Abstract

This study examined three potential moderators of the relations between maternal parenting stress and preschoolers’ adjustment problems: a genetic polymorphism - the short allele of the serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR, ss/sl allele) gene, a physiological indicator - children’s baseline respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), and a behavioral indicator - mothers’ reports of children’s negative emotionality. A total of 108 mothers (Mage = 30.68 years, SDage = 6.06) reported on their parenting stress as well as their preschoolers’ (Mage = 3.50 years, SDage = .51, 61% boys) negative emotionality and internalizing, externalizing, and sleep problems. Results indicated that the genetic sensitivity variable functioned according to a differential susceptibility model; however, the results involving physiological and behavioral sensitivity factors were most consistent with a diathesis-stress framework. Implications for prevention and intervention efforts to counter the effects of parenting stress are discussed.

Keywords: respiratory sinus arrhythmia, 5-HTTLPR, negative emotionality, parenting stress, child adjustment

Research suggests that stress due to the demands of parenting (i.e., parenting stress, Deater-Deckard, 1998) is a common phenomenon that is experienced across racial groups and levels of socioeconomic status (Crnic, Gaze, & Hoffman, 2005; Huang, Costeines, Kaufman, & Ayala, 2014; Misri et al., 2010; Raikes & Thompson, 2005), and has particularly strong links to child maladjustment during the preschool period (e.g., Goldberg et al., 1997). Undoubtedly, the relations among parenting stress and children’s poor psychosocial functioning are transactional, with each influencing the other over time (Woodman, Mawdsley, & Hauser-Cram, 2015). To best understand these complex processes, it is important to first identify individual factors impacting the links between parenting stress and child adjustment problems. Thus, the goal of this study is to examine child characteristics that might make them more or less sensitive to the effects of parenting stress within the frameworks of diathesis-stress and differential susceptibility models.

Traditional diathesis-stress models posit that individuals with a given vulnerability factor (e.g., genetic risk), compared to individuals lacking this vulnerability factor, are more likely to experience negative outcomes as a result of exposure to adverse environmental contexts (for a review, see Zuckerman, 1999). In contrast, the differential susceptibility framework suggests that susceptibility variables render individuals more sensitive to the environment in a “for better and for worse” way (Ellis, Boyce, Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2011, p. 14). To date, research has found support for both diathesis-stress and susceptibility models, depending on the constructs involved, the methods used to assess those constructs, and the developmental period studied (e.g., Conradt, Measelle & Ablow, 2013; Kochanska, Boldt, Kim, Yoon, & Philibert, 2015; Kochanska, Kim, Barry, & Philibert, 2011; Morris et al., 2002; Obradović, Bush, Stamperdahl, Adler, & Boyce, 2010; Slagt, Dubas, Deković, & van Aken, 2016). Further, the majority of research has examined children’s sensitivity to the environment via a single construct, though some investigators have examined two constructs (e.g., Kochanska et al., 2015). No study could be identified that assessed child sensitivity at genetic, physiological, and behavioral levels. Given that the mixed support for diathesis-stress versus differential susceptibility frameworks could be due to variability in the level of analysis used in the extant literature (i.e., whether sensitivity was examined at the behavioral, physiological, or genetic level), it is important to address child sensitivity at each of these levels in the same investigation. The present study used a multi-systems, multi-method approach to study how preschoolers’ genetic (i.e., status on the serotonin transporter linked polymorphic region known as 5-HTTLPR), physiological (i.e., baseline respiratory sinus arrhythmia; RSA), and behavioral (i.e., negative emotionality) sensitivity factors interact with parenting stress to impact maternal perceptions of child adjustment across three domains: internalizing, externalizing, and sleep problems. Such research can aid in identifying children who are more or less at risk for maladjustment in the context of parenting stress, thereby benefitting prevention and intervention planning.

Genetic, Physiological, and Behavioral Sensitivity to Parenting Stress

Parenting stress arises from pressures to juggle parenting tasks with employment and other obligations (Roxburgh, 2012), as well as from variations in child and parent characteristics. For instance, parenting stress is exacerbated when caring for a child with a developmental disability or emotional or behavioral problems (Bode, George, Weist, Stephan, Lever, & Youngstrom, 2016; Merwin, Smith, & Dougherty, 2014; Woodman et al., 2015). Regardless of the sources, parenting stress likely relates to poor outcomes for children via decrements in effective parenting practices (e.g., Deater-Deckard, 1998; Morgan, Robinson, & Aldridge, 2002). Empirical work has demonstrated that children’s exposure to parenting stress can have serious, negative implications for youth development (Anthony et al., 2005; Coplan, Bowker, & Cooper, 2003; Costa, Weems, Pellerin, & Dalton, 2006; Crnic et al., 2005). For example, in a sample of preschoolers in a Head Start program, greater parenting stress was associated with poorer teacher ratings of social competence and greater internalizing and externalizing problems (Anthony et al., 2005). Importantly, outcomes of parent-focused interventions for child behavior problems are enhanced when parenting stress is addressed (Kazdin & Whitley, 2003). Because parenting stress tends to be stable over time (Koch, Ludvigsson, & Sepa, 2010), when not addressed, it is likely to have a lasting impact on child outcomes.

Given the prevalence and persistence of parenting stress and its adverse impact on effective parenting, it is important to identify factors that exacerbate risk for, and can protect against, child adjustment problems in the context of parenting stress. Despite strong theoretical and empirical support for a multi-systems approach, to our knowledge, no study has examined child sensitivity to parenting stress at the genetic, physiological, and behavioral levels in one investigation. Examining sensitivity factors at these three levels in tandem is necessary to disentangle the contributions of each factor and their relevance to diathesis-stress and differential susceptibility frameworks. Presumably, child baseline RSA and 5-HTTLPR could function according to either a diathesis-stress or a differential susceptibility framework in the context of maternal parenting stress; however, it is most likely that negative emotionality follows a diathesis-stress model.

Genetic sensitivity

The serotonin transporter gene, (SLC6A4), is an important regulatory element for serotonergic neurotransmission. The promoter region of the gene, also referred to as 5-HTTLPR, is highly polymorphic, resulting in two main variants, a short (s) 14-repeat allele and a long (l) 16-repeat allele. The short variation leads to less transcription of SLC6A4. Though the short allele of 5-HTTLPR has been a focus of research on gene-environment interactions, we did not find any research that examined interactions between 5-HTTLPR and mothers’ parenting stress. However, limited research has included parenting stress as part of life stress composites. For example, Lavigne et al. (2013) found a significant gene-environment interaction involving life stress and 5-HTTLPR. Four-year-olds with two copies of the long allele, compared to children with one or two copies of the short allele, demonstrated the greatest levels of oppositional defiant disorder symptoms when family stress was high but the lowest levels when stress was low. The findings by Lavigne et al. (2013) are in contrast to most other work examining 5-HTTLPR that suggests one- or two-copies of the short allele confer susceptibility (for a review, see Belsky & Pluess, 2009), or vulnerability (e.g., Caspi et al., 2003), to environmental contexts. In particular, the short allele of 5-HTTLPR has been found to interact with a number of environmental factors (e.g., bullying victimization, mother-child attachment style) to predict a host of adjustment problems in youth populations (e.g., emotional problems, difficulties with self-regulation; Kochanska, Philibert, & Barry 2009; Sugden, et al., 2010). In other related investigations, the short allele of 5-HTTLPR was found to increase the likelihood that youth would benefit from exposure to low-risk environments and be more susceptible to the negative effects of adverse environments (Bogdan, Agrawal, Gaffrey, Tillman, & Luby, 2014). Bogdan et al. (2014) found that preschoolers who were homozygous for the short allele of 5-HTTLPR exhibited fewer depressive symptoms than their peers with long alleles when exposed to low levels of stressful life events but demonstrated higher symptom levels in the context of greater levels of stressful life events.

