Abstract

Every spacecraft sent to Mars is allowed to land viable microbial bioburden, including hardy endospore-forming bacteria resistant to environmental extremes. Earth's stratosphere is severely cold, dry, irradiated, and oligotrophic; it can be used as a stand-in location for predicting how stowaway microbes might respond to the martian surface. We launched E-MIST, a high-altitude NASA balloon payload on 10 October 2015 carrying known quantities of viable Bacillus pumilus SAFR-032 (4.07 × 107 spores per sample), a radiation-tolerant strain collected from a spacecraft assembly facility. The payload spent 8 h at ∼31 km above sea level, exposing bacterial spores to the stratosphere. We found that within 120 and 240 min, spore viability was significantly reduced by 2 and 4 orders of magnitude, respectively. By 480 min, <0.001% of spores carried to the stratosphere remained viable. Our balloon flight results predict that most terrestrial bacteria would be inactivated within the first sol on Mars if contaminated spacecraft surfaces receive direct sunlight. Unfortunately, an instrument malfunction prevented the acquisition of UV light measurements during our balloon mission. To make up for the absence of radiometer data, we calculated a stratosphere UV model and conducted ground tests with a 271.1 nm UVC light source (0.5 W/m2), observing a similarly rapid inactivation rate when using a lower number of contaminants (640 spores per sample). The starting concentration of spores and microconfiguration on hardware surfaces appeared to influence survivability outcomes in both experiments. With the relatively few spores that survived the stratosphere, we performed a resequencing analysis and identified three single nucleotide polymorphisms compared to unexposed controls. It is therefore plausible that bacteria enduring radiation-rich environments (e.g., Earth's upper atmosphere, interplanetary space, or the surface of Mars) may be pushed in evolutionarily consequential directions. Key Words: Planetary protection—Stratosphere—Balloon—Mars analog environment—E-MIST payload—Bacillus pumilus SAFR-032. Astrobiology 17, 337–350.

1. Introduction

Preventing the forward contamination of Mars is required for United States and international space missions (NASA, 2005; Kminek and Rummel, 2015). Yet spacecraft leaving Earth still carry microorganisms on board that are embedded within surfaces, instruments, electronics, and other inaccessible areas that cannot be readily cleaned (Schuerger et al., 2003; Nicholson et al., 2005; Benardini et al., 2014). Complete spacecraft sterilization has not been enforced since the Viking missions. Currently allowable microbial bioburden on spacecraft, while relatively low (Benardini et al., 2014), makes the pristine martian environment vulnerable to contamination. Moreover, future life-detection missions could be threatened by false positives without a better understanding of which microorganisms are most capable of persistence, growth, or replication once delivered to the Red Planet. A recent analysis from the Second MEPAG Special Regions Science Analysis Group (Rummel et al., 2014) identified major knowledge gaps associated with polyextremophiles (microorganisms resistant to more than one environmental stressor), particularly when shielded from UV light on Mars by global dust storms, regolith, or overlying dead microorganisms. Nicholson et al. (2005) and Horneck et al. (2010) reviewed common bacterial adaptations to extreme environments, including sporulation, cell pigmentation, and DNA repair pathways (e.g., homologous recombination and nonhomologous end joining). Nonsporulating bacteria also have various mechanisms with which to resist damaging radiation in the space environment. For example, Deinococcus radiodurans can repair its DNA through homologous recombination (Krisko and Radman, 2013). Other microbes, such as a halophilic Synechococcus species, can shield biomolecules from radiation with exogenous salt crystals (Mancinelli et al., 1998).

Smith (2013) argued that Earth's stratosphere would allow multiple Mars-like conditions to be simultaneously tested if polyextremophilic species could be exposed to the upper atmosphere and returned for analysis. Recent missions have demonstrated the feasibility of transporting biological samples to the stratosphere by using small, meteorological balloons (Beck-Winchatz and Bramble, 2014) and large scientific balloons (Smith et al., 2014). The pressure of the thin and dry stratospheric air around 25–38 km above sea level (ASL) is roughly equivalent to the surface pressure on Mars (0.5–1 kPa). The stratosphere is also a cold and extremely dry environment with elevated levels of ionizing and non-ionizing radiation (Adams et al., 2007; Dachev, 2013; Schuerger and Nicholson, 2016). Relative humidity levels can drop below 1%, and temperatures in the lower stratosphere regularly reach −100°C. Stratospheric radiation is substantially higher (Kylling et al., 2003; Adams et al., 2007; Dachev, 2013) than doses at other frequently visited Mars analog environments, including the McMurdo Dry Valleys of Antarctica (Wynn-Williams and Edwards, 2000) and the Atacama Desert (McKay et al., 2003). Laboratory environmental chamber experiments have been employed in the past to simulate martian conditions (Schuerger et al., 2003; Diaz and Schulze-Makuch, 2006; Tauscher et al., 2006; de la Vega et al., 2007; Moores et al., 2007; Osman et al., 2008; Fendrihan et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2009; Gómez et al., 2010; Peeters et al., 2010; Johnson et al., 2011; Kerney and Schuerger, 2011), but artificial illumination sources do not realistically represent the dynamic nature of sunlight. Moreover, most ground-based simulation studies do not simultaneously create the full range of biological stressors present on Mars (i.e., hypobaria, desiccation, irradiation, nutrient deprivation, oxidation, and low temperatures). Conveniently, Earth's upper atmosphere produces a natural combination of these extreme conditions. Measuring the response and survival of polyextremophilic species in the stratosphere can therefore be used to test Mars forward contamination scenarios.

On 10 October 2015, we flew a balloon experiment to the stratosphere over New Mexico and Texas (United States) that reached an altitude of 31.4 km ASL. The Exposing Microorganisms in the Stratosphere (E-MIST) payload carried known quantities of bacterial endospores (hereafter referred to as “spores”) to the Mars-like environment for 2, 4, 6, and 8 h exposures. We used a spacecraft assembly facility–isolated bacterial strain Bacillus pumilus SAFR-032 for the balloon flight (and subsequent ground experiments). The Gram-positive, aerobic, endospore-forming bacterium is noteworthy for special resistance to desiccating, UV-intense conditions (Link et al., 2004; Kempf et al., 2005; Gioia et al., 2007; Tirumalai et al., 2013). Since the spores used for the balloon experiment were metabolically dormant, exposure to stratospheric conditions resulted in cumulative damage to cellular components that was measurable in the laboratory after the E-MIST payload returned to the ground. Our experimental design was inspired by similar experiments with B. pumilus SAFR-032 spores outside the International Space Station (ISS) (Horneck et al., 2012; Moeller et al., 2012; Nicholson et al., 2012; Vaishampayan et al., 2012).

Sending known quantities of viable, monolayered spores into Earth's stratosphere and making comparisons with unexposed controls allowed us to (1) determine the survival of spore populations using culture-based enumeration methods and (2) assess genomic alterations through a resequencing analysis of surviving spores. We also collected environmental data during the balloon flight and performed supplemental ground UV experiments, with an overall goal of assessing the survivability of B. pumilus SAFR-032 spores in stratospheric conditions that closely resemble the surface of Mars.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial strain description and sample preparation

Bacillus pumilus SAFR-032 spores were also used for the first E-MIST balloon test flight (Smith et al., 2014). A full genome map was available (NCBI, GCA000017885.4 ASM1788v4) with a total of 3819 genes previously identified for the species (Gioia et al., 2007). The strain was safe to work with in the field (Biosafety level 1; no hazard posed to balloon personnel or the environment), and prepared spores were stable in stasis, allowing for simplified mission logistics. Moreover, there was no exosporium or extraneous biofilms/layers associated with spores resulting in straightforward postflight molecular assays (Link et al., 2004; Gioia et al., 2007; Vaishampayan et al., 2012; Tirumalai et al., 2013). Testing SAFR-032 spores also enabled comparisons with past experiments that used the model microorganism (Horneck et al., 2012; Moeller et al., 2012; Nicholson et al., 2012; Vaishampayan et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2014).

We established a spore stock based on previously established methods (Schaeffer et al., 1965; Nicholson and Setlow, 1990; Vaishampayan et al., 2012) by culturing the original isolate of B. pumilus SAFR-032 in Difco nutrient broth and incubating at 35°C, 140 rpm for 16 h. Germinated cells were then transferred to sterile sporulation media with the following nutrients per 1 L sterile nanopure water: 8 g Difco nutrient broth, 1 g potassium chloride, and 0.25 g magnesium sulfate heptahydrate autoclaved together followed by the addition of 1 mL sterile calcium chloride (7.35 g/100 mL), manganese chloride (0.2 g/100 mL), and ferrous sulfate (0.0278 g/100 mL). The culture was incubated for 124 h at 35°C with shaking at 140 rpm. Resultant spores were then divided evenly into 50 mL tubes (containing ∼40 mL of culture each) and submerged into a water bath at 80°C for 15 min to destroy any remaining vegetative cells, followed by centrifugation for 20 min at 9400 RCF. Next, heat-treated spores were washed by resuspension with sterile molecular-grade water, centrifugation, and removal of supernatant. This process was repeated four times. After the final wash, spores were resuspended in 8 mL of sterile molecular-grade water and stored overnight in a cold incubator at 4°C with shaking at 90 rpm. To remove any cellular debris, we repeated the cold incubation and wash cycle three consecutive times. Once completed, the supernatant was removed, and the pellet containing purified spores was transferred to a sterile glass test tube containing 0.5 mL sterile molecular-grade water.

