Abstract

Background and purpose:

Etiologic role, incidence, demographic, and response-to-treatment characteristics of urinary tract infection (UTI) among neonates, its relationship with significant neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, and abnormalities of the urinary system were studied in a prospective investigation in early (≤10 days) idiopathic neonatal jaundice in which all other etiologic factors of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia were ruled out.

Patients and methods:

Urine samples for microscopic and bacteriologic examination were obtained with bladder catheterization from 155 newborns with early neonatal jaundice. Newborns with a negative urine culture and with a positive urine culture were defined as group I and group II, respectively, and the 2 groups were compared with each other.

Results:

The incidence of UTI in whole of the study group was 16.7%. Serum total and direct bilirubin levels were statistically significantly higher in group II when compared with group I (P = .005 and P = .001, respectively). Decrease in serum total bilirubin level at the 24th hour of phototherapy was statistically significantly higher in group I compared with group II (P = .022).

Conclusions:

Urinary tract infection should be investigated in the etiologic evaluation of newborns with significant hyperbilirubinemia. The possibility of UTI should be considered in jaundiced newborns who do not respond to phototherapy well or have a prolonged duration of phototherapy treatment.

Keywords: Newborn, early jaundice, urinary tract infection, significant hyperbilirubinemia

Introduction

Indirect (unconjugated) hyperbilirubinemia, which is seen in 60% to 80% of newborns in the first days of life, may be one of the first signs of a serious bacterial infection.1 This type of jaundice may reportedly be an important and even the first presenting sign of urinary tract infection (UTI).2 The physiopathologic relationship between neonatal jaundice and UTI has always gained much interest and recently been investigated in various studies. However, this relationship has been preferably studied in newborns with late (≥8 days) jaundice,3–6 prolonged jaundice (≥15 days),5,7–9 or conjugated hyperbilirubinemia,5 and only few studies among newborns with early (≤7 days) jaundice have been conducted.2,10,11 Currently, authorized international institutions, such as American Academy of Pediatrics, do not recommend investigation of UTI with urinalysis or urine culture as part of investigations for the etiology of either early or late/prolonged neonatal jaundice.12

In this study, etiologic role, prevalence, demographic, and response-to-treatment characteristics of UTI among neonates, its relationship with significant neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, and abnormalities of the urinary system were studied in a prospective investigation in early (≤10 days) idiopathic neonatal jaundice in which all other etiologic factors of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia were ruled out.

Patients and Methods

This study was conducted at the Division of Neonatology, Department of Pediatrics of Ufuk University Faculty of Medicine between June 2015 and August 2016. All newborns who were diagnosed with significant hyperbilirubinemia and required phototherapy treatment were included in the study. With the aim to determine whether UTI was the cause of pathologic jaundice, urine samples for microscopic and bacteriologic examination were obtained via bladder catheterization in all cases.

The diagnosis of significant hyperbilirubinemia was made considering gestational and postnatal age and risk factors of the newborns,12,13 and these cases were put on phototherapy. Late preterm, early term, and term newborns were included in the study, and newborns with a gestational age of less than 35 weeks were not included as the prematurity itself is a major risk factor in the etiology of hyperbilirubinemia.

As the primary aim of the study was to determine whether UTI itself was the leading cause in the etiology of significant hyperbilirubinemia, newborns with isoimmunization (ABO, Rh, or subgroup incompatibilities), direct Coombs test positivity, findings of hemolysis on blood smear (anisocytosis, spherocytosis, polychromasia, poikilocytosis), anemia, reticulocytosis, and/or glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency were excluded from the study. Other exclusion criteria were the presence of any major congenital anomaly, respiratory distress, and clinical or culture-proven sepsis.

The study was conducted according to clinical practice guidelines and approved by the local ethics committee. Informed consent was obtained from any parents of each patient. Parents were questioned in detail regarding their baby’s clinical signs and symptoms other than jaundice, such as fever, lethargy, irritability, diarrhea, feeding intolerance (poor feeding, vomiting), poor weight gain, or dirty skin color (poor tissue perfusion).

