Abstract

Objective

This randomized clinical trial compared Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) treatment alone, intensive reading intervention alone, and their combination for children with ADHD and word reading difficulties and disabilities (RD).

Method

Children (n=216; predominantly African American males) in grades 2–5 with ADHD and word reading/decoding deficits were randomized to ADHD treatment (carefully-managed medication+parent training), reading treatment (intensive reading instruction), or combined ADHD+reading treatment. Outcomes were parent and teacher ADHD ratings and measures of word reading/decoding. Analyses utilized a mixed models covariate-adjusted gain score approach with post-test regressed onto pretest and other predictors.

Results

Inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity outcomes were significantly better in the ADHD (parent Hedges g=.87/.75; teacher g=.67/.50) and combined (parent g=1.06/.95; teacher g=.36/41) treatment groups than reading treatment alone; the ADHD and Combined groups did not differ significantly (parent g=.19/.20; teacher g=.31/.09). Word reading and decoding outcomes were significantly better in the reading (word reading g=.23; decoding g=.39) and combined (word reading g=.32; decoding g=.39) treatment groups than ADHD treatment alone; reading and combined groups did not differ (word reading g=.09; decoding g=.00). Significant group differences were maintained at the three- to five-month follow-up on all outcomes except word reading.

Conclusions

Children with ADHD and RD benefit from specific treatment of each disorder. ADHD treatment is associated with more improvement in ADHD symptoms than RD treatment, and reading instruction is associated with better word reading and decoding outcomes than ADHD treatment. The additive value of combining treatments was not significant within disorder, but the combination allows treating both disorders simultaneously.

Keywords: reading disability, reading intervention, decoding, multimodal treatment, ADHD

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and word-reading difficulties and disabilities (RD) are prevalent childhood disorders that frequently co-occur. Comorbidity between RD and ADHD typically ranges from 25 to 40% (Faraone, Biederman, Weber, & Russell, 1998; Willcutt, Pennington, Olson, Chhabildas, & Hulslander, 2005). Children with comorbid ADHD/RD differ from those with only one of these disorders. For example, they exhibit more severe weaknesses in executive functioning tasks, greater academic impairment, and more pervasive and severe negative social and occupational outcomes than children with either disorder alone (Purvis & Tannock, 2000; Rucklidge & Tannock, 2002; Seidman, Biederman, Monuteaux, Doyle, & Faraone, 2001; Willcutt et al., 2010; Willcutt, Doyle, Nigg, Faraone, & Pennington, 2005). Further, comorbid ADHD/RD is associated with more severe reading problems (Lyon, 1996) and lower grades than RD alone (McNamara, Willoughby, Chalmers, & YLC-CURA, 2005), and more severe attention problems than ADHD alone (Mayes & Calhoun, 2007).

Evidence-based treatments exist for both ADHD and RD. Both pharmacological (Sibley, Kuriyan, Evans, Waxmonsky, & Smith, 2014) and behavioral (Evans, Owens, & Bunford, 2014) interventions are efficacious for improving ADHD symptoms and some ADHD-related impairment. Current guidelines recommend combining these interventions for school-aged children with ADHD (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2007). Children with dyslexia and those with less severe word reading difficulties benefit from intensive, systematic instruction in phonics and word identification, along with practice reading connected text (National Reading Panel, 2000). Consistent with challenges and changes over time in the identification of learning disabilities (Fletcher et al., 2011), the characterization of RD varies across studies; however, empirical evidence supports the same intervention approach for children with identified reading disabilities and those with less severe word-reading difficulties [see (Fletcher, Lyon, Fuchs, & Barnes, 2007) for a review].

While the evidence for these intervention strategies for either of these disorders is clear, the most appropriate intervention strategy for children who have comorbid ADHD/RD is unclear. For example, if ADHD is targeted, might the attention improvements result in improved reading performance? If RD is targeted, might better reading performance result in improved attention and/or behavior? Or do children with ADHD and RD require simultaneous treatment targeting both disorders? Moreover, is there an additive effect of treating the two conditions simultaneously? With regards to the latter, it may be that treatment of ADHD symptoms and treatment of reading difficulties simultaneously may result in incremental benefit in terms of ADHD symptom reduction and higher reading scores than the benefits of either of these interventions implemented in isolation. These questions have clear clinical and educational implications; however, existing empirical evidence addressing them is sparse.

There is some evidence that providing RD treatment can impact inattention. For example, first-grade children provided with computer-assisted reading instruction targeting phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension, had greater reduction of teacher-rated inattentive symptoms and better oral text reading fluency outcomes relative to controls (Rabiner, Murray, Skinner, & Malone, 2010). Another study, conducted with middle school students with severe reading difficulties showed that a response-to-intervention reading intervention including direct instruction in word reading, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension delivered over a three-year period improved both reading achievement and teacher-rated inattention (Roberts et al., 2015). However, participants in these studies did not meet DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ADHD. It is not known whether similar effects of disorder-specific RD treatment would be observed for children who have both ADHD and RD.

It has also been observed that inattention contributes to reading problems and their intractability (Jacobson, Ryan, Denckla, Mostofsky, & Mahone, 2013; Jacobson et al., 2011; Nelson, Benner, & Gonzalez, 2003), leading to the hypothesis that disorder-specific treatment of ADHD symptoms will positively impact reading outcomes. This hypothesis has been supported by studies indicating that treatment with ADHD medications (including stimulants and non-stimulants) is associated with improved word reading outcomes in children ages 6 to 16 with ADHD/RD (Bental & Tirosh, 2008; Keulers et al., 2007; Shaywitz, Williams, Fox, & Wietecha, 2014; Sumner et al., 2009; Williamson, Murray, Damaraju, Ascher, & Starr, 2014). However, there is also evidence that ADHD medications do not improve phonological processes key to reading development in children ages 5 to 11 (Balthazor, Wagner, & Pelham, 1991; Bental & Tirosh, 2008); thus, medication treatments may not have lasting effects on RD. Children in these studies met DSM criteria for ADHD, but the definition of RD varied. Some defined RD on the basis of low reading achievement (Bental & Tirosh, 2008; Williamson et al., 2014), while others based identification on a discrepancy between IQ and reading achievement scores (Shaywitz et al., 2014; Sumner et al., 2009) or a combination of DSM-IV criteria for Reading Disorder and inadequate response to intensive reading intervention (Keulers et al., 2007). Participants in these studies received only medication treatment without reading treatment so the studies do not provide a test of the additive value of ADHD treatment over reading treatment alone for reading outcomes.

Unimodal treatments may be insufficient for children with comorbid ADHD/RD. It has been reported that children ages 6–12 with comorbid learning disabilities do not show as much improvement on ADHD symptoms in response to stimulant medication as those with ADHD only (Grizenko, Bhat, Schwartz, Ter-Stepanian, & Joober, 2006). Similarly, higher levels of attentional problems moderated the beneficial effects of phonics-based reading tutoring for kindergarten to first grade children with reading difficulties, such that children with low attention problem scores benefited more from reading intervention than those with higher attention problem scores (Rabiner, Malone, & Conduct Problems Prevention Research, 2004). Thus, the presence of a comorbid disorder may impact the effectiveness of unimodal interventions, implicating a need for a multimodal intervention strategy that addresses ADHD and RD simultaneously.

Only one published study has investigated the relative benefits of a combined ADHD and reading intervention strategy for ADHD/RD (Richardson, Kupietz, Winsberg, Maitinsky, & Mendell, 1988). In a sample of 45 children ages 7- to 13-years with RD (based on low growth on selected reading subtests of the Decoding Skills Test and Peabody Individual Achievement Test) and comorbid hyperactivity, Richardson et al. (1988) assessed the impact of providing methylphenidate (MPH) at various doses or placebo along with 24 weeks of reading intervention (word-reading instruction with application in connected text). Results of this study were inconclusive. There was a significant effect of medication dosage on word reading, which appeared to be associated with better results for the highest dosage group. However, although MPH was positively associated with reading gains during the first half of the study, it was associated with declining reading scores during the second half of the study. This study had limitations that reduce its generalizability. For example, the reading intervention was provided by trained interventionists only once per week, relying heavily on parent practice for the remainder of the week, for which fidelity was not reported. In addition, all study assessments were conducted while children were on placebo, possibly attenuating any beneficial effects of MPH for those assigned to the medication group.

