Posttranslational modifications to sarcomeric regulatory proteins provide a mechanism to modulate cardiac function in response to stress. In this study, we demonstrate that neurohormonal stress produces modifications to myosin-binding protein C and troponin I, including a reduction in protein expression within the sarcomere and increased phosphorylation of the remaining protein, which serve to enhance cross-bridge kinetics and increase cardiac output. These findings highlight the importance of sarcomeric regulatory protein modifications in modulating ventricular function during cardiac stress.

Keywords: myosin-binding protein C, troponin I, cardiac contractility, posttranslational modifications

Abstract

Molecular adaptations to chronic neurohormonal stress, including sarcomeric protein cleavage and phosphorylation, provide a mechanism to increase ventricular contractility and enhance cardiac output, yet the link between sarcomeric protein modifications and changes in myocardial function remains unclear. To examine the effects of neurohormonal stress on posttranslational modifications of sarcomeric proteins, mice were administered combined α- and β-adrenergic receptor agonists (isoproterenol and phenylephrine, IPE) for 14 days using implantable osmotic pumps. In addition to significant cardiac hypertrophy and increased maximal ventricular pressure, IPE treatment accelerated pressure development and relaxation (74% increase in dP/dtmax and 14% decrease in τ), resulting in a 52% increase in cardiac output compared with saline (SAL)-treated mice. Accelerated pressure development was maintained when accounting for changes in heart rate and preload, suggesting that myocardial adaptations contribute to enhanced ventricular contractility. Ventricular myocardium isolated from IPE-treated mice displayed a significant reduction in troponin I (TnI) and myosin-binding protein C (MyBP-C) expression and a concomitant increase in the phosphorylation levels of the remaining TnI and MyBP-C protein compared with myocardium isolated from saline-treated control mice. Skinned myocardium isolated from IPE-treated mice displayed a significant acceleration in the rate of cross-bridge (XB) detachment (46% increase) and an enhanced magnitude of XB recruitment (43% increase) at submaximal Ca2+ activation compared with SAL-treated mice but unaltered myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity of force generation. These findings demonstrate that sarcomeric protein modifications during neurohormonal stress are molecular adaptations that enhance in vivo ventricular contractility through accelerated XB kinetics to increase cardiac output.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Posttranslational modifications to sarcomeric regulatory proteins provide a mechanism to modulate cardiac function in response to stress. In this study, we demonstrate that neurohormonal stress produces modifications to myosin-binding protein C and troponin I, including a reduction in protein expression within the sarcomere and increased phosphorylation of the remaining protein, which serve to enhance cross-bridge kinetics and increase cardiac output. These findings highlight the importance of sarcomeric regulatory protein modifications in modulating ventricular function during cardiac stress.

in response to increased cardiac stress, the myocardium undergoes a series of adaptations that modify cardiac output and ventricular contractility through posttranslational modification of cardiac proteins, including enhanced protein phosphorylation, cleavage, and degradation (31, 41, 58). Under physiological conditions, activation of the α- and β-adrenergic signaling pathways in the heart increases sarcomeric protein phosphorylation to modulate cardiac function, but chronic stress or heart failure (HF) can impair normal adrenergic signaling (2). Acute activation of the β-adrenergic signaling pathway enhances sarcomeric protein phosphorylation and increases cardiac contractility in vivo (20), whereas long-term sustained increases in β-adrenergic signaling can have both cardioprotective and cardiotoxic effects during neurohormonal stress (59). Similarly, enhanced α-adrenergic signaling also targets sarcomeric proteins for phosphorylation and has been shown to improve ventricular function and protect against cardiac decompensation during stress (11, 12). Activation of cardiac protein cleavage and degradation pathways, including the calpain-mediated system and the ubiquitin ligase system, produces sarcomeric protein truncation and degradation and leads to removal of proteins from the sarcomere, which is an important step in the regulation of cardiac mass during pathological and neurohormonal stress (1, 31, 41). However, it remains unclear how different posttranslation modifications of cardiac sarcomeric proteins contribute to modify ventricular function during increased neurohormonal stress.

Two important regulatory cardiac sarcomeric proteins that undergo posttranslational modifications following neurohormonal stress are myosin-binding protein C (MyBP-C) and troponin I (TnI). Enhanced α- and β-adrenergic stimulation results in a significant upregulation of various kinases that phosphorylate MyBP-C and TnI to produce a rapid modulation of myocardial contraction and relaxation (4, 5, 46). It is well established that, in vivo, MyBP-C phosphorylation is required to enhance left ventricular (LV) pressure development and relaxation following enhanced adrenergic stimulation, which together with TnI phosphorylation fine tunes the timing of systolic and diastolic function to match systemic demand (20). There is strong evidence that supports a beneficial role of MyBP-C and TnI phosphorylation in maintaining cardiac contractile function, as both have been shown to prevent pathological cardiac decompensation in experimental models of ischemia-reperfusion (I-R) injury (43, 44). Therefore, posttranslational modifications of TnI and MyBP-C could play an important role in maintaining normal cardiac function during neurohormonal stress.

In addition to modifications in MyBP-C and TnI phosphorylation by adrenergic signaling, prolonged stress can also produce MyBP-C and TnI cleavage and degradation through activation of proteolytic pathways (26, 27, 32, 35). Cardiac stress has been shown to induce TnI cleavage that removes the NH2-terminal extension containing PKA-targeted Ser23 and Ser24 (14) and also leads to partial TnI degradation and decreased expression (55, 57), which has been proposed to improve contractile performance during stress (3, 56). Likewise, MyBP-C cleavage has been shown to produce primarily an ~40-kDa NH2-terminal fragment and an ~110-kDa COOH-terminal fragment (17), which promotes subsequent removal and loss of MyBP-C from the thick filament (10), which may help maintain rates of systolic pressure development in vivo (40). However, unlike MyBP-C and TnI phosphorylation, it remains unclear how neurohormonal stress-mediated posttranslational modifications of contractile proteins such as decreased expression modulate in vivo cardiac function.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to quantify the changes in posttranslational modification of sarcomeric proteins attributable to neurohormonal stress and to establish how these changes affect myofilament function and in vivo contractile function and hemodynamics. We utilized a mouse model of neurohormonal stress (chronic α- and β-adrenergic stimulation through continuous isoproterenol and phenylephrine (IPE) administration for 14 days using implanted osmotic pumps) (45) to examine in vivo cardiac contractile function and morphology, left ventricular hemodynamics, myofilament protein phosphorylation and expression, and in vitro mechanical function in detergent-skinned myocardium. Our results demonstrate that neurohormonal stress enhances MyBP-C and TnI phosphorylation and concomitantly decreases MyBP-C and TnI expression, a novel finding that elucidates how posttranslational modifications of MyBP-C and TnI contribute to physiological adaptations that enhance cardiac contractility in conditions of chronic stress.

METHODS

Ethical approval.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 85-23, Revised 1996), and the procedures for anesthesia, surgery, and general care of the animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Case Western Reserve University. Male mice of the SV/129 strain were obtained from Taconic Biosciences.

Model of cardiac stress.

Isoproterenol (β-adrenergic agonist; Sigma-Aldrich; 7.5 µg/g per day) and phenylephrine (α-adrenergic agonist; Sigma-Aldrich; 7.5 µg/g per day) were delivered to male mice (aged 8 wk) for 14 days using implanted microosmotic pumps (Alzet) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Osmotic pumps were filled with IPE dissolved in 0.9% NaCl saline and incubated overnight in 0.9% NaCl at 37°C to ensure proper pump function. Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane (1.5–2.0%), and the pumps were implanted subcutaneously between the scapulae. After 14 days, mice were anesthetized, and hearts were removed, weighed, and flash frozen using liquid nitrogen for determination of protein phosphorylation. Control mice were implanted with osmotic pumps delivering 0.9% NaCl (SAL) for 14 days.

Quantification of sarcomeric protein expression and phosphorylation.

