Abstract

We report the development of a serodiagnostic method for Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) disease with an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) with the MAC-specific glycopeptidolipid (GPL) core as the antigen. In this study, we confirmed by EIA that the GPL core antibody was in the sera of immunocompetent patients with MAC disease. The EIA for quantifying the GPL core antibody was evaluated as a clinical tool for serodiagnosis of pulmonary MAC disease. A significant increase in GPL core antibodies (immunoglobulins G, A, and M) was detected in sera of patients with MAC pulmonary diseases when they were compared to patients who were colonized with MAC, patients with Mycobacterium kansasii disease or tuberculosis, and healthy subjects. The sensitivities and specificities of the GPL core-based EIA for diagnosis of MAC pulmonary disease were 72.6% and 92.2%, respectively, for IgG, 92.5% and 95.1%, respectively, for IgA, and 78.3% and 91.0%, respectively, for IgM. The best sensitivity and specificity were obtained by measuring immunoglobulin A antibodies against GPL core antigen. The level of GPL core antibodies reflected disease activity, since it decreased in cured MAC patients who had responded to chemotherapy. Measurement of serum antibodies against GPL core is useful for both diagnosis and assessment of disease activity in MAC disease of the lung.

About 10 to 20% of mycobacterial diseases are caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Among nontuberculous mycobacteria, Mycobacterium avium and M. intracellulare are closely related and commonly grouped to form the M. avium complex (MAC). The diagnosis of pulmonary MAC disease is based on a combination of clinical, radiographic, and microbiologic criteria and the exclusion of other diseases that are similar clinically (1). MAC organisms are of low pathogenicity and single positive specimens with low numbers of organisms are frequently recovered from individuals with no apparent disease. The colonization of asymptomatic individuals, the possibility of environmental contamination of specimens, and the absence of standardized skin test antigens for confirming nontuberculous mycobacterial disease all combine to complicate interpretation by physicians of diagnostic tests for nontuberculous mycobacteria. The development of a serodiagnostic test to detect MAC infection is necessary to rapidly and accurately diagnose pulmonary MAC disease.

In a previous study, we reported the characteristics of an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for MAC pulmonary diseases with a mixture of glycopeptidolipid (GPL) antigens from 11 reference strains of MAC and applied the assay to serodiagnosis of patients with MAC disease (7). However, there are problems with the transition of the assay from a research tool to widespread clinical use. Specifically, preparation of GPL antigen of consistent quality as well as quantity from 11 reference strains of MAC is both time- and cost-consuming. Identification of a simple and stable antigen for use in serodiagnostic tests for MAC disease is necessary. In addition, the natural history of MAC lung disease is unpredictable in immunocompetent patients. Some patients are resistant to multiple drug chemotherapy and show persistent excretion of MAC organisms and a steady worsening of chest radiographic findings until death. Other patients maintain a stable clinical and radiographic picture for years (1).

We have been investigating the relationship between the serotype of MAC isolates and the long-term survival of patients with pulmonary MAC disease. However, it was difficult to accurately identify the serotypes of clinical isolates with the seroagglutination test and thin-layer chromatography (TLC). The GPLs from different clinical isolates are serologically cross-reactive and have similar Rf values on TLC (17). When we used serodiagnosis to identify antibody serotypes against the different types of GPLs in some pulmonary MAC disease patients, we detected antibody against all 11 GPLs in each serum. We hypothesized that the antibody to the GPL core could be the reactive component in the sera of pulmonary MAC disease patients rather than all patients infected by every MAC serotype. Our hypothesis was supported by analysis of GPLs that shows that the fatty acyl-d-Phe-d-allo-Thr-d-Ala-l-alaninol-O-(3,4-di-O-methyl-Rha), or GPL core, is common to all serotypes (3). Because the GPL core is generally considered nonantigenic, it has received less attention than the serologically active polar GPLs that can be identified by immunoassay.

In the present study, we show that the immunodominant epitope of GPLs is the GPL core antigen and we assessed whether an EIA with GPL core antigen is a useful clinical tool for diagnosis of pulmonary MAC diseases. Because whole GPL antigens are not cross-serotypic, it is necessary to prepare a mixture of GPL antigens from different serotypes of MAC (7). By contrast, GPL core antigen is the dominant epitope and cross-reacts with serum antibodies obtained from patients with MAC disease due to different serotypes of the organisms. We have asked whether EIA serodiagnosis with GPL core antigen could differentiate pulmonary MAC disease from MAC colonization and pulmonary tuberculosis and EIA serodiagnostic results could aid in evaluating the effectiveness of the chemotherapy as well as the timing of the future cessation of treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects.