Purpose of the Study and Research Questions

The purpose of this study was to comprehensively address questions regarding appropriate intervention strategies for children with comorbid ADHD/RD. Our primary research questions were: (a) what are the relative impacts of disorder-specific ADHD treatment (i.e., carefully monitored medication and behavioral parent training) or reading treatment (i.e. systematic, phonologically-based reading instruction) on word reading/decoding outcomes and ADHD symptoms among children with comorbid ADHD/RD?, and (b) what is the incremental benefit of providing a combined ADHD and reading intervention compared to either of these disorder-specific interventions alone? We hypothesized that attentional outcomes would be significantly better in students who received ADHD treatment compared to students who received only reading treatment. We similarly hypothesized that reading outcomes would be significantly higher in students who received reading treatment compared to students who received only ADHD treatment. We hypothesized that children who received the combined treatment would achieve significantly higher attentional and word reading outcomes than children who received either disorder-specific treatment.

METHODS

Context

This study took place at two sites. One was in the Houston metropolitan area, where participants attended one of 17 schools, including 9 public schools in 2 school districts and 8 charter or parochial schools. The other site was in the greater Cincinnati area, where children attended one of 46 schools in 20 districts and 8 private or charter schools. The study was replicated with seven cohorts of children over five years to build the required sample size.

Participants

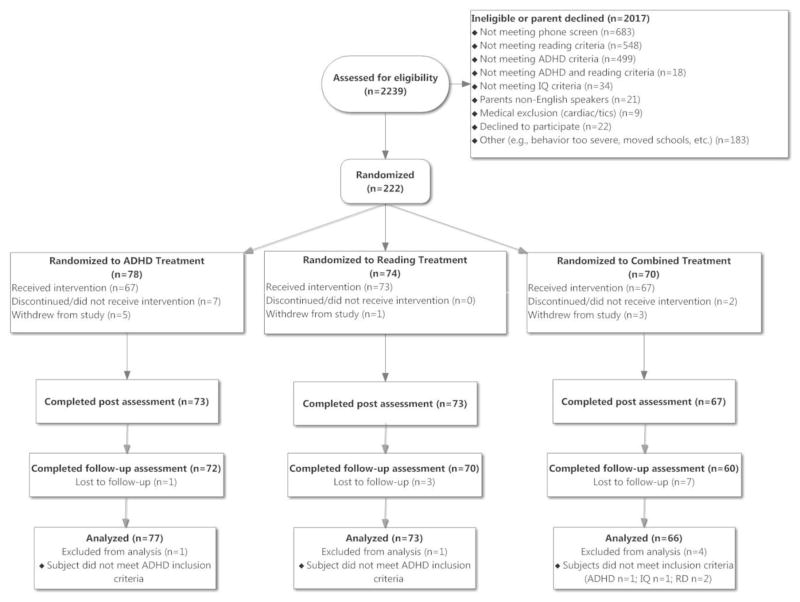

Children in grades 2 to 5 were primarily recruited in schools, but also from outpatient clinics and the community. Figure 1 illustrates the process of recruitment, randomization, treatment, assessment, and analysis. The group of children assessed for eligibility includes all children who were initially identified by their teachers or parents as having both reading and attention problems. Parents and teachers completed the Swanson Nolan and Pelham [SNAP-IV; (Swanson, 1992)] inattention items. Parents of children who were currently taking medication for ADHD were asked to rate their children’s attention on medication; to qualify for further evaluation, children had to be rated as having some (≥4) inattentive symptoms even when taking medications. Children who met criteria on the SNAP-IV were administered the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition (Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004) and Woodcock-Johnson III [WJ-III; (Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001)] Letter-Word Identification and Word Attack subtests. Children were considered to have word-level reading difficulties or disabilities if they had a standard score of ≤90 (i.e., ≤25th percentile) on either WJ-III subtest or the Basic Reading Skills composite. This is a common benchmark for inadequate treatment response in reading intervention research, e.g., (C. A. Denton et al., 2013; Torgesen, 2000; Torgesen et al., 2001; Vellutino, Scanlon, Small, & Fanuele, 2006) and indicates that children are likely to require intensive reading intervention to prevent or remediate serious reading difficulties or disabilities (C. A. Denton et al., 2013; Fletcher et al., 2011; Fuchs, Fuchs, & Compton, 2004). For example, Fuchs et al. (Fuchs et al., 2004) reported that post-intervention word-reading performance the ≤ 25th percentile discriminated between children with severe and less severe reading impairment, with effect sizes greater than 1 SD. Additionally, the ability to decode and read individual words during this developmental period has been shown to be related to future high school performance and drop-out rates (The Annie E. Casey Foundation & Hernandez, 2011) and is a fundamental skill for other reading abilities such as reading comprehension (Perfetti, Landi, & Oakhill, 2005). We excluded children with Full Scale and Nonverbal IQ estimates <70; we used a lower IQ threshold for inclusion as IQ scores do not differentiate cognitive characteristics or intervention response among poor readers who have IQ scores above the threshold for intellectual disability [reviewed in (Fletcher et al., 2007)].

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram

Parents of children who qualified on all measures were administered the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, 4.0 [DISC; (Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000)], and children were examined by a study physician. Children met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ADHD (Combined or Inattentive type) based on the DISC. If a child did not meet diagnostic criteria on the DISC, we supplemented the DISC symptom ratings with teacher ADHD ratings (MTA Cooperative Group, 1999a), if a child was rated by the teacher as “quite a bit” or “very much” on ADHD symptoms that did not overlap with those identified by the DISC, those symptoms were counted in the eligibility determination. Exclusionary criteria were cardiovascular problems; chronic tics; taking a concomitant medication with potential to significantly affect ADHD that would be contraindicated to take with the study medication; severe psychopathology, autism, or sensory disabilities; or not receiving instruction in English.

Table 1 shows demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample. Children were predominantly male, African American, and economically disadvantaged. Informed parental consent and child assent were obtained for all participants.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Sample

| Reading Treatment (n=73) | ADHD Treatment (n=77) | Combined Treatment (n=66) | Group Differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 8.8 ± 1.3 | 8.9 ± 1.4 | 8.8 ± 1.2 | F (2,215) = .27, n.s. |

| Percent Male | 67.1% | 67.5% | 47% | χ2 (2) = 8.0* |

| Percent Hispanic | 7.8% | 10.5% | 18.3% | χ2 (2) = 3.50, n.s. |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 17.8% | 18.2% | 22.7% | χ2 (6) = 6.3, n.s. |

| African American | 76.7% | 71.4% | 68.2% | |

| Biracial | 5.5% | 9.1% | 4.5% | |

| Other | 0% | 1.3% | 4.5% | |

| Grade | ||||

| 2nd grade | 30.6% | 28.9% | 30.8% | χ2 (6) = 0.4, n.s. |

| 3rd grade | 26.4% | 25.0% | 24.6% | |

| 4th grade | 25.0% | 25.0% | 23.1% | |

| 5th grade | 18.1% | 21.1% | 21.5% | |

| Economically Disadvantaged | 77.7% | 77.9% | 72.7% | χ2 (4) = 1.78, n.s. |

| ADHD Combined Type | 58.3% | 57.9% | 45.5% | χ2 (2) = 2.9, n.s. |

| Comorbid ODD | 26.4% | 36.8% | 36.9% | χ2 (2) = 2.4, n.s. |

| Comorbid Conduct Disorder | 11.3% | 14.5% | 7.7% | χ2 (2) = 1.6, n.s. |

| Comorbid Anxiety Disorder | 31.0% | 28.9% | 36.9% | χ2 (2) = 1.1, n.s. |

| Comorbid Mood Disorder | 4.3% | 7.9% | 4.7% | χ2 (2) = 1.0, n.s. |

| Served by Special Education | 35.6% | 35.1% | 42.4% | χ2 (2) = 1.0, n.s. |

| Full Scale IQ | 86.2 ± 12.1 | 86.8 ± 11.8 | 86.7 ± 11.7 | F (2,215) = .05, n.s. |

| Reading Treatment Attendance a | 55.6 ± 10.5 | n/a | 54.6 ± 14.4 | F (1,138) = .21, n.s. |

| Parent Training Attendancea | n/a | 4.8 ± 3.2 | 5.2 ± 3.3 | F (1,139) = .64, n.s. |

| Medication Adherence proxy b | n/a | .74 (.35) | .80 (.32) | F (1,142) = 1.1, n.s |

Note: Economically disadvantaged = receives free or reduced lunch; ODD = Oppositional Defiant Disorder; Hyp/Imp=Hyperactivity/Impulsivity.

