Abstract

Purpose

Our primary aim was to explore themes regarding attitudes toward HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among young transgender women (YTW), in order to develop a theoretical model of PrEP uptake in this population disproportionally affected by HIV.

Methods

Qualitative study nested within a mixed-method study characterizing barriers and facilitators to health services for YTW. Participants completed an in-depth interview exploring awareness of and attitudes toward PrEP. Key themes were identified using a grounded theory approach.

Results

Participants (n=25) had a mean age of 21.2 years (SD 2.2, range 17–24), and were predominately multi-racial (36%) and of HIV-negative or unknown status (68%). Most participants (64%) reported prior knowledge of PrEP, and 28% reported current use or intent to use PrEP. Three major content themes that emerged were variability of PrEP awareness, barriers and facilitators to PrEP uptake, and emotional benefits of PrEP. Among participants without prior PrEP knowledge, participants reported frustration that PrEP information has not been widely disseminated to YTW, particularly by healthcare providers. Attitudes toward PrEP were overwhelmingly positive, however concerns were raised regarding barriers including cost, stigma, and adherence challenges. Both HIV-positive and negative participants discussed emotional and relationship benefits of PrEP, which were felt to extend beyond HIV prevention alone.

Conclusions

A high proportion of YTW in this study had prior knowledge of PrEP, and attitudes toward PrEP were positive among participants. Our findings suggest several domains to be further explored in PrEP implementation research, including methods of facilitating PrEP dissemination and emotional motivation for PrEP uptake.

The landscape of HIV prevention has shifted dramatically with the introduction of tenofovir-emtricitabine (TDF-FTC)-based HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), demonstrated to be >90% effective in preventing HIV in patients with high adherence.[1–3] Tenofovir-emtricitabine has been used safely for over a decade in combination antiretroviral therapy to treat individuals living with HIV, despite potential renal and bone toxicities.[4] In 2012, based on data from several large randomized controlled trials demonstrating safety and efficacy, the Food and Drug Administration approved TDF-FTC to be used as PrEP, a single-pill, daily HIV prevention regimen.[3, 5, 6] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has issued clinical practice guidelines recommending PrEP for individuals at high risk of acquiring HIV, including men and transgender women who have sex with men with a history of unprotected anal intercourse or STI in the past six months, or who are in serodiscordant relationships with HIV-positive partners.[6]

A key challenge in PrEP implementation involves increasing knowledge and uptake in populations at highest risk of HIV acquisition. Young transgender women (YTW) represent a population disproportionately affected by HIV, with an estimated HIV prevalence ranging from 5–22%.[7–9] Compared to other adults of reproductive age, the odds of HIV acquisition are 49 times higher among transgender women (TGW).[10] These HIV-related health inequities are related to the stigma, employment discrimination, and violence faced by TGW which frequently translate into participation in sex work, economic marginalization, homelessness, and poor access to gender-affirming healthcare. [11–16] An estimated 67% of YTW have exchanged sex for housing, food, drugs or money.[14] While PrEP is typically covered by insurance, and the pharmaceutical company offers a patient assistance program to cover drug or co-payment costs, out-of-pocket costs for those who do not qualify may reach $17,000 yearly for the drug alone, potentially limiting access in this economically marginalized population.

Despite the pressing need for PrEP among YTW, prior studies have demonstrated low rates of PrEP awareness.[17–19] Among participants in a life-skills intervention for YTW, while 62% met the CDC PrEP indications, only 31% were aware of PrEP.[20] The discordance between PrEP need and awareness highlights the critical need for research to better understand the unique barriers and facilitators of PrEP uptake among YTW, who have been underrepresented in PrEP clinical trials.[21] While TGW are often grouped into the larger epidemiologic category of “men who have sex with men” (MSM), their health care needs and motivations are unique, as are their HIV risk and barriers to accessing HIV prevention care.[22–24] These disparities are evident in a sub-analysis of the iPrEX study in which TGW, compared with MSM, had significantly lower rates of tenofovir detection, particularly among those concurrently using feminizing hormones.[25, 26]

