Abstract

Purpose

Maternal obesity has been shown to affect reproductive function and pregnancy outcomes following in vitro fertilization. More recently, studies have demonstrated lower live birth rates after single blastocyst transfer (SBT) in patients who are overweight or obese. However, the impact of morbid obesity on pregnancy outcomes after SBT has not been well elucidated. The present study aimed to determine whether morbid obesity has a detrimental impact on pregnancy outcomes after SBT in a North American population.

Methods

A retrospective, cohort study including 520 nulliparous and multiparous women undergoing top-quality SBT between August 2010 and March 2014 at a University Health Centre in North America was conducted. Primary outcomes included: miscarriage rate, clinical pregnancy rate, and live birth rate. Subjects were divided into different BMI categories (kg/m2), including <20, 20–24.9, 25.0–29.9, 30–40, and 40 or more.

Results

The miscarriage rate per pregnancy for each group, respectively, was 36, 64, 59, 61, and 50% (p = 0.16); the clinical pregnancy (per patient) rate per group was 36, 52, 38, 26, and 10% (p = 0.009); and the live birth rate (per patient) per group was 35, 50, 38, 26 and 10% (p = 0.03).

Conclusion

Morbid obesity is a strong and independent predictor of poor pregnancy outcomes in patients undergoing top-quality SBT.

Keywords: Single blastocyst transfer, Body mass index, Live birth rate, IVF, North America

Introduction

Obesity has become a global epidemic with an estimated 1.9 billion adults classified as overweight and over 600 million classified as obese [1]. Obesity is commonly defined by a person’s body mass index (BMI). According to the World Health Organization classification system, normal weight is defined as a BMI between 18.5 and 24.99 kg/m2, overweight as a BMI between 25 and 29.9 kg/m2, and obesity as a BMI of equal or greater than 30 kg/m2 [1]. In the USA alone, it is estimated that more than two thirds of adults are either overweight or obese [2]. Obesity has long been associated with an increased risk of heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes mellitus [3]. It has also been shown to affect reproductive function. For instance, obese women are at a higher risk of infertility, miscarriage, and pregnancy complications such as gestational diabetes and pre-eclampsia [4].

Moreover, there is a growing body of evidence which shows that obesity also affects pregnancy outcomes of assisted reproductive technologies (ART). Observational studies have linked obesity with higher doses of gonadotropin requirements, longer duration of stimulation, increase rates of cycle cancellation, and lower oocyte yield during in vitro fertilization (IVF) [5–7]. Pregnancy outcomes following IVF treatment also appear to be affected by maternal BMI. In a large meta-analysis of 47,967 IVF treatment cycles, obese women were shown to have a lower live birth rate (LBR) compared to women with a normal BMI [8]. These findings were validated by a recent, large retrospective study published by Provost et al. [9], which showed similar detrimental effects of BMI on pregnancy outcomes following IVF. However, the results of these studies are marred by the potential transfer of multiple embryos which have been previously shown to improve pregnancy rates per cycle [10].

In recent years, there has been mounting interest in the practice of elective single embryo transfer (eSET) as a means to reduce the rate of twins and higher-order multiple (HOM) gestations following IVF. Retrospective studies have demonstrated a significant reduction in the rate of twin pregnancies between patients undergoing elective single blastocyst transfer (SBT) compared to double blastocyst transfer (DBT) without compromising the overall pregnancy rate [11, 12]. Therefore, it is important to identify patient factors that may compromise pregnancy outcomes after SBT. Recent observational studies examining clinical factors that predict IVF outcomes following SBT have all identified BMI as an independent predictor of LBR and miscarriage rate (MR) [13–15]. It is important to note, however, that these studies examined European populations with a BMI ranging between 18.6 and 34.9, with a large proportion of patients under a BMI of 30 kg/m2. Given the higher rates of obesity and morbid obesity (BMI > 40 kg/m2) in North America, it is important to assess IVF outcomes following SBT in this patient population. The present study aims to examine the impact of BMI on pregnancy outcomes after SBT in obese and morbidly obese patients, in a North American population.