Physiological sensitivity

From an evolutionary perspective, calibration of the stress response is of key importance when considering the impact of the environment on the individual (Boyce & Ellis, 2005). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), a marker of the parasympathetic nervous system’s control over heart rate, is noteworthy because of its proposed role in stress sensitivity and reactivity (Porges, 1992). Generally speaking, lower resting RSA has been linked with poor emotion regulation and psychopathology (Beauchaine, 2001; Calkins, Graziano, & Keane, 2007; Mezzacappa et al., 1997; Pine et al., 1998; Shannon, Beauchaine, Brenner, Nehaus, & Gatzke-Kopp, 2007). In contrast, higher resting RSA has been associated with adaptive outcomes, including emotion regulation and social competence (Beauchaine, 2001; Fabes, Eisenberg, & Eisenbud, 1993), and recent research has also provided evidence for the notion that higher RSA (i.e. higher vagal tone) might be a protective factor in the link between adversity and youth psychopathology (McLaughlin, Rith-Najarian, Dirks & Sheridan, 2015). Other literature suggests that child resting RSA may function differently depending on the quality of the caregiver-child relationship, such that infants with higher resting RSA have shown the lowest levels of problem behavior in positive caregiving environments and the highest levels of problem behavior in the context of negative environments (Conradt et al., 2013). These findings underscore physiology as a potential moderator of parental effects on child outcomes.

Behavioral sensitivity

In terms of behavioral sensitivity factors, some research has demonstrated that child emotion dysregulation (Scott & O’Connor, 2012) and related constructs (e.g., difficult temperament; Pluess & Belsky, 2010) confer greater sensitivity to the environment. For instance, Pluess and Belsky (2010) demonstrated that children with more difficult temperaments (e.g., greater negative emotionality, difficulties with adaptability) exhibited the highest levels of behavior problems and teacher-child conflict when childcare quality was low and the lowest scores on these two outcomes when childcare quality was high. In Kim and Kochanska (2012), infant negative emotionality moderated the link between parent-child mutuality and child self-regulation in a manner consistent with a differential susceptibility framework. Kochanska et al. (2015) examined child biobehavioral risk, which they defined as having the short allele of 5-HTTLPR and high levels of anger proneness, and found that support for diathesis-stress and differential susceptibility models varied across parenting dimensions and child outcomes. For instance, children with high biobehavioral risk exhibited the lowest levels of negative attitudes towards substance use at age 10 when they were exposed to lower levels of positive parenting from 25 to 80 months of age. However, when exposed to optimal, positive parenting environments, these high-risk children had higher levels of negative attitudes towards substance use than their low-risk peers, consistent with a differential susceptibility framework. All other interactions involving parenting variables (both positive and negative) and biobehavioral risk followed a diathesis-stress pattern, regardless of the child outcome being examined (i.e., callous-unemotional traits, internalization of parental values, and cooperation with parental monitoring). A recent meta-analysis by Slagt et al. (2016) found that negative emotionality functioned according to a differential susceptibility model, but only when emotionality was measured before age 1. Therefore, we would not expect negative emotionality to follow a differential susceptibility framework in the present study involving preschoolers. Importantly; however, Slagt et al. (2016) mention that their results did not withstand sensitivity analyses that account for the possibility of publication bias. Despite some evidence for negative emotionality functioning in accordance with a differential susceptibility framework, oftentimes, variables reflecting difficult temperament (e.g., child negative affect and emotional lability) function as risk factors for a host of poor outcomes in variety of contexts (Han & Shaffer, 2013; Muris & Ollendick, 2005; Shields & Cicchetti, 2001). For example, Morris and colleagues (2002) found support for the diathesis-stress model; child negative emotionality (i.e., irritability) functioned as a vulnerability factor when combined with negative parenting for first and second graders.

The Inclusion of Sleep as a Key Developmental Outcome

Research on parenting stress and child adjustment has frequently focused on children’s internalizing or externalizing problems (e.g., Anthony et al., 2005). The present study sought to expand upon the extant literature by also examining sleep problems, given that difficulties in this area during the preschool period are associated with a variety of externalizing behavior problems (e.g., inattention and hyperactivity; Hiscock, Canterford, Ukoumunne, & Wake, 2007) and have been linked to poorer adjustment, including lower teacher-reported school adjustment (Bates, Viken, Alexander, Beyers, & Stockton, 2002). Moreover, sleep problems in childhood longitudinally predict internalizing symptoms and disorders in adolescence and even into adulthood (Gregory et al., 2005; Ong, Wickramaratne, Tang, & Weissman, 2006). Scant research has examined the relation between parenting stress and child sleep problems (Meltzer & Mindell, 2007). In a pilot study of mothers and their children aged 3 to 14, Meltzer and Mindell (2007) found that mothers of children with clinically significant sleep disruptions reported more parenting stress than mothers of children who were below the clinical cutoff. Caregivers who are experiencing high levels of stress may find it difficult to implement strategies conducive to their children’s sleep development. Thus, mild sleep difficulties may develop into chronic ones that have long-lasting implications for development. Continued research on factors that contribute to children’s sleep difficulties, particularly early in childhood, is crucial.

The Current Study

The current study builds upon the extant literature by: (1) examining sensitivity to parenting stress, a variable relevant to all families; (2) using a multi-method approach to examine child sensitivity (i.e., genetic, physiological, and behavioral) to parenting stress; and (3) incorporating child sleep problems, in addition to internalizing and externalizing problems, as a key outcome of interest.

It was hypothesized that children’s genetic (i.e., having at least one short allele of 5-HTTLPR), physiological (i.e., higher baseline RSA), and behavioral (i.e., higher levels of negative emotionality) sensitivity would moderate the positive associations between maternal parenting stress and mothers’ perceptions of child internalizing, externalizing, and sleep problems. In light of the mixed literature, we did not hypothesize whether our findings involving child baseline RSA and 5-HTTLPR would be most consistent with a diathesis-stress or a differential susceptibility framework. Because the literature has consistently identified children’s negative emotionality as a risk factor for psychopathology, we anticipated that the moderation results involving this variable would follow a diathesis-stress pattern. Specifically, it was predicted that when both parenting stress and child negative emotionality were higher, adjustment problems would be higher than when parenting stress was lower.

Method

Participants

Participants included 108 mothers (Mage = 30.68 years, SDage = 6.06,) and their preschool-aged biological children (Mage = 3.50 years, SDage = .51, 61% boys) who were recruited through flyers posted at local businesses and Head Start centers. Due to budget constraints, genetics data was only collected for the first 98 families. Inclusion criteria required that mothers and children were fluent in English. Pregnant mothers were excluded because pregnancy can alter women’s typical physiological responses. Children with developmental disabilities that could hinder participation were not included in the present study. All mothers were required to have lived with their children for at least two years.

The sample was economically- and racially-diverse. Nearly half (47%) of the women identified as Black; approximately 43% were Caucasian; about 1% were Asian; about 5% were Hispanic; and about 5% identified as “other.” The majority of families (52%) indicated they had a total household income of less than $30,000; 15% were between $30,000 and $49,999; and 33% had a total income above $50,000. Nearly half (43%) of mothers reported they had never been married; 46% indicated they were currently married; and 12% were separated, divorced, widowed, or engaged.

Procedures

Mothers participated in a phone screening with a research assistant and, if eligible, were mailed a packet of measures to complete before visiting the lab. Mothers completed unfinished measures at the lab visit. Mothers provided written consent as well as permission for their child to participate, and children provided verbal assent. To collect RSA data, electrodes were placed on the child before the behavioral observation tasks. The present study focused on RSA data collected during a 4-minute baseline task where children and their mothers were instructed to remain quiet and sit still with their hands resting on the table. Children provided saliva samples for the genetic assays. Mothers were compensated $100 and children chose a small prize. All study procedures were in accordance with the sponsoring university’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Parenting stress

Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF; Abidin, 1995)

The PSI-SF consists of 36 items and allows for the calculation of a Total Stress score and three subscale scores, each consisting of 12 items rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). This study utilized the Total Stress scale, which measures the degree to which the caregiver experiences stress due to his/her role as a parent (α = .91).

