Abstract

Introduction

Asthma prevalence is reportedly higher among U.S.-born relative to foreign-born Hispanics/Latinos. Little is known about rates of asthma onset before and after relocation to the U.S. in Latinos. Asthma rates were examined by U.S. residence and country/territory of origin.

Methods

In 2015–2016, age at first onset of asthma symptoms was analyzed, defined retrospectively from a cross-sectional survey in 2008–2011, in relation to birthplace and U.S. residence among 15,573 U.S.-dwelling participants (aged 18–76 years) in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos.

Results

Cumulative incidence of asthma through age 30 years ranged from 7.9% among Mexican background individuals to 29.4% among those of Puerto Rican background. Among those born outside the U.S. mainland, the adjusted hazard for asthma was 1.52-fold higher (95% CI=1.25. 1.85) after relocation versus before relocation to the U.S. mainland, with heterogeneity in this association by Hispanic/Latino background (p-interaction<0.0001). Among foreign-born Dominicans and Mexicans, rates of asthma were greater after relocation versus before relocation (adjusted hazard ratio [AHR] for after versus before relocation, 2.42, 95% CI=1.44, 4.05 among Dominicans; AHR=2.90, 95% CI=2.02, 4.16 among Mexicans). Puerto Ricans had modestly increased asthma onset associated with U.S. mainland residence (AHR=1.52, 95% CI=1.06, 2.17). No similar increase associated with U.S. residence was observed among Central/South American immigrants (AHR=0.94, 95% CI=0.53, 1.67). Asthma rates among Cuban immigrants were lower after relocation (AHR=0.45, 95% CI=0.24, 0.82).

Conclusions

The effect of relocation to the U.S. on asthma risk among Hispanics is not uniform across Hispanic/Latino groups.

INTRODUCTION

Asthma affects 25 million U.S. residents at an estimated cost of $56 billion annually in medical expenses, loss of school and work days, and early deaths.1,2 Asthma prevalence varies across and within countries,3,4 and markedly increased asthma rates have been observed in recent decades.2,5,6 Recent time trends may be attributed to increased urbanization and dissemination of a Western lifestyle.7

In the U.S., asthma disproportionally affects African Americans and Hispanics/Latinos living in urban areas.8–12 Among Hispanics/Latinos, asthma prevalence varies from 5.7% for Mexicans/Mexican Americans to 16.5% for Puerto Ricans.13 Besides national background, U.S. nativity, longer duration of U.S. residence, and having one or two U.S.-born parents have been previously reported as acculturation-related risk factors for asthma in foreign-born children.14 Asthma prevalence was also higher in foreign-born Latinos who relocated to the U.S. as children.15,16

Although asthma prevalence varies by Hispanic/Latino national background and age at immigration among immigrants from Latin America,15 little is known about the effect of U.S. residence on asthma risk in less-studied (non-Mexican) Hispanic/Latino groups. In addition, asthma rates before and after arrival in the U.S. have not been examined across different Hispanic groups. Whether the effects of U.S. nativity and relocation on asthma risk have shifted in recent decades among Hispanic/Latino groups in the U.S. has not been explored. Heterogeneity in these relationships might point to asthma risk factors that differ across Latin American countries. The majority of U.S. Hispanics/Latinos are foreign born, and by 2050, Hispanics/Latinos will represent nearly a third of the U.S. population, tripling in size from 2005.17 Therefore, understanding asthma risks related to specific Hispanic/Latino groups is important.

Both U.S. nativity and U.S. residence after relocation as risk factors for incident asthma were retrospectively analyzed in a large, diverse group of Hispanics/Latinos represented in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). In the context of this population-based study, the following outcomes were examined: (1) the effect of birthplace on asthma risk; and (2) among immigrants, whether asthma rates differed when comparing the time period before versus after relocating to the U.S. It was hypothesized that this effect would be modified by Hispanic/Latino country of origin, and that this contrast would be more pronounced among those born earlier in time (before 1970), as differences in asthma prevalence across nations have narrowed in recent decades.18

METHODS

Study Population

Hispanic/Latino adults aged 18–74 years living in four U.S. urban centers (Bronx, NY; Chicago, IL; Miami, FL; and San Diego, CA) were recruited for HCHS/SOL. Participants were recruited using a two-stage area probability sample design.19,20 In the first stage, Census block groups were randomly selected within sampling frames stratified by Hispanic/Latino concentration and SES. The second sampling stage randomly selected households from within the block groups. Eligible individuals were aged 18–74 years at recruitment and self-identified as Hispanic/Latino.

Within households determined during screening to have one or more members identifying as Hispanic/Latino, 41.7% were enrolled, representing 16,415 people from 9,872 households. Those who did not report a single national background (n=590) and those with incomplete data on asthma history (n=251) or birthplace (n=1) were excluded from the current analysis, yielding a sample of 15,573. This study was approved by the IRBs at all participating institutions and all participants gave written informed consent.

