MasR deficiency abolishes protection of female mice from obesity-induced hypertension. Male MasR-deficient obese mice have reduced blood pressure and declines in cardiac function. ANG-(1–7) infusion restores obesity-induced cardiac dysfunction of wild-type, but not MasR-deficient, male mice. MasR agonists may be cardioprotective in obese males and females.

Keywords: angiotensin-(1–7), obesity, hypertension

Abstract

Angiotensin-(1–7) [ANG-(1–7)] acts at Mas receptors (MasR) to oppose effects of angiotensin II (ANG II). Previous studies demonstrated that protection of female mice from obesity-induced hypertension was associated with increased systemic ANG-(1–7), whereas male obese hypertensive mice exhibited increased systemic ANG II. We hypothesized that MasR deficiency (MasR−/−) augments obesity-induced hypertension in males and abolishes protection of females. Male and female wild-type (MasR+/+) and MasR−/− mice were fed a low-fat (LF) or high-fat (HF) diet for 16 wk. MasR deficiency had no effect on obesity. At baseline, male and female MasR−/− mice had reduced ejection fraction (EF) and fractional shortening than MasR+/+ mice. Male, but not female, HF-fed MasR+/+ mice had increased systolic and diastolic (DBP) blood pressures compared with LF-fed controls. In HF-fed females, MasR deficiency increased DBP compared with LF-fed controls. In contrast, male HF-fed MasR−/− mice had lower DBP than MasR+/+ mice. We quantified cardiac function after 1 mo of HF feeding in males of each genotype. HF-fed MasR−/− mice had higher left ventricular (LV) wall thickness than MasR+/+ mice. Moreover, MasR+/+, but not MasR−/−, mice displayed reductions in EF from HF feeding that were reversed by ANG-(1–7) infusion. LV fibrosis was reduced in HF-fed MasR+/+ but not MasR−/− ANG-(1–7)-infused mice. These results demonstrate that MasR deficiency promotes obesity-induced hypertension in females. In males, HF feeding reduced cardiac function, which was restored by ANG-(1–7) in MasR+/+ but not MasR−/− mice. MasR agonists may be effective therapies for obesity-associated cardiovascular conditions.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY MasR deficiency abolishes protection of female mice from obesity-induced hypertension. Male MasR-deficient obese mice have reduced blood pressure and declines in cardiac function. ANG-(1–7) infusion restores obesity-induced cardiac dysfunction of wild-type, but not MasR-deficient, male mice. MasR agonists may be cardioprotective in obese males and females.

the etiology of obesity-induced hypertension has not been fully elucidated, which is of concern, since obesity is considered a primary contributor to the increasing prevalence of hypertension. Studies suggest an activated renin-angiotensin system (RAS) as one of the major underlying mechanisms responsible for the development of obesity-induced hypertension in experimental models and humans (4, 13). Moreover, in addition to the classic RAS, alterations in the counterregulatory arm of the system, including angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and the angiotensin-(1–7) [ANG-(1–7)]-Mas receptor (MasR) axis, have been suggested to contribute to obesity-induced hypertension. We demonstrated that adipose tissue RAS components, including ACE2, may contribute to differential susceptibility to obesity-induced hypertension between male and female mice (9, 10). Male obese hypertensive mice exhibited increased plasma angiotensin II (ANG II) concentrations associated with reduced activity of adipose ACE2, whereas obese females exhibited increased adipose ACE2 expression and elevated plasma ANG-(1–7) concentrations that protected against the development of obesity-induced hypertension (10). Increased adipose ACE2 expression in obese females was estrogen mediated, since ovariectomy reduced adipose ACE2 expression and promoted obesity-induced hypertension, both of which were reversed by administration of β-estradiol to ovariectomized obese females (34).

ANG-(1–7), an endogenous ligand of the G protein-coupled MasR, exerts several effects that counterbalance effects of ANG II, including stimulation of nitric oxide release from endothelial cells, resulting in vasodilation (23) and prevention of ANG II-induced pathological remodeling of cardiomyocytes (8). Mice deficient in MasR exhibit impaired heart (6, 24) and endothelial function (15, 36), indicating an important role of the ANG-(1–7)-MasR axis in the regulation of cardiac function and blood pressure. Although MasR-deficient mice fed standard diet have been reported to exhibit elevated blood pressure (36), no studies have examined effects of MasR deficiency on the development of obesity-induced hypertension, even though several studies have linked ANG-(1–7)-MasR effects to improvement of glucose homeostasis (25, 35) and cardiac function (7, 16, 18) in models of type II diabetes (T2D).

