Abstract

Owing to the high costs involved, only 28 eukaryotic genomes have been fully sequenced to date. On the other hand, an increasing number of projects have been initiated to generate survey sequence data for a large number of other eukaryotic organisms. For the most part, these data are poorly organized and difficult to analyse. Here, we present PartiGeneDB (http://www.partigenedb.org), a publicly available database resource, which collates and processes these sequence datasets on a species-specific basis to form non-redundant sets of gene objects—which we term partial genomes. Users may query the database to identify particular genes of interest either on the basis of sequence similarity or via the use of simple text searches for specific patterns of BLAST annotation. Alternatively, users can examine entire partial genome datasets on the basis of relative expression of gene objects or by the use of an interactive Java-based tool (SimiTri), which displays sequence similarity relationships for a large number of sequence objects in a single graphic. PartiGeneDB facilitates regular incremental updates of new sequence datasets associated with both new and exisitng species. PartiGeneDB currently contains the assembled partial genomes derived from 1.83 million sequences associated with 247 different eukaryotes.

INTRODUCTION

To date, the genome sequence for over 220 different species has been generated (1). However, owing to the cost of sequencing and their relatively large size, the full genome sequence of only 28 eukaryotes are currently available. Comparative analyses exploring genetic and biochemical diversity within a phylogenetic framework (‘phylogenomics’) are currently limited by the narrow range of phyla associated with these species. On the other hand, an increasing number of projects have been initiated to generate survey sequence data for a large number of other eukaryotic organisms. Such data consist of many thousands of short (usually ∼300–500 bp), single-pass sequence reads from either mRNA/cDNA [expressed sequence tags (ESTs)] or genomic DNA [genome survey sequences (GSSs)]. There are currently over 290 species from a variety of different taxonomic groups for which more than 1000 ESTs have been generated. Typically, the aims of these projects has either been to identify ‘interesting’ genes associated with a particular species or to aid the mapping of the genome prior to full genome sequencing (2–6).

In general, the poorly organized nature of these data makes them difficult to interpret within a genomic context and precludes even simple comparative analyses. Common problems include significant redundancy in the datasets (some genes may have been sequenced multiple times) and a lack of consistent annotation between projects. An effective way to overcome these problems is to group ESTs into clusters (representing unique genes), which may be subsequently fed into downstream annotation pipelines. Since ESTs provide only a fraction of the available genes for a particular organism, we refer to these analysed datasets as partial genomes. Informatic solutions to produce partial genomes or ‘gene indices’ have been developed by several different groups (7–13), the analysis of which has tended to involve either complex integrated database solutions and/or a large amount of manual sequence annotation, both of which require a considerable investment in bioinformatic resources, and make cross-species and between-lab integration difficult.

Previously, we have developed a series of tools (termed PartiGene) which can take EST data and identify non-redundant sets of genes associated with each species (14–16). Here, we present PartiGeneDB (http://www.partigenedb.org), a single unified database system that collates the partial genomes for all species (excluding those for which a full genome sequence is available) for which a significant amount (>1000 sequences) of EST data exists. PartiGeneDB not only allows an exploration of the genetic and biochemical diversity associated with these organisms but also facilitates comparative analyses between different groups of organisms allowing the identification of common and/or group-specific traits.

CONSTRUCTION OF THE DATABASE

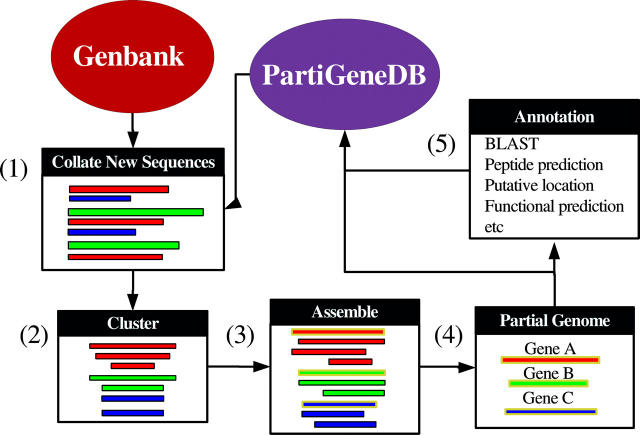

Figure 1 shows a schematic representation of the process used to generate PartiGeneDB. The process begins with the identification of organisms in GenBank for which >1000 ESTs exist. For each such organism, the current number of ESTs is compared with the number of sequences in PartiGeneDB. If a significant number of new sequences are available or the organism is new to the database, they are downloaded and screened for the presence of contaminating vector sequence and poly(dA) tails [1]. These screened sequences are then clustered [2] on the basis of sequence similarity using our in-house clustering software—CLOBB (14). This clustering step is incremental such that, during subsequent rounds of clustering, the original cluster identifiers associated with each organism remains intact. This enables PartiGeneDB to be updated easily and ensures that analyses are consistent between such updates. Once the clusters have been generated, constituent sequences are assembled to form consensus sequences (representing putative genes) using the publicly available software tool—PHRAP [3]. This set of non-redundant consensus sequences forms the partial genome of the organism [4]. At this stage, the sequence and cluster data are uploaded into the PartiGeneDB and the process moves onto analysis of the next identified organism.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the process used to build PartiGeneDB (for further details see text).

