Abstract

Background

Much is unknown about changes that occur in the brain in the years preceding the cognitive and functional impairment associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). This period before mild cognitive impairment is present has been referred to as preclinical AD, and is thought to begin with amyloid-beta deposition and then progress to neurodegeneration and functional brain circuit alterations. Prior studies have shown that there is increased medial temporal lobe activation on functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) early in the course of mild cognitive impairment. However, it is unknown whether this altered fMRI activity precedes cognitive impairment. The purpose of this study is to address this question using Pittsburgh Compound-B (PiB) imaging and fMRI in a sample of cognitively normal older adults.

Methods

Forty-four cognitively normal older adults underwent both PiB imaging and fMRI with a face-name memory task: 21 were classified as PiB(+) and 23 were PiB(−). Additionally, thorough cognitive and neuropsychological test batteries were administered outside the scanner. The main outcome measure in this study is fMRI activation in the medial temporal lobe during a face-name memory-encoding task.

Results

PiB(+) subjects showed higher fMRI activation during the memory task in the hippocampus relative to PiB(−) participants.

Conclusions

The increased medial temporal lobe activation in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, observed in this study, may serve as an early biomarker of neurodegeneration. Future studies are needed to clarify whether this functional biomarker can stratify Alzheimer’s Disease risk among PiB(+) older adults.

Keywords: Neuroimaging, amyloid-beta, PiB, memory, fMRI, Alzheimer’s Disease

1. Introduction

Much is unknown about changes that occur in the brain in the years leading up to the onset of cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Recent studies have found patterns of medial temporal lobe (MTL) brain activation unique to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD using a memory task during fMRI. The MTL is comprised of the hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, perirhinal cortex, and parahippocampus; and is integral to the processing of long-term memories (1, 2). Compared to elderly control subjects, individuals with MCI — particularly those with early mild impairments — show hyperactivation in components of the MTL whereas those with AD show hypoactivation (3). In addition, cognitively intact carriers of the Apolipoprotein-E ε4 allele also show increased activation during the same memory task compared to those without the allele (3). This series of findings (increased activation in those at risk, increased activation with early MCI, and decreased activation with AD) supports the compensation model of AD (4). Increased activation is thought to compensate for loss of brain integrity in order to complete a cognitive task (seen as hyperactivation), while AD subjects no longer have the capacity to compensate and cannot successfully complete the task (seen as hypoactivation).

The progression of biomarkers in AD is hypothesized to begin with amyloid-beta (Aβ) deposition, proceeds to progressive neurodegeneration and functional neural circuit changes, and leads to the cognitive and behavioral symptoms of AD(5, 6). The period of time between the first detectable Aβ deposits and cognitive dysfunction, which varies greatly between individuals, is often referred to as preclinical AD (7). Twenty to 50% of cognitively normal elderly individuals (depending on age and APOE genotype) show early evidence of Aβ deposition, consistent with presumed preclinical AD (8–12).