Number of sessions attended;

Number of days prescribed medication divided by total days in study

p < .05,

p < .01

Measures

Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham (SNAP-IV) DSM-IV ADHD Rating Scale (Swanson, 1992)

Raters evaluate how well each DSM-IV ADHD symptom describes a child on a four-point Likert scale (0=Not at all, 1=Just a little, 2=Quite a bit, 3=Very much). The measure shows adequate internal consistency (.94) and test-retest reliability (Bussing et al., 2008; Gau et al., 2008). Primary ADHD outcome measures were averages of the inattention and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms for parent and teacher ratings completed at pre, post, and follow-up.

Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, 3rd Edition (WIAT) (Wechsler, 2009)

The WIAT Word Reading and Pseudoword Decoding standard scores obtained at pre, post, and follow-up were the reading outcome measures for the study. Split-half reliability for these two subtests for 2nd through 5th graders are ≥.96 and test-retest reliability ≥.93. Validity studies show that these subtests are sensitive to detecting Reading Disorders and have good construct validity with other sight word and non-word reading tests (Breaux, 2010).

Design and Procedures

Families were initially screened for eligibility using the procedures previously described. Children taking psychostimulants at the time of enrollment did not take those medications during the baseline assessment. Eligible children were then randomized, stratified by grade, to: (a) reading treatment only, (b) ADHD treatment only, or (c) combined reading and ADHD treatment. Participants received 16 weeks of treatment, at no cost, and participated in a post-test evaluation and a follow-up evaluation three to five1 months post-treatment. Children in the ADHD and combined treatment groups completed the post-test while on study medications.

Participants were administered behavioral and academic measures, as well as measures of service utilization and related domains at each assessment. In this paper, we report the primary study outcomes: ADHD symptoms, word reading, and phonemic decoding. We were particularly interested in examining intervention effects on inattentive symptoms since inattention, rather than hyperactivity, is primarily related to reading difficulties (Massetti et al., 2008; Willcutt & Pennington, 2000); however, we also examined hyperactivity/impulsivity since a reduction in these symptoms could also improve response to reading intervention. We examined word reading and phonemic decoding as primary reading outcomes because word-reading disability is the most common reading disability (Fletcher, 2009; Vellutino, Fletcher, Snowling, & Scanlon, 2004) and was the required area of reading impairment for inclusion in this study.

Reading treatment

Reading treatment targeted phonics, word identification, spelling, reading fluency, and comprehension. All children received word study instruction and read connected text in every lesson; the proportion of lesson time devoted to word study, fluency, and comprehension was adjusted to address the needs of individual students. Children were provided with explicit, systematic instruction in word reading, decoding, and spelling using published programs (Vadasy & Sanders, 2007; Vadasy et al., 2005), supplemented with a set of hands-on practice activities that included the use of manipulatives (e.g., magnetic letters). Students read both decodable and non-decodable text. To build oral reading fluency, students engaged in repeated reading practice of nonfiction texts with monitoring and feedback (Chard, Vaughn, & Tyler, 2002) using QuickReads (Hiebert, 2003). Each fluency passage was accompanied by comprehension activities, including instructional routines in cognitive and meta-cognitive comprehension strategies (e.g., self-monitoring, summarizing). More information regarding the reading intervention can be found in the supplemental materials.

Reading intervention was provided to one or two students at a time for 45 minutes, four days per week for 16 weeks. Interventionists, most of whom were certified teachers (87%), attended a four-day initial training provided by the principal investigator (PI) and reading specialists at each site; returning interventionists received two days of training in subsequent years. Interventionists met regularly with the site reading specialists and received ongoing intensive coaching throughout the intervention period. Site reading specialists attended at least monthly teleconferences with the project PI.

At three to four points each year, each interventionist was videotaped and videos were coded for treatment fidelity. Inter-observer reliability was re-established prior to each cohort based on absolute agreement (agreements ÷ agreements + disagreements); mean agreement was 94%±2%. Then, each reading specialist viewed and coded videotaped lessons of interventionists from the other study site. Fidelity was rated using an instrument that reflected key characteristics of each intervention component (e.g., explicit modeling; appropriate error correction). Each item was rated on a three-point Likert scale (3 highest). The score was calculated as a percentage of a perfect score for each lesson, that is, a rating of 3 on all items pertinent to the observed lesson. Across interventionists, sites, and years the mean fidelity rating was 95%±3%. Individual feedback and additional coaching were provided to interventionists scoring below 95%.

ADHD treatment

The ADHD treatment involved parent training in behavior management and ADHD medication. The parent training intervention was adapted from that utilized in the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD (MTA Cooperative Group, 1999b) based on (Barkley, 1987). Training began with psychoeducation about ADHD and basic behavioral principles, followed by information about strategies including positive attention, contingent positive reinforcement, token economies, time out, and daily report cards. Parent training included nine group sessions over 10 weeks. Teachers were provided with written materials regarding establishing a daily report card and offered a one-hour telephone consultation with the psychologist to establish a daily report card. Each group session lasted 1.5 hours. Groups ranged in size from 4 to 13 families. All sessions were conducted by clinical psychologists who attended a two-day training led by the co-PI, who also provided weekly coaching via teleconference. All sessions were audiotaped, and a minimum of two randomly selected sessions per site per cohort were coded for fidelity to the treatment manual (i.e., covered the specified content for each session). The mean fidelity rating was 99%±2.2%.

Treatment with open-label medication typically began with a low dose of an extended release methylphenidate (MPH)2, which was titrated up to either satisfactory benefit or limiting side effects. Weekly Vanderbilt Parent and Teacher ADHD rating scales (Wolraich, Feurer, Hannah, Baumgaertel, & Pinnock, 1998), in addition to the Pittsburgh Side Effects Rating Scale (Pelham, 1993), were obtained from both parents and teachers to monitor response to medication and side effects. If a child did not respond to MPH, treatment with a low dose of mixed amphetamine salts was initiated and titrated up until an optimal dose was achieved. If a child did not respond to either stimulant medication or did not tolerate either stimulant medication due to side effects, a trial with atomoxetine or extended release guanfacine was initiated. Physicians aimed for an optimal response to medication defined as a Clinical Global Impression or CGI (Leon et al., 1993) score of 2 (minimally ill) or 1 (not at all ill). When children reached that rating, treatment was continued at that dose for the remainder of the study period with monthly monitoring visits3. Medication decisions were reviewed on a weekly cross-site conference call led by an expert on pharmacological management for ADHD.

The ultimate medications prescribed to those who received medication were extended release MPH (ADHD=29/59; combined 24/55), mixed amphetamine salts (ADHD=24/59; combined=23/55), atomoxetine (ADHD=2/59; combined=2/55), guanfacine (ADHD=1/59; combined=6/55) or mixed amphetamine salts immediate release (ADHD=1/59). Based on parent preference and significant side effects one participant in the ADHD only group was prescribed an alternative medication at their final visit (1= lisdexamfetamine dimesylate) and one opted to discontinue medication altogether at the end of the study. Details on ultimate dosages can be found in the supplemental materials.

Combined treatment

Children randomly assigned to this condition received both the reading and ADHD treatment components. Thus, children in combined treatment simultaneously received medication, parent training, and reading intervention.

