Abstract

Phosphatidylserine (PS) synthase (Cho1p) and the PS decarboxylase enzymes (Psd1p and Psd2p), which synthesize PS and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), respectively, are crucial for Candida albicans virulence. Mutations that disrupt these enzymes compromise virulence. These enzymes are part of the cytidine diphosphate-diacylglycerol pathway (i.e. de novo pathway) for phospholipid synthesis. Understanding how losses of PS and/or PE synthesis pathways affect the phospholipidome of Candida is important for fully understanding how these enzymes impact virulence. The cho1Δ/Δ and psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ mutations cause similar changes in levels of phosphatidic acid, phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylinositol and PS. However, only slight changes were seen in PE and phosphatidylcholine (PC). This finding suggests that the alternative mechanism for making PE and PC, the Kennedy pathway, can compensate for loss of the de novo synthesis pathway. Candida albicans Cho1p, the lipid biosynthetic enzyme with the most potential as a drug target, has been biochemically characterized, and analysis of its substrate specificity and kinetics reveal that these are similar to those previously published for Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cho1p.

Keywords: lipidomics: phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylcholine, Candida albicans

Phosphatidylserine synthase has impacts on the whole phospholipidome of the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans.

INTRODUCTION

Fungi of the genus Candida are opportunistic pathogens known to cause vulvovaginal, oral and invasive bloodstream infections in humans. Invasive infections are the most serious, with a mortality rate around 30% (Wisplinghoff et al. 2004; Morrell, Fraser and Kollef 2005). Currently, there are three main antifungal classes used to treat bloodstream infections of Candida albicans, the species that causes the majority of these infections (Pfaller et al. 2012). These therapies include azoles (e.g. fluconazole), echinocandins (e.g. caspofungin) and polyenes (e.g. amphotericin B). Unfortunately, these drugs have limited effectiveness due to documented cases of azole and echinocandin resistance (Mishra et al. 2007), the nephrotoxicity of amphotericin B (Holeman and Einstein 1963; Ghannoum and Rice 1999) and the requirement for intravenous administration of both amphotericin B and caspofungin. Furthermore, the recent rise in patients that are immunocompromised puts more people at risk every year (Low and Rotstein 2011), while also dramatically increasing healthcare costs (Mishra et al. 2007). As a result, it is of utmost importance to find novel antifungals to treat C. albicans potently and effectively.

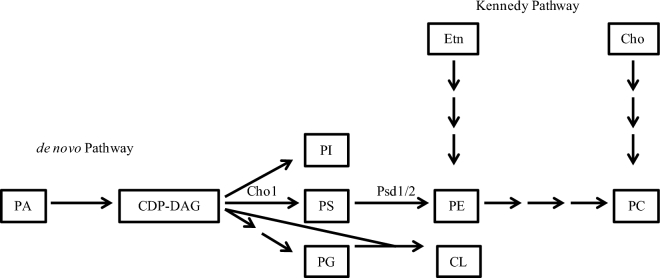

Phospholipids are crucial components of biological membranes in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. The phospholipidome of C. albicans is made up mostly of phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylglycerol (PG) and cardiolipin (CL) (Singh, Yadav and Prasad 2012). Candida albicans has a de novo method for producing phospholipids, which involves the conversion of cytidyldiphosphate-diacylglycerol (CDP-DAG) into PI, PG and PS (Fig. 1). Although PI, PG and PS can be end products, PG and PS can be further modified to form CL and PE, respectively, and PE can subsequently be methylated to produce PC. Candida albicans also utilizes exogenously provided ethanolamine and choline to produce PE and PC, respectively, via the Kennedy pathway (Gibellini and Smith 2010; Chen et al. 2010b; Henry, Kohlwein and Carman 2012).

Figure 1.

Phospholipid Biosynthesis Pathways in C. albicans. Canidida albicans phospholipid biosynthesis occurs via both an endogenous pathway, the de novo pathway and an exogenous pathway, the Kennedy pathway. The precursors for producing the most common phospholipids are PA and CDP-DAG. CDP-DAG is then converted into PI, PS or PG. The endogenously produced PS can then be decarboxylated via Psd1 or Psd2 (Psd1/2) into PE and then further methylated into PC. In the Kennedy pathway, exogenous ethanolamine (Etn) and/or choline (Cho) are brought into the cell and converted into PE and PC. PG and CDP-DAG can be combined to generate CL. Abbreviations: PA, phosphatidic acid; CDP-DAG, cytidine diphosphate-diacylglycerol; PI, phosphatidylinositol; PS, phosphatidylserine; PG, phosphatidylglycerol; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; CL, cardiolipin; PC, phosphatidylcholine.

