Abstract

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with an increased risk of cognitive decline, but the mechanisms remain poorly defined. We sought to determine the relation between serum inflammatory markers and risk of cognitive decline among adults with CKD.

Methods

We studied 757 adults aged ≥55 years with CKD participating in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Cognitive study. We measured interleukin (IL)−1β, IL-1 receptor antagonist, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)−α, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), and fibrinogen in baseline plasma samples. We assessed cognitive function at regular intervals in 4 domains and defined incident impairment as a follow-up score more than 1 SD poorer than the group mean.

Results

The mean age of the sample was 64.3 ± 5.6 years, and the mean follow-up was 6.2 ± 2.5 years. At baseline, higher levels of each inflammatory marker were associated with poorer age-adjusted performance. In analyses adjusted for baseline cognition, demographics, comorbid conditions, and kidney function, participants in the highest tertile of hs-CRP, the highest tertile of fibrinogen, and the highest tertile of IL-1β had an increased risk of impairment in attention compared to participants in the lowest tertile of each marker. Participants in the highest versus lowest tertile of TNF-α had a lower adjusted risk of impairment in executive function. There was no association between other inflammatory markers and change in cognitive function.

Discussion

Among adults with CKD, higher levels of hs-CRP, fibrinogen, and IL-1β were associated with a higher risk of impairment in attention. Higher levels of TNF-α were associated with a lower risk of impaired executive function.

Keywords: aging, chronic kidney disease, cognitive decline, dementia, epidemiology, inflammation

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are at increased risk for cognitive decline and dementia, particularly cognitive decline associated with a vascular component.1, 2 CKD and dementia share several risk factors, such as age, diabetes, and hypertension, suggesting that they have a common pathogenesis. Yet, in most studies, traditional vascular risk factors do not appear to attenuate the excess risk of cognitive decline among patients with CKD.1, 2, 3 Inflammation is implicated in many vascular diseases and has been suggested as a mediator of cognitive decline in patients with CKD. The nature of the association between inflammation and CKD may be bidirectional; that is, inflammation may be both a cause and a consequence of CKD.4, 5

Inflammation has also been identified in experimental studies of dementia.6 However, it remains unclear whether systemic inflammation plays a causative role in the pathogenesis of dementia or whether it is merely an epiphenomenon, as epidemiologic studies have produced mixed findings.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Many of these studies evaluated only 1 or 2 inflammatory markers. Consequently, they provide an incomplete picture of the systemic inflammatory state and its relation to cognitive decline. The intensity of systemic inflammation, as indicated by elevations in multiple markers of inflammation, including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor−α (TNF-α), and C-reactive protein (CRP), appears to increase as kidney function declines.13, 14

Therefore, studying patients with CKD might provide more specific insight into the relation between inflammation and cognitive decline related to vascular causes, as CKD is more strongly associated with vascular dementia than Alzheimer’s disease.1, 2 In 2 cross-sectional studies of patients with CKD, the inflammatory markers interleukin-10, CRP, and fibrinogen correlated with the presence of cognitive impairment.15, 16 To our knowledge, no studies have prospectively evaluated the association of systemic inflammatory markers with cognitive decline among patients with CKD.

We aimed to determine whether systemic inflammatory markers were independently associated with cognitive decline in patients with CKD. To address this question, we measured plasma levels of multiple inflammatory cytokines and acute phase reactants in a subset of adults enrolled in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC), a large cohort study of men and women with CKD. We hypothesized that elevated levels of inflammatory markers would have independent, additive effects on the risk of cognitive decline.

Methods

Study Design and Recruitment

The CRIC Study is a prospective observational cohort study designed to evaluate risk factors for progression of CKD.17, 18 From June 2003 through May 2008, we recruited 3939 persons aged 21 to 74 years from 7 clinical centers across the United States. Participants met age-based estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) criteria: 20 to 70 ml/min/1.73 m2 for ages 21 to 44 years, 20 to 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 for ages 45 to 64 years, and 20 to 50 ml/min/1.73 m2 for ages 65 to 74 years. Exclusion criteria included diagnosis of polycystic kidney disease, pregnancy, recent immunosuppression for kidney disease, coexisting disease likely to affect survival, prior receipt of dialysis or organ transplant, residence in nursing homes, or inability to provide consent. Beginning in 2006, a total of 825 participants aged 55 years or older from 4 of the 7 CRIC centers were enrolled in a cognitive ancillary study (the CRIC COG Study). Of these 825 participants, 18 were excluded from the analysis because they had end-stage renal disease at the CRIC COG baseline visit. Of the remaining participants, 761 had measurement of inflammatory markers at baseline and at least 1 cognitive follow-up assessment. We excluded 4 participants missing important covariates, leaving 757 participants in the analytic cohort.

