Abstract

Campylobacter jejuni frequently infects humans causing many gastrointestinal symptoms, fever, fatigue and several long-term debilitating diseases. Current treatment for campylobacteriosis includes rehydration and in some cases, antibiotic therapy. Probiotics are used to treat several gastrointestinal diseases. Butyrate is a short-chain fatty acid known to promote intestinal health. Interaction of butyrate with its respective receptor (HCAR2) and transporter (SLC5A8), both expressed in the intestine, is associated with water and electrolyte absorption as well as providing defense against colon cancer and inflammation. Alterations in gut microbiota influence the presence of HCAR2 and SLC5A8 in the intestine. We hypothesized that adherence and/or invasion of C. jejuni and alterations in HCAR2 and SLC5A8 expression would be minimized with butyrate or Lactobacillus GG (LGG) pretreatment of Caco-2 cells. We found that both C. jejuni adhesion but not invasion was reduced with butyrate pretreatment. While LGG pretreatment did not prevent C. jejuni adhesion, it did result in reduced invasion which was associated with altered cell supernate pH. Both butyrate and LGG protected HCAR2 and SLC5A8 protein expression following C. jejuni infection. These results suggest that the first stages of C. jejuni infection of Caco-2 cells may be minimized by LGG and butyrate pretreatment.

Keywords: butyrate, Lactobacillus GG, Campylobacter jejuni, Caco-2

This study shows that butyrate and Lactobacillus GG protected against losses of a butyrate receptor and transporter in Caco-2 cells during Campylobacter jejuni exposure.

BACKGROUND

Campylobacter jejuni, a gram-negative bacterium, is zoonotic, pathogenic in humans but a common commensal in birds, swine and cattle. Due to its frequency as a zoonotic organism as well as its low infectious doses of about 500 organisms (Black et al. 1988), C. jejuni is one of the major pathogens which causes diarrhea worldwide (WHO 2016). Clinically, campylobacteriosis has a broad spectrum of symptoms ranging from asymptomatic carriage to systemic illness and death (WHO 2016). Campylobacteriosis symptoms are predominantly gastrointestinal related (e.g. diarrhea, abdominal cramping and pain, nausea and vomiting) and also include fever and fatigue (WHO 2016). The infectious symptoms usually persist for 3 to 6 days but can last up to 10 days. Campylobacteriosis is associated with several chronic diseases including irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory arthritis and Guillain-Barre syndrome (WHO 2016).

While foodborne illnesses are largely preventable, they are a common public health problem affecting one in six Americans (CDC 2016); notably, campylobacteriosis has increased globally over the past 10 years (Kaakoush et al.2015). The most common agents of disease transmission are contaminated raw poultry meat and milk, contaminated water and feces from household pets. The ability to infect a large number of people with a low dose of campylobacter via water or milk contamination has made C. jejuni a possible agent of bioterrorism; in fact, the NIH classifies C. jejuni a Category B Bioterrorism Agent (NIAID 2016).

Generally, the treatment for campylobacteriosis is to optimize hydration and electrolyte homeostasis. However, antibiotics are required for severe infections characterized by bloody diarrhea, high fevers, prolonged illness and immunocompromised individuals (WHO 2016). Due to an increase in fluoroquinolone antibiotic resistance, erythromycin and tetracycline are the recommended antibiotics for these specific patients (WHO 2016). The high rate of infection combined with the potential of fatal sequelae and antibiotic resistance have increased the importance of finding new and innovative treatments.

The gut microbiota is comprised of predominantly four phyla (Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria) and contains at least 1000 bacterial species of mostly anaerobic bacteria. These commensal bacteria are essential for immune stimulation, protection against pathogenic microorganisms as well as aid in metabolism (D’Argenio 2015). Probiotics are ‘a live microbial feed that upon ingestion in certain numbers, beneficially affects the host by improving its microbial balance and exerting health benefits beyond inherent general nutrition’ (FAO and WHO 2001). Probiotics have been used to treat several gastrointestinal diseases that have associated gut dysbiosis, including infectious diarrhea, ulcerative colitis and pouchitis (Shanahan 2010; Grimm and Riedel 2016). While it is not specifically known how probiotics bestow protective or therapeutic benefits, several strain-specific mechanisms have been proposed. These include enhanced serologic antibody responses, heightened phagocytic activity against invading bacteria, bacteriocin secretion and antagonism to pathogenic microorganism adhesion by adhering to intestinal mucosal cells (Alvarez-Olmos and Oberhelman 2001; Servin and Coconnier 2003). While certain Lactobacillus strains are able to adhere to intestinal epithelial cells, colonization is likely transient (Tuomola and Salminen 1998; Servin and Coconnier 2003).