Protein expression and phosphorylation were determined in cardiac myofibril samples using Western blot and Pro-Q Diamond Phosphorylation stain (Life Science) as previously described (19, 34). For Western blot analysis, solubilized myofibrils (5 µg) were transferred to PVDF membranes and incubated overnight with one of the following primary antibodies: total TnI (Cell Signaling Technology), total MyBP-C that detects an NH2-terminal (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or COOH-terminal (21st Century Biochemicals) epitope, MyBP-C phospho-serine 273, 282, or 302 (detects phosphorylation of Ser273, S282, or Ser302 of MyBP-C; 21st Century Biochemicals), or HSC70 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). For analysis of total protein phosphorylation, solubilized myofibrils (2.5 µg) were stained with Pro-Q Diamond, imaged, and counterstained with Coomassie blue stain to detect total protein. Densitometric scanning of stained gels was performed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). To determine whether cleaved sarcomeric proteins were present in the myocardium, ventricular tissue was homogenized in a buffer containing 20.0 mM Tris base, 137.0 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 1.0 mM MgCl2–6 H2O, 1.0 mM (K2)EDTA, 10% glycerol, and 1% Triton X-100, pH 7.8, with protease and phosphatase inhibitors, and homogenized samples were probed using antibodies to detect MyBP-C and TnI protein.

Cardiac contractile function, morphology, and in vivo hemodynamic function.

Cardiac morphology and in vivo cardiovascular function, including stroke volume (SV), fractional shortening (FS), and ejection fraction (EF), were evaluated by echocardiography using a Sequoia C256 system (Siemens Medical) as previously described (19). Left ventricular catheterization using a pressure-conductance catheter was performed to evaluate in vivo hemodynamic function as previously described (19). A baseline recording was made after stabilization of ventricular pressure and heart rate (HR), after which the inferior vena cava was transiently occluded to determine preload-independent measures of contractility. P-V loop analysis was performed offline using LabChart7 software (AD Instruments).

Preparation of skinned myocardial preparations and Ca2+ solutions for experiments.

Skinned myocardial preparations were prepared from SAL and IPE hearts as described previously (19). Detergent-skinned multicellular ventricular preparations of uniform shape and measuring ~100 µm in width and ~400 µm in length were mounted between a motor arm (312C; Aurora Scientific) and a force transducer (403A; Aurora Scientific), and changes in motor position and signals from the force transducer were sampled at 2,000 Hz using a custom-made software program (7). The composition of the various Ca2+ activation solutions used in the experiments was calculated using a computer program (13) and using established stability constants (16). All solutions contained the following (in mM): 14.50 creatine phosphate, 7.00 EGTA, and 20.00 imidazole. The maximal activating solution (i.e., pCa 4.5) also contained 65.45 KCl, 7.01 CaCl2, 5.27 MgCl2, and 4.81 ATP, whereas the relaxing solution (i.e., pCa 9.0) contained 72.45 KCl, 0.02 CaCl2, 5.42 MgCl2, and 4.76 ATP. The pH of the Ca2+ solutions was set to 7.0, and the ionic strength was 180 mM. All the experiments were carried out at 23°C.

Measurement of mechanical function in skinned myocardial preparations.

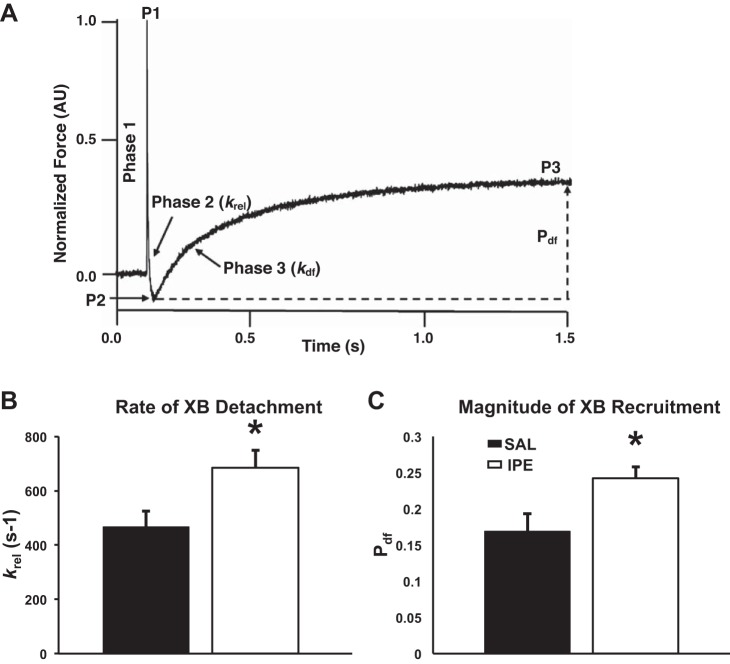

To measure dynamic myocardial cross-bridge (XB) behavior, skinned myocardial preparations with a sarcomere length (SL) of 2.1 µm were placed in Ca2+ solutions (pCa 6.1) that generate ~35% of the maximal force and were rapidly stretched by 2% of their initial muscle length as previously described (19, 33, 49). The key features of the cardiac stretch activation response are shown in Fig. 7A. In brief, a sudden 2% stretch in muscle length causes an instantaneous spike in the force response (P1) because of the sudden strain of elastic elements within the strongly bound XBs (phase 1). The force then rapidly decays (phase 2) attributable to the detachment of the strained XBs into a non-force-bearing state, with a dynamic rate constant krel. The lowest point of phase 2 is indicated by P2 and is an index of the magnitude of XB detachment. Following phase 2, the preparations exhibit a gradual rise in force (phase 3, with a dynamic rate constant kdf) attributable to sudden stretch-induced recruitment of additional XBs into the force-bearing state. P3 was measured from prestretch steady-state force to the peak force value attained in phase 3, whereas Pdf was measured as the difference between P3 and P2 values. krel was measured by fitting a single exponential equation to the time course of force decay using the following equation: F(t) = a(-1 + exp[-krel*t)], where a is the amplitude of the single exponential phase and krel is the rate constant of the force decay. kdf was estimated by linear transformation of the half-time of force redevelopment, i.e., kdf = 0.693/t1/2, where t1/2 is the time (in milliseconds) taken from P2 to the point of half maximal force in phase 3.

Fig. 7.

Effect of IPE treatment on stretch-activation parameters. A: representative stretch-activation responses elicited at ~35% of maximal Ca2+ activation level following a sudden 2% stretch in muscle length in an isometrically contracting SAL-skinned myocardial preparation. In A, the key features of the force response elicited following an imposed stretch are highlighted (see methods for details). Effects of IPE treatment on the rate of XB detachment, krel (B), and on the magnitude of XB recruitment (Pdf) (C) are shown. IPE treatment significantly accelerated krel and enhanced the Pdf (values shown in Table 4). Values are expressed as means ± SE for 12 myocardial preparations from 4 SAL hearts, and 14 preparations from 4 IPE hearts were analyzed, with multiple preparations from each heart. *Significantly different from SAL, P < 0.05.

Statistical analysis.

Comparisons between SAL- and IPE-treated groups were performed using a Student’s t-test. All data are presented as means ± SE. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

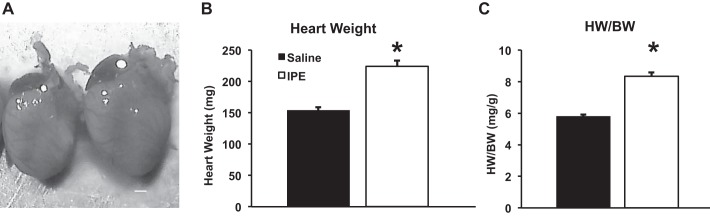

Assessment of cardiac hypertrophy.

To examine the posttranslational modifications of myofilament proteins following neurohormonal stress, 8-wk-old male mice were continuously infused with a combination of α- and β-adrenergic agonists (IPE) for 14 days using implanted osmotic pumps. Overall cardiac morphology was examined to determine whether IPE treatment produced pathological remodeling. Representative IPE- and SAL-treated hearts are shown in Fig. 1A, demonstrating an increase in heart size following IPE treatment. IPE treatment significantly increased cardiac mass (224.0 ± 9.1 mg) compared with SAL control mice (155.4 ± 4.8 mg) and increased heart weight-to-body weight (HW/BW) ratio (5.9 ± 0.1 mg/g for SAL, 8.4 ± 0.2 mg/g for IPE; Fig. 1). When examined by echocardiography, IPE-treated mice exhibited an enlarged left ventricle and increased left ventricular wall thickness compared with SAL-treated mice (Table 1), confirming cardiac hypertrophy.

Fig. 1.

