Abstract

Objective

This study tested mediating processes hypothesized to explain the therapeutic benefit of an efficacious motivational interview (MI). The constructs of interest were motivation to change, cognitive dissonance about current drinking, self-efficacy for change, perceived young adult drinking norms, future drinking intentions, and the use of protective behavioral strategies.

Method

A randomized controlled trial compared the efficacy of a brief MI to a time- and attention-matched control of meditation and relaxation training for alcohol use. Participants were underage, past-month heavy drinkers recruited from community (i.e., non four-year college or university) settings (N=167; ages 17–20; 58% female; 61% White). Statistical analyses assessed mechanisms of MI effects on follow up (6-week; 3-month) percent heavy drinking days (HDD) and alcohol consequences (AC) with a series of temporally-lagged mediation models.

Results

MI efficacy for reducing 6-week HDD was mediated by baseline to post-session changes in the following three processes: increasing motivation and self-efficacy, and decreasing the amount these young adults intended to drink in the future. For 6-week AC, MI efficacy was mediated through one process: decreased perceived drinking norms. At 3-month follow up, increased cognitive dissonance mediated HDD, but not AC. Further, increased use of certain protective behavioral strategies (i.e., avoidance of and seeking alternatives to drinking contexts) from baseline to 6-weeks mediated both 3-month HDD and AC.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that within-session cognitive changes are key mechanisms of MI’s effect on short-term alcohol outcomes among community young adults while protective behaviors may be more operative at subsequent follow up.

Keywords: Alcohol use and consequences, Mechanism of behavior change, Mediation analyses, Motivational Interviewing, Non-college young adults

Introduction

Compared to all other age groups, young adults (18–25) have the highest prevalence of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorder (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2011). The past 20 years have produced important gains in campus-based intervention options for college student alcohol users, including a substantial growth in the use of brief interventions based on the principles of Motivational Interviewing (MI; Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & Demartini, 2007; Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Elliot, Garey, & Carey, 2012; Larimer at al., 2007). Community young adults (i.e., young adults not enrolled in a traditional, four-year college or university) have rarely been a focus of this research. This is despite the fact these individuals comprise the majority of the young adult population and are at higher risk for lifetime alcohol dependence than four-year college students (White, Labouvie, & Papadaratsakis, 2005). In one of the few randomized clinical trials conducted to date, MI efficacy for reducing heavy alcohol use and related negative consequences was demonstrated (Colby et al., under review), supporting MI’s viability as a brief alcohol treatment for non-traditional, young adult vocational and educational settings (e.g., employee assistance programs, GED training programs, technical schools, and community colleges). The findings also present an opportunity to test the specific MI ingredients and mechanisms hypothesized to account for intervention efficacy. Identifying treatment effect mediators would provide empirically-derived information to optimize intervention delivery with this population. Even within the campus-based, four-year college literature, studies on key components of brief alcohol treatment effects are only emerging (Ray et al., 2014) and a convergence of the evidence on a core set of processes involved in behavior change is still limited (Reid & Carey, 2015).

Studying Ingredients of Treatments and Mechanisms of Change

Unless randomized clinical trials show 100% participant improvement (i.e., 100% of outcome variance explained by the experimental condition), we cannot test treatment efficacy without also testing treatment theory. Without tests of the explanatory model of the treatment, we cannot identify which ingredients and/or mechanisms were responsible for observed changes relative to control (Longabaugh, 2007). These kind of analyses typically occur via tests of statistical mediation with observationally rated (e.g., Motivational Interviewing Skill Code; Houck, Moyers, Miller, Glynn, & Hallgren, 2010) or participant self-reported indicators. In the prevention literature, the treatment to mediator path (a path) is conceptualized as a test of implementation success or failure (i.e., did the intervention produce the expected changes in hypothesized intermediate process variables?), while the mediator to outcome path (b path) is a test of theory success or failure (i.e., were these theorized processes actually important to participant improvement?) (MacKinnon, 2008).

In the present work, we distinguish ingredients of treatments from mechanisms of change in the interest of furthering a common conceptual frame for examination. Specifically, treatment ingredients include any therapeutic skill, process, or component with a relationship to outcome or to a subsequent mediator of outcome (Longabaugh, Magill, Morgenstern, & Huebner, 2013). The distinction between being an active versus hypothesized ingredient is demonstrated predictive validity. Active ingredients may be common across therapies (e.g., therapeutic alliance), distinctive to only a few (e.g., coping skills training), or established as unique to a single modality (e.g., contingent reinforcement in contingency management; Longabaugh & Magill, 2011; Longabaugh et al., 2013). In contrast, a mechanism of behavior change is a process occurring within the individual or a behavior enacted by the individual that is associated with a subsequent change in the targeted outcome of interest (Kazdin & Nock, 2003; Nock, 2007). In the clinical trial context, mechanisms are often examined through self-reported changes in specified cognitions or behaviors that are thought to produce changes in the targeted outcome of interest.

The MI Approach to Changing Young Adult Drinking Behavior

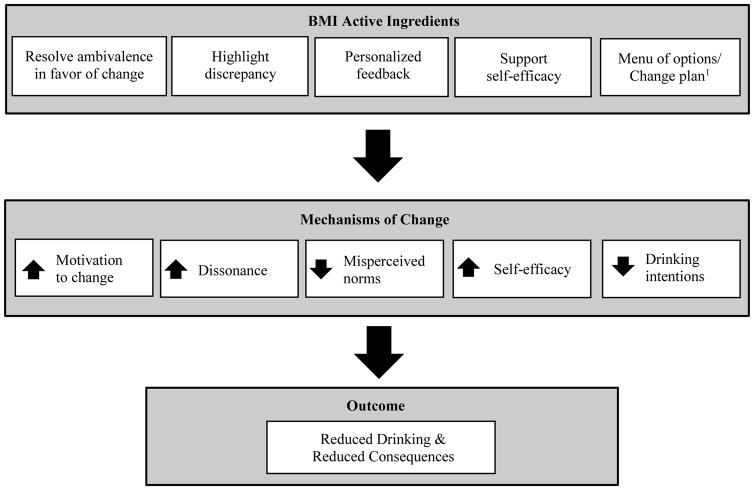

The efficacy of MI for reducing heavy drinking and negative consequences in young adult college students has been demonstrated (Carey et al., 2012; Tanner-Smith, Steinka, Hennessy, Lipsey, & Winters, 2015). The MI approach explores ambivalence about behavior change, and encourages individuals to explore the discrepancy between current drinking behavior and personal values and goals (Miller & Rollnick, 2002; 2013; Figure 1). The MI therapist attempts to facilitate behavior change decision-making by affirming self-efficacy, providing personalized feedback on patterns and risks, and offering a menu of behavior change options (Monti, Colby, & O’Leary, 2001; Figure 1). Currently, it is unknown whether processes, proposed and tested in the largely campus-based, four-year college literature, are similarly operative when brief MI is delivered to young adults outside of this environment. There may be differences in contextual influences on drinking and on behavior change such as workplace influences, peer and family factors, and variable access to resources. Such differences may change the content and nature of discussion within a motivational interview. For example, the impact of changing normative beliefs about peer drinking levels may be greater in the campus context given homogeneity of the cultural environment. Young adults not involved in this enviroment might have more variability in their peer groups and role models, including variation by age, life roles, and patterns of drinking. Moreover, discrepancy (i.e., cognitive dissonance) around alcohol use and how it may facilitate or hinder role functioning may be greater for community-based young adults, who often have more adult responsibilities than their campus-based peers.