Child sensitivity factors

Genetic sensitivity

Child genetic sensitivity was assessed via 5-HTTLPR. Children provided DNA samples using Oragene DNA kits (DNA Genotek; Kanata, Ontario, Canada). Children sucked on buccal swabs to fill the Oragene vials with 4 ml of saliva. The vials were sealed and mailed to the Psychiatric Genetics Laboratory in Iowa City, Iowa. Genotyping for 5-HTTLPR involved the primers F-GGCGTTGCCGCTCTGAATGC and R-GAGGACTGAGCTGGACAACCAC, standard Taq polymerase and buffer, standard dNTPs with the addition of 100 μm M7-deaza GTP, and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide. Next, the polymerase chain reaction products underwent electrophoresis on a 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel and DNA was then visualized via silver staining. Two individuals who were blind to the study hypotheses and unaware of information regarding the participants determined the children’s genotype statuses. Samples were prepared in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines and the frequency distribution for 5-HTTLPR (χ2 = 1.87, df = 1, p = .17) was in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. With regard to 5-HTTLPR, 56.60% had one or two copies of the short allele and 43.40% were homozygous for the long allele. To control for potential differences in dependent variables due to child race, this variable was entered as a covariate in all moderation analyses. Based on prior research examining effects of race on gene expression (Vijayendran et al., 2012), there was no expectation of further moderation of GxE effects by race. However, to directly rule out moderation by race, exploratory analyses were conducted. These analyses resulted in non-significant effects for externalizing and sleep problems, but a significant three-way interaction for internalizing problems. We explicate the three-way interaction in supplemental material available from the authors, noting that the GXE effect is significant for Black individuals, but not for White participants, in this case.

Similar to procedures outlined in the extant literature (e.g., Brody et al., 2013), the short allele of 5-HTTLPR was treated as the genotype that confers sensitivity to the environment. Therefore, children who were homozygous for the long allele of 5-HTTLPR were assigned a code of “0” and those with one or two copies of the short allele were given a “1”.

Physiological sensitivity

Physiological sensitivity was assessed via children’s resting RSA. RSA data were collected during the baseline task using MindWare BioLab 3.0.6 software and analyzed using MindWare HRV 3.0.17 software (MindWare Technologies, Ltd., Gahanna, OH.). RSA data was collected in 30-second epochs following recommendations of the Society for Psychophysiological Research Committee on Heart Rate Variability (Berntson et al., 1997). Electrodes were placed on the right collarbone (i.e., the right clavicle area), in the cleft of the throat (i.e., below the Adam’s apple), at the base of the rib areas on the left and the right sides of the body, near the xiphoid process, midway down the back, and below the base of the skull upon the back. Respiration was monitored by impedance cardiography (Ernst, Litvack, Lozano, Cacioppo, & Berntson, 1999) and the respiratory frequency band was set to include frequencies between 0.12 and 0.40 Hz. To derive the interbeat interval series, which was ultimately used in the calculation of RSA values, MindWare used a peak-identification algorithm and calculated a 4 Hz time series via interpolation. The residual series was tapered via a Hamming window and then submitted to a Discrete Fourier transformation (DFT) or to a fast Fourier transformation (FFT) through the LabVIEW module (National Instruments, Austin, TX), resulting in the spectral distribution (MindWare HRV Module, Gahanna, Ohio). The EKG signal was digitized at 1000 Hz. Within MindWare HRV 3.0.17, RSA values were calculated using the integral power within the respiratory frequency band (i.e., the statistical variance of the interbeat interval time series within the specified respiratory frequency band). Visual inspection and an algorithm developed by Berntson, Quigley, Jang, and Boysen (1990), were used to identify and remove artifact peaks. We removed 30-second epochs in which greater than 10% of peaks needed to be edited (e.g., Perry et al., 2013). In the current analyses, mean scores for children’s RSA during the baseline task were computed across all available epochs for that task. To calculate the mean, children were required to have at least two clean 30-second epochs (i.e., epochs in which no more than 10% of the data points needed to be edited) for the baseline task.

Behavioral sensitivity

Mothers completed the Emotion Regulation Checklist (ERC; Shields & Cicchetti, 1997), which assesses children’s adaptive emotion regulation and emotion dysregulation. The present study relied on the Lability/Negativity subscale (15 items), which captures the degree to which a child is inflexible, emotionally labile, and displays dysregulated negative affect (e.g., “Is easily frustrated”). Responses are provided on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = never, 4 = always). Cronbach’s alpha for the present study was .73.

Child adjustment

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000)

Mothers reported on their children’s adjustment problems during the past 6 months using the CBCL. Unstandardized scores were used in analyses and higher scores indicated greater levels of problems. On the Sleep Problems subscale (α = .68; 7 items) about 7% of the sample fell in the borderline (T score of 65–69) or clinical (T scores greater than 70) ranges. Whereas the Internalizing Problems scale (α = .90; 36 items) indicated children’s levels of anxious, depressed, and withdrawn behaviors as well as somatic complaints, the Externalizing Problems scale (α = .87; 24 items) assessed delinquent and aggressive behaviors. On the Internalizing and Externalizing Problems Scales, 11% and 10% of children were in the borderline (T score of 60–63) or clinical (T scores greater than 63) ranges, respectively.

Demographics

Demographics questionnaire

Caregivers provided background information (e.g., child race, child sex, total household income, maternal education and maternal marital status) on a demographics questionnaire.

Missing Data

In total, 94 children had sufficient baseline RSA data to calculate mean scores. Missing RSA data was due to a number of factors, including technological difficulties (particularly early in data collection), failure of children to participate in the video tasks, as well as the stringent data editing methods used. Seventy-six children provided saliva samples that could be genotyped for 5-HTTLPR. Missing genetics data was due either to difficulties in the collection of saliva samples or in the genotyping process. Overall, 106 mothers filled out the CBCL and PSI-SF and reported on their child’s sex, and 105 mothers reported on their child’s race. We were able to compute the ERC Lability/Negativity scale for 104 families. Missing data techniques were utilized to maximize the number of participants included in the moderation analyses. Little’s MCAR was not statistically significant χ2(16) = 13.60, p = .63, indicating that the data were missing completely at random (Little, 1988). To handle missing data, multiple imputation was implemented only for continuous, primary study variables (i.e., child baseline RSA as well as CBCL, PSI-SF, and ERC scores). A total of 10 imputations were conducted, and pooled values were then used in the moderation analyses.

Analytic Plan

Descriptive statistics were run and Pearson bivariate correlations were calculated to examine relations between the main study variables (See Table 1). Single moderation models were run for each of the dependent and moderator variables separately using the publicly-available PROCESS SPSS macro plug-in (http://processmacro.org/index.html; Hayes, 2013). In PROCESS, mean centering was implemented to reduce nonessential multicollinearity between the independent variable, moderator variable, and interaction term (Aiken & West, 1991), but was only employed in the models involving baseline RSA and negative emotionality so as to preserve the dichotomous coding of the genetics variable. Significant moderation occurred when the interaction term between the predictor and moderator was significant and the 95% confidence interval did not include zero. For the genetics models, all interactions were probed by examining conditional effects for children in the high (at least one short allele of 5-HTTLPR) and low (zero short alleles of 5-HTTLPR) genetic sensitivity groups. For moderation models involving child baseline RSA and negative emotionality, interaction terms were probed by examining conditional effects at low (−1 SD below the mean) and high (+1 SD above the mean) levels of the moderator.

Table 1.