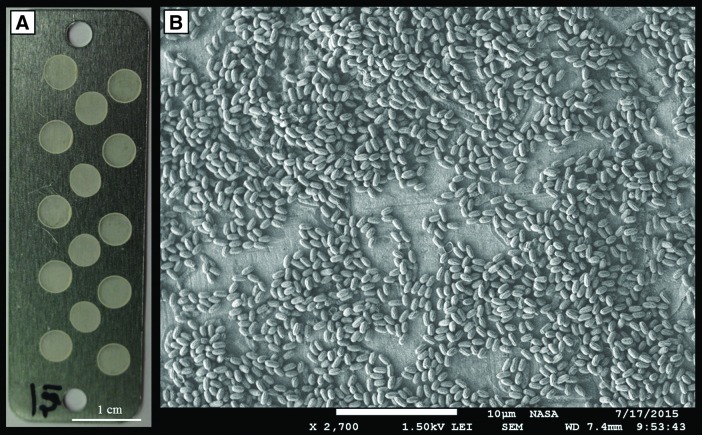

Spore stock concentration was determined to be approximately 6.29 × 109 spores per 1 mL through the most probable number (MPN) method and heterotrophic plate counts. Dilutions from the original stock (20 μL aliquots) were then seeded onto sterile aluminum coupons (M4985, Seton) and dried for 4 h in a dark laminar flow hood at 25°C, creating a layer of 4.07 × 107 spores adhering to coupon surfaces for each individual aliquot. A total of 14 separate 20 μL aliquots were deposited onto any single experimental coupon (5.40 × 1.75 × 0.51 cm) (Fig. 1A). Experimental coupons were created in the same batch, then stored in sterile, dark containers. Dried coupons were imaged with a scanning electron microscope (JSM-7500F, JEOL) to assess the distribution of spores on the aluminum coupon surface (Fig. 1B). Recovery of spores from experimental coupons was achieved through polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) film peels (Horneck et al., 2001; Moeller et al., 2012). Twenty microliters of sterile 10% PVA prepared in water was applied in a thin layer over the dried spores previously deposited onto each coupon. After drying in an incubator for 1 h at 37°C, the PVA film contained embedded spores and was peeled off the coupon with sterile forceps. The PVA film was dropped into a glass test tube containing sterile molecular-grade water and resuspended with a vortexer.

FIG. 1.

(A) An experimental coupon with 14 separate B. pumilus SAFR-032 spore aliquots; each aliquot contained approximately 4.07 × 107 spores total. (B) Scanning electron micrograph of dried B. pumilus SAFR-032 spores distributed within a single 20 μL coupon aliquot.

2.2. Enumeration and resequencing assays

In general, microbial coupons from flight experiments and ground simulations were assayed to (1) determine the number of viable surviving spores (compared to starting quantities) and (2) assess the extent of nonlethal genetic mutations through resequencing (compared to controls and the reference B. pumilus SAFR-032 genome). The MPN enumeration method originally described by Mancinelli and Klovstad (2000) and modified by Schuerger et al. (2003) was used for this study. After incubation at 30°C for 36–42 h, plate wells were scored for growth and calculated to MPN values. To analyze the genome of surviving spores, we followed a protocol from the work of Nicholson et al. (2012). After the PVA peel step, spore suspensions were distributed into 5 mL of recovery media (1:9 ratio of 10 mM L-alanine:2X LB) and then incubated at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm for 60 min allowing approximately one cell replication cycle. Next, germinated cultures were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was removed by pipette, and pellets were resuspended in 1.8 mL of sterile molecular-grade water for DNA extraction with the UltraClean Microbial DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio). Tubes were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 3 min with the exception of the microbead and filter tubes, which were spun at 10,500 rpm. Rather than vortexing the microbead tubes for 10 min, the tubes were placed in a Biospec benchtop minibead beater for 1 min. The extracted DNA was then quantified with a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer and a high-sensitivity DNA assay (Invitrogen). All DNA samples were stored at −20°C. Purities of the spore stock and batch-produced experimental coupons were monitored throughout the study with heterotrophic plate counts and DNA sequencing—no contaminating species were identified.

Sequencing was conducted by using the Illumina Nexterra XT kit (Illumina). First, 1 ng of DNA was tagged with indices followed by a 5 min temperature cycling of 55°C and 10°C to fragment the DNA. Amplification followed, cycling at 72°C for 3 min, 95°C for 30 s, and 12 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. A final elongation step at 72°C for 5 min completed the cycle. Amplified DNA was cleaned with the MinElute PCR cleanup kit (Qiagen) and denatured with 0.2 N NaOH and heating per Illumina Protocol #15044223 Rev B. Sequencing reads were run on the Illumina MiSeq and prepared with the Illumina V2 300 kit. To identify and assemble contigs, data were analyzed with CLC Workbench v 8.0.2 (Qiagen Bioinformatics). The software located single nucleotide polymorphisms in samples compared to the B. pumilus SAFR-032 reference genome. Nucleotide variant type (i.e., deletion, insertion, or substitution) and the frequency across samples were mapped to known coding regions for the strain.

2.3. E-MIST hardware description

Several noteworthy hardware modifications (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2; Supplementary Figures are available at www.liebertonline.com/ast) were made after the first E-MIST test flight described by Smith et al. (2014). Four independently rotating skewers fitted with an adjustable aluminum sample base plate allowed an exposure time series to be established in the stratosphere. Each sample plate held 10 separate aluminum coupons (see Section 2.1). The plates were enclosed within Nomex-lined cylinders to prevent sunlight from entering during the balloon gondola ascent/descent and when the skewers rotated to a closed position for the experimental time series. Each skewer was motor-controlled (SPG30E-300K, Cytron) by a 4-channel motor driver (FD04A, Cytron) held together by an aluminum and polycarbonate frame. Multiple instruments were inside the payload housing, including a GPS unit (SPK-GPS-GS4O7A, S.P.K. Electronics Co.), a radiometer with UV sensors (PMA2100, PMA2107, and PMA2180, Solar Light), and an external humidity and temperature sensor (HOBO, U23-001, Onset). Instrument temperatures were regulated inside the payload with heating pads (5V, WireKinetics). The avionics system (chipKIT Max32, Digilent) used a serial peripheral interface connection to communicate with a micro-SD card (BOB-00544, microSD Transflash Breakout, SparkFun) and a micro DB-9 port (1200-1183-MIL, Digi-Key). A 1080P HackHD camera was controlled by the avionics and recorded imagery throughout the flight. Other major hardware components included an altimeter (MS5607, Parallax), 8.5 W heaters (Omegalux Kapton Insulated Flexible Heater, Omega), and multiple resistance temperature detectors (SA1-RTD-B, Omega). Power was generated by a 14.8v 25.2 Ah lithium-ion polymer battery (CU-J141, BatterySpace). Before flying, the E-MIST payload was subjected to vibration and hypobaric chamber testing to validate system performance. Instruments were recalibrated after testing, and then the payload was shipped to the launch site at Ft. Sumner, New Mexico, where it was mounted onto the uppermost gondola portion of Columbia Scientific Balloon Facility (CSBF) long-duration balloon Test Flight II (#667NT). Prelaunch, landing, and recovery procedures described by Smith et al. (2014) were repeated for this experiment. Prior to installing base plates onto the skewers with B. pumilus SAFR-032 coupons, the inside of skewer canisters were sprayed with sterile air, and payload surfaces were wiped with isopropyl alcohol.

2.4. Experimental design

Ten experimental coupons were attached (in random order) to four separate base plates on the rotatable E-MIST skewers. Each coupon contained 14 identically prepared 20 μL aliquots of B. pumilus SAFR-032 deposited at a concentration of 4.07 × 107 spores per aliquot. This arrangement allowed for a high number of potential replicates per skewer (N = 140). All skewers were opened simultaneously in the stratosphere, then closed sequentially: Skewer 1 exposed samples for 2 h; Skewer 2 exposed samples for 4 h; Skewer 3 exposed samples for 6 h; and Skewer 4 exposed samples for 8 h. Two different sample coupon orientations were established on each base plate to determine the effect of stratospheric conditions with and without sunlight, as follows: (1) nine coupons were mounted upright and exposed directly to sunlight, and (2) one coupon was mounted upside-down (inverted) to prevent illumination. A blank negative control coupon was also located on the payload and used for monitoring potential contamination associated with launch and landing. To measure the possible influence of transportation to the field site and/or delays associated with balloon flight operations, we included two sets of ground controls—coupons that traveled to Ft. Sumner, New Mexico, but were not flown, and another set that remained in the laboratory at Kennedy Space Center (KSC), Florida.