Sera were obtained from patients with pulmonary disease due to nontuberculous mycobacteria (MAC and M. kansasii), pulmonary tuberculosis, individuals with MAC colonization, and healthy subjects (Table 1). They were aliquoted into individual 1.0-ml doses in tubes, stored at −80°C until use, and thawed at room temperature just before the assay. Culture isolates of mycobacteria were identified by biochemical analyses and DNA probes. MAC (n = 106) included M. avium (n = 49), M. intracellulare (n = 22), and unclassified strains (n = 35). MAC disease was diagnosed according to the criteria of the American Thoracic Society (1). Subjects with a small amount of bacteria in a single positive sputum culture but no symptoms and normal findings on the chest computed tomograph were categorized as being colonized with MAC. Healthy subjects had no history of mycobacterial diseases. There were no subjects that were known to be positive for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 or type 2.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the subjects in a study of EIA for diagnosis of pulmonary MAC diseasea

| Characteristic | Group

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAC diseaseb | MAC colonizationc | M. kansasii disease | Tuberculosis | Healthy subjects | |

| No. | 106 | 11 | 30 | 77 | 126 |

| Mean age (yr) ± SD | 65.4 ± 10.4 | 60.5 ± 15.8 | 52.1 ± 12.7d | 50.9 ± 18.6d | 47.8 ± 14.3d |

| Age range (yr) | 37-86 | 27-80 | 29-80 | 14-83 | 26-88 |

| No. male/no. female | 40/66 | 3/8 | 28/2d | 66/11d | 70/56d |

| Mean duration of disease (yr) ± SD | 3.8 ± 4.3 | 0 | 0.5 ± 0.8d | 0.5 ± 1.1d | 0 |

All subjects were either seronegative for HIV or had no clinical symptoms consistent with AIDS.

MAC disease included M. avium (n = 49), M. intracellulare (n = 22), and unclassified strains of MAC (n = 35).

MAC colonization included M. avium (n = 4), M. intracellulare (n = 3), and unclassified strains of MAC (n = 4).

Statistically significant difference compared to patients with MAC disease (P < 0.05).

Twenty-seven patients had initially received combination chemotherapy for pulmonary MAC disease with clarithromycin, rifampin, and ethambutol for more than 1 year and/or streptomycin for 2 months according to the recommendation of the American Thoracic Society. Patients whose cultures converted to negative after treatment and whose sputum remained negative on culture for 6 months were categorized as cured. Patients whose cultures did not convert to negative despite treatment were classed as treatment failures. Serum specimens had been obtained sequentially before and after the chemotherapy. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. This project was approved by the Toneyama National Hospital institutional review board for human subject experimentation and complies with international guidelines for studies involving human subjects.

Preparation of GPL core antigen.

The 11 reference strains of MAC obtained from the American Type Culture Collection were serotypes 1 (ATCC 15769), 4 (ATCC 35767), 6 (ATCC 35773), 7 (ATCC 35847), 8 (ATCC 35771), 9 (ATCC 35774), 12 (ATCC 35762), 13 (ATCC 35768), and 14 (ATCC 35761), 16 (ATCC 13950), and 20 (ATCC 35764) (5). After culture in Middlebrook 7H9 (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) for 3 weeks, mycobacteria were autoclaved and lyophilized. Lyophilized bacteria were extracted with chloroform-methanol. Alkali-stable lipids were applied to a silica gel column (Analtech, Newark, Del.) and GPLs were eluted with methanol-chloroform. The eluted GPLs were purified repeatedly by one-dimensional thin-layer chromatography (TLC) that was developed with chloroform-methanol-distilled water until a single spot was obtained (2, 3, 7). Subsequently reductive β-elimination of GPL was used to prepare GPL core (11, 15). Briefly, purified GPL was dissolved in ethanol-sodium hydroxide-NaBH4. The reaction mixture was heated, neutralized with acetic acid, and then evaporated. The organic phase was washed, and the resulting GPL core was collected. Both the purity and molecular weight of the GPL core were examined by two-dimensional TLC and by fast atom bombardment-mass spectrometry (FAB-MS) (Jeol, Tokyo, Japan).

EIA.

EIA was done with slight modifications of the previously published method (9). Briefly, microtiter plates (Nunc Products, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with 0.5 μg of GPLs and GPL core of M. avium serotype 4/well. Serum samples were diluted 40-fold with phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% bovine serum albumin. Diluted serum samples were added, followed by incubation for 1 h at 37°C. Plates were washed, then peroxidase-conjugated F(ab′)2 of goat antibody against human immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgA, or IgM (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was added, and plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Unbound labeled antibody was removed by washing and the substrate, o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (Sigma), was added. Following color development, the optical densities of the wells on the plates were read for absorbance at 492 nm in a reader (model 550, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan). To determine the presence of an immunodominant epitope, inhibition of EIA was done by addition of either the mixture of GPL (7) or GPL core antigen at concentrations ranging from 1 to 5 μg/well. All assays were performed in triplicate and without prior knowledge of the clinical status of the patient.