Analytic approach

All analyses were conducted using an intention to treat approach; every subject randomized was considered in the analysis as a member of the treatment group to which s/he was assigned with the exception that six children were excluded from analyses because upon ex post-facto review of records, they did not meet ADHD, RD, or IQ inclusion criteria (see Figure 1). Nine children withdrew during the course of the study, and an additional nine children had both pre and post data but did not receive their assigned interventions. These children, along with others with low adherence to study treatments, were retained in the intent-to-treat analysis, resulting in an analysis sample of 216 children.

One way ANOVAs and chi-square tests were used to compare the three treatment groups on various demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline to investigate whether randomization was effective at producing equality across groups. For the estimation of the treatment effects, we employed a mixed models (MM) covariate-adjusted gain score approach (Petscher & Schatschneider, 2011) via maximum likelihood estimation. Maximum likelihood uses all available data points from each subject in the estimation of parameters and is a preferred method for the handling of missing data in treatment studies (Enders, 2010). In this set of analyses we regressed the post-test or follow-up score onto the pretest score (covariate) and treatment group. The main effect of treatment was interpreted as reflecting an effect of intervention, which was followed up within the same model with a set of three post-hoc contrasts comparing the least-squared mean estimates at post-test or follow-up. The p values from these post-hoc analyses, were corrected for multiple comparisons across all comparisons using False Discovery Rate procedures (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995). The p values reported in the text for the primary analyses investigating immediate and follow-up treatment effects are corrected values. Hedges g was computed as an estimate of effect size (Cohen, 1992). Interactions between baseline scores and treatment condition were inspected first to assess whether the assumption of homogeneity of regression lines was met; in cases where this assumption was violated (i.e., parent ADHD ratings at post-test, teacher hyperactivity/ impulsivity ratings at follow-up), analyses included these interaction terms. We used the same approach for analyses examining potential interactions with gender and site.

To investigate the effects of adhering to the treatment protocol we computed difference scores (post-test minus baseline) for each dependent variable and correlated those scores with the relevant adherence metric (i.e., for reading only, we correlated the change scores with number of reading sessions attended; for ADHD, we correlated the change scores with the number of parent training sessions attended and with the proportion of days the children took medication; for the combined treatment we correlated the change scores with all three adherence variables).

Finally, we conducted exploratory analyses examining the effects of cross-over treatments [i.e., excluding participants receiving medication (n=15) and/or parent training (n=3) in the reading only group, and receiving supplemental reading instruction (n=27) in the ADHD only group].

RESULTS

Preliminary Analyses

The ADHD, reading, and combined treatment groups did not differ on baseline demographic and clinical characteristics with the exception of gender (Table 1); there were fewer boys in the combined treatment group. Significant treatment effects were not observed for gender nor did gender interact significantly with treatment for any variable. Site did not interact with treatment group at either post-test or follow-up on any of the ADHD or reading outcomes. There were also no significant differences on baseline parent or teacher inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity ratings or word reading between the nine students (1 from reading, 5 from ADHD, and 3 from combined) who dropped out from baseline to post-test and the four students (2 from ADHD and 2 from combined) who dropped out from posttest to follow-up (13 total) and the rest of the sample (all p’s > .11). Nor were there any differences between those that dropped out at post-test and those that did not, and those that dropped out at either post-test or follow-up and those that did not (all p’s > .07)

Treatment adherence

Of the 78 children randomized to the ADHD intervention only, 85.9% received some treatment (i.e., started medication and/or attended ≥1 parent training session). Of the 74 assigned to the reading intervention only, 98.6% attended at least one reading tutoring session. For the combined condition, 95.7% of the 70 children assigned to receive both the ADHD and reading interventions received some ADHD or reading treatment. Generally, adherence was poorer for ADHD medication and parent training than for reading treatment, which was delivered at school during the school day (Table 1).

Every effort was made to keep families in the treatment to which they were randomly assigned; however, at post-test 22.5% of the children assigned to the reading treatment reported taking ADHD medication provided by non-study physicians during the intervention period and 4.1% reported receiving parent training, and some children assigned to the ADHD (17.1%) and combined (6.1%) conditions reported no longer taking medications. In addition, some children in each of the three treatment groups received supplemental school-provided reading intervention in addition to their regular classroom reading instruction time. At post-test, according to teacher report, 31.5% of children in the reading, 36.4% in the ADHD group, and 28.8% in the combined treatments received supplemental reading intervention from a special education teacher or reading interventionist at some point during the intervention period; these proportions did not differ between groups [χ2(2)=1.181, p=.554]. At post-test, parents reported that 29.3% of children in the reading, 34.1% of children in the ADHD group, and 36.6% of children in the combined treatments were receiving support from an IEP or 504 plan. Parents who completed surveys at follow-up (~70%) indicated that at that point, 28.6% of children in the reading treatment were taking ADHD medication, while 61.5% in the ADHD treatment and 66% in the combined treatment were taking medication.

Immediate Treatment Effects (Table 2; observed means reported in supplemental materials)

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Treatment Effects at Posttest

| Pretest M (SD)a |

Posttest LSM (SE)b |

Posttest Treatment Effects |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Comb | ADHD | Read | Comb | ADHD | Read | ||

| Parent Inattention | 2.2 (0.5) | 2.1 (0.6) | 2.1 (0.6) | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | F(2,197)=22.6** |

| n=66 | n=77 | n=73 | n=60 | n=71 | n=72 | ADHD=Comb<Read | |

| Parent Hyp/Imp | 1.6 (0.6) | 1.6 (0.9) | 1.7 (0.8) | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 1.3 (0.1) | F(2,197)=22.3** |

| n=66 | n=77 | n=73 | n=60 | n=71 | n=72 | ADHD=Comb<Read | |

| Teacher Inattention | 2.2 (0.6) | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.3 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.1) | 1.2 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | F(2,197)=9.0** |

| n=63 | n=74 | n=72 | n=63 | n=72 | n=71 | ADHD=Comb<Read | |

| Teacher Hyp/Imp | 1.4 (1.0) | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.5 (0.9) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) | F(2,197)=7.7** |

| n=63 | n=74 | n=72 | n=63 | n=72 | n=71 | ADHD=Comb<Read | |

| Word Reading | 73.8 (8.8) | 75.4 (8.5) | 75.2 (9.3) | 79.9 (0.7) | 76.9 (0.7) | 79.0 (0.7) | F(2,203)=5.21** |

| n=66 | n=77 | n=73 | n=63 | n=72 | n=72 | Read=Comb>ADHD | |

| Phonemic Decoding | 73.3 (7.3) | 73.4 (9.7) | 75.1 (9.7) | 83.0 (1.1) | 78.3 (1.0) | 83.8 (1.0) | F(2,203)=9.01** |

| n=66 | n=77 | n=73 | n=63 | n=72 | n=72 | Read=Comb>ADHD | |

Note: Treatment Effects = Effect of treatment controlling for pre-test scores; Comb = combined treatment; Read = reading treatment; ADHD = ADHD treatment; Hyp/Imp = Hyperactivity/Impulsivity.

Pretest observed score means provided to describe initial impairment;

Posttest scores are covariate-adjusted change scores.

p < .05;

p < .01

Parent ADHD ratings

The ADHD (p<.001, Hedges g=.87) and combined (p<.001, g=1.06) treatment groups were rated as significantly less inattentive than the reading treatment group, but did not significantly differ from one another (p=.358, g=.19). Similarly, the ADHD (p<.001, g=.75) and combined (p<.001, g=.95) treatment groups were rated as significantly less hyperactive/impulsive than the reading group, but did not significantly differ from one another (p=.248, g=.20).

Teacher ADHD ratings

The same pattern of results was observed for teacher ratings, such that the ADHD treatment (p<.001, g=.67) and combined treatment (p=.047, g=.36) groups were rated as significantly less inattentive than the reading treatment group, but did not significantly differ from one another (p=.093, g=.31). Teacher ratings of hyperactivity/impulsivity were lower for the ADHD treatment (p<.001, g=.50) and combined treatment (p=.009, g=.41) than the reading treatment group, but did not differ significantly from one another (p=.588, g=.09).

