Whole cell recording of L-type Ca2+ currents in atrial myocytes from rat hearts subjected to coronary artery ligation compared with those from sham-operated controls reveals marked reduction in current density in heart failure without change in channel subunit expression and associated with altered phosphorylation independent of protein kinase A.

Keywords: atrial remodeling, coronary artery ligation, voltage-gated Ca2+ channel

Abstract

Constitutive regulation by PKA has recently been shown to contribute to L-type Ca2+ current (ICaL) at the ventricular t-tubule in heart failure. Conversely, reduction in constitutive regulation by PKA has been proposed to underlie the downregulation of atrial ICaL in heart failure. The hypothesis that downregulation of atrial ICaL in heart failure involves reduced channel phosphorylation was examined. Anesthetized adult male Wistar rats underwent surgical coronary artery ligation (CAL, N=10) or equivalent sham-operation (Sham, N=12). Left atrial myocytes were isolated ~18 wk postsurgery and whole cell currents recorded (holding potential=-80 mV). ICaL activated by depolarizing pulses to voltages from -40 to +50 mV were normalized to cell capacitance and current density-voltage relations plotted. CAL cell capacitances were ~1.67-fold greater than Sham (P ≤ 0.0001). Maximal ICaL conductance (Gmax) was downregulated more than 2-fold in CAL vs. Sham myocytes (P < 0.0001). Norepinephrine (1 μmol/l) increased Gmax >50% more effectively in CAL than in Sham so that differences in ICaL density were abolished. Differences between CAL and Sham Gmax were not abolished by calyculin A (100 nmol/l), suggesting that increased protein dephosphorylation did not account for ICaL downregulation. Treatment with either H-89 (10 μmol/l) or AIP (5 μmol/l) had no effect on basal currents in Sham or CAL myocytes, indicating that, in contrast to ventricular myocytes, neither PKA nor CaMKII regulated basal ICaL. Expression of the L-type α1C-subunit, protein phosphatases 1 and 2A, and inhibitor-1 proteins was unchanged. In conclusion, reduction in PKA-dependent regulation did not contribute to downregulation of atrial ICaL in heart failure.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Whole cell recording of L-type Ca2+ currents in atrial myocytes from rat hearts subjected to coronary artery ligation compared with those from sham-operated controls reveals marked reduction in current density in heart failure without change in channel subunit expression and associated with altered phosphorylation independent of protein kinase A.

atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common clinical arrhythmia and is associated with significant mortality, primarily through stroke and heart failure (2, 3). There are many causes of AF and although patients generally show multiple predisposing risk factors, >70% of patients have some form of underlying structural heart disease (2, 3). Evidence from animal models of heart diseases that predispose to AF indicates that disease-associated remodeling of the atria, presumably due to mechanical overload of the atrial wall, creates an arrhythmic substrate in which AF is more likely to arise and be sustained (10, 13, 22, 29, 30, 32, 34, 48). In addition to atrial enlargement, fibrosis and conduction abnormalities that establish a substrate for reentry, cellular remodeling involving cellular hypertrophy, changes in membrane structure, and abnormal expression and function of ion channels and transporters are also likely to contribute to the genesis of AF (4, 10, 13, 15, 16, 18, 22, 26, 29, 30, 32, 34, 35, 38, 48, 51).

Atrial L-type Ca2+ current (ICaL) is reduced in heart disease, both in animal models (4, 13, 29, 38) and in myocytes from human dilated atria (19, 33). The loss of ICaL has been suggested to have a number of sequelae that contribute to the genesis of AF, including 1) changes in action potential configuration and the rate dependence of refractoriness, 2) abnormalities in Ca2+ handling and the triggering of episodes of AF, and 3) hypocontractility and dilatation of the atria (15, 29, 33, 35, 42). The mechanisms for the downregulation of ICaL remain unclear and may be dependent on the underlying disease. For example, both spontaneously hypertensive rats and rats with coronary artery ligation-induced myocardial infarction show a substrate for atrial fibrillation associated with atrial fibrosis, hypertrophy, and downregulation in ICaL (4, 10, 13, 38). However, although the reduced ICaL density in atrial myocytes from spontaneously hypertensive rats compared with currents in normotensive Wistar-Kyoto controls has been associated with reduction in expression of the pore-forming α1c subunit, α1c protein expression was unchanged in rat atrial myocytes from a coronary artery ligation model (4, 38). The reduction in atrial ICaL in coronary artery ligation-induced heart failure has been suggested to be due to decreased cAMP-dependent basal regulation of L-type Ca2+ channels (4, 19). However, although the cAMP-dependent protein kinase, PKA, has also been demonstrated to play an important role in the basal regulation of ICaL in ventricular myocytes (7, 8), the constitutive regulation of ventricular ICaL by PKA appears to be increased in a coronary artery ligation model of heart failure (9). In addition, the reduction in atrial ICaL in patients with chronic AF has been associated with a reduction in calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) activity and an increase in protein phosphatase activity in AF with no change in the expression of L-type Ca2+ channel subunit protein (14). Changes in the activity of the serine/threonine protein phosphatases, PP1 and PP2A, and the regulatory subunit of PP1, inhibitor-1, have been implicated in the pro-arrhythmic remodeling in AF (25). Thus the aim of this study was to examine the mechanisms underlying the regulation of atrial ICaL in heart failure. The study involved the use of the coronary artery ligation model of myocardial infarction-associated heart failure reported previously (9, 23).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals, heart failure, and myocyte isolation.

All procedures were performed in accordance with UK legislation and approved by the University of Bristol Ethics Committee. The study was conducted in parallel with another investigation using the same animals to investigate ventricular cellular remodeling in heart failure and thereby conformed to the reduction component of the 3R’s (9, 23, 41). Heart failure was induced in 10 adult male Wistar rats by ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery (CAL), which results in left ventricular hypertrophy and dilatation, and systolic and diastolic dysfunction 16 wk after surgery (9, 36). Twelve adult male Wistar rats were subject to an equivalent Sham operation (Sham). Left atrial myocytes were isolated ~18 wk after surgery. Operations were performed under surgical anesthesia (ketamine 75 mg/kg, medetomidine 0.5 mg/kg ip) with appropriate analgesia (buprenorphine 0.05 mg/kg sc). We have previously reported that left ventricular ejection fraction was reduced by 50% and left ventricular end-diastolic volume was increased by more than 100% in CAL compared with Sham for this group of animals (9). Atrial myocytes were isolated using our standard methods (6, 8), following rapid excision of the heart under pentobarbital anesthesia. Isolated myocytes were stored for 2-10 h before use on the day of isolation.