2.5. Ground experiments

To supplement the balloon flight experiment, we used another group of coupons to evaluate B. pumilus SAFR-032 spore resistance to artificially generated UVC conditions in the laboratory. Within a biological safety cabinet (Labgard Class II, Type A/B3, Model NU-600 Series 24, NuAire, Inc.), a 3-D-printed acrylic UV light-emitting diode (LED) test stand (12.0 × 7.5 × 14.1 cm) held experimental coupons at vertical distances of 1–5 cm from the light source (Supplementary Fig. S3). The test stand bridge could vertically move the LED at half-centimeter intervals and change the angle of illumination 45–90° relative to the sample base plate below. A UVC LED (Part # UVTOP270TO39FW, QPhotonics, LLC) with 5.668 V and a maximum current setting at 20.00 mA generated a peak wavelength of 271.1 nm and a spectral width of 10.3 nm. A Light Meter (HHUV254SD, Omega) was used to measure maximum UVC intensities of 0.50, 0.17, 0.090, 0.040, and 0.030 W/m2 for coupons located 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 cm from the LED, respectively. The first ground experiment exposed bacterial coupons (4.07 × 107 spores per aliquot) to UVC at distances of 1–1.5 cm (resulting in 0.50–0.27 W/m2) for durations of 1.3, 6.7, 50, 100, and 240 min. For each run, the angle of incidence for coupon illumination was 90° from the plane of the UVC LED. Samples were enumerated after the UVC exposure by using the MPN procedure described in Section 2.2. A second ground experiment was also conducted with a lower starting concentration of B. pumilus SAFR-032 spores (640 spores per aliquot). Samples were exposed for 15 min at 90° from the UVC LED plane in distances of 1–5 cm (0.50–0.030 W/m2). Next, samples at a distance of 5 cm (0.030 W/m2) were exposed for 0–25 min at 90° from the UVC LED. The final portion of the experiment exposed samples for 15 min at a distance of 5 cm from the UVC LED, but the orientation of the light source was changed to create 45°, 60°, 75°, and 90° angles of incidence relative to the plane of the coupon.

2.6. Statistical analyses

Means and standard errors were calculated for samples from each flight experiment treatment (2, 4, 6, and 8 h). For every group, we sampled three random coupons, with three separate bacterial aliquots processed from each coupon; this provided a total of N = 9 replicates per group. Fewer inverted test coupons were flown (only one coupon per skewer), so samples were enumerated in triplicate. Our UVC ground experiment had five time treatments with N = 9 replicates from each group. The second UVC experiment (with a lower starting concentration of spores) processed samples in triplicate and had independent treatments for time (0–25 min), distance (1–5 cm), and angles of incidence (45–90°). To analyze values from both flight and ground experiments, we ran one-way ANOVA analyses, producing P values at 95% confidence levels to determine whether viability numbers were changing significantly compared to initial quantities. F values were also calculated to estimate the variance of MPN values between and within groups. Finally, a Tukey HSD test compared individual sample group means by using the same confidence level applied to F and P tests.

3. Results

3.1. Description of balloon flight

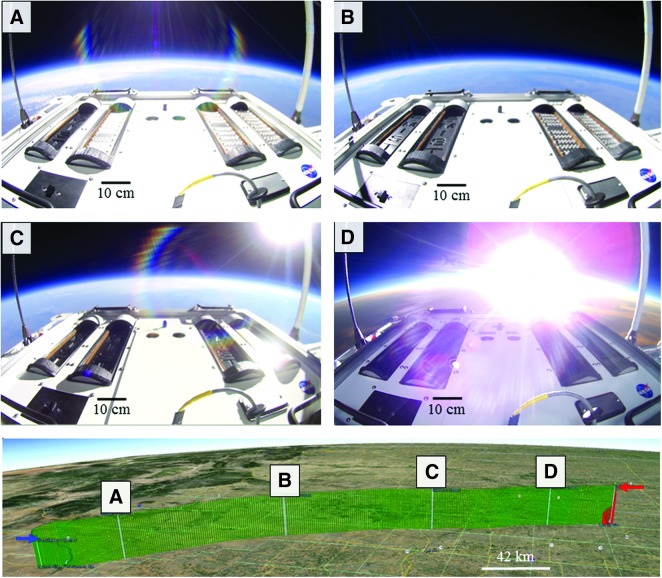

The E-MIST payload was launched on a high-altitude scientific balloon at 1441 UTC on 10 October 2015 from Fort Sumner, New Mexico (34°29'30″N, 104°13'36″W), traveling 335 km to the northeast for ∼11 h, landing just beyond Amarillo, Texas (36°06'30″N, 100°29'30″W). Samples of B. pumilus SAFR-032 spores remained sealed inside the payload until reaching 21.3 km ASL in the lower stratosphere at 1619 UTC, at which point the flight computer rotated the skewers open into the air (Fig. 2). By 1715 UTC, a stable float altitude was achieved, and the payload remained 29.7–31.4 km ASL for a total of 8 h 20 min. The flight computer rotated one skewer to its closed position every 2 h: Skewer 1 closed at 1819 UTC (Fig. 2A), Skewer 2 closed at 2019 UTC (Fig. 2B), Skewer 3 closed at 2219 UTC (Fig. 2C), and Skewer 4 closed at 0019 UTC (Fig. 2D). Environmental data from sensors located inside and outside the E-MIST payload are summarized in Table 1 and Fig. 3. At 0133 UTC (11 October 2015), the gondola was jettisoned from the balloon, returning the payload to the ground on a parachute during a 20 min descent. Personnel from CSBF recovered the payload and transported it back to the launch site facility inside a climate-controlled vehicle. Two days later, flight samples were removed from the E-MIST payload and shipped to the laboratory at KSC (along with unflown ground controls) inside sterile containers at ambient conditions.

FIG. 2.

E-MIST flight path on NASA Balloon Program Flight 667NT. Spots visible on nine experimental coupons per skewer base plate were Bacillus pumilus SAFR-032 dried spore aliquots. Each sample base plate had one inverted test coupon carrying spores shielded from sunlight. The proxy coupon (visible on the lower right portion of the payload) served as a negative control and also recorded temperature. The upper panel shows the gondola at float 31.4 km ASL and the sequential closure of the payload samples at (A) 1819 UTC (Skewer 1); (B) 2019 UTC (Skewer 2); (C) 2219 UTC (Skewer 3); and (D) 0019 UTC (Skewer 4). The lower panel shows ascent, float, and descent trajectory, with skewer closure events labeled across the flight path. The blue arrow marks initial opening of all skewers (at 1619 UTC), and the red arrow marks the start of the gondola descent (11 October 2015 at 0133 UTC). Map credit: “E-MIST Flight Path” 35°20'23.20″N, 102°49'7.15″W. Google Earth. 9 April 2013. 8 December 2015.

Table 1.

Balloon Flight Environmental Conditions

| Max. | Min. | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atmospheric pressure (kPa) | 87.6 | 0.962 | Altitude of Ft. Sumner, NM, 1.25 km ASL |

| Air temp. (°C) | 16.2 | −73.1 | Average air temp. at float was −38.5°C |

| Payload internal temp. (°C) | Internal heaters pulsed during ascent and descent | ||

| Avionics | 23.1 | −13.3 | |

| Proxy coupon | 36.2 | −45.9 | Average coupon temp. at float was 15.4°C |

| Battery | 14.4 | −7.39 | |

| Radiometer | 14.1 | −6.39 | |

| Battery power (V) | 16.7 | 15.7 | |

| RH (%) | 100 | <1 | Average RH at float altitude was 2.32% |

| UV (W/m2) | N/A | N/A | Data were lost; see text for details |

| Ground speed (m/s) | 33.2 | 0.010 | Average speed at float was 13.6 m/s |

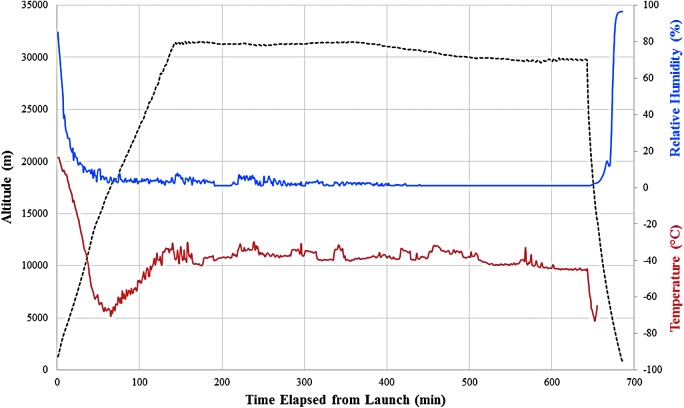

FIG. 3.

Environmental data for E-MIST flight, showing payload altitude (dashed black) with corresponding atmospheric temperature (red) and relative humidity values (blue). The average atmospheric pressure at the balloon gondola float altitude (which ranged from 29.7 to 31.4 km) was 1.07 kPa.

