Abstract

Objective

To analyze recent trends in maternal mortality by socio-demographic characteristics and cause of death and to evaluate data quality.

Methods

This observational study compared data from 2008–2009 to 2013– 2014 for 27 states and the District of Columbia that had comparable reporting of maternal mortality throughout the period. Maternal mortality rates were computed per 100,000 live births. Statistical significance of trends and differentials was evaluated using a two-proportion z-test.

Results

The study population included 1,687 maternal deaths and 7,369,966 live births. The maternal mortality rate increased by 23% from 20.6 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2008–2009 to 25.4 in 2013–2014. However, most of the increase was among women aged ≥40, and for non-specific causes of death. From 2008–2009 to 2013–2014, maternal mortality rates increased by 90% for women ≥40, but did not increase significantly for women <40. The maternal mortality rate for non-specific causes of death increased by 48%; however, the rate for specific causes of death did not increase significantly between 2008–2009 (13.5) and 2013–2014 (15.0).

Conclusions

Despite the United Nations Millennium Development Goal and a 44% decline in maternal mortality worldwide from 1990–2015, maternal mortality has not improved in the United States, and appears to be increasing. Maternal mortality rates for women ≥40 and for non-specific causes of death were implausibly high and increased rapidly, suggesting possible over-reporting of maternal deaths which may be increasing over time. Efforts to improve reporting for the pregnancy checkbox, and to modify coding procedures to place less reliance on the checkbox are essential to improving vital statistics maternal mortality data, the official data source for maternal mortality statistics used to monitor trends, identify at-risk populations, and evaluate the success of prevention efforts.

Precis

Maternal mortality is high in the United States and appears to be increasing, with large racial and ethnic disparities; questions about data quality limit interpretation of trends.

Introduction

Maternal mortality has long been seen as a primary indicator of the quality of health care both in the U.S. and internationally (1–5). The U.S. National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) is the source of official U.S. maternal mortality statistics used for subnational and international comparisons (6). To improve the identification of maternal deaths, a pregnancy question was added to the U.S. standard death certificate in 2003 (7). The question has checkboxes to ascertain whether female decedents were not pregnant within the past year, pregnant at the time of death, not pregnant but pregnant within 42 days of death, not pregnant but pregnant 43 days to 1 year before death, or unknown if pregnant within the past year (7). However, delays in states’ adoption of the new pregnancy question created problems for maternal mortality analysis, as data from states using the standard pregnancy question were not comparable with data from states with no pregnancy question or a non-standard pregnancy question (7,8).

A previous paper provided estimates of US maternal mortality trends from 2000–2014 after adjustment for differences in the use of the pregnancy question among states (8). This paper extends the previous analysis by analyzing trends in maternal mortality for 27 states and Washington DC for the most recent 5-year period (2008–2009 to 2013–2014), by maternal age, race and ethnicity, and for detailed causes of death. The purpose was two-fold: 1) to identify trends and at-risk populations to assist in targeting prevention efforts; and 2) to begin to evaluate the data quality of vital statistics maternal mortality data, since this data has not been widely used.

Materials and Methods

We use the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of maternal death as the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes (9). This is the definition used for international maternal mortality comparisons. Late maternal deaths are pregnancy-related deaths that occurred from 43 days to 1 year after the end of pregnancy (9).

United States maternal mortality data used for national and international comparisons are based on information reported on death certificates filed in state vital statistics offices, and subsequently compiled into national data through the National Vital Statistics System (6). Maternal mortality data used in this observational study were derived from the detailed mortality data files publically available from the National Center for Health Statistics, and also available through CDC-WONDER (10–11). Physicians, medical examiners or coroners are responsible for completing the medical portion of the death certificate, including the cause of death. From 1999 to the present, cause-of-death data in the United States have been coded according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10) (6). Maternal deaths are denoted by codes A34, O00-O95, O98-O99, while late maternal deaths are denoted by codes O96-O97 (7, 9). Maternal deaths are further subdivided into direct and indirect obstetric deaths (9). Direct obstetric deaths are deaths resulting from obstetric complications of the pregnant state (pregnancy, labor and puerperium), from interventions, omissions, incorrect treatment, or from a chain of events resulting from any of the above (ICD-10 codes A34, O00-O92) (9). Indirect obstetric deaths are deaths resulting from previous existing disease, or disease that developed during pregnancy and which was not the result of direct obstetric causes, but which was aggravated by the physiological effects of pregnancy (O98-O99) (9). Deaths of unknown cause (O95) are not classified as either direct or indirect causes. In the United States, all death certificates of women identified by the pregnancy checkbox question as being pregnant at the time of death or within 42 days prior to death are coded as maternal deaths, except for deaths due to external causes of injury (i.e. accidents, homicide, suicide) (12–13).