Identifying a conceptual framework for PrEP uptake is a key task in optimizing the public health benefit of PrEP among YTW.[27] To date, few studies have explicitly explored perspectives on PrEP among YTW.[18, 19] Data from adult TGW have identified the importance of embedding PrEP within gender-affirming care, and addressing cost, access, and stigma as barriers to PrEP uptake.[18, 28] However, no qualitative studies have focused on the unique perspective of YTW. Adolescence is a distinct period of biologic, neurocognitive and psychosocial development, and it is likely that social determinants of PrEP use among YTW are different from those of older transgender women.[27]

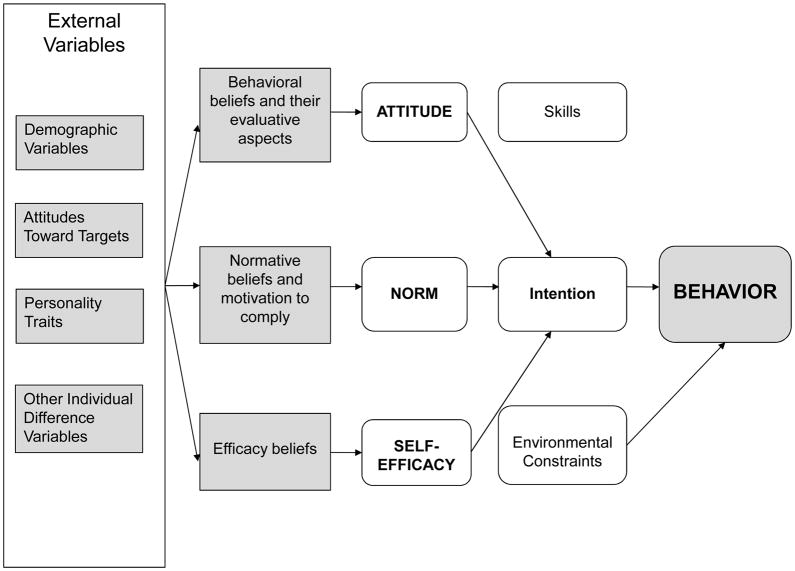

One candidate theoretical model is Fishbein’s Integrated Behavioral Model (Figure 1), which has previously been adapted to HIV treatment adherence behavior.[23, 24 29, 30] In this model, the intention to adopt a health behavior is driven by attitudes, perceived norms, and self-efficacy. For intention to translate into a desired behavioral outcome, such as PrEP uptake, knowledge, salience of the behavior, environmental factors and health-related skills must all function to facilitate behavioral action. While this is an attractive framework for PrEP utilization, it is currently unknown whether the socio-behavioral determinants of PrEP uptake for YTW fit within this model.

Figure 1.

Integrated Behavioral Model (IBM)

Therefore, the principal objectives of this study are to explore factors affecting the uptake of PrEP among YTW and develop a theoretical model for PrEP uptake among YTW.

METHODS

Design

This qualitative study was nested within a cross-sectional mixed-methods study characterizing barriers and facilitators to medical and mental health services for YTW living with and at high risk of HIV infection.[24] Participants were included if they were aged 16–24 years, assigned male sex at birth but identified as female, had HIV-positive or high-risk HIV negative/unknown status defined as condomless anal intercourse in the past year, and were able to understand written and spoken English. Participants were recruited from a variety of clinical and community-based organizations providing social and medical services to transgender youth and backpage.com, a website used for soliciting transactional sex. Approval was received from the Institutional Review Board at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Measures

Participants completed an individual, semi-structured, qualitative interview between February-December, 2015. Demographic data were obtained via computer-based Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap).[31] The interview contained a central PrEP question stem: “What have you heard about PrEP?,” followed with additional questions regarding sources of PrEP information. For participants with no awareness of PrEP, they were told “PrEP is taking a daily pill to prevent you from getting HIV.” Participants were then asked “How do you feel about PrEP for you and other trans girls?” If participants were HIV-positive, they were asked “How do you feel about PrEP for a partner?”

Analysis

All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and imported into NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 10, 2012.), a qualitative data management and analysis software. We used a grounded theory approach to identify codes that emerged from the data. The study team developed codes by independently reading each transcript line-by-line, and reaching consensus on a code list corresponding to each theme. Codes were subsequently applied to all transcripts. Four coders each independently coded two transcripts, with ≥95% inter-rater agreement before subsequent independent coding. The study team and PI met twice monthly to discuss emerging themes. All data were double-coded and coding discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The quotations in this manuscript were edited by the consensus of authors (SW, SL, ND) to protect confidentiality of participants, who were randomly assigned the initials associated with their respective quotes.

