Abstract

The public expressed sequence tag collections are continually being enriched with high-quality sequences that represent an ever-expanding range of taxonomically diverse plant species. While these sequence collections provide biased insight into the populations of expressed genes available within individual species and their associated tissues, the information is conceivably of wider relevance in a comparative context. When we consider the available expressed sequence tag (EST) collections of summer 2004, most of the major plant taxonomic clades are at least superficially represented. Investigation of the five million available plant ESTs provides a wealth of information that has applications in modelling the routes of plant genome evolution and the identification of lineage-specific genes and gene families. Over four million ESTs from over 50 distinct plant species have been collated within an EST analysis pipeline called openSputnik. The ESTs were resolved down into approximately one million unigene sequences. These have been annotated using orthology-based annotation transfer from reference plant genomes and using a variety of contemporary bioinformatics methods to assign peptide, structural and functional attributes. The openSputnik database is available at http://sputnik.btk.fi.

INTRODUCTION

Complete genome sequencing has become the standard modus operandi for bacterial genomics, and tens of eukaryotic genomes have also been completely sequenced (see http://www.genomesonline.org). Plant genomics is, however, frequently hindered by the typically large and repetitive nature of the genome. Certain plant species have genome sizes that dwarf the human genome; the 1C genome size for broad bean (Vicia faba) is at least 26 000 Mb (Plant DNA C-values database), or over eight times the size of the human genome. The selection of candidate plant genomes for complete sequencing is, therefore, based on the scientific and anthropocentric value of the plant and the feasibility of a meaningful sequencing and assembly strategy. While several diverse plant species [Arabidopsis thaliana (1), Oryza sativa (2,3) and Populus trichocarpa] have been or will shortly be completely sequenced, the majority of plant genomes remain largely inaccessible. Arabidopsis and rice are certainly model plant systems but, are neither truly representative of any other given species nor are they general indicators for gene content across the whole plant kingdom. The first forays into comparative plant genomics using Arabidopsis and rice as reference genomes have demonstrated that there is a remarkable degree of underlying sequence diversity between these species (2,3). This firmly advocates the need to at least sample the protein-coding component of more taxonomically ‘exotic’ plant genomes.

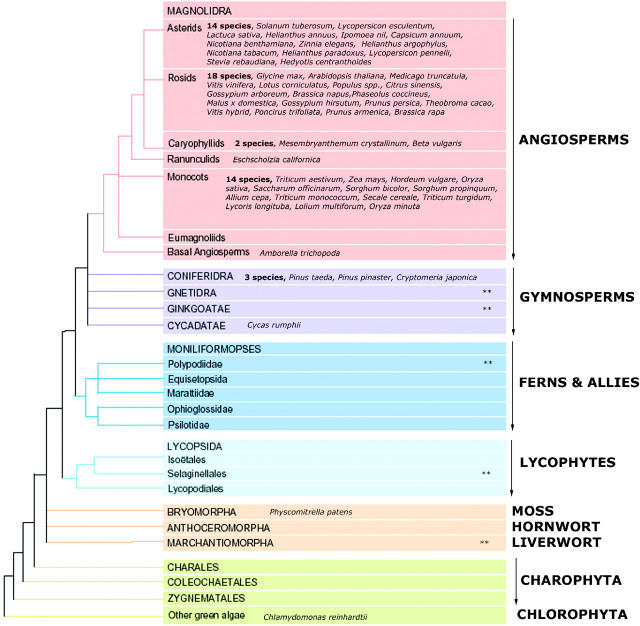

cDNA preparation and expressed sequence tag (EST) sequencing remain a dominant methodology for accessing the protein coding (and expressed) portion of the genome. Many laboratories are independently sequencing very large numbers of sequences from a broad and bio-diverse spectrum of plant species (Figure 1). EST sequences retain their exalted status for several reasons [for a review see (4)].

They are technically simple to produce and cheap to sequence.

ESTs provide a robust approximation of the expressed gene content of the parental genome under given sampling conditions and can be used for primitive expression profiling between tissues (5).

The extensive redundancy typical of EST collections also allows for the selection of putative molecular markers (6,7).

cDNAs may be used as a substrate for arraying, to create cDNA microarrays; this allows for true gene expression profiling (8).