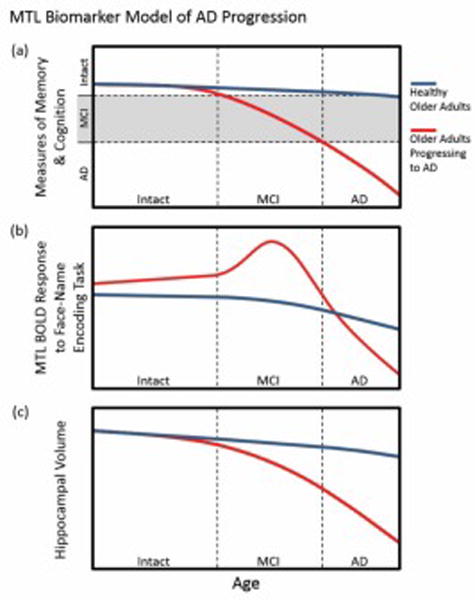

The mechanism by which early Aβ deposition explains the altered functioning of the MTL memory circuit in cognitively normal individuals is unclear. Aβ has neurotoxic (excitatory) effects (13, 14) within the MTL, although these effects have not been causally connected to impairment of the memory circuit. The hippocampus and neocortex are selectively vulnerable to excitotoxic insult (15), thus it is plausible that neurotoxic effects of Aβ upon the MTL lead to loss of structural integrity of the memory circuit, and subsequent cognitive decline. We hypothesize a three-stage biomarker model for AD (Figure 1) based upon the idea that compensatory hyperactivation may maintain homeostasis within an MTL burdened by an excitotoxic cascade (associated with Aβ). The model is based upon studies of MTL activity using adaptations of a face-name memory task (16). In the first stage, preclinical-AD is characterized by compensatory hyperactivation in the MTL (Figure 1b) that may be sufficient to offset Aβ neurotoxicity, thus preserving markers of structural integrity (Figure 1c) and function (Figure 1a) of the memory circuit. This first stage of our model is supported by Huijbers et al (2014) (17). Their study of 48 cognitively intact older adults, found that Aβ-positive older adults (n=24), when compared to Aβ-negative older adults (n=24), had greater activation in the entorhinal cortex during an event-related face-name encoding task. There were no group differences in memory, hippocampal volume, or hippocampal activation. Further evidence of our model comes from an event-related face-name repetition encoding task by Vannini et al. Aβ-positivity in older adults was positively associated with right hippocampal activity (18). In the second stage, transition from preclinical-AD to MCI may be caused by the inability for compensatory hyperactivation to offset excitotoxic damage to the MTL memory circuit. Compensatory hyperactivation would reach a maximum during MCI, after which MTL atrophy would lead to decline in MTL activity (Figure 1b). is supported by longitudinal study MCI (19). Huijbers et. al found that Aβ-positivity was associated with greater hippocampal activation during a face-name memory task, smaller hippocampal volumes, and greater cognitive decline. In the third stage, decline from MCI to dementia is characterized by atrophy of the MTL (Figure 1c) (20–22) leading to the precipitous decline of MTL activity (23) (Figure 1b) and cognitive capacity (Figure 1a) characteristic of AD. This third stage of our model is supported by a longitudinal study of adults grouped by baseline scores on the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) by O’Brien et al (2010). They found that the older adults with very mild impairment (CDR=0.5) at baseline demonstrated a longitudinal decline in hippocampal activity during a face-name memory task, while the 21 cognitively intact older adults (CDR=0) experienced no change in hippocampal activity (23). That study supports our model by observing that those with the most rapid cognitive decline had the greatest hippocampal activity at baseline and the greatest two-year decline in hippocampal activation.

Figure 1.

The MTL biomarker model of AD progression. As a function of age, those progressing to AD each have different temporal trajectories with regards to (a) memory and cognition, (b) MTL BOLD response during a face-name encoding memory task, and (c) hippocampal volume. The MTL BOLD response in those progressing to AD is depicted as having a peak during MCI, which represents the compensatory efforts of the MTL.

The understanding of biomarker progression during preclinical AD can lead to earlier diagnosis of impending A. The study of MTL activity by Vannini et al (2012) and Huijbers et al (2014) has reinforced the importance of MTL activity and Aβ-positivity as biomarkers in cognitively intact older adults. Yet, the findings of these studies disagree over what MTL regions are associated with Aβ-positivity, the hippocampus or the entorhinal cortex. Several explanations might account for discrepancies. First, each study used different adaptations of the face-name encoding memory task. Second, uneven ratios of Aβ-positive to Aβ-negative older adults in the study by Vannini et al (8:32) compared to the study by Huijbers et al (24:24) may also play a role. Third, Aβ-positivity was ascribed with different thresholds using different brain regions.

Using PiB PET imaging, fMRI to measure MTL activity during a memory task, and neuropsychological testing, our study aims to add to the limited body of literature that has investigated MTL activity in cognitively intact older adults. We hypothesize that cognitively intact older adults with evidence of significant Aβ [ PiB(+)] will have greater task-based MTL activation than PiB(−) older adults. Because all subjects are cognitively intact, we hypothesize that there will not be significant group differences in hippocampal volume, neuropsychological assessment metrics, and task performance.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

Data were collected from the first 44 recruited cognitively unimpaired subjects that had undergone fMRI and PET imaging. Their mean age was 76.4 years (sd=5.6, Table 1). These subjects were recruited through community advertisements and in a mailing to University of Pittsburgh alumni. Some were recruited from a University registry of studies promoting independence. To participate subjects had to be at least 65 years old, fluent in English, and a minimum of 12 years of education. Exclusionary criteria included: a) diagnosis of MCI or dementia (see below for assessment and adjudication details), b) history of a major psychiatric or neurological condition (e.g., bipolar disorder, major depression within the last 5 years, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, substance abuse); c) an unstable medical condition that could affect cognition d) visual, auditory or motor deficits sufficient to impair ability to perform the tests; e) medications affecting cognitive performance (e.g., benzodiazepines, narcotic analgesics; cholinesterase inhibitors); f) contraindications to MRI such as metal in the body or claustrophobia. The Human Use Subcommittee of the Radioactive Drug Research Committees and the IRB of the University of Pittsburgh approved all studies.

