Abstract

Objective

To examine associations between glucoregulation and three categories of psychological resources: hedonic well-being (i.e., life satisfaction, positive affect), eudaimonic well-being (i.e., personal growth, purpose in life, ikigai) and interdependent well-being (i.e., gratitude, peaceful disengagement, adjustment) among Japanese adults. The question is important given increases in rates of type 2 diabetes in Japan in recent years, combined with the fact that most prior studies linking psychological resources to better physical health have utilized Western samples.

Methods

Data came from the Midlife in Japan (MIDJA) Study involving randomly selected participants from the Tokyo metropolitan area, a subsample of whom completed biological data collection (N=382; 56.0% female; M(SD)age = 55.5(14.0) years). Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was the outcome. Models adjusted for age, gender, educational attainment, smoking, alcohol, chronic conditions, body mass index, use of anti-diabetic medication, and negative affect.

Results

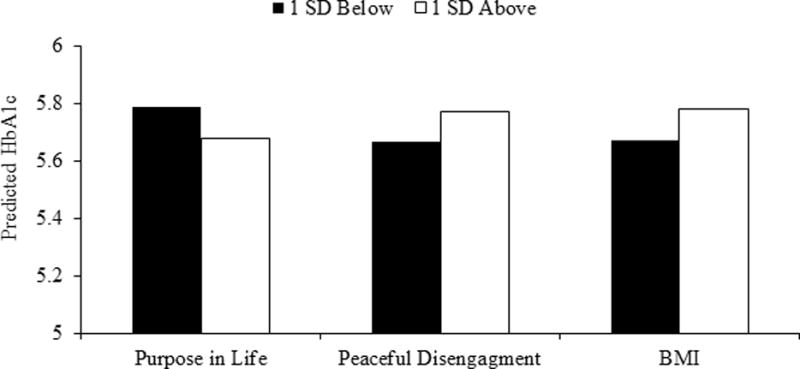

Purpose in life (β = −.102, p = .022) was associated with lower HbA1c, and peaceful disengagement (β = .124, p = .004) was associated with higher HbA1c in fully adjusted models. Comparable to the effects of BMI, a one standard deviation change in well-being was associated with a .1% change in HbA1c.

Conclusions

Associations among psychological resources and glucoregulation were mixed. Healthy glucoregulation was evident among Japanese adults with higher levels of purpose in life and lower levels of peaceful disengagement, thereby extending prior research from the U.S. The results emphasize the need for considering sociocultural contexts in which psychological resources are experienced in order to understand linkages to physical health.

Keywords: hedonic well-being, eudaimonic well-being, glucoregulation, cultural psychology, psychological well-being, glycosylated hemoglobin

The health benefits associated with psychological well-being are well-documented. Across multiple health outcomes and indices of psychological well-being, evidence supports positive psychological functioning as predictive of better health, including lower morbidity and mortality (Boehm & Kubzansky, 2012; Chida & Steptoe, 2008; Kim, Park, Sun, Smith, & Peterson, 2014; Kim, Strecher, & Ryff, 2014; Kim, Sun, Park, Kubzansky, & Peterson, 2012; Kim, Sun, Park, & Peterson, 2013; Pressman & Cohen, 2005). Importantly, salubrious effects stem from the presence of well-being, and not simply the absence of poor psychological ill-being, such as depression or anxiety (Keyes, 2002). However, most prior research has utilized samples from the United States and other Western European countries. Therefore, it is unknown whether these results extend to other cultural contexts, where well-being may have different meanings and possibly unique linkages to health. To address these issues, we examined associations between several varieties of psychological well-being and a marker of glucoregulation in a large sample of Japanese adults.

Psychological well-being is not a unitary construct, but rather is multidimensional and includes both hedonic and eudaimonic dimensions (Keyes, Shmotkin, & Ryff, 2002; Ryan & Deci, 2001). Hedonic well-being is characterized by pleasure-seeking and happiness and is typically measured with scales of positive affect, happiness, and life satisfaction. Eudaimonic well-being, in contrast, concerns self-realization and thriving via pursuit of meaningful goals and experiences of personal growth and development (Keyes et al., 2002; Ryan & Deci, 2001). Both broad types of well-being reflect Western conceptions, although we note that in Japan, enhanced longevity has been associated with the concept of ikigai, which translates roughly to having a reason for being and thus is conceptually similar to purpose or meaning in life. Across three large samples, Japanese individuals who report having ikigai had lower mortality rates (Cohen, Bavishi, & Rozanski, 2016; Koizumi, Ito, Kaneko, & Motohashi, 2008; Sone et al., 2008; Tanno et al., 2009). As an interdependent culture (Markus & Kitayama, 1991, 2010), other aspects of well-being in Japan involve showing understanding and concern for others so as to promote social harmony and connectedness (Uchida, Norasakkunkit, & Kitayama, 2004). Experiences of gratitude and appreciation for simply being alive and peaceful disengagement from a continually changing and confusing reality emerged as two factors of minimalist well-being that are distinct among Japanese adults (Kan, Karasawa, & Kitayama, 2009). Well-being in Japan also involves adjusting and orienting to others (Kitayama & Markus, 2000; Ryff et al., 2014).

In the current study, we focus on glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), as the primary indicator of glucoregulation and physical health. HbA1c is used as a diagnostic criterion for type-2 diabetes, which constitutes a major public health burden, affecting over 240 million people and hundreds of billions of dollars worldwide (van Dieren, Beulens, van der Schouw, Grobbee, & Neal, 2010). Japan has the fifth largest population of diabetics in the world, and its rates of type-2 diabetes are increasing at an alarming rate (International Diabetes Federation, 2013; Morimoto, Nishimura, & Tajima, 2010). Elevated HbA1c is also a risk factor for other adverse health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all-cause mortality, independent of diabetes status (de Beer & Liebenberg, 2014; Khaw et al., 2004).