Gut microbiota ferment undigested dietary polysaccharides into short-chain fatty acids, acetate, propionate and butyrate, which are important for gut health (Cook and Sellin 1998). In addition to serving as a main fuel source for the colonic epithelial cells, butyrate enhances electrolyte and water absorption (Thangaraju et al., 2008) and influences intestinal inflammation and immune function (Borthakur et al.2012; Singh et al.2014). Depleted butyrate levels in the colonic lumen are associated with increased incidence of colorectal cancer and inflammatory bowel disease (Cook and Sellin 1998).

Butyrate is a ligand for several transporters and G-protein coupled receptors expressed in the apical and/or basolateral membrane of intestinal epithelial cells. SLC5A8 is a Na+-coupled transporter for monocarboxylates, including butyrate (Thangaraju et al.2008). It represents the only Na+-coupled solute transporter expressed abundantly in the large intestine, thus making it a likely candidate to mediate the entry of butyrate, as well as sodium and water, into enterocytes across the apical membrane. A Gαi-protein-coupled niacin receptor (Niacr1, HCAR2 or GPR109A) expressed in intestinal epithelial cells also recognizes butyrate (Thangaraju et al.2009; Cresci, Nagy and Ganapathy 2013). Activation of the receptor with its ligands decreases intracellular cAMP levels (Wise et al.2003). Since cAMP has profound effects on water and electrolyte absorption in the intestinal tract, decreased presence of this receptor caused by pathogenic bacteria could potentially contribute to the excessive water and electrolyte losses that occur following infection (Field 2003).

This study investigated the hypothesis that pretreatment of Caco-2 cells with a probiotic (Lactobacillus GG) and/or butyrate could diminish C. jejuni invasion and maintain expression of a butyrate transporter and receptor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Sodium butyrate came from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Nucleotide sequences available in GeneBank were used for design of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers. All primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Primary antibodies came from anti-HCAR2 (Lifespan Biosciences, Seattle, WA); anti-SLC5A8 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA); anti-Campylobacter jejuni (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Secondary antibodies, Alexa Fluor 568 came from ThermoFisher Scientific (Grand Island, NY).

Cell culture and reagents

Caco-2 cells, day 14–16 post-seeding and characteristic of mature, differentiated intestinal epithelial cells, were used for in vitro experiments. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagles medium containing high glucose (4.5 g/L), L-glutamine (4.5 g/L), sodium pyruvate (110 mg/L), fetal bovine serum (10%), non-essential amino acids (1%) and streptomycin/penicillin (1%) at 37°C with 5% carbon dioxide and 95% air. Following seeding Caco-2 cells at density of 1×105 cells/well in 24 well plates with or without glass coverslips, culture medium was replaced every 2–3 days. For these experiments, cells within 10 passage numbers were used. Cell culture reagents came from Gibco (ThermoFisher).

Bacterial strains and routine culture conditions

Campylobacter jejuni strain 81–176 (Black et al.1988) was maintained on blood agar plates (Remel; Lenexa, KS) at 37°C in sealed culture boxes (Mitsubishi Gas Chemical [MGC], New York, NY) in a microaerobic atmosphere generated by Pack-Micro Aero (MGC). Liquid cultures of C. jejuni were grown in Brucella or Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth and cultured in microaerobic environments according to Pajaniappan et al.(2008). Lactobacillus GG (LGG) (ATCC 53103) was grown and prepared according to Bianchi et al. (2004). Briefly, mid-log phase LGG was added to a semiconfluent monolayer of approximately 2 × 105/well epithelial Caco-2 cells per well, centrifuged onto the monolayer at 200 × g for 5 min and incubated for 2 h at 37°C in tissue culture conditions to allow adherence/invasion to occur.