In all cases (diagnosed to have significant hyperbilirubinemia), sex; birth weight; route of delivery; maternal age; gestational age; postnatal age (as hours) on admission; weight on admission; weight loss as percent in comparison with birth weight; abnormal weight loss defined as the loss of body weight more than 7% and 12% on the fourth and seventh days of life, respectively14; feeding pattern; whether there was enclosed hemorrhage; blood groups and Rh types in mother-infant pairs; hemoglobin and hematocrit levels; number of white blood cells; ratio of immature-to-total neutrophils on peripheral blood smear; results of reticulocyte count and direct antiglobulin test; level of C-reactive protein; serum total and direct bilirubin levels measured with colorimetric method (diazotized sulfanilic acid reaction; Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany); renal function tests (blood urea nitrogen and creatinine); free T4 and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels; results of blood gases examination, if needed; glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase levels; whether there was any growth in urine culture and types and amounts of microorganism(s); and results of microscopic examination of urine (whether pyuria was present or not) were recorded. No further detailed tests were done toward demonstrating the etiology of hyperbilirubinemia in newborns with both significant hyperbilirubinemia and UTI.

Bladder catheterization was performed with aseptic technique after feeding and fixation of the infant. In all cases in whom phototherapy was started, serum total and direct bilirubin levels were measured at the 24th hour of phototherapy to evaluate the response to treatment and make the decision to stop treatment, and decrease in serum total bilirubin levels at the 24th hour of phototherapy was recorded as percentage decrease. Urine samples were sent immediately to microbiology laboratory for standard quantitative culture, and growth of single type microorganism on culture medium with an amount of at least 1000 CFU/mL was accepted as UTI.15 Renal ultrasonography was performed on all newborns with UTI, and voiding cystoureterography (after obtaining a sterile urine culture, approximately 1 month after the diagnosis) and dimercaptosuccinic acid scintigraphy (3 months after the diagnosis) were performed on those with any abnormality on renal ultrasonography.

In the initial analysis of the data prevalence of UTI as the cause of significant hyperbilirubinemia was determined. Later on, newborns with significant hyperbilirubinemia but without UTI and newborns with both significant hyperbilirubinemia and UTI were classified as group I and group II, respectively, and these groups were compared regarding demographic, laboratory, radiological, and microbiological characteristics.

SPSS 18.0 program was used in statistical analysis of data. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used in determining normal distribution. Nominal values, such as sex, route of delivery, presence or absence of pyuria, and feeding pattern, were compared with χ2 and Fisher exact χ2 tests. Of continuously variable parameters, gestational age, age on admission, and serum direct (conjugated) bilirubin levels were compared with Mann-Whitney U test, and maternal age, birth weight, weight on admission, levels of serum total bilirubin, free T4, TSH, hemoglobin, hematocrit, and serum bilirubin at 24th hour were compared with independent sample t test. Decrease in serum total bilirubin level at 24th hour calculated as percent was compared between the groups using Mann-Whitney U test. Values were given as mean ± SD. A P value of ≤.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The study was started with 188 newborns. However, parents of 12 newborns did not want to participate in the study, 21 newborns were excluded as they had exclusion criteria, and a total of 155 newborns with significant hyperbilirubinemia were finally included in the study during the study period. Mean gestational age and age on admission of these newborns were 37.7 ± 1.5 weeks and 126.6 ± 58.8 hours, respectively. Mean birth weight and weight on admission were 3141.1 ± 499.7 and 2978.3 ± 462.1 g, respectively, and weight loss on admission was −5.11 ± 3.64%. On admission, serum total and direct bilirubin levels were 18.55 ± 2.98 and 0.56 ± 0.15 mg/dL, respectively, and serum total bilirubin level at the 24th hour of phototherapy was 9.03 ± 1.54 mg/dL with a 51.2 ± 3.96% decrease. In all these cases, phototherapy was administered, and no other treatment modalities, such as exchange transfusion and intravenous immunoglobulin administration, were needed.

