Abstract

The study objective was to identify facilitators and barriers of parental attitudes and beliefs toward school-located influenza vaccination in the United States. In 2009, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expanded their recommendations for influenza vaccination to include school-aged children. We conducted a systematic review of studies focused on facilitators and barriers of parental attitudes toward school-located influenza vaccination in the United States from 1990 to 2016. We reviewed 11 articles by use of the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework. Facilitators were free/low cost vaccination; having belief in vaccine efficacy, influenza severity, and susceptibility; belief that vaccination is beneficial, important, and a social norm; perception of school setting advantages; trust; and parental presence. Barriers were cost; concerns regarding vaccine safety, efficacy, equipment sterility, and adverse effects; perception of school setting barriers; negative physician advice of contraindications; distrust in vaccines and school-located vaccination programs; and health information privacy concerns. We identified the facilitators and barriers of parental attitudes and beliefs toward school-located influenza vaccination to assist in the evidence-based design and implementation of influenza vaccination programs targeted for children in the United States and to improve influenza vaccination coverage for population-wide health benefits.

Keywords: Influenza, school located vaccination, parental attitudes, parental beliefs, United States

INTRODUCTION

School-based health interventions have been implemented throughout the United States, with most school-based health clinics offering vaccination services to the general school community. In contrast, school-located vaccination (SLV) programs, and specifically school-located influenza vaccination (SLIV), are dedicated programs for targeted vaccination of school-aged children [1,2]. SLV programs have been adopted worldwide in countries such as Canada [3], the United Kingdom [4], and Australia [5]. While less common in the United States, school-located programs for influenza vaccination have shown success statewide in Hawaii [6] and in pilot studies in Tennessee [7] and Maryland communities [8].

Since the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, SLIV programs have gained significant public health interest [1] for improving adolescent vaccination rates in non-clinical settings [9–12], potentially reducing emergency care visits for influenza-like illnesses, lowering community influenza risk, decreasing laboratory-confirmed cases, and improving school attendance [13,14]. In a modeling study by Weycker et al., authors found that vaccinating 20% of children in the United States decreased the total number of influenza cases in the total population by 46%, along with similar decreases in influenza-related mortality and economic costs [15]. However, because SLIV participation ultimately depends on parental consent, there is a need for enhanced understanding of parental attitudes and beliefs regarding SLIV in order to improve influenza vaccination rates among school children in the United States.

Study objective

Our study objective was to identify the facilitators and barriers of parental attitudes and beliefs toward school-located influenza vaccination in the United States, thereby assisting in the evidence-based design and implementation of current and future influenza vaccination programs targeted for children, by leveraging facilitators and addressing potential barriers of parental consent.

Public health significance

In 2009, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expanded recommendations for targeted influenza vaccination by including school-aged children in the United States [16]. While this has improved vaccination coverage among children (6 months – 17 years) from 43.7% during the 2009–2010 influenza season to 59.3% during the 2015–2016 season [17], this is below the target of 70% in the Healthy People 2020 initiative [18].

Despite globally recognized benefits of school-located vaccination, the evidence base for SLIV acceptance in the United States is limited [11,12], with studies focused on clinical aspects of vaccine efficacy [19], program feasibility [20], and population-level benefits [21]. We conducted a systematic review to address this evidence gap to improve influenza vaccination coverage by identifying facilitators and barriers of parental attitudes and beliefs toward school-located influenza vaccination for children in the United States.

METHODS

Search strategy

We conducted our search using PubMed and Web of Science databases for articles written in the English language, published between 01/01/1990 to 10/01/2016, and contained the following the terms: (influenza) AND (vaccine OR vaccination OR immunization) AND (school OR school-located OR school-based) AND (parent OR parental).

Data abstraction and synthesis

The data abstraction and synthesis process were conducted by two authors (GJK and RKC) independently; we resolved discordant decisions through consensus. Data abstraction and synthesis included the following four steps: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion. During the identification step, articles were identified using the aforementioned search strategy. During screening, duplicate articles were removed, and the titles and abstracts of the remaining articles were screened to determine relevance to our study objectives. During the eligibility step, article full text was analyzed to further determine relevance to our study objectives and to be used for inclusion.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included articles that focused on childhood/adolescent age groups to target school-aged children in grades PreK-12 which met the following study criteria: 1) conducted qualitative and/or quantitative analysis regarding influenza vaccination for school-aged children in the United States; and 2) assessed parental factors associated with the acceptance, hesitancy, or refusal of utilizing school-located influenza vaccination for children, including parental knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes. We excluded studies that focused on general vaccine delivery (i.e. non-specific to influenza vaccine), studies of non-explicit parent populations (such as school personnel and health care workers who may also be parents), and studies taking place outside the United States.

