Summary

Genotype specificity is a big problem lagging the development of efficient hexaploid wheat transformation system. Increasingly, the biosecurity of genetically modified organisms is garnering public attention, so the generation of marker‐free transgenic plants is very important to the eventual potential commercial release of transgenic wheat. In this study, 15 commercial Chinese hexaploid wheat varieties were successfully transformed via an Agrobacterium‐mediated method, with efficiency of up to 37.7%, as confirmed by the use of Quickstix strips, histochemical staining, PCR analysis and Southern blotting. Of particular interest, marker‐free transgenic wheat plants from various commercial Chinese varieties and their F1 hybrids were successfully obtained for the first time, with a frequency of 4.3%, using a plasmid harbouring two independent T‐DNA regions. The average co‐integration frequency of the gus and the bar genes located on the two independent T‐DNA regions was 49.0% in T0 plants. We further found that the efficiency of generating marker‐free plants was related to the number of bar gene copies integrated in the genome. Marker‐free transgenic wheat plants were identified in the progeny of three transgenic lines that had only one or two bar gene copies. Moreover, silencing of the bar gene was detected in 30.7% of T1 positive plants, but the gus gene was never found to be silenced in T1 plants. Bisulphite genomic sequencing suggested that DNA methylation in the 35S promoter of the bar gene regulatory region might be the main reason for bar gene silencing in the transgenic plants.

Keywords: hexaploid wheat, two independent T‐DNA vectors, co‐transformation, marker‐free transgenic plants, transgene silencing

Introduction

Hexaploid wheat is an important worldwide food crop that contributes as much as 35% of the calories consumed by the global population (Godfray et al., 2010; Shewry, 2009). To meet increasing demand, it is necessary to improve various economically important traits in wheat by genetic engineering approaches (He et al., 2011; Tester and Langridge, 2010). Genetic transformation techniques have been used successfully in the improvement of some major crop species, including soya bean, maize and cotton. New varieties of these plants that have been developed by transgenic methods are now planted widely in many countries, offering great benefits to farmers and helping to protect the environment (James, 2016). However, no commercially released genetically modified wheat variety has been developed, owing partially to its much lower transformation efficiency relative to other crops and also to negative public perceptions about transgenic plants (Bhalla, 2006; Harwood, 2012; Li et al., 2012). Recently, Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation efficiency in wheat has been improved dramatically. The Japan Tobacco Company developed what they call the PureWheat technique for the spring wheat variety Fielder is used (Ishida et al., 2015). Employing this PureWheat technique, Richardson et al. (2014) successfully transformed two Australian commercial wheat varieties, Westonia and Gladius, with efficiencies of 45% and 32%, respectively. Marker‐free transgenic Fielder and Gladius wheat plants were obtained with an efficiency of 3% without imposing selection pressure during tissue culture step. This dramatic progress will almost certainly promote the development and eventual commercial introduction of transgenic wheat varieties.

The biosafety of commercialized genetically modified plants has attracted considerable public attention. It is considered important to generate marker‐free varieties where the marker gene used for the generation of positive transgenic plants has been eliminated. Marker‐free transgenic plants can be produced by FLP/FRT site‐specific recombination (Nandy and Srivastava, 2011; Nanto and Ebinuma, 2008), Cre/lox site‐specific recombination (Li et al., 2007; Mészáros et al., 2015; Mlynarova and Nap, 2003; Moravcikova et al., 2008), multi‐auto‐transformation (Khan et al., 2011), co‐transformation (Miller et al., 2002) and using a marker‐free binary vector (McCormac et al., 2001). Among these methods, co‐transformation is the most efficient and simple technique (Tuteja et al., 2012). Marker‐free transgenic plants have been generated with the use of an Agrobacterium‐mediated co‐transformation system with a plasmid that contains two independent T‐DNA regions for many species including tobacco (McCormac et al., 2001), soya bean (Xing et al., 2000), maize (Miller et al., 2002), sorghum (Lu et al., 2009), rice (Rao et al., 2011) and durum wheat (Wang et al., 2016). The average frequencies of co‐transformation of the gene of interest with the selectable marker gene in sorghum and rice were reported to be 45% and 67%, respectively (Lu et al., 2009; Rao et al., 2011). In addition, marker‐free soya bean plants were obtained at a frequency of 7.2% using an Agrobacterium‐mediated co‐transformation plasmid with three independent T‐DNA regions (Ye and Qin, 2008). The establishment of an efficient Agrobacterium‐mediated wheat transformation system by the Japan Tobacco Company has laid a solid foundation for routinely obtaining marker‐free transgenic hexaploid wheat plants by employing an Agrobacterium‐mediated co‐transformation system.

The objective of this study was to establish a system to produce marker‐free transgenic commercial Chinese hexaploid wheat varieties by Agrobacterium‐mediated co‐transformation with two independent T‐DNA regions, and to thereby widen the genotype range for wheat transgenic breeding and variety development. Our study also revealed the silencing reason of selection bar gene in the transgenic wheat plants.

Results

Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation efficiencies of 17 commercial Chinese wheat cultivars

To generate marker‐free transgenic commercial Chinese hexaploid wheat varieties by Agrobacterium‐mediated co‐transformation, a universal expression vector pWMB122 for biosafety purpose containing two independent T‐DNA regions was constructed as shown in Figure S1. One T‐DNA region harbours the bar selectable marker under the control of the CaMV35S promoter and the Agrobacterium nopaline synthase (NOS) terminator sequence, and the other T‐DNA harbours the maize ubiquitin (ubi) promoter, a multiple cloning site (MCS) and the NOS terminator sequence (Figure S1). The gus (β‐glucuronidase) reporter gene was inserted into the BamHI and SacI sites in the MCS of pWMB122 to form the vector pWMB123 (Figure 1), which was used for all of the transformation experiments in this study.

Figure 1.

Vector map of pWMB123 showing two T‐DNA regions containing the bar and gus expression cassettes.

Immature embryos of 17 commercial Chinese hexaploid wheat varieties, as well as the model wheat line Fielder, were transformed with Agrobacterium harbouring the pWMB123 expression vector. After culturing on WLS resting medium, a subset of transformed wheat explants was analysed for transient expression of gus. All of the commercial Chinese wheat cultivars tested showed strong gus expression in the infected immature embryos (Figure S2), which suggests that the cultivars used in the present investigation were amenable to Agrobacterium infection. However, there were large differences among the varieties in the production of primary callus, the production of embryonic callus and shoot regeneration on selection media containing PPT 5–10 mg/L.

