Abstract

Objectives

To determine the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) (pulmonary embolism [PE] and deep vein thrombosis [DVT]) in individuals with incident SSc in the general population.

Methods

Using a population database that includes all residents of British Columbia, Canada, we conducted a cohort study of all patients with incident SSc and up to 10 age-, sex-, and entry time-matched individuals from the general population. We compared incidence rates of PE, DVT, and VTE between the two groups according to SSc disease duration. We calculated hazard ratios (HRs), adjusting for confounders.

Results

Among 1,245 individuals with SSc (83% female, mean age 56 years), the incidence rates of PE, DVT, and VTE were 3.47, 3.48, and 6.56 per 1000 person-years respectively, whereas the corresponding rates were 0.78, 0.76, and 1.37 per 1000 person-years among 12,670 non-SSc individuals. Compared with non-SSc individuals, the multivariable HRs among SSc patients were 3.73 (95% CI, 1.98–7.04), 2.96 (95% CI, 1.54–5.69), and 3.47 (95% CI, 2.14–5.64) for PE, DVT and VTE, respectively. The age-,sex-,and entry time-matched HRs for PE, DVT, and VTE were highest during the first year after SSc diagnosis (32.77 [95% CI, 6.60–162.75], 8.50 [95% CI, 3.13–23.04], and 12.03 [95% CI, 5.27–27.45], respectively).

Conclusions

These findings provide population-based evidence that SSc patients are at a substantially increased risk of VTE, especially within the first year after SSc diagnosis. Increased monitoring for this potentially fatal outcome and its modifiable risk factors is warranted in this patient population.

Keywords: Systemic Sclerosis, Pulmonary Embolism, Deep Vein Thrombosis

An increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), including pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT), has been reported among patients with inflammatory autoimmune diseases. In particular, patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), dermato-polymyositis, giant cell arteritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and Behcet’s disease are at an increased risk of VTE compared to the general population.1–6 Part of the increased risk of PE and DVT in these diseases is thought to be secondary to an underlying inflammatory state, with pro-inflammatory cytokines playing a role in activation of the coagulation cascade and in turn procoagulants, such as thrombin, stimulating the production of a number of inflammatory mediators.7–10 In addition, the endothelial dysfunction present in conditions such as RA, SLE, and vasculitis, as well as the presence of other risk factors such as antiphospholipid antibodies, may also contribute to the increased risk of VTE in these patient populations.11–13

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is an autoimmune disease with no known etiology and with multi-organ system manifestations, clinically characterized by vasculopathy and progressive fibrosis. Patients with SSc experience high morbidity and mortality, with an overall 10 year survival rate anywhere between 66–82% with variation depending on disease manifestations and degree of end organ involvement.14–16 While inflammation is less prominent than in many other autoimmune conditions, vascular injury and endothelial dysfunction are important pathophysiologic features of the disease,17–20 as manifested clinically by Raynaud’s phenomenon, pulmonary hypertension, renal crisis, and gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE). As such, patients with SSc may be at an increased risk for VTE.

Several studies of SSc cases identified from hospital admissions1,21 or using billing codes from the National Health Institute Research Database in Taiwan22 have reported an increased risk of VTE, except for one.23 One hospital-based study found the risk of PE during the first year after admission for SSc to be increased seven times, which declined over time to 1.38 times or less by year 5 and later.1 However, it remains unclear whether this increased risk is generalizable to the unselected general population. Furthermore, as the aforementioned risk decline was observed in only one hospital-based study to date, extrapolation of this potentially important finding to the general population should be carried out with caution. Given that PE is a preventable yet potentially fatal condition in a patient population already at risk for cardiopulmonary problems in the form of interstitial lung disease, pulmonary hypertension, and coronary artery disease,24 a better understanding of this problem is critical to improving outcomes for SSc patients. In order to address these issues, we evaluated the risk of PE, DVT, and VTE according to SSc duration in an unselected general population context.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data Source

Universal health coverage is provided for all residents of British Columbia (BC), Canada (population ~4.5 million). Population Data BC is a population-based database from the provincial health care system that includes all patients with SSc in the province of BC. It captures all provincially funded health care services since 1990, including all outpatient medical visits,25 hospital admissions and discharges,26 interventions,25 investigations,25 demographic data,27 cancer registry data,28 and vital statistics.29 Population Data BC also includes a comprehensive prescription drug database (PharmaNet),30 which provides information about all dispensed medications for BC residents since 1996. This database has been used reliably in a number of other population-based studies.31–33

