Abstract

Objective

Young adult American veterans are at-risk for problematic alcohol use. However, they are unlikely to seek care and may drop out from lengthy multicomponent treatments when they do get care. This randomized controlled trial tested a very brief alcohol intervention delivered over the Internet to reach the population of young adult veterans to help reduce their drinking.

Method

Veterans (N=784) were recruited from Facebook and randomized to either a control condition or a personalized normative feedback (PNF) intervention seeking to correct drinking perceptions of gender-specific veteran peers.

Results

At immediate post-intervention, PNF participants reported greater reductions in their perceptions of peer drinking and in intentions to drink over the next month compared to control participants. At one-month follow-up, PNF participants reduced their drinking behavior and consequences to a significantly greater extent than controls. Specifically, PNF participants drank 3.4 fewer drinks per week, consumed 0.4 fewer drinks per occasion, binge drank on 1.0 fewer days, and experienced about 1.0 fewer consequences than control participants in the month after the intervention. Intervention effects for drinks per occasion were most pronounced among more problematic drinkers. Changes in perceived norms from baseline to one-month follow-up mediated intervention efficacy.

Conclusions

Though effects were assessed after only one-month, findings have potential to inform broader, population-level programs designed for young veterans to prevent escalation of drinking and development of long-term alcohol problems. Given the simplicity of the PNF approach and ease of administration, this intervention has the potential for a substantial impact on public health.

Keywords: online intervention, alcohol, young adult, veteran, normative feedback

Veterans from the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom; OEF/OIF) are at high risk for hazardous drinking and more severe alcohol use disorders (AUDs). For example, between 2001 and 2010, approximately 1 in 10 veterans from these conflicts who sought care from the Veterans Healthcare System (VHA) met criteria for an AUD (Seal et al., 2011). Whether or not they meet diagnostic criteria for an AUD, studies report that between 22% and 40% of these veterans drink at heavy levels that place them at risk for consequences such as poor family relationships, employment difficulties, and physical health complaints (Calhoun, Elter, Jones, Kudler, & Straits-Troster, 2008; Erbes, Westermeyer, Engdahl, & Johnsen, 2007; Hawkins, Lapham, Kivlahan, & Bradley, 2010; McDevitt-Murphy et al., 2010). Young adult veterans are most at risk, with this group drinking at heavier rates than older veterans of the same conflicts (Seal et al., 2011).

Despite the prevalence of heavy drinking and consequences associated with such use, few young adult veterans seek care for alcohol use. OEF/OIF veterans have access to private care in the community and most are eligible for substance use and mental health coverage at the VHA, which on the whole has demonstrated quality of behavioral health care comparable to or better than care in the private sector (Congressional Budget Office, 2009; Watkins et al., 2011). Yet, rates of substance use treatment seeking among heavy drinking OEF/OIF veterans are low (Burnett-Zeigler et al., 2011; Erbes et al., 2007; Golub, Vazan, Bennett, & Liberty, 2013). Commonly cited reasons for not seeking care include inconvenience of appointments, concerns about high costs, perceived stigma from peers, and the belief in one’s own ability to handle symptoms (DeViva et al., 2015; Fox, Meyer, & Vogt, 2015; Garcia et al., 2014; Hoge et al., 2004; Pietrzak, Johnson, Goldstein, Malley, & Southwick, 2009; Schell & Marshall, 2008; Vogt, 2011). Morever, approximately one-third of returning OEF/OIF veterans live in rural areas that may limit accessibility to hospitals and clinics within the VHA or other substance use treatment centers (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2012). Thus, developing efficacious prevention approaches outside of traditional treatment settings are of paramount importance to reach these young veterans early before their drinking escalates to problematic use.

Internet-based treatments may help young veterans overcome barriers to face-to-face care and receive needed services they may not otherwise pursue. Despite the promise of online interventions with veterans, these programs are often lengthy and characterized by high attrition. For example, two studies (Pemberton et al., 2011; Williams, Herman-Stahl, Calvin, Pemberton, & Bradshaw, 2009) examined the efficacy of the multicomponent, Internet-hosted Drinker’s Check-Up (Hester, Squires, & Delaney, 2005). Whereas reductions in drinking were found at one-month post-intervention, nearly a quarter of the participants failed to complete the program, which took, on average, 90 minutes to finish. Also, VHA-affiliated researchers delivered a promising online 8-week intervention to reduce drinking and alleviate symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in OEF/OIF veterans. Yet, only half of the intervention participants completed at least four of the eight modules, and only one-third completed all modules (Brief, Rubin, Enggasser, Roy, & Keane, 2011; Brief et al., 2013). The development of even shorter online interventions can increase treatment reach and evidence shows that very brief interventions can yield benefits comparable to longer ones (Tanner-Smith & Lipsey, 2015).

One possible approach to reducing the length of multisession programs is to isolate the essential component(s) of the programs and determine if a single dose of each component yields promising effects on drinking outcomes. Correcting young adult perceptions of peer drinking is a component often included in brief online interventions with young people (Dedert et al., 2014). Several evaluations of brief multicomponent interventions targeting military and non-military adults report that correcting these perceptions may be more important than other intervention foci such as listing consequences of drinking or offering information about risk factors of drinking (Carey, Henson, Carey, & Maisto, 2010; Dotson, Dunn, & Bowers, 2015; Walker et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2009; Wood, Capone, Laforge, Erickson, & Brand, 2007).

This premise of social norms approaches is based on theory and research which suggests that individual behavior, including drinking behavior, is influenced by perceptions regarding group behavioral or attitudinal norms (Berkowitz & Perkins, 1986; Borsari & Carey, 2003). The belief that others are drinking heavily can influence one’s own drinking behavior to match a perceived norm that is most often an overestimation of the group’s actual behavior. Thus, personalized normative feedback (PNF) approaches focus on challenging misperceptions of peer behavior by presenting individuals with their misperceptions of a group (e.g., other college students at one’s university) alongside the actual drinking of the group alongside one’s own drinking behavior (Chan, Neighbors, Gilson, Larimer, & Marlatt, 2007). Thus, PNF affords individuals a chance to see how their perceptions compare to the actual drinking of a relevant reference group (e.g., “other students don’t drink nearly as much as I thought”) and learn how their own drinking compares to the behavior of a relevant reference group (e.g., “I drink much more than other male students”). In this format, PNF has been used in multicomponent interventions and as a stand-alone approach to prevent and reduce heavy alcohol use among young adults (Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & DeMartini, 2007; Cronce & Larimer, 2011; Dedert et al., 2014; Doumas & Hannah, 2008; Hester et al., 2005; Miller et al., 2013; Riper et al., 2009; Walters & Neighbors, 2005; White, 2006).