Figure 1.

Proposed Model of Ingredients and Mechanisms of Developmentally-tailored MI

Notes. 1. Menu of change options included strategies to avoid drinking situations or to seek alternatives to drinking. Also discussed were ways to control rate of consumption and other harm reduction techniques.

Although MI process has not been examined specifically with community young adults, the college student literature has tested a number of ingredients and mechanisms of MI’s effect on alcohol use and associated harms. We draw from this work as a starting point for the present study. For example, a recent systematic review examined support for behavior change mechanisms in college alcohol interventions, and included 22 putative cognitive (e.g., motivation, self-efficacy) or behavioral (e.g., use of protective behavioral strategies) process variables (Reid & Carey, 2015). Among cognitive change processes, only changing descriptive norms received compelling support as a mechanism of MI with college student drinkers. Behavioral measures had mixed, but promising support. The breadth of mediation research in the college intervention literature is wide, yet there is no established causal process model to date. In this study, we focus on a set of within-session cognitive mediators targeted in a manualized brief MI and highlighted in reviews of MI mechanisms of change (Reid & Carey, 2015). Behavioral strategies, described in the intervention menu of change options (see Figure 1), are also tested. The MI intervention was based on existing, college-based MI methods, but was developmentally- and contextually-tailored during an early developmental phase of the project (manual available upon request).

The Current Study

This study tested mediating processes hypothesized to explain the therapeutic benefit of an efficacious motivational interview. A key question was whether the MI mechanisms commonly tested in the college literature are operative when MI is delivered to underage, young adult drinkers who are not enrolled, nor planning to enroll, in traditional four-year college. We first examined pre- to post-session changes in cognitive mediators hypothesized to affect short-term reductions in heavy alcohol use and related negative consequences (i.e., 6-week and 3-month follow up). Short-term changes were of primary interest, given that analyses focused on intervention mechanisms of action. In such analyses, proximal indicators may offer a more sensitive assessment of treatment-related processes of change than analyses conducted at later follow ups (Morgenstern & McKay, 2007; Nock, 2007). Next, we examined changes in the use of specific protective behavioral strategies from baseline to 6-weeks in relation to 3-month heavy drinking and consequences. Study hypotheses related to cognitive mediators were that: increases in motivation to change, increases in actual-ideal drinking discrepancy, increases in self-efficacy for change, decreases in perceived young adult drinking norms, and decreases in intentions related to future drinking would mediate the relationship between receipt of MI and heavy drinking and consequence outcomes at 6-week and 3-month follow ups. Hypotheses related to behavioral mediators were that use of protective behavioral strategies at 6-week follow up would mediate MI’s effects on heavy drinking and consequences at 3-months. Individual mediation models first identified significant mediators, which were then analyzed simultaneously in multiple mediation models to explore relative mediator effects.

Method

Parent Study

In the parent randomized controlled trial, a brief MI was contrasted with a time- and attention-matched control of meditation and relaxation training (REL) for reducing heavy alcohol consumption and related negative consequences in a community-based, young adult sample. The MI condition was tailored to incorporate the developmental transition out of high school for young adults not immediately bound for a traditional four-year college. Participants were not seeking treatment for alcohol problems, and the study was not presented as a treatment study. Rather, the project was described as “a research study focusing on young people’s transitions to adulthood and reducing the risks of alcohol during this period.” Inclusion criteria were: 1) underage current drinkers between the ages of 17 and 20, 2) one or more occasions of past-month heavy drinking (≥ 4 drinks for females; ≥ 5 or more drinks for males), 3) not currently enrolled nor intending to enroll in a four-year college or university. Motivation to reduce alcohol use or associated harm was not a requirement for participation.

Participants and procedure

Participants were recruited from a range of community settings, including high schools, social service agencies, GED classes, vocational and technical training programs, and community colleges. Participants recruited from high school settings had to be seniors within three months of graduation, and not intending to matriculate to a traditional four-year college/university within the next year. There were 167 individuals enrolled in the study, and 100% of these individuals completed an in-person baseline assessment and then were randomly assigned to an intervention. The interventions took place immediately following baseline assessment and post-treatment assessments were completed at the end of the session. Follow up interviews were conducted in person, and study retention rates were high (>95%). The average age of participants was 18.2 (SD = 0.98; range = 17 to 20) and the sample was 62% female. Participant self-identified race and ethnicity were as follows: 59% non-Hispanic White, 10% non-Hispanic Black/African American, 11% Hispanic, and 14% identified as more than one race. The sample was heterogeneous in terms of school status, with 17% having left high school without graduating, 26% high school seniors, 26% recent high school graduates not enrolled in an academic program, and 31% were enrolled in community college or technical/vocational training program or school. All procedures were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board and participants gave written informed consent.

Interventions

Interventions were approximately 60 minutes in length and were provided by the same therapists across study conditions.

MI Condition

The MI session followed a typical, manualized format, with some component discussions incorporating topics related to young adult transitions (e.g., work, family). The session began with rapport building and exploration, eliciting information about the developmental context of drinking behavior as well as personal values and goals. The therapist explored the positive and negative aspects of drinking, and provided information on descriptive norms and personalized feedback. Here, the computer-generated feedback report summarized: 1) past-month frequency and quantity of heavy drinking with normative comparisons; 2) past-month typical and peak BAC; 3) alcohol-related consequences and risk factors; and 4) discretionary income and time allocated to alcohol consumption versus non-alcohol related activities. The therapist presented each topic of the report and invited discussion. Participants were asked to envision themselves in the future, regardless of whether they decided to make a change in their drinking. Finally, participants interested in making changes to their alcohol use were given opportunity to collaboratively establish goals and to discuss behavior change strategies. Throughout the session, the therapist utilized MI principles and techniques, including respecting autonomy, using open-ended questions and reflective listening, eliciting change talk, and supporting self-efficacy (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). See Figure 1 for a pictorial display of the conceptual model (i.e., intervention ingredients and mechanisms) for process analysis of the MI condition.