Methods

A retrospective study was conducted in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines examining 520 nulliparous and multiparous women who were undergoing their first embryo transfer between August 2010 and March 2014 at a University Health Centre in North America. Women less than 40 years of age with a single, top-quality autologous blastocyst transfer were included in the study. Exclusion criteria included: congenital uterine anomalies, endometrial polyps, intrauterine synechiae, adenomyosis, intra-cavitary fibroids, hydrosalpinges, donor embryo transfer, and women over the age of 40. All subjects had serum thyroid-stimulating hormone and prolactin levels within the normal range within 3 months of the embryo transfer. Subjects were included only once in the study. The first fresh embryo transfer was included unless a freeze all embryo cycle was performed to prevent ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, in which case the first frozen transfer was included for analysis.

Three protocols of ovarian hyperstimulation were used: (a) a microdose flare protocol using a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist on day 2–3 of the cycle after an oral contraceptive pill (OCP) induced withdrawal bleed and beginning stimulation with gonadotropins on the third day of the GnRH agonist; (b) a fixed, antagonist protocol with gonadotropin stimulation beginning on day 2–3 of the cycle and a GnRH antagonist started on the sixth day of stimulation; and (c) a mid-luteal, long agonist protocol with a GnRH agonist started in the mid-luteal phase and gonadotropin stimulation after 2 weeks of downregulation. Women were treated with a combination of recombinant FSH (r-FSH; Follitropin alpha, Merck Serono, MA, USA) and recombinant LH (rLH) (Lutropin alpha, Merck Serono, MA, USA) or rFSH (Folitropin beta, MERK IND, NJ USA) and human menopausal gonadotropins (hMG; Repronex, Ferring, QC, Canada). The ratio of FSH to LH was 2:1 to 3:1. An injection of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG; 10,000 IU; Ferring, QC, Canada) or 250 mcg recombinant hCG (Merck Serono, MA, USA) was administered when two or more follicles were ≥18 mm in diameter. Transvaginal ultrasound-guided oocyte retrieval was performed 36 h after hCG administration. Frozen embryo transfers were performed in an estrogen primed cycle (oral estradiol valerate and various producers), with 6 days of progesterone priming (crinone or endometrin) prior to embryo transfer and continued up to 10 weeks gestational age. Explanation of the stimulation protocols and medication used are available more in depth in previous publications by Dahan et al. [16].

Only those cycles where at least one top-quality blastocyst was available for transfer were included in this study, and only one blastocyst was transferred. Top-quality embryos for transfer included blastocysts with Gardner grade AA and BA. For further details on embryo grading, please refer to the article by Gardner and Schoolcraft, 1999 [17]. Ultrasound-guided, transcervical embryo transfer was performed using a Wallace embryo replacement catheter (Smiths Medical, USA) with a full urinary bladder. The embryos were placed 1.5 to 2.0 cm from the uterine fundus. Estradiol (Estrace, Actavis pharma USA) and progestin supplements (Endometrin, Ferring USA; Crinone, Actavis USA or intramuscular progesterone, Actavis USA) were started and continued until 12 weeks of pregnancy.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes included: miscarriage rate (MR), clinical pregnancy rate (CPR), and live birth rate (LBR). Miscarriage rate was defined as a pregnancy loss, prior to 20 weeks gestation, after the identification of a positive serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin level (>10 IU/L), measured at the time the embryos were 15–17 days of age. Women with a positive pregnancy test had a transvaginal ultrasound to confirm viability 4–5 weeks after embryo transfer. Clinical pregnancy was defined as the presence of a viable intrauterine pregnancy with a fetal heartbeat seen on transvaginal ultrasound. Live birth was defined as an infant born with signs of life at greater than 24 weeks of pregnancy.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 23.0, IBM Inc) with multivariate analysis and logistic regression to control for confounding effects and multiplicity. The following confounders were controlled for: female age, gravity, parity, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, basal serum FSH level (IU/L) and antral follicle count, duration of infertility, total gonadotropin dose, and stimulation protocol in all cases where analysis was performed, unless indicated. These variables were selected based on their well-established effects on IVF outcomes. The following variables were self-reported by patients within 2 months of initiating care: smoking status, gravity, parity, height, and duration of infertility. In order to calculate a patient’s BMI, their weight was measured on a standard hospital scale within 2 months of initiating care. Age was calculated from a patient’s birth date to the start of their treatment. Antral follicle count and basal serum FSH levels (IU/L) were determined between cycle day 2 and 5. Measurements of antral follicle count were performed with transvaginal ultrasound in the menstrual cycle prior to IVF treatment. The ultrasounds were performed in a uniform manner by ultrasound technicians using a Voluson E8 ultrasound machine and Voluson transvaginal ultrasound probe (General Electric Corporation, USA), with women in the dorsal lithotomy position and empty bladders. The FSH assay used was the Access assay (Beckman Coulter, Canada). The lower limit of detection was 0.2 IU/L while the upper limit was 200 IU/L. Intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were less than 6% in all cases and were assayed in house at 6.8, 23.5, and 45.0 IU/L. There was no data missing from the database.