Previous studies have identified the PS synthase (Cho1p) as a potential drug target in C. albicans (Braun et al. 2005; Chen et al. 2010b). Studies have been done on the enzymology and lipid profiles associated with PS synthase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Bae-Lee and Carman 1984), but little characterization of the orthologous enzyme or its effects on lipid profiles in C. albicans has been performed. Here we report the phospholipidome of the C. albicans cho1Δ/Δ and psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ strains, as well as the enzyme kinetics of C. albicans Cho1p, finding both the Km and apparent Vmax to be in close agreement with those values reported for S. cerevisiae Cho1p (Bae-Lee and Carman 1984). The studies described in this report set the stage for further characterization of these enzymes as drug targets.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains used

The SC5314 (wild-type) strain of Candida albicans and mutants used in this study have been previously described by Chen et al. (2010b). These include cho1Δ/Δ (YLC337), cho1Δ/Δ::CHO1 (YLC344), psd1Δ/Δ (YLC280), psd1Δ/Δ::PSD1 (YLC294), psd2Δ/Δ (YLC271), psd2Δ/Δ::PSD2 (YLC290) and psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ (YLC375). The media used to culture strains was YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone and 2% dextrose).

Lipid isolation for mass spectrometry analysis

Lipid isolations were adapted from the protocol of Singh et al. (2010). Cultures were grown overnight, shaking at 30°C in 5 mL of YPD. Cultures were then diluted to 0.4 OD600 in 25 mL of YPD and grown for 6 h, shaking at 30°C. After 6 h, cultures were pelleted and washed twice with PBS. The final pellets were incubated for at least 1 h at -80°C, and then lyophilized overnight. Dry mass was then recorded for normalization and pellets were suspended in 500 μL to 1 mL of PBS. The resulting thick suspension was then transferred to Teflon-capped glass tubes (Pyrex) and 1.5 mL of methanol was added. Two scoops of 150–212 μm sized glass beads (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were added to each tube. Cells were lysed by vigorous vortexing for 30 s punctuated by 30-s incubations on ice. Three mL of chloroform was added and the solution was vortexed briefly before being transferred to 15 mL glass funnel filtration system (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) with 24 mm glass microfiber filters (Whatman). Liquid collected was then poured into a separating funnel and washed with 900 μL of sterile 0.9% NaCl. The mixture was allowed to sit and separate for at least 5 min, or until adequate separation of the organic and aqueous layers was observed. The lower organic layer only was collected carefully into fresh Teflon-capped glass tubes. The organic layer was then dried under nitrogen gas until completely dry and stored at –20°C. Immediately before mass spectrometric analysis, the lipid extracts were resuspended in 300 μL of 9:1 methanol:chloroform (v/v).

Mass spectrometry lipidomics

Lipid extracts were separated on a Kinetex HILIC column (150 mm x 2.1 mm, 2.6 μm: (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) connected to an Ultimate 3000 UltraHigh Performance Liquid Chromatograph (UHPLC) with autosampler and an Exactive benchtop Orbitrap mass spectrometer (MS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA) equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) probe. The column oven temperature was maintained at 25°C, and the temperature of the autosampler was set to 4°C. For each analysis, 10 μL was injected onto the column. Separations ran for 35 min at a UHPLC flow rate of 0.2 mL/min with mobile phases A and B consisting of 10 mM aqueous ammonium formate pH 3 and 10 mM ammonium formate pH 3 in 93% (v/v) respectively. The gradient started at 100% B and was altered based on the following profile: t = 0 min, 100% B; t = 1 min, 100% B; t = 15 min, 81% B, 29% A; t = 15.1 min, 48% B, 52% A; t = 25 min, 48% B, 52% A; t = 25.1 min, 100% B, t = 35 min, 100% B. The same LC conditions and buffers were used for all MS experiments described below.

The MS spray voltage was set to 4 kV, and the heated capillary temperature was set at 350°C. The sheath and auxiliary gas flow rates were set to 25 units and 10 units, respectively. These conditions were held constant for both positive and negative ionization mode acquisitions, which were both performed for every sample. External mass calibration was accomplished using the standard calibration mixture and protocol from the manufacturer approximately every 2 days. For full scan profiling experiments, the MS was run with resolution of 140 000 with a scan range of 113–1700 m/z. For lipid identification studies, HCD fragmentation experiments were run. These experiments were performed by alternating between full scan acquisitions and all ion fragmentation HCD scans. Samples were analyzed in both positive and negative mode, and full scan settings were the same as listed above. For the all ion fragmentation scans, the resolution was 140 000 with a scan range of 113–1700 m/z. The normalized collision energy was 30 eV, and a stepped collision energy algorithm of 50% was used. Full scan MS data were evaluated using Maven software (Melamud, Vastag and Rabinowitz 2010), and lipid classes were identified by their fragments using the Xcalibur software package (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and information from the LIPID MAPS initiative (Fahy et al. 2007).

