Abstract

Objective

P2X7 receptor (P2X7R) is a key regulatory element in the neuroinflammatory cascade that provides a promising target for imaging neuroinflammation. GSK1482160, a P2X7 receptor modulator with nanomolar binding affinity and high selectivity, has been successfully radiolabeled and utilized for imaging P2X7 levels in a mouse model of LPS-induced systemic inflammation. In the current study, we further characterized its binding profile and determined whether [11C]GSK1482160 PET can detect changes in P2X7 expression in a rodent model of multiple sclerosis.

Methods

[11C]GSK1482160 was synthesized with high specific activity and high radiochemical purity. Radioligand saturation and competition binding assays were performed for [11C]GSK1482160 using HEK293-hP2X7R living cells. MicroPET studies were performed in nonhuman primates (NHPs). In vitro autoradiography and immunohistochemistry studies then were done to evaluate tracer uptake and P2X7 expression in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) rat lumbar spinal cord at EAE-peak and EAE-remitting stages compared to sham rats.

Results

[11C]GSK1482160 binds to HEK293-hP2X7R living cells with high binding affinity (Kd = 5.09 ± 0.98 nM, Ki = 2.63 ± 0.6 nM). MicroPET studies showed high tracer retention and a homogeneous distribution in the brain of nonhuman primates. In the EAE rat model, tracer uptake of [11C]GSK1482160 in rat lumbar spinal cord was highest at EAE-peak stage (277.74 ± 79.74 PSL/mm2), followed by EAE-remitting stage(149.00 ± 54.14 PSL/mm2) and sham (66.37 ± 1.48 PSL/mm2). The tracer uptake strongly correlated with P2X7 positive cell counts, activated microglia numbers and disease severity.

Conclusions

We conclude that [11C]GSK1482160 possesses potential for application in monitoring neuroinflammation.

Keywords: Neuroinflammation, P2X7 receptor, PET radioligand, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

1. Introduction

Neuroinflammation is a common characteristic of numerous neurodegenerative diseases, including multiple sclerosis (MS) [1]. Substantial data indicate that P2X7 receptor (P2X7R) plays a key regulatory role in the inflammasome molecular complex [2]. In normal physiological conditions, P2X7R is a ‘silent receptor’, due to low extracellular ATP concentration and the low affinity of ATP to P2X7R [3]. In contrast, inflammatory conditions significantly increase extracellular ATP concentration with subsequent upregulation of P2X7R. This stimulates post-translational modification and subsequent release of proinflammatory cytokines, which could initiate the neuroinflammatory cascade [3]. P2X7R is highly expressed in activated microglia [4], that could act as a potential target for PET imaging of neuroinflammation and for therapeutic intervention. P2X7R knockout mice displayed suppressed inflammatory response to systemic injection of ATP and lipopolysaccharides (LPS) [5]. Moreover, pharmacological blockade of P2X7R produces an anti-neuroinflammatory effect in animal models of seizure [6], spinal cord injury [7], subarachnoid hemorrhage [8], Alzheimer disease [9], and multiple sclerosis [10]. Concordantly, a P2X7R-specific PET radioligand would allow in vivo assessment of central nervous system P2X7R expression that are potential useful for monitoring disease severity and therapeutic response to anti-inflammatory drugs.

GSK1482160 is an orally administered allosteric P2X7 receptor modulator with nanomolar binding affinity (Ki = ~3 nM) and high selectivity. Recently, the carbon-11 labeling of [11C]GSK1482160 was reported by Dr. Bennacef’s group [11] and Dr. Zheng’s group [12], and been applied to imaging P2X7 level in a mouse model of LPS-induced systemic inflammation [13]. In the current study, the potential of [11C]GSK1482160 for imaging and monitoring neuroinflammation was further explored. We first characterized the binding profile of [11C]GSK1482160 in HEK293-hP2X7R living cells, and then in the brain of nonhuman primates (NHPs). Furthermore, we used a rodent experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) model of MS to validate the application of [11C]GSK1482160 to detect changes of P2X7 expression and monitoring progression of neuroinflammation.

2. Methods

2.1 Radiochemistry

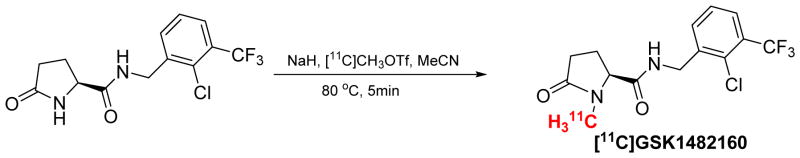

The radiosynthesis of [11C]GSK1482160 was accomplished using a in house building system through N-methylation of the corresponding amide with [11C]CH3OTf shown as Scheme 1. The [11C]CH3I in gas phase which was produced followed the reported method was passed through the quartz tube by which the[11C]CH3I was converted to [11C]CH3OTf [14]. Then [11C]CH3OTf was bubbled into a solution of the reaction mixture in a 5 mL vial (1.0 – 2 mg precursor and 1 mg NaH in 0.2 mL CH3CN). The reaction vial was sealed and heated at 80 °C for 5 minutes. The reaction was quenched by adding 1.7 mL of mobile phase solution. Then the diluted radioactive mixture was injected into a reverse-phase semi-preparative HPLC column (250×9.6 mm, 5 μm) with 2 mL injection loop for purification, using mobile phase of acetonitrile/0.1 M aqueous ammonium formate buffer (35/65, v/v, pH = 4.5), with UV wavelength of 254 nm, a flow rate of 4.0 mL/min. Under these conditions, [11C]GSK1482160 was collected between 13–15 min in a flask of sterile water (50 mL). The diluted aqueous solution was passed through C18 Sep-Pak Plus (WAT020515, Waters, Milford, MA), and washed with water (20 mL). The radioactive product was eluted using EtOH (0.6 mL), followed by 0.9% of saline (5.4 mL). After sterile filtration into a glass dose vial, the product was ready for quality control (QC) analysis and animal study. For the quality control, a aliquot of final dose sample was authenticated with a cold standard solution of compound GSK1482160 using an analytical HPLC system that included a reverse phase Agilent ZORBAX SB-C18 column (4.6×250 mm, 5 μm). Using the mobile phase of 47% acetonitrile in 0.1 M ammonium formate buffer (pH = 4.5); flow rate 1.0 mL/min; UV wavelength 254 nm, the retention time of radiotracer [11C]GSK1482160 is ~5.1 min.

