Abstract

Small-subunit (SSU) rRNA gene sequences were obtained by PCR from 12 Blastocystis isolates from humans, rats, and reptiles for which elongation factor 1α (EF-1α) gene sequences are already available. These new sequences were analyzed by the Bayesian method in a broad phylogeny including, for the first time, all Blastocystis sequences available in the databases. Phylogenetic trees identified seven well-resolved groups plus several discrete lineages that could represent newly defined clades. Comparative analysis of SSU rRNA- and EF-1α-based trees obtained by maximum-likelihood methods from a restricted sampling (13 isolates) revealed overall agreement between the two phylogenies. In spite of their morphological similarity, sequence divergence among Blastocystis isolates reflected considerable genetic diversity that could be correlated with the existence of potentially ≥12 different species within the genus. Based on this analysis and previous PCR-based genotype classification data, six of these major groups might consist of Blastocystis isolates from both humans and other animal hosts, confirming the low host specificity of Blastocystis. Our results also strongly suggest the existence of numerous zoonotic isolates with frequent animal-to-human and human-to-animal transmissions and of a large potential reservoir in animals for infections in humans.

Blastocystis hominis is an anaerobic enteric parasite that inhabits the human intestinal tract. Although the role of B. hominis as a human pathogen has been criticized mainly because of the impossibility of eliminating all other causes of symptoms, it is commonly considered a causative agent of intestinal disease (for reviews, see references 10, 14, 36, and 39). Moreover, B. hominis is probably the most frequent protozoan reported in human fecal samples (45), with a prevalence ranging between 30 and 50% in some developing countries (36). In addition, infection with B. hominis appears to be common and more severe in immunocompromised patients (12, 30, 40).

Microorganisms identified as Blastocystis have also been isolated from a wide range of animals, such as nonhuman primates, pigs, cattle, birds, amphibians, and, less frequently, rodents, reptiles, and insects (for reviews, see references 2 and 10), but the taxonomy within the genus Blastocystis remains controversial. Indeed, most Blastocystis isolates have remained indistinguishable from B. hominis by light and electron microscopy. However, new species have been differentiated from B. hominis in different nonhuman hosts (8, 11, 34, 41), but until further confirmation using molecular data is available, B. hominis defines the parasite isolated from humans and Blastocystis sp. represents those isolated from other animal hosts.

Although the designations of individual species of Blastocystis have not been adequately resolved, extensive genetic diversity among both B. hominis and Blastocystis sp. isolates has been described mostly by random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) (3-5, 22, 46-50) and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analyses of PCR-amplified small-subunit (SSU) rRNA (3-5, 9, 13, 19, 20, 25, 35, 49). By RFLP, at least 10 subspecies, or ribodemes (the term used to describe populations that share the same riboprint pattern), have been characterized (13, 25, 48). Some of these different ribodemes were found in human hosts, which raised the possibility that more than one species of Blastocystis infects humans and suggests the existence of zoonotic strains of this parasite. Clark (13) and Yoshikawa et al. (46, 47) showed that two Blastocystis isolates, one from guinea pigs and one from chickens, exhibited RFLP profiles or RAPD patterns similar to those observed in some B. hominis strains, suggesting animal-to-human or human-to-animal transmission. This is supported by several studies (14, 31, 32) confirming that animal and food handlers are more likely to be infected. Recently, diagnostic PCR using known sequenced-tagged site (STS)-specific primer sets was developed to distinguish and classify Blastocystis populations into seven different subtypes based on genomic similarity (47, 48, 50). By this method, Abe et al. (3-5) suggested the existence of numerous zoonotic isolates from various animal hosts. However, molecular data obtained by RAPD-, RFLP-, and PCR-based genotype classification reflected limited sequence divergence among taxa and provided only preliminary information on genetic relatedness between human and nonhuman isolates.

Thus, molecular phylogenies were recently constructed from nearly full-length SSU rRNA (1, 7, 29, 43, 49, 50) and elongation factor 1α (EF-1α) gene sequences (18). These analyses suggested low host specificity for Blastocystis and the zoonotic potential of the parasite. However, the restricted number of Blastocystis sequences obtained or phylogenetically analyzed from human and nonhuman hosts was insufficient to determine the extent to which the parasite can be transmitted among host species and the potential reservoir for infection of humans. In addition, comparative phylogenetic studies have demonstrated that, depending on the group in question, single-gene phylogenies based on either RNA or protein can be very misleading. It was therefore critical to compare the topology of Blastocystis SSU rRNA-based analyses with those of protein-coding genes.

In this study, we obtained almost full-length SSU rRNA gene sequences of 12 Blastocystis isolates from humans, rats, and reptiles for which EF-1α gene sequences are available (18). These sequences were used in a large phylogenetic analysis including 78 other Blastocystis sequences available in databases. For the first time for Blastocystis, this allowed the parallel construction of phylogenetic trees from two molecular markers with the same sample of isolates, comparing protein (EF-1α)- and rRNA-based trees. All these data allowed us to clarify genetic diversity, species identities, and host specificities among Blastocystis isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source of Blastocystis and DNA extraction.