Whole cell recording.

Whole cell currents were recorded using the ruptured-patch technique, as described previously (6). Myocytes were superfused with Tyrode’s solution composed of (in mmol/l) 140 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2.5 CaCl2, 10 d-glucose and 5 HEPES, pH 7.4 at 36oC. The internal solution was composed of (in mmol/l) 10 NaCl, 110 KCl, 0.4 MgCl2, 5 d-glucose, 10 HEPES, 5 BAPTA, 5 K-ATP and 0.5 Tris-GTP, pH 7.3 (KOH). Currents were low-pass filtered with a corner frequency of 1 kHz and recorded to the hard drive of a PC at a sampling frequency of 5 kHz. The junction potential was compensated electronically on immersion of the pipette tip in the bath solution, and no further compensation was applied. Whole cell capacitance transients were compensated electronically. Series resistances were typically between 3 and 8 MΩ in both Sham and CAL myocytes and were not compensated, and no corrections were made for voltage-drop error. A square-shaped voltage pulse protocol was applied: from a holding potential of −80 mV, 500-ms depolarizing pulses to potentials from −40 to +50 mV were applied, increasing in 10-mV increments every 5 s. A 50-ms prepulse to −40 mV was used to inactivate the Na+ current. The L-type Ca2+ current (ICaL) was measured as the difference between the peak inward current and the current at the end of the pulse. Although the inward currents recorded under these conditions could be completely abolished using 3 μmol/l nifedipine, the contribution of transient outward currents may have led to a slight underestimation in ICaL (13). Current densities were calculated as the currents normalized to whole cell capacitance. Mean ICaL values were plotted against the corresponding voltage and the current-voltage relation fitted by a modified Boltzmann equation:

| (1) |

where Vm was the membrane potential, Gmax represented the maximum conductance, Vrev was the effective reversal potential for the current, Vhalf represents the voltage of half-maximal activation, and k represented a slope factor (6). Fitted parameters are reported with the standard error of fitting.

Drugs and reagents.

All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Poole, UK) unless otherwise indicated. Norepinephrine (NE) was dissolved in deionized water as a 10 mmol/l stock solution and dissolved to the final concentration in the extracellular solution on the day of experiment; 1 μmol/l of NE was used as an effective concentration of the physiological agonist of adrenoceptors previously shown to potentiate ICaL maximally and that is representative of concentrations achieved at the cardiac sympathetic junction (6, 24). Protein kinase A (PKA) was inhibited using 10 μmol/l H-89, a concentration that has been shown to inhibit phosphorylation of the cardiac α1c L-type Ca2+ channel subunit (12). In some experiments, autocamtide-2-related inhibitory peptide (AIP) was included in the pipette solution (5 μmol/l) to inhibit Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII) (27). Calyculin A (Cal A) was used at a concentration of 100 nmol/l to inhibit the serine/threonine protein phosphatases 1 (PP1) and 2A (PP2A) (39).

Western blot analysis.

Protein (30 μg) from cell homogenate samples was run on reducing 4-15% gradient SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes. Membranes were probed with anti-Cav1.2 L-type Ca2+ channel α1c subunit (ACC-003; Alomone, Israel), anti-protein phosphatase 1 (anti-PP1, sc-7482; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-protein phosphatase 2A (anti-PP2A, 05-421; Millipore, Watford, UK), and anti-protein phosphatase inhibitor-1 (anti-Inhibitor-1, ab-40877; AbCam, Cambridge, UK). Protein bands were visualized and images captured using the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, chemiluminescence, and a G:BOX Chemi XT4 imaging system (Syngene). The densities of the bands were measured using ImageJ (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) and normalized to the density of the GAPDH band (Sigma-Aldrich UK, Poole, UK).

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as means ± SE. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism (vs5.04, GraphPad Software). Datasets were subject to D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test. Sample sizes are provided in the figure legends as (n numbers of cells/N numbers of animals). Sham vs. CAL comparisons in single parameters were analyzed using either Mann-Whitney or Student’s unpaired t-test. Correlation analysis was performed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Current-voltage relations were analyzed by two-way repeated measures (RM) ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. Other results were analyzed by one-way RM ANOVA with Bonferroni‘s multiple-comparisons test. P ≤ 0.05 was considered as the limit of statistical confidence.

RESULTS

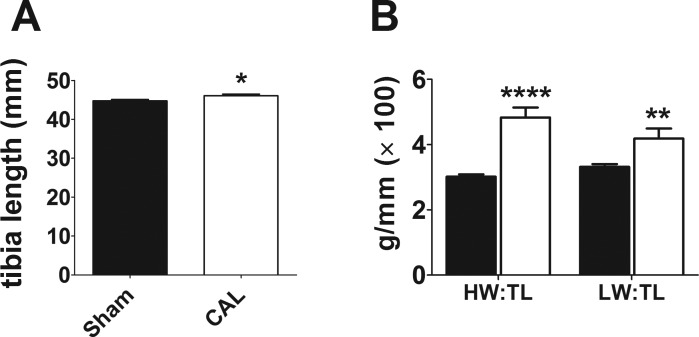

Single left atrial myocytes were isolated from Sham and CAL rats 18.9 ± 0.45 wk (N = 12) and 18.7 ± 0.48 wk (N = 10, P = 0.678) following surgery, respectively. On the day of isolation, there was little difference between the two groups in body weight (Sham 447.3 ± 9.04 g vs. CAL 491.5 ± 20.1 g; P = 0.052) or tibia length (Fig. 1A). However, CAL animals showed significantly increased heart weights (HW) and lung weights (LW) relative to tibia length (TL; Fig. 1B), indicative of early-stage heart failure as demonstrated in our previous report using these hearts (9). In summary, the data indicate early-onset heart failure in the CAL animals in the present study. Whole cell capacitance values of left atrial myocytes isolated from CAL hearts were ~1.67 times larger than those from Sham controls, indicating considerable cellular hypertrophy of atrial myocytes in heart failure (Fig. 2A). Cell length and width were measured in 12 Sham (from 2 hearts) and 12 CAL (from 2 hearts) isolated atrial myocytes. Whereas there was no difference in cell length (Sham 103.6 ± 4.1 μm, CAL 113.1 ± 5.8 μm; P = 0.1938), cell width was significantly greater in CAL compared with Sham myocytes (Sham 14.5 ± 1.0 μm, CAL 22.0 ± 1.3 μm; P=0.0001). Taken together, these data are consistent with the atrial hypertrophy previously reported in coronary artery ligation models of heart failure (10, 50).

Fig. 1.