Scheme 1.

Radiosynthesis of [11C]GSK1482160.

2.2 Radioligand binding assay

2.2.1 HEK293-hP2X7R cell culture

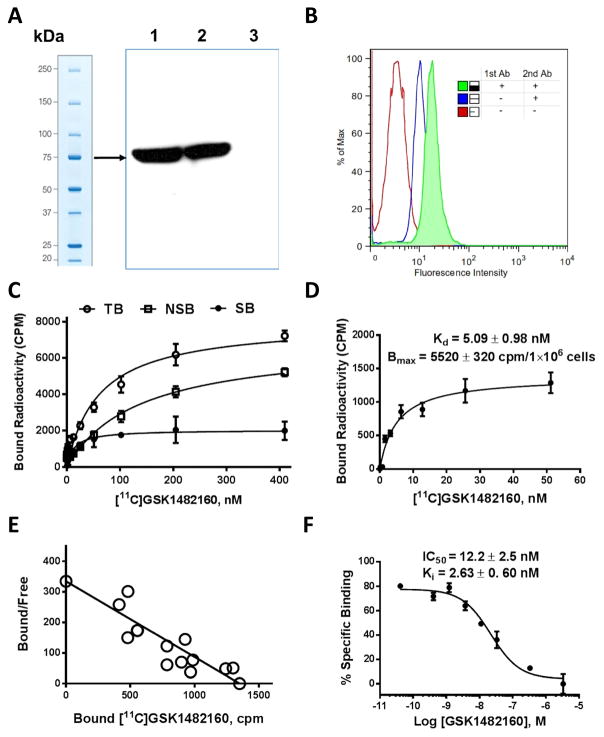

Human embryonic kidney 293 cells stably transfected with the human P2X7 receptor (HEK293-hP2X7R) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, antibiotics (50 U/mL penicillin and 50 μg/mL streptomycin) and 800 μg/mL Geneticin (Invitrogen Inc., Carlsbad, CA). Cells were grown in 75 mL cell culture flask in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Confluent HEK293-hP2X7R cells were washed twice with PBS, then Western blots assessed protein level and FACS confirmed expression of P2X7 receptor (Fig. 1A&B) following published protocols [15,16].

Fig. 1.

Characterization of [11C]GSK1482160 binding to HEK293-hP2X7R cells expressing recombinant human P2X7 receptors. A, Western blot confirmation of the expression human P2X7 receptor in the HEK-293 cell line. Only the HEK-293 cell lysate transfected human P2X7 receptor (lane #1 and #2 are two representative samples, land 3 is the parental HEK-293 without transfection) showed 75 kDa strong bands in lane 1 and 2 indicated the expression of human P2X7 receptor in these cells; B, Florescence Activated Cell sorting (FACS) experiments confirmed the expression human P2X7 receptor on HEK293-hP2X7R cells. Cells stained with both primary antibody and secondary antibodies (green, mean FI~30) show significant left shift compared to cells stained only with secondary antibody (blue, mean FI ~10), or cells stained with neither primary nor secondary antibody (red, mean FI ~2) indicated the expression of human P2X7 receptor on these cells; C, Total bound counts (TB, open circles), nonspecific bound counts (NTB, open squares), and specific bound counts (SB, filled circles) were calculated by subtracting nonspecific from total bound are shown for 12 different radioligand concentrations (between 0.2 nM and 400 nM) after 60 min incubation at 4°C; D, Specific binding saturation curve in the range of 0.2 – 60 nM. The curve fitted binding dissociation constant (Kd) is 5.09 ± 0.98 nM (n = 3), and Bmax is 5520 cpm/1X106 cells (n = 3); E, The specific binding data is fitted a straight line in Scatchard plot; F, Competition binding curve for the cold GSK1482160 with fixed tracer [11C]GSK1482160 concentration. The curve fitted binding IC50 is 12.2 ± 2.5 nM (n = 2), and Ki is 2.63 ± 0.60 nM (n= 2).

2.2.2 Radioligand saturation binding assay

For saturation binding measures, 2.5 ×105 human HEK293-hP2X7R cells per well were placed in 96-well poly-lysine coated microplate (Bioworld Inc., Dublin, OH) overnight. Culture medium was removed on the second day, and cells were washed three times with 250 μL/well ice-cold assay buffer which was 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4 with 0.1% BSA. Then 90 μL/well of assay buffer with serial diluted [11C]GSK1482160, and 10 μL of assay buffer only (for total binding) or 10 μL of assay buffer with 100 μM final concentration of cold GSK1482160 were added (for nonspecific binding). The final concentration of [11C]GSK1482160 was in the range of 0.2 – 400 nM, calculated based on the radioactivity concentration and the specific activity. Triplicate wells were made for each concentration in the assay. Wells were incubated for 1 hr on ice in a shaking water bath. Binding activities were terminated by rapid washing of the plate 5 times with 200 μL/well of ice-cold assay buffer. After the last wash, 150 μL/well of 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) was added. After 1–2 min clean cell lysate from the 96-well microplate were transferred to a scintillation vial, and 2 mL of Bio-Safe II complete counting cocktail (RPI research products Inc., Mount Prospect, IL) were added to each sample. Samples were counted on a Wallac 1450 MicroBeta TriLux liquid scintillation counter (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA). Each sample was counted 30 sec at the energy window of 5–1024 kev, and radioactivity of all samples (cpm) were decay corrected (half-life of 20.3 min) to the point when the specific activity of [11C]GSK1482160 was determined. Normally a total of ~ 56 MBq of [11C]GSK1482160 was needed to obtain reasonable counting statistics and the entire experiment, including washing the plate, transferring samples, and counting samples, was completed in less than 1 hr. Data analysis was accomplished using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc.,San Diego, CA). The specifically bound counts (cpm) from the saturation binding experiments were calculated based on the total binding subtraction of the non-specific binding, and then concentration–effect data were curve-fit to a one-site binding (hyperbola) equation to derive the dissociation constant of the radioligand (Kd) and number of binding sites (Bmax, cpm/1×106 cells).