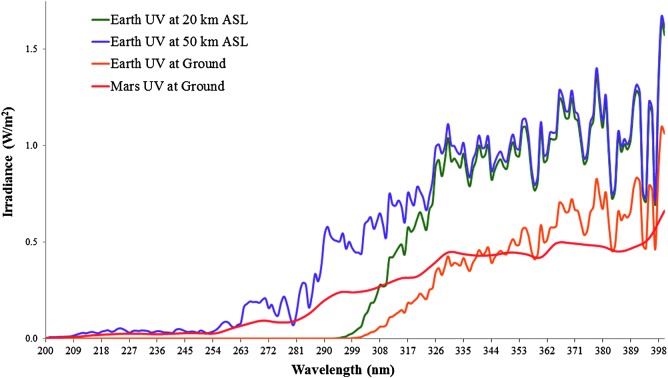

Upon landing, a command to the payload's UV radiometer malfunctioned, preventing the avionics from automatically powering off the instrument. A similar failure occurred during the previous E-MIST test flight (Smith et al., 2014). Briefly, the flight computer received a false indication that the radiometer was shut down; however, the instrument continued to record data until the payload was manually powered down 6 days later at KSC. The radiometer instrument could only store 72 h of measurements. Consequently, the flight UV data were overwritten and unrecoverable. Since a subsequent experiment could not be flown, we remained reliant upon modeling from previously acquired UV measurements in the stratosphere to understand the likely dose of irradiation. To provide a range of expected UV values for the 21.3–31.4 km ASL mission float profile, we constructed a model framed between 20 and 50 km ASL altitudes, based on previous calculations (Smith et al., 2011). Model inputs used the E-MIST balloon flight path latitude (34–36°N) and UV values measured by the Nimbus-7 Solar Backscatter UV instrument that took solar spectra while ascending through the stratosphere in January 1979 (McPeters et al., 1984, 1996). Ultraviolet attenuation was determined by using previously established ozone concentration values acquired in the 30–40°N latitude range by monthly satellite observations (McPeters et al., 2007). Ozone thickness measurements averaged out to 303.1 DU, 214.1 DU, and 0.858 DU for ground, 20 km ASL, and 50 km ASL, respectively, and were converted to absorption coefficient factors for the model. Dosages were calculated to provide a total, instantaneous flux rate (in W/m2) for UVA (315–400 nm), UVB (280–315 nm), and UVC (100–280 nm) with two simplifying assumptions: (1) direct irradiation (i.e., no scattering) and (2) a fixed solar zenith angle of 30°. For the 20 km ASL estimation, we used a temperature of −45°C with atmospheric pressure at 5.57 kPa; for the 50 km ASL estimation, we used a temperature of 0°C with atmospheric pressure at 0.101 kPa. Modeled quantities are summarized in Table 2 and Fig. 4.

Table 2.

Estimated UV Rates (Instantaneous)

FIG. 4.

Modeled UV light conditions in Earth's stratosphere (purple and green) closely resemble modeled irradiation levels on the surface of Mars (red) (data from Schuerger et al., 2003), particularly in UVB/UVC wavelengths (100–315 nm). For comparison, modeled ground UV conditions on Earth (at sea level) are depicted in orange, much lower in UVB/UVC due to atmospheric absorbance.

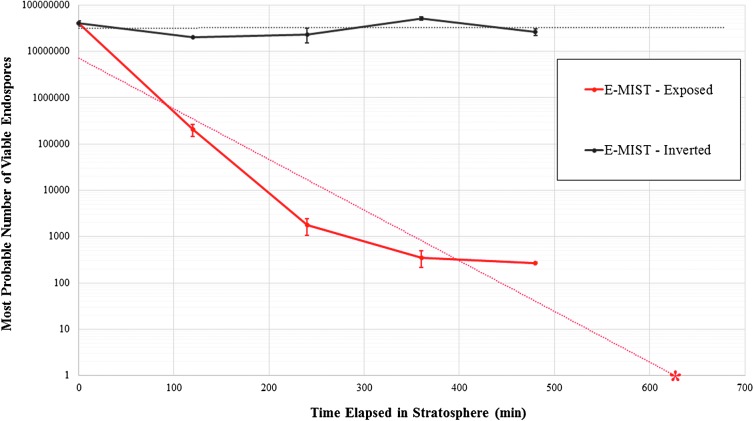

3.2. Survival of Bacillus pumilus SAFR-032

Coupons that were flown to the stratosphere but inverted (shielding bacterial spores from sunlight) did not change significantly over the course of the 8 h experiment (Fig. 5). MPN estimates for inverted flight coupons ranged from 2.00 × 107 to 5.17 × 107 spores per aliquot, which were values similar to transport and ground control coupons (4.02 × 107 and 4.12 × 107 viable spores per aliquot, respectively). In contrast, spores flown to the stratosphere and exposed to sunlight changed significantly across the experiment compared to controls (F = 11.52, P < 0.0001). Coupons exposed for 2 h (Skewer 1) dropped by 2 orders of magnitude to 2.04 × 105 viable spores (N = 9). Rapid inactivation continued, with viable spores declining another 2 orders of magnitude to 1.76 × 103 (N = 9) by the 4 h time step (Skewer 2). The difference between Skewer 1 and 2 samples was significant (P < 0.01). Another 2 h in the stratosphere resulted in a more gradual, though still significant (P < 0.01), inactivation rate with viability values at the 6 h exposure group (Skewer 3) dropping an additional order of magnitude to 353 spores (N = 9). Only 267 viable spores (N = 8), or 0.0007% of the B. pumilus SAFR-032 spore quantity initially seeded onto coupons, were recovered from the final sample set exposed to the stratosphere for 8 h (Skewer 4). One outlier from the 8 h group (MPN value of 8.60 × 103) was discarded due to a suspected MPN processing error. The overall decline (5 orders of magnitude) between control samples and Skewer 4 was strongly significant (P < 0.01); however, the smaller difference between Skewer 3 and 4 groups (86 viable spores, on average) was not significant based on a Tukey HSD test. Notably, none of the sample coupons exposed to the stratosphere for 8 h were completely sterilized. In fact, the lowest viability estimate from a single aliquot processed was 200 spores. To forecast the amount of time in the stratosphere needed for complete inactivation, a trend line was calculated by using the survivability decay rate from exposed flight coupons. Based on this projection, no viable spores would remain if flight samples had an additional 150 min of Sun exposure in the stratosphere (630 min total time).

FIG. 5.

Inactivation rate of B. pumilus SAFR-032 spores in Earth's stratosphere over the 8 h experiment. Note: average MPN values shown on a logarithmic scale. Experimental control coupons contained approximately 4.07 × 107 spores per aliquot. Black values (N = 3 per time group) represent the inverted flight coupons exposed to stratospheric conditions without sunlight; red values (N = 8–9 per time step) show the exposed flight coupons (P < 0.0001). Dashed trend lines were added to the data series, depicting the relative stability of inverted samples and the estimated 630 min required for total inactivation of exposed samples (red asterisk).

When compared to the Sun-exposed stratosphere coupons, the unchanged survival of spores harvested from the inverted stratosphere coupons revealed that UV irradiation was responsible for bacterial inactivation (i.e., not extreme cold, dryness, or hypobaria). Thus, we conducted a series of ground-based UV studies in the laboratory to determine how the initial starting concentration of bacterial spores might influence survivability. Our tests varied the intensity and duration of UVC illumination by changing exposure time, distance from the light source, and incidence angle to coupon surfaces. Samples that were identical to flight coupons (prepared at the same time with a concentration of 4.52 × 107 spores) did not change significantly (F = 3.69, P > 0.01) when illuminated with 0.27–0.5 W/m2 of 271.1 nm UVC for up to 4 h. MPN estimates (N = 9 with each treatment) for exposure times of 1.3, 6.7, 50, 100, and 240 min were stable and generally within standard error ranges at 2.82 × 107, 3.96 × 107, 6.96 × 107, 1.78 × 107, and 1.13 × 107 spores, respectively.

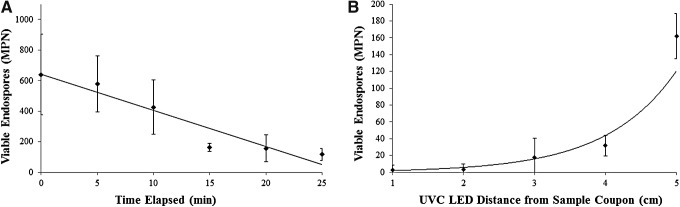

A different pattern was observed for our low-concentration ground tests when using only ∼640 B. pumilus SAFR-032 spores per coupon (N = 3) and exposing samples to 0.03 W/m2 of 271.1 nm UVC. We measured a significant survivability reduction by 15 min (F = 5.41, P = 0.014) and an overall negative correlation (R2 = 0.911) between UVC exposure time and spore viability (Fig. 6A). Not all spores were inactivated at the longest exposure period of 25 min; approximately 117 remained. When the incidence angle of UVC illumination (relative to the sample coupons) was tested at 90°, 75°, 60°, and 45° for experiments in which 0.03 W/m2 of UVC were used, no significant survivability changes between groups were observed (data not included)—all groups declined at a similar rate. In a final 15 min experiment in which the same starting concentration of spores and a 90° incidence angle were used, bacterial inactivation was greater when the UVC light source was closer to the sample coupon (R2 = 0.950) (Fig. 6B). The decline across groups was significant (F = 15.4, P = 0.00028), and viable spores were only recovered from 33% of sample coupons located 1 cm away from the LED.

FIG. 6.

