ABSTRACT

Household food insecurity is linked with exposure to violence and adversity throughout the life course, suggesting its transfer across generations. Using grounded theory, we analyzed semistructured interviews with 31 mothers reporting household food insecurity where participants described major life events and social relationships. Through the lens of multigenerational interactions, 4 themes emerged: (1) hunger and violence across the generations, (2) disclosure to family and friends, (3) depression and problems with emotional management, and (4) breaking out of intergenerational patterns. After describing these themes and how they relate to reports of food insecurity, we identify opportunities for social services and policy intervention.

KEYWORDS: Food insecurity, life course, childhood adversity, intergenerational disadvantage

Introduction

Household food insecurity, defined as a form of economic struggle that includes the lack of access to enough food for an active and healthy life, 1 is associated with negative physical and mental health outcomes in children and adults such as poor child development, 2 , 3 increased hospitalizations, 4 anemia, 5 , 6 asthma, 7 suicidal ideation, 8 depression and anxiety, 9 – 11 diabetes, 12 and chronic disease. 13 Female-headed households have a household food insecurity prevalence rate of 34.4%, and households with young children under the age of 6 have a prevalence of 20.9%. These rates are significantly higher than the national rate of 14.3%. 1 The U.S. household food security measure captures a household or individual’s experience in the previous 12 months; hence, it captures a brief experience in a lifetime. Clearly, food insecurity is a major health issue in maternal and child health, yet life course approaches 14 – 16 most useful in identifying points of disease prevention and health promotion in maternal and child health are rarely utilized in the study of food insecurity. Overall, there continues to be little understanding of how both acute and chronic exposure to food insecurity can have its roots in previous experiences across the life course and how such knowledge can contribute to solutions for preventing household food insecurity.

Through a life course perspective, the qualitative Childhood Stress Study investigated circumstances in which caregivers of young children who reported recent household food insecurity have experienced severe stress during their own childhoods. In an earlier analysis, we found that mothers of young children who report household food insecurity often report that they were exposed to food hardship and other forms of adversity as a child. 17 In this study, we viewed the Childhood Stress interviews through the lens of multigenerational interactions and identified 4 primary themes: (1) hunger and violence across the generations, (2) disclosure to family and friends, (3) depression and problems with emotional management, and (4) breaking out of intergenerational patterns. We investigated these themes and how they relate to reports of recent food insecurity as identified by the Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM) and found that in their own words and assessment, participants suggested that experiences of hunger and deprivation are passed from one generation to the next and that that exposure to violence, trauma, and adversity are significant carriers of poverty across the generations. In our discussion, we also identify opportunities for social services and policy intervention.

Background

Maternal depressive symptoms are associated with food insecurity and with poor child development and behavior. 9 , 18 , 19 Among families with children, food insecurity is associated with psychosocial stress such as maternal anxiety, 18 , 20 clinical depression, 10 , 21 social isolation, 22 and potentially harmful parenting practices. 23 Exposure to food insecurity is a stressor in childhood and has been shown to be associated with poor physical, mental, and psychosocial health among children. 5 ,24– 30 Adolescents who have been exposed to food insecurity are more likely to express suicidal ideation. 8 Recent research indicates that food insecurity is associated with exposure to violence and adversity across the life span, including experiences with toxic stress during childhood and with multiple types of violence in adulthood. 17 ,31– 34 These studies corroborate findings from neuroscience that demonstrate the strong effect of early life experiences on adult health and mental health as well as a variety of social and economic circumstances. 35 Moreover, results from studies utilizing the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) measure demonstrate that controlling for other factors, adverse experiences such as neglect, abuse, and household instability are associated with many major adult diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, depression, anxiety and early mortality, 36 , 37 as well as poor economic outcomes. 38

Adversity and traumatic events that occur in childhood and adolescence have a significant impact on behaviors, choices, and social relationships that extend into adulthood. 39 , 40 Adults who have been exposed to deprivation and violence during critical developmental periods often develop neurological, physical, and behavioral coping strategies that may not be suited to their environments later in life, affecting their relationships, security, and job stability. 41 ,42 Such adversity during childhood is associated with depression, substance abuse, and poor school and job performance. 43 – 46 Exposure to adverse experiences in childhood has also been linked to higher rates of worker absenteeism and stress surrounding work and finances in adulthood. 47 These exposures and their sequelae may also set the conditions for food hardship to pass from childhood to adulthood.

Only a few studies have demonstrated a potential association between childhood adversity and adult reports of food insecurity. As examples, homeless and low-income mothers who experienced sexual abuse in childhood were over 4 times as likely to report household food insecurity compared to women who had not been abused. 48 In this same population, child hunger (as measured by the Childhood Hunger Identification Project) was more prevalent in households in which mothers experienced posttraumatic stress disorder and/or substance abuse. 27 Another study found that mothers in persistently food insecure homes had significantly higher rates of depression, psychotic spectrum disorders, and exposure to domestic violence. 49 These studies suggest that a life course approach, which views food insecurity as an indication of exposure to adversity over many years, and even across the generations, is central to understanding food security. 50 A recent study utilized a life course approach to assess the relationship between major life events, demands, and capabilities and both short-term and chronic food insecurity; however, its focus is on a single generation and it does not specifically address exposure to childhood trauma and adversity. 51

This article presents parents’ views on food hardship and adversity throughout their own lifetimes, with an eye to the generations that came before and how these experiences may affect their own young children, the next generation. As the early childhood experiences of individuals have recently become a clear, high priority area for intervention, the transfer of hunger across the generations is important to consider and understand. Two-generation approaches, which seek to support both caregiver and young child, have been recognized as important mechanisms to break the cycle of poverty and poor health. 52 Understanding how and why current caregivers came to be in their challenging circumstances, circumstances that often extend back to their own childhoods, contributes to our knowledge about how to provide support.

Methods

Recruitment

Thirty-one Childhood Stress Study participants were recruited from the outreach database of a large ongoing food insecurity study with caregivers of young children taking place in a Philadelphia children’s hospital emergency department. 53 Outreach is offered to each study participant who requests additional services. Outreach participants who had reported food insecurity within the previous 2 years were invited with a mailed flyer to participate in semistructured in-home interviews for the Childhood Stress Study. Respondents to the flyers called the offices of the researchers to sign up for interview times. Eligibility for the Childhood Stress Study was limited to English- or Spanish-speaking primary caregivers of a child under age 6 from households that reported low or very low food security at the household level with the HFSSM, as indicated in the ongoing food insecurity study. With the assistance of the research coordinator of the original study in the emergency department, food security status was tracked but not revealed to the Childhood Stress interviewers to reduce bias in interview questions regarding adversity. The recruitment methods ensured that of the 31 participants, approximately half identified their children as food secure and that the other half identified their children as low or very low food secure.