Study Design and Cohort Definitions

Using Population Data BC, we compared rates of incident PE, DVT, and VTE between an incident SSc cohort and up to 10 age-, sex-, and entry time-matched individuals without SSc randomly selected from the general population. The comparison cohort was chosen from the same Population Data BC database used to select the SSc cohort. We created an incident SSc cohort of cases diagnosed with SSc for the first time between January 1996 and December 2010; age, sex and entry-time matched individuals without a diagnosis of SSc during the same index dates were randomly selected as the comparison cohort. The cohort entry times were the first diagnosis date of SSc for the SSc cohort and the matched date for the comparison group. The study definition for SSc included the following: a) age ≥ 18 years, and either b) one International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code for SSc by a rheumatologist (ICD-9-CM 710.1) or an ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM code from a hospitalization (ICD-9-CM 710.1 or ICD-10-CM M34.0); or c) a diagnosis of SSc on at least two visits at least two months apart and within a two-year period by a non-rheumatologist physician. In addition, cases were required to have an absence of an SSc diagnosis between January 1990 and December 1995 in order to ensure incident cases.

In order to ensure that our SSc cohort was made up of individuals with only SSc and not with other autoimmune rheumatic diseases, individuals with at least two visits ≥ two months apart subsequent to the SSc diagnostic visit with a diagnosis of RA, psoriatic arthritis, spondyloarthropathy, or SLE were excluded. SSc cases and controls who had a PE or DVT prior to the index date (date of SSc diagnosis for cases or the matching date for controls) were excluded.

The study duration was from January 1, 1996 to December 31, 2010. SSc patients entered the case cohort after all inclusion and exclusion criteria had been met. Participants were observed until they experienced an outcome, died, disenrolled from the health plan (i.e., left BC; approximately 1% per year), or until the follow-up ended, whichever occurred first.

Ascertainment of PE and DVT

The primary outcomes were the first-ever PE or DVT that occurred during the study period. A patient met the definition for either PE or DVT if he or she had a recorded ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM code for PE/DVT and had received a prescription for anticoagulant therapy (heparin, warfarin sodium, or a similar agent). The ICD codes for PE were 415.1, 673.2, or 639.6 (ICD-9-CM) and O88.2 or I26 (ICD-10-CM); the ICD codes for DVT were 453 (ICD-9-CM) and I82.4 or I82.9 (ICD-10-CM). Because VTE is a potentially fatal disease, we also included patients with a fatal outcome. Since a patient may have died before he or she could receive anticoagulation treatment, patients with a recorded diagnosis of PE or DVT were included in the absence of recorded anticoagulant therapy if there was a fatal outcome within two months of diagnosis. The validity of ICD codes to identify VTE has been well demonstrated, with a positive predictive value of up to 95% when VTE was used in the principal position. 34

Assessment of Covariates

Covariates were assessed in the year prior to the index date, and included alcoholism, hypertension, sepsis, varicose veins, inflammatory bowel disease, trauma, fracture, surgery, medication use (glucocorticoids, hormone replacement therapy [HRT], contraceptives, and Cox-2 inhibitors), and healthcare utilization (medical visits and hospitalizations) in the last year prior to cohort entry. The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) was also calculated in the year prior to the index date.35

Statistical Analysis

We compared baseline characteristic between the SSc and comparison cohorts. We identified incident cases of PE and DVT during the follow-up period and calculated incidence rates (IRs) of PE and DVT, both individually and in combination (i.e., VTE), per 1,000 person-years. We estimated the cumulative incidence of each event accounting for the competing risk of death by using the SAS macro CUMINCID and graphically presented these results.36 We used Cox proportional hazard regression models to assess the risk of PE and DVT associated with SSc after adjusting for covariates. We entered confounders one at a time into the Cox models in a forward selection according to each confounder’s impact on the hazard ratio (HR) of the SSc, relative to the HR in the model selected in the previous step. Cut-off for the minimum important relative effect at each step was set to 5%.37 In order to evaluate the impact of duration of SSc (i.e., follow-up time after SSc diagnosis), we estimated the HR yearly for the first five years. We used SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) for all analyses. For all HRs, we calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All p-values were two sided.

We performed two sensitivity analyses. First, we estimated the cumulative incidence of each event accounting for the competing risk of death.38 We also determined the potential impact that a hypothetical unmeasured confounder might have had on our estimates of the association between SSc and the risk of PE and DVT.39 We simulated unmeasured confounders with their prevalences ranging from 10% to 20% in the SSc and control cohorts, and odds ratios (ORs) ranging from 1.3 to 3.0 for the associations between the unmeasured confounder and PE/DVT.

No personal identifying information was made available as part of this study; procedures used were in compliance with BC’s Freedom of Information and Privacy Protection Act. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of British Columbia.

