Abstract

Introduction

This paper estimated the association between the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s 2009 ban on flavored cigarettes (which did not apply to menthol cigarettes or tobacco products besides cigarettes) and adolescents’ tobacco use.

Methods

Regression modeling was used to evaluate tobacco use before and after the ban. The analyses controlled for a quadratic time trend, demographic variables, prices of cigarettes and other tobacco products, and teenage unemployment rate. Data from the 1999–2013 National Youth Tobacco Surveys were collected and analyzed in 2016. The sample included 197,834 middle and high schoolers. Outcomes were past 30–day cigarette use; cigarettes smoked in the past 30 days among smokers; rate of menthol cigarette use among smokers; and past 30–day use of cigars, smokeless tobacco, pipes, any tobacco products besides cigarettes, and any tobacco products including cigarettes.

Results

Banning flavored cigarettes was associated with reductions in the probability of being a cigarette smoker (17%, p<0.001) and cigarettes smoked by smokers (58%, p=0.005). However, the ban was positively associated with the use of menthol cigarettes by smokers (45%, p<0.001), cigars (34%, p<0.001), and pipes (55%, p<0.001), implying substitution toward the remaining legal flavored tobacco products. Despite increases in some forms of tobacco, overall there was a 6% (p<0.001) reduction in the probability of using any tobacco.

Conclusions

The results suggest the 2009 flavored cigarette ban did achieve its objective of reducing adolescent tobacco use, but effects were likely diminished by the continued availability of menthol cigarettes and other flavored tobacco products.

INTRODUCTION

Despite substantial recent progress in reducing cigarette smoking among adolescents, use of other tobacco products has not declined similarly. According to the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, between 2007 and 2013, the cigarette smoking rate among high school students dropped by 22% (from 20% to 15.7%, p<0.001). However, cigar use declined by only 7% (13.6% to 12.6%, p>0.10) whereas smokeless tobacco use rose by 11% (7.9% to 8.8%, p>0.10).1 Among middle and high school students in the National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS), cigarette smoking dropped by 32% (p<0.001) from 2006 to 2013 but cigar smoking rose by 3% (p>0.10) and smokeless tobacco use fell by just 2% (p>0.10) (authors’ calculations).

The continued popularity of non-cigarette tobacco products is concerning because they are also addictive and pose serious health consequences. The risks of cigars are similar to those of cigarettes, and cigars can be particularly dangerous for people switching from cigarettes because they tend to continue inhaling.2 Although smokeless tobacco products—such as chewing tobacco, snuff, and snus—may be less harmful than smoking, there is evidence that smokeless tobacco use increases the risk of oral cancer, lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, and cardiovascular disease.3

In curbing teen tobacco use, flavored tobacco is a particular threat. Sweet flavors based on fruit, candy, dessert, and liqueur are particularly attractive to younger smokers as they mask the acrid tobacco flavor to make cigarettes more palatable and increase tobacco’s curiosity factor, particularly for high sensation–seeking teens.4–6 A review of internal industry documents finds tobacco companies designed flavored products to appeal to young and novice smokers.5 These products were also marketed most heavily to younger smokers with twice as many adolescents aged 12–17 years seeing flavored tobacco ads as adults in 2008.7 The strategy appeared to be effective: In 2004, there were three times as many 17-year-old smokers (22.8%) using flavored cigarettes in the preceding month as smokers aged >25 years (6.7%).8 Furthermore, the majority of ever tobacco users report that the first product they tried was a flavored variety,9,10 supporting the concern that these products may serve as a gateway to tobacco addiction.

To address this youth-targeted appeal of tobacco, in 2009, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration passed the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, which banned all flavored cigarettes with the exception of menthol. Because this ban was only on flavored cigarettes, other tobacco products—such as cigars, chewing tobacco, snuff, dip, snus, e-cigarettes, and hookah—could continue to come in any flavor. In the Food and Drug Administration’s press release the day the ban became effective, the agency stated that it was “examining options for regulating both menthol cigarettes and flavored tobacco products other than cigarettes”6; however, as of July 2016, it has not announced plans to do so.