Table 1.

Subject Demographics

| N | Age (mean(SD)) | Gender (%F) | APOE (% with at least one E4 allele)* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Group | 44 | 76.4(5.6) | 73% | 16.3% |

| PiB Groups: | ||||

| PiB(+) | 21 | 76.9(5.5) | 71% | 25.0% |

| PiB(−) | 23 | 76.0(5.7) | 74% | 8.7% |

APOE data was not available for one PiB(+) subject; percentages are based on N=43 for whole group and N=20 for PiB(+)

Participants were given a neuropsychological battery used by the ADRC to rule-out individuals who would meet criteria for MCI (24–26) or dementia (according to DSM-IV)(27). The testing battery included the following domains: (a) memory; (b) visuospatial construction; (c) language; and (d) attention and executive functions. Neuropsychologists, using the following principles as a basis for either MCI or dementia, reviewed the results diagnosis (thus exclusionary for this study): 1) Evidence on at least two different tests of performance below expectations (>1 SD) considering the individual’s age and education, and 2) low test scores were accompanied by reports of concerns about cognition. See Table 2 for a summary of the neuropsychiatric scores by PiB group. There were no significant differences between the means on any of the measures. Further details of the assessment can be found in Nebes et al., 2013 (8).

Table 2.

Neuropsychological test performance by PiB status. WLL = Word List Learning. There were no significant differences between the means on any of the neuropsych measures.

| PiB (−) | PiB (+) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Memory | ||||

| WLL learning trials | 22.1 | 3.3 | 21.9 | 3.1 |

| WLL delayed recall | 7.6 | 2.1 | 7.3 | 1.9 |

| Rey figure immediate recall (max = 24) | 16.9 | 2.9 | 15.7 | 3.7 |

| Rey figure delayed recall (max = 24) | 16.7 | 3.5 | 15.4 | 4.4 |

| Logical Memory Story A immediate recall | 16.3 | 3.4 | 16.5 | 3.9 |

| Logical Memory Story A immediate recall | 15.5 | 3.1 | 16.2 | 4.5 |

| Visuospatial construction | ||||

| Block design (max = 24) | 13.8 | 3.6 | 15.2 | 4.8 |

| Rey figure copy (max = 24) | 19.4 | 2.0 | 19.3 | 2.3 |

| Language | ||||

| Semantic fluency (animals) | 20.2 | 6.4 | 19.2 | 5.1 |

| Letter fluency (FAS) | 46.6 | 15.0 | 44.4 | 14.5 |

| Boston Naming Test (max = 30) | 28.8 | 1.7 | 28.1 | 2.4 |

| Attention and executive functions | ||||

| Trail Making Part A (sec) | 29.8 | 13.7 | 29.1 | 8.4 |

| Trail Making Part B (sec) | 74.8 | 26.2 | 88.6 | 43.1 |

| Digit Symbol | 53.3 | 13.0 | 49.4 | 11.8 |

| Stroop color-word interference | 38.2 | 8.5 | 35.4 | 11.7 |

| Clock drawing (max = 15) | 14.2 | 0.7 | 14.4 | 0.7 |

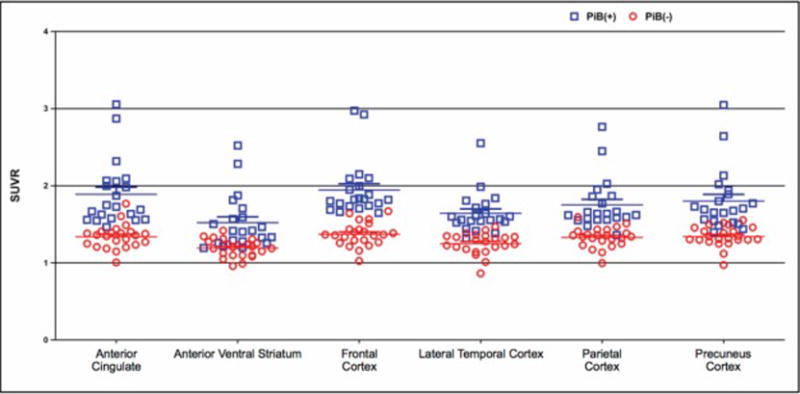

Within six weeks of cognitive testing, subjects completed a PiB-PET scan. PiB radiochemistry was as described in Price et al., 2005 (28). PiB was administered intravenously (12–15 mCi, over 20 sec, specific activity ~1–2 Ci/μmol). PET scanning was performed over 50–70 minutes post-injection. Analysis of the PET data followed the approach previously validated with visual ratings (29). A whole brain standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) was generated using the cerebellar gray matter as the reference region. MRIs were used for co-registration, region of interest definition (28) and for correcting PiB PET data for volume averaging(30). Using sparse k-means clustering (SKM)(29), we defined regional cutoffs for anterior cingulate, anterior ventral striatum, and frontal, lateral temporal, parietal, and precuneus cortex. Any subject with PiB retention values exceeding the cutoff point in any of these six regions was defined as PiB(+).

