Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to clarify the risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes in patients who conceive singletons after frozen embryo transfer (FET) during a hormone replacement cycle and their offspring.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was conducted in patients who conceived after FET, based on the Japanese-assisted reproductive technology registry for 2013. The perinatal outcomes in cases with live-born singletons achieved through natural ovulatory cycle FET (NC-FET) (n = 6287) or hormone replacement cycle FET (HRC-FET) (n = 10,235) were compared. Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to determine the potential confounding factors.

Results

The frequencies of macrosomia (1.1% in NC-FET and 1.4% in HRC-FET; P = 0.058) were comparable between patients after NC-FET and HRC-FET. The proportions of post-term delivery (0.2% in NC-FET and 1.3% in HRC-FET; P < 0.001) and Cesarean section (33.6% in NC-FET and 43.0% in HRC-FET; P < 0.001) were higher in patients after HRC-FET than in patients after NC-FET. The risks of post-term delivery (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 5.68, 95% confidence interval (CI) 3.30–9.80) and Cesarean section (AOR 1.64, 95% CI 1.52–1.76) were also higher in patients after HRC-FET than in patients after NC-FET.

Conclusions

Patients who conceived singletons after HRC-FET were at increased risk of post-term delivery and Cesarean section compared with those who conceived after NC-FET.

Keywords: Assisted reproductive technology, Hormone replacement cycle, Post-term delivery, Cesarean section

Introduction

Frozen-thawed embryo transfer (FET) during a hormone replacement cycle (HRC-FET) is a common treatment for women with fertility problems. Cryopreservation enables physicians to save the embryos generated through assisted reproductive technology (ART) and reduces the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome [1]. With the assistance of cryopreservation, we can also prevent multiple gestations by transferring fewer embryos [2]. In parallel, an HRC-FET helps patients with irregular cycles reduce the frequency of hospital visits, schedule the date of FET with ease, and decrease the cancelation rates of embryo transfer. For these reasons, many eumenorrheic women undergo HRC-FET as well [3].

Recently, some groups have reported associations between FET and adverse perinatal outcomes, such as abnormal placental formation [4, 5], hypertensive disorders [5, 6], post-term birth, and macrosomia [7]. While the underlying mechanism of these associations is unclear, endometrial injury associated with embryo transfer or altered epigenetic status due to embryo culture and cryopreservation potentially explain the pathophysiology [7–9]. In addition, hormonal disorders caused by the ART procedure or patient fertility problems may also influence pregnancy outcomes [10, 11]. Regarding the endometrial preparation for FET, previous studies have revealed that the rates of implantation, pregnancy, and live birth after HRC-FET are comparable to those after FET during natural ovulation cycles [12, 13]. However, little is known regarding the effect of HRC-FET on other maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Considering the recent expansion of ART with FET and association between FET and adverse perinatal events, identifying high-risk patients is essential for improving obstetric management. Based on analyses of Japanese national ART registry data, we herein report the differences in pregnancy outcomes, including timing and mode of delivery, between patients who underwent HRC-FET and FET during a natural ovulatory cycle (NC-FET).

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the registration and research subcommittee of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) Ethics Committee. We analyzed the data from the Japanese mandatory ART registry provided by the JSOG. The details of the registry have been previously described [5, 14]. In this study, we obtained the data on cases treated at 557 ART facilities in 2013. Since the use of donor gametes or embryos is not permitted in Japan, all of the transferred embryos were created from autologous oocytes and sperms obtained from couples.