We include the complete population of maternal deaths and live births for the 27 states and the District of Columbia that had adopted the US standard pregnancy question by January 1, 2008 (8). Although revised to the U.S. standard question in 2006, Texas data will be examined in a separate paper, as it exhibited very different trends than the other states (8). Data from 2008–2009 was compared with data from 2013–2014, to analyze changes in maternal death during the most recent 5-year period. We analyzed data by maternal age (by 5-year age groups and for women aged <40 and ≥40 years) race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic) and for detailed causes of death. The <.01% of records with missing age were excluded. Information on race was missing for <.04% of records and was imputed by the National Center for Health Statistics using procedures described elsewhere (6). Unknown cause of death (0.4% of cases in this study) is coded to a separate category (O95) and included as a separate category in the analysis.

We also analyzed trends for a grouping of non-specific “other” and unknown causes of death, including “Other specified pregnancy-related conditions” (O26.8), “Unknown cause” (O95) and “Other specified diseases and conditions complicating pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium” (O99.8) (14). These categories are general categories where deaths that do not easily fit into the ICD maternal mortality coding rubric are classified; thus it is more difficult from a clinical perspective to determine the specific cause of death for these cases. Two-year averages of data were used to increase the number of cases available for detailed analysis, and to increase the reliability of the resulting estimates. As maternal death is a rare event, the number of cases was not sufficient to support individual state analysis, particularly when stratified by demographic characteristics and by cause of death. The 27-states and the District of Columbia included 45% of all U.S. births in 2008–2009 and in 2013–2014. Maternal mortality rates were computed per 100,000 live births. A two-proportion z-test was used to test for statistical significance in trends from 2008–2009 to 2013–2014 (15).

Finally, as a recent study found evidence of possible over-identification of pregnancy with the pregnancy checkbox (16), we did a sensitivity analysis to assess the potential impact of a 0.5%, 1%, and 1.5% level of over-reporting of pregnancy status with the pregnancy checkbox. We computed the number of non-maternal deaths to women from natural causes (excluding accidents, homicide and suicide) by 5-year age groups, and estimated how different levels of incorrect reporting of these deaths as maternal deaths would impact maternal mortality rates by age. The study was exempt from requiring institutional review board approval since the study was based on de-identified, aggregated data from U.S. government public-use data sets.

Results

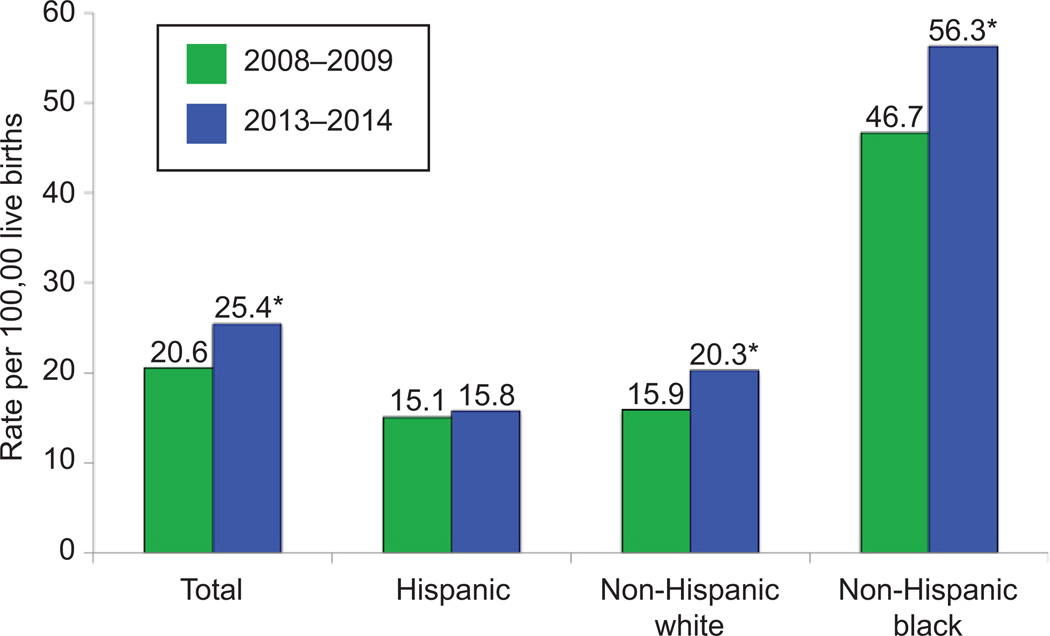

The study population included 1,687 maternal deaths and 7,369,966 live births. The maternal mortality rate increased by 23% during the latest 5-year period in the District of Columbia and the 27 states with the revised pregnancy checkbox item. The maternal mortality rate rose from 20.6 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2008–2009 to 25.4 in 2013–2014 (Figure 1) (p<.001).

