Abstract

The patient was a 66-year-old woman, G2P2. The patient presented a chief complaint of irregular postmenopausal bleeding 1 month ago. A transvaginal ultrasonography showed that bilateral ovaries were not enlarged and uterine endometrium was thickened, measuring at 9 mm. As a result of endometrial curettage, the simple endometrial hyperplasia was revealed. A blood examination showed an elevated estradiol level of 67 pg/mL, an elevated level of testosterone 0.64 ng/mL, and a slightly suppressed follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level of 34.86 mIU/mL. We conducted laparoscopic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy because the patient strongly suggested less invasive surgery. The result of pathological diagnosis was Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor (SLCT) in moderately differentiation. A blood examination after a month postoperatively revealed an elevated FSH level of 85.59 mIU/mL, depressed estradiol level of less than 10 pg/mL, and testosterone level of less than 0.03 ng/mL. There was no evidence of recurrence in the first year of follow-up.

Keywords: Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor (SLCT), endometrial hyperplasia, postmenopausal woman

Introduction

A Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor (SLCT) is an extremely rare type of sex cord stromal tumor of the ovary. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors mainly secrete testosterone, and manifestations of virilization may appear.

We present a case with simple endometrial hyperplasia in a postmenopausal woman, which was proved an ovarian SLCT after laparoscopic surgery. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors, which are associated with hyperestrogenism, are very rare in postmenopausal women.

Case

The patient was a 66-year-old woman, G2P2. Menopause occurred at the age of 52. She was presented with irregular postmenopausal bleeding 1 month ago. There were no virilization and defeminization symptoms in this patient.

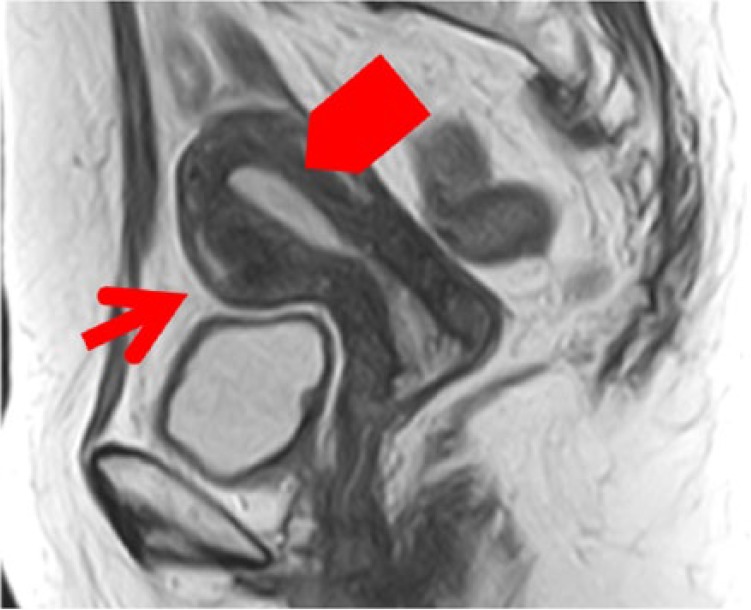

A transvaginal ultrasonography revealed that her uterus had 2 small myomas with a maximum size of 3 cm. Bilateral ovaries were not enlarged. Uterine endometrium was thickened, measuring at 9 mm. A pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed the same image as endometrial thickening and uterine myomas (Figure 1). An abdominal computed tomographic scan detected no adrenal lesions. Uterine cervical cytology was diagnosed negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (NILM), and endometrial cytology was diagnosed negative. As a result of endometrial curettage, the simple endometrial hyperplasia was revealed.

Figure 1.

T2 of MRI (myoma [→] endometrial thickening [ ]). MRI indicates magnetic resonance imaging.

]). MRI indicates magnetic resonance imaging.