Data Collection

Interviews for the Childhood Stress Study were primarily conducted in participants’ homes, with a few conducted in the interviewers’ offices or at another location, such as a local library, as requested by participants. The Childhood Stress interview was audio-recorded and lasted between 1.5 and 3 hours. Interviews began with a survey that asked about demographics, health, and food insecurity, and then moved on to semistructured interview questions. The first portion of the interview consisted of a brief survey to gather demographic information, public assistance participation, employment characteristics, as well as food security status, depressive symptoms, and ACEs. The 18-point HFSSM was utilized to measure household and child food security following categorization methods developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. 54 Depressive symptoms were measured using a 3-item screening tool 55 that assesses feelings of depression over 3 time intervals: at least 2 days in the past week, at least 2 weeks in the past year, or at least 2 years over the life span. The variable was categorized into presence or absence of depressive symptoms, where depressive symptoms were indicated by affirmative response to at least 2 questions. ACEs were assessed using the 10-item retrospective questionnaire, encompassing experiences of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse; physical and emotional neglect; and household factors such as incarceration of a household member or witnessing domestic violence. 36 ,56 A cumulative score was calculated based on the number of affirmative responses. Report of 4 or more ACEs is associated with significant adverse health and economic outcomes. 36 ,38, 57 – 59

The semistructured portion that followed was informed by the responses in the previous survey portion and included multiple follow-up questions for clarification and rich description. This portion of the interview investigated the quality and characteristics of childhood experiences with deprivation, abuse, and neglect; experiences with education and employment; history of participation in public assistance programs; and experiences of hunger during childhood, as an adult, and among participants’ children. Qualitative descriptions of hunger included descriptions of mental and physical effects of not having enough food, psychosocial effects of inadequate food such as worry and stress, and coping strategies during times when families did not have enough money for food, which we characterize as food hardship. These descriptions of food hardship supplemented the information on the standard measure of food insecurity collected during the quantitative survey. To facilitate the process by which participants recalled these events, interviewers drew a timeline divided into 5-year increments of each participant’s life span. Throughout the interview, this timeline was filled in to capture events and contextual information in collaboration with participants. Participants were encouraged to begin describing whichever time period they preferred, focusing on major life events and experiences occurring in those years. Sample qualitative questions included the following: Between the ages of 5 and 10, what was the food situation like for your family? Did you usually have enough to eat? With whom were you living at this time, and can you describe your family relationships? How did your experiences with abuse [and/or hunger and/or neglect as captured in the ACEs survey] affect your experiences in school [/in relationships /with your family]?

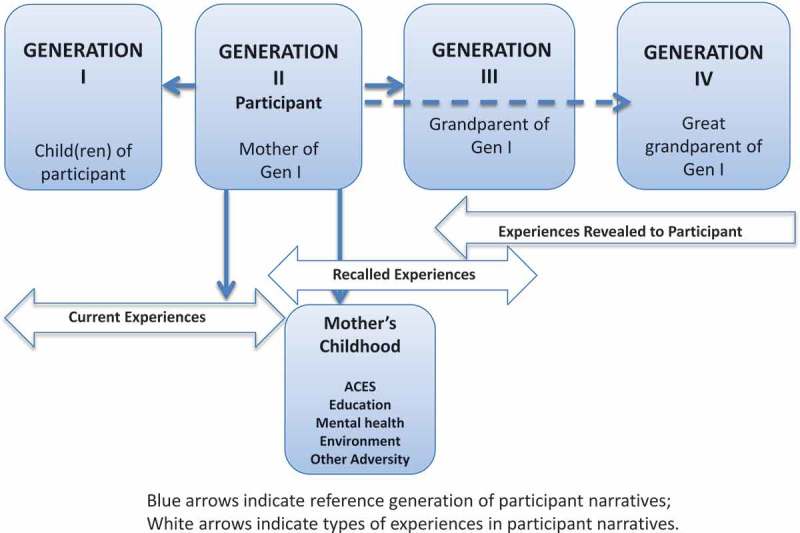

Although questions during the semistructured interview were focused on participants’ experiences throughout their own life spans, many participants brought up their parents’ and grandparents’ experiences unsolicited, at which point we asked follow-up questions to elicit more details. In addition to describing their relationships with their young children, participants described experiences from their own childhoods, including experiences that they had witnessed, such as substance abuse or domestic violence involving a parent or grandparent. In over half of the interviews, participants described experiences that they had been told about by their own parents about their parents’ childhoods and their grandparents’ lives or they heard or witnessed directly from their grandparents (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Participant descriptions of economic hardship and adversity across the generations.

Analysis

Interviews were professionally transcribed and entered into ATLAS.ti Version 7 (Scientific Solutions, Berlin, Germany), a qualitative research software system designed to assist in the management and analysis of qualitative data, ranging from storing and retrieving interview data and quantitative data, to theme coding and theoretical modeling. We utilized a grounded theory approach 60 ,61 through cross-comparison analyses based on themes that emerged from participant narratives. These methods are described in a previous publication. 17 In this investigation, we coded and analyzed exposure to adversity across the life span and coded each major event according to the family members and generations involved for each participant, as well as the life stage, relationship to participant, and impact of each event from participants’ perspectives (Table 1.).

Table 1.

Selected codes and subcodes utilized for constant comparative analysis.a

| Code family | Subcodes |

|---|---|

|

Trauma and adversityb |

|

| Adverse childhood experiences (based on ACE quantitative, including qualitative, follow-up descriptions) |

Physical and emotional abuse; physical and emotional neglect; sexual abuse; witnessing domestic violence; parental separation; substance abuse, mental health condition; incarceration of a household member |

| Violence (qualitatively described) |

Assault/beating; fighting/argument; gun violence; homicide; intimate partner violence; community violence; racism/prejudice; rape/molestation; abuse; neglect; self-harm; threats of violence |

| Hunger (qualitatively described) |

Physical/mental/social sensation; coping strategies; appetite; cutting/skipping meals; nutrition (food access, quality, or choice) |

| Homelessness (qualitatively described) |

Homelessness (shelters, house-to-house, on the street); running away/leaving home; kicked out of home; housing instability |

| Economic hardship (qualitatively described) |

Financial struggle/stress; job/income dissatisfaction; maintaining a job/unemployment |

| Mental health (qualitatively described) |

Mental health diagnosis; anxiety/panic; depression; anger/“ready to fight”; stress; pain; numb/no emotion; self-harm; suicide; substance abuse/addiction; self-medication; mental health care; coping |

|

Generation involved | |

| Child’s generation (G I) |

Participants’ children, nieces/nephews |

| Participant’s/mother’s generation (G II) |

Participant, siblings, cousins |

| Grandparents’ generation (G III) |

Participants’ parents, aunts, uncles, cousins |

| Great-grandparents’ generation (G IV) |

Participants’ grandparents, great-aunts, great-uncles |

|

Characteristics of adversity | |

| Life stage |

0–5 Early childhood; 6–10 late childhood; 10–15 early adolescence; 15–20 late adolescence; past adulthood; current adulthood; prior generations |

| Locus |

Victim; perpetrator; among children; close others; distant others |

| Impact | Casually recalled; fear of event; short-lived impact; long-lasting impact; life-changing impact |

aACE indicates adverse childhood experiences.

bCocoded by generation involved and characteristics of adversity.

The life stage, relationship, and impact coding and analysis method was developed through previous qualitative analysis on exposure to violence in the context of narratives about poverty and public assistance. 31 There were multiple instances where participants described experiences as told to them by their parents and other relatives, and we categorized these by generation as well. As an example, if a participant’s parent witnessed her mother experiencing intimate partner violence during her parent’s childhood, the experience was categorized as involving the parent (GEN III) and grandparent (GEN IV).

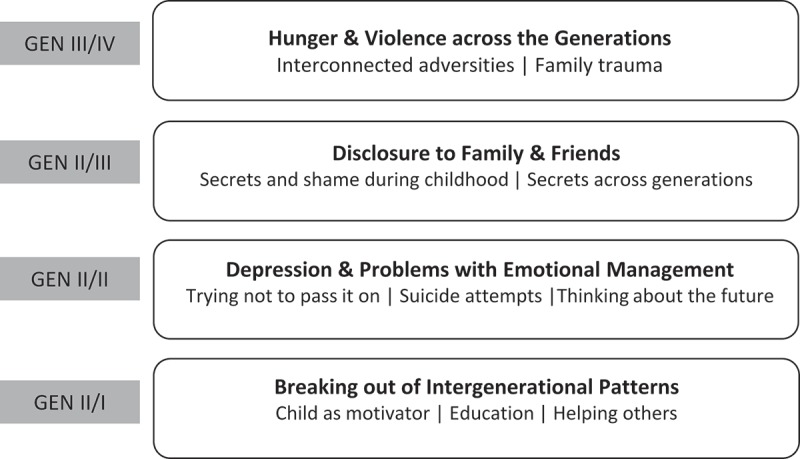

After we categorized and analyzed the data through the filter of the cocoded generations involved in the narratives and the life stage in which events took place, 4 primary categories of themes emerged: (1) hunger and violence across the generations, (2) disclosure to family and friends, (3) depression and problems with emotional management, and (4) breaking out of intergenerational patterns.