Isoproterenol and phenylephrine (IPE) treatment induces cardiac hypertrophy and ventricular remodeling. After 14 days of IPE treatment, hearts were excised, weighed, and imaged. A: representative hearts from saline (SAL)-treated (solid bar) and IPE-treated (open bar) mice demonstrating the overall increase in heart size in IPE-treated mice. Scale bar = 1 mm. IPE treatment significantly increased heart weight (HW) (B) and heart weight normalized to body weight (BW) (C) compared with SAL-treated mice. Values are expressed as means ± SE from 9 (SAL) and 16 (IPE) mice. *Significantly different from SAL, P < 0.05.

Table 1.

LV morphology and in vivo cardiac performance measured by echocardiography

| SAL | IPE | |

|---|---|---|

| BW, g | 27.10 ± 0.60 | 28.70 ± 1.10 |

| LV mass/BW | 3.60 ± 0.10 | 4.30 ± 0.20* |

| AWd, mm | 0.72 ± 0.02 | 0.82 ± 0.02* |

| AWs, mm | 1.03 ± 0.02 | 1.13 ± 0.03* |

| EDV, µl | 58.20 ± 2.40 | 73.50 ± 4.20* |

| ESV, µl | 16.80 ± 1.90 | 19.60 ± 2.90 |

| SV, µl | 41.30 ± 2.00 | 53.90 ± 2.70* |

| HR, beats/min | 406.00 ± 7.00 | 447.00 ± 14.00* |

| FS, % | 34.50 ± 1.90 | 37.30 ± 2.70 |

| EF, % | 71.30 ± 2.50 | 74.10 ± 3.00 |

Values are expressed as means ± SE from 8 saline-treated (SAL) and 9 isoproterenol and phenylephrine-treated (IPE) mice.

Significantly different from SAL, P < 0.05. LV, left ventricular;

BW, body weight; LV mass/BW, ratio of LV and body weight; AWd, anterior wall thickness in diastole; AWs, anterior wall thickness in systole; EDV, end-diastolic volume; ESV, end-systolic volume; SV, stroke volume; HR, heart rate; FS, fractional shortening; EF, ejection fraction.

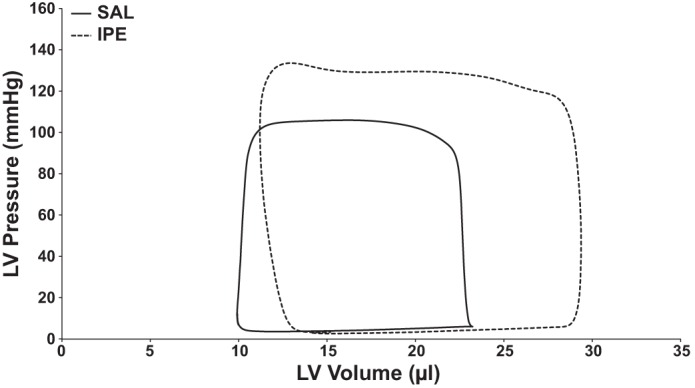

In vivo cardiac function.

To determine the effects of IPE treatment on cardiac contractile function and hemodynamics, function in IPE-treated mice was assessed by echocardiography and P-V loops (Tables 1 and 2). Cardiac output was increased by 52% in IPE-treated mice compared with SAL-treated mice (Table 2), which was caused by increased HR and ventricular SV. IPE treatment increased SV by 31% (assessed by echocardiography) and 21% (assessed by P-V loops), but, because of the fact that end-diastolic volume (EDV) was also increased, there was no change in EF (Tables 1 and 2). Even though IPE treatment increased HR, ejection time was not significantly altered by IPE treatment (33 ± 1 ms and 35 ± 2 ms for IPE and SAL, respectively) even when accounting for the shorter duration of the cardiac cycle in IPE mice (29 ± 1% and 26 ± 1% of the cardiac cycle for IPE and SAL, respectively; P = 0.12). These results indicate that IPE treatment increased SV by accelerating ventricular ejection, most likely by enhancing myocardial contraction.

Table 2.

Left ventricular hemodynamic function measured by P-V loop analysis

| SAL | IPE | |

|---|---|---|

| Pmax, mmHg | 101.7 ± 2.7 | 129.9 ± 5.4* |

| EDP, mmHg | 5.0 ± 0.4 | 6.6 ± 0.5* |

| dP/dtmax, mmHg/s | 6,940.0 ± 463.0 | 12,074.0 ± 593.0* |

| dP/dtmin, mmHg/s | −7,810.0 ± 549.0 | −10,736.0 ± 626.0* |

| τ, ms | 8.0 ± 0.4 | 6.8 ± 0.4* |

| EDV, µl | 20.9 ± 2.0 | 28.9 ± 2.7* |

| SV, µl | 11.8 ± 1.1 | 14.3 ± 2.5* |

| EF, % | 58.1 ± 5.0 | 57.9 ± 5.3 |

| HR, beats/min | 449.0 ± 13.0 | 521.0 ± 23.0* |

| Powermax, mmHg·µl/s | 1,518.0 ± 162.0 | 2,517.0 ± 251.0* |

| CO, µl/min | 5,371.0 ± 588.0 | 8,169.0 ± 444.0* |

| PER, µl/s | 15.3 ± 1.3 | 20.8 ± 2.0* |

| Ea, mmHg/µl | 9.3 ± 1.5 | 8.4 ± 0.8 |

Values are expressed as means ± SE from 8 SAL and 9 IPE mice.

Significantly different from SAL, P < 0.05. Pmax, maximum systolic pressure;

EDP, end-diastolic pressure; dP/dtmax, maximum rate of pressure development; dP/dtmin, maximum rate of pressure relaxation; τ, time constant of pressure relaxation; Powermax, maximum power; CO, cardiac output; PER, peak ventricular ejection rate (normalized to EDV); Ea, arterial elastance.

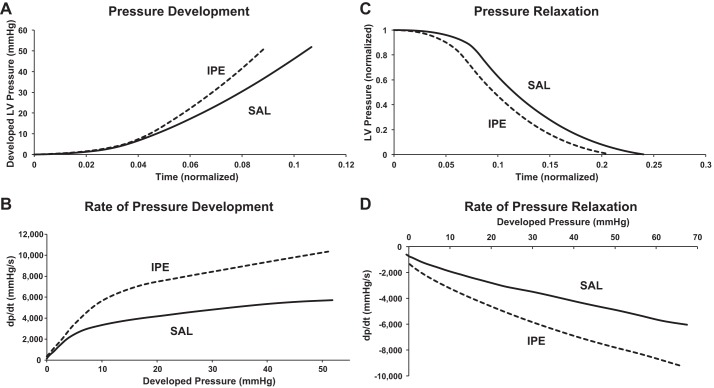

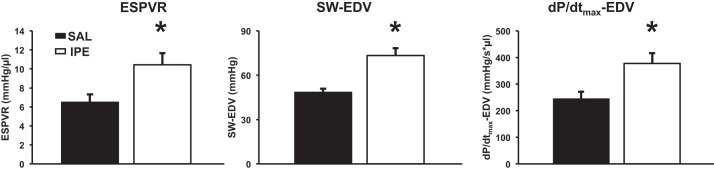

We next sought to determine whether the increase in SV that boosts cardiac output following IPE treatment was due to an increase in LV contractility (Fig. 2). Figure 3A shows representative pressure traces, and Fig. 3B shows the rate of pressure development plotted against developed pressure during isovolumic contraction. IPE treatment significantly accelerated the rate of pressure development during early systole, as reflected by an increased maximum rate of pressure development (dP/dtmax; Table 2) and a leftward shift in the pressure trace. The accelerated pressure development in IPE hearts was observed throughout isovolumic contraction (Fig. 3B), suggesting that IPE treatment accelerated pressure development by increasing ventricular contractility. Enhanced ventricular contraction after IPE treatment was also reflected by an increase in maximal ventricular power generated during ejection and an increase in the rate of ventricular blood ejection (Table 2). Taken together, these results demonstrate that IPE treatment resulted in augmented ventricular contraction and increased cardiac contractility during systole to maximize blood ejection and increase cardiac output.

Fig. 2.

Representative pressure-volume (P-V) loops. Representative P-V loops from IPE-treated (dashed line) and SAL-treated (solid line) mice. Representative loops were averaged from at least 10 P-V loops once a stable baseline had been achieved. LV, left ventricular.

Fig. 3.

