Abstract:

The Global Plan towards the elimination of new HIV infections among children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive (Global Plan) was transformative, helping drive a 60% reduction in new HIV infections among children in 21 priority countries in sub-Saharan Africa from 2009 to 2015. It mobilized unprecedented political, technical, and community leadership at all levels to accelerate progress toward its ambitious targets. This progress is well documented, many specific elements of which are explained in greater detail across this JAIDS supplement. What is often less well or widely understood are the critical aspects of the Global Plan that shaped its structure and determined its impact; the factors and forces that coalesced to form a deep and diverse coalition of contributing partners committed to catalyzing change and action; and the critical lessons that the Global Plan leaves behind, a living legacy to inform and improve ongoing efforts to achieve its ultimate goals.

Key Words: global plan, leadership, partnership, impact, history

INTRODUCTION

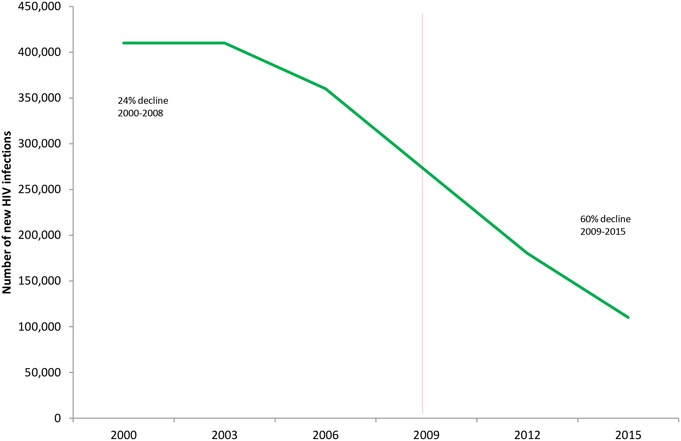

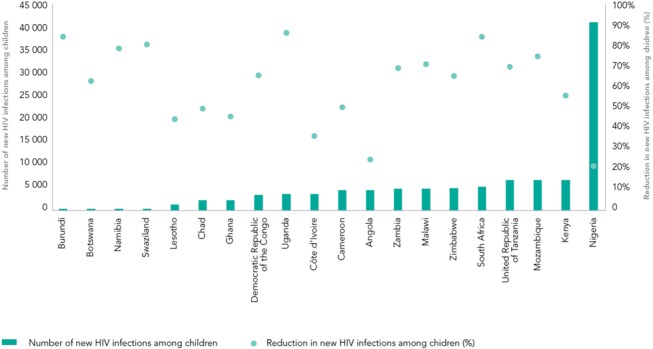

The Global Plan towards the elimination of new HIV infections among children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive (Global Plan) was transformative. It helped drive a 60% reduction (Fig. 1) in new HIV infections among children in 21 priority countries (Angola, Botswana, Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Côte d'Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, South Africa, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Swaziland, Zambia, and Zimbabwe) in sub-Saharan Africa from 2009 (the Global Plan used 2009 as a baseline year against which to measure progress) to 2015. Under the Global Plan, 1.2 million new infections among children were averted—giving these children a far better chance to survive, thrive, and fulfill their dreams. During the life of the Global Plan, the number of AIDS-related deaths among women of reproductive age was halved in these same countries. As a result of these exceptional gains, the first AIDS-free generation in more than 3 decades is now in sight, and more mothers and other women are staying healthy and alive.

FIGURE 1.

Number of new HIV infections among children in 21 Global Plan Priority countries, 2000–2015.

The tremendous progress achieved by the Global Plan is well documented (http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/GlobalPlan2016_en.pdf), specific elements of which are explained in greater detail across this supplement. What is often less well or widely understood is how the Global Plan came to be. What unique factors and forces coalesced to form such a diverse coalition of contributing partners, and in what key areas did the Global Plan catalyze change and action? Perhaps most importantly, what lessons did the Global Plan leave as a legacy, which can inform and improve ongoing efforts to achieve its ultimate goals?

In short, the Global Plan mobilized unprecedented political, technical, and community leadership at all levels to accelerate progress toward the elimination of new HIV infections among children and keeping their mothers alive. This is the Global Plan's living legacy—the final chapters of which are still being written.