Statistical analyses.

All data were analyzed with the statistical analysis software package StatView 5.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). Antibody EIA titers in individual patients or patient groups were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Further comparisons of data from patient groups were made with analysis of variance and nonparametric analysis. Spearman's correlation coefficient by rank was used to determine the relationship between EIA titers and clinical parameters. The chi-square test was used to determine the relationship between gender and patient group. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Purification of GPL core antigens from MAC strains.

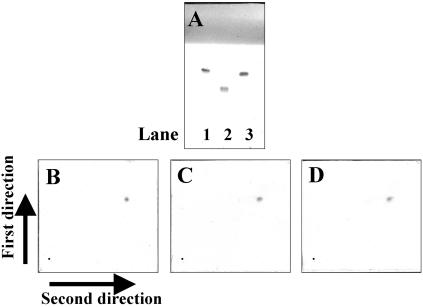

One-dimensional TLC analysis of GPL antigens prepared from three serotypes (serotype 4 M. avium, and serotypes 16 and 20 M. intracellulare) of MAC reference strains showed a single spot, but each had distinct patterns (Fig. 1A), because the oligosaccharides were different in each strain. The two-dimensional TLC analysis of GPL core antigens prepared from serotype 4 (Fig. 1B), serotype 16 (Fig. 1C), and serotype 20 (Fig. 1D) exhibited a single spot that was identical among the strains. These results are consistent with the previous report that the common chemical structure of GPL is composed of C-mycoside, or GPL core (3, 7).

FIG. 1.

One-dimensional (A) and two-dimensional TLC analysis (B to D) of GPLs and GPL core. Three reference strains of MAC were analyzed: serotypes 4 (ATCC 35767, lane 1), 16 (ATCC 13950, lane 2), and 20 (ATCC 35764, lane 3). GPLs were purified repeatedly by one-dimensional (1D) TLC developed with chloroform-methanol-distilled water until a single spot was obtained (A). Subsequently GPLs were β-eliminated to obtain GPL core, and then the purity of GPL core was examined by two-dimensional (2D) TLC (first in the vertical and second in the horizontal direction. B, serotype 4; C, serotype 16; D, serotype 20).

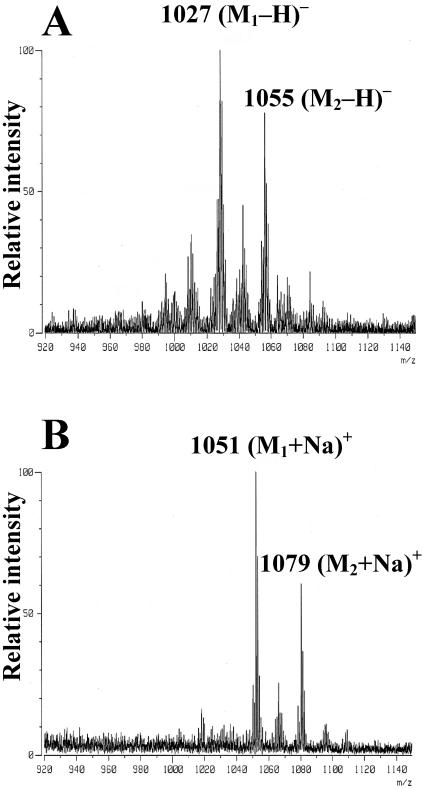

In a subsequent step, purified GPL cores of three MAC strains obtained by two-dimensional TLC were analyzed by FAB-MS to determine the molecular weight. The GPL core of serotype 4 showed a main peak at a m/z of 1,027 corresponding to the (M-H)− ion in negative-ion mode (Fig. 2A) and an m/z of 1051 corresponding to the (M+Na)+ in positive-ion mode (Fig. 2B). Based on these results, the molecular weight of the GPL core of serotype 4 was calculated to be 1,028, which was consistent with the previous report (4). Similar results were obtained with serotypes 16 and 20 (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

FAB-MS of purified GPL core. GPL core of serotype 4 showed a main peak at an m/z of 1,027, corresponding to the (M-H)- ion in negative-ion mode (A) and an m/z of 1,051 corresponding to the (M+Na)+ in positive-ion mode (B). Based on these results, the molecular weight of GPL core of MAC serotype 4 was calculated to be 1,028.

Development of the EIA.