Figure 1.

Maternal mortality rates by race and ethnicity, 27 states and Washington, DC, 2008–2009 and 2013–2014. The 27 states include Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, Montana Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. *Statistically significant difference between rates at P<.05 level.

Women aged 40 years and over had the highest maternal mortality rates, and the largest percent increase was from 2008–2009 to 2013–2014 (Table 1). In 2008–2009, the maternal mortality rate for women aged ≥40 was 141.9 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, 10 times the rate of 14.1 for women aged 25–29, the lowest risk group (p<.001). By 2013–2014, the maternal mortality rate for mothers aged ≥40 was 269.9, 18 times the rate of 14.7 for 25–29 year olds (p<.001). This represents a 90% increase in the maternal mortality rate for mothers aged ≥40 during a 5-year period (p<.001). Although rates appeared to decline slightly for women under 25, and increase slightly for women aged 25–39, none of these changes were statistically significant. In fact, there was no statistically significant difference in the maternal mortality rate for women <40 across these two time periods (p=.38). The increase for ≥40 age group (p<.001) accounted for all of the overall increase in maternal deaths between the two time periods.

Table 1.

Maternal Deaths and Mortality Rates by Maternal Age

| Maternal age (years) |

2008–2009 |

2013–2014 |

Percent Change 2008–2009 to 2013–2014 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal deaths |

Births | Rate | Maternal deaths |

Births | Rate | ||

| Total | 780 | 3793403 | 20.6 | 907 | 3576563 | 25.4 | 23.3*** |

| <40 | 632 | 3689111 | 17.1 | 618 | 3469489 | 17.8 | 4.1 |

| <20 | 52 | 367766 | 14.1 | 26 | 225902 | 11.5 | −18.4 |

| 20–24 | 141 | 923577 | 15.3 | 119 | 798503 | 14.9 | −2.6 |

| 25–29 | 152 | 1080462 | 14.1 | 152 | 1031402 | 14.7 | 4.3 |

| 30–34 | 156 | 877975 | 17.8 | 177 | 963582 | 18.4 | 3.4 |

| 35–39 | 131 | 439331 | 29.8 | 144 | 450100 | 32.0 | 7.4 |

| ≥40 | 148 | 104292 | 141.9 | 289 | 107074 | 269.9 | 90.2*** |

Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, Montana Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming

p ≤ 0.001

When examined by race and ethnicity, (Figure 1) the maternal mortality rate increased by 28% for non-Hispanic white women, from 15.9 in 2008–2009 to 20.3 in 2013–2014 (p<.001). For non-Hispanic black women, the rate increased from 46.7 in 2008–2009 to 56.3 in 2013–2014 – an increase of 20% (p=.02). The maternal mortality rate for Hispanic women did not change significantly (15.1 in 2008–2009 and 15.8 in 2013–2014).

During both time periods, the maternal mortality rate for non-Hispanic black women was nearly 3 times the rate for non-Hispanic white women. In contrast, rates for Hispanic women were similar to those for non-Hispanic white women in 2008–9. However, by 2013–2014, the rate for Hispanic women was 22% lower (p=.02) than for non-Hispanic white women, due mostly to a large increase for non-Hispanic white women. When examined by maternal age, we found that almost all of the increase in maternal mortality for non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black women was among women aged ≥40 (data not shown).

From 20082009 to 2013–2014, maternal mortality rates increased by 19.7% for direct obstetric causes (p=.003), and by 56.7% for indirect obstetric causes (p<.001) (Table 2). Direct obstetric causes accounted for 2/3 (65.6%), and indirect causes 1/3 (32.4%) of maternal deaths in 2013–14. When the subcategories of direct obstetric deaths were examined, the only significant increases were for diabetes mellitus in pregnancy, from a rate of 0.5 to 1.0 per 100,000 (p<.05), and for Other specified pregnancy-related conditions (O26.8), from a rate of 3.4 to 5.9 (p<.001). The sub-total category “Other obstetric complications” (which includes the two categories listed above) also showed an increase, but once the non-specific (O26.8) category was subtracted out, the rate was unchanged at 5.6 during both time periods. The increase of 82 maternal deaths in the non-specific O26.8 category accounted for almost two-thirds of the overall increase in maternal deaths (127) between 2008–2009 and 2013–2014.