2.2.3 Radioligand competition binding assay

In radioligand competition binding studies, 2.5 ×105 HEK293-hP2X7R cells/well were placed in 96-well poly-lysine coated microplate overnight. Culture medium was removed on the second day, and cells were washed three times with 250 μL/well ice-cold assay buffer. Then 80 μL/well of assay buffer, 10 μL of assay buffer with serial diluted cold GSK1482160 (final concentration in the range of 0.1 nM – 3 μM), and 10 μL of assay buffer with fixed concentration of [11C]GSK1482160 (final 41 nM based on decay corrected radioactivity concentration and specific activity) were added. Duplicate wells were made for each concentration in the assay. The rest of the procedure was as same as the saturation binding. The specific binding (cpm) was expressed as a percentage of the maximal binding observed in the absence of test compound, and then the concentration–effect data were curve-fit to a 3-parameter inhibitor-effect equation to derive the potency (IC50) of the test compound. The equilibrium dissociation constant (Ki) of the test compound was calculated by the Cheng–Prusoff equation:

Where L* is the [11C]GSK1482160 concentration used and Kd was set to the mean value from saturation assays.

2.3 MicroPET study of [11C]GSK1482160 in cynomolgus macaque

Two male macaques (~ 9.5 kg) were studied with a microPET Focus 220 scanner (Concorde/CTI/Siemens Microsystems, Knoxville, TN). The welfare of the animals conformed to the requirements of National Institutes of Health (NIH). This work was conducted at the Nonhuman Primate Facility of Washington University in St. Louis with approval from its Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Animals were maintained in facilities with 12-hour dark and light cycles, given access to food and water ad libitum and provided a variety of psychologically enriching tasks to prevent inappropriate deprivation. Animals were scanned under anesthesia (induced with ketamine and glycopyrrolate and maintained with inhalation isoflurane) [17–19]. Core temperature was kept about 37 °C with a heated water blanket. The head was secured in a head holder with the brain in the center of the field of view. Subsequently, a 2 hr dynamic emission scan was acquired after administration of 410 MBq of [11C]GSK1482160 via the venous catheter.

PET scans were collected from 0 – 120 min with the following time frames: 3×1 min, 4×2 min, 3×3 min and 20×5 min. Emission data were corrected for dead time, scatter and attenuation and then reconstructed to a final resolution of 2.0 mm full width half maximum in all 3 dimensions at the center of the field of view. PET and MRI images were co-registered using automated image registration program (AIR) [20]. For quantitative analyses, three-dimensional ROI (the global brain) was identified on the MRI, and transformed to the reconstructed PET images to obtain time-activity curves. Activity measures were standardized to body weight and dose of radioactivity injected to yield standardized uptake value (SUV).

2.4 Induction of EAE in female Lewis rats and tissue preparation

All rodent experiments also were conducted in compliance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Research Animals under protocols approved by Washington University’s Animal Studies Committee. The EAE rat model was induced according to our published procedure [21]. In brief, female Lewis rats (Charles River Laboratories, Inc., Wilmington, MA), weighing 100–125 g, were randomly divided into 3 groups; sham group (n = 6), EAE-P (peak) group (n = 7) referring to 12–14 days post immunization corresponding to the highest disability score (4.0 – 5.0) in the acute phase of the disease and the EAE-R (auto-remitting) group (n = 4) which was about 4 weeks after immunization when the symptoms had disappeared completely (score 0). Before each immunization, a myelin basic protein (MBP) emulsion was freshly prepared using a MBP fragment (MBP68-86, AnaSpec Inc., San Jose, CA). Emulsification was performed by mixing an MBP68-86 solution (0.5 mg/mL in phosphate buffered saline, PBS) with an equal volume of complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA), containing 1 mg/mL heat-inactivated Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI). Similarly, a control emulsion was freshly prepared by emulsifying equal volumes of PBS and CFA containing 1 mg/mL heat-inactivated M. tuberculosis. Immunization of rats was performed under anesthesia (2–3% isoflurane in O2) by injecting 200 μL of emulsion, divided equally between the hind footpads. Control rats were injected with an identical volume of a PBS/CFA emulsion.

Subsequent to each immunization, animal weight and neurological deficits were monitored daily. The following scoring system was used to grade neurological impairment: 0, no symptoms; 1, flaccid tail; 2, hindlimb weakness; 3, paraparesis; 3.5, unilateral hindlimb paralysis; 4, bilateral hindlimb paralysis; and 5, bilateral hindlimb paralysis and incontinence. Animals from the three groups were sacrificed separately; the lumbar regions of spinal cords which showed the most severe lesion were used for further tissue processing. Spinal cords were rapidly dissected on ice. Isolated tissues were then dissected and cut in half. One half of the lumbar spinal cord was fixed in 10% formalin and processed for immunohistochemical studies. The other half was snap frozen and cut into 20 μm thick slices for in vitro autoradiographic studies.

2.5 Autoradiography studies of EAE rat spinal cord slices

To assess the difference of tracer uptake in rat spinal cord, 20 μm slices from EAE and sham rats were incubated with 2.8 MBq/mL [11C]GSK1482160 at room temperature for 30 min, following by a 15-min pre-incubation in 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.4). Following this incubation, sections were washed 2 times in assay buffer at 4 °C and rinsed once in distilled water at 4 °C to remove buffer salts. Then the slides were air-dried and exposed to the storage phosphor screen in an imaging cassette for 2 – 4 hrs in −20° C at dark. The distribution of radioactivity was visualized by a Fuji Bio-Imaging Analyzer FLA-7000 (Fuji Photo Film, Tokyo, Japan). Photo-stimulated luminescence was quantified using Multi Gauge v3.0 software (Fuji Photo Film, Tokyo, Japan). Data were background-corrected and expressed as photo-stimulated luminescence signals per square millimeter (PSL/mm2).

2.6 Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of EAE rat spinal cord slices

To investigate the change of P2X7R expression and microglia activation during the EAE progression, 5 μm thick fixed slices from rat lumbar spinal cords were used for IHC studies. Slides were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through a graded alcohol series. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with 3% H2O2 in methanol for 10 min, following antigen retrieval. After blocking in room temperature for 1 hr, slides were incubated with the primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. The primary antibodies used for this study included a rabbit anti-rat P2X7R antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), that was diluted (1:400 ratio) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and a mouse anti-rat Iba-1 antibody (Millipore, Billerica, MA) that was diluted (1:300 ratio) in PBS. Slides were then washed in PBS and was detected using an anti–rabbit or anti-mouse HRP-DAB staining kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Negative controls were carried out without adding the primary antibody. A Nikon E600 microscope coupled with a charge-coupled device camera was used to obtain all photomicrographs.