In addition to hypertension, obesity is associated with both systolic and diastolic dysfunction of the left ventricle (LV) (2). In a study of 6,076 heart failure patients, the prevalence of obesity in subjects with preserved LV ejection fraction (EF) and subjects with reduced LVEF was 41.4 and 35.5%, respectively (17). While human studies frequently show impaired LV diastolic function with obesity, the effect of obesity on LV systolic function is somewhat controversial (1). Furthermore, while the mortality rate due to cardiovascular disease (CVD) is substantially higher in men than women (22), little is known about the effects of obesity on gender-specific differences in LV function. A recent study reported that gender differences in CVD mortality may be attenuated with obesity (27). In contrast, gender-specific differences in LV remodeling with obesity have been demonstrated in some studies and suggested to contribute to increased cardiovascular mortality rates in men (21). Similar to humans, the effect of obesity on cardiac function in animal models is inconsistent. Some studies report impaired cardiac function (5, 32, 38) while others report normal cardiac function in rodent models of obesity (29, 30). Although obesity-associated cardiac dysfunction is multifactorial, an activated RAS has been suggested to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of LV dysfunction associated with obesity (3, 19).

Previous research in our laboratory demonstrated that pharmacological blockade of MasR eliminated protection of female mice from obesity-induced hypertension (10). These results suggest that ANG-(1–7) activation of MasR may protect females from obesity-induced hypertension. Conversely, in male mice exhibiting obesity-induced hypertension, plasma ANG-(1–7) concentrations were decreased, suggesting that low activity of the ANG-(1–7)-MasR axis may increase susceptibility to obesity-induced hypertension in males (10). In this study, we hypothesized that MasR deficiency will augment obesity-induced hypertension in males and abolish protection of female mice from obesity-induced hypertension. Additionally, to elucidate mechanisms, we defined effects of MasR deficiency on cardiac function in mice with diet-induced obesity.

METHODS

Animals.

All studies using mice were approved by an Institutional Animal Review Committee at the University of Kentucky and were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. MasR heterozygous (MasR+/−) founders on a C57BL/6J (Taconic) background were generated by the trans-NIH Knockout Mouse Project (KOMP) and obtained from the KOMP Repository (http://www.komp.org; Davis, CA). Experimental male and female mice with MasR deficiency (MasR−/−) and wild-type littermate controls (MasR+/+) were generated by breeding MasR+/− male to MasR+/− female mice. At 8–10 wk of age, male and female mice were randomly assigned to either receive high-fat diet (HF; 60% kcal as fat, D12492; Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) or low-fat diet (LF; 10% kcal as fat, D12450B; Research Diets) ad libitum for 16 wk. There were four groups of mice in each sex with n = 6–9 mice/group: MasR+/+, LF; MasR−/−, LF; MasR+/+, HF; and MasR−/−, HF. Body weight was recorded at baseline and every week throughout the studies. At study end point, body composition was quantified in conscious mice by echo-MRI (EchoMRI-100TM; Echo Medical Systems, Houston, TX). In a separate study, 1-mo HF-fed male MasR+/+ and MasR−/− mice (n = 4–5 mice/group) were infused via osmotic minipump (model 2004; Alzet) with ANG-(1–7) (0.4 µg·kg−1·min−1; Bachem, Torrance, CA) (31) for 28 days. At study end point, mice were anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine (100:10 mg/kg ip) for exsanguination and tissue harvest.

Quantification of plasma ANG-(1–7).

Plasma ANG-(1–7) concentrations were quantified as described previously (10, 26) by ELISA using a commercial kit (Peninsula Laboratories) that exhibits minimal cross-reactivity to ANG II. Blood samples were collected via cardiac puncture from anesthetized mice (ketamine-xylazine, 100:10 mg/kg ip) and placed directly in tubes containing EDTA (0.2 M) and the serine protease inhibitor aprotinin (500 KIU/ml) for the separation of plasma.

Quantification of blood pressure.