Recent research with veterans recruited from the VHA has used PNF as part of in-person multicomponent approaches to reduce heavy drinking with this group (Cucciare, Weingardt, Ghaus, Boden, & Frayne, 2013; Martens, Cadigan, Rogers, & Osborn, 2015; McDevitt-Murphy et al., 2014). These studies, which include PNF as well as multiple other components (e.g., listing the individual’s consequences from drinking; providing information about risk factors of drinking and mental health problems), reported mixed findings. For example, Martens and colleagues (2015) found that abstainers receiving a brief intervention at the VHA were more likely to remain abstinent at six month follow-up compared to abstainers who received an information only condition. Yet, the brief intervention was not superior to the information only condition on alcohol use outcomes among drinkers. Cucciare and colleagues (2013) found reductions in drinking at six month follow-up among all enrolled veteran participants recruited from primary care clinics at the VHA. However, they observed no significant differences among veterans receiving information on recommended drinking limits and health effects of alcohol and those receiving this information supplemented by a PNF-based brief intervention. McDevitt-Murphy and colleagues (2014) found that personalized feedback that included PNF delivered with or without a complementary Motivational Interviewing (MI) counseling session led to reductions in drinking outcomes among enrolled veteran drinkers at the VHA. Thus, it is clear that more research on brief PNF-based interventions with young veterans is necessary. To date, no study has yet to test PNF alone with young veterans recruited via the Internet outside the VHA. This would provide support for an empirically-informed approach that can reach veterans in the community outside of VHA clinics.

PNF, as a stand-alone intervention, appears to offer promise for young veterans at risk for problematic drinking. First, evidence supports the theoretical underpinnings of the approach, which assume that if PNF is going to work, individuals receiving the intervention need to overestimate the behavior of their peers and these overestimations should have an impact on their own behavior. Both veterans and service members greatly misperceive the drinking behavior of their peers and their perceptions are associated with personal drinking behavior and consequences (Miller et al., 2016; Neighbors et al., 2014; Pedersen, Marshall, Schell, & Neighbors, 2016b). Second, though no study has looked at PNF approaches in the absence of other components with military groups, two studies have found that changes in normative perceptions about the drinking behavior of other active duty service members was the only factor that mediated changes in drinking behavior over time in multicomponent interventions (Walker et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2009). Although this suggests changes in norms are the driving factor of change in lengthier multicomponent interventions, no study to date has examined how PNF alone, removed from any other components typical to multicomponent approaches to reduce heavy drinking, can affect drinking behavior among young veterans.

The Present Study

For this study, we developed a stand-alone PNF intervention and tested the efficacy of the approach with a large sample of 784 young adult veteran drinkers recruited from the Internet. Given that intervention length may affect both treatment engagement and attrition, we sought to determine the promise of a single session, very brief PNF intervention. Our developed PNF intervention greatly decreases the length of traditional in-person and online interventions, reducing length of a typical multicomponent intervention lasting one hour or more per session down to a single session PNF intervention that required as little as 5–10 minutes. We recruited from the widely popular website Facebook to increase the reach to young veterans in the community; thereby potentially attracting persons not actively searching for alcohol treatment and those who may never have sought care otherwise. We evaluated the immediate efficacy of the intervention on changing perceived norms and reducing intentions to drink after viewing feedback. We then evaluated the efficacy of the intervention in reducing alcohol use (drinks per week, drinks per occasion, binge drinking days) and alcohol use-related consequences one-month post-intervention.

To gain a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying intervention efficacy, we evaluated whether reductions in perceived norms served as a sufficient explanatory mechanism for any intervention effects on alcohol-related outcomes. We then explored whether the impact of the intervention varied as a function of meaningful subgroups such as gender, level of drinking problems, mental health symptom severity (depression, PTSD), and closeness to the gender-specific peers targeted in the PNF. Moderators were selected due to theoretical and empirical rationale. There are differential drinking patterns between genders in military samples (Ramchand et al., 2011; Stahre, Brewer, Fonseca, & Naimi, 2009) and therefore men and women may be impacted by the intervention differently. We explored whether the intervention may be appropriate for those at higher severity of drinking, given that more severe drinkers may warrant a lengthier or more intensive approach beyond a very brief intervention (Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993). Due to the prevalence of comorbid mental health problems and heavy drinking among young veterans (Seal et al., 2011), we evaluated whether screening positive for two of the most common problems in this population (depression, PTSD) served as moderators of intervention efficacy. Lastly, we evaluated whether closeness to the referent targeted in the PNF moderated intervention efficacy. This is important as research indicates that the closer one feels to their reference group, the more impactful the perceived norm of that group’s behavior and attitudes will be on their behavior (Neighbors et al., 2010).

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Participants were recruited over the course of two weeks from Facebook using targeted advertisements; for example, ads were displayed to individuals who expressed an interest in or “liked” specific Facebook content such as the page for “afterdeployment.org” or “Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of American.” Ads were worded in a way to attract veteran drinkers not specifically looking for treatment and to avoid deterring treatment resistant veterans from clicking on ads (e.g., “U.S. veterans aged 18–34. Earn $45 for a confidential online study about alcohol”). Family members or friends could also see ads and send a link to the screening survey to eligible veterans. Eligibility criteria for the study included (1) U.S. veteran separated from the Air Force, Army, Marine Corps, or Navy, (2) between the ages of 18 and 34, (3) and score on the 10-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (Saunders et al., 1993) of 3 or greater for women and 4 or greater for men (Bradley et al., 2003; 1998). These AUDIT criteria values were specified as low to include participants in the study who drank at both moderate to high levels that were at-risk for hazardous or problem drinking. Details about the recruitment strategy are discussed in detail elsewhere (Pedersen, Naranjo, & Marshall, 2016c).

