Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by brain deposition of amyloid plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles along with steady cognitive decline. Synaptic damage, an early pathological event, correlates strongly with cognitive deficits and memory loss. Mitochondria are essential organelles for synaptic function. Neurons utilize specialized mechanisms to drive mitochondrial trafficking to synapses in which mitochondria buffer Ca2+ and serve as local energy sources by supplying ATP to sustain neurotransmitter release. Mitochondrial abnormalities are one of the earliest and prominent features in AD patient brains. Amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau both trigger mitochondrial alterations. Accumulating evidence suggests that mitochondrial perturbation acts as a key factor that is involved in synaptic failure and degeneration in AD. The importance of mitochondria in supporting synaptic function has made them a promising target of new therapeutic strategy for AD. Here, we review the molecular mechanisms regulating mitochondrial function at synapses, highlight recent findings on the disturbance of mitochondrial dynamics and transport in AD, and discuss how these alterations impact synaptic vesicle release and thus contribute to synaptic pathology associated with AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid-β, ATP supply, axonal transport, mitochondrial trafficking, neurotransmitter, oxidative stress, synaptic pathology, synaptic vesicle release, tau

INTRODUCTION

Neurons have high and continuous energy demands in order to maintain their proper function. Since the brain accounts for 20% of total body oxygen consumption, brief periods of deprivation of oxygen or glucose will lead to neuronal death. Neurons have limited glycolytic capacity and rely highly on aerobic oxidative phosphorylation to meet their energetic requirements. Mitochondria are the principal producers of cellular energy, and thus are crucial for neuronal function and survival. Mitochondrial ATP production sustains various essential functions at synapses such as: 1) maintaining ion gradients across the cellular membrane, which is required for axonal and synaptic membrane potentials [1]; 2) mobilizing synaptic vesicles from reserve pools to release sites [2]; 3) supporting synaptic vesicle release and recycling [3–5]; 4) supporting synaptic assembly and plasticity [6, 7].

Besides energy production, mitochondria have a high capacity to sequester and buffer intracellular Ca2+ levels. At synaptic terminals, mitochondria take up excess intracellular Ca2+ and release Ca2+ to prolong the residual Ca2+ levels [8, 9]. Through this mechanism, synaptic mitochondria appear to be involved in maintaining and regulating neurotransmission [10, 11], or certain types of short-term synaptic plasticity [12, 13]. Synaptic mechanisms are thought to be Ca2+–dependent processes, which can be interrupted by defects in mitochondria-mediated Ca2+ buffering. Damaged mitochondria not only function inefficiently for supplying ATP and buffering Ca2+, but also release reactive oxygen species (ROS) [14–16]. As a result, mitochondrial oxidative stress triggers leakage of mitochondrial intermembranous contents, such as cytochrome c, into the cytosol, which results in caspase activation, DNA damage, and apoptosis [17]. The progressive accumulation of these defective mitochondria in axons and synapses over the lifetime of neurons could lead to synaptic dysfunction and neuronal pathology.

The main neuropathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are the accumulation of extracellular senile plaques, the presence of intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFT), altered neuronal connectivity, and massive neuron loss. Synaptic dysfunction and impaired neuronal communication occur earlier during the preclinical stage of AD and before the emergence of these pathology features. While AD brain biopsy showed an abnormal glucose metabolism [18], using positron emission tomography (PET), results from several studies indicate that reduced glucose metabolism is an early occurrence in the course of AD development [19–21]. Given that mitochondria play a critical role in brain metabolism and function, mitochondrial perturbation may contribute significantly to early AD pathophysiology. Undeniably, aberrant accumulation of damaged mitochondria has been shown as a prominent feature in both familial and sporadic AD [22, 23]. Here, we provide an overview of the underlying mechanisms regulating mitochondrial function as well as the trafficking and distributions of mitochondria to synapses, and discuss how abnormalities in these mechanisms compromise neurotransmission, and thus contribute to synaptic pathology in AD.

AN OVERVIEW OF MITOCHONDRIA

Mitochondria are crucial for the maintenance of neuronal integrity and responsiveness, as well as neurotransmission, especially fast neurotransmission [15, 24]. The key function of mitochondria is to produce ATP through the coupling of oxidative phosphorylation with cellular respiration. Mitochondrial respiratory chain consists of five enzyme complexes: NADH-CoQ reductase (complex I), succinate CoQ reductase (complex II), ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase (complex III), cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV), and F1Fo-ATP synthase (complex V). The respiratory enzyme complexes transfer electrons to each other and ultimately to O2. Complex I, III, and IV translocate protons across the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) to create a proton gradient. This proton gradient drives complex V to synthesize ATP, thereby completing the process of oxidative phosphorylation [25]. An important aspect of mitochondrial electron transport chain is the generation of ROS–a physiological by-product of respiration. Since mitochondria consume approximately 85% of total oxygen used by cells, they represent the major source of intracellular ROS [26, 27]. Mitochondria are subjected to direct attack of these reactive species, and therefore are particularly susceptible to oxidative damage.

Mitochondria play a crucial role in the maintenance of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis because they can take up substantial amounts of cytosolic Ca2+. In the brain, the mitochondrial calcium uniporter, a highly selective ion channel, mediates Ca2+ uptake [28]. On the other hand, mitochondria can release Ca2+ through the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP), which is a large conductance channel composed of voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) in the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM), adenine nucleotide transporter in the IMM, and cyclophilin D (CypD). CypD, a peptidylprolyl isomerase F, localizes in the mitochondrial matrix and associates with the IMM during the MPTP opening. Cellular stresses promote the translocation of CypD to the IMM, a key event in the MPTP opening [29–31]. When MPTP is opened, it allows the release of Ca2+ from the matrix, leading to mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) dissipation, osmotic swelling, and the OMM rupture [32–35]. Severe damage of mitochondria may result in cell death by: 1) disrupting electron transport and energy metabolism; 2) releasing pro-apoptotic factors to activate the caspase family proteases; 3) altering cellular reduction-oxidation (redox) potential [35–37]. One of the main events of mitochondria-mediated apoptosis is the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria to the cytosol, the consequence of mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization. Cytochrome c participates in the activation of caspases to orchestrate the biochemical execution of cell death [38, 39]. This process has been linked to neuron loss in a variety of neurodegenerative disorders including AD.

MOLECULAR MECHANISMS REGULATING MITOCHONDRIAL TRAFFICKING AT SYNAPSES

Neurons are highly polarized cells and consist of a cell body, several short and thick dendrites, and a long, thin axon. These distinct structural and functional domains have very different metabolic demands and display a non-uniform distribution pattern of mitochondria [15, 40]. Synaptic terminals contain more mitochondria than other cellular regions of neurons, where they power neurotransmission by producing ATP and buffering Ca2+ [41, 42]. Loss of mitochondria from these regions inhibits synaptic transmission due to insufficient ATP supply or altered Ca2+ dynamics during intensive synaptic activity.

Efficient mitochondrial transport is essential for recruiting and redistributing mitochondria to specific domains with high-energy demands, such as synaptic terminals, which serve as a crucial mechanism regulating mitochondrial density at synapses. Mitochondria in neurons undergo bidirectional movement along neuronal processes, thus changing their localization dynamically [13, 43]. In mature neurons, one-third of axonal mitochondria are motile. They move, stop, and move again or pause or switch to constant docking state [13]. Long-distance axonal transport of mitochondria is supported by microtubules and motor proteins [15]. The kinesin-1 family (KIF5) is the major motor for driving anterograde transport of mitochondria in axons [44–48]. As a KIF5 motor adaptor, Drosophila protein Milton enables KIF5 motors to attach to mitochondria by binding to both the KIF5 C-terminal tail domain and the mitochondrial outer membrane receptor Miro [49, 50]. Mutation of Milton in Drosophila reduces axonal transport of mitochondria to synapses and impairs synaptic transmission [49]. In mammals, there are two Milton orthologues, Trak1 and Trak2 [51–53]. While overexpression of Trak2 robustly enhances mitochondrial motility [54], loss of Trak1 or expression of its mutants leads to reduced axonal transport of mitochondria [55].