Lipid species were verified using retention times, high mass accuracy and fragmentation data. Internal standards were not used in this study; therefore, the relative amounts of each phospholipid species are presented. Interclass comparisons are possible, although some approximation of the relative intensities is inherent due to differing ionization efficiencies among lipids with different acyl chain lengths. Adequate separation of phospholipids was seen as shown in Fig. S1 (Supporting Information).

PS synthase assay

This procedure was done as previously described with minor alterations (Bae-Lee and Carman 1984; Matsuo et al. 2007; Cassilly et al. 2016). Cultures were grown overnight and then diluted into 1 L YPD, to ∼0.1 OD600/mL. These cultures were shaken at 30°C for 6 to 10 h. Cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 6000 x g for 20 min. Pellets were then transferred to 50 mL conical tubes and washed with water and re-pelleted. Supernatant was removed and the wet weight of the samples was taken. Cell pellets were stored overnight in –80°C. The following day, a cold mixture of 0.1 M Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol (BME), 10% glycerol, and protease inhibitors (phenylmethylsuphonyl fluoride, leupeptin and pepstatin) was added to the frozen pellets (1mL/g [wet weight]) and allowed to thaw on ice. Cells were lysed using a either a French Press (three passes at ∼13 000 lb/in2) or using osmotic lysis (Graham et al. 1994). The homogenate was centrifuged at 4°C for 5 min at 3000 rpm to clear unbroken cells and heavy material. Supernatant was then spun again at 27000× g for 10 min at 4°C. For some experiments, the resulting supernatant was then spun at 100 000× g to collect the lower density membranes. Pellets were resuspended in 500 μL to 1 mL of 0.1 M Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 5 mM BME, 10% glycerol and protease inhibitors. This mixture was aliquoted into microcentrifuge tubes and homogenized to break apart clumps, keeping on ice as much as possible. Total crude protein concentration was determined using a Bradford assay. The optimal assay mixture contained 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.5 mM MnCl2 and 0.1 mM CDP-DAG (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL, USA) added as a suspension in 1% Triton X-100 and 0.4–0.5 mg protein in a total volume of 0.1 mL.

The PS synthase assay was performed by monitoring the incorporation of 0.5 mM l-serine spiked with 5% (by volume) [3H]-l-serine (∼20 Ci/mmol) into the chloroform-soluble product at 37°C for a predetermined amount of time. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 1 mL chloroform: methanol (2:1). Following a low-speed spin, 800 to 1000 μL of the supernatant was removed to a fresh tube and washed with 200 μL 0.9% NaCl. Following a second low-speed spin, 400–500 μL of the chloroform phase was removed to a new tube and washed with 500 μL of chloroform: methanol: 0.9% NaCl (3:48:47). Following a third low-speed spin, 200–300 μL was transferred into scintillation vials (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Tubes were left open in the hood until dried fully. The next day, 2.5 mL scintillation fluid was added to each tube and run through the scintillation counter.

Statistical analysis

Graphs were made using GraphPad Prism version 6.04. Unpaired t-tests were used to determine significance between results. The lipidomics data were normalized by dry weight prior to statistical analyses.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