PRISMA process

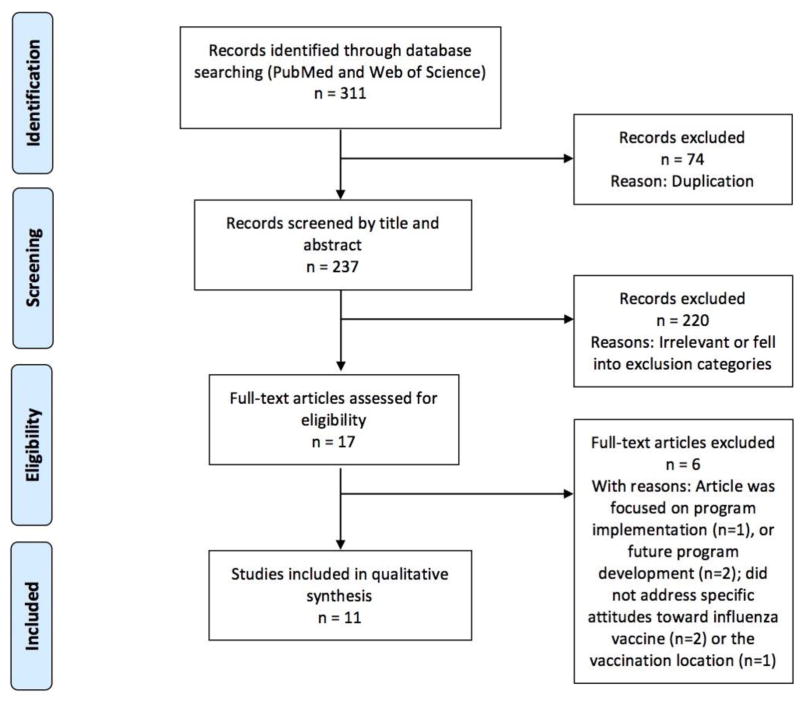

Figure 1 illustrates the process flow diagram of identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion of articles for the systematic review, using the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework [22]. Eleven articles met our selection criteria for systematic review of facilitators and barriers of parental attitudes and beliefs toward school-located influenza vaccination in the United States. While we have included quantitative metrics of the clinical effect size of statistical association for each of the 11 studies, we have excluded quantitative synthesis using meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity in study design and population sampling of these 11 studies.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of articles’ identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion in the systematic review is illustrated. Articles focused on the facilitators and barriers of parental attitudes and belief towards school-located influenza vaccination in the United States were included, while articles focused on non-influenza vaccination, non-parent population, and regions outside of United States were excluded.

RESULTS

Characteristics of school-located influenza vaccination studies

We identified 11 articles focused on school-located influenza vaccination (SLIV) for analysis based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria of our systematic review. Table 1 illustrates the objectives of the 11 studies, SLIV context (hypothetical or actual program context), school settings, geographic area, type of survey and/or focus group, parental sample sizes, and significant inferences regarding parental attitudes and beliefs of SLIV for school-aged children in the United States.

Table 1. Characteristics of school-located influenza vaccination studies.

Contexts, objectives, school settings, geographic area, survey/focus group type, parent sample sizes, health behavior model, effect size of statistical association, significant inferences, and limitations from studies pertaining to parental attitudes and beliefs of school-located influenza vaccination (SLIV) for school-aged children in the United States.

| Study | Context | Objective | School setting and geographic area | Survey/ focus group type and parental sample size | Health behavior model | Effect size of statistical association (AOR - Adjusted odds ratio; RR - Risk ratio; CI - Confidence interval) | Significant inferences | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [9] | Hypothetical SLIV program | To identify parental beliefs, barriers, and acceptance of SLIV | 1 public elementary school (K-6) in Salt Lake City, Utah | Cross-sectional survey of 259 parents (out of 397) | Health Belief Model | 75% of parents, including 59% (76/129) who did not plan to immunize would consent to SLIV if offered for free; facilitators were belief in benefit (AOR: 6.1; 95% CI: 2.7–14.0), endorsement of medical setting barriers (AOR: 3.7; 95% CI: 1.3–10.3), belief that immunization is a social norm (AOR: 3.3; 95% CI: 1.4–7.6), and that the child is susceptible to influenza (AOR: 2.6; 95% CI: 1.2–5.7) | SLIV programs should address barriers of cost and inconvenience, promote immunization as a social norm, and address parental concerns regarding vaccine safety and benefit | Most families were Caucasian or Latino in a single school of a single season, limiting generalizability |

| [11] | Hypothetical SLIV program | To assess the feasibility of SLIV | Nationally representative online sample | Online survey of 1088 parents whose youngest child was ≤ 14 years old | Survey based on literature review of vaccine topics, focus groups, and pretest interviews | 51% of parents would consent to SLIV; SLIV was more convenient than the regular location (42.1% of consenting parents versus 19.9% of non-consenting parents, P < 0.001), however, regular location was preferred over SLIV in case of side effects (46.4% vs. 20.9%, P < 0.001) and for proper administration of the vaccine (31.0% vs. 21.0%, P < 0.001) | SLIV convenience promoted acceptance, but medical location was preferred for proper administration and potential care of side effects; vaccine safety was a significant barrier | Low response rate limited generalizability; responses to hypothetical program do not reflect likelihood of action |