REL Condition

The REL condition was designed to control for nonspecific factors by providing equivalent levels of contact time and attention. REL similarly began with an introduction and general rapport building. The therapist reviewed the rationale for the treatment, stating that life transitions during young adulthood may be stressful. To address possible self-report bias specific to drinking outcomes, the treatment rationale stated that learning effective ways to cope with stress might reduce the likelihood of problematic alcohol use in response to stress. The exploration phase addressed the participant’s typical level of daily stress and reviewed current participant-employed coping behaviors. To promote treatment expectancies, a rationale and instructional exercise was provided. Specifically, mindfulness meditation and progressive muscle relaxation were introduced and practiced. The session concluded with a recommendation that the participant practice these techniques regularly.

Therapist training and fidelity

Study therapists included two PhD-level clinical psychologists and a BA-level counselor with several years’ counseling experience and coursework completed toward an MSW degree. Training procedures included didactic instruction and role-playing techniques. In both manualized conditions, prescribed and proscribed behaviors were enumerated. Fidelity to each intervention was monitored weekly and a subset of MI sessions were coded using the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity scale (MITI; Moyers, Martin, Manuel, Miller & Ernst, 2007).

Measures

Cognitive Mediator Measures

The specific constructs of interest to the current study were motivation to change, cognitive dissonance, self-efficacy for change, perceived drinking norms, and drinking intentions, all measured as baseline adjusted, post-session outcomes. The Contemplation Ladder (Biener & Abrams, 1991) was designed to assess motivation to change among nicotine users, but has been modified and validated to assess motivation to change alcohol use (Becker & Littleton, 1996). Response options range from 0–10 where 0 = “no thought of drinking less” and 10 = “taking action to drink less.” Dissonance was measured using Actual-Ideal Drinking Discrepancy, an indicator designed to gauge the disparity between actual and ideal drinking behaviors (adapted from McNally et al., 2005). Participants were instructed to circle a number on a horizontal scale that indicated how close or far their current drinking patterns were from their personal ideal (−5 = “I am drinking FAR LESS than my ideal”, 0 = “I am now at my ideal”, 5 = “I am drinking FAR MORE than my ideal”). Self-efficacy was measured using the Brief Situational Confidence Questionnaire (BSCQ; Breslin, Sobell, Sobell, & Agrawal, 2000) where respondents rated how confident they were that they would be able to resist drinking heavily in the coming year (0% = “not at all confident”, 100% = “completely confident”). To assess perceived drinking norms, we adapted the Drinking Norms Rating Form (DNRF; Borsari & Carey, 2000). Here, participants estimated the weekly alcohol consumption of their age- and gender-matched peers (e.g., an 18-year old male participant would be asked “How many drinks does a TYPICAL 18-year old male have?” on each day of the week, from Monday through Sunday). Total estimated drinks per week were summed to reflect perceived norms in terms of total drinks consumed. Future Drinking Intentions (LaBrie, Pederson, Earleywine, & Olsen, 2006) were assessed using the same Monday through Sunday calendar format. Participants were instructed to think about what their drinking pattern would be like over the next 6 weeks, and then were asked to enter the average number of drinks they planned to consume on each day of the week. Total drinks per week were summed to represent future drinking intentions.

Behavioral Mediator Measure

At 6-week follow up, the Strategies to Limit Drinking Scale (Werch & Gorman, 1986) was used. This 37-item measure assesses participant use of seven types of behavioral strategies: Rate Control (α = .87; e.g., took small sips), Self-reinforcement and Punishment (α = .71; e.g., rewarded self for limiting drinking), Alternatives to Drinking (α = .78; e.g., engage in alternative activities to drinking), Avoidance of Drinking Situations (α = .87; e.g., avoid drinking with a heavy drinker), Limiting Driving and Cash (α = .61; e.g., made plans not to drink and drive), Controlling Time and Food (α = .64; e.g., eat before I drink), and Awareness of Consequences (α = .68; e.g., thought about consequences of drinking). These subscale indicators were examined as potential mediators of outcomes at later (3-month) follow-up.

Outcome Measures

To assess heavy drinking, a 6-week Timeline Follow Back (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1992; 1995) was used. This calendar-assisted interview yielded estimates in terms of the number of standard drinks consumed daily in the prior 6 weeks at baseline, 6-week follow up, and 3-month follow up. From the TLFB, the percentage of heavy drinking days was calculated (defined as the percentage of days on which 4 or more drinks were consumed (for women) or 5 or more drinks (for men)). The Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (BYAACQ; Kahler, Strong, & Read, 2005) was used to assess alcohol consequences at baseline, and at 6-week and 3-month follow ups. The measure includes 24 possible alcohol-related negative consequences, and the total score reflects the number of alcohol-related consequences experienced in the past 6 weeks (α = .81).

Data Analysis

Preliminary Analyses

Outcome variables were checked for distributional assumptions. Percent heavy drinking days was positively skewed and log-transformed for analyses (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2006). Study attrition for follow-up assessments was approximately 3%, and missing data were handled via pairwise deletion in analyses. No statistically significant differences on key demographic or alcohol use characteristics were found between study conditions at baseline (Colby et al., under review). As a potential data reduction strategy, Pearson bivariate correlations and analyses of internal consistency reliability were used to assess whether the five cognitive mediators were best examined as a set of unique mechanisms or as a single latent construct of MI change process. Similarly, behavioral strategies as seven subs-scales or as a total score were tested in mediation analyses. Finally, descriptive data, and by condition significance tests (i.e., two-way analysis of variance, independent samples t test), for all study variables are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Data on Study Variables of Interest

| REL (n=84) | MI (n=83) | (p) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M/SD | min/max | M/SD | min/max | ||