Measures

The HCHS/SOL baseline examination was conducted between 2008 and 2011 by bilingual interviewers in either English or Spanish. It contained a standardized respiratory questionnaire,21 including six questions on asthma and wheeze history (Appendix Table 1). To account for differential diagnostic biases, and based on reports that undiagnosed frequent wheeze may be especially relevant in Hispanic/Latino children,22 a comprehensive asthma definition was considered based on both prior asthma diagnosis and wheeze symptoms. Participants who reported ever having asthma were asked whether it was diagnosed by a health professional and at what age it started. Those who either reported a diagnosis by a health professional, or who reported two or more attacks of wheezing or whistling in the chest with shortness of breath during their lifetime were classified as having asthma. Age of asthma onset was defined as the earlier of reported onset of asthma or wheeze symptoms.

Participants were classified as U.S.-born if they reported being born within the 50 states or Washington, DC. All other participants, including those born in the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico, were considered “foreign-born” for the purposes of these analyses. Other known correlates of asthma included in models as adjustment variables were assessed through self-report, including sex, field center, educational attainment, smoking history, and second-hand exposure to tobacco smoke before age 13 years. Age at interview was considered in order to account for cohort effects and correct for telescoping biases.23,24

A time-dependent variable was created to assess the relative rate of asthma following relocation to the U.S. mainland, as compared with that among individuals at the same age who did not relocate (Appendix Figure 1). A time-dependent smoking variable was used to adjust for smoking initiation prior to asthma onset.

Statistical Analysis

Logistic regression models were constructed to compare risk of asthma through age 30 years among foreign-born and U.S.-born Hispanics. Age 30 years was chosen to minimize right censoring. Because some participants were as young as 18 years at the time of interview, parallel analyses were conducted where asthma cases were considered only through age 18 years. Central American and South American background individuals, with similarities on key asthma, smoking, and immigration variables, were combined to improve precision of effect estimates and due to low numbers of asthma cases occurring after relocation.

To examine whether asthma onset occurred before or after arrival in U.S., a time-to-event framework was established by reconstructing participants’ asthma histories from birth through age 30 years. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models with time-dependent migration status (three levels: U.S.-native [born in the U.S. mainland]; U.S. resident, before relocation; U.S. resident, after relocation) were constructed,25 with age as the time scale,26 to assess the effect of exposure to the U.S. environment on asthma risk. Individuals were considered at risk for asthma until age of first symptoms onset, age at interview, or their 31st birthday. The p-values derived from Wald F statistics compared the hazard for asthma among U.S. natives and U.S. residents after relocation versus individuals still living in their home country at the same age, while adjusting for potential confounders determined a priori. Proportional hazards were evaluated by visually examining variability over time in scaled Schoenfeld residuals for each independent variable using loess regression, as well as by computing Pearson correlations to test the linear association between scaled Schoenfeld residuals and time. Heterogeneities in the effect across Hispanic/Latino groups were examined using interaction terms. To explore heterogeneity by year of birth, separate models were constructed for each birth cohort (born before versus after 1970). Beta-estimates for the effect of U.S. residence derived from the two separate models were compared using a Z-test.27

Because individuals in the HCHS/SOL cohort were selected with unequal probabilities,19 all analyses were weighted to account for sampling probabilities. Sampling weights were non-response adjusted, trimmed, and calibrated by age, sex, and Hispanic/Latino group to the characteristics of each field center’s target population from the 2010 U.S. Census. Error terms account for the cluster stratified sample using Taylor series linearization methods. All tests of significance were two-sided at a significance level of 5%. Analyses were performed in 2015–2016 using SAS, version 9.3 and SUDAAN, release 11.0.1. Further descriptions of proportional hazards models and sensitivity analyses are available in the Appendix.

RESULTS

The median age of the participants at time of interview was 40 (interquartile range, 28–52; range, 18–76) years, a majority (78.7%) was foreign-born, and 18.5% reported a history of asthma, predominantly with onset by age 30 years (representing 1,904 asthma cases) (Table 1). Among those who relocated to the mainland U.S. at age ≤ 30 years, and therefore contributed person time after relocation to this analysis, median age at relocation was 19 (interquartile range, 14–24) years. Compared with other groups, Puerto Ricans were more likely to be U.S.-born and tended to relocate to the U.S. mainland at an earlier age and in earlier decades (Table 1 and Figure 1). Risk factors for asthma onset before age 30 years are displayed in Appendix Table 2. After adjusting for age at interview, there was more asthma reported among women, those with higher educational attainment, those residing in the Bronx and Miami, smokers, and those with a smoker in the home during childhood (all p<0.001).

Table 1.