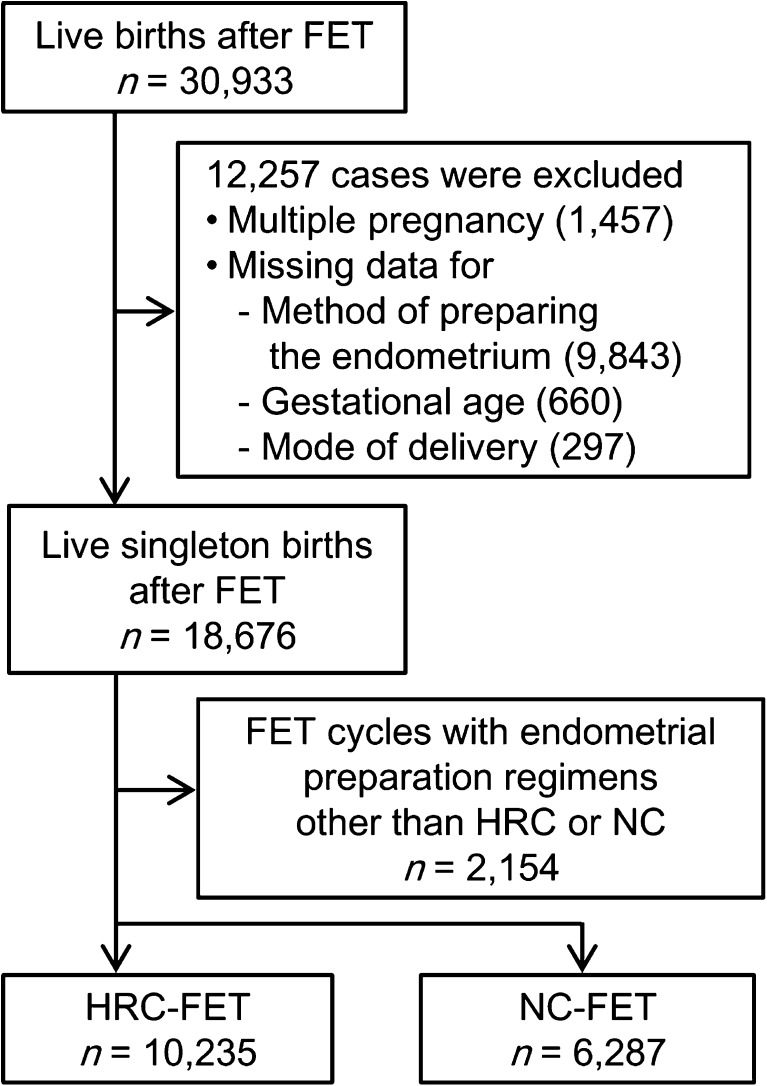

From the registry data, we analyzed women who underwent FET and achieved a live birth after 22 weeks of gestation (n = 30,933) (Fig. 1). Both vitrified and slow-frozen embryo cases were included. Given that multiple pregnancy is a potent factor influencing adverse obstetric and perinatal outcomes, cases of multiple pregnancy (n = 1457) were excluded from the analysis. In the database, procedures for endometrial preparation were recorded as one of the following: natural cycle, cycle with clomiphene citrate, cycle with human menopausal gonadotropin or follicular-stimulating hormone, HRC, and others. Incomplete clinical data (missing data for the method of endometrial preparation (n = 9843), gestational age at delivery (n = 660), and delivery mode (n = 297)) were excluded from the analysis. The remaining cases were categorized as follows: HRC-FET patients (HRC group, n = 10,235), NC-FET patients (NC group, n = 6287), and others (n = 2154).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram showing the distribution of the study populations

The characteristics and pregnancy outcomes of the HRC and NC groups were compared in a univariate analysis. Because the ART registry only provided the number of weeks for gestational age, we defined term, pre-term, and post-term deliveries as delivery between 37 and 41 weeks, less than 37 weeks, and over 41 weeks of gestation, respectively. The gestational ages of ART pregnancies were calculated according to the stage of the embryo and date of embryo transfer, following the clinical guidelines in Japan. According to the standard size and weight of newborns provided by the Japan Pediatric Society, we also calculated the proportion of neonates who were small for gestational age (SGA, below the 10th percentile of standard) or large for gestational age (LGA, above the 90th percentile of standard) [15]. The rate of stillbirth was also calculated based on the number of cases in the HRC and NC groups and the number of stillbirth cases after HRC-FET and NC-FET in the registry. Some specific clinical data including reason for HRC-FET, type of cryopreservation (slow freeze or vitrification) and type of Cesarean section (elective or non-elective) were not included in the registry and therefore could not be analyzed.

We stratified the cases according to the number of gestational weeks at delivery and examined the numbers of total deliveries, vaginal deliveries, and Cesarean sections, including both planned and emergency Cesarean sections. Using the Mann-Whitney U test, we compared the distributions of the gestational age at delivery for the HRC group, NC group, and all Japanese neonates registered with the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare in 2014. Using the chi-squared test, we also compared the rates of Cesarean sections in the HRC and NC groups for each gestational week. The risk factors for post-term delivery, Cesarean section, and SGA were analyzed in multivariate logistic regression analyses. The explanatory variables were HRC group vs. NC group, maternal age, blastocyst transfer vs. cleaved embryo transfer, assisted hatching vs. natural hatching, number of embryos transferred, offspring sex, and indications for ART treatment. All of the analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Significant differences were defined as P < 0.05.