All continuous data were checked for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov–Smirnoff test. All continuous variables were normally distributed. Correlations were done with partial correlations to control for confounding effects of all variables listed. Demographics were compared by one-way analysis of variance, without controlling for confounding effects, or chi-squared tests. Data is presented as mean ± standard deviation. Two-sided p values ≤0.05 were accepted as significant, unless stated otherwise.

Results

Five hundred and twenty women underwent single, top-quality blastocyst transfer. Four hundred fifty women were nulliparous and 70 had a previous full-term pregnancy. All women were less than 40 years of age and were included only once in the database. Only their first embryo transfer was included. The mean female age of this study was 32.9 ± 3.4 years (range 22–39 years). The mean BMI was 24.8 ± 6.2 kg/m2 (17.0 to 57.0 kg/m2) [refer to Table 1]. Diagnosis included male factor infertility (40%), anovulation (and previous treatment failure with ovulation induction and insemination) (12%), tubal blockage (12%), endometriosis (6%), unexplained (19%), and other. Fifteen percent of cycles were frozen transfers and 85% were fresh transfers.

Table 1.

Demographics based on BMI grouping

| BMI grouping (kg/m2) | <20 | 20–24.9 | 25–29.9 | 30–39.9 | ≥40 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 51 | N = 294 | N = 64 | N = 58 | N = 54 | ||

| Age (years) | 33.2 ± 3.2 | 32.9 ± 3.5 | 32.7 ± 3.3 | 32.8 ± 3.8 | 32.9 ± 1.9 | 0.77 |

| Previous pregnancies | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.8 ± 2.3 | 1.1 ± 1.6 | 0.8 ± 1.2 | 0.5 ± 0.7 | 0.64 |

| Full-term deliveries | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 1.8 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 0.4 ± 0.6 | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 0.90 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 17.7 ± 3.8 | 23.6 ± 1.5 | 26.8 ± 1.4 | 33.9 ± 2.5 | 45.4 ± 6.1 | 0.0001 |

| Duration of infertility (years) | 3.4 ± 2.5 | 3.8 ± 3.5 | 4.0 ± 2.8 | 3.1 ± 2.1 | 4.2 ± 1.9 | 0.76 |

| Day 3 serum FSH (IU/L) | 8.5 ± 2.6 | 8.0 ± 3.8 | 7.2 ± 2.1 | 8.2 ± 9.4 | 5.9 ± 2.3 | 0.27 |

| AFC | 18 ± 10 | 18 ± 12 | 17 ± 10 | 22 ± 15 | 13 ± 9 | 0.17 |

| Total FSH dose (IU) | 1836 ± 1430 | 1706 ± 1330 | 2015 ± 1061 | 2112 ± 1262 | 2620 ± 1969 | 0.05 |

| Total LH dose (IU) | 772 ± 1216 | 729 ± 1087 | 650 ± 998 | 467 ± 903 | 720 ± 770 | 0.66 |

| MR | 0.41 | |||||

| CPR | 19 | 153 | 24 | 15 | 5 | 0.0001 |

| LBR | 18 | 147 | 24 | 15 | 5 | 0.0001 |

BMI body mass index, FSH follicle-stimulating hormone, LH luteinizing hormone, AFC antral follicle count, MR miscarriage rate, CPR clinical pregnancy rate, LBR live birth rate