All participants are identified by a pseudonym. Any words omitted for clarity and length, such as repeated phrases or words such as like and um, are indicated by an ellipsis enclosed in brackets. Rephrases and pronoun clarifications that do not change the meaning of the quotation are enclosed in brackets.

Results

From the quantitatively assessed results, among the 31 participants, 12 reported low household food security and 19 reported very low food household security. Sixteen reported that their children were food secure, 11 reported low child food security, and 4 reported very low child food security. Over three quarters of participants reported maternal depressive symptoms, two thirds reported 4 or more ACEs, and nearly a third reported an ACE score of 8 or 9, indicating extreme severity of cumulative adversity. Aside from losing a parent to divorce or abandonment, the categories of childhood adversity with the highest prevalence were exposure to substance abuse (65%) and emotional neglect (58%). Additional demographic data can be found in a previous publication. 17

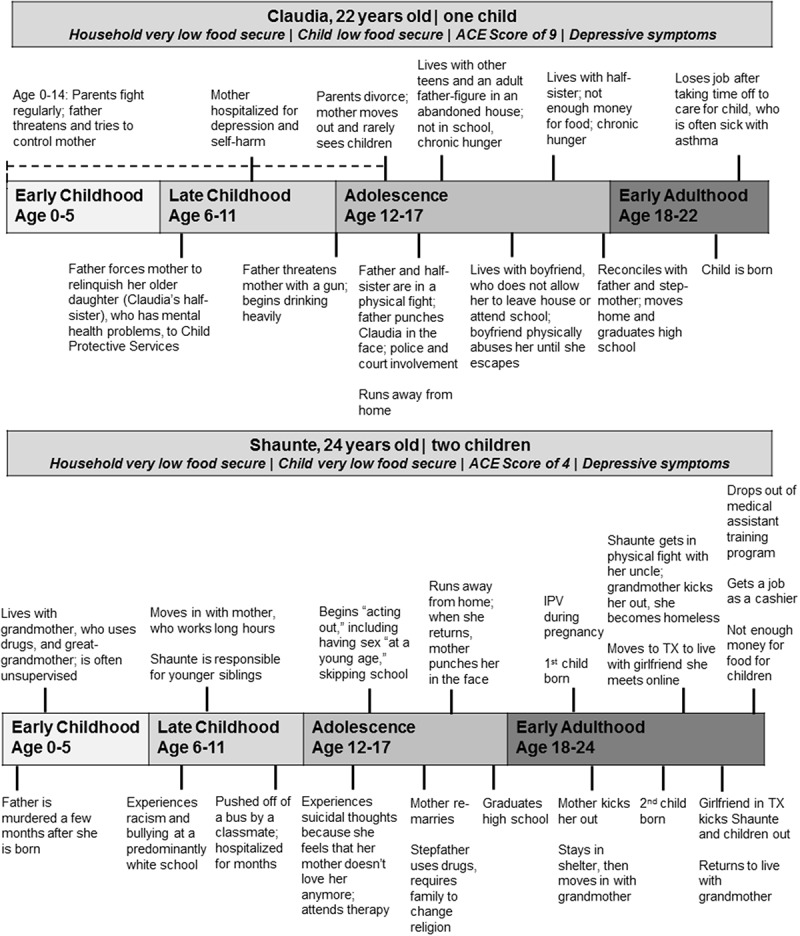

Through coding of all qualitative portions of the interviews and placing significant experiences on a timeline in partnership with the participant, we found that those who reported very low food security were more likely to qualitatively describe experiences with adversity during their childhoods, and across more generations. The recorded interviews also challenged some of the assumptions of the quantitatively assessed ACEs question focused on physical neglect. This question consists of the following: “Before the age of 18, did you often or very often feel that you didn’t have enough to eat, had to wear dirty clothes, and had no one to protect you? or Your parents were too drunk or high to take care of you or take you to the doctor if you needed it? Three participants, out of the 12 who responded affirmatively to not having enough to eat as a child, described how they often did not have enough to eat or had to wear dirty clothes as a result of economic hardship faced by their families and were careful to clarify that their caregivers did not use drugs or alcohol. Additionally, the interviews elicited other types of adversity and harmful exposures that are not captured by the ACEs. These include suicide attempts, witnessing gun violence in the extended family and in the community, experiencing homelessness as a child, and running away from home. Two sample timelines are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Sample timelines developed with participants during interview to focus narrative on life course.

Table 2 shows adverse experiences of all participants as they were reported across 4 generations, in reverse chronological order from left to right from GEN I to GEN IV, showing (1) food security status of each participant’s child, (2) the participant’s experiences in adulthood and childhood, (3) her parents’ experiences during her childhood and before she was born, and (4) her grandparents’ experiences. This table depicts many but not all types of adversity for each participant, their children, and the preceding generations, from both quantitative and qualitative data sources. Table 2 identifies individual reports of adversity from survey results for food security status, depressive symptoms, and ACEs; as well, it identifies reports of adversity that were described in the qualitative portion of the interview which include current experiences of intimate partner violence and substance abuse; childhood experiences of homelessness and participant suicide attempts; parents’ recounted early life experiences of abuse, neglect, and economic hardship; and grandparents’ recounted experiences of substance abuse, exposure to violence, and economic hardship. Only one participant (Cheyenne, age 21) reported child food insecurity on the HFSSM without also qualitatively reporting exposure to violence, one of the ACEs experiences, or intergenerational exposure to adversity.

Table 2.

Adverse experiences across 4 generations.

|

As a whole, participant timelines show patterns of transfer of hunger and violence across the generations, from participants’ parents and grandparents through the participants’ children. Theme analysis of participants’ descriptions of hunger, violence, and adversity over multiple generations yielded 4 major themes related to childhood exposure to violence, adversity, and hunger and how intergenerational transmission of disadvantage is recognized, exacerbated, or prevented. These self-reflective narratives demonstrate that participants recognize that food and economic hardship have “roots” that feed or starve the next generation; that not feeling empowered to disclose adversity to family and friends destroys trust and can allow the adversity to continue; that such experiences have very negative mental health consequences that parents try to prevent from transferring to their own children; and, finally, that multiple participants are inspired by their children to stop the intergenerational transfer through providing love and nurturing support, improving their educations, and through helping others. See Figure 3. Overall, these major themes reflect that the participants recognize patterns in their families and that they have the desire and, oftentimes, the ability to disrupt these patterns for their own children.

Figure 3.

Primary themes on the intergenerational transfer of food insecurity.

1. Hunger and Violence Across the Generations: “If the roots is damaged …”

Most participants described how their current economic stress predated their adulthood. They explicitly detailed how their current hardship had roots in their childhoods and thus reflected the hardships that their parents experienced. Most participants could not disentangle hardships such as exposure to violence, abuse, and hunger but often described such experiences as a composite of related experiences. Participants described how these interconnected adversities had major consequences for their current lives, and many described how trauma within their families carried across generations.

Interconnected Adversities

Karina (ACE 7, household very low food secure, child low food secure), a 35-year-old mother of 3, described the experiences as intertwined. She explained,

You cannot ask a person, “Why are you stressing?” You cannot ask a person, “Why is there so much violence here?” You cannot ask a person, “Why are you hungry?” All three go together. No matter how you see it, all three go together. I could be here like, “Okay, I’m stressing because I don’t have no food, and it’s violent because I’m fighting my husband because we need money.”