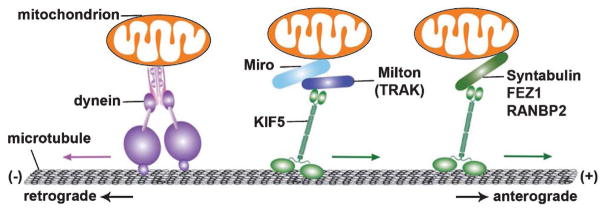

Miro, a Rho-GTPase on the mitochondrial outer membrane, consists of two Ca2+-binding EF-hand motifs and two GTPase domains and binds to Trak/Milton [56, 57]. Miro mutation in Drosophila depletes the supply of mitochondria in synaptic terminals due to impaired mitochondrial transport [58]. Miro1 and Miro2 are two isoforms in mammals. The Miro1-Trak2 adaptor complex was shown to regulate mitochondrial trafficking [51]. Elevated Miro1 expression increased mitochondrial motility, likely by recruiting more Trak2 and KIF5 motors to mitochondria [54]. Thus, KIF5, Milton (Trak), and Miro seem to be assembled into the transport machinery that drives anterograde transport of axonal mitochondria. In addition, a number of other proteins have been proposed as KIF5 motor adaptor candidates for driving mitochondrial transport, including syntabulin, FEZ1 (fasciculation and elongation protein zeta-1), and RAN-binding protein 2 [46, 59, 60] (Fig. 1). The existence of multiple motor adaptors suggests a complex mechanism through which mitochondrial motility is regulated in response to various physiological and pathological conditions.

Fig. 1.

Microtubule-based axonal transport of mitochondria. The Kinesin-1 motor family KIF5 participates in anterograde axonal transport to the plus end of microtubules, and selectively moves mitochondria from the soma to axonal terminals. Conversely, cytoplasmic dynein motors, the minus end-driven motors, carry out retrograde transport of axonal mitochondria. The Miro-Milton (or Miro-Trak) adaptor complex is involved in KIF5-mediated mitochondrial transport. Miro, a mitochondrial outer membrane protein, belongs to the Rho GTPase family. By binding to Miro, Milton recruits KIF5 to mitochondria and enables its anterograde transport in Drosophila neurons. Trak1 and Trak2, mammalian orthologues of Milton, interact with Miro1 and Miro2 (mammalian Miro orthologues). The Miro1-Trak2 complex has been shown as an important regulator of mitochondrial transport in hippocampal neurons. KIF5 was also reported to mediate anterograde transport of axonal mitochondria via syntabulin, a KIF5 adaptor that binds to mitochondria through its carboxy-terminal transmembrane domain. Fasciculation and elongation protein zeta-1 (FEZ1), as well as RAN-binding protein 2 (RANBP2), are additional KIF5 adaptors that may regulate mitochondrial transport. Figure is modified from [16].

Cytoplasmic dynein motors mediate retrograde transport of axonal mitochondria to the soma in neurons. The dynein motors are composed of multiple subunits, including heavy chains (the head domain of motor protein for force production), and intermediate, light intermediate, and light chains that function in the regulation of cargo attachment and motility. Miro, the KIF5 motor adaptor, was also reported to serve as an adaptor for dynein motors in Drosophila [58, 61]. Thus, loss of Drosophila Miro impairs both kinesin-and dynein-mediated transport. Conversely, overexpression of Miro enhances mitochondrial motility in both directions.

Mitochondrial transport and distribution are highly correlated with changes in the local energy state and metabolic demand, and they can be actively regulated upon synaptic activation. Mitochondria are recruited to synapses in response to the elevation of intracellular Ca2+ levels during sustained synaptic activity. Elevated Ca2+ influx, either by activating voltage-dependent calcium channels or NMDA receptors, arrests mitochondrial movement [62–66]. This mechanism facilitates the recruitment of mitochondria to synapses. Several studies proposed that immobilization of mitochondria at synaptic terminals occurs through the Miro-Ca2+-sensing pathway [54, 67–69].

Proper synaptic function requires stationary mitochondria to dock in regions where energy is in high demand because the diffusion capacity of intracellular ATP is rather limited [70]. Docked mitochondria ideally serve as stationary power plants for stable and continuous ATP supply, which is necessary to maintain the activity of Na+–K+ ATPase, fast spike propagation, and neurotransmission. Moreover, mitochondria docked at synapses are required for sequestering intracellular Ca2+ to maintain Ca2+ homeostasis upon synaptic activation [10, 13]. In response to synaptic activity, besides elevated Ca2+ influx-induced mitochondrial immobilization, the mechanism underlying microtubule-based docking is crucial for maintaining proper homeostatic mitochondrial density at synapses. Syntaphilin, a mitochondria-anchoring protein, plays a critical role in docking mitochondria specifically in distal axons and synaptic terminals [13, 71]. It targets axonal mitochondria through its C-terminal mitochondria-targeting domain and axon-sorting sequence, and immobilizes mitochondria by anchoring to microtubules. Deleting syntaphilin results in a robust increase of axonal mitochondria in motile pools and leads to reduced mitochondrial density at presynaptic sites. Conversely, overexpressing syntaphilin abolishes mitochondrial transport in axons. Thus, syntaphilin-mediated mitochondrial anchoring acts as another important mechanism in recruiting motile mitochondria into activated synapses and maintaining proper mitochondrial distribution at presynaptic terminals to support synaptic vesicle release.

REGULATION OF SYNAPTIC ACTIVITY THROUGH MITOCHONDRIAL TRAFFICKING

Stationary mitochondria within presynaptic terminals provide stable and continuous ATP supply and maintain Ca2+ homeostasis. In contrast, motile mitochondria passing through presynaptic boutons dynamically alter local ATP levels and contribute to presynaptic variation. Dynamic mitochondrial trafficking impacts on many ATP-dependent processes at synaptic terminals, including the generation of the proton gradient, which is necessary for vesicle neurotransmitter loading; the removal of Ca2+ from nerve terminals by the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger; and myosin motor-mediated transport of reserve pool synaptic vesicles to release sites. Inhibition of mitochondrial transport results in loss of mitochondria from synaptic sites, thus impairing neurotransmitter release. Defective mitochondrial trafficking to synapses leads to impaired synaptic transmission in Drosophila photoreceptors that express mutant Milton [49]. Mutation of Drosophila Drp1, the mitochondrial fission protein, showed faster depletion of synaptic vesicles during prolonged stimulation due to loss of synaptic mitochondria. Interestingly, the addition of ATP to terminals partially rescues these defects [2]. Consistently, it was reported that reduced mitochondrial trafficking to axonal terminals due to Syntabulin loss of function accelerates synaptic depression and slows the rate of synapse recovery after the depletion of synaptic vesicles during high-frequency firing. These defects can be reversed by the application of ATP to presynaptic neurons [72]. These findings suggest that ATP production by synaptic mitochondria is required for supporting intense synaptic activity.

Mitochondrial motility at axonal terminals was recently shown to contribute to pulse-to-pulse variability of presynaptic strength at single-bouton levels [3]. Enhanced axonal mitochondrial motility increases the pulse-to-pulse variability of excitatory postsynaptic current amplitudes. Interestingly, the variability is diminished if axonal mitochondria are immobilized. More importantly, mitochondrial trafficking, into or out of presynaptic boutons, significantly influences synaptic vesicle release due to the fluctuation of synaptic ATP levels. Synaptic terminals in the absence of mitochondria have no constant on-site supply of ATP. A mitochondrion passing by these synapses could temporally supply ATP, thus altering synaptic ATP levels and affecting ATP-dependent processes such as synaptic vesicle mobilization, release, and replenishment (Fig. 2). Consistently, recent study reported that synaptic activity drives large ATP consumption at nerve terminals and synaptic vesicle cycling consumes most presynaptic ATP [4]. Thus, it is possible that all of these ATP-dependent processes collectively contribute to presynaptic variability. Motile mitochondria may supply sufficient ATP for basal synaptic transmission. However, this may not be sufficient for intense and prolonged synaptic activity, and higher levels of ATP supplied by synaptically stationary mitochondria may be required.

Fig. 2.

Regulation of neurotransmitter release through synaptic ATP supply and mitochondrial trafficking. Presynaptic terminals, in the presence of a mitochondrion, powers neurotransmission by stable and continuous ATP supply (left). By contrast, in the absence of a mitochondrion within a presynaptic bouton (right), there is no stable on-site ATP supply, leading to reduced neurotransmitter release. Moreover, when a motile mitochondrion passes through this bouton, it temporally supplies ATP, resulting in the changes of synaptic energy levels and ATP-dependent synaptic activity. The fluctuation of synaptic energy levels occurs over time when mitochondrial motility and distribution are altered. The dynamic mitochondrial trafficking is one of the primary mechanisms underlying the wide variability of synaptic vesicle release [3]. Therefore, the probability of neurotransmitter release is tightly correlated with the levels of synaptic ATP supplied by mitochondria, which could be strongly influenced by mitochondrial trafficking to synapses. Figure is modified from [24].