Atrial L-type Ca2+ current density in heart failure. A: mean tibia length from 12 Sham and 10 CAL rats. *P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test. B: mean heart weight/tibia length (HW/TL) and lung weight/tibia length (LW/TL) ratios. Sham, filled columns; CAL, open columns. **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.001, Mann-Whitney test.

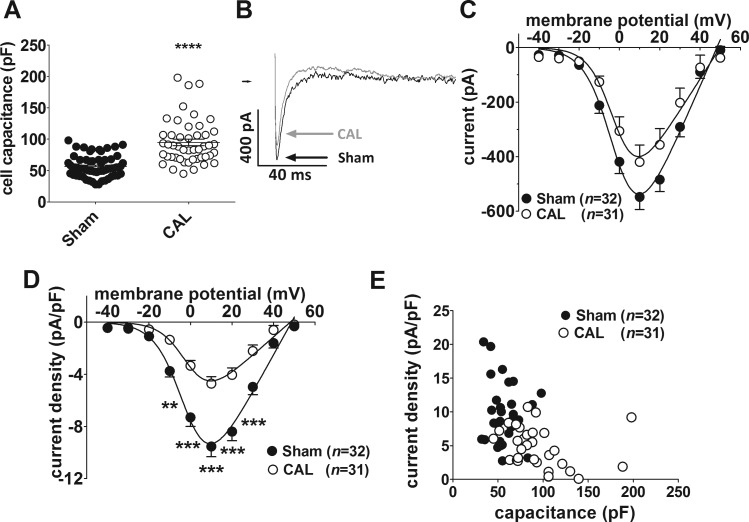

Fig. 2.

A: whole cell capacitances for Sham (n = 63/12) and CAL (n = 47/10) myocytes. ****P < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney test. B: representative whole cell L-type Ca2+ current (ICaL) traces at +10 mV. Sham, black; CAL, gray. C: mean ICaL-voltage relations for Sham [filled circles, (n no. of cells/N no. of animals) = 32/12] and CAL (open circles, n/N = 31/10) myocytes. D: mean ICaL density-voltage relations for Sham (filled circles) and CAL (open circles) myocytes. Same data as shown in C. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest. Solid lines in C and D represent fits to Eq. 1. E: correlation between ICaL density at +10 mV in Sham (filled circles, n/N = 32/12) and CAL (open circles, n = 31/10) myocytes. Atrial ICaL density for the two groups of cells combined was significantly correlated (r = −0.4772, n/N = 63/22, P < 0.0001).

Figure 2B shows representative recordings from Sham and CAL myocytes of L-type Ca2+ current (ICaL) elicited by depolarizing pulses to +10 mV. Mean ICaL-voltage relations in Sham and CAL myocytes are shown in Fig. 2C. In both groups of cells, currents were activated from voltages of −30 mV, were maximal at around +10 mV, and reversed at ~+50 mV, typical of cardiac ICaL (Fig. 2C). ICaL-voltage relations were fitted with a modified Boltzmann equation (Eq. 1; see materials and methods). There were no differences between CAL and Sham myocytes in the voltage of half-maximal activation (Vhalf: Sham −0.72 ± 1.5 mV, CAL −1.09 ± 2.46 mV), slope factor (k: Sham 6.89 ± 0.86 mV, CAL 6.11 ± 1.51 mV) or reversal potential (Vrev: Sham 48.25 ± 1.38 mV, CAL 49.83 ± 2.94 mV), indicating no significant changes in the voltage dependence or ion selectivity of ICaL in heart failure. However, although the differences between CAL and Sham myocytes in mean ICaL did not reach statistical confidence at any potential, the fitted maximal conductance was less in CAL than in Sham cells (Gmax: Sham 17.01 ± 1.51 nS, CAL 11.66 ± 1.92 nS; P = 0.0317). After normalization to cell capacitance, the corresponding mean current density-voltage relations (Fig. 2D) show significantly smaller ICaL density in CAL myocytes compared with Sham controls at voltages from −10 to +30 mV. The maximal conductance density was reduced by more than 50% in CAL compared with Sham myocytes (Gmax: Sham 288.4 ± 24.2 pS/pF, CAL 140.6 ± 16.5 pS/pF; P < 0.0001). The correlation between ICaL density at +10 mV and cell capacitance in atrial cells from Sham and CAL hearts is shown in Fig. 2E. In CAL cells, ICaL density was inversely correlated with capacitance (r = −0.4219, n = 31, P = 0.0181). Taken together, these data indicate that heart failure through coronary artery ligation causes a reduction in whole cell ICaL density of left atrial myocytes that is predominantly due to an increase in cell membrane surface area with minor changes in absolute current.