Blood pressure was quantified by radiotelemetry at week 16 of HF feeding as described previously (37). Briefly, at week 15 of HF feeding, anesthetized (isoflurane to effect) mice were implanted with left carotid artery catheters followed by a 1-wk recovery, and then blood pressure was recorded (sampling every 5 min) for five consecutive days.

Echocardiography.

Echocardiography was performed on isoflurane-anesthetized male and female mice at baseline and before and after ANG-(1–7) infusions (28 days, males). Mice were anesthetized using 2–4% isoflurane at effect according to their size and then transferred to a heated platform (37°C) with 1–2% isoflurane supplied via nose cone. Hair on the chest region was shaved and removed, and electrode cream was applied on the front and hindlimbs before being secured with electrical tape to electrodes on the platform. Respiration rate (RR) and heart rate (HR) were monitored and adjusted to a certain range across all experimental mice by titrating isoflurane levels. An RR of 100 times/min and HR of 400 beats/min were targeted. Images of the cross-sectional view of the LV at the papillary muscle level were obtained in M-mode using an M550 transducer under the cardiology package on a Vevo 2100. Images were analyzed using Vevo 2100 software, and LV trace methodology was chosen for calculation of LVEF.

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging.

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging was performed on desflurane (0.8% at effect in 0.3 l/min of oxygen)-anesthetized male mice (baseline and after 1 mo of HF feeding) with a 7-Tesla Bruker CliScan (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany). Desflurane anesthesia was adjusted to maintain RR of 100 times/min. Core temperature of the mouse was maintained at 37°C with a heated water blanket. Image acquisition has been described elsewhere (12). Images on 9–11 cross section slices with a 1-mm interval were taken to cover the entire mouse heart. Images of end systolic and end diastolic phases of the middle seven cross section slices were used to calculate LVEF. LV wall thickness and dimensions were measured at end diastole to calculate the H-to-R ratio, a measure of structural morphology (H is LV wall thickness, R is radius of the diastolic LV).

Immunohistochemistry and analysis of interstitial collagen content.

Hearts were fixed in 10% formalin, dehydrated in grades of ethanol, and paraffin embedded. Longitudinal sections (5 μm) were prepared from the center of the heart. Sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and incubated with Picro Sirius solution for 1 h. Staining was followed by washing with acidic water, dehydration, and mounting. Images were acquired under bright-field microscopy at ×40 using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope. Interstitial collagen content was quantified by ImageJ software using color thresholding in nine random fields distributed across the LV of each section. Interstitial collagen content is presented as the percentage of pixels with red staining of the total number of pixels per image. Data are reported as the mean percentage of collagen staining per mouse (n = 3 mice/group).

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as means ± SE. Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaStat (SPSS). For two-factor analysis [body weight, fat/lean mass, blood pressure, plasma angiotensins, EF, and fractional shortening (FS)], a two-way ANOVA (genotype and treatment as between-group factors, time as a repeated measure when applicable) was used to analyze end-point measurements followed by Holm-Sidak for post hoc analyses. For data from two groups (cardiac parameters, cardiac collagen), an unpaired Student’s t-test was performed. Values of P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