Axenic cultures of 12 Blastocystis isolates (Table 1) from humans, rats, and reptiles were maintained in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium supplemented with 10% horse serum, as previously described (17). Genomic-DNA isolation was performed as described by Ho et al. (18). The DNA preparations were treated with RNase A at 37°C for 30 min and kept at −20°C until they were used.

TABLE 1.

Origins of Blastocystis isolates analyzed in our study and accession numbers of their SSU rRNA gene sequences

| Isolate | Species | Host | Country of origin | Reference | Clonesa | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | B. hominis | Human | Singapore | 7; Present study | a, b | AF408427, AY590105 |

| C | B. hominis | Human | Singapore | Present study | AY590106 | |

| E | B. hominis | Human | Singapore | Present study | AY590107 | |

| G | B. hominis | Human | Singapore | Present study | AY590108 | |

| H | B. hominis | Human | Singapore | Present study | AY590109 | |

| S | B. hominis | Human | Pakistan | Present study | AY590110 | |

| HE87-1 | B. hominis | Human | Japan | 6 | a, b | AB023499, AB023578 |

| HG00-10 | B. hominis | Human | Japan | 50 | AY244619 | |

| HG00-12 | B. hominis | Human | Japan | 50 | AY244620 | |

| HJ00-4 | B. hominis | Human | Japan | 50 | AF408425 | |

| HJ00-5 | B. hominis | Human | Japan | 50 | AF408426 | |

| HJ01-7 | B. hominis | Human | Japan | 50 | AY244621 | |

| HJ96-1 | B. hominis | Human | Japan | 7 | AB070987 | |

| HJ96A-26 | B. hominis | Human | Japan | 7 | a, b, c | AB070988, AB091234 and -5 |

| HJ96A-29 | B. hominis | Human | Japan | 7 | AB070989 | |

| HJ96AS-1 | B. hominis | Human | Japan | 7 | a, b, c, d | AB070990, AB091236 to -8 |

| HJ97-2 | B. hominis | Human | Japan | 7 | a, b | AB070991, AB091239 |

| HT98-1 | B. hominis | Human | Thailand | 7 | AB070992 | |

| HV93-13 | B. hominis | Human | Japan | 7 | a,b | AB070986, AB091233 |

| Nand II | B. hominis | Human | United States | 33 | U51151 | |

| B. hominis | Human | France | 29 | AY135402 | ||

| B. hominis | Human | Thailand | 43 | AF439782 | ||

| JM92-2 | Blastocystis sp. | Monkey | Japan | 7 | AB070997 | |

| MJ99-116 | Blastocystis sp. | Monkey | Japan | 1 | AB107969 | |

| MJ99-123 | Blastocystis sp. | Monkey | Japan | 1 | Identical to AB107968 | |

| MJ99-130 | Blastocystis sp. | Monkey | Japan | 1 | Identical to AB107969 | |

| MJ99-132 | Blastocystis sp. | Monkey | Japan | 1 | AB107970 | |

| MJ99-424 | Blastocystis sp. | Monkey | Japan | 1 | AB107967 | |

| MJ99-568 | Blastocystis sp. | Monkey | Japan | 1 | AB107968 | |

| PJ99-148 | Blastocystis sp. | Pig | Japan | 1 | Identical to AB107964 | |

| PJ99-154 | Blastocystis sp. | Pig | Japan | 1 | AB107961 | |

| PJ99-162 | Blastocystis sp. | Pig | Japan | 1 | AB107963 | |

| PJ99-172 | Blastocystis sp. | Pig | Japan | 1 | AB107962 | |

| PJ99-188 | Blastocystis sp. | Pig | Japan | 1 | AB107964 | |

| SY94-3 | Blastocystis sp. | Pig | Japan | 7 | a, b | AB070998, AB091248 |

| SY94-7 | Blastocystis sp. | Pig | Japan | 7 | a, b, c | AB070999, AB091249 and -50 |

| Blastocystis sp. | Pig | Thailand | 43 | AF538348 | ||

| Blastocystis sp. | Pig | Czech Republic | 29 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | AY135403-6 | |

| CJ99-284 | Blastocystis sp. | Cattle | Japan | 1 | AB107966 | |

| CJ99-344 | Blastocystis sp. | Cattle | Japan | 1 | Identical to AB107961 | |

| CJ99-350 | Blastocystis sp. | Cattle | Japan | 1 | Identical to AB107964 | |

| CJ99-353 | Blastocystis sp. | Cattle | Japan | 1 | Identical to AB107963 | |

| CJ99-363 | Blastocystis sp. | Cattle | Japan | 1 | AB107965 | |

| Blastocystis sp. | Horse | Thailand | 43 | AF538349b | ||

| CK86-1 | Blastocystis sp. | Chicken | Japan | 7 | a, b, c | AB070993, AB091240 and -1 |

| CK92-4 | Blastocystis sp. | Chicken | Japan | 7 | a, b | AB070994, AB091242 |

| Blastocystis sp. | Chicken | France | 29 | 1, 2 | AY135409 and -10 | |

| Blastocystis sp. | Duck | France | 29 | AY135412 | ||

| Blastocystis sp. | Turkey | France | 29 | AY135411 | ||

| QQ93-3 | Blastocystis sp. | Quail | Japan | 7 | a, b | AB070995, AB091243 |

| QQ98-4 | Blastocystis sp. | Quail | Japan | 7 | a, b, c, d, e | AB070996, AB091244 to -7 |