A blood examination revealed an elevated estradiol level of 67 pg/mL, an elevated level of testosterone 0.64 ng/mL, and a slightly suppressed follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level of 34.86 mIU/mL (Table 1). She took medicine for hypertension and lumbago and denied any use of supplements. Although we strongly suspected she had hormone-producing tumor, the image examination did not detect any adrenal tumor or ovarian tumor. We presented hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy as a diagnostic treatment. She did not agree it. We decided on a policy of observation and conducted ultrasonography, endometrial cytology, and blood tests, including hormone level, every 3 months. The endometrial thickness shifted between 5 and 10 mm as a result of ultrasonography inspection. We did not find enlarged ovaries. The hormone levels were almost the same as initial visit.

Table 1.

Hormone blood concentration.

| Normal (postmenopausal woman) | Ordinary SLCTs | This case | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol, pg/mL | <20 | High (rare) | 67 |

| Testosterone, ng/mL | 0.12-0.31 | High | 0.64 |

| FSH, mIU/mL | 75-200 | Low | 34.86 |

Abbreviations: FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; SLCTs, Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors.

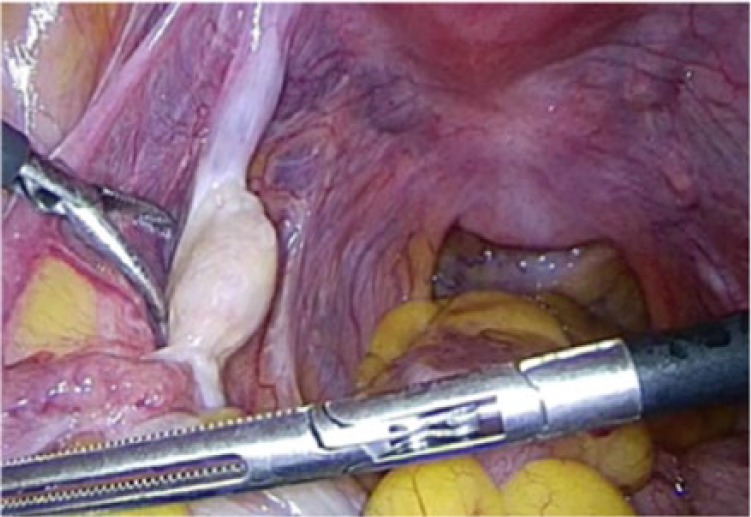

One year later after initial visit, the patient selected surgical operation. We planned laparoscopic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy because she requested a less invasive surgery. The operation was completed under general anesthesia and was performed with a 10 mm telescope through the trocar located in the umbilicus. The position of other trocars was in the bilateral lateral region of abdomen, 5 mm in size, and on the left side of the umbilicus, 10 mm in size. The maximum insufflating abdominal pressure was 10 mmHg. We decided laparoscopic surgery was possible for intraoperative findings with no adhesion in the abdominal cavity. The omentum and peritoneum were normal. There was no ascites. The size of uterus and ovaries did not atrophy for her age. Bilateral ovarian surface was smooth without macroscopic aspect of malignancy (Figures 2 and 3). The uterus and bilateral adnexa were removed from the vagina by an endoscopic bag. The operation took 1 hour 43 minutes. The amount of bleeding was 10 g. The uterus and bilateral adnexa weighed 100 g (Figure 4). The left ovarian surface was smooth without macroscopic aspect of malignancy. The section of the left ovary revealed a yellow, solid tumor with a diameter of 12 mm (Figure 5). The endometrium thickened and did not show an apparent formation of tumor.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative finding (no tumor was found in the right ovary).

Figure 3.

Intraoperative finding (no tumor was found in the left ovary).

Figure 4.

Macroscopic finding (ovaries did not atrophy).