Results

The characteristics and pregnancy outcomes of the NC and HRC groups are shown in Table 1. In the HRC group, the average maternal age was lower, more embryos were transferred, and early-cleaved embryos and assisted hatching were more often found than in the NC group. There were differences in the indication for ART between the two groups. In terms of the neonatal birth weight, the proportion of neonates weighing less than 2500 g was higher in the HRC group than in the NC group, but the proportions of neonates weighing 4000 g or more were comparable between the two groups. There were more SGA neonates in the HRC group than in the NC group, while the proportion of LGA neonates was similar between the two groups. While the frequency of pre-term delivery was comparable between the two groups, post-term delivery was more frequent in the HRC group than in the NC group. In addition, the frequency of Cesarean section was higher in the HRC group than in the NC group.

Table 1.

The characteristics and the pregnancy outcomes of the NC and HRC groups

| NC group n = 6287 |

HRC group n = 10,235 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age during the treatment cycle, yearsa | 36.5 ± 3.7 | 35.3 ± 4.0 | <0.001b |

| Number of embryos transferreda | 1.06 ± 0.25 | 1.16 ± 0.37 | <0.001b |

| Stage at embryo transfer, number/total number (%) | <0.001c | ||

| Blastocyst | 5520/6253 (88.3) | 8109/9952 (81.5) | |

| Cleavage | 733/6253 (11.7) | 1843/9952 (18.5) | |

| Assisted hatching, number/total number (%) | 3515/6287 (55.9) | 6815/10,235 (66.6) | <0.001c |

| Indication for assisted reproductive technology (%) | |||

| Tubal factor | 1175/6287 (18.7) | 1704/10,235 (16.6) | 0.001c |

| Endometriosis | 352/6287 (5.6) | 795/10,235 (7.8) | <0.001c |

| Antisperm antibody-positive | 24/6287 (0.4) | 78/10,235 (0.8) | 0.003c |

| Male factor | 1390/6287 (22.1) | 3165/10,235 (30.9) | <0.001c |

| Unexplained infertility | 3346/6287 (53.2) | 3921/10,235 (38.3) | <0.001c |

| Others | 553/6287 (8.8) | 2461/10,235 (24.0) | <0.001c |

| Mode of delivery, number/total number (%) | <0.001c | ||

| Vaginal delivery | 4173/6287 (66.4) | 5829/10,235 (57.0) | |

| Cesarean section | 2114/6287 (33.6) | 4406/10,235 (43.0) | |

| Sex of the neonate, number/total number (%) | 0.098c | ||

| Male | 3274/6269 (52.2) | 5283/10,158 (52.0) | |

| Female | 2995/6269 (47.8) | 4875/10,158 (48.0) | |

| Gestational age at birth, weeksa | 38.6 ± 1.8 | 38.8 ± 2.1 | <0.001b |

| Gestational age category, number/total number (%) | |||

| ≤36 weeks | 411/6287 (6.5) | 737/10,235 (7.2) | 0.103c |

| 37–41 weeks | 5861/6287 (93.2) | 9363/10,235 (91.5) | <0.001c |

| ≥42 weeks | 15/6287 (0.2) | 135/10,235 (1.3) | <0.001c |

| Birth weight, ga | 3046.0 ± 442.5 | 3059.5 ± 479.5 | 0.063d |

| Birth weight category, number/total number (%) | |||

| <2500 g | 499/6272 (8.0) | 922/10,209 (9.0) | 0.017c |

| ≥4000 g | 67/6272 (1.1) | 144/10,209 (1.4) | 0.058c |

| Small for gestational age, number/total number (%) | 323/6238 (5.2) | 609/10,002 (6.1) | 0.015c |

| Large for gestational age, number/total number (%) | 870/6238 (13.9) | 1456/10,002 (14.6) | 0.289c |