Neurotransmitter release is triggered by Ca2+ influx through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Mitochondria can influence the probability of synaptic vesicle release through regulating presynaptic Ca2+ transients. Mitochondria were found to rapidly sequester substantial quantities of cytoplasmic Ca2+ and subsequently influence neurotransmitter release on the millisecond timescale at the calyx of Held (a well-characterized glutamatergic synapse) [10]. This observation suggests that mitochondria can regulate short-term presynaptic plasticity by buffering Ca2+ levels. Lack of presynaptic mitochondria at neuromuscular junctions in Drosophila Miro mutants was shown to impair both Ca2+ buffering and neurotransmitter release during prolonged stimulation, due to reduced mitochondrial transport [58]. Using the syntaphilin-deficient mice, one study provided genetic and cellular evidence that changes in axonal mitochondrial motility through disruption of syntaphilin-mediated docking can affect short-term presynaptic plasticity through altering presynaptic Ca2+ dynamics during intense and prolonged stimulation [13]. This study suggests that intracellular Ca2+ may rapidly build up in presynaptic terminals during intense stimulation and that stationary mitochondria within synaptic terminals are able to sequester this Ca2+ most effectively.

MITOCHONDRIAL ABNORMALITIES IN AD

Mitochondrial deficiency has been suggested to be a hallmark of AD as the patients display early metabolic changes prior to the emergence of any histopathological or clinical abnormalities [73]. AD patient brains show an increased in the utilization of oxygen, rather than glucose, suggesting that defects in the respiratory chain of mitochondria may be involved in AD neurodegeneration. A number of positive emission tomography scan studies revealed reduced glucose metabolism in AD patient brains. ApoE4 genotype is positively correlated with defective glucose utilization in the brains from AD patients [74, 75]. Multiple lines of evidence suggest that mitochondrial defects play a key role in the early stage of AD disease progression. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction are important features reported in AD postmortem brains. Many studies found increased free radical production, lipid peroxidation, oxidative protein damage, decreased ATP production, and reduced cell viability in postmortem AD brains [76–84]. In AD patient brains, the levels of cytochrome c oxidase [77, 85–88], pyruvate dehydrogenase [89], and α-ketodehydrogenase [90, 91] are markedly reduced.

In addition, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) changes are greater in postmortem brains from AD patients and aged-matched control subjects than from young and healthy subjects, suggesting age-related accumulation of mtDNA in AD pathogenesis [92, 93]. MtDNA mutations may also be responsible for neuropathological changes observed in AD [94]. Postmortem brains from AD show increased mtDNA mutations and decreased mtDNA copy number. MtDNA mutations are positively correlated with β-secretase activity, whereas the copy number of mtDNA is inversely correlated with the levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42. Moreover, aging and age-dependent accumulation of mtDNA trigger mitochondrial ROS production in neurons, which activates β- and γ-secretases and thus augments amyloid-β protein precursor (AβPP) amyloidogenic processing. The cleaved AβPP products further induce free radicals, which disrupts the electron transport chain, enzyme activities, oxidized DNA and protein, and lipid peroxidation, and thus inhibits mitochondrial ATP production [95, 96]. Therefore, this forms a feedback loop of age-dependent free radicals to Aβ and Aβ to free radicals, ultimately leading to neuronal damage, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in late-onset AD patients. Several studies have shown that mitochondria-encoded genes abnormally expressed in postmortem AD brains compared to the brains of non-demented, healthy subjects [81, 97–99], suggesting impaired mitochondrial metabolism is a characteristic feature of AD patients. Upregulation of mitochondrial genes may be a compensatory response to mitochondrial dysfunction caused by mutant AβPP and Aβ. The involvement of mitochondria in AD pathogenesis has also been demonstrated in cell lines expressing mutant AβPP and/or cells treated with Aβ peptides, and in transgenic AD mouse models [96].

Mitochondrial alterations at ultrastructural level were first demonstrated in a systematic study in the pyramidal neurons of AD patient brains [78]. In AD brains, mitochondria are aberrantly accumulated with reduced size and broken internal membrane cristae [78, 100–102]. Recent studies in postmortem brains from AD patients also revealed alterations in mitochondrial dynamics and transport [103]. Moreover, a growing body of evidence suggests that AβPP and Aβ accumulation plays a central role in mediating mitochondrial toxicity. It has been shown that mitochondrial dysfunction results from the accumulation of AβPP in the mitochondrial import pores in late onset AD brains [79, 104]. AβPP695 targets mitochondria in a transmembrane arrested orientation in human cortical neuronal cells (HCN-1A). Progressive accumulation of AβPP in mitochondria is correlated with reduced complex IV activity and respiration-coupled ATP synthesis, thus leading to collapsed Δψm and a decline in total cellular ATP levels. Transgenic (Tg) 2576 mice, which overexpress human AβPP gene harboring the Swedish mutation (AβPPswe), exhibit high levels of mitochondria-associated AβPP in the cortex and hippocampus. Consistently, accumulation of AβPP within mitochondria in these regions is coupled with decreases in complex IV activity and cellular ATP levels [104]. Elevated AβPP levels in mitochondrial fractions have also been detected in postmortem human AD brains. Mitochondrial AβPP orients with its C-terminal outward and the N-terminal inward. AβPP was shown to interact directly with the import channel proteins Tom40 (translocase of the OMM 40) and Tim23 (translocase of the IMM 23). By forming a high-molecular weight and stable complex, AβPP accumulates across the import channel and blocks the entry of nuclear-encoded protein into mitochondria, thereby affecting their function [79].

The degree of cognitive impairment in AD brains has also been linked to the extent of mitochondrial accumulation of Aβ [105]. Aβ was found to impair mitochondrial function [106–108] and can affect multiple aspects of mitochondria including function of the electron transport chain [109], ROS production [110–112], mitochondrial dynamics [82, 109, 113, 114], and mitochondrial motility [115–117] (Fig. 3). Studies have demonstrated the possible routes for Aβ entry into mitochondria through mitochondrial-associated endoplasmic reticulum membrane or the TOM complex [118, 119]. Extracellular Aβ can also be internalized and taken up by mitochondria [118, 120]. Consistently, dystrophic and fragmented mitochondria were reported to be limited to the vicinity of Aβ plaques in a live AD mouse model. This suggests that amyloid plaques likely serve as focal sources that promote mitochondrial Aβ accumulation and thus Aβ-linked mitochondrial toxicity [121]. Moreover, mitochondrial matrix proteins ABAD and CypD have been shown to interact with Aβ, which was suggested to mediate Aβ-induced cytotoxic effects [107, 108]. Aβ forms a complex with CypD in the cortical regions of postmortem human AD brains and an AD mouse model [108]. Deletion of CypD in AD mice rescues the mitochondrial phenotypes including impaired uptake of Ca2+, mitochondrial swelling as a result of increased Ca2+, depolarized Δψm, elevated oxidative stress, decrease in ADP-induced respiration control rate, and reduced complex IV activity and ATP levels. These findings suggest Aβ-CypD interaction likely mediates AD-associated mitochondrial pathology. Altogether, these pieces of evidence indicate that the aberrant accumulation of AβPP and Aβ within the mitochondrial compartment likely has a causative role in mitochondrial impairment.

Fig. 3.

Effects of Aβ and pathogenic tau on mitochondria. Both Aβ and pathogenic forms of tau induce mitochondrial disturbance, leading to increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), decreased ATP production, and impaired Ca2+ buffering. Aβ and tau-mediated impairments of mitochondrial dynamics and axonal transport trigger the deprivation of mitochondria from presynaptic terminals, which collectively contributes to defects in synaptic vesicle release in AD neurons.