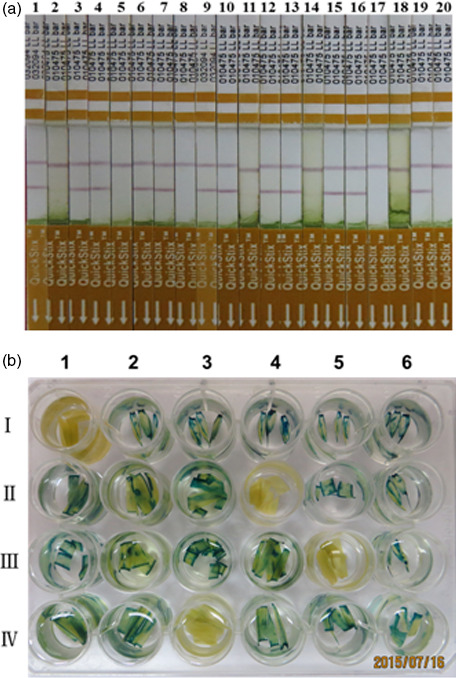

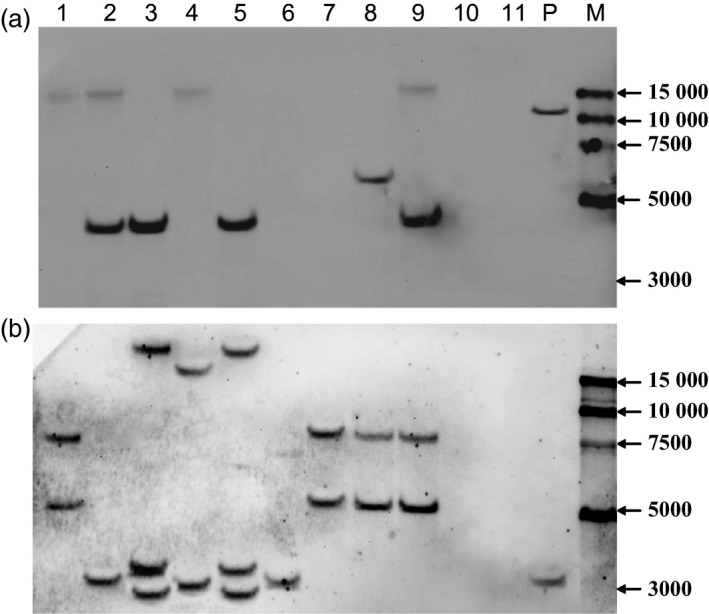

Putative T0 transgenic wheat plants were identified based on Quickstix strip detection of bar protein (Figure 2a), histochemical analysis of gus activity (Figure 2b), and PCR and Southern blot detection of the bar and gus genes (Figure 3). Transgenic plants were obtained for 15 of the 17 commercial Chinese wheat varieties with transformation efficiencies ranging from 2.7% for Jimai22 to 37.7% for CB037 (Table 1). More than 10% transformation efficiency was achieved for Kenong199, Jimai5265, Zhoumai18, Neimai836, Jingdong18, Xinchun9 and CB037. Of particular note, CB037 reached transformation efficiency close to that of Fielder (45.3%). Only two commercial varieties, AK58 and Jing411, did not yield transgenic plants. These results reveal that most of the commercial Chinese wheat varieties used in this study are able to be transformed by Agrobacterium, although most varieties had comparatively low transformation efficiencies compared to Fielder. Among 237 bar‐positive T0 plants, only 117 plants were confirmed to have the gus gene, and the average gus and bar gene co‐integration rate was 49.0% (Table 1). Southern blotting revealed that the gus gene was single copy in most transgenic wheat plants (Figure 3a). However, the bar gene integration was observed in a few transgenic plants as a single copy, and in most plants by multiple copies (Figure 3b). This indicates that different numbers of the gus gene and the bar gene integrated into the same genome. All of the T0 positive transgenic plants obtained from the commercial Chinese wheat varieties have normal fertility, and we did not find any sterile transgenic plants.

Figure 2.

Detection of putative T0 transgenic hexaploid wheat plants with QuickStix strips for the bar protein (a) and histochemical staining for the gus gene (b). a: 1, bar‐positive plants from CB037; 2, wild‐type CB037; 3‐4, bar‐positive plants from Kenong199; 5, wild‐type Kenong199; 6‐7, bar‐positive plants from Xinchun9; 8, wild‐type Xinchun9; 9‐10, bar‐positive plants from Jimai5265; 11, wild‐type Jimai5265; 12‐13, bar‐positive plants from Shi4185; 14, wild‐type Ahi4185; 15‐16, bar‐positive plants from Shiluan02‐1; 17, wild‐type Shiluan02‐1; 18, a bar‐negative plant from Jimai22; 19, bar‐positive plants from Jimai22; 20, wild‐type Jimai22. b: I1, wild‐type Kenong199; I2‐I6, gus‐positive plants from Kenong199; II 1‐ II 3, II 5‐ II 6, gus‐positive plants from Xichun9; II 4, wild‐type Xinchun9; III1‐ III 4, III 6, gus‐positive plants from CB037; III 5, wild‐type CB037; IV1‐IV2, IV4‐IV6, gus‐positive plants from Jimai5265; IV3, wild‐type Jimai5265.

Figure 3.

Southern blot analysis of gus (a) and bar (b) genes copy number in T0 transgenic hexaploid wheat plants. 1‐11: T0 transgenic plants (1, C1 from CB037, gus+bar+; 2, KC2 from the KC hybrid, gus+bar+; 3, KC4 from the KC hybrid, gus+bar+; 4, KC1 from the KC hybrid, gus+bar+; 5, KC3 from the KC hybrid, gus+bar+; 6, K1 from Kenong199, gus−bar+; 7, X1 from Xinchun9, gus−bar+; 8, K3 from Kenong199, gus+bar+; 9, C2 from CB037, gus+bar+; 10, FC1 from the FC hybrid, gus−bar−; 11, Kenong199 as control);P: expression vector pWMB123;M: 15000‐bp DNA marker.

Table 1.

Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation efficiencies of commercial hexaploid Chinese wheat varieties

| Varieties | Growth habit | Number of experiments | Number of Immature embryos transformed | Plants with Liberty activity | Transformation efficiency (%) | Co‐transformation rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kenong199 | Facultative | 3 | 110 | 25 | 22.7 | 44.0 |

| Shiluan02‐1 | Facultative | 4 | 167 | 16 | 9.9 | 38.5 |

| Shi4185 | Facultative | 3 | 125 | 10 | 8.0 | 53.3 |

| Chuanmai42 | Facultative | 4 | 132 | 11 | 8.3 | 60.0 |

| Jimai5265 | Facultative | 2 | 95 | 14 | 14.7 | 51.7 |

| Zhoumai18 | Facultative | 5 | 260 | 35 | 13.5 | 58.3 |

| Neimai836 | Facultative | 4 | 206 | 25 | 12.1 | 66.7 |

| Zhongmai895 | Winter | 2 | 138 | 5 | 3.6 | NA |

| Lunxuan987 | Winter | 2 | 69 | 2 | 2.9 | NA |

| Jingdong18 | Winter | 3 | 96 | 17 | 17.7 | NA |

| Jimai22 | Winter | 5 | 297 | 8 | 2.7 | NA |

| AK58 | Facultative | 6 | 316 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Zhengmai7698 | Facultative | 3 | 188 | 23 | 12.2 | NA |

| Yangmai16 | Facultative | 5 | 208 | 12 | 5.8 | NA |

| Jing411 | Winter | 4 | 216 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Xinchun9 | Spring | 3 | 165 | 22 | 13.3 | 60.0 |

| CB037 | Spring | 3 | 138 | 52 | 37.7 | 50.0 |

| Fielder | Spring | 3 | 181 | 82 | 45.3 | 50.0 |

NA, not available.

