Abstract

Stroke is a leading cause of disability and death, yet effective treatments for acute stroke has been very limited. Thus far, tissue plasminogen activator has been the only FDA-approved drug for thrombolytic treatment of ischemic stroke patients, yet its application is only applicable to less than 4–5% of stroke patients due to the narrow therapeutic window (< 4.5 hours after the onset of stroke) and the high risk of hemorrhagic transformation. Emerging evidence from basic and clinical studies has shown that therapeutic hypothermia, also known as targeted temperature management, can be a promising therapy for patients with different types of stroke. Moreover, the success in animal models using pharmacologically induced hypothermia (PIH) has gained increasing momentum for clinical translation of hypothermic therapy. This review provides an updated overview of the mechanisms and protective effects of therapeutic hypothermia, as well as the recent development and findings behind PIH treatment. It is expected that a safe and effective hypothermic therapy has a high translational potential for clinical treatment of patients with stroke and other CNS injuries.

Keywords: stroke, therapeutic hypothermia, drug-induced hypothermia, ischemia, cell death, inflammation

Introduction

Although recently stroke fell from the fourth to the fifth leading cause of human death in the United States, each year there are still approximately 750,000 individuals who suffer a new or recurrent stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) (Writing Group et al., 2016). About 610,000 of them encounter a primary stroke attack, and 185,000 have recurrent stroke events. A stroke attack occurrs every 40 seconds, resulting in stroke-related deaths every 4 minutes in the United States. Due to the increasing aged population, the American Heart Association (AHA) has projected that healthcare costs associated with stroke would increase dramatically in the next 20 years according to the increased incidence and prevalence of stroke.

Despite tremendous advancements in understanding the pathogenesis and cellular/molecular mechanisms of stroke over the last few decades, thrombolytic therapy using tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) has been the only drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating acute ischemic stroke (Group, 1995). Although recent data show that the rates of tPA application has been increased between 2005 and 2009, still only < 4% of all stroke patients can benefit from the thrombolytic treatment. This is mainly due to the required early treatment and a high risk of hemorrhagic transformation associated with tPA applications (Adeoye et al., 2011). Thus, there is an urgent need to develop new therapies that have wider therapeutic windows and are more effective for more stroke patients (Shobha et al., 2011).

Over the past two decades, many neuroprotective drugs and treatments have failed the clinical translation from animal models to clinical practice due to the lack of efficacy and, in some cases, intolerable side-effects (Cheng et al., 2004). With the increasing understanding of the cellular and molecular injurious pathways and their interplays in ischemic cascades, it is now increasingly recognized that the conventional strategy of targeting a specific inhibitory or excitatory neuronal receptor or ion channel or a single signaling pathway/gene is far from enough to battle the overwhelming pathophysiological cascades that occur acutely, sub-acutely, and even chronically after a stroke attack. Thus, a global protection paradigm that covers different cell types including neuronal and non-neuronal cells and multiple signaling pathways is necessary to achieve clinically meaningful benefits for stroke patients.

Compelling evidence from pre-clinical research in animal models demonstrated marked protective effects of mild to moderate hypothermia (therapeutic hypothermia) against ischemic and hemorrhagic brain damage (Darwazeh and Yan, 2013; Chamorro et al., 2016). Therapeutic hypothermia ameliorates brain damage through inhibition of multiple pathways such as oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, metabolic disruption, and cell death signals (Katz et al., 2004; Choi et al., 2012). Furthermore, therapeutic hypothermia therapy improves functional outcomes in animal models of stroke and traumatic brain injury (TBI) (Polderman et al., 2002; Choi et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2014). In humans, multiple clinical trials involving both surface cooling and endovascular hypothermia have been effective in decreasing certain quantitative metrics that correspond with functional outcomes after TBI, including intracerebral pressure (ICP) and the mean diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) lesion growth (Schwab et al., 1998a, b, 2001; De Georgia et al., 2004). In clinical practice, mild to moderate hypothermia (3–5°C reduction) is safe and has been used for the treatments of cardiac arrest and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (Dae et al., 2003; Xiao et al., 2013). In fact, therapeutic hypothermia has been incorporated in the American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for post-resuscitation care for more than 10 years (Sugerman and Abella, 2009). Thus, both pre-clinical and clinical evidence supports that therapeutic hypothermia has a promising potential to be an effective treatment for acute brain injury such as stroke and TBI (Schwab et al., 1998b, 2001; De Georgia et al., 2004; van der Worp et al., 2007; Torok et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2011; Yenari and Han, 2012; Lee et al., 2016a). Currently, there is no other experimental stroke therapy that has demonstrated such strong potential in both basic and clinical research, although challenges on the efficacy and the mechanism of action call for future and more specific investigations (Tahir and Pabaney, 2016). This review will focus on emerging concepts in the protective mechanisms of therapeutic hypothermia for treating patients with stroke, as well as highlighting pharmacologically induced hypothermia (PIH), or drug-induced cooling treatments, that can be applied as an acute hypothermic treatment with some unique advantages.

Mechanisms of Therapeutic Hypothermia against Ischemia-induced Brain Damage

Excitotoxicity

Glutamate mediates excitatory synaptic transmission through the activation of ionotropic glutamate receptors that are sensitive to N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA), or kainite in the nervous system. The excitatory transmission mediates normal information processing and neuronal plasticity (Won et al., 2002). It has been well established that excessive activation of glutamate receptors mediates the initial step in excitotoxicity. Upon an ischemic insult, the interruption of blood supply in the brain causes the deprivation of oxygen and glucose, leading to impaired energy metabolism (Choi, 1992; Dugan and Choi, 1994). Consequently, it increases glutamate release through membrane depolarization and the subsequent activation of the voltage gated Ca2+ channels (Choi, 1992; Dugan and Choi, 1994). Due to impaired energy synthesis, reuptake of glutamate is also interfered, which results in the excess accumulation of synaptic glutamate. The sustained over-activation of the ionotropic glutamate receptors leads to neuronal death, mostly due to necrotic cell death mechanism.

Recent reports have shown that therapeutic hypothermia prevents the accumulation or release of glutamate (Zhao et al., 2007a; Yenari and Han, 2012). Also, body temperature influences glutamate excitotoxicity during the acute phase of stroke, indicating that the release of these neurotransmitters is temperature dependent (Campos et al., 2012). Hypothermia can directly affect excitotoxicity through regulating the glutamate receptor 2 (GluR2) subunit of AMPA receptors (Colbourne et al., 2003). Hypothermia recovers the downregulation of GluR2 in hippocampal CA1 neurons after global cerebral ischemia in gerbils. After stroke, hypothermia significantly decreases brain glycine levels, which is needed to activate NMDA receptors and accelerate the function of NMDA receptors (Johnson and Ascher, 1987; Kvrivishvili, 2002). Additionally, hypothermia reduces the number of AMPA and NMDA receptors expressed on hippocampal neurons after stroke, which is associated with decreased infarct volume (Friedman et al., 2001; Li et al., 2011). Hypothermia also abates spreading depolarization that occurs after ischemic stroke by reducing the release of excitatory amino acids (EAA) (Nakashima and Todd, 1996).

Oxidative stress

Neurons are exposed to a minimum level of free radicals from both exogenous and endogenous sources in the normal condition (Dugan and Choi, 1994; Won et al., 2002). However, excess accumulation of reactive oxygen species leads to the damage of basic components for cell function and survival. Because the storage capacity of oxygen is limited in the brain, as well as there being a high probability of lipid peroxidation, neurons can be vulnerable to the change of free radical levels when oxygen supply is interrupted. Following stroke, increases in arachidonic acid, nitric oxide, glutamate, and over-activation of glutamate receptors rapidly develop in the ischemic tissue, which coincides with the production of free oxygen radicals such as superoxide (O2−), peroxynitrite (NO2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (OH−), resulting in neuronal death (Dugan and Choi, 1994; Globus et al., 1995b; Yenari and Han, 2012). The production of free radicals after stroke is temperature-dependent, and the suppression of free radical production is linearly proportional to the decreased temperature (Globus et al., 1995a; Hall, 1997). As a result, hypothermia can significantly reduce the production of free radicals and maintain the endogenous antioxidant activity in injured cells (Globus et al., 1995a).