The flavored products that remain legal present important concerns for adolescent tobacco use. Numerous studies have found that cigarette smokers who use primarily menthol cigarettes tend to be younger and newer smokers, progress to becoming established smokers faster, are more nicotine dependent, and have less successful quit attempts.11–14 Cigars, which are still permitted to be flavored and are also taxed at lower rates than cigarettes,15 are potential substitutes for flavored cigarettes. This is particularly true of little cigars, which are often mistaken as cigarettes16,17 because they are nearly identical in terms of size, packaging, and the use of filters but differ legally because they are wrapped in tobacco leaves or paper containing tobacco.18–20 Internal tobacco industry documents indicate that during the 1970s some little cigars were intentionally designed to resemble cigarettes as much as legally possible while getting around cigarette restrictions such as the advertising ban.20 Little cigars may now be used to circumvent the flavor ban. According to Nielsen Scanner data, 47.9% of cigars purchased at 20 large convenience store chains in 2013 were sweet or flavored, and the share of little cigars that are flavored is even higher.21,22 Smokeless tobacco is also commonly flavored, with 81% of users aged 12–17 years choosing flavored varieties.9

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first to examine how adolescent tobacco use changed in response to the national flavored cigarette ban. By removing flavors from cigarettes, the ban intended to reduce adolescent cigarette use. However, some adolescents may have switched from non-menthol flavored cigarettes to menthol cigarettes or other flavored tobacco products. The ban could therefore have led to a reduction in the prevalence of non-menthol cigarette smoking while increasing cigar, smokeless tobacco, pipe, and menthol cigarette use. Such switching behavior could provide support for broader regulations of menthol cigarettes and other flavored tobacco products.

METHODS

Data Sample

Data from the 1999, 2000, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2009, 2011, 2012, and 2013 NYTS were collected in 2016. Each survey asked a nationally representative sample of middle and high school students about initiation and current use of a variety of tobacco products. Students took the survey independently and anonymously by filling out a scannable booklet. The sample was selected using a three-stage cluster method: first by primary sampling units, then schools within the primary sampling unit, and then students within the schools. Participation was voluntary at the school and student level. In 2013, a total of 250 schools were selected to participate, of which 187 did so (74.8% participation). At the student level, the participation rate was 90.7%. Weights were used to adjust for non-response and differences in selection probabilities.

Eight outcome variables were used. Four of them were binary measures of whether the respondent used cigarettes, cigars (including little cigars), smokeless tobacco, and pipes in the past 30 days. Additionally, a variable was created for whether or not people who smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days usually used menthol cigarettes. Responses of unsure or no consistent preference were coded as missing. Another outcome was the number of cigarettes smoked in the past 30 days, also defined only for cigarette smokers. This variable equals the number of days a respondent smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days multiplied by the average number of cigarettes smoked on each day the individual smoked cigarettes. These two questions reported the answers in bins, so the midpoints of the bins the respondent chose were used before multiplying them. For example, an individual smoking between five to ten cigarettes a day for between 20–30 days received a value of 7.5 × 25=187.5, which rounds to 188. Results were robust to the use of top or bottom anchor points rather than midpoints. The last two outcomes were summary measures of tobacco use: indicators for whether in the past 30 days respondents used any tobacco products besides cigarettes (i.e., cigars, smokeless tobacco, or pipes) and whether they used any tobacco products including cigarettes.

Several control variables were included in the regressions. The individual-level controls were respondent’s age (dummy variable for each year), gender (dummy variable for male), and race/ethnicity (dummy variables for Native American, Asian, black, Pacific Islander, and Hispanic). Two national-level controls were the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS’) tax-inclusive price indices for cigarettes and tobacco products besides cigarettes.23 These indices were adjusted for general inflation using the overall Consumer Price Index, also provided by the BLS. During the sample period, the cigarette price index increased by 39.1% beyond general inflation, and the non-cigarette tobacco price index increased by 26.9% beyond general inflation. The BLS data do not distinguish between the prices of mentholated and non-mentholated cigarettes. However, the annual average prices of these two categories of cigarettes have an extremely strong correlation of 0.985 in 2006–2014 Nielsen scanner data (authors’ calculation), so this limitation is unlikely to affect the results. Finally, to mitigate confounding from changes in economic climate, including from the Great Recession that officially occurred from December 2007 to June 2009, another national-level control was the unemployment rate for youth aged 16–19 years from the BLS. This variable ranged from 13.1% in 2000 to 24.4% in 2011.

