Abstract

We present a computer-aided programming approach to concurrency. The approach allows programmers to program assuming a friendly, non-preemptive scheduler, and our synthesis procedure inserts synchronization to ensure that the final program works even with a preemptive scheduler. The correctness specification is implicit, inferred from the non-preemptive behavior. Let us consider sequences of calls that the program makes to an external interface. The specification requires that any such sequence produced under a preemptive scheduler should be included in the set of sequences produced under a non-preemptive scheduler. We guarantee that our synthesis does not introduce deadlocks and that the synchronization inserted is optimal w.r.t. a given objective function. The solution is based on a finitary abstraction, an algorithm for bounded language inclusion modulo an independence relation, and generation of a set of global constraints over synchronization placements. Each model of the global constraints set corresponds to a correctness-ensuring synchronization placement. The placement that is optimal w.r.t. the given objective function is chosen as the synchronization solution. We apply the approach to device-driver programming, where the driver threads call the software interface of the device and the API provided by the operating system. Our experiments demonstrate that our synthesis method is precise and efficient. The implicit specification helped us find one concurrency bug previously missed when model-checking using an explicit, user-provided specification. We implemented objective functions for coarse-grained and fine-grained locking and observed that different synchronization placements are produced for our experiments, favoring a minimal number of synchronization operations or maximum concurrency, respectively.

Keywords: Synthesis, Concurrency, NFA language inclusion, MaxSAT

Introduction

Programming for a concurrent shared-memory system, such as most common computing devices today, is notoriously difficult and error-prone. Program synthesis for concurrency aims to mitigate this complexity by synthesizing synchronization code automatically [5, 6, 9, 15]. However, specifying the programmer’s intent may be a challenge in itself. Declarative mechanisms, such as assertions, suffer from the drawback that it is difficult to ensure that the specification is complete and fully captures the programmer’s intent.

We propose a solution where the specification is implicit. We observe that a core difficulty in concurrent programming originates from the fact that the scheduler can preempt the execution of a thread at any time. We therefore give the developer the option to program assuming a friendly, non-preemptive, scheduler. Our tool automatically synthesizes synchronization code to ensure that every behavior of the program under preemptive scheduling is included in the set of behaviors produced under non-preemptive scheduling. Thus, we use the non-preemptive semantics as an implicit correctness specification.

The non-preemptive scheduling model (also known as cooperative scheduling [26]) can simplify the development of concurrent software, including operating system (OS) kernels, network servers, database systems, etc. [21, 22]. In the non-preemptive model, a thread can only be descheduled by voluntarily yielding control, e.g., by invoking a blocking operation. Synchronization primitives may be used for communication between threads, e.g., a producer thread may use a semaphore to notify the consumer about availability of data. However, one does not need to worry about protecting accesses to shared state: a series of memory accesses executes atomically as long as the scheduled thread does not yield.

A user evaluation by Sadowski and Yi [22] demonstrated that this model makes it easier for programmers to reason about and identify defects in concurrent code. There exist alternative implicit correctness specifications for concurrent programs. For example, for functional programs one can specify the final output of the sequential execution as the correct output. The synthesizer must then generate a concurrent program that is guaranteed to produce the same output as the sequential version [3]. This approach does not allow any form of thread coordination, e.g., threads cannot be arranged in a producer–consumer fashion. In addition, it is not applicable to reactive systems, such as device drivers, where threads are not required to terminate.

Another implicit specification technique is based on placing atomic sections in the source code of the program [14]. In the synthesized program the computation performed by an atomic section must appear atomic with respect to the rest of the program. Specifications based on atomic sections and specifications based on the non-preemptive scheduling model, used by our tool, can be easily expressed in terms of each other. For example, one can simulate atomic sections by placing statements before and after each atomic section, as well as around every instruction that does not belong to any atomic section.

We believe that, at least for systems code, specifications based on the non-preemptive scheduling model are easier to write and are less error-prone than atomic sections. Atomic sections are subject to syntactic constraints. Each section is marked by a pair of matching opening and closing statements, which in practice means that the section must start and end within the same program block. In contrast, a can be placed anywhere in the program.

Moreover, atomic sections restrict the use of thread synchronization primitives such as semaphores. An atomic section either executes in its entirety or not at all. In the former case, all wait conditions along the execution path through the atomic section must be simultaneously satisfied before the atomic section starts executing. In practice, to avoid deadlocks, one can only place a blocking instruction at the start of an atomic section. Combined with syntactic constraints discussed above, this restricts the use of thread coordination with atomic sections—a severe limitation for systems code where thread coordination is common. In contrast, synchronization primitives can be used freely under non-preemptive scheduling. Internally, they are modeled using s: for instance, a semaphore acquisition instruction is modeled by a followed by an statement that proceeds when the semaphore becomes available.

Lastly, our specification defaults to the safe choice of assuming everything needs to be atomic unless a statement is placed by the programmer. In contrast, code that uses atomic sections can be preempted at any point unless protected by an explicit atomic section.

In defining behavioral equivalence between preemptive and non-preemptive executions, we focus on externally observable program behaviors: two program executions are observationally equivalent if they generate the same sequences of calls to interfaces of interest. This approach facilitates modular synthesis where a module’s behavior is characterized in terms of its interaction with other modules. Given a multi-threaded program and a synthesized program obtained by adding synchronization to is preemption-safe w.r.t. if for each execution of under a preemptive scheduler, there is an observationally equivalent non-preemptive execution of . Our synthesis goal is to automatically generate a preemption-safe version of the input program.

We rely on abstraction to achieve efficient synthesis of multi-threaded programs. We propose a simple, data-oblivious abstraction inspired by an analysis of synchronization patterns in OS code, which tend to be independent of data values. The abstraction tracks types of accesses (read or write) to each memory location while ignoring their values. In addition, the abstraction tracks branching choices. Calls to an external interface are modeled as writes to a special memory location, with independent interfaces modeled as separate locations. To the best of our knowledge, our proposed abstraction is yet to be explored in the verification and synthesis literature. The abstract program is denoted as .

Two abstract program executions are observationally equivalent if they are equal modulo the classical independence relation I on memory accesses. This means that every sequence of observable actions is equivalent to a set of sequences of observable actions that are derived from by repeatedly commuting independent actions. Independent actions are accesses to different locations, and accesses to the same location iff they are both read accesses. Using this notion of equivalence, the notion of preemption-safety is extended to abstract programs.

Under abstraction, we model each thread as a nondeterministic finite automaton (NFA) over a finite alphabet, with each symbol corresponding to a read or a write to a particular variable. This enables us to construct NFAs , representing the abstraction of the original program under non-preemptive scheduling, and , representing the abstraction of the synthesized program under preemptive scheduling. We show that preemption-safety of w.r.t. is implied by preemption-safety of the abstract synthesized program w.r.t. the abstract original program , which, in turn, is implied by language inclusion modulo I of NFAs and . While the problem of language inclusion modulo an independence relation is undecidable [2], we show that the antichain-based algorithm for standard language inclusion [11] can be adapted to decide a bounded version of language inclusion modulo an independence relation.

Our synthesis works in a counterexample-guided inductive synthesis (CEGIS) loop that accumulates a set of global constraints. The loop starts with a counterexample obtained from the language inclusion check. A counterexample is a sequence of locations in such that their execution produce an observation sequence that is valid under the preemptive semantics, but not under the non-preemptive semantics. From the counterexample we infer mutual exclusion (mutex) constraints, which when enforced in the language inclusion check avoid returning the same counterexample again. We accumulate the mutex constraints from all counterexamples iteratively generated by the language inclusion check. Once the language inclusion check succeeds, we construct a set of global constraints using the accumulated mutex constraints and constraints for enforcing deadlock-freedom. This approach is the key difference to our previous work [4], where a greedy approach is employed that immediately places a lock to eliminate a bug. The greedy approach may result in a suboptimal lock placement with unnecessarily overlapping or nested locks.