Urinary tract infection was detected in 26 (16.7%) of the 155 newborns included. Of these, 3 (11.5%) and 23 (88.5%) were women and men, respectively, and causative agents were Klebsiella spp. (8 of 26: 30.76%), Enterococcus spp. (7 of 26: 26.92%), Staphylococcus spp. (6 of 26: 23.07%), Escherichia coli (4 of 26: 15.38%), and Streptococcus spp. (1 of 26: 3.84%). None of the cases with UTI was circumcised. On ultrasonographic examination, an abnormality was detected in 7 (26.9%) of the 26 newborns diagnosed to have UTI, although most of these were benign in nature; 6 of these 7 newborns were men, and no vesicoureteral reflux of grade ≥3 or renal scar was detected in any of these patients. Demographic and laboratory characteristics of newborns with significant hyperbilirubinemia and diagnosed to have UTI are given in Table 1, and characteristics of patients with renal ultrasonographic abnormality are given in the second half of the table.

Table 1.

Demographic and laboratory characteristics of newborns with significant hyperbilirubinemia and diagnosed to have urinary tract infection (n = 26).

| Case | Age ON admission, h | Birth weight, g | Sex | Growing microorganism on urine culture and its amount, CFU/mL | SERUM TOTAL BILIRUBIN, MG/DLa | Abnormality on renal ultrasonography |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 126 | 2910 | Male | 100 000 Staphylococcus | 19.9 | Normal |

| 6 | 162 | 2110 | Male | 50 000 Klebsiella spp. | 15.2 | Normal |

| 7 | 120 | 3260 | Female | 10 000 Escherichia coli | 23.9 | Normal |

| 8 | 78 | 3260 | Male | 100 000 Enterococcus | 17.4 | Normal |

| 10 | 79 | 3450 | Male | 10 000 E coli | 24.1 | Normal |

| 11 | 236 | 2500 | Male | 100 000 E coli | 18 | Normal |

| 12 | 122 | 3150 | Male | 20 000 Staphylococcus | 20 | Normal |

| 14 | 48 | 3770 | Male | 100 000 Staphylococcus | 17.9 | Normal |

| 15 | 96 | 3370 | Male | 50 000 Enterococcus | 19.6 | Normal |

| 16 | 152 | 3850 | Male | 50 000 Klebsiella spp. | 19.9 | Normal |

| 17 | 107 | 4000 | Male | 100 000 Staphylococcus | 21.4 | Normal |

| 18 | 54 | 3700 | Female | 30 000 Streptococcus | 13.4 | Normal |

| 19 | 162 | 4160 | Male | 30 000 Enterococcus | 24.9 | Normal |

| 20 | 216 | 2000 | Male | 100 000 Klebsiella spp. | 20.6 | Normal |

| 22 | 76 | 3200 | Male | 100 000 Enterococcus | 20.2 | Normal |

| 23 | 176 | 3600 | Male | 100 000 Klebsiella spp. | 17.3 | Normal |

| 24 | 98 | 3200 | Male | 50 000 Klebsiella spp. | 23 | Normal |

| 25 | 66 | 3530 | Male | 100 000 Staphylococcus | 16.1 | Normal |

| 26 | 144 | 3150 | Male | 100 000 Enterococcus | 19.5 | Normal |

| 1 | 239 | 2830 | Female | 30 000 Klebsiella spp. | 20.7 | Left pelviectasis |

| 3 | 99 | 3680 | Male | 100 000 Klebsiella spp. | 18.4 | Unilateral cortical cyst |

| 4 | 168 | 3240 | Male | 100 000 Enterococcus | 24.7 | Left pelviectasis |

| 5 | 121 | 4170 | Male | 100 000 Klebsiella spp. | 20.6 | Minimal dilatation in bilateral renal pelvises |

| 9 | 96 | 3060 | Male | 100 000 E coli | 23.3 | Left hydronephrosis |

| 13 | 119 | 3900 | Male | 30 000 Staphylococcus | 23.7 | Bilateral pelviectasis |

| 21 | 40 | 3690 | Male | 100 000 Enterococcus | 18.4 | Right renal solid cyst |

1 mg/dL bilirubin = 17.1 µmol/L bilirubin.