RESULTS

Our primary analysis included 1,245 incident SSc cases (mean age 56.5 years, 82.8% female) and 12,670 age-, sex-, and entry time-matched individuals in the comparison cohort for both PE and DVT. The total follow-up time for the SSc and the comparison cohort was 4,570 person-years and 57,556 person-years, respectively. The baseline characteristics of the SSc and comparison cohorts are summarized in Table 1. Compared with the non-SSc group, the SSc group tended to have higher health care utilization, higher CCI scores, higher frequencies of varicose veins, trauma, and fractures, and more prescriptions for glucocorticoids, HRT, and Cox-2 inhibitors.

Table 1.

Characteristics of SSc and Comparison Cohorts at Baseline

| Variable | SSc N=1,245 |

Non-SSc N=12,670 |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean yrs) | 56.5 ± 15.0 | 56.5 ± 14.9 | 0.965 |

| Female | 1031 (82.8) | 10473 (82.7) | 0.937 |

| Hospitalized | 413 (33.2) | 2020 (15.9) | <0.001 |

| No. MSP visits (mean) | 20.8 ± 17.7 | 9.0 ± 11.0 | <0.001 |

| Charlson’s comorbidity index (mean) | 1.19 ± 1.51 | 0.34 ± 1.07 | <0.001 |

| Alcoholism | 8 (0.6) | 102 (0.8) | 0.736 |

| Hypertension | 307 (24.7) | 2824 (22.3) | 0.059 |

| Sepsis | 3 (0.2) | 24 (0.2) | 0.730 |

| Varicose veins | 24 (1.9) | 103 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 9 (0.7) | 55 (0.4) | 0.181 |

| Trauma | 6 (0.5) | 23 (0.2) | 0.040 |

| Fractures | 30 (2.4) | 177 (1.4) | 0.009 |

| Surgery | 12 (1) | 77 (0.6) | 0.135 |

| Glucocorticoids | 323 (25.9) | 497 (3.9) | <0.001 |

| Hormone replacement therapy | 138 (11.1) | 964 (7.6) | <0.001 |

| Contraceptives | 45 (3.6) | 472 (3.7) | 0.937 |

| Cox2 inhibitors | 113 (9.1) | 389 (3.1) | <0.001 |

Values are N (percentages) unless otherwise noted.