Overall, the MR, CPR, and LBR were 61, 42, and 41%, respectively. It can be noted that among women less than 40 years of age with a top-quality blastocyst transferred, BMI was the only significant predictor of pregnancy outcomes, with the exception of a previous delivery of a term baby which also predicted live birth. Analysis was performed with stepwise logistic regression controlling for all listed confounders and multiplicity.

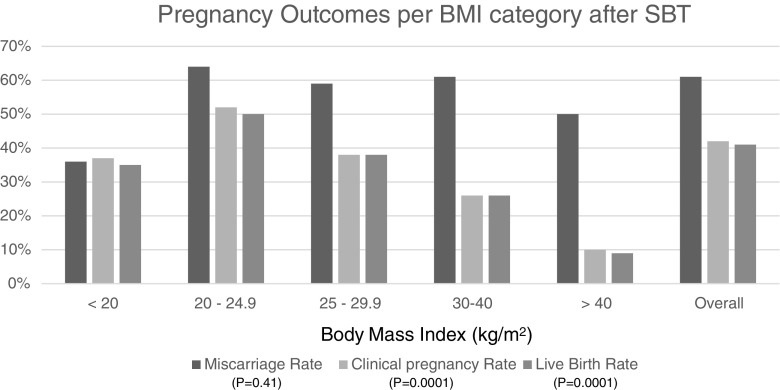

To further evaluate the effect of BMI on MR, CPR, and LBR, the groups were divided into different BMI categories, including: <20, 20–24.9, 25.0–29.9, 30–40, and 40 or more. The MR for each group, respectively, was 36, 64, 59, 61, and 50% (p = 0.16); the CPR per group was 37, 52, 38, 26, and 10% (p = 0.0001); and the LBR per group was 35, 50, 38, 26, and 9% (p = 0.0001) [chi-squared analysis—refer to Fig. 1]. Controlling for confounders was not performed for this analysis, since BMI was already demonstrated to be a significant parameter, when controlling for other confounders, and would have given the same results as in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Pregnancy outcomes per BMI category after single blastocyst transfer

The demographics for these groups are listed in Table 1. Statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA. All parameters were similar except BMI (data stratified by increasing BMI) and FSH dose required for stimulation which increased in parallel to BMI, as anticipated.

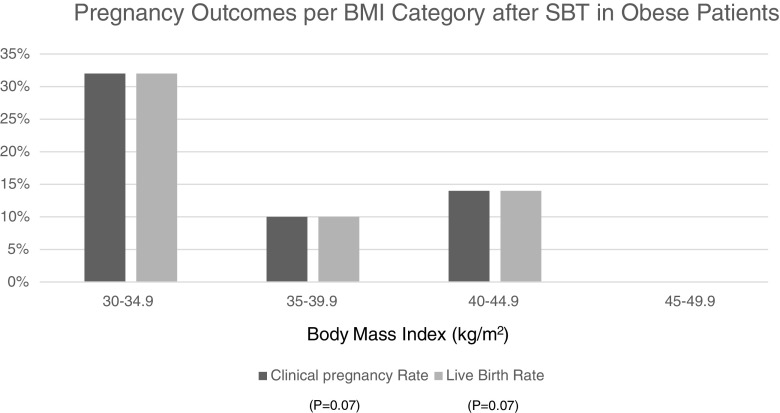

To further evaluate the role of obesity and morbid obesity, women were classified based on BMI of 30–34.9, 35–39.9, 40–44.9, and 45–49.9 kg/m2. The CPR and LBR rates are shown in Fig. 2. A strong correlation between BMI and pregnancy outcomes was demonstrated among women within these BMI categories. The CPR was 32, 10, 14, and 0% (p = 0.07, correlation); and the LBR was 32, 10, 14, and 0% (p = 0.07, correlation). Partial correlations were performed which controlled for all confounding variables listed in the statistics section of the paper.