The modest literature linking well-being to HbA1c has yielded mixed results, with many studies finding null associations with hedonic (Paschalides et al., 2004) and eudaimonic well-being (Bradshaw et al., 2007; Feldman & Steptoe, 2003; Ryff et al., 2006). However, in a sample of older women, positive affect predicted lower (i.e., healthier) HbA1c over a two year follow up, controlling for baseline HbA1c, and purpose in life and personal growth were protective against increases in HbA1c for those of low socioeconomic status (Tsenkova, Love, Singer, & Ryff, 2007)). More recently, perceived control was cross-sectionally associated with lower HbA1c in a national sample of older adults (Infurna & Gerstorf, 2014). Hedonic and eudaimonic well-being were both cross-sectionally and prospectively associated with lower risk of metabolic syndrome within the MIDUS national sample, although associations were driven primarily by waist circumference and lipids, and not with glucoregulation (Boylan & Ryff, 2015). Other findings from MIDUS demonstrated that life satisfaction was associated with lower incident cardiometabolic conditions as well as lower cardiometabolic risk scores, measured with a composite of biomarkers that included HbA1c (Boehm et al., 2016). Additionally, purpose in life was associated with healthier allostatic load profiles, including a marginal association with a composite measure of glucoregulation (Zilioli et al., 2015).

The current inquiry examines cross-sectional associations between HbA1c and three categories of psychological resources: hedonic well-being (i.e., positive affect, life satisfaction), eudaimonic well-being (i.e., personal growth, purpose in life, and ikigai), and interdependent well-being (i.e., peaceful disengagement, gratitude, adjustment) (Kan et al., 2009; Kitayama, Karasawa, Curhan, Ryff, & Markus, 2010). Based on prior literature, we hypothesized that eudaimonic well-being, especially ikigai and purpose in life, would predict lower levels of HbA1c. We hypothesized that hedonic well-being would not be associated with HbA1c given prior evidence that positive emotions are less valued and experienced less frequently in East Asian cultures, such as Japan, compared to the U.S. (Bastian, Kuppens, De Roover, & Diener, 2014; Miyamoto & Ma, 2011). For our final category of interdependent well-being, we speculated that these psychological resources might also predict better glucoregulation, although no prior studies have examined such associations and as such, these associations should be interpreted as preliminary.

While the primary focus of the study was on varieties of well-being and glucoregulation, supplemental analyses examined associations between well-being and three other cardiovascular risk factors (systolic blood pressure, ratio of total to HDL cholesterol, and waist circumference). These were done to facilitate comparisons with previously published findings of well-being and metabolic syndrome and other measures of cardiometabolic risk and allostatic load in the United States (Boehm et al., 2016; Boylan & Ryff, 2015; Zilioli et al., 2015). Lack of comparability in multiple areas of assessment (i.e., lack of fasting glucose, less comprehensive measurement of physical activity, and additional well-being measures of interest) precluded conducting exactly the same set of analyses in Japan.

Methods

Sample

Data came from the biological subsample of the Midlife in Japan (MIDJA) study (N=382; 56% female). The MIDJA survey sample was recruited in 2008 to proportionately reflect the 23 neighborhood wards in Tokyo, stratified by age and gender (N = 1027; 50.8% female; age range 30 – 79 years). Biological data (i.e., blood and urine) were collected from 37.2% of the MIDJA survey sample at a medical clinic near the University of Tokyo with timing in accordance with participant convenience. Eligibility criteria for the biomarker project included completing the initial survey and expressing interest in the biomarker phase by returning a postcard to the survey research firm. 72.3% of individuals who returned the postcard provided valid biological data (see Ryff et al., 2016 for complete study details). The participants who participated in the biomarker study (n=382) were very similar to those who did not participate (n =645) on demographic variables (age, educational attainment, family size, home ownership, employment status; ps > .30), although a significantly higher proportion of women participated in the biomarker study (p = .010) and there was a trend that married individuals also had greater participation in the biomarker study (p = .052). The health characteristics of the biomarker sample were also similar to the survey sample in terms of number of chronic conditions, number of prescription medications taken, and number of physician visits in the prior year (ps > .10). The biomarker sample, however, had marginally better subjective physical health (p = .10), was less likely to smoke (p =.004) and had lower scores on assessments of instrumental and basic activities of daily living as compared to those who did not participate in the biomarker study (ps < .01).

We also drew on data from the second wave of the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) study to compare associations between psychological resources and HbA1c and other cardiovascular risk factors within the United States and Japan. (Brim, Ryff, & Kessler, 2004; Radler & Ryff, 2010). We interpret the extent to which these associations were similar in magnitude to represent cultural similarities, whereas different associations between psychological resources and HbA1c and cardiovascular risk within the United States and Japan represented cultural-specific associations. MIDUS respondents were initially recruited in 1995–1996 via random digit dialing. The second wave of the study began in 2004, and biological data collection occurred 2004–2009. The biological sample was comparable to the survey sample on most demographic and health covariates, although the biological sample was better educated and less likely to smoke than the survey sample (Love, Seeman, Weinstein, & Ryff, 2010). To facilitate comparisons with Boylan and Ryff (2015), only the participants from the national study were included (i.e., data from the city-specific sample of African Americans from Milwaukee, WI was excluded).

Psychological Resource Measures

Eudaimonic well-being

All psychological resource measures were assessed as part of the MIDJA survey. Eudaimonic well-being was assessed based on Ryff’s theoretical model (Ryff & Keyes, 1995; Ryff, 1989) with 2 scales: Personal Growth (e.g., “For me, life has been a continuous process of learning, changing, and growth”) and Purpose in Life (e.g., “I have a sense of direction and purpose in life”). Each scale had seven items, and internal consistency was .74 for personal growth and .56 for purpose in life. Respondents also answered yes or no to whether or not they had ikigai in their life.