Having created the initial sequence database, a series of BLAST searches are performed against the non-redundant protein database to derive simple annotation for the non-redundant sets of putative gene sequences [5]. In addition, a series of BLASTs are performed in which each partial genome dataset is compared to every other partial genome dataset. The results from this are used in the creation of the sequence similarity profiles viewed using the SimiTri tool (see later). In addition to sequence and BLAST annotation information, PartiGeneDB also includes taxonomic information obtained from the NCBI's taxonomy web resource. This allows PartiGeneDB to group organisms on the basis of taxonomic relatedness facilitating retreival of genes from organisms associated with a common taxa (see later). As on July 27, 2004, PartiGeneDB contains 1 835 483 sequences derived from 1366 cDNA libraries associated with 247 species (see Table 1).

Table 1. Species, sequences and number of cDNA libraries from PartiGeneDB as on July 2004.

| Taxon | Species | Sequences | Number of libraries |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alveolates | 14 | 150 701 | 61 |

| Euglenozoa | 4 | 11 836 | 24 |

| Other protists | 5 | 64 033 | 51 |

| Fungi | 30 | 197 906 | 97 |

| Plants | 97 | 671 811 | 459 |

| Cnidaria | 2 | 6153 | 5 |

| Nematodes | 34 | 281 558 | 189 |

| Arthropods | 24 | 152 562 | 209 |

| Other protostomes | 8 | 39 057 | 60 |

| Chordates | 28 | 257 424 | 210 |

| Echinoderms | 1 | 2442 | 1 |

| Total | 247 | 1 835 483 | 1366 |

Species are grouped into arbitrary groups on the basis of taxonomic information derived from the National Center for Biotechnology Information's taxonomy browser (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/taxonomyhome.html/).

ACCESSING PartiGeneDB

To allow access to the PartiGeneDB by remote users, we have developed a series of web-based forms that allow the database to be interrogated by several methods. These are as follows.

View entire species datasets

By selecting an individual organism, the user may view its associated partial genome consisting of a list of its genes ordered by their relative abundance together with a brief summary of any annotation obtained from the BLAST search of the sequence against the protein non-redundant database. This facility is especially useful as an overview of the most commonly expressed genes associated with the cDNA libraries used to generate the sequences for a particular organism.

Patterns of annotation

Where a user is interested in searching the database for homologs of a known gene, they may search PartiGeneDB using simple text queries. In this mode, the user is prompted to select one or more species and enter some text to search against the BLAST annotation to retrieve clusters of interest. This provides a quick method of identifying homologous genes from a particular taxonomic group (e.g. list all genes in chordates which have homology to ‘spectrin’).

Sequence similarity

In a similar vein, users may also search for genes that share sequence similarity to a gene of interest. Searching by sequence similarity presents the user with a typical BLAST search page. However, for databases, the user is offered a choice of one or more species datasets against which to perform the search. This search mode provides an additional method for identifying homologs and is of particular relevance for those genes which have previously been uncharacterized.

SimiTri

SimiTri is a tool which allows the simultaneous display of relative sequence similarity relationships between a single organism dataset with three user defined datasets (17). The user first selects a species of interest, followed by three datasets which may consist of one or more taxonomically related species. After submitting this information, the user is presented with a Java tool which shows the relative sequence similarity of each gene from the species to each of the three selected datasets. In addition, a list of genes that shared similarity to either none or one of the datasets is provided. This tool allows the user to identify genes that display atypical profiles of similarity suggesting an unusual evolutionary history.