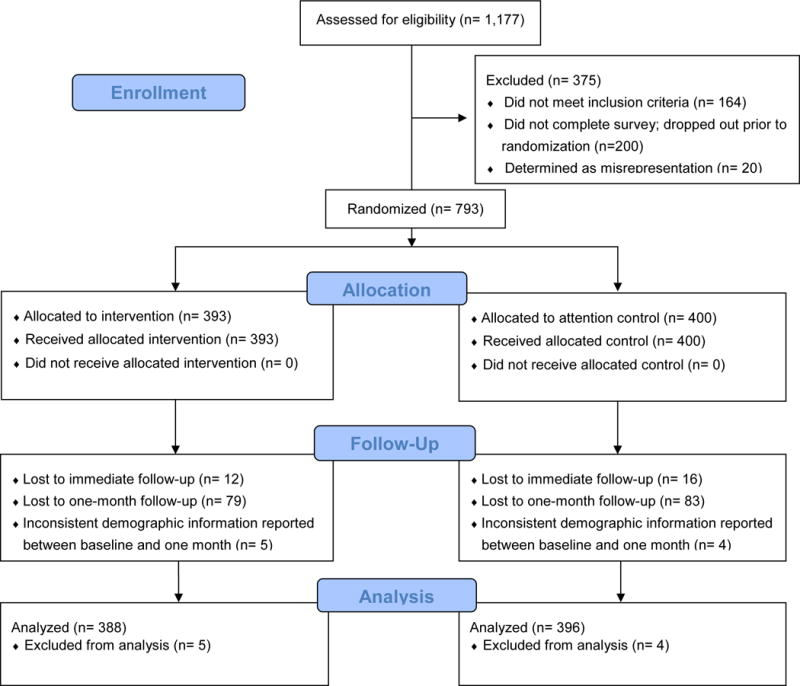

A total of 2,312 individuals clicked on ads and reached an online consent form for the study, of which 1,127 exited the survey without responding to the consent and 8 declined to give consent. Thus, 1,177 completed a brief screening questionnaire (demographics, AUDIT) to determine eligibility. A total of 175 participants were screened out of the study due to not meeting eligibility criteria (n = 164) or due to endorsing inconsistent responses on items we included to remove individuals posing as veterans to obtain incentives (e.g., branch, rank, pay grade, and age needed to be consistent; n = 11). Methods such as these have been successful in weeding out misrepresenters and validating data from Internet studies in prior work (Kramer et al., 2014; Pedersen et al., 2015) and are described in more detail for this study in other work (Pedersen et al., 2016c). Of the 1,002 participants that began the baseline survey, 200 did not progress past initial questions on the survey and 9 did not pass verification checks (e.g., same participant attempted to access the survey multiple times, participant completed the survey too quickly to be valid), resulting in 793 randomized to either PNF based on gender-specific peers (n = 393) or attention control feedback about gender-specific peers’ video game playing behavior (n = 400). Participants received feedback after a 15-minute baseline survey, then after feedback they completed a two-minute immediate post-intervention survey to assess immediate changes in perceived norms and intended drinking behavior. One month later, participants completed an online follow-up survey to assess drinking outcomes. Nine of the 793 participants who completed the one-month follow-up had inconsistent responses to items on gender, branch, and/or rank between baseline and follow-up. As data from these participants were unreliable, we removed them from the analytic sample, resulting in a final sample of N = 784 (see Figure 1). Completion rates for the follow-up were based on the sample removing these nine participants: N = 756 (96.4%) at immediate post-intervention and N = 622 (79.3%) at one-month follow-up.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram

Measures

Detailed information about the measures used in this study, including documentation of a priori outcome measures, can be found in a research protocol paper published elsewhere (Pedersen, Marshall, & Schell, 2016a). We also summarize these measures below.

Demographics, military characteristics, and treatment

Demographics and military characteristics were assessed to describe the sample (age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, branch of service, combat experience, years in the armed forces prior to discharge). Items were also assessed at screening to help determine validity of the responses and reduce misrepresentation (rank, pay grade at discharge, occupation in the military). Participants also indicated the device on which they completed the surveys and viewed the feedback (i.e., mobile phone, computer/tablet/other). Participants reported on whether they had received any VHA care for any reason (e.g., physical health concerns, compensation and pension review) since discharge, any alcohol or other substance use treatment services (at VHA or elsewhere) since discharge, and any mental health treatment services (at VHA or elsewhere) since discharge.

Drinking behavior and perceptions

One month outcomes were specified as drinking behavior (drinks per week, average drinks per occasion, binge drinking days) and alcohol-related consequences and were assessed at baseline and at one-month follow-up. Drinks per week and average drinks in the past 30 days were assessed using the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985). Participants completed a single item to assess frequency of binge drinking (i.e., number of times one consumed 5/4 (men/women) or more drinks in one sitting during the past month). Number of alcohol-related consequences in the past 30 days were assessed with the 24-item Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (Kahler, Hustad, Barnett, Strong, & Borsari, 2008; Kahler, Strong, & Read, 2005). This instrument has been used in prior work with young adult veterans (Miller et al., 2016). “Drinks per week” was capped at 105 drinks (for two participants at baseline and one participant at one month). “Average drinks per occasion” was capped at 15 drinks (for four participants at baseline and one participant at one month). Intended drinking behavior in the next 30 days was assessed at baseline and post-intervention using a modification of the DDQ. Perceptions about alcohol use at all three time points were assessed with the Drinking Norms Rating Form (DNRF; Baer, Stacy, & Larimer, 1991), which is a modification of the DDQ that asks participants to consider “the drinking of a typical [same-gender] veteran aged 18 to 34” when filling out the measure. Information from the DNRF at baseline regarding perceived total drinks per weeks and average drinks were also collected for inclusion as content in the PNF condition, as was a single item where participants indicated the number of days they perceived that a typical [same-gender] veteran binge drank in the past 30 days.

Potential moderators

To examine potential intervention moderators, participants completed measures assessing drinking severity, severity of mental health problems (PTSD, depression), and perceived closeness to the PNF reference target. The 10-item AUDIT, which was used for screening purposes as well (Saunders et al., 1993; range = 3 to 37; α = 0.84), was used to assess alcohol use severity in moderation analyses. Symptoms of PTSD and depression were assessed with the PTSD Checklist for DSM-V (PCL-5; range = 0 to 80; α = 0.97) (Weathers et al., 2013) and the Patient Health Questionnaire 8-item (PHQ-8) (Kroenke et al., 2009; range = 0 to 24; α = 0.93), respectively. An adaptation of the Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale (Aron, Aron, & Smollan, 1992) assessed how close participants felt to other gender-specific veterans (Mashek, Cannaday, & Tangney, 2007; Tropp & Wright, 2001).

Control condition information

At baseline, control participants completed two measures of video game playing as well as perceptions of the video game playing behaviors of other same gender veterans. Items assessed video game playing days in the past month and typical hours per day spent playing games. This information was used in the attention control condition.

Intervention Conditions

An extensive description of the PNF and the video game control conditions, as well as rationale for including or excluding specific content (e.g., decision to use gender-specific norms as opposed to other referent group norms, decision to target behavioral norms only and not attitudinal norms) are presented elsewhere (Pedersen et al., 2016a; 2016b). In brief, the PNF contained gender-specific norms for drinks per week, average drinks per occasion, and binge drinking days collected from over 1,000 young adult veterans in our prior work (Pedersen et al., 2016b). These norms were collected from an Internet-based sample that was representative of the broader young adult veteran population with respect to most demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, income level, years of education, marital status). However, the sample overrepresented persons of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity and veterans of the Army and Marine Corps. In contrast, African-Americans were underrepresented as were veterans of the Air Force and Navy (see Pedersen et al., 2015 for more detail about the normative sample). Thus, presented norms were based on data weighted with respect to race/ethnicity and branch of service. Prior to the presentation of norms, PNF participants read information describing social norms theory (e.g., how perceptions are perpetuated through attention to behavior outside the norm and ignoring of “typical behavior”). Attention control participants received gender-specific feedback for days video games were played per week, hours per day video games were played, and hours per week video games were played. All participants also saw a description of the sample (e.g., mean age, race/ethnicity breakdown) used to provide the normative data to be transparent about the origin of the norms and increase believability of the information presented.

Data analytic plan

To investigate the effectiveness of randomization in producing equivalent groups, we investigated differences between groups on baseline characteristics including demographics, military characteristics, and treatment factors using two-sample t-tests and chi-squared tests with an alpha of 0.05. To address the possibility of differential attrition over the course of the study, we created inverse probability weights, and used generalized boosted models (GBM) to obtain robust estimates of individual probabilities of missingness (McCaffrey, Ridgeway, & Morral, 2004). We used the twang package in R (Ridgeway, McCaffrey, Morral, Burgette, & Griffin, 2016) and included all baseline characteristics and baseline measures as predictors in our missingness models. Outcome-specific weights were used to adjust for differential missingness across outcomes, and were constructed as the inverse probability of these individual missingness probabilities and used when estimating treatment effects (Brick & Kalton, 1996; Little & Rubin, 2014; Seaman & White, 2013; Vandecasteele & Debels, 2007). Specifically, individual outcome-specific weights were calculated as 1/(1-p) where p is the estimated probability that an outcome is missing; that is, individuals with a higher probability of missingness are given more weight and individuals with a lower probability of missingness are given less weight. As a sensitivity analysis, analyses were also conducted using a complete case approach and a multiple imputation approach; the pattern of results was very similar.