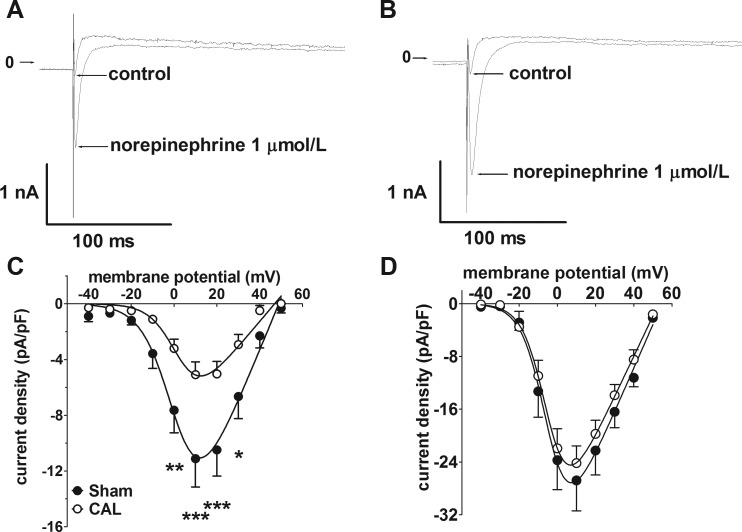

The reduction in atrial ICaL density by more than 50% caused by CAL-induced heart failure was consistent with a previous report in a similar model, in which it was also shown that the difference in ICaL density between sham control and heart failure was reduced following β-adrenoceptor stimulation with isoproterenol (4). The sympathetic neurotransmitter, NE, has previously been shown to potentiate atrial ICaL via β1-adrenoceptors without significant contribution from either α1- or β2-adrenoceptors (6). Therefore, the effects of NE on differences in ICaL density between Sham and CAL atrial myocytes were examined. As illustrated by the representative current traces in Fig. 3, 1 μmol/l NE produced a marked increase in ICaL in both Sham and CAL myocytes (Fig. 3, A and B). Notably, although statistically significant differences in ICaL density-voltage relations (Fig. 3C) and maximal conductance density were evident under control conditions (Gmax: Sham 371.6 ± 65.2 pS/pF, CAL 182.0 ± 28.6 pS/pF, P = 0.0091), these differences were lost in the presence of NE (Fig. 3D; Gmax: Sham 660.6 ± 113.2 pS/pF, CAL 494.3 ± 61.2 pS/pF, P = 0.1798). Thus NE had a greater effect on Gmax in CAL (2.72-fold increase) than in Sham (1.78-fold increase) myocytes. In addition, Vhalf was negatively shifted by NE in both cell types (Sham: control 1.85 ± 2.98 mV to NE −4.38 ± 2.43 mV, P = 0.1434; CAL: control 2.93 ± 2.50 mV to NE −5.57 ± 1.66 mV, P = 0.0121). Overall, these data demonstrate differences in the regulation of the L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC) currents between Sham and CAL cells. To examine whether constitutive phosphorylation of LTCC contributed to the differences in ICaL density, cells were superfused with the serine/threonine protein phosphatase inhibitor, calyculin A (100 nmol/l) (Fig. 4). In both groups of cells, calyculin A resulted in increased mean current densities at voltages from −20 to +40 mV (Fig. 4). However, the relative increase in maximal conductance was not significantly different between the two groups (P = 0.4850): in Sham cells, Gmax was increased 2.75-fold (control 187.2 ± 26.9 pS/pF, calyculin A 514.5 ± 47.4 pS/pF, P < 0.0001), whereas in CAL cells Gmax was increased 3.34-fold (control 111.3 ± 14.2 pS/pF, calyculin A 371.7 ± 36.1 pS/pF, P < 0.0001). Critically, in contrast to the effect of NE, in the presence of calyculin A, Gmax was greater in Sham than in CAL cells (two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post hoc test, P < 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Effects of norepinephrine on atrial L-type Ca2+ current (ICaL) density. A: representative Ca2+ current traces at +10 mV in an atrial myocyte from a Sham-operated rat in control conditions and in the presence of 1 μmol/l norepinephrine. B: representative Ca2+ current traces in an atrial myocyte from a CAL rat in control conditions and in the presence of 1 μmol/l norepinephrine. Arrows indicate zero current level. C: mean ICaL density-voltage relations under control conditions from Sham-operated (n/N = 5/3, filled circles) and CAL (n/N = 9/4, open circles). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Bonferroni posttest following 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA. D: mean ICaL density-voltage relations in the presence of 1 μmol/l norepinephrine from Sham-operated (n/N = 5/3, open circles) and CAL (n/N = 9/4, filled circles). Data correspond to the control data shown in C. Note the difference in current density scale between C and D. Solid lines in C and D represent fits to Eq. 1.

Fig. 4.

Atrial L-type Ca2+ currents following phosphatase inhibition. A, i: representative current traces recorded at +10 mV from a Sham myocyte before and after superfusion with 100 nmol/l calyculin A. A, ii: ICaL density-voltage relations from Sham myocytes (n/N = 6/3) in control (filled circles) and in the presence of 100 nmol/l calyculin A (open circles). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA and Bonferroni posttest. B, i: representative current traces recorded at +10 mV from a CAL myocyte before and after superfusion with 100 nmol/l calyculin A. B, ii: ICaL density-voltage relations from CAL myocytes (n/N = 9/3) in control (filled squares) and in the presence of 100 nmol/l calyculin A (open squares). ***P < 0.001, 2-way ANOVA and Bonferroni posttest.