Ethics, Consent, and Permissions

Institutional review boards at all clinical sites approved the study protocol, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Measurement of Cognitive Function

Participants in CRIC COG underwent a battery of cognitive function tests.19 Tests were administered annually for the first 4 years and then biannually thereafter. The Modified Mini Mental State Examination (3MS) is a test of global cognitive function with components for concentration, orientation, language, praxis, and memory.20 The Trailmaking Test A (Trails A) measures attention, visuospatial scanning, and motor speed. The Trailmaking Test B (Trails B) primarily assesses executive function.21 The Buschke Selective Reminding Test measures verbal memory with delayed components.22 The mean follow-up time was 6.2 ± 2.5 years.

Measurement of Inflammatory Markers

Inflammatory markers were measured a median of 1.2 (interquartile ratio [IQR] = 0.9, 2.0) years before the baseline cognitive assessment. We used high-sensitivity sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays to measure TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels, and standard sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays to measure IL-1RA (Quantikine, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), as previously described.14 We quantified hs-CRP and fibrinogen from ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)−treated plasma samples using laser-based immunonephelometric methods on the BNII nephelometer (Siemens Healthcare, Mountain View, CA). All assays were performed in duplicate, and mean values were used for analysis. Inflammatory markers were analyzed as tertiles.

Covariates

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were assessed at the cognitive baseline visit. We defined diabetes by participant self-report, use of medications for diabetes, or fasting blood glucose of ≥126 mg/dl. We defined hypertension by participant self-report, use of medications for high blood pressure, or a seated blood pressure of ≥140/80 mm Hg. We defined cardiovascular disease as participant self-report of a myocardial infarction, angina, stroke, claudication, amputation, or revascularization procedure of the coronaries or the extremities. We defined tobacco use as current versus former or never use. We calculated the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) with an equation derived from the CRIC Study, using the annual serum creatinine and cystatin C measurements corresponding to the first cognitive function assessment.23 Urine albumin and creatinine were measured on spot urine samples and categorized as <30 mg/g, ≥30 mg/g, or missing for analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or median (intertertile range), and categorical variables were expressed as proportions. We first examined the age-adjusted baseline association between inflammatory markers and cognitive function, expressed as the percent difference in cognitive score relative to that of patients in the lowest tertile of each inflammatory marker. Next, we determined the association between inflammatory markers and longitudinal changes in cognitive scores on each test, using mixed effects models with unstructured residual correlation matrix to account for within-subject correlation. Cognitive test scores were log-transformed for analysis, and then back-transformed for ease of interpretation. We first adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, education, and CRIC clinical center (minimally adjusted model). Next, we adjusted for baseline comorbid conditions, including some factors that may lie in the causal pathway: diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, smoking, eGFR, and albuminuria (multivariable adjusted model). Interactions of inflammatory marker tertile with time were used to capture the association of the markers with change in cognitive function, with a test for linear trend across tertiles. Because the minimally adjusted and multivariable adjusted models were similar, multivariable adjusted models are presented. In sensitivity analyses, we censored observations after the development of end-stage renal disease. We also jointly modeled the outcomes of cognitive decline and time to death or loss to follow-up with shared random effects, to assess whether informative censoring of the cognitive function measures materially changed the results.24

In complementary analyses, we constructed Cox proportional hazards models to determine the association between tertiles of each inflammatory marker and the incidence of cognitive impairment, defined as a test score during follow-up more than 1 SD worse than the group mean at baseline. Individuals with cognitive impairment at the baseline examination were excluded from these analyses. Adjusted models included the baseline cognitive test score in addition to age, sex, race, ethnicity, education, CRIC clinical center, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, smoking, eGFR, and albuminuria. We repeated the models applying a Bonferroni corrected P value of 0.002 to account for multiple comparisons (0.05/[6 inflammatory markers × 4 cognitive tests]).

Finally, to assess whether there were additive effects among the inflammatory markers, we constructed an inflammatory load score, consisting of the number of inflammatory markers in the highest tertile. We compared 2 scores, 1 consisting of IL-1β, hs-CRP, and fibrinogen, the markers with the strongest associations with cognitive decline, to a score consisting of all inflammatory markers.