Adherence and invasion assay

A gentamycin protection assay according to Pajaniappan et al.(2008) was used to assess the ability of C. jejuni strain 81–176 to adhere to and invade Caco-2 cells. Cells were pretreated with ± LGG (5 × 107 CFU) or ± sodium butyrate (5 mM) for 1 or 48 h prior to adhesion/invasion assay, respectively. For the LGG treatments, the pH of the cell culture media was measured at each time point (baseline, adhesion and invasion).

For C. jejuni adherence, the monolayer was washed four times with Hank's balanced salt solution with strong agitation for 2 min. The monolayer was lysed with 0.01% of Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature on an orbital shaker, and total bacteria was enumerated by the plate count method (see below). For C jejuni invasion, the monolayer was washed twice with Hanks’ balanced salt solution, and fresh pre-warmed medium containing gentamyacin at 100 ug/ml was added to kill the extracellular bacteria. After a second 2-h incubation, the monolayer was washed with Hanks’ balanced salt solution, and lysed with 0.01% Triton X-100 as described above. Serial dilution was then performed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then plated on MH agar in anaerobic conditions (Pack-MicroAnaero, Mitsubishi Gas Chemical Company) in order to enumerate the released intracellular bacteria. Invasion ability is described as the percentage of input bacteria surviving the gentamyacin treatment, and adherent bacteria is described as the total number of bacteria without the gentamyacin treatment.

Immunocytochemistry

Following adhesion and invasion assays, Caco-2 cells seeded on glass coverslips were rinsed with 1 × PBS, fixed with ice-cold methanol, blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin, incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C, washed and then incubated with secondary antibody, washed and mounted with Vectishield with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Negative control sections substituted PBS for the primary antibody. A Zeiss Axioplan-2 microscope was used to detect the immunopositive signals.

Reverse transcriptase PCR

RNA was prepared as described by Thangaraju et al. (2009) from Caco-2 cell monolayers following adhesion and invasion assays and was used for RT-PCR. The PCR primers were designed based on the nucleotide sequences available in GenBank for primers: HCAR2 (NM_177551) (FWD: 5΄-CGAGGTGGCTGAGGCTGGAATTGGGT-3΄); (REV: 5΄- 5΄-ATTTGCAGGGCCATTCTGGAT-3΄); SLC5A8 (NM_145423) (FWD: 5΄- GGGTGGTCTGCACATTCTACT-3΄); GCCCACAAGGTTGACATAGAG-3΄); and GAPDH (NM_008084) (FWD: 5΄- CTCTGGAAAGCTGTGGCGTGAT-3); REV: 5΄-CATGCCAGTGAGCTTCCCGTTCAG-3). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) messenger RNA (mRNA) was used as the internal control and PCR products were semiquantified as described by Cresci, Nagy and Ganapathy (2013).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was assessed by Student's t-test using Graph Pad Prism software, version 5.0. Data were log-transformed as necessary to obtain a normal distribution. Results are representative of three independent experiments and presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Influence of butyrate and LGG pretreatment on Campylobacter jejuni pathogenesis