ALTERATIONS OF SYNAPTIC MITOCHONDRIA IN AD

Synapses are sites of high-energy demand and extensive Ca2+ fluctuations, so synaptic mitochondria play a pivotal role in sustaining synaptic activity. Synaptic stress is an early pathological feature of AD. Synaptic mitochondrial dysfunction has been proposed as a key player in synaptic failure in AD. Aβ and Aβ-associated cellular changes are important causative factors underlying neuronal perturbation and synaptic distress in AD. Synaptic mitochondria are an early target of Aβ, leading to early pathological changes before global brain mitochondrial damage can be detected. Synaptic mitochondria are more vulnerable to cumulative changes induced by deleterious factors such as Aβ. One study showed that incubation of synaptosomes purified from rat brains with Aβ25–35 altered the ultrastructure of synaptosomes, along with swollen synaptic mitochondria [122]. By treating synaptosomes with Aβ1–40, another study reported a marked disturbance in synaptic mitochondria, such as Δψm collapse, overloaded mitochondrial Ca2+, and increased free radical production [123]. These studies raise the possibility that Aβ potentially impacts on synaptic mitochondrial properties and thus, synaptic function.

Synaptic mitochondria were shown to display an early and significant accumulation of Aβ in a young AD mouse model before the extensive extracellular Aβ deposition [116]. These mitochondria underwent declines in respiration, complex IV activity, and Ca2+ handling capacity, elevated ROS production, and enhanced probability of MPTP. Functional alterations in synaptic mitochondria occurred before the impairment of non-synaptic mitochondria in this AD model. Synaptic mitochondria displayed more prominent increase in Aβ levels and more profound changes in function in comparison with non-synaptic mitochondria. This study suggests that synaptic mitochondria are more susceptible to Aβ-induced damage and synaptic mitochondrial stress is an early pathological alteration in AD. Another study reported that mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis is responsible for the local activation of caspase-3 in hippocampal dendritic spines of Tg2576 mice, leading to early synaptic dysfunction and dendritic spine loss [124]. Collectively, these results indicate that synaptic mitochondrial disturbance is an early pathological event in the progress of AD. As a key player in Aβ-mediated mitochondrial and neuronal toxicity, synaptic mitochondrial dysfunction contributes significantly to early synaptic deficits in AD.

CHANGES IN SYNAPTIC MITOCHONDRIAL TRAFFICKING IN AD

Mitochondrial trafficking to synapses relies heavily on efficient axonal transport, which is essential for the maintenance of proper synaptic mitochondrial density in order to sustain synaptic activity. Apart from docked stationary mitochondria at synapses, the presence of motile mitochondria at presynaptic sites can also influence synaptic vesicle release [3]. Impaired axonal transport plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of AD [125]. In AD patient brains, axonal degeneration is featured with swollen regions accumulated with organelles including mitochondria [126]. It was reported that presenilin 1 (PS1) mutations impair kinesin-1 based axonal transport and lead to reduced densities of AβPP, synaptic vesicles, and mitochondria in the neuronal processes of hippocampal neurons and sciatic nerves from mutant PS1 knock-in mice [127]. Thus, these studies indicate that impaired axonal transport may compromise synaptic transmission both directly by reducing synaptic mitochondrial density, and indirectly by interfering with mitochondrial trafficking passing through AD synapses.

Mitochondrial fusion and fission are essential for the maintenance of mitochondrial shape and integrity [128–130]. Defects in either mitochondrial fusion or fission can also lead to impaired mitochondrial motility and distribution in neurons, resulting in reduced mitochondrial content in distal neurites [131–133]. Mitochondrial fusion in mammals is mainly mediated by three proteins: Mfn1, Mfn2, and OPA1 [17, 134]. Mitochondrial fission in mammals requires Drp1, a dynamin-like protein [128–130]. Defects in mitochondrial fission result in the accumulation of mitochondria in the cell body and reduced dendritic and synaptic mitochondrial content [6]. Alterations in mitochondrial morphology, particularly fragmented mitochondria, were found in fibroblasts from sporadic AD patients and AD patient brains [135, 136]. Increased levels of Drp1 and Fis1 and reduced expression of Mfn1, Mfn2, and OPA1 were also detected in AD patient brains. In addition, increased Aβ production and the interactions of Drp1 with Aβ and phosphorylated tau augment abnormal mitochondrial fragmentation. These abnormal interactions are increased as AD progresses [82, 114, 129, 130]. Therefore, altered balance in mitochondrial fusion and fission in AD neurons likely interferes with mitochondrial motility, thereby compromising mitochondrial trafficking and distribution in distal axons and synaptic terminals.

Exposure of cultured neurons to Aβ or Aβ-derived diffusible ligands (ADDLs) consistently impaired mitochondrial motility and reduced mitochondrial distribution in axons [115, 116, 137, 138]. Overexpression of Aβ in Drosophila was shown to deplete presynaptic mitochondria by slowing down axonal transport, leading to presynaptic dysfunction [139]. Primary neurons derived from AβPP Tg mice also exhibited impaired anterograde transport of axonal mitochondria, mitochondrial dysfunction, and synaptic deficiency, which are all attributed to the accumulation of oligomeric Aβ within mitochondria [117]. It was reported that Aβ oligomers induce a rapid and sustained increase in intracellular Ca2+ in neurons [140, 141], which may indirectly impact mitochondrial transport. Multiple mechanisms underlying Aβ-induced increase of intracellular Ca2+ have been proposed, which include activations of L-type and P/Q-type voltage-sensitive calcium channels, glutamate receptors such as N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor and AMPA receptor, and ryanodine receptor channels [142–146]. Such synaptic activity-elevated Ca2+ influx can effectively arrest mitochondrial movement by either inactivating or disassembling the KIF5-Miro-Trak transport machineries [54, 67–69].

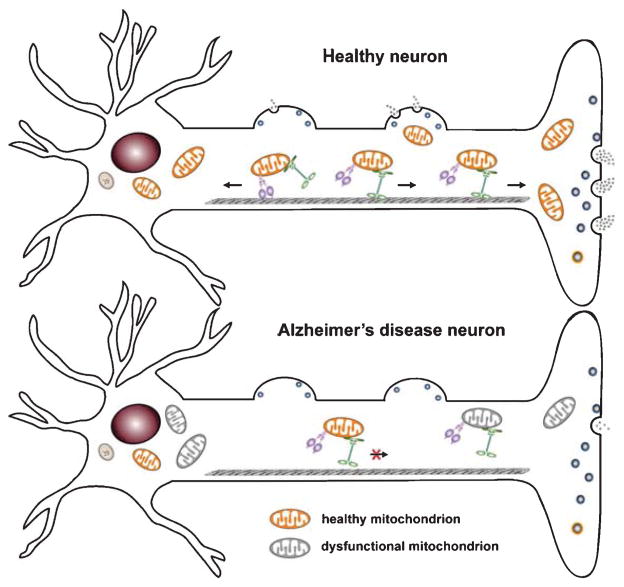

Induction of mitophagy, a selective autophagy pathway for the removal of damaged mitochondria, is associated with alterations in mitochondrial motility. Parkin-mediated mitophagy is accompanied by reduced anterograde mitochondrial transport due to degradation of Miro [147–152]. Our recent study showed that mitophagy is robustly induced in AD neurons of mouse models and patient brains. As a result, these neurons display reduced anterograde transport and increased retrograde transport of axonal mitochondria, which may lead to reduced mitochondrial distribution at synaptic terminals [153]. However, there is no report showing altered expression of Miro in AD patient brains and AD-linked mouse models. Together, altered axonal transport and reduced mitochondrial density in distal axons and at synapses may cause local energy depletion and toxic changes in Ca2+ buffering, thus triggering impaired synaptic vesicle release and synaptic distress in the pathogenesis of AD (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Mitochondrial mechanisms underlying synaptic failure in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). A) Neurons have complex structure features and use specialized mechanisms to drive mitochondrial transport to their distal destinations where metabolic and calcium homeostatic capacity is in a high demand. KIF5 motors are responsible for anterograde transport to distal axonal terminals, whereas dynein motors return mitochondria to the soma. Axonal transport is essential for maintaining mitochondrial density at synapses in order to sustain neurotransmitter release. B) In AD neurons, both Aβ and tau pathology trigger functional alterations of mitochondria, which impair synaptic vesicle release due to insufficient synaptic ATP supply and compromised Ca2+ buffering capacity. Moreover, Aβ and tau-induced disruption of mitochondrial motility reduces mitochondrial trafficking to synapses, thus depriving mitochondria from synapses and exacerbating synaptic pathology.