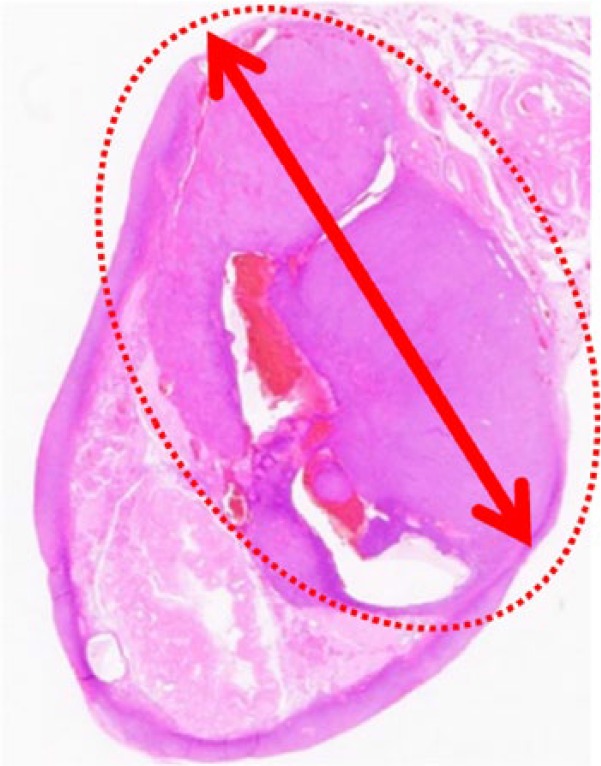

Figure 5.

The cut surface of the tumor (ο) (the tumor of 12 mm in diameter) (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×1).