| [7] | SLIV campaign (2 doses LAIV) delivered by county health department | To evaluate the feasibility and success of SLIV | 76 schools (50 elementary, 14 middle, 12 high schools) from 1 large metropolitan public school system (K-12) in Knox County, Tennessee | Brief survey of 1432 parents | Feedback survey regarding SLIV participation | Non-participation in the vaccination campaign was reported by 53% (34/64) parents of black students and 36% (494/1339) parents of non-black students (RR: 1.44; 95% CI: 1.13–1.83) | Barriers to SLIV participation included concerns regarding vaccine adverse effects, influenza acquisition through vaccine, and concerns of vaccine virus transmission to household members with health issues such as asthma | Low response rate limited representativeness |

| [23] | SLIV campaign delivered by county public health department in 8 schools in year 1 and continued in 4 schools in year 2 | To determine predictors of consent based on parental attitudes for SLIV | 8 urban elementary schools (PreK-6, ages 5–13) in 2 school districts, Los Angeles County, California | Survey of 1259 parents (Year 1); 1496 parents (Year 2) | Health Belief Model | During 2009 influenza pandemic, parents concerned about influenza severity were twice as likely to consent for influenza vaccination compared to unconcerned parents (OR: 2.04; 95% CI: 1.19–3.51). During year 2, facilitators of parental consent were perception of high susceptibility to influenza (OR: 2.19, 95% CI: 1.50–3.19) and high vaccine benefit (OR: 2.23, 95% CI: 1.47–3.40) | Parents with better understanding of influenza risks and influenza vaccine benefits were more likely to consent for SLIV | Low response rates suggest selection bias; higher consent rates of survey respondents (compared to school enrollees) skews responses; respondents were from low-income, mostly Hispanic (followed by Asian) population, limiting generalizability |

| [24] | Hypothetical program for adolescent vaccines in general; SLV for influenza had been previously available | To determine parental attitudes and acceptance of school-located vaccination of middle- and high school students for four adolescent recommended vaccines, including influenza vaccine | 6 middle- and 5 high schools; urban, Richmond County, Georgia | Telephone & web survey of 686 parents for 3 years | Health Belief Model; Theory of Reasoned Action | Facilitators of SLIV were higher parental perception of benefits to vaccination (AOR = 1.3; 95% CI 1.1–1.5) and increased social norms (AOR = 1.44; 95% CI 1.12–1.84) | SLIV acceptance by parents correlated with beliefs of influenza vaccination being a social norm and perception of illness severity prevented by vaccination in general | Low response rate; potential duplication of responses; single county population, predominantly black, low-income; generalizability is limited |

| [27] | Study takes place 2+ years after implementation of a 3-year, multi-component influenza vaccination program delivered by a research group | To characterize the decision-making process and reasons of parents and students for participation in SLIV | Middle and high school; rural county in Georgia | Focus group discussions of 41 parents (and 44 students) | Focus groups, open discussion on attitudes toward SLIV | Not applicable - no quantitative/statistical analysis | Barriers of non-participating parents of SLIV involved distrust, suspicions of vaccination clinic, and the lengthy consent process | Purposive sampling of respondents from rural Georgia, predominantly black and low-income limits generalizability; focus groups were conducted over 2 years after program implementation, suggesting recall bias; no demographic or socioeconomic data collected |

| [25] | Hypothetical SLIV program | To examine parental attitudes toward adolescent vaccination in school settings, including influenza vaccine | 3 urban/suburban middle schools (grade 6) in Aurora, Colorado | Cross-sectional mailed survey of 500 (out of 806) parents | Survey based on medical literature | 81% of parents agreed that SLIV would be safe and convenient, however, 47% preferred another vaccination site | Belief in vaccine importance was associated with SLIV acceptance by parents; major barrier was parental absence during vaccination | No collection of income data; possible sampling bias; responses to hypothetical program do not reflect likelihood of action |

| [26] | 2 SLIV campaigns per school delivered by city public health department and community health services | To assess parental attitudes and supportive factors for SLIV of elementary school students | 20 public elementary schools (K-6), low SES; Denver, Colorado | Survey of 699 parents | Health Belief Model | Facilitators were belief in vaccine efficacy (RR: 1.49; 95% CI: 1.23–1.84) and convenience of school delivery (RR: 2.37; 95% CI: 1.82–3.45). Barriers were safety concerns of influenza vaccine (RR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.72–0.88) and not wanting their child vaccinated without a parent (RR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.64–0.83) | SLIV was strongly supported by parents with belief in vaccine efficacy and convenience of school setting; barriers involved concerns about vaccine safety and parental absence during vaccination | Low-income, urban population of mostly ethnic minorities limits generalizability; survey conducted during same year as 2009 H1N1 pandemic |

| [28] | Hypothetical SLIV program | To determine factors influencing parental consent of SLIV | 1 elementary, 2 middle, 3 high schools in large urban school district in Houston, Texas | 37 parents; 5 focus group interviews | Questions were based on medical literature | Not applicable - no quantitative/statistical analysis | Parental attitudes to SLIV are impacted by safety and trust issues regarding vaccines in general; programs should effectively communicate information of competency of health personnel administering the vaccine and of equipment sterility | Selection bias of highly educated parents limits generalizability |