| Stillbirth | 30/6317 (0.5) | 48/10,283 (0.5) | 0.941c |

NC natural ovulatory cycle, HRC hormone replacement cycle

aThe data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation

bThe differences between the groups were evaluated by the Mann-Whitney U test

cThe differences between the groups were evaluated by the chi-squared test

dThe differences between the groups were evaluated by Student’s t test

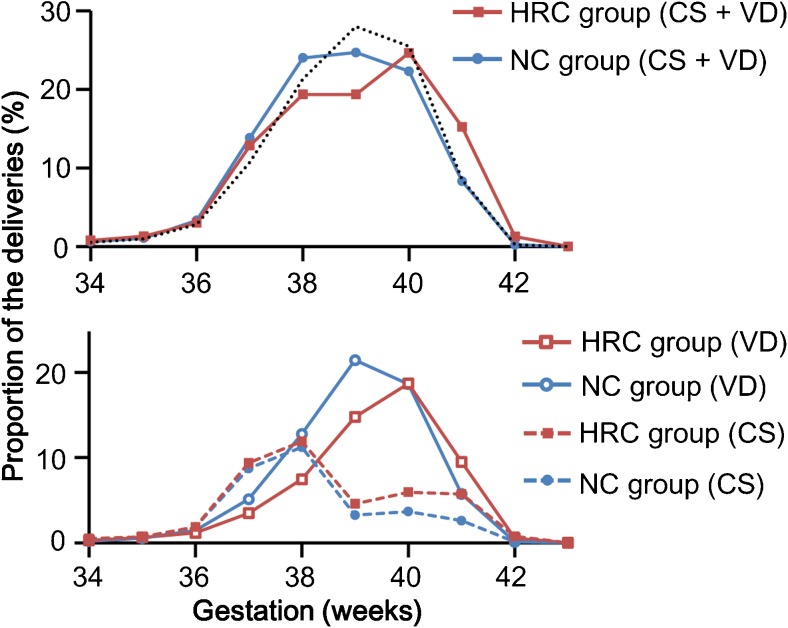

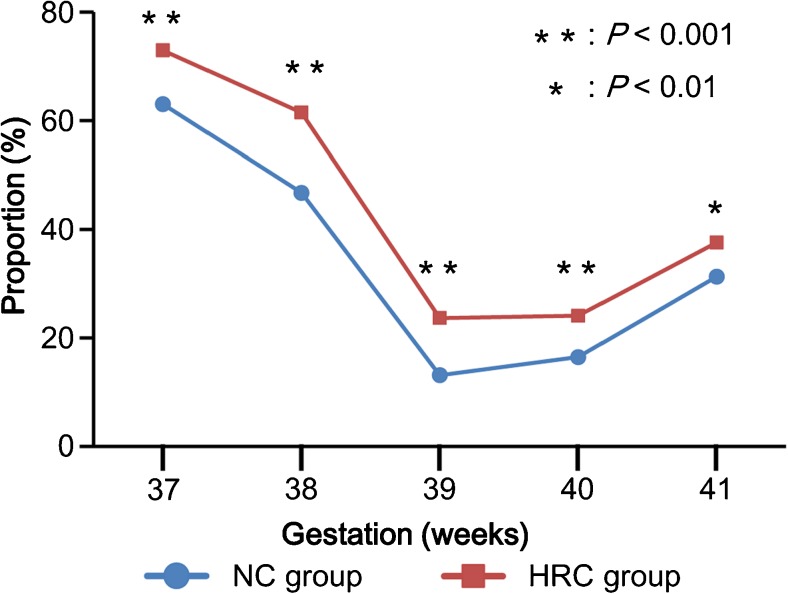

By analyzing the distribution of gestational weeks at delivery, we found that both total deliveries and vaginal deliveries in the HRC group were delayed compared with those in the NC group counterpart (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The proportions of Cesarean sections at 37 and 38 weeks of gestational age were comparable between the two groups; however, the proportion of Cesarean sections was higher in the HRC group than in the NC group at 39 weeks of gestation and later (Fig. 2). During term gestation, the rate of Cesarean sections was consistently higher in the HRC group than in the NC group (Fig. 3). A multiple logistic regression analysis showed that HRC-FET (vs. NC-FET) was a significant risk factor for both post-term delivery (adjusted odds ratio (AOR), 5.68; 95% confidence interval (CI), 3.30–9.80) and Cesarean section (AOR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.52–1.76) (Table 2). Regarding the risk of SGA, HRC-FET was not a significant risk factor after adjustment (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

The distributions of the delivery in the natural ovulatory cycle (NC) and hormone replacement cycle (HRC) groups. The data are expressed as the proportion of the deliveries at the respective gestational ages (expressed in weeks) to all of the deliveries after at least 22 weeks of gestation. The blue and red lines indicate the proportions of deliveries in the NC and HRC groups, respectively. The black dotted line indicates the distribution of the delivery of all Japanese neonates in 2014. In the upper graph, the distributions of the delivery in the three groups were significantly different (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.001). Likewise, in the lower graph, the distributions of vaginal delivery (VD) and Cesarean section (CS) were significantly different between the NC and HRC groups (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.001)

Fig. 3.