Observations with missing data for any variable were dropped, with the exception of menthol cigarettes and cigarettes per day, which had missing values by construction as they were only defined for smokers. The sample consisted of 197,834 individuals aged 11–19 years.

Statistical Analysis

The econometric strategy estimated the covariate-adjusted deviation from the outcome’s trend after 2009, the year of the flavored cigarette ban. Separate regressions were run for each of the aforementioned outcomes and listed in the top panel of Table 1. As the ban took effect in September 2009 but the 2009 NYTS survey was administered in the spring, the 2009 wave is a pre-treatment year. Regressions were estimated that included a dummy variable for post-2009, a quadratic time trend (year and year squared), and the demographic and economic controls discussed above.

Table 1.

Sample Means

| Variable | Before ban | After ban | change | Percent Change | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | |||||

| Any cigarettes past 30 days | 0.140 | 0.093 | −0.048 | −34.0% | 0.003 |

| Cigarettes in past 30 days (cigarette users) | 113.215 | 98.366 | −14.849 | −15.1% | 0.059 |

| Usually smoke menthols (cigarette users) | 0.453 | 0.525 | 0.071 | 15.9% | 0.006 |

| Any cigars past 30 days | 0.077 | 0.077 | −0.000 | −0.1% | 0.979 |

| Any smokeless tobacco past 30 days | 0.042 | 0.041 | −0.001 | −2.1% | 0.806 |

| Any pipe smoking past 30 days | 0.023 | 0.028 | 0.005 | 21.7% | 0.000 |

| Any cigars, smokeless, or pipe past 30 days | 0.102 | 0.107 | 0.005 | 5.3% | 0.128 |

| Any cigarettes, cigars, smokeless, or pipe past 30 days | 0.179 | 0.144 | −0.035 | −19.6% | 0.011 |

| Controls | |||||

| Age=12 (Age=11 is the referent category) | 0.137 | 0.133 | −0.005 | −3.5% | 0.205 |

| Age=13 | 0.154 | 0.150 | −0.004 | −2.6% | 0.409 |

| Age=14 | 0.153 | 0.145 | −0.008 | −5.2% | 0.048 |

| Age=15 | 0.155 | 0.152 | −0.003 | −1.7% | 0.423 |

| Age=16 | 0.144 | 0.147 | 0.002 | 1.7% | 0.223 |

| Age=17 | 0.130 | 0.137 | 0.007 | 5.0% | 0.157 |

| Age=18 | 0.068 | 0.079 | 0.011 | 15.6% | 0.001 |

| Age=19 | 0.007 | 0.007 | −0.000 | −2.5% | 0.636 |

| Male | 0.491 | 0.208 | 0.010 | 2.0% | 0.098 |

| Native American (white is the referent category) | 0.021 | 0.022 | 0.001 | 5.0% | 0.709 |

| Asian | 0.038 | 0.047 | 0.009 | 24.6% | 0.012 |

| Black | 0.157 | 0.169 | 0.011 | 7.3% | 0.098 |

| Hispanic | 0.148 | 0.208 | 0.060 | 40.9% | 0.001 |

| Pacific Islander | 0.009 | 0.008 | −0.000 | −5.7% | 0.453 |

| Cigarette price index | 112.861 | 151.928 | 39.07 | 34.6% | 0.002 |

| Non-cigarette tobacco price index | 79.627 | 101.037 | 21.410 | 26.9% | 0.001 |

| Unemployment rate for teens | 18.380 | 23.794 | 5.415 | 29.5% | 0.025 |

Notes: Sampling weights are used. p-values are based on SEs that are clustered by year. All means are from final analysis sample of 197,834 individuals with the exception of the cigarette users results which are based on 23,272 individuals who had smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days.