| [12] | Hypothetical SLIV program | To describe parent and student perspectives for participation in SLIV | 3 middle and 3 high schools in large, urban school district; Houston independent school district | Survey of 566 parent-student dyads | Survey based on focus groups | Not applicable - no quantitative/statistical analysis | SLIV participation by parents is impacted by equipment sterility, universal access of vaccines for all students, and cost | 1 large, urban school district limits generalizability; low response rate and potential selection bias; responses to hypothetical program do not reflect likelihood of action |

| [29] | 3 school located vaccination campaigns for multiple vaccines, including influenza vaccine, and delivered by researchers and local hospital | To determine parental trust and effect of trust-building interventions in school-located vaccination, including influenza vaccination | 8 middle schools in a large, low-income, urban school district in Texas | Survey based on trust measures [36] of 1608 parents (year 1); 844 parents (year 2) | Trust survey adapted from Dugan et al. [36] | Annual household income, survey language version, participation in a previous SLIV, child’s health insurance status, and perceived vaccine importance were significantly associated with parental trust in SLIV (multiple linear regression analysis; R2: .06, p < .001) | Baseline trust in SLV was moderately high among low-income parents; higher trust and participation can be attained by increasing parents’ perception of vaccine importance | Low response rate and nonresponse bias; cannot validate responses from self-reported data |

Allison et al. surveyed elementary school parents in Salt Lake City, Utah and found that SLIV programs should address vaccine safety, benefit, cost, and convenience, while promoting vaccination as a social norm [9]. Brown et al. conducted an online survey of a nationally representative sample of parents, whose youngest child was less than 15 years old. While the convenience of SLIV promoted parental acceptance, parents preferred a medical location for proper administration and for care of potential medical needs and side effects. Vaccine safety was a significant barrier to consent [11]. Carpenter et al. briefly surveyed parents of large metropolitan public school system in Knoxville, Tennessee and found that significant barriers to SLIV participation included concerns regarding vaccine adverse effects and vaccine virus transmission to household members with health issues such as asthma [7]. A two-year survey conducted by Cheung et al. in urban elementary schools of Los Angeles County, California found that parents with better understanding of influenza risks and influenza vaccine benefits were more likely to consent to SLIV [23]. Gargano et al. surveyed middle and high school parents in Richmond County, Georgia and found that SLIV acceptance by parents correlated with parental beliefs of influenza vaccination being a social norm and perception of illness severity prevented by vaccination in general [24]. Kelminson et al. conducted a survey of parents in urban/suburban middle schools in Aurora, Colorado and found that belief in vaccine importance was associated with SLIV acceptance; parental absence during vaccination was a major barrier to consent [25]. Kempe et al. conducted a survey of public elementary school parents in a low-income area of Denver, Colorado and found that SLIV was strongly supported by parents due to belief in vaccine efficacy and convenience of school setting, while the barriers involved concerns regarding vaccine safety and parental absence during vaccination [26].

Focus group discussions of parents and students were conducted by Herbert et al. in a low-income, rural county of Georgia; the barriers of non-participating parents in SLIV involved distrust, suspicions of the vaccination clinic, and the lengthy consent process [27]. Middleman et al. held focus groups of elementary, middle, and high school parents in a large urban school district of Houston, Texas and found that parental attitudes to SLIV were impacted by safety and trust issues regarding vaccines in general; programs should effectively communicate information regarding competency of health personnel administering the vaccine and equipment sterility [28]. In a related study, Middleman et al. conducted a survey of parent-student dyads in a large urban Houston school district; authors found that parental participation in SLIV was impacted by equipment sterility, universal access of vaccines for all students, and cost [12]. Lastly, Won et al. conducted a 2-year survey of middle school parents in a low-income urban school district and found that baseline trust in SLIV programs was moderately high among low-income parents, while higher trust and participation of SLIV may be attained by increasing parents’ perception of vaccine importance [29].

Facilitators

The facilitators of parental attitudes and beliefs toward SLIV in the United States are illustrated in Table 2 and described below.

Table 2. Facilitators.

Facilitators of parental attitudes and beliefs toward school-located influenza vaccination (SLIV) in the United States.

| Promoting Factor | Description | Study |

|---|---|---|

| Cost | Offering free/low cost vaccines | [9,12,28] |

| Vaccine efficacy | Belief in vaccine efficacy | [26] |

| Influenza severity | Belief in perceived severity of influenza | [23,24] |

| Influenza illness susceptibility | Parental belief in children being susceptible to influenza and risk concerns of H1N1 influenza | [9,11,23] |

| Vaccine benefits | Belief in benefit of influenza vaccine to protect against influenza illness | [9,23,24] |

| Vaccine importance | Belief in importance of vaccination in general | [25,29] |

| Vaccination is a social norm | Belief that vaccination is a social norm | [9,24] |

| Influenza vaccine does not cause influenza | Belief that the influenza vaccine does not cause influenza | [9] |

| Medical setting barriers | Perception of inconvenience in accessing regular medical settings for vaccination | [9] |

| School setting advantages | Perception of convenience in accessing school setting for vaccination | [11,26–28] |

| Parental presence during vaccination | Parents being present during vaccination after school or during weekends | [28] |

| Discussion with health care provider | Positive discussion with health care provider about influenza vaccination | [9] |

| Trust in school health personnel | Trust in competency of health personnel administering the influenza vaccine | [28] |

| Universal vaccine access in school | Access and availability of influenza vaccine for all students in school | [12,28] |

Cost

Parents were willing to participate in SLIV if they had no additional out-of-pocket expenses [9]. Free or low cost vaccines were significant facilitators of parental acceptance [28] but were less important when compared to other factors [12].