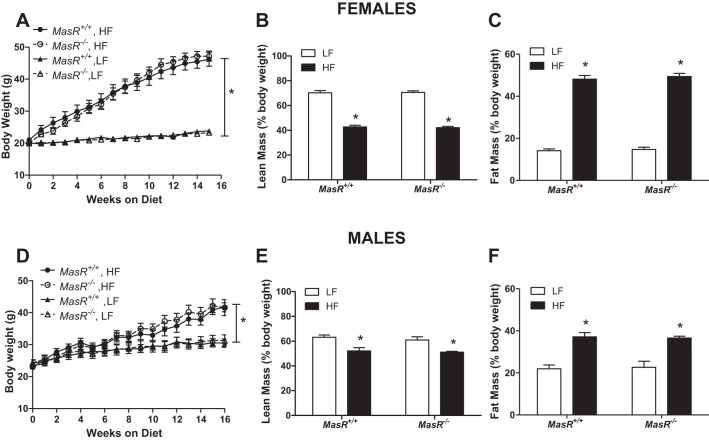

MasR deficiency has no effect on the development of HF diet-induced obesity in female or male mice. There was a significant main effect of diet (male and female, P < 0.001), no significant effect of genotype (female: P = 0.945; male: P = 0.670), and no significant interaction (female: P = 0.971; male: P = 0.995) on body weight (Fig. 1, A and D). Female (Fig. 1A) and male (Fig. 1D) MasR+/+ and MasR−/− mice exhibited significant increases in body weight in response to the HF diet (P < 0.05), with no significant differences between genotypes. Similarly, there was a significant main effect of diet (male and female, P < 0.001), no significant effect of genotype (female: P = 0.163; male: P = 0.877), and no significant interaction (female: P = 0.089; male: P = 0.086) on lean mass (Fig. 1, B and E). For fat mass, there was a significant main effect of diet (male and female, P < 0.001), no significant effect of genotype (female: P = 0.527; male: P = 0.983), and no significant interaction (female: P = 0.820; male: P = 0.827; Fig. 1, C and F). HF feeding resulted in decreased lean mass and increased fat mass (expressed as percentage body weight) in female (P < 0.05; Fig. 1, B and C) and male (P < 0.05; Fig. 1, E and F) mice, with no significant differences between genotypes.

Fig. 1.

Mas receptor (MasR) deficiency has no effect on the development of diet-induced obesity in female or male mice. A and D: body weight of female (A) and male (D) wild-type (MasR+/+) and MasR-deficient (MasR−/−) mice fed a low-fat (LF) or high-fat (HF) diet for 4 mo. B and E: lean mass (%body weight) of female (B) and male (E) MasR+/+ and MasR−/− mice. C and F: fat mass (%body weight) of female (C) and male (F) MasR+/+ and MasR−/− mice fed a LF or HF diet for 4 mo. Data are means ± SE from 8–10 mice per genotype per diet. *P < 0.05 vs. LF within genotype.