Standard approaches to estimation and inference were used. Regressions models were logistic for the binary outcomes and negative binomial for the count outcome number of cigarettes smoked. Overdispersion was evident in the data, so negative binomial was preferred to Poisson. SEs were heteroscedasticity-robust standard and clustered at the level of treatment: year. Significance levels of 0.1%, 1%, and 5% were used. Data were analyzed in 2016 using Stata, version 14.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents pre- and post-treatment means for all variables and p-values from tests of their equality. During the pre-treatment period, 14% of adolescents reported smoking cigarettes in the past 30 days. In the post period, this rate fell to 9.3%, a statistically significant decrease of 4.8 percentage points (p=0.003), or 34% of the pre-treatment rate. By contrast, there were only small and insignificant reductions in the use of cigars and smokeless tobacco, whereas pipe smoking became 21.7% (p<0.001) more prevalent relative to a low base rate of 2.3%. Cigarette users reduced their cigarette consumption by 15.1% (p=0.059) and the share of smokers typically smoking menthols rose from 45.3% to 52.5% (p=0.006). Overall, use of any tobacco in the past 30 days fell by 19.6% (p=0.011). Table 1 also documents statistically significant changes in demographic characteristics, tobacco prices, and the unemployment rate.

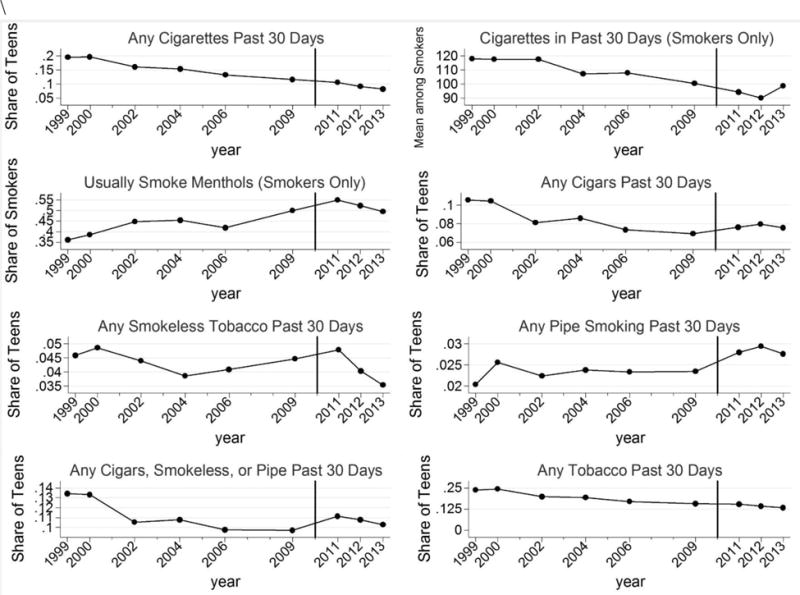

Figure 1 graphically depicts changes in adolescents’ use of cigarettes, menthols, cigars, smokeless tobacco, and combinations of these products during the sample period. The vertical line indicates the time of the ban. Prior to the ban, the graphs show downward trends in cigarette smoking and cigar use and an increasing tendency for cigarette smokers to smoke menthols. The trends in smokeless tobacco and pipe use were less clear, with both products having low rates of use throughout the sample period. Accounting for these trends is central to the regression strategy.

Figure 1.

Changes over time in tobacco use outcomes.

Table 2 presents the results from the covariate-adjusted regressions. For the binary outcomes (Columns 1 and 3–8), the table shows ORs from the logistic regressions along with SEs and statistical significance indicators. For the count outcome cigarettes per day among smokers (Column 2), the table displays the coefficient estimates, which have the same percentage interpretation as a log-linear model.

Table 2.

Regression Estimates of Associations Between Flavored Cigarette Bans and Tobacco Use Outcomes

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Variable | Any cigarettes past 30 days | Cigarettes in past 30 days (cigarette users) | Usually smoke menthols (cigarette users) | Any cigars past 30 days | Any smokeless tobacco past 30 days | Any pipe smoking past 30 days | Any cigars, smokeless tobacco, or pipe past 30 days | Any cigarettes, cigars, smokeless tobacco, or pipe past 30 days |