To examine intervention effects, we used weighted linear regression models with the outcome value at follow-up as the dependent variable. We also included an intervention indicator as the primary independent variable, while controlling for the outcome value at baseline, age, gender, baseline severity of drinking on the AUDIT, and device on which participants completed the baseline survey and viewed the feedback (i.e., mobile vs. non mobile device). The latter two variables were included due to observed differences between the intervention and control group at baseline (see Results section and Table 1). All standard error (SE) estimates for regression coefficients were estimated using bootstrap-resampling (Efron & Tibshirani, 1993) due to non-normally distributed error. Cohen’s d effect sizes (Cohen, 1992) were calculated with the equation .

Table 1.

Demographic, military characteristics, treatment factors, and moderators at baseline

| Control n=396 Mean (SD) or percentage |

Intervention n = 388 Mean (SD) or percentage |

p-value (t-test or χ2 test) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 28.9 (3.5) | 28.8 (3.3) | 0.792 |

|

| |||

| Male gender | 82.3% | 84.3% | 0.523 |

|

| |||

| Race/ethnicitya | 0.652 | ||

| White | 76.5% | 80.7% | |

| Hispanic | 11.6% | 9.3% | |

| Black or African American | 4.5% | 3.1% | |

| Asian | 1.0% | 0.8% | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2.0% | 1.8% | |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 0.3% | 0.5% | |

| More than one race/ethnicity | 2.8% | 3.6% | |

| Other | 1.0% | 0.3% | |

|

| |||

| Education | 0.476 | ||

| Some high school | 0.3% | 0.3% | |

| High school graduate | 22.0% | 18.3% | |

| Some college | 59.1% | 59.5% | |

| College graduate | 18.7% | 21.9% | |

|

| |||

| Married | 49.7% | 52.8% | 0.428 |

|

| |||

| Branch | 0.307 | ||

| Air Force | 11.6% | 8.0% | |

| Army | 59.8% | 59.5% | |

| Marines | 20.5% | 23.2% | |

| Navy | 8.1% | 9.3% | |

|

| |||

| Device used to complete survey | 0.009 | ||

| Mobile phone | 80.8% | 72.7% | |

| Computer/tablet/other | 19.2% | 27.3% | |

|

| |||

| Years in armed forces before discharge | 5.6 (2.7) | 5.6 (2.9) | 0.951 |

|

| |||

| Any combat experience | 82.1% | 82.5% | 0.957 |

|

| |||

| Any VHA use since discharge | 68.9% | 69.6% | 0.905 |

|

| |||

| Mental health treatment since discharge | 57.3% | 55.9% | 0.747 |

|

| |||

| Alcohol or other substance use treatment since discharge | 24.2% | 18.8% | 0.078 |

|

| |||

| Drinking severity1 | 13.0 (7.2) | 11.9 (6.8) | 0.025 |

|

| |||

| PTSD symptoms2 (continuous) | 30.7 (23.5) | 27.2 (22.3) | 0.035 |

|

| |||

| PTSD symptoms2 (dichotomous, ≥ 33) | 42.2% | 36.3% | 0.110 |

|

| |||

| Depression symptoms3 (continuous) | 10.2 (7.3) | 9.2 (7.1) | 0.039 |

|

| |||

| Depression symptoms3 (dichotomous, ≥ 10) | 51.3% | 41.8% | 0.009 |

|

| |||

| Closeness to the PNF reference target4 | 4.3 (1.9) | 4.4 (1.8) | 0.677 |

.03% missing for race/ethnicity in the control group.

10-item AUDIT;

PTSD Checklist for DSM-V (PCL-5);

Patient Health Questionnaire 8-item (PHQ-8);

adaptation of the Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale

Mediation analyses were performed for all one month outcomes that demonstrated significant intervention effects. To assess mediation, the potential mediator (i.e., changes in perceived drinks per week and changes in perceived drinks per occasion from baseline to immediate follow-up and from baseline to one-month follow-up) was included as an independent variable in the weighted regression model described above. Mediation was quantified using the absolute change in the regression coefficient for treatment when the mediator was added to the weighted regression model and the proportion of treatment effect explained by the mediator. Standard errors and p-values for both quantities were calculated using bootstrap-resampling (Shrout & Bolger, 2002).

Moderation analyses were performed by including the moderator of interest as an independent variable in the weighted regression model described above, and including an interaction between the moderator and the intervention indicator. Standard errors and p-values for the interaction effect were again calculated using bootstrap-resampling. A significant interaction effect was taken as evidence of intervention effect moderation. Power calculations were conducted a priori and indicated that all planned analyses had adequate power to detect small-to-medium effects sizes (Cohen, 1992).

Results

Sample Description

Table 1 contains a description of the baseline characteristics of the sample. The sample was primarily male (83%) and reported a mean age around 29 years old. Most participants were White and had completed some college. About half were married and most participants were formerly in the Army or Marine Corps. Approximately three-quarters of participants used their mobile phones to take the baseline survey and view the feedback; however, control participants were significantly more likely to use their mobile phones for these purposes (χ2=6.8, p < .01). About 82% reported some combat experience during their service and participants served about 5.6 years on average prior to discharge. Nearly half (47%) of the sample screened positive for depression and 39% screened positive for PTSD. Since discharge, 69% had visited a VHA clinic for any reason, while 57% attended at least one appointment for a mental health concern since discharge and 21% attended at least one appointment for an alcohol or other substance use concern since discharge. Due to the significant difference in device at baseline (despite randomization), this variable was controlled for when estimating treatment effects.

In spite of randomization, there were small but statistically significant differences between groups on pre-randomization measures of drinking severity, PTSD symptoms and depression symptoms (see Table 1); however, the difference between groups in PTSD and depression symptoms was no longer significant after controlling for drinking severity. Therefore, all regression analyses controlled for drinking severity (in addition to device as stated earlier). With the exception of one individual in the control group missing race/ethnicity (see Table 1), there was no missingness of baseline characteristics or explored moderators. Missingness rates of immediate outcomes and mediators ranged from 4–8% and missingness of one-month outcomes ranged from 20–27%; these missing data were handled using inverse probability weighted as described above.

Main Intervention Effects

Immediate intervention effects

Significant main effects for the intervention were observed with respect to reductions in perceived norms and intended drinking outcomes. The top portion of Table 2 contains the means at baseline and immediate follow-up for the intervention and control condition participants. Compared to the control condition, PNF participants perceived that their gender-specific peers drank 11.2 fewer drinks per week (d = 0.70) and 1.1 fewer drinks per occasion (d = 0.49) at immediate post-intervention (p < 0.001 for both). Relative to control group, PNF participants also reported intending to drink 2.9 fewer drinks per week (d = 0.20) and 0.4 fewer drinks per occasion (d = 0.17) at immediate follow-up (p < 0.001 for both).

Table 2.