Transformation efficiencies of F1 hybrids derived from crosses between various wheat varieties

Fielder and CB037 (high transformability), Kenong199 and Xinchun9 (medium transformability), and Jimai22 (low transformability) were used to make four hybrid crosses: Kenong199 × CB037 (KC), Kenong199 × Fielder (KF), Xinchun9 × Fielder (XF) and Jimai22 × Fielder (JF). The immature embryos of the four F1 hybrids and their parents were transformed with Agrobacterium harbouring pWMB123. Transgenes were detected by histochemical staining, Quickstix strips and PCR analysis. Transformation efficiencies of three hybrids, KF, XF and JF, were between the values of their parents, and the transformation efficiency of the hybrid KC was close to the value of its high transformability parent CB037 (Table 2). These results suggest that wheat transformability is a quantitative trait and might therefore be controlled by a few loci. Southern blot analysis was used to detect the integration status of the gus and bar gene cassettes in a subset of the transgenic plants (Figure 3). It is suggested that the gus gene and the bar gene were inserted into the genomes of the same transgenic plants by different copy numbers. Also, all of the T0 positive transgenic plants obtained from the F1 hybrid plants and their parents have normal fertility, and no sterile transgenic plants were found.

Table 2.

Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation efficiencies of four F1 hybrids and their hexaploid wheat parents

| F1 hybrids | Number of experiments | Number of Immature embryos transformed | Plants with gus activity | Transformation efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kenong199 | 1 | 54 | 13 | 24.1 |

| CB037 | 1 | 46 | 16 | 34.7 |

| Kenong199 × CB037 | 2 | 99 | 37 | 37.4 |

| Fielder | 2 | 77 | 41 | 53.2 |

| Xinchun9 | 2 | 77 | 10 | 13.0 |

| Xinchun9 × Fielder | 1 | 55 | 21 | 38.2 |

| Kenong199 × Fielder | 2 | 80 | 30 | 37.5 |

| Jimai22 | 2 | 67 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Jimai22 × Fielder | 2 | 78 | 12 | 15.4 |

Screening for marker‐free transgenic wheat plants and transgene inheritance in the T1 generation

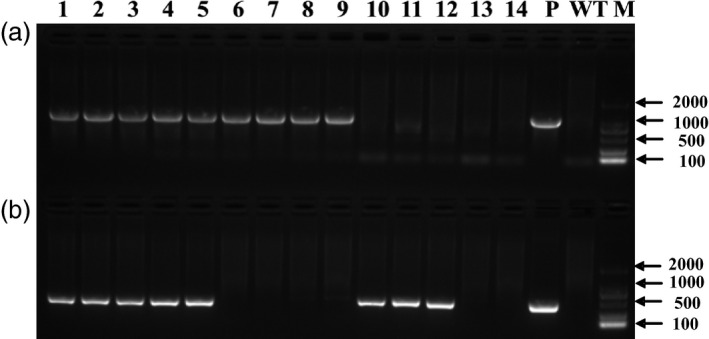

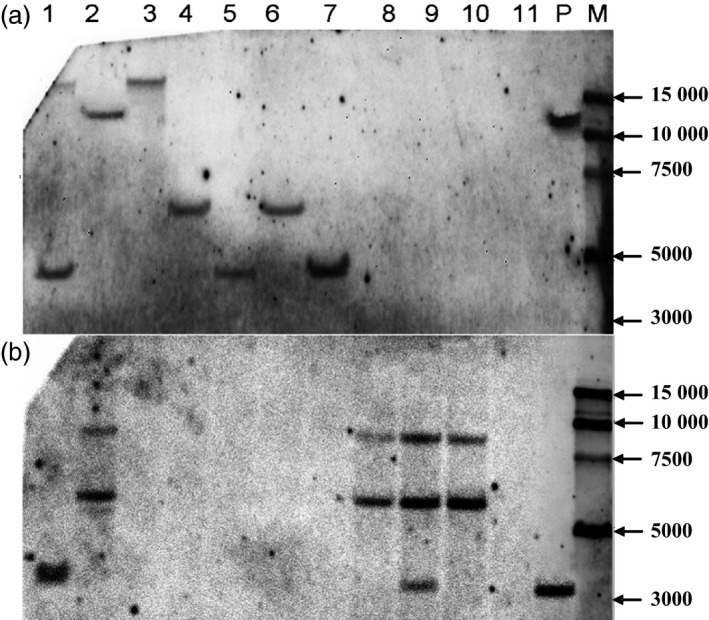

To obtain marker‐free transgenic wheat plants based on genotype screening, twelve T0 plants were randomly chosen from the 117 plants that tested positive for both the gus and bar genes, and progeny from these plants were grown in a greenhouse. At the booting stage, every T1 plant was tested for the presence and expression of the gus and bar genes by PCR, gus staining and Quickstix strips. Four types of transgenic plants were detected by PCR in the T1 generation: gus+bar+, gus+bar−, gus−bar+ and gus−bar− (Figure 4). Most of the T1 plants were gus+bar+, whereas there were very few marker‐free plants gus+bar− (Table 3). To confirm these results, some plants of each of the four types were selected for Southern blot analysis. According to PCR (Figure 4) and Southern blot analysis (Figure 5), marker‐free plants (gus+bar−) were identified in the T1 generation of three transgenic lines: KC2 from the KC hybrid, X2 from Xinchun9 and J1 from Jimai5265 with an efficiency of 40.0%, 9.5% and 7.5% (Table 3), respectively.

Figure 4.

PCR detection of the gus (a) and bar (b) genes for the screening of marker‐free transgenic plants in the T1 generation. 1‐14: individual T1 plants (1, X2‐1 from Xinchun9, gus+bar+; 2, X2‐3 from Xinchun9, gus+bar+; 3, KC2‐1 from the KC hybrid, gus+bar+; 4, KC2‐3 from the KC hybrid, gus+bar+; 5, J1‐5 from Jimai5265, gus+bar+; 6, KC2‐4 from the KC hybrid, gus+bar−; 7, KC2‐5 from the KC hybrid, gus+bar−; 8, KC2‐6 from the KC hybrid, gus+bar−; 9, X2‐4 from Xinchun9, gus+bar−; 10, C2‐1 from CB037, gus−bar+; 11, K3‐1 from Kenong199, gus−bar+; 12, C2‐2 from CB037, gus−bar+; 13, FC2‐1 from the FC hybrid, gus−bar−; 14, X2‐6 from Xinchun9, gus−bar−); P: expression vector pWMB123; WT: wild type Xinchun9; M: 2000 bp DNA marker.

Table 3.