| Cognitive Mediators | |||||

| BL Motivation | 3.9(3.2) | 0–10 | 4.6(3.2) | 0–10 | |

| PT Motivation | 4.8(3.4) | 0–10 | 7.0(3.1) | 0–10 | .000 |

| BL Dissonance | 1.0(2.1) | -5-5 | 1.1(2.2) | -5-5 | |

| PT Dissonance | 0.5(2.1) | -5-5 | 1.9(2.5) | -5-5 | .000 |

| BL Self-Efficacy | 66.5(29.1) | 0–100 | 63.9(28.2) | 0–100 | |

| PT Self-Efficacy | 73.1(26.9) | 0–100 | 76.9(23.8) | 9–100 | .036 |

| BL Drinking Norms | 18.9(15.7) | 3–120 | 19.6(21.2) | 0–130 | |

| PT Drinking Norms | 17.0(10.9) | 0–59 | 13.2(19.7) | 0–117 | .000 |

| BL Drinking Intentions | 17.9(14.9) | 0–91 | 20.4(21.3) | 0–117 | |

| PT Drinking Intentions | 14.9(14.9) | 0–103 | 9.7(9.6) | 0–56 | .001 |

| Behavioral Mediators | |||||

| 6 wk Rate Control | 22.6(9.4) | 10–50 | 23.6(8.3) | 10–43 | .466 |

| 6 wk Self-Reinforce/Punish | 14.9(5.9) | 7–30 | 15.5(5.6) | 7–30 | .498 |

| 6 wk Alternatives | 10.2(4.4) | 4–20 | 11.9(5.1) | 4–20 | .024 |

| 6 wk Avoidance | 17.2(7.4) | 7–35 | 19.4(7.8) | 7–35 | .068 |

| 6 wk Limit Drive/Cash | 10.8(3.3) | 3–15 | 10.3(3.5) | 3–15 | .322 |

| 6 wk Time/Food Control | 9.9(3.2) | 3–15 | 9.5(3.3) | 3–15 | .380 |

| 6 wk Awareness | 8.8(2.9) | 3–15 | 9.4(3.0) | 3–15 | .298 |

| Total Score Outcome Variables | |||||

| BL % Heavy Drinking Days | 17.3(13.9) | 0–57.1 | 18.8(14.6) | 0–82.1 | |

| 6 wk % Heavy Drinking Days | 16.1(15.8) | 0–80.9 | 10.0(13.3) | 0–97.6 | .000 |

| 3 mo % Heavy Drinking Days | 13.3(12.4) | 0–76.2 | 8.0(9.9) | 0–54.8 | .003 |

| BL # Negative Consequences | 6.9(4.5) | 0–21 | 8.4(4.5) | 1–24 | |

| 6 wk # Negative Consequences | 6.1(4.1) | 0–17 | 5.8(5.1) | 0–24 | .011 |

| 3 mo # Negative Consequences | 5.9(4.1) | 0–17 | 4.8(4.5) | 0–18 | .000 |

| BL # Drinks per Drinking Daya | 6.6(3.3) | 1–18 | 6.9(4.8) | 1.8–27.7 | |

| 6 wk # Drinks per Drinking Daya | 6.5(3.5) | 1.5–24 | 5.2(2.9) | 1.3–20 | .008 |

| 3 mo Drinks per Drinking Daya | 6.3(3.1) | 1–19.5 | 5.5(3.7) | 1–22.3 | .167 |

Notes. BL = Baseline; PT = Post-treatment; wk = week; mo = month; at 6 weeks, 11.7% of participants had zero heavy drinking days; at 3 months, 19.9% of participants had zero heavy drinking days.

Data provided for sample description only.

Mediation Analyses

The overarching model of MI efficacy on reduced heavy drinking and negative consequences was tested in single, followed by multiple, mediation models. A series of single mediator models first tested whether each of the proposed variables showed significant indirect effects on study outcomes at 6-week and/or 3-month follow ups. Significant mediators were then entered into multiple mediator models to examine relative mediator effects. Mediation was tested in Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression path models, followed by distribution free bootstrap hypothesis tests of indirect effects (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007). Specifically, the product of a and b path regression coefficients, with 95% bias corrected bootstrap confidence intervals (CI; Efron, 1987), tested whether specific and total (a1b1 + a2b2 …aibi) indirect effects were significantly different from zero (Hayes, 2013). Bias corrected bootstrap CI have demonstrated good balance between Type I and II error rates (Briggs, 2006), and are thus the reported significance test of indirect effects.

Results

Preliminary Results One: MI Implementation Success or Failure?

Descriptive analyses, and by-condition significance tests, for all study variables are shown in Table 1. These results not only show MI efficacy over REL for reduced heavy drinking and consequences at both follow ups, but also a path implementation success for all purported cognitive mechanisms, and two behavioral mechanisms (i.e., seeking alternatives to drinking and avoiding drinking situations).

Preliminary Results Two: Single versus Multiple Cognitive Processes of Change?

Analyses of bivariate relationships among post-session mediators as well as analysis of internal consistency suggest the five variables did not reflect a single underlying latent construct of MI cognitive change (see Table 2). In correlation analyses, some, but not all, indicators showed associations that were small to moderate and statistically significant. Motivation to change was positively related to cognitive dissonance (p < .001) and negatively related to intentions for future drinking (p = .001). Self-efficacy to change heavy drinking was negatively associated with perceived norms for a typical young adult (p = .033) and intentions for future drinking (p = .003). Finally, perceived drinking norms and participant drinking intentions were positively related (p < .001). This latter association was the strongest among those examined, but was only in the small to moderate range. When all five cognitive mediators were assessed as a single construct, the internal consistency coefficient alpha was .44, indicating conceptual heterogeneity (Nunnally, 1978).

Table 2.

Bivariate Relationships among Post-Session Mediators

| Motivation | Dissonance | Self-efficacy | Norms | Intentions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation | 1 | ||||

| Dissonance | .27*** | 1 | |||

| Self-efficacy | .11 | .04 | 1 | ||

| Norms | .01 | .03 | − .14* | 1 | |

| Intentions | −.24** | .00 | −.21** | .35*** | 1 |

Notes. N = 167;

p < .001;

p < .01;

p < .05

Single Mediation Models: Testing the Significance of Each Indirect Effect on 6-Week Heavy Drinking and Consequences

Table 3 shows the results from the individual OLS regression path models, and bootstrap tests for indirect effects are reported here. In OLS path analysis and consistent with the pattern of results reported in Table 1, MI significantly affected all five hypothesized cognitive mediators (a paths, including: increased motivation for change (p < .001), dissonance (p < .001), and self-efficacy for change (p = .025), and decreased perceived drinking norms (p = .039) and future drinking intentions (p < .001)). For mediator to outcome (b) OLS path effects, three of five hypothesized mediators showed significant relationships. Specifically, increased motivation for change (p = .009) and self-efficacy (p < .001), and reduced drinking intentions (p = .002) were associated with reduced heavy drinking days. For bootstrap results on the product of ab path coefficients, indirect effects for motivation (−.14; 95%CI: −.31 to −.04), self-efficacy (−.08; 95%CI: −.22 to −.02), and future drinking intentions (−.12; 95%CI: −.29 to −.03) were significantly different from zero.

Table 3.