RESULTS

The mean age of participants (n=25) was 21.2 years (SD 2.2, range 17–24). Participants were predominately racial and ethnic minorities, with 36% identifying as multi-racial (n=9), 28% African American (n=7), and 20% Hispanic (n=5). HIV-positive status was reported by 32% (n=8). A history of transactional sex, specifically trading sex for money or drugs, was reported by 28% (n=7). Of the sample, 60% (n=15) were recruited from sites providing clinical and social services to YTW, 20% (n=5) responded to a recruitment flyer at an unknown location, 8% (n=2) were referred by another participant, 8% (n=2) from another study recruiting YTW, 4% (n=1) from a residential substance abuse treatment facility for transgender women. The three coding categories were PrEP knowledge, attitudes, and experiences. The overall weighted kappa for inter-rater agreement for the PrEP portion of the interview was 0.87 (98.4% agreement) and weighted kappas for the knowledge, attitudes and experience categories were 0.75, 0.81, and 0.63 respectively (98.6%, 98.8%, and 99.3% agreement). Within these categories, the dominant themes that emerged were variability of PrEP awareness, barriers and facilitators to PrEP uptake, and emotional benefits of PrEP.

Variability of PrEP Awareness

Among participants, 64% (n=16) reported having prior PrEP awareness. These participants reported hearing about PrEP from a diverse array of sources including friends (n=6), social media (n=5) (including Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Myspace and Hi5), LGBT community organizations, HIV testing (n=5) and healthcare providers (n=4).Three participants reported taking part in PrEP-related research studies. Participants cited the importance of friends in engaging them about PrEP.

“I haven’t really heard about PrEP on TV or radios. I actually was in my program, and they were doing a study about Truvada ... And I said hey, what the hell, I’ll do it. I think a friend of mine was doing it, and then he introduced me to it and I’ve been on PrEP for years. Good experience on PrEP.” (Participant ZM).

Among those without prior knowledge of PrEP (n=9), once informed about PrEP, attitudes were overwhelmingly positive. However, participants (n=3) expressed feelings of surprise and frustration that they had not previously heard about PrEP.

“I think that’s amazing, and … I should’ve heard of it by now. And that if it really does work and I haven’t heard of it by now, somebody needs to go shout it from the roof tops.” (UV)

“It’s like I've never heard of that. And I have other friends, and I'm pretty sure they've never heard of it either. So I think that the world should know of this…I think that's something …very huge and big, and once again, I'm very – how long have they had PrEP?” (VS)

Some participants noted that healthcare providers should be the primary PrEP information source, embedded within provision of hormones and gender-affirming care.

“… All those doctors should be equipped with PrEP and everything else that would be a necessity to protect trans women... Because a lot of us are exposed to sex trafficking business…it shouldn’t really come through peers or random people doing meetings or public speaking.... It should be coming from a doctor that gives them that information, who gives them that prescription, who gives them that appointment...Today you got your hormones. Next week, I’m gonna give you PrEP….If it’s a necessity for everybody else, it’s a necessity for us, too.” (PD)

Among those participants with prior awareness, discrepancies emerged between awareness and accuracy of PrEP knowledge, with participants citing a wide range of understanding regarding PrEP’s efficacy and mechanism of prevention. Several participants (n=3) were able to cite accurate estimates of PrEP’s >90% efficacy. However, two participants were unclear on the distinction between post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and PrEP.

“I didn’t know about PrEP until right before I went to get tested and someone was like, yeah, you can take this pill and it will help treat and eliminate HIV in your body within a month…And if you go get tested right after you had sex and they're like, it’s positive, but here is this med that can change your life and make it negative. How mind-blowing is that?” (CG)

However, most participants with prior awareness were able to describe the mechanism of action and proper use of PrEP, including the importance of daily medication adherence and ongoing condom use.

“Well, I'm about to start PrEP, but what I learned from it is that it’s a pill that can help prevent contracting HIV and AIDS. Usually it has to be in your system for about two weeks in order for the medicine to start working. That doesn't mean that you engage in unprotected sex. But in case you wind up dealing with somebody who has HIV and you haven't had unprotected sex, you'll be – you won’t get affected, as long as it’s in your system….” (SR)

Participants also drew comparisons between PrEP and other healthcare preventative measures including birth control and even hand sanitizer.