Genotyping detection for the bar and gus genes in the selected T1 lines by PCR

| T0 events | T1 | P‐value | gus | bar | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gus+ bar+ | gus+ bar+ | gus+ bar‐ | gus− bar+ | gus− bar− | χ2 (9:3:3:1) | Presence | Absence | χ2 (3:1) | P‐value | Presence | Absence | χ2 (3:1) | P‐value | |

| X2 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3.47 | 0.33 | 18 | 3 | 1.29 | 0.26 | 18 | 3 | 1.29 | 0.26 |

| X3 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 11.97 | 0.01 | 14 | 3 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 14 | 3 | 0.49 | 0.48 |

| C1 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 4.44 | 0.22 | 10 | 6 | 1.33 | 0.25 | 15 | 1 | 3.00 | 0.08 |

| C2 | 8 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 6.45 | 0.09 | 8 | 7 | 3.76 | 0.05 | 14 | 1 | 2.69 | 0.10 |

| C3 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 6.69 | 0.08 | 12 | 3 | 0.20 | 0.65 | 13 | 2 | 1.09 | 0.30 |

| KC1 | 17 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 8.62 | 0.03 | 17 | 10 | 2.08 | 0.15 | 23 | 4 | 1.49 | 0.22 |

| KC2 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 5.74 | 0.12 | 14 | 1 | 2.69 | 0.10 | 9 | 6 | 1.80 | 0.18 |

| KC3 | 21 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 9.80 | 0.02 | 21 | 8 | 0.10 | 0.75 | 25 | 4 | 1.94 | 0.16 |

| KC4 | 10 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 5.69 | 0.13 | 10 | 7 | 2.37 | 0.12 | 16 | 1 | 3.31 | 0.07 |

| KC5 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3.55 | 0.31 | 10 | 3 | 0.03 | 0.87 | 12 | 1 | 2.08 | 0.15 |

| K3 | 15 | 0 | 10 | 9 | 31.57 | 0 | 15 | 19 | 17.30 | 0 | 25 | 9 | 0.04 | 0.84 |

| J1 | 19 | 3 | 15 | 3 | 10.84 | 0.01 | 22 | 18 | 8.53 | 0.01 | 34 | 6 | 2.13 | 0.14 |

| Total | 160 | 11 | 58 | 30 | 171 | 88 | 218 | 41 | ||||||

Transgenic T1 lines X2 and X3 are derived from Xinchun9; C1, C2 and C3 from CB037; KC1, KC2, KC3, KC4 and KC5 from the KC hybrid; K3 from Kenong199; J1 from Jimai5265.

Figure 5.

Southern blot detection of gus (a) and bar (b) genes for the identification of marker‐free transgenic hexaploid wheat plants in the T1 generation. 1‐11: different T1 individual plants (1, KC2‐1 from the KC hybrid, gus+bar+; 2, X2‐1 from Xinchun9, gus+bar+; 3, KC2‐2 from the KC hybrid, gus+bar−; 4, KC2‐3 from the KC hybrid, gus+bar ‐ ; 5, KC2‐4 from the KC hybrid, gus+bar−; 6, KC2‐5 from the KC hybrid, gus+bar−; 7, KC2‐6 from the KC hybrid, gus+bar−; 8, C2‐1 from CB037, gus−bar+; 9, K3‐1 from Kenong199, gus−bar+; 10, C2‐2 from CB037, gus−bar+; 11, FC2‐1 from the FC hybrid, gus−bar−); P: expression vector pWMB123; M: 15000 bp DNA marker.

Analysis of transgene silencing in T1 progeny

Based on the screening of twelve T1 populations for both the presence of the gus and bar transgenes and the expression levels of these transgenes, we found that the PCR detection of the gus gene corresponded well with the gus staining results, but PCR detection of the bar gene was inconsistent with Quickstix strip results. Among the 259 T1 plants tested, 171 gus‐positive plants and 218 bar‐positive plants were detected based on PCR (Table 3); 171 plants expressing gus were detected by histochemical staining (Table 4), but only 151 plants expressing the bar gene were detected by Quickstix strips. It was thus inferred that the gus gene is normally expressed in all of the gus‐positive T1 plants, whereas the bar gene was silenced in 30.7% of the bar‐positive T1 plants. In particular, bar gene‐silenced plants accounted for 72.2% and 66.7% of the bar‐positive plants from the X2 and C1 T1 populations, respectively (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 4.

Segregation analysis based on the detection of bar and gus gene expression in T1 lines using Quickstix strips and histochemical staining

| T1 line | Plants tested | gus+ bar+ | gus+ bar− | gus− bar+ | gus− bar− | Chi‐square probability value (bar) | Chi‐square probability value (gus) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X2 | 21 | 5 | 13 | 0 | 3 | 3:1 = 0 | 3:1 = 0.26 |

| X3 | 17 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3:1 = 0.48 | 3:1 = 0.48 |

| C1 | 16 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 6 | 3:1 = 0 | 3:1 = 0.25 |

| C2 | 15 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3:1 = 0.18 | 3:1 = 0.05 |

| C3 | 15 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3:1 = 0.30 | 3:1 = 0.65 |

| KC1 | 27 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 3:1 = 0 | 3:1 = 0.15 |

| KC2 | 15 | 8 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 3:1 = 0.05 | 3:1 = 0.10 |

| KC3 | 29 | 21 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 3:1 = 0.91 | 3:1 = 0.75 |

| KC4 | 17 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 3:1 = 0.008 | 3:1 = 0.12 |

| KC5 | 13 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3:1 = 0.42 | 3:1 = 0.87 |

| K3 | 34 | 11 | 4 | 10 | 9 | 3:1 = 0.07 | 3:1 = 0 |

| J1 | 40 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 4 | 3:1 = 0.03 | 3:1 = 0.003 |

| Total | 259 | 110 | 61 | 41 | 47 | NA | NA |

Transgenic T1 lines X2 and X3 are derived from Xinchun9; C1, C2 and C3 are derived from CB037; KC1, KC2, KC3, KC4 and KC5 are derived from the KC hybrid; K3 are derived from Kenong199; J1 are derived from Jimai5265.

To understand the mechanism of bar gene silencing in the transgenic wheat plants in this study, we first sequenced the bar gene in bar gene‐silenced plants. We did not observe any sequence changes indicating that silencing is not due to mutation of the bar gene. We next evaluated the expression of the bar gene in bar gene‐silenced plants by RT‐PCR. We could not detect bar mRNA (Figure S3), indicating that the bar gene is not expressed at the mRNA level in the bar‐silenced plants, likely due to transcriptional gene silencing. Thus, we postulated that the bar gene silencing in our study might result from DNA methylation.

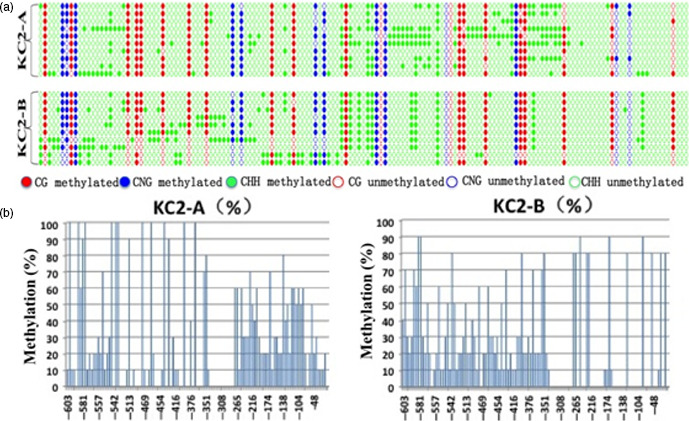

Methylation analysis of the 35S promoter region in bar gene‐silenced plants

One bar‐expressing plant and one bar‐silenced plant from the T2 generation of the KC2‐1 line were chosen for the evaluation of methylation by bisulphite sequencing. The methylation frequency in the 35S promoter region controlling bar gene expression in the bar‐silenced plant was obviously higher than that in the bar‐expressing plant (Figure 6). The important sites where methylation may result in bar silencing are listed in Table S1. There are 11 sites that have a greater than 50% difference in methylation frequency between the bar‐silenced and bar‐expressing plants (Table S1). Of particular note, the −138 position displayed the largest difference, with a methylation frequency of 80% in the bar‐silenced plant and no methylation at all in the bar‐expressing plant. The methylation of this site may be a key cause of bar gene silencing in the KC2‐1 transgenic wheat plants obtained in this study.