VIEWING INDIVIDUAL CLUSTERS

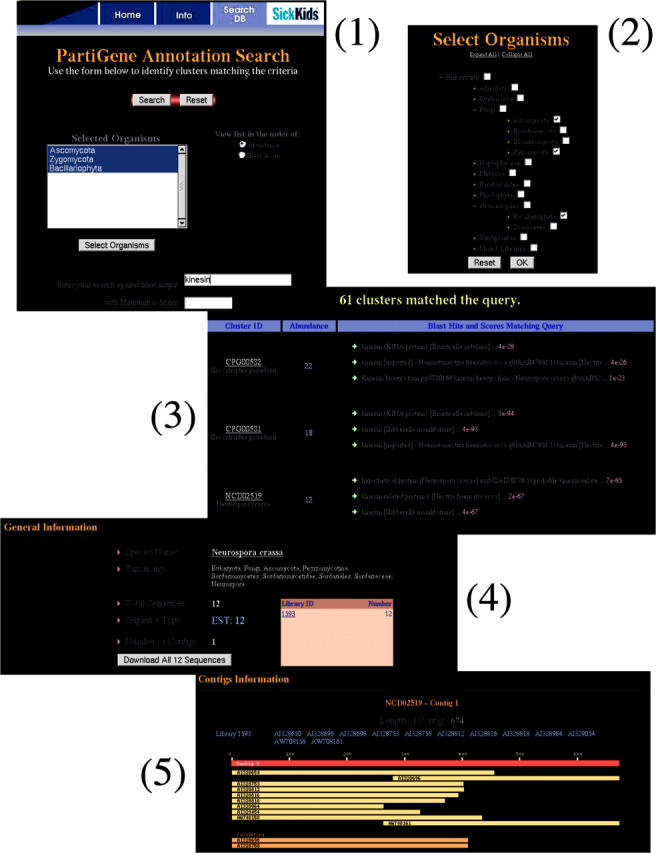

Each of the methods described above allows the user to select an individual gene and view the cluster of sequences associated with it (see Figure 2). Information provided by the cluster page include: cluster identifier; species name; number of sequences in the cluster; types of sequences in the cluster (generally ESTs, although a few organisms may have other types of sequence data incorporated); library composition of the sequences in the cluster; number of contigs (consensus sequences) built from the sequences; summaries of annotation derived from a BLAST search against the protein non-redundant database; a list of sequences associated with the cluster; a schematic detailing the relationship of each sequence with the consensus sequence and the consensus sequence itself. Each cluster page provides links to other resources including the GenBank entry for each sequence, detailed library information, sequence alignment of the individual sequences to the consensus and a button to allow the user to download all the sequences associated with a cluster.

Figure 2.

Typical screenshots of PartiGeneDB. [1] Annotation search page: users may select a species or group of species and enter some text to search for keywords in the BLAST annotation associated with clusters from that/those species. Output may be viewed in terms of relative abundance or BLAST score. [2] Taxonomic tree: users may navigate through a tree of taxonomic groups and select either individual species or groups of species on which to perform their searches. [3] Search output from a typical annotation search information presented includes cluster identifiers (with links to more detailed information for each cluster—see text), relative abundance and summaries of BLAST annotation. [4] and [5] Cluster-specific information includes number of EST, taxonomic data, library information, BLAST annotation and a detailed graphic of how each sequence relates to the cluster consensus sequence.

We are continuing to develop ways of mining the database to make the data more accessible to the user community. More information on the PartiGeneDB itself and methods of access are available on its home page (http://www.partigenedb.org).

FUTURE PLANS

In addition to the raw nucleotide sequence, we are applying a previously developed pipeline (16) to generate a peptide prediction for each putative gene sequence. These sequences will be analysed by the Interpro package (18) to identify distinct protein domains which enable Gene Ontology (19) terms to be associated with each sequence. Collation of these terms will allow us to build profiles of the molecular functions and processes associated with the partial genomes obtained for each organism. Comparative analyses of these profiles may then enable us to understand more about the biology associated with each organism or collection of organisms. Further developments include the use of the sequence similarity profiles to identify genes sharing similar profiles. This approach has been successfully applied to identify genes with related functionality (20) and will provide an additional source of annotation.

Our initial interest in PartiGeneDB is in its application to parasite biology. Parasites represent a major scourge on human health and economics, especially in the developing world. Owing to the relatively poor economies of the countries, which bear the greatest burden, drug and vaccine programs have not attracted the attention they merit. Despite this lack of investment, a large body of sequence data in the form of ESTs currently exists and continues to be generated for many of these organisms. The multiple occurrence of parasitism suggests that there are specific adaptations which enable a parasitic lifestyle. By focusing on groups of parasite and non-parasite comparators, we aim to explore the evolutionary origins of parasites, gain insights into their biology and identify parasite-specific traits.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