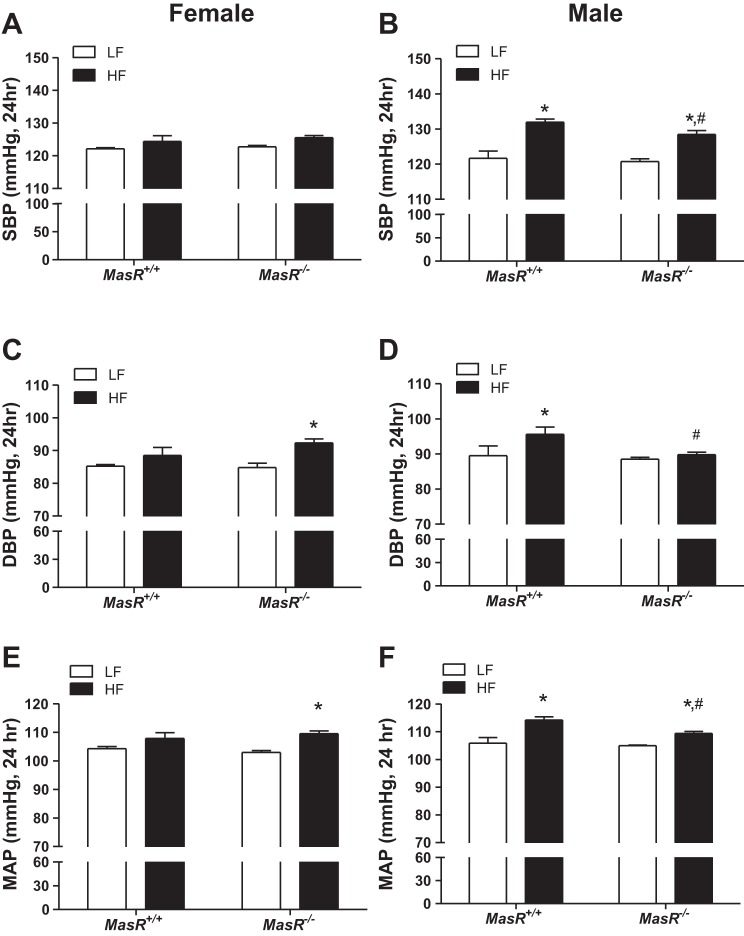

MasR deficiency increases diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of HF-fed female mice but mitigates obesity-induced elevations in blood pressure of HF-fed male mice. For female mice, there was no significant effect of diet (P = 0.468), genotype (P = 0.051), or interaction (P = 0.849) on systolic blood pressure (SBP; Fig. 2A). There was an overall effect of HF diet to increase DBP (24-h average over 5 days; P = 0.007; Fig. 2C) in both MasR+/+ (DBP, by 4% compared with LF) and MasR−/− (DBP, by 8% compared with LF) female mice. Mean arterial pressure (MAP, 24-h average over 5 days, P = 0.003; Fig. 2E) was also increased in both MasR+/+ (MAP, by 4% compared with LF) and MasR−/− females (MAP, by 7% compared with LF). However, statistical analysis indicated significant increases in DBP and MAP in HF compared with LF-fed female MasR−/−, but not MasR+/+, mice (DBP; MasR+/+, P = 0.214, MasR−/−, P = 0.008) (MAP; MasR+/+, P = 0.111, MasR−/−, P = 0.006). Blood pressures (SBP, DBP, MAP) were higher during the dark compared with the light cycle in both MasR+/+ and MasR−/− female mice, regardless of diet group (Table 1). However, only MasR−/− females showed a significant increase in DBP and MAP in response to HF diet in both the light and dark cycle (P < 0.05; Table 1). Moreover, HF-fed MasR−/− female mice had higher dark cycle DBP (P = 0.031) compared with HF-fed MasR+/+ females (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

MasR deficiency increases diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of obese female mice but attenuates obesity-induced increases in DBP of male mice. A and B: systolic blood pressure (SBP, 24-h average) of female (A) and male (B) MasR+/+ and MasR−/− mice fed a LF or HF diet for 4 mo. C and D: DBP (24-h average) of female (C) and male (D) MasR+/+ and MasR−/− mice fed a LF or HF diet. E and F: mean arterial pressure (MAP, 24-h average) of female (E) and male (F) MasR+/+ and MasR−/− mice fed a LF or HF diet. Data are means ± SE from 6–10 mice/genotype/diet. *P < 0.05 vs. LF within genotype. #P < 0.05 compared with MasR+/+ within diet.

Table 1.

Blood pressure parameters of female MasR+/+ and MasR−/− mice fed a LF or HF diet

|

MasR+/+ |

MasR−/− |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LF | HF | LF | HF | |

| 24 Hour | ||||

| Heart rate, beats/min | 611 ± 6 | 626 ± 8 | 595 ± 20 | 620 ± 5 |

| Activity, counts/min | 14.1 ± 2.7 | 5.5 ± 0.5* | 14.5 ± 4.5 | 6.0 ± 0.6* |

| PP, mmHg | 35.1 ± 1.0 | 37.0 ± 1.5 | 36.2 ± 2.2 | 33.1 ± 1.0 |

| Light | ||||

| SBP, mmHg | 116.8 ± 0.5 | 119.4 ± 1.9 | 117.4 ± 0.5 | 121.0 ± 0.6 |

| DBP, mmHg | 80.5 ± 0.8 | 84.8 ± 2.5 | 80.2 ± 1.3 | 88.9 ± 1.0* |

| MAP, mmHg | 99.4 ± 1.1 | 102.8 ± 2.0 | 97.6 ± 0.6 | 105.5 ± 0.7* |

| Dark | ||||

| SBP, mmHg | 127.3 ± 0.6 | 128.5 ± 1.7 | 128.1 ± 0.4 | 131.1 ± 0.6 |

| DBP, mmHg | 89.9 ± 0.4 | 91.4 ± 2.3 | 89.3 ± 1.5 | 96.6 ± 1.3*# |

| MAP, mmHg | 109.2 ± 0.7 | 111.4 ± 2.0 | 108.4 ± 0.8 | 114.4 ± 1.0* |

Data are means ± SE; n = 5–9 mice/diet/genotype. MasR+/+, wild-type Mas receptor (MasR); MasR−/−, MasR deficient; HF, high fat; LF, low fat; PP, pulse pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure.

P < 0.05 compared with LF within genotype following pairwise statistical analysis.

P < 0.05 compared with MasR+/+ within diet group following pairwise statistical analysis.