| BJ99-310 | Blastocystis sp. | Partridge | Japan | 1 | AB107972 | |

| BJ99-319 | Blastocystis sp. | Pheasant | Japan | 1 | AB107971 | |

| BJ99-569 | Blastocystis sp. | Goose | Japan | 1 | AB107973 | |

| RN94-9 | Blastocystis sp. | Rat | Japan | 7 | a, b | AB071000, AB091251 |

| Blastocystis sp. | Rat | France | 29 | 1, 2 | AY135407 and -8 | |

| S1 | B. ratti | Rat | Singapore | Present study | AY590111 | |

| WR1 | B. ratti | Rat | Singapore | Present study | AY590113 | |

| WR2 | B. ratti | Rat | Singapore | Present study | AY590114 | |

| NIH:1295:1 | Blastocystis sp. | Guinea pig | United States | 33 | U51152 | |

| Blastocystis sp. | Guinea pig | United States | 26 | U26177 | ||

| B. cycluri | Lizard | Singapore | Present study | AY590116 | ||

| B. lapemi | Sea snake | Singapore | Present study | AY590115 | ||

| B. pythoni | Python | Singapore | Present study | AY590112 |

Clones with different sequences obtained from the same isolate.

Partial sequence.

PCR amplification, cloning, and sequencing.

SSU ribosomal DNA (rDNA) genes from each Blastocystis isolate were amplified using the eukaryote-specific primers A and B (without 5′ restriction site linkers) designed by Medlin et al. (27). PCRs were carried out according to standard conditions for Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Groningen, The Netherlands). After the denaturation step at 94°C for 5 min, 40 cycles of amplification were performed with a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 apparatus (Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France) as follows: 1 min at 94°C, 2 min at 48°C, and 3 min at 72°C. The final extension step was continued for 15 min. The products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and the band of the expected size (∼1,800 bp) was purified using the QIAEX II Gel Extraction kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The purified PCR products were cloned in the T vector pCR 2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen) and amplified in TOP10 competent cells. Minipreparations of plasmid DNA were done using the QIAprep Spin Miniprep kit (QIAGEN). Clones containing an insert were sequenced on both strands by primer walking using the Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) and an automated PRISM 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

Phylogenetic analyses.

SSU rRNA gene sequences from Blastocystis isolates obtained in this study were aligned with a set of eukaryotic sequences including 78 other Blastocystis isolates retrieved from databases (Table 1) using the ARB package (http://www.arb-home.de/) according to conservation of primary and secondary structures. EF-1α amino acid sequences of Blastocystis isolates available in databases were aligned by use of the BioEdit version 5.0.9 package (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html). In each analysis, we restricted phylogenetic inference to sites that could be unambiguously aligned. Full-length alignments and sites used in analyses are available upon request. Phylogenetic analyses of SSU rRNA and EF-1α sequences were carried out using MrBAYES version 2.01 (21). Bayesian analyses of the SSU rRNA datasets were performed using the GTR (general time reversible) +Γ (gamma distribution of rates with four rate categories) +I (proportion of invariant sites) model of sequence evolution, with base frequencies, the proportion of invariant sites, and the shape parameter alpha of the Γ distribution estimated from the data. The data set of EF-1α amino acid sequences was analyzed as described above using the JTT amino acid replacement model (24). In all Bayesian analyses, starting trees were random, four simultaneous Markov chains were run for 500,000 generations, burn-in values were set at 30,000 generations (based on empirical values of stabilizing likelihoods), and trees were sampled every 100 generations. Bayesian posterior probabilities were calculated using a Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling approach (15) implemented in MrBAYES version 2.01. Phylogenetic analyses were also performed for EF-1α and restricted SSU rRNA data sets by using TREE-PUZZLE version 5.0 (38) and 10,000 quartet puzzling steps. The JTT and HKY (16) models were used for the amino acid and SSU rRNA data sets, respectively. The proportion of invariant sites and the alpha shape parameter were estimated from the data. For the large SSU rRNA data set, analyses were carried out both including and excluding outgroups to determine if this substantially affected relationships within Blastocystis isolates.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences obtained in this study have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AY590105 to AY590116.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Phylogenetic analysis of Blastocystis SSU rRNA gene sequences.

The amplification of the SSU rDNA coding regions of the 12 Blastocystis isolates from humans, rats, and reptiles analyzed in this study produced a DNA fragment of the expected size (∼1.8 kb in length) as determined by gel electrophoresis. This fragment was eluted and cloned into the pCR 2.1-TOPO vector, and two clones were completely sequenced for each isolate, which always proved to be identical. Each of the new SSU rRNA gene sequences showed the highest similarity (from 82.6 to 99.9%) to homologous sequences of the other Blastocystis isolates reported so far (Table 1). In the common part of our alignment, the lengths of all Blastocystis SSU rRNA gene sequences available in databases and obtained in this work range from 1,666 to 1,777 bp, and the G+C contents range from 53.9 to 64.4%.