OLS Path Estimates for Cognitive Mediators of 6-Week Heavy Drinking and Negative Consequences

| a Path of BMI to Mediator | b path of Mediator to Outcome

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Heavy Drinking Days | Negative Consequences | |||||

|

| ||||||

| β(se)~ | p~ | β(se) | p | β(se) | p | |

| Single Mediators | ||||||

| Motivation | 0.544 (.11) | <0.001 | −0.255 (.10) | 0.009 | −0.058 (.11) | 0.588 |

| Dissonance | 0.609 (.13) | <0.001 | −0.141 (.08) | 0.086 | −0.235 (.09) | 0.007 |

| Self-Efficacy | 0.236 (.10) | 0.025 | −0.359 (.10) | 0.003 | −0.066 (.11) | 0.531 |

| Norms | −0.262 (.13) | 0.039 | 0.153 (.08) | 0.069 | 0.266 (.08) | 0.002 |

| Intentions | −0.489 (.13) | <0.001 | 0.256 (.08) | 0.002 | 0.193 (.08) | 0.019 |

| Multiple Mediators* | ||||||

| Motivation | 0.535 (.11) | <0.001 | −0.131 (.10) | 0.190 | ||

| Self-Efficacy | 0.218 (.11) | 0.040 | −0.281 (.10) | 0.006 | ||

| Intentions | −0.450 (.13) | <0.001 | 0.172 (.08) | 0.039 | ||

Notes. Regression coefficient estimates significant at the .05 level in bold.

a path data shown for heavy drinking days; negative consequence a path estimates are substantively the same though vary slightly due to a different baseline covariate for the outcome variable (i.e., baseline negative consequences).

Total indirect effect significant for bias corrected and percentile bootstrap confidence intervals (−.21; 95% CI: −.44 to −.08).

For number of alcohol consequences, individual mediator models showed that one of the five cognitive variables examined was a significant mediator of MI efficacy, in contrast to REL, at 6-week follow up. A path OLS models showed results consistent with that reported for heavy drinking days (i.e., MI significantly impacted all five mediators as hypothesized), but with slight variation in coefficient estimates due to a different baseline covariate for the outcome variable (i.e., alcohol consequences; not shown in Table 3). For the b path OLS models, greater dissonance (p = .007), and lower perceived drinking norms (p = .002) and future drinking intentions (p = .020) were associated with reduced alcohol consequences. However, only the bootstrap CI for the ab path product of perceived drinking norms did not contain zero (−.08; 95%CI: −.23 to −.01). Because only one indirect effect was significant, multiple mediator analysis was not conducted for alcohol consequence outcomes at 6-week follow up (see Table 3; 33% outcome variance explained in the final, single mediator model).

Multiple Mediation Models: Testing Relative Indirect Effects on 6-week Heavy Drinking Outcome

For multiple mediation analyses in relation to 6-week percent heavy drinking days, motivation to change, self-efficacy for change, and drinking intentions were entered into the model, covarying baseline values of each mediator and the outcome variable. The total indirect effect was statistically significant (−.21; 95% CI: −.44 to −.08), and together, these cognitive processes accounted for 38% of the outcome variance in MI’s effect on reduced heavy drinking at early follow up. Relative indirect effects within the multiple mediator model were non-significant, suggesting that when examined simultaneously, no single cognitive process was uniquely beneficial in producing short-term behavior change (see Table 3).

Single Mediation Models: Testing the Significance of Each Indirect Effect on 3-Month Heavy Drinking and Consequences

Table 4 shows the results from the individual OLS regression path models. For percent heavy drinking days (log transformed), individual mediator models showed one cognitive mediator of MI efficacy, in contrast to REL, at 3-month follow up. Here, the pattern of a path OLS estimates and significance tests was consistent with those previously reported (Table 3). Table 4 also shows that among these processes impacted by MI, increased cognitive dissonance (p < .001) and self-efficacy (p =.047) were associated with reduced percent heavy drinking days in OLS regression path models. Finally, bias-corrected bootstrap results showed only increased dissonance from pre-to-post session had a significant indirect effect on 3-month alcohol outcomes (−.17; 95%CI: −.42 to −.04). A multiple mediator model for heavy drinking at later follow up was therefore not performed (30% outcome variance explained in final, single mediator model). Further, for number of negative alcohol consequences at 3-month follow up, no post-session cognitive mediator predicted outcome (see Table 4).

Table 4.

OLS Regression Path Estimates for Cognitive Mediators of 3-Month Heavy Drinking and Negative Consequences

| a Path of BMI to Mediator | b path of Mediator to Outcome

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Heavy Drinking Days | Negative Consequences | |||||

|

| ||||||

| β(se)~ | p~ | β(se) | p | β(se) | p | |

| Single Mediators | ||||||

| Motivation | 0.524 (.11) | <0.001 | −0.120 (.10) | 0.213 | 0.097 (.11) | 0.386 |

| Dissonance | 0.628 (.12) | <0.001 | −0.278 (.08) | <0.001 | −0.137 (.09) | 0.138 |

| Self-Efficacy | 0.247 (.10) | 0.019 | −0.199 (.10) | 0.047 | 0.020 (.11) | 0.859 |

| Norms | −0.327 (.12) | 0.008 | −0.065 (.09) | 0.449 | 0.050 (.10) | 0.622 |

| Intentions | −0.547 (.13) | <0.001 | 0.092 (.08) | 0.259 | 0.049 (.09) | 0.596 |

Notes. Regression coefficient estimates significant at the .05 level in bold.

a path data shown for heavy drinking days; negative consequence a path estimates are substantively the same though vary slightly due to a different baseline covariate for the outcome variable (i.e., baseline negative consequences).

Behavioral Mediation Analyses: Are Behavioral rather than Cognitive Processes Operative at Later Follow up?

Strategies to Limit Drinking were evaluated as potential mediators of 3-month follow up outcomes. These results are shown in Table 5. In OLS models, MI predicted significantly more use of two of the seven subscales at 6 weeks: seeking alternatives to drinking (p = .036) and avoidance of drinking contexts (p = .017). In relation to outcome, b path OLS models showed rate control (p = .045), self-reward or punishment (p = .001), seeking alternatives (p = .012), and avoidance of drinking contexts (p = .008) were all associated with reduced heavy drinking at 3-month follow up. For bootstrap results, indirect effects for seeking alternatives (−.06; 95%CI: −.17 to −.01) and avoidance of drinking contexts (−.06; 95%CI: −.15 to −.01) were significantly different from zero. In the subsequent multiple mediator model, a similar pattern to that for heavy drinking at 6-week follow ups was observed where only the total indirect effect was significant (−.09; 95%CI: −.19 to −.02) and this final model explained 37% of the outcome variance in 3-month heavy drinking.