Detailed clinical signs and symptoms, laboratory abnormalities, and treatment modalities of newborns with both significant hyperbilirubinemia and UTI are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Detailed clinical signs and symptoms, laboratory abnormalities, and treatment modalities of newborns with both significant hyperbilirubinemia and urinary tract infection (n = 26).

| Case | Complaints (of the parents) and positive clinical signs and symptoms | Positive laboratory abnormalities | Repeat (control) culture (urine/blood)a | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fever, jaundice | Blood culture + pyuria (46 white blood cell per HPF), high serum bilirubin level (20.7 mg/dL) | Sterile | Teicoplanin IV |

| 2 | Feeding intolerance, jaundice | High BUN/Cre (50 mg/dL/0.7 mg/dL), high serum bilirubin level (19.9 mg/dL) | Sterile | Cefotaxime IV + FR |

| 3 | Jaundice | High serum bilirubin level (18.4 mg/dL) | Sterile | Cefotaxime IV |

| 4 | Jaundice | Pyuria (22 white blood cell per HPF), high serum bilirubin level (24.7 mg/dL) | Sterile | Teicoplanin IV |

| 5 | Jaundice | High serum bilirubin level (20.6 mg/dL) | Sterile | Cefotaxime IV |

| 6 | Feeding intolerance, jaundice | High serum bilirubin level (15.2 mg/dL) | Sterile | Cefotaxime IV |

| 7 | Jaundice | High serum bilirubin level (23.9 mg/dL) | Sterile | Teicoplanin IV |

| 8 | Fever, jaundice | High CRP level (24.1 mg/dL), high I/T ratio (0.4), high serum bilirubin level (17.4 mg/dL) | Sterile | Teicoplanin IV |

| 9 | Jaundice | High serum bilirubin level (23.3 mg/dL) | Sterile | Teicoplanin IV |

| 10 | Poor weight gain, jaundice | High BUN/Cre (60 mg/dL/0.8 mg/dL), high serum bilirubin level (24.1 mg/dL) | Sterile | Cefotaxime IV + FR |

| 11 | Jaundice | High serum bilirubin level (18 mg/dL) | Sterile | Teicoplanin IV |

| 12 | Jaundice | High serum bilirubin level (20 mg/dL) | Sterile | Teicoplanin IV |

| 13 | Lethargy + irritability, jaundice | High serum bilirubin level (23.7 mg/dL) | Sterile | Teicoplanin IV |

| 14 | Jaundice | High serum bilirubin level (17.9 mg/dL) | Sterile | Cefotaxime IV |

| 15 | Jaundice | High serum bilirubin level (19.6 mg/dL) | Sterile | Teicoplanin IV |

| 16 | Diarrhea, jaundice | High serum bilirubin level (19.9 mg/dL) | Sterile | Cefotaxime IV |

| 17 | Jaundice | High serum bilirubin level (21.4 mg/dL) | Sterile | Cefotaxime IV |

| 18 | Poor tissue perfusion, jaundice | Metabolic acidosis (pH: 7.23/HCO3: 12.4), high serum bilirubin level (13.4 mg/dL) | Sterile | Teicoplanin IV + FR |

| 19 | Jaundice | High serum bilirubin level (24.9 mg/dL) | Sterile | Teicoplanin IV |

| 20 | Jaundice | High serum bilirubin level (20.6 mg/dL) | Sterile | Cefotaxime IV |

| 21 | Jaundice | High serum bilirubin level (18.4 mg/dL) | Sterile | Cefotaxime IV |

| 22 | Fever, jaundice | High CRP level/leukocytosis (44.1 mg/dL/17 800/mm3), high serum bilirubin level (20.2 mg/dL) | Sterile | Teicoplanin IV |

| 23 | Jaundice | High serum bilirubin level (17.3 mg/dL) | Sterile | Cefotaxime IV |

| 24 | Jaundice | High serum bilirubin level (23 mg/dL) | Sterile | Cefotaxime IV |

| 25 | Jaundice | Pyuria (17 white blood cell per HPF), high serum bilirubin level (16.1 mg/dL) | Sterile | Teicoplanin IV |

| 26 | Jaundice | High serum bilirubin level (19.5 mg/dL) | Sterile | Teicoplanin IV |

Abbreviations: BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cre, creatinine; CRP, C-reactive protein; FR, fluid replacement; HPF, high-power field; I/T, immature-to-total neutrophils; IV, intravenously.