(A) Survivability of B. pumilus SAFR-032 spores exposed to 0.03 W/m2 of 271.1 nm UVC for 0–25 min at 5 cm and 90° angle of incidence (R2 = 0.911; N = 3). (B) Survivability of B. pumilus SAFR-032 spores exposed to 0.03–0.5 W/m2 of 271.1 nm UVC for 15 min at 90° angle of incidence and distances 1–5 cm from LED source (R2 = 0.950; N = 3).

Finally, we performed a scanning electron microscope analysis to better understand the distribution and arrangement of bacterial spores deposited on aluminum test coupons at a concentration of ∼4.07 × 107 spores per 20 μL aliquot (see Fig. 1B). Random areas of the dried bacterial aliquots were surveyed, and the micrographs revealed complete sporulation (i.e., no vegetative B. pumilus SAFR-032 cells) with a predominantly monolayered arrangement of clustered spores on the coupon surface. Where stacking occurred, it generally appeared about 2–3 spores thick. No layering was noticeable for the ground test coupons prepared at a lower concentration (∼640 spores per aliquot). Since MPN enumeration depended upon the full removal of spores from experimental coupons, a subset of test coupons was examined after PVA peel processing to determine whether any spores were left behind; none were observed. In addition, PVA chemistry did not affect the viability of spores—a control test resulted in the same MPN range for identical spore aliquots with and without PVA peels.

3.3. Resequencing of Bacillus pumilus SAFR-032

Using germinated spores that survived the stratosphere (from exposed and inverted sample groups), we performed a nucleotide variant analysis focusing on known coding regions within the B. pumilus SAFR-032 genome. After resequencing the samples, we used the CLC Workbench to identify deletions, insertions, and substitutions compared to the reference genome. The mapping analysis was also done for unflown control coupons. Only B. pumilus SAFR-032 sequences were detected during the sequencing analysis, indicating that microbial contamination was not an issue in the laboratory or field. Resequencing produced a total of 87 nucleotide variants at sample frequencies ranging from 33% to 100%, most of which were from the same coding region: deletions at ABV62232.1 (A/-), ABV62537.1 (T/-), ABV62702.1 (T/-), ABV62978.2 (G/-), ABV63654.1 (A/-); insertions at ABV62978.2 (-/G), ABV63866.1 (-/T); and substitutions at ABV61973.1 (T/G), ABV62475.1 (G/T), ABV62978.2 (C/A), ABV63728.1 (T/A), ABV63728.1 (G/A), ABV63728.1 (C/A), ABV60913.1 (C/T), and ABV61863.1 (C/A). Since these variants appeared with both flight and ground control sequences, we removed them from our analysis in order to focus strictly on unique changes for flight samples. The nucleotide variants—all single base pair substitutions—were observed in the 2 h exposed group [ABV61341.1 (A/T) at 23.8% frequency] and the inverted flight coupon group [ABV63490.1 (C/T) at 39.3% frequency; ABV63868.1 (C/T) at 27.6% frequency]. Upon publication, raw sequencing results will be archived in the NASA GeneLab repository (http://genelab.nasa.gov) for the scientific community to access.

4. Discussion

We conducted a mixture of flight and ground experiments examining bacterial spore survival within a Mars analog environment high above Earth's surface. After enduring intense selective pressures used in spacecraft assembly facilities and with natural polyextremophilic resistance, B. pumilus SAFR-032 spores could be pre-adapted to the harsh conditions of spaceflight and capable of reaching Mars unharmed (Link et al., 2004; Ghosal et al., 2005; Kempf et al., 2005; Gioia et al., 2007; Vaishampayan et al., 2012; Tirumalai et al., 2013). Besides the B. pumilus SAFR-032 isolate, numerous planetary protection studies have documented the diversity of microorganisms on spacecraft surfaces and in clean rooms (Link et al., 2004; La Duc et al., 2009, 2012; Vaishampayan et al., 2013; Benardini et al., 2014). However, without samples returned from Mars, it is not possible to measure the survival of unintentionally introduced terrestrial contamination. Instead, specimens sent to Earth's stratosphere can be analyzed after exposure to a similar environment. Our balloon study challenged B. pumilus SAFR-032 spores to conditions reaching about 1 kPa, −73°C, <1% RH, and UV levels totaling 86.6–109 W/m2 for up to 8 h.

4.1. Flight and ground experiment implications

Flight results reveal a rapid inactivation of B. pumilus SAFR-032 spores in the stratosphere. Viability was reduced by >99.9% after only 8 h of exposure to the stratospheric conditions with sunlight. Spores subjected to identical conditions without sunlight (i.e., inverted flight coupons) did not decline significantly. Thus, we can conclude that solar radiation was the leading factor influencing B. pumilus SAFR-032 spore survival in the stratosphere. Reduced atmospheric pressure, temperature, and water availability were not biocidal to the spores. Our results are consistent with other Mars simulation survivability investigations (Schuerger et al., 2003, 2006; Cockell et al., 2005; Diaz and Schulze-Makuch, 2006; Tauscher et al., 2006; de la Vega et al., 2007; Moores et al., 2007; Osman et al., 2008; Fendrihan et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2009; Gómez et al., 2010; Peeters et al., 2010; Johnson et al., 2011; Kerney and Schuerger, 2011). For instance, Schuerger et al. (2003) showed that monolayered bacterial spores exposed to simulated martian conditions in an environmental chamber were inactivated after 3 h. Collectively, our flight results and other experiments predict a low probability of bacterial persistence on the surface of Mars—provided that contaminating microbes are directly illuminated by sunlight. Even though the solar constant at Mars is only ∼43% that at Earth, the surface of the Red Planet under clear-sky conditions has roughly 3 orders of magnitude higher UV irradiance than the surface of Earth (Cockell et al., 2000; Nicholson et al., 2005), particularly in biocidal UVC wavelengths (100–280 nm). This is due to the rarified martian atmosphere (∼0.7 kPa), with fewer chemical species capable of UV attenuation (Zurek et al., 1992); about 95% of the martian atmosphere is CO2, which leads to solar radiation absorbance more efficiently at wavelengths <190 nm (Kuhn and Atreya, 1979). Nicholson et al. (2005) discussed the resistance and susceptibility of bacteria to UVC and described it as ≥300-fold more effective at damaging DNA and killing bacterial spores than UVB and UVA.

Since short UV wavelengths predominantly determine the fate of microbes delivered to Mars, artificial solar radiation light sources used in past survival simulation studies (Schuerger et al., 2003, 2006; Cockell et al., 2005; Diaz and Schulze-Makuch, 2006; Tauscher et al., 2006; de la Vega et al., 2007; Moores et al., 2007; Osman et al., 2008; Fendrihan et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2009; Gómez et al., 2010; Peeters et al., 2010; Johnson et al., 2011; Kerney and Schuerger, 2011) must be carefully considered. No single lamp or group of lights can fully simulate the spectrum of wavelengths expected at the martian surface. It is also difficult to mimic a drifting solar zenith and hardware surface scattering effects inside the restrictive confines of an environmental chamber. Thus, most ground survival simulation studies bathe microorganisms continuously to radiation at a fixed angle of incidence within a narrow band of UV. Light does not behave this way in nature. Earth's stratosphere can be used to provide a more dynamic illumination with UV doses roughly equivalent to levels expected on the martian surface, as an alternative approach to the inherent limitations associated with laboratory studies. At its mean orbital distance, Mars is thought to have fluence rates on the surface around 3.18 and 8.38 W/m2 for UVC and UVB, respectively (Nicholson et al., 2005). In comparison, the stratosphere UV model developed for this study generated similar levels for UVC and UVB at 20–50 km ASL: 0.00550–5.20 and 4.16–17.1 W/m2, respectively. Our model was consistent within the range of measured values by Kylling et al. (2003), who flew a UV radiometer to 30.5 km ASL in the stratosphere over France (∼44.5°N), recording measurements at 312 and 340 nm across a solar zenith range of 76–94° in flight.

4.2. Significance of bioburden configuration and concentration

Since Mars-bound, robotic spacecraft missions are required to reduce bioburden, lingering contaminants would likely be in low concentrations across hardware components. For instance, the total bioburden on exposed surfaces of the landed Mars Science Laboratory hardware was estimated at 5.64 × 104 spores (22 spores/m2), with only 1.57 × 104 spores estimated on the rover itself (Benardini et al., 2014). Comparatively, our dried 20 μL aliquots contain approximately 41 million spores, which is several orders of magnitude higher than typical bioburden for cleaned spacecraft surfaces. While our concentration could be considered a “nightmare” contamination scenario, we still measured near-complete bacterial inactivation (>99.9%) after 8 h in the stratosphere using one of the most UV-resistant bacterial strains recovered from a spacecraft clean room to date (Link et al., 2004; Gioia et al., 2007; Vaishampayan et al., 2012; Tirumalai et al., 2013). With our experimentally derived kill curve, we forecasted a complete spore inactivation in the stratosphere with only 630 min of Sun exposure.