Intercorrelations and Descriptive Statistics for Main Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | M (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maternal Parenting Stress | __ | .23* | .07 | .49** | .41** | .58** | .50** | 66.61 (17.52) | 36–131 |

| 2. Child Baseline RSA | __ | .10 | .25* | .21 | .18 | .16 | 6.19 (1.23) | 3.00–9.08 | |

| 3. Child Genetic Sensitivity | __ | −.001 | .05 | .18 | .12 | .57 (.50) | 0–1 | ||

| 4. Child Negative Emotionality | __ | .42** | .52** | .65** | 28.56 (6.55) | 15–46 | |||

| 5. Child Sleep Problems | __ | .51** | .52** | 3.34 (2.55) | 0–11 | ||||

| 6. Child Internalizing Problems | __ | .65** | 7.81 (7.39) | 0–50 | |||||

| 7. Child Externalizing Problems | __ | 10.37 (8.04) | 0–36 |

p < .01.

p < .05.

Significant interactions were probed further by first examining the value of the cross-over point, or the point on the independent variable (X1) at which regression lines for different values of the moderator (X2) converged (Widaman et al., 2012). Both point and interval estimates of the cross-over point were derived (Widaman et al., 2012). When the cross-over point is within the range of observed values of X1 in the sample, this is suggestive of a disordinal interaction (i.e., more likely reflective of differential susceptibility than diathesis-stress; Widaman et al., 2012). Alternatively, cross-over values that fall outside of the range of X1 are typically indicative of an ordinal interaction, and therefore, are more in line with a diathesis-stress model (Widaman et al., 2012). Whereas the point estimate for the cross-over point can be calculated based on a standard regression equation, the interval estimate of the cross-over point requires a re-parameterized regression equation (Widaman et al., 2012). In the re-parameterized equation, the independent variable is centered at the cross-over point to yield a standard error, which is then used to calculate the 95% confidence interval of the cross-over point (i.e., the interval estimate of the cross-over point; Widaman et al., 2012).

When considered together, point and interval estimates of the cross-over point can yield four main outcomes (Widaman et al., 2012). First, a disordinal interaction can occur when the point estimate of the cross-over point falls within the range of the independent variable and the interval estimate falls completely within that range. Second, a disordinal interaction can occur when the cross-over point estimate is within the range of the independent variable but the interval estimate falls partly outside of this range. Third, an ordinal interaction can include a point estimate of the cross-over term that falls outside of the range of the independent variable but has an interval estimate partly within the range. Lastly, an ordinal interaction can occur when both the point and interval estimates of the cross-over point fall outside of the range of the independent variable. All re-parameterized regression equations were run using the nonlinear regression function in SPSS.

Results

The simple correlation between the genetics and parenting stress variables was not significant (see Table 1), suggesting that any observed significant gene-environment interactions were not attributable to gene-environment correlation. For all moderations, child race was entered as a covariate to statistically control for potential differences based on this demographic characteristic (Belsky & Beaver, 2011; 1 = Caucasian, 2 = Black, 3 = Asian, 4 = Hispanic/Latino, and 5 = Other). Also, because CBCL raw scores were used as the dependent variables in analyses, gender was included as a covariate in all models.

Moderation Findings

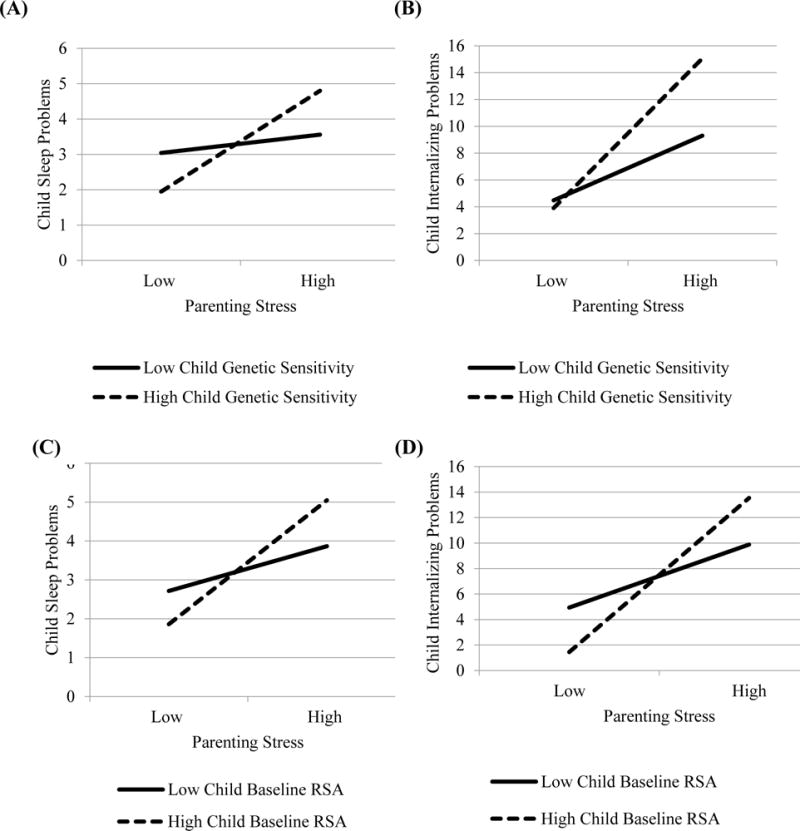

Child genetic sensitivity

Children’s 5-HTTLPR status significantly moderated the positive association between maternal parenting stress and child sleep problems, b = .07, t = 2.05, p < .05, 95% CI [.002, .13]. Simple slopes analyses indicated that parenting stress was only significantly, positively associated with child sleep problems for children high in genetic sensitivity (see Table 2 and Figure 1, Panel A). There was not a significant main effect for genetic sensitivity, b = −4.42, t = −1.97, p = .05, 95% CI [−8.89, .05], or parenting stress, b = .01, t = .59, p = .56, 95% CI [−.04, .06]. Neither child race, b = .04, t = .20, p = .84, 95% CI [−.39, .47], nor child sex, b = .12, t = .21, p = .84, 95% CI [−1.02, 1.26], served as significant covariates in the model. The point (Ĉ = 67.03) and interval (SE = 8.46, 95% CI [50.45, 83.61]) estimates of the cross-over point both fell within the range of the parenting stress variable, thus indicating the interaction was disordinal and the results were most in line with a differential susceptibility framework.

Table 2.

Simple Slopes of Maternal Parenting Stress on Child Sleep, Internalizing, and Externalizing Problems at Low and High Levels of Child Genetic, Physiological, and Behavioral Sensitivity

| Sensitivity Factor

|

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic (5-HTTPLPR; N = 74) | Physiological (Baseline RSA; N = 108) | Behavioral (Negative Emotionality; N = 108) | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Outcome Variable | b (SE) | t | R2 | ΔR2 | F | 95% CI | b (SE) | t | R2 | ΔR2 | F | 95% CI | b (SE) | t | R2 | ΔR2 | F | 95% CI |

| Sleep Problems | 0.20 | .05 | 3.32** | 0.21 | .04 | 5.32** | .23 | .00 | 5.71** | |||||||||

| Low Sensitivity | .01 (.03) | 0.59 | −.04, .06 | .02 (.02) | .91 | −.02, .06 | .04 (.02) | 1.71 | −.01, .08 | |||||||||

| High Sensitivity | .08 (.02) | 4.01** | .04, .12 | .09 (.02) | 4.42** | .05, .13 | .04 (.02) | 2.20* | .004, .07 | |||||||||

| Internalizing Problems | 0.38 | .04 | 8.20** | 0.38 | .04 | 12.20** | .45 | .03 | 15.81** | |||||||||

| Low Sensitivity | .14 (.07) | 1.97 | −.002, .27 | .14 (.05) | 2.61* | .03, .25 | .09 (.05) | 1.73 | −.01, .19 | |||||||||

| High Sensitivity | .32 (.06) | 5.67** | .20, .43 | .35 (.05) | 6.54** | .24, .45 | .24 (.04) | 5.51** | .15, .32 | |||||||||

| Externalizing Problems | 0.25 | .004 | 4.60** | 0.29 | .03 | 7.84** | .49 | .02 | 18.62** | |||||||||

| Low Sensitivity | .18(.07) | 2.36* | .03, .33 | .13 (.06) | 2.19* | .01, .26 | .02 (.05) | .45 | −.08, .13 | |||||||||

| High Sensitivity | .23 (.06) | 3.86** | .11, .35 | .31 (.06) | 5.10** | .19, .43 | .16 (.04) | 3.55** | .07, .24 | |||||||||

Note. ΔR2 = change in R2 due to interaction term. F = F value for the overall model.

p< .01.

p< .05

Figure 1.