Cerebrospinal fluid cultures were not required after evaluating the newborn’s general condition and other laboratory test results. Repeat (control) urine and blood cultures were obtained after completion of treatment.

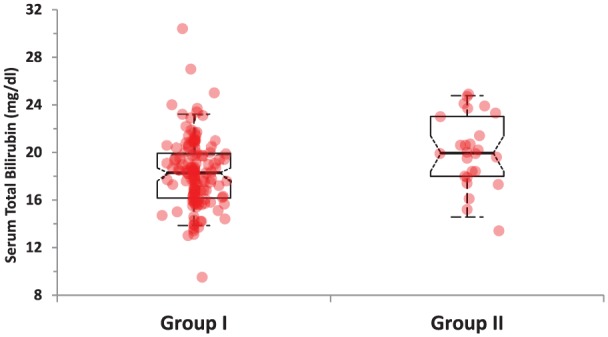

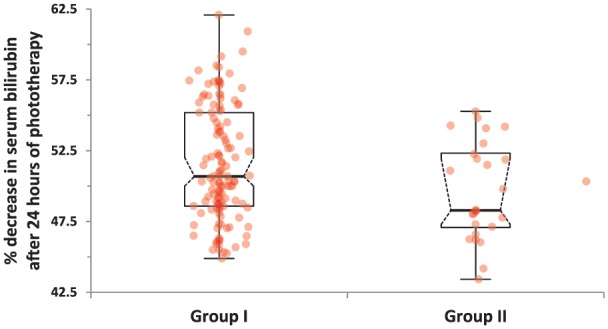

Comparison of demographic and laboratory characteristics of newborns with significant hyperbilirubinemia but without UTI (group I) and of newborns with both significant hyperbilirubinemia and UTI (group II) is given in Table 3. There were no statistically significant differences between the 2 groups regarding gestational age, maternal age, age on admission, birth weight, weight on admission, abnormal weight loss, hemoglobin and hematocrit levels, route of delivery, feeding pattern, and sex. However, serum total and direct bilirubin levels and ratio of direct to total bilirubin levels on admission and serum total bilirubin levels at the 24th hour of phototherapy were significantly higher in group II compared with group I (18.25 ± 2.94 vs 20.08 ± 2.99, P = .005; 0.54 ± 0.13 vs 0.69 ± 0.22, P = .001; 0.02992 ± 0.00702 vs 0.035188 ± 0.01581, P = .0024; and 8.83 ± 1.49 vs 10.08 ± 1.42, P = .0001, respectively) (Figure 1). Decrease in serum total bilirubin level at 24th hour calculated as percent was significantly higher in group I compared with group II (51.55 ± 4.01% vs 49.61 ± 3.43%, P = .022) (Table 3; Figure 2).

Table 3.

Comparison of demographic and laboratory characteristics of newborns with significant hyperbilirubinemia but without urinary tract infection (group I) and of newborns with both significant hyperbilirubinemia and urinary tract infection (group II).