Hedonic well-being

Hedonic well-being was assessed via positive affect and life satisfaction. Positive affect was an average rating of how much of the time respondents felt, “cheerful,” “in good spirits,” “extremely happy,” “calm and peaceful,” “satisfied,” and “full of life” in the last 30 days on a four-point scale (α = .93) (Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998). The life satisfaction scale contained 5 items (e.g., “If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing.”) and was rated on a 7 point scale (1=strongly disagree; 7=strongly agree; α = .89) (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985).

Interdependent well-being

Eastern conceptions of well-being were assessed via gratitude (e.g., “I feel grateful that I am alive;” α = .79) and peaceful disengagement scales (e.g., “It feels good to do nothing and relax;” α = .68). Items were rated on a 7-point scale, and each scale contained 5 items (Kan et al., 2009). The Adjustment scale assessed how individuals viewed themselves as linked to others (e.g., “When values held by others sound more reasonable, I can adjust my values to theirs.”). The adjustment scale had 5 items, which were rated on a 7-point scale (α = .63).

Glycosylated Hemoglobin (HbA1c)

Whole blood was collected and analyzed in Tokyo to determine HbA1c using a latex agglutination assay (Showa Medical Service Co. LTD). Over 95% of biological samples were obtained between 0900 and 1145, with most of the remainder by 1330, and just 8 in the afternoon by 1530. The inter-assay coefficient of variance was 10%. Fasting glucose was not available in the MIDJA cohort.

Additional Cardiovascular Risk Factors

Systolic blood pressure was measured by clinic staff three times in a seated position following a five-minute resting period. At least 30 seconds passed between blood pressure readings. The second and third blood pressure readings were averaged as the outcome variable. For cholesterol assays, blood samples were collected, and frozen aliquots were shipped to Madison, WI for processing by Meriter Labs (Madison, WI), using a Cobas Integra analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Waist circumference was measured by clinic staff at the narrowest point between the ribs and the iliac crest to the nearest millimeter.

Covariates

Sociodemographic factors, health behaviors, and health status were included in models linking psychological resources and HbA1c to account for confounding influences and relevant mediating behavioral pathways. Specifically, age, gender, educational attainment (years completed), current smoking status, alcohol consumption (number of drinks per week), physical activity (dichotomized as ever (v. never) using exercise or movement therapy within the last 12 months, healthy eating (sum of high fat meat (reverse coded), fish, protein, fruit, vegetable, and sugared beverage (reverse coded) consumption; Levine et al., 2016), subjective sleep quality (4 response categories ranging from very good (coded 0) to very bad (coded 3); Buysse et al., 1988), body mass index (BMI; [weight (kilograms)/height squared (meters)], measurements taken by clinic staff), self-reported number of chronic conditions, excluding diabetes (out of 29 possible), and use of anti-diabetic medication were included as control variables. Negative affect (Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998) was also included as a control variable in order to assess the relative independence among psychological resources and general negative affectivity. Negative affect was measured on a 5-point scale (1=none of the time, 5= all of the time) as the mean of responses to six items asking how much of the time participants felt “so sad nothing could cheer you up,” “nervous,” “restless or fidgety,” “hopeless,” “that everything was an effort,” and “worthless” during the past 30 days.

Statistical Analyses

Hierarchical linear regression models were employed to examine associations between psychological resources and HbA1c. HbA1c and weekly alcohol consumption (+1) were log10 transformed to account for non-normality. Sociodemographic covariates and psychological resources were entered in the first step of the regression model, and then the health behaviors and health factor covariate measures were entered on the next step. Negative affect was entered on the final step of the regression model. Each resource measure was entered in a separate regression, and the relative contributions of significant resources were examined in a later analysis, adjusting for all covariates and negative affect. All continuous variables were z-scored prior to entry in the regression model and can be interpreted in standard deviation units.

Additional analyses were also run to test associations between well-being and three additional cardiovascular risk factors as outcomes, including systolic blood pressure, total to HDL cholesterol ratio (log10 transformed), and waist circumference. Covariates were identical to the models predicting HbA1c. Cultural differences in the link between well-being and HbA1c for a subset of well-being measures (personal growth, purpose in life, positive affect, life satisfaction, and adjustment) were tested with culture (United States v. Japan) by well-being interaction terms predicting HbA1c in a combined sample of MIDJA and MIDUS respondents.

Results

Descriptive information on the sample, including bivariate correlations between study variables and HbA1c, are presented in Table 1. Men, compared to women, were significantly more educated, had higher BMI, were more likely to be currently smoking, consumed more alcohol, had higher subjective sleep quality and had lower scores on the healthy eating index, positive affect, personal growth, gratitude, and peaceful disengagement. Preliminary analyses revealed no gender differences in the associations between psychological resources and HbA1c (p’s > .15), so both genders are included in the same models. HbA1c was positively correlated with age, BMI, and anti-diabetic medication use and negatively correlated with personal growth and purpose in life in bivariate analyses.

Table 1.

Descriptive information on study sample

| Total (N=382) |

M(SD) or % Men (n=168) |

Women (n=214) |

Gender p-value |

r with HbA1c |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55.5(14.0) | 56.7(14.0) | 54.5(14.0) | .13 | .366* |

| Education (years) | 13.5(2.4) | 14.0(2.6) | 13.1(2.1) | .001 | −.063 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.7(0.5) | 5.8(0.6) | 5.7(0.4) | .059 | |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 121.6(19.9) | 127.3(19.0) | 117.2(19.6) | <.001 | .280* |

| Ratio total/HDL cholesterol | 3.1(1.1) | 3.6(1.3) | 2.8(0.8) | <.001 | .292* |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 76.2(9.8) | 83.3(8.3) | 70.5(6.7) | <.001 | .277* |

| BMI | 22.6(3.0) | 23.7(2.9) | 21.7(2.7) | <.001 | .260* |

| Current Smoking | 21.5% | 33.3% | 12.1% | <.001 | .024 |

| Alcohol (drinks/week) | 7.2(11.8) | 11.0(10.7) | 4.2(11.7) | <.001 | −.020 |

| Exercise (% never in last 12 mo.) | 55.2% | 58.9% | 52.3% | .36 | .009 |

| Healthy eating index (z-score) | 0.0(1.0) | −.22(1.0) | .18(0.9) | <.001 | .049 |