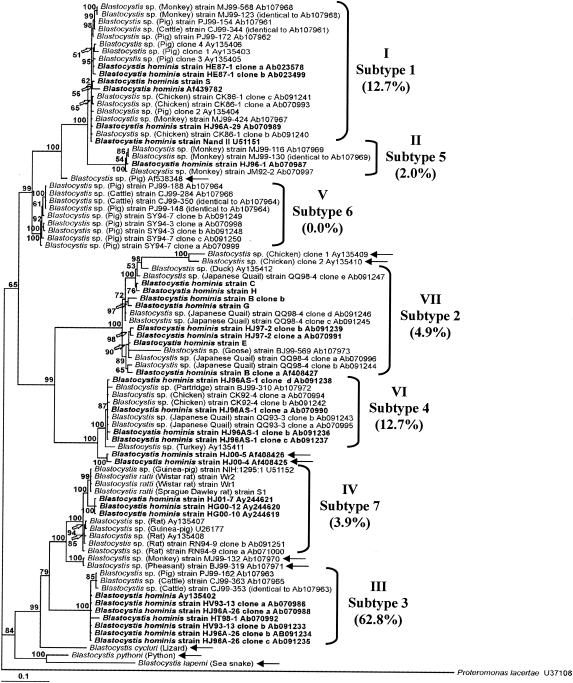

SSU rRNA gene sequences obtained in this study were added to an existing database of 77 other Blastocystis sequences (Table 1). Tree construction was performed using the stramenopile Proteromonas lacertae, a commensal flagellate of reptiles and amphibians, as the outgroup in view of its position closely related to Blastocystis in previous phylogenetic studies (26, 28, 29, 33). This data set included 1,563 unambiguously aligned positions, which we analyzed by the maximum-likelihood method using MrBAYES. The rooted maximum-likelihood tree (Fig. 1) identified seven clades called groups I to VII, each highly supported by Bayesian posterior probabilities (BP) of 100% plus several discrete lineages. In a subsequent analysis from which the outgroup was excluded, permitting the inclusion of more characters (1,606 positions), no significant deviation from this topology was noted (data not shown). We also noted that there was only limited or moderate support for the relative branching order within most of the groups.

FIG. 1.

Maximum-likelihood phylogeny of Blastocystis isolates inferred from SSU rRNA gene sequences. P. lacertae served as the outgroup. Bayesian posterior probabilities are given as percentages near the individual nodes. Nodes with values of <50% are not shown. Blastocystis isolates from humans are indicated in boldface. Groups I to VII are those previously described by Arisue et al. (7), and the arrows indicate isolates for which classification is uncertain. Scale bar, 0.1 substitutions (corrected) per base pair.

The major groups identified in our analysis were in agreement with those defined in recent SSU rRNA-based studies that included a more restricted sample of Blastocystis isolates (1, 7). For this reason, we have conserved the same numbering of the groups used by these authors in order to facilitate the comparison of both SSU rRNA-based trees. In addition, as stated by Abe (1), Arisue et al. (7), and Yoshikawa et al. (49, 50), there is a correlation between these phylogenetically different groups and the subtypes identified by PCR-based genotype classification. Indeed, groups I to VII correspond to subtypes 1, 5, 3, 7, 6, 4, and 2, respectively, as indicated in Fig. 1.

Group I (subtype 1) mostly unites Blastocystis isolates from pigs, cattle, monkeys, and humans. In a subsequent phylogenetic analysis restricted to 986 positions, we observed that the partial SSU rDNA sequence of a horse isolate was also included in this group (data not shown). We also note that group I is closely related to group II (subtype 5), which includes only primate and human isolates. In addition, the higher-order clade of groups I, II, and V (subtype 6, which is composed of pig and cattle isolates) cluster together with strong BP (99%). Within this large group I-II-V, we also describe the emergence of a discrete lineage composed only of a single pig isolate (accession number AF538348) that could be the only known representative of a new clade. Interestingly, the large group I-II-V is mostly restricted to mammalian isolates (humans, monkeys, bovids, equids, and pigs) with rodents excluded. However, it also includes the isolate CK86-1 from chickens, which was already identified as a zoonotic strain (12, 45, 46). This isolate occupies a position distant from the other bird isolates analyzed in this study and included in groups VI and VII.

Indeed, groups VI (subtype 4) and VII (subtype 2) strongly unite some isolates from humans and most of the isolates from birds, with the exception of isolates CK86-1 from chickens (group I) and BJ99-319 from pheasants. We also note that distinct isolates from both Japanese quails and chickens are represented in each of these two different groups. Moreover, as previously stated by Yoshikawa et al. (50), the isolates HJ00-4 and HJ00-5 from humans are clustered in an additional monophyletic clade at the base of group VI. However, both isolates HJ00-4 and HJ00-5 composing this new lineage were negative with all STS primers used in PCR-based genotype classification, suggesting that the isolates HJ00-4 and HJ00-5 do not belong to subtype 4 and could represent a new genotype (50). This hypothesis could be also tested with STS primers for two isolates from chickens (accession numbers AY135409 and AY135410) that could form another new clade.

Additional clades are represented by groups III (subtype 3) and IV (subtype 7). The two groups cluster together with a moderate BP of 79%. Group IV is mostly composed of isolates from rodents but also includes three human isolates, whereas group III unites four isolates from humans and three isolates from cattle and pigs. The isolates MJ99-132 and BJ99-319, from monkeys and pheasants, respectively, are clustered in an additional monophyletic clade, which is strongly united with group IV (BP value, 100%). Although both isolates MJ99-132 and BJ99-319 exhibit the same subtype 7 as isolates composing group IV (1), this clade could represent a new well-defined phylogenetic group.