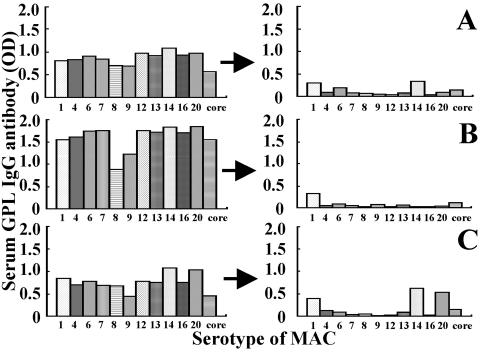

We identified sera from pulmonary MAC disease patients with antibody against all 11 GPLs (Fig. 3). The titers of GPL antibody were reduced to background levels by adding GPL core antigens (5 μg/ml) to the assay for antibodies to every GPL, with the exceptions shown in Fig. 3. Antibodies to serotypes 1, 6, and 14 in patient A, serotype 1 in patient B, and serotypes 1, 14, and 20 in patient C were still detectable after adding core antigen. We considered the possibility that there was antibody against GPL core in the sera of pulmonary MAC disease patients and that the remaining antibodies after addition of the GPL core antigens might be to the serotype-specific oligosaccharide polar GPL antigens. We also examined the antigen specificity of the EIA by adding concentrations of GPL core antigens ranging from 1 to 5 μg to the assay for antibodies to either a mixture of GPLs prepared from 11 reference strains of MAC (five strains of M. avium and six strains of M. intracellulare) (7) or GPL core from MAC serotype 4 M. avium.

FIG. 3.

Antibody titers to 11 serotypes of MAC and GPL core antigen in sera from three patients with MAC disease before and after adsorption with GPL core antigen. The serum titers before adsorption are shown in the left panel. After adsorption with 5 μg of GPL core antigen per ml, the titers of GPL antibody were reduced to background levels in most samples, with the exception of patient C, as shown in this figure. The titers of the three serum samples after adsorption are shown in the right panel.

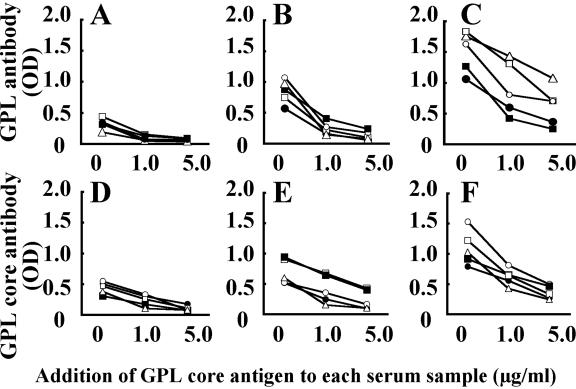

Sera were collected from five patients with pulmonary MAC disease (two patients with M. avium and three patients with M. intracellulare). Addition of GPL core inhibited the optical density levels in the EIA for IgG (Fig. 4A and 4D), IgA (Fig. 4B and 4E), and IgM (Fig. 4C and 4F) antibodies against both GPLs (Fig. 4A to 4C) and GPL core antigens (Fig. 4D to 4F) in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 4). Similar results were obtained by the addition of GPL core antigens purified from other serotypes of MAC, such as serotypes 16 and 20 (data not shown). These results point to the GPL core of MAC as having the immunodominant epitope of GPLs.

FIG. 4.

Antigen specificity and recognition of an immunodominant epitope for GPLs. GPL core concentrations ranging from 1 to 5 μg/ml were added to the EIA with a mixture of GPLs prepared from 11 reference strains of MAC and GPL core of a serotype 4 strain. Sera were from five patients with MAC pulmonary disease, patient A (○), patient B (•), patient C (□), patient D (▪), and patient E (▵). Addition of GPL core antigen inhibited the level of optical density (OD) by IgG (panels A and D), IgA (panels B and E), and IgM (panels C and F) antibodies against GPLs (panels A, B, and C) and GPL core (panels D, E, and F) in a dose-dependent fashion.

Levels of anti-GPL core IgG, IgA, and IgM antibodies in serum samples obtained from study subjects.

The levels of IgG, IgA, and IgM antibodies against GPL core antigen was summarized in Table 2. IgG, IgA, and IgM antibody levels were significantly elevated in MAC disease patients but not in other patient groups (P < 0.0001). In the group of MAC disease patients, relationships between GPL core antibody levels of IgG and IgM and IgA and IgM were significant (P < 0.05) but not IgG and IgA. No relationships were found between antibody levels and clinical parameters, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and the number of colonies after cultures, with the single exception of IgM antibody levels and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (P < 0.05).

TABLE 2.