The global approach allows us to use an objective function f to find an optimal lock placement w.r.t. f once all mutex constraints have been identified. Examples of objective functions include minimizing the number of statements (leading to coarse-grained locking) and maximizing concurrency (leading to fine-grained locking). We encode such an objective function, together with the global constraints, into a weighted maximum satisfiability (MaxSAT) problem, which is then solved using an off-the-shelf solver.

Since the synthesized lock placement is guaranteed not to introduce deadlocks our solution follows good programming practices with respect to locks: no double locking, no double unlocking and no locks locked at the end of the execution.

We implemented our synthesis procedure in a new prototype tool called Liss (Language Inclusion-based Synchronization Synthesis) and evaluated it on a series of device driver benchmarks, including an Ethernet driver for Linux and the synchronization skeleton of a USB-to-serial controller driver, as well as an in-memory key-value store server. First, Liss was able to detect and eliminate all but two known concurrency bugs in our examples; these included one bug that we previously missed when synthesizing from explicit specifications [6], due to a missing assertion. Second, our abstraction proved highly efficient: Liss runs an order of magnitude faster on the more complicated examples than our previous synthesis tool based on the CBMC model checker. Third, our coarse abstraction proved surprisingly precise for systems code: across all our benchmarks, we only encountered three program locations where manual abstraction refinement was needed to avoid the generation of unnecessary synchronization. Fourth, our tool finds a deadlock-free lock placement for both a fine-grained and a coarse-grained objective function. Overall, our evaluation strongly supports the use of the implicit specification approach based on non-preemptive scheduling semantics as well as the use of the data-oblivious abstraction to achieve practical synthesis for real-world systems code. With the two objective functions we implemented, Liss produces an optimal lock placements w.r.t. the objective.

Contributions First, we propose a new specification-free approach to synchronization synthesis. Given a program written assuming a friendly, non-preemptive scheduler, we automatically generate a preemption-safe version of the program without introducing deadlocks. Second, we introduce a novel abstraction scheme and use it to reduce preemption-safety to language inclusion modulo an independence relation. Third, we present the first language inclusion-based synchronization synthesis procedure and tool for concurrent programs. Our synthesis procedure includes a new algorithm for a bounded version of our inherently undecidable language inclusion problem. Fourth, we synthesize an optimal lock placement w.r.t. an objective function. Finally, we evaluate our synthesis procedure on several examples. To the best of our knowledge, Liss is the first synthesis tool capable of handling realistic (albeit simplified) device driver code, while previous tools were evaluated on small fragments of driver code or on manually extracted synchronization skeletons.

Related work

This work is an extension of our work that appeared in CAV 2015 [4]. We included a proof for Theorem 3 that shows that language inclusion is undecidable for our particular construction of automata and independence relation. Further, we introduced a set of global mutex constraints that replace the greedy approach of our previous work and enables optimal lock placement according to an objective function.

Synthesis of synchronization is an active research area [3, 5, 6, 8, 12, 15, 17, 23, 24]. Closest to our work is a recent paper by Bloem et al. [3], which uses implicit specifications for synchronization synthesis. While their specification is given by sequential behaviors, ours is given by non-preemptive behaviors. This makes our approach applicable to scenarios where threads need to communicate explicitly. Further, correctness in Bloem et al. [3] is determined by comparing values at the end of the execution. In contrast, we compare sequences of events, which serves as a more suitable specification for infinitely-looping reactive systems. Further, Khoshnood et al. developed ConcBugAssist [18], similar to our earlier paper [15], that employs a greedy loop to fix assertion violations in concurrent programs.

Our previous work [5, 6, 15] develops the trace-based synthesis algorithm. The input is a program with assertions in the code, which represent an explicit correctness specification. The algorithm proceeds in a loop where in each iteration a faulty trace is obtained using an external model checker. A trace is faulty if it violates the specification. The trace is subsequently generalized to a partial order [5, 6] or a formula over happens-before relations [15], both representing a set of faulty traces. A formula over happens-before relations is basically a disjunction of partial orders. In our earlier previous work [5, 6] the partial order is used to synthesize atomic sections and inner-thread reorderings of independent statements. In our later work [15] the happens-before formula is used to obtain locks, wait-signal statements, and barriers. The quality of the synthesized code heavily depends on how well the generalization steps works. Intuitively the more faulty traces are removed in one synthesis step the more general the solution is and the closer it is to the solution a human would have implemented.

The drawback of assertions as a specification is that it is hard to determine if a given set of assertions represents a complete specification. The current work does not rely on an external model-checker or an explicit specification. Here we are solving language inclusion, a computationally harder problem than reachability. However, due to our abstraction, our tool performs significantly better than tools from our previous work [5, 6], which are based on a mature model checker (CBMC [10]). Our abstraction is reminiscent of previously used abstractions that track reads and writes to individual locations (e.g., [1, 25]). However, our abstraction is novel as it additionally tracks some control-flow information (specifically, the branches taken) giving us higher precision with almost negligible computational cost. For the trace generalization and synthesis we use the technique from our previous work [15] to infer looks. Due to our choice of specification no other synchronization primitives are needed.

In Vechev et al. [24] the authors rely on assertions for synchronization synthesis and include iterative abstraction refinement in their framework. This is an interesting extension to pursue for our abstraction. In other related work, CFix [17] can detect and fix concurrency bugs by identifying simple bug patterns in the code.

The concepts of linearizability and serializability are very similar to our implicit specification. Linearizability [16] describes the illusion that every method of an object takes effect instantaneously at some point between the method call and return. A set of transactions is serializable [13, 20] if they produce the same result, whether scheduled in parallel or in sequential order.

There has been a body of work on using a non-preemptive (cooperative) scheduler as an implicit specification. The notion of cooperability was introduced by Yi and Flanagan [26]. They require the user to annotate the program with yield statements to indicate thread interference. Then their system verifies that the yield specification is complete meaning that every trace is cooperable. A preemptive trace is cooperable if it is equivalent to a trace under the cooperative scheduler.

Illustrative example

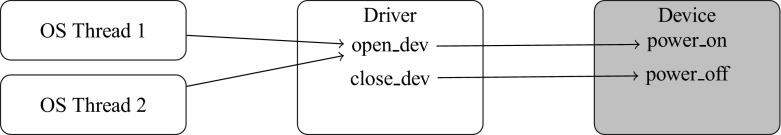

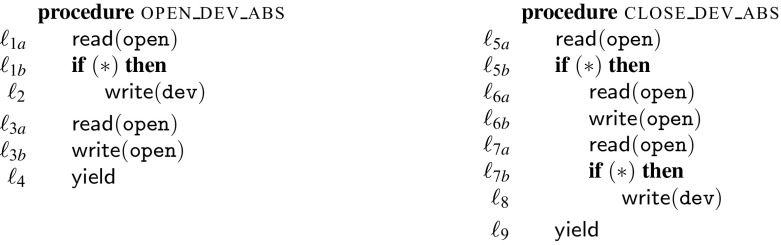

Figure 2 contains our running example, a part of a device driver. A driver interfaces the operating system with the hardware device (as illustrated in Fig. 1) and may be used by different threads of the operating system in parallel. An operating system thread wishing to use the device must first call the open_dev procedure and finally the close_dev procedure to indicate it no longer needs the device. The driver keeps track of the number of threads that interact with the device. The first thread to call open_dev will cause the driver to power up the device, the last thread to call close_dev will cause the driver to power down the device. The interaction between the driver and the device are represented as procedure calls in lines and . From the device’s perspective, the power-on and power-off signals alternate. In general, we must assume that it is not safe to send the power-on signal twice in a row to the device. If executed with the non-preemptive scheduler the code in Fig. 2 will produce a sequence of a power-on signal followed by a power-off signal followed by a power-on signal and so on.