Maternal parenting stress was positively associated with child sleep (Panel A) and internalizing (Panel B) problems when children were high in genetic sensitivity. For children with high levels of physiological sensitivity, maternal parenting stress was positively associated with child sleep (Panel C) and internalizing (Panel D) problems. The positive relation between parenting stress and child internalizing problems was also significant for children with low levels of physiological sensitivity.

Children’s 5-HTTLPR status also significantly moderated the positive association between maternal parenting stress and child internalizing problems, b = .18, t = 2.02, p < .05, 95% CI [.002, .36]. A significant simple slope was found at high levels of genetic sensitivity (see Table 2). For children carrying at least one copy of the short allele, parenting stress was significantly and positively associated with child internalizing problems (see Figure 1, Panel B). There was not a significant main effect for genetic sensitivity, b = −9.63, t = −1.56, p = .12, 95% CI [−21.99, 2.72], or parenting stress, b = .14, t = 1.97, p = .05, 95% CI [−.002, .27]. Neither child race, b = .64, t = 1.07, p = .29, 95% CI [−.44, 1.82], nor child sex, b = −.29, t = −.18, p = .86, 95% CI [−3.44, 2.86], served as significant covariates in the model. Again, the point (Ĉ = 53.73) estimate of the cross-over point fell within the range of the parenting stress variable. The lower bound of the interval estimate of the cross-over point (SE = 10.96, 95% CI [32.25, 75.21]) fell just outside the range of the parenting stress variable; however, the upper bound of the interval estimate was within the range of parenting stress scores. Collectively, these results lend support for a differential susceptibility model.

Child 5-HTTLPR status did not serve as a significant moderator of the association between maternal parenting stress and child externalizing problems, b = .06, t = .57, p = .57, 95% CI [−.14, .25]. There was not a significant main effect for genetic sensitivity, b = −2.17, t = −.32, p = .75, 95% CI [−15.55, 11.20] but there was a significant main effect for parenting stress, b = .18, t = 2.36, p < .05, 95% CI [.03, .33]. Neither child race, b = −.17, t = −.27, p = .79, 95% CI [−1.46, 1.11], nor child sex, b = −1.08, t = −.63, p = .53, 95% CI [−4.49, 2.33], served as significant covariates in the model.

Child physiological sensitivity

Child baseline RSA significantly moderated the positive association between maternal parenting stress and child sleep problems, b = .03, t = 2.27, p < .05, 95% CI [.004, .06], such that for children with higher levels of baseline RSA, maternal parenting stress was significantly and positively associated with child sleep problems (see Table 2 and Figure 1, Panel C). There was a significant main effect for parenting stress, b = .06, t = 4.08, p < .001, 95% CI [.03, .08], but not child baseline RSA, b = .17, t = .84, p = .40, 95% CI [−.23, .58]. Neither child race, b = −.07, t = −.37, p = .29, 95% CI [−.44, .30], nor child sex, b = .01, t = .02, p = .98, 95% CI [−.92, .94], served as significant covariates in the model. Both the point (Ĉ = −5.57) and interval (SE = 7.20, 95% CI [−19.68, 8.54]) estimates of the cross-over point fell outside of the range of the parenting stress variable, thus indicating the interaction was ordinal and the results were most in line with a diathesis-stress framework.

Child baseline RSA also moderated the association between maternal parenting stress and child internalizing problems, b = .09, t = 2.51, p < .05, 95% CI [.02, .16]. Significant simple slopes were found at higher and lower levels of child baseline RSA (see Table 2); for children with higher and lower levels of baseline RSA, there was a significant, positive association between parenting stress and internalizing problems (see Figure 1, Panel D). There was a significant main effect for parenting stress, b = .24, t = 7.03, p < .001, 95% CI [.17, .31], but not child baseline RSA, b = .03, t = .07, p = .95, 95% CI [−1.01, 1.08]. Neither child race, b = .52, t = −1.09, p = .28, 95% CI [−.43, 1.47], nor child sex, b = .08, t = .07, p = .95, 95% CI [−2.31, 2.48], served as significant covariates in the model. Because the point (Ĉ = −.39) and interval (SE = 5.97, 95% CI [−12.09, 11.31]) estimates of the cross-over point were outside the range of the parenting stress variable (i.e., an ordinal interaction was present), these results are consistent with a diathesis-stress model.

Child baseline RSA was not a significant moderator of the association between maternal parenting stress and child externalizing problems, b = .07, t = 1.85, p = .07, 95% CI [−.01, .15]. There was a significant main effect for parenting stress, b = .22, t = 5.60, p < .001, 95% CI [.14, .30], but not child baseline RSA, b = .05, t = .09, p = .93, 95% CI [−1.14, 1.24]. Neither child race, b = −.03, t = −.05, p = .96, 95% CI [−1.11, 1.05], nor child sex, b = −1.47, t = 1.07, p = .29, 95% CI [−4.20, 1.26], served as significant covariates in the model.

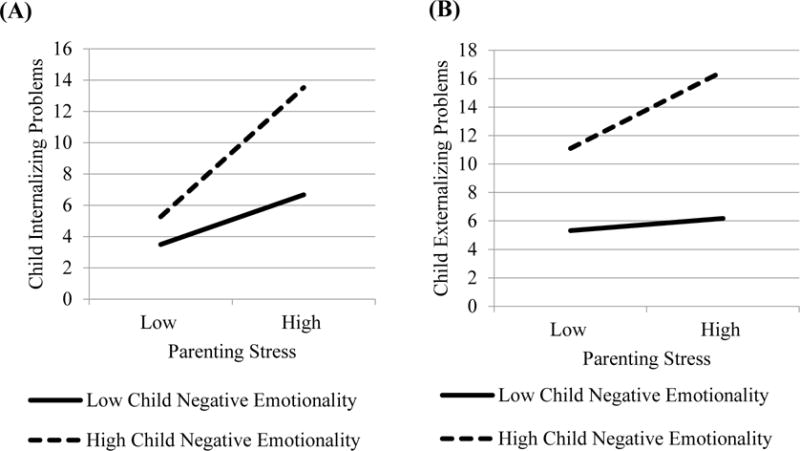

Child behavioral sensitivity

Children’s negative emotionality significantly moderated the association between maternal parenting stress and child internalizing problems, b = .01 t = 2.47, p < .05, 95% CI [.002, .02]. The simple slope was significant at higher levels of negative emotionality such that the positive association between maternal parenting stress and child internalizing problems only held for children higher in negative emotionality (see Table 2 and Figure 2, Panel A). There was a significant main effect for parenting stress, b = .16, t = 4.33, p < .001, 95% CI [.09, .24], and child negative emotionality, b = .33, t = 3.28, p < .01, 95% CI [.13, .54]. Neither child race, b = .43, t = .95, p = .34, 95% CI [−.47, 1.32], nor child sex, b = 1.35, t = 1.13, p = .26, 95% CI [−1.03, 3.73], served as significant covariates in the model. Both the point (Ĉ = −29.51) and interval (SE = 15.56, 95% CI [−60.01, .99]) estimates of the cross-over point fell outside of the bounds of the parenting stress variable, indicating the interaction was ordinal. In turn, these results were in line with a diathesis-stress model.