Vaccine efficacy

Parents with higher belief in vaccine efficacy were inclined to participate in SLIV [26].

Influenza severity

Parents with higher perceived severity of adolescent illness, including influenza, were more likely to accept SLIV [24]. Perceived severity of influenza illness was a predicting factor for parental consent [23].

Influenza illness susceptibility

Parental belief of their child being susceptible to influenza was a predicting factor of SLIV consent [23] and associated with acceptance if vaccines were offered for free [9]. Parents who had worried about the H1N1 virus in 2009 were also more likely to consent to SLIV participation [11].

Vaccine benefits

Parents with higher perceived benefit of influenza vaccine protecting against illness [23], combined with stronger belief in vaccination as a social norm [24] were more inclined to accept SLIV. The belief in vaccine benefit was also associated with acceptance if vaccines were offered free of cost [9].

Vaccine importance

Parental perception of vaccine importance was directly correlated with acceptance and trust in SLIV [25,29].

Vaccination as a social norm

Social norms were associated with parental acceptance of school-located vaccination in general and for influenza vaccine specifically when compared to other adolescent vaccines [24]. Parental belief in vaccination as a social norm was associated with acceptance of SLIV if the vaccine was offered for free [9].

Influenza vaccine does not cause influenza

Parental belief in influenza vaccine not causing influenza was associated with acceptance of SLIV if the vaccine was offered for free [9].

Medical setting barriers

Endorsement of medical setting barriers such as inconvenience and time constraints promoted SLIV acceptance [9].

School setting advantages

Parents perceiving school-located vaccinations as convenient also facilitated SLIV acceptance [11,26–28].

Parental presence during vaccination

Flexible vaccination scheduling, such as during evenings or weekends, allowing parents to accompany children increased likelihood of SLIV participation [28].

Discussion with health care provider

Positive discussion about influenza vaccination and advice from a health care provider promoted parental consent and participation [9].

Trust in school health personnel

Having knowledge of credentials and having trust in the competency of health personnel administering vaccines improved parental consent [28].

Universal vaccine access in school

Ensuring availability of influenza vaccines for all students was an important factor for parental acceptance—more important than offering free or low cost vaccines [12].

Barriers

The barriers of parental attitudes and beliefs toward SLIV in the United States are illustrated in Table 3 and described below.

Table 3. Barriers.

Barriers of parental attitudes and beliefs toward school-located influenza vaccination (SLIV) in the United States.

| Barrier | Description | Study |

|---|---|---|

| Cost | Concerns of potential billing related to school-located vaccination | [9,25,26,28] |

| Vaccine safety | Safety concerns of vaccines in general, including the influenza vaccine | [9,11,12,23,26,28] |

| Equipment sterility | Trust concerns of cleanliness and sterility of equipment used for vaccination | [12,28] |

| Vaccine efficacy | Concerns of vaccine efficacy | [9] |

| Influenza non-susceptibility | Parental belief that their children are not susceptible to influenza | [9] |

| Adverse effects | Concerns of adverse effects from vaccination | [7,23,27] |

| Influenza illness acquisition from vaccine | Concerns of acquisition of influenza illness from influenza vaccine | [7,26] |

| Medical setting advantages | Parents preferred vaccination at regular medical settings for trust and safety reasons | [11,23,26–28] |

| School setting barriers | Concerns regarding competency of person administering the vaccine, school disorganization, and inability to address medical issues | [9,25,27,28] |

| Parental absence during vaccination | Parents did not want their children to receive vaccinations in their absence | [9,23,25,26] |

| Discussion with health care provider | Negative physician advice based on incorrect live-attenuated influenza vaccine contraindications and concerns of vaccine virus transmission to household members with health issues such as asthma | [7] |

| Distrust of vaccines and vaccination programs | Distrust and skepticism about the vaccination program and vaccines in general, including influenza vaccine. | [27,28] |

| Health insurance information | Unwillingness of parents to provide health insurance information | [26] |

| Health information privacy | Privacy concerns of use/misuse of collected medical information and distrust of vaccination program | [27] |

| Pharmaceutical company | Lack of knowledge of pharmaceutical company manufacturing the influenza vaccine | [28] |

Cost

Parents were less likely to participate in SLIV due to cost [25,26] especially with multiple children in the household [9], however, it was not a primary concern when compared to other barriers [28].

Vaccine safety

Parental concerns of vaccine safety in general, including influenza vaccine in particular [9,23,26], and risks [11] lowered their support to participate in SLIV.

Equipment sterility

Negative perceptions regarding sterility of equipment used for vaccine administration in a school setting was a significant factor impacting parental decision to trust and participate in SLIV [12].