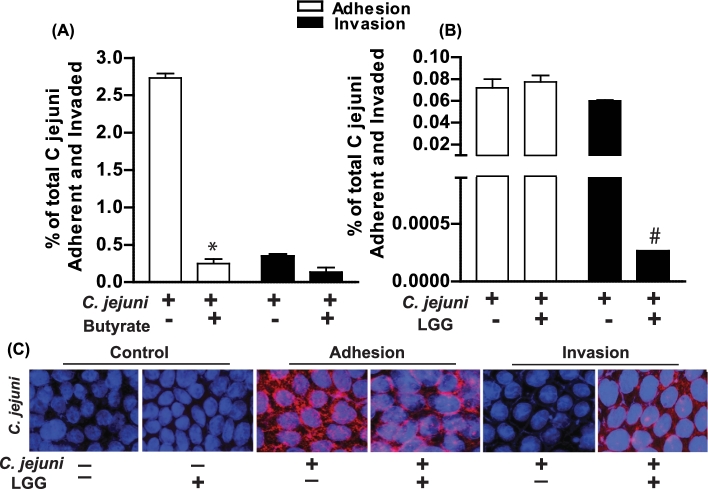

Pretreatment of Caco-2 monolayers with butyrate followed by C. jejuni infection resulted in significantly decreased adhesion but not invasion of C. jejuni (Fig. 1A). While pretreatment of the Caco-2 monolayer with LGG did not influence C. jejuni adhesion, LGG did decrease C. jejuni invasion (Fig. 1B). This was also evidenced by the intensity of C. jejuni protein staining via immunocytochemistry in Caco-2 monolayers following adhesion and invasion assays (Fig. 1C). During adhesion, C. jejuni immunoreactive staining was positive on the Caco-2 cell surface; however, this staining intensity was lost during C. jejuni invasion. The localization of C. jejuni on the Caco-2 cell surface was maintained with LGG pretreatment which coincided with reduced C. jejuni invasion.

Figure 1.

Butyrate and LGG effects on C. jejuni adherence and invasion of Caco-2 monolayers. Campylobacter jejuni strain 81–176 was grown to mid-log phase in biphasic culture. Caco-2 monolayers were pretreated with ± sodium butyrate (5 mM) for 48 h (A) or ± LGG (5×107 CFU) for 1 h (B) prior to being inoculated with C. jejuni at an MOI of ∼40. After 3 h, the cells were washed and bacteria adhered were enumerated. Gentamicin was added to another plate of cells and incubation was continued for an additional 2 h after which the cells were washed and bacteria invaded were enumerated. After adhesion and invasion assays with LGG pretreatments, cell monolayers were analyzed for presence of C. jejuni via immunocytochemistry (C). Images are representative and values are means calculated from at least three different experiments, with standard errors represented by vertical bars. Statistical significance compared to control/untreated cells is represented by * P < 0.001; #P = 0.02. All images were acquired using a ×40 objective.

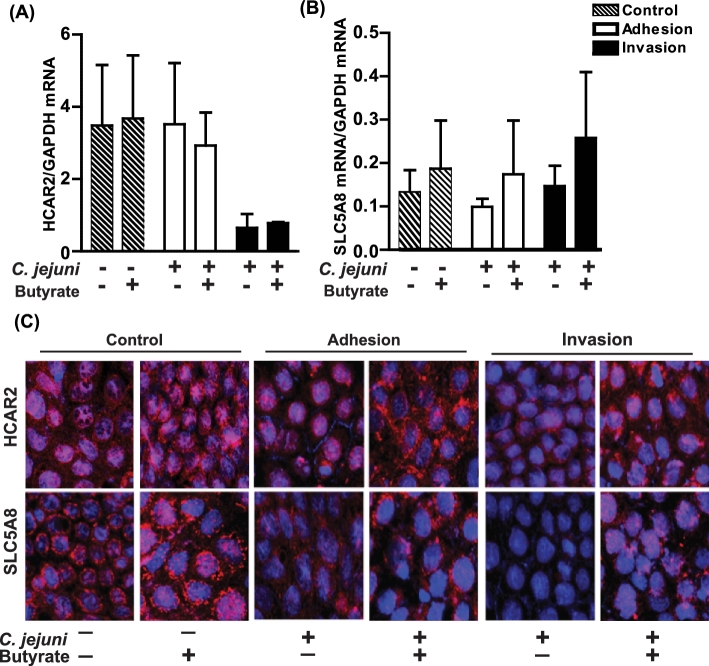

Effects of butyrate on HCAR2 and SLC5A8 expression during Campylobacter jejuni adhesion and invasion

Steady-state mRNA levels of HCAR2 or SLC5A8 during adhesion or invasion were not altered by pretreatment of Caco-2 monolayers with butyrate prior to infection with C. jejuni (Fig. 2A and B). However, immunoreactive HCAR2 and SLC5A8 was visibly reduced with C. jejuni adhesion and invasion (Fig. 2C). These changes were mitigated with butyrate pretreatment.

Figure 2.

Effects of butyrate pretreatment on expression of HCAR2 and SLC5A8. Fifteen day-old differentiated Caco-2 monolayers were pretreated with ± sodium butyrate (5 mM) for 48 h prior to inoculation with C. jejuni as described in Fig. 1. After adhesion and invasion assays (A, B), cells were harvested for RNA preparation and subsequent mRNA expression of HCAR2 and SLC5A8 via qRT-PCR or (C) cells were analyzed for protein expression of HCAR2, SLC5A8 via immunocytochemistry. Images are representative and values are means calculated from at least three different experiments, with standard errors represented by vertical bars. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) is represented by an asterisk. All images were acquired using a ×40 objective.