Results

Baseline Cohort Characteristics

The mean age of the sample was 64.3 ± 5.6 years, and mean estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was 43.2 ± 16.3 ml/min/1.73 m2. The sample included 386 men (51.0%), 379 participants of white race/ethnicity (50.1%), and 383 participants with diabetes (50.6%). The median and intertertile ranges for each inflammatory marker and mean (SD) baseline cognitive test scores are presented in Table 1. IL-β was correlated with IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) (ρ = 0.48, P < 0.01). In addition, hs-CRP was correlated with fibrinogen (ρ = 0.38, P < 0.01), and weakly correlated with IL-1RA (ρ = 0.12, P < 0.01). There was no correlation among the other inflammatory markers.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 757 CRIC participants with measurement of inflammatory markers and cognitive function

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, yr | |

| 50–59 | 175 (23.1) |

| 60–69 | 419 (55.4) |

| ≥70 | 163 (21.5) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 386 (51.0) |

| Female | 371 (49.0) |

| Race | |

| White | 379 (50.1) |

| Black | 325 (42.9) |

| Other/unknown | 53 (7.0) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 21 (2.8) |

| Other/unknown | 736 (97.2) |

| Education | |

| <High school | 108 (14.3) |

| High school graduate | 155 (20.5) |

| Some college | 494 (65.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 383 (50.6) |

| Hypertension | 687 (90.8) |

| Prior cardiovascular disease | 290 (38.3) |

| Current smoker | 79 (10.4) |

| eGFR CRIC, ml/min/1.73 m2 | |

| ≥60 | 124 (16.4) |

| 45 to <60 | 211 (27.9) |

| 30 to <45 | 255 (33.7) |

| <30 | 167 (22.1) |

| Albuminuria (mg/g) | |

| <30 | 351 (46.4) |

| >30 | 381 (50.3) |

| Unknown | 25 (3.3) |

| Inflammatory markers | Median (P33, P67) |

| IL-1β (pg/ml) | 0.06 (0.06, 0.48) |

| IL-1RA (pg/ml) | 634.1 (422.7, 1026.8) |

| TNF-α (pg/ml) | 2.00 (1.60, 2.60) |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 1.92 (1.39, 2.52) |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | 2.47 (1.35, 4.41) |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 4.00 (3.59, 4.45) |

| Cognitive function | Mean (SD) |

| 3MS | 93.15 (7.36) |

| Trails A | 54.29 (36.57) |

| Trails B | 136.95 (77.68) |

| Buschke Selective Reminding Test | 7.44 (2.93) |

CRIC, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; hs-CRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL, interleukin; 3MS, Modified Mini Mental State Examination; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Note: Inflammatory markers are presented as median (33rd, 67th) percentiles.

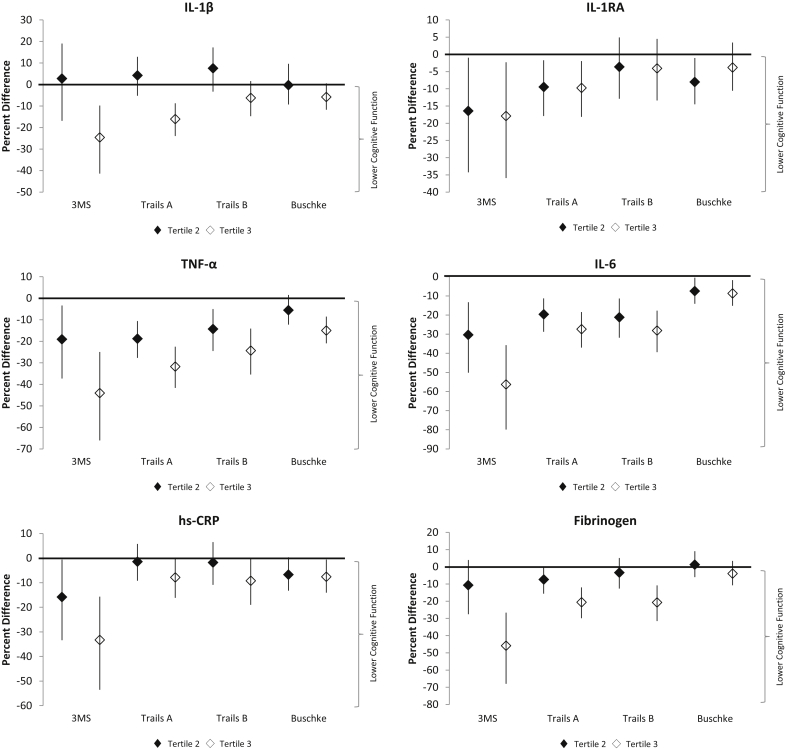

Higher levels of each inflammatory marker were associated with poorer age-adjusted cognitive test scores at baseline (Figure 1). Relative to the scores of participants in the lowest tertile for each inflammatory marker, the percentage difference in cognitive test scores were largest for the 3MS, Trails A tests, and Trails B tests, and less pronounced for the Buschke Selective Reminding Test.