Vaccine efficacy

Parents concerned with vaccine efficacy were less willing to participate in SLIV [9].

Influenza non-susceptibility

Parents with belief that their children were not susceptible to influenza were less likely to participate in SLIV [9].

Adverse effects

Parents concerned of vaccine side effects were less likely to consent to SLIV [23,27], with common concerns involving adverse effects of the live-attenuated influenza vaccine [7].

Influenza illness acquisition from vaccine

Parental concerns regarding influenza illness acquisition from the influenza vaccine was a barrier to SLIV participation [7].

Medical setting advantages

Parents preferred a medical setting for vaccination due to trust and safety issues regarding the child’s well-being [26,27], potential side effects, and for proper vaccine administration [11,23,28].

School setting barriers

Parental consent and acceptance of school vaccine delivery involved concerns regarding competency of person delivering the vaccine [9], the lengthy consent process [27], disorganization of the school [25], and the inability to address potential medical issues [28].

Parental absence during vaccination

Parents wanting to be present during the child’s vaccination were less inclined to consent for SLIV in their absence [9,23] [26]. Parents who felt that their children would want them present during vaccination was also a notable barrier [25].

Discussion with health care provider

Receiving negative physician advice based on incorrect contraindications of the live-attenuated influenza vaccine deterred parental participation in SLIV [7].

Distrust of vaccines and vaccination programs

Parents expressing skepticism of the influenza vaccine and/or the school-located vaccination program opted to either vaccinate their children through primary care physicians and pharmacies, or forgo influenza vaccination entirely. Negative attitudes toward the university-implemented vaccination program and associated misperceptions of research being performed on their children (i.e. to test an experimental vaccine) was a distinct barrier to SLIV participation [27].

Health insurance information

Parents were unwilling to provide health insurance information for billing, acting as a barrier to SLIV participation [26].

Health information privacy

Parents who were uncertain of the use/misuse of health information collected from their children’s medical records were reluctant to consent to SLIV [27].

Pharmaceutical company

Poor communication and lack of knowledge regarding the pharmaceutical company manufacturing the influenza vaccine deterred parent participation of SLIV [28]

DISCUSSION

Facilitators

Our review found that free or low cost vaccines generally facilitated parental acceptance of school-located influenza vaccination (SLIV) [9,12,28]. Parental acceptance is likely to be further facilitated by the Affordable Care Act [30] of 2010 which requires influenza (and other vaccines) to be covered by health insurance without charging a copayment or coinsurance, and the uninsured rate have declined by 43% from 16.0% in 2010 to 9.1% in 2015 [31]. Parents perceiving the convenience of a school setting over medical settings for vaccination were relatively more likely to consent [9,11,26–28]; having a positive discussion with a health care provider [9] and trusting the competency of health personnel administering the vaccine [28] significantly enhanced parental attitudes and acceptance for SLIV programs. Parents also preferred the scheduling of SLIV to take place after school or during weekends to allow parents the ability to accompany children during vaccination [28]. Additionally, the availability of influenza vaccines for all students was an important factor for parents [12,28].

Studies utilizing the Health Belief Model (HBM) [32] suggested that parents with enhanced perceptions of influenza susceptibility and severity, risks of H1N1 influenza, and benefits of influenza vaccination (including belief that the influenza vaccine does not cause influenza) were more likely to accept SLIV for their children [9,23,24,26]. Having beliefs in vaccine efficacy [26], vaccine importance [25,29], and vaccination as a social norm [9,24] also promoted SLIV acceptance among parents. While most parents accepting of vaccines also consented to SLIV, some parents with no intention of vaccinating for influenza also stated willingness to participate if SLIV became available [9,24].

Barriers

Significant barriers to SLIV acceptance were often related to the elements of the influenza vaccine, including concerns regarding vaccine safety [9,11,12,23,26,28], vaccine efficacy [9], vaccine adverse effects [7,23,27], and the risk of influenza acquisition from the vaccine itself [7].

Parental distrust of the school-located vaccination program was a notable barrier to participation, particularly for SLIV implemented by an external entity in a school setting without a health clinic [27]. Vaccine trust issues involved skeptical attitudes toward the vaccine [11,27,28], concerns regarding equipment sterility and cleanliness of the school location [12,28], and lacking knowledge of the pharmaceutical company that manufactured the vaccine [28]. Parents were unwilling to provide health insurance information for billing [26], and due to distrust in the vaccination program, parents felt uncertain regarding use/misuse of health information collected from medical records of their children [27].

Trust issues, safety concerns, and medical setting advantages presented barriers for vaccination within a school setting [11,23,26–28]. Common concerns involved competency of health personnel administering the vaccine and their ability to address potential medical issues in a school setting [9,25,27,28]; many parents did not want their children to receive vaccination in their absence [9,23,25,26]. Other barriers included parental belief that their children were not susceptible to influenza [9] and having received physician advice that negatively portrayed live-attenuated influenza vaccination due to an incorrect understanding of contraindications [7]. Lastly, vaccine cost was generally perceived as a minor barrier for parents [9,25,26,28].