At the base of the higher-order clade III-IV, we note the emergence of two additional discrete lineages, composed of the three isolates from reptiles, that could represent new phylogenetic groups. These isolates form a polyphyletic group. Indeed, Blastocystis cycluri, isolated from lizards, clusters together with isolates of groups III and IV with high support (BP value, 99%), whereas Blastocystis lapemi and Blastocystis pythoni, isolated from snakes, exhibit a derived position and group together with BP of 100%. This dichotomy observed between Blastocystis isolates from reptiles could naturally reflect the evolutionary divergence between their respective hosts.

Comparative phylogeny of Blastocystis isolates inferred from EF-1α and SSU rRNA gene sequences.

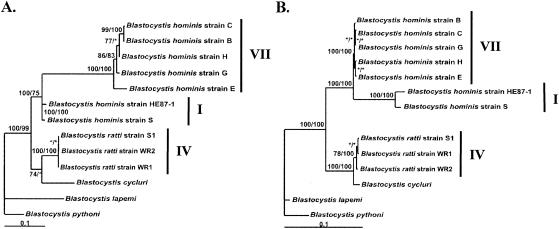

Comparison of SSU rRNA gene sequences confirms that Blastocystis organisms are genetically highly divergent in spite of their morphological identity and defines a large number of potential phylogenetic groups among Blastocystis isolates. However, congruence between independent data sets is the strongest argument in favor of a given topology, so the SSU rRNA tree of Blastocystis isolates needs to be compared with phylogenies based on other molecules. To this end, we obtained SSU rRNA gene sequences from 12 Blastocystis isolates for which a major part of the coding region of the EF-1α gene had already been sequenced (18). SSU rRNA and EF-1α sequences were also available for the human isolate HE87-1 and were added to our database. This allowed us to compare SSU rRNA- and EF-1α-based trees with the same sampling of 13 Blastocystis isolates.

As shown in Fig. 1 and 2, 10 of the 13 isolates studied in this comparative analysis represented three groups (I, IV, and VII), whereas the three other isolates from reptiles composed two newly described clades. For EF-1α and restricted SSU rRNA data sets, phylogenetic analyses were performed using 289 amino acid and 1,644 nucleotide aligned positions, respectively, and unrooted maximum-likelihood trees were constructed using both MrBAYES and TREE-PUZZLE. Identity matrices calculated from both alignments revealed that sequence similarity among all pairs ranged from 83.0 to 99.9% and 88.5 to 100% for the SSU rRNA and EF-1α data sets, respectively (data not shown), and indicated that EF-1α sequences are more highly conserved than SSU rRNA sequences among Blastocystis isolates.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of unrooted maximum-likelihood trees inferred from SSU rRNA (A) and EF-1α (B) sequences for the same sample of Blastocystis isolates. EF-1α nucleotide sequences are available in the GenBank database (accession numbers AF090737, AF091356 to AF091365, AF223379, and D64080). The numbers at the nodes correspond to Bayesian posterior probabilities given as percentages (left of the slash) and percentages of occurrence in 10,000 quartet puzzling steps (right of the slash). Asterisks designate nodes with values of <50%. Scale bars, 0.1 substitutions (corrected) per site.

The topologies of SSU rRNA- (Fig. 2A) and EF-1α-based (Fig. 2B) trees are identical for the taxa selected. We recovered with high support the well-defined groups I, IV, and VII described above with the larger SSU rRNA data set and confirmed the large genetic diversity between groups I and VII, both of which include human isolates. Among these clades, better resolution is observed within group VII in the SSU rRNA- than in the EF-1α-based tree. This is in agreement with the percentage sequence identity calculated for each marker. Both trees also emphasize the polyphyly of isolates from reptiles, which emerge as two independent lineages. In the SSU rRNA-based tree, B. cycluri clusters with rodent isolates with low support values, whereas the same grouping is strongly supported (100% by both reconstruction methods) in the EF-1α-based tree. Overall, phylogenetic trees of Blastocystis isolates based on SSU rRNA and EF-1α sequences are well supported and entirely congruent with each other. Thus, our data suggest that EF-1α should be a valuable complement to SSU rRNA to elucidate phylogenetic relationships among Blastocystis isolates.

Identification of species and zoonotic potential of Blastocystis organisms.

New species designations in the Blastocystis genus were proposed for isolates from different nonhuman hosts (8, 11, 34, 41) on the basis of questionable criteria, such as differences in the hosts of origin, growth characteristics, and electrophoretic karyotypes. However, it is clear that these differences alone are not sufficient for the proposal of new species (23, 36, 39, 44). On the other hand, the genetic diversity observed in this work, as in previous molecular studies (1, 7, 29, 43, 49, 50), among Blastocystis isolates strongly suggests that the genus consists of several species.