Apoptosis

Necrosis and apoptosis are two major forms of neuronal cell death after ischemic stroke. Necrosis is a form of cell injury where edema and cellular inflammatory responses occur, leading to excitotoxic death. Apoptosis is the main type of programmed cell death caused by activation of a cascade of intracellular pathways. This cell death mechanism is regulated by the culmination of interactions between pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic signaling genes (Mattson, 2000). Hypoxia and ATP depletion trigger neurons to activate the apoptotic regulatory proteins and several cellular processes, which include mitochondria dysfunction, activation of caspase enzymes, acidosis, calcium imbalance, and other cellular energy metabolism disorders (Won et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2002). These apoptotic events are mostly responsible for some delayed and secondary brain injuries.

Experimental models of ischemia have shown that therapeutic hypothermia prevents neuronal apoptosis through decreasing p53 protein, a transcription factor which activates apoptosis and pro-apoptotic proteins, including Bak, Bax, and NAD depletion (Bargonetti and Manfredi, 2002; Choi et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2014). Hypothermia regulates the levels of apoptotic related genes such as B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2), cytochrome C, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) pathway genes (Bossenmeyer-Pourie et al., 2000; Zhao et al., 2004, 2007b; Liu et al., 2008). After stroke, hypothermia stimulates anti-apoptotic proteins in the Bcl-2 family, causes the reduction of cytochrome c release into the cytosol, inhibits caspase activation, and thus enhances cell survival (Prakasa Babu et al., 2000; Zhao et al., 2004). Experimental animal models have shown that hypothermia has a beneficial effect on the dysfunction of ATP-dependent Na+/K+ pumps and Na+, K+, and Ca+ channels and reduces the influx of calcium into the cells, abating neuronal damage (Siesjo et al., 1989; Hall, 1997).

Autophagy

Autophagy is normally a physiological catabolic process for nutrient recycling, involving degradation of damaged organelles and proteins. The process is tightly regulated by autophagy signaling pathways, and alterations in this process may lead to diseases or exacerbate damage under pathological conditions. In recent years, increased autophagy has been identified as one of the pathophysiological mechanism after ischemic stroke (Chen et al., 2014). We were one of the first groups to demonstrate that a suppressing effect of therapeutic hypothermia on autophagy contributes to the neuroprotection after ischemic stroke (Choi et al., 2012). In our investigation, autophagic activity was examined by the formation of microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3-II) and degradation levels of sequestosome 1/p62 in the penumbra region. Both autophagic factors were decreased by hypothermic treatment using the neurotensin receptor agonist ABS-201. LC3-labeled autophagosome formation and TUNEL/LC3/NeuN triple-labeled cells were also decreased by the treatment. At about the same time, a different group reported that ischemia and reperfusion stimulate cell autophagy and cause cell death, which can be attenuated by mild hypothermia (Cheng et al., 2013). More recent papers demonstrated that hypothermia can inhibit autophagic cell death after TBI and spinal cord injury (Jin et al., 2015, 2016; Seo et al., 2015). The mechanism underlying the anti-autophagy action of therapeutic hypothermia is an active area of current research.

Inflammation

Inflammatory mechanisms are activated after brain ischemia and act as important mediators in the pathogenesis of stroke-induced primary and secondary injuries (Vila et al., 2000; Gelderblom et al., 2009). Although a certain level of inflammation has beneficial effects required for tissue recovery and repairing, many reports have shown that inflammation is a major pathological mechanism underlying ischemic brain injury (Lakhan et al., 2009; Jin et al., 2010). During ischemia, inflammation is characterized by the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, and anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10, as well as the accumulation of neutrophils and the activation of microglia in the injured brain (Huang et al., 2006). Also, ischemia-mediated neuronal damage induces the synthesis and release of chemokines, such as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α), and IP-10 (interferon-inducible protein), which can recruit microglia, monocytes, and neutrophils into the ischemic region (Rappert et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2008; Jiang et al., 2016).

Hypothermia reduces the expressions of this pro-inflammatory immune response such as TNF-α and IL-1β, but it also regulates the expression of some anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) (Matsui and Kakeda, 2008; Jiang et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2016b). Accumulated data suggest that MCP-1 and MIP-1α play crucial roles in ischemia-mediated cellular damage. Upregulation of MCP-1 and MIP-1α were observed after ischemia; while MCP-1 knockout mice show reduced infarct volume after ischemia (Che et al., 2001; Hughes et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2008; Strecker et al., 2013). In addition, MIP-1α injection exacerbated brain infarction but a broad-spectrum chemokine receptor antagonist using viral macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (vMIP-2), prevented neuronal damage from ischemic insults (Takami et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2008). Hypothermia attenuated the expression levels of chemokines such as MCP-1 and MIP-1α (Lee et al., 2016b). Recent reports have demonstrated that hypothermia prevented inflammation-mediated cellular damage through regulating both activation of NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) and Janus kinase (JAK) and signal transducer/activator of transcription pathway (STAT) signaling.

Microglia/macrophages are highly flexible cells with diverse phenotypes that are involved in the generation of distinct effector cells and functions (Murray and Wynn, 2011; Hu et al., 2012). Various cytokines by diverse stimuli lead to the development of M1 or M2 subtypes, which can express different levels of cell surface markers and secrete mediators such as scavenger receptors, chemokines, and cytokines. Recently, we showed that hypothermia shows neuroprotective effects partly due to a shift from M1 to M2 type microglia cells. M1 is the classic activated state that is more associated with pro-inflammation, while M2 is more protective and associated with anti-inflammation (Cherry et al., 2014). This is especially important after brain injury, in which the transition to the M2 state not only clears out inflammation, but also initiates brain repair, and a suppressed M2 response results in greater lesion sizes following both stroke and TBI (Xiong et al., 2011; Kumar et al., 2013; Pérez-de Puig et al., 2013). In the hypothermia-treated stroke brain, there were decreased M1 type reactive factors including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-12, IL-23, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and increased M2 markers such as IL-10, Fizz1, Ym1, and arginase-1 (Lee et al., 2016b). Thus, hypothermia-related regulation of microglia can ameliorate the detrimental effects of a persistent M1 type microglia, including retrograde delayed degeneration, axonal degeneration, and white matter tract injury (Wilson et al., 2004; Maxwell et al., 2006).

Others

Blood-brain barrier (BBB)

Studies have shown that cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury causes structural and functional breakdown of the BBB, resulting in increased BBB permeability, and the extent of disruption is directly correlated with the severity and duration of the insult (Latour et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2009). BBB breakdown not only causes brain edema and hemorrhage, but also increases various cytokines and chemokines, predisposing the brain to a secondary cascade of ischemic injury. BBB disruption after stroke, TBI, or other brain injuries is caused by structural and functional impairment of components of the neurovascular unit, including tight-junction proteins, transport proteins, endothelial cells, astrocytes, and pericytes.

Hypothermia prevents the activation of proteases responsible for degrading the extracellular matrix, such as the matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) which are known to degrade tight-junction proteins (Lakhan et al., 2013). The activity of MMPs and the consequent degradation of vascular basement membrane proteins and the extracellular matrix proteins were reduced by hypothermia (Nagel et al., 2008; Baumann et al., 2009). In addition, hypothermia increases the expression of metalloproteinase inhibitor 2 (also known as TIMP2), an endogenous MMP inhibitor.