Figure 6.

Bisulphite sequencing analysis of the DNA methylation level in the 35S promoter region of bar‐expressing and bar‐silenced plants. KC2‐A: bar‐silenced plants; KC2‐B: bar‐expressing plants.

Discussion

Transformation ability of commercial Chinese hexaploid wheat cultivars

Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation of wheat using immature embryos is known to be strongly genotype dependent. In the past 20 years, transgenic wheat plants were mostly obtained from a few model spring‐type genotypes such as Bobwhite and the Veery (Cheng et al., 1997; Khanna and Daggard, 2003). Using the PureWheat technique, another model spring wheat genotype, Fielder, was successfully transformed (Ishida et al., 2015). Recently, Richardson et al. (2014) achieved Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation of eight Australian and Mexican commercial spring wheat varieties, among which Westonia and Gladius showed effective transformation efficiencies. Zhang et al. (2015) transformed 10 commercial Chinese wheat varieties by biolistic‐mediated transformation of immature embryos, immature embryo calluses and mature embryo calluses. They obtained transgenic plants from most of the tested wheat varieties, with average efficiencies of 5.15% for immature embryos, 2.26% for immature embryo calluses and 1.89% for mature embryo calluses. Among the 10 varieties tested, three spring or facultative genotypes (Longchun23, Yangmai19 and Kenong199) had transformation efficiencies greater than 7% when immature embryos were used as explants.

In the present investigation, 17 commercial Chinese hexaploid wheat varieties were transformed with Agrobacterium, and transgenic wheat plants were generated from 15 of the 17 varieties. One winter cultivar, Jingdong18; two spring cultivars, CB037 and Xingchun9; and six facultative cultivars, including Kenong199, Jimai5265, Zhoumai18, Neimai836, Zhengmai7698 and Yangmai16, were found to have good transformability by Agrobacterium (Table 1). Combined with the previous results of Zhang et al. (2015), it seems clear that most commercial Chinese wheat varieties can be successfully transformed by Agrobacterium or bombardment approaches, and some varieties (such as CB037, Xingchun9, Kenong199, Jimai5265 and Yangmai19) can be potentially used in wheat transgenic breeding or functional genomics studies, owing to their high transformation efficiencies. It should be noted that spring and facultative wheat varieties generally display higher transformation efficiencies than winter wheat varieties. The establishment of an efficient Agrobacterium‐mediated wheat transformation system using immature embryos will enable genome editing of genes controlling important traits by techniques such as CRISPR/Cas9 (Wang et al., 2014; Ye, 2015).

Overcoming transformation recalcitrance in commercial wheat varieties

In this investigation, an efficient Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation protocol was developed for 15 commercial Chinese wheat varieties, but some varieties remain difficult to transform; these varieties include Jimai22, Jing411 and AK58. We found that the transformation efficiency for recalcitrant commercial wheat varieties could be improved by crossing them with the more‐easily‐transformed varieties. Four F1 wheat hybrids derived from crosses between varieties with different transformation efficiencies had elevated transformation efficiencies compared to their recalcitrant parents (Table 2). Application of F1 hybrids could alleviate the difficulty in transforming recalcitrant commercial wheat varieties. This strategy, which involves first obtaining transgenic plants from F1 hybrids between model genotypes with high transformation efficiencies and commercial wheat varieties with low transformation efficiencies, and then backcrossing the transgenic plants with the commercial varieties for several generations while using molecular markers to select for the target transgenes, might be more efficient than traditionally used breeding methods, which includes first obtaining stable transgenic lines using model genotypes with high transformation efficiencies, and then crossing these lines followed several generations backcrossing with commercial varieties in combination with the tracing of the target transgenes.

Efficient generation of marker‐free transgenic hexaploid wheat plants

To date, transgenic wheat has not been approved for commercial release, although the development of transgenic wheat plants with various trait enhancements has been reported extensively (Harwood, 2012; Li et al., 2012). Several transgenic wheat lines have been evaluated in the field for herbicide resistance (Zhou et al., 2003), disease resistance (Chen et al., 2014), yield (Chen et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2003), gene flow (Dong et al., 2016; Rieben et al., 2011), interactions between transgenes and the environment (Dong et al., 2016; Zeller et al., 2010) and effects on microbial community diversity and the impact of enzyme activity on soil (Wu et al., 2014). It seems likely that the elimination of selection markers and unnecessary vector backbone DNA in early generations will be helpful in overcoming biosafety limitations and in allowing environmental release of genetically modified wheat (Wang et al., 2016).

Marker‐free transgenic wheat plants have been obtained using minimal gene expression cassettes and a cold‐inducible Cre/lox system introduced by biolistic particles (Mészáros et al., 2015; Yao et al., 2007), as well as via Agrobacterium‐mediated methods that employ no selection regime (Richardson et al., 2014). Using a co‐transformation technique mediated by Agrobacterium, a higher frequency of marker‐free plants was acquired in model plants like tobacco and rice (McCormac et al., 2001; Rao et al., 2011). However, although Agrobacterium‐mediated co‐transformation of two T‐DNAs is known as a reliable and efficient strategy to obtain marker‐free transgenic plants, use of this method has only been reported durum wheat (Wang et al., 2016) and not yet in hexaploid wheat. In this study on the generation of marker‐free hexaploid wheat transgenic plants by co‐transformation, the average co‐integration frequency of the gus and bar genes in T0 plants was 49.0% (ranging from 38.5% to 66.7%), which is consistent with the results obtained for other plant species (Lu et al., 2009; Rao et al., 2011). Eleven transgenic wheat plants with the target gene and without the selection marker (gus+bar−) were screened from three T1 populations, KC2, X2 and J1. Among 12 T1 populations or 259 T1 plants in total, the average frequency of obtaining marker‐free lines was 4.3% (Table 3). In the three transgenic T1 lines, KC2, X2 and J1, the frequency of marker‐free plants obtained was 40%, 14.3% and 7.5%, respectively. Notably, there was only one to two copies of the bar gene in these T1 lines. However, marker‐free plants were not obtained from T1 plants with multiple copies of the bar gene. Therefore, we speculate that the integration copy number of the bar gene is perhaps closely related to the efficiency of obtaining marker‐free plants. It appears that marker‐free transgenic plants are relatively easily obtained only for the offspring of T0 plants with a single or a few copies of the bar gene. Potential reasons for why we were unsuccessful in obtaining gus+bar− plants for the other nine T1 populations include: (1) the T1 population for each line was not large enough and (2) there were more than three copies of the bar gene integrated into the genomes of these nine T0 plants. Typically, transgenic plants with a single gene copy are selected for functional analysis. In Agrobacterium‐mediated co‐transformation experiments, the transgenic plants with a single copy of the selection gene and a single copy of target gene are ideal materials to produce marker‐free plants in the segregation generations at a theoretical rate of 18.75%. For this purpose, the number of copies of the selection marker and of the target gene should be determined in plants of the T0 generation.