Representative pressure development and relaxation traces from an IPE-treated mouse and a SAL-treated mouse. A: early LV pressure development in systole is accelerated in IPE-treated mice (dashed trace) compared with SAL-treated (solid trace) mice. B: rate of pressure development plotted against developed pressure before the onset of ejection. IPE-treated mice displayed an increased rate of pressure development compared with SAL-treated mice. C: LV pressure relaxation in diastole is accelerated in IPE-treated mice (dashed trace) compared with SAL-treated (solid trace) mice. Because IPE treatment increased maximum ventricular developed pressure, maximum pressure was set to 1 to facilitate comparison between IPE and SAL mice. D: rate of pressure relaxation plotted against developed pressure. IPE treatment accelerated pressure relaxation during diastole compared with SAL treatment. For A and C, time was normalized to cardiac cycle duration to account for changes in heart rate (HR).

According to the Frank-Starling law of the heart, an increase in ventricular preload (increased EDV) enhances systolic contraction. Because IPE treatment increased EDV, preload independent measures of ventricular contractility were examined by transient inferior vena cava occlusion (Fig. 4). IPE treatment increased the slope of the end-systolic pressure-volume relationship (i.e., end-systolic pressure-volume relationship), increased preload-recruitable SV, and increased preload-adjusted maximum rate of pressure development, indicating that enhanced ventricular contractility produced by IPE treatment is independent of changes in LV preload.

Fig. 4.

Preload independent measures of LV contractility. Transient preload reduction achieved by inferior vena cava occlusion demonstrated enhanced preload-independent cardiac contractility in IPE-treated mice. In each case, the increase in the slope of the relationship in IPE-treated mice reflects an enhancement in systolic function. Values are expressed as means ± SE from 7 (SAL) and 8 (IPE) mice. *Significantly different from SAL, P < 0.05. ESPVR, end-systolic pressure-volume relationship; SW-EDV, preload-recruitable stroke work; dP/dtmax-EDV, preload-adjusted maximal rate of pressure development.

In addition to enhancing systolic function, IPE treatment also sped pressure relaxation during diastole. Figure 3C shows representative pressure relaxation traces during diastole (normalized to maximum pressure to facilitate comparisons between groups), and Fig. 3D shows the rate of pressure relaxation plotted against developed pressure during isovolumic relaxation. IPE treatment increased ventricular pressure relaxation as demonstrated by a leftward shift in the pressure trace and an increase in the maximum rate of pressure relaxation (dP/dtmin was more negative in IPE mice) and a decrease in the pressure relaxation time constant (τ; Table 2). IPE treatment accelerated pressure relaxation throughout isovolumic relaxation (Fig. 3B), suggesting that the enhanced contractility observed in systole also enhanced ventricular relaxation. Taken together, these results suggest that IPE treatment increases cardiac output by enhancing LV contractility to speed pressure development and relaxation.

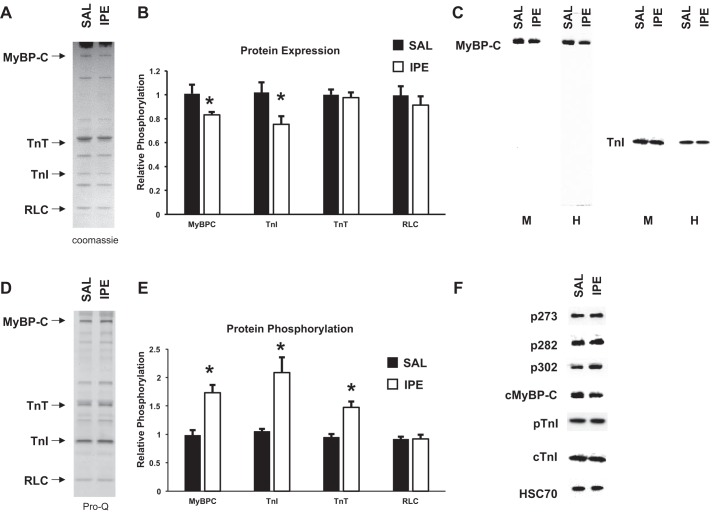

Quantification of myofilament protein expression and phosphorylation.

Myofilament protein expression and phosphorylation were examined in ventricular myofibril samples from IPE- and SAL-treated mice to examine sarcomeric protein posttranslational modifications following IPE treatment (Fig. 5). Myofibrils isolated from IPE-treated mice displayed a reduction in MyBP-C and TnI protein levels within the sarcomere compared with SAL myofibrils when examined by both Western blot and Coomassie staining (Fig. 5). There were no changes in the expression of other regulatory contractile proteins within the sarcomere, including regulatory light chain (RLC) and troponin T (TnT) (Fig. 5B). Whole cell ventricular homogenates were also probed with MyBP-C and TnI antibodies (Fig. 5C) and also showed reduced MyBP-C and TnI protein levels in IPE samples, confirming that MyBP-C and TnI expression is reduced following IPE treatment. However, in both ventricular myofibril and whole cell homogenate samples, MyBP-C and TnI protein were only detected at molecular weights corresponding to full-length protein (~140 and 30 kDa, respectively) with no truncated proteins detected at lower molecular weights (Fig. 5C). Western blot using an antibody to detect the NH2-terminal region of MyBP-C also showed reduced MyBP-C expression and only recognized the full-length MyBP-C band (no truncated protein detected; data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Determination of troponin I (TnI) and myosin-binding protein C (MyBP-C) expression and phosphorylation. A: representative Coomassie-stained cardiac myofibrils from SAL and IPE mice showing total protein expression. B: quantification of regulatory protein expression from Coomassie-stained myofibrils. IPE-treated myofibrils displayed decreased MyBP-C and TnI expression with no change in troponin T (TnT) and regulatory light chain (RLC) expression. Myofibrils were isolated from 3 (SAL) and 6 (IPE) hearts. C: representative Western blots of SAL and IPE cardiac samples demonstrating MyBP-C and TnI expression in myofibril (M) or whole cell homogenate (H) samples (M and H samples were run on separate Westerns). MyBP-C and TnI expression was reduced following IPE treatment, and only full-length protein was detected. D: representative Pro-Q-stained cardiac myofibrils from SAL and IPE mice showing protein phosphorylation. E: quantification of regulatory protein phosphorylation (normalized to protein expression) from Pro-Q-stained myofibrils. IPE-treated myofibrils displayed increased MyBP-C, TnI, and TnT phosphorylation but unchanged RLC phosphorylation. F: representative Western blots of SAL and IPE cardiac myofibrils demonstrating MyBP-C (Ser273, Ser282, or Ser302) and TnI (Ser23/24) phosphorylation. Phosphorylation of the remaining MyBP-C and TnI protein was increased at PKA-targeted residues by IPE treatment. *Significantly different from SAL, P < 0.05.

Pro Q Diamond phosphostaining revealed that IPE treatment significantly increased MyBP-C and TnI phosphorylation compared with SAL samples (Fig. 5, D and E). To determine which residues were phosphorylated during neurohormonal stress, we examined MyBP-C and TnI phosphorylation at PKA-targeted residues by Western blot (Fig. 5A). IPE treatment significantly increased the levels of MyBP-C Ser273, Ser282, and Ser302 and TnI Ser23/24 phosphorylation in the remaining MyBP-C and TnI protein compared with SAL control samples, demonstrating enhanced MyBP-C and TnI phosphorylation at PKA-targeted residues. TnT phosphorylation levels were also increased following IPE treatment, but RLC phosphorylation levels were not different compared with SAL controls (Fig. 5E). Taken together, these results demonstrate that IPE treatment significantly reduces the expression levels of MyBP-C and TnI in the sarcomere while also increasing the phosphorylation of the remaining MyBP-C and TnI.

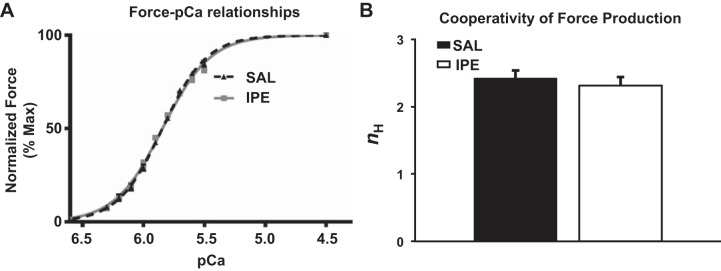

Measurement of steady-state mechanical properties in skinned myocardium.