Neurogenesis and angiogenesis

Recent reports have shown that hypothermia can affect regenerative activities after stroke. Moderate low temperature (32°C) preserved the stemness of neural stem cells (NSCs) and prevented cell apoptosis. It is suggested that the protective effect of moderate hypothermia is partially associated with preservation of neural stem cells (Saito et al., 2010). Prolonged hypothermia positively interacts with post-ischemic repair processes, such as neurogenesis, resulting in improved functional outcome (Silasi and Colbourne, 2011). Additionally, a few studies have reported on the effect of hypothermia on angiogenesis (Xie et al., 2007). Hypothermia reduced total infarct volume and increased endogenous brain-derived neurotrophin factor (BDNF) level. The microvessel diameter, the number of vascular branches and the vessel surface area were significantly increased in the hypothermia group, suggesting that mild hypothermia enhances angiogenesis in the ischemic brain. Despite the heightened proliferation of NSCs, other studies have suggested that endogenous neurogenesis may not contribute significantly to neuronal repairs. For example, NSCs from pools such as the subventricular zone (SVZ) may be region-specific and committed to become distinct subtypes and thus will be limited in regenerative versatility (Merkle et al., 2007). However, the increased activity of NSCs may play other roles, such as promoting plasticity following injury (Quadrato et al., 2014; Obernier et al., 2015).

Growth factors

Neurotrophic factors in the brain can regulate neuronal synaptic function and plasticity, cellular survival, differentiation and promote neural regeneration/repair (Wang et al., 2012; Bowling et al., 2016; Wurzelmann et al., 2017). There have been conflicting reports about the growth factor response to hypothermic treatment. Hypothermia showed strong neuroprotective effects following stroke via regulating BDNF, glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), and other neurotrophins (D’Cruz et al., 2002; Schmidt et al., 2004; Vosler et al., 2005). However, in a sheep model, hypothermia shortens the activity of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) after hypoxia (Roelfsema et al., 2005). Furthermore, studies have reported that hypothermia may suppress the release of other growth factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) following in vitro hypoxia and nerve growth factor (NGF) in a mouse model of TBI (Goss et al., 1995; Coassin et al., 2010). These findings may be attributed to a decrease in overall metabolism of cells in response to hypothermia.

Other putative mechanisms

Given the global coverage of the temperature reductions during therapeutic hypothermia, as well as the vast array of interconnected molecular pathways, there are various other putative mechanisms that contribute towards hypothermia's neuroprotective effects. Other mechanisms include the impact of hypothermia on cerebral metabolism and consequently cerebral perfusion (Rosomoff and Holaday, 1954). The reduction in temperatures may improve brain glucose consumption and reduce the lactate-glucose and lactate-pyruvate ratios after TBI as compared to normothermia controls (Wang et al., 2007). Another pathophysiology that arises after brain injuries like ischemic stroke is cerebral thermo-pooling, in which localized foci of the brain become hyperthermic after injury, thus making it an ideal target for hypothermia (Schwab et al., 1998b). Indeed, therapeutic hypothermia is effective at reducing thermo-pooling after ischemic stroke and in other pathological cases, such as influenza encephalitis (Hayashi et al., 1997; Hayashi, 2000; Faulds and Meekings, 2013).

Pharmacologically Induced Hypothermia: a Potential Therapeutic Strategy and Implication in Clinical Stage

Limitations of physical cooling

Therapeutic hypothermia has been proposed as a treatment for stroke and shown to be effective in preclinical and clinical studies. However, despite the obvious beneficial effects of therapeutic hypothermia, its clinical application has been limited due to multiple shortcomings. For patients, current hypothermia protocols, including ice cooling or cooling pads, are generally slow (2–8 hours) and cumbersome, or invasive in the case of endovascular cooling. The long timecourse of surface cooling often requires the concomitant use of anesthetics and paralytics in order to curb shivering, which are performed with endotracheal intubation and ventilation, which carry side effects, such as pulmonary infections (Hemmen and Lyden, 2007). The invasive nature of endovascular cooling can result in increased risk of infections and bleeding, and is not as universally applicable, due to the need for a skilled medical personnel to perform the catheter placement (Glushakova et al., 2016). In addition, physical cooling (PC) evokes shivering responses, which is a defensive metabolic adaptation to cold, as well as peripheral vasoconstriction. This systemic response makes effective and accurate cooling difficult, and most often the cooling procedure has to be performed under general anesthesia or sedation reagents (Schwab et al., 1998a; Sessler, 2009). Another possible limitation of hypothermia is its association with systemic infections, including pneumonia and sepsis, although this side effect can be treatable (Hemmen et al., 2010; Geurts et al., 2014). Other potential side effects of hypothermic treatment includes hypothermia-induced diuresis, resulting in hypovolemia and electrolyte depletion, thrombocytopenia, and bradycardia (Schwab et al., 2001). Furthermore, while clinical trials have shown hypothermia to be a feasible treatment, there is conflicting data as to whether hypothermia can effectively improve functional outcomes (Krieger et al., 2001; Schwab et al., 2001; Polderman et al., 2002; De Georgia et al., 2004; Nielsen et al., 2013; Lyden et al., 2016). This is largely due to the plethora of parameters associated with TTM, aside from simply the temperature reduction. Even if patients undergo physical cooling to optimal temperatures of 33–35°C, other factors that could affect the outcomes include the severity, location and subtypes of the injury, the time of intervation, the speed/duration of the cooling treatment, and finally other pharmacological agents (e.g., anesthetics or paralytics) administered (Wan et al., 2014; Subramaniam et al., 2015). All of these factors contribute to the inconsistent findings, but they also provide tremendous potential for optimization of therapeutic hypothermia in order to ensure its efficacy.

Recent early pilot studies with clinical trials have provided modest evidence suggesting both the feasibility and efficacy of therapeutic hypothermia, especially when performed in conjunction with thrombolysis (Hemmen et al., 2010; Piironen et al., 2014). These studies have parlayed into a phase III multi-center randomized controlled trial, EuroHYP-1, and the results will have significant ramifications on the implementation of this clinical strategy (Worp et al., 2014). Nevertheless, considering the modest success associated with therapeutic hypothermia thus far, as well as the current ESO guidelines that discourage the use of current physical means of hypothermia to treat ischemic stroke, it is important to continue the exploration of other avenues that can induce hypothermia in safer and more efficient ways (Ntaios et al., 2015). This is important because it may be possible that the aforementioned limitations may be associated more or less with physical cooling, either with surface cooling or endovascular methods. Thus, increasing research attention has recently been drawn to pharmacological reagents that have shown cooling effects in animals and/or humans.

Pharmacologically induced hypothermia

Pharmacologically induced hypothermia (PIH), which targets the peripheral or central thermoregulatory mechanisms, has emerged as a more efficient and safer treatment for brain disorders (Choi et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2013; Cao et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2014). PIH allows for greater control of temperature changes necessary for TTM. More importantly, we have shown that a PIH therapy targeting the central thermoregulator may suppress external cooling-induced shivering and tachycardia and achieve more rapid and effective hypothermia (Feketa et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2016a). It is well known that shivering, as a physiological defense mechanism against body cooling, is a strong and troublesome reaction that is invariably coupled with physical cooling. This reaction often prevents effective and accurate control of hypothermic treatment. Normally, general anesthesia and/or sedation have to be applied to battle with shivering during physical cooling. PIH using hypothermic drugs acting at the central or peripheral thermoregulatory receptors/channels provides a mechanism-based strategy to eliminate cooling-associated shivering and other responses. This unique effect creates multimodal benefits, including the administration of hypothermic treatment in awake patients without the need for general anesthesia and the avoidance of a number of side effects seen with conventional physical cooling methods.