THE GLOBAL PLAN'S CREATION

The Global Plan began with the simple but powerful premise that “children everywhere can be born free of HIV and their mothers remain alive” (http://files.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2011/20110609_JC2137_Global-Plan-Elimination-HIV-Children_en.pdf). Although this goal may not seem radical today, when the Global Plan was launched it seemed unimaginable. In 2009, there were 270,000 new HIV infections among children in the 21 Global Plan priority countries, over 5,000 a week. At that time, in the 21 priority countries, only 36% of pregnant women living with HIV received antiretroviral medicines (excluding the less efficacious single-dose nevirapine) for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) and 15% of children living with HIV received life-saving antiretroviral therapy. In these same countries, new HIV infections among children had declined by just 24% between 2000 and 2008. Progress was being made but not nearly fast enough, and with millions of lives at stake. In contrast, in high-income countries, HIV transmission to newborns had been essentially eliminated during the 1990s. This stark disparity created a demand that the goals of the Global Plan seek similar outcomes and futures for newborns and their mothers. In response, UNAIDS and partners prepared a Business Case to examine the feasibility of a global campaign to change the trajectory of pediatric AIDS, and set the planning in motion.

In 2010, UNAIDS Executive Director Michel Sidibé and then United States Global AIDS Coordinator Ambassador Eric Goosby jointly launched and co-chaired a high-level Global Task Team to see what could be done to accelerate global efforts. The Task Team brought together an eminent consortium of stakeholders from 25 countries and 30 partners garnered from civil society, the private sector, the faith-based community, networks of people living with HIV, and international organizations. Led by the Joint UN Programme for HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the United States President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), the Global Task Team charted a bold course for a country-led movement to create an AIDS-free generation, which would become the Global Plan.

The Global Plan towards the elimination of new HIV infections among children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive was formally launched on June 9, 2011, on the margins of the United Nations High-Level Meeting on AIDS. The global community's response to this call to action was immediate. PEPFAR announced an additional $75 million to support prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV efforts in sub-Saharan Africa, on top of the $300 million that it was already investing annually in PMTCT. Private sector partners, including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation ($40 million), Chevron ($20 million), and Johnson & Johnson ($15 million) also stepped forward with substantial pledges of their own.

WHAT MADE THE GLOBAL PLAN UNIQUE?

The Global Plan was exceptional in many ways; however, several critical aspects, in particular, shaped its structure and determined its impact:

Commitment to clear, ambitious, and time-bound targets: The Global Plan embraced the adage that “what gets measured gets done” in setting bold global targets for 2015, not only to reduce new HIV infections among children by 90% but also to halve the number of AIDS-related maternal deaths. These overarching targets were supported by sub-targets under each of the 4 prongs of PMTCT [the 4 prongs of PMTCT are to: (1) help women of reproductive age avoid HIV infection; (2) help women living with HIV avoid unintended pregnancies; (3) prevent HIV transmission from mothers to their infants using antiretroviral medicines; and (4) provide continuous care and treatment for women and mothers, their partners, and their children living with HIV].

Concentration on the highest-burden countries: The Global Plan set global targets, but it focused intensively on 21 priority countries, which at the time were home to nearly 90% of pregnant women with HIV in need of services worldwide. Without significant progress in this subset of countries, the global goals would remain out of reach.

Country ownership: From the outset, the Global Plan was grounded in country ownership at all levels, which ensured the buy-in required to drive and sustain accelerated progress.

Built-in governance and accountability structures: The Global Plan was created with clear accountability and governance structures. These included annual accountability meetings at the level of Ministers of Health from across the 21 priority countries, at which time progress data and key gaps were presented and ultimately published in the form of an Annual Progress Report.

Dual focus on political leadership and technical assistance: Recognizing the critical importance of, and interplay between, political leadership and technical assistance, the Global Plan used 2 independent but coordinated structures to advance progress in these 2 domains. The Global Steering Group (GSG) convened regularly to drive progress in the areas of political leadership, advocacy, and policy. The Global Plan worked with and through the Interagency Task Team on the Prevention and Treatment of HIV Infection in Pregnancy Women, Mothers, and Children (IATT) to ensure that priority countries received timely and effective technical capacity-building, training, and support. The IATT is cochaired by the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and was a member of the GSG to facilitate regular communication and coordination between these 2 structures.

Multisectoral engagement and mobilization: The Global Plan embraced the key concept that progress toward its goals was dependent on multisectoral engagement and mobilization at all levels. No single sector could accelerate action alone; it would take multiple forces pulling in a coordinated and collaborative fashion to get the job done. Therefore, the GSG membership included senior representatives from bilateral donors, multilateral institutions, networks of women living with HIV, the faith-based community, implementing partners, and the private sector—all of which had essential roles to play.

Centrality of mothers, and other women, living with HIV: The Global Plan strongly affirmed that mothers and other women living with HIV are integral to an effective response to the epidemic. The Global Plan stood with and for women living with HIV and was committed to ensure that all efforts to support them are informed by and developed with them.

The Global Plan was also guided by 4 overarching principles: (1) women living with HIV should be at the center of the response; (2) countries must own and lead their national response; (3) much more can be achieved through synergies, linkages, and integration than in any single area alone; and (4) everyone shares responsibility for the overall goals, but individual entities are specifically accountable for doing their part, with partner countries in the lead.