For our results to be useful for predicting the response of landed Mars bioburden on spacecraft, a few key assumptions would be required: (1) that stratospheric conditions resemble the surface environment on Mars; (2) that a homogeneous monolayer of spores with physiology similar to B. pumilus SAFR-032 would be distributed across spacecraft external surfaces; and (3) that no dust or hardware components shade bacterial contaminants. It is already known that the biocidal effects from radiation are mostly applicable to surface or shallow subsurface contamination (Nicholson et al., 2005). Schuerger et al. (2003) and Cockell et al. (2005) found that the survival of bacteria increased significantly when shielded from UV irradiation by thin layers of dust or rocks. In fact, Chroococcidiopsis sp. 029 retained viability after 8 h under rock coverage only 1 mm thick (Cockell et al., 2005), and B. subtilis survived 8 h of UV irradiation when covered by only a 0.5 mm coating of dust (Schuerger et al., 2003). Similarly, when B. pumilus SAFR-032 spores were combined with 60 μm Mars regolith soils and incubated in a simulated martian atmosphere for 24 h, only a 4-log reduction in viability was reported (Osman et al., 2008). Overlying dead biomass can provide another means of UV shielding to microorganisms in layers below. Orbital experiments outside the ISS concluded B. pumilus SAFR-032 spores were capable of tolerating Mars-like radiation dosages combined with the vacuum of space for 18 months probably due to such shielding (Horneck et al., 2012; Moeller et al., 2012; Nicholson et al., 2012; Vaishampayan et al., 2012). Desiccated layers 2–3 spores thick of B. pumilus SAFR-032 were used for the ISS study (Horneck et al., 2012), and we used the same order of magnitude with our balloon mission to the stratosphere. Predictably, the two experiments had similar outcomes for Sun-exposed spores. Outside the ISS, the B. pumilus SAFR-032 survival rate was less than 10−6 (Horneck et al., 2012). A small, though noteworthy, number of spores persisted in both experiments conducted in the stratosphere and outside the ISS. Either a subset of bacteria was more resistant to biocidal conditions, or more likely, lethal wavelengths of sunlight were attenuated by dead spore layers, clustering, or microscopic pits and cracks in the aluminum coupon surface (Schuerger et al., 2005; Horneck et al., 2012).

To further examine the response of individual spores to irradiation, we performed a standalone UVC experiment with a lower concentration of spores to eliminate layering and clustering. Our starting concentration was the same order of magnitude as balloon flight survivors. The ground experiment showed rapid inactivation within 25 min, even at UVC levels (0.03–0.5 W/m2) lower than what spores would experience in the stratosphere, outside the ISS, or on the surface of Mars. When the same ground experiment was performed for up to 4 h using a higher concentration (4.52 × 107 spores per aliquot), the UVC had no significant effects on viability compared to controls. From these supplementary ground studies, we concluded that the concentration and layering configuration of bacterial spores on sample surfaces primarily determined survivability. It is also worth emphasizing how efficiently UVC LEDs sterilized small amounts of bacterial bioburden in our ground experiment. This relatively new technology could be a low-mass, low-power solution to the problem of spores buried deep within spacecraft hardware, otherwise inaccessible to cleaning efforts and fully shielded from sunlight at Mars. Our single UVC LED produced biocidal action (>95%) within 15 min at distances ranging 1–5 cm from illuminated surfaces. Vehicles someday sent to Mars special regions (Rettberg et al., 2016) could be designed with larger, more sophisticated UVC LED arrays embedded in spacecraft hardware most likely to touch the martian regolith (e.g., drill bits and wheels).

4.3. Genomic consequences of Mars-like conditions on B. pumilus SAFR-032

Spores surviving our flight experiment could have been a stochastic result or beneficiaries of coupon cracks and overlying dead biomass. But another possibility worth examining was whether a genomic advantage enabled persistence. To test this hypothesis, we resequenced surviving B. pumilus SAFR-032 spores to look for nonlethal mutations in coding regions of the genome. Common nucleotide variants from flight and ground samples were identified. After subtracting these variants from the analysis, three single nucleotide polymorphisms remained from the 2 h exposed population at ABV61341.1 (A/T) and the inverted flight coupon population at ABV63490.1 (C/T) and ABV63868.1. The first region, ABV61341.1, is thought to be associated with producing ABC transporter proteins (Gioia et al., 2007). ABV63490.1 is a well-conserved region within Firmicutes and possibly involved with the initiation of sporulation and resistance of bacteria to extreme pH, temperature, and hypersaline conditions. Similarly, ABV63868.1 codes for an amidase protein that may guide sporulation and other metabolic pathways (Gioia et al., 2007; Krulwich et al., 2009). The total number of single nucleotide polymorphisms detected was fairly small considering the genome size surveyed (3.7 Mbp). However, lethal changes to the genome should not have been detected by our assay, which targeted sequences from the surviving subset of spores. Moreover, Bacillus sp. have cellular systems for repairing UV damage to DNA. Spore photoproduct lyase or recombinatorial and nucleotide excision repairs in germinating spores (reviewed by Nicholson et al., 2005) might explain the relatively few nucleotide variants identified through resequencing. While variants were relatively uncommon in our samples, base pair substitutions in three coding regions associated with bacterial sporulation and metabolism do warrant further investigation. Selective pressures in Earth's upper atmosphere, in transit to Mars, or on the surface of the Red Planet could feasibly establish nonlethal mutations that alter bacterial gene pools deposited in new environments. Functional gene changes that result in heightened B. pumilus SAFR-032 resilience were not tested in this study, but comparative transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics are targets of future investigation exploring the molecular basis of polyextremophiles. Intriguingly, previous research has shown that UVC resistance doubled in B. pumilus SAFR-032 spores exposed to the ISS space environment for 18 months (Vaishampayan et al., 2012). Induced mutations to rifampicin resistance and sporulation deficiency were also observed to increase by several orders of magnitude for spores exposed outside the ISS (Moeller et al., 2012).

4.4. Earth's stratosphere as a Mars analog environment

While our study focused on the forward contamination of Mars, Earth's stratosphere also provides opportunities for multicellular biological investigations focusing on the destructive effects of ionizing radiation (Cucinotta et al., 2001; Schimmerling, 2007). In fact, 2 weeks before the E-MIST launch, a suite of ionizing radiation instruments was sent to 36.7 km ASL in the stratosphere from Ft. Sumner, New Mexico (Flight #666N). The Radiation Dosimetry Experiment (RaD-X) measured ionizing dose rates of approximately 0.066 mGy/day with a Liulin LET spectrometer (Mertens et al., 2016). For comparison, recent measurements by the Mars Science Laboratory rover detected an ionizing radiation flux of approximately 0.18–0.225 mGy/day on the surface of Mars (Hassler et al., 2014). Antarctic balloon flights would provide even greater levels of ionizing radiation due to the window of energy-intense particles that penetrate stratospheric latitudes above 70° (Adams et al., 2007). Moreover, circumpolar flights now offer long-duration NASA balloons capable of staying aloft for 100 days (Jones, 2014). Advantages of using the stratosphere as a Mars analog environment instead of ground-based hypobaric chambers, particle accelerator facilities, or orbital experiments in space can be summarized to include (1) seasonal balloon flight opportunities from multiple locations around the world, (2) logistical simplicity with biological experiments (late loading and a rapid return of samples to the laboratory), (3) relative affordability and rapid development compared to other flight-based investigations, and most importantly (4) a realistic, dynamic radiation spectrum naturally paired with other Mars-like conditions (extreme cold, dryness, and hypobaria).

4.5. Limitations and future directions

An unexpected loss of radiometer data from our test flight made a direct analysis between UV levels in the stratosphere and B. pumilus SAFR-032 spore survival unachievable. This includes possible effects of transient shadows cast by the balloon flight train (as the gondola rotated in the stratosphere). Also, total illumination on sample coupons likely decreased as the Sun set on the horizon toward the end of the experiment (see Fig. 2D). The inactivation rate of the spores decelerated with the final two time steps (6 h, Skewer 3; 8 h, Skewer 4), probably due to the setting Sun, but without UV radiometer measurements such direct correlations could not be established in our study. Future missions will aim to fly on a balloon gondola flown in the polar stratosphere at summertime to enable continuous, uninterrupted sunlight and longer-duration exposures. To prevent another UV radiometer command malfunction, backup data will be stored off-instrument. The next-generation E-MIST payload system will also aim to incorporate a dosimeter for measuring ionizing radiation levels in the stratosphere. Until a reflight opportunity for the E-MIST payload, independent radiation measurements from the stratosphere can be used for evaluating the fidelity of the UV model developed herein (e.g., Kylling et al., 2003; Mertens et al., 2016). Our forecast suggested that stratosphere UVB/UVC levels (averaged between 20 and 50 km ASL) would be similar to martian conditions calculated by Schuerger et al. (2003)—approximately 10 and 3 W/m2 for UVB and UVC, respectively, from each modeled environment. This agreement for fluence rates between environments is important because short-wavelength UV is the most effective biocidal wavelength for spore-forming bacteria (Nicholson et al., 2005). While modeled rates from 315 to 400 nm were higher for the stratosphere (∼84 W/m2) than expected on Mars (∼39 W/m2), UVA would not have the same influence on bacterial survival.