J.M.P.A. is supported by the Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto, Ontario, Canada) Research Training Centre. Computational analyses were performed at the Center for Computational Biology, Hospital for Sick Children.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernal A., Ear,U. and Kyrpides,N. (2001) Genomes OnLine Database (GOLD): a monitor of genome projects world-wide. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 126–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen J.E., Daub,J., Guiliano,D., McDonnell,A., Lizotte-Waniewski,M., Taylor,D.W. and Blaxter,M. (2000) Analysis of genes expressed at the infective larval stage validates utility of Litomosoides sigmodontis as a murine model for filarial vaccine development. Infect. Immun., 68, 5454–5458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaxter M., Daub,J., Guiliano,D., Parkinson,J., Whitton,C. and the Filarial Genome Project (2002) The Brugia malayi genome project: expressed sequence tags and gene discovery. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg., 96, 7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenyon F., Welsh,M., Parkinson,J., Whitton,C., Blaxter,M.L. and Knox,D.P. (2003) Expressed sequence tag survey of gene expression in the scab mite Psoroptes ovis—allergens, proteases and free-radical scavengers. Parasitology, 126, 451–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li L., Brunk,B.P., Kissinger,J.C., Pape,D., Tang,K., Cole,R.H., Martin,J., Wylie,T., Dante,M., Fogarty,S.J., Howe,D.K., Liberator,P., Diaz,C., Anderson,J., White,M., Jerome,M.E., Johnson,E.A., Radke,J.A., Stoeckert,C.J.,Jr, Waterston,R.H., Clifton,S.W., Roos,D.S. and Sibley,L.D. (2003) Gene discovery in the apicomplexa as revealed by EST sequencing and assembly of a comparative gene database. Genome Res., 13, 443–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mineta K., Nakazawa,M., Cebria,F., Ikeo,K., Agata,K. and Gojobori,T. (2003) Origin and evolutionary process of the CNS elucidated by comparative genomics analysis of planarian ESTs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 7666–7671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams M.D., Kerlavage,A.R., Fleischmann,R.D., Fuldner,R.A., Bult,C.J., Lee,N.H., Kirkness,E.F., Weinstock,K.G., Gocayne,J.D., White,O. et al. (1995) Initial assessment of human gene diversity and expression patterns based upon 83 million nucleotides of cDNA sequence. Nature, 377 (Suppl.), 3–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boguski M.S., Lowe,T.M. and Tolstoshev,C.M. (1993) dbEST—database for ‘expressed sequence tags’. Nature Genet., 4, 332–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sutton G.G., White,O., Adams,M.D. and Kerlavage,A.R. (1995) TIGR Assembler: a new tool for assembling large shotgun sequencing projects. Gen. Sci. Technol., 1, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 10.White O. and Kervalage,A.R. (1996) TDB: new databases for biological discovery. Methods Enzymol., 266, 27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christoffels A., van Gelder,A., Greyling,G., Miller,R., Hide,T. and Hide,W. (2001) STACK: Sequence Tag Alignment and Consensus Knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 234–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pertea G., Huang,X., Liang,F., Antonescu,V., Sultana,R., Karamycheva,S., Lee,Y., White,J., Cheung,F., Parvizi,B., Tsai,J. and Quackenbush,J. (2003) TIGR Gene Indices Clustering Tools (TGICL): a software system for fast clustering of large EST datasets. Bioinformatics, 19, 651–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parkinson J., Whitton,C., Schmid,R., Thomson,M. and Blaxter,M. (2004) NEMBASE—a resource for parasitic nematode ESTs. Nucleic Acids Res., 32, D427–D430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parkinson J., Guiliano,D.G. and Blaxter,M. (2002) Making sense of EST sequences by CLOBBing them. BMC Bioinformatics, 3, 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parkinson J., Mitreva,M., Hall,N., Blaxter,M. and McCarter,J. (2003) 400,000 Nematode ESTs on the Net. Trends Parasitol., 19, 283–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parkinson J., Anthony,A., Wasmuth,J., Hedley,B.A. and Blaxter,M. (2004) PartiGene—constructing partial genomes. Bioinformatics, 20, 1398–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parkinson J. and Blaxter,M. (2003) SimiTri—visualising similarity relationships for groups of sequences. Bioinformatics, 19, 390–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Apweiler R., Attwood,T.K., Bairoch,A., Bateman,A., Birney,E., Biswas,M., Bucher,P., Cerutti,L., Corpet,F., Croning,M.D.R., Durbin,R., Falquet,L., Fleischmann,W., Gouzy,J., Hermjakob,H., Hulo,N., Jonassen,I., Kahn,D., Kanapin,A., Karavidopoulou,Y., Lopez,R., Marx,B., Mulder,N.J., Oinn,T.M., Pagni,M., Servant,F., Sigrist,C.J.A. and Zdobnov,E.M. (2001) The InterPro database, an integrated documentation resource for protein families, domains and functional sites. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 37–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashburner M., Ball,C.A., Blake,J.A., Botstein,D., Butler,H., Cherry,J.M., Davis,A.P., Dolinski,K., Dwight,S.S., Eppig,J.T., Harris,M.A., Hill,D.P., Issel-Tarver,L., Kasarskis,A., Lewis,S., Matese,J.C., Richardson,J.E., Ringwald,M., Rubin,G.M. and Sherlock,G. (2000) Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nature Genet., 25, 25–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pellegrini M., Marcotte,E.M., Thompson,M.J., Eisenberg,D. and Yeates,T.O. (1999) Assigning protein functions by comparative genome analysis: protein phylogenetic profiles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 4285–4288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]