Karina identified childhood experiences of violence and hunger at the roots of her current circumstances. She described how her stepfather’s drug use and violent behavior affected her as a child. She explained that he often stole from her mother and they consequently ran out of money for food. Although she described social support from other relatives, who provided meals and emotional support, Karina recognized that the stress of financial hardship and threat of violence in her home accompanied her over the course of her life. Karina explained,

It’s like the tree. The tree: it will grow from the roots. So, if the roots is damaged, the tree is going to be damaged. You know? So that’s my tree. Like, my home was rotted by a bad person. And now, it escalated in my life.

Karina’s description of the roots suggests that current experiences among families reporting food insecurity are related to how caregivers were treated by their own parents and grandparents.

As seen in Table 2, many participants reporting current very low food security in response to the HFSSM also reported significant current and/or previous exposure to adversity and violence. Tamira (ACE 9, household very low food secure, child low food secure), a 22-year-old mother of a toddler, traced her difficulties in school and inability to find or maintain a job to being mistreated by her mother and grandmother. After her mother abandoned her at age 5, Tamira experienced physical and sexual abuse from the family in whose care she and her sister were entrusted. Although her grandmother took her in after learning of the abuse, Tamira continued to be abused and neglected by her grandmother until she reached age 15, when her grandmother kicked her out of the house. Tamira explained how her exposure to abuse and trauma affected her behavior and her life circumstances from a young age through adolescence.

I had an attitude problem. I got touched. I’m not going to be the same little girl. Like, nobody’s going to be the same. So I had an attitude. But it’s not my fault. I was a little girl. And, like, when I got in trouble [when living with my grandmother] she’d put me on punishment and she’d say I can’t come outside. I can’t come downstairs—only to eat, when she’d tell me to eat. She did all types of stuff […]

She’d be like, “You can’t come downstairs to eat. You only can eat when I say so.” And I’d be, like, “Grandma, I’m hungry.”

“You heard what I said!” And then she’ll try beating me or she’ll throw something at me.

Or, when I had gotten of age, she put me out. You don’t put anybody that you love out. I’ve been on my own since I was fifteen—sleeping outside, not knowing if I’m going to wake up tomorrow, not knowing anything.

Tamira described chronic homelessness since her adolescence, coupled with hunger and serious depression. Like Tamira, each participant who described running away explained how it was related to being emotionally, physically, or sexually abused (see Table 2).

Family Trauma

Several participants described feelings of betrayal by their families, the people who were meant to love and protect them the most. Claudia (ACE 9, household very low food secure, child low food secure), reporting physical and emotional abuse from her parents, who struggled with alcoholism and mental illness, described the betrayal through imagery:

This is how I’d put it. You see a little girl with a dress with her hands on her back and then you see a guy with all black clothes with his hands on his back. Who do you think is holding the weapon? The guy with the black, right? You would figure it’s him, that he’s the enemy. But really, they’re the ones holding the flower. And the little girl is the one holding the weapon.

Interviewer: Who is that little girl holding the weapon?

She represented my family, basically.

This betrayal and mistreatment by family members was described as causing serious emotional and physical pain. Several participants also described the experience not only among their own immediate families but also among prior generations. Taleya, a 39-year-old mother of 2 (ACE 9, household low food secure, child food secure), explained the relationship between violence, stress, and hunger that she experienced by acknowledging how her own parents and other family members also must have suffered. Taleya expressed both resentment and understanding for her mother, whom she believed was replicating her own childhood experiences. She described how her mother was neglected by Taleya’s grandmother, whom Taleya described as frustrated by limited educational opportunities and having children at a young age. Taleya explained,

You have to acknowledge [my mother and her sisters’] hurt and their pain, you know? There’s things that [my grandmother] didn’t do right, too, you know? It trickles down generations. That’s what happens. And, if you aren’t aware, it’s going to continue, you know? My mom, she wants that mother, just like me. And I told her that.

I said, “You’re looking for the same thing I’m looking for. If you look at me, I’m you. Like, why put me through the stuff that you know you’ve been through as a child?”

She continues to describe how she makes choices so that her own kids do not struggle as she did, but she acknowledges that it involves risk-taking:

You know, if your child’s hungry, you’re going to do whatever you got to do to, you know? And you’ll just take the consequences. You know what I mean? And that’s how it is. It’s like, I don’t want my child to be in the dark.

Other participants would describe their childhood experiences as being conditioned by their family environment. They recognized they were affected by the environment they had accepted as “normal” during childhood and had come to question as they matured. Jocelyn (ACE 9, household very low food secure, child food secure), a 20-year-old mother of one who reported abuse, neglect, and exposure to substance abuse, described how it affected her behavior:

My mother would come home and clean. And then when we’d come home from school, she’s cussing us out ’cause the house wasn’t clean. But no one taught us how to clean, so it was. … That’s not normal. Like, not having a bedtime is not normal. Not communicating without yelling is not normal. That’s why I be trying to figure out why I yell so much. But [I see now,] that’s why. It’s just that’s the only way I knew how to communicate, was screaming.

Participants described these experiences of childhood as formative and lasting, fostering the development of coping strategies that may have helped them in their early environments but were sometimes less useful as they grew older and left home.

2. Disclosure to Family and Friends: “Nobody knows me for real …”

When participants described their experiences with adversity during childhood, especially experiences with sexual abuse, most reported that they struggled with the decision to disclose abuse to family, friends, or other adults. They described how revealing the abuse was often a painful reflection of family dynamics, concerns for safety, low self-esteem, and “bottling up” emotions. In the case of Claudia, who described her family as looking as if they would be helpful, the betrayal and lack of trust were so profound that trusting anyone seemed impossible. For this reason, describing her experiences was a dangerous proposition.

Secrets and Shame During Childhood

Participants reported a mix of views on how and whether to disclose exposure to abuse, neglect, and household hardship. Some participants in our study describe the need to keep the abuse a secret, whereas others described the negative outcomes that occurred when they revealed what had happened. For instance, Naitana (ACE 9, household very low food secure, child low food secure) described how her foster mother became angry with her when Naitana told her mother how her new husband raped her at age 14:

She was mad. She’d be like, “Oh, I just got married, why are you doing this to me?” [She was] blaming me for everything. […] I’m like. “Well I’m going to say something, because I just can’t live like that.”

And then when I told her, it was like she was yelling, cursing at me, “You’re a whore and you’re just doing that because you want money. But you ain’t getting it here. How could you do that? If it wasn’t for me, you would not be here, da, da, da, da.”

I was just like, “You know what? I’m leaving. I can’t take this. I don’t feel appreciated. I don’t feel caring.” I just got tired, and I left and never turned back.

Tamira, who was abandoned by her mother at age 5 on a doorstep of a neighbor and subsequently raped by the neighbor’s son, described how afraid she was to tell because he threatened to kill her.

I was scared to tell. […] He said he was going to kill me. […] I was six. I mean I didn’t know. I really didn’t know like if I could. I would have told sooner. I would have done things a lot different, but it’s, like, I was six. What is a six-year-old supposed to do? I can’t fight anybody. I was afraid to tell because I didn’t know if he would kill me. He might have, he was already touching me. So what makes me think you aren’t going to try to kill me or something?

Her grandmother would sometimes come by to visit her and, after recognizing her strange behavior, took her to a doctor to whom she revealed the ongoing rape. After her grandmother took her and her sister from that house, she continued to mistreat Tamira. As a result, she explained how she feels ashamed of her circumstances and typically coped by suppressing anger and painful feelings, even through adulthood.