To determine the functional impact of IPE-mediated myofilament changes in expression and phosphorylation on cardiac thin-filament activation, steady-state Ca2+ activated force was measured over a range of [Ca2+] in skinned myocardial preparations isolated from IPE and SAL hearts. Maximal Ca2+-activated force production, i.e., Fmax (measured at pCa 4.5), was not significantly different between SAL and IPE groups (Table 3), indicating that IPE treatment does not impact thin-filament activation at maximal [Ca2+]. Similarly, there was no difference in minimal force generation, i.e., Fmin (measured at pCa 9.0) between SAL and IPE groups (Table 3). The effect of IPE treatment on myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity was assessed by plotting normalized forces generated against a range of [Ca2+] and constructing the force-pCa relationships (Fig. 6A). The pCa required to generate half-maximal force (pCa50), was estimated by fitting the Hill equation to the force-pCa relationships (Table 3). There were no differences in pCa50 between IPE and SAL preparations (Fig. 6A and Table 3), demonstrating that IPE treatment did not significantly alter the responsiveness of the cardiac myofilaments to Ca2+. The cooperativity of force production (nH) was similar between IPE and SAL preparations (Fig. 6B and Table 3), demonstrating that IPE treatment did not significantly alter the apparent cooperativity of force production during Ca2+-mediated activation of the thin filaments.

Table 3.

Steady-state contractile parameters in SAL- and IPE-skinned myocardial preparations

| Group | pCa50 | nH | Fmax, mN/mm2 | Fmin, mN/mm2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAL | 5.84 ± 0.01 | 2.42 ± 0.12 | 18.30 ± 2.30 | 1.29 ± 0.19 |

| IPE | 5.84 ± 0.01 | 2.31 ± 0.13 | 20.01 ± 2.01 | 0.95 ± 0.10 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SE. 12 preparations were analyzed from 4 SAL hearts, and 18 preparations were analyzed from 6 IPE hearts with multiple preparations from each heart. No significant differences in the steady-state contractile measurements were observed between SAL and IPE groups. pCa50, myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity; nH, cooperativity of force production; Fmax, maximal Ca2+-activated force measured at pCa 4.5; Fmin, Ca2+-independent force measured at pCa 9.0.

Fig. 6.

Effect of IPE treatment on myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity (pCa50) and cooperativity of force production (nH). Force-pCa relationships were constructed by plotting normalized forces generated by incubating the SAL- and IPE-skinned myocardial preparations in a range of pCa. The Hill equation was then fitted to the force-pCa relationships to estimate pCa50 and nH values in SAL and IPE groups. A: force-pCa relationships in SAL- and IPE-skinned myocardial preparations. B: cooperativity of force production (nH) in SAL- and IPE-skinned myocardial preparations. IPE treatment did not significantly impact the pCa50 as indicated by absence of shifts in the force-pCa relationship in the IPE group compared with the SAL group (values are shown in Table 3). Furthermore, IPE treatment did not impact the apparent cooperativity of force production, indicating that the cooperative cross-bridge (XB) recruitment into the force-bearing state is not altered by IPE treatment. 12 myocardial preparations were analyzed from 4 SAL hearts, and 18 myocardial preparations were analyzed from 6 IPE hearts, with multiple preparations from each heart.

Measurement of dynamic XB kinetics in skinned myocardium.

We performed stretch-activation experiments in skinned myocardium to assess the impact of IPE treatment on dynamic XB function (Table 4). krel was significantly accelerated by ~46% in the IPE group (Table 4 and Fig. 7B), indicating that the rate of XB detachment from the thin filaments was significantly accelerated following IPE treatment. Additionally, we observed negative P2 values in IPE-skinned myocardium compared with P2 values observed in SAL-skinned myocardium (Table 4), indicating a significant enhancement in the magnitude of XB detachment following IPE treatment. Whereas kdf, an index of the rate of XB recruitment, was not different between SAL and IPE groups (Table 4), the magnitude of XB recruitment represented by amplitude of delayed force development (Pdf) during the stretch-activation response was increased by ~43% following IPE treatment compared with SAL treatment (Table 4 and Fig. 7C). Collectively, our data show that both the rate and magnitude of XB detachment are significantly enhanced following IPE treatment and that IPE treatment enhances the magnitude of cooperative XB recruitment into the force-bearing state without affecting the rate of XB recruitment.

Table 4.

Dynamic contractile parameters in SAL- and IPE-skinned myocardial preparations

| Group | pCa | P1 (P1/P0) | P2 (P2/P0) | P3 (P3/P0) | krel, per s | kdf, per s | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAL | 6.100 | 0.564 ± 0.049 | 0.052 ± 0.018 | 0.221 ± 0.011 | 0.169 ± 0.024 | 467.110 ± 57.340 | 5.460 ± 0.680 |

| IPE | 6.100 | 0.594 ± 0.014 | −0.027 ± 0.012* | 0.225 ± 0.013 | 0.252 ± 0.014* | 684.140 ± 64.520* | 4.360 ± 0.340 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SE. 12 preparations were analyzed from 4 SAL hearts, and 14 preparations were analyzed from 4 IPE hearts with multiple preparations from each heart.

P < 0.05,

significantly different from SAL. P1, cross-bridge (XB) stiffness; P2, minimum force attained at the end of phase 2 of the stretch-activation response, an index of the magnitude of XB detachment; P3, the new steady-state force attained in response to the imposed stretch in muscle length, an index of force enhancement above initial prestretch isometric levels; Pdf, the trough-to-peak amplitude of the delayed force development phase (phase 3), an index of the magnitude of overall poststretch XB recruitment; P0, prestretch isometric force; krel, rate of XB detachment into the non-force-bearing state; kdf: rate of delayed XB recruitment into the force-bearing state in phase 3.

DISCUSSION

Posttranslational MyBP-C and TnI modifications during neurohormonal stress.

Cleavage and degradation of cardiac sarcomeric proteins are essential steps in the hypertrophic process and have previously been shown to be required for cardiac hypertrophy during neurohormonal stress (31, 41). Additionally, degradation and loss of MyBP-C and TnI during stress have been reported to affect myocardial contractility (14, 24, 32). However, the functional effects of reduced expression of MyBP-C and TnI on myofilament function and ventricular hemodynamics are not entirely clear. In this study, we show that, in response to chronic adrenergic stress, a decrease in MyBP-C and TnI expression (~80% and ~75% of SAL-treated samples, respectively; Fig. 5) in the sarcomere was observed, but no protein fragments were detected within the myocardium (Fig. 5). This reduction in protein expression occurred concurrently with an increase in heart size, indicating cardiac hypertrophy (~40% increase in cardiac mass and HW/BW ratio; Fig. 1), suggesting that reduced protein expression could be part of the hypertrophic response to chronic adrenergic stress. The reduction in protein expression in this IPE stress model appears to be specific to MyBP-C and TnI, as expression of other myofilament proteins was similar between IPE-treated and SAL-treated myocardium. Inhibition of protein degradation leads to cardiovascular decompensation and cardiac dysfunction after 1 wk of transaortic constriction (52), suggesting that the combination of reduced TnI and MyBP-C expression with enhanced phosphorylation serves as sarcomeric adaptations to enhance cardiac output during stress.

In contrast to previous studies examining sarcomeric protein posttranslational modifications during cardiac stress (18, 44), we did not observe truncated protein in the myocardium of IPE-treated mice. Although the reason for these divergent findings is unclear, the type of stress model used may be an important determinant of whether truncated proteins are incorporated in the sarcomere or are removed from the myocardium, as previous studies that detected truncated proteins in the myocardium have used I-R injury as a stress model (18, 44). Additionally, in this study, we examined sarcomeric protein expression after 14 days of IPE treatment as opposed to 24 h after I-R injury (18, 44). Our results here do not rule out the possibility that truncated sarcomeric proteins can remain incorporated within the sarcomere following acute and severe cardiac injury; however, it appears that, in milder and more prolonged cardiac stress, truncated and/or degraded contractile proteins are removed from the sarcomere, resulting in an overall decrease in total sarcomeric protein expression.