Figure 1.

Adjusted percent difference in baseline cognitive scores by inflammatory marker.

Inflammatory Markers and Change in Cognitive Function

The mean annual percentage change in cognitive function over 6.2 ± 2.5 years of follow-up was small. Mean declines in cognitive function were observed on the 3MS (−1.18%, 95% confidence interval [CI] = −1.92%, −0.44%) and Trails B (−0.53%, 95% CI = −0.92%, −0.13%) tests, whereas cognitive performance improved slightly over time on the Trails A (0.51%, 95% CI = 0.10%, 0.92%) and Buschke (0.82%, 95% CI = 0.38%, 1.27%) tests (Table 2). There was no significant linear association between tertiles of inflammatory markers and change in cognitive function in minimally adjusted models (Supplementary Table S1). In multivariable adjusted models, there was a significant linear trend for larger improvement on the Buschke with higher levels of fibrinogen (Table 2). There was no evidence for a linear trend across inflammatory marker tertiles on other cognitive tests. Compared to participants in the lowest tertile, participants with IL-1RA levels in the middle tertile experienced more rapid cognitive decline on the 3MS, but this did not reach statistical significance for participants in the highest tertile of IL-1RA. Compared to participants in the lowest tertile, participants in the middle tertile of TNF-α experienced significantly slower decline on the 3MS, but this did not reach significance for participants in the highest tertile. We observed a similar pattern in models censoring patients at end-stage renal disease and in joint models for change in cognitive function and time to death or loss to follow-up (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 2.

Adjusted association of inflammatory markers with change in cognitive function

| Parameter estimate (95% confidence interval) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3MS | Trails A | Trails B | Buschke Selective Reminding | |

| Mean annual change, % | –1.18 (–1.92, –0.44) | 0.51 (0.10, 0.92) | –0.53 (–0.92, –0.13) | 0.82 (0.38, 1.27) |

| IL-1β, pg/ml | ||||

| Tertile 2 × time | 0.17 (–1.97, 2.26) | 1.05 (–0.16, 2.25) | –0.08 (–1.28, 1.11) | 0.31 (–1.02, 1.66) |

| Tertile 3 × time | –1.13 (–2.90, 0.60) | –0.30 (–1.30, 0.69) | 0.01 (–0.96, 0.98) | –0.25 (–1.32, 0.83) |

| P value for trend | 0.20 | 0.55 | 0.98 | 0.64 |

| IL-1RA, pg/ml | ||||

| Tertile 2 × time | –2.17 (–3.97, –0.41) | 0.23 (–0.78, 1.22) | 0.55 (–0.43, 1.52) | –0.16 (–1.25, 0.94) |

| Tertile 3 × time | –1.50 (–3.36, 0.32) | –0.40 (–1.45, 0.64) | 0.10 (–0.92, 1.11) | –0.43 (–1.56, 0.71) |

| P value for trend | 0.11 | 0.45 | 0.85 | 0.46 |

| TNF-α, pg/ml | ||||

| Tertile 2 × time | 1.82 (0.04, 3.56) | 0.41 (–0.62, 1.42) | 0.40 (–0.60, 1.39) | 0.65 (–0.46, 1.77) |

| Tertile 3 × time | 1.31 (–0.66, 3.23) | 0.48 (–0.65, 1.60) | 0.28 (–0.82, 1.38) | 0.75 (–0.48, 1.99) |

| P value for trend | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.61 | 0.23 |

| IL-6, pg/ml | ||||

| Tertile 2 × time | 0.53 (–1.28, 2.30) | –0.47 (–1.50, 0.56) | –0.54 (–1.55, 0.46) | –0.23 (–1.35, 0.89) |

| Tertile 3 × time | 0.12 (–1.81, 2.01) | –0.32 (–1.42, 0.77) | –0.01 (–1.08, 1.05) | 0.56 (–0.62, 1.76) |

| P value for trend | 0.91 | 0.57 | 0.99 | 0.36 |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | ||||

| Tertile 2 × time | –0.38 (–2.12, 1.34) | –0.52 (–1.51, 0.46) | –0.56 (–1.53, 0.40) | –0.50 (–1.56, 0.57) |

| Tertile 3 × time | –1.23 (–3.08, 0.57) | –0.19 (–1.23, 0.84) | 0.15 (–0.87, 1.15) | 0.15 (–0.98, 1.28) |