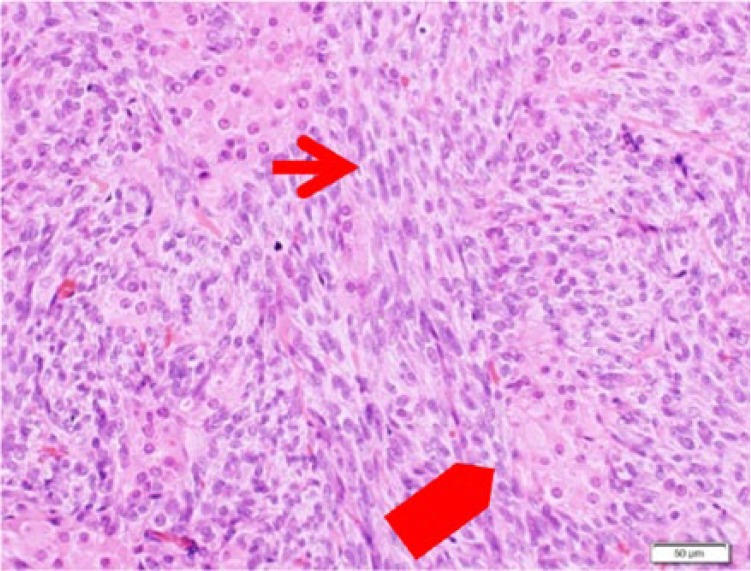

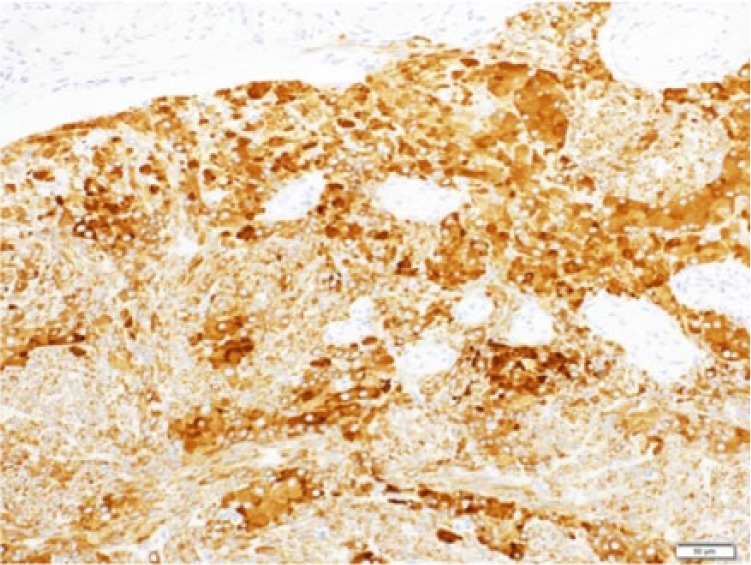

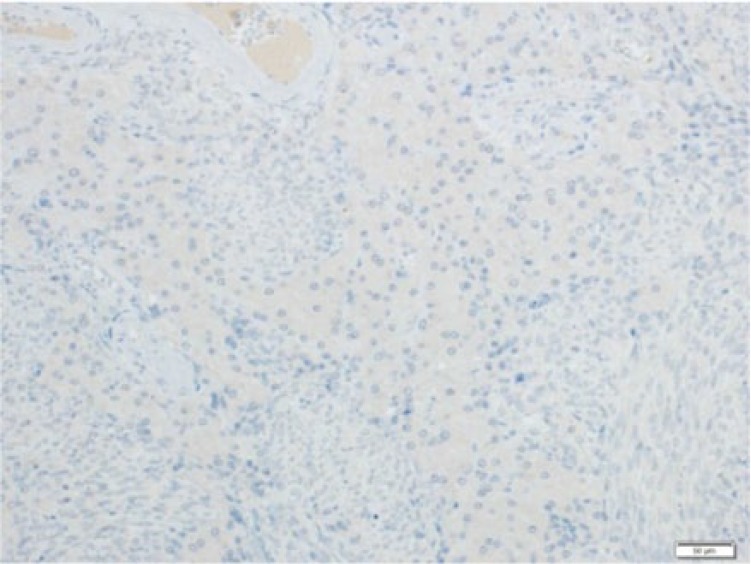

Microscopically, the left ovarian tumor showed Sertoli cells densely disarraying with spindle-shaped nucleus. The cluster of Leydig cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm was identified between the cord of Sertoli cells (Figure 6 and 7). Immunohistochemical studies showed that the Sertoli cells and the Leydig cells were positive for α-inhibin (Figure 8). The source and dilution of antibody of α-inhibin used for immunohistochemistry were Dako, Santa Clara, CA, United States (Monoclonal Mouse Anti-Human Inhibin α Cone R1, ×20; Figure 9). There were 7 mitotic figures per high-power field. The final diagnosis was a moderately differentiated Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor of the left ovary. The right ovary did not indicate histological abnormality. In the endometrium, irregularly distributed proliferative-type glands with slightly enlarged nucleus were widely separated by active cellular stroma. The endometrium was diagnosed as simple endometrial hyperplasia with the endometrial gland.

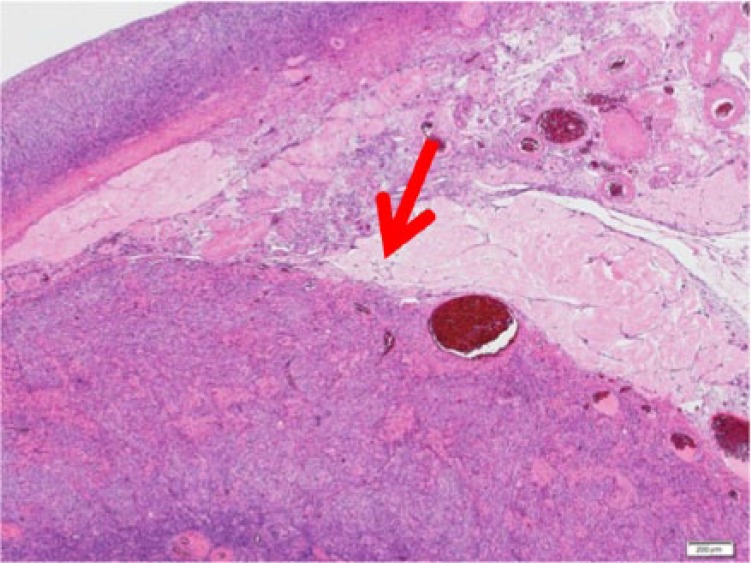

Figure 6.