Indeed, the evolutionary distances observed among the different groups defined in our phylogenetic analysis are comparable to or greater than those observed among other stramenopile species (data not shown [obtained from an alignment including 1,458 unambiguous positions]). In addition, it is likely that each of the three reptile isolates analyzed here could represent a new species, as could one isolate from chickens (accession numbers AY135409 and AY135410) and one isolate from pigs (accession number AF538348). In contrast, it seems unlikely from our data that the newly described lineage composed of the isolates MJ99-132 and BJ99-319, from monkeys and pheasants, respectively, could be elevated to the species rank. Moreover, both isolates have been shown to exhibit subtype 7 and have been included in group IV (1). In addition, although the human isolates HJ00-4 and HJ00-5 could represent a new genotype (50), the evolutionary distances calculated between the closely related sequences of the two isolates and those composing group VI are too short to consider isolates HJ00-4 and HJ00-5 representatives of a new Blastocystis species. Overall, the genus Blastocystis could include at least 12 different species, reflective of the great genetic diversity observed among isolates. However, such taxonomic statements should be regarded cautiously until further confirmation is obtained, since an accelerated evolutionary rate for Blastocystis SSU rRNA genes cannot yet be ruled out. Additional studies involving more isolates and other conserved genes, such as that for EF-1α, should help to clarify taxonomic relationships among these organisms.

As demonstrated in our study, groups I to VII are not host specific, and most of them comprise isolates from humans and other animals, suggesting that Blastocystis may be cross-infective among various animal hosts. Indeed, as previously stated by Arisue et al. (7) based on a restricted sample of isolates, the relationships among hosts are not in agreement with the genuine phylogeny of the animals in any part of our Blastocystis tree, and this could be explained by the existence of numerous zoonotic isolates. Thus, our study raises questions about the transmission of Blastocystis. The fecal-oral route is considered to be the main mode of transmission, but food-borne and waterborne transmission of Blastocystis via untreated water or poor sanitary conditions have also been suggested (reviewed in references 10, 36, and 39), although not confirmed experimentally. Human-to-human transmission of B. hominis infection between two small communities has been proposed (48), and experimental cross-transmission has been achieved in rodents with Blastocystis isolated from humans (for reviews, see references 10 and 36). Moreover, people working closely with animals in zoos and abattoirs and food handlers (14, 31, 32) are at higher risk of acquiring Blastocystis infection. In addition, transmission of Blastocystis organisms could also be frequent between animals, especially in confined areas, such as zoological gardens and circuses, where fecal contamination of grass and fodder is common (37, 42). Thus, in light of our data and those from the literature, it is reasonable to speculate that contamination by Blastocystis organisms can occur via animal-to-animal, human-to-animal, and animal-to-human routes. However, given the large number of potential zoonotic isolates found in our study, it remains difficult to identify the host origins and transmission routes of some isolates.

As stated above, groups VI (genotype 4) and VII (genotype 2) included only bird and human isolates. In a recent study, Yoshikawa et al. (50) studied the prevalence of each Blastocystis genotype in five different countries. These values are indicated in Fig. 1 and were based on a total of 99 human isolates. These authors showed that genotypes 4 and 2 represented 17.6% of the human isolates tested. Therefore, these results suggest that human isolates of both groups are zoonotic and could represent examples of animal-to-human transmission. In addition, since the same Blastocystis species is able to infect several bird species, animal-to-animal transmission could also be proposed. Group I (genotype 1) is composed only of mammalian isolates (pig, cattle, monkey, and human), with the exception of the chicken isolate CK86-1. The prevalence of human isolates in this group is 12.7%. According to the diversity of hosts found in this group, it is likely composed mostly of zoonotic isolates. Although the host origins of the Blastocystis species representative of this group remain extremely difficult to define, they are probably mammalian. Therefore, transmissions both among bovines, pigs, monkeys, and humans and from mammals to birds for the chicken isolate CK86-1 could be suggested. Group IV (genotype 7) is composed mostly of rodent isolates. Thus, the same Blastocystis species (probably Blastocystis ratti) could colonize both rats and guinea pigs. Moreover, few human isolates have been shown to possess the same genotype 7 (3.9%). Therefore, this grouping of rodent and human isolates could reflect animal-to-human transmission. Finally, in accordance with its prevalence among human isolates (62.8%), group III (genotype 3) could represent a specific genotype of human origin. Isolates from pigs and cattle sharing genotype 3 are likely to reflect contamination by humans. These preliminary hypotheses concerning the zoonotic potential of these organisms could be reinforced by the analysis of additional isolates from different hosts.