Serum antibodies against GPL core antigen in patients with lung disease

| Group | Titera

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG

|

IgA

|

IgM

|

||||

| Mean ± SD | 95% CI | Mean ± SD | 95% CI | Mean ± SD | 95% CI | |

| MAC disease | 0.281 ± 0.346 | 0.017-1.042 | 0.435 ± 0.385 | 0.051-1.599 | 0.714 ± 0.492 | 0.133-2.720 |

| MAC colonization | 0.026 ± 0.027* | 0.005-0.104 | 0.021 ± 0.049* | 0.006-0.143 | 0.164 ± 0.115* | 0.038-0.472 |

| M. kansasii disease | 0.039 ± 0.015* | 0.008-0.144 | 0.043 ± 0.054* | 0.010-0.120 | 0.159 ± 0.131* | 0.028-0.508 |

| Tuberculosis | 0.047 ± 0.031* | 0.021-0.068 | 0.030 ± 0.018* | 0.012-0.065 | 0.156 ± 0.113* | 0.040-0.409 |

| Healthy subjects | 0.040 ± 0.028* | 0.018-0.074 | 0.031 ± 0.042* | 0.008-0.077 | 0.164 ± 0.092* | 0.031-0.570 |

CI, confidence interval. *, statistically significant difference compared to patients with MAC disease (P < 0.0001).

Sensitivity and specificity of GPL core-based EIA for diagnosis of MAC disease.

The cutoff levels, as defined with receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves, were 0.064 for GPL core IgG, 0.072 for IgA, and 0.312 for IgM. The sensitivity and specificity of GPL core-based EIA for diagnosis of MAC pulmonary disease were 72.6% and 92.2%, respectively, for IgG, 92.5% and 95.1%, respectively, for IgA, and 78.3% and 91.0%, respectively, for IgM (Table 3). The best sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of MAC pulmonary disease was obtained by measuring IgA antibodies against GPL core. With national surveillance data for Japan, the prevalence of MAC pulmonary disease was estimated to be 2.45 cases per 100,000 population (13). The predictive values for positive results [true positive/(true positive + false positive)] and negative results [true negative/(true negative + false negative)] were 80.2% and 88.6%, respectively, (corrected values, 0.023% and 99.99%, respectively, by the prevalence rate) for IgG, 89.1% and 96.7%, respectively, (corrected values, 0.046% and 99.99%, respectively, by the prevalence rate) for IgA, and 79.0% and 90.6%, respectively, (corrected values, 0.021% and 99.99%, respectively, by the prevalence rate) for IgM.

TABLE 3.

Sensitivity and specificity of EIA for serodiagnosis of pulmonary MAC disease

| Group | No. | IgG

|

IgA

|

IgM

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (no. of seropositives) | Specificity (no. of seronegatives) | Sensitivity (no. of seropositives) | Specificity (no. of seronegatives) | Sensitivity (no. of seropositives) | Specificity (no. of seronegatives) | ||

| MAC disease | 106 | 72.6 (77) | 27.4 (29) | 92.5 (98) | 7.5 (8) | 78.3 (83) | 21.7 (23) |

| MAC colonization | 11 | 9.1 (1) | 90.9 (10) | 9.1 (1) | 90.9 (10) | 18.2 (2) | 81.8 (9) |

| M. kansasii disease | 30 | 6.7 (2) | 93.3 (28) | 10.0 (3) | 90.0 (27) | 16.7 (5) | 83.3 (25) |

| Tuberculosis | 77 | 10.4 (8) | 89.6 (69) | 5.2 (4) | 94.8 (73) | 5.2 (4) | 94.8 (73) |

| Healthy subjects | 126 | 6.3 (8) | 93.7 (118) | 3.2 (4) | 96.8 (122) | 8.7 (11) | 91.3 (115) |

Disease activity and level of GPL core antibodies.

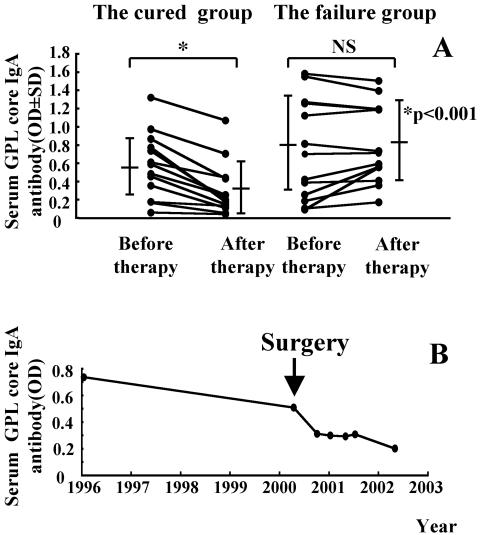

The levels of GPL core IgA antibody were quantified before implementation and after completion of antimicrobial chemotherapy for 27 patients with pulmonary MAC disease. The patients were divided into two groups according to the outcome of chemotherapy. There were 14 patients in the cured group and 13 patients in the treatment failure group. The GPL core IgA antibody levels before chemotherapy were the same in both groups. To determine whether the level of GPL core antibodies reflected MAC disease activity, we compared antibody levels sequentially in each patient before and after chemotherapy. In the cured patient group, the mean level of antibody before chemotherapy was 0.546 ± 0.369. After chemotherapy the mean level of antibody was 0.289 ± 0.293. In the treatment failure group, the mean level of antibody before chemotherapy was 0.704 ± 0.550 and after chemotherapy was 0.767 ± 0.429.