Fig. 2.

Pregnancy outcomes per BMI category after single blastocyst transfer in obese patients

Given the high rate of obese patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), and a possible effect of the disease on oocyte function, we performed a post hoc analysis excluding women with PCOS. PCOS was diagnosed if patients met two out of three of the following criteria: (a) clinical or biochemical evidence of hyperandrogenism, (b) menstrual irregularity (oligo or amenorrhea), and/or polycystic ovarian morphology (PCOM) on ultrasound. In the case of PCOS, ovarian or adrenal neoplasia and non-classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia were ruled out by non-tumor levels of serum DHEAS, total testosterone, and an early morning, fasting 17-hydroxy-progesterone less than 2 ng/dl, respectively. PCOM was defined as one ovary with a follicle count of 12 or more between 2 and 8 mm in diameter, as viewed by transvaginal ultrasound performed on days 2 to 5 of a spontaneous or progesterone-induced menses. The analysis included logistic regression, controlling for the same confounders listed in the statistics section and for multiple testing (multiplicity). Three hundred and seventy-three women were included in the analysis of women without PCOS. Significant predictors of live birth were: total FSH used for stimulation (p = 0.04), previous full-term deliveries (p = 0.0001), and BMI (p = 0.014). There was a strong trend between antral follicle count and live birth in this latter group; however, this was not statisically significant (p = 0.053).

Discussion

In the present study, BMI was a predictor of clinical pregnancy (p = 0.004) and live birth (p = 0.023) after SBT, independent of female age, duration of infertility, maximum basal FSH levels (IU/L), antral follicle count, total FSH dose, gravity, and smoking. A post hoc analysis also demonstrated that the effect of BMI may be irrespective of a diagnosis of PCOS, although further studies are necessary to confirm these findings. BMI was not a predictor of miscarriage rate (p = 0.16). The CPR and LBR in women with a BMI of 40 or greater was over 50% less than that of women of BMI of 30–39.9 kg/m2. It should also be noted that the LBR of women with a BMI of 20–24.9 kg/m2 was five times greater than those with a BMI over 40 kg/m2. In fact, the impact of obesity on CPR and LBR after SBT seems to occur in patients with a BMI equal or greater than 35 kg/m2 [refer to Fig. 2]. Subjects with a BMI of 30–34.9 kg/m2 had similar outcomes to the overweight group (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2). Therefore, patients with a BMI equal or greater than 35 kg/m2 should be encouraged to lose weight before undergoing IVF treatment or, alternatively, be considered for DBT.

Several studies examining the effect of BMI on pregnancy outcomes following IVF have been published previously. Most recently, Provost et al. [9] published a large analysis examining the effects of BMI on IVF outcomes in a North American population. Like previous studies examining the effects of BMI on IVF outcomes, the results of this study appear to be influenced by the transfer of multiple embryos. This may—in part—explain the much lower LBR in patients with a BMI > 40 kg/m2 undergoing SBT in our study. Ideally, weight loss followed by SBT should be offered to minimize multiple pregnancy rates, especially given that multiple pregnancies in the morbidly obese are likely to magnify risk of complications. The authors also compared pregnancy outcomes among different BMI categories in women with only a diagnosis of “ovulation disorders/polycystic ovaries” and found that the correlation was weaker compare to the analysis including all participants. However, this may be attributed to a much smaller sample size (N = 16,222 versus N = 239,127) and may be biased by the inclusion of other diagnoses other than PCOS such as hypothalamic amenorrhea. Lastly, the authors acknowledged that they were not able to control multiple cycles by the same patient.

