ABSTRACT

Chromatin structure has an important role in modulating gene expression. The incorporation of histone variants into the nucleosome leads to important changes in the chromatin structure. The histone variant H2A.Z is highly conserved between different species of fungi, animals, and plants. However, dynamic changes to H2A.Z in rice have not been reported during the day-night cycle. In this study, we generated genome wide maps of H2A.Z for day and night time in harvested seedling tissues by combining chromatin immunoprecipitation and high-throughput sequencing. The analysis results for the H2A.Z data sets detected 7099 genes with higher depositions of H2A.Z in seedling tissues harvested at night compared with seedling tissues harvested during the day, whereas 4597 genes had higher H2A.Z depositions in seedlings harvested during the day. The gene expression profiles data suggested that H2A.Z probably negatively regulated gene expression during the day-night cycle and was involved in many important biologic processes. In general, our results indicated that H2A.Z may play an important role in plant responses to the diurnal oscillation process.

KEYWORDS: H2A.Z deposition, gene expression, day-night, rice

Gene expression is generally affected by dynamic changes to the chromatin structures, which can be regulated by DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin remodeling, and histone variants. The histone variant, H2A.Z, is highly conserved among eukaryotes, such as fungi, mammals, and plants.1 Genome wide analysis has widely characterized H2A.Z deposition in S. cerevisiae,2-4 Drosophila,.5,6 mammals,7-10 Arabidopsis,1,11-13 and rice.14 H2A.Z deposition is probably involved in diverse genomic processes, such as gene transcription, meiotic recombination, chromosome segregation, DNA repair, and genome stability.15,16 Furthermore, H2A.Z has been reported to be involved in controlling circadian-regulated genes in mice. The underlying molecular mechanisms include binding of the TFs-CLOCK:BMAL1 promoting, temporally dependent expression of circadian clock-regulated genes.17 At the chromatin level, this binding induced chromatin remodeling results in the removal of the original nucleosomes and the incorporation of H2A.Z nucleosomes around the transcriptional start sites (TSSs) of the genes that are regulated during the day-night cycle.17,18 In plants, such as Arabidopsis, H2A.Z also plays a central role in the regulation of flowering time.19 In our recent study, we found that H2A.Z may play important roles in regulating gene transcription during rice development14 However, the mechanism behind the deposition of H2A.Z during the day-night cycle in rice is unknown.

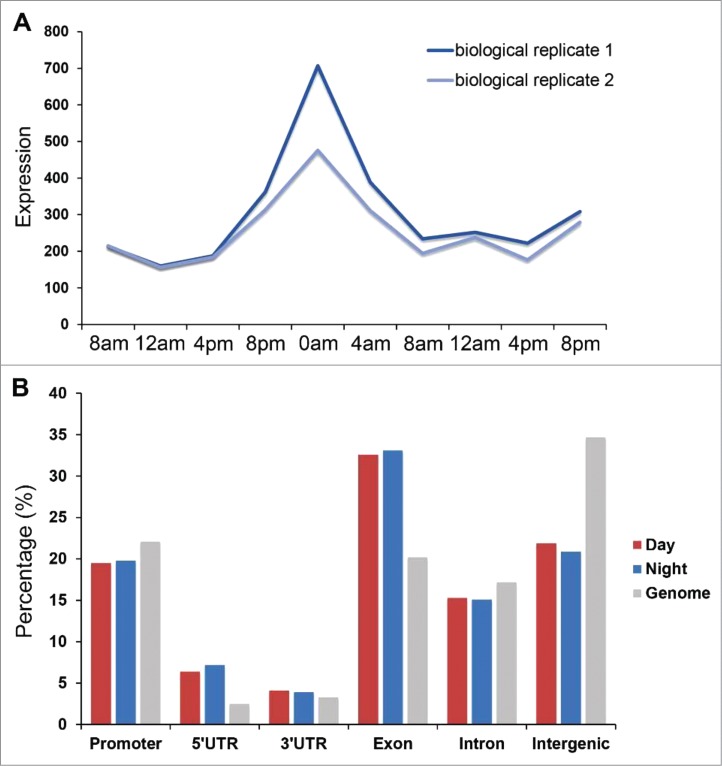

Previous studies have shown that there are 3 copies of the genes that encode H2A.Z proteins (HTA705, HTA712, and HTA713) in the rice genome. They are phylogenetically gathered into a clade with 4 subclasses of H2A.Z proteins in Arabidopsis (HTA8, HTA9, HTA11, and HTA4).1,20,21 Analysis of our previous microarray data sets revealed the diurnal expression pattern of H2A.Z encoding genes in rice seedlings. We found that gene HTA705 had a diurnal expression pattern with expression peaking around 0:00 a.m. in 2 biologic replicates (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Distribution pattern for H2A.Z in seedling tissue harvested at night. (A) The phase distribution of diurnal-pattern gene HTA705 in rice seedlings. The dark blue indicates seedling leaf sample replicate 1 and the light blue indicates seedling leaf sample replicate 2. (B) Genomic distribution of H2A.Z peaks within different regions in day and night harvested seedling tissues.

