ABSTRACT

Type II secretion (T2S) is one means by which Gram-negative pathogens secrete proteins into the extracellular milieu and/or host organisms. Based upon recent genome sequencing, it is clear that T2S is largely restricted to the Proteobacteria, occurring in many, but not all, genera in the Alphaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria, and Deltaproteobacteria classes. Prominent human and/or animal pathogens that express a T2S system(s) include Acinetobacter baumannii, Burkholderia pseudomallei, Chlamydia trachomatis, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Vibrio cholerae, and Yersinia enterocolitica. T2S-expressing plant pathogens include Dickeya dadantii, Erwinia amylovora, Pectobacterium carotovorum, Ralstonia solanacearum, Xanthomonas campestris, Xanthomonas oryzae, and Xylella fastidiosa. T2S also occurs in nonpathogenic bacteria, facilitating symbioses, among other things. The output of a T2S system can range from only one to dozens of secreted proteins, encompassing a diverse array of toxins, degradative enzymes, and other effectors, including novel proteins. Pathogenic processes mediated by T2S include the death of host cells, degradation of tissue, suppression of innate immunity, adherence to host surfaces, biofilm formation, invasion into and growth within host cells, nutrient assimilation, and alterations in host ion flux. The reach of T2S is perhaps best illustrated by those bacteria that clearly use it for both environmental survival and virulence; e.g., L. pneumophila employs T2S for infection of amoebae, growth within lung cells, dampening of cytokines, and tissue destruction. This minireview provides an update on the types of bacteria that have T2S, the kinds of proteins that are secreted via T2S, and how T2S substrates promote infection.

KEYWORDS: Legionella, T2S, type II secretion, Vibrio, animal pathogens, degradative enzymes, human pathogens, plant pathogens, toxins

INTRODUCTION

Secreted proteins have a major role in the pathogenesis of bacterial infections, including important diseases of humans, animals, and plants. In the case of Gram-negative bacteria, there are seven secretion systems (types I, II, III, IV, V, VI, and IX) that mediate the export of “effector” proteins out of the bacterial cell and into the extracellular milieu or into target host cells (1–3). Type II secretion (T2S) was the first such system to be defined, based upon work done in the mid-1980s on pullulanase secretion by Klebsiella oxytoca (4). Further insight into T2S was then gained from the examination of Aeromonas, Pseudomonas, Vibrio, and a few additional members of the gammaproteobacteria (5, 6). Thus, T2S is considered a two-step process; i.e., proteins to be secreted are first carried across the inner membrane (IM) and into the periplasm by the Sec translocon (7) or Tat pathway (8) and then, after folding into a tertiary conformation (and in some instances, undergoing oligomerization), are transported across the outer membrane (OM) by the dedicated T2S apparatus (2). The T2S machinery is made up of 12 “core” proteins, which are denoted here as T2S C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, and O (9, 10). In recent years, there has been remarkable progress toward elucidating the precise structure of the T2S apparatus (2, 11–16). In essence, there are four subcomplexes: (i) an OM “secretin,” which is a pentadecamer of the T2S D protein that provides a pore through the membrane; (ii) an IM platform composed of T2S C, F, L, and M, with T2S C providing a connection to the OM secretin; (iii) a cytoplasmic ATPase, which is a hexamer of T2S E that is recruited to the IM platform; and (iv) a periplasm-spanning pseudopilus which is a helical filament of the major pseudopilin T2S G capped by the minor pseudopilins T2S H, I, J, and K. Finally, T2S O is an IM peptidase that cleaves and methylates the pseudopilins as a prelude to their incorporation into the pseudopilus. Thus, during T2S, protein substrates present in the periplasm are delivered to the T2S apparatus, presumably following their recognition by T2S C and T2S D (17), and then using energy generated at the IM, the pseudopilus acts as a piston or an Archimedes screw to push the proteins through the OM secretin (2). Although recent papers have detailed the structure of the T2S apparatus and the molecular mechanism of secretion (11–15), it has been some time since there was a review focused on the prevalence of T2S and its role in pathogenesis. Hence, this minireview will provide an update on the types of bacteria and pathogens that have T2S, the numbers and kinds of proteins that are secreted via T2S, and how T2S-dependent proteins promote infection.

Prevalence of type II protein secretion systems.

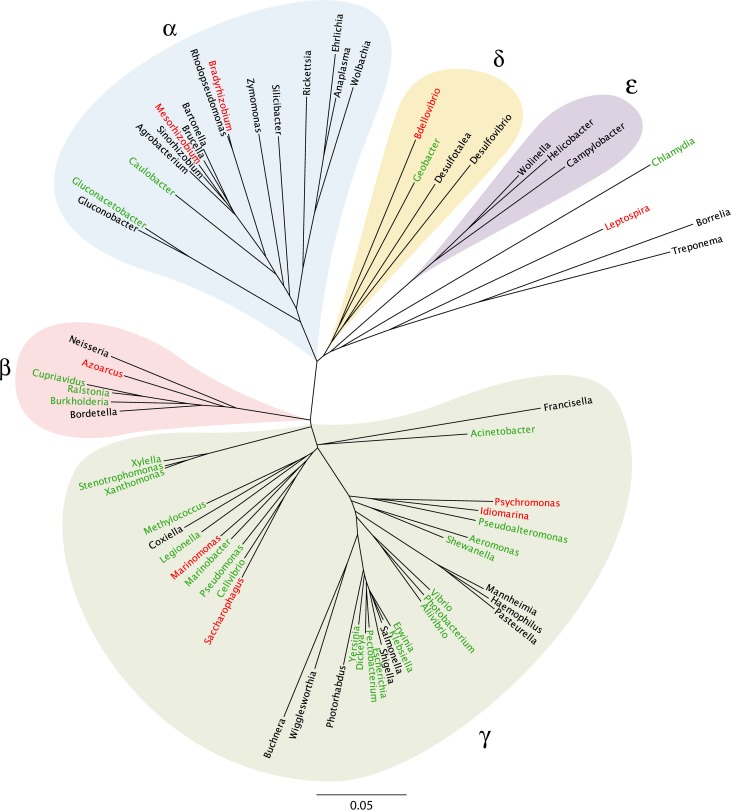

Following the advent of whole-genome sequencing, complete or nearly complete sets of T2S genes (i.e., containing all or almost all of the core constituents, T2S CDEFGHIJKLMO) were identified in 32 genera of Proteobacteria, comprising 22 genera in the gammaproteobacteria, 4 genera each in the alpha- and betaproteobacteria, and 2 genera in the deltaproteobacteria (10, 18). However, T2S genes were absent from 29 other genera of Proteobacteria, including those in the epsilonproteobacteria, indicating that T2S occurs in many, but not all, genera in the phylum Proteobacteria (10). Extending this analysis, a recent study, which defined the full set of T2S genes as one encoding T2S CDEFGHIJKLMNO, identified the system in 360 of the 1,528 Gram-negative genomes examined, with 58%, 45%, 15%, 6%, and 0% prevalence among beta-, gamma-, delta-, alpha-, and epsilonproteobacteria, respectively (19). Figure 1 depicts the distribution of T2S within the evolutionary tree of the Proteobacteria. Looking beyond the Proteobacteria, there are interesting examples of organisms that have a smaller number of T2S-related genes; e.g., Leptospira interrogans of the Spirochaetes encodes T2S CDEFGJKLMO, Chlamydia and Chlamydophila species within the Chlamydiae harbor genes for T2S CDEFG, Rhodopirellula baltica belonging to the Planctomycetes may encode T2S DEFGIKO, Aquifex aeolicus of the Aquificae carries homologs for T2S DEFGO, and Thermotoga maritima of the Thermotogae appears to encode T2S DEFG (10, 19–22). In the case of Chlamydia trachomatis, one of these genes has been linked to protein secretion (20), suggesting that there may be different subclasses of T2S that deviate from the canonical system present in the Proteobacteria. In Synechococcus elongatus belonging to the Cyanobacteria, a T2S E-like gene has been linked to protein secretion; however, this gene may be encoding a component of a type IV pilus rather than a T2S apparatus (19, 23). So far, genome database analyses have failed to reveal any evidence for potential T2S systems in Bacteroidetes, Chlorobi, Fusobacteria, or Verrucomicrobia (10, 19). Thus, despite the fact that T2S is often referred to as the main terminal branch of the general secretory pathway (5, 24, 25), T2S is not, by any means, conserved among Gram-negative (“diderm”) bacteria. Rather, in its canonical form, T2S is largely restricted to the Proteobacteria (Fig. 1). Furthermore, even in the Proteobacteria, T2S, though common, is not universal. Put another way, T2S may be no more prevalent across Gram-negative genera than is type I, III, IV, V, or VI secretion (19). Hence, T2S is best considered a specialized secretion system that a subset of Gram-negative bacteria has evolved to utilize for their growth within the environment or larger hosts. Table 1 shows a comprehensive list of those bacteria in which T2S has been shown by mutational analysis to actually be functional.

FIG 1.