I smile and [people] just think I got a job; I’m doing good. Nobody knows me for real. That’s why it makes me mad, because it’s like, what you all see you really don’t know. I smile to hide the pain I’m going through every day. I don’t let you all see that. Then that would give you something to talk about even more. So it’s like I don’t open up to them. So it’s like for me to just open up to you to tell you my business, that’s embarrassing to me for real, for real. I don’t have a mom, that’s embarrassing. […] I keep all my secrets inside. I keep a lot of stuff bottled up inside of me.

Others described worrying that if they revealed what was happening to them, not only would their own safety be in jeopardy but other people would get into trouble, causing more violence. Keisha (ACE 9, household very low food secure, child very low food secure) described how she never told anyone that she had been sexually abused by a cousin because she was afraid and ashamed. Long after the fact, she worried that if she told her boyfriend, he would find and kill her cousin.

I never told nobody. I never told my boyfriend or none of that, ’cause my boyfriend would probably kill the boy. I don’t know. I never told his family. You [the interviewers] are the first people I’m telling.

Secrets Across Generations

These types of secrets could be carried across the generations as well. Emilia (ACE 6, household very low food secure, child food secure) described how she was raped by her grandfather and then later found out at her grandfather’s funeral that he had also raped her own mother and her mothers’ sisters. When Emilia had revealed the rape soon after it happened when he was still alive, her mother told her to keep the rapes a secret.

My mom never wanted to tell me, because she was molested by her father, too. […] A couple of years back when I talked about it, I found out that she was like … she started crying. She said she didn’t want to talk about it, because she was molested by her father, too. [She said,] “That’s in the past; leave it in the past.”

Almost all of the 13 participants who described sexual abuse described how the abuse deeply affected them into adulthood and reported that this past was still quite present in how they slept, ate, got through the workday, and had relationships with others. The primary result of such adversity from their perspective was immediate and long-term depression.

3. Depression and Problems With Emotional Management: “I felt dead to the world …”

Depression, sadness, and anxiety were a backdrop of most participants’ experiences, especially among those who described having to keep their pain during childhood to themselves due to fear and lack of trust. How the depression manifested and what each caregiver reported doing about it varied. For instance, several participants described significant difficulties in managing emotions, such as anger, shame, guilt, sadness, and fear, and those difficulties often led to significant social disruption. Some explained that they had early sexual relations with multiple partners, and others described self-medicating with marijuana or alcohol. Still others described isolating themselves, self-cutting, suicidal thoughts, and suicide attempts. Most caregivers who reported depression expressed worry about how that depression would transfer to their children.

Trying Not to Pass It On

Emilia described how she was angry and depressed in response to her childhood experiences with sexual abuse and emotional neglect, in addition to the murder of her boyfriend. Simultaneously, she expressed concern that her emotional states would negatively affect her children. As a result, she described concealing her emotions and directing them inward.

It made me more mean [laughing] towards things. … Not mean. It make me have [more] lack of trust. I don’t say too much. [Laughing] I’m saying too much now, but I don’t talk to people that are in my life like that. I keep a lot to myself and I’m the type that I’ve balled it in, balled it in, balled it in. Then I become a nervous wreck sometimes. […] It’s a ball of pain I always got to hide, because I don’t show my emotions to my kids. […] Because I don’t want them to be sad, so I have to pretend that I’m happy, alright? And not to have kids worrying. I’d rather not have them worry.

Similarly, Natasha (ACE 4, household low food secure, child food secure), who described a childhood affected by her mother’s difficulties with addiction as well as the deaths of most of her childhood friends to community violence, explained,

I don’t like my kids to see me stressed or nothing like that. Because it’d be sometimes where I just be in a daze and my daughter could be talking to me. … And she be like,

“Mom, what’s wrong with you?” […]

Like she could be talking to me and I could be looking at her, but I’m just so focused on what’s there and I’m not, you know, [paying attention to her]. But other than that, I’ve been through a lot. I just try to make the good out of everything. I really do ’cause me, really, I could be in the nut house somewhere, like literally. Like, literally, be in the nut house.

Participants also admitted that it was difficult to keep their emotions in check in order to protect the negative emotions from transferring to their children. Kiana (ACE 9, household very low food secure, child low food secure), a mother of a toddler, described challenges protecting her son from her feelings of anger and depression while living in a shelter:

I find myself a lot of times when I’m on my way back to the shelter, I start getting depressed. I’m like, “Ugh, another day in here. […]” That’s where the anger comes in at. And I felt myself one time taking my anger out on my son—not like physically or anything, but like not letting him have as much freedom as he should have. But I felt like I was taking it out on him. Like, “No you can’t play here. Just stop. Sit down.” [But then I realized], “He’s a baby. He needs, you know, freedom. He needs to learn, touch, and grow.” So I stopped that.

Other participants described emotional shutdown as a result of what they had experienced. For instance, Tamira described how her exposure to abuse and neglect made her feel that her life did not “matter.” During the extended time when she was alone and homeless as an adolescent, she described how she managed:

Wherever I lay my head down, that’s where I would stay the night. Like, if I couldn’t go to a friend’s house I would sleep outside in the park on the bench—anywhere. It didn’t matter. I mean, it didn’t matter because it was life. I mean, I felt dead to the world anyway, so me being outside didn’t matter. It’s like I don’t have any family. So it was like if I don’t have them then I don’t have anybody. Do you know what I’m saying? So me sleeping outside didn’t really faze me.

Some participants began to translate such lack of self-care to their own children, as low self-esteem and low self-worth passed on from one generation to the next.

Keisha, who reported emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, described how her mother’s drug abuse affected her own sense of worth. These emotions then transferred to lack of concern for her infant daughter. Keisha described how when she became pregnant with her first child at the age of 15, she hoped the pregnancy would inspire her mother to seek help for her own drug problem. However, her mother continued to use drugs, and when Keisha became pregnant with her second child, her mother did not approve of her having another baby, and during emotionally abusive interactions tried to talk Keisha into giving the child up for adoption. Her mother’s attitude toward the child, coupled with ongoing emotional abuse, translated into neglect and potential abuse by Keisha toward her daughter. Here, she described how she almost allowed her daughter to be smothered because of how she was reenacting her mother’s lack of care and concern.

Deep down inside I’m hurt.

Because you’re my mother, why should you be like that? […] I’m not going to say I didn’t care about my baby, but I really didn’t want my baby ’cause my mom put that on me. […]

Sometimes I don’t like to think about the past. […] Like, my big baby used to be on my little baby—and I didn’t care—like smothering her and all that. It was all because my mother brainwashed me not to care for that baby. Right now, I love my daughter to death. Sometimes, when I look at her, I be feeling bad. But I try not to, because it wasn’t my fault.

Interviewer: Smother her? What do you mean?

Like, my [older] baby used to be laying on her and all that when we used to be sleeping. And I didn’t care. It was all because [my mother] brainwashed me to be like that.

It was only when Keisha got away from her mother, she explained, that those feelings ended. This is an example of how abuse and/or neglect can be transferred from grandmother, to mother, to young child.

Suicide Attempts

Participants sometimes described how their emotional pain was so unbearable that it contributed to thoughts or attempts of suicide. Those who attempted suicide described it as an attempt to escape. Natalia (ACE 6, household very low food secure, child food secure), a 22-year-old mother of an infant, described sexual abuse by 2 of her older brothers when she was between the ages of 9 and 12, emotional abuse from her extended family, as well as current emotional abuse and controlling behavior from her child’s father. She reported significant emotional distress that led her to attempt suicide. Natalia explained,

The second time I tried to drown myself. […] Filled the tub up. I know everybody goes through it, but some people don’t know what you went through in life. When you want to release it, you can’t release what you want to release. And when you want to escape it, you can’t really escape where you’re trying to escape to.