| Subjective sleep quality | 1.2(0.7) | 1.1(0.6) | 1.2(0.7) | .010 | −.028 |

| Chronic Conditions | 2.3(2.0) | 2.2(2.0) | 2.4(2.1) | .38 | .081 |

| Anti-diabetic Medication use | 2.9% | 3.6% | 2.3% | .47 | .506* |

| Eudaimonic well-being | |||||

| Personal Growth | 34.4(5.5) | 33.8(5.4) | 34.9(5.6) | .050 | −.114* |

| Purpose in Life | 32.3(5.3) | 32.0(5.5) | 32.6(5.2) | .26 | −.142* |

| Ikigai (% yes) | 68.1% | 117/153 | 143/194 | .56 | −.071 |

| Hedonic well-being | |||||

| Positive Affect | 3.3(0.7) | 3.2(0.7) | 3.4 (0.8) | .023 | .069 |

| Life Satisfaction | 4.2(1.2) | 4.1(1.2) | 4.2(1.2) | .23 | −.010 |

| Interdependent well-being | |||||

| Gratitude | 26.4(4.6) | 25.8(4.3) | 26.9(4.7) | .023 | −.056 |

| Peaceful Disengagement | 23.0(4.7) | 22.3(4.6) | 23.6(4.7) | .005 | .080 |

| Adjustment | 4.3(0.7) | 4.2(0.7) | 4.4(0.7) | .040 | .068 |

| Negative Affect | 1.7(0.6) | 1.6(0.6) | 1.8(0.7) | .082 | −.046 |

Note. p-value reflects gender difference based on independent samples t-test or χ2 test for categorical variables.

p < .05. HbA1c and ratio of total to HDL cholesterol were log transformed for bivariate correlation analyses.

Table 2 presents results from the regression models predicting HbA1c. Each psychological resource variable was entered in a separate model. Adjusting for all covariates (Model 2), including age, gender, education, BMI, current smoking, alcohol consumption, exercise, healthy eating, subjective sleep quality, chronic conditions, and anti-diabetic medication use, purpose in life (β = −.104, t(340) = 2.33, p = .021) was associated with lower HbA1c and peaceful disengagement was associated with higher HbA1c (β = .129, t(340) = 2.99, p = .003). These effects remained significant with negative affect added to the model (purpose in life: β = -.108, p = .018; peaceful disengagement: β = .130, p = .003). When purpose in life and peaceful disengagement were entered simultaneously in a fully adjusted regression model, both purpose in life (β = −.093, p = .041) and peaceful disengagement (β = .120, p = .006) remained significant predictors of HbA1c. No significant interactions between culture and well-being were evident in the combined sample of MIDJA and MIDUS respondents (ps > .12).

Table 2.

Linear regression models with well-being predicting HbA1c as outcomea

| Model 1 Demographics |

Model 2 +Health Factors |

Model 3 +Negative Affect |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B(SE) | β | p | B(SE) | β | p | B(SE) | β | p | |

| Age | .014(.002) | .39 | <.001 | .013(.002) | .36 | <.001 | .013(.002) | .36 | <.001 |

| Gender (1=Female) | −.003(.004) | −.04 | .39 | .002(.004) | .02 | .69 | .002(.004) | .02 | .68 |

| Education (years) | .001(.002) | .04 | .51 | .002(.002) | .05 | .31 | .002(.002) | .05 | .31 |

| BMI | .004(.002) | .11 | .021 | .004(.002) | .11 | .024 | |||

| Current Smokingb | .001(.004) | .01 | .77 | .001(.004) | .01 | .76 | |||

| Alcohol (drinks/wk) | .000(.002) | −.01 | .89 | .000(.002) | −.01 | .88 | |||

| Exerciseb | .001(.001) | .03 | .52 | .001(.001) | .03 | .53 | |||

| Healthy eating index | −.003(.002) | −.07 | .15 | −.003(.002) | −.07 | .15 | |||

| Subjective sleep quality | −.001(.002) | −.02 | .59 | −.001(.002) | −.02 | .63 | |||

| Chronic Conditions | .000(.002) | −.01 | .77 | .000(.002) | −.01 | .86 | |||

| Anti-diabetic Medication useb | .097(.009) | .45 | <.001 | .097(.009) | .45 | <.001 | |||

| Negative Affect | .001(.002) | −.01 | .84 | ||||||

| Eudaimonic Well-being | |||||||||

| Personal Growth | −.003(.002) | −.10 | .058 | −.001(.002) | −.02 | .65 | −.001(.002) | −.02 | .61 |

| Purpose in Life | −.005(.002) | −.14 | .005 | −.004(.002) | −.10 | .021 | −.004(.002) | −.11 | .018 |

| Ikigaib | −.006(.004) | −.08 | .13 | −.005(.004) | −.06 | .16 | −.005(.004) | −.07 | .16 |

| Hedonic Well-being | |||||||||

| Positive Affect | .001(.002) | .04 | .41 | .002(.002) | .05 | .26 | .002(.002) | .06 | .25 |

| Life Satisfaction | −.001(.001) | −.04 | .45 | −.001(.001) | −.04 | .66 | −.001(.001) | −.02 | .66 |

| Interdependent Well-being | |||||||||

| Gratitude | −.002(.002) | −.05 | .32 | .000(.002) | .00 | .97 | −.000(.002) | .00 | .99 |

| Peaceful Disengagement | .005(.002) | .13 | .009 | .005(.002) | .13 | .003 | .005(.002) | .13 | .003 |

| Adjustment | .001(.002) | .02 | .73 | .000(.002) | .00 | .94 | .000(.002) | .01 | .91 |

Note. HbA1c and alcohol were log10 transformed. All continuous predictor variables are z-scored.