Immediate and One-Month Follow-up Intervention Effects

| Control Group at Baseline Mean (SD) |

Control Group at Follow-up Mean (SD) |

Intervention Group at Baseline Mean (SD) |

Intervention Group at Follow-up Mean (SD) |

Intervention Effecta Coefficient(SE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate Changes in Perceptions of Peer Behavior | |||||

| Perceived drinks per week | 31.7 (21.4) | 26 (18.0) | 30.4 (20.6) | 14.3 (11.1) | −11.2 (0.9) *** |

| Perceived average drinks per occasion | 5.1 (3.0) | 4.3 (2.5) | 4.9 (2.9) | 3.1 (1.8) | −1.1 (0.1) *** |

|

| |||||

| Immediate Changes in Intentions to Drink Alcohol | |||||

| Intended total weekly drinks | 16.2 (17.0) | 15.5 (16.5) | 14.5 (16.0) | 11.3 (11.2) | −2.9 (0.6) *** |

| Intended average drinks | 3.6 (2.8) | 3.4 (2.6) | 3.5 (2.8) | 2.9 (2.2) | −0.4 (0.1) *** |

|

| |||||

| One-month Changes in Perceptions of Peer Behavior | |||||

| Perceived drinks per week | 31.7 (21.4) | 22.4 (16.7) | 30.4 (20.6) | 14.9 (12.6) | −7.1 (1.0) *** |

| Perceived average drinks per occasion | 5.1 (3.0) | 3.8 (2.4) | 4.9 (2.9) | 3.2 (2.1) | −0.6 (0.2) *** |

|

| |||||

| One-month Changes in Alcohol Use | |||||

| Drinks per week | 19.4 (18.4) | 13.4 (14.8) | 17.6 (16.9) | 9.9 (12.1) | −3.4 (0.9) *** |

| Average drinks per occasion | 4.2 (2.8) | 3.0 (2.4) | 4.1 (2.8) | 2.6 (2.1) | −0.4 (0.2) * |

| Number of binge drinking days | 6.4 (7.9) | 4.1 (6.1) | 5.4 (7.1) | 2.7 (4.8) | −1.0 (0.4) ** |

|

| |||||

| One-month Changes in Alcohol-related Consequences | |||||

| Number of alcohol-related consequences | 7.8 (6.7) | 5.3 (6.3) | 7.2 (6.8) | 3.8 (5.6) | −1.0 (0.4) ** |

Note:

p < .01,

p < .001;

intervention effect estimate reflects the regression coefficient for the intervention indicator from a weighted regression model controlling for age, gender, baseline drinking severity, device, and baseline measure of the outcome

One-month intervention effects

Significant main effects of the intervention at one-month follow-up were observed for perceived norms and for all targeted drinking outcomes. The bottom portion of Table 2 contains the means at baseline and one-month follow-up for the intervention and control condition participants. Compared to control participants, PNF participants perceived that their gender-specific peers drank 7.1 fewer drinks per week (d = 0.47) and 0.6 fewer drinks per occasion (d = 0.27) at one-month follow-up (p < 0.001 for both). Compared to controls, PNF participants drank 3.4 fewer drinks per week (d = 0.25), consumed 0.4 fewer drinks per occasion (d = 0.17), binge drank on 1.0 fewer days (d = 0.18), and experienced about 1.0 fewer consequence (d = 0.17) one month after the intervention (all p < 0.05).

Mediation Effects

We tested for mediation for all four one-month drinking outcomes since we found significant main intervention effects on all outcomes. None of the hypothesized mediation effects for changes in perceived norms from baseline to immediate post-intervention were statistically significant (results not shown; available from the corresponding author). However, we did observe mediation effects for both perceived norms mediators at one-month (changes in perceived drinks per week, changes in perceived average drinks per occasion) for three of the four drinking outcomes (see Table 3). For example, change in perceived drinks per week from baseline to one month explained 22% (95% CI: 8.7% – 50.9%) of the intervention effect on drinks per week, 23% (95% CI: 2.5% – 100.7%) of the intervention effect on drinks per occasion and 25% (95% CI: 5.7% – 101.2%) of the intervention effect on consequences, all at one month after the intervention.

Table 3.

One Month Mediation Intervention Effects

| One-month Outcomea | Intervention Estimate (SE) | Mediator Estimate (SE) | Indirect Effectb Estimate (95% CI) | Proportion of Treatmentc Effect Explained Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator: Change in perceived drinks per week from baseline to one month | ||||

| Drinks per week | −2.63 (0.83)** | 0.11 (0.03)*** | −0.73 (−1.4, −0.29)*** | 0.22 (0.09, 0.51)*** |

| Average drinks per occasion | −0.31 (0.17) | 0.01 (0.01)* | −0.09 (−0.19, −0.01)* | 0.23 (0.02, 1.01)* |

| Number of binge drinking days | −0.93 (0.39)* | 0.02 (0.01) | −0.10 (−0.31, 0.04) | 0.10 (−0.06, 0.47) |

| Number of alcohol-related consequences | −0.77 (0.4) | 0.04 (0.01)** | −0.25 (−0.49, −0.08)* | 0.25 (0.06, 1.01)* |

| Mediator: Change in perceived average drinks per occasion from baseline to one month | ||||

| Drinks per week | −3.00 (0.81)*** | 0.66 (0.19)*** | −0.36 (−0.84, −0.07)** | 0.11 (0.02, 0.29)** |

| Average drinks per occasion | −0.35 (0.17)* | 0.09 (0.04)* | −0.05 (−0.12, −0.002)* | 0.12 (0.002, 0.58)* |

| Number of binge drinking days | −0.99 (0.38)** | 0.09 (0.09) | −0.04 (−0.15, 0.04) | 0.04 (−0.05, 0.21) |

| Number of alcohol-related consequences | −0.88 (0.4)* | 0.24 (0.08)** | −0.14 (−0.32, −0.02)* | 0.14 (0.02, 0.58)* |

Note:

p < .01,

p < .001;

Regression estimates are from a weighted regression model with predictors: baseline measure of the outcome, intervention, mediator, age, gender, baseline drinking severity, and device.

Indirect Effect is defined as the change in the regression coefficient for the intervention when the mediator is added to the model.

Proportion of treatment effect explained is 1-A/B where A is the regression coefficient for the intervention from the model with the mediator and B is the regression coefficient for the intervention from the model without the mediator

Moderation Effects

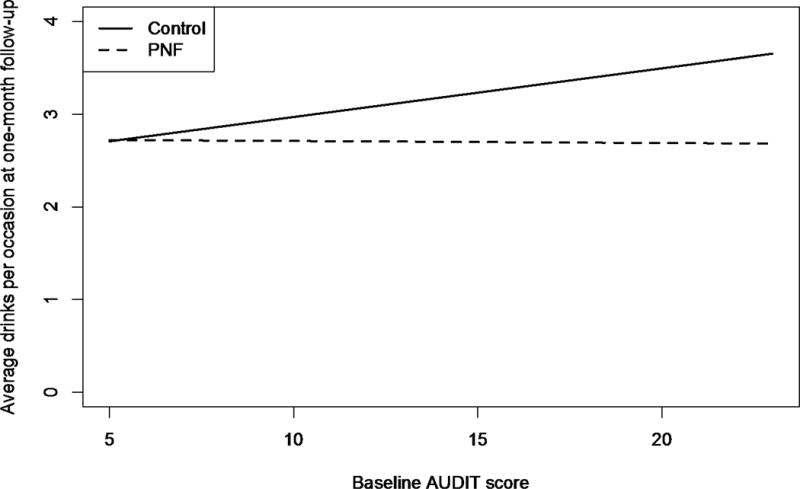

Moderators included gender, baseline drinking severity (measured using the AUDIT), baseline PTSD symptoms (measured using the PCL, examined using continuous PCL score as well as dichotomous PCL with a cutoff of 33 [Wortmann et al., 2016]), baseline depression symptoms (measured using the PHQ-8, examined using continuous PHQ score as well as dichotomous PHQ with a cutoff of 10 [Kroenke et al., 2009]), and baseline closeness to other gender-specific veteran peers. In the model examining baseline drinking severity as a potential moderator, no statistically significant interaction effects were found for drinks per week, binge-drinking days, or alcohol-related consequences. However, the effect of the intervention on average drinks per occasion was moderated by drinking severity (interaction coefficient = −0.06, SE = 0.03 p = 0.04) such that PNF participants who had higher baseline drinking severity benefited most from the intervention (see Figure 2). None of the other investigated interaction effects were statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Interaction Effect for Treatment × Baseline AUDIT scores for Average Drinks per Occasion Outcome at One-month Follow-up