Table 5.

OLS Regression Path Estimates for Behavioral Mediators of 3-Month Heavy Drinking and Negative Consequences

| a Path of BMI to Mediator | b path of Mediator to Outcome

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Heavy Drinking Days | Negative Consequences | |||||

|

| ||||||

| β(se)~ | p~ | β(se) | p | β(se) | p | |

| Single Mediators | ||||||

| Rate Control | 0.133 (.16) | 0.404 | −0.135 (.07) | 0.045 | −0.059 (.07) | 0.436 |

| Self-Reinforce/Punishment | 0.141 (.16) | 0.376 | −0.234 (.07) | <0.001 | −0.122 (.08) | 0.126 |

| Alternatives | 0.386 (.16) | 0.017 | −0.169 (.07) | 0.012 | −0.042 (.08) | 0.588 |

| Avoidance | 0.331 (.16) | 0.036 | −0.180 (.07) | 0.008 | −0.190 (.08) | 0.014 |

| Limit Drive/Cash | −0.151 (.16) | 0.350 | −0.043 (.07) | 0.519 | −0.085 (.08) | 0.265 |

| Time/Food Control | −0.107 (.16) | 0.512 | 0.001 (.07) | 0.983 | 0.027 (.07) | 0.719 |

| Awareness | 0.174 (.16) | 0.276 | −0.049 (.07) | 0.467 | −0.111 (.07) | 0.132 |

| Multiple Mediators* | ||||||

| Alternatives | 0.386 (.16) | 0.017 | −0.117 (.07) | 0.104 | ||

| Avoidance | 0.338 (.16) | 0.034 | −0.129 (.07) | 0.077 | ||

Notes. Regression coefficient estimates significant at the .05 level in bold.

a path data shown for heavy drinking days; negative consequence a path estimates are substantively the same though vary slightly due to a different baseline covariate for the outcome variable (i.e., baseline negative consequences). Single mediator effect for the total scale score was non-significant.

Total indirect effect significant for bias corrected and percentile bootstrap confidence intervals (−.09; 95%CI: −.19 to −.02).

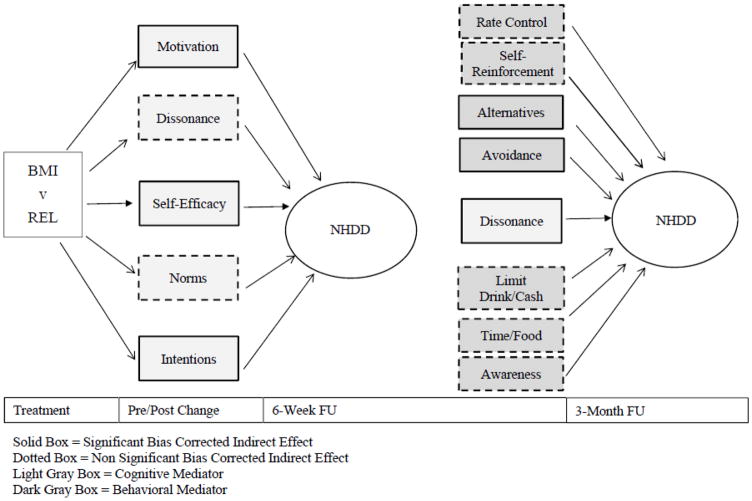

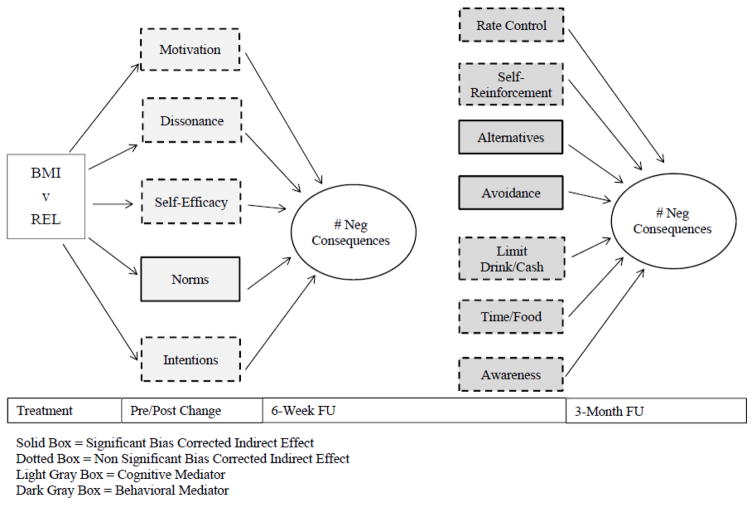

Table 5 also shows the findings for analyses of 6-week behavioral strategies in relation to MI efficacy on 3-month negative consequences. While a path models were consistent with those reported above, the b path models showed only avoidance of drinking contexts (p = .014) was significantly associated with reduced alcohol consequences at 3 months (−.07; 95%CI: −.13 to −.01; 26% outcome variance explained). A subsequent multiple mediator model was not undertaken. See Figures 2 and 3 for a pictorial summary of all findings by outcome and over time.

Figure 2.

Overall Process Model of BMI Efficacy through Cognitive and Behavioral Mediators – Heavy Drinking

Figure 3.

Overall Process Model of BMI Efficacy through Cognitive and Behavioral Mediators – Negative Consequences

Discussion

In this study, we tested a causal process model of MI efficacy when delivered to underage young adult heavy drinkers who were not traditional four-year college students. Both study conditions were tailored to incorporate content related to young adult life transitions, but only the MI condition incorporated ingredients designed to affect a set of cognitive (i.e., motivation, dissonance, self-efficacy, norms, and drinking intentions) and behavioral (i.e., strategies) mechanisms of change. There were several notable findings. First, MI efficacy in reducing 6-week heavy drinking was mediated through three cognitive change processes (i.e., increased motivation and self-efficacy; decreased drinking intentions). For alcohol consequences, the significant mediator was decreased perceived drinking norms. Increased cognitive dissonance was a significant mediator of heavy drinking, but not of alcohol consequences at 3-month follow-up. Further, two behavioral strategies measured at 6 weeks (i.e., increased avoidance of and alternatives to drinking contexts) were found to mediate MI efficacy for heavy drinking and consequence outcomes at 3 months. By examining mechanisms in a young adult population with a different developmental context than the more commonly studied in the four-year college literature, the present study identifies within-session changes related to efficacy in an MI delivered to a high need and understudied population.