Representative distribution of T2S genes among the Proteobacteria. An unrooted phylogenetic tree of the Proteobacteria and several other bacteria was constructed with aligned 16S rRNA sequences (65, 66) using standard neighbor-joining methods (67, 68). Genus names are denoted at each leaf. Clades representing the alpha-, beta-, gamma-, delta-, and epsilonproteobacteria are identified by the α, β, γ, δ, and ε Greek symbols. The bar represents the number of nucleotide substitutions per site. Bacteria that have been demonstrated to express a functional T2S system are indicated in green. Representative bacteria that have a complete or nearly complete set of T2S genes but for which functionality has not yet been shown are indicated in red. Representative bacteria that lack T2S genes are indicated in black.

TABLE 1.

Secreted proteins, activities, and phenotypes dependent upon T2Sa

| Category and bacterium | Frequent niche/pathogenicityb | Secreted protein(s)/activity(ies) | Phenotype(s) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human and/or animal pathogens (including some rare pathogens, as indicated) | ||||

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Soil, water/pathogen of humans (e.g., pneumonia) | Lipase LipA, phospholipase LipAN, and >10 other secreted proteins identified by proteomics | Survival in neutropenic mouse model, growth in murine pneumonia model | 69, 70 |

| Acinetobacter calcoaceticus | Soil, intestinal tract/pathogen of humans (rare) | Esterase, lipase | Dodecane degradation | 71 |

| Acinetobacter nosocomialis | Soil/pathogen of humans (rare) | Lipases LipA and LipH, protease CpaA, and 57 other secreted proteins identified by proteomics | 72 | |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | Freshwater or brackish water/pathogen of humans (e.g., septicemia) amphibians, and fish | Aerolysin (Act enterotoxin), amylase, DNase, glycerophospholipid cholesterol acyltransferase, protease, S-protein | Cytotoxicity, inflammatory signaling from macrophages and epithelial cells, virulence in mice | 6, 73–78 |

| Aeromonas salmonicida | Freshwater/pathogen of fish (e.g., salmon) | Aerolysin | 79 | |

| Burkholderia cenocepacia | Soil, water/pathogen of humans (lung infection) | Lipase, polygalacturonase, proteases ZmpA and ZmpB | Cleavage of host tissue and defense proteins, virulence in rat lung infection, pathology in Caenorhabditis elegans infection model, virulence in onion infection, survival in macrophages, triggering IL-1β secretion from macrophages | 80–83 |

| Burkholderia pseudomallei | Soil/pathogen of animals and humans (mellioidosis) | Chitinase, deubiquitinase TssM, lipase, phospholipases C, proteases, and ∼40 other proteins identified by proteomics | Virulence in a hamster model, suppression of innate immune response | 28, 84, 85 |

| Burkholderia vietnamiensis | Soil/pathogen of humans (lung infection) | Hemolysin, phospholipase C | 86 | |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | Human genital tract/pathogen of humans (STD, conjunctivitis) | CPAF serine protease, putative glycogen hydrolase | Intracellular growth in epithelial cells, generation of infectious EBs, cleavage of vimentin, lamin-associated protein 1, and host antimicrobial peptides | 20, 87–89 |

| Escherichia coli | ||||

| Enteroaggregative | Intestinal tract/pathogen of humans (diarrhea) | Mucin-degrading metalloprotease YghJ | Degradation of mucous layer | 90 |

| Enterohemorrhagic | Intestinal tract/pathogen of humans (diarrhea, hemolytic-uremic syndrome) | Metalloprotease StcE, protein YodA | Cleaves C1 esterase inhibitor and mucin 7, adherence to epithelia, colonization of the intestine in a rabbit model | 91–93 |

| Enteropathogenic | Intestinal tract/pathogen of humans (diarrhea) | Outer membrane and secreted forms of lipoprotein SslE | Biofilm formation, virulence in a rabbit model of disease | 94, 95 |

| Enterotoxigenic | Intestinal tract/pathogen of humans (diarrhea, cholera-like) | For the beta system, heat-labile (LT) toxin, mucin-degrading protease YghJ, various membrane proteins | Degradation of mucous layer, diarrhea | 90, 96–98 |

| For the alpha system, none identified | 99 | |||

| Extraintestinal | Intestinal tract/pathogen of humans (meningitis) | Putative lipoprotein ECOK1_3385 | Protective antigen in murine sepsis model | 100 |

| Uropathogenic | Intestinal and urinary tracts/pathogen of humans (UTI) | Surface-expressed DraD invasin | Adherence to epithelial cells, survival in murine model of UTI | 101, 102 |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | Soil, freshwater, plants/pathogen of humans (rare) | Surface-associated pullulanase | 103 | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Soil, water, intestinal tract/pathogen of humans (pneumonia) | Pullulanase | Blockade of NF-κB in epithelial cells, growth in the murine lung | 104 |

| Legionella pneumophila | Freshwater, soil/pathogen of humans (pneumonia) | Aminopeptidases LapA and LapB; chitinase ChiA; collagen-like protein Lcl; diacylglycerol lipase; endoglucanase CelA; glucoamylase GamA; glycerophospholipid cholesterol acyltransferase PlaC; lysophospholipase A PlaA; metalloprotease ProA; mono- and triacylglycerol lipase LipA; six novel proteins including NttA, NttB, and NttC; phospholipases C PlcA and PlcB; putative amidase Lpg0264; putative astacin-like peptidase LegP; putative peptidyl-proline cis-trans-isomerase; RNase SrnA; tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase; tartrate-sensitive acid phosphatase Map; triacylglycerol lipase LipB; VirK-like protein Lpg1832 | Virulence in murine pneumonia model (bacterial growth and tissue damage), disruption of PMN function, intracellular growth in macrophages and epithelial cells, recruitment of host GTPase Rab1B to the Legionella-containing vacuole, dampening of cytokine production by host cells, intracellular growth in environmental amoebae, colony morphology and autoaggregation, growth at low temperatures, poly-3-hydroxybutyrate storage, biofilm formation, sliding motility and surfactant production | 26, 46–50, 53–56, 58–61, 105–111 |

| Photobacterium damselae | Marine water/pathogen of fish and humans (rare) | Phospholipase D Dly, pore-forming toxins HlyApl and HlyAch | Virulence in marine fish | 112 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Soil, plants, water/pathogen of humans (pneumonia) | For the Xcp system, alkaline phosphatase PhoA; aminopeptidase PaAP; chitin-binding protein CbpD; DNase PA3909; elastases LasA and LasB; exotoxin A; glycerophosphoryl diester phosphatase GlpQ; lipases LipA and LipC; lipoxygenase LoxA; mucinases; novel proteins PA2377 and PA4140; phosphodiesterase PA3910; phospholipases C PlcH (hemolytic), PlcN, and PlcB; protease IV; putative protease PmpA | Cytotoxicity, degradation of host tissue (e.g., in lung and eye) and surfactant proteins, disruption of cell-cell junctions (e.g., cadherin cleavage), virulence in a murine lung infection model, regulation of siderophore (pyoverdine) expression, swarming motility | 113–122 |

| For the Hxc system, phosphatase LapA; DING homolog LapC; surface-expressed PstS | Adherence to epithelial cells, survival in low-phosphate conditions | 116, 123, 124 | ||

| For the Txc system, chitin-binding protein CbpE | 125 | |||

| Pseudomonas alcaligenes | Soil/pathogen of humans (rare) | Lipase LipA | 126 | |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Soil, water, plants/pathogen of humans (pneumonia, bacteremia) | For the Xps system, proteases StmPr1 and StmPr2 and >5 secreted proteins by SDS-PAGE | Detachment and cytotoxicity toward epithelial cells, degradation of extracellular matrix and cytokines | 127, 128 |

| For the Gsp system, none identified yet | 127, 128 | |||

| Vibrio anguillarum | Marine water/pathogen of fish and eels | Metalloprotease EmpA | 129 | |

| Vibrio cholerae | Marine water, shellfish/pathogen of humans (cholera) | Aminopeptidases Lap and LapX; biofilm matrix proteins RbmA, RbmC, and Bap1; chitin-degrading enzymes including chitinase ChiA-1; chitin-binding protein GbpA; cholera toxin; collagenase VchC; cytolysin VCC; hemagglutinin-protease HapA; lipase; neuraminidase; serine proteases VesA, VesB, and VesC; TagA-related protein; and three novel proteins identified by proteomics | Watery diarrhea, degradation of mucous layers, attachment to epithelial cells, attachment to biotic (e.g., copepods) and abiotic surfaces in aquatic environments, biofilm formation, degradation of the matrix that covers the eggs of chironomids | 34, 35, 39, 41, 130–133 |