The effect of BMI on pregnancy outcomes does not appear to be different in patients who have a fresh or frozen–thawed transfer. In the study by Rittenberg et al. [13], the authors examined effects of BMI on miscarriage rates following an SBT in 413 women after controlling for confounders. The authors found that women with a BMI of >25 had a significantly increased risk of clinical miscarriage before 23 weeks gestation (adjusted OR = 2.7, 95% CI 1.5–4.9, P = 0.001). These findings were the same whether patients had a fresh or frozen–thawed transfer [13]. Similar findings have been demonstrated in other studies [16]. Similar findings have been demonstrated elsewhere [16]. It is important to note, however, that there were no patients with a BMI > 35 kg/m2 treated in this clinic during the study period.

Several studies have been published examining the effects of maternal BMI on IVF outcomes in patients specifically undergoing SBT [8, 14, 15]. All studies were based out of countries in Europe including the United Kingdom [8] and France [14, 15]. As previously noted, the majority of patients within these studies fell under a BMI of 30 kg/m2. Moreover, the consistently, lower pregnancy rates of European IVF centers, when compared to its North American counterparts, may also be a confounder when comparing studies in different regions [18]. Lastly, maternal BMI appears to affect pregnancy outcomes following SET even at the cleavage stage. Sifer et al. [15] retrospectively examined 409 eSET on day 2/3 and found BMI to be the only clinical criteria statistically associated with LBR.

To our best knowledge, this is the only study published in the literature examining the effects of different BMI categories, including morbid obesity (BMI greater than 40) on CPR and LBR following SBT on a large, North American population. These findings cannot be accounted for by a previous successful IVF-ET given that only the first embryo transfer was included and patients were only included once in the database. Moreover, as previously noted, our post hoc analysis also demonstrated that the effect of BMI may be irrespective of a diagnosis of PCOS.

It is important to note that there is a large subset of patients that are not represented within this study which are obese patients undergoing IVF who did not have a blastocyst or supernumerary blastocyst(s) available for transfer. We recognize that pregnancy outcomes published in this study may significantly undermine the overall risk of obesity and morbid obesity on pregnancy outcomes following IVF; however, our goal was specifically to evaluate the subset of patients within this population that do have excellent quality blastocyst(s) available to transfer and who may benefit from either weight loss prior to an embryo transfer or a double embryo transfer to improve their outcomes.

Our study has several limitations, including its retrospective nature and the resultant risk of undetected selection bias. It should be noted that single blastocyst transfer is mandated by law in a first cycle in all women under 40 years of age in this center. This SBT practice protected against biases due to patients with morbid obesity being offered more embryos to transfer and therefore not being included in this study. However, this study was skewed towards nulliparous women which may favor the effect of BMI, since women with a previous pregnancy may conceive with greater ease. By including each patient only once, we attempted to minimize this effect. It is possible that the inclusion of male factor infertility may have affected results. Infertility diagnosis can affect the development of embryos and their competence, particularly as measured by blastocyst development. The effect of male factor infertility on outcomes should have been minimized by selecting only cases with excellent quality blastocysts to transfer. Lastly, it is possible that poor pregnancy outcomes in women with a higher BMI may be partially attributed to a difficult embryo transfer under ultrasound guidance.