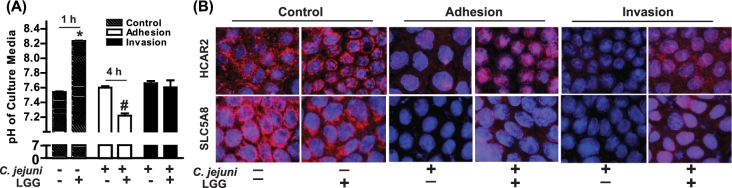

Effects of LGG on cell culture media pH and HCAR2 and SLC5A8 expression during Campylobacter jejuni adhesion and invasion

One proposed mechanism of action of probiotics against pathogens is their adherence to the cell surface thus taking up an adherence site for pathogenic bacteria. LGG is capable of adhering to Caco-2 cell monolayers (Tuomola and Salminen 1998). Acids (e.g. lactic acid, phosphoric acid) are metabolic by-products of probiotics, and creation of a more acidic environment is another proposed mechanism in which probiotics mitigate pathogenic bacteria survival. We monitored Caco-2 cell culture media pH after 1 h of Caco-2 monolayer with or without exposure to LGG and at C. jejuni adhesion and invasion time points. Cell culture media pH was elevated with 1 h of LGG exposure compared to untreated cells (Fig. 3A). However, the pH of cells exposed to LGG at C. jejuni adhesion was lower than cells not treated with LGG. There was no difference in cell culture pH between groups with C. jejuni invasion. In the absence of LGG pretreatment, immunoreactive HCAR2 and SLC5A8 on Caco-2 cells was visibly reduced with C. jejuni adhesion and invasion (Fig. 3B). LGG pretreatment reduced these changes.

Figure 3.

Effects of LGG on culture media pH and protein expression of HCAR2 and SLC5A8. Fifteen day-old differentiated Caco-2 monolayers were pretreated with ± LGG (5 × 107 CFU) for 1 h prior to inoculation with C. jejuni as described in Fig. 1. After adhesion and invasion assays (A), cell culture media pH was measured and (B) cells were analyzed for protein expression of HCAR2, SLC5A8 and C. jejuni via immunocytochemistry. Images are representative and values are means calculated from at least three different experiments, with standard errors represented by vertical bars. Statistical significance compared to control/untreated cells is represented by * P = 0.006; #P = 0.008. All images were acquired using a ×40 objective. 1 h, 4 h = LGG exposure time to Caco-2 monolayer.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates the ability of butyrate and LGG in protecting differentiated Caco-2 cell monolayers against early stages of Campylobacter jejuni pathogenesis. Protection against C. jejuni adhesion by butyrate and invasion by LGG was associated with the presence of HCAR2 and SLC5A8, a butyrate receptor and transporter, respectively.

Trillions of predominantly anaerobic bacteria reside within the intestine, with ∼90% of species coming from the Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes phyla. The Firmicutes phyla is composed of Clostridia, which contains butyrate-producing bacteria, and Bacilli, which contains Lactobacillus sp. Due to demonstrated safety and health benefits, Lactobacillus species are commonly considered probiotics and included into food products or supplements. Mechanisms of action of probiotics are strain specific, and certain lactobacilli strains, including LGG, have been shown to exhibit adhesion and competitive inhibition against human intestinal pathogens (Gueimonde et al.2006). Lactobacillus strain GG is able to colonize the gastrointestinal tract (Goldin et al.1992), adhere to Caco-2 cells (Tuomola and Salminen 1998) and alter culture pH due to release of lactic acid (Lehto and Salminen 1997). In our model, we found that these LGG characteristics were beneficial in decreasing C. jejuni invasion, but not adhesion. Adhesion and invasion are two important virulence factors of C. jejuni that contribute to pathogenicity in humans (Bhavsar and Kapadnis 2007). While adhesion is a necessary part of C. jejuni virulence, to invade host cell barriers the bacteria must also penetrate the cell and be taken up by a cytoplasmic vacuole though the use of flagellar motility. A decreased pH can impair bacterial survival as well as impair the motility of bacteria by influencing the motor function of bacterial flagellar (Minamino et al.2003). Measurement of pH is frequently used to evaluate microbial growth, vitality and death (Mufandaedza et al2006). Lactic acid bacteria may produce lactic acid at different rates (Mufandaedza et al.2006). Interesting in this study cell culture media pH was slightly elevated after 1 h of LGG pretreatment of Caco-2 monolayers, but after 4 h of LGG exposure the pH dropped significantly. While this was not associated with decreased C. jejuni adherence, invasion was decreased. One possible mechanism of how LGG pretreatment in this study decreased C. jejuni invasion may be by altering the cell culture supernatant pH and thus impairing C. jejuni flagellar function and thus its motility into the cell.