TAU-MEDIATED MITOCHONDRIAL DISTURBANCE IN SYNAPTIC DYSFUNCTION

Recent research proposes an emerging role for tau in regulating synaptic activity by influencing mitochondrial function and axonal transport. Pathological changes in tau can induce mitochondrial damage, resulting in synaptic dysfunction. Several studies provided evidence that hyperphosphorylated tau specifically impairs complex I of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, thus leading to increased ROS levels, lipid peroxidation, decreased activities of detoxifying enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), and Δψm dissipation [154, 155] (Fig. 3). Overexpression of the P301L mutant human tau protein was reported to decrease ATP levels and increase susceptibility to oxidative stress in cultured neuroblastoma cells [156]. Disrupted activity and altered composition of mitochondrial enzymes were detected in the P301S mouse model of tauopathy [157]. In the pR5 mice overexpressing the P301L tau, mitochondrial dysfunction was found to be associated with a reduced complex I activity, impaired mitochondrial respiration and ATP synthesis, and an increase in ROS levels [158, 159]. Moreover, phosphorylated tau was shown to interact with VDAC in AD brains, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction likely by blocking mitochondrial pores [160]. These observations suggest that both the Aβ and the tau pathology directly acts on the enzyme metabolism of the brain and on the oxidative conditions in AD. Moreover, the deleterious effect of tau on mitochondria could be reciprocal. Mitochondrial stress was also reported to promote tau hyperphosphorylation in a mouse model lacking the detoxifying enzyme SOD2 [161]. It has been shown that inhibition of mitochondrial complex I reduces ATP levels and leads to a redistribution of tau from the axons to the cell body and cell death [162].

Tau plays a role in regulating mitochondrial dynamics, which can impact on mitochondrial function. By blocking recruitment of Drp1 to mitochondria, expression of human tau was shown to induce elongation of mitochondria in both Drosophila and mouse neurons, along with mitochondrial dysfunction and neurotoxicity [163]. These phenotypes can be rescued by genetically restoring the proper balance of mitochondrial fusion and fission. This study provides important evidence that tau itself may directly or indirectly influence mitochondrial function and dynamics in healthy neurons. As for the disease-related pathogenic tau mutants, expression of the Asp421-cleaved tau isoform, characteristic in the early stages of AD pathogenesis, has been found to lead to mitochondrial fragmentation in rat neurons [164]. Overexpressing mutant tau–causing frontotemporal dementia with Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17–decreases fusion and fission rates and makes cells more vulnerable to oxidative stress [156]. Hyperphosphorylated tau was reported to induce mitochondrial fission and excessive mitochondrial fragmentation in postmortem brain tissues from patients with AD and mouse models by directly interacting with Drp1 [114]. Taken together, these findings indicate that the pathogenic forms of tau could affect mitochondrial function either directly through interaction with VDAC or indirectly through interference with mitochondrial dynamics.

The predominant view of the mechanisms underlying synaptic degeneration is that pathological changes in tau trigger disruptions in microtubule-based cellular transport. Mitochondrial transport to presynaptic sites is essential for proper synaptic activity. Disrupting cellular transport prevents the trafficking of mitochondria to synapses, and is thought to trigger synaptic dysfunction and eventual dying-back of axons due to the essential roles of mitochondrial in ATP production and Ca2+ buffering [15, 24]. Tau is a microtubule-associated protein responsible for stabilizing microtubules in axons. The interaction of tau with microtubules is also critically involved in the regulation of microtubule-dependent axonal transport [165]. Tau binding to microtubules was shown to reverse the direction in which the dynein motors move, whereas the same process tends to cause kinesin to detach from the microtubules [166]. By interfering with kinesin motors for binding to microtubules, tau overexpression selectively inhibits kinesin-driven anterograde transport of mitochondria in N2a and NB2a/d1 neuroblastoma cell lines, primary cortical neurons, and retinal ganglion neurons [165, 167–170].

Impaired cellular transport could be caused by a loss of function of tau-stabilizing microtubules and/or a gain of toxic function of aggregated tau by blocking the microtubule tracks or directly interfering with cargos. Defects in axonal transport that are perceived to contribute to synaptic dysfunction appear to be mostly due to soluble forms of tau. Accumulation of prefibrillar tau oligomers correlates with cognitive decline in postmortem studies of brain from people with mild cognitive impairment [171, 172]. Recent data from models of tauopathy indicate that soluble forms of tau, but not NFT, are toxic to synapses. In rTg4510 mice, accumulation of soluble oligomers of tau correlates with memory loss [173]. Even in the absence of tangles, mice overexpressing human tau display significant synaptic degeneration, suggesting that soluble, oligomeric tau is the synaptotoxic species. Consistently, misfolded tau in the soma and neuropil threads is associated with reduced mitochondrial density in both rTg4510 mice and human AD. Interestingly, these alterations recovered after reducing the levels of soluble tau, even in the continued presence of aggregated misfolded tau [174]. These observations suggest that it is soluble tau but not aggregated tau, which impairs mitochondrial trafficking.

Accumulation of pathologically phosphorylated and misfolded tau is thought to impair axonal transport by directly competing with molecular motors or by impairing signaling cascades involved in the regulation of kinesin-based transport including JNK3 and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) [167, 175]. Over-expressing phospho-mutant forms of human tau was shown to reduce mitochondrial motility in cultured neurons [176]. Intriguingly, tau phosphorylation at the AT8 sites affects mitochondrial movement likely by controlling microtubule spacing [177]. Tau can also perturb axonal transport of mitochondria in the absence of hyperphosphorylation, which has been shown in P301L tau knock-in mice that did not develop tau pathology [178]. Besides ATP supply, mitochondrial are essential for maintaining Ca2+ homeostasis at synapses and tau-induced prevention of mitochondrial transport to synapses undoubtedly impairs synaptic Ca2+ buffering [154]. Additionally, the impact of mitochondria transport on tau pathology has also been investigated. In human tau transgenic flies, RNAi-mediated knockdown of Milton or Miro was found to enhance tau-induced neurodegeneration due to loss of axonal mitochondria resulting from inhibiting mitochondrial trafficking [179]. Together, tau-mediated impairment of axonal transport may trigger the deprivation of mitochondria from synaptic sites, thus contributing to defects in neurotransmitter release in AD pathology.

INTEGRATION: TAU AND Aβ-MEDIATED MITOCHONDRIAL DEFECTS IN AD

Several recent studies suggest that Aβ and tau act in concert in synapse degeneration [155, 180, 181]; mitochondria are key targets of Aβ toxicity and tau pathology in AD. Both lead to an increase in ROS levels, decreased activities of SOD, and a collapse of Δψm that results in reduced ATP levels. Aβ has been placed the upstream of tau in a pathological cascade [182]. When Aβ levels are increased, this activates distinct tau kinases and/or inactivates tau phosphatases, thus resulting in a massive tau hyperphosphorylation. The pathogenic forms of tau exacerbate mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired mitochondrial dynamics and axonal transport, which prevent mitochondria from sustaining synaptic activity. Thus, mitochondria-mediated ATP supply and Ca2+ handling at synapses are further undermined. Interestingly, complete or partial loss of tau expression in mutant neurons prevents Aβ-induced defects in mitochondrial transport by blocking activation of GSK3β [137, 183]. This suggests that the ability of Aβto inhibit mitochondrial motility is also dependent on tau expression levels. Together, tau and Aβ establish a vicious cycle of mitochondrial disturbance and misregulated mitochondrial trafficking, which causes functional failure of mitochondria to support neuro-transmitter release at AD synapses.