For male mice, there was a significant main effect of diet (P < 0.001) and genotype (P = 0.049) but no significant interaction (P = 0.315) on SBP (Fig. 2B). In male MasR+/+ mice, HF feeding resulted in significantly elevated 24-h SBP (9% increase; P < 0.001; Fig. 2B), DBP (7% increase; P = 0.023; Fig. 2D), and MAP (8% increase; P = 0.015; Fig. 2F) compared with LF-fed controls, and increases in SBP and MAP were evident during both the dark and light cycle (P < 0.001; Table 2). Similarly, MasR−/− HF-fed male mice exhibited a significant increase in 24-h SBP (7% increase; P < 0.001) and MAP (4% increase; P = 0.023) compared with LF-fed MasR−/− male mice (Fig. 2, B and F, respectively). However, SBP, DBP, and MAP of HF-fed MasR−/− male mice were significantly lower than HF-fed MasR+/+ male mice (P < 0.05; Fig. 2, B, D, and F). In contrast to MasR+/+ male mice, MasR−/− males did not exhibit a significant increase in DBP when challenged with a HF diet (1.6% increase compared with 6.8% increase in MasR+/+ mice; MasR+/+, P = 0.023, MasR−/−, P = 0.596).

Table 2.

Blood pressure parameters of male MasR+/+ and MasR−/− mice fed a LF or HF diet

|

MasR+/+ |

MasR−/− |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LF | HF | LF | HF | |

| 24 Hour | ||||

| Heart rate, beats/min | 571 ± 13 | 585 ± 8 | 550 ± 7 | 582 ± 10* |

| Activity, counts/min | 5.3 ± 1.2 | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.7 | 4.0 ± 0.5 |

| PP, mmHg | 32.0 ± 2.1 | 36.3 ± 1.9 | 32.1 ± 1.3 | 38.6 ± 1.2* |

| Light | ||||

| SBP, mmHg | 115.7 ± 2.6 | 127.0 ± 1.0* | 114.8 ± 0.5 | 124.2 ± 1.1* |

| DBP, mmHg | 85.3 ± 3.3 | 92.1 ± 2.0* | 83.4 ± 0.5 | 87.0 ± 0.8 |

| MAP, mmHg | 100.8 ± 2.7 | 110.0 ± 1.3* | 99.3 ± 0.4 | 105.9 ± 0.8*# |

| Dark | ||||

| SBP, mmHg | 127.5 ± 1.8 | 137.0 ± 0.7* | 126.6 ± 1.3 | 132.7 ± 1.2*# |

| DBP, mmHg | 93.8 ± 2.4 | 99.1 ± 2.2 | 93.6 ± 0.7 | 92.5 ± 0.7 |

| MAP, mmHg | 110.9 ± 1.6 | 118.4 ± 1.2* | 110.5 ± 0.6 | 112.9 ± 0.8# |

Data are means ± SE; n = 5–9 mice/diet/genotype.

P < 0.05 compared with LF within genotype following pairwise statistical analysis.

P < 0.05 compared with MasR+/+ within diet group following pairwise statistical analysis.