Each psychological well-being variable was entered in a separate model.

1=yes.

As an index of relative effect size, predicted HbA1c values at one standard deviation above and below the mean on the two significant well-being variables were compared to predicted HbA1c values for BMI. Results are graphed in Figure 1. Predicted HbA1c at one standard deviation above the mean on purpose in life was approximately .1% lower than at one standard deviation below the mean. Predicted HbA1c at one standard deviation above the mean on peaceful disengagement was approximately .1% higher than at one standard deviation below the mean. Effects were comparable to BMI.

Figure 1.

Predicted HbA1c values at one standard deviation above and below the mean of purpose in life, perceived disengagement, and BMI in fully-adjusted models (corresponding to Table 2, Model 3).

As shown in Supplemental Table 1, no significant associations were found between well-being and systolic blood pressure, total to HDL cholesterol ratio, or waist circumference (ps >.17), with the exception that individuals who endorsed having ikigai in their life had lower systolic blood pressure in fully adjusted models, (β = −.089, t(309) = 2.00, p = .047). Those who endorsed having ikigai had estimated systolic blood pressure 3.8 mmHg lower than those reporting no ikigai in their lives.

Discussion

Type 2 diabetes is a major public health concern in Japan, which has the fifth largest population of diabetics in the world and rates of type 2 diabetes that are increasing over time (International Diabetes Federation, 2013; Morimoto et al., 2010). As such, understanding the role of psychological factors, as possible risk or protective influences on glucoregulation in Japanese adults, is important work to do, given that such factors have accounted for variation in biological risk factors, including those pertinent to type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, in the United States and Europe. The purpose of the current study was to examine associations between three varieties of psychological well-being and an index of glucoregulation (i.e., HbA1c) among Japanese adults. While associations among psychological resources and glucoregulation were mixed, select outcomes emerged that contribute to the growing body of literature linking psychological resources to objectively-assessed measures of health risk.

A first key finding was that purpose in life was associated with better glucoregulation (i.e., lower HbA1c) among Japanese adults, independent of health factors and negative affect. This finding is in line with prior evidence supporting health protective effects of this construct in Western samples. In prior research, individuals with greater purpose in life prospectively demonstrated reduced risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, metabolic syndrome, cerebral infarcts, Alzheimer disease pathology, and mortality and also increased use of preventative health services (Boehm & Kubzansky, 2012; Boylan & Ryff, 2015; Boyle et al., 2012; Cohen, Bavishi, & Rozanski, 2016; Hill & Turiano, 2014; Kim, Strecher, et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2012, 2013; Ryff, 2014; Yu et al., 2015). Purpose in life has been linked with healthier automatic emotion regulation strategies (Schaefer et al., 2013) and sustained activity in reward circuitry (Heller et al., 2013), which may function as neural mechanisms linking purpose in life to physical health outcomes. Given the specificity of the inverse association between HbA1c to purpose in life, this construct may be ubiquitously protective across a number of physical health domains, and efforts to increase purpose in life, perhaps via volunteering or finding work in retirement (Barron et al., 2009; Greenfield & Marks, 2004; Weiss, Bass, Heimovitz, & Oka, 2005), may yield important physical health benefits across cultural contexts. In contrast to protective findings for mortality in Eastern cultural contexts (Koizumi et al., 2008; Sone et al., 2008; Tanno et al., 2009), we did not find evidence linking ikigai to glucoregulation. This may have stemmed from the limited assessment of ikigai with a yes or no response, although the same measure was linked with reduced systolic blood pressure among Japanese adults.

Although positive affect and life satisfaction (indicators of hedonic well-being) have been shown to predict positive health outcomes in Western samples (Boehm & Kubzansky, 2012; Pressman & Cohen, 2005), we did not expect to see, and did not find, such effects in Japan. East Asians, we noted earlier, are more likely to idealize low arousal positive emotions to high arousal positive emotions (Tsai, 2007). The positive affect scale used in this study included both low (e.g., “calm” and “peaceful”) and high (e.g., “extremely happy”) arousal adjectives, neither of which were significant predictors of HbAlc. Positive emotions are construed differently in Eastern and Western cultures. Dialectical beliefs are more common among East Asians, which involves to attending to negative aspects of positive emotions (Miyamoto & Ryff, 2011; Uchida et al., 2004). Experimental research supports that East Asians are more likely to believe that being too happy has negative consequences, for example (Miyamoto & Ma, 2011). Reflecting such dialectical beliefs, the links between positive emotions and mental and physical health have been shown to be weaker among Asian samples than among Western samples (Lee, Wang, & Koo, 2011), including between MIDJA and MIDUS respondents (Yoo, Miyamoto, Rigotti, & Ryff, 2016). Thus, the lack of association between hedonic well-being and health outcomes in Japan in the present study is in line with these prior findings. Together, the results support that expectations regarding the function of positive emotions and the cultural contexts in which they occur are relevant for understanding linkages to health.

Because well-being in Japan is likely to involve more interdependent aspects of well-being, we included three Eastern assessments of well-being. These included gratitude, adjustment to others, and peaceful disengagement. Only the latter was associated with HbAlc levels, albeit contrary to the direction we had predicted: higher peaceful disengagement was associated with higher, rather than lower, HbA1c levels. Peaceful disengagement is a component of minimalist well-being that reflects separating the self from the constantly changing reality (Kan et al., 2009). Example items include, “I feel free when I spend all my time just for myself” and “I am satisfied with the time to laze away.” As such, disengagement may capture a failure to attend to health concerns and participate in self care, which could contribute to poorer glucoregulation. However, the association remained significant after adjustments for health behaviors and health status factors, such as smoking, healthy eating, sleep, alcohol consumption, and obesity (i.e., BMI), were taken into account, thereby undermining this interpretation. Alternatively, within a highly interdependent culture like Japan, peaceful disengagement may interfere with meeting social obligations and reflect social isolation, which could create other kinds of stress. Considering peaceful disengagement in the context of social responsibilities and resources may be a fruitful direction for future research. Indeed, tangible resources like social status and social relationships have shown to be relevant predictors of health in Japan (Curhan et al., 2014; Murata et al., 2005; Yuasa et al., 2012).