School-located influenza vaccination in school-based clinics versus delivery by external agencies

The studies included in this systematic review assessed parental attitudes and beliefs in relation to hypothetical SLIV scenarios and pilot program contexts. The pilot studies summarized here utilized external agencies such as health departments [7,23,26], university research staff [27], and hospitals [29] to deliver influenza vaccination in schools, as opposed to utilizing a school-based health clinic that is offered year-round; these two scenarios may present different issues of trust and concern among parents. Due to considerable heterogeneity in the format of school-located vaccination programs [25], future SLIV programs should take various scenarios into consideration during planning phases.

Limitations

Studies in this review reported limitations of low response rates [7,11,12,23,24,29], limited generalizability [9,11,12,23,24,26–29], and potential selection bias [12,23–25,28]. Some studies were geared towards hypothetical SLIV programs in the future [11,12,25], and thereby, the responses of parents were based on potential action rather than actual behavior.

Differences in survey development, analysis, and subjective interpretation of qualitative responses of parents by authors limited comparability across studies as well as prioritization of parental barriers and facilitators. However, study findings encompass diversely varied populations and geographic regions within the United States which provides collective insight for potential prioritization within specific communities.

While the review of literature in this study is from 1990 to 2016, publication dates of reviewed articles span from 2007 to 2015, with only two studies conducted before the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic. Thus, the analysis timeline of this systematic review may be biased towards studies after the 2009 H1N1 pandemic and possibly reflect elevated awareness of influenza among parental attitudes and beliefs toward SLIV programs. Additionally this may be reflective of the nature of discourse surrounding recent utilization of school-located immunization programs, signifying a young and evolving concept and area which necessitates further study.

Public health implications

Effective from the 2010–2011 influenza season, the ACIP recommends seasonal influenza vaccination annually for individuals aged 6 months and older without contraindications to prevent and control seasonal and pandemic influenza [33]. The Healthy People 2020 initiative includes the target of influenza vaccination coverage of 70% [18]. Yet, influenza vaccination coverage in the general population was below par, ranging from 36.8% in Nevada to 56.6% in South Dakota during the 2015–2016 influenza season, with a national vaccination coverage among children (6 months – 17 years) of 59.3% [34]. In this systematic review, we identified the facilitators and barriers of parental attitudes and beliefs toward SLIV for children in the United States that can assist in improving coverage and effectiveness of SLV programs. Specifically, influenza vaccination coverage is improved among children whose parents did not plan to vaccinate in the absence of a school-located program [9,24]. Further, improving influenza vaccination coverage among school children in general improves herd immunity in the total population. The Affordable Care Act [30] of 2010 lowered the uninsured rate by 43% from 16.0% in 2010 to 9.1% in 2015 [31], and health insurance now covers influenza vaccines without additional out-of-pocket payments. While cost has become a lesser barrier, SLV programs can facilitate improved access to influenza vaccination for school-aged children.

Systems thinking in school-located influenza vaccination

Health program strategies based on systems thinking focus on an ongoing iterative learning of systems understanding, analysis and improvement, and leadership and collaboration across disciplines, sectors, and organizations [35]. School-located influenza vaccinations are collaborative programs between health and education sectors with great potential for improving influenza vaccination coverage among school-aged children. SLIV programs directly benefit vaccinated children who express protective immune response, as well as indirectly benefiting the larger community by reducing transmission pathways. We identified facilitators and barriers of parental attitudes and beliefs toward SLIV from a systems thinking perspective. Through systematic understanding, analysis, and identification of facilitators and barriers, this study provides evidence to improve the design and implementation of current and future SLIV programs by leveraging key promoting factors and addressing potential barriers.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study is supported by NIH/NIGMS R01GM109718 and NSF/NRT 1545362; the funding sources had no role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the paper; or the decision to submit it for publication.