The mean IgA antibody titers in the cured group significantly decreased after chemotherapy (P < 0.001) but did not change in the treatment failure group (Fig. 5A). In the treatment failure group, a 61-year-old female patient had undergone lobectomy after chemotherapy. Her GPL core IgA antibody titer decreased rapidly after the surgery, and her sputum specimens converted to negative (Fig. 5B). No statistically significant differences were found between the cured and treatment failure groups for age, gender, duration of treatment, and timing of serum collection. Similar results were observed in changes of IgG and IgM antibodies to GPL core antigen before and after chemotherapy in both the cured (P < 0.001: IgG and IgM) and treatment failure groups (IgG, P = 0.25; IgM, P = 0.55).

FIG. 5.

Disease activity and level of antibodies to MAC GPL core. The levels of serum IgA antibodies to GPL core are shown before and after the completion of antimycobacterial chemotherapy for both the cured (14 MAC patients) and the failure groups (13 MAC patients). In the cured group, the culture results indicated conversion from positive to negative after successful chemotherapy, and in the failure group, the culture results indicated no conversion to negative despite treatment. All results are expressed as individual data (▪), and the bars show the mean ± standard deviation for each group. The optical density levels decreased significantly (*, P < 0.001) in the cured group of patients but were not changed (P = 0.381) in the treatment failure group. The changes of serum IgA levels of to GPL core in a 61-year-old female MAC patient who had undergone lobectomy is shown in B. IgA levels decreased rapidly after the surgery, and sputum cultures converted from positive to negative.

DISCUSSION

In Japan, there are more than 30,000 new cases of mycobacterial diseases every year (incidence rate per 100,000, 25.8) and about 20% of them in clinical practice are caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria such as MAC and M. kansasii. Of theses, 70% were MAC and 20% were M. kansasii (13). Because there are more than 500 patients with pulmonary disease due to nontuberculous mycobacteria in our hospital specializing in chest diseases and our previous study has demonstrated the availability of EIA with a mixture of GPL antigens for diagnosis of MAC pulmonary disease, we could conduct the present study.

The chemical structure of GPL is composed of a common GPL core, fatty acyl-d-Phe-d-allo-Thr-d-Ala-l-alaninol-O-(3,4-di-O-methyl-Rha), with the different oligosaccharide (polar GPL) moieties linked at the Thr substituent of the core. GPLs are the major cell surface antigens of slowly growing mycobacteria, such as MAC and M. scrofulaceum. There are 31 distinct GPL serotypes. In the present study, we report detection by EIA of an antibody against the purified MAC GPL core in sera of patients with pulmonary MAC disease. The GPL antibody levels were reduced in a dose-dependent fashion when different concentrations of GPL core were incorporated into the EIA. These results show that GPL core, the common component of all GPLs, has an immunodominant epitope in MAC strains. Although the present study has demonstrated that GPL core is the dominant epitope, there is a possibility that other components of GPLs, including oligosaccharide and oligosaccharide-GPL complex and whole GPLs, possess antigenicity. Indeed, serum antibodies to whole GPL antigen were incompletely adsorbed with GPL core with the serum of the patient C (Fig. 3). Serotype-specific antisera were produced from rabbits by repeated immunizations with MAC (14). Thus, both the individual variability of humans and the species specificity in the immune response to antigens should be noted.

The recognition that there was an immunodominant antigenic epitope on the GPL core has minimized some of the problems of antigen preparation from an array of MAC strains. The GPL core based EIA described in this study had both high sensitivity and specificity when used to assay MAC-specific IgG, IgA, and IgM, and results were comparable to those previously obtained with mixtures of GPL antigens from 11 reference strains of MAC (9). It was likely that antibodies against both GPL core and polar GPL were being detected in the EIA when mixtures of GPL antigens were used since the addition of GPL core antigens reduced levels of GPL antibodies without reducing levels of GPL antibodies to serotype-specific oligosaccharide antigens. For the diagnosis of MAC pulmonary disease, the best sensitivity and specificity were obtained by measuring IgA antibodies against GPL core. The values for IgG antibodies against a mixture of GPL antigens were almost the same as IgA antibodies against GPL core. However both the ease and low cost of antigen preparation make the EIA for IgA with GPL core antigen a practical tool. Future studies would also benefit from the standardization of serum samples, as well as the methods for rapid and reliable serodiagnosis of MAC disease.