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus | Marine water, shellfish/pathogen of humans (gastroenteritis) | Lipase | 134 | |

| Vibrio vulnificus | Marine water, shellfish/pathogen of humans (septicemia) | Chitinase; cytolysin; elastase VvpE; hemolysin VvhA; putative peptidyl-proline cis-trans-isomerase; proteases including serine protease VvpS, sugar hydrolase, and several outer membrane proteins | Cytotoxicity, virulence in murine models | 135–137 |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | Intestinal tracts of mammals and various other animals/pathogen of animals and humans (gastroenteritis) | For the Yts1 system, GlcNAc-binding proteins ChiY and EngY, YE3650 | Virulence in murine model | 138, 139 |

| For the Yts2 system, none identified yet | Intracellular infection of macrophages | 138–140 | ||

| Plant pathogens (including, as indicated, some that afflict humans on rare occasions) | ||||

| Burkholderia gladioli | Soil, water/pathogen of various plants and fungi and humans (rare) | Chitinase, protease | Cavity disease in mushrooms | 141 |

| Burkholderia glumae | Soil/pathogen of rice plants | Lipase LipA, proteases, 32 other proteins identified by proteomic analysis | Virulence in rice infection | 142, 143 |

| Dickeya dadantii (formerly Erwinia chrysanthemi) | Soil, water/pathogen of various vegetables and flowers (soft rot) | For the Out system, Avr-like protein AvrL; cellulase Cel5; esterase FaeD; pectate lyases PelA, PelB, PelC, PelD, PelE, PelI, PelL, PelN, and PelZ; pectin acetylesterase PaeY; pectin methylesterase PemA; rhamnogalacturonan lyase RhiE | Soft-rot disease in plants, activation of plant innate immune system, growth promotion of EHEC on lettuce | 144–149 |

| For the Stt system, outer membrane-anchored PnlH | 150 | |||

| Erwinia amylovora | Soil/pathogen of fruit (fire blight) | Levansucrase, polygalacturonase | Infection of pear tissue, low-temperature growth | 151–153 |

| Pectobacterium carotovorum (formerly Erwinia carotovora) | Soil, water/pathogen of many plants (soft rot) | Cellulases CelV and CelB; necrosis-inducing protein (Nip); pectin lyases PelA, PelB, PelC, PelZ, Pel-3, and ECA2553; novel secreted proteins ECA2134, ECA3580, and ECA3946; polygalacturonases PehA and PehX; putative cellulase ECA2220; putative proteoglycan hydrolase ECA0852; putative virulence protein Svx | Virulence in plant model, maceration of tobacco leaf | 154–157 |

| Pectobacterium wasabiae | Soil/pathogen of plants (wasabi) | Necrosis-inducing protein (Nip) | Soft-rot disease in tubers | 158 |

| Ralstonia solanacearum | Soil/pathogen of many types of plants (wilt disease) | Cellulase, pectin methylesterase, cellobiosidase, polygalacturonases, >30 proteins identified by proteomics | Colonization of plants, causing wilting disease | 159, 160 |

| Xanthomonas axonopodis | Soil, freshwater/pathogen of citrus plants (citrus canker) | Cellulase, polygalacturonases, proteases | Virulence in orange leaves | 161, 162 |

| Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris | Soil, freshwater/pathogen of crucifer plants (black rot) | α-Amylase; cellulase; pectate lyase; polygalacturonases PghAxc and PghBxc; serine protease PrtA; other proteases | Virulence in Arabidopsis plant models | 163–165 |

| Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria | Soil, freshwater/pathogen of pepper and tomato plants (leaf spot) | For the Xps system, lipase XCV0536, protease XCV3671, and xylanases XynC, XCV4358, and XCV4360 | Virulence in pepper plant model | 166, 167 |

| For the Xcs system, none identified yet | 166 | |||

| Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae | Soil, freshwater/pathogen of various rice plants (rice blight) | Cellulase ClsA, cysteine protease CysP2, endoglucanase EglXoB, lipase LipA, polysaccharide, putative cellobiosidase CbsA, xylanase XynB | Virulence in rice infection model | 168–173 |

| Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola | Soil, freshwater/pathogen of various rice plants (rice blight) | Cysteine protease XOC1601, polygalacturonase XOC2128, protease EcpA, protease XOC3806 | Virulence in rice infection model | 174, 175 |

| Xylella fastidiosa | Plant xylem/pathogen of various plants (e.g., grapes) | Lipase/esterase LesA | Virulence in grapevine infection | 176 |

| Nonpathogens or, as indicated, bacteria that very rarely cause human disease | ||||

| Aeromonas veronii | Freshwater, leech symbiont/pathogen of humans (very rare) | Hemolysin | Colonization of the medicinal leech (symbiosis) | 177 |

| Caulobacter crescentus | Freshwater/nonpathogen | Outer membrane and secreted lipoprotein ElpS | Activates alkaline phosphatase activity | 178 |

| Cellvibrio japonicus | Soil/nonpathogen | Endoglucanase | 179 | |

| Cupriavidus metallidurans | Soil/nonpathogen | Alkaline phosphatase | 180 | |

| Nonpathogenic Escherichia coli | Intestinal tract/nonpathogen | Chitinase, lipoprotein SslE | 181, 182 | |

| Geobacter sulfurreducens | Sediments/nonpathogen | Multi-copper oxidase OmpB | 183 | |

| Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus | Symbiont of sugar cane and other plants/nonpathogen | Levansucrase | 184 | |

| Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus | Marine water/nonpathogen | Lipase | Biofilm formation | 185 |

| Methylococcus capsulatus | Fresh and marine water, sediment/nonpathogen | Serine protease MCA0875, surface-associated protein MCA2589, c-type cytochrome MCA0338 | 186 | |

| Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis | Marine water/nonpathogen | Protease | 187 | |

| Pseudoalteromonas ruthenica | Marine water/nonpathogen | CPI protease | 188 | |

| Pseudoalteromonas tunicata | Marine water/nonpathogen | >30 proteins identified by proteomics | Iron acquisition, pigmentation | 189 |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | Soil, plants, water/nonpathogen | DING homolog Psp | 190 | |

| Pseudomonas putida | Soil/nonpathogen | For the Xcp system, surface-expressed phosphatase UxpB | Growth in low-phosphate media | 191 |

| For the Xcm system, surface-expressed Mn-oxidizing enzyme(s) | 192 | |||

| Ralstonia pickettii | Soil, freshwater/primarily nonpathogen; pathogen of humans (very rare) | Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) depolymerase | 193 | |

| Shewanella oneidensis | Water/primarily nonpathogen; pathogen of humans (very rare) | Outer membrane proteins, including c-type cytochromes MtrC and OmcA, and DMSO reductase DmsA | Fe(III) and Mn(IV) reduction, extracellular respiration | 194–197 |

| Vibrio fischeri (now Allivibrio fischeri) | Marine water, symbiont of squid/nonpathogen | NAD+-glycohydrolases HvnA and HvnB | 18, 198 |

Dependence is based upon the absence or reduction of the indicated protein, activity, or phenotype in a mutant(s) specifically lacking a T2S gene(s). Abbreviations: IL-1β, interleukin 1β; STD, sexually transmitted disease; CPAF, chlamydial protease-like activity factor; EBs, elementary bodies; UTI, urinary tract infection; PMN, polymorphonuclear leukocytes; EHEC, enterohemorrhagic E. coli; CPI, cysteine protease inhibitor; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

Only the most common disease manifestation(s) is noted.

T2S in pathogens of humans and animals.

The human pathogens that are known to possess functional T2S include representatives from 10 genera of gammaproteobacteria (Acinetobacter, Aeromonas, Escherichia, Klebsiella, Legionella, Photobacterium, Pseudomonas, Stenotrophomonas, Vibrio, and Yersinia), one genus of betaproteobacteria (Burkholderia), and one genus of Chlamydiae (Chlamydia) (Fig. 1). Among the prominent human pathogens that use T2S are Acinetobacter baumannii, Aeromonas hydrophila, Burkholderia cenocepacia, Burkholderia pseudomallei, Chlamydia trachomatis, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio vulnificus, and Yersinia enterocolitica (Table 1). Some of these T2S-expressing bacteria are also natural pathogens of animals, ranging from those afflicting fish (e.g., A. hydrophila, Aeromonas salmonicida, Photobacterium damselae, and V. anguillarum) to those impacting other mammals (e.g., B. pseudomallei and Y. enterocolitica). Based upon genome sequencing and Southern blot analyses, it is likely that additional pathogenic members of these genera employ T2S (10, 26–28). In most cases, these human and animal pathogens encode a single T2S system. Yet, for some strains of E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. maltophilia, and Y. enterocolitica, there are two or three distinct T2S systems (Table 1). As more isolates are sequenced, there will likely be additional examples of multiple sets of T2S genes. At present, the functionality of the second system in E. coli, S. maltophilia, and Y. enterocolitica is unknown, as no secreted substrates or activities have been defined. A specialized growth condition(s) may be needed in order for the expression of a T2S system to be evident; e.g., whereas expression of the Xcp T2S system of P. aeruginosa is easily observed in bacteriological media, expression of the Hxc system occurs only in low phosphate. Currently, there is quite a range in the size of the T2S output of the T2S-expressing pathogens, going from one protein or activity as in K. pneumoniae, Pseudomonas alcaligenes, and V. parahaemolyticus to dozens as in Acinetobacter nosocomialis, B. pseudomallei, L. pneumophila, P. aeruginosa, and V. cholerae (Table 1). The output of many, if not all, T2S systems, however, will likely prove to be greater once proteomic analysis is applied. Most studies have identified T2S-dependent proteins in culture supernatants; however, there is increasing evidence that some substrates remain bound to the bacterial surface after secretion. The first such example was the pullulanase of K. oxytoca, and further examples have now been found in E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and V. vulnificus (Table 1). The mechanism by which the T2S apparatus facilitates the anchoring of proteins to the bacterial outer surface rely on acylation and hydrophobic or polar interactions (29). Nonetheless, by virtue of their surface localization, these proteins can be present on outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) that bleb from the bacterial cell surface (30). Other T2S substrates come to reside within OMVs, as a result of their localization in the periplasm prior to transport across the OM by the T2S apparatus (30). Because of their fusogenic capability, OMVs provide an alternative means for delivering T2S-associated substrates to host targets.