In conclusion, our data confirm that extensive genetic diversity exists among Blastocystis isolates from humans and other animals and suggest that more than one species could infect humans. Moreover, our findings emphasize the low host specificity of this organism and indicate that numerous human Blastocystis infections may be of zoonotic origin. Thus, the number and range of animals found to be infected by Blastocystis may represent a huge potential reservoir for infection of humans.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Institut Pasteur de Lille, the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, the Ecole Vétérinaire de Lyon, and the “Programme Trans-Zoonoses 2002-2004” (INRA—Département de Santé Animale).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe, N. 2004. Molecular and phylogenetic analysis of Blastocystis isolates from various hosts. Vet. Parasitol. 120:235-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abe, N., M. Nagoshi, K. Takami, Y. Sawano, and H. Yoshikawa. 2002. A survey of Blastocystis sp. in livestock, pets, and zoo animals in Japan. Vet. Parasitol. 106:203-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abe, N., Z. Wu, and H. Yoshikawa. 2003. Molecular characterization of Blastocystis isolates from birds by PCR with diagnosis primers and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the small subunit ribosomal RNA gene. Parasitol. Res. 89:393-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abe, N., Z. Wu, and H. Yoshikawa. 2003. Molecular characterization of Blastocystis isolates from primates. Vet. Parasitol. 113:321-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abe, N., Z. Wu, and H. Yoshikawa. 2003. Zoonotic genotypes of Blastocystis hominis detected in cattle and pigs by PCR with diagnostic primers and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the small subunit ribosomal RNA gene. Parasitol. Res. 90:124-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arisue, N., T. Hashimoto, H. Yoshikawa, Y. Nakamura, G. Nakamura, F. Nakamura, T. A. Yano, and M. Hasegawa. 2002. Phylogenetic position of Blastocystis hominis and of stramenopiles inferred from multiple molecular sequence data. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 49:42-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arisue, N., T. Hashimoto, and H. Yoshikawa. 2003. Sequence heterogeneity of the small subunit ribosomal RNA genes among Blastocystis isolates. Parasitology 126:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belova, L. M., and L. A. Kostenko. 1990. Blastocystis galli sp. n. (Protista, Rhizopoda) from the intestine of domestic hens. Parazitologiia 24:164-168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Böhm-Gloning, B., J. Knobloch, and B. Walderich. 1997. Five subgroups of Blastocystis hominis isolates from symptomatic and asymptomatic patients revealed by restriction site analysis of PCR-amplified 16S-like rDNA. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2:771-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boreham, P. F. L., and D. J. Stenzel. 1993. Blastocystis in humans and animals: morphology, biology, and epizootiology. Adv. Parasitol. 32:1-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, X. Q., M. Singh, L. C. Ho, S. W. Tan, G. C. Ng, K. T. Moe, and E. H. Yap. 1997. Description of a Blastocystis species from Rattus norvegicus. Parasitol. Res. 83:313-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cirioni, O., A. Giacometti, D. Drenaggi, F. Ancarani, and G. Scalise. 1999. Prevalence and clinical relevance of Blastocystis hominis in diverse patient cohorts. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 15:389-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark, C. G. 1997. Extensive genetic diversity in Blastocystis hominis. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 87:79-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doyle, P. W., M. M. Helgason, R. G. Mathias, and E. M. Proctor. 1990. Epidemiology and pathogenicity of Blastocystis hominis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:116-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green, P. J. 1995. Reversible jump Markov Chain Monte Carlo computation and Bayesian model determination. Biometrika 82:711-732. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasegawa, M., H. Kishino, and T. Yano. 1985. Dating of the human-ape splitting by a molecular clock of mitochondrial DNA. J. Mol. Evol. 22:160-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho, L. C., M. Singh, K. Suresh, G. C. Ng, and E. H. Yap. 1993. Axenic culture of Blastocystis hominis in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium. Parasitol. Res. 79:614-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho, L. C., A. Armugam, K. Jeyaseelan, E. H. Yap, and M. Singh. 2000. Blastocystis elongation factor-1α: genomic organization, taxonomy and phylogenetic relationships. Parasitology 121:135-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho, L. C., K. Jeyaseelan, and M. Singh. 2001. Use of the elongation factor-1α gene in a polymerase chain reaction-based restriction-fragment-length polymorphism analysis of genetic heterogeneity among Blastocystis species. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 112:287-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoevers, J., P. Holman, K. Logan, M. Hommel, R. Ashford, and K. Snowden. 2000. Restriction-fragment-length polymorphism analysis of small-subunit rRNA genes of Blastocystis hominis isolates from geographically diverse human hosts. Parasitol. Res. 86:57-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huelsenbeck, J. P., and F. Ronquist. 2001. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 17:754-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Init, I., J. W. Mak, H. S. Lokman, and H. S. Yong. 1999. Strain differences in Blastocystis isolates as detected by a single set of polymerase chain reaction primers. Parasitol. Res. 85:131-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isaac-Renton, J. L., C. Cordeiro, K. Sarafis, and H. Shahriari. 1993. Characterization of Giardia duodenalis isolates from a waterborne outbreak. J. Infect. Dis. 167:431-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones, D. T., W. R. Taylor, and J. M. Thornton. 1992. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput. Appl. Biol. Sci. 8:275-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaneda, Y., N. Horiki, X. J. Cheng, Y. Fujita, M. Maruyama, and H. Tachibana. 2001. Ribodemes of Blastocystis hominis isolated in Japan. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 65:393-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leipe, D. D., S. M. Tong, C. L. Goggin, S. B. Slemenda, N. J. Pieniazek, and M. L. Sogin. 1996. 16S-like rDNA sequences from Developayella elegans, Labyrinthuloides haliotidis, and Proteromonas lacertae confirm that the stramenopiles are a primarily heterotrophic group. Eur. J. Protistol. 32:449-458. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Medlin, L., H. J. Elwood, S. Stickel, and M. L. Sogin. 1988. The characterization of enzymatically amplified eukaryotic 16S-like rRNA-coding regions. Gene 71:491-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moriya, M., T. Nakayama, and I. Inouye. 2000. Ultrastructure and 18S rDNA sequence analysis of Wobblia lunata gen. et sp. nov., a new heterotrophic flagellate (stramenopiles, incertae sedis). Protist 151:41-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noël, C., C. Peyronnet, D. Gerbod, V. P. Edgcomb, P. Delgado-Viscogliosi, M. L. Sogin, M. Capron, E. Viscogliosi, and L. Zenner. 2003. Phylogenetic analysis of Blastocystis isolates from different hosts based on the comparison of small-subunit rRNA gene sequences. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 126:119-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prasad, K. N., V. L. Nag, T. N. Dhole, and A. Ayyagari. 2000. Identification of enteric pathogens in HIV-positive patients with diarrhoea in northern India. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 18:23-26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajah Salim, H., G. S. Kumar, S. Vellayan, J. W. Mak, A. K. Anuar, I. Init, G. D. Vennila, R. Saminathan, and K. Ramakrishnan. 1999. Blastocystis in animal handlers. Parasitol. Res. 81:703-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Requena, I., Y. Hernandez, M. Ramsay, C. Salazar, and R. Devera. 2003. Prevalence of Blastocystis hominis among food handlers from Caroni municipality, Bolivar state, Venezuela. Cad. Saude Publica 19:1721-1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silberman, J. D., M. L. Sogin, D. D. Leipe, and C. G. Clark. 1996. Human parasite finds taxonomic home. Nature 380:398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh, M., L. C. Ho, A. L. L. Yap, G. C. Ng, S. W. Tan, K. T. Moe, and E. H. Yap. 1996. Axenic culture of reptilian Blastocystis isolates in monophasic medium and speciation by karyotypic typing. Parasitol. Res. 82:165-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snowden, K., K. Logan, C. Blozinski, J. Hoevers, and P. Holman. 2000. Restriction-fragment-length polymorphism analysis of small-subunit rRNA genes of Blastocystis isolates from animal hosts. Parasitol. Res. 86:62-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stenzel, D. J., and P. F. L. Boreham. 1996. Blastocystis hominis revisited. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 9:563-584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stenzel, D. J., M. F. Cassidy, and P. F. L. Boreham. 1993. Morphology of Blastocystis sp. isolated from circus animals. Int. J. Parasitol. 23:685-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strimmer, K., and A. Von Haeseler. 1996. Quartet puzzling: a quartet maximum likelihood method for reconstructing tree topologies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 13:964-969. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan, K. S. W., M. Singh, and E. H. Yap. 2002. Recent advances in Blastocystis hominis research: hot spots in terra incognita. Int. J. Parasitol. 32:789-804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tasova, Y., B. Sahin, S. Koltas, and S. Paydas. 2000. Clinical significance and frequency of Blastocystis hominis in Turkish patients with haematological malignancy. Acta Med. Okayama 54:133-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teow, W. L., V. Zaman, G. C. Ng, Y. C. Chan, E. H. Yap, J. Howe, P. Gopalakrishnakone, and M. Singh. 1991. A Blastocystis species from the sea-snake, Lapemis hardwickii (Serpentes; Hydrophiidae). Int. J. Parasitol. 21:723-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teow, W. L., G. C. Ng, P. P. Chan, Y. C. Chan, E. H. Yap, V. Zaman, and M. Singh. 1992. A survey of Blastocystis in reptiles. Parasitol. Res. 78:453-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thathaisong, U., J. Worapong, M. Mungthin, P. Tan-Ariya, K. Viputtigul, A. Sudatis, A. Noonai, and S. Leelayoova. 2003. Blastocystis isolates from a pig and a horse are closely related to Blastocystis hominis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:967-975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valkiunas, G., and R. W. Ashford. 2002. Natural host range is not a valid taxonomic character. Trends Parasitol. 18:528-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Windsor, J. J., L. MacFarlane, G. Hughes-Thapa, S. K. A. Jones, and T. M. Whiteside. 2002. Incidence of Blastocystis hominis in faecal samples submitted for routine microbiological analysis. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 59:154-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoshikawa, H., I. Nagono, E. H. Yap, M. Singh, and Y. Takahashi. 1996. DNA polymorphism revealed by arbitrary primers polymerase chain reaction among Blastocystis strains isolated from humans, a chicken, and a reptile. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 43:127-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshikawa, H., I. Nagano, Z. Wu, E. H. Yap, M. Singh, and Y. Takahashi. 1998. Genomic polymorphism among Blastocystis hominis strains and development of subtype-specific diagnostic primers. Mol. Cell Probes. 12:153-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshikawa, H., N. Abe, M. Iwasawa, S. Kitano, I. Nagano, Z. Wu, and Y. Takahashi. 2000. Genomic analysis of Blastocystis hominis strains isolated from two long-term health care facilities. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1324-1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoshikawa, H., Z. Wu, I. Nagano, and Y. Takahashi. 2003. Molecular comparative studies among Blastocystis isolates obtained from humans and animals. J. Parasitol. 89:585-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoshikawa, H., Z. Wu, I. Kimata, M. Iseki, I. K. M. D. Ali, M. B. Hossain, V. Zaman, R. Haque, and Y. Takahashi. 2004. Polymerase chain reaction-based genotype classification among human Blastocystis hominis populations isolated from different countries. Parasitol. Res. 92:22-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]