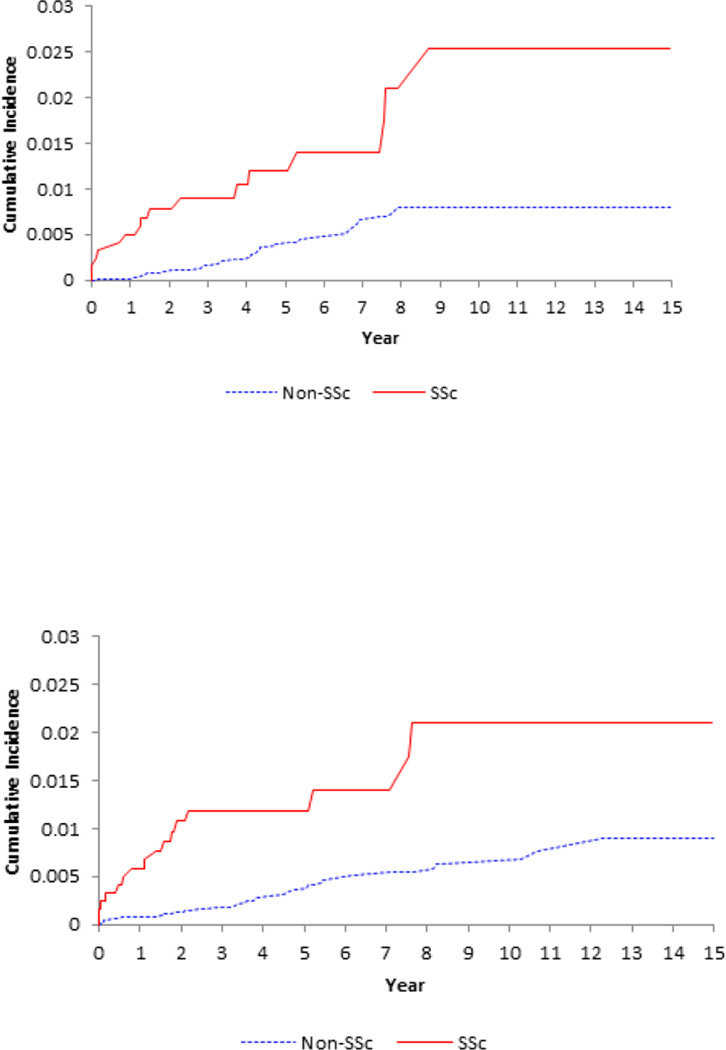

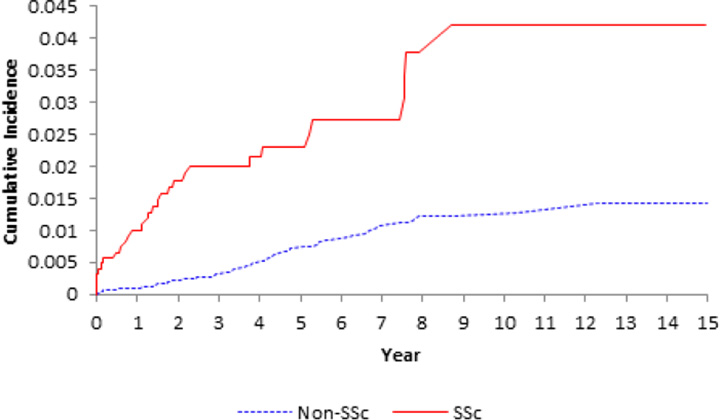

SSc was associated with an increased incidence of PE and DVT (Table 2 and Figure 1). IRs were 3.47 and 3.48 events per 1,000 person-years for PE and DVT in the SSc group, respectively, whereas the corresponding IRs in the comparison cohort were 0.78 and 0.76 events per 1,000 person-years (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hazard Ratios of Incident PE and DVT According to SSc Status

| SSc N= 1,245 |

Non-SSc N=1,2670 |

|

|---|---|---|

| PE | ||

| Cases, N | 16 | 44 |

| Incidence Rate/1000 Person-Years | 3.47 | 0.78 |

| Age-, Sex-, Entry Time-Matched Cox HR (95% CI) | 5.11 (2.85, 9.19) | 1.0 |

| *Fully-Adjusted Cox HR (95% CI) | 3.73 (1.98, 7.04) | 1.0 |

| DVT | ||

| Cases, N | 16 | 44 |

| Incidence Rate/1000 Person-Years | 3.48 | 0.76 |

| Age-, Sex-, Entry Time-Matched Cox HR (95% CI) | 5.13 (2.86, 9.22) | 1.0 |

| *Fully-Adjusted Cox HR (95% CI) | 2.96 (1.54, 5.69) | 1.0 |

| VTE | ||

| Cases, N | 30 | 79 |

| Incidence Rate/1000 Person-Years | 6.56 | 1.37 |

| Age-, Sex-, Entry Time-Matched Cox HR (95% CI) | 5.25 (3.41, 8.07) | 1.0 |

| *Fully-Adjusted Cox HR (95% CI) | 3.47 (2.14, 5.64) | 1.0 |

Fully-adjusted models include the following selected covariates for each outcome (see methods): PE Charlson’s comorbidity Index and glucocorticoids; DVT No. of outpatient visits and glucocorticoids; PE or DVT No. outpatient visits and glucocorticoids. See statistical section for details about the covariate selections.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of pulmonary embolism (upper panel), deep vein thrombosis (middle panel) and venous thromboembolism (lower panel) in the 1245 patients with incident systemic sclerosis (SSc) as compared with the 12,670 age-, sex- entry-time-matched, non-SSc subjects.

The age-, sex-, and entry time-matched HRs among SSc patients compared to the comparison cohort were 5.11 (95% CI, 2.85–9.19) for PE, 5.13 (95% CI, 2.86–9.22) for DVT, and 5.25 (95% CI, 3.41–8.07) for VTE. After adjusting for confounding covariates, the corresponding HRs were 3.73 (95% CI, 1.98–7.04), 2.96 (95% CI, 1.54–5.69), and 3.47 (95% CI, 2.14–5.64) (Table 2).

Overall, when we evaluated the impact of follow-up time after SSc diagnosis, the HRs for PE, DVT and VTE were greatest in the first year after diagnosis, with age-, sex- and entry time-matched HRs of 32.77 (95% CI, 6.60–162.75), 8.50 (95% CI, 3.13, 23.04) and 12.03 (95% CI, 5.27–27.45), respectively (Table 3). The risk of PE, DVT, and VTE was attenuated in the following years, but remained statistically significant for over five years following the initial diagnosis.

Table 3.