Figure 1.

A depiction of the phylogenetic relationships among the major plant lineages as published previously (23). The evolutionary tree has been overlaid with the names of plant species having large EST collections (>5000 sequences) that are available in the current release of openSputnik. The symbol ‘**’ denotes the plant groups where either small EST collections (>1000 ESTs) are available or as-yet unreleased sequences are known to exist. This figure reveals the taxonomic distribution of large plant EST collections, but also highlights the strong bias towards the agriculturally important species.

With an excess of 5.4 million sequences from over 320 species, the current public plant EST sequence databases (EMBL release 80) (9) are a valuable and contextually rich but under-utilized resource. If we consider just the large EST collections with over 5000 ESTs, 5.1 million ESTs from 74 species are represented. These species, while highly biased towards the key plant taxonomic clades of the rosids, asterids and monocots, still contain representative species, from other key taxonomic groups. The species represented contain representatives of single cellularity—the red and brown algae and lower plants—gymnosperms, basal angiosperms and the angiosperms. With such a wealth of signals for investigation of the underlying genomic changes in gene-content, protein structures and domain composition, the EST collections surely deserve detailed analysis and investigation.

The openSputnik database has been designed as an interim platform for the exhaustive annotation and analysis of EST sequences in a comparative context. In addition to clustering sequences, a peptide sequence is identified, thus, providing a more sensitive target for the identification of functional and structural features. Sequences are placed in context with the currently available complete plant genomes and are associated with other clustered EST collections. The openSputnik database, thus, creates a platform upon which the intricate patterns of generalist house-keeping genes and lineage-specific gene families may be teased apart. The completed EST project annotations are available as a searchable web resource. While the provision of an integrated resource containing a diverse mixture of clustered and contextually placed unigene sequences is not unique [e.g. TIGR Gene Indices database (10), NCBI Unigenes (11) or PlantGDB at Iowa State University (12)], the openSputnik database is currently distinct in its focus towards functionally describing unigene sequences on the basis of both orthologous gene annotations and the application of bioinformatics methods for ab initio annotations.

IMPLEMENTATION AND STARTING MATERIAL

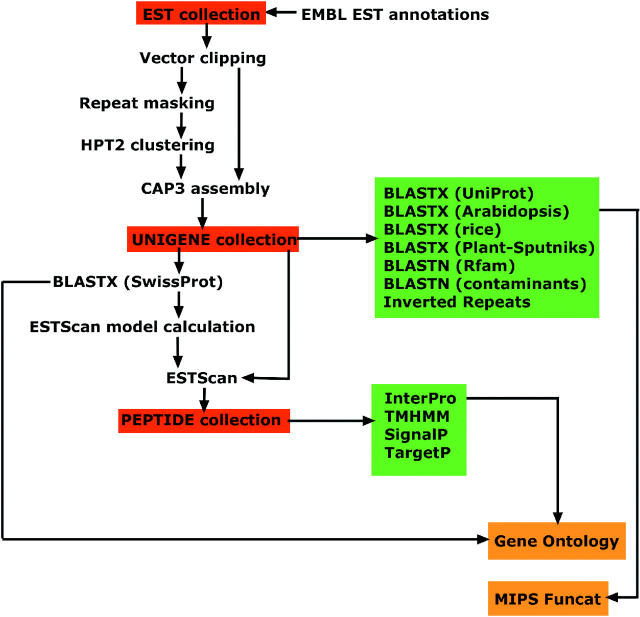

The openSputnik database has been programmed using the Java programming language and utilizes the PostgreSQL relational database management system to archive and retrieve sequences and their annotations. Therefore, openSputnik is largely platform-independent and has been implemented using a server–client model to allow for calculation in a distributed and heterogeneous computational environment. The methods implemented within openSputnik are described as functional objects and the analytical pathway is described as a directed acyclic graph (Figure 2). The current version of openSputnik utilizes the complete public plant EST collection that was available from the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) at the start of Spring 2004 (EMBL release 78). A rule was imposed so that EST collections of at least 4500 sequences would be included. Over four million EST sequences representing 55 distinct plant species were identified using this rule. These sequences were loaded onto the openSputnik database schema.