The genome wide map for H2A.Z deposition in the tissues of seedlings that were harvested during the day at 10:00 a.m. and during the night at 10:00 p.m. was obtained, and the H2A.Z data for day seedling tissue was reported in our previous publication.14 The night seedling data showed that 86.9% of total reads were mapped to the genome and 35,159 peaks were called through these mapped reads. Then we examined the distribution of H2A.Z-related nucleosomes in the promoter, the 5′ untranslated region (UTR), and the 3′UTR, exon, intron, and intergenic regions. The H2A.Z peaks were significantly enriched in the 5′UTR (7.2%) and exon regions (33.1%), which was similar to the data set for the day seedling tissue (Fig. 1B). However, the peaks in the intergenic regions were lower than the genome level. After comparing the night-time seedling data with the day-time harvested seedlings, the data showed that a higher percentage of H2A.Z was located in the 5′UTR and exon regions in night seedlings, but the percentage was lower in the intergenic region. The meta-gene profile of H2A.Z deposition around all rice genes showed that it was enriched at the 5′ end region around the TSSs (Fig. S1A). To further explore the relationship between H2A.Z deposition and gene expression, we generated the RNA-seq data for night seedling tissue and divided all the genes into 10 quantiles based on their expression levels. We found that H2A.Z deposition around genes with high expression levels tended to be higher at the 5′ end region, whereas H2A.Z-related nucleosomes from low expression genes were more likely to be deposited across the whole gene body (Fig. S1B). All these results were consistent with the findings for callus and day seedling tissues14