Table 2.

Maternal and Late Maternal Deaths and Mortality Rates by Cause of Death

| Underlying cause of death | 2008–2009 |

2013–2014 |

Percent change 2008-9 to |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent of total |

Percent of total |

||||||

| Number of deaths |

maternal deaths |

Rate~ | Number of deaths |

maternal deaths |

Rate~ | 2013–14 | |

| Total maternal deaths (during pregnancy or within 42 days after the end of pregnancy) (A34, O00-O95, O98-O99) | 780 | 100.0 | 20.6 | 907 | 100.0 | 25.4 | 23.3*** |

| Total direct obstetric causes (A34, O00-O92) | 527 | 67.6 | 13.9 | 595 | 65.6 | 16.6 | 19.7** |

| Pregnancy with abortive outcome (O00-O07) # | 51 | 6.5 | 1.3 | 35 | 3.9 | 1.0 | −27.2 |

| Ectopic pregnancy (O00) | 29 | 3.7 | 0.8 | 23 | 2.5 | 0.6 | −15.9 |

| Hypertensive disorders (O10-O16) # | 71 | 9.1 | 1.9 | 79 | 8.7 | 2.2 | −8.0 |

| Pre-existing hypertension (O10) | 29 | 3.7 | 0.8 | 32 | 3.5 | 0.9 | 17.0 |

| Eclampsia and pre-eclampsia (O11,O13-O16) | 42 | 5.4 | 1.1 | 47 | 5.2 | 1.3 | 18.7 |

| Obstetric Hemorrhage (O20,O43.2,O44-O46,O67,O71.0-O71.1, O71.3-O71.4,O71.7,O72) | 40 | 5.1 | 1.1 | 43 | 4.7 | 1.2 | 14.0 |

| Pregnancy-related infection (O23,O41.1,O75.3,O85,O86,O91) # | 23 | 2.9 | 0.6 | 23 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 6.1 |

| Puerperal sepsis (O85) | 16 | 2.1 | 0.4 | 12 | 1.3 | 0.3 | −20.5 |

| Other obstetric complications (O21-O22,O24-O41.0, O41.8-O43.1, O43.8-O43.9,O47--O66,O68-O70,O71.2, O71.5, O71.6, O71.8,O71.9, O73-O75.2,O75.4-O75.9,O87-O90,O92) # | 342 | 43.8 | 9.0 | 413 | 45.5 | 11.5 | 28.1*** |

| Diabetes mellitus in pregnancy (O24) | 20 | 2.6 | 0.5 | 34 | 3.7 | 1.0 | 80.3* |

| Liver disorders in pregnancy (O26.6) | 27 | 3.5 | 0.7 | 30 | 3.3 | 0.8 | 17.8 |

| Other specified pregnancy-related conditions (O26.8) | 130 | 16.7 | 3.4 | 212 | 23.4 | 5.9 | 73.0*** |

| Obstetric embolism (O88) | 41 | 5.3 | 1.1 | 42 | 4.6 | 1.2 | 8.6 |

| Cardiomyopathy in the puerperium (O90.3) | 44 | 5.6 | 1.2 | 51 | 5.6 | 1.4 | 22.9 |

| Total indirect causes (O98-O99) # | 202 | 25.9 | 5.3 | 294 | 32.4 | 8.2 | 54.4*** |

| Mental disorders and diseases of the nervous system (O99.3) | 15 | 1.9 | 0.4 | 22 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 55.6 |

| Diseases of the circulatory system (O99.4) | 65 | 8.3 | 1.7 | 79 | 8.7 | 2.2 | 28.9 |

| Diseases of the respiratory system (O99.5) | 21 | 2.7 | 0.6 | 18 | 2.0 | 0.5 | −9.1 |

| Other specified diseases and conditions (O99.8) | 85 | 10.9 | 2.2 | 141 | 15.5 | 3.9 | 75.9*** |

| Obstetric death of unspecified cause (O95) | 51 | 6.5 | 1.3 | 18 | 2.0 | 0.5 | −62.6*** |

| Late maternal causes (43 days-1 year after the end of pregnancy) (O96-O97) | 168 | 4.4 | 246 | 6.9 | 55.3*** | ||

Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, Montana Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

Rate per 100,000 live births. Denominators were 3,793,403 births in 2008–9 and 3,576,563 births in 2013–14

0.01 < p-value ≤.05;

0.001 < p-value ≤0.01,

p-value ≤ 0.001

Individual cause-of-death categories are shown separately under subtotals when they contained a substantial number of deaths (generally 10 or more in both time periods). However residual categories are not shown to save space and promote clarity of presentation

Indirect obstetric causes increased by 54.4% from 20082009 to 20132014 (p<.001). However, the only specific sub-category under Indirect obstetric causes that showed a statistically significant increase was “Other specified diseases and conditions” (O99.8), which increased by 75.9% during the 5-year period (p<.001) and accounted for over one-third of the increase in maternal deaths between the two time periods.

To further examine data quality issues, we developed a grouping of maternal deaths assigned to non-specific ‘other’ causes, combining other specified pregnancy-related conditions (O26.8), other specific diseases and conditions (O99.8) and obstetric death of unspecified cause (O95). Maternal mortality rates for this cause-of-death grouping increased by 47.9% from 7.0 in 2008–9 to 10.4 in 2013–14 (p<.001) (Table 3). There was an overall increase of 127 maternal deaths across the two time periods, and the non-specific causes accounted for 105 (83%) of them. When this group is subtracted out from the total maternal deaths, the increase in maternal mortality between 2008–2009 (13.5 per 100,000) and 2013–2014 (15.0 per 100,000) was not statistically significant (p=.10).

Table 3.

Assessing the Effects of Non-Specific Causes on Maternal Deaths and Mortality Rates by Cause of Death

| Underlying cause of death (ICD-10 category) |

2008–9 |

2013–14 |

Percent change 2008–9 to 2013–14 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of deaths |

Rate~ | Number of deaths |

Rate~ | ||

| Total maternal (A34, O00-O05, O98-O99) | 780 | 20.6 | 907 | 25.4 | 23.3*** |

| non-specific causes (O26.8, O95, O99.8) | 266 | 7.0 | 371 | 10.4 | 47.9*** |

| Total maternal minus non-specific causes (Remainder) | 514 | 13.5 | 536 | 15.0 | 10.6 |

| Total direct obstetric (A34, O00-O92) | 527 | 13.9 | 595 | 16.6 | 19.7** |

| Other specified pregnancy-related conditions (O26.8) | 130 | 3.4 | 212 | 5.9 | 73.0*** |

| Total direct obstetric minus O26.8 (Remainder) | 397 | 10.5 | 383 | 10.7 | 2.3 |

| Total indirect causes (O98-O99) | 202 | 5.3 | 294 | 8.2 | 54.4*** |

| Other specified diseases and conditions (O99.8) | 85 | 2.2 | 141 | 3.9 | 75.9*** |

| Total indirect causes minus O99.8 (Remainder) | 117 | 3.1 | 153 | 4.3 | 38.7** |

Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, Montana Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

Rate per 100,000 live births. Denominators were 3,793,403 births in 2008-9 and 3,576,563 births in 2013-14.

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ 0.01,

p-value ≤ 0.001

Direct obstetric deaths increased by 19.7% from 2008–2009 to 2013–2014 (p=.003). However, when the non-specific category (O26.8) was subtracted out, the remaining category also did not increase significantly from 2008–9 (10.5 per 100,000) to 2013–14 (10.7 per 100,000) (p=.75) (Table 3).

Indirect obstetric deaths increased by 56.7% from 2008–2009 to 2013–2014. When the non-specific (O99.8) category was subtracted out, in this case, the remaining category still increased by 42.3% from 2008–9 (3.0 per 100,000) to 2013–14 (4.3 per 100,000) p<.01).