Fig. 2.

Running example

Fig. 1.

Interaction of the device driver with the OS and the device

Consider the case where the procedure open_dev is called in parallel by two operating system threads that want to initiate usage of the device. Without additional synchronization, there could be two calls to power_up in a row when executing under a preemptive scheduler. Consider two threads ( and ) running the open_dev procedure. The corresponding trace is . This sequence is not observationally equivalent to any sequence that can be produced when executing with a non-preemptive scheduler.

Figure 3 contains the abstracted versions of the two procedures, open_dev_abs and close_dev_abs. For instance, the instruction is abstracted to the two instructions labeled and . The calls to the device (power_up and power_down) are abstracted as writes to a hypothetical variable. This expresses the fact that interactions with the device are never independent. The abstraction is coarse, but still captures the problem. Consider two threads ( and ) running the open_dev_abs procedure. The following trace is possible under a preemptive scheduler, but not under a non-preemptive scheduler: . Moreover, the trace cannot be transformed by swapping independent events into any trace possible under a non-preemptive scheduler. This is because instructions and are not independent. Further, is not independent with itself. Hence, the abstract trace exhibits the problem of two successive calls to power_up when executing with a preemptive scheduler. Our synthesis procedure finds this problem, and stores it as a mutex constraint: . Intuitively this constraint expresses the fact if one thread is executing any instruction between and no other thread may execute or .

Fig. 3.

Abstraction of the running example

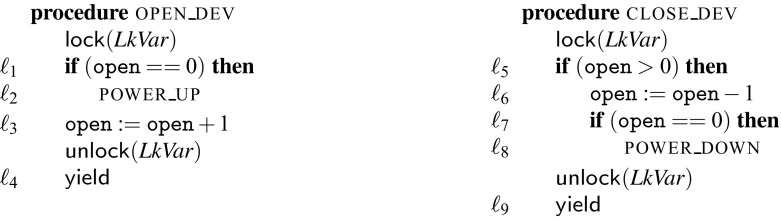

While this constraint ensures two parallel calls to open_dev behave correctly, two parallel calls to close_dev may result in the device receiving two power_down signals. This is represented by the concrete trace . The corresponding abstract trace is . This trace is not possible under a non-preemptive scheduler and cannot be transformed to a trace possible under a non-preemptive scheduler. This results in a second mutex constraint . With both mutex constraints the program is correct. Our lock placement procedure then encodes these constraints in SMT and the models of the SMT formula are all the correct lock placements. In Fig. 4 we show open_dev and close_dev with the inserted locks.

Fig. 4.

Running example with the synthesized locks

Formal framework and problem statement

We present the syntax and semantics of a concrete concurrent while language . For our solution strategy to be efficient we require an abstraction and we also introduce the syntax and semantics of the abstract concurrent while language . While (and our tool) permits non-recursive function call and return statements, we skip these constructs in the formalization below. We conclude the section by formalizing our notion of correctness for concrete concurrent programs.

Concrete concurrent programs

In our work, we assume a read or a write to a single shared variable executes atomically and further assume a sequentially consistent memory model.

Syntax of (Fig. 5)

Fig. 5.

Syntax of

A concurrent program is a finite collection of threads where each thread is a statement written in the syntax of . Variables in can be categorized into

shared variables ,

thread-local variables ,

lock variables ,

condition variables for wait-signal statements, and

guard variables for assumptions.

The and variables are also shared between all threads. All variables range over integers with the exception of guard variables that range over Booleans (). Each statement is labeled with a unique location identifier ; we denote by the statement labeled by .

The language includes standard sequential constructs, such as assignments, loops, conditionals, and statements. Additional statements control the interaction between threads, such as lock, wait-notify, and statements. In , we only permit expressions that read from at most one shared variable and assignments that either read from or write to exactly one shared variable.1 The language also includes , statements that operate on guard variables and become relevant later for our abstraction. The statement is in a sense an annotation as it has no effect on the actual program running under a preemptive scheduler. We still present it here because it has a semantic meaning under the non-preemptive scheduler.

Language has two statements that allow communication with an external system: reads from and writes to a communication channel . The channel is an interface between the program and an external system. The external system cannot observe the internal state of the program and only observes the information flow on the channel. In practice, we use the channels to model device registers. A device register is a special memory address, reading and writing from and to it is visible to the device. This is used to exchange information with a device. In our presentation, we assume all channels communicate with the same external system.

Semantics of

We first define the semantics of a single thread in , and then extend the definition to concurrent non-preemptive and preemptive semantics.

4.1.2.1 Single-thread semantics (Fig. 6)

Fig. 6.

Single-thread semantics of

Let us fix a thread identifier . We use interchangeably with the program it represents. A state of a single thread is given by where is a valuation of all program variables, and is a location identifier, indicating the statement in to be executed next. A thread is guaranteed not to read or write thread-local variables of other threads.

We define the flow graph for thread in a manner similar to the control-flow graph of . Every node of represents a single statement (basic blocks are not merged) and the node is labeled with the location of the statement. The flow graph has a unique entry node and a unique exit node. These two may coincide if the thread has no statements. The entry node is the first labeled statement in ; we denote its location identifier by . The exit node is a special node corresponding to a hypothetical statement placed at the end of .

We define successors of locations of using . The location last has no successors. We define if node in has exactly one outgoing edge to node . Nodes representing conditionals and loops have two outgoing edges. We define and if node in has exactly two outgoing edges to nodes and . Here represents the or the branch, whereas represents the or the branch.

We can now define the single-thread operational semantics. A single execution step changes the program state from to , while optionally outputting an observable symbol . The absence of a symbol is denoted using . In the following, represents an expression and evaluates an expression by replacing all variables v with their values in . We use to denote that variable v is set to k and all other variables in remain unchanged.

In Fig. 6, we present the rules for single execution steps. Each step is atomic, no interference can occur while the expressions in the premise are being evaluated. The only rules with an observable output are:

Havoc: Statement assigns shared variable a non-deterministic value (say k) and outputs the observable .

Input, Output: and read and write values to the channel , and output and , where k is the value read or written, respectively.

Intuitively, the observables record the sequence of non-deterministic guesses, as well as the input/output interaction with the tagged channels. The semantics of the synchronization statements shown in Fig. 6 is standard. The lock and unlock statements do not count and do not allow double (un)locking. There are no rules for and the sequence statement because they are already taken care of by the flow graph.

Concurrent semantics

A state of a concurrent program is given by where is a valuation of all program variables, is the thread identifier of the currently executing thread and are the locations of the statements to be executed next in threads to , respectively. There are two additional states: indicates the program has finished and indicates an assumption failed. Initially, all integer program variables and equal 0, all guard variable equal and for each . We introduce a non-preemptive and a preemptive semantics. The former is used as a specification of allowed executions, whereas the latter models concurrent sequentially consistent executions of the program.