Reading performance

The reading treatment (p=.037, g=.23) and combined treatment (p=.006, g=.32) groups had higher word reading scores than the ADHD treatment group, but did not differ significantly from one another (p=.470, g=.09). Similarly, the reading treatment (p=.0004, g=.39) and combined treatment (p=.004, g=.39) groups had higher phonemic decoding scores than the ADHD treatment group, but did not differ from one another (p=.629, g=.00).

Adherence

For ADHD only, medication adherence was negatively associated with parent hyperactivity/impulsivity ratings (r=−0.30, p<.05) and teacher inattention (r=−0.32, p<.01) and hyperactivity/impulsivity ratings (r=−0.34, p<.01); parent training adherence was negatively associated with teacher inattention ratings (r=−0.26, p<.05). Although not significant, the correlations between parent training attendance and parent ADHD symptom ratings were in the expected direction (r=−.11 for parent inattention and r=−.18 for parent hyperactivity/impulsivity for the combined treatment, and r=−.08 for parent inattention and r=−.11 for parent hyperactivity/impulsivity for the ADHD treatment).

For the combined condition, reading adherence did not correlate significantly with any of the dependent variables. In contrast, medication adherence correlated negatively with teacher ratings of inattention (r=−0.29, p<.05) and hyperactivity/impulsivity (r=−0.32, p<.05), and parent training attendance correlated negatively with teacher ratings of inattention (r=−0.28, p<.05) and hyperactivity/impulsivity (r=−0.26, p<.05) in the combined condition. Thus, higher medication adherence and/or parent-training attendance was associated with more improvement in ADHD symptom ratings.

For reading only, adherence was not associated with the ADHD or reading variables. Correlations between reading intervention attendance and reading outcomes were mostly in the expected direction (r=.13 for word reading and r=.01 for pseudoword decoding for the combined treatment, and r=.20 for word reading and r=.15 for pseudoword decoding for the reading only treatment) although not significant.

Follow-up Treatment Effects (Table 3; graphical presentation of data in supplemental materials)

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics and Treatment Effects at Follow-Up

| Pretest M (SD)a |

Follow-Up LSM (SE)b |

Follow-Up Treatment Effects |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Comb | ADHD | Read | Comb | ADHD | Read | ||

| Parent Inattention | 2.2 (0.5) | 2.1 (0.6) | 2.1 (0.6) | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.3 (0.1) | 1.6 (0.1) | F(2,180)=11.2** |

| n=66 | n=77 | n=73 | n=52 | n=66 | n=66 | Comb=ADHD<Read | |

| Parent Hyp/Imp | 1.6 (0.6) | 1.6 (0.9) | 1.7 (0.8) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 1.4 (0.1) | F(2,180)=16.9** |

| n=66 | n=77 | n=73 | n=52 | n=66 | n=66 | ADHD=Comb<Read | |

| Teacher Inattention | 2.2 (0.6) | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.3 (0.6) | 1.5 (0.1) | 1.5 (0.1) | 1.9 (0.1) | F(2,175)=5.5** |

| n=63 | n=74 | n=72 | n=51 | n=65 | n=65 | ADHD=Comb<Read | |

| Teacher Hyp/Imp | 1.4 (1.0) | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.5 (0.9) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) | F(2,173)=5.7** |

| n=63 | n=74 | n=72 | n=51 | n=65 | n=65 | ADHD=Comb<Read | |

| Word Reading | 73.8 (8.8) | 75.4 (8.5) | 75.2 (9.3) | 78.8 (0.8) | 77.1 (0.8) | 78.1 (0.8) | F(2,194)=1.10 |

| n=66 | n=77 | n=73 | n=59 | n=71 | n=68 | ||

| Phonemic Decoding | 73.3 (7.3) | 73.4 (9.7) | 75.1 (9.7) | 81.9 (1.2) | 77.1 (1.0) | 82.6 (1.1) | F(2,194)=8.05** |

| n=66 | n=77 | n=73 | n=59 | n=71 | n=68 | Read=Comb>ADHD | |

Note: Treatment Effects = Effect of treatment controlling for pre-test scores; Comb = combined treatment; Read = reading treatment; ADHD = ADHD treatment; Hyp/Imp = Hyperactivity/Impulsivity.

Pretest observed score means provided to describe initial impairment;

Follow-up scores are covariate-adjusted change scores.

p < .05;

p < .01

Parent ADHD ratings

The ADHD (p=.012, g=.46) and combined (p<.001, g=.84) groups had lower inattention ratings than the reading treatment group, but did not differ significantly from one another (p=.058, g=.38). For parent hyperactivity ratings, the ADHD treatment (p<.001, g=.77) and the combined treatment (p<.001, g=.98) groups were rated as significantly less hyperactive/impulsive than the reading treatment group but did not significantly differ from one another (p=.098, g=.21).

Teacher ADHD ratings

The ADHD (p=.006, g=.52) and combined (p=.020, g=.46) treatment groups were rated as significantly less inattentive than the reading treatment group but did not differ from one another (p=.756, g=.06). Similarly, teacher ratings of hyperactivity/impulsivity were lower for the ADHD (p=.011, g=.44) and combined (p=.008, g=.49) treatment groups than the reading treatment group but not from one another (p=.756, g=.05).

Reading performance

The reading (p<.001, g=.47) and combined (p<.001, g=.41) treatment groups had higher phonemic decoding scores than the ADHD treatment group but did not differ from one another (p=.65, g=.06). There were not significant differences between groups on word reading at follow-up.

Exploratory Crossover Analyses (Table 4)

Table 4.

Cross-over analyses excluding children who received medication (n=15) and/or parent training (n=3) from reading intervention group and excluding children who received supplemental reading instruction (n=27) in the ADHD treatment group at post-test

| Posttest LSM (SE)a |

Posttest Treatment Effects |

Follow-up LSM (SE)a |

Follow-up reatment Effects |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Comb | ADHD | Read | Comb | ADHD | Read | |||

| Parent Inattention | 0.95 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | F(2,152)=22.24** ADHD=Comb<Read |

1.0 (0.1) | 1.2 (0.1) | 1.6 (0.1) | F(2,138)=9.53** Comb=ADHD<Read |

| Parent Hyp/Imp | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 1.4 (0.1) | F(2,152)=24.15** ADHD=Comb<Read |

0.7 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 1.4 (0.1) | F(2,138)=15.8** ADHD=Comb<Read |

| Teacher Inattention | 1.4 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | F(2,154)=9.53** ADHD<Comb<Read |

1.5 (0.1) | 1.3 (0.1) | 1.8 (0.1) | F(2,137)=4.4*** ADHD=Comb<Read |

| Teacher Hyp/Imp | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) | F(2,154)=11.08** ADHD=Comb<Read |

0.8 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) | F(2,135)=3.3* ADHD=Comb<Read |

| Word Reading | 79.9 (0.7) | 77.9 (0.8) | 78.3 (0.7) | F(2,158)=2.08 | 78.8 (0.8) | 78.2 (0.9) | 78.3 (0.9) | F(2,150)=0.13 |

| Phonemic Decoding | 82.7 (1.1) | 77.5 (1.3) | 83.7 (1.2) | F(2,203)=7.21** Read=Comb>ADHD |

81.5 (1.2) | 77.4 (1.4) | 82.0 (1.3) | F(2,150)=3.67* Read=Comb>ADHD |

Note: Treatment Effects = Effect of treatment controlling for pre-test scores; Comb = combined treatment; Read = reading treatment; ADHD = ADHD treatment; Hyp/Imp = Hyperactivity/Impulsivity.

Covariate-adjusted change scores.

p < .05;

p < .01

Results of the exploratory analyses excluding participants who received medication and/or parent training in the reading only group, and excluding participants who received supplemental reading instruction in the ADHD only group, showed the exact same pattern of results as the primary analyses with two exceptions. 1) At post-test, for teacher inattention, the ADHD group was rated as significantly less inattentive than the combined treatment (p<.022, g=.41) and reading (p<.001, g=.79) treatment groups, and the combined treatment group was rated as significantly less inattentive than the reading treatment group (p<.023, g=.38); and 2) at post-test, the main effect of treatment on Word Reading was no longer significant (p=.128).