Demographics, Asthma History, and Exposure to Tobacco Among U.S. Hispanics/Latinos From Diverse National Backgrounds, 2008–2011a

| Overall (n=15,573) | Dominic an (n=1,423) | Central/South American (n=2,760) | Cuban (n=2,322) | Mexican (n=6,433) | Puerto Rican (n=2,635) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Population characteristic | n | %/mean (95% CI) | %/mean (95% CI) | %/mean (95% CI) | %/mean (95% CI) | %/mean (95% CI) | %/mean (95% CI) |

| Age at interview, mean | 15,573 | 41.4 (40.9– 41.9) | 39.5 (38.1–40.8) | 40.9 (40.0–41.8) | 46.6 (45.5– 47.6) | 38.6 (37.9–39.3) | 43.0 (42.0–43.9) |

| Gender, % | |||||||

| Female | 9,358 | 52.2 (51.1–53.2) | 60.6 (56.8–64.3) | 53.6 (51.2–55.9) | 46.5 (44.4–48.6) | 53.9 (52.0–55.7) | 49.0 (46.2–51.8) |

| Male | 6,215 | 47.8 (46.8 –48.9) | 39.4 (35.7 –43.2) | 46.4 (44.1–48.8) | 53.5 (51.4 –55.6) | 46.2 (44.3 –48.1) | 51.0 (48.2 –53.8) |

| Highest education level, % | |||||||

| 5th grade or less | 2,112 | 9.0 (8.3–9.7) | 9.3 (7.7–11.3) | 12.0 (10.3–14.0) | 3.6 (3.0–4.5) | 15.4 (13.9–17.1) | 3.0 (2.3–3.8) |

| 6th grade – some HS | 3,845 | 23.8 (22.6–25.0) | 28.7 (25.6–32.1) | 20.3 (18.4–22.4) | 16.6 (14.8–18.5) | 22.9 (20.9–25.1) | 33.1 (30.0–36.4) |

| HS diploma or equivalent | 4,010 | 28.4 (27.3–29.6) | 22.4 (19.1–26.0) | 26.5 (24.5–28.6) | 32.2 (29.4–35.0) | 28.2 (26.5–30.1) | 28.4 (26.0–30.9) |

| Beyond HS | 5,581 | 38.8 (37.2–40.4) | 39.6 (36.2–43.1) | 41.2 (38.4–44.1) | 47.7 (44.7–50.7) | 33.5 (30.4–36.6) | 35.5 (32.4–38.7) |

| Study center, % | |||||||

| Bronx | 3,699 | 27.3 (24.6–30.2) | 94.3 (91.3–96.2) | 20.8 (17.0–25.2) | 1.4 (0.8–2.2) | 7.6 (5.7–10.0) | 71.5 (67.3–75.3) |

| Chicago | 4,003 | 16.3 (14.4–18.4) | 0.9 (0.5–1.4) | 17.0 (13.8–20.8) | 0.8 (0.3–2.1) | 25.5 (22.1–29.3) | 21.4 (18.0–25.3) |

| Miami | 3,914 | 29.7 (25.6–34.1) | 4.5 (2.7–7.5) | 58.0 (51.9–64.0) | 97.4 (95.8–98.3) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 4.5 (3.2–6.3) |

| San Diego | 3,957 | 26.7 (23.4–30.3) | 0.4 (0.1–1.5) | 4.2 (2.8–6.3) | 0.4 (0.1–1.4) | 65.8 (61.5–69.9) | 2.6 (1.5–4.5) |

| Place of birth, % | |||||||

| U.S.-born (within U.S. mainland) | 2,519 | 21.3 (19.8–22.9) | 14.4 (11.5–17.8) | 6.6 (5.1–8.3) | 9.6 (7.4–12.4) | 21.2 (19.3–23.1) | 50.8 (47.8–53.8) |

| Foreign (outside U.S. mainland) | 13,054 | 78.7 (77.1–80.2) | 85.6 (82.2–88.5) | 93.5 (91.7–94.9) | 90.4 (87.6–92.6) | 78.9 (76.9–80.7) | 49.2 (46.2–52.2) |

| Age at relocation,% among foreign-born | |||||||

| Relocated age 0–18 | 3,079 | 28.0 (26.5–29.6) | 29.3 (26.6–32.2) | 19.2 (17.2–21.3) | 16.7 (14.6–19.1) | 28.9 (26.9–30.9) | 61.5 (56.5–66.2) |

| Relocated age 19–30 | 4,685 | 36.3 (34.8–37.8) | 35.8 (32.3–39.4) | 40.1 (37.6–42.7) | 30.3 (27.8–32.9) | 40.2 (37.7–42.8) | 27.3 (23.5–31.5) |

| Relocated age >30 | 5,246 | 35.7 (33.7–37.7) | 34.9 (32.3–37.6) | 40.7 (38.4–43.0) | 53.0 (49.9–56.1) | 30.9 (28.3–33.7) | 11.2 (9.3–13.5) |

| Self-reported lifetime asthma, % | |||||||

| No | 12,861 | 81.5 (80.4–82.5) | 81.3 (78.3–83.9) | 87.9 (86.3–89.2) | 76.0 (73.8–78.1) | 89.3 (88.0–90.4) | 62.4 (59.4–65.3) |

| Yes, onset age 0–18 | 1,505 | 12.2 (11.3–13.2) | 10.3 (8.3–12.7) | 8.0 (6.9–9.4) | 20.2 (18.2–22.4) | 5.9 (5.0–7.0) | 24.1 (21.5–26.9) |

