Abstract

The Inparanoid eukaryotic ortholog database (http://inparanoid.cgb.ki.se/) is a collection of pairwise ortholog groups between 17 whole genomes; Anopheles gambiae, Caenorhabditis briggsae, Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila melanogaster, Danio rerio, Takifugu rubripes, Gallus gallus, Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, Pan troglodytes, Rattus norvegicus, Oryza sativa, Plasmodium falciparum, Arabidopsis thaliana, Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Complete proteomes for these genomes were derived from Ensembl and UniProt and compared pairwise using Blast, followed by a clustering step using the Inparanoid program. An Inparanoid cluster is seeded by a reciprocally best-matching ortholog pair, around which inparalogs (should they exist) are gathered independently, while outparalogs are excluded. The ortholog clusters can be searched on the website using Ensembl gene/protein or UniProt identifiers, annotation text or by Blast alignment against our protein datasets. The entire dataset can be downloaded, as can the Inparanoid program itself.

INTRODUCTION

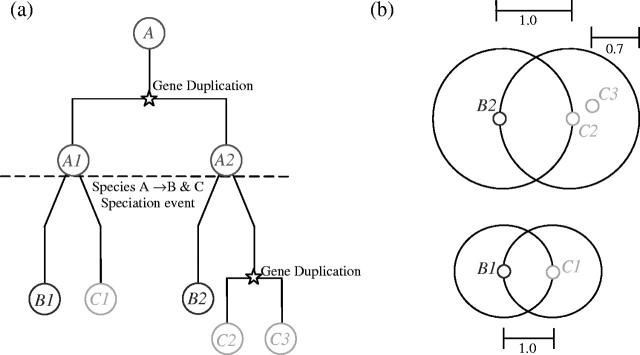

The Inparanoid program was developed specifically to identify clusters of true orthologs while avoiding inclusion of closely related but non-orthologous proteins (1). Homologs which originate following gene duplications are called paralogs, a term in biology often mistakenly thought to apply to homologs within a genome. Paralogy can exist between genes in different species, since gene duplication events occur both before and after speciation. Thus, the term ‘inparalogs’ indicate paralogs that arose through a gene duplication event after speciation, while ‘outparalogs’ arise following a gene duplication preceding speciation (1–3). Outparalogs can never be orthologs, while inparalogs can form a group of genes that together are orthologous to a gene in another species. It is therefore important to distinguish between the two. Clustering inparalogs together allows proper identification of both one-to-one and many-to-many orthology cases (Figure 1). More in-depth information on this subject, the Inparanoid program and its applications has been published previously (1,2).

Figure 1.

A hypothetical gene tree and the resulting Inparanoid clusters are shown to illustrate inparalog (and thus co-ortholog) and outparalog assignments. (a) Protein A in an ancestral species ‘A’ undergoes a gene duplication. A speciation event occurs which gives rise to the two lineages leading to species ‘B’ and ‘C’. In the C genome the genes C2 and C3 are inparalogs since their gene duplication occurred after speciation; they are co-orthologous to the B2 gene (one common ancestral protein upon speciation). B1 is an outparalog of the C2 and C3 genes, as are B1 of B2 (duplication and divergence prior to speciation). (b) B2 and C2 are the original seed-ortholog pair (all inparalogs are clustered around this pair), thus both receiving an inparalog score of 1.0. Other inparalogs (in this case C3) are scored according to their relative similarity to the seed-inparalog (here C2). Inparalog score of C3 = (Blast[C2:C3]−Blast[C2:B2])/(Blast[C2:C2]−Blast[C2:B2]) where Blast[X:Y] is the averaged blast score between X and Y in bits. In this case C2 is relatively more similar to B2 than C3 is, and thus C3 receives a lower inparalog score (0.7). C1 and B1 are orthologous to each other but are outparalogs of the other cluster and thus form a cluster of their own.