| Parameter | Group I (n = 129) | Group II (n = 26) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age, wka | 37.87 ± 1.56 | 37.85 ± 1.19 | .946 |

| Maternal age, ya | 28.28 ± 5.0 | 29.92 ± 3.82 | .065 |

| Age on admission, ha | 128.48 ± 75.58 | 127.73 ± 66.63 | .963 |

| Birth weight, ga | 3131.47 ± 475.63 | 3336.15 ± 555.38 | .054 |

| Weight on admission, ga | 2987 ± 458.1 | 3175.38 ± 494.14 | .061 |

| Weight loss on admission as percent (if present)a | 5.08 ± 3.64 | 6.08 ± 5.26 | .242 |

| Serum total bilirubin, mg/dLa,b | 18.25 ± 2.94 | 20.08 ± 2.99 | .005 |

| Serum direct bilirubin, mg/dLa,b | 0.54 ± 0.13 | 0.69 ± 0.22 | .001 |

| Ratio of direct to total bilirubin levelsa | 0.02992 ± 0.00702 | 0.035188 ± 0.01581 | .0024 |

| Serum total bilirubin at the 24th hour of phototherapy, mg/dLa,b | 8.83 ± 1.49 | 10.08 ± 1.42 | .0001 |

| Decrease in serum total bilirubin at 24th hour as percent | 51.55 ± 4.01 | 49.61 ± 3.43 | .022 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dLa | 17.54 ± 2.17 | 17.3 ± 2.3 | .608 |

| Hematocrita | 50.8 ± 6.56 | 50.1 ± 6.67 | .594 |

| Free T4, ng/dLa | 1.8 ± 2.74 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | .479 |

| TSH, µIU/mLa | 3.75 ± 1.8 | 3.68 ± 2.12 | .868 |

| Presence of pyuria (present/absent) | 7/122 | 3/23 | .223 |

| Route of delivery (vaginal/cesarean) | 52/78 | 10/16 | .919 |

| Sex (female/male) | 69/60 | 3/23 | .000 |

| Enclosed hemorrhage (present/absent) | 5/124 | 2/24 | .33 |

| Abnormal weight loss (present/absent) | 7/122 | 2/24 | .647 |

| Feeding pattern | |||

| Breast milk (%) | 118 (91.47) | 22 (84.61) | |

| Formula milk (%) | 4 (3.1) | 1 (3.84) | .094 |

| Partially breast milk (%) | 7 (5.42) | 3 (11.53) | |

Values are given as mean ± SD.

1 mg/dL bilirubin = 17.1 µmol/L bilirubin.

Figure 1.

Comparison of serum total bilirubin levels in the study groups.

Figure 2.

Comparison of percentage decreases in serum total bilirubin levels at the 24th hour of phototherapy in the study groups.

Discussion

Although the pathophysiologic relationship between hyperbilirubinemia and UTI has not exactly been revealed, one of the suggested mechanisms is hemolysis caused by E coli and other gram-negative bacteria. Even little hemolysis in the newborn may cause significant hyperbilirubinemia due to immature conjugation mechanisms, and thus, serum bilirubin levels may increase as an alerting sign even in UTIs with mild clinical severity. Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia associated with UTI may be related to cholestasis. Although how UTI causes cholestasis is not well defined, microcirculatory problems in liver and direct bacterial and endotoxin-mediated products are the other suggested mechanisms.16 However, some authors claim that the relationship between UTI and neonatal jaundice is just a coincidence.17

In studies investigating the etiologic role of UTI in neonatal jaundice, the incidence of UTI has been reported between 5.8% and 21%.2,5,6,9 Ghaemi et al9 have reported a 5.8% incidence of UTI in 400 newborns in a prospective study. Garcia and Nager5 have reported a UTI incidence of 7.5% in 160 infants of less than 8 weeks old with no other complaints other than jaundice. Bilgen et al2 have reported a UTI incidence of 8% in 102 infants with jaundice. In their retrospective study, Omar et al6 have reported the highest (21%) incidence in 152 jaundiced infants. In our study, we detected the prevalence of UTI as 16.7% in 155 newborns with early jaundice in whom all other etiologic factors of significant neonatal hyperbilirubinemia were ruled out.

There are various ideas about the profile of microorganisms causing both jaundice and UTI. In a retrospective analysis of 120 asymptomatic jaundiced newborns, the most commonly detected (6 of 15) causative agent was Klebsiella pneumoniae.11 In another retrospective study, the most common (5 of 12) causative agent was E coli in 217 asymptomatic jaundiced infants.4 In our study, the most commonly isolated agent was Klebsiella spp. (8 of 26; 30.7%). However, geographical or environmental factors may contribute to bacteriologic and epidemiologic characteristics of UTI.