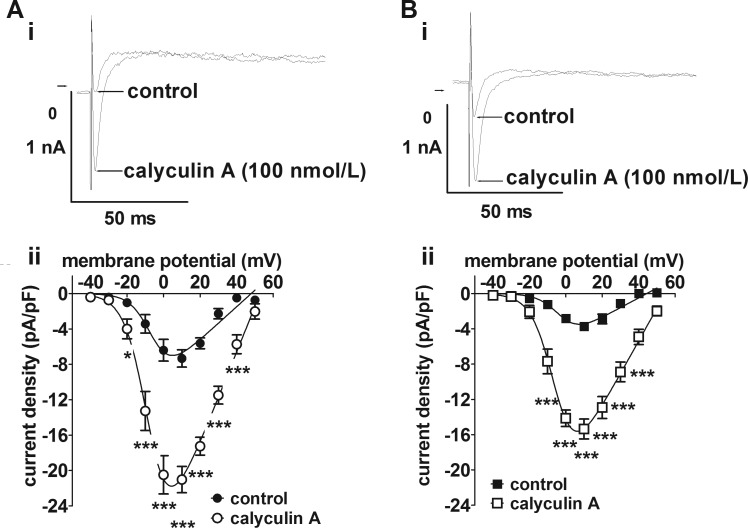

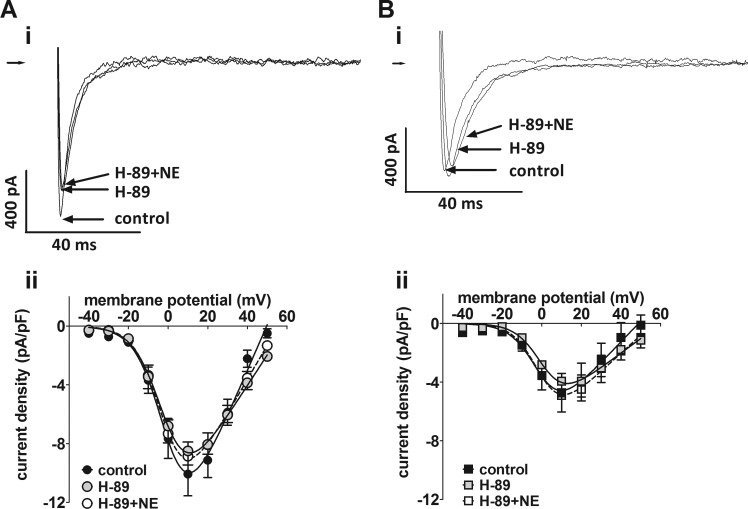

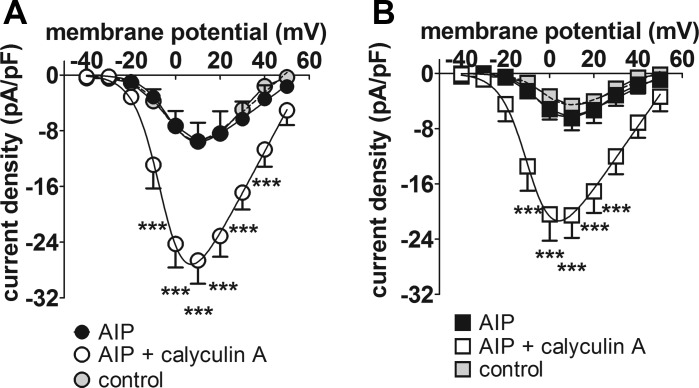

The role of protein kinase A in differences in basal ICaL density between the two groups of atrial cells was examined using the PKA inhibitor, H-89 (10 μmol/l) (Fig. 5). Superfusion of cells with H-89 had no effect on basal ICaL in either Sham (Fig. 5A) or CAL (Fig. 5B) myocytes, although the response to NE (1 μmol/l) was abolished. Further evidence that PKA does not contribute to the constitutive regulation of ICaL was obtained in a small series of experiments conducted in Sham cells only, in which the increase in ICaL density on superfusion with 100 nmol/l calyculin A was not abolished by application of the PKA inhibitor, PKI (20 μmol/l), via the pipette solution (data not shown). CaMKII has also been suggested to contribute to basal ICaL in atrial myocytes (17). Therefore, we examined the effect on basal ICaL of inhibition of CaMKII with AIP (5 μmol/l) applied via the intracellular pipette solution in Sham and CAL cells (Fig. 6). Comparison of the mean current density-voltage relations of the Sham (Fig. 6A) and CAL (Fig. 6B) myocytes dialyzed with AIP (black-filled symbols) with the corresponding control data (gray-filled symbols) showed no effect of AIP on basal ICaL in either cell type. Moreover, ICaL density was increased by 100 nmol/l calyculin A in both Sham and CAL cells dialyzed with AIP. Further evidence that CaMKII played no role in basal ICaL came from a small number of experiments in which Sham myocytes were superfused with the CaMKII inhibitor, KN-93 (5 μmol/l). Treatment with KN-93 had no effect on mean ICaL density at +10 mV in Sham cells (data not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that inhibition of CaMKII had no effect on basal ICaL in either Sham or CAL myocytes.

Fig. 5.

Effect of the protein kinase A inhibitor, H-89. A, i: representative Ca2+ current traces at +10 mV in an atrial myocyte from a Sham-operated rat in control Tyrode’s, in the presence of 10 μmol/l H-89, and in the presence of 10 μmol/l H-89 and 1 μmol/l norepinephrine (NE). A, ii: mean ICaL density-voltage relations from Sham myocytes (n/N = 8/4) in control (black-filled circles), in the presence of 10 μmol/l H-89 (gray-filled circles) and in the presence of 10 μmol/l H-89 and 1 μmol/l NE (open circles). B, i: representative Ca2+ current traces in an atrial myocyte from a CAL rat in control Tyrode’s, in the presence of 10 μmol/l H-89, and in the presence of 10 μmol/l H-89 and 1 μmol/l NE. Right-pointing arrows indicate zero current level. B, ii: mean ICaL density-voltage relations from CAL myocytes (n/N = 13/4) in control (black filled squares), in the presence of 10 μmol/l H-89 (gray-filled squares) and in the presence of 10 μmol/l H-89 and 1 μmol/l NE (open squares).

Fig. 6.

Effect of the Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II inhibitor, AIP. A: mean ICaL density-voltage relations for Sham myocytes with AIP included in the pipette solution (n/N = 4/1). Black-filled circles, AIP-dialyzed cells in control Tyrode’s; open circles, AIP-dialyzed cells in the presence of 100 nmol/l calyculin A. B: mean ICaL density-voltage relations for CAL myocytes with AIP included in the pipette solution (n/N = 5/1). Black-filled squares, AIP-dialyzed cells in control Tyrode’s; open squares, AIP-dialyzed cells in the presence of 100 nmol/l calyculin A. Data from Sham (A) and CAL (B) myocytes under control conditions (respectively, n/N = 33/12 and 31/10) are shown as, respectively, gray-filled circles and gray-filled squares, for comparison. ***P < 0.001, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA and Bonferroni posttest vs. corresponding AIP control.

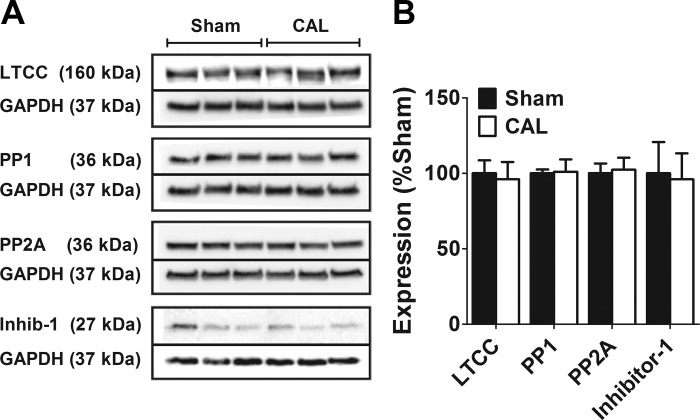

The expression of proteins for the predominant LTCC pore-forming α1c subunit, Cav1.2, for the serine/threonine protein phosphatases, PP1 and PP2A, and for the inhibitory subunit of PP1, inhibitor-1, was examined by Western blotting in atrial cell preparations from 3 Sham and 3 CAL hearts (Fig. 7). There were no significant differences in the total content of α1c subunit relative to GAPDH expression between the two groups of cells. The increase in ICaL density on inhibition of protein phosphatase with calyculin A (Fig. 4) indicates a role for protein phosphorylation in the basal regulation of LTTCs in both groups of cells. However, expression of neither PP1 nor PP2A was changed in heart failure (Fig. 7). Moreover, the PKA-dependent inhibitory regulator of PP1, inhibitor-1, reduced expression of which in failing ventricles has been suggested to contribute to reduced protein phosphorylation (20), was also not different between the two groups of cells.

Fig. 7.

Left atrial expression of the Cav1.2 LTCC α1c subunit and various protein phosphatases in heart failure. A: representative Western blots of LTCC, protein phosphatases, and GAPDH from Sham and CAL rats. For each protein, the bands are taken from the same gel and have not been manipulated for contrast, color-balance, brightness, or background. Solid lines demarcate the bands for the target protein and for the GAPDH loading control, which were taken from the same gel. For each protein, the molecular weights of the bands are indicated. B: mean band intensity expressed relative to Sham as 100%. Data are means ± SE from 3 Sham and 3 CAL hearts.