In the expression vector pWMB123 used in this study, the T‐DNA region containing the bar gene was 1.7 kb in length, but the other T‐DNA region containing the gus gene was 4.4 kb in length, which is more than two times greater (Figure 1). The unmatched size of the two T‐DNAs may have led to more copies of the bar gene than the gus gene being integrated into the wheat genome (Figure 3). A previous study reported that different size of the two T‐DNA cassettes in a vector resulted in their different integration copy numbers in transgenic tobacco (McCormac et al., 2001). Based on our results, we supposed that the shorter bar gene cassette has a higher chance of being inherited via independent assortment in the T1 generation. Therefore, decreased bar gene integration could be achieved by changing the sizes of the two independent T‐DNA regions in the binary vector to an optimal ratio, by which the rate of successful generation of marker‐free plants would be further improved.

Possible ways to reduce transgene silencing

In a previous study, marker‐free soya bean plants were obtained at a low frequency using an expression vector containing three independent T‐DNAs including two 3.7 kb target gene cassettes and one 2.5 kb bar gene cassette; the bar gene was found to be silenced in many positive T1 plants (Ye and Qin, 2008). In the present study, among the 218 bar gene‐positive T1 plants, 67 plants exhibited bar gene silencing (30.7%). However, the gus gene was not silenced in any of the positive T1 plants (Tables 3 and 4).

Gene silencing typically acts in a regional, rather than in a promoter‐ or sequence‐specific manner and generates large domains of DNA that are inaccessible to DNA binding proteins. Anandalakshmi et al. (1998) reported two major mechanistic classes for gene silencing: transcriptional gene silencing (TGS) and post‐transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS). In our bar gene‐silenced transgenic wheat plants, mRNA expression analysis did not detect the expression of the bar gene. We hypothesize that DNA methylation may be responsible for the bar gene silencing. In fact, gene silencing in transgenic plants caused by methylation in the 35S promoter region has been described recently (Okumura et al., 2016; Yamasaki et al., 2011). In the present experiment, bisulphite sequencing was used to reveal the reasons for bar gene silencing. The results indicated that bar gene silencing in our transgenic wheat plants was in fact due to DNA methylation of the 35S promoter region, especially the methylation of the cytosine at −138 position. One reason might be that the 35S promoter is easily methylated. In a recently published study, no silencing of the bar gene expressed under the control of the ubiquitin promoter in transgenic durum wheat plants was reported (Wang et al., 2016). Hence, to alleviate gene silencing in transgenic hexaploid wheat and to efficiently generate marker‐free plants in the T1 generation, we propose using other strong promoters (such as ubiquitin and actin) and adjusting the size of the T‐DNA region harbouring the selection gene to reduce the number of copies of the selection gene integrated into the genome.

Experimental procedures

Plant materials

Hexaploid wheat genotypes used in this study included spring varieties, including CB037, Xinchun9 and Fielder, and facultative or winter varieties, including AK58, Jimai22, Neimai836, Zhengmai7698, Chuanmai42, Zhoumai18, Shiluan02‐1. Kenong199, Shi4185, Jimai5265, Yangmai16, Lunxuan987, Jing411, Jingdong18 and Zhongmai895. CB037 was developed and kindly provided by Prof. Xiao Chen from Institute of Crop Science, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Science (ICS‐CAAS). Zhongmai895 was developed and kindly provided by Prof. Binghua Liu from ICS‐CAAS. Zhongmai895 was developed and kindly provided by Dr. Yong Zhang from ICS‐CAAS. Jimai5265 was developed and kindly provided by Prof. Hui Li at Institute of Cereal and Oil Crops of the Hebei Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences. The remaining wheat cultivars were acquired from the National Crop Germplasm Bank of ICS‐CAAS. Jimai22 is the number one wheat variety in China and is planted on 2 million hectares each year. Yangmai16 is the number one variety in southern China and is planted on 0.3 million hectares each year. The four F1 hybrids, Kenong199 × CB037 (KC), Kenong199 × Fielder (KF), Xinchun9 × Fielder (XF) and Jimai22 × Fielder (JF), were developed previously by our research group.

The spring wheat varieties and the four F1 hybrids were directly sown in growth chambers. Winter wheat varieties were germinated in culture dishes (90 mm × 20 mm) at room temperature for 2 days and maintained in a cooler at 4 °C for 30 days for vernalization before sowing. All wheat cultivars were grown in pots (20 cm × 30 cm) filled with substrate peat moss (King Root, Latvia), mixed with patterned released fertilizer (Osmocote Extract, Germany) and maintained with an environmental growth condition regime of 24 °C, 16 h light/18 °C, 8 h dark with 300 μmol/m2/s light intensity at 45% humidity. During the growth period, water was supplied once a week. Aphids were controlled with sticky coloured cards (Zhengzhou Oukeqi Instruments Ltd., China); powdery mildew was controlled by application of triadimefon (Jinan Luba Pesticides Co., China).

Construction of an expression vector with two independent T‐DNA regions

The pZP201 and pPTN290 plasmids were kindly provided by Dr. Tom Clemente of the University of Nebraska‐Lincoln. Plasmids pWMB006 and pWMB010 were constructed previously in our laboratory. The construction of an expression vector with two independent T‐DNA regions was performed as follows: the pWMB006 and pZP201 plasmids were double digested with BamHI and EcoRI. The 806‐bp and 7121‐bp fragments were selected and then ligated together to form an intermediate vector, pZP201‐NOS. pZP201‐NOS and pWMB010 were digested with ScaI to release 7827‐bp and 3398‐bp fragments, respectively. These two fragments were ligated to form another intermediate vector, pZP201‐NOS‐bar. Next, pZP201‐NOS‐bar and pWMB006 were digested with PstI to release 11225‐bp and 1988‐bp fragments, respectively. The expression vector pWMB122 harbouring two independent T‐DNA regions was constructed by ligating these two fragments (Figure S1). Finally, the expression vector pWMB123 was constructed by ligating the 2077‐bp PCR product amplified from pPTN290 with the primers gus‐BamHI‐F: 5′‐AAAGGATCCATGGTAGATCTGAGGGTA‐3′ and gus‐SacI‐R: 5′‐AAAGAGCTCTCACCTGTAATTCACACGTGG‐3′ into pWMB122, which was double digested with BamHI and SacI.

Bacterial strains and triparental mating

Agrobacterium strain C58C1 and an E. coli strain containing the helper plasmid pRK2013 were kindly provided by Dr. Tom Clemente, of the University of Nebraska‐Lincoln. The pWMB123 expression vector was introduced into Agrobacterium strain C58C1 by triparental mating (Ditta et al., 1980).

Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation of wheat immature embryos

Wheat heads from plants grown in a growth chamber were tagged at anthesis and harvested 14 days postanthesis (DPA). In aseptic conditions, immature wheat grains were carefully collected, then surface sterilized with 70% ethanol for 1 min, with 5% sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) for 15 min, and finally rinsed 5 times with sterile water. We used a proprietary method for Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation of wheat developed by Japan Tobacco Company (Ishida et al., 2015) with slight modifications. In brief, immature wheat embryos were carefully taken from the sterilized grains aseptically under a stereoscopic microscope, incubated with Agrobacterium strain C58C1 harbouring pWMB123 for 5 min in WLS‐inf medium at room temperature, and co‐cultivated for 2 d on WLS‐AS medium, with the scutellum facing upwards, at 25 °C in darkness. After co‐cultivation, embryonic axes were removed with a scalpel and the scutella were transferred onto plates containing WLS‐Res medium. After 5 day, the tissues were transferred onto callus induction (WLS‐P5) medium. After 2 weeks, callus cultures were sliced vertically into halves and evenly placed on WLS‐P10 medium for 3 weeks in darkness. Embryogenic calli were then differentiated on LSZ‐P5 medium at 25 °C with 100 μmols/m2/s light. Regenerated shoots were transferred into cups filled with MSF‐P5 medium for elongation and root formation. Plantlets with well‐developed root systems were transplanted into pots and cultivated in growth chambers at 25 °C with 300 μmol/m2/s light.