In addition to protein degradation, MyBP-C and TnI have been reported to be dephosphorylated in response to prolonged stress and in chronic HF, which is linked to cardiac decompensation and pathological cardiac hypertrophy (10, 22, 23). However, in this study, we observed an increase in MyBP-C and TnI phosphorylation at the PKA-targeted residues (Ser273, Ser282, and Ser302 in MyBP-C and Ser23 and Ser24 in TnI) when normalized to total protein expression (Fig. 5), suggesting that the initial response to neurohormonal stress produced by IPE treatment enhances β-adrenergic signaling. The fact that we observed enhanced myofilament protein phosphorylation, whereas other studies using chronic β-adrenergic stimulation observed a downregulation of β-adrenergic signaling, is most likely due to the concentration of β-adrenergic agonist used in this study (7.5 µg/g per day), which was significantly lower than other studies that reported desensitization (30 µg/g per day) (30).

Effects of IPE stress on in vitro contractile function.

MyBP-C is a critical regulator of force generation through its phosphorylation-dependent interactions with myosin and actin. PKA-mediated MyBP-C phosphorylation releases a restraint on the myosin heads to promote actomyosin interactions (9, 21) and increases XB compliance, which together accelerate both the rates and magnitude of XB recruitment and detachment (49, 50, 53). Decreased MyBP-C expression in the sarcomere also results in enhanced rates and magnitude of XB recruitment and detachment, suggesting similar molecular mechanisms to MyBP-C phosphorylation (8, 48, 50). Additionally, the NH2-terminal region of MyBP-C has been shown to bind to actin and displace tropomyosin from the closed to open position (28, 39), which would increase actomyosin interaction and enhance force generation. Our results show that skinned myocardium isolated from IPE-treated hearts displayed an enhancement in the rate of XB detachment (i.e., krel) and magnitude of XB recruitment (i.e., Pdf) compared with skinned myocardium isolated from SAL-treated hearts. Because XB detachment is the rate-limiting step in XB cycling in the two-state XB model, an acceleration in the rate of XB detachment would enhance the overall rate of XB turnover, thereby accelerating myocardial pressure generation during isovolumic contraction (25). Enhanced XB detachment would also accelerate thin-filament deactivation at the end of systole to enhance ventricular relaxation (6). Enhanced XB detachment can act to reduce force generation; however, in our study, we did not observe changes in maximal forces and myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity, which is likely due to the fact that our measurements of XB kinetics were obtained well below the half-maximal pCa (pCa 6.1), and it was shown recently that, as Ca2+ levels increase, the effects of MyBP-C phosphorylation and expression become less pronounced and completely abolished at maximal Ca2+ activation (42, 49).

PKA-mediated MyBP-C phosphorylation accelerates the rate of cooperative XB recruitment (kdf) to accelerate force development following a rapid stretch and increases the magnitude of force development by enhancing XB recruitment into force-generating states (33, 49, 53). In our study, we did not observe accelerations in kdf, which may be due to an increase in the phosphorylation of TnT (Fig. 5E), as PKC phosphorylation of TnT has been shown to slow the rate of XB recruitment kinetics (36, 37), which may counteract the acceleration in kdf attributable to PKA-mediated phosphorylation of MyBP-C. Although we did not observe changes kdf in IPE-skinned myocardium, IPE treatment did enhance the magnitude of XB recruitment (Pdf) following a rapid-stretch maneuver (Table 4 and Fig. 7), suggesting that more XBs are recruited into the force-generating states following neurohormonal stress. Enhanced XB detachment and XB turnover increase the number of open binding sites on actin such that additional XBs can be recruited (i.e., enhanced Pdf) without a concomitant acceleration of kdf. The enhanced Pdf would then be expected to increase the number of force-generating XBs during systole, which together with enhanced Ca2+ released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) augments LV pressure as observed in the IPE-treated mice (Table 2).

In response to β-adrenergic stimulation, PKA-mediated phosphorylation of TnI reduces the affinity of TnC to Ca2+ and decreases thin-filament Ca2+ sensitivity of force generation (15, 47), resulting in accelerated thin-filament deactivation that speeds myocardial relaxation. In addition, a significant reduction in TnI expression may be expected to increase the amount of unregulated force at very low Ca2+ levels attributable to reduced TnI-mediated inhibitory effects on contractile function. However, in this study, the relatively small ~25% decrease in TnI expression attributable to IPE stress was not sufficient to result in unregulated force generation (Table 3). Furthermore, the loss the NH2-terminal extension of TnI containing the PKA phosphorylation residues results in accelerated cardiomyocyte shortening velocity and in vivo ventricular relaxation, similar to the effects of β-adrenergic stimulation (3, 56). Therefore, it is possible that increased phosphorylation coupled with an ~25% loss of TnI (including the NH2-terminal extension) contributed to an enhanced rate and magnitude of XB detachment in IPE-treated skinned myocardium. Whereas the combined effects of reduced expression levels of MyBP-C and TnI and increased phosphorylation did not alter in vitro thin-filament Ca2+ sensitivity in IPE-treated myocardium, altered Ca2+ dynamics attributable to accelerated HR would be expected to influence ventricular function in vivo. Thus increased HR observed after IPE treatment most likely reflects increased ryanodine receptor and phospholamban phosphorylation, which would be expected to speed Ca2+ release and reuptake from the SR, leading to faster rates in ventricular pressure rise and relaxation. Rapid removal of Ca2+ from the cytoplasm would accelerate Ca2+ release from the troponin complex to promote thin-filament deactivation and, in combination with enhanced XB detachment, speed ventricular relaxation.

Sarcomeric adaptations to stress enhance ventricular pressure development and relaxation.

IPE treatment increased the maximal and submaximal rates of pressure development during early systole, which was reflected by a leftward shift in the pressure trace (Fig. 3). The leftward shift in the pressure trace was maintained even when normalized to the duration of the cardiac cycle, demonstrating that IPE treatment enhances ventricular contractility independent of changes in HR. Additionally, the preload-adjusted maximal rate of pressure development was increased by IPE treatment, demonstrating that ventricular contractility is increased independent of changes in preload. These findings most likely reflect a dependence on sarcomeric adaptations that enhance XB cycling kinetics and XB recruitment to accelerate pressure development and enhance cardiac output during neurohormonal stress. We have previously shown that increased MyBP-C phosphorylation in response to PKA treatment accelerates XB kinetics to speed pressure development in response to acute β-adrenergic signaling (20, 33), and a reduction in MyBP-C expression coupled with enhanced phosphorylation would be expected to have a similar effect because of enhanced actomyosin interaction following the removal of MyBP-C protein. Because reduced MyBP-C and TnI expression have been proposed to mimic the ionotropic effects of PKA-mediated phosphorylation (3, 20, 34, 56), these sarcomeric adaptations (i.e., reduced expression in concert with enhanced phosphorylation) would be expected to contribute to enhanced pressure generation during cardiac stress. Furthermore, increased Ca2+ release from the SR stores during isovolumetric contraction following IPE treatment (as reflected by an increased HR) would also contribute to faster pressure development observed in vivo.

The acceleration in XB detachment following MyBP-C phosphorylation speeds ventricular relaxation following β-adrenergic stimulation (20), whereas increased TnI phosphorylation would also contribute to enhanced thin-filament deactivation during late systole (29, 50), thereby speeding ventricular pressure decay (51). Because a reduction in expression of these proteins may be expected to mimic the effects of protein phosphorylation, decreased TnI and MyPB-C expression would also be expected to accelerate ventricular relaxation although this needs further investigation in vivo. In this study, IPE-treated mice showed an acceleration in the maximal and submaximal rates of pressure relaxation (Table 2 and Fig. 3), which resulted in a leftward shift in the ventricular pressure trace. This enhanced relaxation corresponded with an acceleration in the rate of ventricular filling (425 ± 29 µl/s for IPE compared with 316 ± 29 µl/s for SAL; P < 0.05). Taken together, enhanced pressure development to increase ejection rate and accelerated pressure relaxation to increase filling rate combine to enhance cardiac output during neurohormonal stress.

Although maximum ventricular pressure is controlled by a number of factors, including preload, afterload, and thin-filament activation (25), it is proportional to the number of strongly bound myosin heads generating force. We recently showed that MyBP-C phosphorylation regulates in vivo maximum systolic pressure generation (20), most likely by increasing the rate and/or magnitude of XB recruitment and the spread of thin-filament activation (38, 54), thereby regulating the number of strongly bound force-generating XBs during systole. Similarly, here we observed a partial loss of MyBP-C that contributed to an enhanced magnitude of XB recruitment, which would be expected to increase the number of force-generating XBs during systole to augment LV pressure, as was observed in IPE-treated mice (Table 2). Therefore, the sarcomeric adaptations observed following IPE treatment most likely contribute to increased pressure generation during neurohormonal stress.