Diffuse, bloody, edematous and exudative enteritis follows C. jejuni infection. The inflammatory infiltrate consists of immune cells, and crypt abscesses develop in the epithelial glands, as well as occurrence of ulceration of the mucosal epithelium (Bhavsar and Kapadnis 2007). Butyrate has many beneficial effects in maintaining intestinal health, including modulating immune and inflammatory function and intestinal integrity (Cook and Sellin 1998). A previous study showed that butyrate not only protects against C. jejuni invasion and translocation into Caco-2 cells, but also preserves the integrity of the Caco-2 monolayer (Van Deun et al.2008). Undifferentiated cells were more vulnerable to C. jejuni invasion than differentiated cells. Butyrate aids in epithelial cell differentiation which could be a potential mode of its protection in this study (Siavoshian et al. 2000).

We found that butyrate's defense against C. jejuni was associated with the localization of a butyrate transporter and receptor. We previously reported the beneficial effects of butyrate and/or gut microbiota on the expression of SLC5A8 and HCAR2 (Thangaraju et al.2008, 2009; Cresci et al.2010; Cresci, Nagy and Ganapathy 2013). HCAR2 is a Gαi-protein-coupled receptor known to mediate inflammatory responses by decreasing intracellular cAMP levels and inflammation though decreased translocation of NF-kB and production of proinflammatory cytokines (Wise et al.2003; Borthakur et al.2012; Fu et al. 2014). Preservation of these butyrate-linked mediators during C. jejuni infection could potentially lessen the diarrheal symptoms of water and electrolyte losses caused by campylobacteriosis.

In conclusion, these findings illustrate protective effects of butyrate and LGG during C. jejuni infection. Mechanisms of action of probiotics are strain specific and may thus vary greatly. Understanding the mode in which a probiotic strain exhibits its beneficial effects is key for proper application. Since intestinal butyrate levels are dependent upon dietary fiber and optimal gut microbiota composition, dietary formulation to enhance butyrate levels and maintain gut microbiota balance may influence the prevalence, incidence and outcome of campylobacteriosis.

FUNDING

This work was supported by Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians in Nutrition Support Research Award (GAMC); National Institutes of Health grant [K99AA023266] to (GAMC) and R01AI055715, R56AI084160 and R01AI103267 (to SAT).

Conflict of interest. None declared.