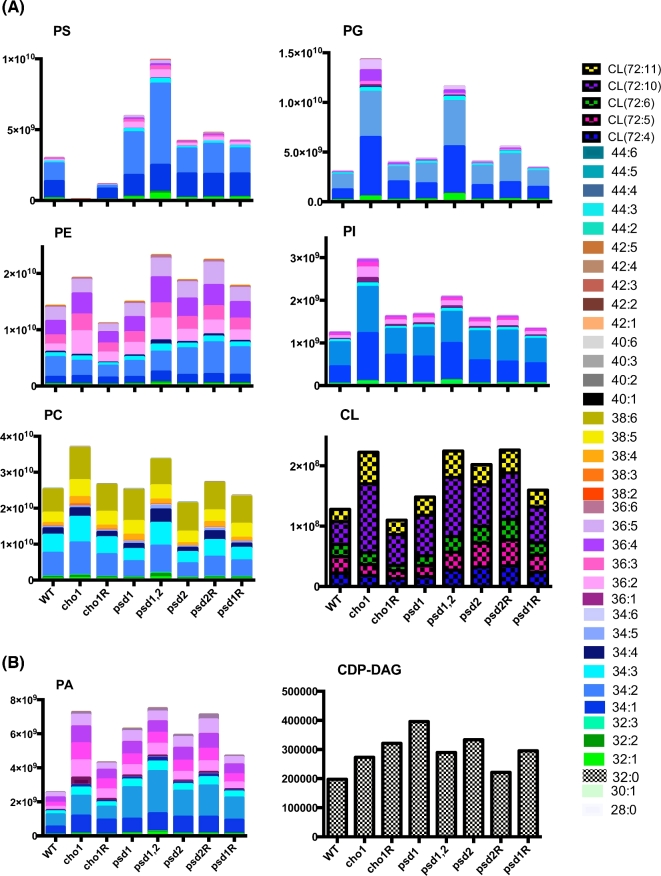

Phospholipids synthesized in the de novo pathway are dominated by 34:n species

Phospholipid profiles have previously been generated for the cho1Δ/Δ, psd1Δ/Δ and psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ mutants using [32P]-labeled phospholipids and thin layer chromatography (TLC) (Chen et al. 2010b). However, TLC only reveals levels of different lipid classes (polar head groups). We also wanted to determine the differences among the individual species (fatty acid composition) within each class. Thus, profiles of the major phospholipid classes were generated via lipidomics from lipids extracted from wild-type, cho1Δ/Δ, cho1Δ/Δ::CHO1, psd1Δ/Δ, psd1Δ/Δ::PSD1, psd2Δ/Δ, psd2Δ/Δ::PSD2 and psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ strains of Candida albicans. The lipids were analyzed by UHPLC-ESI-MS using the protocol described in methods and materials and adequate separation of standard phospholipids was observed (Fig. S1). Profiles of PA, CDP-DAG, PI, PG, CL, PS, PE and PC from three biological replicates were generated and are shown in Fig. 2. Statistically significant differences for particular species within each class compared to wild-type are shown in Table S1 (Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

The phospholipid species profiles for the major classes of phospholipids in C. albicans phospholipid synthesis mutants. (A) The phospholipid species profiles are shown for the major phospholipid classes of phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylglycerol (PG), phosphatidylinositol (PI) and cardiolipin (CL). (B) The species profiles detected are shown for the precursor lipids phosphatidic acid (PA) and cytidyldiphosphate-diacylglycerol (CDP-DAG). For each lipid class, a stacked bar graph is used and the species associated with each color is shown in the legend based on the combined carbon content and number of unsaturated bonds within the fatty acid component of the phospholipid. The Y-axis of the graph is the area under the peak for each species based on spectral profiles. The X-axis is the strains, which are as follows: wild-type (WT), cho1 (cho1Δ/Δ), psd1 (psd1Δ/Δ), psd1,2 (psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ), psd2 (psd2Δ/Δ), psd2R (psd2Δ/Δ::PSD2), psd1R (psd1Δ/Δ::PSD1).

In the cho1Δ/Δ mutant, which lacks PS synthase (the initial step in the de novo pathway, Fig. 1), PS is essentially absent, as expected (Chen et al. 2010a) (Fig. 2). The cho1Δ/Δ::CHO1 reintegrant strain exhibited a modest return of PS levels as compared with the cho1Δ/Δ and wild-type strains. The reintegrant strain has only one copy of CHO1, so haploinsufficiency is a possible explanation of this result (Uhl et al. 2003). However, since the level of PS in the reintegrant is only about 37% of the wild type (Fig. 2), one allele may be dominant over the other. Candida albicans has well-documented heterozygosity, which could account for this result (Eckert and Muhlschlegel 2009). We were concerned that the lower level of PS synthase activity could be the product of a defect in the reintegration construct, but independently generated reintegration constructs yielded similar results in the PS synthase assay (data not shown).

The distribution of PS species in the wild-type consists predominantly of 34:n species, with 34:2 being the most prevalent (Fig. 2). The psd1Δ/Δ mutant, which lacks the dominant PS decarboxylase (predicted to be localized to the mitochondria; Birner et al. 2001, 2003) that converts PS to PE, exhibits an overall increase in PS, but especially of the 34:2 species. A slight increase in PS is seen in the psd2Δ/Δ mutant, which lacks the alternative PS decarboxylase (predicted to localize to the Golgi/endosome; Trotter and Voelker 1995). The reintegrant strains psd1Δ/Δ::PSD1 and psd2Δ/Δ::PSD2 also show slight increases in levels of PS. The psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ mutant, which lacks all PS decarboxylase activity (Chen et al. 2010a), has over a 3-fold increase in PS species overall, but individual species are overrepresented by 2- to 5-fold. The 34:n species, which were the most abundant in wild type, are also the most abundant in psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ and are overrepresented by ∼5 fold compared to wild type. However, it appears that all species are decarboxylated to some extent, given that they build up as well.

PE is the direct downstream product of PS decarboxylation (Fig. 1), and loss of PS was expected to result in a sizeable decrease in PE, but surprisingly we saw increases in PE levels in most of our mutants (Fig. 2). Most of these changes are not statistically significant in the majority of mutants, including cho1Δ/Δ (Table S1), although they are for psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ. The maintenance of PE levels by the cho1Δ/Δ and psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ mutants is likely due to growing these cultures in YPD, a rich medium containing ethanolamine and choline. Since the cho1Δ/Δ and psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ mutants have no production of PE via the CDP-DAG pathway, it is likely that these mutants compensate through activity from the Kennedy pathway in order to synthesize PE. However, this remains to be experimentally verified. The psd1Δ/Δ mutant, which is the missing mitochondrial PS decarboxylase activity, showed wild-type levels of PE, suggesting that the loss of Psd1p was rescued by the redundant function of Psd2p. The psd2Δ/Δ strain exhibited an increase in PE, but this was again not statistically significant. The psd2Δ/Δ::PSD2 strain did have significant increases in many phospholipids, which was unexpected. The psd1Δ/Δ::PSD1 did not show many significant differences from wild type. Overall, the majority of PE species in wild type are of 36:n or 34:n, and even in the psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ where the changes were significant, this only shifted slightly compared to wild type.