Figure 2.

A simplification of the directed acyclic graph that describes the analytical pipeline used to build the openSputnik database. As starting material, species-specific EMBL flat files are imported and all annotations are retained. This creates a sequence source ‘EST collection’. This source is used to derive two other annotative sources, the ‘UNIGENE collection’ and the ‘PEPTIDE collection’ (sources shown in red). When the sources have been built, they are annotated using a variety of methods highlighted in green. The analyses anchored to the schema are used to create derived annotations including Funcat and GO terms (shown in orange). All analyses are made available to the database user via the openZputnik interface.

SEQUENCE CLUSTERING

Prior to sequence clustering, ESTs were aggressively trimmed of any likely residual vector or polylinker sequences using the Crossmatch application (P. Green, unpublished data) and the National Center for Bioinformatics Information (NCBI) UniVec database. Sequences <55 nt in length were excluded at this stage. To prevent the aggregation of sequences on the basis of low complexity sequence islands, all low complexity sequences were masked using the RepeatBeater algorithm (Biomax informatics, Martinsried, Germany). The masked sequences were clustered into pools of related sequences using a suffix tree based approach (HPT2 algorithm; Biomax informatics). To encourage the aggregation of sequences, HPT2 was run using a similarity threshold of 0.7 and a number of network iterations equalling the number of masked ESTs. The resulting clusters were assembled into unigene sequences using the CAP3 algorithm with standard settings. Within the larger EST collections, some HPT2 identified clusters contain many members. To simplify the analysis, larger clusters were truncated to an arbitrary threshold of a maximum of 2500 ESTs. Some individual ESTs representing the most highly expressed genes were absent from their cognate unigenes.

PEPTIDE PREDICTION

It is probable that each derived unigene sequence represents an expressed and properly spliced mRNA. Extensive amounts of either 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) or 3′-UTR may exist within the unigene sequences. The identification of a meaningful peptide sequence lends value to the dataset by allowing us to exclude sequences of low protein-coding potential, and additionally allows the use of peptide-annotation algorithms. ESTScan (13) models have been trained for each of the underlying species. Training data were produced by identifying probable open reading frame (ORF) sequences from a BLASTX (14) analysis against the Swiss-Prot (15) database arbitrarily filtered at 1E−10. ESTScan was used with the derived model to predict the most likely peptide for each unigene sequence. The numbers of ESTs, unigenes and peptides are shown for each of the 55 openSputnik plant species along with estimates of actual coding potential and redundancy across the individual libraries (Table 1).

Table 1. Table summarizing the sequence content of the openSputnik database.

| Organism name | No. of ESTs | EST sequence (bp) | No. of singletons | No. of assembies | Unigene sequence (bp) | Redundancy | Peptide sequence (aa) | Protein coding potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allium cepa | 19 582 | 13 016 289 | 7252 | 4020 | 8 544 747 | 1.5 | 2 531 519 | 88.9 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | 190 741 | 84 128 065 | 17 675 | 20 109 | 22 482 688 | 3.7 | 6 135 202 | 81.9 |

| Beta vulgaris | 20 151 | 10 184 665 | 9244 | 3706 | 7 368 791 | 1.4 | 2 015 990 | 82.1 |

| Brassica napus | 37 159 | 21 438 036 | 8041 | 5447 | 8 389 217 | 2.6 | 2 403 184 | 85.9 |

| Capsicum annuum | 22 433 | 10 226 020 | 7326 | 3056 | 5 496 951 | 1.9 | 1 477 080 | 80.6 |