Discussion

This intervention study utilized a novel methodology to recruit 784 young adult veteran participants through Facebook to deliver a very brief PNF program entirely over the Internet. The intervention was associated with a significant reduction of all targeted drinking outcomes at one-month follow-up, relative to an attention-only comparison group. Specifically, weekly drinking, average drinks per occasion, number of binge drinking days, and number of alcohol-related consequences were substantially reduced for the intervention participants, compared to controls, in the month following the intervention. Both perceived norms and intended drinking were reduced at immediate post-intervention to a significantly greater degree for the PNF participants than for the control participants. We did not find statistically significant evidence that reductions in perceived norms from baseline to immediate follow-up mediated the effects of the intervention at one-month follow-up. However, observed changes in perceived norms from baseline to one-month follow-up mediated the one-month effects of the intervention for drinks per week, drinks per occasion, and alcohol-related consequences. Multiple randomized controlled trials evaluating PNF in young people have similarly found that changes in perceived norms are a mechanism of behavior change in stand-alone PNF interventions and in brief interventions that include PNF components (Miller & Prentice, 2016; Reid & Carey, 2015). The changes at immediate post-intervention likely served as a memory test, as participants were asked to recall the drinking norms they had seen immediately prior to reassessment of perceived norms. However, the changes in perceived norms from baseline to one-month follow-up likely represented more stable retention of the actual norms, which also may have allowed participants to observe these newly learned norms in their environment during the follow-up month. These observations confirming the newly learned norm that their peers drink less than they once thought may have contributed to sustained reductions during the month after the intervention.

In general, intervention effects did not vary based on meaningful subpopulations. The exception was that the intervention’s effects on average drinks per occasion were larger for more problematic baseline drinkers. Prior work with college students has indicated that PNF can be particularly helpful at reducing drinking among heavier drinkers (Dotson et al., 2015; Lewis & Neighbors, 2006; Miller et al., 2013), which is promising as this approach was tailored to reduce alcohol use among a heavy drinking group resistant to seek care. We did not observe a statistically significant moderation effect for closeness to peer referents presented in the PNF. This may suggest that using same-gender veterans as the normative reference group may be adequate to produce behavior change even when “closer” social groups may exist for the participant (Pedersen et al., 2016a; 2016b). Moreover, the intervention did not appear to work particularly worse or better for men or women, or for those with varying degrees of severity of PTSD and depression symptoms. This suggests that PNF may be appropriate even among the young veteran population, which is primarily male and where comorbidity is a concern (Seal et al., 2011).

The relative success of this study indicates that a single PNF session intervention can lead to meaningful reductions in problem drinking despite its brevity. In addition, the ability to deliver the intervention via the Internet greatly increases the reach of the intervention. In particular, our study demonstrated that it is possible to reach veterans who are unlikely to seek conventional treatment. For example, about 80% of participants had not sought alcohol or other substance use treatment since discharge and nearly one-third of the sample had never been to a VHA clinic. Despite low treatment seeking, a substantial portion of the sample had screening scores consistent with hazardous drinking. Although we used a lower threshold for purposes of inclusion, mean AUDIT scores across groups were 12 and 13 for the intervention and control groups, respectively. These values are well above the criterion of 8 for hazardous drinking and 29% percent of the sample screened positive for problem drinking with AUDIT scores of 16 or higher (Babor et al., 2001; Saunders et al., 1993). Moreover, nearly half and over one-third of participants screened positive for probable depression and PTSD, respectively. Thus, in addition to heavy drinking, this sample could be characterized as experiencing significant symptoms of two comorbid mental health problems (i.e., depression and PTSD).

Most prior research has demonstrated that PNF is efficacious when delivered in-person to veterans and service members either individually with a facilitator (Martens et al., 2015) or over computers within VHA clinics (Cucciare et al., 2013). Yet, we recruited outside of VHA clinics using the popular Internet website Facebook to greatly expand the reach of an evidence-based care approach to young veterans typically resistance to seek care, and thus by definition, are difficult to locate for intervention delivery. Thus, this mode of administration appears to have great potential as a means of delivering intervention to those in need.

In addition to taking PNF out of clinics through the use of the Internet, this study was innovative in other respects. For example, other interventions incorporating normative peer drinking comparisons are based on civilian norms that veterans are not influenced by (Neighbors et al., 2014; Pedersen et al., 2016b), norms from VHA samples that represent service-seeking VHA clinic users only, or data on active duty service members that may be marked by underreporting due to confidentiality concerns or may no longer be relevant to those separated from the military. The PNF in the present study incorporated gender-specific veteran norms from peers in the community (both VHA and non-VHA veterans) that are highly correlated with actual veteran drinking behavior (Pedersen et al., 2016b). A large body of literature among young adults has demonstrated stronger influences on actual drinking behavior from perceived drinking norms of similar others than more distal others (e.g., perceptions of “other gender-specific students from one’s college” are more strongly associated with college students’ drinking than perceptions of “other college students”) (Larimer et al., 2009; Latané, 1981; Lewis & Neighbors, 2006; Neighbors et al., 2010; Neighbors et al., 2008; Reed, Lange, Ketchie, & Clapp, 2007). Our findings indicate that even for veterans far removed from military service and perhaps fully absorbed into civilian life, veteran drinking norms can still be impactful when displayed in PNF interventions.

Limitations

The one-month follow-up assessment addresses the short-term impact of the intervention. However, additional research is needed to determine the maintenance of treatment effects over a longer time period. Additional follow-up points are also needed to more fully test the temporal ordering that would capture a mediated process (Nock, 2007). It is possible that changes in drinking that occurred following the PNF intervention may have influenced the observed changes in norms. Secondly, although we were adequately powered (80% power) to detect a gender effect of medium size, we had relatively few female participants, which limited our ability to detect smaller effects. Future work with larger samples of women is needed to examine whether intervention effects vary as a function of gender. In addition, although use of the Internet constitutes a strength of the study, it also is a shortcoming in the sense that this method of recruitment excludes those without Internet access (e.g., the indigent or homeless). Fortunately, the vast majority of young adult veterans have access to the Internet (Sadler et al., 2013; Sayer et al., 2010). We advertised to family members to reach veterans potentially not on Facebook (10% of our sample learned about the study from a friend or relative). Also, although participants reported symptoms of PTSD and depression, the intervention was not intended to target those with severe mental illness (e.g., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia), which makes up a much smaller proportion of OEF/OIF veterans (Hawkins et al., 2010), but for whom more intensive efforts may be needed (Fortney & Owen, 2014). Lastly, data were based on self-report, which is a concern of all alcohol intervention studies that do not collect objective measures or collateral reports of participants’ alcohol use. Due to confidentiality of reported behavior and the use of the Internet recruitment procedures, verification of self-report was not feasible.