The rates of Cesarean sections at term for the natural ovulatory cycle (NC) and hormone replacement cycle (HRC) groups. The rates of Cesarean section were compared between the two groups at each week of gestation using the chi-squared test, and the statistically significant values are indicated with asterisks

Table 2.

The risk factors for post-term delivery, Cesarean section, and small for gestational age

| Perinatal outcome | COR (95% CI) | P value | AORa (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-term delivery | ||||

| Natural ovulatory cycle | Reference | Reference | ||

| Hormone replacement cycle | 5.59 (3.28–9.54) | <0.001 | 5.68 (3.30–9.80) | <0.001 |

| Cesarean section | ||||

| Natural ovulatory cycle | Reference | Reference | ||

| Hormone replacement cycle | 1.49 (1.40–1.59) | <0.001 | 1.64 (1.52–1.76) | <0.001 |

| Small for gestational age | ||||

| Natural ovulatory cycle | Reference | Reference | ||

| Hormone replacement cycle | 1.19 (1.03–1.36) | 0.015 | 1.14 (0.99–1.32) | 0.075 |

The odds ratios were obtained via a multiple logistic regression analysis

COR crude odds ratio, AOR adjusted odds ratio, CI confidence interval

aAdjusted for maternal age, embryo stage at transfer, neonatal sex, number of the transferred embryo, use of assisted hatching, and indications for the assisted reproductive technology

Discussion

We noted a higher risk of post-term delivery and Cesarean section in patients who conceived through HRC-FET than in patients who conceived through NC-FET. Our results provide new insights into the increase in adverse obstetric and perinatal outcomes in pregnancies after FET.

The common risk factors for prolonged gestation include previous post-term gestation, primiparity, male fetus, and genetic factors [16]. Recent studies have also described FET as an additional risk factor for prolonged gestation and macrosomia [7]. While these studies did not clarify the mechanism behind the observations, our results show a possible link between endometrial preparation and the timing of delivery. We demonstrated the association of HRC-FET with post-term delivery but not with macrosomia, suggesting that prolonged gestation and fetal overgrowth after FET may be caused by different factors. The analyses of the SGA and LGA groups also suggested that HRC had little effect on the overgrowth of the neonate. Nevertheless, we should be aware of the increase in prolonged gestation because several studies have demonstrated that late-term and post-term pregnancies are associated with an increased risk of perinatal mortality and morbidity other than macrosomia [17].

We detected an association between endometrial preparation using HR and the mode of delivery. Notably, the Cesarean section rate was consistently higher in the HRC group than in the NC group throughout term gestations, suggesting that either fertility problems in the patients who underwent HRC-FET or HRC itself is responsible for this increase. Because HRC is effective for women with irregular menses, the HRC group may include a greater proportion of patients with ovulation disorders whose indication for ART was described as “others” in Table 1, in comparison with the NC group [3]. For example, polycystic ovary syndrome, a major ovulation disorder, is closely related to ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome and is a reasonable indication for HRC-FET [18]. Indeed, these patients are at a high risk of adverse obstetric outcomes, including hypertensive disorders [11]. Likewise, the endometrial preparation using HR itself may be responsible for the adverse outcomes. We found that HRC remained a significant risk factor for post-term delivery and Cesarean section even after adjustment for fertility problems (Table 2). Since HRC requires medication, the condition might be less physiological than for those with NC [3]. This association between HRC and adverse perinatal outcomes must be thoroughly evaluated, as many eumenorrheic women favor and undergo this treatment.

Several limitations associated with the present study warrant mention. Because of the inherent limitation of the registry data, we were unable to adjust for potential confounding variables, such as parity, embryo quality, smoking status and alcohol intake, body mass index, and socioeconomic status. Temporal and geographic bias was also not adjusted, while many clinical factors and procedures potentially changed over time and place. In addition, the reason for the use of HRC-FET was not analyzable. However, our results clearly demonstrated the associations between adverse pregnancy outcomes and endometrial preparation by HRC, helping to identify those patients who potentially require additional care. Because one third of the cases were excluded due to missing data, we also need to be aware of the consequent bias. However, most of the registry data were available, and the fact that we were able to use the data from more than 16,000 patients in the Japanese ART registry, the largest nationwide registry in the world at present, is still worth noting.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that the patients who conceived singleton using HRC-FET are at higher risk of post-term delivery and Cesarean section than those who conceived through NC-FET. Notably, our results provide a possible explanation for the increased risk of obstetric and perinatal outcomes among patients who conceived after FET.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the Japanese fertility clinics for reporting the data and the JSOG for kindly providing the data.