We previously reported the development of a rapid diagnostic EIA for tuberculosis, which is specific for antibodies to tuberculous glycolipid (9, 10). It was recently reported that the combination of lipoarabinomannan polysaccharide antigen, antigen-60, and tuberculous glycolipid appear to be the best choices as antigens for the serodiagnosis of tuberculosis (12). When we combined the results of three serodiagnostic tests which used lipoarabinomannan, antigen-60 and tuberculous glycolipid as antigens, the nontuberculous mycobacteria patients could not be differentiated serologically from tuberculosis patients because tuberculous glycolipid, lipoarabinomannan polysaccharide, and antigen-60 are common cell wall components of all acid-fast organisms, such as mycobacteria and nocardiae.

Nontuberculous mycobacteria cause a chronic, slowly progressive pulmonary infection resembling tuberculosis in immunocompetent hosts. MAC ranks first and M. kansasii ranks second among causes of human nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease (6). We have used GPLs as an antigen for the differential serodiagnosis of pulmonary MAC disease and tuberculosis. This is feasible because GPLs are the major cell surface antigens of slowly growing mycobacteria, such as MAC and M. scrofulaceum (3). By contrast, M. kansasii and M. tuberculosis complex, including bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG), do not have GPLs in their cell walls (3). In this study the low positive rate (Table 3) and low levels of serum GPL core antibodies in M. kansasii and tuberculosis patients confirmed that serodiagnosis by EIA with GPL core antigen could differentiate pulmonary MAC disease from both pulmonary tuberculosis and pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease caused by M. kansasii. Rapidly growing mycobacteria such as M. chelonae and M. fortuitum also have GPLs as major cell surface components but rarely cause pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacteria disease in humans (6).

MAC organisms are ubiquitous in nature. They have been isolated from water, soil, plants, house dust, and other environmental sources (6) and asymptomatic colonization of human hosts can occur. In this study, GPL core-based EIA could exclude MAC colonization as well as tuberculosis and M. kansasii disease because sera of individuals with MAC colonization have both a low positive rate and low antibody levels (Table 2, Table 3).

Despite the fact that most Japanese people (≥90%) have been given BCG (16), the rate of seropositivity for GPL core antibodies in healthy subjects is low (3.2 to 8.7%). One explanation is that GPL core-based EIA for MAC disease is not affected by prior vaccination with BCG, because GPLs are not present in M. tuberculosis complex (3). Although M. tuberculosis complex and M. kansasii do not have GPLs, a low positive rate (Table 3) and low levels of serum GPL antibodies in M. kansasii (6.7 to 16.7%), tuberculosis (5.2 to 10.4%), and healthy subjects (3.2 to 8.7%) could be detected. It is possible that latent subclinical infection with MAC leads to false-positive results since 7 to 12% of adults show evidence of subclinical MAC infection when tested for delayed-type skin reactivity to M. avium sensitin (18).

In our study, we were unable to determine the rate of subclinical infection with MAC because an appropriate test is not yet available in Japan. However, there are several possible explanations for the low levels of antibody against GPL core antigen. First, a low positive rate is directly related to the cutoff values defined by with the ROC curves. Second, subclinical infections with other nontuberculous mycobacteria, such as M. chelonae and/or M. fortuitum, must be excluded because such organisms possess GPL antigens in their cell surface (8), which may induce antibody production in the host. Third, a follow up of this antibody levels in these individuals needs to be done looking for individual variability according to the time. There are several possible explanations for the few false-negative patients (29 for IgG, 8 for IgA, and 23 for IgM); presence of circulating immune complexes, excess of GPL core antigens relative to antibodies, very low bacterial load, and recently diagnosed disease.

By obtaining EIA data before and after successful antimicrobial chemotherapy or surgery, we could demonstrate that the level of GPL core antibodies reflected disease activity of MAC infection. This result is consistent with our previous study on the level of GPL antibodies in MAC disease (7) and show that a merit of the assay is the ability to monitor disease activity. This finding is important because there is, as yet, no consensus as to when to discontinue chemotherapy for MAC disease (1). To validate the use of the EIA as an appropriate clinical tool for monitoring disease and scheduling treatment, data must be obtained in prospective, large-scale studies of active MAC disease.