Age and sex adjusted Hazard Ratios (HRs) for PE, DVT or both (VTE) in SSc according to follow-up period

| Time after diagnosis |

PE HR (95% CI) |

DVT HR (95% CI) |

VTE HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| <1 year | 32.77 (6.60, 162.75) | 8.50 (3.13, 23.04) | 12.03 (5.27, 27.45) |

| <2 years | 10.26 (4.14, 25.41) | 10.22 (4.69, 22.29) | 10.16 (5.55, 18.60) |

| <3 years | 7.44 (3.35, 16.54) | 8.52 (4.15, 17.50) | 8.14 (4.70, 14.09) |

| <4 years | 6.52 (3.12, 13.64) | 6.00 (3.07, 11.74) | 6.25 (3.76, 10.38) |

| <5 years | 5.03 (2.56, 9.89) | 5.06 (2.64, 9.71) | 5.17 (3.20, 8.36) |

| Total follow-up | 5.11 (2.85, 9.19) | 5.13 (2.86, 9.22) | 5.25 (3.41, 8.07) |

Our sensitivity analysis for the potential impact of unmeasured confounders suggested that our results were robust over the range of simulated parameters. HRs remained significant even at the extreme values of 20% prevalence and an OR of 3.0 for the association between the hypothetical confounder and VTE (Table 4).

Table 4.

Sensitivity analyses on the risk of VTE in patients with systemic sclerosis

| Outcome | Primary Analysis HR (95% CI) |

Sensitivity Analysis 1 HR (95% CI) |

Sensitivity Analysis 2 HR (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence=10 %a ORb=1.3 |

Prevalence=10 %aORb=3.0 |

Prevalence=20 %aORb=1.3 |

Prevalence=20 %aORb=3.0 |

|||

| PE | 3.73 (1.98, 7.04) | 2.92 (1.45, 5.89) | 3.67 (1.94, 6.92) | 3.22 (1.68, 6.16) | 3.33 (1.75, 6.32) | 2.90 (1.53, 5.52) |

| DVT | 2.96 (1.54, 5.69) | 2.40 (1.15, 5.01) | 2.96 (1.54, 5.70) | 2.85 (1.46, 5.56) | 2.94 (1.52, 5.66) | 2.26 (1.14, 4.46) |

| VTE | 3.47 (2.14, 5.64) | 2.90 (1.71, 4.91) | 3.45 (2.13, 5.59) | 3.11 (1.89, 5.12) | 3.28 (2.02, 5.34) | 2.75 (1.67, 4.52) |

DVT, Deep vein thrombosis; HR, Hazard ratio; OR, Odds ratio; PE, Pulmonary embolism; VTE, Venous thromboembolism

hypothetical prevalence of the unmeasured confounder in the SSc cases

hypothetical level of association between the unmeasured confounder and the outcome

Sensitivity analyses 1; accounting for the competing risk of death

Sensitivity analyses 2; accounting for unmeasured confounders

DISCUSSION

Our goal was to evaluate the risk of PE and DVT among SSc patients and its time trends according to disease duration in a general population context. In this large general population-based study, we found that SSc was associated with an increased risk of PE, DVT, and VTE particularly in the first year following the diagnosis of SSc. This increased risk was attenuated over time but remained significantly elevated for all outcomes even after five years. Overall, we observed a three-fold increased risk of PE, DVT, and VTE in SSc patients compared to those without SSc, independent of relevant risk factors such as age, sex, history of hospitalization, and overall comorbidity index. Our findings provide general population-based evidence that SSc, regardless of prior hospitalization, is associated with a substantially increased risk of PE and DVT, and they lend insight into the relative risks over the duration of SSc.

The overall increased risk of PE and VTE found in our study is consistent with two hospital-based studies1,21 and one study that identified SSc cases from billing codes and the Taiwanese Registry for Catastrophic Illness Patient Database.22 Specifically, a nationwide Swedish study that followed hospitalized SSc patients found a 60% increased risk of PE overall1 in the multivariable analysis. A Danish study reported a nearly four-fold increased risk of VTE in SSc patients identified from hospitalization; however, after adjusting for covariates including comorbidities and medication use, this increased risk was no longer significant (incidence rate ratio of 1.5; 95% CI, 0.8–2.9).23 As this point estimate was close to that of the Swedish study,1 the study’s smaller sample size may explain the lack of statistical significance. Regardless, hospital-based case selection may have selected for a slightly different and potentially more severe SSc patient population. Thus, these data may have been confounded by indication for hospitalization, such as more severe disease activity, complications of SSc, or procedures. It also remains unclear whether these hospital-based data had selection bias associated with hospitalization differentially affecting the co-prevalence of the exposure (i.e., SSc) and outcome (i.e., VTE) as compared with the general population. Furthermore, the generalizability of the increased risks in hospitalized patients to SSc patients in the general population remained unclear. A Taiwanese study that employed a different SSc case identification (i.e., using billing codes from their National Health Institute Research Database and confirmed from their national Catastrophic Illness Patient Database) reported a seven-fold increased risk of PE and a ten-fold increased risk of DVT in SSc patients,22 which is substantially higher than the risk reported in the European studies1,21 and in our study. The lack of adjustment for medication use, hospitalization, and physician visits in the Taiwanese study may explain the substantially higher risk compared to both the European study and to our study findings.