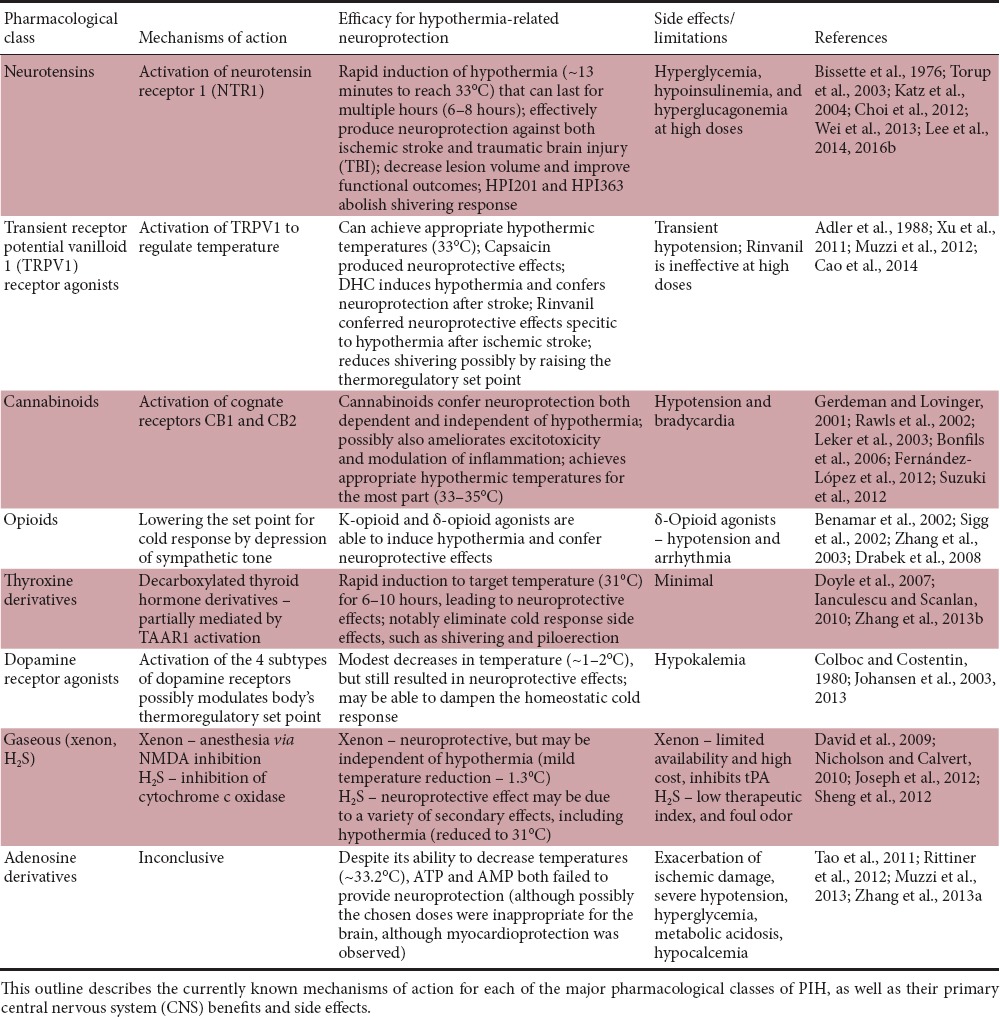

Currently, there are several major classes of pharmacological agents that are categorized based on their mechanisms of action and thermoregulation target: neurotensin, transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1), cannabinoid, opioid, thyroxine derivatives, dopamine, gas, and adenosine derivatives (Table 1). Other drugs, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) that show mild TTM action have also been investigated in the context of therapeutic hypothermia but are not as effective for inducing and maintaining the minimum temperature reductions (Feigin et al., 2002).

Table 1.

Major classes of pharmacological agents as putative candidates for pharmacologically induced hypothermia (PIH)

Our group has developed the second generation of hypothermic compounds acting as a selective neurotensin receptor 1 (NTR1) agonist that can pass through the BBB and efficiently reduce the body and brain temperature in a dose-dependent manner (Choi et al., 2012). For example, HPI-201 and HPI-363 (also known as ABS-201, ABS-363) are NTR1 agonists acting at the hypothalamic thermoregulatory set point. It possesses a high affinity for human NTR1, exhibits BBB permeability, and effectively induces regulated hypothermia in rodents, resulting in protective effects and improved functional recovery after ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke or TBI in mice (Hadden et al., 2005; Choi et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2014, 2016a, b). Other groups showed that an agonist at transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily vanilloid member 1 (TRPV1) can decrease temperature via regulation of the peripheral temperature sensitive channel and confer neuroprotective effects after stroke in animals (Feketa et al., 2013; Cao et al., 2014).

Overall, PIH confers several significant advantages over physical cooling that allow for more feasible clinical implementation. These include the targeting of the thermoregulatory center in the hypothalamus in order to decrease the cold set point to reduce compensatory physiological responses to hypothermia. These effects, such as shivering, piloerection, and vasoconstriction, cause discomfort for the patients and reduces the efficacy of hypothermia (Díaz and Becker, 2010). Importantly, PIH and physical cooling are not mutually exclusive, and the best paradigm may ultimately be a combination therapy of the two in order to create a reliable regimen that uses a lower minimum pharmacological dose (to mitigate potential side effects) to induce hypothermia, but that also dulls the cold response (Muzzi et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2016). Preliminary data has already suggested that combination therapy can provide synergistic effects that augment the benefits of either treatment alone (Lee et al., 2016a).

Conclusion

Therapeutic hypothermia is one of the most promising therapies for neuroprotection against brain injuries such as stroke. The mechanism of action is multifaceted. Therapeutic hypothermia provides a global brain protection rather than targeting a single pathways or a single gene. Therapeutic hypothermia can regulate multiple pathways including excitoxicity, oxidative stress, apoptosis, autophagy and promote regenerative activites. We expect that these actions can be utilized to show synergistic effects with other neuroprotective treatments such as tPA and help to develop combinatory stroke therapy for clinical treatments. To this end, PIH has been demonstrated to be an effective and more efficient hypothermic therapy that shows high feasibility and translational potential for clinical applications. Further study will be needed to have an in-depth understanding of the multiple mechanisms underlying therapeutic hypothermia and reinforced efforts are necessary to verify the efficacy of PIH compounds in large animals such as non-human primates. It is expected that safer and more effective hypothermia therapies may help develop more clinical treatments for stroke and other intractable brain disorders.

Footnotes

Funding: This paper was supported by an American Heart Association (AHA) Postdoctoral Fellowship 15POST25680013 (JHL), NIH grants NS085568 (SPY), and a VA Merit grant RX000666 (SPY).