Here, we present a new release and a new online database for Inparanoid. The original release was based entirely on Swiss-Prot-TrEMBL (4) (now called UniProt) due to the quality and quantity of information-curation for these entries (1). In this release, however, we use Ensembl translation datasets as the main backbone of datasets. This is due to the rapid release and curation of whole genomes/proteomes through the Ensembl pipeline (5), and the better redundancy control. The current database contains all 16 completely sequenced eukaryotic genomes and Escherichia coli. For users preferring UniProt, we also provide a UniProt-only section that contains six eukaryotic genomes and E.coli.

Algorithmically, only minor changes have been made. As in previous releases we run Blast to compare all species against all, and feed the result to the Inparanoid program, which generates clusters of orthologs. The new website contains the entire old browse and search mechanisms, i.e. by gene/protein identifiers and Blast searching. New features include better layout and download capability of each ortholog group as FASTA sequences or as a multiple alignment for further analysis.

DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION

Ensembl-based datasets

The translated peptide sequences of all predicted transcripts, including splice variants, were obtained from the Ensembl resource (5). Peptide data were obtained for Anopheles gambiae (15 802 transcripts), Caenorhabditis briggsae (14 713 transcripts), Caenorhabditis elegans (22 215 transcripts), Drosophila melanogaster (18 289 transcripts), Danio rerio (30 783 transcripts), Takifugu rubripes (33 003 transcripts), Gallus gallus (28 416 transcripts), Homo sapiens (34 091 transcripts), Mus musculus (32 281 transcripts), Pan troglodytes (38 822 transcripts) and Rattus norvegicus (28 545 transcripts). Owing to the competitive nature of Inparanoid clustering, long and short transcripts from the same gene can end up in different clusters if they exist in more than one species. Thus, only the longest transcript from each gene was used. The number of genes/proteins can be seen in Table 1. Gene names were obtained from informative Ensembl entry descriptions. Entries lacking adequate descriptions were named using either a corresponding UniProt entry description, an external database name or an Ensembl family name, in that order of preference. In addition, peptide data were obtained from the relevant resources for Oryza sativa (6) and Plasmodium falciparum (7). The Arabidopsis thaliana, E.coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe sequences that were used in this section were obtained from UniProt (8) as described below.

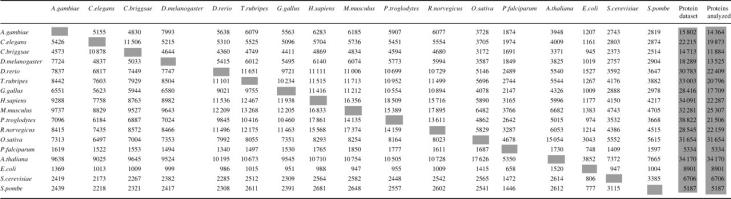

Table 1. Total number of orthologs in Inparanoid.

The number of orthologs in an organism (y-axis) when clustered with another genome (x-axis) is shown. Thus, 5623 G.gallus genes have orthologs in C.elegans, which are orthologous to a total of 5096 C.elegans genes. ‘Protein dataset’ indicates the total translation/protein set obtained. ‘Proteins analyzed’ indicates the number of proteins (for Ensembl entries indicates number of genes) used in Inparanoid clustering.

‘UniProt-only’ datasets

The complete protein sequence database from UniProt was obtained from ftp.ebi.ac.uk (8). Relevant organisms were extracted according to the taxonomy ID number and converted into multiple-FASTA format using the SWISS module of the BIOPERL package (9). In a step aimed at reducing the redundancy observed between TrEMBL and Swiss-Prot, all proteins with 100% matches to other proteins over the full length were removed, with preference shown to Swiss-Prot entries. TrEMBL proteins with 99–100% matches were removed only if the protein name matched the Swiss-Prot entry or if they were fragment sequences. It should be mentioned that this is a reduced dataset and protein duplicates exist, but lowering the match cutoff would result in inparalog deletion. The dataset size for each organism used in this study following this processing step was; A.thaliana (34 170), E.coli (8901), C.elegans (20 627), H.sapiens (36 379), S.cerevisiae (6706), S.pombe (5187), M.musculus (34 499) and D.melanogaster (18 932).