Images were captured via ACT-1 software (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Eight representative pictures in white matter and six in grey matter (as shown in Fig.S1) were taken from rat lumbar spinal cord traverse sections with 20 × NIKON objective. Image J 1.49V (NIH, Bethesda, MD; https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) was used for primary image processing and immunofluorescence color merge. For quantifications, total positive number of cells was counted by Image J for P2X7R and Iba-1, and the positive cell density (cells/100 μm2) was used for comparison. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). For statistical comparison, the unpaired one-way ANOVA and post hoc tests Bonferroni multiple-comparison test were applied using Prism 6.01 (GraphPad Prism Software, La Jolla, CA) and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1 Radiochemistry

[11C]GSK1482160 was obtained in high specific activity 260 – 360 GBq/μmol (decay corrected to end of bombardment, EOB), with radiochemical yield 30 – 40% (EOB) and radiochemical purity > 99% (n > 10).

3.2 Radioligand binding assay

[11C]GSK1482160 binds to the recombinant human P2X7 receptor with high affinity. As shown in Fig 1, the measured Kd was 5.09 ± 0.98 nM based on the saturation binding studies. The saturation binding data indicated that specific binding represented approximately 40% of total binding. The cell competition assay revealed that the IC50 is 12.2 ± 2.5 nM, and the calculated Ki value was 2.63 ± 0.6 nM. These results are consistent with previous fluorescence screening assay and radioligand assay from other colleagues [13,22]. The specific binding data fit a straight line in Scatchard plot suggesting that one-site binding model is a good model for [11C]GSK1482160 binding to human P2X7 receptor.

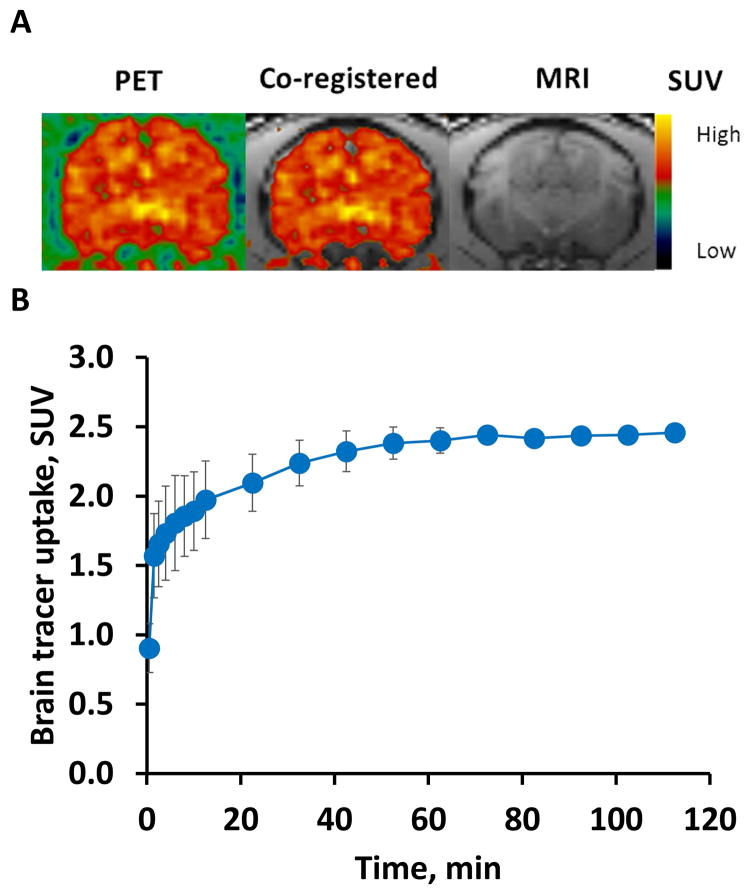

3.3 In vivo uptake of [11C]GSK1482160 in the brain of cynomolgus macaque

To confirm the tracer could penetrate the blood brain barrier of NHP, microPET scans with [11C]GSK1482160 were performed in macaques. The PET images showed [11C]GSK1482160 crossed the blood brain barrier and displayed a homogeneous distribution of [11C]GSK1482160 throughout the NHP brain (Fig. 2A). The SUV curves revealed that the tracer uptake in the total brain reached the max SUV value (~2.45) at ~70 min post injection and remained stable till the end of the 2-hr scan, shown in Fig. 2B. In addition, variation of SUV values between two animals (standard deviation) was small, indicating good reproducibility of PET measures using [11C]GSK1482160.

Fig. 2.

PET imaging of [11C]GSK1482160 in the NHP brain. The microPET study was performed on an adult male cynomolgus monkey (~8.0 Kg) with a microPET Focus 220 scanner. A 2 hr dynamic emission scan was acquired after administration of 410 MBq of [11C]GSK1482160. A, Representative summed PET/MRI images (0–2hrs) indicating high tracer uptake in NHP brain; B, SUV curves of brain regions showing homogeneous distribution of [11C]GSK1482160 throughout the NHP brain.

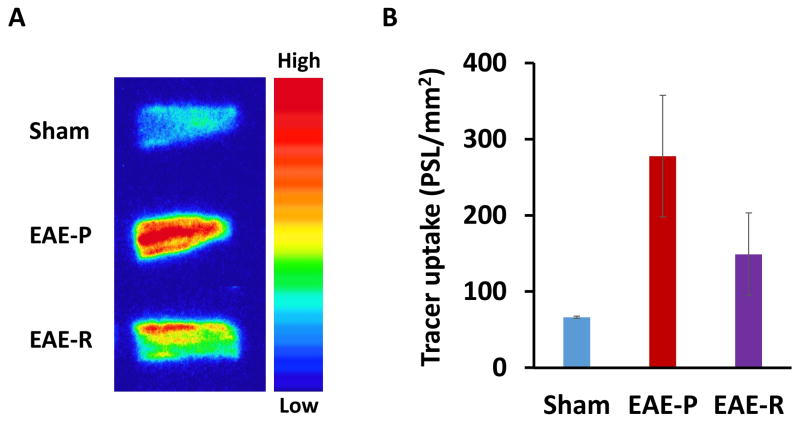

3.4 In vitro autoradiography of [11C]GSK1482160 in EAE rat lumbar spinal cord

To validate the application of [11C]GSK1482160 in detecting and monitoring the change of P2X7R levels in neuroinflammatory conditions, in vitro autoradiographic studies were performed using a rodent EAE model. EAE-peak (EAE-P) rats, which were in the acute phase of the disease (12–14 days post immunization), had most severe symptoms (score 4.0–5.0) and neuroinflammation. EAE-Remitting (EAE-R) rats, which were in the auto-recovery stage (~4 weeks post immunization), showed no obvious symptoms (score 0). Autoradiographic study demonstrated more than 4-fold higher tracer uptake in EAE-P rat lumbar spinal cord than sham (277.74 ± 79.74 PSL/mm2 vs. 66.37 ± 1.48 PSL/mm2, n = 2–3, Fig. 3). The tracer uptake in EAE-R tissues was decreased by half (149.00 ± 54.14 PSL/mm2, n =3, Fig. 3) compared to EAE-P, but still about 2-fold higher than sham. The ratio of EAE-P : EAE-R : Sham = 4.18 : 2.25 : 1.