Conflicts of interest: Authors claim no conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

- Adeoye O, Hornung R, Khatri P, Kleindorfer D. Recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator use for ischemic stroke in the United States: a doubling of treatment rates over the course of 5 years. Stroke. 2011;42:1952–1955. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.612358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler M, Geller E, Rosow C, Cochin J. The opioid system and temperature regulation. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1988;28:429–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.28.040188.002241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargonetti J, Manfredi JJ. Multiple roles of the tumor suppressor p53. Curr Opin Oncol. 2002;14:86–91. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200201000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann E, Preston E, Slinn J, Stanimirovic D. Post-ischemic hypothermia attenuates loss of the vascular basement membrane proteins, agrin and SPARC, and the blood-brain barrier disruption after global cerebral ischemia. Brain Res. 2009;1269:185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.02.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benamar K, Geller EB, Adler MW. Role of the nitric oxide pathway in κ-opioid-induced hypothermia in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:375–378. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.036269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissette G, Nemeroff CB, Loosen PT, Prange AJ, Lipton MA. Hypothermia and intolerance to cold induced by intracisternal administration of the hypothalamic peptide neurotensin. Nature. 1976;262:607–609. doi: 10.1038/262607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfils PK, Reith J, Hasseldam H, Johansen FF. Estimation of the hypothermic component in neuroprotection provided by cannabinoids following cerebral ischemia. Neurochem Int. 2006;49:508–518. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossenmeyer-Pourie C, Koziel V, Daval JL. Effects of hypothermia on hypoxia-induced apoptosis in cultured neurons from developing rat forebrain: comparison with preconditioning. Pediatr Res. 2000;47:385–391. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200003000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling H, Bhattacharya A, Klann E, Chao MV. Deconstructing brain-derived neurotrophic factor actions in adult brain circuits to bridge an existing informational gap in neuro-cell biology. Neural Regen Res. 2016;11:363–367. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.179031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos F, Perez-Mato M, Agulla J, Blanco M, Barral D, Almeida A, Brea D, Waeber C, Castillo J, Ramos-Cabrer P. Glutamate excitoxicity is the key molecular mechanism which is influenced by body temperature during the acute phase of brain stroke. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Balasubramanian A, Marrelli SP. Pharmacologically induced hypothermia via TRPV1 channel agonism provides neuroprotection following ischemic stroke when initiated 90 min after reperfusion. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2014;306:R149–156. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00329.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamorro A, Dirnagl U, Urra X, Planas AM. Neuroprotection in acute stroke: targeting excitotoxicity, oxidative and nitrosative stress, and inflammation. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:869–881. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che X, Ye W, Panga L, Wu DC, Yang GY. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expressed in neurons and astrocytes during focal ischemia in mice. Brain Res. 2001;902:171–177. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Friedman B, Cheng Q, Tsai P, Schim E, Kleinfeld D, Lyden PD. Severe blood-brain barrier disruption and surrounding tissue injury. Stroke. 2009;40:e666–674. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.551341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Sun Y, Liu K, Sun X. Autophagy: a double-edged sword for neuronal survival after cerebral ischemia. Neural Regen Res. 2014;9:1210–1216. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.135329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng BC, Huang HS, Chao CM, Hsu CC, Chen CY, Chang CP. Hypothermia may attenuate ischemia/reperfusion-induced cardiomyocyte death by reducing autophagy. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2064–2069. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YD, Al-Khoury L, Zivin JA. Neuroprotection for ischemic stroke: two decades of success and failure. NeuroRx. 2004;1:36–45. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.1.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry JD, Olschowka JA, O’Banion MK. Neuroinflammation and M2 microglia: the good, the bad, and the inflamed. J Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:98. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-11-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW. Excitotoxic cell death. J Neurobiol. 1992;23:1261–1276. doi: 10.1002/neu.480230915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KE, Hall CL, Sun JM, Wei L, Mohamad O, Dix TA, Yu SP. A novel stroke therapy of pharmacologically induced hypothermia after focal cerebral ischemia in mice. FASEB J. 2012;26:2799–2810. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-201822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coassin M, Duncan KG, Bailey KR, Singh A, Schwartz DM. Hypothermia reduces secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor by cultured retinal pigment epithelial cells. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:1678–1683. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.168864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colboc O, Costentin J. Evidence for thermoregulatory dopaminergic receptors located in the preopticus medialis nucleus of the rat hypothalamus. J Pharmacy Pharmacol. 1980;32:624–629. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1980.tb13018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbourne F, Grooms SY, Zukin RS, Buchan AM, Bennett MV. Hypothermia rescues hippocampal CA1 neurons and attenuates down-regulation of the AMPA receptor GluR2 subunit after forebrain ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2906–2910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2628027100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Cruz BJ, Fertig KC, Filiano AJ, Hicks SD, DeFranco DB, Callaway CW. Hypothermic reperfusion after cardiac arrest augments brain-derived neurotrophic factor activation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:843–851. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200207000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dae MW, Gao DW, Ursell PC, Stillson CA, Sessler DI. Safety and efficacy of endovascular cooling and rewarming for induction and reversal of hypothermia in human-sized pigs. Stroke. 2003;34:734–738. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000057461.56040.FE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwazeh R, Yan Y. Mild hypothermia as a treatment for central nervous system injuries: Positive or negative effects. Neural Regen Res. 2013;8:2677–2686. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2013.28.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David HN, Haelewyn B, Chazalviel L, Lecocq M, Degoulet M, Risso JJ, Abraini JH. Post-ischemic helium provides neuroprotection in rats subjected to middle cerebral artery occlusion-induced ischemia by producing hypothermia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:1159–1165. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Georgia MA, Krieger D, Abou-Chebl A, Devlin T, Jauss M, Davis S, Koroshetz W, Rordorf G, Warach S. Cooling for acute ischemic brain damage (COOL AID) a feasibility trial of endovascular cooling. Neurology. 2004;63:312–317. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000129840.66938.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz M, Becker DE. Thermoregulation: physiological and clinical considerations during sedation and general anesthesia. Anesth Prog. 2010;57:25–33. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006-57.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle KP, Suchland KL, Ciesielski TM, Lessov NS, Grandy DK, Scanlan TS, Stenzel-Poore MP. Novel thyroxine derivatives, thyronamine and 3-iodothyronamine, induce transient hypothermia and marked neuroprotection against stroke injury. Stroke. 2007;38:2569–2576. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.480277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabek T, Han F, Garman RH, Stezoski J, Tisherman SA, Stezoski SW, Morhard RC, Kochanek PM. Assessment of the delta opioid agonist DADLE in a rat model of lethal hemorrhage treated by emergency preservation and resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2008;77:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugan LL, Choi DW. Excitotoxicity, free radicals, and cell membrane changes. Ann Neurol. 1994;35(Suppl):S17–21. doi: 10.1002/ana.410350707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulds M, Meekings T. Temperature management in critically ill patients. Contin Educat Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2013 mks063. [Google Scholar]