2.2. Data Collection

Functional MRI data was collected at the University of Pittsburgh Magnetic Resonance Research Center (MRRC) using a 3T Siemens Trio scanner and 12-channel parallel receive coil. A high-resolution, whole-brain sagittal T1-weighted MPRAGE sequence (with GRAPPA of 2) was acquired in axial orientation (TE=2.98, TR=2300, FA=9°, 9 minute sequence, 160 slices, 256X240, 1×1×1.2 mm3). During a memory task (described below), a whole brain (excluding the cerebellum), axial blood oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) sequence was acquired (TR=2 seconds, TE=32 ms, FA=90°, 276 volumes, FOV 256×256, 2×2×4mm3).

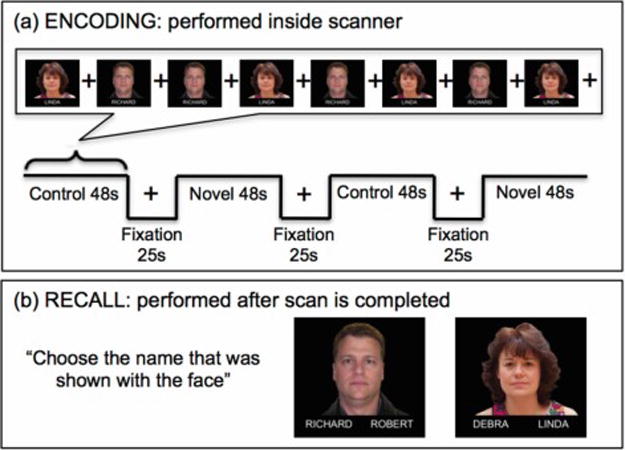

During fMRI scanning, participants performed a face-name memory-encoding task (16) (Figure 2). This is a block=design task that presents face-name pairs. The blocks alternate between familiar (“control”) faces (two faces the subject saw during training prior to the fMRI) with novel faces. While in the scanner, subjects are asked to choose whether the name “fits” the face and to remember the face-name combinations. Subjects are told that the “fit” of the name is meant to aid in encoding. Each run contains four 48s blocks, with each block presenting 8 faces for 5s each, with 1s of fixation. Between each block is a 25s fixation period. Subjects performed two runs, totaling 34 face-name pairs (two familiar and 32 novel pairs.) After the scanning session, participants are shown each of these 34 faces paired with two names, and are asked which name was shown with the face when it was presented in the scanner.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the functional face-name memory encoding (a) and recall (b) task.

2.3. fMRI Data Analysis

The imaging data was preprocessed using SPM8 (motion corrected, co-registered to the MNI template, and smoothed with a 10mm kernel). Robust regression using Weighted-Least-Squares (WLS) SPM toolbox was used to perform a first-level analysis for the fMRI memory task data. Robust Regression is useful to model data that contain outliers since it is based on a weighting technique. The within-subject contrast was the novel>familiar condition, in which the novel blocks (containing only new faces and names) were compared with familiar blocks (containing the same two control pairs). As the MTL is a region that is affected by air susceptibility artifacts, we have checked each subject individual scan for coverage of this region. The subjects included in the analysis had good MTL area coverage.

To verify the efficacy of the face-name task, a one-sample t-test in the whole group was done testing the novel > familiar contrast. To test for fMRI differences between PiB(+) and PiB(−), a voxel-wise analysis was performed as well as a post-hoc analysis using the mean fMRI activity in the MTL. We first created an MTL mask by combining the hippocampus, parahippocampus, entorhinal, and perirhinal cortex using the wfupickatlas toolbox (31). MarsBaR (32) was then used to extract the mean fMRI signal within this cluster. As air susceptibility artifacts affect the MTL, we have also computed temporal signal to noise (tSNR) in this region for each subject and found that the mean tSNR was 87.5 and the 95% confidence interval was [77.9, 97.1]. For each subject, the mean novel>familiar contrast was used to test whether the signal in this region differs between PiB(+) and PiB(−) groups, and follows a compensation pattern of greater activity in PiB(+) subjects, ‘compensating’ for neural deficits.