Authors’ roles

K.S. and H.S. initiated and planned the study. K.S., K.M., K.Y., A.K., E.I., and M.M. analyzed the data. K.S., K.M., A.K., M.F., T.I., T.S., T.K., and H.S. interpreted the results. K.S. and K.M. drafted the manuscript. All of the authors critically reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the registration and research subcommittee of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) Ethics Committee.

Funding

This study was supported by a Grant from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (No. 15gk0110001h0103). The sponsor had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gera PS, Tatpati LL, Allemand MC, Wentworth MA, Coddington CC. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: steps to maximize success and minimize effect for assisted reproductive outcome. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:173–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takeshima K, Jwa SC, Saito H, Nakaza A, Kuwahara A, Ishihara O, et al. Impact of single embryo transfer policy on perinatal outcomes in fresh and frozen cycles-analysis of the Japanese Assisted Reproduction Technology registry between 2007 and 2012. Fertil Steril. 2016;105:337–46. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groenewoud ER, Cantineau AE, Kollen BJ, Macklon NS, Cohlen BJ. What is the optimal means of preparing the endometrium in frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19:458–70. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaser DJ, Melamed A, Bormann CL, Myers DE, Missmer SA, Walsh BW, et al. Cryopreserved embryo transfer is an independent risk factor for placenta accrete. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:1176–84. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishihara O, Araki R, Kuwahara A, Itakura A, Saito H, Adamson GD. Impact of frozen-thawed single-blastocyst transfer on maternal and neonatal outcome: an analysis of 277,042 single-embryo transfer cycles from 2008 to 2010 in Japan. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:128–33. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Opdahl S, Henningsen AA, Tiitinen A, Bergh C, Pinborg A, Romundstad PR, et al. Risk of hypertensive disorders in pregnancies following assisted reproductive technology: a cohort study from the CoNARTaS group. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:1724–31. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wennerholm UB, Henningsen AK, Romundstad LB, Bergh C, Pinborg A, Skjaerven R, et al. Perinatal outcomes of children born after frozen-thawed embryo transfer: a Nordic cohort study from the CoNARTaS group. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:2545–53. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nastri CO, Lensen SF, Gibreel A, Raine-Fenning N, Ferriani RA, Bhattacharya S, et al. Endometrial injury in women undergoing assisted reproductive techniques. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;3:CD009517. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009517.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jauniaux E, Jurkovic D. Placenta accreta: pathogenesis of a 20th century iatrogenic uterine disease. Placenta. 2012;33:244–51. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imudia AN, Awonuga AO, Doyle JO, Kaimal AJ, Wright DL, Toth TL, et al. Peak serum estradiol level during controlled ovarian hyperstimulation is associated with increased risk of small for gestational age and preeclampsia in singleton pregnancies after in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:1374–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roos N, Kieler H, Sahlin L, Ekman-Ordeberg G, Falconer H, Stephansson O. Risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2011;343:d6309. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Givens CR, Markun LC, Ryan IP, Chenette PE, Herbert CM, Schriock ED. Outcomes of natural cycles versus programmed cycles for 1677 frozen-thawed embryo transfers. Reprod Biomed Online. 2009;19:380–4. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng Y, Li Z, Xiong M, Luo T, Dong X, Huang B, et al. Hormonal replacement treatment improves clinical pregnancy in frozen-thawed embryos transfer cycles: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Transl Res. 2014;6:85–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakashima A, Araki R, Tani H, Ishihara O, Kuwahara A, Irahara M, et al. Implications of assisted reproductive technologies on term singleton birth weight: an analysis of 25,777 children in the national assisted reproduction registry of Japan. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:450–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itabashi K, Fujimura M, Kusuda S, Tamura M, Hayashi T, Takahashi T, et al. New standard of average size and weight of newborn in Japan. Jap J Pediat. 2010;114:1271–93. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Practice ACOG. Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetricians-gynecologists. Number 55, September 2004 (replaces practice pattern number 6, October 1997). Management of postterm pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:639–46. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200409000-00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice bulletin no. 146: management of late-term and postterm pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:390–6. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000452744.06088.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tummon I, Gavrilova-Jordan L, Allemand MC, Session D. Polycystic ovaries and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: a systematic review*. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84:611–6. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]