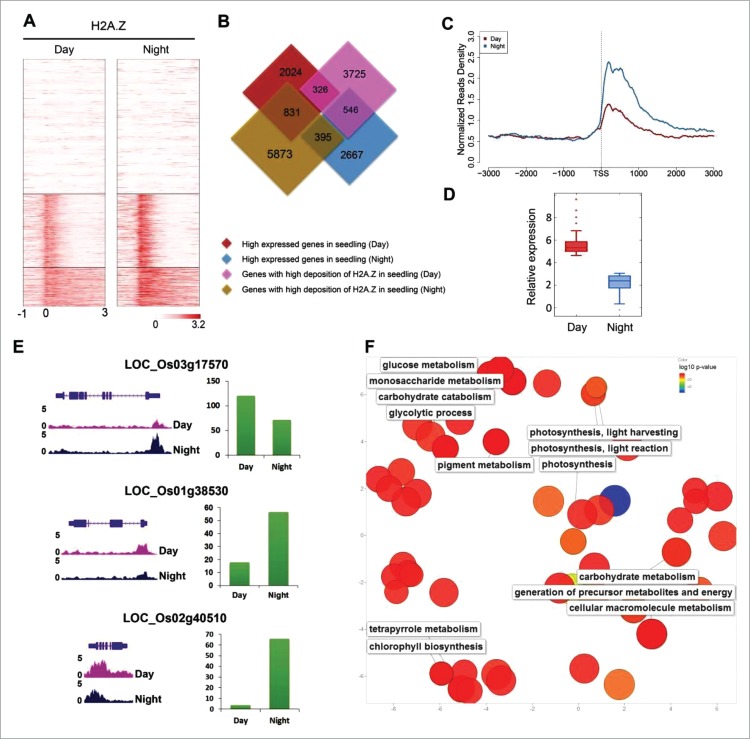

A heatmap based on the presence of H2A.Z at the TSSs was used to divide all the genes into 3 groups. These were genes without H2A.Z deposition genes, genes where H2A.Z was significantly enriched at the 5′ end, and genes where H2A.Z was enriched at the 5′ end and across the gene bodies (Fig. 2A). The relationship between the change in gene expression and the change in H2A.Z enrichment between day and night harvested seedling tissues was further investigated by identifying the genes that were differentially expressed during the day and night using RNA-seq data sets. The data showed that 326 genes with a high deposition of H2A.Z during the day were upregulated, whereas 546 genes were downregulated. A total of 395 genes with high H2A.Z depositions in the night harvested seedlings were upregulated and 831 were downregulated (Fig. 2B). These analyses suggested that H2A.Z may play a crucial role in the rice day-night cycle. We also examined H2A.Z enriched genes that had high expression levels during the day, but medium expression levels at night. We found that the deposition of H2A.Z near the TSSs of those genes was inversely proportional to their transcription levels. This was similar to the comparison between the callus and day harvested tissues, which was reported in our previous study (Figs. 2C and 2D).14 The gene loci LOC_Os03g17570 (ortholog of Arabidopsis circadian gene PRR7) was highly expressed during the day and had a similar expression pattern to Arabidopsis, whereas H2A.Z deposition was opposite to its expression levels during the day-night cycle (Fig. 2E). A similar trend was observed in the genes that had low H2A.Z depositions at night, but high depositions during the day. However, their transcription levels were the opposite, and H2A.Z was enriched at the 5′ end region (Fig. S2A and 2B). For example, this occurred in gene loci LOC_Os01g38530 and LOC_Os02g40510, which are orthologs of Arabidopsis circadian gene ELF3 and TOC1 (Fig. 2E).

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis of H2A.Z between day and night harvested seedling tissues. (A) Heatmap of H2A.Z around the TSSs of highly expressed genes in day and night harvested seedling tissues (from 1 kp upstream regions of the TSS to 3 kp downstream regions of the TSS). (B) Venn diagrams show where genes with different depositions of H2A.Z overlap genes that are differentially expressed in day and night harvested seedling tissues. (C) Deposition of H2A.Z around the genes near the TSSs. This was low in the day harvested seedlings, but high in the night harvested seedlings. The expression levels of these genes in the day harvested seedlings were high (1–3 level, expression levels were the same as in Fig. S1B), whereas they were low in night harvested seedlings (4–8 level, expression levels were the same as in Fig. S1B). (D) Relative expression of the genes that were shown in (C) in the day and night harvested seedling tissues. (E) Expression levels and ChIP-seq tracks show the gene models for LOC_Os01g38530, LOC_Os02g40510, and LOC_Os03g17570 in the UCSC Genome Browser. (F) GO analysis of genes that were highly expressed, but had low H2A.Z depositions around the TSSs in the day harvested seedling tissue.

To understand how genes with an anti-correlation between their transcription levels and H2A.Z deposition near the TSSs during the day affect the rice day-night vital activity, we applied gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis using agriGO,22 to the genes which were highly expressed in the day time, but showed low H2A.Z enrichment. Then we determined the significant GO terms (false discovery rate with a p value ≤ 0.05 as cut-off) (Fig. 2F). The results showed that those genes were mainly involved in important biologic events during the rice day-night cycle, such as photosynthesis and energy metabolism. Similarly, we found those genes that were highly expressed, but showed less H2A.Z deposition at night, were mainly involved in night-time activities, such as cellular protein modification, macromolecule modification, and protein phosphorylation processes (Fig. S2C). These results suggest that the incorporation of H2A.Z into the nucleosome might help plants adapt to alternation and maintain a balance between metabolic reactions during the day and night through their involvement in gene expression regulation.

In summary, these analyses indicate that the deposition of H2A.Z may play an important role in plant responses to the diurnal oscillation process. Our results suggest that H2A.Z may be incorporated into or removed from nucleosomes over a relatively short period of time during the day-night cycle and they may help maintain a balance between metabolic reactions during light and darkness. Whether loss of function H2A.Z can influence the homeostatic process during the rice day-night cycle needs further study.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Beijing Genomics Institute at Shenzhen (BGI Shenzhen) for help with the sequencing. We also thank Qunlian Zhang for ongoing technical support.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (grant No. 2013CBA01400) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 31371291).