4.1.3.1 Non-preemptive semantics (Fig. 7 ) The non-preemptive semantics ensures that a single thread from the program keeps executing using the single-thread semantics (Rule Seq) until one of the following occurs: (a) the thread finishes execution (Rule Thread_end) or (b) it encounters a , , or statement (Rule Nswitch). In these cases, a context-switch is possible, however, the new thread must not be blocked. We consider a thread blocked if its current instruction is to acquire an unavailable lock, waits for a condition that is not signaled, or the thread reached the location. Note the difference between / and /. The former allow for a context-switch while the latter transitions to the state if the assume is not fulfilled (rule Assume/Assume_not). A special rule exists for termination (Rule Terminate), which requires that all threads finished execution and also all locks are unlocked.

Fig. 7.

Non-preemptive semantics

4.1.3.2 Preemptive semantics (Figs. 7, 8 ) The preemptive semantics of a program is obtained from the non-preemptive semantics by relaxing the condition on context-switches, and allowing context-switches at all program points. In particular, the preemptive semantics consist of the rules of the non-preemptive semantics and the single rule Pswitch in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Additional rule for preemptive semantics

Abstract concurrent programs

The state of the concrete semantics contains unbounded integer variables, which may result in an infinite state space. We therefore introduce a simple, data-oblivious abstraction for concurrent programs written in communicating with an external system. The abstraction tracks types of accesses (read or write) to each memory location while abstracting away their values. Inputs/outputs to a channel are modeled as writes to a special memory location (). Even inputs are modeled as writes because in our applications we cannot assume that reads from the external interface are free of side-effects in the component on the other side of the interface. Havocs become ordinary writes to the variable they are assigned to. Every branch is taken non-deterministically and tracked. Given written in , we denote by the corresponding abstract program written in .

Abstract syntax (Fig. 9)

Fig. 9.

Syntax of

In the figure, denotes all shared program variables and the variable. The syntax of all synchronization primitives and the assumptions over guard variables remains unchanged. The purpose of the guard variables is to improve the precision of our otherwise coarse abstraction. Currently, they are inferred manually, but can presumably be inferred automatically using an iterative abstraction-refinement loop. In our current benchmarks, guard variables needed to be introduced in only three scenarios.

Abstraction function (Fig. 10)

Fig. 10.

Abstraction function from to

A thread in can be translated to using the abstraction function  . The abstraction replaces all global variable access with and and replaces branching conditions with nondeterminism (). All synchronization primitives remain unaffected by the abstraction. The abstraction may result in duplicate labels , which are replaced by fresh labels. statements are reordered accordingly. Our abstraction records branching choices (branch tagging). If one were to remove branch-tagging, the abstraction would be unsound. The justification and intuition for this can be found further below in Theorem 1. For example in our running example in Fig. 2 the abstraction of results in two abstract labels and in Fig. 3.

. The abstraction replaces all global variable access with and and replaces branching conditions with nondeterminism (). All synchronization primitives remain unaffected by the abstraction. The abstraction may result in duplicate labels , which are replaced by fresh labels. statements are reordered accordingly. Our abstraction records branching choices (branch tagging). If one were to remove branch-tagging, the abstraction would be unsound. The justification and intuition for this can be found further below in Theorem 1. For example in our running example in Fig. 2 the abstraction of results in two abstract labels and in Fig. 3.

Abstract semantics

As before, we first define the semantics of for a single-thread.

4.2.3.1 Single-thread semantics (Fig. 11)

Fig. 11.

Partial set of rules for single-thread semantics of

The abstract state of a single thread is given simply by where is a valuation of all lock, condition and guard variables and is the location of the statement in to be executed next. We define the flow graph and successors for locations in the abstract program in the same way as before. An abstract observable symbol is of the form: , where . The symbol records the type of access to variables along with the variable name and records non-deterministic branching choices . Fig. 11 presents the rules for statements unique to ; the rules for statements common to and are the same.

4.2.3.2 Concurrent semantics

A state of an abstract concurrent program is either , or is given by where is a valuation of all lock, condition and guard variables, is the current thread identifier and are the locations of the statements to be executed next in threads to , respectively. The non-preemptive and preemptive semantics of a concurrent program written in are defined in the same way as that of a concurrent program written in .

Program correctness and problem statement

Let denote the set of all concurrent programs in , respectively.

Executions

A non-preemptive/preemptive execution of a concurrent program in is an alternating sequence of program states and (possibly empty) observable symbols, , such that (a) is the initial state of , (b) , according to the non-preemptive/preemptive semantics of , we have , and (c) is the state . A non-preemptive/preemptive execution of a concurrent program in is defined in the same way, replacing the corresponding semantics of with that of .

Observable behaviors

Let be an execution of program in , then we denote with the sequence of non-empty observable symbols in . We use , resp. , to denote the non-preemptive, resp. preemptive, observable behavior of , that is all sequences of all executions under the non-preemptive, resp. preemptive, scheduling. The non-preemptive/preemptive observable behavior of program in , denoted /, is defined similarly.

We specify correctness of concurrent programs in using two implicit criteria, presented below.

Preemption-safety

Observable behaviors and of a program in are equivalent if: (a) the subsequences of and containing only symbols of the form and are equal and (b) for each thread identifier , the subsequences of and containing only symbols of the form are equal. Intuitively, observable behaviors are equivalent if they have the same interaction with the interface, and the same non-deterministic choices in each thread. For sets and of observable behaviors, we write to denote that each sequence in has an equivalent sequence in .

Given concurrent programs and in such that is obtained by adding locks to is preemption-safe w.r.t. if .

Deadlock-freedom

A state of concurrent program in is a deadlock state under non-preemptive/preemptive semantics if

The repeated application of the rules of the non-preemptive/preemptive semantics from the initial state of can lead to ,

,

, and

: according to the non-preemptive/preemptive semantics of .

Program in is deadlock-free under non-preemptive/preemptive semantics if no non-preemptive/preemptive execution of hits a deadlock state. In other words, every non-preemptive/preemptive execution of ends in state or . The state indicates an assumption did not hold, which we do not consider a deadlock. We say is deadlock-free if it is deadlock-free under both non-preemptive and preemptive semantics.

Problem statement

We are now ready to state our main problem, the optimal synchronization synthesis problem. We assume we are given a cost function f from a program to the cost of the lock placement solution, formally . Then, given a concurrent program in , the goal is to synthesize a new concurrent program in such that:

is obtained by adding locks to ,

is preemption-safe w.r.t. ,

has no deadlocks not present in , and,

Solution overview

Our solution framework (Fig. 12) consists of the following main components. We briefly describe each component below and then present them in more detail in subsequent sections.

Fig. 12.

Solution overview

Reduction of preemption-safety to language inclusion

To ensure tractability of checking preemption-safety, we build the abstract program from using the abstraction function described in Sect. 4.2. Under abstraction, we model each thread as a nondeterministic finite automaton (NFA) over a finite alphabet consisting of abstract observable symbols. This enables us to construct NFAs and accepting the languages and , respectively. We proceed to check if all words of are included in modulo an independence relation I that respects the equivalence of observables. We describe the reduction of preemption-safety to language inclusion and our language inclusion check procedure in Sect. 6.

Inference of mutex constraints from generalized counterexamples

If and do not satisfy language inclusion modulo I, then we obtain a counterexample . A counterexample is a sequence of locations an observation sequence that is in , but not in . We analyze to infer constraints on for eliminating . We use to denote the set of all permutations of the symbols in that are accepted by . Our counterexample analysis examines the set to obtain an hbformula —a Boolean combination of happens-before ordering constraints between events—representing all counterexamples in . Thus is generalized into a larger set of counterexamples represented as . From , we infer possible mutual exclusion (mutex) constraints on that can eliminate all counterexamples satisfying . We describe the procedure for finding constraints from in Sect. 7.1.