REFERENCES

- Alvarez-Olmos MI, Oberhelman RA. Probiotic agents and infectious diseases: a modern perspective on traditional therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2001;32:1567–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhavsar SP, Kapadnis BP. Virulence factors of Campylobacter. Internet J Microbiol 2007;3:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi MA, Del Rio D, Pellegrini N et al. A fluorescence-based method for the detection of adhesive properties of lactic acid bacteria to Caco-2 cells. Lett Appl Microbiol 2004;39:301–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black RE, Levine MM, Clements ML et al. Experimental Campylobacter jejuni infection in humans. J Infect Dis 1988;157:472–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borthakur A, Priyamyada S, Kumar A et al. A novel nutrient sensing mechanism underlies substrate-induced regulation of monocarboxylate transporter-1. Am J Physiol Gastr L 2012;303:G1126–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control. Foodborne Germs and Illnesses. http://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/foodborne-germs.html (date last accessed, 4 November 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Cook S, Sellin J. Review article: short chain fatty acids in health and disease. Aliment Pharmocol Ther 1998;12:499–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresci G, Nagy LE, Ganapathy V. Lactobacillus GG and tributyrin supplementation reduce antibiotic-induced intestinal injury. JPEN-Parenter Enter 2013;37:763–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresci GA, Thangaraju M, Mellinger JD et al. Colonic gene expression in conventional and germ-free mice with a focus on the butyrate receptor GPR109A and the butyrate transporter SLC5A8. J Gastrointest Surg 2010;14:449–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Argenio V, Salvatore F. The role of the gut microbiome in the healthy adult status. Clin Chim Acta 2015;451:97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M. Intestinal ion transport and the pathophysiology of diarrhea. J Clin Invest 2003;111:931–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food. London, Ontario, Canada: Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organization, 2001. http://who.int/foodsafety/fs_management/en/probiotic_guidelines.pdf (date last accessed, 27 September 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Fu SP, Li SN, Wang JF et al. BHBA suppresses LPS-induced inflammation in BV-2 cells by inhibiting NF-kB activation. Mediat Inflamm 2014;2014:983–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin BR, Gorback SL, Saxelin M et al. Survival of Lactobacillus species (strain GG) in human gastrointestinal tract. Dig Dis Sci 1992;37:121–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm V, Riedel CU. Manipulation of the microbiota using probiotics. Adv Exp Med Biol 2016;902:109–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueimonde M, Jalonen L, He F et al. Adhesion and competitive inhibition and displacement of human enteropathogens by selected lactobacilli. Food Res Int 2006;39:467–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kaakoush NO, Castaño-Rodríguez N, Mitchell HM et al. Global epidemiology of Campylobacter. Infect Clin Microbiol Rev 2015;28:687–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehto EM, Salminen SJ. Inhibition of Salmonella typhimurium adhesion to Caco-2 cell cultures by Lactobacillus strain GG spent culture supernate: only a pH effect? FEMS Immunol Med Micr 1997;18:125–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minamino T, Imae Y, Oosawa F et al. Effect of intracellular pH on rotational speed of bacterial flagellar motors. J Bacteriol 2003;185:1190–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mufandaedza J, Viljoen BC, Fersu SB et al. Antimicrobial properties of lactic acid bacteria and yeast-LAB cultures isolated form traditional fermented milk against pathogenic Escherichia coli and Salmonella enteritidis strains. Intern J Food Microbiol 2006;108:147–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIAID Emerging Infectious Diseases/Pathogens. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases https://www.niaid.nih.gov/research/emerging-infectious-diseases-pathogens (date last accessed, 17 October 2016).

- Pajaniappan M, Hall JE, Cawthaw SA et al. A temperature-regulated Campylobacter jejuni gluconate dehydrogenase is involved in respiration-dependent energy conservation and chicken colonization. Mol Microbiol 2008;68:474–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servin AL, Coconnier MH. Adhesion of probiotic strains to the intestinal mucosa and interaction with pathogens. Best Pract Res Cl Ga 2003;17:741–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan F. Probiotics in perspective. Gastroenterology 2010;139:1808–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N, Gurav A, Sivaprakasam S et al. Activation of Gpr109a, receptor for niacin and the commensal metabolite butyrate, suppresses colonic inflammation and carcinogenesis. Immunity 2014;40:128–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siavoshian S, Segain JP, Kornprobst M et al. Butyrate and trichostatin A effects on the proliferation/differentiation of human intestinal epithelial cells: induction of cyclin D3 and p21 expression. Gut 2000;46:507–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thangaraju M, Cresci G, Anath S et al. GPR109A is a G-protein-coupled receptor for the bacterial fermentation product butyrate and functions as a tumor suppressor in colon. Cancer Res 2009;69:2826–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thangaraju M, Cresci G, Itagaki S et al. Sodium-coupled transport of the short chain fatty acid butyrate by SLC5A8 and its relevance to colon cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 2008;2:1773–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuomola EM, Salminen SJ. Adhesion of some probiotic and dairy Lactobacillus strains to Caco-2 cell cultures. Int J Food Microbiol 1998;41:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Deun K, Pasmans F, Van Immerseel F et al. Butyrate protects Caco-2 cells from Campylobacter jejuni invasion and translocation. Br J Nutr 2008;100:480–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise A, Foord SM, Fraser JN et al. Molecular identification of high and low affinity receptors for nicotinic acid. J Biol Chem 2003;278:9869–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Campylobacter Fact Sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs255/en/ (date last accessed, 17 October 2016). [Google Scholar]