| Post-treatment |

0.829*** (0.0202) |

−0.585** (0.210) |

1.448*** (0.0616) |

1.344*** (0.0422) |

1.064 (0.0677) |

1.546*** (0.0626) |

1.142*** (0.0249) |

0.939*** (0.00864) |

| Years from start of sample (0 in 1999) |

0.863*** (0.00999) |

−0.296** (0.0958) |

1.029 (0.0212) |

0.939*** (0.0136) |

1.111*** (0.0331) |

1.108*** (0.0223) |

0.921*** (0.00967) |

0.872*** (0.00413) |

| Years from start of sample squared |

0.997*** (0.0000670) |

0.00177* (0.000708) |

0.996*** (0.000344) |

1.007*** (0.000243) |

0.988*** (0.000398) |

1.001* (0.000249) |

1.002*** (0.000230) |

1.001*** (0.0000857) |

| Age=12 |

2.369*** (0.497) |

1.037***(0.251) | 0.738 (0.268) |

2.173*** (0.229) |

1.898* (0.487) |

3.113*** (0.628) |

2.145*** (0.324) |

2.248*** (0.353) |

| Age=13 |

5.316*** (0.957) |

1.152***(0.237) | 0.863 (0.310) |

4.474*** (0.507) |

3.256*** (0.639) |

5.382*** (1.318) |

4.017*** (0.600) |

4.649*** (0.577) |

| Age=14 |

8.771*** (1.979) |

1.297***(0.183) | 0.860 (0.275) |

6.669*** (0.662) |

4.401*** (0.936) |

7.352*** (1.440) |

6.127*** (0.807) |

7.271*** (1.059) |

| Age=15 |

12.79*** (3.053) |

1.538***(0.234) | 0.883 (0.358) |

11.05*** (1.345) |

6.884*** (1.677) |

8.911*** (2.228) |

9.533*** (1.497) |

11.10*** (1.780) |

| Age=16 |

18.66*** (4.606) |

1.628*** (0.162) |

0.784 (0.294) |

15.41*** (2.591) |

9.818*** (2.878) |

9.177*** (2.332) |

13.33*** (2.668) |

16.14*** (2.894) |

| Age=17 |

22.25*** (5.616) |

1.744***(0.194) | 0.748 (0.330) |

17.94*** (2.969) |

10.52*** (3.312) |

8.995*** (3.129) |

15.24*** (3.073) |

19.54*** (3.515) |

| Age=18 |

31.10*** (7.908) |

1.877***(0.205) | 0.630 (0.272) |

27.42*** (4.719) |

13.46*** (4.386) |

11.96*** (3.800) |

22.58*** (4.797) |

28.46*** (5.295) |

| Age=19 |

45.83*** (15.16) |

2.557***(0.218) | 1.046 (0.421) |

29.91*** (7.290) |

27.02*** (11.55) |

29.44*** (8.985) |

27.08*** (8.212) |

33.09*** (8.751) |

| Male | 1.059 (0.0688) |

0.274***(0.0711) |

0.801*** (0.0435) |

1.796** (0.370) |

3.396* (1.663) |

1.726** (0.300) |

2.026** (0.507) |

1.324* (0.156) |

| Native American |

1.419*** (0.0594) |

0.113 (0.0768) |

1.081 (0.0976) |

1.333*** (0.0884) |

1.304*** (0.0450) |

1.782*** (0.254) |

1.292*** (0.0535) |

1.376*** (0.0444) |

| Asian |

0.372*** (0.0224) |

−0.115 (0.108) |

1.339* (0.198) |

0.392*** (0.0316) |

0.294*** (0.0173) |

0.568** (0.105) |

0.343*** (0.0225) |

0.345*** (0.0128) |

| Black |

0.558*** (0.0246) |

−0.0164 (0.0868) |

1.759** (0.326) |

1.103 (0.130) |

0.298*** (0.0149) |

0.773** (0.0717) |

0.822 (0.0858) |

0.704*** (0.0614) |

| Pacific Islander | 1.272 (0.201) |

0.246 (0.268) |

1.995*** (0.335) |

1.352*** (0.119) |

1.372 (0.242) |

2.087*** (0.375) |

1.282* (0.142) |

1.157 (0.103) |

| Hispanic | 0.919 (0.0439) |

−0.157* (0.0729) |

1.320*** (0.102) |

1.090** (0.0345) |

0.563*** (0.0282) |

1.745*** (0.107) |

0.933 (0.0345) |

0.889** (0.0347) |

| Cigarette price index |

0.994*** (0.000237) |

0.0156*** (0.00119) |

0.998 (0.000912) |

0.968*** (0.000602) |

1.033*** (0.00112) |

0.986*** (0.000561) |

0.984*** (0.000636) |

0.990*** (0.000330) |

| Noncigarette tobacco price index |

1.075*** (0.00671) |

0.126* (0.0505) |

0.995 (0.0105) |

1.000 (0.00776) |

0.988 (0.0154) |

0.956*** (0.0102) |

1.037*** (0.00565) |

1.053*** (0.00262) |

| Unemployment rate for teens |

0.950*** (0.00658) |

−0.205*** (0.0582) |

1.064*** (0.0113) |

1.102*** (0.00935) |

0.940***(0.0159) |

1.094*** (0.0122) |

1.013* (0.00565) |

0.980*** (0.00226) |

| Sample size | 197,834 | 23,272 | 23,272 | 197,834 | 197,834 | 197,834 | 197,834 | 197,834 |