Automaton modification for enforcing mutex constraints

Once we have the mutex constraints inferred from a generalized counterexample, we enforce them in , effectively removing transitions from the automaton that violate the mutex constraint. This completes our loop and we repeat the language inclusion check of and . If another counterexample is found our loop continues, if the language inclusion check succeeds we proceed to the lock placement. This differs from the greedy approach employed in our previous work [4] that modifies and then constructs a new automaton from before restarting the language inclusion. The greedy approach inserts locks into that are never removed in a future iteration. This can lead to inefficient lock placement. For example a larger lock may be placed that completely surrounds an earlier placed lock.

Computation of an f-optimal lock placement

Once and satisfy language inclusion modulo I, we formulate global constraints over lock placements for ensuring correctness. These global constraints include all mutex constraints inferred over all iterations and constraints for enforcing deadlock-freedom. Any model of the global constraints corresponds to a lock placement that ensures program correctness. We describe the formulation of these global constraints in Sect. 8.

Given a cost function f, we compute a lock placement that satisfies the global constraints and is optimal w.r.t. f. We then synthesize the final output by inserting the computed lock placement in . We present various objective functions and describe the computation of their respective optimal solutions in Sect. 9.

Checking preemption-safety

Reduction of preemption-safety to language inclusion

Soundness of the abstraction

Formally, two observable behaviors and of an abstract program in are equivalent if:

For each thread , the subsequences of and containing only symbols of the form , for all a, are equal,

For each variable var, the subsequences of and containing only write symbols (of the form ) are equal, and

For each variable var, the multisets of symbols of the form between any two write symbols, as well as before the first write symbol and after the last write symbol are identical.

Using this notion of equivalence, the notion of preemption-safety is extended to abstract programs: Given abstract concurrent programs and in such that is obtained by adding locks to is preemption-safe w.r.t. if .

For the abstraction to be sound we require only that whenever preemption-safety does not hold for a program , then there must be a trace in its abstraction feasible under preemptive, but not under non-preemptive semantics.

To illustrate this we use the program in Fig. 13, which is not preemption-safe. To see this consider the observation that cannot occur in the non-preemptive semantics because x is always 0 at . Note that is unreachable because the variable y is initialized to 0 and never assigned. With the preemptive semantics the output can be observed if thread interrupts thread between lines and . An example trace would be .

Fig. 13.

Example showing how the abstraction works

If we consider the abstract semantics, we notice that under the non-preemptive abstract semantics is reachable because the abstraction makes the branching condition in non-deterministic. However, since our abstraction is sound there must still be an observation sequence that is observable under the abstract preemptive semantics, but not under the abstract non-preemptive semantics. This observation sequence is . The branch tagging records that the else branch is taken in . The non-preemptive semantics cannot produce this observation sequences because it must also take the branch in and can therefore not reach the statement and context-switch. As a site note, it is also not possible to transform this observation sequence into an equivalent one under the non-preemptive semantics because of the write to at and the accesses to in and .

This example illustrates why branch tagging is crucial to soundness of the abstraction. If we assume a hypothetical abstract semantics without branch tagging we would get the following preemptive observation sequence: . This sequence would also be a valid observation sequence under the non-preemptive semantics, because it could take the branch in and reach the statement and context-switch.

Theorem 1

(soundness) Given concurrent program and a synthesized program obtained by adding locks to .

Proof

It is easier to prove the contrapositive:  .

.

means that there is an observation sequence of with no equivalent observation sequence in . We now show that the abstract sequence in corresponding to the sequence has no equivalent sequence in .

means that there is an observation sequence of with no equivalent observation sequence in . We now show that the abstract sequence in corresponding to the sequence has no equivalent sequence in .

Towards contradiction we assume there is such an equivalent sequence in . We show that if indeed existed it would correspond to a concrete sequence that is equivalent to , thereby contradicting our assumption.

By (A1) would have the same control flow as because of the branch tagging. By (A2) and (A3) would have the same data-flow, meaning all reads from global variables are reading the values written by the same writes as in . Since all interactions with the environment are abstracted to the order of interactions must be the same between and . This means that, assuming all inputs and havocs are returning the same value, in the execution corresponding to all variables valuation are identical to those in . Therefore, is feasible and its interaction with the environment is identical to as all variable valuations are identical. Identical interaction with the environment is how equivalence between and is defined. This concludes our proof.

Language inclusion modulo an independence relation

We define the problem of language inclusion modulo an independence relation. Let I be a non-reflexive, symmetric binary relation over an alphabet . We refer to I as the independence relation and to elements of I as independent symbol pairs. We define a symmetric binary relation over words in : for all words and . Let denote the reflexive transitive closure of .2 Given a language over , the closure of w.r.t. I, denoted , is the set . Thus, consists of all words that can be obtained from some word in by repeatedly commuting adjacent independent symbol pairs from I.

Definition 1

(Language inclusion modulo an independence relation) Given NFAs A, B over a common alphabet and an independence relation I over , the language inclusion problem modulo I is: ?

Data independence relation

We define the data independence relation over our observable symbols. Two symbols and are independent, , iff (I0) and one of the following hold:

or in

and are both

is in and is in and

Checking preemption-safety

Under abstraction, we model each thread as a nondeterministic finite automaton (NFA) over a finite alphabet consisting of abstract observable symbols. This enables us to construct NFAs and accepting the languages and , respectively. is the abstract program corresponding to the input program and is the program corresponding to the result of the synthesis . It turns out that preemption-safety of w.r.t. is implied by preemption-safety of w.r.t. , which, in turn, is implied by language inclusion modulo of NFAs and . NFAs and satisfy language inclusion modulo if any word accepted by is equivalent to some word obtainable by repeatedly commuting adjacent independent symbol pairs in a word accepted by .

Proposition 1

Given concurrent programs and iff .

Proof

By construction , resp. , accept exactly the observation sequences that , resp. , may produce under the preemptive, resp. non-preemptive, semantics (denoted by , resp. ). It remains to show that two observation sequences and are equivalent iff .

We first show that implies is equivalent to . The proof proceeds by induction: The base case is that no symbols are swapped and is trivially true. The inductive case assumes that is equivalent to and we needs to show that after one single swap operation in , resulting in is equivalent to and therefore by transitivity also equivalent to . Rule (A1) holds because does not allow symbols of the same thread to be swapped (I0). To prove (A2) we use the fact that writes to the same variable cannot be swapped (I2), (I3). To prove (A3) we use the fact that reads and writes to the same variable are not independent (I2), (I3).

It remains to show that is equivalent to implies . Clearly and consist of the same multiset of symbols (A1). Therefore it is possible to transform into by swapping adjacent symbols. It remains to show that all swaps involve independent symbols. By (A1) the order of events in each thread does not change, therefore condition (I0) is always fulfilled. Branch tags can swap with every other symbol (I1) and accesses to different variables can swap with each other (I3). For each variables (A2) ensures that writes are in the same order and (A3) allows reads in between to be reordered. These swaps are allowed by (I2). No other swaps can occur.

Checking language inclusion

We first focus on the problem of language inclusion modulo an independence relation (Definition 1). This question corresponds to preemption-safety (Theorem 1, Proposition 1) and its solution drives our synchronization synthesis.

Theorem 2

For NFAs A, B over alphabet and a symmetric, irreflexive independence relation , the problem is undecidable [2].

We now show that this general undecidability result extends to our specific NFAs and independence relation .

Theorem 3

For NFAs and constructed from , the problem is undecidable.

Proof

Our proof is by reduction from the language inclusion modulo an independence relation problem (Definition 1). Theorem 3 follows from the undecidability of this problem (Theorem 2).

Assume we are given NFAs and and an independence relation . Without loss of generality we assume and to be deterministic, complete, and free of -transitions, meaning from every state there is exactly one transition for each symbol. We show that we can construct a program that is preemption-safe iff .