- Feigin VL, Anderson CS, Rodgers A, Anderson NE, Gunn AJ. The emerging role of induced hypothermia in the management of acute stroke. J Clinical Neurosci. 2002;9:502–507. doi: 10.1054/jocn.2001.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feketa VV, Balasubramanian A, Flores CM, Player MR, Marrelli SP. Shivering and tachycardic responses to external cooling in mice are substantially suppressed by TRPV1 activation but not by TRPM8 inhibition. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;305:R1040–1050. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00296.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-López D, Faustino J, Derugin N, Wendland M, Lizasoain I, Moro MA, Vexler ZS. Reduced infarct size and accumulation of microglia in rats treated with WIN 55,212-2 after neonatal stroke. Neuroscience. 2012;207:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LK, Ginsberg MD, Belayev L, Busto R, Alonso OF, Lin B, Globus MY. Intraischemic but not postischemic hypothermia prevents non-selective hippocampal downregulation of AMPA and NMDA receptor gene expression after global ischemia. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001;86:34–47. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00252-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelderblom M, Leypoldt F, Steinbach K, Behrens D, Choe CU, Siler DA, Arumugam TV, Orthey E, Gerloff C, Tolosa E, Magnus T. Temporal and spatial dynamics of cerebral immune cell accumulation in stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:1849–1857. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.534503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdeman G, Lovinger DM. CB1 cannabinoid receptor inhibits synaptic release of glutamate in rat dorsolateral striatum. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:468–471. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.1.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geurts M, Macleod MR, Kollmar R, Kremer PH, van der Worp HB. Therapeutic hypothermia and the risk of infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical Care Med. 2014;42:231–242. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a276e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Globus MY, Busto R, Lin B, Schnippering H, Ginsberg MD. Detection of free radical activity during transient global ischemia and recirculation: effects of intraischemic brain temperature modulation. J Neurochem. 1995a;65:1250–1256. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65031250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Globus MY, Alonso O, Dietrich WD, Busto R, Ginsberg MD. Glutamate release and free radical production following brain injury: effects of posttraumatic hypothermia. J Neurochem. 1995b;65:1704–1711. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65041704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glushakova OY, Glushakov AV, Miller ER, Valadka AB, Hayes RL. Biomarkers for acute diagnosis and management of stroke in neurointensive care units. Brain Circ. 2016;2:28. doi: 10.4103/2394-8108.178546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss JR, Styren SD, Miller PD, Kochanek PM, Palmer AM, Marion DW, DeKosky ST. Hypothermia attenuates the normal increase in interleukin 1β RNA and nerve growth factor following traumatic brain injury in the rat. J Neurotrauma. 1995;12:159–167. doi: 10.1089/neu.1995.12.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Group. TNIoNDaSr-PSS. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadden MK, Orwig KS, Kokko KP, Mazella J, Dix TA. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of the antipsychotic potential of orally bioavailable neurotensin (8-13) analogues containing non-natural arginine and lysine residues. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:1149–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall ED. Brain attack. Acute therapeutic interventions. Free radical scavengers and antioxidants. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1997;8:195–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi N. Brain thermo-pooling is the major problem in pediatric influenza encephalitis. No To Hattatsu. 2000;32:156–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi N, Kinosita K, Utagawa A, Jo N, Azuhata T, Shibuya T. Neurochemistry. Springer; 1997. Prevention of cerebral thermo-pooling, free radical reactions, and protection of A10 nervous system by control of brain tissue temperature in severely brain injured patients; pp. 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmen TM, Lyden PD. Induced hypothermia for acute stroke. Stroke. 2007;38:794–799. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000247920.15708.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmen TM, Raman R, Guluma KZ, Meyer BC, Gomes JA, Cruz-Flores S, Wijman CA, Rapp KS, Grotta JC, Lyden PD ICTuS-L Investigators. Intravenous thrombolysis plus hypothermia for acute treatment of ischemic stroke (ICTuS-L) Stroke. 2010;41:2265–2270. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.592295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Li P, Guo Y, Wang H, Leak RK, Chen S, Gao Y, Chen J. Microglia/macrophage polarization dynamics reveal novel mechanism of injury expansion after focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2012;43:3063–3070. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.659656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Upadhyay UM, Tamargo RJ. Inflammation in stroke and focal cerebral ischemia. Surg Neurol. 2006;66:232–245. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes PM, Allegrini PR, Rudin M, Perry VH, Mir AK, Wiessner C. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 deficiency is protective in a murine stroke model. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:308–317. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200203000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ianculescu AG, Scanlan TS. 3-Iodothyronamine (T(1)AM): a new chapter of thyroid hormone endocrinology? Mol Biosyst. 2010;6:1338–1344. doi: 10.1039/b926583j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang MQ, Zhao YY, Cao W, Wei ZZ, Gu X, Wei L, Yu SP. Long-term survival and regeneration of neuronal and vasculature cells inside the core region after ischemic stroke in adult mice. Brain Pathol. 2016 doi: 10.1111/bpa.12425. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin R, Yang G, Li G. Inflammatory mechanisms in ischemic stroke: role of inflammatory cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;87:779–789. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1109766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Lei J, Lin Y, Gao GY, Jiang JY. Autophagy inhibitor 3-MA weakens neuroprotective effects of posttraumatic brain injury moderate hypothermia. World Neurosurg. 2016;88:433–446. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Lin Y, Feng JF, Jia F, Gao GY, Jiang JY. Moderate hypothermia significantly decreases hippocampal cell death involving autophagy pathway after moderate traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32:1090–1100. doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen FF, Jørgensen HS, Reith J. Prolonged drug-induced hypothermia in experimental stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;12:97–102. doi: 10.1053/jscd.2003.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen FF, Hasseldam H, Rasmussen RS, Bisgaard AS, Bonfils PK, Poulsen SS, Hansen-Schwartz J. Drug-induced hypothermia as beneficial treatment before and after cerebral ischemia. Pathobiology. 2013;81:42–52. doi: 10.1159/000352026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JW, Ascher P. Glycine potentiates the NMDA response in cultured mouse brain neurons. Nature. 1987;325:529–531. doi: 10.1038/325529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph C, Buga AM, Vintilescu R, Balseanu AT, Moldovan M, Junker H, Walker L, Lotze M, Popa-Wagner A. Prolonged gaseous hypothermia prevents the upregulation of phagocytosis-specific protein annexin 1 and causes low-amplitude EEG activity in the aged rat brain after cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1632–1642. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LM, Young AS, Frank JE, Wang Y, Park K. Regulated hypothermia reduces brain oxidative stress after hypoxic-ischemia. Brain Res. 2004;1017:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JY, Kim N, Yenari MA, Chang W. Mild hypothermia suppresses calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) induction following forebrain ischemia while increasing GABA-B receptor 1 (GABA-B-R1) expression. Transl Stroke Res. 2011;2:195–201. doi: 10.1007/s12975-011-0082-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger DW, Michael A, Abou-Chebl A, Andrefsky JC, Sila CA, Katzan IL, Mayberg MR, Furlan AJ. Cooling for acute ischemic brain damage (COOL AID) Stroke. 2001;32:1847–1854. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.8.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Stoica BA, Sabirzhanov B, Burns MP, Faden AI, Loane DJ. Traumatic brain injury in aged animals increases lesion size and chronically alters microglial/macrophage classical and alternative activation states. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:1397–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvrivishvili G. Glycine and neuroprotective effect of hypothermia in hypoxic-ischemic brain damage. Neuroreport. 2002;13:1995–2000. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200211150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhan SE, Kirchgessner A, Hofer M. Inflammatory mechanisms in ischemic stroke: therapeutic approaches. J Transl Med. 2009;7:97. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhan SE, Kirchgessner A, Tepper D, Leonard A. Matrix metalloproteinases and blood-brain barrier disruption in acute ischemic stroke. Front Neurol. 2013;4:32. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2013.00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latour LL, Kang DW, Ezzeddine MA, Chalela JA, Warach S. Early blood-brain barrier disruption in human focal brain ischemia. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:468–477. doi: 10.1002/ana.20199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Wei L, Gu X, Wei Z, Dix TA, Yu SP. Therapeutic effects of pharmacologically induced hypothermia against traumatic brain injury in mice. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31:1417–1430. doi: 10.1089/neu.2013.3251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Wei L, Gu X, Won S, Wei ZZ, Dix TA, Yu SP. Improved therapeutic benefits by combining physical cooling with pharmacological hypothermia after severe stroke in rats. Stroke. 