There are a number of possible mechanisms that could account for the increased risk of VTE seen in SSc patients. Virchow’s triad proposes three main risk factors for venous thrombosis including venous stasis, increased coagulability of the blood, and damage to the vessel wall.40 SSc patients may have increased damage to the blood vessel wall as suggested by the vasculopathy and vascular injury that are predominant features of the disease.18,41,42 This hypothesis may be of particular relevance in patients with limited cutaneous SSc, in whom vascular pathology is more common. Furthermore, endothelial dysfunction is a risk factor for VTE11 and is a well-described feature of SSc.18–20 The endothelial damage observed in SSc leads to the release of thrombin and subsequent initiation of the coagulation cascade.19 Although this pathway has been best described in the context of SSc-associated pulmonary fibrosis,43,44 similar mechanisms could potentially lead to a systemic hypercoagulable state and an increased risk of VTE in SSc patients, as observed in our study. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), another disease characterized by progressive fibrosis, has been shown to be correlated with an increased risk of DVT as well,45 and it is possible that similar mechanisms are responsible for the link between fibrosis and thrombosis in both SSc and IPF.

Our general population study found that the first year after SSc diagnosis seems to hold the greatest risk for VTE with a decrease in risk over the subsequent five years, similar to the Swedish hospital-based study.1 While SSc is characterized predominantly by fibrosis with less inflammation than many other rheumatic autoimmune diseases, the vasculopathy and vascular injury described above may be more prominent in the early stages of the disease, as manifested clinically by Raynaud’s phenomenon and the early findings of edematous hands.18,41,42 The initial stages of the disease may also be characterized by more inflammation,46 and this may therefore contribute to the increased risk of VTE in the earlier phases of the disease. Chronic inflammation has been associated with increased coagulability through a number of mechanisms, including the upregulation of procoagulant factors, the downregulation of anticoagulants such as Protein C and S, and the suppression of fibrinolysis7. In addition, inflammation has been proposed to be a potential contributor to the increased risk of VTE seen in other inflammatory conditions such as RA.5,47 Finally, it is possible that patients with a new diagnosis of SSc, particularly those with diffuse cutaneous SSc who tend to be sicker, could have more frequent encounters with the healthcare system in their first year after diagnosis, which could theoretically account for the highest risk of VTE in the first year.

The strengths and limitations of our study deserve discussion. We used a large database spanning the entire province of BC, making our findings generalizable to the population at large. Because our data captures both primary care physician and specialist records, both mild and severe cases of SSc are likely to be included in our analysis, further contributing to the generalizability of our results. In addition, disease ascertainment was restricted to patients with incident SSc to better capture the entire span of the natural history of the disease as it relates to the development of PE and DVT and to reduce the risk of bias associated with prevalent exposure (i.e., survivor cohorts).

The potential limitations of our study are inherent to all observational studies that use administrative data. Specifically, there exists the potential for inaccurate diagnosis by using only ICD coding data. However, ICD coding for SSc in Canadian administrative databases has been found to have a specificity of nearly 95%.48 Because 80% of our cases met the definition from rheumatologist or hospitalizaton diagnoses, our identified cases were more likely to be germane SSc cases rather than false positives. However, non-differential misclassification would bias our results towards the null, resulting in conservative estimates. In addition, although outcomes including PE, DVT, and VTE were assessed using administrative data, our definition of VTE has been shown to have a high confirmation rate (94%) in similar databases.17 Even though we adjusted for a number of risk factors that may have influenced our outcomes in our multivariable analysis, we were unable to account for all potentially relevant confounders. To that effect, our administrative data did not have information about lifestyle parameters such as smoking status, activity level, or BMI, although the lack of relevant association of these variables with SSc makes confounding by these variables unlikely.24 Nevertheless, in our sensitivity analysis for plausible ranges of these unmeasured confounders, our estimates were robustly significant. We were unable to measure the prevalence of the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) within our SSc cohort because of the absence of laboratory data, but given the lack of any known significant association between SSc and APS,49,50 the presence of APS is unlikely to provide an explanation for the increased risk of VTE observed in our SSc cohort. Similarly, we did not have information regarding the subtype of SSc (i.e. diffuse versus limited) or the auto-antibody profile. We were therefore unable to draw conclusions about the potential differences in risk for VTE between groups of SSc patients. Nonetheless, our finding of a three-fold increased risk of VTE among all SSc patients is important in and of itself and calls for future studies looking at the risk of VTE in subsets of SSc patients.