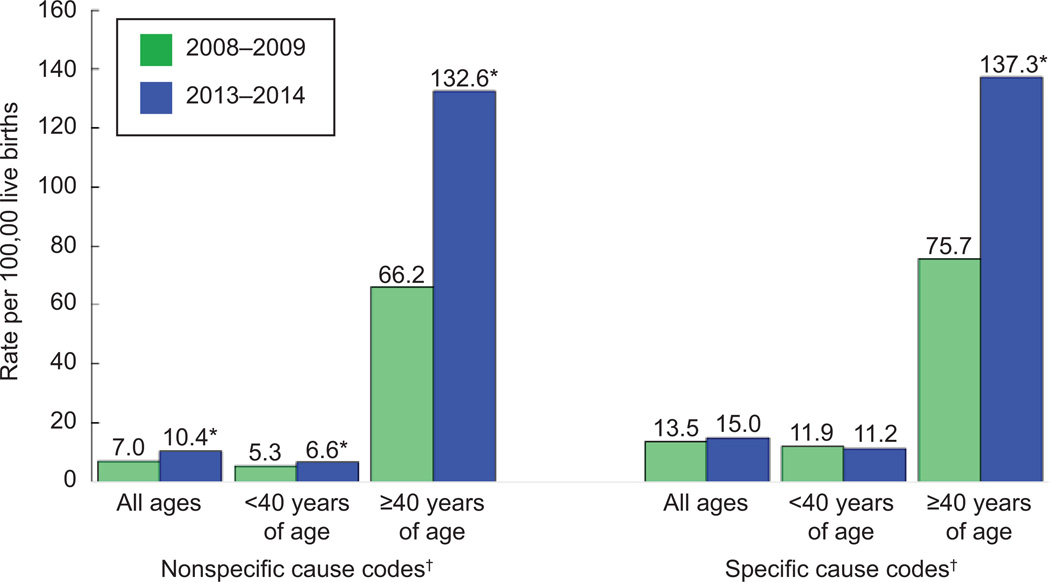

From 2008–9 to 2013–14, maternal mortality rates for women aged ≥40 nearly doubled among both specific and non-specific causes of death. For women <40, maternal mortality rates from non-specific causes increased by 26% during the period, while the rates for specific causes did not change significantly. In 2013–2014, maternal mortality rates from non-specific causes were 20 times higher for women ≥40 than for women <40, while among specific causes, rates were 12 times higher. In fact, for women aged ≥40 one-half of all maternal deaths were due to non-specific causes in 2013–2014. (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Maternal mortality rates by age for specific and nonspecific causes of death, 27 states and Washington, DC, 2008–2009 and 2013–2014. The 27 states include Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, Montana Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. *Statistically significant difference between rates at P<.05 level. ƗNonspecific cause of death codes are O26.8, O95, O99.8; specific codes are all others combined.

Finally, we did a sensitivity analysis to model the effect on maternal mortality rates of different levels of possible over-reporting of pregnancy or postpartum status with the pregnancy checkbox (Table 4). For example, we found that a 1% over-reporting of pregnancy or postpartum status increased reported maternal mortality rates by 14–23% for women in their twenties and early thirties. In contrast, the maternal mortality rate for women aged 40–54 more than tripled (232% increase) with a 1% false positive rate.

Table 4.

Sensitivity Analysis of Possible Effects of 0.5%, 1%, and 1.5% Overreporting of the Pregnancy Checkbox on Maternal Mortality Rates

| Age (years) | Number of maternal deaths |

Number of female deaths from natural causes (excludes maternal deaths) |

Number of maternal deaths with 0.5% false positives added to total |

Percent increase in MMR with 0.5% false positive rate |

Number of maternal deaths with 1% false positives added to total |

Percent increase in MMR with 1% false positive rate |

Number of maternal deaths with 1.5% false positives added to total |

Percent increase in MMR with 1.5% false positive rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 907 | 82,572 | 1,320 | 45.5 | 1,733 | 91.0 | 2,146 | 136.6 |

| <40 | 618 | 15,553 | 696 | 12.6 | 774 | 25.2 | 851 | 37.8 |

| 15–19 | 26 | 929 | 31 | 17.9 | 35 | 35.7 | 40 | 53.6 |

| 20–24 | 119 | 1,619 | 127 | 6.8 | 135 | 13.6 | 143 | 20.4 |

| 25–29 | 152 | 2,568 | 165 | 8.4 | 178 | 16.9 | 191 | 25.3 |

| 30–34 | 177 | 4,092 | 197 | 11.6 | 218 | 23.1 | 238 | 34.7 |

| 35–39 | 144 | 6,345 | 176 | 22.0 | 207 | 44.1 | 239 | 66.1 |

| 40–54 | 289 | 67,019 | 624 | 115.9 | 959 | 231.9 | 1,294 | 347.8 |

MMR= maternal mortality rate

Discussion

The maternal mortality rate increased by 23% from 2008–2009 to 2013–2014 for a group of 27 states and the District of Columbia that used the U.S. standard pregnancy question on their death certificates. From 2008–2009 to 2013–2014, the only significant increases in maternal mortality rates by maternal age groups were for women aged ≥40 years. For these women, maternal mortality rates in 2013–2014 were 18 times higher than for women aged 25–29 years, the lowest risk group. In contrast, the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths in Great Britain found maternal mortality rates for women aged ≥40 to be 3–4 times higher than for women aged 25–29 (17). About 1/3 of maternal deaths in 2013–2014 were to women aged ≥40 years, compared to just 3% of live births, suggesting either a much greater mortality risk for women ≥40 or, more likely given this analysis, possible over-reporting of maternal deaths to older women.