Thinking About Future

Though some participants attempted suicide as a way to escape current and future pain, several others described a foreshortened sense of future that prohibited them from moving forward. This included anxiety and skepticism about making future plans, feelings of disempowerment and fatalism about their life trajectories, and an inability to even consider what their futures might hold. For instance, as Natasha explained,

I think about the future. I think about where I want to be in the next five years. You know, I want to be married. I think about all of that. Sometimes I just don’t like to plan ahead because it seems like it never comes through. So that’s why I just say I take things one day at a time.

She described disbelief that she could achieve her goals and described her inability to trust the people around her to support her goals. Additionally, she described the accumulated stress of growing up in an environment in which community violence was common and many around her died young.

Yeah, I mean I’ve been through. … I’ve been through a lot. I’ve seen a lot. Where I lived at and where I grew up at, it was very, very … it was crazy. Like everybody I grew up with is not here. They’re dead. If they was [here] they was killed.

Frequent setbacks and feelings of lack of control over their environments dating back to childhood made it difficult for participants to imagine circumstances in which they could see plans for their future realized.

4. Breaking Out of Intergenerational Patterns: “I could start my new cycle …”

Sometimes this inability to move forward was referred to as being “stuck.” But several participants insisted that there were ways to break the intergenerational cycle of hunger and violence. Often it was desire to protect the child or a view of the child as a motivating force. Other times there was a focus on education and helping others as a way to break out.

In our interviews, participants reported the strategy often described by food insecure caregivers: going without food in order to provide food for their children. Participants described how this desire to protect the child came from the strong impulse to not pass on their own suffering and to keep their children close. As Claudia described,

I don’t care if I’m starving. … I have to make sure that I’m starving and he’s not, because I don’t want DHS [Department of Human Services] to take him, because I know that that’s malnutrition and I know that that’s the perfect reason for them to take him. Right about now, anything’s a perfect reason for it. That’s how I feel. A bruise on his head is a perfect reason to take him.

Child as Motivator

In addition to enduring hunger as a sacrifice for their children, almost all of the caregivers described how their children inspired them to do well in life. When the caregivers talked about their parenting, many described a desire to avoid the traumas of their own childhoods and insisted that they wanted to pass on a better life. Tamira described it this way:

I’m not going to let anybody put me down. Because, at the end of the day, I’m not doing this for myself anymore; I’m doing it for my daughter. […] So I’m going to keep my daughter, and I’m going to show her everything I didn’t have. So, that’s probably why I play a big part in me not beating my daughter. […] Because, it’s like, “I want you to feel what I didn’t feel. I want you to know what it is to love somebody. I want you to know what that feeling is.” Because I still don’t know how to love somebody, because I never had anybody love me. I’m just so used to people up-and-leaving that it doesn’t faze me. […] So I kept my daughter to show her, “I wouldn’t ever leave you. I cannot take care of you—for real, for real—how I want to, but I would never leave you […] because you’re my daughter and I love you.”

Similarly, Claudia described resisting the impulse to harm her son in the way that her parents harmed her as a child:

He’s just crying and crying, and then I just get so irritated and angry. And I call his dad and I’d just be like, “Can somebody come? I need to go for a walk, you know?” […] So I know that I’m angry and I know that I can hurt him. But I also know that I am not going to hurt him, you know, at least to that point. If I have to pull my own hairs out, I’m going to pull my own hairs out, but I’m not going to hurt my son.

Clara (ACE 7, household very low food secure, child low food secure), who reported sexual abuse and emotional neglect in childhood, severe depression, and several suicide attempts in adolescence, described creating more life in order to find love. She explained:

I had my first son when I was seventeen. It hit me so hard and so much that I felt like I wasn’t loved. I needed somebody to love me, and that’s when I went out and had my child. I was like, “I’m going to love him and he’s going to love me.” That’s what made me stronger was having my son there all the time. I needed someone to give love to and someone to love me back.

She continued to describe how she uses her own childhood experiences as an inspiration to create a safe and loving environment for her children.

I don’t ever want my kids to go through none of [the pain I went through]. It’s like I sit there and I talk to them, and they don’t know what happened to their mommy. That’s not for them to know anyways. I don’t want them to have a bad heart for nobody. I want them to be healthy and good and always positive. […] It’s just taking out of what you learned to put in them, and kind of switch things around for the better. And [you’re] not leaving things the same or taking on a legend. You know, “Mom was like this so I got to be like that.” No, I have to be better.

Clara’s way of breaking away was developing a loving relationship with her child.

Education

In addition to protecting one’s own children from hardship, several participants reported focusing on education as another way to break the cycle of poverty. Some participants described school as a protective environment in which they could escape instability at home, as well as a means of escaping economic hardship. These ideas continued into adulthood. For instance, when we asked Michaela (ACE 3, household low food secure, child food secure), who described running out of food every month as a part of her current norm, if she could see the day when she would consistently have enough to eat, she laughed and said, “Yeah, after I get out of college and start my business.” Though this was said in a dismissive way, almost as if it were an impossibility, she described college as her way of getting out of poverty.

From several participants’ perspectives, advancing one’s education was a way of interrupting the intergenerational transfer of adversity, but it was often described as very challenging without encouragement and support. Gia, who described chronic economic hardship growing up with a mother with serious mental and physical illness, described the way in which changing her family’s norms would not only affect her and her child but would also positively affect her mother.

[I want my mother to] be able to celebrate [my graduation] with me, to be able to reap the benefits of my success. Also, that’s what I want for her. Because I feel like, if I made it—my mom makes it out, [and] my son—then I could start my new cycle and my son would be used to graduating high school and graduating college and he will … that will trickle down to his family and his generation. So that’s what I’m hoping.

For Gia, breaking the pattern of disadvantage would extend back in time to her mother’s generation and forward in time, to her son and his family in generations to come.

Helping Others

In addition to improving their own futures, participants expressed a common desire to be helpful to others and to give back to their communities. Helping others was not only considered healing for the participants and their communities but also as a way of changing social norms. When asked what she would do with her education, Gia, who experienced physical and emotional abuse from her son’s father, described how she wanted to help other girls in similar situations.

They’re beaten and abused, and they just don’t have anybody to tell them that you can make it out of here, like they don’t have people to come to them. […] I know a lot of people that have been through a lot of stuff [like] molestation. Like my mom’s been through it, her mom’s been through it. Luckily, I’ve never been through it, so I was blessed. Once that happens to you, it’s like you stay at that age where that happened. It’s like you never forget about that. And that wears a lot on a person. So I would like to talk to people about stuff like that, and different stuff and just show them that there’s a way out of here. […] They just need a chance.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that most participants who reported both recent food insecurity and previous adversity identified the roots of their economic hardship in their childhood and in previous generations. Additionally, several participants explicitly explained how hunger, violence, and adversity were interrelated, even inseparable. The majority found some way to describe how exposure to adversity and violence was a familial and societal norm that they sought to break.

Almost all who experienced sexual abuse described complex emotions and experiences related to telling family, friends, and officials. This reflects findings of previous studies,62, 63 which indicate that internal barriers in the mental and developmental state of survivors, relational barriers in family and social networks, and social barriers present in dominant societal norms impede disclosure of childhood sexual abuse.

Those who reported depression and anxiety expressed worry about protecting their children not only from hunger and violence but also from their depression and sadness, corroborating previous literature. 64 ,65 Parents clearly recognized how their own childhood experiences and struggles with adversity could potentially transfer to their children, and they worked hard to avoid this type of transfer. The children, as a new generation, were considered important motivators and gave mothers a feeling of significance and purpose to break the intergenerational transfer of adversity. The most accessible and powerful ways participants identified to protect children from the transfer were through expressions of love, protection, and safety. Almost all participants described a strong desire to break the cycle of adversity, especially through expressing love, achieving a good education, and helping others, yet there were varying reports of capability and energy to do so.