Conclusions

The public health implications of this approach are quite promising. We have developed an inexpensive, single-session, web-delivered intervention, that is intended as a stand-alone treatment. The intervention appears to reduce problem drinking among young veterans. It also appears that the recruitment and delivery method is well-suited to attracting hazardous drinkers who are not specifically searching for care. Similarly, use of the Internet may facilitate use by persons who have limited access to providers or those who may be resistant to conventional treatment approaches. The intervention requires little or no contact with clinicians, no visits to a local VHA, and does not rely on traditional recruitment methods targeting those already seeking some form of care (e.g., flyers seen by patients already enrolled in a primary care clinic at a VHA). This intervention could reach thousands of veterans in just a few months’ time, for a fraction of the cost required to provide in-person multi-session treatment. Future work is needed to evaluate the long-term efficacy of the approach.

Public Health Significance.

The observed reductions in drinking and consequences among PNF participants indicates that the PNF approach is feasible and appropriate for young adult veterans not specifically searching for alcohol treatment. The program is sustained entirely on the Internet, uses limited time and personnel resources, and can be available anytime to veterans for personal use; even on mobile phones or tablets with Internet access.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R34 AA022400, “Brief Online Intervention to Reduce Heavy Alcohol Use among Young Adult Veterans”) awarded to Eric R. Pedersen. The authors wish to thank the RAND MMIC team for survey and intervention hosting and Michael Woodward for assistance with survey and intervention design.

References

- Aron A, Aron EN, Smollan D. Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63(4):596–612. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. 2nd. World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Stacy A, Larimer M. Biases in the perception of drinking norms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52(6):580–586. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz AD, Perkins HW. Problem drinking among college students: a review of recent research. Journal of American College Health. 1986;35(1):21–28. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1986.9938960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: a meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64(3):331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley K, Bush KR, Epler AJ, Dobie DJ, Davis TM, et al. Two brief alcohol-screening tests from the alcohol use disorders identification test (audit): Validation in a female veterans affairs patient population. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003;163(7):821–829. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KA, Bush KR, McDonell MB, Malone T, Fihn SD, et al. Screening for problem drinking - Comparison of CAGE and AUDIT. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1998;13(6):379–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brick JM, Kalton G. Handling missing data in survey research. Statistical methods in Medical Research. 1996;5(3):215–238. doi: 10.1177/096228029600500302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brief DJ, Rubin A, Enggasser JL, Roy M, Keane TM. Web-based intervention for returning veterans with symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder and risky alcohol use. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 2011;41(4):237–246. doi: 10.1007/s10879-011-9173-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brief DJ, Rubin A, Keane TM, Enggasser JL, Roy M, et al. Web intervention for OEF/OIF veterans with problem drinking and PTSD symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81(5):890–900. doi: 10.1037/a0033697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett-Zeigler I, Ilgen M, Valenstein M, Zivin K, Gorman L, et al. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol misuse among returning Afghanistan and Iraq veterans. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(8):801–806. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun PS, Elter JR, Jones ER, Jr, Kudler H, Straits-Troster K. Hazardous alcohol use and receipt of risk-reduction counseling among U.S. veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69(11):1686–1693. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Henson JM, Carey MP, Maisto SA. Perceived norms mediate effects of a brief motivational intervention for sanctioned college drinkers. Clinical Psychology. 2010;17(1):58–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey MP, DeMartini KS. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: a meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KK, Neighbors C, Gilson M, Larimer ME, Marlatt GA. Epidemiological trends in drinking by age and gender: Providing normative feedback to adults. Addictive behaviors. 2007;32(5):967–976. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(1):155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: the effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53(2):189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office. Quality Initiatives Undertaken by the Veterans Health Administration. Washington, DC: 2009. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Cronce JM, Larimer ME. Individual-focused approaches to the prevention of college student drinking. Alcohol Research and Health. 2011;34(2):210–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucciare MA, Weingardt KR, Ghaus S, Boden MT, Frayne SM. A randomized controlled trial of a web-delivered brief alcohol intervention in Veterans Affairs primary care. Journal of Studies on Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74(3):428–436. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durham Veterans Affairs Healthcare System, Evidence-Based Synthesis Program (ESP) Center. E-Interventions for Alcohol Misuse. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0076665/pdf/PubMedHealth_PMH0076665.pdf.

- Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Health Administration; Office of RuralHealth Strategic Plan 2010–2014. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/docs/ORH_GeneralFactSheet_April2012.pdf. Retrieved from.