The detrimental effects of morbid obesity on pregnancy outcomes after SBT are not well understood but several hypotheses have been raised. There have been a number of studies looking at the impact of obesity on oocyte or embryo quality with mixed results; some suggesting there is a detrimental effect on the oocyte/embryo [19–21] while others suggest there is no difference compared to women of normal BMI [6, 22]. However, all patients in this study received ideal quality blastocyst transfer. In a study by Bellver et al. [23], authors examined IVF outcomes in donor egg recipients and found a higher risk of miscarriage in obese patients compared to controls, independent of the donor’s BMI. These findings would suggest that the impact of obesity on IVF outcomes may be related to an issue with endometrial receptivity. There have been several theories proposed to explain how obesity can affect endometrial receptivity. One theory is that patients with an elevated BMI are more likely to have insulin resistance, which in turn, has been shown to increase the risk of spontaneous abortion after ART [24]. Another theory that has been suggested is the role of leptin in obese patients. Leptin has been shown to be expressed in endometrial cells as well as within blastocysts [25]. In fact, leptin concentrations appear to differ when a competent blastocyst is co-cultured with endometrial cells, as oppose to an arrested blastocyst [25]. These findinds suggest that this molecule may play a key role in the communication between embryo and endometrium during the early implantation phase [25]. Finally, as noted previously, obese patients have been shown to require higher doses of gonadotropins and longer periods of controlled ovarian stimulation (COH). In turn, this may lead to an altered endometrial receptivity in patients undergoing autologous, fresh embryo transfer. The authors from Luke et al. [26] were able to demonstrate this premise by looking at outcomes in patients with increasing BMI undergoing autologous fresh transfers compared to donor cycles. Interestingly, the detrimental effect found on pregnancy rates was not seen when they compared autologous, frozen–thawed cycles to donor cycles. These findings are likely attributed to similarities in endometrial “priming” between fresh donor cycles and autologous, frozen–thawed cycles.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that maternal BMI is an independent predictor of CPR and LBR in North American women undergoing top-quality SBT. This effect may be decreased when multiple embryos are transferred; however, this may lead to an increased risk of maternal and fetal complications during the pregnancy. Patients should be counselled regarding the effects of BMI on pregnancy outcomes following SBT, especially when BMI is greater than 35 kg/m2. Further, randomized prospective trials are needed to determine the relationship between BMI and pregnancy outcomes following SBT. These studies should include PCOS with or without evidence of hyperinsulinemia within their analysis. The ideal treatment algorithm likely involves weight loss to a BMI of less than 35 kg/m2 followed by SBT rather than the transfer of multiple embryos. This may help to overcome the detrimental effects of morbid obesity on pregnancy outcomes following SBT without significantly increasing the risk of complications during pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

Contributions

MR: Participated in data extraction and manuscript drafting and revision

TS: Participated in the revision of the manuscript

SA: Participated in the revision of the manuscript

MD: Participated in the data extraction and manuscript drafting and revision

Abbreviations

- SBT

Single blastocyst transfer

- PR

Pregnancy rate

- CPR

Clinical pregnancy rate

- LBR

Live birth rate

- PCOM

Polycystic ovarian morphology

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest..

Contributor Information

Miguel Russo, Email: miguel.russo@medportal.ca.

Senem Ates, Email: atessenem@hotmail.com.

Talya Shaulov, Email: talya07@gmail.com.

Michael H. Dahan, Email: dahanhaim@hotmail.com

References

- 1.WHO. Obesity and overweight. Fact sheet 311; Updated January 2015:1–7. 2015. Retrieved December 6, 2015 from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/.

- 2.NIH National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Overweight and obesity statistics. WIN Weight-Control Information Network, 04(4158), 6. 2010. Retrieved December 6, 2015 from http://win.niddk.nih.gov/publications/PDFs/stat904z.pdf.

- 3.National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the evidence report. 1998. 98–4083. Retrieved on December 6, 2015 from http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/archive/clinical-guidelines-obesity-adults-evidence-report.