As a whole, the themes identified demonstrate that despite being a part of the family patterns of intergenerational transfer in their childhoods, participants also had the potential to overcome and alter those patterns for themselves and their own children. On one hand, their reports demonstrate how adversity (such as exposure to violence, neglect abuse, and serious material deprivation) help to carry food insecurity from one generation to the next. However, the strength and insight of the participants in this study as characterized by their self-awareness, their love for their children, and their sense of potential and societal belonging show that there is much resilience on which families, social services organizations, and other professionals can draw.

By building on this resilience, we can prevent young children from experiencing toxic stress. Toxic stress is a term used to define a strong and prolonged activation of a child’s stress management systems that is particularly problematic during critical developmental periods because of the effects it has on brain architecture. 64 A similar concept utilized to describe severe stress among adults is allostatic load, which refers to the wear-and-tear on the body and brain resulting from chronic overactivity or inactivity of physiological systems that are normally involved in adaptation to environmental challenge. 66

As the women in this study describe, as children and now as mothers, they have had significant exposure to conditions that create toxic and traumatic stress as well as high levels of allostatic load. Toxic stress and allostatic load represent 2 interrelated conceptual frameworks that can help us understand why the effects of adversity in childhood could be so pervasive that those effects extend into the subsequent generations. Research now indicates that many types of childhood adversity exposures, including food insecurity, produce toxic stress with resultant changes in brain structure and function that manifest as a wide variety of behavioral, emotional, cognitive, and moral burdens throughout the life span of the affected children. Such changes affect their ability to parent their own children and may also result in epigenetic changes that are transmitted to the next generation. 67 ,68

Advances in the domains of developmental neurobiology, social neuroscience, molecular biology, and epigenetics necessitate changes in our framework for how we address the complex problems of food insecurity. 52 ,69 We can no longer address the problems of vulnerable children separately from the problems of their vulnerable caregivers; rather, we must address these problems as interactive and interdependent. This requires programming and policies that focus on 2-generation approaches, as well as approaches that connect the economic well-being of caregivers to the present and future health and well-being of their children and, by extension, to the well-being of our society. The situation for millions of children who live with multiple adversities including chronic hunger is both urgent and critical.

Despite heightened risk of poor health and well-being among families exposed to abuse and neglect, many children who experience adversity do not experience negative outcomes in adulthood, indicating the importance of resilience and protective factors in the face of trauma and adversity. Research on protective factors, resilience, and healing after a trauma has occurred offers suggestions for strengths-based approaches for intervention and support for families facing adversity in order to prevent the intergenerational transmission of adversity and disadvantage. 70 ,71

Limitations

Results are limited in their generalizability and representativeness due to the small, nonrandomized sample. Yet they corroborate other studies that suggest that exposure to violence and adversity are strongly related to food insecurity. Recruitment of participants through a study occurring in a hospital emergency department may introduce bias toward participants who have a higher exposure to adversity. Self-selection into this study, in which caregivers were encouraged through the recruitment flyer to share their experiences with “stress in childhood,” may have biased participation toward those who were interested in drawing connections between their childhood experiences and their current circumstances. Because we did not explicitly ask participants about violence, hunger, and adversity in their parents’ and grandparents’ generations, we are limited by what participants chose to disclose in the course of discussing their own experiences. Furthermore, the interviews were guided by the ACE survey and were thus limited by a focus on the household and family environment dependent on participant self-report and recall. The focus on household adversity does not fully capture the societal context that informs and constrains individual and family behaviors, including widespread structural factors such as poverty, inequity, racism, gender discrimination, and systemic violence. This qualitative study was not designed to pick up these important dynamics, though it bears repeating that experiences with low wages, mortgage foreclosure, economic hardship, and racial discrimination are associated with psychosocial distress and social isolation, which are in turn associated with parenting practices and household dysfunction. 72 – 74

Conclusion

The strong thematic relationships described in these interviews suggest that current reports of household food insecurity simultaneously capture deprivation for at least 3 generations. The depth of deprivation among households with young children reporting low and very low household food security and, on occasion, child food insecurity, is an indication not only of hardship in the previous generation but also of exposure to violence, poor mental health, and trauma-related experiences and behaviors. There is a need for more research and understanding of food insecurity across the life course, taking into account the depth of depression and the risky coping strategies related to lack of trust and care. Family adversity, moreover, does not occur only at the family or individual level but is deeply affected by federal, state, and city policies, programs, and institutions. Research on both ACEs and food insecurity should be more attentive to social and political context, such as labor market dynamics, discriminatory housing policies, increases in incarceration rates, and inequitably funded education systems.

Because food insecurity has roots in deprivation passed from earlier generations, assistance programs may need to adopt approaches that provide more consistent and stable support over a longer period of time to prevent sporadic and inconsistent alleviation of hardship. Two-generation interventions that simultaneously address the health and development of children as well as economic stability and mental health of caregivers may offer opportunities to prevent the intergenerational transmission of disadvantage. 52 ,75– 77

Additionally, current public assistance programs may be ill prepared and inadequate to address such a breadth and depth of challenges. These results indicate an urgent need to ensure that families reporting food insecurity gain access to stable, consistent public assistance and can readily find and create opportunities to change their family and community norms. These opportunities must be made available in a way that embraces families with a multigenerational framework and that comprehensively helps them to meet basic needs beyond cash and food allotments to ensure that families have safe places to live and to care for their children.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants for sharing their experiences and insight for this investigation. The authors also thank Jenny Rabinowich for her assistance in developing the research design and conducting the interviews and Bea Sanchez and Kimberly Arnold for their assistance in conducting some of the interviews and preliminary analysis. The authors would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their insights that helped us to improve this manuscript.

Funding Statement

This project was supported with a grant from the University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research through funding by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service (Contract Number AG-3198-B-10-0028). The opinions and conclusions expressed herein are solely those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the opinions or policies of the UKCPR or any agency of the U.S. Federal Government.

Funding

This project was supported with a grant from the University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research through funding by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service (Contract Number AG-3198-B-10-0028). The opinions and conclusions expressed herein are solely those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the opinions or policies of the UKCPR or any agency of the U.S. Federal Government.