“I take PrEP. I take PrEP on a daily basis … it’s like Purell for HIV. It’s like 99 point nine percent of it, you're good. And you just take it on a daily basis. And I'm completely okay with that, because like I said, more pills isn't a problem for me.” (BR)

Facilitators and Barriers to PrEP Uptake

Seven of the study participants (28%) discussed current use or intent to start PrEP. Those already taking PrEP discussed the desire to stay HIV negative as an adherence-motivator.

“I’m on Truvada, and that’s – well, I found out it was for HIV-positive patients, but nothing will actually keep me from taking it… It helps you …fight off HIV viruses that come into your body. Before it can attack, it fights it off. Therefore, it’s dead instantly, and that’s what I want.” (ZM)

Notably, the positive benefits of PrEP seemed to extend beyond individual protection for a number of participants (n=8). These individuals emphasized that while they may not benefit from PrEP, the overall benefit to the transgender community was critical.

“I feel as though it’s actually a good thing, because for a long time, they've been looking for cures and stuff like that for HIV. But they've actually done something better than a cure, because now they can prevent you from getting it. So I actually think that it’s an excellent thing that they've brung to the transwomen and part of the gay community. It’s good for a lot of people.” (CL)

Participants typically cited the additional risk protection PrEP provided in conjunction with condom use as a facilitator, rather than viewing PrEP as a replacement for using condoms.

“… I might be engaged to this guy now, but sometimes you got these catchy moments and I could possibly end up single, God forbid, because I love to death out of him. But if I do end up single, at least I know that I have some type of backup, besides just the condom. Because at the end of the day, a condom didn't break if it’s not used properly…at least I have some type of assurance behind.” (BR)

However, barriers to PrEP uptake were raised by other study participants, including cost, adherence challenges, side effects and stigma. Participants reported concern about their financial ability to access PrEP, as well as the need to prioritize hormones over HIV prevention medication in the setting of limited financial resources.

“I guess the biggest thing that I would be curious about with regard to it is how many trans girls actually have access to it, right? Because, like I said, there are a lot of us who engage in high-risk sex work, and there are a lot of us who are very poor, and very chronically poor. And it's hard enough to afford our hormones a lot of the time, so, yeah.” (YH)

“I mean, if it was free, then that’s great, another pill to throw in there. But most – me and most trans women aren’t really the highest of classes. A lot of us are poor or even homeless, and can’t access – can’t really throw on another prescription there.” (EV)

While some participants expressed concerns about cost as a barrier, one current PrEP user voiced their positive experience with accessing PrEP for free through a community-based program.

“... Anybody can sign up for it – they don’t do it based on your insurance, because if you don’t have medical insurance…someone that will pay for it for you. So it’s actually a free ticket to life. You can take it, and you know that you're fine.” (CL)

Participants also discussed both the burden of adherence and PrEP-related stigma as barriers to uptake.

“I mean, I guess it’d be kind of a pain in the ass to take it every day. It could be like the – I don’t know – the queer male body person’s form of birth control. I guess that could be kind of expensive, and I can see there being a huge stigma against it.” (UV)

“But my thing, I don’t take PrEP because I don’t want to take a pill, I’d rather use condom because that’s just me and other people, they could say the other thing, which is fine.” (LV)

Lastly, while some participants felt that while PrEP may be beneficial for the transgender community overall, they themselves did not perceive that they engaged in sexual risk behavior that warranted PrEP use.

“…It depends on the type of life you live…If you know that you only have one steady sex partner and that you're at no risk . . . then don't worry about it. But if you know that you live a risky life prostituting, having sex with other people, that next time you go take that test and they come in … you should inquire about that PrEP thing.” (NR)

Emotional Benefits of PrEP

In addition to the tangible benefit of HIV prevention, participants also reported emotional benefits to PrEP that extended beyond risk mitigation. Participants discussed that PrEP provided a message of hope and support against what some felt was an inevitable possibility of acquiring HIV.

“The PrEP, it’s a …really good source of healing those that are suffering or feel that they can’t …live anymore, and PrEP is an awesome medication. I take it everyday, and it keeps me motivated and focused – that I can actually do this.” (ZM)

“I think that’s my big fear of being diagnosed positive for HIV is that I’m going to end up being a lonely shrew, who’s never touched by anyone again. And that freaks me out. That’s not fun. And so the fact that someone could take this medication and be able to not worry about that is kind of mind-blowing.” (CG)

Among HIV-positive participants, strengthening emotional relationships and physical closeness was cited as a reason to discuss PrEP with seronegative partners. One HIV-positive participant discussed establishing long-term intimacy and security as a reason to discuss PrEP with their seronegative partner.