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | 154 600 | 82 230 382 | 18 211 | 10 989 | 23 178 755 | 3.5 | 2 388 596 | 30.9 |

| Citrus sinensis | 23 337 | 12 738 998 | 5311 | 3416 | 5 474 795 | 2.3 | 1 473 294 | 80.7 |

| Cryptomeria japonica | 7128 | 3 624 193 | 3202 | 1203 | 2 457 784 | 1.5 | 579 834 | 70.8 |

| Cycas rumphii | 5952 | 2 873 079 | 2230 | 697 | 1 597 282 | 1.8 | 349 001 | 65.5 |

| Eschscholzia californica | 5468 | 2 529 150 | 3146 | 741 | 1 908 962 | 1.3 | 564 147 | 88.7 |

| Glycine max | 344 524 | 158 703 384 | 28 963 | 24 892 | 33 585 032 | 4.7 | 8 648 792 | 77.3 |

| Gossypium arboreum | 38 915 | 26 139 867 | 10 007 | 6076 | 13 043 919 | 2.0 | 2 958 835 | 68.1 |

| Gossypium hirsutum | 13 571 | 8 414 112 | 5934 | 1914 | 5 367 083 | 1.6 | 1 334 901 | 74.6 |

| Hedyotis centranthoides | 5416 | 2 476 009 | 3595 | 641 | 2 022 087 | 1.2 | 450 943 | 66.9 |

| Hedyotis terminalis | 4875 | 2 228 284 | 3313 | 530 | 1 830 094 | 1.2 | 402 306 | 65.9 |

| Helianthus annuus | 59 841 | 25 553 028 | 11 900 | 6050 | 8 654 947 | 3.0 | 2 086 806 | 72.3 |

| Helianthus argophyllus | 12 787 | 4 929 193 | 4646 | 1029 | 2 309 089 | 2.1 | 516 763 | 67.1 |

| Helianthus paradoxus | 10 340 | 4 149 627 | 3844 | 1012 | 1 997 115 | 2.1 | 458 465 | 68.9 |

| Hordeum vulgare | 372 431 | 198 114 717 | 25 405 | 23 033 | 37 345 565 | 5.3 | 9 139 515 | 73.4 |

| Ipomoea nil | 25 899 | 15 289 506 | 4572 | 4829 | 6 252 258 | 2.4 | 1 682 965 | 80.8 |

| Lactuca sativa | 68 188 | 35 969 889 | 12 427 | 7998 | 13 090 218 | 2.7 | 3 527 514 | 80.8 |

| Lotus corniculatus | 36 311 | 13 987 475 | 7646 | 4248 | 5 529 908 | 2.5 | 1 635 214 | 88.7 |

| Lycopersicon esculentum | 150 228 | 75 468 371 | 13 178 | 14 870 | 19 372 969 | 3.9 | 5 380 403 | 83.3 |

| Lycopersicon pennellii | 8346 | 3 842 358 | 2408 | 901 | 1 770 921 | 2.2 | 503 014 | 85.2 |

| Medicago truncatula | 187 763 | 101 662 463 | 19 448 | 17 189 | 27 597 708 | 3.7 | 6 630 342 | 72.1 |

| Mesembryanthemum crystallinum | 25 803 | 15 782 659 | 4831 | 3137 | 5 941 245 | 2.7 | 1 541 786 | 77.9 |

| Nicotiana tabacum | 10 323 | 5 104 499 | 8710 | 630 | 4 738 148 | 1.1 | 952 839 | 60.3 |

| Oryza minuta | 5268 | 2 367 832 | 2756 | 591 | 1 658 572 | 1.4 | 452 963 | 81.9 |

| Oryza sativa | 260 901 | 136 090 821 | 30 971 | 20 934 | 34 467 815 | 3.9 | 8 593 185 | 74.8 |

| Phaeodactylum tricornutum | 12 121 | 7 911 359 | 3043 | 1526 | 3 439 590 | 2.3 | 894 960 | 78.1 |

| Phaseolus coccineus | 20 120 | 8 487 980 | 4419 | 2431 | 3 269 096 | 2.6 | 886 986 | 81.4 |

| Physcomitrella patens | 102 219 | 54 477 833 | 10 114 | 13 309 | 15 177 696 | 3.6 | 3 521 525 | 69.6 |

| Pinus pinaster | 15 719 | 7 679 661 | 4974 | 2452 | 4 209 291 | 1.8 | 1 036 699 | 73.9 |

| Pinus taeda | 110 622 | 51 626 003 | 14 632 | 11 610 | 15 972 215 | 3.2 | 3 945 832 | 74.1 |

| Poncirus trifoliata | 6390 | 4 107 970 | 1644 | 1209 | 2 220 609 | 1.8 | 568 758 | 76.8 |