Fig. 3.

In vitro autoradiography of [11C]GSK1482160 in rat lumbar spinal cord. The 20 μm lumbar spinal cord slices from EAE-P, EAE-R and sham rats, were incubated with 2.8 MBq/mL [11C]GSK1482160 at room temperature for 30 min. A, Representative autoradiography images showing higher tracer uptake in EAE-P and EAE-R rats than sham; B, Quantitative histogram of autoradiography (n = 2 – 3). PSL/mm2, photo-stimulated luminescence signals per square millimeter. EAE-P: EAE rats at peak stage; EAE-R: EAE rats at remitting stage.

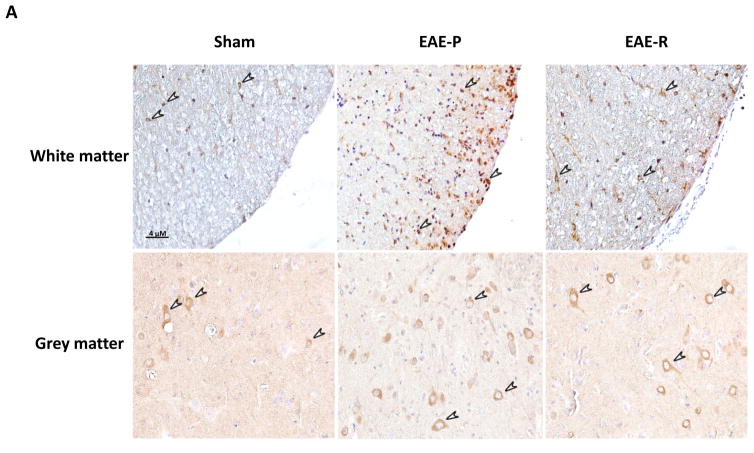

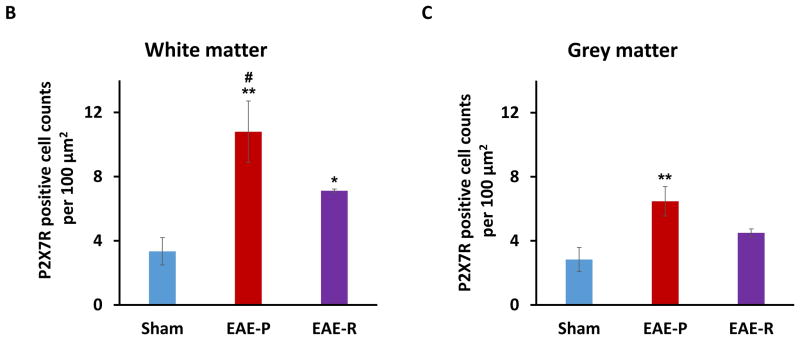

3.5 P2X7R expression in EAE rat lumbar spinal cord

To further confirm the expression of P2X7R protein in rat spinal cord during EAE progression, immunohistochemical staining was performed. P2X7R positive cells were observed in lumbar spinal cord from all three groups (Fig. 4A). The number of P2X7R positive cells increased significantly at the both EAE-P and EAE-R groups, especially higher at EAE-P group, compared to sham (Fig. 4B&C). In white matter, P2X7R positive cells in the EAE-P group (n = 7) were 10.80 ± 1.91/100 μm2, which was 3 times higher than the sham group (3.34 ± 0.85/100 μm2, n = 6, P < 0.01). The numbers in the EAE-R group (n = 4) restored to 7.12 ± 0.10/100 μm2 (Fig. 4A&B), which were lower than the EAE-P group (P < 0.05), but still higher than the sham group (P < 0.05). The ratio of EAE-P: EAE-R: Sham in white matter = 3.02 : 2.13 : 1. A similar trend was found in grey matter. The number of P2X7R positive cells in grey matter of the EAE-P group was 6.47 ± 0.92/100 μm2, which was 2 times higher than the sham group (2.84 ± 0.75/100 μm2, P < 0.01) and higher than the EAE-R group (4.50 ± 0.24/100μm2, Fig. 4A&C). The ratio of EAE-P: EAE-R : Sham in grey matter = 2.28 : 1.58 : 1.

Fig. 4.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of P2X7R in rat lumbar spinal cord. A, Representative IHC images demonstrating an increased number of P2X7R positive cells (brown, indicated by arrows) in lumbar spinal cord of EAE-P and EAE-R groups, compare to sham; B&C, Quantification of P2X7 positive cell counts in white matter and grey matter of rat lumbar spinal cord. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, v.s. sham; #P < 0.05, v.s. EAE-R.