Notes: Boldface indicates statistical significance (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001). ORs reported in columns (1)-(2) and (4)-(8). SEs, heteroscedasticity-robust and clustered by year, are in parentheses.

Columns 1–3 show results for the outcomes related to cigarettes. Columns 1 and 2 indicate the flavored cigarette ban was associated with a 17.1% reduction in the likelihood of being a cigarette smoker (p<0.001) and 59% fewer cigarettes smoked per month among smokers (p=0.005). Column 3 shows that the ban was associated with a 45% increase (p<0.001) in the probability that a smoker usually used menthol cigarettes.

Columns 4–6 present results for the non-cigarette tobacco use outcomes. The ban was associated with statistically significant (p<0.001) increases in the prevalence of cigar and pipe use, and positively but insignificantly associated with smokeless use. Cigar use associated with the ban rose 34.4% and any pipe use rose 54.6%.

The last two columns display the results for the summary measures. Column 7 indicates the ban was associated with an increase in the use of at least one non-cigarette tobacco product (cigars, smokeless tobacco, or pipes) of 14.2% (p<0.001). However, as shown in Column 8, the ban was associated with a statistically significant 6.1% reduction (p<0.001) in the probability of using any tobacco, including cigarettes.

Several significant results emerged for the control variables. All types of tobacco use increased significantly with age. Consistent with other literature,24 men were more likely to use all forms of tobacco. These results were statistically significant for all outcomes except smoking participation. Teen unemployment rate was significant in all regressions with a mixed pattern of signs. The coefficients on time/time squared were statistically significant in 15 of 16 cases. The signs suggest that the probability of being a cigarette smoker was on a steady downward trend whereas pipe smoking was steadily increasing. Cigarettes per day and the use of cigars, any non-cigarette tobacco products, and any tobacco products were on a U-shaped trajectory. Menthol cigarette and smokeless tobacco use were on an inverted U-shaped trajectory.

The authors also observed significant results for the tobacco price indices. The non-cigarette tobacco price index was positively associated with cigarette smoking and cigarettes smoked by smokers and negatively associated with any pipe smoking. As expected, the cigarette price index was negatively associated with smoking participation. Rising cigarette prices were associated with increases in the use of smokeless tobacco products but decreases in the use of alternative combustible tobacco products (cigars and pipes).

DISCUSSION

This study investigated how the ban on flavored cigarettes affected adolescents’ tobacco use. The ban was significantly associated with decreases in smoking participation and intensity. Adolescent smokers were more likely to choose menthols, suggesting substitution toward the one remaining legal cigarette flavor. Evidence also suggests substitution toward flavored tobacco products besides cigarettes, as cigar and pipe tobacco use significantly increased in response to the ban. The probability of using at least one non-cigarette tobacco product rose 14%, though the probability of using any tobacco products (including cigarettes) still fell by 6%. Therefore, despite some substitutability between products, the ban was ultimately effective at reducing adolescent tobacco use.

These results contribute to the literature examining how one form of tobacco can be substituted for another following changes that make it more difficult to purchase one type. One recent study found that sales of non-flavored tobacco products rose in New York City after the city banned all flavored tobacco products, excluding menthol.25 In the present study, flavors for non-cigarette tobacco products remained available following the federal cigarette flavor ban, and use of products that continue to offer flavors increased. The results imply that youth are using flavors in these alternative tobacco products, although the data do not permit differentiation of flavors versus non-flavors in non-cigarette tobacco products. Another study used price changes between mentholated cigarettes and non-mentholated cigarettes to explore how increasing the price of one affects demand for the other, finding only weak substitution.27 By contrast, the present study explored substitution from flavored cigarettes to mentholated cigarettes due to what may be viewed as a relatively extreme price change caused by removing one product, flavored cigarettes, from the market entirely. The results provided evidence of strong migration from flavored cigarettes to mentholated cigarettes.