MITOCHONDRIA TRANSPORT-TARGETED THERAPEUTICS

Given the fact that mitochondrial transport plays a critical role in sustaining synaptic function in AD neurons, strategies reversing mitochondrial transport impairment holds potential for protective therapies to treat AD. Further research is needed to evaluate the efficacies of mitochondrial transport-targeted approaches in AD-linked models. While the current knowledge on the pharmacological modulation of mitochondrial transport is limited, mitochondrial transport can be upregulated through genetic manipulations of the molecular motor-adaptor transport and anchoring machineries. Overexpressing Miro enhances mitochondrial transport but also induces their interconnection [56, 67, 68, 184]. Furthermore, elevated Trak2 expression in hippocampal neurons also robustly increases axonal mitochondrial motility [54]. However, little is known whether these genetic manipulations have beneficial effects on AD-linked neurons. Second strategy aims at enhancing mitochondrial transport in AD neurons is to inhibit the function of syntaphilin, an axon-targeted and mitochondria-anchoring molecule. Syntaphilin was reported to immobilize axonal mitochondria by anchoring them to microtubules [13]. Genetic ablation of syntaphilin results in a robust increase of axonal mitochondria in motile pools [54, 185]. Thus, syntaphilin serves as an attractive molecular target for investigation into potential therapies mobilizing and recruiting mitochondria into synaptic terminals to reestablish synaptic function/integrity in AD context. Moreover, mitochondria-targeted antioxidant SS31 was shown to not only decrease the percentage of defective mitochondria, but more importantly, restore mitochondrial transport and synaptic function, suggesting protective effects on mitochondria and synapses from Aβ toxicity [117]. Additionally, it was shown that axonal transport of mitochondria can be facilitated by serotonin, which acts through the 5-HT1A-receptor subtype by increasing Akt activity and consequently decreasing GSK3β activity [186]. Therefore, rescuing impaired mitochondrial transport in AD neurons could be significant since the mechanism underlying Aβ-induced mitochondrial transport defects is proposed to be attributed to the activation of GSK3β [137, 183]. Mitochondria-protecting approaches that potentially prevent or delay the progression of AD are being assessed both in preclinical studies and clinical trials [187, 188]. Despite tremendous progress made in understanding disease progression and developing therapies, we still do not have drugs/agents to prevent, delay, and stop AD for our elderly population. Preventive measures (e.g., antioxidants, mitochondrial antioxidants, mitochondrial dynamics protectors, and transport enhancer) would hopefully benefit AD patients.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Enormous progress has been made in understanding the impact of mitochondrial functions on synaptic vesicle release. Mitochondria undergo dynamic trafficking to meet energy demands and control Ca2+ homeostasis at synapses, and thus play a crucial role in sustaining synaptic activity. Increasing evidence suggests the close correlation of mitochondrial dysfunction with synaptic degeneration, both of which are early events in AD pathophysiology. In pre-symptomatic stages of the disease, synaptic mitochondria exhibit functional alterations including impaired respiration and ATP synthesis, reduced Ca2+ buffering capacity, and elevated oxidative stress. Moreover, the deleterious effects of both Aβ and the pathogenic forms of tau on mitochondrial transport significantly impact their trafficking to synapses, which, in turn, substantially compromises their effects on neurotransmitter release. Mitochondria-protecting therapies have been designed and developed to reduce and clear Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau, to stabilize tau and microtubule-associated motor/adaptor proteins, and to protect Δψm. These strategies hope to benefit patients prior to the onset of cognitive decline by halting the cascade leading to the development of AD and by preventing or delaying the progress of AD in patients with mild cognitive impairments. The majority of therapeutics will need a long process of clinical development. Thus, the overall information described in this review indicates that the better understanding of molecular mechanisms by which Aβ and tau affect mitochondria and its function at synapses remains essential for the prevention and treatment of AD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank C. Agrawal for editing and other members of the Cai laboratory for their assistance and discussion. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R00AG033658 and R01NS089737 to Q.C.]; the Alzheimer’s Association [NIRG-14-321833 to Q.C.].