| Populus alba | 10 446 | 5 769 749 | 3856 | 1480 | 3 192 053 | 1.8 | 862 949 | 81.1 |

| Populus balsamifera | 30 296 | 14 140 412 | 7031 | 3664 | 5 503 910 | 2.6 | 1 522 330 | 83.0 |

| Populus tremula | 70 091 | 30 629 346 | 14 699 | 7954 | 11 475 126 | 2.7 | 3 192 054 | 83.5 |

| Populus tremuloides | 13 050 | 6 174 206 | 2634 | 2218 | 2 413 573 | 2.6 | 706 585 | 87.8 |

| Porphyra yezoensis | 20 979 | 9 801 783 | 2774 | 2045 | 2 853 651 | 3.4 | 681 731 | 71.7 |

| Prunus persica | 11 452 | 6 496 591 | 3206 | 1588 | 3 135 288 | 2.1 | 883 165 | 84.5 |

| Saccharum officinarum | 246 301 | 156 538 942 | 29 895 | 25 089 | 45 845 406 | 3.4 | 11 003 162 | 72.0 |

| Saccharum spp. | 8807 | 4 377 943 | 4784 | 1155 | 3 165 611 | 1.4 | 788 520 | 74.7 |

| Secale cereale | 9194 | 4 313 461 | 3793 | 1346 | 2 687 830 | 1.6 | 662 342 | 73.9 |

| Solanum tuberosum | 94 525 | 51 346 134 | 6651 | 15 983 | 16 752 895 | 3.1 | 4 715 299 | 84.4 |

| Sorghum bicolor | 161 766 | 83 411 684 | 16 955 | 17 704 | 23 132 774 | 3.6 | 6 004 630 | 77.9 |

| Sorghum propinquum | 21 387 | 9 750 610 | 5371 | 3507 | 4 673 286 | 2.1 | 1 209 822 | 77.7 |

| Stevia rebaudiana | 5548 | 3 242 045 | 2498 | 713 | 2 048 965 | 1.6 | 578 303 | 84.7 |

| Theobroma cacao | 6562 | 2 607 871 | 1988 | 753 | 1 103 776 | 2.4 | 276 188 | 75.1 |

| Triticum aestivum | 511 732 | 257 643 801 | 49 171 | 33 666 | 51 549 049 | 5.0 | 12 964 652 | 75.5 |

| Triticum monococcum | 9973 | 4 956 308 | 3941 | 1681 | 3 212 869 | 1.5 | 810 910 | 75.7 |

| Vitis hybrid | 6533 | 3 604 678 | 1032 | 1052 | 1 385 939 | 2.6 | 349 250 | 75.6 |

| Vitis vinifera | 135 712 | 74 769 503 | 9616 | 12 893 | 16 019 102 | 4.7 | 4 176 665 | 78.2 |

| Zea mays | 384 391 | 173 945 698 | 24 266 | 25 725 | 29 187 808 | 6.0 | 7 017 868 | 72.1 |

| Zinnia elegans | 9783 | 4 896 796 | 6536 | 1456 | 4 140 824 | 1.2 | 890 004 | 64.5 |

A total of 55 plant species are included in the current release, and represent a broad taxonomic distribution of species. Shown are the number of ESTs and the total nucleotide length for all EST sequences. The number of resulting singleton unigenes and multi-member assemblies is shown, along with the summed length of all available unigene sequence. The difference between total nucleotide length in EST and unigene sequences is summarized as apparent redundancy. Since peptide sequences have been prepared for each of the unigenes the length of all derived peptide is also shown and a measure of apparent coding potential across the whole unigene set is also shown.

DATABASE CONTENTS

The unigene sequences and peptides from each of the included species have been annotated using a selection of bioinformatics tools that are relevant to comparative genomics and biological understanding. Sequences are annotated for structural and functional characters using InterPro domains (16), TMHMM for the identification of transmembrane domains (17), TargetP for the prediction of organellar targeting (18) and SignalP for subcellular localization (19). The blast algorithm is used to reflect similarities of individual sequences with known proteins in the Swiss-Prot database, predicted proteins in the UniProt database (20) and to organism specific sets of proteins not restricted to A.thaliana, O.sativa or aggregated plant proteins. The complete sequence collections are summarized using the MIPS catalogue of functionally annotated proteins (Funcat) (21) and Gene Ontology terms (22). A collection of methods has been implemented to provide the typical figures and charts that are often seen in EST collection publications. Graphical representation of sequence lengths, number of ESTs within unigenes and clone-library representation are all included. Also included are reports summarizing the functional distribution of unigenes using both GOSlims and the MIPS Funcat.