A secondary analysis was performed using task recall accuracy, which was calculated across all encoding stimuli. Correlations between accuracy and MTL activation by PiB status were used to further explore the compensation model.

2.4. Hippocampus Segmentation

Structural images were automatically skull-stripped using the brain extraction tool (BET) from FSL (33). Using ITK-SNAP these segmentations manually reviewed and corrected to outline the brain (34). Using the image dimension and the number of voxels in the segmentation of the brain, we calculated the total intracranial volume (ICV).

The structural images were then segmented using FIRST (35) generate total hippocampus volume (sum of both hemispheres). This was with total intracranial volume.

3. Results

3.1. PiB Binding

Twenty-one of the participants were defined as PiB(+), and 23 as PiB(−). A scatter-plot of the regional PiB SUVR values is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) retention among cognitively unimpaired older adults classified as PiB(+) (red circles) and PiB(−) (blue circles) broken down by the following regions: anterior cingulate, anterior ventral striatum, frontal cortex, lateral temporal cortex, parietal cortex, and precuneus cortex.

3.2. Functional MRI with Face-name paired associate task

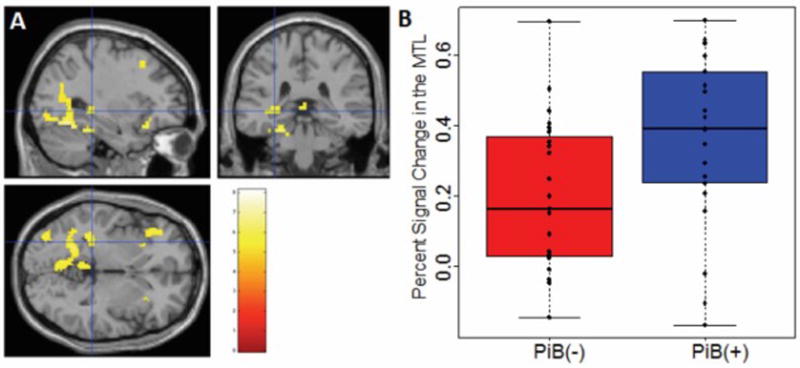

The novel>control contrast in the whole group (regardless of PiB status) was done using a one-sample t-test with the novel versus familiar conditions (level-1 contrast). Results were threshold with a whole brain Family Wise Error (FWE) correction, T(43)>4.97, corrected p<0.05, Figure 4a. As expected, there were significant activations within the hippocampus. This replicates previous findings showing that this task reliably activates the hippocampus (16). Also as expected, there were no significant regions identified in the reverse contrast (control>novel).

Figure 4.

a. Main effect of Novel > Control contrast in the whole group. (T(43)>4.97, FWE corrected p<0.05., cluster=48 voxels, MNI coordinates: −30, −34, −2); b. Box and whisker plot of MTL activation in PiB(−) (red) versus PiB(+) (blue).

To test our hypothesis that cognitively normal PiB(+) subjects have increased activation in the MTL compared to PiB(−) subjects, we extracted the mean fMRI signal within the medial temporal lobe for each individual subject, and performed a t-test between the two groups. See Figure 4b for a plot of the contrast (novel vs. control) in the MTL mask for each subject.

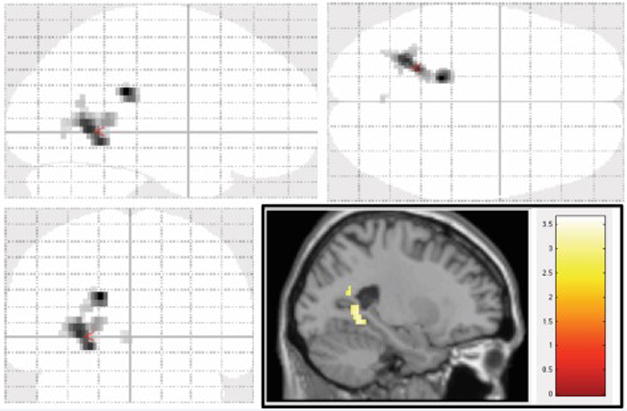

We found a significant difference in contrast (novel vs. control) between PiB(+) and PiB(−) subjects (T(40.38)>2.38, p<0.0222). As expected, PiB(+) subjects showed higher activation in this region during the novel>control contrast. Figure 5 shows a representation of these results; activation shown is PiB(+)>PiB(−) in the main novel>control contrast (T(42)>2.7, p<0.005, uncorrected). Here it is observed that the activation is localized around the medial temporal lobe.