Non-specific causes of death increased by 48% from 2008–2009 to 2013–2014, and accounted for 83% of the total increase in maternal mortality. In contrast, there was no significant increase among specific causes either for total maternal deaths or for direct obstetric causes, although indirect obstetric causes still increased. Large increases in maternal mortality rates for older women and among non-specific causes suggest possible data quality problems that may be worsening over time.

Using a checkbox question to report on rare events, such as maternal mortality, can be problematic as the checkbox might occasionally be inadvertently checked even if the woman is not pregnant or postpartum. The accuracy of the checkbox information is critical because identification of a death as maternal or non-maternal in US vital statistics data is based almost entirely on the checkbox information. The current coding rules are that unless the cause of death is an accident, suicide, or homicide, if the pregnancy or post-partum within 42 days checkbox is checked, the record is coded as a maternal death, regardless of what is written in the cause-of-death section (12–13). This puts tremendous pressure on the pregnancy question as almost the sole determinant of whether the death is maternal or non-maternal. However, until recently, there has been little quality control done on this data item.

We modeled the potential impact of over-reporting of pregnant or postpartum status with the pregnancy checkbox on maternal mortality rates. We found that a 1% false positive rate increased reported maternal mortality rates by 26% for women <40, but more than tripled them (232% increase) for women aged 40–54. When compared to younger women, women aged 40–54 years have higher death rates and much lower pregnancy rates, making the effect of false positives much larger for these women.

US coding practices for maternal deaths vary somewhat from those used in other countries. Although the ICD-10 recommends the use of a pregnancy checkbox, not all countries have adopted it, which can affect maternal mortality comparisons (8, 18). Also, recent WHO publications include suicides as maternal deaths, due to the possible etiologic link with depression (19, 20). Countries also vary in what are considered “incidental causes” in the maternal mortality definition. For example, in Great Britain, deaths from non-hormonally dependent, non-reproductive cancers are considered to be incidental and probably pre-existing and are not classified as maternal deaths (21). Due to confusion over identifying “incidental” causes, beginning in 2016 WHO recommended adding a second pregnancy question, asking if the pregnancy contributed to the death (22), however, there are currently no plans to adopt this question in the United States.

Even if much of the reported increase is due to over-reporting, our core findings reflect several reasons for concern for U.S. policymakers and practitioners. First, even if we examine only direct causes of maternal mortality for mothers of all ages (15.0 per 100,000), or just women <40 years for any cause (17.8), these rates are much higher than for other industrialized countries (23). For example, the 2014 maternal mortality rate was 3.9 in the United Kingdom, 3.5 in France, and 2.2 in Sweden (23). Second, even limiting the analysis to women <40 or deaths from direct causes, we find the mortality rate is not decreasing, in contrast to most other countries (24–26). In 1990, the United Nations named maternal mortality reduction as a Millennium Development Goal (24), leading to an unprecedented effort to reduce maternal mortality worldwide. Maternal mortality decreased by 44% worldwide from 1990–2015, including a 48% decline among developed regions (25). In contrast, the US maternal mortality rate has not improved and appears to be increasing. (8).

The US vital statistics system provides useful information on maternal mortality. However, high and increasing maternal mortality rates for older mothers and among non-specific causes of death suggest possible data problems. Quality improvement efforts need to focus on improving the quality and validity of the pregnancy checkbox data. Periodic validation studies, and the implementation of data quality checks at both the state and national level are essential to improving reporting. State and Federal agencies should provide training to persons who complete death certificates, which emphasizes the importance of correct reporting of the pregnancy checkbox information. A percentage of records, including 100% of records for women ≥40 or coded to non-specific causes, should be routinely queried back to the certifier to confirm the fact of pregnancy. Given concerns about over-reporting with the pregnancy checkbox, it is illogical to continue to use it as the sole means of identifying maternal deaths. Further identifying and excluding incidental causes of death, as well as changes to coding to decrease the near-exclusive reliance on the checkbox to identify maternal deaths might improve data quality. Finally, the recent growth in state maternal mortality review committees can improve data quality (27), but only if information from maternal mortality reviews is used to update vital statistics information on the cause and circumstances of death.