Inparanoid clustering

Whole genome NCBI Blast (10) comparisons using these datasets were performed between each pair of species. The Blast output (organism A → organism B, organism B → organism A, organism A → organism A and organism B → organism B) was used as the input for the Inparanoid program as described previously (1). The SQL table and HTML output from these 136 Inparanoid all-against-all pairwise analyses (157 including ‘UniProt-only’ analyses) make up the dataset of the present web database.

INPARANOID DATABASE CONTENT

A summary of the data in Inparanoid is shown in Table 1. This table shows the organism of interest on the left and the organism with which it is being clustered across the top. One should take note that this is not a symmetrical table, since more duplications could have occurred since speciation in organism ‘A’ when compared to organism ‘B’ and thus the number of ‘A’ genes that have orthologs in organism ‘B’ can differ substantially to the number of ‘B’ genes that have orthologs in organism ‘A’.

The sizes of clusters were found to be smaller in the Ensembl datasets compared to previous Inparanoid versions, i.e. those based on UniProt-only (and where no duplicates were removed). In addition, there is also more redundancy in the ‘UniProt-only’ datasets than in Ensembl. For example, in the previous version of Inparanoid (version 2.5; no UniProt duplicate removal), there were on average 2.75 human inparalogs per ortholog group when comparing to D.melanogaster. In the present versions this number is reduced to 1.64, and in the Uniprot-only dataset to 2.44. Previously, using UniProt, there was no robust way to confirm if two entries belonged to the same gene, i.e. if they were isoforms or allele variants. The use of Ensembl entries solves this problem, since Ensembl is a DNA sequence-based database and thus all protein and transcript information has a corresponding gene. The lowest average cluster size in Inparanoid was seen in comparisons between the H.sapiens and P.troglodytes datasets (2.04 chimpanzee and human genes/cluster) and the C.briggsae and C.elegans datasets (2.10 worm genes/cluster). A clear trend seen was that the larger the evolutionary distance, the larger the average cluster size (data not shown).

The datasets which were generated in-house are also supplemented by annotation data from both UniProt and Ensembl. Gene/protein identifiers, other external identifiers and full names/descriptions of each gene are used in the text search tool, as well as information pertaining to the source of a protein's annotation, e.g. in cases where an Ensembl translation derives its name from similarity to a UniProt entry.

WEB INTERFACE

The Inparanoid online database http://inparanoid.cgb.ki.se is organized into two main areas: Ensembl and UniProt. Since the focus of this web tool is to provide an ortholog resource for newly released genomes of interest, our focus has shifted toward Ensembl. The ‘UniProt-only’ section is maintained for those who wish to continue using Inparanoid with exclusively Uniprot proteins, since not all UniProt protein entries are annotated/linked to entries in Ensembl (especially those derived from TrEMBL). It is completely independent of the main Ensembl-based dataset and depending on usage-loads, it may be removed altogether in the future. Its tools are very similar to the main section of Inparanoid, differing mainly in format. Thus, it will not be discussed further here.

The database can be accessed in several ways. The first section, ‘Human vs All’ allows the user to select an organism to display all Inparanoid clusters between it and human. The dataset being displayed is quite large and therefore it may take a few moments to load. The second section ‘All species vs All’ is similar except that one can freely choose which two organisms to pick. As on date, there is no difference in the datasets accessed by these two tools, but it is planned to include many more organisms in the ‘Human vs All’ tool to allow a greater flexibility in scaling up the Inparanoid database to include scores of organisms as they become available.