Cognitive Mediators of Short-term Follow up Outcomes

To date, changes in college student drinking norms have received the most consistent attention and support as processes important to MI-facilitated, young adult behavior change (e.g., Cronce & Larimer, 2011; Dotson, Dunn, & Bowers, 2015; Larimer & Cronce, 2002; Lewis & Neighbors, 2007). A recent review suggests that norms are most effective when locally-calibrated and gender-specific (Reid & Carey, 2015). In the MI protocol for this study, participants were presented with information about their own drinking quantity and frequency in contrast to a same-age, same-gender ‘typical young adult’. Our results support mediation of temporally-lagged, short-term consequences, but not heavy drinking. Therefore, outcomes for this community sample appear to be less influenced by the social comparison mechanism most often supported in college students (i.e., norms). Social comparison processes may have greater influence in the context of a college campus, where students live, work, and socialize nearly exclusively with student peers. That said, it is unknown whether more locally calibrated (e.g., state- or city-based) normative comparisons would have produced different mediation results.

Of the five cognitive process variables considered, short-term heavy drinking was reduced in MI through changes in mechanisms that have received mixed support in the college drinking literature, but more consistent support in the adult literature (Longabaugh et al., 2013). Specifically, increases in both motivation and self-efficacy and decreases in drinking intentions were predictive of reduced heavy drinking days at 6-week follow up. Motivation and intention findings are also consistent with a review of self-reported and observer-rated mechanisms of MI efficacy (Apodaca & Longabaugh, 2009), and a recent review of brief motivational interventions suggests that motivational processes may be particularly important when non-treatment seeking populations are the target of intervention (Gaume, McCambridge, Bertholet, & Daeppen, 2014). Our study results suggest that although these young adults were not seeking to change their drinking and risk behavior, they were quite amenable to exploring the issue; this speculation is supported by findings that perceptions targeted by the MI dialogue were impacted differentially in contrast to the time, attention, and expectancy-matched control (i.e., implementation at the a path consistently demonstrated).

Behavioral Mediators of Later Follow-up Outcomes

Only one pre-to-post cognitive change process was a significant mediator of one study outcome at 3-month follow up, while specific behavioral processes were associated with both heavy drinking and consequences. In this case, intermediate behavior changes (i.e., protective behavioral strategies) were measured at 6-weeks thus preserving the temporal sequence for the causal process model. In contrast to implementation results for cognitive change (i.e., all a paths supported), which were preserved at 6-week assessment, the MI condition differentially impacted two of seven behavioral strategies to limit drinking (i.e., seeking alternatives to drinking and avoiding drinking contexts). Both of these strategies mediated MI’s effects on heavy drinking, and avoidance mediated MI’s effects on negative consequences. Among college students, protective strategies have been studied in numerous trials with moderate support. Variability in methodology may account for some mixed results including different measures, temporal lags, and the extent to which MI targeted these behaviors (Prince, Carey, & Maisto, 2013). In particular, reviews suggest protective behaviors must be addressed within the interview protocol in order for implementation paths (i.e., a path) to be observed (Pearson, 2013). Behavioral strategies, as measured by a single summary score, have mediated consumption (Barnett, Murphy, Colby, & Monti, 2007) and consequences (Murphy et al., 2012) among college students receiving MI interventions. In the current trial, the MI therapist showed participants a list of strategies, “suggested by other young adults”, and invited the participant to discuss those they found most salient and potentially useful. As such, seeking alternatives and avoiding drinking contexts may be more relevant and feasible to this population than other strategies such as controlling rate of consumption or engaging in self-reward or punishment.

The Role of Cognitive Dissonance in Young Adult Behavior Change

While dissonance has remained largely unsupported in the college drinking literature (Reid & Carey, 2015), this cognitive change process was uniquely relevant to reduced heavy drinking in MI at the latest follow-up considered in this study. Importantly, while both conditions could elicit social desirability reporting by framing the interviews as related to potentially reducing alcohol consumption during young adult life transition, only the MI condition explicitly and compassionately examined this transition. Further, the MI condition attended to life goals, and provided feedback on recent time allocation to adult roles including vocational planning. These feedback elements are not typically included in standard MI approaches but are central to effective behavioral economic approaches to reducing drinking (Murphy et al., 2012). This feedback may have motivated young adults to develop alternatives to drinking and maximized discrepancy-related processes thought to be quite important to leveraging motivation among ambivalent individuals during the focusing phase of MI (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Given this novel finding, future research should consider dissonance and discrepancy more closely, particularly among young populations facing multiple role transitions.

Limitations, Recommendations, and Conclusions

This study has a number of strengths related to the methodological conditions needed for establishing a mechanism of change, but there are some limitations to consider. With respect to strengths, analyses examined temporally-lagged mechanisms of MI efficacy in contrast to a time, attention, and expectancy matched control (i.e. relaxation training). These conditions allow for satisfaction of the temporality, specificity, and plausibility criteria (Nock, 2007). While our follow-up time points (6 weeks and 3 months) are good for sensitive assessment of treatment-related mechanisms, they do not offer information about the durability of mediator effects. Next, it was somewhat puzzling that our analyses of the five cognitive mediators supported total indirect effects, but not unique indirect effects. This pattern of results might simply be a matter of reduced ability to detect unique and sometimes, small b path effects in our covariate-adjusted, multivariate OLS path models compared to our single variable OLS path models. We also required agreement across all bootstrap significance tests (i.e., bias-corrected and percentile). Therefore, it is unknown if our results would have shown more consistency with a larger sample or with more extensive (i.e., non-single item) measures of the constructs of interest. Finally, recruiting this sample of young adults from high schools and various community service and educational settings (e.g., GED programs or vocational training) could impact the generalizability of our results. However, we view this impact as positive because this sample may capture a high-risk, ethnically diverse, and understudied population of young adults that have a number of developmental and socioeconomic stressors that could place them at risk for persistent alcohol abuse and related consequences.

In this analysis of a clinical trial that demonstrated the value of MI for short-term heavy alcohol consumption and negative consequences among community, underage young adult drinkers, we found evidence that certain intervention ingredients targeting the mechanisms of interest were efficacious. Further, cognitive mechanisms (i.e., motivation, dissonance, self-efficacy) stimulated initial reductions in drinking, but sustained reductions in drinking and related problems required the acquisition of specific skills. Optimal methods for delivering corrective information on drinking norms with this population might require further study. Additionally, of the seven strategy types, only avoidance of drinking and seeking alternatives to drinking were active mechanisms arising from the collaborative behavior change discussion. Because our follow up was relatively short-term, studies with longer-term outcomes are still needed. Nevertheless, this study highlights that non-treatment seeking, young adult drinkers, who are not attending a traditional four-year college or university, are amenable to a brief MI. These young adults will change their behavior in response to content addressed in the MI intervention, and supported mechanisms are similar, though not the same, as those commonly supported for traditional college student alcohol users.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was funded by NIAAA grants #AA016000 awarded to S.M. Colby and #AA AA023194 awarded to M. Magill.