In conclusion, this general population-based study demonstrates that SSc is associated with an increased risk of PE, DVT, and VTE, especially during the first year following the diagnosis of SSc. These findings support increased monitoring and vigilance for VTE risk factors among patients with SSc, regardless of recent hospitalization, to help avoid this potentially devastating outcome.

SIGNIFICANCE AND INNOVATIONS.

First study assessing the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in an incident cohort of patients with systemic sclerosis in a general population context.

Patients with systemic sclerosis have an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

The highest risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism is within the first year after the disease diagnosis, suggesting that inflammation may play a role in the pathogenesis of VTE.

Our findings support increased monitoring and vigilance for VTE risk factors among patients with systemic sclerosis, regardless of recent hospitalization, to help avoid this potentially devastating outcome.

Acknowledgments

The BC Ministry of Health, the BC Cancer Agency, and the BC Vital Statistics Agency approved access to and use of the data facilitated by Population Data BC for this study. All inferences, opinions, and conclusions drawn in this paper are those of the authors, and do not reflect the opinions or policies of the Data Stewards.

Financial Support: The study was funded by the Canadian Arthritis Network, The Arthritis Society of Canada, the British Columbia Lupus Society (Grant 10-SRP-IJD-01) and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (Grant MOP 125960 and THC 135235).

Footnotes

Competing Interests: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Zoller B, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Risk of pulmonary embolism in patients with autoimmune disorders: a nationwide follow-up study from Sweden. Lancet. 2012;379:244–249. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carruthers EC, Choi HK, Sayre EC, Avina-Zubieta JA. Risk of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in individuals with polymyositis and dermatomyositis: a general population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205800. Epub ahead of print: http://ard.bmj.com/content/early/2014/09/05/annrheumdis-2014-205800.long. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Avina-Zubieta JA, Bhole VM, Amiri N, Sayre EC, Choi HK. The risk of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in giant cell arteritis: a general population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205665. Epub ahed of print: http://ard.bmj.com/content/early/2014/09/29/annrheumdis-2014-205665.abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Merkel PA, Lo GH, Holbrook JT, Tibbs AK, Allen NB, Davis JC, Jr, et al. Brief communication: high incidence of venous thrombotic events among patients with Wegener granulomatosis: the Wegener's Clinical Occurrence of Thrombosis (WeCLOT) Study. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:620–626. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-8-200505030-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi HK, Rho YH, Zhu Y, Cea-Soriano L, Avina-Zubieta JA, Zhang Y. The risk of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis in rheumatoid arthritis: a UK population-based outpatient cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1182–1187. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yazici Y, Yurdakul S, Yazici H. Behcet's syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2010;12:429–435. doi: 10.1007/s11926-010-0132-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu J, Lupu F, Esmon CT. Inflammation, innate immunity and blood coagulation. Hamostaseologie. 2010;30:5–6. 8-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox EA, Kahn S. The relationship between inflammation and venous thrombosis. A systematic review of clinical studies. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94:362–365. doi: 10.1160/TH05-04-0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Poll T, Buller HR, ten Cate H, Wortel CH, Bauer KA, van Deventer SJ, et al. Activation of coagulation after administration of tumor necrosis factor to normal subjects. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1622–1627. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199006073222302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wakefield TW, Strieter RM, Prince MR, Downing LJ, Greenfield LJ. Pathogenesis of venous thrombosis: a new insight. Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;5:6–15. doi: 10.1016/s0967-2109(96)00083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gresele P, Momi S, Migliacci R. Endothelium, venous thromboembolism and ischaemic cardiovascular events. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:56–61. doi: 10.1160/TH09-08-0562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan F, Galarraga B, Belch JJ. The role of endothelial function and its assessment in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:253–261. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murdaca G, Colombo BM, Cagnati P, Gulli R, Spano F, Puppo F. Endothelial dysfunction in rheumatic autoimmune diseases. Atherosclerosis. 2012;224:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steen VD, Medsger TA. Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972 – 2002. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:940–944. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.066068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steen VD, Medsger TA., Jr Severe organ involvement in systemic sclerosis with diffuse scleroderma. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2000;43:2437–2444. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200011)43:11<2437::AID-ANR10>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Dhaher FF, Pope JE, Ouimet JM. Determinants of morbidity and mortality of systemic sclerosis in Canada. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;39:269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huerta C, Johansson S, Wallander MA, Garcia Rodriguez LA. Risk factors and short-term mortality of venous thromboembolism diagnosed in the primary care setting in the United Kingdom. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:935–943. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.9.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahaleh MB, LeRoy EC. Autoimmunity and vascular involvement in systemic sclerosis (SSc) Autoimmunity. 1999;31:195–214. doi: 10.3109/08916939908994064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludwicka-Bradley A, Silver RM, Bogatkevich GS. Coagulation and autoimmunity in scleroderma interstitial lung disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:212–222. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleming JN, Nash RA, Mahoney WM, Jr, Schwartz SM. Is scleroderma a vasculopathy? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2009;11:103–110. doi: 10.1007/s11926-009-0015-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramagopalan SV, Wotton CJ, Handel AE, Yeates D, Goldacre MJ. Risk of venous thromboembolism in people admitted to hospital with selected immune-mediated diseases: record-linkage study. BMC Med. 2011;9 doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung WS, Lin CL, Sung FC, Hsu WH, Yang WT, Lu CC, et al. Systemic sclerosis increases the risks of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary thromboembolism: a nationwide cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53:1639–1645. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johannesdottir SA, Schmidt M, Horváth-Puhó E, Sorensen HT. Autoimmune skin and connective tissue diseases and risk of venous thromboembolism: a population-based case-control study. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:815–821. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Man A, Zhu Y, Zhang Y, Dubreuil M, Rho YH, Peloquin C, et al. The risk of cardiovascular disease in systemic sclerosis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1188–1193. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator] (2013): Medical Services Plan (MSP) Payment Information File. Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH. 2013 http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 26.British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator] (2013): Discharge Abstract Database (Hospital Separations). Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH. 2013 http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 27.British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator] (2013): Consolidation File (MSP Registration & Premium Billing). Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. MOH. 2013 http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 28.BC Cancer Agency Registry Data (2014). Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract. BC Cancer Agency. 2013 http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 29.BC Vital Statistics Agency [creator] (2012): Vital Statistics Deaths. Population Data BC [publisher]. Data Extract BC Vital Statistics Agnecy. 2013 http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 30.BC Ministry of Health [creator] (2013): PharmaNet. BC Ministry of Health [publisher]. Data Extract. Data Stewardship Committee. 2013 http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data.