| Yes, onset age 19–30 | 399 | 2.5 (2.2–2.9) | 2.3 (1.5–3.4) | 1.6 (1.1–2.4) | 1.8 (1.2–2.5) | 2.0 (1.5–2.7) | 5.3 (4.4–6.5) |

| Yes, onset >30 years old | 808 | 3.8 (3.4–4.3) | 6.2 (4.9–7.8) | 2.5 (1.9–3.2) | 2.0 (1.4–2.7) | 2.8 (2.3–3.4) | 8.2 (6.5–10.3) |

| Smoking, % | |||||||

| Never | 9,577 | 62.0 (60.7–63.2) | 76.7 (73.2–79.9) | 68.8 (66.2–71.2) | 56.6 (53.6–59.6) | 63.8 (61.7–65.9) | 50.0 (47.0–53.0) |

| Initiated ≤18 | 4,119 | 27.3 (26.2–28.5) | 16.1 (13.0–19.7) | 21.0 (18.8–23.3) | 32.1 (29.5–34.9) | 25.0 (23.3–26.7) | 38.5 (35.6–41.5) |

| Initiated >18 | 1,855 | 10.7 (10.0–11.5) | 7.2 (5.8–9.0) | 10.3 (9.0–11.7) | 11.3 (9.9–12.8) | 11.2 (9.9–12.7) | 11.5 (9.9–13.2) |

| Among ever smokers, mean | |||||||

| Pack years | 5,743 | 14.0 (13.1–14.9) | 12.8 (11.2–14.5) | 11.1 (9.7–12.5) | 20.8 (19.3–22.3) | 9.0 (8.3–9.6) | 15.9 (15.0–16.9) |

| Age at initiation | 5,974 | 17.4 (17.2–17.6) | 17.7 (17.0–18.3) | 18.2 (17.7–18.6) | 16.9 (16.6–17.3) | 18.0 (17.6–18.4) | 16.7 (16.3–17.1) |

| Smoker in the home during childhood, % | |||||||

| No | 7,575 | 48.7 (47.2–50.2) | 49.4 (45.7–53.1) | 59.1 (56.8–61.3) | 32.0 (29.3–34.8) | 56.7 (54.7–58.7) | 42.3 (39.1–45.5) |

| Yes | 7,931 | 51.3 (49.8–52.8) | 50.6 (47.0–54.3) | 40.9 (38.7–43.2) | 68.0 (65.2–70.7) | 43.3 (41.3–45.3) | 57.8 (54.5–60.9) |

Least squared means derived from linear regression models were computed for continuous variables; and conditional marginal prevalences, representing age-adjusted prevalence estimates for the target population, were derived from multinomial logistic regression models. Point estimates and 95% CIs of age-adjusted proportions/means are reported for each Hispanic/Latino background within the target population; estimates adjusted for age differences between background groups; all reported estimates account for the complex sampling scheme used in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos.

HS, high school

Figure 1.

Age-specific trends in asthma incidence among U.S. Hispanic/Latino adults from diverse backgrounds, by birthplace and Hispanic/Latino background.

Notes: Values are adjusted for age at interview. Age-specific immigration trends (right axis) illustrate the density of immigration at each age as a percentage of all foreign-born individuals in the target population.

Through age 30 years, individuals of Mexican background had a lower estimated cumulative incidence of asthma than those of Puerto Rican background, regardless of birthplace (Figure 1). U.S.-born individuals of Mexican and Dominican background had consistently higher asthma incidence than their foreign-born counterparts. These findings were confirmed in multivariable logistic regression adjusted for known asthma risk factors (Table 2). Overall, U.S.-born individuals had 1.49 (95% CI=1.19, 1.85) and 1.37 (95% CI=1.12, 1.69) times the odds of reporting asthma by ages 18 and 30 years, respectively, when compared with foreign-born individuals. As compared with non-U.S. born, the probability of asthma was greater among those who were U.S.-born among Dominican and Mexican groups, but similar patterns relating birthplace with asthma were not found among other groups. Consistent group-specific effect estimates were observed when considering asthma cases through age 18 or 30 years (Table 2) (p- interaction<0.001).

Table 2.

Risk of Asthma by Age 30 Years Among U.S.- and Foreign-born Hispanics/Latinos by Background

| Foreign-born | U.S.-born | AOR for asthma: U.S.-born vs. foreign-born a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Hispanic/Latino background group | n | Cases | Risk (SE)b | n | Cases | Risk (SE)b | Birth through 18 years | Birth through 30 years |

| All groups combined | 12,853 | 1,329 | 12.8(0.5) | 2,491 | 554 | 21.1(1.2) | 1.49 (1.19–1.85) | 1.37 (1.12–1.69) |

| Mexican c | 5,269 | 231 | 6.3 (0.7) | 1,053 | 150 | 12.4 (1.5) | 2.67 (1.66–4.28) | 2.10 (1.40–3.13) |