In the present study, having high purpose in life and peaceful disengagement was associated with approximately a 0.1% change in HbA1c from counterparts with low well-being. This effect was comparable to that of BMI, a critically important risk factor for diabetes (Mokdad et al., 2003). Weight loss is a critical cornerstone of successful diabetes prevention and management, and it is the most frequent target of prevention and intervention efforts (Knowler et al., 2002). While the importance of targeting BMI to improve glucoregulation is undisputed, additionally targeting well-being may achieve even greater risk reductions. Intervention efforts have been successful at increasing well-being, including purpose in life but not peaceful disengagement, within a community sample of older adults (Friedman et al., 2015) as well as reducing recurrence of major depression and generalized anxiety disorder within clinical populations (Fava et al., 2004; Ruini & Fava, 2009). The extent to which these efforts may bolster physical health is an important avenue for future research. In addition, whether interventions developed in Western cultures can be effective in other cultural contexts needs to be empirically tested. Some studies have found that interventions that worked in the U.S. (e.g., expressive writing, gratitude) were not effective in Asian cultural contexts (Knowles, Wearing, & Campos, 2011; Layous, Lee, Choi, & Lyubomirsky, 2013). Alternatively, a “kindness" intervention, which fits Asian cultural norms, has been shown to work in Asian cultural contexts (Layous et al., 2013; Otake, Shimai, Tanaka-Matsumi, Otsui, & Fredrickson, 2006). The present study points to a possibility that interventions seeking to foster purpose in life may be effective across both cultural contexts.