- 31.Lacaille D, Anis AH, Guh DP, Esdaile JM. Gaps in care for rheumatoid arthritis: a population study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2005;53:241–248. doi: 10.1002/art.21077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solomon DH, Massarotti E, Garg R, Liu J, Canning C, Schneeweiss S. Association between disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and diabetes risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. JAMA. 2011;305:2525–2531. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aviña-Zubieta JA, Abrahamowicz M, Choi HK, Rahman MM, Sylvestre MP, Esdaile JM, et al. Risk of cerebrovascular disease associated with the use of glucocorticoids in patients with incident rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:990–995. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.140210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White RH, Garcia M, Sadeghi B, Tancredi DJ, Zrelak P, Cuny J, et al. Evaluation of the predictive value of ICD-9-CM coded administrative data for venous thromboembolism in the United States. Thromb Res. 2010;126:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data: differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1075–1079. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90103-8. discussion 1081-1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18:695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med. 2008;3 doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lau B, Cole SR, Gange SJ. Competing risk regression models for epidemiologic data. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:244–256. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schneeweiss S. Sensitivity analysis and external adjustment for unmeasured confounders in epidemiologic database studies of therapeutics. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:291–303. doi: 10.1002/pds.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Virchow RLK. Thrombose und embolie [Thrombosis and emboli] Massachusetts: Science History Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matucci-Cerinic M, Kahaleh B, Wigley FM. Review: evidence that systemic sclerosis is a vascular disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2013;65:1953–1962. doi: 10.1002/art.37988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kahaleh MB. Vascular involvement in systemic sclerosis (SSc) Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22:S19–S23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chambers RC. Procoagulant signalling mechanisms in lung inflammation and fibrosis: novel opportunities for pharmacological intervention? Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:S367–S378. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ludwicka-Bradley A, Bogatkevich G, Silver RM. Thrombin-mediated cellular events in pulmonary fibrosis associated with systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22:S38–S46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hubbard RB, Smith C, Le Jeune I, Gribbin J, Fogarty AW. The association between idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and vascular disease: a population-based study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:1257–1261. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200805-725OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gabrielli A, Avvedimento EV, Krieg T. Scleroderma. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1989–2003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0806188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bacani AK, Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, Heit JA, Matteson EL. Noncardiac vascular disease in rheumatoid arthritis: increase in venous thromboembolic events? Arthritis Rheumatol. 2012;64:53–61. doi: 10.1002/art.33322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bernatsky S, Linehan T, Hanly JG. The accuracy of administrative data diagnoses of systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:1612–1616. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.101149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanna G, Bertolaccini M, Mameli A, Hughes GR, Khamashta MA, Mathieu A. Antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with scleroderma: prevalence and clinical significance. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1795–1796. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.038430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parodi A, Drosera M, Barbieri L, Rebora A. Antiphospholipid antibody system in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40:111–112. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]