Our experiment tested only one spacecraft assembly facility isolate, B. pumilus SAFR-032, due to its unique resistance to environmental extremes, including radiation, and its use in similarly scoped studies (Horneck et al., 2012; Moeller et al., 2012; Nicholson et al., 2012; Vaishampayan et al., 2012). Subsequent flights evaluating other clean-room-archived isolates would be useful to determine which contaminants might be problematic if viably landed on Mars. Since the B. pumilus SAFR-032 response to the stratosphere environment was unknown prior to our balloon flight, we prepared samples at concentrations much higher than what would be reasonably expected for a Mars spacecraft prepared in a clean room. Our results reveal that spore stacking could have prolonged survival for a subset of the stratosphere-flown population. Another limitation of our experimental design was that spores were deposited on a relatively flat metal surface for Sun exposure. Actual spacecraft components where terrestrial contaminants could linger would have a more complex configuration, and the effects of martian dust buffering sunlight are unknown. Consequently, the need for evaluating more complicated, though realistic, bioburden distributions with future E-MIST experiments is a high priority for our team.

5. Conclusion

We observed a >99.9% inactivation for Sun-illuminated bacterial spores exposed to Mars-like conditions in the stratosphere for 8 h. Our starting concentration of viable spores was substantially higher than contamination levels typical for Mars-bound spacecraft, and we used one of the most radiation-resistant bacterial strains known to be in clean rooms; nevertheless, B. pumilus SAFR-032 spores were rapidly killed by sunlight in the stratosphere. Survivors were most likely lingering below layers of overlying dead spores or within small surface defects on the experimental coupons. Our flight results and supplementary ground experiments suggest that the concentration of spores and their distribution on spacecraft hardware primarily determined survival rates. Based on our experimental observations, it seems unlikely that a fully exposed, sunlit bioburden sent to Mars could perpetually withstand the effects of UV radiation at the Red Planet's surface. Using this balloon study in the stratosphere as a stand-in for the martian environment, we predict that most Sun-exposed bacterial contaminants at a level below ∼10,000 spores would be inactivated within 1 sol. Future balloon-based missions in the stratosphere can be used to continue studying other spacecraft clean-room isolates, with and without dust coverage, and at lower concentrations more representative of spacecraft bioburden. Outcomes from such experiments could be used to develop species-specific inactivation models and may reveal genes or cellular mechanisms bestowing exceptional microbial resistance to environmental extremes, including conditions expected on Mars.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- ASL

above sea level

- CSBF

Columbia Scientific Balloon Facility

- E-MIST

Exposing Microorganisms in the Stratosphere

- ISS

International Space Station

- KSC

Kennedy Space Center

- LED

light-emitting diode

- MPN

most probable number

- PVA

polyvinyl alcohol

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the NASA Balloon Program Office (Wallops Flight Facility) and the staff at the Columbia Scientific Balloon Facility for our flight opportunity. Project funding was provided by the Core Technical Capabilities Special Studies at NASA Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Invaluable technical assistance was provided by P. Maloney, A. Dixit, A. Dokos, and A. Bharrat (Kennedy Space Center); R. McPeters (Goddard Space Flight Center); P. Vaishampayan and K. Venkateswaran (Jet Propulsion Laboratory); and A. Schuerger (University of Florida). We are grateful to three anonymous reviewers for their time and constructive feedback.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have no competing financial interest with vendors, reviewers, or organizations used in conducting the research described herein. Any use of trade names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

References

- Adams J.H., Adcock L., Apple J., Christl M., Cleveand W., Cox M., Dietz K., Ferguson C., Fountain W., and Ghita B. (2007) Deep space test bed for radiation studies. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res A 579:522–525 [Google Scholar]

- Beck-Winchatz B. and Bramble J. (2014) High-altitude ballooning student research with yeast and plant seeds. Gravit Space Res 2:117–127 [Google Scholar]

- Benardini J.N., III, La Duc M.T., Beaudet R.A., and Koukol R. (2014) Implementing planetary protection measures on the Mars Science Laboratory. Astrobiology 14:27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockell C.S., Catling D.C., Davis W.L., Snook K., Kepner R.L., Lee P., and McKay C.P. (2000) The ultraviolet environment of Mars: biological implications past, present, and future. Icarus 146:343–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockell C.S., Schuerger A.C., Billi D., Friedmann E.I., and Panitz C. (2005) Effects of a simulated martian UV flux on the cyanobacterium Chroococcidiopsis sp. 029. Astrobiology 5:127–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucinotta F.A., Schimmerling W., Wilson J.W., Peterson L.E., Badhwar G.D., Saganti P.B., and Dicello J.F. (2001) Space radiation cancer risks and uncertainties for Mars missions. Radiat Res 156:682–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dachev T.P. (2013) Profile of the ionizing radiation exposure between the Earth surface and free space. J Atmos Sol Terr Phys 102:148–156 [Google Scholar]

- de la Vega U.P., Rettberg P., and Reitz G. (2007) Simulation of the environmental climate conditions on martian surface and its effect on Deinococcus radiodurans. Adv Space Res 40:1672–1677 [Google Scholar]

- Diaz B. and Schulze-Makuch D. (2006) Microbial survival rates of Escherichia coli and Deinococcus radiodurans under low temperature, low pressure, and UV-irradiation conditions, and their relevance to possible martian life. Astrobiology 6:332–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendrihan S., Bérces A., Lammer H., Musso M., Rontó G., Polacsek T.K., Holzinger A., Kolb C., and Stan-Lotter H. (2009) Investigating the effects of simulated martian ultraviolet radiation on Halococcus dombrowskii and other extremely halophilic archaebacteria. Astrobiology 9:104–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosal D., Omelchenko M.V., Gaidamakova E.K., Matrosova V.Y., Vasilenko A., Venkateswaran A., Zhai M., Kostandarithes H.M., Brim H., Makarova K.S., Wackett L.P., Fredrickson J.K., and Daly M.J. (2005) How radiation kills cells: survival of Deinococcus radiodurans and Shewanella oneidensis under oxidative stress. FEMS Microbiol Rev 29:361–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioia J., Yerrapragada S., Qin X., Jiang H., Igboeli O.C., Muzny D., Dugan-Rocha S., Ding Y., Hawes A., Liu W., Perez L., Kovar C., Dinh H., Lee S., Nazareth L., Blyth P., Holder M., Buhay C., Tirumalai M.R., Liu Y., Dasgupta I., Bokhetache L., Fujita M., Karouia F., Moorthy P.E., Siefert J., Uzman A., Buzumbo P., Verma A., Zwiya H., McWilliams B.D., Olowu A., Clinkenbeard K.D., Newcombe D., Golebiewski L., Petrosino J.F., Nicholson W.L., Fox G.E., Venkateswaran K., Highlander S.K., and Weinstock G.M. (2007) Paradoxical DNA repair and peroxide resistance gene conservation in Bacillus pumilus SAFR-032. PLoS One 2:e928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez F., Mateo-Martí E., Prieto-Ballesteros O., Martín-Gago J., and Amils R. (2010) Protection of chemolithoautotrophic bacteria exposed to simulated Mars environmental conditions. Icarus 209:482–487 [Google Scholar]

- Hassler D.M., Zeitlin C., Wimmer-Schweingruber R.F., Ehresmann B., Rafkin S., Eigenbrode J.L., Brinza D.E., Weigle G., Böttcher S., and Böhm E. (2014) Mars' surface radiation environment measured with the Mars Science Laboratory's Curiosity rover. Science 343, doi: 10.1126/science.1244797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horneck G.P., Rettberg P., Reitz G., Wehner J., Eschweiler U., Strauch K., Panitz C., Starke V., and Baumstark-Khan C. (2001) Protection of bacterial spores in space, a contribution to the discussion on panspermia. Orig Life Evol Biosph 31:527–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horneck G., Klaus D.M., and Mancinelli R.L. (2010) Space microbiology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 74:121–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horneck G., Moeller R., Cadet J., Douki T., Mancinelli R.L., Nicholson W.L., Panitz C., Rabbow E., Rettberg P., Spry A., Stackebrandt E., Vaishampayan P., and Venkateswaran K.J. (2012) Resistance of bacterial endospores to outer space for planetary protection purposes—experiment PROTECT of the EXPOSE-E mission. Astrobiology 12:445–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A.P., Pratt L.M., Vishnivetskaya T., Pfiffner S., Bryan R.A., Dadachova E., Whyte L., Radtke K., Chan E., and Tronick S. (2011) Extended survival of several organisms and amino acids under simulated martian surface conditions. Icarus 211:1162–1178 [Google Scholar]

- Jones W.V. (2014) Evolution of scientific ballooning and its impact on astrophysics research. Adv Space Res 53:1405–1414 [Google Scholar]

- Kempf M.J., Chen F., Kern R., and Venkateswaran K. (2005) Recurrent isolation of hydrogen peroxide–resistant spores of Bacillus pumilus from a spacecraft assembly facility. Astrobiology 5:391–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerney K.R. and Schuerger A.C. (2011) Survival of Bacillus subtilis endospores on ultraviolet-irradiated rover wheels and Mars regolith under simulated martian conditions. Astrobiology 11:477–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kminek G. and Rummel J.D. (2015) COSPAR's planetary protection policy. Space Research Today 193:7–19 [Google Scholar]