DISCUSSION

This study clearly demonstrates a reduction in atrial ICaL density in heart failure, due predominantly to cellular hypertrophy without significant change in absolute current amplitude. However, the total expression of the α1c subunit protein relative to total tissue protein was also not changed in heart failure, indicating that the reduction in basal current density in heart failure did not involve significant changes in the relative amount of protein in hypertrophied cells. It seems likely that a change in L-type Ca2+ channel regulation underlay the reduction in ICaL density. The difference in ICaL density between atrial cells from failing and sham hearts was abolished in the presence of NE, which increased the L-type Ca2+ current >50% more effectively in CAL cells than in Sham. Moreover, the increase in current density produced by inhibition of serine/threonine protein phosphatase activity with calyculin A provides evidence of phosphorylation-dependent basal regulation of ICaL in both groups of cells. In these respects, the data resemble those reported by Dinanian et al. in human atrial myocytes from patients with heart failure (19) and by Boixel et al. in a model of coronary artery ligation-induced heart failure in rats similar to that used in the present study (4) and contrast with studies of chronic hypertension and pressure overload in rats that show a reduction in atrial α1c subunit protein expression (38, 51). However, contrary to the mechanism proposed by Boixel et al. (4), the insensitivity of basal ICaL to H-89 and PKI in the present study demonstrated that protein kinase A did not contribute to the constitutive regulation of atrial ICaL. This finding differs from the conclusion of Boixel et al. that the downregulation of atrial ICaL in heart failure was “… caused by changes in basal cAMP-dependent regulation of the current …” (4). A notable difference between that study and this is that Boixel et al. did not report the effects of inhibition of protein kinase A (4). Basal ICaL in the present study was also insensitive to AIP and KN-93, demonstrating that, unlike human atrial myocytes, CaMKII did not contribute to the constitutive regulation of the L-type Ca2+ current (14).

The present study showed little difference between atrial cells from failing hearts and sham controls in the effectiveness of inhibition of the protein phosphatases PP1 and PP2A so that, in contrast to previous reports, differences in protein dephosphorylation via these phosphatases are unlikely to account for the downregulation of atrial ICaL density in heart failure (4, 14). Consistent with this suggestion, no differences were found in the expression of PP1, PP2A or inhibitor-1. The basis for the differences between the study of Boixel et al. and the present study, in which similar models of heart failure were used, remain unclear although it is possible that the results of the present study, in which animals were maintained for 18 wk following coronary artery ligation, represent a more chronic state of remodeling than did those of Boixel et al., in which animals were maintained for 3 mo postsurgery (4, 9, 36, 37).

The mechanism for the downregulation of atrial ICaL in heart failure remains unclear. A number of kinases, including PKC, PKD, PKG and tyrosine kinases, have been reported to modulate cardiac ICaL, and, in principle, changes in the activity of any of these could contribute to the reduction in basal ICaL in heart failure (1, 5, 28). Additionally, calcineurin (PP2B) has been suggested to associate with and regulate the L-type Ca2+ channel α1c-subunit and to contribute to downregulation of ICaL during atrial remodeling (46, 53). Atrial ICaL is also regulated by NO through complex pathways involving cGMP-dependent PKG, cGMP-inhibited phosphodiesterases, and S-nitrosylation of the α1c-subunit (31, 40, 47, 49). It has been suggested that oxidative stress may contribute to the development of the arrhythmic substrate and downregulation of ICaL during atrial remodeling and this may involve changes in the NO-dependent regulation of L-type Ca2+ channels (11, 21, 43). The previously reported changes in atrial intracellular cGMP production together with the increased effect of phosphodiesterase inhibition on ICaL are consistent with the proposal that changes in NO/cGMP-dependent regulation of L-type Ca2+ channels may underlie both the reduced basal current and increased sensitivity to noradrenergic agonism in heart failure (4, 19). On the other hand, whereas it has previously been shown that the effect of NE on ICaL is almost exclusively mediated via β1-adrenoceptors in atrial myocytes from normal hearts (6), the contribution of α1-, β2-, and β3-adrenoceptors in heart failure cannot be ruled out (44, 45, 52). Thus future studies using selective adrenoceptor ligands and inhibitors of signaling cascades will be important to establish the mechanism underlying the remodeling of atrial ICaL regulation in heart failure.