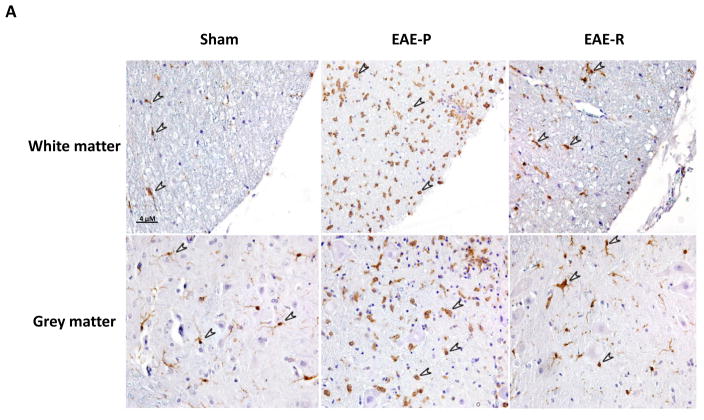

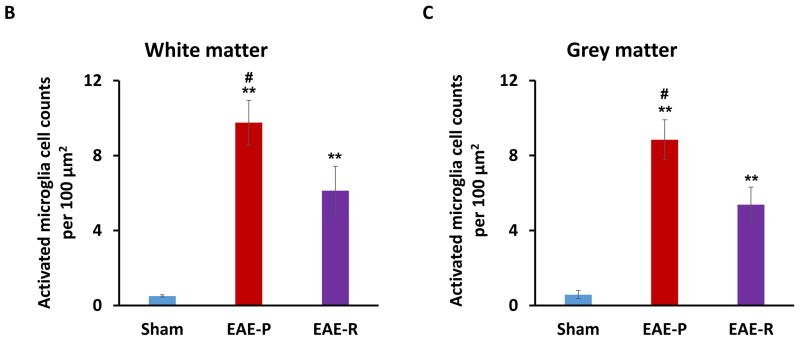

3.6 Microglial activation in EAE rat lumbar spinal cord

To explore microglial activation in EAE rat spinal cord, immunohistochemical staining with a specific antibody for microglia/macrophage (anti-Iba-1 antibody) were applied. Iba-1 positive cells were detected throughout white and grey matter in lumbar spinal cord of all three groups (Fig. 5A). While a few Iba-1 positive cells were observed in the sham group, which reflected the baseline level of microglia at rest, the number of Iba-1 positive cells increased significantly in both the EAE-P and the EAE-R group, especially in the EAE-P group (Fig. 5B&C). Similar Iba-1 positive cells distribution trend was found within both white matter and grey matter, which was consistent with previous report [21]. In white matter the number of Iba-1 positive cells reached the maximum (9.76 ± 1.19/100 μm2) in EAE-P group then decline to 6.13 ± 1.30/100μm2 in EAE-R group. Both of them were much higher than the sham group (0.51 ± 0.06/100μm2, P<0.01 for EAE-P vs sham, P < 0.01 for EAE-R vs sham); the positive cells of EAE-P group were also higher than the EAE-R group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5A&B). The Iba-1 positive cells in grey matter showed the similar trend (Fig. 5C). In the sham group the positive cell number were 0.58 ± 0.21/100μm2, and the number reached 8.84 ± 1.07/100 μm2 in the EAE-P group. EAE-R group also was higher (5.38 ± 0.93/100 μm2) than the sham group (P < 0.01), while EAE-P group was higher than the EAE-R group (P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

IHC staining of microglial activation in rat lumbar spinal cord. A, Representative IHC images demonstrating microglial activation in lumbar spinal cord of EAE-P and EAE-R groups, compare to sham; B&C, Quantification of activated microglia counts in white matter and grey matter of rat lumbar spinal cord. Activated microglia was stained in brown color, which were indicated by arrows. **P < 0.01, v.s. sham; #P < 0.05, v.s. EAE-R.

4. Discussion

Advances in molecular imaging of neuroinflammation in the past decade have improved our understanding of neuroinflammatory mechanism in neurodegenerative diseases. Yet current PET imaging of neuroinflammation remains in its infancy. PET radioligands targeting translocator protein 18KDa (TSPO) have been widely used in preclinical and clinical assessment of microglia activation. However, a genetic polymorphism regulates expression of the TSPO protein resulting in dramatic differences of normal binding affinity of TSPO radiotracers in human brain [22]. Thus genetic screening of individual patients must be done to interpret these PET measures. New PET radioligands of neuroinflammation not dependent upon such polymorphism are critically needed for human studies.

P2X7R orchestrates neuroinflammation and offers a promising target for radioligand development for neuroinflammation. To date, only a few P2X7R radioligands have been reported in preclinical studies, including [11C]A-740003 and [11C]JNJ54173717. [11C]A-740003 showed little brain uptake in rats, precluding its further application in CNS diseases [23]. Radiotracer [11C]JNJ54173717 has been evaluated in a rat model expressing human P2X7 receptors and healthy nonhuman primates for in vivo visualization of P2X7 receptors in the brain [24]. [11C]JNJ54173717 has high brain uptake in the first hr post tracer injection, suggesting the suitability as a PET radiotracer to reflect P2X7 receptor expression. However, radioactivity concentration of [11C]JNJ54173717 continued to increase in the NHP brain after 75 min post tracer injection, which may reflect accumulation of radioactive metabolites [24].

In this study we characterized in vitro in cell membrane preparations and in vivo behavior of [11C]GSK1482160 with nonhuman primate PET. The inital characterization of [11C]GSK1482160 in HEK293-hP2X7R cell membrane preparation and LPS-treated mouse model of inflammation has been recently reported by Territo PR and co-workers, showing that [11C]GSK1482160 has high binding potency for human P2X7 receptor and the tracer uptake increased by 3.6-fold in mouse brain 72 hrs after LPS i.p. injection [13]. In agreement, our direct saturation binding measure of [11C]GSK1482160 itself using HEK293-hP2X7R living cells resulted in similar Kd value. Furthermore, we also performed radioligand competition binding assay with living cells. The resulting Ki value was 2.63 ± 0.60 nM, and was close to the repreviously reported Ki value obtained by a fluorescence-based ethidium bromide accumualtion assay [25].

Based on the promising in vitro binding results, we performed the microPET studies of [11C]GSK1482160 in the brain of healthy NHPs. MicroPET images of NHP brain confirmed that [11C]GSK1482160 has good blood brain barrier penetration, as well as homogeneous distribution in NHP brain. Our finding is consistent with previous reports which also indicated widespread distribution of P2X7 in rodent and NHP brains [13,24,26], although one autoradiography study using [3H]-A-804598 showed heterogeneity of binding site intensity in rat brain [27]. In addition, the homogeneous distribution of [11C]GSK1482160 in the brain would not impact its application in detecting the increase of P2X7 expression under neuroinflammatory conditions, especially those with focal inflammatory lesions such as trauma and infection. Compared with the in vivo kinetics of [11C]JNJ54173717, which reaches the peak fast and then washes out quickly from the brain [4], [11C]GSK1482160 has a relatively high retention in the brain over the 2 hr PET scan period. Previous study suggested [11C]GSK1482160 is metabolically stable and metabolite correction will have minimal impact on kinetics [2]. Therefore, the high brain retention of [11C]GSK1482160 could permit stable and reproducible PET measures at relatively late time point post tracer injection. Also the relatively slow washout kinetics of [11C]GSK1482160 may provide better imaging for static scan acquisition.