Results for the cigarette price control variable also provided interesting insights regarding substitutability. First, the finding that higher cigarette prices were associated with greater smokeless tobacco use differs from the results of two other studies suggesting that cigarettes and smokeless tobacco are economic complements.28,29 Second, the estimates for cigarette price suggest that cigarettes in general are economic complements with cigars even though flavored cigarettes in particular appear to be economic substitutes to cigars (based on the estimate for the ban).

Limitations

An important caveat to the analyses is that estimating the causal effect of any national law is difficult because only time-series variation is available for identification. Although the regressions controlled for quadratic time trends and certain demographic and economic characteristics, it is not possible to completely rule out changes in other important determinants of tobacco use between 2009 and 2011. Future research should continue to investigate the effects of the flavored cigarette ban using different data and identification strategies.

Another limitation of this study is that NYTS data do not allow for the analysis of several relevant outcomes. For instance, the survey did not include questions on hookah or e-cigarette use until 2011, so there are no data on their prevalence prior to the ban. Both hookah and e-cigarettes are commonly flavored, and 89% of adolescents who use hookah and 85.3% who use e-cigarettes choose flavored varieties.9 Also, when examining the increase in non-cigarette tobacco products after the ban, it would be ideal to differentiate between flavored and unflavored to reinforce that flavoring is the driver behind switching. Unfortunately, NYTS lacks information on the flavoring of other tobacco products.

Another caveat is that, although the analyses controlled for a quadratic time trend, they did not allow for separate trends before and after the ban, as is common in regression discontinuity designs. This is because, with only three post-treatment time periods, it is impractical to attempt to identify changes in both levels and trends. Another avenue for future research would be to utilize higher-frequency data, such as sales data, that allow for the interaction of the time trend with the post-treatment indicator.

A final caveat is that NYTS consists of repeated cross-sections, preventing the observation of changes among the same individuals from before to after the ban. Panel data would be necessary to solidify the explanation that adolescents are switching between products, rather than some quitting cigarettes while others start using cigars, smokeless tobacco, and pipes.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, this study’s results suggest that the ban on flavored cigarettes was successful in curbing adolescent tobacco use but demonstrate the need for a more comprehensive approach to regulating tobacco flavorings. The finding that adolescents switched to other flavored tobacco products confirms the Food and Drug Administration’s concerns that this feature is powerfully appealing to youth. At the same time, these findings provide evidence that menthol is an appealing flavor alternative to some youth. Thus, broadening the ban to prohibit menthol cigarettes and flavored non-cigarette tobacco products has the potential to generate additional reductions in tobacco use.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by grant number P50DA036128 from the NIH/National Institute on Drug Abuse and U.S. Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products, and grant number U01CA154248 from the NIH/National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH or the Food and Drug Administration. We thank the Kilts-Nielsen Data Center at The University of Chicago Booth School of Business for providing tobacco price data (http://research.chicagobooth.edu/nielsen/).

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.CDC. Trends in the Prevalence of Tobacco Use. www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/yrbs/pdf/trends/us_tobacco_trend_yrbs.pdf. Accessed August 30, 2015.

- 2.Delnevo CD. Smokers’ Choice: what Explains the Steady Growth of Cigar Use in the U.S.? Public Health Rep. 2006;121(2):116–119. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tobacco Advisory Group of the Royal College of Physicians. Harm reduction in nicotine addiction: Helping people who can’t quit. 2007 www.sfata.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Harm-Reduction-in-Nicotine-Addiction.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2015.

- 4.Manning KC, Kelly KJ, Comello ML. Flavoured cigarettes, sensation seeking and adolescents’ perceptions of cigarette brands. Tob Control. 2009;18(6):459–465. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.029454. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tc.2009.029454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carpenter CM, Wayne GF, Pauly JL, Koh HK, Connolly GN. New cigarette brands with flavors that appeal to youth: tobacco marketing strategies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(6):1601–1610. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.6.1601. http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.24.6.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Food and Drug Administration. Candy and fruit flavored cigarettes now illegal in the United States; step is first under new tobacco law. 2009 www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm183211.htm. Accessed August 30, 2015.

- 7.Food and Drug Administration. Flavored Tobacco Product Fact Sheet. www.fda.gov/syn/html/ucm183198#1. Accessed August 30, 2015.