DATABASE ACCESS

A query interface to the openSputnik database is provided by a web application product written for the Zope web application server. The openZputnik portal at http://sputnik.btk.fi provides access to all core EST collections through a single unified interface. Selecting EST projects will display a list of all available projects. When an openSputnik collection is selected, an interface that provides routes to the underlying data will be displayed. Different methods are included for EST sequences, unigene sequences and peptide sequences. Additionally, a page is included to access sequences on the basis of pre-computed reports and a BLAST server is included so that sequences may be identified on the basis of similarity to a known sequence. Sequences may be identified on the basis of a variety of criteria not restricted to GC content, length, name or predicted function.

When a sequence is selected, a single page summary report is displayed for the sequence. This summarizes key information that includes wherever appropriate, the best BLAST matches, functional information and physical attributes. Navigation tabs are provided so that a user may access all primary information derived or associated with a single sequence.

DATA AVAILABILITY AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

All data within the openSputnik database is freely available to the scientific community. Please contact the author to request the inclusion of additional methods. The analytical pipeline may be applied to novel and proprietary sequence collections as either a collaboration with, or as a service of, the Bioinformatics Core facility provided at the Turku Centre for Biotechnology. The openSputnik SQL schema and complete database dumps are available upon request. The source code to the openSputnik engine and core reporting architecture is being open-sourced and released to Source Forge (www.sourceforge.com).