“I want him to take it…I guess it's just something different because like I mean, I'm not going to – it's times that we have had sex, but – and he says to me, like he wants me to give it to him. You dig what I'm saying? So therefore he could be with me for the – I don't know – so he could be with me for the rest of his life and things like that.“ (NR)

HIV-positive participants also focused on the need to disseminate information about PrEP to their serodiscordant partners and HIV-negative friends and peers, rather than expressing regret that using PrEP to prevent HIV was no longer an option for them.

“…If I would have known about these pills before I got HIV, I’d have been taking the pills all the time…so it could prevent me from getting HIV. But now that I just found out about what the pills is, I think that every trans-women-girl needs to get them so it could prevent them from getting HIV because I don’t think they want to live that type of lifestyle.” (FG)

Another participant described PrEP as a source of emotional strength to the larger community of YTW:

“I think it’ll be a good thing for other trans women – trans people – trans community. It’ll save lives. It’ll keep people healthy and keep them motivated and keep them moving forward with their dreams and their plans without having to worry about, oh, I didn’t get tested…I think it would be a magnificent thing if everyone in the trans community was taking PrEP, but some things just aren’t meant for others. But if I could fly around the world and deliver PrEP to every trans, I would do so.” (ZM)

DISCUSSION

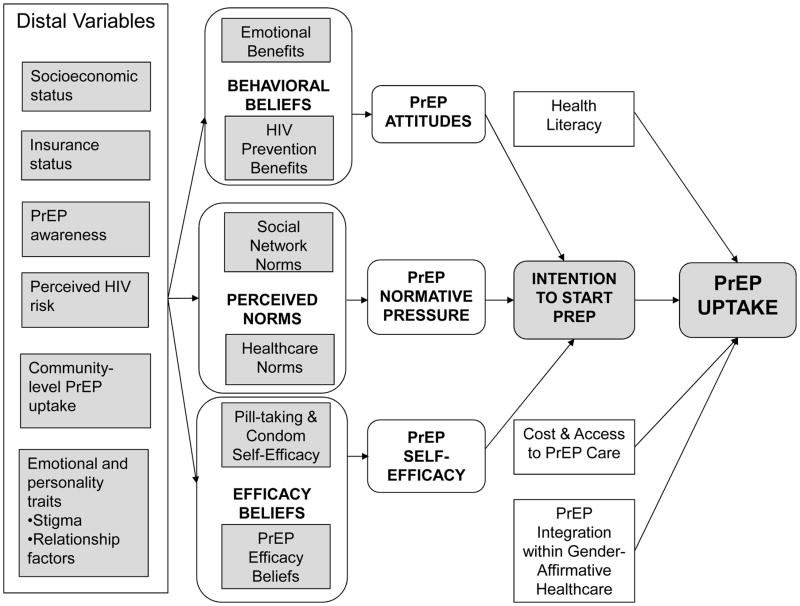

Our study identifies several potential determinants of PrEP uptake, which map well onto the Integrated Behavioral Model. We have generated a theoretical model of PrEP uptake based on these data (Figure 2) to be applied in future research on PrEP utilization in YTW. Notably, within this model, PrEP awareness is a key upstream determinant. In our study, 64% of participants had prior awareness of PrEP, a higher estimate than cited previously.[18–20, 32]. This may suggest more extensive dissemination of PrEP-related information in recent years. However, it may also reflect the importance of social media, which is both heavily used by youth and cited as a source of PrEP information by our participants, in the diffusion of PrEP knowledge.

Figure 2.

Integrated Model of PrEP Uptake in Young Transgender Women

In those participants with no prior knowledge of PrEP, there was a strong emphasis on the need to increase PrEP awareness among YTW. Future studies should explore the role of social media in disseminating accurate, gender-affirming, and youth-focused PrEP information through networks of YTW. Within our model, social network-based dissemination translates into normative PrEP beliefs within communities of YTW. However, participants also assigned healthcare providers a critical role in delivering PrEP information in a gender-affirmative healthcare context, suggesting that normative beliefs should be generated both from within the community and through interactions with healthcare systems[16].