For our reduction we construct a program that simulates or if run with a preemptive scheduler and simulates only if run with a non-preemptive scheduler. Note that iff . For every symbol our simulator produces a sequence of abstract observable symbols. We say two such sequences and commute if , i.e, if can be obtained from by repeatedly swapping adjacent symbol pairs in .

We will show that (a) simulates or if run with a preemptive scheduler and simulates only if run with a non-preemptive scheduler, and (b) sequences and commute iff .

The simulator is shown in Fig. 14. States and symbols of and are mapped to natural numbers and represented as bitvectors to enable simulation using the language . In particular we use Boolean guard variables from to represent the bitvectors. We use to represent 1 and to represent 0. As the state space and the alphabet are finite we know the number of bits needed a priori. We use n, m, and p for the number of bits needed to represent , and , respectively. The transition functions and likewise work on the individual bits. We represent bitvector x of length n as .

Fig. 14.

Simulator algorithm

Thread simulates both automata A and B simultaneously. We assume the initial states of and are mapped to the number 0. In each iteration of the loop in thread a symbol is chosen non-deterministically and applied to both automata (we discuss this step in the next paragraph). Whether thread simulates or is decided only in the end: depending on the value of we assert that a final state of or was reached. The value of is assigned in thread and can only be if is preempted between locations and . With the non-preemptive scheduler the variable will always be because thread cannot be preempted. The simulator can only reach the state if all assumptions hold as otherwise it would end in the state. The guard will only be assigned in if either is and a final state of has been reached or if is and a final state of has been reached. Therefore the valid non-preemptive executions can only simulate . In the preemptive setting the simulator can simulate either or because can be either or . Note that the statement in location executes atomically and the value of cannot change during its evaluation. This means that simulates and simulates .

We use to store the symbol used by the transition function. The choice of the next symbol needs to be non-deterministic to enable simulation of and there is no havoc statement in . We therefore use the fact that the next thread to execute is chosen non-deterministically at a preemption point. We define a thread for every that assigns to the number maps to. Threads can only run if the conditional variable ch-sym is set to 1 by the statement in . The  in is a preemption point for the non-preemptive semantics. Then, exactly one thread can proceed because the

in is a preemption point for the non-preemptive semantics. Then, exactly one thread can proceed because the  statement in atomically resets ch-sym to 0. After setting and outputting the representation of thread , notifies thread using condition variable ch-sym-compl. Another symbol can only be produced in the next loop iteration of .

statement in atomically resets ch-sym to 0. After setting and outputting the representation of thread , notifies thread using condition variable ch-sym-compl. Another symbol can only be produced in the next loop iteration of .

To produce an observable sequence faithful to I for each symbol in we define a homomorphism h that maps symbols from to sequences of observables. Assuming the symbol is chosen, we produce the following observables:

Loop tag To output the thread has to perform one loop iteration. This implicitly produces a loop tag .

Conflict variables For each pair of , we define a conflict variable . Note that and two writes to do not commute under . For each , we produce a tag . Therefore if two variables and are dependent the observation sequences produced for each of them will contain a write to .

Formally, the homomorphism h is given by . For a sequence use define .

We show that iff and commute. The loop tags are independent iff . If then and and do not commute due to the loop tags. Assuming then and commute because they have no common conflict variable they write to. On the other hand, if , then both and will contain and therefore cannot commute. We extend this result to sequences and have that iff .

This concludes our reduction. It remains to show that is preemption-safe iff . By Proposition 1 it suffices to show that iff .

We assume that . Then, for every word we have that . By construction . It remains to show that . By we know there exists a word , such that . Therefore also and by construction .

We assume that . Then, there exists a word such that . By construction . Let us assume towards contradiction that . Then there exists a word in such that . By construction, this implies there exists some such that and . Thus, there exists such that . This implies , which is a contradiction.

Fortunately, a bounded version of the language inclusion modulo I problem is decidable. Recall the relation over from Sect. 6.1. We define a symmetric binary relation over : iff : and . Thus consists of all words that can be obtained from each other by commuting the symbols at positions i and . We next define a symmetric binary relation over : iff : and . The relation intuitively consists of words obtained from each other by making a single forward pass commuting multiple pairs of adjacent symbols. We recursively define as follows: is the identity relation id. For we define , the composition of with . Given a language over , we use to denote the set . In other words, consists of all words which can be generated from using a finite-state transducer that remembers at most k symbols of its input words in its states. By definition we have .

Example 1

We assume the language , where .

because one can swap the letters as position 3 and 4.

because one can only swap the letters as position 3 and 4 in one pass, but not after that swap 2 and 3.

However, , as two passes suffice to do the two swaps.

because in a single pass one can swap 1 and 2 and then 2 and 3.

Definition 2

(Bounded language inclusion modulo an independence relation) Given NFAs over and a constant , the k-bounded language inclusion problem modulo I is: ?

Theorem 4

For NFAs over and a constant is decidable.

We present an algorithm to check k-bounded language inclusion modulo I, based on the antichain algorithm for standard language inclusion [11].

Antichain algorithm for language inclusion

Given a partial order , an antichain over X is a set of elements of X that are incomparable w.r.t. . In order to check for NFAs and , the antichain algorithm proceeds by exploring and in lockstep. Without loss of generality we assume that and do not have -transitions. While is explored nondeterministically, is determinized on the fly for exploration. The algorithm maintains an antichain, consisting of tuples of the form , where and . The ordering relation is given by iff and . The algorithm also maintains a frontier set of tuples yet to be explored.

Given state and a symbol , let denote . Given set of states , let denote . Given tuple in the frontier set, let denote .

In each step, the antichain algorithm explores and by computing -successors of all tuples in its current frontier set for all possible symbols . Whenever a tuple is found with and , the algorithm reports a counterexample to language inclusion. Otherwise, the algorithm updates its frontier set and antichain to include the newly computed successors using the two rules enumerated below. Given a newly computed successor tuple , if there does not exist a tuple p in the antichain with , then is added to the frontier set or antichain (Rule R1). If is added and there exist tuples in the antichain with , then are removed from the antichain (Rule R2). The algorithm terminates by either reporting a counterexample, or by declaring success when the frontier becomes empty.

Antichain algorithm for k-bounded language inclusion modulo I

This algorithm is essentially the same as the standard antichain algorithm, with the automaton above replaced by an automaton accepting . The set of states of consists of triples , where and are words over of up to k length. Intuitively, the words and store symbols that are expected to be matched later along a run. The word contains a list of symbols for transitions taken by , but not yet matched in , whereas contains a list of symbols for transitions taken in , but not yet matched in . We use to denote the empty list. Since for every transition of , the automaton will perform one transition, we have . The set of initial states of is . The set of final states of is . The transition relation is constructed by repeatedly performing the following steps, in order, for each state and each symbol . In what follows, denotes the word obtained from by removing its ith symbol.

Given and

Step S1 Pick new and such that

- Step S2

- If : and is independent of all symbols in , and ,

- else, if : and is independent of all symbols in prior to and

- else, go to S1

- Step S3

- If : and is independent of all symbols in and ,

- else, if : and is independent of all symbols in prior to and

- else, go to S1

Step S4 Add to and go to 1.

Example 2

In Fig. 15, we have an NFA with and . The states of are triples , where and . We explain the derivation of a couple of transitions of . The transition shown in bold from on symbol is obtained by applying the following steps once: S1. Pick following the transition . S2(a). . S3(a). . S4. Add to . The transition shown in bold from on symbol is obtained as follows: S1. Pick following the transition . S2(b). . S3(b). . S4. Add to . It can be seen that accepts the language .