Figure 2.

Maternal parenting stress was positively associated with child internalizing (Panel A) and externalizing (Panel B) problems, only when children were high in behavioral sensitivity.

Children’s negative emotionality also served as a significant moderator in the association between maternal parenting stress and child externalizing problems, b = .01, t = 2.18, p < .05, 95% CI [.001, .02]. The simple slope was significant at higher levels of negative emotionality such that the positive association between maternal parenting stress and child externalizing problems was significant only for children higher in negative emotionality (see Table 2 and Figure 2, Panel B). There was a significant main effect for parenting stress, b = .09, t = 2.33, p < .05, 95% CI [.12, .17], and child negative emotionality, b = .62, t = 6.02, p < .001, 95% CI [.42, .83]. Neither child race, b = −.27, t = −.58, p = .56, 95% CI [−1.18, .64], nor child sex, b = .40, t = .33, p = .74, 95% CI [−2.03, 2.83], served as significant covariates in the model. Similar to the results for internalizing problems, the point (Ĉ = −61.19) and interval (SE = 30.67, 95% CI [−121.30, −1.08]) estimates of the cross-over point were outside of the range of the parenting stress variable and, therefore, results were in line with a diathesis-stress framework.

Lastly, child negative emotionality was not a significant moderator of the association between parenting stress and child sleep problems, b = .0002, t = .08, p = .94, 95% CI [−.004, .004]. There was a significant main effect for parenting stress, b = .04, t = 2.44, p < .05, 95% CI [.01, .07], and child negative emotionality, b = .12, t = 2.78, p < .01, 95% CI [.03, .20]. Neither child race, b = −.08, t = −.42, p = .67, 95% CI [−.44, .29], nor child sex, b = .18, t = .37, p = .72, 95% CI [−.79, 1.15], served as significant covariates in the model.

Discussion

Parenting stress is a common phenomenon and, irrespective of its origins, is associated with child maladjustment (Anthony et al., 2005; Crnic, Gaze, & Hoffman, 2005). Our study expands upon the extant literature by demonstrating the ways that children’s genetic, physiological, and behavioral sensitivity factors moderate the positive associations between maternal parenting stress and mothers’ perceptions of child internalizing, externalizing, and sleep problems.

Consistent with hypotheses, child genetic sensitivity moderated the associations between parenting stress and child internalizing and sleep problems. These findings were in line with a differential susceptibility framework and thus were largely consistent with recent research that has examined gene-environment interactions in relation to outcomes (e.g., Bogdan et al., 2014; van IJzendoorn, Belsky, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 2012). In particular, maternal parenting stress was significantly, positively associated with child sleep and internalizing problems only for children who were high in genetic sensitivity. Though prior work has examined the role of 5-HTTLPR in internalizing symptoms (e.g., Benjet, Thompson, & Gotlib, 2010), no prior work to our knowledge has examined preschoolers’ sleep problems as an outcome in studies of gene-environment interactions using either diathesis-stress or differential susceptibility frameworks. Given the potential regulatory and protective functions of sleep (Michels, et al., 2013; Silk et al., 2007), and the fact that sleep problems have been related to a host of adjustment problems across the developmental spectrum (Gregory et al., 2005; Hiscock et al., 2007), understanding variables that influence sleep quality, particularly during the preschool years, is important. Our findings, though preliminary, suggest that preschoolers’ 5-HTTLPR status contributes to sleep quality in the context of parenting stress.

Though children’s 5-HTTLPR status did not moderate the association between maternal parenting stress and child externalizing problems, the results followed a pattern similar to those found for internalizing and sleep problems. Of note, findings on the role of 5-HTTLPR in child externalizing problems have been mixed, with some studies indicating the effect of family adversity on child externalizing problems is greater for carriers of the short allele, and other research either yielding the opposite pattern or null results (for a review, see Weeland, Overbeek, Castro, & Matthys, 2015). Weeland and colleagues (2015) highlight the methodological differences (i.e., sample size and composition, conceptualization, and power) across studies on gene-environment interactions and child externalizing problems, which likely contribute to the inconsistencies in findings throughout the extant literature.

The pattern of findings examining child RSA was largely consistent with a diathesis-stress model. Maternal parenting stress was significantly and positively associated with sleep problems only for children with higher baseline RSA; parenting stress was associated with child internalizing problems for children with higher and lower levels of baseline RSA. The present findings suggest that maternal parenting stress is a potent risk factor during the preschool period, particularly for children with higher physiological sensitivity (i.e., RSA). High baseline RSA reflects greater openness to, and engagement with, the environment (Beauchaine, 2001). Greater engagement with a high-stress environment may increase children’s exposure to negative parenting behaviors and experiences, thereby increasing the risk for poor outcomes such as internalizing or sleep problems.

Children’s baseline RSA did not moderate the association between maternal parenting stress and child externalizing problems. Research on the direct relation between baseline RSA and child externalizing problems is mixed with some findings indicating that lower baseline RSA is associated with greater externalizing problems (e.g., Calkins & Dedmon, 2000; Beauchaine, Gatzke-Kopp, & Mead, 2007), while other research demonstrates the opposite (e.g., Dietrich et al. 2007) or finds no relationship between these variables (e.g., Calkins et al. 2007; El-Sheikh & Whitson, 2006). These mixed findings suggest that the effects of RSA on child outcomes likely vary depending on context, and the present results indicate that in the context of parenting stress, child RSA may be more closely linked to internalizing and sleep problems rather than externalizing problems. Regardless, it will be important for future research to continue to explore child RSA in context in relation to child externalizing problems to develop a more nuanced understanding of the unique roles that child RSA plays in this domain of child maladjustment under various environmental conditions.

Finally, children’s negative emotionality moderated the association between maternal parenting stress and child internalizing and externalizing problems in ways consistent with a diathesis-stress model. These results corroborate previous findings (e.g., Morris et al., 2002) and extend the literature by demonstrating the vulnerability function of child negative emotionality in the associations between maternal parenting stress and child internalizing and externalizing problems. Alternatively, child negative emotionality was not a significant moderator of the association between maternal parenting stress and child sleep problems. The bivariate relations among variables suggest that these variables are directly related to one another and in fact, are likely reciprocally related (Bell & Belsky, 2008). The results indicate sleep adjustment may be most impacted by maternal parenting stress for preschoolers who are more sensitive to their environment due to their genetic makeup and physiology.

Overall, the present analyses provide evidence of child genetic, physiological, and behavioral sensitivity to parenting stress, but limitations are noted. The design was cross-sectional and, though important for establishing preliminary relations among variables, future work should incorporate the variables identified here into a longitudinal analysis. A longitudinal design would allow for an examination of reciprocal relations over time, extending previous research that has shown that parenting stress and child behavior problems tend to influence each other mutually (Neece, Green, & Baker, 2012). Additionally, longitudinal analyses would allow for the exploration of possible mechanisms (e.g., parenting behaviors) that are likely implicated in the relations between parenting stress and child adjustment problems. We relied on rigorous statistical tests to differentiate between differential susceptibility and diathesis-stress (Widaman et al., 2012) but acknowledge that other approaches could have been implemented (e.g., Roisman et al., 2012; Del Giudice, in press). The current study used mothers’ reports of child internalizing and externalizing problems and future research should include other reports (e.g., daycare teacher) and/or behavioral observations. Future research could also include multiple assessments of sleep problems (e.g., actigraphs). Though the sample size was comparable to, or even larger than, samples used in some other studies that have examined gene-environment interactions in youth (Benjet et al., 2010; Sheese, Rothbart, Voelker, & Posner, 2012), it was still relatively small and somewhat restricted in the range of child adjustment problems. Accordingly, the results are best interpreted in the context of the extant literature. It will be beneficial for future research with larger sample sizes to more directly examine the unique contributions of each sensitivity factor by determining whether effects for a given sensitivity factor hold when controlling for the others.