| P value for trend | 0.18 | 0.72 | 0.78 | 0.80 |

| Fibrinogen, g/l | ||||

| Tertile 2 × time | 0.02 (–1.73, 1.74) | 0.03 (–0.97, 1.01) | 0.42 (–0.54, 1.37) | 0.37 (–0.71, 1.45) |

| Tertile 3 × time | 0.02 (–1.89, 1.89) | –0.66 (–1.76, 0.42) | 0.22 (–0.84, 1.26) | 1.37 (0.19, 2.58) |

| P value for trend | 0.98 | 0.23 | 0.69 | 0.02 |

hs-CRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL, interleukin; 3MS, Modified Mini Mental State Examination; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Parameter estimates represent percent change in cognitive function tests per year, relative to the referent group in the lowest tertile of each inflammatory marker. A negative parameter estimate indicates poorer cognitive function over time relative to the referent group.

Models are adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, education, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) center, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, smoking, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and albuminuria. Parameter estimates in bold are statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Inflammatory Markers and Incident Cognitive Impairment

During follow-up, the incidence of impairment ranged between 13.1% on the Trails A test to 19.8% on the Trails B test (Table 3). The associations between inflammatory markers and incident cognitive impairment were consistent with the direction of the parameter estimates from the models evaluating change in cognitive function. In multivariable adjusted models, participants with hs-CRP in the highest tertile, and participants with fibrinogen levels in the highest tertile had more than a 2-fold higher adjusted risk of incident impairment on the Trails A test compared to participants in the lowest tertile of each marker. In addition, participants in the highest tertile of IL-1β had a borderline nonsignificant increased risk of impairment on the Trails A compared to participants in the lowest tertile. Compared to participants in the lowest tertile of IL-1RA, participants with IL-1RA levels in the middle tertile had a borderline nonsignificant higher adjusted risk of incident impairment on the 3MS, but this did not reach significance for participants in the highest tertile. Conversely, participants with TNF-α levels in the second or third tertile had a lower adjusted risk of incident impairment on the Trails B test compared to participants in the lowest tertile. These associations were not statistically significant after accounting for multiple comparisons (Supplementary Table S3).

Table 3.

Adjusted risk of incident cognitive impairment among adults with chronic kidney disease

| Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3MS | Trails A | Trails B | Buschke Selective Reminding | |

| n (%) with impairment | 92 (13.9) | 85 (13.1) | 121 (19.8) | 105 (16.9) |

| IL-1β, pg/ml | ||||

| Tertile 1 (Ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tertile 2 | 0.86 (0.43, 1.72) | 1.16 (0.59, 2.29) | 0.63 (0.31, 1.27) | 1.18 (0.62, 2.23) |

| Tertile 3 | 1.02 (0.60, 1.75) | 1.67 (0.97, 2.89) | 0.92 (0.57, 1.46) | 1.05 (0.64, 1.72) |

| IL-1RA, pg/ml | ||||

| Tertile 1 (Ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tertile 2 | 1.75 (0.99, 3.10) | 1.13 (0.63, 2.03) | 1.09 (0.66, 1.78) | 1.48 (0.89, 2.45) |

| Tertile 3 | 1.26 (0.69, 2.31) | 1.37 (0.73, 2.55) | 1.05 (0.62, 1.78) | 1.56 (0.91, 2.65) |

| TNF-α, pg/ml | ||||

| Tertile 1 (Ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tertile 2 | 0.92 (0.50, 1.70) | 1.47 (0.74, 2.90) | 0.56 (0.34, 0.91) | 0.98 (0.55, 1.77) |

| Tertile 3 | 1.44 (0.75, 2.76) | 1.52 (0.74, 3.14) | 0.47 (0.27, 0.84) | 1.17 (0.64, 2.14) |

| IL-6, pg/ml | ||||

| Tertile 1 (Ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tertile 2 | 1.32 (0.73, 2.39) | 1.08 (0.57, 2.08) | 1.38 (0.81, 2.34) | 1.13 (0.66, 1.95) |

| Tertile 3 | 1.18 (0.63, 2.22) | 1.08 (0.56, 2.10) | 1.33 (0.77, 2.31) | 1.02 (0.58, 1.80) |

| hs-CRP, mg/l | ||||

| Tertile 1 (Ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tertile 2 | 1.06 (0.60, 1.87) | 0.81 (0.43, 1.51) | 1.23 (0.75, 2.02) | 1.61 (0.98, 2.64) |