DISCUSSION

This is the largest study to date to evaluate the effects of disorder-specific and combined treatment strategies for elementary school-aged children with well-characterized ADHD and word reading difficulties or disabilities (n=216). Children with ADHD/RD who received only ADHD treatment had significantly greater reduction in ADHD symptoms compared with those who received only reading treatment. Children who received only reading intervention had significantly better word reading and decoding outcomes than those who received only ADHD treatment. While it is clear that ADHD treatments are necessary to target ADHD-related outcomes and reading treatments are necessary to target reading outcomes, receiving both treatments simultaneously does not appear to increase the effectiveness of these treatments on ADHD or reading outcomes. However, since it appears that both disorder-specific forms of treatment are necessary in order to treat the range of impairments for children with ADHD/RD, the optimal treatment strategy is clearly a combination of ADHD and RD treatment.

Effect sizes were moderate to large for the ADHD outcomes, particularly inattention ratings, consistent with literature showing large effect sizes for medication on ADHD symptomatology (Swanson et al., 1993). Importantly, reductions in ADHD symptomatology were clinically meaningful with children moving from the symptomatic range (scores of 2 or more on the ADHD rating scale which reflect moderate to severe symptoms) to the mildly symptomatic range (scores of 1 or less reflecting just a little or occasional symptoms). Effect sizes for reading outcomes were somewhat smaller than usually seen for word reading interventions in grades 2–5 (Elbaum, Vaughn, Hughes, & Moody, 2000; Wanzek & Vaughn, 2007; Wanzek, Wexler, Vaughn, & Ciullo, 2010). Differences between our study findings and these previous studies may be due to the fact that (a) the intervention in the current study was shorter (i.e., 16 weeks) than typically provided to students with serious RDs; (b) participants had both ADHD and RD, which has been associated with poorer response to reading intervention (Nelson et al., 2003); and/or (c) our study compared the RD treatment was compared to an alternative treatment (i.e., ADHD treatment), whereas other studies frequently contrast reading treatment with no supplemental treatment or typical school instruction (Elbaum et al., 2000). Regardless, these reading treatment gains of approximately half a standard deviation on reading standard scores are considered clinically meaningful (Institute of Education Sciences, 2013; Nigg, Swanson, & Hinshaw, 1997; Norman, Sloan, & Wyrwich, 2003). However, despite gains during the intervention period, on average, children in all groups remained impaired in word reading and phonological decoding at the end of the study (i.e., mean standard scores ranging from 75 to 80), suggesting need for more extended intervention [see (Vaughn, Denton, & Fletcher, 2010)].

The need to treat ADHD and RD with relevant disorder-specific interventions may be related to the unique cognitive profiles associated with the two disorders. For example, deficits in phonological awareness and other aspects of phonological processing are particularly characteristic of RD but not ADHD (Fletcher et al., 2007), while ADHD is associated with a variety of executive function deficits (Barkley, 1997). Individuals with comorbid ADHD/RD demonstrate characteristics of both disorders but do not seem to have a unique cognitive profile (Fletcher et al., 2007). Prior research has shown that treatment with ADHD medication alone can improve reading outcomes in children with comorbid ADHD/RD, but others have reported that treatment with ADHD medication does not impact cognitive-linguistic processes related to reading (Balthazor et al., 1991; Bental & Tirosh, 2008; de Jong et al., 2009; Holmes et al., 2010). In prior studies of the impact of medication on reading, medication may have allowed children to better demonstrate what they know on assessments without impacting underlying reading-related processes.

At follow-up three- to five-months after the study-related treatment had ended, the ADHD and combined intervention groups were still rated as less inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive than the reading intervention group. Significant group differences for pseudoword decoding were also evident at follow-up, indicating that the reading treatment remained superior to ADHD treatment. Group differences in word reading were not significant at follow-up; it should be noted, however, that changes in the covariate-adjusted mean word reading standard score from posttest to follow-up were small (i.e., loss of ~1 standard score point in reading treatment and combined groups, no change in ADHD treatment group; Table 2). Children would have probably benefitted from ongoing supplemental tutoring.

Combining ADHD and reading treatments for children with comorbid ADHD/RD did not enhance the effectiveness of disorder-specific treatments on ADHD symptoms or word reading or decoding outcomes for children in this study. Only one previously published study was found that investigated combined effects of ADHD and reading treatments on ADHD and reading outcomes, and that study reported inconclusive findings (Richardson et al., 1988). It is difficult to directly compare the present findings to those reported by Richardson et al., given that in that study (a) children were included based on hyperactive/impulsive symptoms, (b) the interventions were dissimilar (i.e., no parent training, reading intervention relied a great deal on parents), and (c) all children were tested at posttest off medication. Despite these key differences, results reported by Richardson et al. (1988) are largely congruent with those of the current study, finding little support for a synergistic effect for combined treatments of ADHD and RD. However, the current study illustrates the efficiency of treating the two conditions simultaneously. In addition, the fact that the main effect for word reading was no longer evident once children who received medication and/or parent training were excluded from the analysis (Exploratory Crossover Analyses, Table 4) suggests a possible advantage for simultaneous treatment for word reading.

Strengths of this study include the use of a randomized trial design and intent-to-treat analyses, which are more conservative and preserve the presumed equivalency of groups allowed by randomization, as well as strict selection criteria and monitoring of treatment delivery, resulting in high internal validity. Additionally, the majority of participants were low income African American children, an understudied at-risk group. Children from low income households are at higher risk for ADHD (Miech, Caspi, Moffitt, Wright, & Silva, 1999), and national reading assessments consistently indicate that significantly larger proportions of poor and African American students fail to achieve even basic reading proficiency, relative to White and higher-SES students (National Center for Education Statistics, 2015).

Despite these strengths, the findings of this study must be interpreted in light of its limitations. First, there was not a no-treatment control group; the mere act of participating in an intervention may account for some of the improvement reported for all groups. Although every effort was made to promote adherence, there was some cross-over between treatment groups as well as non-adherence, particularly for the ADHD treatment, which may have impacted our ability to detect treatment effects. In fact, adherence analyses revealed that children who adhered to the ADHD treatment had better ADHD outcomes, particularly teacher ratings. Further study is needed to investigate the relatively weaker association between adherence to parent training and parent-rated improvement in ADHD symptoms. Additionally, future studies may wish to measure parent-training adherence using alternative measures than attendance. For example, measures of treatment engagement/involvement, treatment satisfaction ratings, assessments of at home behavioral task completion, etc., could be utilized to provide a finer grained analysis of adherence. The fact that the majority of individuals were highly adherent to the reading intervention delivered in the schools may have reduced our ability to investigate and detect an association between adherence and reading outcomes (i.e., lack of range on this variable). Additionally, treatments were not sequenced such that an optimal response to ADHD treatment was established prior to initiating reading intervention, which may have impacted the ability to detect incremental benefits for the combined treatment group. In addition, potentially meaningful effect sizes on nonsignificant contrasts for combined treatment vs. ADHD treatment on teacher-rated inattention (g = .31) indicate that further study with a larger sample size may be needed to confirm a lack of synergistic effects of combined interventions on ADHD outcomes. Another potential limitation is that we did not track nor enforce uptake of the daily report card component of the parenting intervention, nor did we implement a classroom-based behavioral intervention which may have had more impact on reading outcomes than the home-based treatment regimen. Finally, the current results describe intervention effects on word reading and phonemic decoding; the pattern of findings may differ for other reading outcomes (comprehension, fluency, etc.) or for more global measures of functioning.