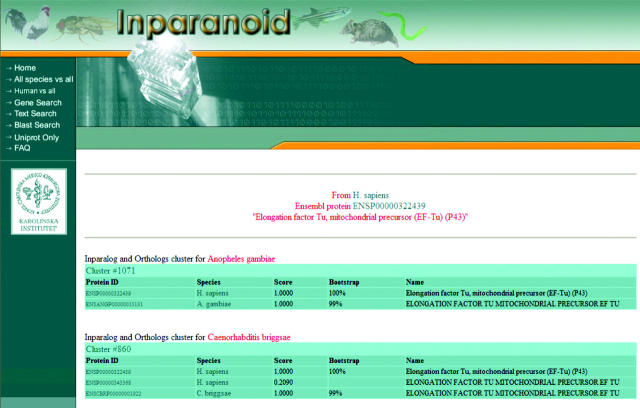

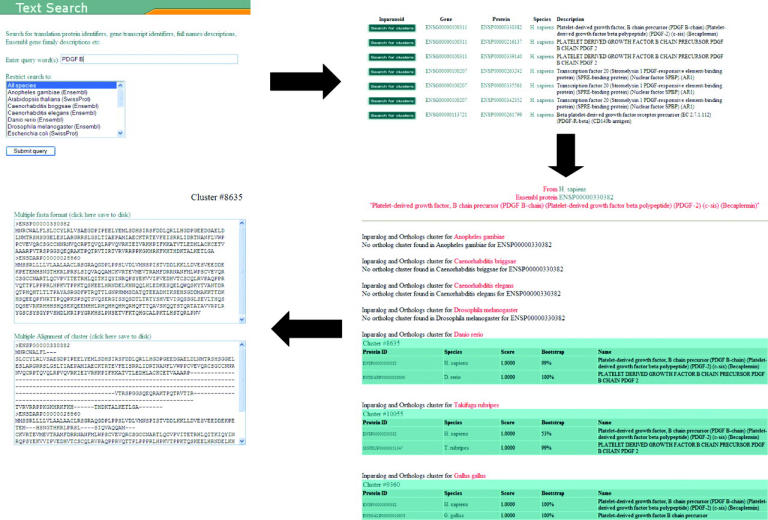

The next three tools take a different approach as they first identify a gene before proceeding to see whether it has orthologs in other organisms. ‘Gene Search’ requires an identifier from Ensembl, Flybase, Uniprot, a locus identifier for the rice genome or an accession number for plasmodium cDNA libraries to select a gene in an organism of choosing. The Inparanoid score cutoff can be raised to exclude borderline inparalog cases (outparalogs are automatically excluded from clusters by the Inparanoid program). A sample output can be seen in Figure 2. Each table represents a separate Inparanoid cluster, which are genes thought to derive from a single ancestral gene at the speciation. ‘Text search’ is a more flexible search which first outputs a list of genes whose annotation matches the query text string. Clicking on the ‘Search for Clusters’ icon then queries the Inparanoid database for ortholog clusters in all organisms (Figure 3). The figure also demonstrates that one can obtain a multiple FASTA file and a multiple alignment generated using Kalign, a rapid multiple-alignment generator developed in-house (T. Lassmann and E.L.L. Sonnhammer, manuscript in preperation) This last feature is useful to verify the correctness of the cluster that Inparanoid has generated. The last tool ‘Blast Search’ allows one to enter a sequence to Blast against the protein datasets used in the creation of this database. The output provides a list of best-hits; as before, clicking on the ‘Search for Clusters’ icon queries the database for clusters.

Figure 2.

An Inparanoid cluster is a representation of genes thought to share a single ancestral gene upon speciation. In this example output only human–mosquito and human–worm clusters are shown. In the human–worm cluster, the two human genes are inparalogs, i.e. resulted from a gene duplication after the speciation from worm occurred. They are thus both co-orthologous to the worm gene. The Inparanoid score is a measure of how similar an inparalog is to the inparalog that is the main ortholog. If they are identical the score is 1.0, but as the similarity drops towards the similarity of the main orthologs, the score goes to 0.0 (see Figure 1). For example, ENSP00000343386 is less similar to the C.briggsae gene than is ENSP00000322439, but both these human genes are still co-orthologous to it. The bootstrapping score is a measure of how reliably that gene is the main ortholog. Gene and protein identifiers are hyperlinks to the relevant databases for each species.