| Dominican | 1,271 | 131 | 10.4 (1.0) | 127 | 39 | 22.3 (4.2) | 2.41 (1.40–4.17) | 2.48 (1.46–4.20) |

| Central/South American | 2,605 | 220 | 9.5 (0.7) | 120 | 18 | 11.8 (3.1) | 1.27 (0.67–2.39) | 1.25 (0.67–2.33) |

| Cuban | 2,185 | 427 | 22.2 (1.1) | 116 | 24 | 15.7 (3.2) | 0.59 (0.35–1.01) | 0.65 (0.39–1.08) |

| Puerto Rican | 1,523 | 320 | 28.3 (2.1) | 1,075 | 323 | 29.6 (2.0) | 1.11 (0.81–1.52) | 1.03 (0.78–1.35) |

Adjusted for age at interview, smoking before age 18, sex, age at interview, highest level of education, Hispanic/Latino national background, and childhood second-hand tobacco smoke exposure

Estimated probability of ever having asthma birth through age 30 years as determined by retrospective self-report after adjusting for age at interview; estimates account for complex sampling scheme of the HCHS/SOL

P-value for the interaction between U.S. born and Hispanic/Latino national background significant through age 18 and 30 (p<0.001)

HCHS/SOL, Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos

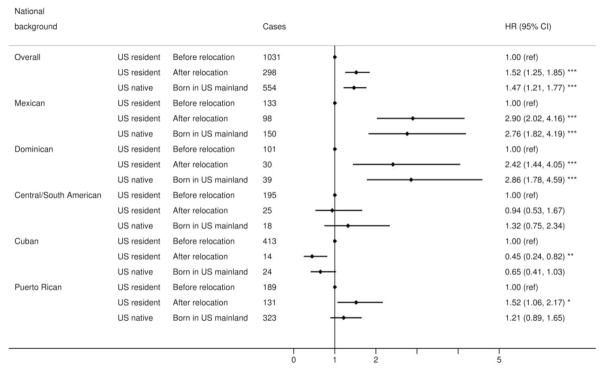

Next, the relative asthma risk associated with U.S. residence was examined through a time-to-event analysis that considered not just whether individuals were immigrants, but whether asthma onset occurred before or after their arrival in U.S. mainland (Figure 2). Compared with individuals at the same age who had not yet relocated, asthma risk was higher among those already relocated to the U.S.: the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for asthma was 1.52 (95% CI=1.25, 1.85). An interaction between Hispanic/Latino background and migration status in predicting asthma was observed (p-interaction<0.0001). In both Dominicans and Mexicans, among immigrants, the hazard of asthma onset was two to three times higher after relocation versus before relocation (Figure 2). Among Mexicans, similar patterns were observed at study sites in San Diego and Chicago (Appendix Figure 2). By contrast, there was little or no evidence for an adverse effect of U.S. residence on asthma risk in Central/South Americans. Asthma rates among Cuban immigrants were lower after relocation (adjusted HR=0.45, 95% CI=0.24, 0.82) (Figure 2). The HR for association with being born in the U.S. mainland in Puerto Ricans was not significant (HR=1.21, 95% CI=0.89, 1.65) (Figure 2) and the elevated HR among those who had come to the U.S. was relatively modest and of borderline statistical significance (HR=1.52, 95% CI=1.06, 2.17). Moreover, results among Puerto Ricans were not consistent across Bronx and Chicago field centers (Appendix Figure 2). Analyses of the time periods within 5 years since relocation and >5 years since relocation did not indicate increased rates of asthma associated with longer U.S. mainland residency (Appendix Table 3). There was no significant interaction between the year of birth and migration status in predicting asthma (Appendix, Appendix Figure 3, and Appendix Table 4).

Figure 2.

Asthma risk through age 30 among U.S. Hispanic/Latino adults, by background and U.S. nativity/residence, as assessed retrospectively in 2008–2011 (n=15,344).

Notes: Hazard ratios derived from Cox proportional hazards models adjusting for smoking status, age at interview, sex, educational attainment, second-hand exposure to tobacco smoke during childhood, and the complex survey design of HCHS/SOL; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. Heterogeneity in effect across Hispanic/Latino background groups significant at p<0.0001.

DISCUSSION

These results indicate that U.S. nativity and U.S. residence were not uniformly associated with asthma among various U.S. Hispanic/Latino groups. Although those born in the Dominican Republic and Mexico experienced an increase in asthma incidence after migration to the U.S., there was little evidence for a relationship between relocation to the U.S. mainland and increased asthma among Cubans or Central/South Americans. The results also suggested that among Mexican and Dominican immigrants to the U.S., asthma risk over time approaches that of their U.S.-born counterparts. This study builds upon previous analyses of U.S. birth,16,28–30 early age at immigration,15,16 and asthma risk by comparing rates of asthma before and after relocation to the U.S. among a diverse cohort of Hispanics/Latinos.