Histochemical staining and Quickstix detection of transgenic wheat plants

Histochemical staining of gus expression was conducted as described by Jefferson et al. (1987). The transformed immature wheat embryos just after resting culture on WLS‐Res medium or the young leaves of putative transgenic wheat plants were immersed directly in X‐gluc staining buffer (0.1 m NaPO4 buffer pH 7.0, Na2‐EDTA 10 mm, ferricyanide 0.2 mm, ferrocyanide 0.2 mm, X‐gluc 0.8 g/L, methanol 20%, Triton X‐100 0.5%) and incubated overnight at 37 °C.

Putative transgenic wheat plants and their self‐pollinated offspring were identified based detection of the bar protein with the QuickStix Kit (EnviroLogix) for LibertyLink (the expressed protein of the bar selection marker gene), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

PCR‐based genotyping and Southern blot analysis of transgenic wheat plants

Genomic DNA was extracted from the leaves of the T0 and T1 transgenic plants using a NuClean PlantGen DNA kit (CWBIO, China). The presence of the gus gene in the transgenic plants was demonstrated by PCR amplification of a 995‐bp fragment using the primer pair 5′‐CAAGGAAATCCGCAACCATATC‐3′ and 5′‐TCAAACGTCCGAATCTTCTCCC‐3′. The presence of the bar gene in the transgenic plant samples was demonstrated by PCR amplification of a 429‐bp fragment using the primer pair 5′‐ACCATCGTCAACCACTACATCG‐3′ and 5′‐GCTGCCAGAAACCACGTCATG‐3′.

For Southern blotting analysis of transgenic wheat plants, total genomic DNA was extracted by employing a standard CTAB method (Sambrook et al., 1989) to obtain a larger amount of DNA; 10 μg DNA from each sample was digested with HindШ because there is only one cutting site for this enzyme adjacent to the RB sequence of the T‐DNA cassettes for the gus gene and the bar gene on the expression vector pWMB123 (Figure 1). The digested DNA samples were fractionated on a 0.8% agarose gel and transferred onto a nylon Hybond‐N+ membrane (Roche, Germany) with a membrane transfer instrument (Model 785, Bio‐Rad). The gus (995‐bp) and bar (429‐bp) PCR products were labelled with Digoxigenin and used as probes to hybridize with the digested DNA on the membrane. The hybridization and detection steps were performed according to the instructions for the DIG High Prime DNA Labeling and Detection Starter Kit II (Roche, Germany).

Bisulphite sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from transgenic wheat seedlings using a NuClean PlantGen DNA Kit (CWBIO, China). Bisulphite treatment of genomic DNA was conducted using a Methylation Gold Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (ZYMO Research Corporation). The bisulphite‐treated DNA was then subjected to PCR amplification using Hot‐Start Taq DNA polymerase (R110A, TaKaRa), using the primers listed in Table S2. Sequenced data were analysed using KISMETH (Gruntman et al., 2008). At least 10 independent clones from each PCR product were sequenced.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Construction of pWMB122, which contains two independent T‐DNA regions.

Figure S2. Transient gus expression in the immature embryos of various commercial Chinese hexaploid wheat varieties after 5 days of co‐cultivation with Agrobacterium harboring pWMB123.

Figure S3. RT‐PCR analysis of bar gene expression in the KC2‐1 transgenic line. Lanes 1‐7: The bar‐expressed plants tested by Quickstix strips; Lanes 8‐14: The bar‐silenced plants tested by Quickstix strips; Lane 15: Plasmid pWMB123; Lane 16: Kenong199; Lane17: DL2000 marker.

Table S1. Comparison of methylation frequencies at candidate methylation sites in the bar gene‐silenced plant KC2‐A and the bar gene‐expressing plant KC2‐B.

Table S2. Primers used for DNA methylation analysis.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Tom Clemente at the University of Nebraska‐Lincoln for kindly providing the pZP201 and pPTN290 plasmids, Agrobacterium strain C58C1 and the helper plasmid pRK2013. In addition, we would like to acknowledge Japan Tobacco laboratories for their invaluable training on the PureWheat transformation technique, which enabled us to rapidly establish this system in our laboratory. This research was financially supported by the Ministry of Agriculture of China (2014ZX08010‐004).

References

- Anandalakshmi, R. , Pruss, G.J. , Ge, X. , Marathe, R. , Mallory, A.C. , Smith, T.H. and Vance, V.B. (1998) A viral suppressor of gene silencing in plants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 13079–13084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla, P.L. (2006) Genetic engineering of wheat–current challenges and opportunities. Trends Biotechnol. 24, 305–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M. , Sun, L. , Wu, H. , Chen, J. , Ma, Y. , Zhang, X. , Du, L. et al. (2014) Durable field resistance to wheat yellow mosaic virus in transgenic wheat containing the antisense virus polymerase gene. Plant Biotechnol. J. 12, 447–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, M. , Fry, J.E. , Pang, S. , Zhou, H. , Hironaka, C.M. , Duncan, D.R. , Conner, T.W. et al. (1997) Genetic transformation of wheat mediated by agrobacterium tumefaciens. Plant Physiol. 115, 971–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditta, G. , Stanfield, S. , Corbin, D. and Helinski, D.R. (1980) Broad host range DNA cloning system for gram‐negative bacteria: construction of a gene bank of Rhizobium meliloti. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 77, 7347–7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, S. , Liu, Y. , Yu, C. , Zhang, Z. , Chen, M. and Wang, C. (2016) Investigating pollen and gene flow of WYMV‐resistant transgenic wheat N12‐1 using a dwarf male‐sterile line as the pollen receptor. PLoS ONE, 11, e0151373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Godfray, H.C. , Beddington, J.R. , Crute, I.R. , Haddad, L. , Lawrence, D. , Muir, J.F. , Pretty, J. et al. (2010) Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science, 327, 812–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruntman, E. , Qi, Y. , Slotkin, R.K. , Roeder, T. , Martienssen, R.A. and Sachidanandam, R. (2008) Kismeth: analyzer of plant methylation states through bisulfite sequencing. BMC Bioinformatics, 9, 371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood, W.A. (2012) Advances and remaining challenges in the transformation of barley and wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 1791–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.H. , Xia, X.C. , Chen, X.M. and Zhang, Q.S. (2011) Progress of wheat breeding in China and the future perspective. Acta Agro. Sin. 37, 202–215. [Google Scholar]