In infants with UTI, the prevalence of pyuria has reportedly been 58.3%, 52%, and 33% in 3 different studies, respectively.4,8,11 In our study, pyuria was present in 15.3% of 26 newborns with UTI.

Garcia and Nager5, in their study analyzing the association of neonatal jaundice and UTI, have reported that UTI was present in all the cases who had conjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Singh-Grewal et al18 have detected a stronger association with UTI due to E coli and conjugated hyperbilirubinemia compared with that of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. In our study, cases with both UTI and significant hyperbilirubinemia had significantly higher conjugated bilirubin levels and higher direct/total bilirubin ratio when compared with cases of group I who had significant hyperbilirubinemia without UTI.

In most of the studies investigating the relationship between UTI and neonatal jaundice, male sex was a significant risk factor compared with female sex in the neonatal period.8,9,19,20 In accordance with these studies reported, most of the cases (23 of 26) with both UTI and significant hyperbilirubinemia in our study were men. Ghaemi et al9 have reported that 60% of their male cases with UTI were not circumcised, and Singh-Grewal et al18 have reported that circumcision significantly reduces the risk of UTI. In another study, it has been reported that a high uropathogenic bacteria colonization is observed in uncircumcised newborns, and this increases UTI risk 10-fold.21 As all the newborns in our study were uncircumcised, we could not make a comparison regarding this. However, it has been well demonstrated that newborn circumcision results in a 9.1- to 9.9-fold decrease in incidence of UTI during the first year of life.22,23

Garcia and Nager5 have reported that infants whose jaundice presents after 8 days of life have UTI very likely. In our study, jaundice had occurred in 84.6% of cases in the first 7 days of life. Similarly, Bilgen et al2 have reported that most of their cases developed jaundice after the seventh day of life. This study differs from most of the other studies published as newborns with early-onset (≤7 days) jaundice were studied predominantly.

Ghaemi et al9 have reported that infants fed formula milk had a significantly higher risk of UTI compared with infants fed breast milk. Chen et al4 have also reported similar results. In this study, we did not detect a significant difference between the groups with and without UTI regarding feeding pattern.

In their study comparing jaundiced infants with and without UTI, Shahian et al11 have detected no significant differences regarding serum bilirubin levels. Some other studies have reported significantly lower serum bilirubin levels in newborns with prolonged jaundice and UTI compared with those without UTI.3,24 In our study, however, serum bilirubin levels both on admission and at the 24th hour of phototherapy were statistically significantly higher in newborns with UTI and jaundice compared with those with jaundice but without UTI.

In our study design, we tested the efficacy of phototherapy by measuring and comparing the serum bilirubin levels at 24th hour. We found that response to phototherapy in terms of serum bilirubin decrease was lower in newborns with both UTI and jaundice compared with those with jaundice but without UTI. Poor phototherapy response similar to that observed in hemolytic hyperbilirubinemias is interesting; this may have also resulted from statistically significantly increased serum direct bilirubin levels and direct to total bilirubin ratio, and thus, the possibility of UTI should be considered in jaundiced (especially conjugated) newborns who do not respond to phototherapy well or have a prolonged duration of phototherapy treatment.

As a conclusion, UTI should be routinely investigated in early (≤10 days) idiopathic neonatal jaundice in which all other etiologic factors of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia are ruled out, and the presence of UTI should be considered in case of a poor phototherapy response in cases receiving phototherapy.

Footnotes

Peer review:Four peer reviewers contributed to the peer review report. Reviewers’ reports totaled 1434 words, excluding any confidential comments to the academic editor.

Funding:The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: Concept: MO and SUS. Design: MO and SUS. Supervision: MAS and DS. Materials: YY and MA. Data collection and/or processing: DA and BO. Analysis and/or interpretation: SUS and MAS. Literature review: MO and SUS. Writing: MO and SUS.