Collectively, the human pathogens that express T2S are responsible for a wide variety of diseases, ranging from pneumonia (A. baumannii, L. pneumophila, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, and S. maltophilia) to gastroenteritis and diarrhea (E. coli, V. cholerae, and Y. enterocolitica) to bloodstream (A. hydrophila, B. pseudomallei, and V. vulnificus), urinary tract (E. coli), and genital tract (C. trachomatis) infections (Table 1). Furthermore, these bacteria include both extracellular (Acinetobacter, Aeromonas, Escherichia, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, Stenotrophomonas, and Vibrio species) and intracellular (Burkholderia species, C. trachomatis, L. pneumophila, and Y. enterocolitica) pathogens. These facts imply that T2S facilitates disease in a variety of ways and is not limited to a particular pathogenic event or site of infection. Support for this inference derives from the many types of degradative enzymes and toxins that are secreted by T2S; i.e., ADP-ribosylating enzymes, carbohydrate-degrading enzymes, lipolytic enzymes, nucleases, pore-forming proteins, phosphatases, peptidases, and proteases (Table 1). Particularly well-known examples of T2S-dependent substrates are cholera toxin produced by V. cholerae, exotoxin A of P. aeruginosa, and heat-labile (LT) toxin from enterotoxigenic E. coli. The most direct proof for the role of T2S in pathogenesis is based upon the attenuated virulence of T2S mutants in animal models of disease, as has been shown for A. baumannii, A. hydrophila, B. cenocepacia, B. pseudomallei, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, L. pneumophila, P. aeruginosa, V. vulnificus, and Y. enterocolitica (Table 1). Additional assays using these mutants and/or isolated secreted proteins have revealed a diversity of mechanisms by which T2S facilitates disease. These mechanisms include the death of host cells by lysis or toxicity, degradation of tissue and extracellular matrix, cleavage of defense molecules such as cytokines and complement components and other means of suppressing innate immunity, adherence to epithelial cell surfaces, disruption of the tight junctions between host cells, biofilm formation, invasion into host cells or subsequent intracellular growth, deubiquitination, iron acquisition, and other forms of nutrient assimilation, and alterations in host ion flux triggering diarrhea (Table 1). Undoubtedly, there are even more ways in which T2S promotes pathogenesis; e.g., proteomic analysis has revealed a number of T2S substrates that are “novel,” having no sequence similarity to known proteins or enzymes (e.g., L. pneumophila, P. aeruginosa, and V. cholerae) (Table 1).

T2S in pathogens of plants.

T2S systems are also present and functional in plant pathogens that belong to the gammaproteobacteria (Dickeya, Erwinia, Pectobacterium, Xanthomonas, and Xylella) and betaproteobacteria (Burkholderia and Ralstonia) (Fig. 1). The T2S-expressing phytopathogens include Burkholderia gladioli, Burkholderia glumae, Dickeya dadantii, Erwinia amylovora, Pectobacterium carotovorum, Pectobacterium wasabiae, Ralstonia solanacearum, Xanthomonas axonopodis, Xanthomonas campestris, Xanthomonas oryzae, and Xylella fastidiosa (Table 1). Collectively, they cause serious diseases of flowers, fruit (e.g., pear, citrus, and grape), rice, tubers, and vegetables (e.g., crucifers and peppers) (Table 1). Many of the concepts noted above when discussing the T2S-expressing human pathogens also apply here. For example, some of the plant pathogens have multiple T2S systems (D. dadantii, X. campestris pv. vesicatoria), secrete ≥15 T2S substrates (B. glumae, D. dadantii, P. carotovorum, and R. solanacearum), and express T2S substrates on their surface (D. dadantii). They also secrete some enzymes that are similar to those made by the human and animal pathogens (e.g., lipases and proteases) as well as “novel” proteins that may encode a new enzymatic activity and/or mediate a new type of process. Not surprisingly, the T2S systems of the phytopathogens elaborate a large number and variety of carbohydrate-degrading enzymes that specifically degrade plant tissue, e.g., cellulases, pectate lyases, xylanases, and polygalacturonases (Table 1). In every case examined, mutations in the genes encoding T2S diminish virulence in a relevant host(s) (Table 1), clearly showing the importance of T2S in plant pathogenesis.

T2S in nonpathogenic, environmental bacteria.

Although T2S in pathogens has received the greatest attention, there have been a number of studies documenting T2S functionality in nonpathogenic bacteria or bacteria that only very rarely cause disease (Table 1). These bacteria are quite diverse, ranging from alphaproteobacteria (Caulobacter and Gluconacetobacter) to betaproteobacteria (Cupriavidus and Ralstonia) to gammaproteobacteria (Aeromonas, Cellvibrio, Escherichia, Marinobacter, Methylococcus, Pseudoalteromonas, Pseudomonas, Shewanella, and Vibrio) to deltaproteobacteria (Geobacter) (Fig. 1). In most cases, they are primarily free-living organisms, inhabiting soil, freshwater, and/or salt water. However, some exist in symbiotic relationships with plants (Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus and Pseudomonas fluorescens) or animals (Aeromonas veronii, E. coli, and Vibrio fischeri), and in the case of A. veronii, T2S actually promotes the symbiosis with leeches (Table 1). Based on the genome database, it is likely that many more nonpathogens utilize T2S, including species of Azoarcus, Bdellovibrio, Bradyrhizobium, Chromobacterium, Mesorhizobium, Methylotenera, and Myxococcus as well as marine gammaproteobacteria belonging to Idiomarina, Marinomonas, Psychromonas, and Saccharophagus (10, 18, 31–33) (Fig. 1). The study of nonpathogens has revealed a variety of secreted proteins and processes that had not been seen with the pathogenic organisms. Among the novel T2S-dependent substrates are the multicopper oxidase of Geobacter sulfurreducens, levansucrase of G. diazotrophicus, c-type cytochrome of Methylococcus capsulatus, Mn-oxidizing enzymes of Pseudomonas putida, and NAD-glycohydrolases of V. fischeri, and included in the T2S-facilitated processes are pigmentation by Pseudomonas tunicata and Fe3+ reduction and extracellular respiration by Shewanella oneidensis (Table 1). Thus, by considering the full range of T2S-expressing bacteria, the functional diversity of T2S can be even better appreciated.

T2S in the transition of environmental bacteria to pathogens, as illustrated by V. cholerae and L. pneumophila.