- Ishida, Y. , Tsunashima, M. , Hiei, Y. and Komari, Y . (2015) Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) transformation using immature embryos. In Agrobacterium Protocols: Volume 1. Methods in Molecular Biology, vol. 1223 ( Wang, K. , ed), pp. 189–198. New York: Springer Science+Business Media. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James, C . (2016) Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops: 2015. ISAAA Brief No. 50, Ithaca, NY: ISAAA. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson, R.A. , Kavanagh, T.A. and Bevan, M.W. (1987) GUS fusions: beta‐glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO J. 6, 3901–3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, R.S. , Nakamura, I. and Mii, M. (2011) Development of disease‐resistant marker‐free tomato by R/RS site‐specific recombination. Plant Cell Rep. 30, 1041–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, H.K. and Daggard, G.E. (2003) Agrobacterium tumefaciens‐mediated transformation of wheat using a superbinary vector and a polyamine‐supplemented regeneration medium. Plant Cell Rep. 21, 429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. , Xing, A. , Moon, B.P. , Burgoyne, S.A. , Guida, A.D. , Liang, H. , Lee, C. et al. (2007) A Cre/loxP‐mediated self‐activating gene excision system to produce marker gene free transgenic soybean plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 65, 329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. , Ye, X. , An, B. , Du, L. and Xu, H. (2012) Genetic transformation of wheat: current status and future prospects. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 6, 183–193. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, U. , Wu, X.R. , Yin, X.Y. , Morrand, J. , Chen, X.L. , Folk, W.R. and Zhang, Z.J. (2009) Development of marker‐free transgenic sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] using standard binary vectors with bar as a selectable marker. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ. Cult. 99, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- McCormac, A.C. , Fowler, M.R. , Chen, D.F. and Elliott, M.C. (2001) Efficient co‐transformation of Nicotiana tabacum by two independent T‐DNAs, the effect of T‐DNA size and implications for genetic separation. Transgenic Res. 10, 143–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mészáros, K. , Éva, C. , Kiss, T. , Bányai, J. and Kiss, E. (2015) Generating marker‐free transgenic wheat using minimal gene cassette and cold‐inducible cre/lox system. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 33, 1221–1231. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M. , Tagliani, L. , Wang, N. , Berka, B. , Bidney, D. and Zhao, Z.Y. (2002) High efficiency transgene segregation in co‐transformed maize plants using an Agrobacterium tumefaciens 2 T‐DNA binary system. Transgenic Res. 11, 381–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlynarova, L. and Nap, J.P. (2003) A self‐excising Cre recombinase allows efficient recombination of multiple ectopic heterospecific lox sites in transgenic tobacco. Transgenic Res. 12, 45–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moravcikova, J. , Vaculkova, E. , Bauer, M. and Libantova, J. (2008) Feasibility of the seed specific cruciferin C promoter in the self excision Cre/loxP strategy focused on generation of marker‐free transgenic plants. Theor. Appl. Genet. 117, 1325–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandy, S. and Srivastava, V. (2011) Site‐specific gene integration in rice genome mediated by the FLP‐FRT recombination system. Plant Biotechnol. J. 9, 713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanto, K. and Ebinuma, H. (2008) Marker‐free site‐specific integration plants. Transgenic Res. 17, 337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura, A. , Shimada, A. , Yamasaki, S. , Horino, T. , Iwata, Y. , Koizumi, N. , Nishihara, M. et al. (2016) CaMV‐35S promoter sequence‐specific DNA methylation in lettuce. Plant Cell Rep. 35, 43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao, M.V.R. , Parameswari, C. , Sripriya, R. and Veluthambi, K. (2011) Transgene stacking and marker elimination in transgenic rice by sequential Agrobacterium‐mediated co‐transformation with the same selectable marker gene. Plant Cell Rep. 30, 1241–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, T. , Thistleton, J. , Higgins, T.J. , Howitt, C. and Ayliffe, M. (2014) Efficient Agrobacterium transformation of elite wheat germplasm without selection. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ. Cult. 119, 647–659. [Google Scholar]

- Rieben, S. , Kalinina, O. , Schmid, B. and Zeller, S.L. (2011) Gene flow in genetically modified wheat. PLoS ONE, 6, e29730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J. , Fritsch, E.F. and Maniatis, T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd ed.. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shewry, P.R. (2009) Wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 1537–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tester, M. and Langridge, P. (2010) Breeding technologies to increase crop production in a changing world. Science, 327, 818–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuteja, N. , Verma, S. , Sahoo, R.K. , Raveendar, S. and Reddy, I.N. (2012) Recent advances in development of marker‐free transgenic plants: regulation and biosafety concern. J. Biosci. 37, 167–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. , Cheng, X. , Shan, Q. , Zhang, Y. , Liu, J. , Gao, C. and Qiu, J.L. (2014) Simultaneous editing of three homoeoalleles in hexaploid bread wheat confers heritable resistance to powdery mildew. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 947–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.P. , Yu, X.D. , Sun, Y.W. , Jones, H.D. and Xia, L.Q. (2016) Generation of marker‐and/or backbone‐free transgenic wheat plants via Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation. Front Plant Sci. 7, 1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J. , Yu, M. , Xu, J. , Du, J. , Ji, F. , Dong, F. , Li, X. et al. (2014) Impact of transgenic wheat with wheat yellow mosaic virus resistance on microbial community diversity and enzyme activity in rhizosphere soil. PLoS ONE, 9, e98394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing, A. , Zhang, Z. , Sato, S. , Staswick, P. and Clement, T. (2000) The use of two T‐DNA binary system to derive marker‐free transgenic soybeans. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Plant, 36, 456–463. [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki, S. , Oda, M. , Koizumi, N. , Mitsukuri, K. , Johkan, M. , Nakatsuka, T. , Nishihara, M. et al. (2011) De novo DNA methylation of the 35S enhancer revealed by high‐resolution methylation analysis of an entire T‐DNA segment in transgenic gentian. Plant Biotechnol. 28, 223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Q. , Cong, L. , He, G. , Chang, J. , Li, K. and Yang, G. (2007) Optimization of wheat co‐transformation procedure with gene cassettes resulted in an improvement in transformation frequency. Mol. Biol. Rep. 34, 61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X.G. (2015) Development and application of plant transformation techniques. J. Integrative Agri. 14, 411–413. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X.G. and Qin, H. (2008) Obtaining marker‐free transgenic soybean plants with optimal frequency by constructing a three T‐DNA binary vector. Front. Agric. China, 2, 156–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller, S.L. , Kalinina, O. , Brunner, S. , Keller, B. and Schmid, B. (2010) Transgene × environment interactions in genetically modified wheat. PLoS ONE, 5, e11405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K. , Liu, J. , Zhang, Y. , Yang, Z. and Gao, C. (2015) Biolistic genetic transformation of a wide range of Chinese elite wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) varieties. J. Genet. Genomics, 42, 39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H. , Berg, J.D. , Blank, S.E. , Chay, C.A. , Chen, G. , Eskelsen, S.R. , Fry, J.E. et al. (2003) Field efficacy assessment of transgenic roundup ready wheat. Crop Sci. 43, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Construction of pWMB122, which contains two independent T‐DNA regions.

Figure S2. Transient gus expression in the immature embryos of various commercial Chinese hexaploid wheat varieties after 5 days of co‐cultivation with Agrobacterium harboring pWMB123.

Figure S3. RT‐PCR analysis of bar gene expression in the KC2‐1 transgenic line. Lanes 1‐7: The bar‐expressed plants tested by Quickstix strips; Lanes 8‐14: The bar‐silenced plants tested by Quickstix strips; Lane 15: Plasmid pWMB123; Lane 16: Kenong199; Lane17: DL2000 marker.

Table S1. Comparison of methylation frequencies at candidate methylation sites in the bar gene‐silenced plant KC2‐A and the bar gene‐expressing plant KC2‐B.

Table S2. Primers used for DNA methylation analysis.