Although the primary focus of this inquiry was on well-being predictors of glucoregulation in Japanese adults, associations between well-being and three other markers of cardiovascular risk were examined to facilitate comparisons with previously published research from MIDUS (Boehm et al., 2016; Boylan & Ryff, 2015; Zilioli et al., 2015). The additional outcomes included systolic blood pressure, total to HDL cholesterol ratio, and waist circumference. There was no evidence of associations between the well-being measures and total to HDL cholesterol ratio and waist circumference in MIDJA, in contrast to significant associations between purpose in life and life satisfaction with lipid profiles in the United States. However, Japanese adults endorsing that they have ikigai in their lives had approximately 4 mmHg lower systolic blood pressure than those reporting no ikigai. None of the culture by well-being interactions significantly associated with HbA1c, indicating that there were no cultural differences in the link between well-being and HbA1c. These additional analyses lend further support for the health relevance of purpose in life and its Japanese counterpart ikigai across cultures.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, associations are cross-sectional in nature, and thus it is impossible to discern the direction of causality among well-being and glucoregulation. Only a small proportion of the sample exhibited HbA1c levels within the diabetic range, which weakens the argument that the burden of diabetes could have caused lower well-being. Nonetheless, longitudinal data, which are forthcoming in this sample, will bolster the argument that a psychological profile marked with high well-being predicts physical health. The measure of physical activity was also a limitation, given the important role of this mediating factor in understanding links between positive psychological factors and HbA1c. Additionally, while the exclusive focus on positive psychological factors did not allow us to test whether negative psychological traits and emotions predicted poorer glucoregulation, we were able to compare multiple varieties of well-being, including those developed within Japan, and we view the inclusion of these culturally sensitive measures as a unique strength of the study. Future research needs to investigate associations between negative emotions and HbA1c across cultures, building on accumulating evidence of stronger links between negative affect and anger and markers of health in the United States as compared to Japan (Curhan et al., 2014; Kitayama et al., 2015; Miyamoto et al., 2013). Finally, given the focus on the independent associations among well-being and glucoregulation, key life course or socioeconomic differences were not considered in the present study. Evidence supports that that well-being may change across the life course in Japan (Karasawa et al., 2011), and also that well-being may predict health more strongly among those of lower socioeconomic status (Lachman, Agrigoroaei, Murphy, & Tun, 2010; Morozink, Friedman, Coe, & Ryff, 2010; Turiano, Chapman, Agrigoroaei, Infurna, & Lachman, 2014), which both constitute important directions for future research.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study represents an important test of the generalizability of positive associations among psychological well-being and physical health. A key strength was the examination of multiple dimensions of well-being, including constructs that have shown to be protective in the United States and Western populations (e.g., hedonic and eudaimonic well-being) as well as constructs that were developed within an interdependent cultural context (i.e., ikigai, adjustment, minimalist well-being). Examining various types of well-being simultaneously is necessary to discern their relative associations with health, yet this is rarely done within the same study. A central message from this inquiry is that purpose in life predicts better glucoregulation profiles among Japanese adults, and further, that its Japanese counterpart, ikigai, is associated with lower systolic blood pressure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (5R37AG027343) to conduct a study of Midlife in Japan (MIDJA) for comparative analysis with MIDUS (Midlife in the U.S., P01-AG020166). JMB was supported by a training grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (5T32HL007560-32). VKT is supported by a career development award from the National Institute on Aging (5K01AG041179). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barron JS, Tan EJ, Yu Q, Song M, McGill S, Fried LP. Potential for intensive volunteering to promote the health of older adults in fair health. Journal of Urban Health. 2009;86:641–53. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9353-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastian B, Kuppens P, De Roover K, Diener E. Is valuing positive emotion associated with life satisfaction? Emotion. 2014;14:639–45. doi: 10.1037/a0036466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm JK, Chen Y, Williams DR, Ryff CD, Kubzansky LD. Subjective well-being and cardiometabolic health: an 8–11 year study of midlife adults. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2016;85:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm JK, Kubzansky LD. The heart’s content: The association between positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular health. Psychological Bulletin. 2012;138:655–91. doi: 10.1037/a0027448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boylan JM, Ryff CD. Psychological Well-being and Metabolic Syndrome: Findings from the Midlife in the United States National Sample. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2015;77:548–58. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Wilson RS, Yu L, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Effect of purpose in life on the relation between Alzheimer disease pathologic changes on cognitive function in advanced age. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69:499–505. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw BG, Richardson GE, Kumpfer K, Carlson J, Stanchfield J, Overall J, Kulkarni K. Determining the efficacy of a resiliency training approach in adults with type 2 diabetes. The Diabetes Educator. 2007;33:650–9. doi: 10.1177/0145721707303809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC. How healthy are we: a national study of well-being at midlife. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chida Y, Steptoe A. Positive psychological well-being and mortality: a quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70:741–56. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31818105ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen R, Bavishi C, Rozanski A. Purpose in life and its relationship to all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events: A meta-analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2016;78:122–33. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curhan KB, Levine CS, Markus R, Kitayama S, Park J, Karasawa M, Ryff CD. Subjective and objective hierarchies and their relations to psychological well-being: a U.S./Japan comparison. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2014;5:855–864. doi: 10.1177/1948550614538461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curhan KB, Sims T, Markus HR, Kitayama S, Karasawa M, Kawakami N, Ryff CD. Just how bad negative affect is for your health depends on culture. Psychological Science. 2014;25:2277–80. doi: 10.1177/0956797614543802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Beer JC, Liebenberg L. Does cancer risk increase with HbA1c, independent of diabetes? British Journal of Cancer. 2014;110:2361–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49:71–5. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava GA, Ruini C, Rafanelli C, Finos L, Conti S, Grandi S. Six-year outcome of cognitive behavior therapy for prevention of recurrent depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1872–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.161.10.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman PJ, Steptoe A. Psychosocial and socioeconomic factors associated with glycated hemoglobin in nondiabetic middle-aged men and women. Health Psychology. 2003;22:398–405. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.4.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman EM, Ruini C, Foy R, Jaros L, Sampson H, Ryff CD. Lighten UP! A community-based group intervention to promote psychological well-being in older adults. Aging and Mental Health. 2015 doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1093605. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield EA, Marks NF. Formal volunteering as a protective factor for older adults’ psychological well-being. The Journals of Gerontology Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004;59:S258–64. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.5.s258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller AS, van Reekum CM, Schaefer SM, Lapate RC, Radler BT, Ryff CD, Davidson RJ. Sustained striatal activity predicts eudaimonic well-being and cortisol output. Psychological Science. 2013;24:2191–2200. doi: 10.1177/0956797613490744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill PL, Turiano NA. Purpose in life as a predictor of mortality across adulthood. Psychological Science. 2014;25:1482–6. doi: 10.1177/0956797614531799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infurna FJ, Gerstorf D. Perceived control relates to better functional health and lower cardio-metabolic risk: the mediating role of physical activity. Health Psychology. 2014;33:85–94. doi: 10.1037/a0030208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 6th. Brussels, Belgium: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kan C, Karasawa M, Kitayama S. Minimalist in style: self, identity, and well-being in Japan. Self and Identity. 2009;8:300–317. doi: 10.1080/15298860802505244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karasawa M, Curhan KB, Markus HR, Kitayama S, Love GD, Radler BT, Ryff CD. Cultural perspectives on aging and well-being: a comparison of Japan and the United States. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2011;73:73–98. doi: 10.2190/AG.73.1.d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM. The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2002;43:207–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM, Shmotkin D, Ryff CD. Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:1007–1022. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.82.6.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaw KT, Wareham N, Bingham S, Luben R, Welch A, Day N. Association of hemoglobin A1c with cardiovascular disease and mortality in adults: the European prospective investigation into cancer in Norfolk. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;141:413–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-6-200409210-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ES, Park N, Sun JK, Smith J, Peterson C. Life satisfaction and frequency of doctor visits. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2014;76:86–93. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ES, Strecher VJ, Ryff CD. Purpose in life and use of preventive health care services. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111:16331–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414826111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ES, Sun JK, Park N, Kubzansky LD, Peterson C. Purpose in life and reduced risk of myocardial infarction among older U.S. adults with coronary heart disease: a two-year follow-up. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;36:124–33. doi: 10.1007/s10865-012-9406-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ES, Sun JK, Park N, Peterson C. Purpose in life and reduced stroke in older adults: The Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2013;74:427–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Karasawa M, Curhan KB, Ryff CD, Markus HR. Independence and interdependence predict health and wellbeing: divergent patterns in the United States and Japan. Frontiers in Psychology. 2010;1:163. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Markus HR. The pursuit of happiness and the realization of sympathy: Cultural patterns of self, social relations, and well-being. In: Diener E, Suh EM, editors. Culture and subjective well-being. Cambridge, MA, US: The MIT Press; 2000. pp. 113–161. [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Park J, Boylan JM, Miyamoto Y, Levine CS, Markus HR, Ryff CD. Expression of anger and ill health in two cultures: an examination of inflammation and cardiovascular risk. Psychological Science. 2015;26:211–20. doi: 10.1177/0956797614561268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi M, Ito H, Kaneko Y, Motohashi Y. Effect of having a sense of purpose in life on the risk of death from cardiovascular diseases. Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;18:191–6. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE2007388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles E, Wearing J, Campos B. Culture and the health benefits of expressive writing. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2011;2:408–415. doi: 10.1177/1948550610395780. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Layous K, Lee H, Choi I, Lyubomirsky S. Culture matters when designing a successful happiness-increasing activity: A comparison of the United States and South Korea. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2013;44:1294–1303. doi: 10.1177/0022022113487591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Wang J, Koo K. Are positive emotions just as “positive” across cultures? Emotion. 2011;11:994–995. doi: 10.1037/a0021332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine CS, Miyamoto Y, Markus HR, Rigotti A, Boylan JM, Park J, Ryff CD. Culture and healthy eating: The role of independence and interdependence in the U.S. and Japan. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2016;42:1335–1348. doi: 10.1177/0146167216658645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love GD, Seeman TE, Weinstein M, Ryff CD. Bioindicators in the MIDUS national study: Protocol, measures, sample, and comparative context. Journal of Aging and Health. 2010;22:1059–80. doi: 10.1177/0898264310374355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review. 1991;98:224–253. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Kitayama S. Cultures and selves: a cycle of mutual constitution. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2010;5:420–430. doi: 10.1177/1745691610375557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto Y, Boylan JM, Coe CL, Curhan KB, Levine CS, Markus HR, Ryff CD. Negative emotions predict elevated interleukin-6 in the United States but not in Japan. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2013;34:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.07.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto Y, Ma X. Dampening or savoring positive emotions: a dialectical cultural script guides emotion regulation. Emotion. 2011;11:1346–57. doi: 10.1037/a0025135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto Y, Ryff CD. Cultural differences in the dialectical and non-dialectical emotional styles and their implications for health. Cognition & Emotion. 2011;25:22–39. doi: 10.1080/02699931003612114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, Marks JS. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:76–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto A, Nishimura R, Tajima N. Trends in the epidemiology of patients with diabetes in Japan. Japan Medical Association Journal. 2010;53(1):36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Morozink JA, Friedman EM, Coe CL, Ryff CD. Socioeconomic and psychosocial predictors of interleukin-6 in the MIDUS national sample. Health Psychology. 2010;29:626–35. doi: 10.1037/a0021360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, Kolarz CM. The effect of age on positive and negative affect: a developmental perspective on happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:1333–49. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.5.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata C, Takaaki K, Hori Y, Miyao D, Tamakoshi K, Yatsuya H, Toyoshima H. Effects of social relationships on mortality among the elderly in a Japanese rural area: an 88-month follow-up study. Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;15(3):78–84. doi: 10.2188/jea.15.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otake K, Shimai S, Tanaka-Matsumi J, Otsui K, Fredrickson B. Happy people become happier through kindness: A counting kindnesses intervention. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2006;7(3):361–375. doi: 10.1007/s10902-005-3650-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschalides C, Wearden AJ, Dunkerley R, Bundy C, Davies R, Dickens CM. The associations of anxiety, depression and personal illness representations with glycaemic control and health-related quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2004;57:557–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pressman SD, Cohen S. Does positive affect influence health? Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:925–71. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radler BT, Ryff CD. Who participates? Accounting for longitudinal retention in the MIDUS national study of health and well-being. Journal of Aging and Health. 2010;22:307–31. doi: 10.1177/0898264309358617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruini C, Fava GA. Well-being therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65:510–9. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:141–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57:1069–1081. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.57.6.1069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Keyes CLM. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:719–27. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Kitayama S, Karasawa M, Markus H, Kawakami N, Coe C. Survey of Midlife Development in Japan (MIDJA 2); May–October 2012; Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2016. May 07, ICPSR36427-v2. http://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36427.v2. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Love GD, Miyamoto Y, Markus HR, Curhan KB, Kitayama S, Karasawa M. Culture and the promotion of well-being in the East and West: Understanding varieties of attunement to the surrounding context. In: Fava GA, Ruini C, editors. Increasing Psychological Well-being in Clinical and Educational Settings: Interventions and Cultural Contexts. Vol. 8. New York: Springer; 2014. pp. 1–19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Love GD, Urry HL, Muller D, Rosenkranz MA, Friedman EM, Singer B. Psychological well-being and ill-being: do they have distinct or mirrored biological correlates? Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2006;75:85–95. doi: 10.1159/000090892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer SM, Boylan JM, van Reekum CM, Lapate RC, Norris CJ, Ryff CD, Davidson RJ. Purpose in life predicts better emotional recovery from negative stimuli. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e80329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sone T, Nakaya N, Ohmori K, Shimazu T, Higashiguchi M, Kakizaki M, Tsuji I. Sense of life worth living (ikigai) and mortality in Japan: Ohsaki Study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70:709–15. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817e7e64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanno K, Sakata K, Ohsawa M, Onoda T, Itai K, Yaegashi Y, Tamakoshi A. Associations of ikigai as a positive psychological factor with all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality among middle-aged and elderly Japanese people: findings from the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2009;67:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL. Ideal affect: cultural causes and behavioral consequences. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2007;2:242–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsenkova VK, Love GD, Singer BH, Ryff CD. Socioeconomic status and psychological well-being predict cross-time change in glycosylated hemoglobin in older women without diabetes. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69:777–84. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318157466f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida Y, Norasakkunkit V, Kitayama S. Cultural constructions of happiness: theory and empirical evidence. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2004;5:223–239. doi: 10.1007/s10902-004-8785-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dieren S, Beulens JWJ, van der Schouw YT, Grobbee DE, Neal B. The global burden of diabetes and its complications: an emerging pandemic. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. 2010;17:S3–8. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000368191.86614.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RS, Bass SA, Heimovitz HK, Oka M. Japan’s silver human resource centers and participant well-being. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 2005;20:47–66. doi: 10.1007/s10823-005-3797-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo J, Miyamoto Y, Rigotti A, Ryff C. Linking positive affect to blood lipids: A cultural perspective. University of Wisconsin-Madison; 2016. Unpublished manuscript. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Levine SR, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Purpose in life and cerebral infarcts in community-dwelling older people. Stroke. 2015;46:1071–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.008010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuasa M, Hoshi T, Hasegawa T, Nakayama N, Takahashi T, Kurimori S, Sakurai N. Causal relationships between physical, mental and social health-related factors among the Japanese elderly: A chronological study. Health. 2012;04:133–142. doi: 10.4236/health.2012.43021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zilioli S, Slatcher RB, Ong AD, Gruenewald TL. Purpose in life predicts allostatic load ten years later. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2015;79:451–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.