THE GLOBAL PLAN ACHIEVED REMARKABLE RESULTS

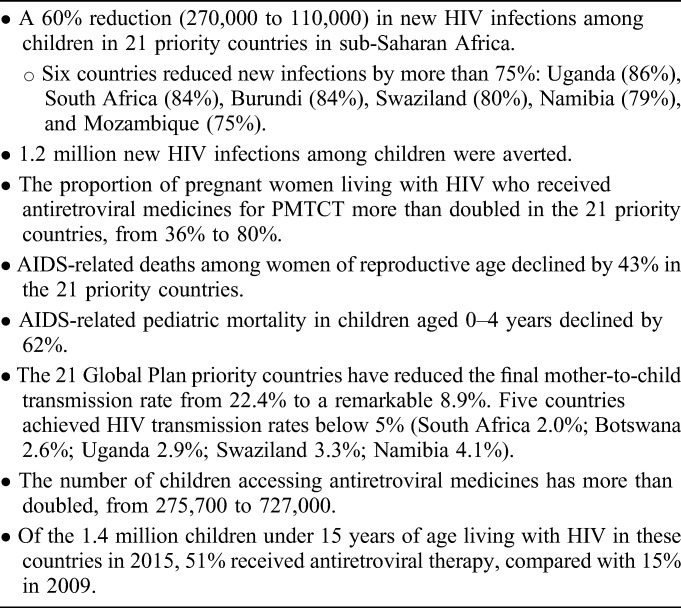

The Global Plan achieved remarkable results (Table 1 and Fig. 2). It galvanized political leadership at all levels around its goals. Heads of State, First Ladies, Ministers, and other leaders took up the mantle of the Global Plan, demanding and driving progress for women, children, and mothers in their own countries. This leadership gave greater visibility to the importance of pregnant women getting tested for HIV, and the opportunity for those who tested HIV-positive to receive treatment for their own health and that of their baby. Leadership also drove policy change and, in some countries, increased domestic resource mobilization targeted to achieving the Global Plan goals.

TABLE 1.

Impact of the Global Plan (2009 vs. 2015)

FIGURE 2.

Number of new HIV infections among children in 2015 and percentage reduction in new HIV infections since 2009, by country.

The Global Plan drove policy innovation and adoption. It rapidly accelerated momentum around country-level adoption of Option B and Option B+. It encouraged countries to implement task-shifting, more optimally using their existing health personnel in the delivery of HIV prevention and treatment services. It advanced efforts on early infant diagnosis, including the development and distribution of point-of-care assays, so that more children living with HIV could be identified and treated. It motivated the development of better pediatric formulations especially for the youngest babies and supported space for industry and partners to explore solutions. These efforts paid off; for example, in 2015, a new and more palatable antiretroviral pellet for infants was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and is now on the market. It supported countries to strengthen their translation of data into better policies and, ultimately, more efficient and effective programs. Reporting systems were streamlined and combined for improved follow-up to better knit existing systems for maternal/child health care with HIV services. It improved efforts across the PMTCT cascade, revealing and filling key gaps and better targeting responses that enhanced the delivery of care.

The Global Plan demonstrated the power of a multisectoral response. This included leveraging the private sector in the areas of management training—such as through embedding talented staff support with national, state, provincial, and district health government officials—and in harnessing the private sector's expertise and experience to improve health outcomes. The Global Plan was also a catalyst for and an example of purposeful integration, showing what is possible when HIV prevention and treatment is strategically knit into the existing maternal and child health care system.

In addition, the Global Plan helped spur momentum around validation of elimination of new HIV infections among children, as countries both within and outside the 22 Global Plan priority countries now gain recognition for achieving these key milestones. In 2015, Cuba became the first country to receive WHO certification for having ended mother-to-child transmission of HIV. In a broader sense, the Global Plan advanced progress toward reaching 3 of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs 4, 5, and 6) and the United Nations Secretary-General's Global Strategy for Women's and Children's Health as well as helping lay the groundwork for the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals.

WHAT WORK REMAINS TO BE DONE?

The Global Plan supported remarkable progress, but much work remains to be done. Although new HIV infections among children declined by 60% in the 21 Global Plan priority countries, 110,000 new HIV infections occurred in the 21 there 2015—and 150,000 globally.

An important area for intensified focus is primary prevention of new HIV infections among women of childbearing age. New HIV infections among women of childbearing age in the 21 priority countries decreased by only 5% over the same period. Between 2009 and 2015, a total of 4.5 million women of childbearing age in the 21 reporting priority countries were newly infected with HIV. In 2015 alone, 390,000 adolescent girls and young women were newly infected with HIV and 75% of new HIV infections among adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa occurred among girls. This is particularly alarming, as the population of young women in sub-Saharan Africa is increasing to more than 200 million by the year 2020, doubling the number in 1990.