The openSputnik group will prepare one or two releases of the clustered plant unigenes per year. Additional plant species will be included into the pipeline as they exceed our arbitrary size threshold. Additional groups of organisms will be integrated in the future with a comparative mammalian unigene database planned for spring 2005. Additional emphasis is being placed on the creation of generic reports that can distil the essence of large and heterogeneous sequence collections. Further synchronization of the completed resources with the Gene Ontology and dynamic integration and comparison of groups of species is in progress. The challenge is to stay abreast with the ever-growing collections of sequences and the novel bioinformatics methodologies that offer us the ability to better understand the nuances within our sequence collections.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arabidopsis Genome Initiative (2000) Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature, 408, 796–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu J., Hu,S., Wang,J., Wong,G.K., Li,S., Liu,B., Deng,Y., Dai,L., Zhou,Y., Zhang,X. et al. (2002) A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. indica). Science, 296, 79–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goff S.A., Ricke,D., Lan,T.H., Presting,G., Wang,R., Dunn,M., Glazebrook,J., Sessions,A., Oeller,P., Varma,H. et al. (2002) A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica). Science, 296, 92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudd S. (2003) Expressed sequence tags: alternative or complement to whole genome sequences? Trends Plant Sci., 8, 321–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satou Y., Kawashima,T., Kohara,Y. and Satoh,N. (2003) Large scale EST analyses in Ciona intestinalis: its application as Northern blot analyses. Dev. Genes Evol., 213, 314–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thiel T., Michalek,W., Varshney,R.K. and Graner,A. (2003) Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of gene-derived SSR-markers in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Theor. Appl. Genet., 106, 411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kota R., Rudd,S., Facius,A., Kolesov,G., Thiel,T., Zhang,H., Stein,N., Mayer,K. and Graner,A. (2003) Snipping polymorphisms from large EST collections in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Mol. Genet. Genomics, 270, 24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drmanac R. and Drmanac,S. (1999) cDNA screening by array hybridization. Methods Enzymol., 303, 165–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kulikova T., Aldebert,P., Althorpe,N., Baker,W., Bates,K., Browne,P., van den Broek,A., Cochrane,G., Duggan,K., Eberhardt,R. et al. (2004) The EMBL Nucleotide Sequence Database. Nucleic Acids Res., 32, D27–D30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quackenbush J., Cho,J., Lee,D., Liang,F., Holt,I., Karamycheva,S., Parvizi,B., Pertea,G., Sultana,R. and White,J. (2001) The TIGR Gene Indices: analysis of gene transcript sequences in highly sampled eukaryotic species. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 159–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wheeler D.L., Church,D.M., Federhen,S., Lash,A.E., Madden,T.L., Pontius,J.U., Schuler,G.D., Schriml,L.M., Sequeira,E., Tatusova,T.A. et al. (2003) Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology. Nucleic Acids Res., 31, 28–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong Q., Schlueter,S.D. and Brendel,V. (2004) PlantGDB, plant genome database and analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res., 32, D354–D359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iseli C., Jongeneel,C.V. and Bucher,P. (1999) ESTScan: a program for detecting, evaluating, and reconstructing potential coding regions in EST sequences. Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol., 138–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altschul S.F., Gish,W., Miller,W., Myers,E.W. and Lipman,D.J. (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol., 215, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boeckmann B., Bairoch,A., Apweiler,R., Blatter,M.C., Estreicher,A., Gasteiger,E., Martin,M.J., Michoud,K., O'Donovan,C., Phan,I. et al. (2003) The SWISS-PROT protein knowledgebase and its supplement TrEMBL in 2003. Nucleic Acids Res., 31, 365–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mulder N.J., Apweiler,R., Attwood,T.K., Bairoch,A., Barrell,D., Bateman,A., Binns,D., Biswas,M., Bradley,P., Bork,P. et al. (2003) The InterPro Database, 2003 brings increased coverage and new features. Nucleic Acids Res., 31, 315–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krogh A., Larsson,B., von Heijne,G. and Sonnhammer,E.L. (2001) Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol., 305, 567–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emanuelsson O., Nielsen,H., Brunak,S. and von Heijne,G. (2000) Predicting subcellular localization of proteins based on their N-terminal amino acid sequence. J. Mol. Biol., 300, 1005–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bendtsen J.D., Nielsen,H., von Heijne,G. and Brunak,S. (2004) Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J. Mol. Biol., 340, 783–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Apweiler R., Bairoch,A., Wu,C.H., Barker,W.C., Boeckmann,B., Ferro,S., Gasteiger,E., Huang,H., Lopez,R., Magrane,M. et al. (2004) UniProt: the Universal Protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res., 32, D115–D119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mewes H.W., Frishman,D., Guldener,U., Mannhaupt,G., Mayer,K., Mokrejs,M., Morgenstern,B., Munsterkotter,M., Rudd,S. and Weil,B. (2002) MIPS: a database for genomes and protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 31–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris M.A., Clark,J., Ireland,A., Lomax,J., Ashburner,M., Foulger,R., Eilbeck,K., Lewis,S., Marshall,B., Mungall,C. et al. (2004) The Gene Ontology (GO) database and informatics resource. Nucleic Acids Res., 32, D258–D261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pryer K.M., Schneider,H., Zimmer,E.A. and Ann Banks,J. (2002) Deciding among green plants for whole genome studies. Trends Plant Sci., 7, 550–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data within the openSputnik database is freely available to the scientific community. Please contact the author to request the inclusion of additional methods. The analytical pipeline may be applied to novel and proprietary sequence collections as either a collaboration with, or as a service of, the Bioinformatics Core facility provided at the Turku Centre for Biotechnology. The openSputnik SQL schema and complete database dumps are available upon request. The source code to the openSputnik engine and core reporting architecture is being open-sourced and released to Source Forge (www.sourceforge.com).

The openSputnik group will prepare one or two releases of the clustered plant unigenes per year. Additional plant species will be included into the pipeline as they exceed our arbitrary size threshold. Additional groups of organisms will be integrated in the future with a comparative mammalian unigene database planned for spring 2005. Additional emphasis is being placed on the creation of generic reports that can distil the essence of large and heterogeneous sequence collections. Further synchronization of the completed resources with the Gene Ontology and dynamic integration and comparison of groups of species is in progress. The challenge is to stay abreast with the ever-growing collections of sequences and the novel bioinformatics methodologies that offer us the ability to better understand the nuances within our sequence collections.