The authors express their appreciation to Cheryl A. Eaton, M.A. (Data Analyst), Barbara Engler, B.A. (Research Interventionist), Ryan Lantini, M.S. and Catherine Corno, B.A. (Research Assistants), and Alicia Justus, Ph.D. (Clinical Supervisor) whose work was invaluable to the successful implementation of this trial.

Footnotes

Public Health Impact

Young adults not involved in four-year college/university are an important population for public health intervention on problematic alcohol use. This study shows these individuals will change their drinking behavior in response to a brief motivational intervention and that intervention mechanisms of action are similar, though not the same, to those commonly supported for college drinkers.

References

- Apodaca T, Longabaugh R. Mechanisms of change in motivational interviewing: A review and preliminary evaluation of the evidence. Addiction. 2009;104(5):705–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Murphy JG, Colby SM, Monti PM. Efficacy of counselor vs. computer-delivered intervention with mandated college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2529–2548. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HC, Littleton JM. The alcohol withdrawal “kindling” phenomenon: Clinical and experimental findings. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1996;20(s8):121a–124a. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biener L, Abrams DB. The contemplation ladder: Validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychology. 1991;10:360–365. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.5.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Effects of a brief motivational intervention with college student drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:728–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslin FC, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Agrawal S. A comparison of a brief and long version of the Situational Confidence Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38(12):1211–1220. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs N. Estimation of the standard error and confidence interval of the indirect effect in multiple mediator models. Dissertation Abstracts International. 2006;37:4755B. [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Carey MP, DeMartini KS. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LJ, Elliott JC, Garey L, Carey MP. Face-to-face versus computer-delivered alcohol interventions for college drinkers: A meta-analytic review, 1998 to 2010. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32(8):690–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby SM, Orchowski L, Magill M, Murphy JG, Brazil LA, Apodaca TR, Kahler CW, Barnett NP. Brief motivational intervention for non-college underage drinkers: Harm reduction findings from a randomized controlled trial Manuscript under review. [Google Scholar]

- Cronce JM, Larimer ME. Individual-focused approaches to the prevention of college student drinking. Alcohol Research & Health: The Journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. 2011;34(2):210–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotson KB, Dunn ME, Bowers CA. Stand-alone personalized normative feedback for college student drinkers: a meta-analytic review, 2004 to 2014. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139518.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Better bootstrap confidence intervals. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1987;82(397):171–185. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, MacKinnon DP. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science. 2007;18(3):233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaume J, McCambridge J, Bertholet N, Daeppen JB. Mechanisms of action of brief alcohol interventions remain largely unknown-a narrative review. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:108. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. New York: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Houck JM, Moyers TB, Miller WR, Glynn LH, Hallgren KA. Motivational Interviewing Skill Code (MISC) version 2.5. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: The brief young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171940.95813.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Nock MK. Delineating mechanisms of change in child and adolescent therapy: Methodological issues and research recommendation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:1116–1129. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Pedersen ER, Earleywine M, Olsen H. Reducing heavy drinking in college males with the decisional balance: Analyzing an element of motivational interviewing. Addictive behaviors. 2006;31(2):254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment: A review of individual-focused strategies to reduce problematic alcohol consumption by college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14:148–163. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Fabiano PM, Stark CB, Geisner IM, Neighbors C. Personalized mailed feedback for college drinking prevention: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(2):285–293. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Optimizing personalized normative feedback: The use of gender-specific referents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(2):228–237. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R. The search for mechanisms of change in behavioral treatments for alcohol use disorders: A commentary. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(S3):21S–32S. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Magill M. Recent advances in behavioral addictions treatment: Focusing on mechanisms of change. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2011;13(5):382–389. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0220-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Magill M, Morgenstern J, Huebner R. Mechanisms of behavior change in treatment for alcohol and other drug use disorders. In: McCrady BS, Epstein EE, editors. Addictions: A Comprehensive Guidebook. 2. Ch. 25. USA: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. New York, NY: Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McNally AM, Palfai TP, Kahler CW. Motivational interventions for heavy drinking college students: Examining the role of discrepancy-related psychological processes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19(1):79–87. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Monti PM, Colby SM, O’Leary TA, editors. Adolescents, Alcohol, and Substance Abuse: Reaching Teens through Brief Interventions. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, McKay JR. Rethinking the paradigms that inform behavioral treatment research for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2007;102:1377–1389. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Miller WR, Ernst D. The Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity 3.0 (MITI 3.0) University of New Mexico, Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse and Addictions (CASAA); 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Borsari B, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Martens MP. A randomized controlled trial of a behavioral economic supplement to brief motivational interventions for college drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:876–886. doi: 10.1037/a0028763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK. Conceptual and design essentials for evaluating mechanisms of change. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(S3):4S–12S. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC. Psychometric Theory. 2. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MR. Use of alcohol protective behavioral strategies among college students: A critical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33(8):1025–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince MA, Carey KB, Maisto SA. Protective behavioral strategies for reducing alcohol involvement: A review of the methodological issues. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(7):2343–2351. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray AE, Kim SY, White HR, Larimer ME, Mun EY, Clarke N, … Huh D. When less is more and more is less in brief motivational interventions: Characteristics of intervention content and their associations with drinking outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28(4):1026–1040. doi: 10.1037/a0036593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid AE, Carey KB. Interventions to reduce college student drinking: State of the evidence for mechanisms of behavior change. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015;40:213–224. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biochemical Methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Alcohol Timeline Followback Users’ Manual. Toronto, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies; 2011. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11-4658. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 5. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner-Smith EE, Steinka-Fry KT, Hennessy EA, Lipsey MW, Winters KC. Can brief alcohol interventions for youth also address concurrent illicit drug use? Results from a meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2015;44(5):1011–1023. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0252-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollison SJ, Lee CM, Neighbors C, Neil TA, Olson ND, Larimer ME. Questions and reflections: The use of motivational interviewing microskills in a peer-led brief alcohol intervention for college students. Behavior Therapy. 2008;39:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werch CE, Gorman DR. Factor analysis of internal and external self-control practices for alcohol consumption. Psychological Reports. 1986;59(3):1207–1213. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1986.59.3.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW, Papadaratsakis V. Changes in substance use during the transition to adulthood: A comparison of college students and their noncollege age peers. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35(2):281–306. [Google Scholar]