| Tertile 3 | 1.45 (0.83, 2.53) | 2.27 (1.26, 4.06) | 1.29 (0.78, 2.15) | 1.09 (0.65, 1.84) |

| Fibrinogen, g/l | ||||

| Tertile 1 (Ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tertile 2 | 0.83 (0.48, 1.44) | 1.17 (0.60, 2.29) | 0.92 (0.55, 1.52) | 1.20 (0.72, 1.99) |

| Tertile 3 | 0.73 (0.40, 1.33) | 2.06 (1.10, 3.84) | 1.17 (0.71, 1.93) | 0.82 (0.47, 1.45) |

hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL, interleukin; 3MS, Modified Mini Mental State Examination; Ref, reference; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Models are adjusted for baseline cognitive score, age, sex, race, ethnicity, education, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) center, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, smoking, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and albuminuria. Hazard ratios in bold are statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Compared to participants without elevated levels of IL-1β, hs-CRP, or fibrinogen, there was a borderline higher risk of impairment on the Trails A test for participants with 1 elevated marker (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.72, 95% CI = 0.91, 3.26), and significantly higher risk for participants with 2 or more elevated inflammatory markers (HR = 3.21, 95% CI = 1.71, 6.01) after adjustment for baseline cognitive function, demographic characteristics, comorbid conditions, and kidney function. There was no significant association between inflammatory load and other cognitive tests. In comparison, when the inflammatory load score included all inflammatory markers, the risk of impairment on the Trails A test was significantly higher for participants with 2 elevated inflammatory markers (HR = 2.35, 95% CI = 1.06, 5.22), and 3 or more elevated inflammatory markers (HR = 2.32, 95% CI = 1.07, 5.04), compared to participants with no elevated inflammatory markers.

Discussion

In a large cohort of adults with CKD, higher levels of multiple systemic inflammatory markers were associated with poorer baseline cognitive function. In longitudinal analyses, the association between systemic inflammatory markers and mean change in cognitive function was small. The strongest associations between inflammatory markers and change in cognitive function were observed in the domain of attention, assessed with the Trails A test. Participants with the highest levels of hs-CRP or fibrinogen each had more than a 2-fold increased risk of impairment in attention compared to participants with the lowest levels, independent of multiple potential confounders, whereas participants in the highest tertile of IL-1β had a similar but nonsignificant higher risk of impairment in attention. In addition, participants with elevated levels of 2 or more of these inflammatory markers had more than a 3-fold increased risk of impairment in attention. Perhaps unexpectedly, participants with higher levels of TNF-α were at lower risk for impairment in executive function, assessed with the Trails B test.

Some aspects of our study warrant consideration when interpreting these results. We assessed change in cognitive function in 2 ways: as a continuous measure and as a dichotomous outcome incident cognitive impairment, the latter to capture large declines in cognitive function that are likely to be clinically important. Although the 2 approaches yielded results that were generally consistent, several inflammatory markers had stronger associations with incident impairment than with change in cognitive function, a result that is similar to a previous study of inflammatory markers in patients without CKD.8 This might imply that the association between inflammation and cognitive decline is not uniform across the spectrum of cognitive function. Along the same lines, measurement error may have a larger relative effect on small changes in cognitive function.8 Participants with high levels of inflammatory markers may also be at higher risk for death, which might lead to an underestimation of the association between inflammatory markers and change in cognitive function. However, our findings were robust to analyses that accounted for death or follow-up loss. We assessed each cognitive test as a separate outcome because each taps a different cognitive domain. This approach allowed us to evaluate whether inflammatory markers were associated with decline in specific domains, but increases the likelihood of a false-positive finding. When we used the Bonferroni method to account for multiple comparison, the findings did not reach statistical significance; thus the positive findings in the main analysis should be interpreted with caution. This method of correcting for multiple comparisons has been criticized for being too conservative, because it assumes that the outcomes are independent.

The most studied inflammatory marker is the acute phase reactant CRP. In a meta-analysis of 7 studies in populations without CKD, higher levels of CRP were associated with an increased risk of dementia, including vascular dementia.25 Several but not all studies in the general population have also demonstrated a relationship between elevated CRP levels and cognitive decline.9, 10 In a cross-sectional study of Mexican Americans with CKD, Szerlip et al. found that a serum proteomic profile including CRP was correlated with the prevalence of cognitive impairment; however, the strength of the association for CRP individually was not reported.15

Fibrinogen is an acute phase reactant involved in the coagulation cascade. Like CRP, elevated fibrinogen levels have been linked to cognitive decline and dementia, including vascular dementia, in populations without CKD.26, 27 Seidel et al. reported that elevated fibrinogen levels were cross-sectionally correlated with cognitive impairment in a cohort of 119 patients with CKD.16