Adaptation or maladaptation.

Whereas MyBP-C and TnI phosphorylation and reduced expression may be physiological adaptations to enhance cardiac output in the short term, long-term maintenance of these sarcomeric adaptations could ultimately be deleterious to cardiac function. For example, chronic MyBP-C deficiency results in accelerated XB kinetics but ultimately produces cardiac hypertrophy and ventricular dysfunction (8, 40, 48). The initial sarcomeric modifications that enhance cardiac function in response to neurohormonal stress may provide an acute boost to ventricular function while being deleterious to cardiac function if maintained for longer periods of time. In this model of neurohormonal stress, MyBP-C and TnI expression is reduced, with no detectable truncated protein fragments that could directly affect myocardial function. The remaining MyBP-C and TnI proteins in the sarcomere are more heavily phosphorylated in IPE-treated hearts compared with SAL-treated hearts. Together, these adaptations enhance XB detachment and the magnitude of XB recruitment to speed ventricular contraction and relaxation, which allows for increased cardiac output during severe stress. These results suggest that enhanced posttranslational modifications of MyBP-C and TnI in conditions of cardiac stress are critical for maintaining cardiac output, whereas reduced MyBP-C and TnI modifications in chronic HF would be expected to result in depressed systolic and diastolic cardiac function.

GRANTS

This work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (HL-114770 and P30CA043703) and the American Heart Association (16POST30730000).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.S.G. and J.E.S conceived and designed research; K.S.G., R.M., J.L., H.K., and J.E.S. performed experiments; K.S.G., R.M., J.L., H.K., and J.E.S. analyzed data; K.S.G., R.M., J.L., H.K., and J.E.S. interpreted results of experiments; K.S.G., R.M., and J.E.S. prepared figures; K.S.G. and J.E.S. drafted manuscript; K.S.G., R.M., J.L., H.K., and J.E.S. edited and revised manuscript; K.S.G., R.M., J.L., H.K., and J.E.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Xiaoqin Chen, M.D., Department of Physiology and Biophysics at Case Western Reserve University, for assistance with echocardiography and Tracy McElfresh, BS, Department of Physiology and Biophysics at Case Western Reserve University, for assistance with P–V catheterization.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arya R, Kedar V, Hwang JR, McDonough H, Li H-H, Taylor J, Patterson C. Muscle ring finger protein-1 inhibits PKCepsilon activation and prevents cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Cell Biol 167: 1147–1159, 2004. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200402033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker AJ. Adrenergic signaling in heart failure: a balance of toxic and protective effects. Pflugers Arch 466: 1139–1150, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00424-014-1491-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbato JC, Huang Q-Q, Hossain MM, Bond M, Jin J-P. Proteolytic N-terminal truncation of cardiac troponin I enhances ventricular diastolic function. J Biol Chem 280: 6602–6609, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408525200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bardswell SC, Cuello F, Kentish JC, Avkiran M. cMyBP-C as a promiscuous substrate: phosphorylation by non-PKA kinases and its potential significance. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 33: 53–60, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s10974-011-9276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barefield D, Sadayappan S. Phosphorylation and function of cardiac myosin binding protein-C in health and disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 866–875, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biesiadecki BJ, Davis JP, Ziolo MT, Janssen PML. Tri-modal regulation of cardiac muscle relaxation: Intracellular calcium decline, thin filament deactivation, and cross-bridge cycling kinetics. Biophys Rev 6: 273–289, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s12551-014-0143-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell KS, Moss RL. SLControl: PC-based data acquisition and analysis for muscle mechanics. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H2857–H2864, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00295.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng Y, Wan X, McElfresh TA, Chen X, Gresham KS, Rosenbaum DS, Chandler MP, Stelzer JE. Impaired contractile function due to decreased cardiac myosin binding protein C content in the sarcomere. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 305: H52–H65, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00929.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colson BA, Bekyarova T, Locher MR, Fitzsimons DP, Irving TC, Moss RL. Protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation of cMyBP-C increases proximity of myosin heads to actin in resting myocardium. Circ Res 103: 244–251, 2008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.178996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Decker RS, Decker ML, Kulikovskaya I, Nakamura S, Lee DC, Harris K, Klocke FJ, Winegrad S. Myosin-binding protein C phosphorylation, myofibril structure, and contractile function during low-flow ischemia. Circulation 111: 906–912, 2005. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155609.95618.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du X-J, Fang L, Gao X-M, Kiriazis H, Feng X, Hotchkin E, Finch AM, Chaulet H, Graham RM. Genetic enhancement of ventricular contractility protects against pressure-overload-induced cardiac dysfunction. J Mol Cell Cardiol 37: 979–987, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du X-J, Gao X-M, Kiriazis H, Moore X-L, Ming Z, Su Y, Finch AM, Hannan RA, Dart AM, Graham RM. Transgenic α1A-adrenergic activation limits post-infarct ventricular remodeling and dysfunction and improves survival. Cardiovasc Res 71: 735–743, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fabiato A. Computer programs for calculating total from specified free or free from specified total ionic concentrations in aqueous solutions containing multiple metals and ligands. Methods Enzymol 157: 378–417, 1988. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)57093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng H-Z, Chen M, Weinstein LS, Jin J-P. Removal of the N-terminal extension of cardiac troponin I as a functional compensation for impaired myocardial beta-adrenergic signaling. J Biol Chem 283: 33384–33393, 2008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803302200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fentzke RC, Buck SH, Patel JR, Lin H, Wolska BM, Stojanovic MO, Martin AF, Solaro RJ, Moss RL, Leiden JM. Impaired cardiomyocyte relaxation and diastolic function in transgenic mice expressing slow skeletal troponin I in the heart. J Physiol 517: 143–157, 1999. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0143z.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Godt RE, Lindley BD. Influence of temperature upon contractile activation and isometric force production in mechanically skinned muscle fibers of the frog. J Gen Physiol 80: 279–297, 1982. doi: 10.1085/jgp.80.2.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Govindan S, McElligott A, Muthusamy S, Nair N, Barefield D, Martin JL, Gongora E, Greis KD, Luther PK, Winegrad S, Henderson KK, Sadayappan S. Cardiac myosin binding protein-C is a potential diagnostic biomarker for myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol 52: 154–164, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Govindan S, Sarkey J, Ji X, Sundaresan NR, Gupta MP, de Tombe PP, Sadayappan S. Pathogenic properties of the N-terminal region of cardiac myosin binding protein-C in vitro. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 33: 17–30, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s10974-012-9292-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gresham KS, Mamidi R, Stelzer JE. The contribution of cardiac myosin binding protein-c Ser282 phosphorylation to the rate of force generation and in vivo cardiac contractility. J Physiol 592: 3747–3765, 2014. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.276022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gresham KS, Stelzer JE. The contributions of cardiac myosin binding protein C and troponin I phosphorylation to β-adrenergic enhancement of in vivo cardiac function. J Physiol 594: 669–686, 2016. doi: 10.1113/JP270959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gruen M, Prinz H, Gautel M. cAPK-phosphorylation controls the interaction of the regulatory domain of cardiac myosin binding protein C with myosin-S2 in an on-off fashion. FEBS Lett 453: 254–259, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)00727-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamdani N, de Waard M, Messer AE, Boontje NM, Kooij V, van Dijk S, Versteilen A, Lamberts R, Merkus D, Dos Remedios C, Duncker DJ, Borbely A, Papp Z, Paulus W, Stienen GJM, Marston SB, van der Velden J. Myofilament dysfunction in cardiac disease from mice to men. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 29: 189–201, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s10974-008-9160-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han YS, Arroyo J, Ogut O. Human heart failure is accompanied by altered protein kinase A subunit expression and post-translational state. Arch Biochem Biophys 538: 25–33, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herron TJ, Rostkova E, Kunst G, Chaturvedi R, Gautel M, Kentish JC. Activation of myocardial contraction by the N-terminal domains of myosin binding protein-C. Circ Res 98: 1290–1298, 2006. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000222059.54917.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hinken AC, Solaro RJ. A dominant role of cardiac molecular motors in the intrinsic regulation of ventricular ejection and relaxation. Physiology (Bethesda) 22: 73–80, 2007. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00043.