Another emerging theme focused on emotional benefits of PrEP use that extended beyond its clinical benefit. These behavioral beliefs included PrEP’s role in increasing intimacy, empowerment, relationship security and future-orientation for YTW. HIV-positive participants noted that PrEP could serve as a mechanism for further intimacy with their serodiscordant partners and expressed intent to discuss PrEP with HIV-negative partners and peers. These themes echo previous research identifying intimacy-based motivations for PrEP use, [33] and reify the importance of avoiding fear and risk-based messaging in disseminating PrEP. For YTW, framing PrEP as an integral aspect of preventative health and healthy relationships may be a more effective strategy. Finally, the interest in PrEP expressed by HIV-positive participants suggests opportunities for combining both primary and secondary HIV prevention efforts within the larger YTW community.

Finally, in the final step of behavior initiation, participants identified environmental constraints to starting PrEP including access and cost. This theme manifested as difficulty prioritizing PrEP in the context of limited financial resources. Many YTW, despite numerous economic and psychosocial barriers, may have engaged in medical care to access gender-affirming hormones. In the hierarchy of competing health needs and at the intersection of multiple identities for many YTW, the critical necessities of hormonal therapy and mental health care may take precedence over PrEP. [15, 16, 18, 34] This theme emphasizes the need to co-locate PrEP care within gender-affirming primary care, mental health and social services.[35]

Our study is subject to potential limitations. Our qualitative data represent a convenience sample of YTW in Philadelphia, and are not generalizable to the global population of YTW. While 28% of participants engaged in sex work, a similar proportion as reported in recent data from Le et al, [36] it is lower than the previously cited 67% prevalence [14]. Thus, our data may not represent the population of YTW at highest risk for HIV infection. Future studies should augment recruitment efforts toward YTW engaged in transactional sex. Our sample size was too small to achieve saturation by demographic subgroups such as age or race. However, we did not note differences among responses by race or age and did achieve saturation for the group as a whole. Our findings are hypothesis-generating, and highlight the need for more robust quantitative studies powered to detect meaningful differences in the facilitators and barriers of PrEP uptake within subpopulations of YTW such as sex workers and racial and ethnic minorities and across the developmental trajectory. While our data provides a view into attitudes toward PrEP in a hard-to-reach population, only limited information was provided about PrEP, and future studies should explore perspectives on PrEP in a context where participants are informed of many of the nuances of PrEP utilization including cost, coverage, toxicities, and adherence. In qualitative research, there is always the possibility of bias in the interpretation of participant interviews. Our use of double coding of interviews and adherence to the iteratively-derived codebook were employed to decrease this potential source of bias.

In summary, we identified several key themes regarding PrEP knowledge, barriers and facilitators and emotional benefits within a sample of YTW. These themes provide fertile ground for developing transgender-specific theoretical models for PrEP uptake, and highlight the need for future robust studies to identify the key determinants of PrEP uptake and diffusion in YTW.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS.

This study identifies key themes regarding young transgender women’s (YTW) attitudes toward HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), highlighting the need to increase PrEP awareness; address potential barriers including cost, healthcare access and stigma; and harness the perceived emotional and relationship benefits of PrEP in order to increase uptake among YTW.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant (PI: Dowshen) the Penn Mental Health AIDS Research Center, an NIH-funded program (P30 MH 097488), and NIMH K23 MH102128 (PI: Dowshen). An abstract of data from the parent study was presented in poster form at the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine’s 2016 annual meeting.

All authors contributed to the research, writing and revision of this manuscript. An abstract of the data from the parent study was presented in poster form at the Society of Adolescent Health and Medicine 2016 annual meeting. The authors wish to thank the research team for their valuable contributions: Linda Hawkins PhD, Leeann Mao, Mark Meisarah, Derek Standlee, and Joshua Franklin.