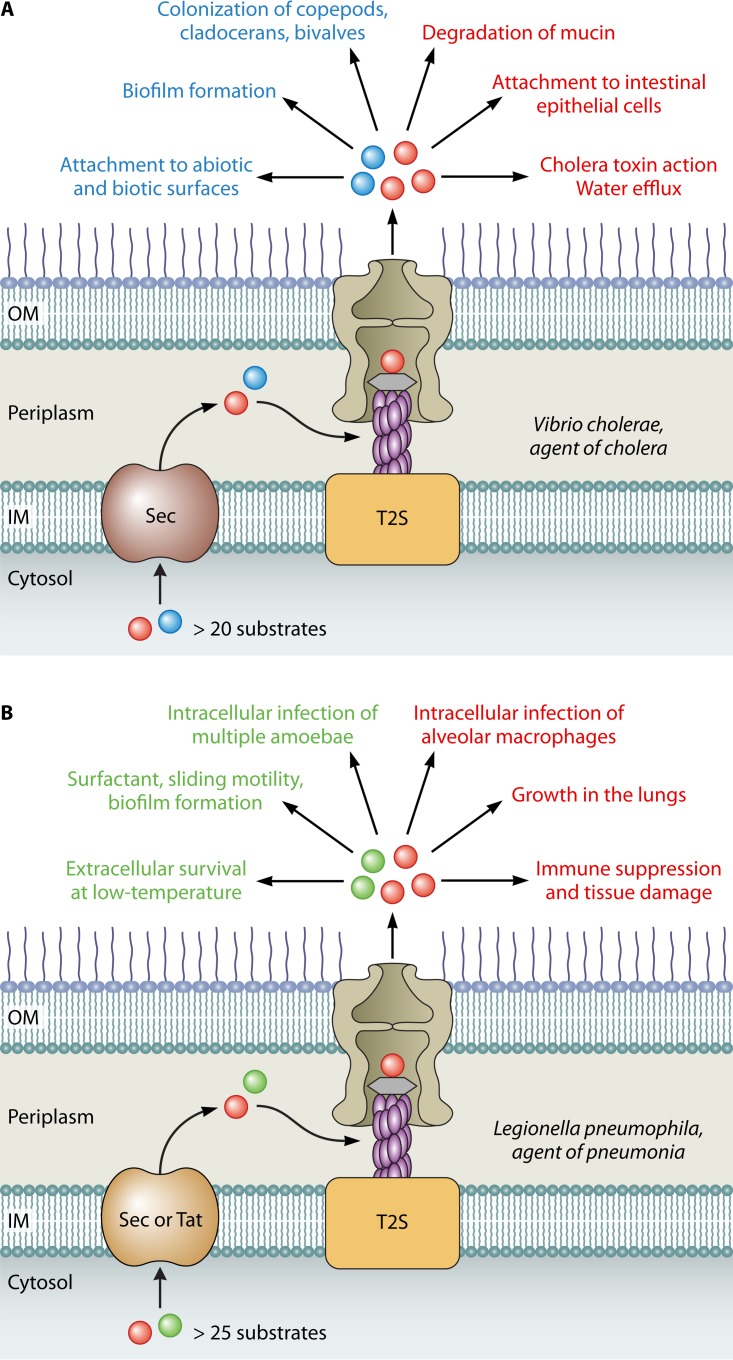

Nearly all of the T2S-expressing pathogens exist in the environment in addition to their higher organism hosts. Arguably, the impact of T2S is best appreciated by contemplating how T2S assists bacteria in both their environmental niche(s) and their human, animal, or plant host(s). This point is most clear from studies done with V. cholerae, the agent of cholera and a classic extracellular pathogen, and L. pneumophila, the etiologic agent of Legionnaires' disease and a well-known intracellular pathogen. In the case of V. cholerae, the Eps T2S system enhances attachment to and biofilm formation on abiotic and biotic surfaces in marine environments (34). This, in turn, promotes the growth of planktonic V. cholerae as well as bacterial colonization of marine creatures such as bivalves, copepods, and cladocerans (35). Among the T2S-dependent proteins that mediate environmental persistence are the chitin-binding protein GbpA that aids in attachment, ChiA and other chitinases that generate carbon and energy sources for growth, the biofilm-promoting RbmC, and the HapA protease which can degrade the matrix that covers the eggs of chironomids (34–37). By helping to increase the numbers of V. cholerae in the environment, T2S promotes the transmission of the Vibrio pathogen to human hosts via the ingestion of contaminated waters. Once in the human host, T2S continues to play a major role by secreting HapA which degrades mucin and thereby permits bacterial access to the underlying intestinal epithelium, GbpA which enhances binding to mucins that overlay the epithelium, cholera toxin which triggers water efflux from enterocytes (i.e., massive watery diarrhea), and HapA, VesA, and VesB which can proteolytically activate cholera toxin and other toxins (34, 35, 38–41). In summary, T2S is unquestionably important for V. cholerae both in its natural marine environment and in the human host, facilitating, in multiple ways, extracellular replication and dissemination (Fig. 2A).

FIG 2.

Roles of T2S in V. cholerae and L. pneumophila. (A) More than 20 proteins are secreted via the T2S system of V. cholerae. T2S promotes the environmental survival of extracellular V. cholerae in a variety of ways, including the colonization of biotic surfaces (left side, in blue). This facilitates transmission to the human host, where T2S mediates another set of activities that leads to cholera (right side, in red). (B) More than 25 substrates are handled by the T2S system of L. pneumophila. In the environment, T2S facilitates the spread of L. pneumophila by contributing to planktonic survival, biofilm formation, and intracellular infection of amoebae (left side, in green). Following the inhalation of L. pneumophila, T2S promotes bacterial growth within lung macrophages, which leads to tissue damage and pneumonia (right side, in red).

Turning to L. pneumophila, it is necessary to first emphasize that the persistence of the Legionella pathogen in freshwater environments is primarily due to its capacity to infect a wide array of amoebae (42). The Lsp T2S system of L. pneumophila has a major role in infection of amoebae, promoting intracellular growth in at least four genera, i.e., Acanthamoeba, Naegleria, Vermamoeba (formerly Hartmannella), and Willaertia (43–47). This function of T2S is manifest over a temperature range of 22 to 37°C, further indicating the impact of T2S across different aquatic niches (48). The T2S-dependent substrates that are known to potentiate amoebal infection are the acyltransferase PlaC, metalloprotease ProA, RNase SrnA, and novel proteins NttA and NttC (46, 47, 49, 50). Interestingly, the importance of each of these secreted proteins varies depending upon the amoeba being infected, suggesting that the T2S repertoire of L. pneumophila has evolved, in part, to enhance the bacterium's broad host range (47). Besides its predilection for amoebae, L. pneumophila survives extracellularly in its aquatic habitats, either planktonically or in multiorganismal biofilms (51, 52). T2S is also relevant for these lifestyles, as documented in several ways. First, T2S mutants display impaired extracellular survival in tap water samples when incubated at 4 to 25°C (48). The fact that the secretome of L. pneumophila changes with temperature suggests that one or more secreted proteins, including a predicted peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase (PPIase), facilitate low-temperature survival (53). Second, a mutant specifically lacking the T2S-dependent Lcl protein exhibits a reduced ability to form biofilms (54). Finally, T2S mutants demonstrate impaired sliding motility, which is linked to the secretion of a novel surfactant (55–57). By fostering L. pneumophila growth within water systems, T2S contributes to the genesis of human infection which occurs via the inhalation of contaminated water droplets generated by various aerosol-generating devices. Yet, T2S also enhances L. pneumophila growth within the lung itself; i.e., secretion mutants are impaired in both murine and guinea pig models of pneumonia (26, 43, 58). The intrapulmonary role of T2S primarily involves L. pneumophila intracellular infection of macrophages (26, 59). Recent studies indicate that T2S is not required for L. pneumophila entry into the macrophage host or its subsequent evasion of phagosome-lysosome fusion (60). Rather, T2S facilitates the onset of bacterial replication at 4 to 8 h postentry as well as the capacity to grow to large numbers within the Legionella-containing vacuole at 12 h and beyond. This growth promotion involves both the retention of the host GTPase Rab1B on the Legionella-containing vacuole as well as a Rab1B-independent event(s) that is yet to be defined (60). Besides facilitating bacterial growth in macrophages, T2S is necessary for optimal replication within epithelial cells, which likely are a secondary host cell during lung infection (59). Furthermore, the T2S system dampens the cytokine output of infected macrophages and epithelial cells (59). This suppression of the innate immune response, which is manifest at the transcriptional level due to dampening of the MyD88 and Toll-like receptor 2 signaling pathway, is believed to initially limit inflammatory cell infiltrates into the lung and thus permit prolonged bacterial growth (61). As for the T2S-dependent proteins that are known to potentiate disease, the chitinase ChiA promotes bacterial growth and persistence in the lungs but in a manner that appears to be independent of intracellular growth (58). One hypothesis for this novel finding is that ChiA acts upon chitin-like molecules (e.g., O-GlcNAcylated proteins) in the lung. Finally, the metalloprotease ProA functions as a virulence factor by degrading lung tissue and cytokines (59, 62–64). Thus, L. pneumophila provides a striking example of the many ways in which T2S can promote both bacterial growth in the environment and virulence in the human host (Fig. 2B). L. pneumophila's adaptation to an intracellular niche in aquatic amoebae engendered it with the capacity to grow in human macrophages, and it is now clear that T2S plays a major role in both forms of intracellular infection.

Final thoughts and ongoing questions.

In recent years, we have experienced an impressive increase in knowledge about bacterial T2S. These advancements include not only the fine-structure analysis of the T2S apparatus but also, as detailed here, a refined understanding of the distribution of T2S among Gram-negative organisms and the large and diverse roles of this secretion system (Table 1). Given the breadth of its involvement in pathogenic processes, it is clear that the importance of T2S rivals that of the other known secretion systems operating in Gram-negative bacteria that afflict humans, animals, or plants. Although we have learned a great deal about the output and functional consequences of T2S in pathogens and nonpathogens, there is still much insight to be gained, given that many of the secreted factors produced by these bacteria are still only minimally defined or entirely uncharacterized (Table 1). Indeed, some of these T2S-dependent substrates may represent new types of enzymes which might mediate novel pathogenic activities. Based on the data assembled in Table 1, there are also a number of T2S systems that are only slightly characterized and/or not yet examined in pertinent disease models. Moreover, the genome database indicates that there are many other bacteria, including pathogens, that harbor T2S systems that have not been investigated at all. All of these studies should take into consideration how the output and function of a T2S system might change depending upon growth conditions and regulatory networks. As the T2S catalog expands, various comparisons between the secreted proteins might reveal new structural similarities or motifs that help address a long-standing question in the field, that is, how T2S substrates are recognized by the secretion apparatus. In light of the now-demonstrated importance of T2S in a wide range of pathogenic bacteria, future work should also consider using the structural and functional knowledge gained to develop potential new strategies or reagents for preventing or combatting human, animal, or plant infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank past and present members of the Cianciotto lab for their studies on type II secretion and much helpful advice.