The tumor (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×4).

Figure 7.

Sertoli cell (→), Leydig cell ( ) (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×10)

) (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×10)

Figure 8.

Immunohistochemical analysis for the Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor (positive stain of α-inhibin in Sertoli cell and Leydig cell; original magnification ×20).

Figure 9.

Negative control in immunohistochemical hematoxylin-eosin (original magnification ×20).

Her postoperative course was uneventful and was discharged on the fourth day after surgery. moderately differentiated Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor is a classified malignancy in World Health Organization Histologic Classification. The stage of the patient was estimated stage IA, though completed surgical staging was not performed. Stage I SLCTs have a good prognosis. We determined to observe cautiously on sufficient informed consent.

Laboratory examination after a month postoperatively revealed an elevated FSH level of 85.59 mIU/mL, a depressed estradiol level less than 10 pg/mL, and a testosterone level less than 0.03 ng/mL. There was no evidence of recurrence in the first year of follow-up.

Discussion

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors are extremely rare neoplasms, accounting for only approximately 1% of sex cord stromal tumors, less than 0.2% of all primary ovarian neoplasms, and unilateral in 98% of patients.1 Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors are most commonly presented in young woman, with an average age of 25.2 It is rare, less than 10%, to find these neoplasms prior to menarche and after menopause. The pathognomonic symptom of this disease is an endocrine manifestation, and more than half of the patients have the symptom.2 Virilization and defeminization have been described in up to 77% of the cases.3 These symptoms are principally due to testosterone produced by the tumor. Testosterone is secreted directly by the Leydig cells. Some researchers said that Sertoli cells were capable of producing testosterone.3 These clinical signs and symptoms include oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea, hirsutism, breast atrophy, acne, lower tone of voice, laryngeal protuberance, and clitoromegaly.2 When the total value of testosterone exceeded 2 ng/mL, there was obvious evidence of virilization.3

Another kind of presentation could be with estrogenic manifestations, which are rare, such as postmenopausal bleeding, endometrial hyperplasia, myoma, endometrial carcinoma, and breast cancer. It is presumed that the Sertoli cells might secrete estrogens. Also, testosterone secreted by the tumor might be converted to estrogen in follicular cells or peripherally through the aromatase cytochrome P450.2 In this case, as estrogen elevated dominantly over testosterone, Sertoli cells might produce estrogen directly.

The presence of elevated androgens with normal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and a negative dexamethasone suppression test are characteristics of an ovarian origin of the virilization.2

Macroscopically, most SLCTs range in size between 5 and 15 cm in diameter. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors can be solid, cystic, or mixture of them.4 Imaging such as ultrasound, CT, and MRI are useful for diagnosis. The best imaging test for ovarian tumors is ultrasound, and color Doppler is used to characterize SLCTs because these tumors tend to be well vascularized. Computed tomographic scans of SLCTs show a well-defined mass. In T2 of MR images, the tumor has low signal intensity reflecting the fibrous stroma.5 About 20% of the SLCTs cannot be determined because of their small size.

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors are divided into the following types such as well differentiated, moderately differentiated, poorly differentiated, with a retiform pattern, with heterologous elements (mucoprotein, focal carcinoid elements, cartilage, etc), and mixed. It is considered in general that all the well differentiated tumors are benign, and tumors other than well differentiated and tumors with retiform or heterologous elements pattern can behave in a malignant manner.5

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors with heterologous elements are present in 20%, presenting in some intermediate or poorly differentiated SLCTs. They are admitted predominantly as cystic tumor.5

Zhao et al6 mentioned that inhibin and calretinin were the most useful immunohistochemical markers of sex cord stromal tumors, which could help differentiate SLCTs from other malignancies.