Fig. 15.

Example for illustrating construction of for and

Proposition 2

Given , the automaton accepts at least .

Proof

The proof is by induction on k. The base case is trivially true, as . The induction case assumes that accepts at least and we want to show that accepts at least . We take a word . It must be derived from a word by one additional forward pass of swapping. accepts : In step S1 we pick the same transitions in as to accept . Steps S2 and S3 will be identical as for with the exception of those adjacent symbol pairs that are newly swapped in . For those pairs the symbols are first added to and by S2 and S3. In the next step they are removed because the swapping only allows adjacent symbols to be swapped. This also shows that the bound suffices to accept .

In general NFA can accept words not in . Intuitively this is because has two stacks and can also accept words where the swapping is done in a backward pass (instead of a forward pass required in our definition). For our purposes it is sound to accept more words as long as they are obtained only by swapping independent symbols.

Proposition 3

Given , the automaton accepts at most .

Proof

We need to show that . For this we need to show that is a permutation of a word by repeatedly swapping independent, adjacent symbols. The word must be a permutation of because only accepts if and are empty and the stacks represent exactly the symbols not matched yet in NFA . Further, we need to show only independent symbols may be swapped. The stack contains the symbols not yet matched by and the symbols that were instead accepted by , but not yet presented as input to . Before adding a new symbol to the stack we ensure it is independent with all symbols on the other stack because once matched later it will have to come after all of these. When a symbols is removed it is ensured that it is independent with all symbols on its own stack because it is practically moved ahead of the other symbols on the stack.

Language inclusion check algorithm

We develop a procedure to check language inclusion modulo I (Sect. 6.4) by iteratively increasing the bound k. The procedure is incremental: the check for -bounded language inclusion modulo I only explores paths along which the bound k was exceeded in the previous iteration.

The algorithm for k-bounded language inclusion modulo I is presented as function Inclusion in Algorithm 1 (ignore Lines 22–25 for now). The antichain set consists of tuples of the form , where and . The frontier consists of tuples of the form , where . The word is a sequence of symbols of transitions explored in to get to state . If the language inclusion check fails, is returned as a counterexample to language inclusion modulo I. Each tuple in the frontier set is first checked for equivalence w.r.t. acceptance (Line 18). If this check fails, the function reports language inclusion failure and returns the counterexample (Line 18). If this check succeeds, the successors are computed (Line 20). If a successor satisfies rule R1, it is ignored (Line 21), otherwise it is added to the frontier (Line 26) and the antichain (Line 27). When adding a successor to the frontier the symbol it appended to the counterexample, denoted as . During the update of the antichain the algorithm ensures that its invariant is preserved according to rule R2.

We need to ensure that our language inclusion honors the bound k by ignoring states that exceed the bound. These states are stored for later to allow for a restart of the language inclusion algorithm with a higher bound. Given a newly computed successor for an iteration with bound k, if there exists some in such that the length of or exceeds k (Line 22), we remember the tuple in the set (Line 23). We then prune by removing all states where (line 24) and mark as dirty (line 24). If we find a counterexample to language inclusion we return it and test if it is spurious (Line 8). In case it is spurious we increase the bound to , remove all dirty items from the antichain and frontier (lines 10–11), and add the items from the overflow set (Line 12) to the antichain set and frontier. Intuitively this will undo all exploration from the point(s) the bound was exceeded and restarts from that/those point(s).

We call a counterexample from our language inclusion procedure spurious if it is not a counterexample to the unbounded language inclusion, formally . This test is decidable because there is only a finite number of permutations of . This spuriousness arises from the fact that the bounded language-inclusion algorithm is incomplete and every spurious example can be eliminated by sufficiently increasing the bound k. Note, however, that there exists automata and independence relations for which there is a (different) spurious counterexample for every k. In practice we test if a is spurious by building an automata that accepts exactly and running the language inclusion algorithm with k being the length of . This is very fast because there is exactly one path through .

Theorem 5

(bounded language inclusion check) The procedure inclusion of Algorithm 1 decides for NFAs , bound k, and independence relation I.

Proof

Our algorithm takes as arguments automata and . Conceptually, the algorithm constructs and uses the antichain algorithm [11] to decide the language inclusion. For efficiency, we modify the original antichain language inclusion algorithm to construct the automaton on the fly in the successor relation (line 20). The bound k is enforced separately in line 22.

Theorem 6

(preemption-safety problem) If program is not preemption-safe ( ), then Algorithm 1 will return .

), then Algorithm 1 will return .

Proof

By Theorem 1 we know  . From Proposition 1 we get . From Proposition 3 we know that for any k this is equivalent to , where . Theorem 5 shows that Algorithm 1 decides this for any bound k.

. From Proposition 1 we get . From Proposition 3 we know that for any k this is equivalent to , where . Theorem 5 shows that Algorithm 1 decides this for any bound k.

Finding and Enforcing Mutex Constraints in

If the language inclusion check fails it returns a counterexample trace. Using this counterexample we derive a set of mutual exclusion (mutex) constraints that we enforce in to eliminate the counterexample and then rerun the language inclusion check with the new .

Finding mutex constraints

The counterexample returned by the language inclusion check is a sequence of observables. Since our observables record every branching decision it is easy to reconstruct from a sequence of event identifiers: , where each is a location identifier from . In this section we use to refer to such sequences of event identifiers. We define the neighborhood of , denoted , as the set of all traces that are permutations of the events in and preserve the order of events from the same thread. We separate traces in into good and bad traces. Good traces are all traces that are infeasible under the non-preemptive semantics or that produce an observation sequence that is equivalent to that of a trace feasible under the non-preemptive semantics. All remaining traces in are bad. The goal of our counterexample analysis is to characterize all bad traces in in order to enable inference of mutex constraints.

In order to succinctly represent subsets of , we use ordering constraints between events expressed as happens-before formulas (HB-formulas) [15]. Intuitively, ordering constraints are of the following forms: (a) atomic ordering constraints where A and B are events from . The constraint represents the set of traces in where event A is scheduled before event B; (b) Boolean combinations of atomic constraints and . We have that and respectively represent the intersection and union of the set of traces represented by and , and that represents the complement (with respect to ) of the traces represented by .

Non-preemptive neighborhood

First, we define function to extract a conjunction of atomic ordering constraints from a trace , such that all traces in produce an observation sequence equivalent to . Then, we obtain a correctness constraint that represents all good traces in . Remember, that the good traces are those that are observationally equivalent to a non-preemptive trace. The correctness constraint is a disjunction over the ordering constraints from all traces in that are feasible under non-preemptive semantics: .

enforces the order between conflicting accesses in the abstract trace :

Example

Recall the counterexample trace from the running example in Sect. 3: . There are two traces in that are feasible under non-preemptive semantics:

and

.

We represent

as ) and

as ).

The correctness specification is .

Counterexample enumeration and generalization

We next build a quantifier-free first-order formula over the event identifiers in such that any model of corresponds to a bad, feasible trace in . A trace is feasible if it respects the preexisting synchronization, which is not abstracted away. Bad traces are those that are feasible under the preemptive semantics and not in . Further, we define a generalization function G that works on conjunctions of atomic ordering constraints by iteratively removing a constraint as long as the intersection of traces represented by and is empty. This results in a local minimum of atomic ordering constraints in , so that removing any remaining constraint would include a good trace in . We iteratively enumerate models of , building a constraint for each model and generalizing to represent a larger set of bad traces using G. This results in an ordering constraint in disjunctive normal form , such that the intersection of and is empty and the union equals .