References

- 1.Attwell D, Laughlin SB. An energy budget for signaling in the grey matter of the brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1133–1145. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verstreken P, Ly CV, Venken KJ, Koh TW, Zhou Y, Bellen HJ. Synaptic mitochondria are critical for mobilization of reserve pool vesicles at Drosophila neuromuscular junctions. Neuron. 2005;47:365–378. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun T, Qiao H, Pan PY, Chen Y, Sheng ZH. Motile axonal mitochondria contribute to the variability of presynaptic strength. Cell Rep. 2013;4:413–419. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rangaraju V, Calloway N, Ryan TA. Activity-driven local ATP synthesis is required for synaptic function. Cell. 2014;156:825–835. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gazit N, Vertkin I, Shapira I, Helm M, Slomowitz E, Sheiba M, Mor Y, Rizzoli S, Slutsky I. IGF-1 receptor differentially regulates spontaneous and evoked transmission via mitochondria at hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 2016;89:583–597. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Z, Okamoto K, Hayashi Y, Sheng M. The importance of dendritic mitochondria in the morphogenesis and plasticity of spines and synapses. Cell. 2004;119:873–887. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee CW, Peng HB. The function of mitochondria in presynaptic development at the neuromuscular junction. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:150–158. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werth JL, Thayer SA. Mitochondria buffer physiological calcium loads in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurosci. 1994;14:348–356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-01-00348.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang Y, Zucker RS. Mitochondrial involvement in post-tetanic potentiation of synaptic transmission. Neuron. 1997;18:483–491. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81248-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Billups B, Forsythe ID. Presynaptic mitochondrial calcium sequestration influences transmission at mammalian central synapses. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5840–5847. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-05840.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.David G, Barrett EF. Mitochondrial Ca2+uptake prevents desynchronization of quantal release and minimizes depletion during repetitive stimulation of mouse motor nerve terminals. J Physiol. 2003;548:425–438. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.035196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levy M, Faas GC, Saggau P, Craigen WJ, Sweatt JD. Mitochondrial regulation of synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17727–17734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang JS, Tian JH, Pan PY, Zald P, Li C, Deng C, Sheng ZH. Docking of axonal mitochondria by syntaphilin controls their mobility and affects short-term facilitation. Cell. 2008;132:137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Court FA, Coleman MP. Mitochondria as a central sensor for axonal degenerative stimuli. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheng ZH, Cai Q. Mitochondrial transport in neurons: Impact on synaptic homeostasis and neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:77–93. doi: 10.1038/nrn3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai Q, Tammineni P. Alterations in mitochondrial quality control in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Cell Neurosci. 2016;10:24. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2016.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mishra P, Chan DC. Mitochondrial dynamics and inheritance during cell division, development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:634–646. doi: 10.1038/nrm3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sims NR, Finegan JM, Blass JP, Bowen DM, Neary D. Mitochondrial function in brain tissue in primary degenerative dementia. Brain Res. 1987;436:30–38. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91553-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pettegrew JW, Panchalingam K, Klunk WE, McClure RJ, Muenz LR. Alterations of cerebral metabolism in probable Alzheimer’s disease: A preliminary study. Neurobiol Aging. 1994;15:117–132. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(94)90152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duara R, Grady C, Haxby J, Sundaram M, Cutler NR, Heston L, Moore A, Schlageter N, Larson S, Rapoport SI. Positron emission tomography in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1986;36:879–887. doi: 10.1212/wnl.36.7.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haxby JV, Grady CL, Duara R, Schlageter N, Berg G, Rapoport SI. Neocortical metabolic abnormalities precede nonmemory cognitive defects in early Alzheimer’s-type dementia. Arch Neurol. 1986;43:882–885. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1986.00520090022010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukui H, Moraes CT. The mitochondrial impairment, oxidative stress and neurodegeneration connection: Reality or just an attractive hypothesis? Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swerdlow RH, Burns JM, Khan SM. The Alzheimer’s disease mitochondrial cascade hypothesis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 2):S265–S279. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheng ZH. Mitochondrial trafficking and anchoring in neurons: New insight and implications. J Cell Biol. 2014;204:1087–1098. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201312123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stock D, Gibbons C, Arechaga I, Leslie AG, Walker JE. The rotary mechanism of ATP synthase. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10:672–679. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00147-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM, Ames BN. Oxidative damage and mitochondrial decay in aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:10771–10778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408:239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirichok Y, Krapivinsky G, Clapham DE. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter is a highly selective ion channel. Nature. 2004;427:360–364. doi: 10.1038/nature02246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crompton M, Virji S, Ward JM. Cyclophilin-D binds strongly to complexes of the voltage-dependent anion channel and the adenine nucleotide translocase to form the permeability transition pore. Eur J Biochem. 1998;258:729–735. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2580729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halestrap AP, Woodfield KY, Connern CP. Oxidative stress, thiol reagents, and membrane potential modulate the mitochondrial permeability transition by affecting nucleotide binding to the adenine nucleotide translocase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3346–3354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Connern CP, Halestrap AP. Recruitment of mitochondrial cyclophilin to the mitochondrial inner membrane under conditions of oxidative stress that enhance the opening of a calcium-sensitive non-specific channel. Biochem J. 1994;302(Pt 2):321–324. doi: 10.1042/bj3020321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bernardi P, Krauskopf A, Basso E, Petronilli V, Blachly-Dyson E, Di Lisa F, Forte MA. The mitochondrial permeability transition from in vitro artifact to disease target. FEBS J. 2006;273:2077–2099. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernardi P. Mitochondrial transport of cations: Channels, exchangers, and permeability transition. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1127–1155. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crompton M. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore and its role in cell death. Biochem J. 1999;341(Pt 2):233–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halestrap AP, Kerr PM, Javadov S, Woodfield KY. Elucidating the molecular mechanism of the permeability transition pore and its role in reperfusion injury of the heart. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1366:79–94. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green DR, Kroemer G. The pathophysiology of mitochondrial cell death. Science. 2004;305:626–629. doi: 10.1126/science.1099320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Green DR, Reed JC. Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science. 1998;281:1309–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D’Amelio M, Sheng M, Cecconi F. Caspase-3 in the central nervous system: Beyond apoptosis. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:700–709. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.D’Amelio M, Cavallucci V, Cecconi F. Neuronal caspase-3 signaling: Not only cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:1104–1114. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hollenbeck PJ, Saxton WM. The axonal transport of mitochondria. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5411–5419. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shepherd GM, Harris KM. Three-dimensional structure and composition of CA3–>CA1 axons in rat hippocampal slices: Implications for presynaptic connectivity and compartmentalization. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8300–8310. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08300.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rowland KC, Irby NK, Spirou GA. Specialized synapse-associated structures within the calyx of Held. J Neurosci. 2000;20:9135–9144. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09135.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Misgeld T, Kerschensteiner M, Bareyre FM, Burgess RW, Lichtman JW. Imaging axonal transport of mitochondria in vivo. Nat Methods. 2007;4:559–561. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hurd DD, Saxton WM. Kinesin mutations cause motor neuron disease phenotypes by disrupting fast axonal transport in Drosophila. Genetics. 1996;144:1075–1085. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.3.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanaka Y, Kanai Y, Okada Y, Nonaka S, Takeda S, Harada A, Hirokawa N. Targeted disruption of mouse conventional kinesin heavy chain, kif5B, results in abnormal perinuclear clustering of mitochondria. Cell. 1998;93:1147–1158. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81459-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cai Q, Gerwin C, Sheng ZH. Syntabulin-mediated anterograde transport of mitochondria along neuronal processes. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:959–969. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pilling AD, Horiuchi D, Lively CM, Saxton WM. Kinesin-1 and Dynein are the primary motors for fast transport of mitochondria in Drosophila motor axons. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:2057–2068. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-06-0526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gorska-Andrzejak J, Stowers RS, Borycz J, Kostyleva R, Schwarz TL, Meinertzhagen IA. Mitochondria are redistributed in Drosophila photoreceptors lacking milton, a kinesin-associated protein. J Comp Neurol. 2003;463:372–388. doi: 10.1002/cne.10750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stowers RS, Megeath LJ, Gorska-Andrzejak J, Meinertzhagen IA, Schwarz TL. Axonal transport of mitochondria to synapses depends on milton, a novel Drosophila protein. Neuron. 2002;36:1063–1077. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glater EE, Megeath LJ, Stowers RS, Schwarz TL. Axonal transport of mitochondria requires milton to recruit kinesin heavy chain and is light chain independent. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:545–557. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200601067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.MacAskill AF, Brickley K, Stephenson FA, Kittler JT. GTPase dependent recruitment of Grif-1 by Miro1 regulates mitochondrial trafficking in hippocampal neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;40:301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith MJ, Pozo K, Brickley K, Stephenson FA. Mapping the GRIF-1 binding domain of the kinesin, KIF5C, substantiates a role for GRIF-1 as an adaptor protein in the anterograde trafficking of cargoes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27216–27228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600522200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koutsopoulos OS, Laine D, Osellame L, Chudakov DM, Parton RG, Frazier AE, Ryan MT. Human Miltons associate with mitochondria and induce microtubule-dependent remodeling of mitochondrial networks. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803:564–574. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen Y, Sheng ZH. Kinesin-1-syntaphilin coupling mediates activity-dependent regulation of axonal mitochondrial transport. J Cell Biol. 2013;202:351–364. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201302040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brickley K, Stephenson FA. Trafficking kinesin protein (TRAK)-mediated transport of mitochondria in axons of hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:18079–18092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.236018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fransson S, Ruusala A, Aspenstrom P. The atypical Rho GTPases Miro-1 and Miro-2 have essential roles in mitochondrial trafficking. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344:500–510. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frederick RL, McCaffery JM, Cunningham KW, Okamoto K, Shaw JM. Yeast Miro GTPase, Gem1p, regulates mitochondrial morphology via a novel pathway. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:87–98. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200405100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo X, Macleod GT, Wellington A, Hu F, Panchumarthi S, Schoenfield M, Marin L, Charlton MP, Atwood HL, Zinsmaier KE. The GTPase dMiro is required for axonal transport of mitochondria to Drosophila synapses. Neuron. 2005;47:379–393. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cho KI, Cai Y, Yi H, Yeh A, Aslanukov A, Ferreira PA. Association of the kinesin-binding domain of RanBP2 to KIF5B and KIF5C determines mitochondria localization and function. Traffic. 2007;8:1722–1735. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fujita T, Maturana AD, Ikuta J, Hamada J, Walchli S, Suzuki T, Sawa H, Wooten MW, Okajima T, Tatematsu K, Tanizawa K, Kuroda S. Axonal guidance protein FEZ1 associates with tubulin and kinesin motor protein to transport mitochondria in neurites of NGF-stimulated PC12 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;361:605–610. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Russo GJ, Louie K, Wellington A, Macleod GT, Hu F, Panchumarthi S, Zinsmaier KE. Drosophila Miro is required for both anterograde and retrograde axonal mitochondrial transport. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5443–5455. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5417-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rintoul GL, Filiano AJ, Brocard JB, Kress GJ, Reynolds IJ. Glutamate decreases mitochondrial size and movement in primary forebrain neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7881–7888. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-21-07881.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yi M, Weaver D, Hajnoczky G. Control of mitochondrial motility and distribution by the calcium signal: A homeostatic circuit. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:661–672. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chang DT, Honick AS, Reynolds IJ. Mitochondrial trafficking to synapses in cultured primary cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7035–7045. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1012-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ohno N, Kidd GJ, Mahad D, Kiryu-Seo S, Avishai A, Komuro H, Trapp BD. Myelination and axonal electrical activity modulate the distribution and motility of mitochondria at CNS nodes of Ranvier. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7249–7258. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0095-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Szabadkai G, Simoni AM, Bianchi K, De Stefani D, Leo S, Wieckowski MR, Rizzuto R. Mitochondrial dynamics and Ca2+ signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:442–449. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Macaskill AF, Rinholm JE, Twelvetrees AE, Arancibia-Carcamo IL, Muir J, Fransson A, Aspenstrom P, Attwell D, Kittler JT. Miro1 is a calcium sensor for glutamate receptor-dependent localization of mitochondria at synapses. Neuron. 2009;61:541–555. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saotome M, Safiulina D, Szabadkai G, Das S, Fransson A, Aspenstrom P, Rizzuto R, Hajnoczky G. Bidirectional Ca2+-dependent control of mitochondrial dynamics by the Miro GTPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20728–20733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808953105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang X, Schwarz TL. The mechanism of Ca2+-dependent regulation of kinesin-mediated mitochondrial motility. Cell. 2009;136:163–174. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hubley MJ, Locke BR, Moerland TS. The effects of temperature, pH, and magnesium on the diffusion coefficient of ATP in solutions of physiological ionic strength. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1291:115–121. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(96)00053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen YM, Gerwin C, Sheng ZH. Dynein light chain LC8 regulates syntaphilin-mediated mitochondrial docking in axons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9429–9438. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1472-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ma H, Cai Q, Lu W, Sheng ZH, Mochida S. KIF5B motor adaptor syntabulin maintains synaptic transmission in sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13019–13029. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2517-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gibson GE, Shi Q. A mitocentric view of Alzheimer’s disease suggests multi-faceted treatments. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 2):S591–S607. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Reiman EM, Caselli RJ, Yun LS, Chen K, Bandy D, Minoshima S, Thibodeau SN, Osborne D. Pre-clinical evidence of Alzheimer’s disease in persons homozygous for the epsilon 4 allele for apolipoprotein E. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:752–758. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603213341202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mosconi L, de Leon M, Murray J, EL, Lu J, Javier E, McHugh P, Swerdlow RH. Reduced mitochondria cytochrome oxidase activity in adult children of mothers with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;27:483–490. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Smith MA, Perry G, Richey PL, Sayre LM, Anderson VE, Beal MF, Kowall N. Oxidative damage in Alzheimer’s. Nature. 1996;382:120–121. doi: 10.1038/382120b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Maurer I, Zierz S, Moller HJ. A selective defect of cytochrome c oxidase is present in brain of Alzheimer disease patients. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:455–462. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hirai K, Aliev G, Nunomura A, Fujioka H, Russell RL, Atwood CS, Johnson AB, Kress Y, Vinters HV, Tabaton M, Shimohama S, Cash AD, Siedlak SL, Harris PL, Jones PK, Petersen RB, Perry G, Smith MA. Mitochondrial abnormalities in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3017–3023. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-09-03017.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Devi L, Prabhu BM, Galati DF, Avadhani NG, Anandatheerthavarada HK. Accumulation of amyloid precursor protein in the mitochondrial import channels of human Alzheimer’s disease brain is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9057–9068. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1469-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Caspersen C, Wang N, Yao J, Sosunov A, Chen X, Lustbader JW, Xu HW, Stern D, McKhann G, Yan SD. Mitochondrial Abeta: A potential focal point for neuronal metabolic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2005;19:2040–2041. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3735fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Manczak M, Park BS, Jung Y, Reddy PH. Differential expression of oxidative phosphorylation genes in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: Implications for early mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage. Neuromolecular Med. 2004;5:147–162. doi: 10.1385/NMM:5:2:147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Manczak M, Calkins MJ, Reddy PH. Impaired mitochondrial dynamics and abnormal interaction of amyloid beta with mitochondrial protein Drp1 in neurons from patients with Alzheimer’s disease: Implications for neuronal damage. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:2495–2509. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Parker WD, Jr, Filley CM, Parks JK. Cytochrome oxidase deficiency in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1990;40:1302–1303. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.8.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Butterfield DA, Drake J, Pocernich C, Castegna A. Evidence of oxidative damage in Alzheimer’s disease brain: Central role for amyloid beta-peptide. Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:548–554. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Parker WD, Jr, Parks JK. Cytochrome c oxidase in Alzheimer’s disease brain: Purification and characterization. Neurology. 1995;45:482–486. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.3.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Parker WD, Jr, Mahr NJ, Filley CM, Parks JK, Hughes D, Young DA, Cullum CM. Reduced platelet cytochrome c oxidase activity in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1994;44:1086–1090. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.6.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cardoso SM, Proenca MT, Santos S, Santana I, Oliveira CR. Cytochrome c oxidase is decreased in Alzheimer’s disease platelets. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:105–110. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(03)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pickrell AM, Fukui H, Moraes CT. The role of cytochrome c oxidase deficiency in ROS and amyloid plaque formation. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2009;41:453–456. doi: 10.1007/s10863-009-9245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sorbi S, Bird ED, Blass JP. Decreased pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity in Huntington and Alzheimer brain. Ann Neurol. 1983;13:72–78. doi: 10.1002/ana.410130116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gibson GE, Blass JP, Beal MF, Bunik V. The alpha-ketoglutarate-dehydrogenase complex: A mediator between mitochondria and oxidative stress in neurodegeneration. Mol Neurobiol. 2005;31:43–63. doi: 10.1385/MN:31:1-3:043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gibson GE, Zhang H, Sheu KF, Bogdanovich N, Lindsay JG, Lannfelt L, Vestling M, Cowburn RF. Alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase in Alzheimer brains bearing the APP670/671 mutation. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:676–681. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lin MT, Simon DK, Ahn CH, Kim LM, Beal MF. High aggregate burden of somatic mtDNA point mutations in aging and Alzheimer’s disease brain. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:133–145. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Coskun PE, Beal MF, Wallace DC. Alzheimer’s brains harbor somatic mtDNA control-region mutations that suppress mitochondrial transcription and replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10726–10731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403649101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Coskun PE, Wyrembak J, Derbereva O, Melkonian G, Doran E, Lott IT, Head E, Cotman CW, Wallace DC. Systemic mitochondrial dysfunction and the etiology of Alzheimer’s disease and down syndrome dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 2):S293–S310. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Reddy PH. Mitochondrial medicine for aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Neuromolecular Med. 2008;10:291–315. doi: 10.1007/s12017-008-8044-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Reddy PH, Beal MF. Amyloid beta, mitochondrial dysfunction and synaptic damage: Implications for cognitive decline in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Reddy PH, McWeeney S, Park BS, Manczak M, Gutala RV, Partovi D, Jung Y, Yau V, Searles R, Mori M, Quinn J. Gene expression profiles of transcripts in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice: Up-regulation of mitochondrial metabolism and apoptotic genes is an early cellular change in Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1225–1240. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chandrasekaran K, Giordano T, Brady DR, Stoll J, Martin LJ, Rapoport SI. Impairment in mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase gene expression in Alzheimer disease. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1994;24:336–340. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Manczak M, Jung Y, Park BS, Partovi D, Reddy PH. Time-course of mitochondrial gene expressions in mice brains: Implications for mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative damage, and cytochrome c in aging. J Neurochem. 2005;92:494–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Baloyannis SJ. Mitochondrial alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9:119–126. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Moreira PI, Siedlak SL, Wang X, Santos MS, Oliveira CR, Tabaton M, Nunomura A, Szweda LI, Aliev G, Smith MA, Zhu X, Perry G. Autophagocytosis of mitochondria is prominent in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:525–532. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000240476.73532.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Trushina E, Nemutlu E, Zhang S, Christensen T, Camp J, Mesa J, Siddiqui A, Tamura Y, Sesaki H, Wengenack TM, Dzeja PP, Poduslo JF. Defects in mitochondrial dynamics and metabolomic signatures of evolving energetic stress in mouse models of familial Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32737. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Reddy PH. Abnormal tau, mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired axonal transport of mitochondria, and synaptic deprivation in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 2011;1415:136–148. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.07.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Anandatheerthavarada HK, Biswas G, Robin MA, Avadhani NG. Mitochondrial targeting and a novel transmembrane arrest of Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein impairs mitochondrial function in neuronal cells. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:41–54. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dragicevic N, Mamcarz M, Zhu Y, Buzzeo R, Tan J, Arendash GW, Bradshaw PC. Mitochondrial amyloid-beta levels are associated with the extent of mitochondrial dysfunction in different brain regions and the degree of cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s transgenic mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 2):S535–S550. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mattson MP, Partin J, Begley JG. Amyloid beta-peptide induces apoptosis-related events in synapses and dendrites. Brain Res. 1998;807:167–176. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00763-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lustbader JW, Cirilli M, Lin C, Xu HW, Takuma K, Wang N, Caspersen C, Chen X, Pollak S, Chaney M, Trinchese F, Liu S, Gunn-Moore F, Lue LF, Walker DG, Kuppusamy P, Zewier ZL, Arancio O, Stern D, Yan SS, Wu H. ABAD directly links Abeta to mitochondrial toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2004;304:448–452. doi: 10.1126/science.1091230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Du H, Guo L, Fang F, Chen D, Sosunov AA, McKhann GM, Yan Y, Wang C, Zhang H, Molkentin JD, Gunn-Moore FJ, Vonsattel JP, Arancio O, Chen JX, Yan SD. Cyclophilin D deficiency attenuates mitochondrial and neuronal perturbation and ameliorates learning and memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 2008;14:1097–1105. doi: 10.1038/nm.1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Manczak M, Mao P, Calkins MJ, Cornea A, Reddy AP, Murphy MP, Szeto HH, Park B, Reddy PH. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants protect against amyloid-beta toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease neurons. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 2):S609–S631. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Keller JN, Pang Z, Geddes JW, Begley JG, Germeyer A, Waeg G, Mattson MP. Impairment of glucose and glutamate transport and induction of mitochondrial oxidative stress and dysfunction in synaptosomes by amyloid beta-peptide: Role of the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal. J Neurochem. 1997;69:273–284. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69010273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Abramov AY, Canevari L, Duchen MR. Beta-amyloid peptides induce mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in astrocytes and death of neurons through activation of NADPH oxidase. J Neurosci. 2004;24:565–575. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4042-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Manczak M, Anekonda TS, Henson E, Park BS, Quinn J, Reddy PH. Mitochondria are a direct site of A beta accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease neurons: Implications for free radical generation and oxidative damage in disease progression. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1437–1449. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]