Surgery is the gold standard treatment for SLCTs. For woman without the desire of fertility, total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy or cytoreductive operation should be recommended. The unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy could be performed in the early stages for young patients who hope for fertility preservation.7 The necessity of pelvic lymphadenectomy is controversial. Brown et al8 suggested that lymph node involvement in SLCTs of the ovary is extremely rare, while routine pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy could be safely omitted for SLCTs.

In this case, there was not a decisive factor to conduct surgical therapy. In addition, the patient did not agree to diagnostic surgery for 1 year. The result of pathological diagnosis was moderately differentiated SLCTs, which is a classified malignancy. In principle, earlier surgery was desired. Nevertheless, preoperative diagnosis is often difficult. The average term from the first consultation to the determined diagnosis after operation was about 15 months (range: 7-25 months).7

Laparoscopic surgery was conducted in this case because the patient desired less invasive surgery without precise preoperative diagnosis. Laparoscopic surgery offers several established advantages, such as less bleeding, less trauma, less risk of incisional hernias and postoperative infection, and quicker and less painful recovery.9 Although various reports have shown that intraoperative capsule rupture of ovarian cancer does not lead to a poor prognosis, minimal access surgery is more likely than laparotomy to result in capsular rupture to achieve adequate working space and to retrieve specimen.10 Furthermore, there are risks of the dissemination of cancer cells affected by pneumoperitoneum and port site metastases, which is less than 1.4%.1

Ovarian SLCTs are rare, and reports of laparoscopic surgery for them are few. More research is needed to determine whether laparoscopy might be a tool as radical operation. However, laparoscopy could be a useful means for observation in the peritoneal cavity and performing biopsies.

Conclusions

When we encounter patients with symptoms of virilization and defeminization, or hyperestrogenism as postmenopausal bleeding, measuring the androgen and estrogen levels is recommended as a routine diagnostic procedure. The elevated levels are sometimes the only preoperative cue to diagnose this tumor. Even when the site of tumor cannot be found by image inspection, it is necessary to keep in mind that a small tumor may be present for early diagnosis and treatment.

Footnotes

Peer Review:Five peer reviewers contributed to the peer review report. Reviewers’ reports totaled 1154 words, excluding any confidential comments to the academic editor.

Funding:The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to the manuscript sufficiently to justify their inclusion as authors and take full responsibility for its contents.

References

- 1. Litta P, Saccardi C, Conte L, Codroma A, Angioni S, Mioni R. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors: current status of surgical management: literature review and proposal of treatment. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29:412–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moghazy D, Sharan C, Nair M, et al. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor with unique nail findings in a post-menopausal woman: a case report and literature review. J Ovarian Res. 2014;7:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xiao H, Li B, Zuo J, et al. Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor: a report of seven cases and a review of the literature. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29:192–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen L, Tunnell CD, De Petris G. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor with heterologous element: a case report and a review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:1176–1181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cabrera-Cantú F, Urrutia-Osorio M, Valdez-Arellano F, Rivadeneyra-Espinoza L, Papaqui A, Soto-Vega E. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor in a 12-year-old girl: a review article and case report. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;290:791–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhao C, Vinh TN, McManus K, Dabbs D, Barner R, Vang R. Identification of the most sensitive and robust immunohistochemical markers in different categories of ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:354–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gui T, Cao D, Shen K, et al. A clinicopathological analysis of 40 cases of ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127:384–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brown J, Sood AK, Deavers MT, Milojevic L, Gershenson DM. Patterns of metastasis in sex cord-stromal tumors of the ovary: can routine staging lymphadenectomy be omitted? Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113:86–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kriplani A, Agarwal N, Roy KK, Manchanda R, Singh MK. Laparoscopic management of Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors of the ovary. A report of two cases. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cromi A, Bogani G, Uccella S, Casarin J, Serati M, Ghezzi F. Laparoscopic fertility-sparing surgery for early stage ovarian cancer: a single-centre case series and systematic literature review. J Ovarian Res. 2014;7:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]