Algorithm 2 shows how the algorithm works. For each model of a trace is extracted in Line 6. From the trace the formula is extracted using described above (Line 8). Line 10 describes the generalization function G, which is implemented using an unsat core computation. We construct a formula , where is a hard constraint and are soft constraints. A satisfying assignment to this formula models feasible traces that are observationally equivalent to a non-preemptive trace. Since is a bad trace the formula must be unsatisfiable. The result of the unsat core computation is a formula that is a conjunction of a minimal set of happens-before constraints required to ensure all trace represented by are bad.

Example

Our trace from Sect. 3 is generalized to . This constraint captures the interleavings where interrupts between locations and . Any trace that fulfills this constraint is bad. All bad traces in are represented as .

Inferring mutex constraints

From each clause in described above, we infer mutex constraints to eliminate all bad traces satisfying . The key observation we exploit is that atomicity violations show up in our formulas as two simple patterns of ordering constraints between events.

The first pattern (visualized in Fig. 16a) indicates an atomicity violation (thread interrupts at a critical moment).

The second pattern is (visualized in Fig. 16b). This pattern is a generalization of the first pattern in that either interrupts or the other way round.

For both patterns the corresponding mutex constraint is .

Fig. 16.

Atomicity violation patterns

Example

The generalized counterexample constraint yields the constraint mutex . In the next section we show how this mutex constraint is enforced in .

Enforcing mutex constraints

To enforce mutex constraints in , we prune paths in that violate the mutex constraints.

Conflicts

Given a mutex constraint , a conflict is a tuple of location identifiers satisfying the following:

are adjacent locations in thread ,

are adjacent locations in the other thread ,

and

.

Intuitively, a conflict represents a minimal violation of a mutex constraint due to the execution of the statement at location in thread j between the two statements at locations and in thread i. Note that a statement at location in thread is executed when the current location of changes from to .

Given a conflict , let and . Further, let and . To prune all interleavings prohibited by the mutex constraints from we need to consider all conflicts derived from all mutex constraints. We denote this set as and let .

Example

We have an example program and its flow-graph in Fig. 17 (we skip the statement labels in the nodes here). Suppose in some iteration we obtain . This yields 2 conflicts: given by and given by . On an aside, this example also illustrates the difficulty of lock placement in the actual code. The mutex constraint would naïvely be translated to the lock . This is not a valid lock placement; in executions executing the else branch, the lock is never released.

Fig. 17.

Example: mutex constraints and conflicts

Constructing new

Initially, let NFA be given by the tuple , where

is the set of states of the abstract program corresponding to , as well as and ,

is the set of abstract observable symbols,

is the initial state of ,

and

is the transition relation with iff according to the abstract preemptive semantics.

To enable pruning paths that violate mutex constraints, we augment the state space of to track the status of conflicts using four-valued propositions , respectively. Initially all propositions are 0. Proposition is incremented from 0 to 1 when conflict is activated, i.e., when control moves from to along a path. Proposition is incremented from 1 to 2 when conflict progresses, i.e., when thread is at and control moves from to . Proposition is incremented from 2 to 3 when conflict completes, i.e., when control moves from to . In practice the value 3 is never reached because the state is pruned when the conflict completes. Proposition is reset to 0 when conflict is aborted, i.e., when thread is at and either moves to a location different from , or moves to before thread moves from to .

Example

In Fig. 17, is activated when moves from to ; progresses if now moves from to and is aborted if instead moves from to ; completes after progressing if moves from to and is aborted if instead moves from to .

Formally, the new is given by the tuple , where:

,

is the set of abstract observable symbols as before,

,

and

is constructed as follows: add to iff and for each , the following hold:

Conflict activation: (the statement at location in thread is executed) if and , then else ,

Conflict progress: (thread is interrupted by and the conflicting statement at location is executed) else if and , then ,

Conflict completion and state pruning: (the statement at location in thread is executed and that completes the conflict) else if and , then delete state ,

Conflict abortion 1: ( executes alternate statement) else if or and , then ,

Conflict abortion 2: ( executes statement at location without interruption by ) else if and , then

In our implementation, the new is constructed on-the-fly. Moreover, we do not maintain the entire set of propositions in each state of . A proposition is added to the list of tracked propositions only after conflict is activated. Once conflict is aborted, is dropped from the list of tracked propositions.

Theorem 7

We are given a program and a sequence of observable symbols that is a counterexample to preemption-safety, formally . If a pattern P eliminating is found, then, after enforcing all resulting mutex constraints in , the counterexample is no longer accepted by , formally .

Proof

The pattern P eliminating represents a mutex constraint , such that the trace is no longer possible. Mutex constraints represent conflicts of the form . Each such conflict represents a context switch that is not allowed: . Because P eliminates we know that has a context switch from to , where and . One of the conflicts representing the mutex constraint is , where and and are the locations immediately before and after . Further, and the location immediately following . If now a context switch happens at location switching to location , this triggers the conflict and this trace will be discarded in .

Global lock placement constraints

Our synthesis loop will keep collecting and enforcing conflicts until the language inclusion check holds. At that point we have collected a set of conflicts that need to be enforced in the original program source code. To avoid deadlocks, the lock placement has to conform to a number of constraints.

We encode the global lock placement constraints for ensuring correctness as an SMT3 formula . Let denote the set of all location and denote the set of all locks available for synthesis. We use scalars of type to denote locations and scalars of type to denote locks. The number of locks is finite and there is a fixed locking order. Let denote the set of all immediate predecessors in node in the flow-graph of the original concrete concurrent program . We use the following Boolean variables in the encoding.

| is placed just before the statement represented by | |

| is placed just after the statement represented by | |

| is placed just before the statement represented by | |

| is placed just after the statement represented by |

For every location in the source code we allow a lock to be placed either immediately before or after it. If a lock is placed before , than is protected by . If is placed after , than is not protected by , but the successor instructions are. Both options are needed, e.g. to lock before the first statement of a thread and to unlock after the last statement of a thread. We define three additional Boolean variables:

- : If location has no predecessor than it is protected by if there is a lock statement before .

If there exists a predecessor to than is protected by if either there is a lock statement before or if is protected by and there is no unlock in between.

Note that either all predecessors are protected by a lock or none. We enforce this in Rule C (C7) below. - : The successors of are protected by if either location is protected by or is placed after .

: We give a fixed lock order that is transitive, asymmetric, and irreflexive. iff needs to be acquired before . This means that an instruction cannot be place inside the scope of .

We describe the constraints and their SMT formulation constituting below. All constraints are quantified over all and all .

- All locations in the same conflict in are protected by the same lock.

- Placing immediately before/after is disallowed. Doing so would make (C1) unsound, as two adjacent locations could be protected by the same lock and there could still be a context-switch in between because of the immediate unlocking and locking again. If has a predecessor then

- We enforce the lock order according to defined in (D3).

- Existing locks may not be nested inside synthesized locks. They are implicitly ordered before synthesized locks in our lock order.

- No statements may be in the scope of synthesized locks to prevent deadlocks.

- Placing both and before/after is disallowed.

- All predecessors must agree on their status. This ensures that joining branches hold the same set of locks. If has at least one predecessor then

- can only be placed only after a .

If has a predecessor then also

else if has no predecessor then - We forbid double locking: A lock may not be acquired if that location is already protected by the lock.

If has a predecessor then also - The end state of thread i is unlocked. This prevents locks from leaking.

According to constraints (C4) and (C5) no locks may be placed around existing or statements. Since both statements are implicit preemption points, where the non-preemptive semantics may context-switch, it is never necessary to synthesize a lock across an existing or instruction to ensure preemption-safety.

We have the following result.

Theorem 8