Several explanations have been proposed for an increased risk of asthma in immigrants. Exposure to more – “Westernized” environments has been implicated as a risk factor for asthma in prior studies of immigrants to Western nations,31 with several reports indicating that immigrants develop the allergic status of the host population.32–35 Similar observations have been reported in populations who abandon farm living and become more urbanized.36–39 This effect is apparent among different age groups, including older adults.34,35 Latinos who immigrated to the U.S. as children have higher prevalence of asthma.15 There was a consistent effect of U.S. residence on asthma risk among Mexican- and Dominican-born individuals even when analyses were restricted to age 6 years and older. It was also observed that although Puerto Ricans were more likely to relocate as children, the association between relocation to the U.S. and asthma in that group was not strong, suggesting that other factors play a role in asthma development, and that these findings cannot be explained by early age at immigration alone.

Findings of one previous study suggest that Puerto Rican children born in and residing in Puerto Rico had higher asthma prevalence than children of Puerto Rican descent residing in the Bronx.30 Recently, more than double the prevalence of current asthma was observed in surveys of Hispanic adults in U.S. mainland Puerto Ricans compared with residents in Puerto Rico.40 Although the present study examined a somewhat different outcome than these prior studies, the observation of significantly higher asthma rates after relocation to the Bronx among individuals born in Puerto Rico is consistent with the previous survey of adults, and warrants further study.

In contrast to other immigrant groups, the incidence of asthma among Cubans may have decreased (rather than increased) after moving to the U.S. This is contrary to the Westernization hypothesis. Similar observations from Cyprus and Turkey have been reported,41 in which transition to a more Westernized area resulted in reduced asthma. This finding was unexpected and may be related to higher levels of education, older age at immigration, earlier age at asthma onset, and high rates of smoking among Cubans, when compared with other background groups.

Studies suggest that individuals born more recently are more atopic owing to urbanization.33–35 In the present study, it was hypothesized that the asthma risk gradient between Latin American countries/territory and the U.S. would attenuate over time, reflecting increased Westernization of the Latin American countries during recent decades. However, the hazard for asthma attributed to U.S. residence in this analysis was similar for younger and older immigrant cohorts (born prior to and after 1970).

Other potential mechanisms for increased asthma rates with exposure to the U.S. mainland environment include diet and other lifestyle factors, breastfeeding, air pollution, viral infection, and use of antibiotics.47 With regard to heterogeneity in the effect of U.S. birth and residence on asthma rates, differences in home country environments likely play a role. For example, Puerto Rican background individuals had high asthma prevalence regardless of birthplace. Dominican background individuals born in the U.S. had asthma rates approaching their Puerto Rican counterparts, but much higher than foreign-born Dominicans, suggesting a causative environmental factor that is less common in the Dominican Republic. In addition, genetic predispositions to asthma vary in prevalence among national background groups,48 and are differentially activated in response to environmental exposures.49 This was exemplified by one study that found dramatically different asthma prevalence rates among Puerto Ricans and Dominicans living in the same building in Brooklyn, NY.50 Further work is needed to understand these mechanisms.

Limitations

A weakness of this study is the lack of information on urban versus rural residence prior to relocation to the U.S. mainland, which could have provided valuable insights into potential environmental mechanisms behind these findings. This study also lacked representation of rural-dwelling U.S. Hispanics who may have either lower or higher asthma rates than urban residents.42–45 In addition, given the retrospective nature of this study, there was no detailed information regarding intensity and cumulative burden of tobacco exposure at time of asthma onset. Changes in tobacco use following relocation may in part explain these findings.25,46

While adjusting for age at interview as a measure to account for differential recall of self-reported asthma and other covariates among older participants,24 residual uncontrolled bias may have affected presented results. This study was limited in precision of effect estimates by a low number of U.S.-born participants in some subgroups, namely those of Central/South American and Cuban background. Because there was no follow-up during early decades of life or recruitment of a comparison Latin American population that did not migrate to the U.S., this sample may be affected by misclassification or biases associated with the healthy migrant effect.51,52 By contrast, one recent study suggested that poorer self-rated health among Mexicans predicts higher likelihood of immigration to the U.S.,52 and another found no association between asthma during childhood and subsequent immigration from Mexico to the U.S.51 Nevertheless, if asthma during early childhood decreased the propensity to immigrate among specific population subgroups, this bias would have exaggerated the observed effect by preferentially excluding from the cohort individuals who developed asthma prior to migration. Lastly, HCHS/SOL employed a probability sampling design similar to other large population-based studies. Even though the response rate was imperfect, a widely accepted statistical adjustment protocol was followed to reduce potential bias due to study non-participation.19

This study has several strengths. Consistent effects of U.S. nativity and U.S. residence were observed across multiple analysis strategies, including sensitivity analyses where follow-up started at age 6 years rather than from birth, and under restricted asthma definitions.

Furthermore, although these results may have been biased since migrants in this sample by definition resided outside of the U.S. mainland during their earliest years of childhood when asthma is most commonly diagnosed, this potential bias should attenuate the effect of U.S. residence on asthma, leading to underestimation of place of residence effects in individuals of Mexican, Dominican, and Puerto Rican backgrounds.