- Krisko A. and Radman M. (2013) Biology of extreme radiation resistance: the way of Deinococcus radiodurans. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 5, doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krulwich T.A., Hicks D.B., and Ito M. (2009) Cation/proton antiporter complements of bacteria: why so large and diverse? Mol Microbiol 74:257–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn W. and Atreya S. (1979) Solar radiation incident on the martian surface. J Mol Evol 14:57–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kylling A., Danielsen T., Blumthaler M., Schreder J., and Johnsen B. (2003) Twilight tropospheric and stratospheric photodissociation rates derived from balloon borne radiation measurements. Atmos Chem Phys 3:377–385 [Google Scholar]

- La Duc M.T., Osman S., Vaishampayan P., Piceno Y., Andersen G., Spry J.A., and Venkateswaran K. (2009) Comprehensive census of bacteria in clean rooms by using DNA microarray and cloning methods. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:6559–6567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Duc M.T., Vaishampayan P., Nilsson H.R., Torok T., and Venkateswaran K. (2012) Pyrosequencing-derived bacterial, archaeal, and fungal diversity of spacecraft hardware destined for Mars. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:5912–5922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link L., Sawyer J., Venkateswaran K., and Nicholson W. (2004) Extreme spore UV resistance of Bacillus pumilus isolates obtained from an ultraclean spacecraft assembly facility. Microb Ecol 47:159–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancinelli R.L. and Klovstad M. (2000) Martian soil and UV radiation: microbial viability assessment on spacecraft surfaces. Planet Space Sci 48:1093–1097 [Google Scholar]

- Mancinelli R.L., White M.R., and Rothschild L.J. (1998) Biopan-survival I: exposure of the osmophiles Synechococcus sp. (Nageli) and Haloarcula sp. to the space environment. Adv Space Res 22:324–327 [Google Scholar]

- McKay C.P., Friedmann E.I., Gómez-Silva B., Cáceres-Villanueva L., Andersen D.T., and Landheim R. (2003) Temperature and moisture conditions for life in the extreme arid region of the Atacama Desert: four years of observations including the El Niño of 1997–1998. Astrobiology 3:393–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPeters R., Heath D., and Bhartia P. (1984) Average ozone profiles for 1979 from the NIMBUS 7 SBUV instrument. J Geophys Res: Atmospheres 89:5199–5214 [Google Scholar]

- McPeters R.D., Bhartia P., Krueger A.J., Herman J.R., Schlesinger B.M., Wellemeyer C.G., Seftor C.J., Jaross G., Taylor S.L., and Swissler T. (1996) Nimbus-7 total ozone mapping spectrometer (TOMS) data products user's guide. NASA-RP-1384, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- McPeters R.D., Labow G.J., and Logan J.A. (2007) Ozone climatological profiles for satellite retrieval algorithms. J Geophys Res: Atmospheres 112, doi: 10.1029/2005JD006823 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens C.J., Gronoff G.P., Norman R.B., Hayes B.M., Lusby T.C., Straume T., Tobiska W.K., Hands A., Ryden K., Benton E., Wiley S., Gersey B., Wilkins R., and Xu X. (2016) Cosmic radiation dose measurements from the RaD-X flight campaign. Space Weather 14:874–898 [Google Scholar]

- Moeller R., Reitz G., Nicholson W.L., The Protect Team, and Horneck G. (2012) Mutagenesis in bacterial spores exposed to space and simulated martian conditions: data from the EXPOSE-E spaceflight experiment PROTECT. Astrobiology 12:457–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moores J., Smith P., Tanner R., Schuerger A., and Venkateswaran K. (2007) The shielding effect of small-scale martian surface geometry on ultraviolet flux. Icarus 192:417–433 [Google Scholar]

- NASA. (2005) Planetary protection provisions for robotic extraterrestrial missions. NPR 8020.12 C, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson W. and Setlow P. (1990) Sporulation, germination and outgrowth. In Molecular Biology Methods for Bacillus, John Wiley and Sons, Hoboken, NJ, pp 391–450 [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson W.L., Schuerger A.C., and Setlow P. (2005) The solar UV environment and bacterial spore UV resistance: considerations for Earth-to-Mars transport by natural processes and human spaceflight. Mutat Res 571:249–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson W.L., Moeller R., the Protect Team, and Horneck G. (2012) Transcriptomic responses of germinating Bacillus subtilis spores exposed to 1.5 years of space and simulated martian conditions on the EXPOSE-E experiment PROTECT. Astrobiology 12:469–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman S., Peeters Z., La Duc M.T., Mancinelli R., Ehrenfreund P., and Venkateswaran K. (2008) Effect of shadowing on survival of bacteria under conditions simulating the martian atmosphere and UV radiation. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:959–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters Z., Vos D., Ten Kate I., Selch F., van Sluis C., Sorokin D.Y., Muijzer G., Stan-Lotter H., Van Loosdrecht M., and Ehrenfreund P. (2010) Survival and death of the haloarchaeon Natronorubrum strain HG-1 in a simulated martian environment. Adv Space Res 46:1149–1155 [Google Scholar]

- Rettberg P., Anesio A.M., Baker V.R., Baross J.A., Cady S.L., Detsis E., Foreman C.M., Hauber E., Ori G.G., and Pearce D.A. (2016) Planetary protection and Mars Special Regions—a suggestion for updating the definition. Astrobiology 16:119–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rummel J.D., Beaty D.W., Jones M.A., Bakermans C., Barlow N.G., Boston P.J., Chevrier V.F., Clark B.C., de Vera J.-P.P., and Gough R.V. (2014) A new analysis of Mars “Special Regions”: findings of the second MEPAG Special Regions Science Analysis Group (SR-SAG2). Astrobiology 14:887–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer P., Millet J., and Aubert J.P. (1965) Catabolic repression of bacterial sporulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 54:704–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmerling W. (2007) Overview of NASA's space radiation research program. Gravit Space Res 16:5–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuerger A.C. and Nicholson W.L. (2016) Twenty-three species of hypobarophilic bacteria recovered from diverse ecosystems exhibit growth under simulated martian conditions at 0.7 kPa. Astrobiology 16:335–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Schuerger A.C., Mancinelli R.L., Kern R.G., Rothschild L.J., and McKay C.P. (2003) Survival of endospores of Bacillus subtilis on spacecraft surfaces under simulated martian environments. Icarus 165:253–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuerger A.C., Richards J.T., Hintze P.E., and Kern R.G. (2005) Surface characteristics of spacecraft components affect the aggregation of microorganisms and may lead to different survival rates of bacteria on Mars landers. Astrobiology 5:545–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuerger A.C., Richards J., Newcombe D., and Venkateswaran K. (2006) Rapid inactivation of seven Bacillus spp. under simulated Mars UV irradiation. Icarus 181:52–62 [Google Scholar]

- Smith D.J. (2013) Microbes in the upper atmosphere and unique opportunities for astrobiology research. Astrobiology 13:981–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D.J., Schuerger A.C., Davidson M.M., Pacala S.W., Bakermans C., and Onstott T.C. (2009) Survivability of Psychrobacter cryohalolentis K5 under simulated martian surface conditions. Astrobiology 9:221–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D.J., Griffin D.W., McPeters R.D., Ward P.D., and Schuerger A.C. (2011) Microbial survival in the stratosphere and implications for global dispersal. Aerobiologia 27:319–332 [Google Scholar]

- Smith D.J., Thakrar P.J., Bharrat A.E., Dokos A.G., Kinney T.L., James L.M., Lane M.A., Khodadad C.L., Maguire F., and Maloney P.R. (2014) A balloon-based payload for Exposing Microorganisms in the Stratosphere (E-MIST). Gravit Space Res 2:70–80 [Google Scholar]

- Tauscher C., Schuerger A.C., and Nicholson W.L. (2006) Survival and germinability of Bacillus subtilis spores exposed to simulated Mars solar radiation: implications for life detection and planetary protection. Astrobiology 6:592–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirumalai M.R., Rastogi R., Zamani N., O'Bryant Williams E., Allen S., Diouf F., Kwende S., Weinstock G.M., Venkateswaran K.J., and Fox G.E. (2013) Candidate genes that may be responsible for the unusual resistances exhibited by Bacillus pumilus SAFR-032 spores. PLoS One 8, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaishampayan P.A., Rabbow E., Horneck G., and Venkateswaran K.J. (2012) Survival of Bacillus pumilus spores for a prolonged period of time in real space conditions. Astrobiology 12:487–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaishampayan P., Probst A.J., La Duc M.T., Bargoma E., Benardini J.N., Andersen G.L., and Venkateswaran K. (2013) New perspectives on viable microbial communities in low-biomass cleanroom environments. ISME J 7:312–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn-Williams D. and Edwards H. (2000) Antarctic ecosystems as models for extraterrestrial surface habitats. Planet Space Sci 48:1065–1075 [Google Scholar]

- Zurek R.W., Barnes J.R., Haberle R.M., Pollack J.B., Tillman J.E., and Leovy C.B. (1992) Dynamics of the atmosphere of Mars. In Mars, edited by Matthews M.S., Kieffer H.H., Jakosky B.M., and Snyder C., University of Arizona Press, Tucson, pp 835–933 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.