Since the majority of PS is 34:n in wild-type cells, the Kennedy pathway may account for half of the PE population (34:n) or significant acyl remodeling of PS-derived PE is used to create other species after, or just prior to, decarboxylation. However, since a similar distribution of PE is found in wild-type, cho1Δ/Δ (totally lacks PS) and psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ strains (cannot convert PS to PE), this suggests that most of the 36:n PE is derived from the Kennedy pathway, and the Kennedy pathway also synthesizes 34:n PE efficiently or converts 36:n by acyl remodeling.

Previous studies with Saccharomyces cerevisiae showed an accumulation of PC in the Sccho1Δ mutant based on TLC analysis (Atkinson, Fogel and Henry 1980). Indeed, our data show an ∼1.5-fold increase in the level of PC in both the cho1Δ/Δ and psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ mutants when compared to the wild type (Fig. 2). The most obvious common relationship between cho1Δ/Δ and psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ is that both have a complete loss of de novo PE synthesis, which may indicate that this metabolic alteration causes an increase in PC synthesis via the Kennedy pathway. In the psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ or cho1Δ/Δ mutants, PC can be synthesized directly from choline and DAG via the Kennedy pathway or by methylation of Kennedy-pathway-derived PE via the de novo pathway (Fig. 1). However, from this data it is not possible to determine the level of PC coming directly from Kennedy pathway versus the methylation of Kennedy-pathway-derived PE to PC. Interestingly, the cho1Δ/Δ::CHO1 strain, which has only one allele of CHO1, has wild-type levels of PC. Loss of PS decarboxylase activity in psd1Δ/Δ or psd2Δ/Δ mutants has also little effect on PC levels when compared with that of wild type. Although there is a slight decrease in PC in the psd2Δ/Δ mutant, it does not appear to be statistically significant. These findings suggest that the organism strictly controls the production of PC to at least maintain wild-type levels. The majority of PC species are 36:n and 38:n. It is possible that the 36:n PC is formed through the de novo methylation of 36:n PE. The 38:n species are probably produced from the importation of exogenous choline. However, there are no striking changes within lipid species across mutant strains to support or falsify these hypotheses.

Increases in other CDP-DAG-derived phospholipids may be caused by an abundance of substrate in the PS synthase and PS decarboxylase mutants

Phosphatidic acid (PA) is the precursor for CDP-DAG (Henry, Kohlwein and Carman 2012) that is used to produce PS, PG and PI (Fig. 1). The cho1Δ/Δ mutant showed a nearly 3-fold increase in PA levels when compared to wild type (Fig. 2). These results were expected because the loss of PS synthesis causes a major blockage in de novo phospholipid synthesis, which would in turn lead to a build-up of the precursor molecule PA (substrate for CDP-DAG). This is further supported by the intermediate level of PA in cho1Δ/Δ::CHO1, which correlates with the partial return of PS production, and thus increased usage of PA. Varying increases are shown in PA levels within psd1Δ/Δ and psd2Δ/Δ mutants and their reintegrant strains, again potentially relating back to the build-up of PS in these strains, which translates into a build-up of PA. This is supported by the large increase in PA seen in psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ, which has no de novo PE production, and thus represents a blockage in this biosynthetic pathway.

We also aimed to analyze the levels of CDP-DAG within our mutants and found that we could only detect 32:0 species and that the overall levels of this precursor lipid were extremely low (Fig. 2B). This suggests that there is a high turnover of CDP-DAG and that it is rapidly used to produce PS, PI or PG. Although there was some variability within the CDP-DAG levels, including increases in most of the mutants tested, none of these changes were statistically significant when compared to wild type. However, the change in CDP-DAG levels within our mutants again could easily be attributed to a back-up in the de novo synthesis (either a halt of PS production or usage) which causes increases in CDP-DAG levels.