References

- 1.Deal RB, Topp CN, McKinney EC, Meagher RB. Repression of flowering in Arabidopsis requires activation of FLOWERING LOCUS C expression by the histone variant H2A.Z. Plant cell 2007; 19:74-83; PMID:17220196; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1105/tpc.106.048447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raisner RM, Hartley PD, Meneghini MD, Bao MZ, Liu CL, Schreiber SL, Rando OJ, Madhani HD. Histone variant H2A.Z marks the 5′ ends of both active and inactive genes in euchromatin. Cell 2005; 123:233-48; PMID: 16239142; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang H, Roberts DN, Cairns BR. Genome-wide dynamics of Htz1, a histone H2A variant that poises repressed/basal promoters for activation through histone loss. Cell 2005; 123:219-31; PMID: 16239141; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albert I, Mavrich TN, Tomsho LP, Qi J, Zanton SJ, Schuster SC, Pugh BF. Translational and rotational settings of H2A.Z nucleosomes across the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature 2007; 446:572-6; PMID: 17392789; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature05632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mavrich TN, Jiang C, Ioshikhes IP, Li X, Venters BJ, Zanton SJ, Tomsho LP, Qi J, Glaser RL, Schuster SC et al.. Nucleosome organization in the Drosophila genome. Nature 2008; 453:358-62; PMID: 18408708; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature06929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber CM, Ramachandran S, Henikoff S. Nucleosomes are context-specific, H2A.Z-modulated barriers to RNA polymerase. Mol Cell 2014; 53:819-30; PMID: 24606920; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nekrasov M, Amrichova J, Parker BJ, Soboleva TA, Jack C, Williams R, Huttley GA, Tremethick DJ. Histone H2A.Z inheritance during the cell cycle and its impact on promoter organization and dynamics. Nature struct Molecular Bio 2012; 19:1076-83; PMID: 23085713; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb.2424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu G, Cui K, Northrup D, Liu C, Wang C, Tang Q, Ge K, Levens D, Crane-Robinson C, Zhao K. H2A.Z facilitates access of active and repressive complexes to chromatin in embryonic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Cell stem cell 2013; 12:180-92; PMID: 23260488; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.stem.2012.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Creyghton MP, Markoulaki S, Levine SS, Hanna J, Lodato MA, Sha K, Young RA, Jaenisch R, Boyer LA. H2AZ is enriched at polycomb complex target genes in ES cells and is necessary for lineage commitment. Cell 2008; 135:649-61; PMID: 18992931; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mao Z, Pan L, Wang W, Sun J, Shan S, Dong Q, Liang X, Dai L, Ding X, Chen S, et al.. Anp32e, a higher eukaryotic histone chaperone directs preferential recognition for H2A.Z. Cell Res 2014; 24:389-99; PMID: 24613878; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cr.2014.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zilberman D, Coleman-Derr D, Ballinger T, Henikoff S. Histone H2A.Z and DNA methylation are mutually antagonistic chromatin marks. Nature 2008; 456:125-9; PMID: 18815594; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature07324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coleman-Derr D, Zilberman D. Deposition of histone variant H2A.Z within gene bodies regulates responsive genes. PLoS genet 2012; 8:e1002988; PMID: 23071449; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.lagandula R, Stroud H, Holec S, Zhou K, Feng S, Zhong X, Muthurajan UM, Nie X, Kawashima T, Groth M, et al.. The histone variant H2A.W defines heterochromatin and promotes chromatin condensation in Arabidopsis. Cell 2014; 158:98-109; PMID: 24995981; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang K, Xu W, Wang C, Yi X, Zhang W, Su Z. Differential deposition of H2A.Z in combination with histone modifications within related genes in rice callus and seedling. Plant J 2017; 89:264-277; PMID: 27643852; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/tpj.13381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Talbert PB, Henikoff S. Histone variants–ancient wrap artists of the epigenome. Nat Rev Mol cell biol 2010; 11:264-75; PMID: 20197778; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm2861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deal RB, Henikoff S. Histone variants and modifications in plant gene regulation. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2011; 14:116-22; PMID: 21159547; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menet JS, Pescatore S, Rosbash M. CLOCK:BMAL1 is a pioneer-like transcription factor. Genes Dev 2014; 28:8-13; PMID: 24395244; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.228536.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohawk JA, Green CB, Takahashi JS. Central and peripheral circadian clocks in mammals. Ann Rev Neurosci 2012; 35:445-62; PMID: 22483041; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarillo JA, Pineiro M. H2A.Z mediates different aspects of chromatin function and modulates flowering responses in Arabidopsis. Plant J 2015; 83:96-109; PMID: 25943140; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/tpj.12873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yi H, Sardesai N, Fujinuma T, Chan CW, Veena , Gelvin SB. Constitutive expression exposes functional redundancy between the Arabidopsis histone H2A gene HTA1 and other H2A gene family members. Plant Cell 2006; 18:1575-89; PMID: 16751347; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1105/tpc.105.039719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu Y, Lai Y. Identification and expression analysis of rice histone genes. Plant Physiol Biochem: PPB / Societe francaise de physiologie vegetale 2015; 86:55-65; PMID: 25461700; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du Z, Zhou X, Ling Y, Zhang Z, Su Z. agriGO: a GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community. Nuclc Acids Res 2010; 38:W64-70; PMID: 20435677; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkq310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.