- 4.The Practice Committee of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine Obesity and reproduction: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(5):1116–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fedorcsak P, Dale PO, Storeng R, Ertzeid G, Bjercke S, Oldereid N, et al. Impact of overweight and underweight on assisted reproduction treatment. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2523–2528. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang JX, Davies M, Norman RJ. Body mass and probability of pregnancy during assisted reproduction treatment: retrospective study. BMJ. 2000;321:1320–1321. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7272.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robker RL. Evidence that obesity alters the quality of oocytes and embryos. Pathophysiology. 2008;15:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rittenberg V, Seshadri S, Sunkara S, Sobaleva S, Oteng-Ntim, El-Toukhy T. Effect of body mass index on IVF treatment outcome: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Med Online. 2011;23(4):421–439. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Provost MP, Acharya KS, Acharya CR, Yeh JS, Steward RG, Eaton JL, et al. Pregnancy outcomes decline with increasing body mass index: analysis of 239,127 fresh autologous in vitro fertilization cycles from the 2008-2010 Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology registry. Fertil Steril. 2015; 105:663–669 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Thurin A, Hausken J, Hillensjö T, Jablonowska B, Pinborg A, Strandell A, et al. Elective single-embryo transfer versus double-embryo transfer in in vitro fertilization. 2009;2392–402. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa041032. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Stillman RJ, Richter KS, Banks NK, Graham JR. Elective single embryo transfer: a 6-year progressive implementation of 784 single blastocyst transfers and the influence of payment method on patient choice. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1895–1906. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mullin CM, Fino ME, Talebian S, Krey LC, Licciardi F, Grifo J. Comparison of pregnancy outcomes in elective single blastocyst transfer versus double blastocyst transfer stratified by age. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:1837–1843. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rittenberg V, Sobaleva S, Ahmad A, Oteng-Ntim E, Bolton V, Khalaf Y, et al. Influence of BMI on risk of miscarriage after single blastocyst transfer. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(10):2642–2650. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dessolle L, Fréour T, Ravel C, Jean M, Colombel A, Daraï E, et al. Predictive factors of healthy term birth after single blastocyst transfer. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(5):1220–1226. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sifer C, Herbemont C, Adda-Herzog E, Sermondade N, Dupont C, Cedrin-Durnerin I, et al. Clinical predictive criteria associated with live birth following elective single embryo transfer. EJOG. 2014;181:229–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahan MH, Agdi M, Shehata F, Son W, Tan SL. A comparison of outcomes from in vitro fertilization cycles stimulated with either recombinant luteinizing hormone (LH) or human chorionic gonadotropin acting as an LH analogue delivered as human menopausal gonadotropins, in subjects with good or poor ovarian reserve: a retrospective analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;172:70–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardner DK, Schoolcraft WB. In vitro culture of human blastocyst. In: Jansen R, Mortimer D, editors. Towards reproductive certainty: infertility and genetics beyond 1999. Carnforth: Parthenon Press; 1999. pp. 378–388. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker VL, Jones CE, Cometti B, Hoehler F, Salle B, Urbancsek J, et al. Factors affecting success rates in two concurrent clinical IVF trials: an examination of potential explanations for the difference in pregnancy rates between the United States and Europe. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(4):1287–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.07.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fedorcsak P, Storeng R, Dale PO, Tanbo T, Abyholm T. Obesity is a risk factor for early pregnancy loss after IVF or ICSI. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:43–48. doi: 10.1080/j.1600-0412.2000.079001043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Metwally M, Cutting R, Tipton A, Skull J, Ledger WL, Li TC. Effect of increased body mass index on oocyte and embryo quality in IVF patients. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;15:532–538. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wittemer C, Ohl J, Bailly M, Bettahar-Lebugle K, Nisand I. Does body mass index of infertile women have an impact on IVF procedure and outcome? J Assist Reprod Genet. 2000;17:547–552. doi: 10.1023/A:1026477628723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vilarino F, Christofolini D, Rodrigues D, de Souza A, Christofolini J, Bianco B, et al. Body mass index and fertility: is there a correlation with human reproduction outcomes? Gynecol Endocrinol. 2011;27:232–236. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2010.490613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bellver J, Rossal L, Bosch E, Zúñiga A, Corona J, Melendez F. Obesity and the risk of spontaneous abortion after oocyte donation. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(5):1136–1140. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(03)00176-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tian L, Shen H, Lu Q, Norman R, Wang J. Insulin resistance increases the risk of spontaneous abortion after assisted reproduction technology treatment. JCEM. 2007;92(4):1430–1433. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonzalez R, Caballero-Campo P, Jasper M, Mercader A, Devoto L, Pellicer A, et al. Leptin and leptin receptor are expressed in the human endometrium and endometrial leptin secretion is regulated by the human blastocyst. JCEM. 2000;85(12):4883–4888. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.12.7060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luke B, Brown MB, Missmer SA, Bukulmez O, Leach R, Stern JE. The effect of increasing obesity on the response to and outcome of assisted reproductive technology: a national study. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(4):820–825. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.07.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]