This study is supported by NIH NIGMS R01GM109718 and NSF/NRT 1545362. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agency.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Middleman A. School-located vaccination for adolescents: Past, present, and future and implications for HPV vaccine delivery. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12:1599–605. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1168953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hull HF, Ambrose CS. Current experience with school-located influenza vaccination programs in the United States. Hum Vaccin. 2011;7:153–60. doi: 10.4161/hv.7.2.13668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogilvie G, Anderson M, Marra F, McNeil S, Pielak K, Dawar M, et al. A population-based evaluation of a publicly funded, school-based HPV vaccine program in British Columbia, Canada: parental factors associated with HPV vaccine receipt. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell M, Raheja V, Jaiyesimi R. Human papillomavirus vaccination in adolescence. Perspect Public Health. 2013;133:320–4. doi: 10.1177/1757913913499091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brotherton JML, Deeks SL, Campbell-Lloyd S, Misrachi A, Passaris I, Peterson K, et al. Interim estimates of human papillomavirus vaccination coverage in the school-based program in Australia. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep. 2008;32:457–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Effler PV, Chu C, He H, Gaynor K, Sakamoto S, Nagao M, et al. Statewide school-located influenza vaccination program for children 5–13 years of age, Hawaii, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:244–50. doi: 10.3201/eid1602.091375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carpenter LR, Lott J, Lawson BM, Hall S, Craig AS, Schaffner W, et al. Mass distribution of free, intranasally administered influenza vaccine in a public school system. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e172–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King JC, Jr, Stoddard JJ, Gaglani MJ, Moore KA, Magder L, McClure E, et al. Effectiveness of school-based influenza vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2523–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allison MA, Reyes M, Young P, Calame L, Sheng X, Weng H-YC, et al. Parental attitudes about influenza immunization and school-based immunization for school-aged children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:751–5. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181d8562c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Middleman AB, Tung JS. Urban middle school parent perspectives: the vaccines they are willing to have their children receive using school-based immunization programs. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:249–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown DS, Arnold SE, Asay G, Lorick SA, Cho B-H, Basurto-Davila R, et al. Parent attitudes about school-located influenza vaccination clinics. Vaccine. 2014;32:1043–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Middleman AB, Short MB, Doak JS. School-located influenza immunization programs: factors important to parents and students. Vaccine. 2012;30:4993–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tran CH, Sugimoto JD, Pulliam JRC, Ryan KA, Myers PD, Castleman JB, et al. School-located influenza vaccination reduces community risk for influenza and influenza-like illness emergency care visits. PLoS One. 2014;9:e114479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pannaraj PS, Wang H-L, Rivas H, Wiryawan H, Smit M, Green N, et al. School-located influenza vaccination decreases laboratory-confirmed influenza and improves school attendance. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:325–32. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weycker D, Edelsberg J, Halloran ME, Longini IM, Jr, Nizam A, Ciuryla V, et al. Population-wide benefits of routine vaccination of children against influenza. Vaccine. 2005;23:1284–93. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Update on influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent vaccines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1100–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. [accessed February 21, 2017];Flu Vaccination Coverage, United States, 2015–16 Influenza Season | FluVaxView | Seasonal Influenza (Flu) | CDC. n.d https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1516estimates.htm.

- 18. [accessed February 21, 2017];Healthy People 2020. n.d https://www.healthypeople.gov/

- 19.Piedra PA, Gaglani MJ, Kozinetz CA, Herschler G, Riggs M, Griffith M, et al. Herd immunity in adults against influenza-related illnesses with use of the trivalent-live attenuated influenza vaccine (CAIV-T) in children. Vaccine. 2005;23:1540–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cummings GE, Ruff E, Guthrie SH, Hoffmaster MA, Leitch LL, King JC., Jr Successful use of volunteers to conduct school-located mass influenza vaccination clinics. Pediatrics. 2012;129(Suppl 2):S88–95. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0737H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King JC, Jr, Lichenstein R, Cummings GE, Magder LS. Impact of influenza vaccination of schoolchildren on medical outcomes among all residents of Maryland. Vaccine. 2010;28:7737–42. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheung S, Wang H-L, Mascola L, El Amin AN, Pannaraj PS. Parental perceptions and predictors of consent for school-located influenza vaccination in urban elementary school children in the United States. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2015;9:255–62. doi: 10.1111/irv.12332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gargano LM, Weiss P, Underwood NL, Seib K, Sales JM, Vogt TM, et al. School-Located Vaccination Clinics for Adolescents: Correlates of Acceptance Among Parents. J Community Health. 2014;40:660–9. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9982-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelminson K, Saville A, Seewald L, Stokley S, Dickinson LM, Daley MF, et al. Parental views of school-located delivery of adolescent vaccines. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51:190–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kempe A, Daley MF, Pyrzanowski J, Vogt TM, Campagna EJ, Dickinson LM, et al. School-located influenza vaccination with third-party billing: what do parents think? Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:241–8. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herbert NL, Gargano LM, Painter JE, Sales JM, Morfaw C, Murray D, et al. Understanding reasons for participating in a school-based influenza vaccination program and decision-making dynamics among adolescents and parents. Health Educ Res. 2013;28:663–72. doi: 10.1093/her/cyt060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Middleman AB, Short MB, Doak JS. Focusing on flu: Parent perspectives on school-located immunization programs for influenza vaccine. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012;8:1395–400. doi: 10.4161/hv.21575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Won TL, Middleman AB, Auslander BA, Short MB. Trust and a school-located immunization program. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:S33–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.About the Law. [accessed February 21, 2017];HHS.gov. 2013 https://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/about-the-law/

- 31.Obama B. United States Health Care Reform: Progress to Date and Next Steps. JAMA. 2016;316:525–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.9797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janz NK, Champion VL, Strecher VJ. The health belief model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health behavior and health education: theory, research and practice. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33. [accessed July 3, 2015];CDC - ACIP - Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Home Page - Vaccines. n.d http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/

- 34. [accessed February 21, 2017];2015–16 Influenza Season Vaccination Coverage Report | FluVaxView | Seasonal Influenza (Flu) | CDC. n.d https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/reportshtml/reporti1516/reporti/index.html.

- 35.Swanson RC, Cattaneo A, Bradley E, Chunharas S, Atun R, Abbas KM, et al. Rethinking health systems strengthening: key systems thinking tools and strategies for transformational change. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(Suppl 4):iv54–61. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dugan E, Trachtenberg F, Hall MA. Development of abbreviated measures to assess patient trust in a physician, a health insurer, and the medical profession. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:64. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]