Acknowledgments

Marian MacDorman’s work received partial funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Center for Child Health and Human Development grant R24-HD041041, Maryland Population Research Center.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Each author has indicated that he or she has met the journal’s requirements for authorship.

References

- 1.Amnesty International. Deadly delivery: The maternal health care crisis in the USA. London: Amnesty International Publications; 2010. [Accessed Nov. 1, 2016]. Available at: http://www.amnestyusa.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/deadlydelivery.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2013 - Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank and the United Nations Population Division. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kassenbaum NJ, Bertozzi-Villa A, Coggershall MS, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384(9947):980–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60696-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunt P, Bueno de Mesquita J. University of Essex Human Rights Centre. New York, New York: United Nations Population Fund; 2010. Reducing maternal mortality – the contribution of the right to the highest attainable standard of health. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Global Burden of Disease 2015 Maternal Mortality Collaborators. Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1775–1812. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31470-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, Tejada-Vera B. National vital statistics reports vol 65 no 4. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. Deaths, Final data for 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoyert DL. Maternal mortality and related concepts. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2007;3(33) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Cabral H. Morton Recent increases in the U.S. maternal mortality rate: Disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):447–455. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, tenth revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed November 1, 2016];Detailed Mortality File 1999-2014 on CDC WONDER Online data base. Available from: http://wonder.cdc.gov/mortSQL.html.

- 11.National Center for Health Statistics. Vital statistics data available online. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; [Accessed November 1, 2016]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/VitalStatsOnline.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Instructions for classifying the underlying cause of death, ICD-10, 2016. National Center for Health Statistics, Instruction Manual Part 2a. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. [Accessed November 16, 2016]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/instruction_manuals.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Instructions for classifying the multiple causes of death, ICD-10, 2016. National Center for Health Statistics, Instruction Manual Part 2b. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. [Accessed November 16, 2016]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/instruction_manuals.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Creanga AA, Callaghan WM. Letter Re: MacDorman et al. Recent increases in the U.S. maternal mortality rate. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001831. [In press] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathews TJ, MacDorman MF, Thoma ME. National vital statistics reports vol 64 no 9. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. [Accessed November 16, 2016]. Infant mortality statistics from the 2013 period linked birth/infant death data set. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr64/nvsr64_09.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baeva S, Archer NP, Ruggiero K, Hall M, Staff J, et al. Maternal mortality in Texas. Am J Perinatol. 2016 doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1595809. (published ahead of ptint) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knight M, Tuffnell D, Kenyon S, Shakespeare J, Gray R, Kurinczuk J, editors. Saving lives, improving mothers’ care: Surveillance of maternal deaths in the UK 2011-13 and lessons learned to inform maternal care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2009-13. Oxford, England: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit; [Accessed November 17, 2016]. Available at: https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/mbrrace-uk/reports. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horon H, Cheng D. Enhanced surveillance for pregnancy-associated mortality – Maryland, 1993–1998. JAMA. 2001;285(11):1455–1459. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.11.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. The WHO application of ICD-10 to deaths during pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium: ICD-MM. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knight M, Nair M, Brocklehurst P, Kenyon S, Neilson J, et al. Examining the impact of introducing ICD-MM on observed trends in maternal mortality rates in the UK 2003–2013. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2016:178. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0959-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knight Marian. Personal communication. 2016 Aug 29; [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, tenth revision, Fifth edition, 2016. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. [Accessed December 1, 2016];OECD health statistics. 2016 Available from: http://www.oecd.org/health/health-data.htm.

- 24.United Nations. The Millennium Development Goals Report, 2015. New York: United Nations; 2015. [Accessed December 1, 2016]. Available at: http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20rev%20(July%201).pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015 – Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, and the United Nations Population Division. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graham W, Woodd S, Byass P, Filippi V, Gon G, et al. Diversity and divergence: the dynamic burden of poor maternal health. Lancet, Maternal Health 2016 suppl. 2016 Sep; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31533-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodman D, Stampfel C, Creanga AA, Callaghan WM, et al. Revival of a Core Public Health Function: State- and Urban-Based Maternal Death Review Processes. Journal of Women’s Health. 2013;22(5):395–398. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]