Figure 5.

Voxel-wise analysis of PiB(+) > PiB(−) in the Novel > Control contrast (T(42)>2.7, p<0.005, uncorrected). Figure shows a transparent brain in all three orientations with a sagittal slice inlaid on the bottom right.

Our analysis was adjusted for age (an ANCOVA model was run with the MTL region as our outcome variable and PiB status and age as our independent variables). PiB status remained significant (t(41)=2.30,p=0.0264, β1=0.16 (se=0.07)) in the model containing age. The β1 coefficient indicates the difference in the MTL activation between PiB(+) and PiB(−).

We have also performed an analysis between PiB status and MTL activation while controlling for education. PiB status remained significantly associated with MTL activation (β1=0.15 (se=0.07), t(41)=2.244, p=0.03) after adjusting for the effect of education.

We did not control for gender because there was not a statistical difference in activation. Also, no statistically significant association was found between MTL activation and education (t (42)=−1.57, p=0.12). A two-sample t-test was used to test if there were any differences between the average years of education in PiB(+) versus PiB(−) group. The mean years of education in the PiB(+) was 14.52 (SD=2.52) and for the PiB(−) was 14.00 (SD=2.14). The t-statistic was equal to 0.74 (df=41.8, p=0.46) and 95% confidence interval for the mean difference was equal to (−0.89, 1.94).

There was not a significant difference between PiB groups in memory [as measured with mini-mental state exam (MMSE) (36) and the word recall test], or hippocampal volume. Hippocampal volume was calculated using FIRST, a publicly available validated approach (35) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Hippocampal and memory measurements (mean(SD))

| Hippocampal Voxels | Hippocampal Volume Normalized by ICV | Word Recall Score | Task Accuracy | MMSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PiB(+) | 6723(943) | 0.0039(0.0004) | 21.9(3.1) | 67.3(11.3) | 28.6(1.5) |

| PiB(−) | 6769(799) | 0.0039(0.0005) | 22.1(3.3) | 64.8(10.6) | 28.5(1.6) |

Finally, we did not find a significant relationship between MTL activation and accuracy in the Aβ positive group (r=−0.15 and 95% CI (−0.55, 0.30), p=0.50, df=19). This failure to find a significant association does not disprove the compensation model, but suggests that other models may be more tenable, for instance perhaps the increased MTL activation in this group reflects a prodromal higher level of activation, which allows the individuals to withstand Aβ burden, as suggested in previous PET imaging studies [e.g., Cohen et al., 2009 (37)].

4. Discussion

We found that Aβ-positive older adults have greater activation in the MTL than individuals without evidence of Aβ deposition during a memory task. While both groups were cognitively intact, those individuals with greater Aβ burden had a more robust BOLD response. These findings add to a body of literature investigating the role of MTL activity during memory tasks as a biomarker of preclinical AD. Our study suggests that a greater BOLD response reflect compensation for neurotoxic effects associated with Aβ deposition and allow for successful task completion.

Studies investigating MTL activity in cognitively intact older adults with evidence of Aβ deposition during a face-name memory-encoding task include Huijbers et al (2014) (17) and Vannini et al (2012) (18). Huijbers et al found greater activation in the entorhinal cortex, while Vannini et al found greater activation (persistent activation) in the hippocampus. Our study found that PiB-positivity was associated with increased activity in the MTL. The greater activity was predominantly found in the parahippocampal region of the MTL. Although our findings further characterize the role of MTL activity in preclinical AD, they also emphasize the need to further investigate variable findings within the MTL.

Huijbers, Vannini, and our group each measured activity in the MTL during intentional encoding paradigms. Adaptations of the face-name encoding memory task were unique for each study. Huijbers et al reported hyperactivation of the MTL within PiB(+) subjects as greater task-induced deactivation within the entorhinal cortex (contrast: fixation>task) when presented with face-name pairs. Vannini et al reported hyperactivation of the MTL as the persistent activation of the hippocampus after the repeated presentation of face-name pairs. Specifically, PiB(+) subjects had smaller decreases in hippocampal activation between the first and third presentation of a face-name (18). Our study reported hyperactivation of the MTL within PiB(+) subjects as greater activation predominantly within the parahippocampus when encoding novel face-name pairs relative to familiar pairs.

Increased MTL activation in cognitively intact older adults with Aβ deposition may be a hallmark of preclinical AD. The excitotoxic effects associated with Aβ deposition in preclinical AD may be observed by BOLD fMRI as increased activity. Over time, the accumulated neurotoxic Aβ burden may overwhelm compensatory capacity, leading to loss of structural integrity of the MTL and the progression of cognitive impairment toward AD.