In addition to the precursors, we also looked at the levels of the other two phospholipids produced from CDP-DAG, PI and PG, as well as CL, which is produced from PG (Henry, Kohlwein and Carman 2012). Both the cho1Δ/Δ and the psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ mutants show increases in PI and PG levels. Where the cho1Δ/Δ PI levels increase by around 2.5-fold, the psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ increase is more modest. For PG we see an increase in both cho1Δ/Δ and psd1Δ/Δpsd2Δ/Δ, at ∼5-fold and 4-fold, respectively. These findings could be a result of more CDP-DAG being available for the production of PI and PG due to a blockage of PS synthesis (cho1Δ/Δ) or a build-up in PS (psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ). PI and PG seem to be tightly controlled, however, because in all other mutant and reintegrant strains the levels are closer to wild type. Finally, levels of CL correspond well with the changes in PG within our mutant strains. This indicates that some of the excess PG produced can be further modified to produce CL. These findings correlate well with studies in S. cerevisiae and confirm our previous results with TLC (Atkinson, Fogel and Henry 1980; Chen et al. 2010b). Interestingly, as with PS, the most abundant species of PI and PG appear to be 34:n; thus, it is possible that most CDP-DAG destined for PS synthesis is 34:n, but our lipidomics yields of CDP-DAG were too low to verify this, and it may be 34:n CDP-DAG is so rapidly processed into other lipids that it is hard to detect at steady state.

PS synthesis in PS synthase and PS decarboxylase mutants

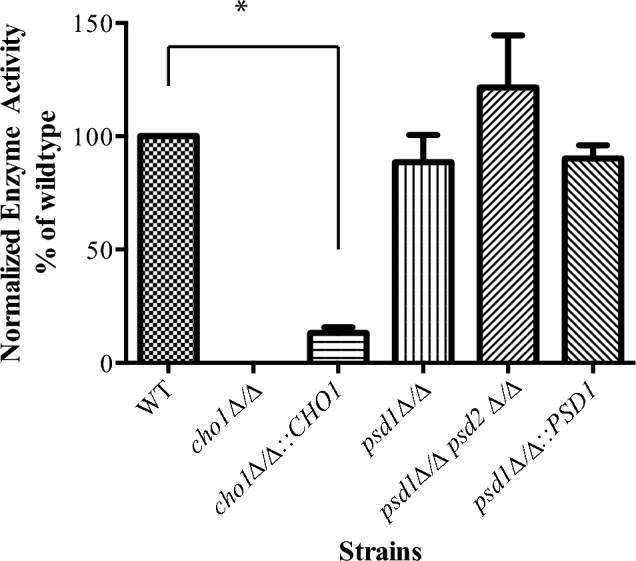

The psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ mutant exhibits a large increase in PS levels (Fig. 2), which is presumed to be caused by decreased decarboxylation of PS to PE. However, it is possible that this is due to increased PS synthase activity instead. This seemed doubtful, but to test this, an in vitro PS synthase assay was performed on cellular membranes, which were isolated from cell lysates via a 27 000 × g centrifugation step. Additional low-density membranes were isolated via a 100 000 × g centrifugation step. However, as highly variable results were found in the 100 000 × g membrane prep, data were generated from the 27 000 × g membranes which provided more consistent results. The assay was used to compare the incorporation of [3H]-serine into membranes on the addition of CDP-DAG. We compared incorporation for wild-type, cho1Δ/Δ, cho1Δ/Δ::CHO1, psd1Δ/Δ, psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ and psd1Δ/Δ::PSD1 strains. Wild-type levels of PS synthase activity were seen in the wild-type, psd1Δ/Δ and psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ strains, indicating that these strains have similar enzyme activities (Fig. 3). Thus, the excess PS in the psd1Δ/Δ psd2Δ/Δ mutant is likely a product of the loss of PS decarboxylase activity and build-up of substrate, not excess PS synthase activity.

Figure 3.

PS synthase activity across strains. Cho1p activity within different mutant strains of C. albicans. Cellular membranes containing Cho1p were isolated and treated with CDP-DAG and [3H]-serine. Activity is measured as counts per minute per milligram of protein. Values are shown as an average of three experiments averaged and normalized to the wild-type (WT) control. P < 0.0001.

As expected from this assay, the cho1Δ/Δ mutant exhibited no PS synthase activity. However, the cho1Δ/Δ::CHO1 reintegrant strain had only about 10% of the activity of the wild type. This compares with the decreased PS levels in the reintegrant as measured by lipidomics (Fig. 2). Haploinsufficiency may account for this lower activity.

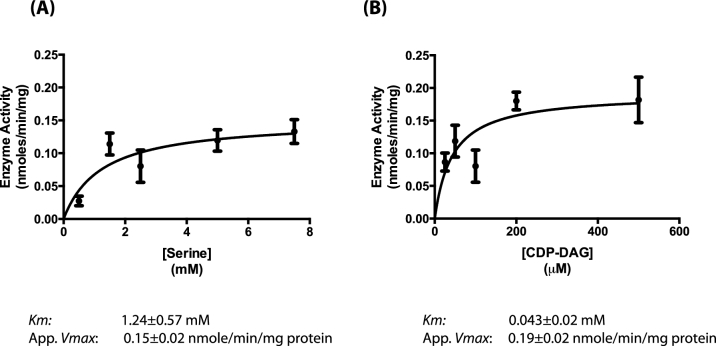

Candida albicans Cho1p enzyme kinetics are similar to those reported for Saccharomyces cerevisiae