Figure 3.

Using a gene name as a search generates a list of possible gene hits. Clicking on the ‘Search for Clusters’ icon queries the database as to whether a gene occurs in an Inparanoid-cluster in all organisms. Clicking on the cluster name generates a multiple FASTA file for this cluster and performs a multiple alignment using the Kalign program. These can be used to check the validity of the cluster in question and can be saved to disk.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The Inparanoid program and all other required resources are available for download and can be run locally. In addition to the data which is available for search/browse using the web interface, FASTA files containing all proteins, protein description files, SQL tables and HTML output from each pairwise Inparanoid analysis are available for download.

FURTHER DEVELOPMENTS

We plan to update Inparanoid on a quarterly basis. As mentioned above, the most pertinent update is to increase the number of organisms analyzed. As the rate at which new genomes become sequenced increases, it remains difficult to maintain the ‘All vs All’ approach for all organisms as this would soon render each Inparanoid update an impossibly large task. Thus, the more manageable ‘Human vs All’ section is expected to be the main update target, with the possibility of including additional sections, e.g. ‘Mouse vs All’, depending on demand. A visualization tool that can show ortholog clusters together with closely related outparalogs may be useful for examining the broader evolutionary histories of genes and their orthologs and is under consideration.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was funded by grants from the Swedish research council, Karolinska Institutet and Pfizer Corporation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Remm M., Storm,C.E. and Sonnhammer,E.L. (2001) Automatic clustering of orthologs and in-paralogs from pairwise species comparisons. J. Mol. Biol., 314, 1041–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Brien K.P., Westerlund,I. and Sonnhammer,E.L. (2004) OrthoDisease: a database of human disease orthologs. Hum. Mutat., 24, 112–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sonnhammer E.L. and Koonin,E.V. (2002) Orthology, paralogy and proposed classification for paralog subtypes. Trends Genet., 18, 619–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boeckmann B., Bairoch,A., Apweiler,R., Blatter,M.C., Estreicher,A., Gasteiger,E., Martin,M.J., Michoud,K., O'Donovan,C., Phan,I. et al. (2003) The Swiss-Prot protein knowledgebase and its supplement TrEMBL in 2003. Nucleic Acids Res., 31, 365–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birney E., Andrews,D., Bevan,P., Caccamo,M., Cameron,G., Chen,Y., Clarke,L., Coates,G., Cox,T., Cuff,J. et al. (2004) Ensembl 2004. Nucleic Acids Res., 32, D468–D470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuan Q., Ouyang,S., Liu,J., Suh,B., Cheung,F., Sultana,R., Lee,D., Quackenbush,J. and Buell,C.R. (2003) The TIGR rice genome annotation resource: annotating the rice genome and creating resources for plant biologists. Nucleic Acids Res., 31, 229–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner M.J., Hall,N., Fung,E., White,O., Berriman,M., Hyman,R.W., Carlton,J.M., Pain,A., Nelson,K.E., Bowman,S. et al. (2002) Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nature, 419, 498–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apweiler R., Bairoch,A., Wu,C.H., Barker,W.C., Boeckmann,B., Ferro,S., Gasteiger,E., Huang,H., Lopez,R., Magrane,M. et al. (2004) UniProt: the Universal Protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res., 32 (Database issue), D115–D119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stajich J.E., Block,D., Boulez,K., Brenner,S.E., Chervitz,S.A., Dagdigian,C., Fuellen,G., Gilbert,J.G., Korf,I., Lapp,H. et al. (2002) The Bioperl toolkit: Perl modules for the life sciences. Genome Res., 12, 1611–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altschul S.F., Madden,T.L., Schaffer,A.A., Zhang,J., Zhang,Z., Miller,W. and Lipman,D.J. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The Inparanoid program and all other required resources are available for download and can be run locally. In addition to the data which is available for search/browse using the web interface, FASTA files containing all proteins, protein description files, SQL tables and HTML output from each pairwise Inparanoid analysis are available for download.