When generalizing the results of this study to other populations of children with comorbid ADHD and RD, the characteristics of those children should be compared to those of children in our sample. First, the reading inclusion criteria in the current study resulted in a sample of children with word-reading difficulties; results may differ for children who are primarily impaired in reading comprehension. Although the reading inclusionary criteria were not as stringent as might be used in clinical practice, our sample had mean baseline word reading and decoding scores at the 4th and 5th percentiles; moreover, our analysis indicated that baseline level of reading impairment did not interact with study outcomes. The average IQ of participants in this study may somewhat limit generalization to populations with higher IQs, although there is strong evidence that IQ makes only a very small contribution to predictions of response to reading interventions (Stuebing, Barth, Molfese, Weiss, & Fletcher, 2009). Finally, while oversampling of low income, African American children provides valuable information about treatment of this understudied population, it may also limit generalizability.

Overall, the results of this study suggest that disorder-specific treatments are required for children with comorbid ADHD/RD. It did not find support for the common perception that for children with ADHD and a comorbid disorder, treating ADHD allows children to maximally benefit more from other forms of treatment through improved readiness to learn (Pelham & Waschbusch, 1999). This has important implications for educators, clinicians, and families who may wonder whether a child with comorbid ADHD/RD can be successfully treated by only remediating word reading difficulties or by only addressing ADHD symptoms. These children appear to benefit most from treatment of both disorders. Future studies should assess potential moderators of treatment outcomes, as well as the relative benefits of the ADHD, reading, and combined interventions on alternate outcomes (e.g., reading comprehension, executive functioning, quality of life, global impression of improvement considering all variables, etc.).

Supplementary Material

Public Health Significance.

This study strongly suggests that children with comorbid ADHD and word-reading difficulties and disabilities will benefit from disorder-aligned treatments (i.e., medication + parent training for ADHD, intensive reading instruction for RD). Combining the treatments allows for efficient treatment of both disorders but the additive value within disorder is not significant.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant R01 HD060617 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NICHD or National Institutes of Health. We acknowledge the contributions of Peter Jensen, Jack Fletcher, Erik Willcutt, and Ben Heller to the study’s conceptualization and design. We are also grateful to the families, teachers, and school personnel involved in this project and for the support of research staff.

Footnotes

The follow-up window varied as the testing was done in the child’s school; no testing occurred in the summer months.

In a few cases (n=6), children were started on a low dose of mixed amphetamine salts rather than MPH (three could not swallow pills and three had previous severe side effects on MPH).

In some instances, children did not reach a CGI score of 2 but the families were not willing to increase or change medications and were entered into maintenance with a CGI score of 3.

Contributor Information

Leanne Tamm, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Carolyn A. Denton, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston

Jeffery N. Epstein, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Christopher Schatschneider, Florida State University.

Heather Taylor, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

L. Eugene Arnold, Ohio State University.

Oscar Bukstein, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School.

Julia Anixt, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Anson Koshy, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Nicholas C. Newman, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Jan Maltinsky, Mount St. Joseph University.

Patricia Brinson, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Richard Loren, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Mary R. Prasad, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston

Linda Ewing-Cobbs, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Aaron Vaughn, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

References

- American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(7):894–921. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318054e724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthazor MJ, Wagner RK, Pelham WE. The specificity of the effects of stimulant medication on classroom learning-related measures of cognitive processing for attention deficit disorder children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1991;19(1):35–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00910563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. Defiant children: A clinician’s manual for parent training. London: Guilford Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, self-regulation, and time: Toward a more comprehensive theory. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1997;18(4):271–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bental B, Tirosh E. The effects of methylphenidate on word decoding accuracy in boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2008;28(1):89–92. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e3181603f0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breaux KC. Wechsler Individual Achievement Test 3rd Edition (WIAT III) - Technical Manual. Bloomington: Pearson; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bussing R, Fernandez M, Harwood M, Wei Hou, Garvan CW, Eyberg SM, Swanson JM. Parent and teacher SNAP-IV ratings of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms: psychometric properties and normative ratings from a school district sample. Assessment. 2008;15(3):317–328. doi: 10.1177/1073191107313888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chard DJ, Vaughn S, Tyler BJ. A synthesis of research on effective interventions for building reading fluency with elementary students with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2002;35(5):386–406. doi: 10.1177/00222194020350050101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(1):155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong CG, Van De Voorde S, Roeyers H, Raymaekers R, Allen AJ, Knijff S, … Sergeant JA. Differential effects of atomoxetine on executive functioning and lexical decision in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and reading disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2009;19(6):699–707. doi: 10.1089/cap.2009.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton CA, Tolar TD, Fletcher JM, Barth AE, Vaughn S, Francis DJ. Effects of Tier 3 Intervention for Students With Persistent Reading Difficulties and Characteristics of Inadequate Responders. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2013;105(3):633–648. doi: 10.1037/a0032581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton CA, Hocker JL. Responsive reading instruction: Flexible intervention for struggling readers in the early grades. Longmont: Sopris West; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Elbaum B, Vaughn S, Hughes MT, Moody SW. How effective are one-to-one tutoring programs in reading for elementary students at risk for reading failure? A meta-analysis of the intervention research. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2000;92(4):605–619. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.92.4.605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. New York: Guilford; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Evans SW, Owens JS, Bunford N. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43(4):527–551. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.850700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Weber W, Russell RL. Psychiatric, neuropsychological, and psychosocial features of DSM-IV subtypes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: results from a clinically referred sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37(2):185–193. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199802000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JM. Dyslexia: The evolution of a scientific concept. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2009;15(4):501–508. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709090900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JM, Lyon GR, Fuchs LS, Barnes MA. Learning disabilities: From identification to intervention. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JM, Stuebing KK, Barth AE, Denton CA, Cirino PT, Francis DJ, Vaughn S. Cognitive correlates of inadequate response to reading intervention. School Psychology Review. 2011;40:3–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs D, Fuchs LS, Compton DL. Identifying reading disabilities by responsiveness-to-instruction: Specifying measures and criteria. Learning Disability Quarterly. 2004;27:216–227. [Google Scholar]

- Gau SS, Shang CY, Liu SK, Lin CH, Swanson JM, Liu YC, Tu CL. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham, version IV scale - parent form. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2008;17(1):35–44. doi: 10.1002/mpr.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grizenko N, Bhat M, Schwartz G, Ter-Stepanian M, Joober R. Efficacy of methylphenidate in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and learning disabilities: a randomized crossover trial. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 2006;31(1):46–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiebert EH. Quick Reads: A research-based fluency program. Parsippany: Modern Curriculum Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes J, Gathercole SE, Place M, Dunning DL, Hilton KA, Elliott JG. Working memory deficits can be overcome: Impacts of training and medication on working memory in children with ADHD. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2010;24(6):827–836. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Education Sciences. What Works Clearinghouse procedures and standards handbook. 3. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson LA, Ryan M, Denckla MB, Mostofsky SH, Mahone EM. Performance Lapses in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Contribute to Poor Reading Fluency. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2013;28(7):672–683. doi: 10.1093/arclin/act048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson LA, Ryan M, Martin RB, Ewen J, Mostofsky SH, Denckla MB, Mahone EM. Working memory influences processing speed and reading fluency in ADHD. Child Neuropsychology. 2011;17(3):209–224. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2010.532204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test - Second Edition. Circle Pines: AGS; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Keulers EH, Hendriksen JG, Feron FJ, Wassenberg R, Wuisman-Frerker MG, Jolles J, Vles JS. Methylphenidate improves reading performance in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and comorbid dyslexia: An unblinded clinical trial. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 2007;11:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Shear MK, Klerman GL, Portera L, Rosenbaum JF, Goldenberg I. A comparison of symptom determinants of patient and clinician global ratings in patients with panic disorder and depression. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1993;13:327–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon GR. The state of research. In: Cramer S, Ellis W, editors. Learning Disabilities: Lifelong Issues. Baltimore: Paul H. Brooks Publishing Co; 1996. pp. 3–61. [Google Scholar]

- Massetti GM, Lahey BB, Pelham WE, Loney J, Ehrhardt A, Lee SS, Kipp H. Academic achievement over 8 years among children who met modified criteria for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder at 4–6 years of age. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36(3):399–410. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9186-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes SD, Calhoun SL. Learning, attention, writing, and processing speed in typical children and children with ADHD, autism, anxiety, depression, and oppositional-defiant disorder. Child Neuropsychology. 2007;13(6):469–493. doi: 10.1080/09297040601112773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara JK, Willoughby TL, Chalmers H, YLC-CURA Psychosocial status of adolescents with learning disabilities with and without comorbid Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Learning Disabilities Research and Practices. 2005;20(4):234–244. [Google Scholar]

- Miech RA, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Wright BRE, Silva PA. Low socioeconomic status and mental disorders: A longitudinal study of selection and causation during young adulthood. American Journal of Sociology. 1999;104(4):1096–1131. [Google Scholar]

- MTA Cooperative Group. A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999a;56(12):1073–1086. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MTA Cooperative Group. Moderators and mediators of treatment response for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999b;56:1088–1096. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. National assessment of educational progress: 1990–2015 reading assessments. 2015 from http://www.nationsreportcard.gov/reading_math_2015/#reading?grade=4.