The high sensitivity and specificity, combined with the simplicity, safety, and rapidity of obtaining results, point to the possibility that new avenues for serodiagnosis of MAC disease will become available with the introduction of the GPL core-based EIA. Results of serodiagnosis by EIA with MAC-specific GPL core antigen, when used in combination with acid-fast staining of sputum and culture confirmation and analyzed together with clinical, radiographic, and microbiologic criteria, may be a powerful tool for diagnosing MAC disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (Research on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases, Health Sciences Research Grants), Ministry of the Environment (Global Environment Research Fund), Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Osaka City University (Urban Research Project), the United States-Japan Cooperative Medical Science Program against Tuberculosis and Leprosy, and the Grant-in-aid for Community Health and Medical Care from Ichou Association for Promotion of Medical Science.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Thoracic Society. 1997. Diagnosis and treatment of disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Medical Section of the American Lung Association. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 156:S1-S25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aspinall, G. O., D. Chatterjee, and P. J. Brennan. 1995. The variable surface glycolipids of mycobacteria: structures, synthesis of epitopes, and biological properties. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 51:169-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brennan, P. J., and H. Nikaido. 1995. The envelope of mycobacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64:29-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatterjee, D., and K. H. Khoo. 2001. The surface glycopeptidolipids of mycobacteria: structures and biological properties. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 58:2018-2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denner, J. C., A. Y. Tsang, D. Chatterjee, and P. J. Brennan. 1992. Comprehensive approach to identification of serovars of Mycobacterium avium complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:473-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falkinham, J. O., III. 1996. Epidemiology of infection by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 9:177-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitada, S., R. Maekura, N. Toyoshima, N. Fujiwara, I. Yano, T. Ogura, M. Ito, and K. Kobayashi. 2002. Serodiagnosis of pulmonary disease due to Mycobacterium avium complex with an enzyme immunoassay that uses a mixture of glycopeptidolipid antigens. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:1328-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopez-Marin, L. M., N. Gautier, M. A. Laneelle, G. Silve, and M. Daffe. 1994. Structures of the glycopeptidolipid antigens of Mycobacterium abscessus and Mycobacterium chelonae and possible chemical basis of the serological cross-reactions in the Mycobacterium fortuitum complex. Microbiology 140:1109-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maekura, R., H. Kohno, A. Hirotani, Y. Okuda, M. Ito, T. Ogura, and I. Yano. 2003. Prospective clinical evaluation of the serologic tuberculous glycolipid test in combination with the nucleic acid amplification test. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1322-1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maekura, R., Y. Okuda, M. Nakagawa, T. Hiraga, S. Yokota, M. Ito, I. Yano, H. Kohno, M. Wada, C. Abe, T. Toyoda, T. Kishimoto, and T. Ogura. 2001. Clinical evaluation of anti-tuberculous glycolipid immunoglobulin G antibody assay for rapid serodiagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3603-3608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNeil, M., A. Y. Tsang, and P. J. Brennan. 1987. Structure and antigenicity of the specific oligosaccharide hapten from the glycopeptidolipid antigen of Mycobacterium avium serotype 4, the dominant Mycobacterium isolated from patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. J. Biol. Chem. 262:2630-2635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okuda, Y., R. Maekura, A. Hirotani, S. Kitada, K. Yoshimura, T. Hiraga, Y. Yamamoto, M. Itou, T. Ogura, and T. Ogihara. 2004. Rapid serodiagnosis of active pulmonary Mycobacterium tuberculosis by analysis of results from multiple antigen-specific tests. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1136-1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakatani, M. 1999. Nontuberculous mycobacteriosis; the present status of epidemiology and clinical studies. Kekkaku 74:377-384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaefer, W. B. 1965. Serologic identification and classification of the atypical mycobacteria by their agglutination. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 92(Suppl.):85-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tassell, S. K., M. Pourshafie, E. L. Wright, M. G. Richmond, and W. W. Barrow. 1992. Modified lymphocyte response to mitogens induced by the lipopeptide fragment derived from Mycobacterium avium serovar-specific glycopeptidolipids. Infect. Immun. 60:706-711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toida, I. 2000. Development of the Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccine: review of the historical and biochemical evidence for a genealogical tree. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 80:291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsang, A. Y., J. C. Denner, P. J. Brennan, and J. K. McClatchy. 1992. Clinical and epidemiological importance of typing of Mycobacterium avium complex isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:479-484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Reyn, C. F., T. W. Barber, R. D. Arbeit, C. H. Sox, G. T. O'Connor, R. J. Brindle, C. F. Gilks, K. Hakkarainen, A. Ranki, C. Bartholomew, J. Edwards, A. N. A. Tosteson, and M. Magnusson. 1993. Evidence of previous infection with Mycobacterium avium-Mycobacterium intracellulare complex among healthy subjects: an international study of dominant mycobacterial skin test reactions. J. Infect. Dis. 168:1553-1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]