CONCLUSIONS

The effect of relocation to the U.S. on asthma risk was not uniform across different groups of Hispanics/Latinos. These results may have implications in formulating preventive strategies specific to the U.S. Hispanic/Latino population. Further research is needed to uncover modifiable asthma risk factors that explain heterogeneities identified here.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and participants of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) for their important contributions. A complete list of staff and investigators has been provided by Sorlie et al. in Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:642-649 and is also available on the study website (www.cscc.unc.edu/hchs/).

The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos was carried out as a collaborative study supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) to the University of North Carolina (N01-HC65233), University of Miami (N01-HC65234), Albert Einstein College of Medicine (N01-HC65235), Northwestern University (N01-HC65236), and San Diego State University (N01-HC65237). The following Institutes/Centers/Offices contribute to the HCHS/SOL through a transfer of funds to NHLBI: the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institute of Deafness and Other Communications Disorders, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Office of Dietary Supplements. Dr. Jerschow is also supported by Clinical and Translational Science Award grant number 5KL2TR001071. Funding agencies played no role in the planning, design, or interpretation of analyses presented here.

Elina Jerschow, MD, MSc and Garrett Strizich, MPH contributed equally to this work.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Barnett SBL, Nurmagambetov TA. Costs of asthma in the United States: 2002–2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(1):145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asthma in the U.S. CDC vital signs. 2011 www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/asthma/

- 3.Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma , allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood : ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. 2006;368(9537):733–743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69283-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.To T, Stanojevic S, Moores G, et al. Global asthma prevalence in adults : findings from the cross-sectional world health survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):204. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Subbarao P, Mandhane PJ, Sears MR. Asthma: epidemiology, etiology and risk factors. CMAJ. 2009;181(9):E181–90. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080612. http://dx.doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.080612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moorman JE, Akinbami LJL, Bailey CMC, et al. National surveillance of asthma: United States, 2001–2010. Vital Heal Stat. 2012;3(35):1–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masoli M, Fabian D, Holt S, Beasley R. The global burden of asthma: Executive summary of the GINA Dissemination Committee Report. Allergy Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;59(5):469–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00526.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss K, Gergen P, Crain E. Inner-city asthma: the epidemiology of an emerging U.S. public health concern. Chest. 1992:362–367. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.362s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busse WW, Mitchell H. Addressing issues of asthma in inner-city children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(1):43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.021. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eggleston PA. The environment and asthma in U.S. inner cities. Chest. 2007;132(5 Suppl):782S–788S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1906. http://dx.doi.org/110.1378/chest.07-1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garg R, Karpati A, Leighton J, et al. Asthma Facts. New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aligne CA, Auinger P, Byrd RS, Weitzman M. Risk Factors for Pediatric Asthma: Contributions of Poverty , Race , and Urban Residence. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(3):873–877. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9908085. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9908085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Center for Health Statistics. Current Asthma Prevalence Percents. [Accessed January 1, 2016];2014 Natl Heal Interview Surv Data. 2016 www.cdc.gov/asthma/nhis/2014/table4-1.htm.