The present study also adds to evidence that the mechanisms of ICaL regulation differ between atrial and ventricular cells (6–8). Although both PKA and CaMKII have previously been shown to contribute to the basal regulation of ventricular ICaL, particularly at the t-tubule membrane (7–9, 12), basal ICaL in atrial myocytes from either sham control or failing hearts in the present study was insensitive to inhibition of PKA or CaMKII. Notably, the absence of regulation of basal atrial ICaL by PKA in CAL hearts in the present study contrasts markedly with the increased PKA-dependent regulation of basal ICaL at the t-tubule of ventricular myocytes reported recently from the same hearts (9). The action of calyculin A on atrial ICaL demonstrates both that the basal regulation of ICaL in rat atrial myocytes depends on constitutive phosphorylation by a serine/threonine kinase and that PP1/PP2A phosphatase activity contributes to the degree of basal phosphorylation. Thus the identity of the kinases and phosphatases responsible for the constitutive regulation of atrial ICaL in both normal hearts and in heart failure warrants further investigation.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation (FS/10/68 to R. C. Bond, PG/10/91 to C. H. Orchard and A. F. James, and PG/11/97 to J. C. Hancox, A. F. James, and C. H. Orchard). R. C. Bond was in receipt of a fellowship from the British Heart Foundation that funded this work (FS/10/68). A. F. James and J. C. Hancox were lead applicants on the fellowship that funded this work (FS/10/68). C. H. Orchard and A. F. James were principal investigators on the project and program grants that funded S. M. Bryant (PG/10/91, RG/12/10).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.C.B., S.M.B., and J.J.W. performed experiments (R.C.B. whole cell records, S.M.B. surgery for heart failure model; J.J.W. Western blot analysis); R.C.B. and J.J.W. analyzed data; R.C.B., J.J.W., J.C.H., C.H.O., and A.F.J. interpreted results of experiments; R.C.B., J.J.W., and A.F.J. prepared figures; R.C.B., S.M.B., J.J.W., J.C.H., C.H.O., and A.F.J. edited and revised manuscript; R.C.B., S.M.B., J.J.W., J.C.H., C.H.O., and A.F.J. approved final version of manuscript; A.F.J. conceived and designed research; A.F.J. drafted manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Marcus Sikkel (Imperial College, London) for advice and guidance in establishing the coronary artery ligation model of heart failure.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aita Y, Kurebayashi N, Hirose S, Maturana AD. Protein kinase D regulates the human cardiac L-type voltage-gated calcium channel through serine 1884. FEBS Lett 585: 3903–3906, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrade J, Khairy P, Dobrev D, Nattel S. The clinical profile and pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation: relationships among clinical features, epidemiology, and mechanisms. Circ Res 114: 1453–1468, 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjamin EJ, Chen P-S, Bild DE, Mascette AM, Albert CM, Alonso A, Calkins H, Connolly SJ, Curtis AB, Darbar D, Ellinor PT, Go AS, Goldschlager NF, Heckbert SR, Jalife J, Kerr CR, Levy D, Lloyd-Jones DM, Massie BM, Nattel S, Olgin JE, Packer DL, Po SS, Tsang TSM, Van Wagoner DR, Waldo AL, Wyse DG. Prevention of atrial fibrillation: report from a national heart, lung, and blood institute workshop. Circulation 119: 606–618, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.825380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boixel C, Gonzalez W, Louedec L, Hatem SN. Mechanisms of L-type Ca(2+) current downregulation in rat atrial myocytes during heart failure. Circ Res 89: 607–613, 2001. doi: 10.1161/hh1901.096702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boixel C, Tessier S, Pansard Y, Lang-Lazdunski L, Mercadier J-J, Hatem SN. Tyrosine kinase and protein kinase C regulate L-type Ca(2+) current cooperatively in human atrial myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H670–H676, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bond RC, Choisy SCM, Bryant SM, Hancox JC, James AF. Inhibition of a TREK-like K+ channel current by noradrenaline requires both β1- and β2-adrenoceptors in rat atrial myocytes. Cardiovasc Res 104: 206–215, 2014. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bracken N, Elkadri M, Hart G, Hussain M. The role of constitutive PKA-mediated phosphorylation in the regulation of basal I(Ca) in isolated rat cardiac myocytes. Br J Pharmacol 148: 1108–1115, 2006. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryant S, Kimura TE, Kong CHT, Watson JJ, Chase A, Suleiman MS, James AF, Orchard CH. Stimulation of ICa by basal PKA activity is facilitated by caveolin-3 in cardiac ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 68: 47–55, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryant SM, Kong CHT, Watson J, Cannell MB, James AF, Orchard CH. Altered distribution of ICa impairs Ca release at the t-tubules of ventricular myocytes from failing hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol 86: 23–31, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardin S, Guasch E, Luo X, Naud P, Le Quang K, Shi Y, Tardif J-C, Comtois P, Nattel S. Role for MicroRNA-21 in atrial profibrillatory fibrotic remodeling associated with experimental postinfarction heart failure. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 5: 1027–1035, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.112.973214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carnes CA, Janssen PML, Ruehr ML, Nakayama H, Nakayama T, Haase H, Bauer JA, Chung MK, Fearon IM, Gillinov AM, Hamlin RL, Van Wagoner DR. Atrial glutathione content, calcium current, and contractility. J Biol Chem 282: 28063–28073, 2007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704893200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chase A, Colyer J, Orchard CH. Localised Ca channel phosphorylation modulates the distribution of L-type Ca current in cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 49: 121–131, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choisy SCM, Arberry LA, Hancox JC, James AF. Increased susceptibility to atrial tachyarrhythmia in spontaneously hypertensive rat hearts. Hypertension 49: 498–505, 2007. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000257123.95372.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christ T, Boknik P, Wöhrl S, Wettwer E, Graf EM, Bosch RF, Knaut M, Schmitz W, Ravens U, Dobrev D. L-type Ca2+ current downregulation in chronic human atrial fibrillation is associated with increased activity of protein phosphatases. Circulation 110: 2651–2657, 2004. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145659.80212.6A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clarke JD, Caldwell JL, Horn MA, Bode EF, Richards MA, Hall MCS, Graham HK, Briston SJ, Greensmith DJ, Eisner DA, Dibb KM, Trafford AW. Perturbed atrial calcium handling in an ovine model of heart failure: potential roles for reductions in the L-type calcium current. J Mol Cell Cardiol 79: 169–179, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Climent AM, Guillem MS, Fuentes L, Lee P, Bollensdorff C, Fernández-Santos ME, Suárez-Sancho S, Sanz-Ruiz R, Sánchez PL, Atienza F, Fernández-Avilés F. Role of atrial tissue remodeling on rotor dynamics: an in vitro study. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 309: H1964–H1973, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00055.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collins TP, Terrar DA. Ca2+-stimulated adenylyl cyclases regulate the L-type Ca2+ current in guinea-pig atrial myocytes. J Physiol 590: 1881–1893, 2012. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.227066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dibb KM, Clarke JD, Horn MA, Richards MA, Graham HK, Eisner DA, Trafford AW. Characterization of an extensive transverse tubular network in sheep atrial myocytes and its depletion in heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2: 482–489, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.852228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dinanian S, Boixel C, Juin C, Hulot J-S, Coulombe A, Rücker-Martin C, Bonnet N, Le Grand B, Slama M, Mercadier J-J, Hatem SN. Downregulation of the calcium current in human right atrial myocytes from patients in sinus rhythm but with a high risk of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 29: 1190–1197, 2008. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Armouche A, Pamminger T, Ditz D, Zolk O, Eschenhagen T. Decreased protein and phosphorylation level of the protein phosphatase inhibitor-1 in failing human hearts. Cardiovasc Res 61: 87–93, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emelyanova L, Ashary Z, Cosic M, Negmadjanov U, Ross G, Rizvi F, Olet S, Kress D, Sra J, Tajik AJ, Holmuhamedov EL, Shi Y, Jahangir A. Selective downregulation of mitochondrial electron transport chain activity and increased oxidative stress in human atrial fibrillation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 311: H54–H63, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00699.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Everett TH IV, Wilson EE, Verheule S, Guerra JM, Foreman S, Olgin JE. Structural atrial remodeling alters the substrate and spatiotemporal organization of atrial fibrillation: a comparison in canine models of structural and electrical atrial remodeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2911–H2923, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01128.