Our results extend the findings from prior studies, by demonstrating that CRP and fibrinogen are independently associated with longitudinal changes in some domains of cognitive function in patients with CKD. Our results suggest that elevated CRP, fibrinogen, and possibly IL-1β levels are more strongly associated with incident impairment in attention versus global cognition or memory (assessed in the current study with the 3MS and Buschke tests, respectively). This observation may be due to chance. Alternatively, it may be consistent with the hypothesis that inflammation contributes to cognitive decline in part through vascular mechanisms, as impaired attention is more prominent in vascular causes of dementia than memory impairment.6

In addition, we found that higher levels of the inflammatory cytokine TNF-α were associated with a lower risk of impairment in executive function. Among patients without CKD, the relation between TNF-α and cognitive decline has been conflicting; although 1 study demonstrated an association between increased peripheral blood mononuclear cell production of TNF-α and an increased risk of dementia (specifically Alzheimer’s disease), other studies have not identified an association between TNF-α and cognitive decline.9, 12

To test the hypothesis that inflammatory markers have additive effects on cognitive function, we constructed an inflammatory load score as a proxy for the systemic inflammatory state. These results suggest that IL-1β, hs-CRP, and fibrinogen may have independent, additive effects on the risk of impairment in attention. When the inflammatory load included all 6 inflammatory markers, this association was attenuated, suggesting that IL-1RA, IL-6, and TNF-α did not have additive effects on the risk of impairment after accounting for IL-1β, hs-CRP, and fibrinogen.

Strengths of this study include the prospective design, diverse study population, use of a cognitive battery to assess cognitive function, and measurement of multiple inflammatory markers, providing a more complete picture of the systemic inflammatory state. This study also has several limitations. Participants in CRIC may be at lower risk for cognitive decline than the broader population with CKD, because they are selected for the ability to comply with study visits and they may be more motivated to pursue healthy behaviors. Inflammatory markers were measured at a single point in time, a median 1.2 years before the baseline cognitive test assessment. This lag may have caused a larger relationship between inflammatory markers and changes in cognitive function to go unobserved. We cannot rule out the possibility that the results reflect false-positive findings from conducting multiple comparisons, as the findings did not reach significance using a conservative method to account for multiple comparisons. Finally, because this was an observational study, residual confounding may have affected the results.

In conclusion, in a large cohort of adults with CKD, we found that elevated levels of multiple inflammatory markers were associated with an increased risk of impairment in attention, whereas elevated levels of TNF-α were associated with a lower risk of impaired executive function. Additional studies are needed to confirm these results, and to determine whether treatment of inflammation can slow or prevent cognitive decline.

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The CRIC Study Investigators are as follows: Lawrence J. Appel, Harold I. Feldman, Alan S. Go, Jiang He, John W. Kusek, James P. Lash, Akinlolu Ojo, Mahboob Rahman, and Raymond R. Townsend. Views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Funding for the CRIC Study was obtained under a cooperative agreement from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) (U01DK060990, U01DK060984, U01DK061022, U01DK061021, U01DK061028, U01DK060980, U01DK060963, and U01DK060902). In addition, this work was supported in part by: the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania Clinical and Translational Science Award NIH/NCATS UL1TR000003, Johns Hopkins University UL1 TR-000424, University of Maryland GCRC M01 RR-16500, Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland, UL1TR000439 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH roadmap for Medical Research, Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research (MICHR) UL1TR000433, University of Illinois at Chicago CTSA UL1RR029879, Tulane University Translational Research in Hypertension and Renal Biology P30GM103337, Kaiser Permanente NIH/NCRR UCSF-CTSI UL1 RR-024131. Funding for the CRIC COG study is supported by R01DK069406 from the NIDDK.

Footnotes

Table S1. Minimally adjusted association of inflammatory markers with change in cognitive function

Table S2. Adjusted association of inflammatory markers with change in cognitive function, time to death, or loss to follow-up

Table S3. Adjusted risk of incident cognitive impairment among adults with chronic kidney disease, accounting for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni corrected P = 0.002)

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.kireports.org.

Contributor Information

Manjula Kurella Tamura, Email: mktamura@stanford.edu.