- 14.Silverberg J, Simpson E, Durkin HG, Joks R. Prevalence of Allergic Disease in Foreign-Born American Children. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(6):554–560. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.1319. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barr RG, Avilés-Santa L, Davis SM, et al. Pulmonary Disease and Age at Immigration among Hispanics: Results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(4):386–395. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1211OC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201506-1211OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eldeirawi KM, Persky VW. Associations of physician-diagnosed asthma with country of residence in the first year of life and other immigration-related factors: Chicago asthma school study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99(3):236–243. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60659-X. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60659-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Passel JS, Cohn DV. US Population Projections: 2005–2050. Washington, D.C: 2008. www.pewhispanic.org/files/reports/85.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pearce N, Aït-Khaled N, Beasley R, et al. Worldwide trends in the prevalence of asthma symptoms: phase III of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Thorax. 2007;62(9):758–766. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.070169. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2006.070169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lavange LM, Kalsbeek WD, Sorlie PD, et al. Sample design and cohort selection in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(8):642–649. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.05.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sorlie PD, Avilés-Santa LM, Wassertheil-Smoller S, et al. Design and implementation of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(8):629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.03.015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferris B. Epidemiology Standardization Project. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;118(6 Supp 2):1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yeatts K, Davis K, Sotir M, et al. Who gets diagnosed with asthma? Frequent wheeze among adolescents with and without a diagnosis of asthma. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5) doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.1046. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.5.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaskell G, Wright D, O’Muircheartaigh C. Telescoping of landmark events: Implications for survey research. Public Opin Q. 2000;64(1):77–89. doi: 10.1086/316761. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/316761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson EO, Schultz L. Forward telescoping bias in reported age of onset: an example from cigarette smoking. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2005;14(3):119–129. doi: 10.1002/mpr.2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mpr.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parrinello CM, Isasi CR, Xue X, et al. Risk of Cigarette Smoking Initiation During Adolescence Among U.S.-Born and Non – U.S.-Born Hispanics/Latinos: The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(6):1230–1236. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302155. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher LD, Lin DY. Time-dependent covariates in the Cox proportional-hazards regression model. Annu Rev Public Health. 1999;20(6):145–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.20.1.145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.20.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paternoster R, Brame R, Mazerolle P, Piquero A. Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology. 1998;36(4):859–866. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1998.tb01268.x. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holguin F, Mannino DM, Antó J, et al. Country of birth as a risk factor for asthma among Mexican Americans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(2):103–108. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-143OC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200402-143OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joseph S, Borrell L, Shapiro A. Self-reported lifetime asthma and nativity status in U.S. children and adolescents: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2004. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(2 suppl):125–139. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen RT, Canino GJ, Bird HR, et al. Area of residence, birthplace, and asthma in Puerto Rican children. Chest. 2007;131(5):1331–1338. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1917. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.06-1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rottem M, Szyper-Kravitz M, Shoenfeld Y. Atopy and asthma in migrants. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2005;136(2):198–204. doi: 10.1159/000083894. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000083894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalyoncu AF, Stålenheim G. Serum IgE levels and allergic spectra in immigrants to Sweden. Allergy. 1992;47(4 Pt 1):277–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1992.tb02053.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.1992.tb02053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laatikainen T, von Hertzen L, Koskinen J-P, et al. Allergy gap between Finnish and Russian Karelia on increase. Allergy. 2011;66(7):886–892. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02533.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ege MJ, von Mutius E. Atopy: a mirror of environmental changes? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(5):1354–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.01.031. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sozańska B, Błaszczyk M, Pearce N, Cullinan P. Atopy and allergic respiratory disease in rural Poland before and after accession to the European Union. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(5):1347–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.035. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.von Mutius E. Allergies, infections and the hygiene hypothesis--the epidemiological evidence. Immunobiology. 2007;212(6):433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2007.03.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.imbio.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Annus T, Riikjärv M-A, Rahu K, Björkstén B. Modest increase in seasonal allergic rhinitis and eczema over 8 years among Estonian schoolchildren. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2005;16(4):315–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2005.00276.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3038.2005.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krämer U, Oppermann H, Ranft U, et al. Differences in allergy trends between East and West Germany and possible explanations. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40(2):289–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03435.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holbreich M, Genuneit J, Weber J, et al. Amish children living in northern Indiana have a very low prevalence of allergic sensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(6):1671–1673. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.03.016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Félix SEB, Bailey CM, Zahran HS. Asthma prevalence among Hispanic adults in Puerto Rico and Hispanic adults of Puerto Rican descent in the United States - results from two national surveys. J Asthma. 2015;52(1):3–9. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2014.950427. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2014.950427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lamnisos D, Moustaki M, Kolokotroni O, et al. Prevalence of asthma and allergies in children from the Greek-Cypriot and Turkish-Cypriot communities in Cyprus: a bi-communal cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):585. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-585. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kausel L, Boneberger A, Calvo M, Radon K. Childhood asthma and allergies in urban, semiurban, and rural residential sectors in Chile. Sci World J. 2013:937935. doi: 10.1155/2013/937935. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/937935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Pesek RD, Vargas PA, Halterman JS, et al. A comparison of asthma prevalence and morbidity between rural and urban schoolchildren in Arkansas. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;104(2):125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2009.11.038. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2009.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valet RS, Gebretsadik T, Carroll KN, et al. High asthma prevalence and increased morbidity among rural children in a Medicaid cohort. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011;106(6):467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2011.02.013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turkeltaub P, Gergen P. Prevalence of upper and lower respiratory conditions in the U.S. population by social and environmental factors: data from the second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1976 to 1980 (NHANES II) Ann Allergy. 1991;67(2):147–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaplan RC, Bangdiwala SI, Barnhart JM, et al. Smoking among U.S. Hispanic/Latino adults: the Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(5):496–506. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.01.014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ding G, Ji R, Bao Y. Risk and Protective Factors for the Development of Childhood Asthma. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2015;16(2):133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2014.07.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.prrv.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pino-Yanes M, Thakur N, Gignoux CR, et al. Genetic ancestry influences asthma susceptibility and lung function among Latinos. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(1):228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.053. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choudhry S, Burchard EG, Borrell LN, et al. Ancestry-environment interactions and asthma risk among Puerto Ricans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(10):1088–1093. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-596OC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200605-596OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ledogar RJ, Penchaszadeh A, Garden CCI, Acosta LG. Asthma and Latino cultures: Different prevalence reported among groups sharing the same environment. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(6):929–935. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.6.929. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.90.6.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Breslau J, Borges G, Tancredi DJ, et al. Health selection among migrants from Mexico to the U.S.: childhood predictors of adult physical and mental health. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(3):361–370. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bostean G. Does selective migration explain the Hispanic paradox? A comparative analysis of Mexicans in the U.S. and Mexico. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013;15(3):624–635. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9646-y. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10903-012-9646-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.