- National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidence based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington, D.C: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2000. (NIH Publication No. 00-4754) [Google Scholar]

- Nelson RJ, Benner GJ, Gonzalez J. Learner characteristics that influence the treatment effectiveness of early literacy interventions: A meta-analytic review. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice. 2003;18:255–267. [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Swanson JM, Hinshaw SP. Covert visual spatial attention in boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: lateral effects, methylphenidate response and results for parents. Neuropsychologia. 1997;35(2):165–176. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(96)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Medical Care. 2003;41(5):582–592. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE. Pharmacotherapy for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. School Psychology Review. 1993;22:199–227. [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Waschbusch DA. Behavioral intervention in attention/deficit-hyperactivity disorder. In: Quay HC, Logan AE, editors. Handbook of Disruptive Behavior Disorders. New York: Kluwer Academic; 1999. pp. 255–278. [Google Scholar]

- Perfetti CA, Landi N, Oakhill J. The acquisition of reading comprehension skill. In: Snowling MJ, Hulme C, editors. The Science of Reading: A Handbook. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2005. pp. 227–247. [Google Scholar]

- Petscher Y, Schatschneider C. A Simulation Study on the Performance of the Simple Difference and Covariance-Adjusted Scores in Randomized Experimental Designs. Journal of Educational Measurement. 2011;48(1):31–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3984.2010.00129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purvis KL, Tannock R. Phonological processing, not inhibitory control, differentiates ADHD and reading disability. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(4):485–494. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200004000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabiner DL, Malone PS Conduct Problems Prevention Research, Group. The impact of tutoring on early reading achievement for children with and without attention problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32(3):273–284. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000026141.20174.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabiner DL, Murray DW, Skinner AT, Malone PS. A randomized trial of two promising computer-based interventions for students with attention difficulties. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38(1):131–142. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9353-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson E, Kupietz SS, Winsberg BG, Maitinsky S, Mendell N. Effects of methylphenidate dosage in hyperactive-reading disabled children: II. Reading achievement. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1988;27(1):78–87. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198801000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts G, Rane S, Fall AM, Denton CA, Fletcher JM, Vaughn S. The impact of intensive reading intervention on level of attention in middle school students. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2015;44(6):942–953. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.913251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucklidge JJ, Tannock R. Neuropsychological profiles of adolescents with ADHD: effects of reading difficulties and gender. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2002;43(8):988–1003. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman LJ, Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Doyle AE, Faraone SV. Learning disabilities and executive dysfunction in boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychology. 2001;15(4):544–556. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.15.4.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(1):28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaywitz BA, Williams DW, Fox BK, Wietecha LA. Reading outcomes of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and dyslexia following atomoxetine treatment. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2014;24(8):419–425. doi: 10.1089/cap.2013.0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Kuriyan AB, Evans SW, Waxmonsky JG, Smith BH. Pharmacological and psychosocial treatments for adolescents with ADHD: an updated systematic review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2014;34(3):218–232. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuebing KK, Barth AE, Molfese PJ, Weiss B, Fletcher JM. IQ is not strongly related to response to reading instruction: A meta-analytic interpretation. Exceptional Children. 2009;76(1):31–51. doi: 10.1177/001440290907600102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner CR, Gathercole S, Greenbaum M, Rubin R, Williams D, Hollandbeck M, Wietecha L. Atomoxetine for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children with ADHD and dyslexia. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2009;3:40. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-3-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JM. School Based Assessments and Interventions for ADHD Students. Irvine, CA: KC Publishing; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JM, McBurnett K, Wigal T, Pfiffner LJ, Lerner MA, Williams L, … Fisher TD. Effect of stimulant medication on children with attention deficit disorder: A “review of reviews. Exceptional Children. 1993;60:154–162. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez J. The Annie E. Casey Foundation. Double Jeopardy: How Third Grade Reading Skill and Poverty Influence High School Graduation. Baltimore: Ann. E. Casey Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Torgesen JK. Individual differences in response to early interventions in reading: The lingering problem of treatment resisters. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice. 2000;15:55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Torgesen JK, Alexander AW, Wagner RK, Rashotte CA, Voeller KK, Conway T. Intensive remedial instruction for children with severe reading disabilities: immediate and long-term outcomes from two instructional approaches. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2001;34(1):33–58. 78. doi: 10.1177/002221940103400104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadasy PF, Sanders E. Sound Partners Plus. Seattle: Washington Research Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vadasy PF, Sanders EA, Tudor S. Effectiveness of paraeducator-supplemented individual instruction: Beyond basic decoding skills. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2007;40(6):508–525. doi: 10.1177/00222194070400060301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadasy PF, Wayne SK, O’Connor RE, Jenkins JR, Pool K, Firebaugh M, Peyton JA. Sound Partners: A Tutoring Program in Phonics-Based Early Reading. Longmont: Sopris West; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Denton CA, Fletcher JF. Why intensive interventions are necessary for students with severe reading difficulties. Psychology in the Schools. 2010;47:432–444. doi: 10.1002/pits.20481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellutino FR, Fletcher JM, Snowling MJ, Scanlon DM. Specific reading disability (dyslexia): What have we learned in the past four decades? Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2004;45(1):2–40. doi: 10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellutino FR, Scanlon DM, Small S, Fanuele DP. Response to intervention as a vehicle for distinguishing between children with and without reading disabilities: Evidence for the role of kindergarten and first-grade interventions. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2006;39(2):157–169. doi: 10.1177/00222194060390020401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanzek J, Vaughn S. Research-based implications from extensive early reading interventions. School Psychology Review. 2007;36(4):541–561. [Google Scholar]

- Wanzek J, Wexler J, Vaughn S, Ciullo S. Reading interventions for struggling readers in the upper elementary grades: A synthesis of 20 years of research. Reading and Writing. 2010;23ek(8):889–912. doi: 10.1007/s11145-009-9179-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Individual Achievement Test 3rd Edition (WIAT III) London: The Psychological Corp; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Willcutt EG, Betjemann RS, McGrath LM, Chhabildas NA, Olson RK, DeFries JC, Pennington BF. Etiology and neuropsychology of comorbidity between RD and ADHD: the case for multiple-deficit models. Cortex. 2010;46(10):1345–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willcutt EG, Doyle AE, Nigg JT, Faraone SV, Pennington BF. Validity of the executive function theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analytic review. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57(11):1336–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willcutt EG, Pennington BF. Comorbidity of reading disability and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: differences by gender and subtype. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2000;33(2):179–191. doi: 10.1177/002221940003300206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willcutt EG, Pennington BF, Olson RK, Chhabildas N, Hulslander J. Neuropsychological analyses of comorbidity between reading disability and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: in search of the common deficit. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2005;27(1):35–78. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2701_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson D, Murray DW, Damaraju CV, Ascher S, Starr HL. Methylphenidate in children with ADHD with or without learning disability. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2014;18(2):95–104. doi: 10.1177/1087054712443411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolraich ML, Feurer ID, Hannah JN, Baumgaertel A, Pinnock TY. Obtaining systematic teacher reports of disruptive behavior disorders utilizing DSM-IV. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26:141–152. doi: 10.1023/a:1022673906401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW, McGrew KS, Mather N. Woodcock-Johnson III. Itasca: Riverside; 2001. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.