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ke L, Qi XY, Dijkhuis A-J, Chartier D, Nattel S, Henning RH, Kampinga HH, Brundel BJ. Calpain mediates cardiac troponin degradation and contractile dysfunction in atrial fibrillation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 45: 685–693, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kedar V, McDonough H, Arya R, Li H-H, Rockman HA, Patterson C. Muscle-specific RING finger 1 is a bona fide ubiquitin ligase that degrades cardiac troponin I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 18135–18140, 2004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404341102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kensler RW, Shaffer JF, Harris SP. Binding of the N-terminal fragment C0-C2 of cardiac MyBP-C to cardiac F-actin. J Struct Biol 174: 44–51, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kentish JC, McCloskey DT, Layland J, Palmer S, Leiden JM, Martin AF, Solaro RJ. Phosphorylation of troponin I by protein kinase A accelerates relaxation and crossbridge cycle kinetics in mouse ventricular muscle. Circ Res 88: 1059–1065, 2001. doi: 10.1161/hh1001.091640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kudej RK, Iwase M, Uechi M, Vatner DE, Oka N, Ishikawa Y, Shannon RP, Bishop SP, Vatner SF. Effects of chronic beta-adrenergic receptor stimulation in mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol 29: 2735–2746, 1997. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Letavernier E, Perez J, Bellocq A, Mesnard L, de Castro Keller A, Haymann J-P, Baud L. Targeting the calpain/calpastatin system as a new strategy to prevent cardiovascular remodeling in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Circ Res 102: 720–728, 2008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.160077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lynch TL, Sadayappan S. Surviving the infarct: A profile of cardiac myosin binding protein-C pathogenicity, diagnostic utility, and proteomics in the ischemic myocardium. Proteomics Clin Appl 8: 569–577, 2014. doi: 10.1002/prca.201400011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mamidi R, Gresham KS, Verma S, Stelzer JE. Cardiac myosin binding protein-C phosphorylation modulates myofilament length-dependent activation. Front Physiol 7: 38, 2016. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mamidi R, Gresham KS, Stelzer JE. Length-dependent changes in contractile dynamics are blunted due to cardiac myosin binding protein-C ablation. Front Physiol 5: 461, 2014. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mearini G, Gedicke C, Schlossarek S, Witt CC, Krämer E, Cao P, Gomes MD, Lecker SH, Labeit S, Willis MS, Eschenhagen T, Carrier L. Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 regulate cardiac MyBP-C levels via different mechanisms. Cardiovasc Res 85: 357–366, 2010. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michael JJ, Chandra M. Interplay between the effects of dilated cardiomyopathy mutation (R206L) and the protein kinase C phosphomimic (T204E) of rat cardiac troponin T are differently modulated by α- and β-myosin heavy chain isoforms. J Am Heart Assoc 5: e002777, 2016. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michael JJ, Gollapudi SK, Chandra M. Effects of pseudo-phosphorylated rat cardiac troponin T are differently modulated by α- and β-myosin heavy chain isoforms. Basic Res Cardiol 109: 442, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00395-014-0442-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moss RL, Fitzsimons DP, Ralphe JC. Cardiac MyBP-C regulates the rate and force of contraction in mammalian myocardium. Circ Res 116: 183–192, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.300561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mun JY, Previs MJ, Yu HY, Gulick J, Tobacman LS, Beck Previs S, Robbins J, Warshaw DM, Craig R. Myosin-binding protein C displaces tropomyosin to activate cardiac thin filaments and governs their speed by an independent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 2170–2175, 2014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316001111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagayama T, Takimoto E, Sadayappan S, Mudd JO, Seidman JG, Robbins J, Kass DA. Control of in vivo left ventricular [correction] contraction/relaxation kinetics by myosin binding protein C: Protein kinase A phosphorylation dependent and independent regulation. Circulation 116: 2399–2408, 2007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patterson C, Portbury AL, Schisler JC, Willis MS. Tear me down: Role of calpain in the development of cardiac ventricular hypertrophy. Circ Res 109: 453–462, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.239749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Previs MJ, Mun JY, Michalek AJ, Previs SB, Gulick J, Robbins J, Warshaw DM, Craig R. Phosphorylation and calcium antagonistically tune myosin-binding protein C’s structure and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: 3239–3244, 2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522236113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pyle WG, Chen Y, Hofmann PA. Cardioprotection through a PKC-dependent decrease in myofilament ATPase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H1220–H1228, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00076.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sadayappan S, Osinska H, Klevitsky R, Lorenz JN, Sargent M, Molkentin JD, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Robbins J. Cardiac myosin binding protein C phosphorylation is cardioprotective. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 16918–16923, 2006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607069103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schlossarek S, Schuermann F, Geertz B, Mearini G, Eschenhagen T, Carrier L. Adrenergic stress reveals septal hypertrophy and proteasome impairment in heterozygous Mybpc3-targeted knock-in mice. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 33: 5–15, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s10974-011-9273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Solaro RJ, Henze M, Kobayashi T. Integration of troponin I phosphorylation with cardiac regulatory networks. Circ Res 112: 355–366, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.268672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Solaro RJ, Moir AJG, Perry SV. Phosphorylation of troponin I and the inotropic effect of adrenaline in the perfused rabbit heart. Nature 262: 615–617, 1976. doi: 10.1038/262615a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stelzer JE, Fitzsimons DP, Moss RL. Ablation of myosin-binding protein-C accelerates force development in mouse myocardium. Biophys J 90: 4119–4127, 2006. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.078147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stelzer JE, Patel JR, Moss RL. Protein kinase A-mediated acceleration of the stretch activation response in murine skinned myocardium is eliminated by ablation of cMyBP-C. Circ Res 99: 884–890, 2006. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000245191.34690.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stelzer JE, Patel JR, Walker JW, Moss RL. Differential roles of cardiac myosin-binding protein C and cardiac troponin I in the myofibrillar force responses to protein kinase A phosphorylation. Circ Res 101: 503–511, 2007. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takimoto E, Soergel DG, Janssen PML, Stull LB, Kass DA, Murphy AM. Frequency- and afterload-dependent cardiac modulation in vivo by troponin I with constitutively active protein kinase A phosphorylation sites. Circ Res 94: 496–504, 2004. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000117307.57798.F5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taneike M, Mizote I, Morita T, Watanabe T, Hikoso S, Yamaguchi O, Takeda T, Oka T, Tamai T, Oyabu J, Murakawa T, Nakayama H, Nishida K, Takeda J, Mochizuki N, Komuro I, Otsu K. Calpain protects the heart from hemodynamic stress. J Biol Chem 286: 32170–32177, 2011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.248088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tong CW, Stelzer JE, Greaser ML, Powers PA, Moss RL. Acceleration of crossbridge kinetics by protein kinase A phosphorylation of cardiac myosin binding protein C modulates cardiac function. Circ Res 103: 974–982, 2008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.177683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tong CW, Wu X, Liu Y, Rosas PC, Sadayappan S, Hudmon A, Muthuchamy M, Powers PA, Valdivia HH, Moss RL. Phosphoregulation of cardiac inotropy via myosin binding protein-C during increased pacing frequency or β1-adrenergic stimulation. Circ Heart Fail 8: 595–604, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Eyk JE, Powers F, Law W, Larue C, Hodges RS, Solaro RJ. Breakdown and release of myofilament proteins during ischemia and ischemia/reperfusion in rat hearts: Identification of degradation products and effects on the pCa-force relation. Circ Res 82: 261–271, 1998. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.82.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wei H, Jin J-P. NH2-terminal truncations of cardiac troponin I and cardiac troponin T produce distinct effects on contractility and calcium homeostasis in adult cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 308: C397–C404, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00358.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Westfall MV, Solaro RJ. Alterations in myofibrillar function and protein profiles after complete global ischemia in rat hearts. Circ Res 70: 302–313, 1992. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.70.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu SC, Dahl EF, Wright CD, Cypher AL, Healy CL, O’Connell TD. Nuclear localization of a1A-adrenergic receptors is required for signaling in cardiac myocytes: An “inside-out” a1-AR signaling pathway. J Am Heart Assoc 3: e000145, 2014. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang X, Szeto C, Gao E, Tang M, Jin J, Fu Q, Makarewich C, Ai X, Li Y, Tang A, Wang J, Gao H, Wang F, Ge XJ, Kunapuli SP, Zhou L, Zeng C, Xiang KY, Chen X. Cardiotoxic and cardioprotective features of chronic β-adrenergic signaling. Circ Res 112: 498–509, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.273896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]