2016a;47:1907–1913. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Wei ZZ, Cao W, Won S, Gu X, Winter M, Dix TA, Wei L, Yu SP. Regulation of therapeutic hypothermia on inflammatory cytokines, microglia polarization, migration and functional recovery after ischemic stroke in mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2016b;96:248–260. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leker RR, Gai N, Mechoulam R, Ovadia H. Drug-induced hypothermia reduces ischemic damage. Stroke. 2003;34:2000–2006. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000079817.68944.1E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Benashski S, McCullough LD. Post-stroke hypothermia provides neuroprotection through inhibition of AMP-activated protein kinase. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28:1281–1288. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Khan H, Geng X, Zhang J, Ding Y. Pharmacological hypothermia: a potential for future stroke therapy? Neurol Res. 2016;38:478–490. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2016.1187826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Kim JY, Koike MA, Yoon YJ, Tang XN, Ma H, Lee H, Steinberg GK, Lee JE, Yenari MA. FasL shedding is reduced by hypothermia in experimental stroke. J Neurochem. 2008;106:541–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05411.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyden P, Hemmen T, Grotta J, Rapp K, Ernstrom K, Rzesiewicz T, Parker S, Concha M, Hussain S, Agarwal S, Meyer B, Jurf J, Altafullah I, Raman R Collaborators. Results of the Ictus 2 trial (intravascular cooling in the treatment of stroke 2) Stroke. 2016;47:2888–2895. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.014200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T, Kakeda T. IL-10 production is reduced by hypothermia but augmented by hyperthermia in rat microglia. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25:709–715. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP. Apoptotic and anti-apoptotic synaptic signaling mechanisms. Brain Pathol. 2000;10:300–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2000.tb00264.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell WL, MacKinnon MA, Smith DH, McIntosh TK, Graham DI. Thalamic nuclei after human blunt head injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:478–488. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000229241.28619.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkle FT, Mirzadeh Z, Alvarez-Buylla A. Mosaic organization of neural stem cells in the adult brain. Science. 2007;317:381–384. doi: 10.1126/science.1144914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:723–737. doi: 10.1038/nri3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzzi M, Blasi F, Chiarugi A. AMP-dependent hypothermia affords protection from ischemic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:171–174. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzzi M, Felici R, Cavone L, Gerace E, Minassi A, Appendino G, Moroni F, Chiarugi A. Ischemic neuroprotection by TRPV1 receptor-induced hypothermia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:978–982. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel S, Su Y, Horstmann S, Heiland S, Gardner H, Koziol J, Martinez-Torres FJ, Wagner S. Minocycline and hypothermia for reperfusion injury after focal cerebral ischemia in the rat: effects on BBB breakdown and MMP expression in the acute and subacute phase. Brain Res. 2008;1188:198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima K, Todd MM. Effects of hypothermia on the rate of excitatory amino acid release after ischemic depolarization. Stroke. 1996;27:913–918. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.5.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson CK, Calvert JW. Hydrogen sulfide and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Pharmacol Res. 2010;62:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen N, Wetterslev J, Cronberg T, Erlinge D, Gasche Y, Hassager C, Horn J, Hovdenes J, Kjaergaard J, Kuiper M, Pellis T, Stammet P, Wanscher M, Wise MP, Åneman A, Al-Subaie N, Boesgaard S, Bro-Jeppesen J, Brunetti I, Bugge JF, et al. Targeted temperature management at 33°C versus 36°C after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2197–2206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ntaios G, Dziedzic T, Michel P, Papavasileiou V, Petersson J, Staykov D, Thomas B, Steiner T. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines for the management of temperature in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke. 2015;10:941–949. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obernier K, Tong CK, Alvarez-Buylla A. Restricted nature of adult neural stem cells: re-evaluation of their potential for brain repair. Adult neurogenesis twenty years later: physiological function versus brain repair. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:162. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-de Puig I, Miró F, Salas-Perdomo A, Bonfill-Teixidor E, Ferrer-Ferrer M, Márquez-Kisinousky L, Planas AM. IL-10 deficiency exacerbates the brain inflammatory response to permanent ischemia without preventing resolution of the lesion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:1955–1966. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piironen K, Tiainen M, Mustanoja S, Kaukonen KM, Meretoja A, Tatlisumak T, Kaste M. Mild hypothermia after intravenous thrombolysis in patients with acute stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Stroke. 2014;45:486–491. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polderman KH, Tjong Tjin Joe R, Peerdeman SM, Vandertop WP, Girbes AR. Effects of therapeutic hypothermia on intracranial pressure and outcome in patients with severe head injury. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:1563–1573. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1511-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakasa Babu P, Yoshida Y, Su M, Segura M, Kawamura S, Yasui N. Immunohistochemical expression of Bcl-2, Bax and cytochrome c following focal cerebral ischemia and effect of hypothermia in rat. Neurosci Lett. 2000;291:196–200. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quadrato G, Elnaggar MY, Di Giovanni S. Adult neurogenesis in brain repair: cellular plasticity vs. cellular replacement. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:17. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappert A, Bechmann I, Pivneva T, Mahlo J, Biber K, Nolte C, Kovac AD, Gerard C, Boddeke HW, Nitsch R, Kettenmann H. CXCR3-dependent microglial recruitment is essential for dendrite loss after brain lesion. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8500–8509. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2451-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawls S, Cabassa J, Geller EB, Adler MW. CB1 receptors in the preoptic anterior hypothalamus regulate WIN 55212-2 [(4,5-dihydro-2-methyl-4(4-morpholinylmethyl)-1-(1-naphthalenyl-carbonyl)-6H-pyrrolo[3,2,1ij]quinolin-6-one]-induced hypothermia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;301:963–968. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.3.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittiner JE, Korboukh I, Hull-Ryde EA, Jin J, Janzen WP, Frye SV, Zylka MJ. AMP is an adenosine A1 receptor agonist. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:5301–5309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.291666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelfsema V, Gunn AJ, Breier BH, Quaedackers JS, Bennet L. The effect of mild hypothermia on insulin-like growth factors after severe asphyxia in the preterm fetal sheep. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2005;12:232–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosomoff HL, Holaday DA. Cerebral blood flow and cerebral oxygen consumption during hypothermia. Am J Physiol. 1954;179:85–88. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1954.179.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Fukuda N, Matsumoto T, Iribe Y, Tsunemi A, Kazama T, Yoshida-Noro C, Hayashi N. Moderate low temperature preserves the stemness of neural stem cells and suppresses apoptosis of the cells via activation of the cold-inducible RNA binding protein. Brain Res. 2010;1358:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt KM, Repine MJ, Hicks SD, DeFranco DB, Callaway CW. Regional changes in glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor after cardiac arrest and hypothermia in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2004;368:135–139. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab S, Schwarz S, Aschoff A, Keller E, Hacke W. Moderate hypothermia and brain temperature in patients with severe middle cerebral artery infarction. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1998a;71:131–134. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6475-4_39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab S, Schwarz S, Spranger M, Keller E, Bertram M, Hacke W. Moderate hypothermia in the treatment of patients with severe middle cerebral artery infarction. Stroke. 1998b;29:2461–2466. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.12.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab S, Georgiadis D, Berrouschot J, Schellinger PD, Graffagnino C, Mayer SA. Feasibility and safety of moderate hypothermia after massive hemispheric infarction. Stroke. 2001;32:2033–2035. doi: 10.1161/hs0901.095394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo JY, Kim YH, Kim JW, Kim SI, Ha KY. Effects of therapeutic hypothermia on apoptosis and autophagy after spinal cord injury in rats. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2015;40:883–890. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessler DI. Thermoregulatory defense mechanisms. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:S203–210. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181aa5568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng SP, Lei B, James ML, Lascola CD, Venkatraman TN, Jung JY, Maze M, Franks NP, Pearlstein RD, Sheng H, Warner DS. Xenon neuroprotection in experimental strokeinteractions with hypothermia and intracerebral hemorrhage. Anesthesiology. 2012;117:1262–1275. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182746b81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shobha N, Buchan AM, Hill MD. Canadian Alteplase for Stroke Effectiveness S (2011) Thrombolysis at 3-4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke onset--evidence from the Canadian Alteplase for Stroke Effectiveness Study (CASES) registry. Cerebrovasc Dis. 31:223–228. doi: 10.1159/000321893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siesjo BK, Bengtsson F, Grampp W, Theander S. Calcium, excitotoxins, and neuronal death in the brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1989;568:234–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb12513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigg DC, Coles JA, Oeltgen PR, Iaizzo PA. Role of δ-opioid receptor agonists on infarct size reduction in swine. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1953–H1960. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01045.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silasi G, Colbourne F. Therapeutic hypothermia influences cell genesis and survival in the rat hippocampus following global ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:1725–1735. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strecker JK, Minnerup J, Schutte-Nutgen K, Gess B, Schabitz WR, Schilling M. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1-deficiency results in altered blood-brain barrier breakdown after experimental stroke. Stroke. 2013;44:2536–2544. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam A, Tiruvoipati R, Botha J. Is cooling still cool? Ther Hypothermia Temp Manag. 2015;5:13–16. doi: 10.1089/ther.2014.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugerman NT, Abella BS. Hospital-based use of therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest in adults. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:371–376. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N, Suzuki M, Murakami K, Hamajo K, Tsukamoto T, Shimojo M. Cerebroprotective effects of TAK-937, a cannabinoid receptor agonist, on ischemic brain damage in middle cerebral artery occluded rats and non-human primates. Brain Res. 2012;1430:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahir RA, Pabaney AH. Therapeutic hypothermia and ischemic stroke: A literature review. Surg Neurol Int. 2016;7:S381–386. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.183492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takami S, Minami M, Nagata I, Namura S, Satoh M. Chemokine receptor antagonist peptide, viral MIP-II, protects the brain against focal cerebral ischemia in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1430–1435. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200112000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Z, Zhao Z, Lee CC. 5’-Adenosine monophosphate induced hypothermia reduces early stage myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in a mouse model. Am J Transl Res. 2011;3:351–361. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torok E, Klopotowski M, Trabold R, Thal SC, Plesnila N, Scholler K. Mild hypothermia (33 degrees C) reduces intracranial hypertension and improves functional outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Neurosurgery. 2009;65:352–359. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000345632.09882.FF. discussion 359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torup L, Borsdal J, Sager T. Neuroprotective effect of the neurotensin analogue JMV-449 in a mouse model of permanent middle cerebral ischaemia. Neurosci Lett. 2003;351:173–176. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Worp HB, Sena ES, Donnan GA, Howells DW, Macleod MR. Hypothermia in animal models of acute ischaemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain. 2007;130:3063–3074. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vila N, Castillo J, Davalos A, Chamorro A. Proinflammatory cytokines and early neurological worsening in ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2000;31:2325–2329. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.10.2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosler PS, Logue ES, Repine MJ, Callaway CW. Delayed hypothermia preferentially increases expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor exon III in rat hippocampus after asphyxial cardiac arrest. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;135:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan YH, Nie C, Wang HL, Huang CY. Therapeutic hypothermia (different depths, durations, and rewarming speeds) for acute ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovascular Dis. 2014;23:2736–2747. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HK, Park UJ, Kim SY, Lee JH, Kim SU, Gwag BJ, Lee YB. Free radical production in CA1 neurons induces MIP-1alpha expression, microglia recruitment, and delayed neuronal death after transient forebrain ischemia. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1721–1727. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4973-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Li A, Zhi D, Huang H. Effect of mild hypothermia on glucose metabolism and glycerol of brain tissue in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Chinese J Ttraumatol. 2007;10:246–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang H, Wang Z, Geng Z, Liu H, Yang H, Song P, Liu Q. Therapeutic effect of nerve growth factor on cerebral infarction in dogs using the hemisphere anomalous volume ratio of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Neural Regen Res. 2012;7:1873–1880. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2012.24.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S, Sun J, Li J, Wang L, Hall CL, Dix TA, Mohamad O, Wei L, Yu SP. Acute and delayed protective effects of pharmacologically induced hypothermia in an intracerebral hemorrhage stroke model of mice. Neuroscience. 2013;252:489–500. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.07.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S, Raghupathi R, Saatman KE, MacKinnon MA, McIntosh TK, Graham DI. Continued in situ DNA fragmentation of microglia/macrophages in white matter weeks and months after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:239–250. doi: 10.1089/089771504322972031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won SJ, Kim DY, Gwag BJ. Cellular and molecular pathways of ischemic neuronal death. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;35:67–86. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2002.35.1.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Worp HB, Macleod MR, Bath PM, Demotes J, Durand-Zaleski I, Gebhardt B, Gluud C, Kollmar R, Krieger DW, Lees KR, Molina C, Montaner J, Roine RO, Petersson J, Staykov D, Szabo I, Wardlaw JM, Schwab S. EuroHYP-1 investigators (2014) EuroHYP-1: European multicenter, randomized, phase III clinical trial of therapeutic hypothermia plus best medical treatment vs. best medical treatment alone for acute ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke. 9:642–645. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Writing Group Members, Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Després JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurzelmann MR, Romeika J, Sun D. Therapeutic potential of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and a small molecular mimics of BDNF for traumatic brain injury. Neural Regen Res. 2017;12:7–12. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.198964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao G, Guo Q, Shu M, Xie X, Deng J, Zhu Y, Wan C. Safety profile and outcome of mild therapeutic hypothermia in patients following cardiac arrest: systematic review and meta-analysis. Emerg Med J. 2013;30:91–100. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2012-201120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie YC, Li CY, Li T, Nie DY, Ye F. Effect of mild hypothermia on angiogenesis in rats with focal cerebral ischemia. Neurosci Lett. 2007;422:87–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X, Barreto GE, Xu L, Ouyang YB, Xie X, Giffard RG. Increased brain injury and worsened neurological outcome in interleukin-4 knockout mice after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2011;42:2026–2032. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.593772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Yenari MA, Steinberg GK, Giffard RG. Mild hypothermia reduces apoptosis of mouse neurons in vitro early in the cascade. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:21–28. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200201000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Wang P, Zhao Z, Cao T, He H, Luo Z, Zhong J, Gao F, Zhu Z, Li L, Yan Z, Chen J, Ni Y, Liu D, Zhu Z. Activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 by dietary capsaicin delays the onset of stroke in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Stroke. 2011;42:3245–3251. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.618306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yenari MA, Han HS. Neuroprotective mechanisms of hypothermia in brain ischaemia. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:267–278. doi: 10.1038/nrn3174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Li W, Niu G, Leak RK, Chen J, Zhang F. ATP induces mild hypothermia in rats but has a strikingly detrimental impact on focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013a;33:e1–10. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Wang H, Zhao J, Chen C, Leak RK, Xu Y, Vosler P, Chen J, Gao Y, Zhang F. Drug-induced hypothermia in stroke models: does it always protect? CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2013b;12:371–380. doi: 10.2174/1871527311312030010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Chen TY, Kirsch JR, Toung TJ, Traystman RJ, Koehler RC, Hurn PD, Bhardwaj A. Kappa-opioid receptor selectivity for ischemic neuroprotection with BRL 52537 in rats. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1776–1783. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000087800.56290.2E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Steinberg GK, Sapolsky RM. General versus specific actions of mild-moderate hypothermia in attenuating cerebral ischemic damage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007a;27:1879–1894. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Yenari MA, Sapolsky RM, Steinberg GK. Mild postischemic hypothermia prolongs the time window for gene therapy by inhibiting cytochrome C release. Stroke. 2004;35:572–577. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000110787.42083.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Wang JQ, Shimohata T, Sun G, Yenari MA, Sapolsky RM, Steinberg GK. Conditions of protection by hypothermia and effects on apoptotic pathways in a rat model of permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion. J Neurosurg. 2007b;107:636–641. doi: 10.3171/JNS-07/09/0636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]