The wild-type and other strains seemed to have similar PS synthase activity levels, but it was of interest to know more about the enzyme kinetics of C. albicans Cho1p, if it is to be considered for potential use as a drug target. The Km and apparent Vmax of this enzyme were calculated for both serine and CDP-DAG (Fig. 4). l-Serine, where the CDP-DAG was held constant at 0.1 mM, yielded a Km of 1.2 ± 0.57 mM and an apparent Vmax of 0.15 ± 0.02 nmole/min/mg of protein (Fig. 4A). For CDP-DAG, where the serine was held constant at 2.5 mM, a Km of 43.17 ± 19.18 μM and an apparent Vmax of 0.19 ± 0.023 nmole/min/mg of protein (Fig. 4B) were obtained. Interestingly, the intracellular concentration of serine in S. cerevisiae has been estimated to be around 2 mM on average (Hans, Heinzle and Wittmann 2003), which fits well with the Km for serine. These assays were performed on the crude 27 000 × g membranes in order to determine their kinetics within native membranes. These compare relatively closely with what has been reported for S. cerevisiae (Bae-Lee and Carman 1984).

Figure 4.

Enzyme kinetics for Cho1p. The PS synthase assay was performed with varying concentrations of substrate over time courses to generate enzyme kinetics for both substrates. (A) The Michaelis-Menton curve for the l-serine substrate shows a Km of 1.243 ± 0.5715 mM and an apparent Vmax of 0.1514 ± 0.02059 nmole/min/mg of protein. (B) The Michaelis-Menton curve for the CDP-DAG substrate shows a Km of 43.17 ± 19.18 μM and an apparent Vmax of 0.1919 ± 0.02361 nmole/min/mg of protein.

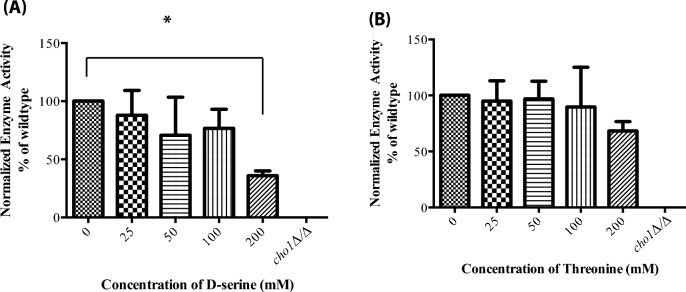

To control for the possibility that similar substrate molecules to serine might give a similar activity, which could cast doubt on the accuracy of the assay, we determined whether increasing concentrations of cold d-serine or threonine (similar amino acid) could compete with [3H]-l-serine for incorporation into [3H]-PS. Only at the highest concentration of 200 mM (×400) did the cold d-serine show any competition with l-serine (Fig. 5). Threonine showed no statistically significant competition with l-serine, even at 200 mM (×400). As a control, cold l-serine eliminated incorporation of [3H]-l-serine at a ×10 concentration (5 mM). Thus, this assay would not yield a product with these two similar molecules, suggesting that the assay is specifically measuring activity against l-serine.

Figure 5.

Cho1p shows specificity for l-serine. The PS synthase assay was performed with 0.5 mM [3H]-serine and 0.1 mM CDP-DAG. An excess of d-serine (A) or l-threonine (B) was added at varying concentrations. Only d-serine or l-threonine at concentrations 400-fold that of l-serine show any inhibition in [3H]-PS production. Values are shown as an average of three experiments averaged and normalized to the wild-type control. P = 0.0361.

CONCLUSIONS

The loss of de novo PE synthesis and/or PS synthesis has striking effects on the phospholipidome, which are consistent with what we know from fungal phospholipid metabolism. In particular, the loss of the de novo pathway for PS and/or PE synthesis appears to increase the synthesis of other CDP-DAG-dependent phospholipids like PI and PG (Fig. 2). Surprisingly, PE and PC levels appear to be buffered against change, presumably by the activity of the Kennedy pathway. The 34:n species are the most prominent forms of PS, and 34:2 in particular, appears to be the most actively used substrate by PS decarboxylase enzymes to synthesize PE. The 34:2 species is also what builds up in PI and PG, which may suggest that either Cho1p preferentially uses 34:2 CDP-DAG or 34:2 CDP-DAG is what it encounters in its subdomains in the ER.