Despite these limitations, this study moves the literature forward by documenting interactions between preschoolers’ genetic, physiological, and behavioral sensitivity and mothers’ perceived parenting stress in an economically- and racially- diverse sample. The study also advances the literature by examining sleep adjustment, given the critical role of this process in child development (Alfano & Gamble, 2009; Dewald, Meijer, Oort, Kerkhof, & Bögels, 2010). Findings from the present study demonstrate how factors across genetic, physiological, and behavioral levels may make children more or less sensitive to the adverse effects of parenting stress during the preschool period. The relative independence of the three moderators examined suggests that effects of parenting stress on the interrelated outcomes of internalizing, externalizing, and sleep problems may be buffered or moderated by a number of different vulnerability and susceptibility factors. Results suggest that it is important for prevention and intervention efforts to target mothers’ parenting stress to help them promote their children’s optimal adjustment. In particular, future research may explore the benefit of providing effective parenting strategies for caregivers of more and less genetically, physiologically, and behaviorally sensitive youth as a means of differentially countering the impact of parenting stress on healthy child development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the William A. and Barbara R. Owens Institute for Behavioral Research at the University of Georgia and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (P30 DA027827) Parent Grant awarded to the University of Georgia Center for Contextual Genetics and Prevention Science. We would like to acknowledge Dr. Keith F. Widaman for providing consultation on our statistical approach.

References

- Abidin RR. Parenting Stress index. 3rd. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alfano CA, Gamble AL. The role of sleep in childhood psychiatric disorders. Child & Youth Care Forum. 2009;38:327–340. doi: 10.1007/s10566-009-9081-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony LG, Anthony BJ, Glanville DN, Naiman DQ, Waanders C, Shaffer S. The relationships between parenting stress, parenting behaviour and preschoolers’ social competence and behaviour problems in the classroom. Infant and Child Development. 2005;14:133–154. doi: 10.1002/icd.385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE, Viken RJ, Alexander DB, Beyers J, Stockton L. Sleep and adjustment in preschool children: Sleep diary reports by mothers relate to behavior reports by teachers. Child Development. 2002;73:62–74. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP. Vagal tone, development, and Gray’s motivational theory: Toward an integrated model of autonomic nervous system functioning in psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:183–214. doi: 10.1017/S0954579401002012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, Gatzke-Kopp L, Mead HK. Polyvagal theory and developmental psychopathology: Emotion dysregulation and conduct problems from preschool to adolescence. Biological Psychology. 2007;74:174–184. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell BG, Belsky J. Parents, parenting, and children’s sleep problems: Exploring reciprocal effects. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2008;26:579–593. doi: 10.1348/026151008x285651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Beaver KM. Cumulative-genetic plasticity, parenting and adolescent self-regulation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52:619–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02327.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pluess M. Beyond diathesis stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:885–908. doi: 10.1037/a00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pluess M. Genetic moderation of early childcare effects on social functioning across childhood: A developmental analysis. Child Development. 2013;84:1209–1225. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C, Thompson RJ, Gotlib IH. 5-HTTLPR moderates the effect of relational peer victimization on depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:173–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntson GG, Bigger JJ, Eckberg DL, Grossman P, Kaufmann PG, Malik M, van der Molen MW. Heart rate variability: Origins, methods, and interpretive caveats. Psychophysiology. 1997;34:623–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntson GG, Quigley KS, Jang JF, Boysen ST. An approach to artifact identification: Application to heart period data. Psychophysiology. 1990;27:586–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1990.tb01982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode AA, George MW, Weist MD, Stephan SH, Lever N, Youngstrom EA. The impact of parent empowerment in children’s mental health services on parenting stress. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2016;25:3044–3055. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0462-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan R, Agrawal A, Gaffrey MS, Tillman R, Luby JL. Serotonin transporter‐linked polymorphic region (5‐HTTLPR) genotype and stressful life events interact to predict preschool‐onset depression: A replication and developmental extension. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014;55:448–457. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, Ellis BJ. Biological sensitivity to context: I. An evolutionary-developmental theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:271–301. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Yu T, Chen Y-f, Kogan SM, Evans GW, Beach SRH, Philibert RA. Cumulative socioeconomic status risk, allostatic load, and adjustment: A prospective latent profile analysis with contextual and genetic protective factors. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49:913–927. doi: 10.1037/a0028847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Dedmon SE. Physiological and behavioral regulation in two-year-old children with aggressive/destructive behavior problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28:103–118. doi: 10.1023/A:1005112912906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Graziano PA, Keane SP. Cardiac vagal regulation differentiates among children at risk for behavioral problems. Biological Psychology. 2007;74:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, Poulton R. Influence of life stress on depression: Moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301:386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conradt E, Measelle J, Ablow JC. Poverty, problem behavior, and promise: Differential susceptibility among infants reared in poverty. Psychological Science. 2013;24:235–242. doi: 10.1177/0956797612457381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Bowker A, Cooper SM. Parenting daily hassles, child temperament and social adjustment in preschool. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2003;18:376–395. doi: 10.1016/s0885-2006(03)00045-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa NM, Weems CF, Pellerin K, Dalton R. Parenting stress and childhood psychopathology: An examination of specificity to internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2006;28:113–122. doi: 10.1007/s10862-006-7489-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, Gaze C, Hoffman C. Cumulative parenting stress across the preschool period: Relations to maternal parenting and child behaviour at age 5. Infant and Child Development. 2005;14:117–132. doi: 10.1002/icd.384. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K. Parenting stress and child adjustment: Some old hypotheses and new questions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1998;5:314–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00152.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Del Giudice M. Statistical tests of differential susceptibility: Performance, limitations, and improvements. Development and Psychopathology. doi: 10.1017/S0954579416001292. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewald JF, Meijer AM, Oort FJ, Kerkhof GA, Bögels SM. The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2010;14:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich A, Riese H, Sondeijker FL, Greaves-Lord K, van Roon AM, Ormel J, Rosmalen JM. Externalizing and internalizing problems in relation to autonomic function: A population-based study in preadolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:378–386. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31802b91ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Boyce WT, Belsky J, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. Differential susceptibility to the environment: An evolutionary–neurodevelopmental theory. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:7–28. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M, Whitson SA. Longitudinal relations between marital conflict and child adjustment: Vagal regulation as a protective factor. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:30–39. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst JM, Litvack DA, Lozano DL, Cacioppo JT, Berntson GG. Impedance pneumography: Noise as signal in impedance cardiography. Psychophysiology. 1999;36:333–338. doi: 10.1017/S0048577299981003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Eisenberg N, Eisenbud L. Behavioral and physiological correlates of children’s reactions to others in distress. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:655–663. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.29.4.655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg S, Janus M, Washington J, Simmons RJ, MacLusky I, Fowler RS. Prediction of preschool behavioral problems in healthy and pediatric samples. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1997;18:304–313. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199710000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory AM, Caspi A, Eley TC, Moffitt TE, O’Connor TG, Poulton R. Prospective longitudinal associations between persistent sleep problems in childhood and anxiety and depression disorders in adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:157–163. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-1824-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han ZR, Shaffer A. The relation of parental emotion dysregulation to children’s psychopathology symptoms: The moderating role of child emotion dysregulation. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2013;44:591–601. doi: 10.1007/s10578-012-0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. NewYork: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hiscock H, Canterford L, Ukoumunne OC, Wake M. Adverse associations of sleep problems in Australian preschoolers: national population study. Pediatrics. 2007;119:86–93. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CY, Costeines J, Kaufman JS, Ayala C. Parenting stress, social support, and depression for ethnic minority adolescent mothers: Impact on child development. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2014;23:255–262. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9807-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Whitley MK. Treatment of parental stress to enhance therapeutic change among children referred for aggressive and antisocial behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:504–515. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.3.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Kochanska G. Child temperament moderates effects of parent–child mutuality on self-regulation: A relationship-based path for emotionally negative infants. Child Development. 2012;83:1275–1289. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch FS, Ludvigsson J, Sepa A. Parents’ psychological stress over time may affect children’s cortisol at age 8. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2010;35:950–959. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Boldt LJ, Kim S, Yoon JE, Philibert RA. Developmental interplay between children’s biobehavioral risk and the parenting environment from toddler to early school age: Prediction of socialization outcomes in preadolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2015;27:775–790. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Kim S, Barry RA, Philibert RA. Children’s genotypes interact with maternal responsive care in predicting children’s competence: Diathesis-stress or differential susceptibility? Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:605–616. doi: 10.1017/s0954579411000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LabVIEW [Computer software] Austin, TX: National Instruments; [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne JV, Herzing LBK, Cook EH, Lebailly SA, Gouze KR, Hopkins J, Bryant FB. Gene × Environment effects of serotonin transporter, dopamine receptor D4, and monoamine oxidase A genes with contextual and parenting risk factors on symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder, anxiety, and depression in a community sample of 4-year-old children. Development and Psychopathology. 2013;25:555–575. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412001241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Rith-Najarian L, Dirks MA, Sheridan MA. Low vagal tone magnifies the association between psychosocial stress exposure and internalizing psychopathology in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2015;44:314–328. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.843464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer LJ, Mindell JA. Relationship between child sleep disturbances and maternal sleep, mood, and parenting stress: A pilot study. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:67–73. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merwin SM, Smith VC, Dougherty LR. “It Takes Two”: The interaction between parenting and child temperaemtn on parents’ stress physiology. Developmental Psychobiology. 2015;57:336–348. doi: 10.1002/dev.21301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzacappa E, Tremblay RE, Kindlon D, Saul JP, Arseneault L, Seguin J, Earls F. Anxiety, antisocial behavior, and heart rate regulation in adolescent males. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 1997;38:457–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michels N, Clays E, De Buyzere M, Vanaelst B, De Henauw S, Sioen I. Children’s sleep and autonomic function: low sleep quality has an impact on heart rate variability. Sleep: Journal of Sleep and Sleep Disorders Research. 2013;36:1939–1946. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MindWare Biolab Software (Version 3.0.6) [Computer Software] Gahanna, OH: MindWare Technologies, Ltd.; [Google Scholar]