References

- 1. Linder N, Yatsiv I, Tsur M, et al. Unexplained neonatal jaundice as an early diagnostic sign of septicemia in the newborn. J Perinatol. 1988;8:325–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bilgen H, Ozek E, Unver T, Biyikli N, Alpay H, Cebeci D. Urinary tract infection and hyperbilirubinemia. Turk J Pediatr. 2006;48:51–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nickavar A, Sotoudeh K. Treatment and prophylaxis in pediatric urinary tract infection. Int J Prev Med. 2011;2:4–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen HT, Jeng MJ, Soong WJ, et al. Hyperbilirubinemia with urinary tract infection in infants younger than eight weeks old. J Chin Med Assoc. 2011;74:159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Garcia FJ, Nager AL. Jaundice as an early diagnostic sign of urinary tract infection in infancy. Pediatrics. 2002;109:846–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Omar C, Hamza S, Bassem AM, Mariam R. Urinary tract infection and indirect hyperbilirubinemia in newborns. N Am J Med Sci. 2011;3:544–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pashapour N, Nikibahksh AA, Golmohammadlou S. Urinary tract infection in term neonates with prolonged jaundice. Urol J. 2007;4:91–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rashed YK, Khtaband AA, Alhalaby AM. Hyperbilirubinemia with urinary tract infection in infants younger than eight weeks old. J Pediatr Neonatal Care. 2014;1:00036. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ghaemi S, Fesharaki RJ, Kelishadi R. Late onset jaundice and urinary tract infection in neonates. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:139–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mutlu M, Çayır Y, Aslan Y. Urinary tract infections in neonates with jaundice in their first two weeks of life. World J Pediatr. 2014;10:164–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shahian M, Rashtian P, Kalani M. Unexplained neonatal jaundice as an early diagnostic sign of urinary tract infection. Int J Infect Dis. 2012;16:e487–e490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia. Management of hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant 35 or more weeks of gestation. Pediatrics. 2004;114:297–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maisels MJ, Bhutani VK, Bogen D, Newman TB, Stark AR, Watchko JF. Hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant ≥35 weeks’ gestation: an update with clarifications. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1193–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wong RJ, Bhutani VK. Pathogenesis and etiology of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn. In: Abrams SA, Rand EB. eds. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2015. www.uptodate.com/contents/pathogenesis-and-etiology-of-unconjugated-hyperbilirubinemia-in-the-newborn. Accessed August 17, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stein R, Dogan HS, Hoebeke P, et al. ; European Association of Urology; European Society for Pediatric Urology. Urinary tract infections in children: EAU/ESPU guidelines. Eur Urol. 2015;67:546–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kasap B, Soylu A, Kavukçu S. Relation between hyperbilirubinemia and urinary tract infections in the neonatal period. J Nephrol Therapeutic. 2014;S11:009. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sarici SÜ, Kul M, Alpay F. Neonatal jaundice coinciding with or resulting from urinary tract infections? Pediatrics. 2003;112:1212–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Singh-Grewal D, Macdessi J, Craig J. Circumcision for the prevention of urinary tract infection in boys: a systematic review of randomised trials and observational studies. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:853–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee HC, Fang SB, Yeung CY, Tsai JD. Urinary tract infections in infants: comparison between those with conjugated vs unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2005;25:277–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chang SL, Shortliffe LD. Pediatric urinary tract infections. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53:379–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zorc JJ, Levine DA, Platt SL, et al. Clinical and demographic factors associated with urinary tract infection in young febrile infants. Pediatrics. 2005;116:644–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schoen EJ, Colby CJ, Ray GT. Newborn circumcision decreases incidence and costs of urinary tract infections during the first year of life. Pediatrics. 2000;105:789–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morris BJ, Wiswell TE. Circumcision and lifetime risk of urinary tract infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol. 2013;148:2118–2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abourazzak S, Bouharrou A, Hida M. [Jaundice and urinary tract infection in neonates: simple coincidence or real consequence?]. Arch Pediatr. 2013;20:974–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]