liu YF, Chou YE, Lin CW, Yang SF. ADAMTS14 Gene Polymorphism and Environmental Risk in the Development of Oral Cancer. PloS one. 2016;11(7):e0159585 Epub 2016/07/28. 10.1371/journal.pone.0159585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo W, Dong Z, Dong Y, Guo Y, Kuang G, Yang Z. Genetic and epigenetic alterations of WWOX in the development of gastric cardia adenocarcinoma. Environmental and molecular mutagenesis. 2013;54(2):112–23. Epub 2012/12/01. 10.1002/em.21748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang D, Qiu F, Yang L, Li Y, Cheng M, Wang H, et al. The polymorphisms and haplotypes of WWOX gene are associated with the risk of lung cancer in southern and eastern Chinese populations. Molecular carcinogenesis. 2013;52 Suppl 1:E19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paige AJ, Taylor KJ, Taylor C, Hillier SG, Farrington S, Scott D, et al. WWOX: a candidate tumor suppressor gene involved in multiple tumor types. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(20):11417–22. Epub 2001/09/27. 10.1073/pnas.191175898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Consortium GT. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet. 2013;45(6):580–5. 10.1038/ng.2653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pazin MJ. Using the ENCODE Resource for Functional Annotation of Genetic Variants. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2015;2015(6):522–36. 10.1101/pdb.top084988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schirmer MA, Luske CM, Roppel S, Schaudinn A, Zimmer C, Pfluger R, et al. Relevance of Sp Binding Site Polymorphism in WWOX for Treatment Outcome in Pancreatic Cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2016;108(5). Epub 2016/02/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cancemi L, Romei C, Bertocchi S, Tarrini G, Spitaleri I, Cipollini M, et al. Evidences that the polymorphism Pro-282-Ala within the tumor suppressor gene WWOX is a new risk factor for differentiated thyroid carcinoma. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2011;129(12):2816–24. 10.1002/ijc.25937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo W, Wang G, Dong Y, Guo Y, Kuang G, Dong Z. Decreased expression of WWOX in the development of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Molecular carcinogenesis. 2013;52(4):265–74. 10.1002/mc.21853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen TH, Chen CJ, Yen MF, Lu SN, Sun CA, Huang GT, et al. Ultrasound screening and risk factors for death from hepatocellular carcinoma in a high risk group in Taiwan. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2002;98(2):257–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen CJ, Yu MW, Liaw YF. Epidemiological characteristics and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 1997;12(9–10):S294–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Urata Y, Yamasaki T, Saeki I, Iwai S, Kitahara M, Sawai Y, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of non-B non-C hepatocellular carcinoma patients with modest alcohol consumption. Hepatology research: the official journal of the Japan Society of Hepatology. 2016;46(5):434–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ambade A, Satishchandran A, Szabo G. Alcoholic hepatitis accelerates early hepatobiliary cancer by increasing stemness and miR-122-mediated HIF-1alpha activation. Scientific reports. 2016;6:21340 10.1038/srep21340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Potz BA, Lawandy IJ, Clements RT, Sellke FW. Alcohol modulates autophagy and apoptosis in pig liver tissue. The Journal of surgical research. 2016;203(1):154–62. 10.1016/j.jss.2016.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lan YY, Wu SY, Lai HC, Chang NS, Chang FH, Tsai MH, et al. WW domain-containing oxidoreductase is involved in upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase 9 by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 2A. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2013;436(4):672–6. Epub 2013/06/19. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fu J, Qu Z, Yan P, Ishikawa C, Aqeilan RI, Rabson AB, et al. The tumor suppressor gene WWOX links the canonical and noncanonical NF-kappaB pathways in HTLV-I Tax-mediated tumorigenesis. Blood. 2011;117(5):1652–61. Epub 2010/12/01. 10.1182/blood-2010-08-303073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chang NS. Introduction to a thematic issue for WWOX. Experimental biology and medicine (Maywood, NJ). 2015;240(3):281–4. Epub 2015/03/25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.He D, Zhang YW, Zhang NN, Zhou L, Chen JN, Jiang Y, et al. Aberrant gene promoter methylation of p16, FHIT, CRBP1, WWOX, and DLC-1 in Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinomas. Medical oncology (Northwood, London, England). 2015;32(4):92. Epub 2015/02/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yan H, Tong J, Lin X, Han Q, Huang H. Effect of the WWOX gene on the regulation of the cell cycle and apoptosis in human ovarian cancer stem cells. Molecular medicine reports. 2015;12(2):1783–8. 10.3892/mmr.2015.3640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li G, Sun L, Mu Z, Huang Y, Fu C, Hu B. Ectopic WWOX Expression Inhibits Growth of 5637 Bladder Cancer Cell In Vitro and In Vivo. Cell biochemistry and biophysics. 2015;73(2):417–25. 10.1007/s12013-015-0654-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ekizoglu S, Bulut P, Karaman E, Kilic E, Buyru N. Epigenetic and genetic alterations affect the WWOX gene in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. PloS one. 2015;10(1):e0115353 Epub 2015/01/23. 10.1371/journal.pone.0115353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheng HL, Liu YF, Su CW, Su SC, Chen MK, Yang SF, et al. Functional genetic variant in the Kozak sequence of WW domain-containing oxidoreductase (WWOX) gene is associated with oral cancer risk. Oncotarget. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stranger BE, Nica AC, Forrest MS, Dimas A, Bird CP, Beazley C, et al. Population genomics of human gene expression. Nature genetics. 2007;39(10):1217–24. 10.1038/ng2142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pennacchio LA, Ahituv N, Moses AM, Prabhakar S, Nobrega MA, Shoukry M, et al. In vivo enhancer analysis of human conserved non-coding sequences. Nature. 2006;444(7118):499–502. 10.1038/nature05295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wen CP, Lin J, Yang YC, Tsai MK, Tsao CK, Etzel C, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma risk prediction model for the general population: the predictive power of transaminases. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2012;104(20):1599–611. 10.1093/jnci/djs372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu YR, Lin BB, Zeng DW, Zhu YY, Chen J, Zheng Q, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein level as a biomarker of liver fibrosis status: a cross-sectional study of 619 consecutive patients with chronic hepatitis B. BMC gastroenterology. 2014;14:145 10.1186/1471-230X-14-145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mizejewski GJ. Alpha-fetoprotein structure and function: relevance to isoforms, epitopes, and conformational variants. Experimental biology and medicine. 2001;226(5):377–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang N, Jiang Z, Ren W, Yuan L, Zhu Y. Association of polymorphisms in WWOX gene with risk and outcome of osteosarcoma in a sample of the young Chinese population. OncoTargets and therapy. 2016;9:807–13. 10.2147/OTT.S99106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ramos D, Abba M, Lopez-Guerrero JA, Rubio J, Solsona E, Almenar S, et al. Low levels of WWOX protein immunoexpression correlate with tumour grade and a less favourable outcome in patients with urinary bladder tumours. Histopathology. 2008;52(7):831–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03033.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhou Y, Xu Y, Zhang Z. Deletion and mutation of WWOX exons 6–8 in human non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology Medical sciences = Hua zhong ke ji da xue xue bao Yi xue Ying De wen ban = Huazhong keji daxue xuebao Yixue Yingdewen ban. 2005;25(2):162–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.