- 8.Klein SM, Giovino GA, Barker DC, Tworek C, Cummings KM, O’Connor RJ. Use of flavored cigarettes among older adolescent and adult smokers: United States, 2004–2005. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(7):1209–1214. doi: 10.1080/14622200802163159. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14622200802163159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ambrose BK, Day HR, Rostron B, et al. Flavored Tobacco Product Use Among U.S. Youth Aged 12–17 Years, 2013–2014. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1871–1873. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13802. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.13802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oliver AJ, Jensen JA, Vogel RI, Anderson AJ, Hatsukami DK. Flavored and nonflavored smokeless tobacco products: Rate, pattern of use, and effects. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(1):88–92. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts093. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/nts093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Food and Drug Administration. Preliminary Scientific Evaluation of the Possible Public Health Effects of Menthol Versus Nonmenthol Cigarettes. 2013 www.fda.gov/downloads/UCM361598.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2016.

- 12.Giovino GA, Villanti AC, Mowery PD, et al. Differential trends in cigarette smoking in the USA: is menthol slowing progress? Tob Control. 2015;24(1):28–37. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051159. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nonnemaker J, Hersey J, Homsi G, Busey A, Allen J, Vallone D. Initiation with menthol cigarettes and youth smoking uptake. Addiction. 2013;108(1):171–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04045.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith SS, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Smoking cessation in smokers who smoke menthol and non‐menthol cigarettes. Addiction. 2014;109(12):2107–2117. doi: 10.1111/add.12661. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/add.12661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orzechowski W, Walker R. The Tax Burden on Tobacco, Historical Compilation Volume 49, 2014. Arlington, VA: Orzechowski & Walker Consulting; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galyan PE. Marketing Research Dept C/C Product Category Identification.(MRD#06e208) Winston-Salem, NC: RJ Reynolds; 1970. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jtw79d00. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dancer-Fitzgerald-Sample, Inc. Pilot study of CC concepts. Winston-Salem, NC: RJ Reynolds; 1970. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/twa59d00. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cullen J, Mowery P, Delnevo C, et al. Seven-year patterns in U.S. cigar use epidemiology among young adults aged 18–25 years: a focus on race/ethnicity and brand. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(10):1955–1962. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300209. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Government Accountability Office. Large disparities in rates for smoking products trigger significant market shifts to avoid higher taxes. Washington DC: GAO; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delnevo CD, Hrywna M. “A Whole ‘Nother Smoke” or a Cigarette in Disguise: How RJ Reynolds Reframed the Image of Little Cigars. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(8):1368–1375. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.101063. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2006.101063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Convenience Store News. CSP Category Management Handbook 2014: Tobacco, cigars. 2014 www.cspnet.com/sites/default/files/magazine-files/Tobacco_Cigars_CMH_2014.pdf.

- 22.Federal Trade Commission. Federal Trade Commission report to Congress on cigar sales and advertising and promotional expenditures for calendar years 1996 and 1997. Washington, DC: Federal Trade Commission; www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/1999-report-cigar-sales-advertising-promotion/1999cigarrepor.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index Frequently Asked Questions: 2016. www.bls.gov/cpi/cpifaq.htm#Question_10. Accessed July 26, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. DHHS. Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: a report of the Surgeon. General Atlanta, GA: U.S. DHHS, CDC, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012. p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farley SM, Johns M. New York City flavoured tobacco product sales ban evaluation. Tob Control. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052418. In press. Online February 12, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kasza KA, Hydland AJ, Bansal-Travers M, et al. Switching Between Menthol and Nonmenthol Cigarettes: Findings From the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey, U.S. Cohort. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(9):1255–1265. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu098. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntu098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tauras JA, Levy D, Chaloupka FJ, et al. Menthol and non‐menthol smoking: the impact of prices and smoke‐free air laws. Addiction. 2010;105(suppl 1):115–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03206.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tauras JA, Powell L, Chaloupka F, Ross H. The demand for smokeless tobacco among male high school students in the United States: the impact of taxes, prices, and policies. Appl Econ. 2008;39(1):31–41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00036840500427940. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dave D, Saffer H. Demand for smokeless tobacco: Role of advertising. J Health Econ. 2013;32(4):682–697. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.03.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]