References

- 1. Coleman-Jensen A, Gregory C, Singh A.. Household Food Security in the United States in 2013. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pérez-Escamilla R, Pinheiro de Toledo Vianna R. Food insecurity and the behavioral and intellectual development of children: a review of the evidence. J Appl Res Child. 2012;3(1):9 Available at: http://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/childrenatrisk/vol3/iss1/9. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rose-Jacobs R, Black MM, Casey PH, et al. Household food insecurity: associations with at-risk infant and toddler development. Pediatrics. 2008;121:65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cook JT, Frank DA, Berkowitz C, et al. Food insecurity is associated with adverse health outcomes among human infants and toddlers. J Nutr. 2004;134:1432–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eicher-Miller HA, Mason AC, Weaver CM, McCabe GP, Boushey CJ.. Food insecurity is associated with iron deficiency anemia in U.S. adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1358–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Skalicky A, Meyers AF, Adams WG, Yang Z, Cook JT, Frank DA.. Child food insecurity and iron-deficiency anemia in low-income infants and toddlers in the United States. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(2):177–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kirkpatrick SI, McIntyre L, Potestio ML.. Child hunger and long-term adverse consequences for health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:754–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA.. Family food insufficiency, but not low family income, is positively associated with dysthymia and suicide symptoms in adolescents. J Nutr. 2002;132:719–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Casey P, Goolsby S, Berkowitz C, et al. Maternal depression, changing public assistance, food security, and child health status. Pediatrics. 2004;113:298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heflin CM, Siefert K, Williams DR.. Food insufficiency and women’s mental health: findings from a 3-year panel of welfare recipients. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:1971–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leung CW, Epel ES, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Laraia BA.. Household food insecurity is positively associated with depression among low-income Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participants and income-eligible nonparticipants. J Nutr. 2015;145:622–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Seligman HK, Bindman AB, Vittinghoff E, Kanaya AM, Kushel MB.. Food insecurity is associated with diabetes mellitus: results from the National Health Examination and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2002. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1018–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB.. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010;140:304–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lu MC, Halfon N.. Racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes: a life-course perspective. Matern Child Health J. 2003;7:13–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D.. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:285–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kuh D, Hardy R.. A Life Course Approach to Women’s Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chilton M, Knowles M, Rabinowich J, Arnold KT. The relationship between childhood adversity and food insecurity: “It’s like a bird nesting in your head.” Public Health Nutr. 2015;18,14:2643–2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Whitaker RC, Phillips SM, Orzol SM.. Food insecurity and the risks of depression and anxiety in mothers and behavior problems in their preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e859–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zaslow M, Bronte-Tinkew J, Capps R, Horowitz A, Moore KA, Weinstein D.. Food security during infancy: implications for attachment and mental proficiency in toddlerhood. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13:66–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heflin CM, Corcoran ME, Siefert KA.. Work trajectories, income changes, and food insufficiency in a Michigan welfare population. Soc Serv Rev. 2007;81:3–25. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tarasuk VS. Household food insecurity with hunger is associated with women’s food intakes, health and household circumstances. J Nutr. 2001;131:2670–2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bronte-Tinkew J, Zaslow M, Capps R, Horowitz A, McNamara M.. Food insecurity works through depression, parenting, and infant feeding to influence overweight and health in toddlers. J Nutr. 2007;137:2160–2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goodman LA, Smyth KF, Borges AM, Singer R.. When crises collide: how intimate partner violence and poverty intersect to shape women’s mental health and coping? Trauma Violence Abuse. 2009;10:306–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bhattacharya J, Currie J, Poverty Haider S., food insecurity, and nutritional outcomes in children and adults. J Health Econ. 2004;23:839–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ashiabi GS, O’Neal KK.. A framework for understanding the association between food insecurity and children’s developmental outcomes. Child Dev Perspect. 2008;2:71–77. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gundersen C, Kreider B.. Bounding the effects of food insecurity on children’s health outcomes. J Health Econ. 2009;28:971–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weinreb L, Wehler C, Perloff J, et al. Hunger: Its impact on children’s health and mental health. Pediatrics. 2002;110(4):e41 Available at: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/110/4/e41.full.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kleinman RE, Murphy JM, Little M, et al. Hunger in children in the United States: potential behavioral and emotional correlates. Pediatrics. 1998;101:E3 Available at: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/101/1/e3.long. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Murphy JM, Wehler CA, Pagano ME, Little M, Kleinman RE, Jellinek MS.. Relationship between hunger and psychosocial functioning in low-income American children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(2):163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alaimo K, Olson CM, Jr Frongillo EA, Briefel RR.. Food insufficiency, family income, and health in U.S. preschool and school-age children. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:781–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chilton MM, Rabinowich JR, Woolf NH. Very low food security in the USA is linked with exposure to violence. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(1):73–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hernandez DC, Marshall A, Mineo C.. Maternal depression mediates the association between intimate partner violence and food insecurity. J Womens Health. 2014;23:29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Montgomery BE, Rompalo A, Hughes J, et al. Violence against women in selected areas of the United States Am J Public Health. 2015:e1–e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hernandez DC. The impact of cumulative family risks on various levels of food insecurity. Soc Sci Res. 2015;50:292–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shonkoff JP, Boyce WT, McEwen BS.. Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. JAMA. 2009;301:2252–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults—the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schilling EA, Aseltine RH, Gore S.. The impact of cumulative childhood adversity on young adult mental health: measures, models, and interpretations. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:1140–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu Y, Croft JB, Chapman DP, et al. Relationship between adverse childhood experiences and unemployment among adults from five U.S. states. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48:357–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA.. Adverse childhood experiences and sexual risk behaviors in women: a retrospective cohort study. Fam Plann Perspect. 2001;33(5):206–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Foster H, Hagan J, Brooks-Gunn J.. Growing up fast: stress exposure and subjective “weathering” in emerging adulthood. J Health Soc Behav. 2008;49(2):162–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bloom SL. Creating Sanctuary: Toward the Evolution of Sane Societies. New York, NY: Routledge; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bloom SL, Reichert M.. Bearing Witness: Violence and Collective Responsibility. New York, NY: Haworth Maltreatment and Trauma Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Swanberg J, Macke C, Logan TK.. Working women making it work: intimate partner violence, employment, and workplace support. J Interpers Violence. 2007;22(3):292–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Swanberg JE, Logan T, Macke C.. Intimate partner violence, employment,and the workplace: consequences and future directions. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2005;6(4):286–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Top Langhinrichsen-Rohling J. 10 greatest “hits”: important findings and future directions for intimate partner violence research. J Interpers Violence. 2005;20(1):108–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Miller J. Getting Played: African American Girls, Urban Inequality, and Gendered Violence. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Anda R, Fleisher VI, Felitti VJ, et al. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and indicators of impaired adult worker performance. Perm J. 2004;8:30–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wehler C, Weinreb LF, Huntington N, et al. Risk and protective factors for adult and child hunger among low-income housed and homeless female-headed families. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:109–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Melchior M, Caspi A, Howard LM, et al. Mental health context of food insecurity: a representative cohort of families with young children. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e564–e572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chilton M, Rabinowich J.. Toxic stress and child hunger over the life course: Three case studies. J Appl Res Child. 2012;3:Article 3. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Younginer NA, Blake CE, Draper CL, Jones SJ.. Resilience and Hope: Identifying Trajectories and Contexts of Household Food Insecurity. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2015;10:230–258. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shonkoff JP, Fisher PA.. Rethinking evidence-based practice and two-generation programs to create the future of early childhood policy. Dev Psychopathol. 2013;25(pt 2):1635–1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Frank DA, Casey PH, Black MM, et al. Cumulative hardship and wellness of low-income, young children: multisite surveillance study. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1115–e1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bickel G, Nord M, Price C, Hamilton W, Cook J.. Measuring Food Security in the United States: Guide to Measuring Household Food Security. Alexandria, VA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Analysis and Evaluation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kemper KJ, Babonis TR.. Screening for maternal depression in pediatric clinics. Am J Dis Child. 1992;146:876–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dong M, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, et al. The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28:771–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Anda RF.. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. J Affect Disord. 2004;82:217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Dong M, Giles WH, Felitti VJ, et al. Insights into causal pathways for ischemic heart disease: an adverse childhood experiences study. Circulation. 2004;110(13):1761–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH.. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. JAMA. 2001;286:3089–3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Strauss AL, Corbin JM.. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Collin-Vézina D, De La Sablonnière-Griffin M, Palmer AM, Milne L.. A preliminary mapping of individual, relational, and social factors that impede disclosure of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;43:123–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Alaggia R. An ecological analysis of child sexual abuse disclosure: considerations for child and adolescent mental health. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19:32–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Brennan PA, Le Brocque R, Hammen C.. Maternal depression, parent–child relationships, and resilient outcomes in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:1469–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hamelin AM, Beaudry M, Habicht JP.. Characterization of household food insecurity in Québec: food and feelings. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Flier JS, Underhill LH, McEwen BS.. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New Engl J Med. 1998;338(3):171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Siegel BS, et al. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e232–e246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Heijmans BT, Tobi EW, Stein AD, et al. Persistent epigenetic differences associated with prenatal exposure to famine in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17046–17049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Shonkoff JP. Mobilizing science to revitalize early childhood policy. Issues Sci Technol. 2009;26:79–85. [Google Scholar]