CRIC Study Investigators:

Lawrence J. Appel, Harold I. Feldman, Alan S. Go, Jiang He, John W. Kusek, James P. Lash, Akinlolu Ojo, Mahboob Rahman, and Raymond R. Townsend

Supplementary Material

Minimally adjusted association of inflammatory markers with change in cognitive function

Adjusted association of inflammatory markers with change in cognitive function, time to death, or loss to follow-up

Adjusted risk of incident cognitive impairment among adults with chronic kidney disease, accounting for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni corrected P = 0.002)

References

- 1.Seliger S.L., Siscovick D.S., Stehman-Breen C.O. Moderate renal impairment and risk of dementia among older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Cognition Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1904–1911. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000131529.60019.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helmer C., Stengel B., Metzger M. Chronic kidney disease, cognitive decline, and incident dementia: the 3C Study. Neurology. 2011;77:2043–2051. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823b4765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurella M., Chertow G.M., Fried L.F. Chronic kidney disease and cognitive impairment in the elderly: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2127–2133. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaysen G.A. The microinflammatory state in uremia: causes and potential consequences. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:1549–1557. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1271549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shankar A., Sun L., Klein B.E. Markers of inflammation predict the long-term risk of developing chronic kidney disease: a population-based cohort study. Kidney Int. 2011;80:1231–1238. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorelick P.B., Scuteri A., Black S.E., American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention, and Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:2672–2713. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182299496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt R., Schmidt H., Curb J.D. Early inflammation and dementia: a 25-year follow-up of the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:168–174. doi: 10.1002/ana.10265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weaver J.D., Huang M.H., Albert M., Harris T., Rowe J.W., Seeman T.E. Interleukin-6 and risk of cognitive decline: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Neurology. 2002;59:371–378. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yaffe K., Lindquist K., Penninx B.W. Inflammatory markers and cognition in well-functioning African-American and white elders. Neurology. 2003;61:76–80. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000073620.42047.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dik M.G., Jonker C., Hack C.E. Serum inflammatory proteins and cognitive decline in older persons. Neurology. 2005;64:1371–1377. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000158281.08946.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schram M.T., Euser S.M., de Craen A.J. Systemic markers of inflammation and cognitive decline in old age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:708–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan Z.S., Beiser A.S., Vasan R.S. Inflammatory markers and the risk of Alzheimer disease: the Framingham Study. Neurology. 2007;68:1902–1908. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000263217.36439.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shlipak M.G., Fried L.F., Crump C. Elevations of inflammatory and procoagulant biomarkers in elderly persons with renal insufficiency. Circulation. 2003;107:87–92. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000042700.48769.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta J., Mitra N., Kanetsky P.A. Association between albuminuria, kidney function, and inflammatory biomarker profile in CKD in CRIC. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:1938–1946. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03500412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szerlip H.M., Edwards M.L., Williams B.J. Association between cognitive impairment and chronic kidney disease in Mexican Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2023–2028. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seidel U.K., Gronewold J., Volsek M. The prevalence, severity, and association with HbA1c and fibrinogen of cognitive impairment in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2014;85:693–702. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feldman H.I., Appel L.J., Chertow G.M. The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study: design and methods. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(7 Suppl 2):S148–S153. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000070149.78399.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lash J.P., Go A.S., Appel L.J. Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study: baseline characteristics and associations with kidney function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1302–1311. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00070109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yaffe K., Ackerson L., Kurella Tamura M. Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort I. Chronic kidney disease and cognitive function in older adults: findings from the chronic renal insufficiency cohort cognitive study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:338–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02670.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teng E.L., Chui H.C. The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48:314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reitan R.M. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills. 1958;8:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buschke H., Fuld P.A. Evaluating storage, retention, and retrieval in disordered memory and learning. Neurology. 1974;24:1019–1025. doi: 10.1212/wnl.24.11.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson A.H., Yang W., Hsu C.Y. Estimating GFR among participants in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:250–261. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hogan J.W., Laird N.M. Model-based approaches to analysing incomplete longitudinal and failure time data. Stat Med. 1997;16:259–272. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970215)16:3<259::aid-sim484>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koyama A., O'Brien J., Weuve J. The role of peripheral inflammatory markers in dementia and Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68:433–440. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Oijen M., Witteman J.C., Hofman A. Fibrinogen is associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Stroke. 2005;36:2637–2641. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000189721.31432.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marioni R.E., Stewart M.C., Murray G.D. Peripheral levels of fibrinogen, C-reactive protein, and plasma viscosity predict future cognitive decline in individuals without dementia. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:901–906. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181b1e538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Minimally adjusted association of inflammatory markers with change in cognitive function

Adjusted association of inflammatory markers with change in cognitive function, time to death, or loss to follow-up

Adjusted risk of incident cognitive impairment among adults with chronic kidney disease, accounting for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni corrected P = 0.002)