- DeViva JC, Sheerin CM, Southwick SM, Roy AM, Pietrzak RH, Harpaz-Rotem I. Correlates of VA mental health treatment utilization among OEF/OIF/OND veterans: Resilience, stigma, social support, personality, and beliefs about treatment. Psychological Trauma. 2015;8:310–318. doi: 10.1037/tra0000075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotson KB, Dunn ME, Bowers CA. Stand-alone Personalized Normative Feedback for college student drinkers: A meta-analytic review, 2004 to 2014. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(10):e0139518. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumas DM, Hannah E. Preventing high-risk drinking in youth in the workplace: a web-based normative feedback program. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;34(3):263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani R. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Erbes C, Westermeyer J, Engdahl B, Johnsen E. Post-traumatic stress disorder and service utilization in a sample of service members from Iraq and Afghanistan. Military Medicine. 2007;172(4):359–363. doi: 10.7205/milmed.172.4.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortney JC, Owen RR. Increasing treatment engagement for persons with serious mental illness using personal health records. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;171(3):259–261. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13121701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AB, Meyer EC, Vogt D. Attitudes about the VA health-care setting, mental illness, and mental health treatment and their relationship with VA mental health service use among female and male OEF/OIF veterans. Psychological Services. 2015;12(1):49–58. doi: 10.1037/a0038269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia HA, Finley EP, Ketchum N, Jakupcak M, Dassori A, Reyes SC. A survey of perceived barriers and attitudes toward mental health care among OEF/OIF veterans at VA outpatient mental health clinics. Military Medicine. 2014;179(3):273–278. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Vazan P, Bennett AS, Liberty HJ. Unmet need for treatment of substance use disorders and serious psychological distress among veterans: A nationwide analysis using the NSDUH. Military Medicine. 2013;178(1):107–114. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-12-00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins EJ, Lapham GT, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Recognition and management of alcohol misuse in OEF/OIF and other veterans in the VA: a cross-sectional study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;109(1–3):147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester RK, Squires DD, Delaney HD. The Drinker’s Check-up: 12-month outcomes of a controlled clinical trial of a stand-alone software program for problem drinkers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28(2):159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351(1):13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Hustad J, Barnett NP, Strong DR, Borsari B. Validation of the 30-day version of the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire for use in longitudinal studies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(4):611–615. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: the brief young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29(7):1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171940.95813.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer J, Rubin A, Coster W, Helmuth E, Hermos J, et al. Strategies to address participant misrepresentation for eligibility in Web-based research. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Reseach. 2014;23(1):120–129. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, et al. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;114(1–3):163–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Kaysen DL, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Lewis MA, et al. Evaluating level of specificity of normative referents in relation to personal drinking behavior. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009:115–121. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latané B. The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist. 1981;36(4):343–356. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Social norms approaches using descriptive drinking norms education: a review of the research on personalized normative feedback. Journal of American College Health. 2006;54(4):213–218. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.4.213-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Cadigan JM, Rogers RE, Osborn ZH. Personalized drinking feedback intervention for veterans of the wars in iraq and afghanistan: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2015;76(3):355–359. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashek D, Cannaday LW, Tangney JP. Inclusion of Community in Self Scale: A Single-Item Pictorial Measure of Community Connectedness. Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;35(2):257–275. [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey DF, Ridgeway G, Morral AR. Propensity score estimation with boosted regression for evaluating causal effects in observational studies. Psychological Methods. 2004;9:403. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt-Murphy ME, Murphy JG, Williams JL, Monahan CJ, Bracken-Minor KL, Fields JA. Randomized controlled trial of two brief alcohol interventions for OEF/OIF veterans. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(4):562–568. doi: 10.1037/a0036714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt-Murphy ME, Williams JL, Bracken KL, Fields JA, Monahan CJ, Murphy JG. PTSD symptoms, hazardous drinking, and health functioning among U.S.OEF and OIF veterans presenting to primary care. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23(1):108–111. doi: 10.1002/jts.20482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DT, Prentice DA. Changing norms to change behavior. Annual Review of Psychology. 2016;67(1):339–361. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, Brett EI, Leavens EL, Meier E, Borsari B, Leffingwell TR. Informing alcohol interventions for student service members/veterans: Normative perceptions and coping strategies. Addictive Behaviors. 2016;57:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, Leffingwell T, Claborn K, Meier E, Walters ST, Neighbors C. Personalized feedback interventions for college alcohol misuse: An update of Walters & Neighbors (2005) Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:909–920. doi: 10.1037/a0031174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Desai S, Larimer ME. Group identification as a moderator of the relationship between perceived social norms and alcohol consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(3):522–528. doi: 10.1037/a0019944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Lewis MA, Lee CM, et al. Group identification as a moderator of the relationship between perceived social norms and alcohol consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(3):522–8. doi: 10.1037/a0019944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, O’Connor RM, Lewis MA, Chawla N, Lee CM, Fossos N. The relative impact of injunctive norms on college student drinking: The role of reference group. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:576–581. doi: 10.1037/a0013043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Walker D, Rodriguez L, Walton T, Mbilinyi L, Kaysen D, Roffman R. Normative misperceptions of alcohol use among substance abusing Army personnel. Military Behavioral Health. 2014;2(2):203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK. Conceptual and design essentials for evaluating mechanisms of clinical change. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:4S–12S. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, Helmuth ED, Marshall GN, Schell TL, PunKay M, Kurz J. Using facebook to recruit young adult veterans: online mental health research. JMIR Research Protocols. 2015;4(2):e63. doi: 10.2196/resprot.3996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, Marshall GN, Schell TL. Study protocol for a web-based personalized normative feedback alcohol intervention for young adult veterans. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2016a;11(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s13722-016-0055-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, Marshall GN, Schell TL, Neighbors C. Young adult veteran perceptions of peers’ drinking behavior and attitudes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2016b;30:39–51. doi: 10.1037/adb0000120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, Naranjo D, Marshall GN. Recruitment and retention of young adult veteran drinkers using Facebook. PLOS One. 2016c doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172972. Reference is still in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton MR, Williams J, Herman-Stahl M, Calvin SL, Bradshaw MR, et al. Evaluation of two web-based alcohol interventions in the U.S. military. Journal of Studies on Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72(3):480–489. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Johnson DC, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Southwick SM. Perceived stigma and barriers to mental health care utilization among OEF-OIF veterans. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(8):1118–1122. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.8.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramchand R, Miles J, Schell T, Jaycox L, Marshall GN, Tanielian T. Prevalence and correlates of drinking behaviors among previously deployed military and matched civilian populations. Military Psychology. 2011;23(1):6–21. doi: 10.1080/08995605.2011.534407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MB, Lange JE, Ketchie JM, Clapp JD. The relationship between social identity, normative information, and college student drinking. Social Influence. 2007;2(4):269–294. [Google Scholar]

- Reid AE, Carey KB. Interventions to reduce college student drinking: State of the evidence for mechanisms of behavior change. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015;40:213–224. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway G, McCaffrey D, Morral A, Burgette L, Griffin BA. Toolkit for Weighting and Analysis of Nonequivalent Groups: A tutorial for the twang package. R vignette RAND 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Riper H, van Straten A, Keuken M, Smit F, Schippers G, Cuijpers P. Curbing problem drinking with personalized-feedback interventions: a meta-analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;36(3):247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler AG, Mengeling MA, Torner JC, Smith JL, Franciscus CL, Erschens HJ, Booth BM. Feasibility and Desirability of Web-Based Mental Health Screening and Individualized Education for Female OEF/OIF reserve and national guard war veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2013;26(3):401–404. doi: 10.1002/jts.21811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption–II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer NA, Noorbaloochi S, Frazier P, Carlson K, Gravely A, Murdoch M. Reintegration problems and treatment interests among Iraq and Afghanistan combat veterans receiving VA medical care. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61(6):589–597. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.6.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell TL, Marshall GN. Survey of individuals previously deployed for OEF/OIF. In: Tanielian T, Jaycox LH, editors. Invisible wounds of war: Psychological and cognitive Injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation MG-720; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Seal KH, Cohen G, Waldrop A, Cohen BE, Maguen S, Ren L. Substance use disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in VA healthcare, 2001–2010: Implications for screening, diagnosis and treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;116:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman SR, White IR. Review of inverse probability weighting for dealing with missing data. Statistical Methods in MedicalRresearch. 2013;22(3):278–295. doi: 10.1177/0962280210395740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(4):422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahre MA, Brewer RD, Fonseca VP, Naimi TS. Binge drinking among U.S. active-duty military personnel. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;36(3):208–17. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner-Smith EE, Lipsey MW. Brief alcohol interventions for adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2015;51:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropp LR, Wright SC. Ingroup Identification as the Inclusion of Ingroup in the Self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27(5):585–600. [Google Scholar]

- Vandecasteele L, Debels A. Attrition in panel data: the effectiveness of weighting. European Sociological Review. 2007;23(1):81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt D. Mental health-related beliefs as a barrier to service use for military personnel and veterans: a review. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62(2):135–142. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.2.pss6202_0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DD, Walton T, Neighbors C, Kaysen D, Mbilinyi L, Roffman RA. Attracting substance abusing soldiers to voluntarily take stock of their use: Preliminary outcomes from The Warrior Check-Up MET intervention. Paper presented at the Addiction Health Services Research Conference; Marina del Rey, CA. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Neighbors C. Feedback interventions for college alcohol misuse: what, why and for whom? Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30(6):1168–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins KE, Pincus HA, Smith B, Paddock SM, Mannle TE, et al. Veterans Health Administration Mental Health Program Evaluation: Capstone Report. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation TR956; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, Schnurr PP. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) Boston, MA: National Center for PTSD; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- White HR. Reduction of alcohol-related harm on United States college campuses: The use of personal feedback interventions. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17(4):310–319. [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Herman-Stahl M, Calvin SL, Pemberton M, Bradshaw M. Mediating mechanisms of a military Web-based alcohol intervention. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;100(3):248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Capone C, Laforge R, Erickson DJ, Brand NH. Brief motivational intervention and alcohol expectancy challenge with heavy drinking college students: a randomized factorial study. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2509–2528. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wortmann JH, Jordan AH, Weathers FW, Resick PA, Dondanville KA, et al. Psychometric analysis of the PTSD Checklist-5 (PCL-5) among treatment-seeking military service members. Psychological Assessment. 2016;28(11):1392–1403. doi: 10.1037/pas0000260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]