Encouraged by both in vitro pharmacologic characterization of [11C]GSK1482160 and microPET study in the brain of nonhuman primates, we measured the change of P2X7R expression in reponse to neuroinflammation. Neuroinflammation plays a key role in the demyelinating pathogenesis of MS. The rat EAE model of MS includes acute severe neuroinflammation in lumbar spinal cord, with modest demylination, and has been used in our lab for evaluation of radioligands targeting neuroinflammation [21]. Noteably, [11C]GSK1482160 showed 100 times lower binding affinity for the rodent P2X7 receptor versus the human P2X7 receptor (316 nM v.s. 3.16 nM) [28]. As a result, microPET imaging of [11C]GSK1482160 in rat spinal cord demostrated about 14% increase in tracer uptake (in terms of SUV) in EAE rat compared with sham rats (Fig. S2). However, the relatively low tracer uptake in the rat spinal cord that may coused by low binding affinity (~316 nM) of [11C]GSK1482160 to rodent tissues resulted in a poor image resolution, thus tempered further investigation of microPET studies in this EAE rat model. Therefore, we used in vitro autoradiography to assess the change of P2X7 expression in rat lumbar spinal cord during the course of this EAE rodent model.

In vitro autoradiography using [11C]GSK1482160 revealed a strong correlation between tracer uptake and disease progression. EAE-P rat tissues possess the highest tracer accumulation, followed by tissues from the EAE-R group and the sham rats. This rank order matched the EAE score across these three groups. The tracer concentration used in the autoradiographic study (~400 nM) was relatively high, and was close to the reported binding affinity of GSK1482160 in rat P2X7 receptors (316 nM) [25]. We directly examined P2X7R expression and the related inflammatory response in EAE rat lumbar spinal cord. The elevated expression of P2X7R in EAE rat brains was previously reported [29], but the correlation of P2X7R expression and microglial activation remains obscure. In MS patients and EAE rodent models, microglia exhibit uncontrolled activation and produce pro-inflammatory mediators to recruit inflammatory cells such as T cells [30,31]. Moreover, it can also directly release a variety of cytotoxic substances and cause cellular damage, including IL-1β [32]. P2X7 receptor plays a vital role in microglia-madiated IL-1 β processing and release through the membrane receptors, which promotes inflammatory damage in CNS [33–37]. We detected enhanced P2X7R expression and microglia activation in EAE-P rat tissues. The P2X7R level in EAE spinal cord also remained upregulated during the remitting stage, which agreed with the autoradiographic findings. Our autoradiographic and immunohistological data revealed that the tracer uptake of [11C]GSK1482160 in EAE rat lumbar spinal cord correlated with P2X7R protein level, microglial activation, and disease severity.

5. Conclusion

[11C]GSK1482160 has a high binding affinity to hP2X7R, crosses the blood brain barrier and homogeneously distributes in the NHP brain. In vitro autoradiography with [11C]GSK1482160 successfully monitored the change of P2X7R expression in lumbar spinal cord in a EAE rat model; the tracer uptake was strongly correlated with both microglia activation and disease severity. Therefore, NHP models of neuroinflamation are warranted to test the feasibility of microPET with [11C]GSK1482160 in imaging and monitoring neuroinflammation. Considering the higher binding potency of in human brain tissues, [11C]GSK1482160 has high potential for assessing neuroinflammatory responses in MS patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding resource: This work was supported by DOE-Training in Techniques and Translation: Novel Nuclear Medicine Imaging Agents for Oncology and Neurology, DESC0008432, and Interdisciplinary Training in Translational Radiopharmaceutical Development and Nuclear Medicine Research for Oncologic, Neurologic, and Cardiovascular Imaging, DESC0012737, NIH grants NS058714 and NS41509, American Parkinson Disease Association (APDA) Center for Advanced PD Research at Washington University; Greater St. Louis Chapter of the APDA; McDonnell Center for Higher Brain Function; Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation (Elliot Stein Family Fund for PD Research & the Parkinson disease Research Fund), and NIH/NINDS, NS075527, NIH/NIMH, MH092797.

The authors would like to thank Emily William, Darryl Craig and John Hood for the technique support in microPET studies in macaques, Nicole Fettig, Margaret Morris, Amanda Roth, Lori Strong and Ann Stroncek for their assistance with rat microPET studies, Marlene Scott and Bill Coleman in the Elvie L. Taylor Histology Core Facility of Washington University School of Medicine for sample embedding and cutting.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest concerning this paper can be reported.