- MindWare Heart Rate Variability Software (Version 3.17) [Computer Software] Gahanna, OH: MindWare Technologies, Ltd.; [Google Scholar]

- Misri S, Kendrick K, Oberlander TF, Norris S, Tomfohr L, Zhang H, Grunau RE. Antenatal depression and anxiety affect postpartum parenting stress: A longitudinal, prospective study. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry / La Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie. 2010;55:222–228. doi: 10.1177/070674371005500405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J, Robinson D, Aldridge J. Parenting stress and externalizing child behaviour. Child & Family Social Work. 2002;7:219–225. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2206.2002.00242.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Sessa FM, Avenevoli S, Essex MJ. Temperamental vulnerability and negative parenting as interacting predictors of child adjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:461–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00461.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Ollendick TH. The role of temperament in the etiology of child psychopathology. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2005;8:271–289. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-8809-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neece CL, Green SA, Baker BL. Parenting stress and child behavior problems: A transactional relationship across time. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2012;117:48–66. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-117.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obradović J, Bush NR, Stamperdahl J, Adler NE, Boyce WT. Biological sensitivity to context: The interactive effects of stress reactivity and family adversity on socioemotional behavior and school readiness. Child Development. 2010;81:270–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01394.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong SH, Wickramaratne P, Tang M, Weissman MM. Early childhood sleep and eating problems as predictors of adolescent and adult mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;96:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry NB, Nelson JA, Swingler MM, Leerkes EM, Calkins SD, Marcovitch S, O’Brien M. The relation between maternal emotional support and child physiological regulation across the preschool years. Developmental Psychobiology. 2013;55:382–394. doi: 10.1002/dev.21042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Wasserman MS, Miller L, Coplan JD, Bagiella E, Kovelenku P, Sloan RP. Heart period variability and psychopathology in urban boys at risk for delinquency. Psychophysiology. 1998;35:521–529. doi: 10.1017/S0048577298970846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluess M, Belsky J. Differential susceptibility to parenting and quality child care. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:379–390. doi: 10.1037/a0015203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW. Vagal tone: A physiologic marker of stress vulnerability. Pediatrics. 1992;90:498–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raikes HA, Thompson RA. Efficacy and social support as predictors of parenting stress among families in poverty. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2005;26:177–190. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Newman DA, Fraley RC, Haltigan JD, Groh AM, Haydon KC. Distinguishing differential susceptibility from diathesis-stress: Recommendations for evaluating interaction effects. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24(2):389–409. doi: 10.1017/s0954579412000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roxburgh S. Parental time pressures and depression among married dual-earner parents. Journal of Family Issues. 2012;33:1027–1053. doi: 10.1177/0192513X11425324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scott S, O’Connor TG. An experimental test of differential susceptibility to parenting among emotionally-dysregulated children in a randomized controlled trial for oppositional behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53:1184–1193. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon KE, Beauchaine TP, Brenner SL, Neuhaus E, Gatzke-Kopp L. Familial and temperamental predictors of resilience in children at risk for conduct disorder and depression. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:701–727. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheese BE, Rothbart MK, Voelker PM, Posner MI. The dopamine receptor D4 gene 7-repeat allele interacts with parenting quality to predict effortful control in four-year-old children. Child Development Research, 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/863242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, Cicchetti D. Emotion regulation among school-age children: The development and validation of a new criterion Q-sort scale. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:906–916. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.33.6.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, Cicchetti D. Parental maltreatment and emotion dysregulation as risk factors for bullying and victimization in middle childhood. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:349–363. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Vanderbilt-Adriance E, Shaw DS, Forbes EE, Whalen DJ, Ryan ND, Dahl RE. Resilience among children and adolescents at risk for depression: Mediation and moderation across social and neurobiological context. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:841–865. doi: 10.1017/s0954579407000417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slagt M, Dubas JS, Deković M, van Aken MA. Differences in sensitivity to parenting depending on child temperament: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2016 doi: 10.1037/bul0000061. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugden K, Arseneault L, Harrington H, Moffitt TE, Williams B, Caspi A. Serotonin transporter gene moderates the development of emotional problems among children following bullying victimization. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:830–840. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn M, Belsky J, Bakermans-Kranenburg M. Serotonin transporter genotype 5HTTLPR as a marker of differential susceptibility? A meta-analysis of child and adolescent gene-by-environment studies. Translational Psychiatry. 2012;2:e147. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayendran M, Cutrona C, Beach SH, Brody GH, Russell D, Philibert RA. The relationship of the serotonin transporter (SLC6A4) extra long variant to gene expression in an African American sample. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2012;159B:611–612. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeland J, Overbeek G, Castro BO, Matthys W. Underlying mechanisms of gene–environment interactions in externalizing behavior: A systematic review and search for theoretical mechanisms. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2015;18:413–442. doi: 10.1007/s10567-015-0196-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widaman KF, Helm JL, Castro-Schilo L, Pluess M, Stallings MC, Belsky J. Distinguishing ordinal and disordinal interactions. Psychological Methods. 2012;17:615–622. doi: 10.1037/a0030003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodman AC, Mawdsley HP, Hauser-Cram P. Parenting stress and child behavior problems within families of children with developmental disabilities: Transactional relations across 15 years. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2015;36:264–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Vulnerability to psychopathology: A biosocial model. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 1999. Diathesis-stress models; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.