Funding: This research was supported by a grant (PI: Dowshen) from the Penn Mental Health AIDS Research Center (PMHARC), an NIH-funded program (P30 MH 097488) and NIMH K23 MH102128 (Pi: Dowshen)

Abbreviations

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- PrEP

Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis

- TGW

Transgender Women

- MSM

Men who have Sex with Men

- YTW

Young Transgender Women

- SD

Standard Deviation

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: No authors have conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Grant RM, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 14(9):820–9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70847-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormack S, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2015 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00056-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant RM, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health and Human Services, editor. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents, Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. 2016. pp. 1–288. [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Public Health Service. Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV in the United States: A Clinical Practice Guideline. 2014. pp. 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thigpen MC, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):423–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson EC, et al. Differential HIV risk for racial/ethnic minority trans*female youths and socioeconomic disparities in housing, residential stability, and education. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(Suppl 3):e41–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson EC, et al. Transgender female youth and sex work: HIV risk and a comparison of life factors related to engagement in sex work. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(5):902–13. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9508-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garofalo R, et al. Overlooked, misunderstood and at-risk: exploring the lives and HIV risk of ethnic minority male-to-female transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(3):230–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baral SD, et al. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(3):214–22. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70315-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herbst JH, et al. Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of transgender persons in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(1):1–17. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9299-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Operario D, Soma T, Underhill K. Sex work and HIV status among transgender women: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;48(1):97–103. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31816e3971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poteat T, et al. Global Epidemiology of HIV Infection and Related Syndemics Affecting Transgender People. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(Suppl 3):S210–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brennan J, et al. Syndemic theory and HIV-related risk among young transgender women: the role of multiple, co-occurring health problems and social marginalization. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1751–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grossman AH, D'Augelli AR. Transgender youth: invisible and vulnerable. J Homosex. 2006;51(1):111–28. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reisner SL, Radix A, Deutsch MB. Integrated and Gender-Affirming Transgender Clinical Care and Research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(Suppl 3):S235–42. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giguere R, et al. Acceptability of Three Novel HIV Prevention Methods Among Young Male and Transgender Female Sex Workers in Puerto Rico. AIDS Behav. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1387-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sevelius JM, et al. 'I am not a man': Trans-specific barriers and facilitators to PrEP acceptability among transgender women. Glob Public Health. 2016:1–16. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1154085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson E, et al. Awareness, Interest, and HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Candidacy Among Young Transwomen. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30(4):147–50. doi: 10.1089/apc.2015.0266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuhns LM, et al. Correlates of PrEP Indication in a Multi-Site Cohort of Young HIV-Uninfected Transgender Women. AIDS Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1182-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Escudero DJ, et al. Inclusion of trans women in pre-exposure prophylaxis trials: a review. AIDS Care. 2015;27(5):637–41. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.986051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Safer JD, et al. Barriers to healthcare for transgender individuals. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23(2):168–71. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poteat T, et al. HIV risk and preventive interventions in transgender women sex workers. Lancet. 2015;385(9964):274–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60833-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dowshen N, et al. Barriers and Facilitators to HIV Prevention, Testing, and Treatment among Young Transgender Women. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2016;58(2):S81–S82. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deutsch MB, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in transgender women: a subgroup analysis of the iPrEx trial. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(12):e512–9. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(15)00206-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson PL, Reirden D, Castillo-Mancilla J. Pharmacologic Considerations for Preexposure Prophylaxis in Transgender Women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(Suppl 3):S230–4. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garofalo R, et al. Behavioral Interventions to Prevent HIV Transmission and Acquisition for Transgender Women: A Critical Review. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(Suppl 3):S220–5. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Golub SA, et al. From efficacy to effectiveness: facilitators and barriers to PrEP acceptability and motivations for adherence among MSM and transgender women in New York City. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(4):248–54. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fishbein M. The role of theory in HIV prevention. AIDS Care. 2000;12(3):273–8. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fishbein M, Guinan M. Behavioral science and public health: a necessary partnership for HIV prevention. Public Health Rep. 1996;111(Suppl 1):5–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris PA, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson EC, et al. Knowledge, Indications and Willingness to Take Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis among Transwomen in San Francisco, 2013. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Golub SA. Tensions Between the Epidemiology and Psychology of HIV Risk: Implications for Pre-exposure Prophylaxis. AIDS Behav. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0770-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionalityan important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1267–73. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mayer KH, Grinsztejn B, El-Sadr WM. Transgender People and HIV Prevention: What We Know and What We Need to Know, a Call to Action. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(Suppl 3):S207–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Le V, et al. Types of social support and parental acceptance among transfemale youth and their impact on mental health, sexual debut, history of sex work and condomless anal intercourse. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(3 Suppl 2):20781. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.3.20781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]