The Global Plan aimed to eliminate unmet need for family planning among all women, including women living with HIV, in the priority countries. The most recent population-based surveys, however, show that while some countries (notably Malawi, Swaziland, and Zimbabwe) have made noticeable improvements in their efforts to provide family planning services, 11 of the 21 priority countries do not meet the need for family planning for 20% or more of married women.

The proportion of pregnant women living with HIV who received antiretroviral medicines for PMTCT more than doubled (from 36% to 80%) in the 21 priority countries, and 93% of them were accessing lifelong antiretroviral therapy (up from 10% in 2009). The percentage of children aged 0–14 years who received lifelong treatment jumped from 15% in 2009 to 51% in 2015. These improvements greatly contributed to the 46% decline in AIDS-related deaths among women of reproductive age and the 62% decline in AIDS-related deaths among children (aged 0–4 years) over the lifespan of the Global Plan. Yet, there remain critical gaps here to bridge, particularly for children who are still often identified too late in their disease progression.

WHAT ARE THE GLOBAL PLAN'S LESSONS FOR THE FUTURE?

Adopt a focused approach: clarity on purpose, goals, and targets facilitates better understanding and generates momentum around concrete objectives.

Political leadership at all levels matters: ownership and buy-in are essential to mobilize and sustain an agenda for change.

The power of setting clear, ambitious targets with built-in accountability structures: continual tracking of progress shows what is working and what is not, allowing for both public accountability and programmatic improvement.

Communities and people living with HIV (particularly women living with HIV) must be engaged early, often, and meaningfully in service delivery: nothing for them should be done without them, as they are an indispensable voice on what works, what is not working, and how to improve it.

Increased attention and action is needed on primary prevention, particularly for adolescent girls and young women: in sub-Saharan Africa, adolescent girls and young women are up to 14 times more likely to contract HIV/AIDS than young men, highlighting the urgency of addressing the factors related to their HIV risk, including by increasing access to secondary education, reducing gender-based violence, and changing community norms and structures that may make it difficult for young women to thrive.

There is need for concerted effort to help pregnant and breastfeeding women who test HIV-negative to remain negative. Many programs have clear protocols to help women who test positive, but fall short for those who test negative. Women remain at risk for seroconversion during this period, increasing the risk of transmission to their infant; this hightlights the value of repeat testing.

Many children living with HIV and adolescents are still being left behind. There is a need for greater focus on active case-finding to reach children in need of treatment and tailored approaches to identify and support adolescents who are not seeking or staying in care systems created for adults or children.

PMTCT progress has been impressive, but the gains are fragile and many countries are lagging behind: there were 150,000 new infections among children in 2015. This is no time to rest on our laurels.

Men matter too: male engagement has a critical impact on health outcomes for men, women, and children >, and the context of how care is provided can be as important as the content in achieving optimal outcomes. This is especially important in identifying serodiscordant couples so that treatment can start quickly.

Optimize all available opportunities for service delivery: this includes offering an HIV test to women of reproductive health age (rather than waiting for them to become pregnant), follow-up care for infants at immunization clinics for early infant diagnosis, and smart integration of services.

The job is not yet done: attention and investment must be sustained as long as women of childbearing age are living with HIV. This is critical to controlling and ultimately ending the epidemic by 2030.

Launched at the 2016 United Nations General Assembly High-Level Meeting on Ending AIDS (and co-chaired by UNAIDS and PEPFAR), the Start Free Stay Free AIDS Free Super Fast-Track framework provides a vehicle to carry forward the important and unfinished business of the Global Plan. It unites partners across various sectors around accelerating progress toward ending new HIV infections among children, finding and treating children, adolescents, and mothers living with HIV and preventing the cycle of new HIV infections among adolescents and young women, including by setting ambitious targets for 2018 and 2020.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks is due to the Global Plan Steering Group member organizations: Born Free Africa, Caritas Internationalis, Children's Investment Fund Foundation, Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation, International Community of Women Living with HIV, Johnson & Johnson, MAC AIDS Fund, Mothers2Mothers, World Health Organization, UNICEF, and United Nations Populations Fund. The success of the Global Plan could not have been achieved without the 22 priority countries, who worked tirelessly to improve services for women and children and provide the care needed. We thank the committed country and community leadership, dedicated health care providers and the many women who were determined to protect their children from HIV and obtain treatment for those who acquired HIV.

Footnotes

The authors have no funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.

The views and opinions expressed in the article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the U. S. Government.