Finally, our analysis of the enzymology of Cho1p from Candida albicans reveals that it is very similar to Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and changes in PS levels follow changes in Cho1p activity. For example, when PS synthesis activity is compared to PS levels in the wild-type, cho1Δ/Δ::CHO1 and cho1Δ/Δ strains, these measurements seem to correlate with one another rather closely (Figs 2 and 3). These analyses set the stage for better understanding how strategies to inhibit de novo PS or PE synthesis, which are required for virulence of C. albicans (Chen et al. 2010a), may impact overall lipid profiles and ability to cause disease.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at FEMSYR online.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Joel C. Bucci at Louisiana State University and Dr Melinda Hauser at the University of Tennessee for their advice and guidance with enzyme kinetics experiments and calculations. The authors would also like to thank Dr Jana Patton-Vogt at Duquesne University for technical assistance with the PS synthase assay.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at FEMSYR online.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health NIH R01AL105690.

Conflict of interest. None declared.

REFERENCES

- Atkinson K, Fogel S, Henry SA. Yeast mutant defective in phosphatidylserine synthesis. J Biol Chem 1980;255:6653–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae-Lee MS, Carman GM. Phosphatidylserine synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Purification and characterization of membrane-associated phosphatidylserine synthase. J Biol Chem 1984;259:857–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birner R, Burgermeister M, Schneiter R et al. . Roles of phosphatidylethanolamine and of its several biosynthetic pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 2001;12:997–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birner R, Nebauer R, Schneiter R et al. . Synthetic lethal interaction of the mitochondrial phosphatidylethanolamine biosynthetic machinery with the prohibitin complex of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 2003;14:370–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun BR, van Het Hoog M, d’Enfert C et al. . A human-curated annotation of the Candida albicans genome. PLoS Genet 2005;1:–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassilly CD, Maddox MM, Cherian PT et al. . SB-224289 antagonizes the antifungal mechanism of the marine depsipeptide papuamide A. PLoS One 2016;11:e0154932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YL, Montedonico AE, Kauffman S et al. . Phosphatidylserine synthase and phosphatidylserine decarboxylase are essential for cell wall integrity and virulence in Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol 2010a;75:12–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YL, Montedonico AE, Kauffman S et al. . Phosphatidylserine synthase and phosphatidylserine decarboxylase are essential for cell wall integrity and virulence in Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol 2010b;75:12–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert SE, Muhlschlegel FA. Promoter regulation in Candida albicans and related species. FEMS Yeast Res 2009;9:2–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy E, Sud M, Cotter D et al. . LIPID MAPS online tools for lipid research. Nucleic Acids Res 2007;35:W606–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghannoum MA, Rice LB. Antifungal agents: mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev 1999;12:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibellini F, Smith TK. The Kennedy pathway–De novo synthesis of phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine. IUBMB Life 2010;62:4–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham TR, Seeger M, Payne GS et al. . Clathrin-dependent localization of alpha 1,3 mannosyltransferase to the Golgi complex of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol 1994;127:7–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans MA, Heinzle E, Wittmann C. Free intracellular amino acid pools during autonomous oscillations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Bioeng 2003;82:3–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry SA, Kohlwein SD, Carman GM. Metabolism and regulation of glycerolipids in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2012;190:7–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holeman CW Jr, Einstein H. The toxic effects of amphotericin B in man. Calif Med 1963;99:90–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low CY, Rotstein C. Emerging fungal infections in immunocompromised patients. F1000 Med Rep 2011;3:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo Y, Fisher E, Patton-Vogt J et al. . Functional characterization of the fission yeast phosphatidylserine synthase gene, pps1, reveals novel cellular functions for phosphatidylserine. Eukaryot Cell 2007;6:92–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melamud E, Vastag L, Rabinowitz JD. Metabolomic analysis and visualization engine for LC-MS data. Anal Chem 2010;82:18–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra NN, Prasad T, Sharma N et al. . Pathogenicity and drug resistance in Candida albicans and other yeast species. A review. Acta Microbiol Imm H 2007;54:1–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell M, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH. Delaying the empiric treatment of candida bloodstream infection until positive blood culture results are obtained: a potential risk factor for hospital mortality. Antimicrob Agents Ch 2005;49:40–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller M, Neofytos D, Diekema D et al. . Epidemiology and outcomes of candidemia in 3648 patients: data from the Prospective Antifungal Therapy (PATH Alliance(R)) registry, 2004–2008. Diagn Micr Infec Dis 2012;74:3–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Prasad T, Kapoor K et al. . Phospholipidome of Candida: each species of Candida has distinctive phospholipid molecular species. Omics 2010;14:5–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Yadav V, Prasad R. Comparative lipidomics in clinical isolates of Candida albicans reveal crosstalk between mitochondria, cell wall integrity and azole resistance. PLoS One 2012;7:e39812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotter PJ, Voelker DR. Identification of a non-mitochondrial phosphatidylserine decarboxylase activity (PSD2) in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 1995;270:62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl MA, Biery M, Craig N et al. . Haploinsufficiency-based large-scale forward genetic analysis of filamentous growth in the diploid human fungal pathogen C.albicans. EMBO J 2003;22:68–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisplinghoff H, Bischoff T, Tallent SM et al. . Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data are available at FEMSYR online.