References

- 1.Poutiainen P, Jaronen M, Quintana FJ, Brownell AL. Precision Medicine in Multiple Sclerosis: Future of PET Imaging of Inflammation and Reactive Astrocytes. Front Mol Neurosci. 2016;9:85. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2016.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sperlagh B, Illes P. P2X7 receptor: an emerging target in central nervous system diseases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2014;35:537–547. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhattacharya A, Biber K. The microglial ATP-gated ion channel P2X7 as a CNS drug target. Glia. 2016;64:1772–1787. doi: 10.1002/glia.23001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monif M, Reid CA, Powell KL, Smart ML, Williams DA. The P2X7 receptor drives microglial activation and proliferation: a trophic role for P2X7R pore. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3781–3791. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5512-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solle M, Labasi J, Perregaux DG, Stam E, Petrushova N, Koller BH, et al. Altered cytokine production in mice lacking P2X(7) receptors. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:125–132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer W, Franke H, Krugel U, Muller H, Dinkel K, Lord B, et al. Critical Evaluation of P2X7 Receptor Antagonists in Selected Seizure Models. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0156468. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang X, Arcuino G, Takano T, Lin J, Peng WG, Wan P, et al. P2X7 receptor inhibition improves recovery after spinal cord injury. Nat Med. 2004;10:821–827. doi: 10.1038/nm1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen S, Ma Q, Krafft PR, Hu Q, Rolland W, 2nd, Sherchan P, et al. P2X7R/cryopyrin inflammasome axis inhibition reduces neuroinflammation after SAH. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;58:296–307. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parvathenani LK, Tertyshnikova S, Greco CR, Roberts SB, Robertson B, Posmantur R. P2X7 mediates superoxide production in primary microglia and is up-regulated in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13309–13317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209478200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matute C, Torre I, Perez-Cerda F, Perez-Samartin A, Alberdi E, Etxebarria E, et al. P2X(7) receptor blockade prevents ATP excitotoxicity in oligodendrocytes and ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9525–9533. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0579-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo Q, Weinzimmer D, Labaree D, Carson R, Ding Y, Ridler K, et al. Imaging P2X7 receptor using PET. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2011;54:S298. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao M, Wang M, Green MA, Hutchins GD, Zheng QH. Synthesis of [(11)C]GSK1482160 as a new PET agent for targeting P2X(7) receptor. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2015;25:1965–1970. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Territo PR, Meyer JA, Peters JS, Riley AA, McCarthy BP, Gao M, et al. Characterization of [11C]-GSK1482160 for targeting the P2X7 receptor as a biomarker for neuroinflammation. J Nucl Med. 2016 doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.181354. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Padakanti PK, Zhang X, Li J, Parsons SM, Perlmutter JS, Tu Z. Syntheses and radiosyntheses of two carbon-11 labeled potent and selective radioligands for imaging vesicular acetylcholine transporter. Mol Imaging Biol. 2014;16:765–772. doi: 10.1007/s11307-014-0748-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Migita K, Ozaki T, Shimoyama S, Yamada J, Nikaido Y, Furukawa T, et al. HSP90 Regulation of P2X7 Receptor Function Requires an Intact Cytoplasmic C-Terminus. Mol Pharmacol. 2016;90:116–126. doi: 10.1124/mol.115.102988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang XJ, Zheng GG, Ma XT, Yang YH, Li G, Rao Q, et al. Expression of P2X7 in human hematopoietic cell lines and leukemia patients. Leuk Res. 2004;28:1313–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tabbal SD, Mink JW, Antenor JA, Carl JL, Moerlein SM, Perlmutter JS. 1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced acute transient dystonia in monkeys associated with low striatal dopamine. Neuroscience. 2006;141:1281–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin H, Zhang X, Yue X, Liu H, Li J, Yang H, et al. Kinetics modeling and occupancy studies of a novel C-11 PET tracer for VAChT in nonhuman primates. Nucl Med Biol. 2016;43:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin HJ, Yue XY, Zhang X, Li JF, Yang H, Flores H, et al. A promising F-18 labeled PET radiotracer (−)- F-18 VAT for assessing the VAChT in vivo.Society for Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging Annual Conference Baltimore, MD. J Nucl Med. 2015;56(4 supplement 3) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woods RP, Mazziotta JC, Cherry SR. MRI-PET registration with automated algorithm. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1993;17:536–546. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu H, Jin H, Yue X, Luo Z, Liu C, Rosenberg AJ, et al. PET Imaging Study of S1PR1 Expression in a Rat Model of Multiple Sclerosis. Mol Imaging Biol. 2016;18:724–732. doi: 10.1007/s11307-016-0944-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owen DR, Yeo AJ, Gunn RN, Song K, Wadsworth G, Lewis A, et al. An 18-kDa translocator protein (TSPO) polymorphism explains differences in binding affinity of the PET radioligand PBR28. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1–5. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janssen B, Vugts DJ, Funke U, Spaans A, Schuit RC, Kooijman E, et al. Synthesis and initial preclinical evaluation of the P2X7 receptor antagonist [(1)(1)C]A-740003 as a novel tracer of neuroinflammation. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2014;57:509–516. doi: 10.1002/jlcr.3206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ory D, Celen S, Gijsbers R, Van Den Haute C, Postnov A, Koole M, et al. Preclinical Evaluation of a P2X7 Receptor-Selective Radiotracer: PET Studies in a Rat Model with Local Overexpression of the Human P2X7 Receptor and in Nonhuman Primates. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:1436–1441. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.169995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdi MH, Beswick PJ, Billinton A, Chambers LJ, Charlton A, Collins SD, et al. Discovery and structure-activity relationships of a series of pyroglutamic acid amide antagonists of the P2X7 receptor. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:5080–5084. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu Y, Ugawa S, Ueda T, Ishida Y, Inoue K, Nyunt AK, et al. Cellular localization of P2X7 receptor mRNA in the rat brain. Brain Res. 2008;1194:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Able SL, Fish RL, Bye H, Booth L, Logan YR, Nathaniel C, et al. Receptor localization, native tissue binding and ex vivo occupancy for centrally penetrant P2X7 antagonists in the rat. Brit J Pharmacol. 2011;162:405–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01025.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ziff J, Rudolph DA, Stenne B, Koudriakova T, Lord B, Bonaventure P, et al. Substituted 5,6-(Dihydropyrido[3,4-d]pyrimidin-7(8H)-yl)-methanones as P2X7 Antagonists. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2016;7:498–504. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grygorowicz T, Struzynska L, Sulkowski G, Chalimoniuk M, Sulejczak D. Temporal expression of P2X7 purinergic receptor during the course of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Neurochem Int. 2010;57:823–829. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heppner FL, Greter M, Marino D, Falsig J, Raivich G, Hovelmeyer N, et al. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis repressed by microglial paralysis. Nat Med. 2005;11:146–152. doi: 10.1038/nm1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sorensen TL, Tani M, Jensen J, Pierce V, Lucchinetti C, Folcik VA, et al. Expression of specific chemokines and chemokine receptors in the central nervous system of multiple sclerosis patients. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:807–815. doi: 10.1172/JCI5150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prins M, Eriksson C, Wierinckx A, Bol JG, Binnekade R, Tilders FJ, et al. Interleukin-1beta and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist appear in grey matter additionally to white matter lesions during experimental multiple sclerosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferrari D, Pizzirani C, Adinolfi E, Lemoli RM, Curti A, Idzko M, et al. The P2X7 receptor: a key player in IL-1 processing and release. J Immunol. 2006;176:3877–3883. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hewinson J, Moore SF, Glover C, Watts AG, MacKenzie AB. A key role for redox signaling in rapid P2X7 receptor-induced IL-1 beta processing in human monocytes. J Immunol. 2008;180:8410–8420. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.8410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mingam R, De Smedt V, Amedee T, Bluthe RM, Kelley KW, Dantzer R, et al. In vitro and in vivo evidence for a role of the P2X7 receptor in the release of IL-1 beta in the murine brain. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morandini AC, Ramos-Junior ES, Potempa J, Nguyen KA, Oliveira AC, Bellio M, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbriae dampen P2X7-dependent interleukin-1beta secretion. J Innate Immun. 2014;6:831–845. doi: 10.1159/000363338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verhoef PA, Estacion M, Schilling W, Dubyak GR. P2X7 receptor-dependent blebbing and the activation of Rho-effector kinases, caspases, and IL-1 beta release. J Immunol. 2003;170:5728–5738. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.