This work was funded by NIH grant AI043987 awarded to N.P.C.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chang JH, Desveaux D, Creason AL. 2014. The ABCs and 123s of bacterial secretion systems in plant pathogenesis. Annu Rev Phytopathol 52:317–345. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-011014-015624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costa TR, Felisberto-Rodrigues C, Meir A, Prevost MS, Redzej A, Trokter M, Waksman G. 2015. Secretion systems in Gram-negative bacteria: structural and mechanistic insights. Nat Rev Microbiol 13:343–359. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McBride MJ, Nakane D. 2015. Flavobacterium gliding motility and the type IX secretion system. Curr Opin Microbiol 28:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.d'Enfert C, Ryter A, Pugsley AP. 1987. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of the Klebsiella pneumoniae genes for production, surface localization and secretion of the lipoprotein pullulanase. EMBO J 6:3531–3538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russel M. 1998. Macromolecular assembly and secretion across the bacterial cell envelope: type II protein secretion systems. J Mol Biol 279:485–499. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandkvist M. 2001. Type II secretion and pathogenesis. Infect Immun 69:3523–3535. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.6.3523-3535.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsirigotaki A, De Geyter J, Sostaric N, Economou A, Karamanou S. 2017. Protein export through the bacterial Sec pathway. Nat Rev Microbiol 15:21–36. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berks BC. 2015. The twin-arginine protein translocation pathway. Annu Rev Biochem 84:843–864. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peabody CR, Chung YJ, Yen MR, Vidal-Ingigliardi D, Pugsley AP, Saier MH Jr. 2003. Type II protein secretion and its relationship to bacterial type IV pili and archaeal flagella. Microbiology 149:3051–3072. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26364-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cianciotto NP. 2005. Type II secretion: a protein secretion system for all seasons. Trends Microbiol 13:581–588. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korotkov KV, Sandkvist M, Hol WG. 2012. The type II secretion system: biogenesis, molecular architecture and mechanism. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:336–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLaughlin LS, Haft RJ, Forest KT. 2012. Structural insights into the Type II secretion nanomachine. Curr Opin Struct Biol 22:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Douzi B, Filloux A, Voulhoux R. 2012. On the path to uncover the bacterial type II secretion system. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 367:1059–1072. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howard SP. 2013. Assembly of the type II secretion system. Res Microbiol 164:535–544. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nivaskumar M, Francetic O. 2014. Type II secretion system: a magic beanstalk or a protein escalator. Biochim Biophys Acta 1843:1568–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan Z, Yin M, Xu D, Zhu Y, Li X. 2017. Structural insights into the secretin translocation channel in the type II secretion system. Nat Struct Mol Biol 24:177–183. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pineau C, Guschinskaya N, Robert X, Gouet P, Ballut L, Shevchik VE. 2014. Substrate recognition by the bacterial type II secretion system: more than a simple interaction. Mol Microbiol 94:126–140. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans FF, Egan S, Kjelleberg S. 2008. Ecology of type II secretion in marine gammaproteobacteria. Environ Microbiol 10:1101–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abby SS, Cury J, Guglielmini J, Neron B, Touchon M, Rocha EP. 2016. Identification of protein secretion systems in bacterial genomes. Sci Rep 6:23080. doi: 10.1038/srep23080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen BD, Valdivia RH. 2012. Virulence determinants in the obligate intracellular pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis revealed by forward genetic approaches. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:1263–1268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117884109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeng L, Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Yin H, Zhuang X, Zhu W, Guo X, Qin J. 2013. Extracellular proteome analysis of Leptospira interrogans serovar Lai. OMICS 17:527–535. doi: 10.1089/omi.2013.0043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eshghi A, Pappalardo E, Hester S, Thomas B, Pretre G, Picardeau M. 2015. Pathogenic Leptospira interrogans exoproteins are primarily involved in heterotrophic processes. Infect Immun 83:3061–3073. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00427-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schatz D, Nagar E, Sendersky E, Parnasa R, Zilberman S, Carmeli S, Mastai Y, Shimoni E, Klein E, Yeger O, Reich Z, Schwarz R. 2013. Self-suppression of biofilm formation in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus. Environ Microbiol 15:1786–1794. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Desvaux M, Hebraud M, Talon R, Henderson IR. 2009. Secretion and subcellular localizations of bacterial proteins: a semantic awareness issue. Trends Microbiol 17:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalbey RE, Kuhn A. 2012. Protein traffic in Gram-negative bacteria–how exported and secreted proteins find their way. FEMS Microbiol Rev 36:1023–1045. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossier O, Starkenburg S, Cianciotto NP. 2004. Legionella pneumophila type II protein secretion promotes virulence in the A/J mouse model of Legionnaires' disease pneumonia. Infect Immun 72:310–321. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.310-321.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Tils D, Bladel I, Schmidt MA, Heusipp G. 2012. Type II secretion in Yersinia - a secretion system for pathogenicity and environmental fitness. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2:160. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burtnick MN, Brett PJ, DeShazer D. 2014. Proteomic analysis of the Burkholderia pseudomallei type II secretome reveals hydrolytic enzymes, novel proteins and the deubiquitinase TssM. Infect Immun 82:3214–3226. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01739-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rondelet A, Condemine G. 2013. Type II secretion: the substrates that won't go away. Res Microbiol 164:556–561. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ellis TN, Kuehn MJ. 2010. Virulence and immunomodulatory roles of bacterial outer membrane vesicles. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 74:81–94. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00031-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hempel J, Zehner S, Gottfert M, Patschkowski T. 2009. Analysis of the secretome of the soybean symbiont Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Biotechnol 140:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Konovalova A, Petters T, Sogaard-Andersen L. 2010. Extracellular biology of Myxococcus xanthus. FEMS Microbiol Rev 34:89–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beck DA, Hendrickson EL, Vorobev A, Wang T, Lim S, Kalyuzhnaya MG, Lidstrom ME, Hackett M, Chistoserdova L. 2011. An integrated proteomics/transcriptomics approach points to oxygen as the main electron sink for methanol metabolism in Methylotenera mobilis. J Bacteriol 193:4758–4765. doi: 10.1128/JB.05375-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sikora AE. 2013. Proteins secreted via the type II secretion system: smart strategies of Vibrio cholerae to maintain fitness in different ecological niches. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003126. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stauder M, Huq A, Pezzati E, Grim CJ, Ramoino P, Pane L, Colwell RR, Pruzzo C, Vezzulli L. 2012. Role of GbpA protein, an important virulence-related colonization factor, for Vibrio cholerae's survival in the aquatic environment. Environ Microbiol Rep 4:439–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2012.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halpern M, Gancz H, Broza M, Kashi Y. 2003. Vibrio cholerae hemagglutinin/protease degrades chironomid egg masses. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:4200–4204. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.7.4200-4204.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fong JC, Yildiz FH. 2007. The rbmBCDEF gene cluster modulates development of rugose colony morphology and biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 189:2319–2330. doi: 10.1128/JB.01569-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silva AJ, Pham K, Benitez JA. 2003. Haemagglutinin/protease expression and mucin gel penetration in El Tor biotype Vibrio cholerae. Microbiology 149:1883–1891. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kirn TJ, Jude BA, Taylor RK. 2005. A colonization factor links Vibrio cholerae environmental survival and human infection. Nature 438:863–866. doi: 10.1038/nature04249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhowmick R, Ghosal A, Das B, Koley H, Saha DR, Ganguly S, Nandy RK, Bhadra RK, Chatterjee NS. 2008. Intestinal adherence of Vibrio cholerae involves a coordinated interaction between colonization factor GbpA and mucin. Infect Immun 76:4968–4977. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01615-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sikora AE, Zielke RA, Lawrence DA, Andrews PC, Sandkvist M. 2011. Proteomic analysis of the Vibrio cholerae type II secretome reveals new proteins, including three related serine proteases. J Biol Chem 286:16555–16566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.211078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cianciotto NP, Hilbi H, Buchrieser C. 2013. Legionnaires' disease, p 147–217. In Rosenberg E, DeLong EF, Stackebrandt E, Thompson F, Lory S (ed), The prokaryotes – human microbiology, 4th ed, vol 1 Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liles MR, Edelstein PH, Cianciotto NP. 1999. The prepilin peptidase is required for protein secretion by and the virulence of the intracellular pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Mol Microbiol 31:959–970. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hales LM, Shuman HA. 1999. Legionella pneumophila contains a type II general secretion pathway required for growth in amoebae as well as for secretion of the Msp protease. Infect Immun 67:3662–3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rossier O, Cianciotto NP. 2001. Type II protein secretion is a subset of the PilD-dependent processes that facilitate intracellular infection by Legionella pneumophila. Infect Immun 69:2092–2098. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2092-2098.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tyson JY, Pearce MM, Vargas P, Bagchi S, Mulhern BJ, Cianciotto NP. 2013. Multiple Legionella pneumophila type II secretion substrates, including a novel protein, contribute to differential infection of amoebae Acanthamoeba castellanii, Hartmannella vermiformis, and Naegleria lovaniensis. Infect Immun 81:1399–1410. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00045-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tyson JY, Vargas P, Cianciotto NP. 2014. The novel Legionella pneumophila type II secretion substrate NttC contributes to infection of amoebae Hartmannella vermiformis and Willaertia magna. Microbiology 160:2732–2744. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.082750-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Söderberg MA, Dao J, Starkenburg S, Cianciotto NP. 2008. Importance of type II secretion for Legionella pneumophila survival in tap water and amoebae at low temperature. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:5583–5588. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00067-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rossier O, Dao J, Cianciotto NP. 2008. The type II secretion system of Legionella pneumophila elaborates two aminopeptidases as well as a metalloprotease that contributes to differential infection among protozoan hosts. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:753–761. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01944-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rossier O, Dao J, Cianciotto NP. 2009. A type II-secreted ribonuclease of Legionella pneumophila facilitates optimal intracellular infection of Hartmannella vermiformis. Microbiology 155:882–890. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.023218-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stewart CR, Muthye V, Cianciotto NP. 2012. Legionella pneumophila persists within biofilms formed by Klebsiella pneumoniae, Flavobacterium sp., and Pseudomonas fluorescens under dynamic flow conditions. PLoS One 7:e50560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abdel-Nour M, Duncan C, Low DE, Guyard C. 2013. Biofilms: the stronghold of Legionella pneumophila. Int J Mol Sci 14:21660–21675. doi: 10.3390/ijms141121660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Söderberg MA, Cianciotto NP. 2008. A Legionella pneumophila peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase present in culture supernatants is necessary for optimal growth at low temperatures. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:1634–1638. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02512-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Duncan C, Prashar A, So J, Tang P, Low DE, Terebiznik M, Guyard C. 2011. Lcl of Legionella pneumophila is an immunogenic GAG binding adhesin that promotes interactions with lung epithelial cells and plays a crucial role in biofilm formation. Infect Immun 79:2168–2181. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01304-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stewart CR, Rossier O, Cianciotto NP. 2009. Surface translocation by Legionella pneumophila: a form of sliding motility that is dependent upon type II protein secretion. J Bacteriol 191:1537–1546. doi: 10.1128/JB.01531-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stewart CR, Burnside DM, Cianciotto NP. 2011. The surfactant of Legionella pneumophila is secreted in a TolC-dependent manner and is antagonistic toward other Legionella species. J Bacteriol 193:5971–5984. doi: 10.1128/JB.05405-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johnston CW, Plumb J, Li X, Grinstein S, Magarvey NA. 2016. Informatic analysis reveals Legionella as a source of novel natural products. Synth Syst Biotechnol 1:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.synbio.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.DebRoy S, Dao J, Soderberg M, Rossier O, Cianciotto NP. 2006. Legionella pneumophila type II secretome reveals unique exoproteins and a chitinase that promotes bacterial persistence in the lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:19146–19151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608279103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McCoy-Simandle K, Stewart CR, Dao J, Debroy S, Rossier O, Bryce PJ, Cianciotto NP. 2011. Legionella pneumophila type II secretion dampens the cytokine response of infected macrophages and epithelia. Infect Immun 79:1984–1997. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01077-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.White RC, Cianciotto NP. 2016. Type II secretion is necessary for optimal association of the Legionella-containing vacuole with macrophage Rab1B but enhances intracellular replication mainly by Rab1B-independent mechanisms. Infect Immun 84:3313–3327. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00750-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mallama CA, McCoy-Simandle K, Cianciotto NP. 30 January 2017. The type II secretion system of Legionella pneumophila dampens the MyD88 and TLR2 signaling pathway in infected human macrophages. Infect Immun. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hell W, Essig A, Bohnet S, Gatermann S, Marre R. 1993. Cleavage of tumor necrosis factor-alpha by Legionella exoprotease. APMIS 101:120–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1993.tb00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mintz CS, Miller RD, Gutgsell NS, Malek T. 1993. Legionella pneumophila protease inactivates interleukin-2 and cleaves CD4 on human T cells. Infect Immun 61:3416–3421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moffat JF, Edelstein PH, Regula DP Jr, Cirillo JD, Tompkins LS. 1994. Effects of an isogenic Zn-metalloprotease-deficient mutant of Legionella pneumophila in a guinea-pig pneumonia model. Mol Microbiol 12:693–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cole JR, Wang Q, Fish JA, Chai B, McGarrell DM, Sun Y, Brown CT, Porras-Alfaro A, Kuske CR, Tiedje JM. 2014. Ribosomal Database Project: data and tools for high throughput rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 42:D633–D642. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Soding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. 2011. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol 7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, Thierer T, Ashton B, Meintjes P, Drummond A. 2012. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saitou N, Nei M. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4:406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Johnson TL, Waack U, Smith S, Mobley H, Sandkvist M. 2015. Acinetobacter baumannii is dependent on the type II secretion system and its substrate LipA for lipid utilization and in vivo fitness. J Bacteriol 198:711–719. doi: 10.1128/JB.00622-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Elhosseiny NM, El-Tayeb OM, Yassin AS, Lory S, Attia AS. 2016. The secretome of Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 17978 type II secretion system reveals a novel plasmid encoded phospholipase that could be implicated in lung colonization. Int J Med Microbiol 306:633–641. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Parche S, Geissdorfer W, Hillen W. 1997. Identification and characterization of xcpR encoding a subunit of the general secretory pathway necessary for dodecane degradation in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus ADP1. J Bacteriol 179:4631–4634. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.14.4631-4634.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Harding CM, Kinsella RL, Palmer LD, Skaar EP, Feldman MF. 2016. Medically relevant Acinetobacter species require a type II secretion system and specific membrane-associated chaperones for the export of multiple substrates and full virulence. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005391. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Howard SP, Critch J, Bedi A. 1993. Isolation and analysis of eight exe genes and their involvement in extracellular protein secretion and outer membrane assembly in Aeromonas hydrophila. J Bacteriol 175:6695–6703. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.20.6695-6703.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thomas SR, Trust TJ. 1995. A specific PulD homolog is required for the secretion of paracrystalline surface array subunits in Aeromonas hydrophila. J Bacteriol 177:3932–3939. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.3932-3939.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brumlik MJ, van der Goot FG, Wong KR, Buckley JT. 1997. The disulfide bond in the Aeromonas hydrophila lipase/acyltransferase stabilizes the structure but is not required for secretion or activity. J Bacteriol 179:3116–3121. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3116-3121.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xu XJ, Ferguson MR, Popov VL, Houston CW, Peterson JW, Chopra AK. 1998. Role of a cytotoxic enterotoxin in Aeromonas-mediated infections: development of transposon and isogenic mutants. Infect Immun 66:3501–3509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Buckley JT, Howard SP. 1999. The cytotoxic enterotoxin of Aeromonas hydrophila is aerolysin. Infect Immun 67:466–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Galindo CL, Fadl AA, Sha J, Gutierrez C Jr, Popov VL, Boldogh I, Aggarwal BB, Chopra AK. 2004. Aeromonas hydrophila cytotoxic enterotoxin activates mitogen-activated protein kinases and induces apoptosis in murine macrophages and human intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 279:37597–37612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Burr SE, Diep DB, Buckley JT. 2001. Type II secretion by Aeromonas salmonicida: evidence for two periplasmic pools of proaerolysin. J Bacteriol 183:5956–5963. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.20.5956-5963.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kothe M, Antl M, Huber B, Stoecker K, Ebrecht D, Steinmetz I, Eberl L. 2003. Killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by Burkholderia cepacia is controlled by the cep quorum-sensing system. Cell Microbiol 5:343–351. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kooi C, Sokol PA. 2009. Burkholderia cenocepacia zinc metalloproteases influence resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Microbiology 155:2818–2825. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.028969-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Somvanshi VS, Viswanathan P, Jacobs JL, Mulks MH, Sundin GW, Ciche TA. 2010. The type 2 secretion pseudopilin, gspJ, is required for multihost pathogenicity of Burkholderia cenocepacia AU1054. Infect Immun 78:4110–4121. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00558-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rosales-Reyes R, Aubert DF, Tolman JS, Amer AO, Valvano MA. 2012. Burkholderia cenocepacia type VI secretion system mediates escape of type II secreted proteins into the cytoplasm of infected macrophages. PLoS One 7:e41726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.DeShazer D, Brett PJ, Burtnick MN, Woods DE. 1999. Molecular characterization of genetic loci required for secretion of exoproducts in Burkholderia pseudomallei. J Bacteriol 181:4661–4664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tan KS, Chen Y, Lim YC, Tan GY, Liu Y, Lim YT, Macary P, Gan YH. 2010. Suppression of host innate immune response by Burkholderia pseudomallei through the virulence factor TssM. J Immunol 184:5160–5171. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fehlner-Gardiner CC, Hopkins TM, Valvano MA. 2002. Identification of a general secretory pathway in a human isolate of Burkholderia vietnamiensis (formerly B. cepacia complex genomovar V) that is required for the secretion of hemolysin and phospholipase C activities. Microb Pathog 32:249–254. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2002.0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Snavely EA, Kokes M, Dunn JD, Saka HA, Nguyen BD, Bastidas RJ, McCafferty DG, Valdivia RH. 2014. Reassessing the role of the secreted protease CPAF in Chlamydia trachomatis infection through genetic approaches. Pathog Dis 71:336–351. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tang L, Chen J, Zhou Z, Yu P, Yang Z, Zhong G. 2015. Chlamydia-secreted protease CPAF degrades host antimicrobial peptides. Microbes Infect 17:402–408. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang Z, Tang L, Sun X, Chai J, Zhong G. 2015. Characterization of CPAF critical residues and secretion during Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Infect Immun 83:2234–2241. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00275-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Luo Q, Kumar P, Vickers TJ, Sheikh A, Lewis WG, Rasko DA, Sistrunk J, Fleckenstein JM. 2014. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli secretes a highly conserved mucin-degrading metalloprotease to effectively engage intestinal epithelial cells. Infect Immun 82:509–521. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01106-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lathem WW, Grys TE, Witowski SE, Torres AG, Kaper JB, Tarr PI, Welch RA. 2002. StcE, a metalloprotease secreted by Escherichia coli O157:H7, specifically cleaves C1 esterase inhibitor. Mol Microbiol 45:277–288. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Grys TE, Siegel MB, Lathem WW, Welch RA. 2005. The StcE protease contributes to intimate adherence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 to host cells. Infect Immun 73:1295–1303. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1295-1303.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ho TD, Davis BM, Ritchie JM, Waldor MK. 2008. Type 2 secretion promotes enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli adherence and intestinal colonization. Infect Immun 76:1858–1865. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01688-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Baldi DL, Higginson EE, Hocking DM, Praszkier J, Cavaliere R, James CE, Bennett-Wood V, Azzopardi KI, Turnbull L, Lithgow T, Robins-Browne RM, Whitchurch CB, Tauschek M. 2012. The type II secretion system and its ubiquitous lipoprotein substrate, SslE, are required for biofilm formation and virulence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun 80:2042–2052. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06160-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hernandes RT, De la Cruz MA, Yamamoto D, Giron JA, Gomes TA. 2013. Dissection of the role of pili and type 2 and 3 secretion systems in adherence and biofilm formation of an atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strain. Infect Immun 81:3793–3802. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00620-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dorsey FC, Fischer JF, Fleckenstein JM. 2006. Directed delivery of heat-labile enterotoxin by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Cell Microbiol 8:1516–1527. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yang J, Baldi DL, Tauschek M, Strugnell RA, Robins-Browne RM. 2007. Transcriptional regulation of the yghJ-pppA-yghG-gspCDEFGHIJKLM cluster, encoding the type II secretion pathway in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 189:142–150. doi: 10.1128/JB.01115-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kumar A, Hays M, Lim F, Foster LJ, Zhou M, Zhu G, Miesner T, Hardwidge PR. 2015. Protective enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli antigens in a murine intranasal challenge model. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9:e0003924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Strozen TG, Li G, Howard SP. 2012. YghG (GspSbeta) is a novel pilot protein required for localization of the GspSbeta type II secretion system secretin of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun 80:2608–2622. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06394-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Moriel DG, Bertoldi I, Spagnuolo A, Marchi S, Rosini R, Nesta B, Pastorello I, Corea VA, Torricelli G, Cartocci E, Savino S, Scarselli M, Dobrindt U, Hacker J, Tettelin H, Tallon LJ, Sullivan S, Wieler LH, Ewers C, Pickard D, Dougan G, Fontana MR, Rappuoli R, Pizza M, Serino L. 2010. Identification of protective and broadly conserved vaccine antigens from the genome of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:9072–9077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915077107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zalewska-Piatek B, Bury K, Piatek R, Bruzdziak P, Kur J. 2008. Type II secretory pathway for surface secretion of DraD invasin from the uropathogenic Escherichia coli Dr+ strain. J Bacteriol 190:5044–5056. doi: 10.1128/JB.00224-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kulkarni R, Dhakal BK, Slechta ES, Kurtz Z, Mulvey MA, Thanassi DG. 2009. Roles of putative type II secretion and type IV pilus systems in the virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. PLoS One 4:e4752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pugsley AP. 1993. The complete general secretory pathway in Gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Rev 57:50–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tomas A, Lery L, Regueiro V, Perez-Gutierrez C, Martinez V, Moranta D, Llobet E, Gonzalez-Nicolau M, Insua JL, Tomas JM, Sansonetti PJ, Tournebize R, Bengoechea JA. 2015. Functional genomic screen identifies Klebsiella pneumoniae factors implicated in blocking nuclear factor kappaB (NF-kappaB) signaling. J Biol Chem 290:16678–16697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.621292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rossier O, Cianciotto NP. 2005. The Legionella pneumophila tatB gene facilitates secretion of phospholipase C, growth under iron-limiting conditions, and intracellular infection. Infect Immun 73:2020–2032. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2020-2032.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Söderberg MA, Rossier O, Cianciotto NP. 2004. The type II protein secretion system of Legionella pneumophila promotes growth at low temperatures. J Bacteriol 186:3712–3720. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.12.3712-3720.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.DebRoy S, Aragon V, Kurtz S, Cianciotto NP. 2006. Legionella pneumophila Mip, a surface-exposed peptidylproline cis-trans-isomerase, promotes the presence of phospholipase C-like activity in culture supernatants. Infect Immun 74:5152–5160. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00484-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pearce MM, Cianciotto NP. 2009. Legionella pneumophila secretes an endoglucanase that belongs to the family-5 of glycosyl hydrolases and is dependent upon type II secretion. FEMS Microbiol Lett 300:256–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01801.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cianciotto NP. 2009. Many substrates and functions of type II protein secretion: lessons learned from Legionella pneumophila. Future Microbiol 4:797–805. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Herrmann V, Eidner A, Rydzewski K, Bladel I, Jules M, Buchrieser C, Eisenreich W, Heuner K. 2011. GamA is a eukaryotic-like glucoamylase responsible for glycogen- and starch-degrading activity of Legionella pneumophila. Int J Med Microbiol 301:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Abdel-Nour M, Duncan C, Prashar A, Rao C, Ginevra C, Jarraud S, Low DE, Ensminger AW, Terebiznik MR, Guyard C. 2014. The Legionella pneumophila collagen-like protein mediates sedimentation, autoaggregation, and pathogen-phagocyte interactions. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:1441–1454. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03254-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rivas AJ, Vences A, Husmann M, Lemos ML, Osorioa CR. 2015. Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae major virulence factors Dly, plasmid-encoded HlyA, and chromosome-encoded HlyA are secreted via the type II secretion system. Infect Immun 83:1246–1256. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02608-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Vance RE, Hong S, Gronert K, Serhan CN, Mekalanos JJ. 2004. The opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa carries a secretable arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:2135–2139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307308101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Overhage J, Lewenza S, Marr AK, Hancock RE. 2007. Identification of genes involved in swarming motility using a Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 mini-Tn5-lux mutant library. J Bacteriol 189:2164–2169. doi: 10.1128/JB.01623-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Seo J, Brencic A, Darwin AJ. 2009. Analysis of secretin-induced stress in Pseudomonas aeruginosa suggests prevention rather than response and identifies a novel protein involved in secretin function. J Bacteriol 191:898–908. doi: 10.1128/JB.01443-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bleves S, Viarre V, Salacha R, Michel GP, Filloux A, Voulhoux R. 2010. Protein secretion systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a wealth of pathogenic weapons. Int J Med Microbiol 300:534–543. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Mulcahy H, Charron-Mazenod L, Lewenza S. 2010. Pseudomonas aeruginosa produces an extracellular deoxyribonuclease that is required for utilization of DNA as a nutrient source. Environ Microbiol 12:1621–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Funken H, Knapp A, Vasil ML, Wilhelm S, Jaeger KE, Rosenau F. 2011. The lipase LipA (PA2862) but not LipC (PA4813) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa influences regulation of pyoverdine production and expression of the sigma factor PvdS. J Bacteriol 193:5858–5860. doi: 10.1128/JB.05765-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Jyot J, Balloy V, Jouvion G, Verma A, Touqui L, Huerre M, Chignard M, Ramphal R. 2011. Type II secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: in vivo evidence of a significant role in death due to lung infection. J Infect Dis 203:1369–1377. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Golovkine G, Faudry E, Bouillot S, Voulhoux R, Attree I, Huber P. 2014. VE-cadherin cleavage by LasB protease from Pseudomonas aeruginosa facilitates type III secretion system toxicity in endothelial cells. PLoS Pathog 10:e1003939. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ball G, Antelmann H, Imbert PR, Gimenez MR, Voulhoux R, Ize B. 2016. Contribution of the twin arginine translocation system to the exoproteome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci Rep 6:27675. doi: 10.1038/srep27675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Alrahman MA, Yoon SS. 2017. Identification of essential genes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa for its growth in airway mucus. J Microbiology 55:68–74. doi: 10.1007/s12275-017-6515-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zaborina O, Holbrook C, Chen Y, Long J, Zaborin A, Morozova I, Fernandez H, Wang Y, Turner JR, Alverdy JC. 2008. Structure-function aspects of PstS in multi-drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Pathog 4:e43. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ball G, Viarre V, Garvis S, Voulhoux R, Filloux A. 2012. Type II-dependent secretion of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa DING protein. Res Microbiol 163:457–469. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Cadoret F, Ball G, Douzi B, Voulhoux R. 2014. Txc, a new type II secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA7, is regulated by the TtsS/TtsR two-component system and directs specific secretion of the CbpE chitin-binding protein. J Bacteriol 196:2376–2386. doi: 10.1128/JB.01563-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.de Groot A, Koster M, Gerard-Vincent M, Gerritse G, Lazdunski A, Tommassen J, Filloux A. 2001. Exchange of Xcp (Gsp) secretion machineries between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pseudomonas alcaligenes: species specificity unrelated to substrate recognition. J Bacteriol 183:959–967. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.3.959-967.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Karaba SM, White RC, Cianciotto NP. 2013. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia encodes a type II protein secretion system that promotes detrimental effects on lung epithelial cells. Infect Immun 81:3210–3219. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00546-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.DuMont AL, Karaba SM, Cianciotto NP. 2015. Type II secretion-dependent degradative and cytotoxic activities mediated by the Stenotrophomonas maltophilia serine proteases StmPr1 and StmPr2. Infect Immun 83:3825–3837. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00672-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Zhang F, Chen J, Chi Z, Wu LF. 2006. Expression and processing of Vibrio anguillarum zinc-metalloprotease in Escherichia coli. Arch Microbiol 186:11–20. doi: 10.1007/s00203-006-0118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]