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gadeberg HC, Bryant SM, James AF, Orchard CH. Altered Na/Ca exchange distribution in ventricular myocytes from failing hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 310: H262–H268, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00597.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldstein DS, McCarty R, Polinsky RJ, Kopin IJ. Relationship between plasma norepinephrine and sympathetic neural activity. Hypertension 5: 552–559, 1983. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.5.4.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greiser M, Lederer WJ, Schotten U. Alterations of atrial Ca2+ handling as cause and consequence of atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res 89: 722–733, 2011. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hohendanner F, DeSantiago J, Heinzel FR, Blatter LA. Dyssynchronous calcium removal in heart failure-induced atrial remodeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 311: H1352–H1359, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00375.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishida A, Kameshita I, Okuno S, Kitani T, Fujisawa H. A novel highly specific and potent inhibitor of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 212: 806–812, 1995. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keef KD, Hume JR, Zhong J. Regulation of cardiac and smooth muscle Ca2+ channels (Ca(V)1.2a,b) by protein kinases. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C1743–C1756, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kettlewell S, Burton FL, Smith GL, Workman AJ. Chronic myocardial infarction promotes atrial action potential alternans, afterdepolarizations, and fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res 99: 215–224, 2013. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim SJ, Choisy SC, Barman P, Zhang H, Hancox JC, Jones SA, James AF. Atrial remodeling and the substrate for atrial fibrillation in rat hearts with elevated afterload. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 4: 761–769, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.964783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirstein M, Rivet-Bastide M, Hatem S, Bénardeau A, Mercadier JJ, Fischmeister R. Nitric oxide regulates the calcium current in isolated human atrial myocytes. J Clin Invest 95: 794–802, 1995. doi: 10.1172/JCI117729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kistler PM, Sanders P, Dodic M, Spence SJ, Samuel CS, Zhao C, Charles JA, Edwards GA, Kalman JM. Atrial electrical and structural abnormalities in an ovine model of chronic blood pressure elevation after prenatal corticosteroid exposure: implications for development of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 27: 3045–3056, 2006. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le Grand BL, Hatem S, Deroubaix E, Couétil JP, Coraboeuf E. Depressed transient outward and calcium currents in dilated human atria. Cardiovasc Res 28: 548–556, 1994. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.4.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li D, Fareh S, Leung TK, Nattel S. Promotion of atrial fibrillation by heart failure in dogs: atrial remodeling of a different sort. Circulation 100: 87–95, 1999. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.100.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li D, Melnyk P, Feng J, Wang Z, Petrecca K, Shrier A, Nattel S. Effects of experimental heart failure on atrial cellular and ionic electrophysiology. Circulation 101: 2631–2638, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.101.22.2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lyon AR, MacLeod KT, Zhang Y, Garcia E, Kanda GK, Lab MJ, Korchev YE, Harding SE, Gorelik J. Loss of T-tubules and other changes to surface topography in ventricular myocytes from failing human and rat heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 6854–6859, 2009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809777106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michel JB, Lattion AL, Salzmann JL, Cerol ML, Philippe M, Camilleri JP, Corvol P. Hormonal and cardiac effects of converting enzyme inhibition in rat myocardial infarction. Circ Res 62: 641–650, 1988. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.62.4.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pluteanu F, Hess J, Plackic J, Nikonova Y, Preisenberger J, Bukowska A, Schotten U, Rinne A, Kienitz MC, Schäfer MK-H, Weihe E, Goette A, Kockskämper J. Early subcellular Ca2+ remodelling and increased propensity for Ca2+ alternans in left atrial myocytes from hypertensive rats. Cardiovasc Res 106: 87–97, 2015. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Resjö S, Oknianska A, Zolnierowicz S, Manganiello V, Degerman E. Phosphorylation and activation of phosphodiesterase type 3B (PDE3B) in adipocytes in response to serine/threonine phosphatase inhibitors: deactivation of PDE3B in vitro by protein phosphatase type 2A. Biochem J 341: 839–845, 1999. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rozmaritsa N, Christ T, Van Wagoner DR, Haase H, Stasch JP, Matschke K, Ravens U. Attenuated response of L-type calcium current to nitric oxide in atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res 101: 533–542, 2014. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Russell WMS, Burch RL. The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique. London: Methuen, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schotten U, de Haan S, Neuberger H-R, Eijsbouts S, Blaauw Y, Tieleman R, Allessie M. Loss of atrial contractility is primary cause of atrial dilatation during first days of atrial fibrillation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H2324–H2331, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00581.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simon JN, Ziberna K, Casadei B. Compromised redox homeostasis, altered nitroso-redox balance, and therapeutic possibilities in atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res 109: 510–518, 2016. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvw012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skeberdis VA, Jurevičius J, Fischmeister R. Beta-2 adrenergic activation of L-type Ca2+ current in cardiac myocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 283: 452–461, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steinfath M, Lavicky J, Schmitz W, Scholz H, Döring V, Kalmár P. Regional distribution of β 1- and β 2-adrenoceptors in the failing and nonfailing human heart. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 42: 607–611, 1992. doi: 10.1007/BF00265923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tandan S, Wang Y, Wang TT, Jiang N, Hall DD, Hell JW, Luo X, Rothermel BA, Hill JA. Physical and functional interaction between calcineurin and the cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel. Circ Res 105: 51–60, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.199828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vandecasteele G, Verde I, Rücker-Martin C, Donzeau-Gouge P, Fischmeister R. Cyclic GMP regulation of the L-type Ca2+ channel current in human atrial myocytes. J Physiol 533: 329–340, 2001. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0329a.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verheule S, Wilson E, Banthia S, Everett TH IV, Shanbhag S, Sih HJ, Olgin J. Direction-dependent conduction abnormalities in a canine model of atrial fibrillation due to chronic atrial dilatation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H634–H644, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00014.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y, Wagner MB, Joyner RW, Kumar R. cGMP-dependent protein kinase mediates stimulation of L-type calcium current by cGMP in rabbit atrial cells. Cardiovasc Res 48: 310–322, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(00)00178-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoon N, Cho JG, Kim KH, Park KH, Sim DS, Yoon HJ, Hong YJ, Park HW, Kim JH, Ahn Y, Jeong MH, Park JC. Beneficial effects of an angiotensin-II receptor blocker on structural atrial reverse-remodeling in a rat model of ischemic heart failure. Exp Ther Med 5: 1009–1016, 2013. 10.3892/etm.2013.920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang H, Cannell MB, Kim SJ, Watson JJ, Norman R, Calaghan SC, Orchard CH, James AF. Cellular hypertrophy and increased susceptibility to spontaneous calcium-release of rat left atrial myocytes due to elevated afterload. PLoS One 10: e0144309, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Z-S, Cheng H-J, Onishi K, Ohte N, Wannenburg T, Cheng C-P. Enhanced inhibition of L-type Ca2+ current by β3-adrenergic stimulation in failing rat heart. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 315: 1203–1211, 2005. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.089672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao F, Zhang S, Chen L, Wu Y, Qin J, Shao Y, Wang X, Chen Y. Calcium- and integrin-binding protein-1 and calcineurin are upregulated in the right atrial myocardium of patients with atrial fibrillation. Europace 14: 1726–1733, 2012. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]