Although this study supports the importance of MTL activation in identifying and measuring the progression of preclinical AD, longitudinal studies are needed to adjudicate the differences among results. The transition between preclinical AD and MCI is when we hypothesize that MTL hyperactivation begins to lose its compensatory effect. At this transition, we hypothesize that MTL activation will increase, while cognitive deficits begin to accrue. A better understanding of the progression of preclinical AD may inform the understanding of the pathogenesis of AD.

While we chose to focus on memory circuits other studies have investigated functional changes in older adults in executive control functioning regions. Studies have found that in these regions, increased activation is significantly associated with greater accuracy on task (38). The increased activation in this case may also represent compensation for Aβ deposition, decreased structural integrity, and/or dysfunctional neurocircuitry. Resting state fMRI has also been combined with PiB PET to study functional connectivity in the default mode network (DMN). Several groups have found disruption in DMN functional connectivity when comparing high risk/high-Aβ groups with low risk/low-Aβ groups (39). Since there is no performance component during resting-state, it is difficult to relate DMN connectivity to compensation. It may be that the lower functional connectivity in DMN in the high-Aβ group represents the underlying neurodegeneration more faithfully than task-based fMRI, which is also influenced by performance, and possible compensation.

This study is limited by small sample, although the sample size is similar to other fMRI-PiB PET studies (39), the sample totaled 44 subjects: 23 PiB(−) and 21 PiB(+). Studies with larger sample sizes are needed to further investigate functional changes and the theory of compensation in preclinical AD subjects.

This study is part of a larger ongoing study following the cohort longitudinally; future analysis is needed to investigate whether MTL hyperactivation in PiB(+) individuals predicts future cognitive decline. It has been shown that due to the presence of white-matter hyperintensities (WMH) as well as possible atrophy due to aging, older subjects’ structural data does not register to standard anatomical space accurately near the hippocampus/parahippocampus. We have used SPM’s methods to perform this analysis. Our group has shown that the effect of WMH is negligible on the parameter estimates in fMRI analyses (40). However, due to the limited resolution of the fMRI data, the specificity of these procedures becomes less critical.

To conclude, this study found that Aβ-positive cognitively unimpaired individuals have higher activation during memory encoding than those without significant Aβ. This supports that increased MTL activation reflects compensation allowing individuals with higher Aβ burden to maintain high memory performance. Although this result supports the compensation theory, the mechanistic relationship between increased activation and Aβ remain unclear. Is hyperactivation a moderator of the effects of Aβ? That is, among the PiB(+) cognitively intact individuals, would those with increased MTL activation be more likely to maintain normal cognition longer? Future longitudinal studies of Aβ-positive individuals are necessary to test whether MTL activation predicts cognitive decline.

Acknowledgments

Grant support included: P50 AG005133, R37 AG025516, P01 AG025204, 5K23AG038479, and R01 MH076079 from the National Institutes of Health. Biomarker model of AD progression contributed by Christian Agudelo.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest Disclosure:

GE Healthcare holds a license agreement with the University of Pittsburgh based on the technology described in this manuscript. Drs. Klunk and Mathis are co-inventors of PiB and, as such, have a financial interest in this license agreement. GE Healthcare provided no grant support for this study and had no role in the design or interpretation of results or preparation of this manuscript. All other authors have no conflicts of interest with this work and had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Scoville WB, Milner B. Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957;20:11–21. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.20.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lech RK, Suchan B. The medial temporal lobe: memory and beyond. Behav Brain Res. 2013;254:45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickerson BC, Salat DH, Greve DN, et al. Increased hippocampal activation in mild cognitive impairment compared to normal aging and AD. Neurology. 2005;65:404–411. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000171450.97464.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wierenga CE, Bondi MW. Use of functional magnetic resonance imaging in the early identification of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychol Rev. 2007;17:127–143. doi: 10.1007/s11065-007-9025-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jack CR, Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:207–216. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jack CR, Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, et al. Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:119–128. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70299-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2011;7:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nebes RD, Snitz BE, Cohen AD, et al. Cognitive aging in persons with minimal amyloid-beta and white matter hyperintensities. Neuropsychologia. 2013;51:2202–2209. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mintun MA, Larossa GN, Sheline YI, et al. [11C]PIB in a nondemented population: potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67:446–452. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228230.26044.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aizenstein HJ, Nebes RD, Saxton JA, et al. Frequent amyloid deposition without significant cognitive impairment among the elderly. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1509–1517. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.11.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris JC, Roe CM, Xiong C, et al. APOE predicts amyloid-beta but not tau Alzheimer pathology in cognitively normal aging. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:122–131. doi: 10.1002/ana.21843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowe CC, Ellis KA, Rimajova M, et al. Amyloid imaging results from the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study of aging. Neurobiology of aging. 2010;31:1275–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bobich JA, Zheng Q, Campbell A. Incubation of nerve endings with a physiological concentration of Abeta1-42 activates CaV2.2(N-Type)-voltage operated calcium channels and acutely increases glutamate and noradrenaline release. J Alzheimers Dis. 2004;6:243–255. doi: 10.3233/jad-2004-6305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bezprozvanny I, Mattson MP. Neuronal calcium mishandling and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoltenburg-Didinger G. Neuropathology of the hippocampus and its susceptibility to neurotoxic insult. Neurotoxicology. 1994;15:445–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sperling RA, Bates JF, Cocchiarella AJ, et al. Encoding novel face-name associations: a functional MRI study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2001;14:129–139. doi: 10.1002/hbm.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huijbers W, Mormino EC, Wigman SE, et al. Amyloid Deposition Is Linked to Aberrant Entorhinal Activity Among Cognitively Normal Older Adults. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34:5200–5210. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3579-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vannini P, Hedden T, Becker JA, et al. Age and amyloid-related alterations in default network habituation to stimulus repetition. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:1237–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huijbers W, Mormino EC, Schultz AP, et al. Amyloid-beta deposition in mild cognitive impairment is associated with increased hippocampal activity, atrophy and clinical progression. Brain. 2015;138:1023–1035. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jack CR, Jr, Petersen RC, Xu Y, et al. Rates of hippocampal atrophy correlate with change in clinical status in aging and AD. Neurology. 2000;55:484–489. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.4.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jack CR, Jr, Shiung MM, Gunter JL, et al. Comparison of different MRI brain atrophy rate measures with clinical disease progression in AD. Neurology. 2004;62:591–600. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000110315.26026.ef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du AT, Schuff N, Kramer JH, et al. Higher atrophy rate of entorhinal cortex than hippocampus in AD. Neurology. 2004;62:422–427. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000106462.72282.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Brien JL, O’Keefe KM, LaViolette PS, et al. Longitudinal fMRI in elderly reveals loss of hippocampal activation with clinical decline. Neurology. 2010;74:1969–1976. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e3966e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256:183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment - beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med. 2004;256:240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolk DA, Price JC, Saxton JA, et al. Amyloid imaging in mild cognitive impairment subtypes. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:557–568. doi: 10.1002/ana.21598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bell CC. DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;272:828. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Price JC, Klunk WE, Lopresti BJ, et al. Kinetic modeling of amyloid binding in humans using PET imaging and Pittsburgh Compound-B. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:1528–1547. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen AD, Mowrey W, Weissfeld LA, et al. Classification of amyloid-positivity in controls: comparison of visual read and quantitative approaches. Neuroimage. 2013;71:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meltzer CC, Kinahan PE, Greer PJ, et al. Comparative evaluation of MR-based partial-volume correction schemes for PET. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:2053–2065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Burdette JH. Precentral gyrus discrepancy in electronic versions of the Talairach atlas. Neuroimage. 2004;21:450–455. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brett M, Anton J-L, Valabregue R, et al. Region of interest analysis using the MarsBar toolbox for SPM 99. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jenkinson M, Pechaud M, Smith S. BET2: MR-based estimation of brain, skull and scalp surfaces. Toronto, ON: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yushkevich PA, Piven J, Hazlett HC, et al. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: significantly improved efficiency and reliability. NeuroImage. 2006;31:1116–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patenaude B, Smith SM, Kennedy DN, et al. A Bayesian model of shape and appearance for subcortical brain segmentation. NeuroImage. 2011;56:907–922. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen AD, Price JC, Weissfeld LA, et al. Basal cerebral metabolism may modulate the cognitive effects of Abeta in mild cognitive impairment: an example of brain reserve. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14770–14778. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3669-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Venkatraman VK, Aizenstein H, Guralnik J, et al. Executive control function, brain activation and white matter hyperintensities in older adults. Neuroimage. 2010;49:3436–3442. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sperling RA, Laviolette PS, O’Keefe K, et al. Amyloid deposition is associated with impaired default network function in older persons without dementia. Neuron. 2009;63:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karim HT, Andreescu C, MacCloud RL, et al. The effects of white matter disease on the accuracy of automated segmentation. Psychiatry research. 2016;253:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]