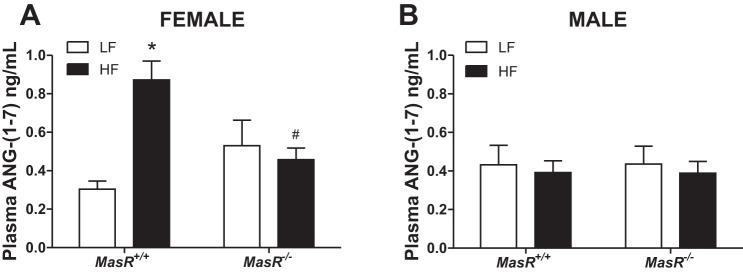

Previous studies demonstrated that HF feeding regulates plasma concentrations of ANG-(1–7) in both male and female mice (10). Therefore, we quantified plasma ANG-(1–7) concentrations in LF- and HF-fed female and male MasR+/+ and MasR−/− mice. There was a significant effect of diet (P = 0.019) and a significant interaction (P = 0.004) on plasma ANG-(1–7) concentrations in females but not in males (Fig. 3, A and B). In females, HF feeding resulted in a significant elevation of plasma ANG-(1–7) concentrations in MasR+/+ but not in MasR−/− mice compared with LF-fed controls (MasR+/+, P < 0.001, MasR−/−, P = 0.616; Fig. 3A). Moreover, plasma ANG-(1–7) concentrations of female HF-fed MasR−/− mice were significantly lower than HF-fed MasR+/+ females (P = 0.009). In male mice, there was no effect of diet or genotype on plasma ANG-(1–7) concentrations (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, plasma ANG-(1–7) concentrations of HF-fed MasR+/+ male mice (Fig. 3B) were lower than those of HF-fed MasR+/+ female mice (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Plasma angiotensin-(1–7) [ANG-(1–7)] concentrations are increased in HF-fed MasR+/+ female, but not male, mice. Plasma ANG-(1–7) concentrations of female (A) and male (B) MasR+/+ and MasR−/− mice fed a LF or HF diet for 4 mo. Data are means ± SE from 6-10 mice/genotype/diet. *P < 0.05 vs. LF within genotype. #P < 0.05 compared with MasR+/+ within diet.

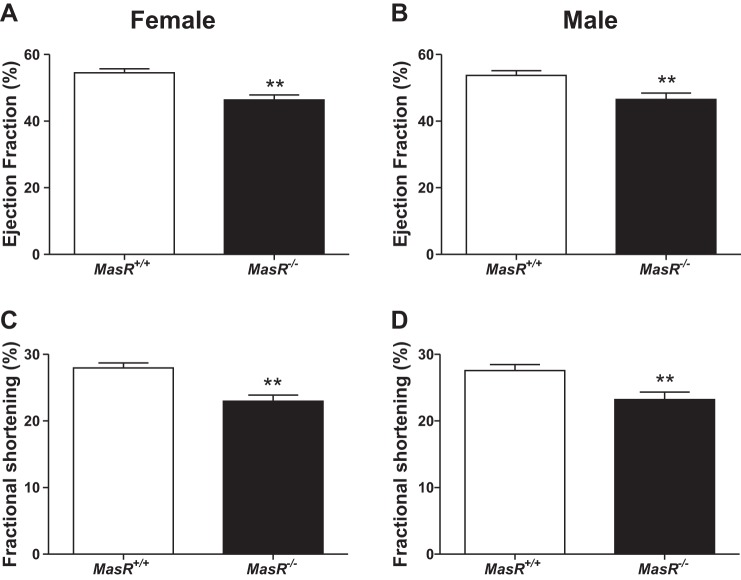

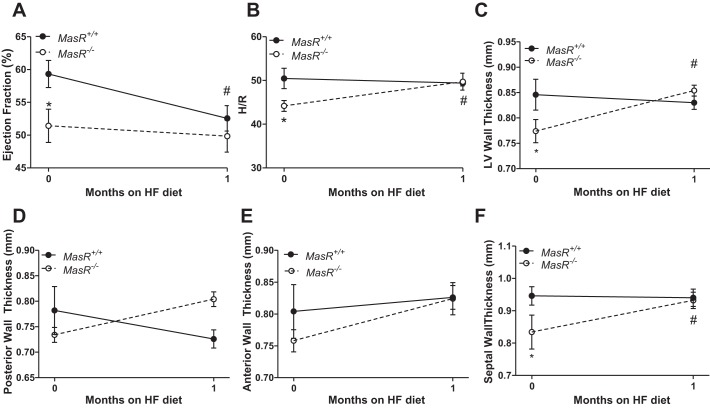

Male MasR−/− mice exhibit reduced LV function and structural remodeling of the heart after 1 mo of HF feeding. We initially assessed LV function by echocardiography in female and male MasR+/+ and MasR−/− mice fed standard murine diet. At baseline, MasR−/− male (P = 0.005) and female (P < 0.001) mice had lower EF and FS than MasR+/+ controls (Fig. 4). We initiated studies in 1-mo HF-fed MasR+/+ and MasR−/− male mice using CMR imaging to quantify cardiac morphology and function. We focused on male mice since plasma ANG-(1–7) concentrations were lower in HF-fed hypertensive males than normotensive females (Fig. 3, A and B), and to identify mechanisms contributing to unexpected reductions in blood pressure of HF-fed MasR−/− compared with MasR+/+ males (Fig. 2D). As demonstrated in Fig. 4A, at baseline (0 time point; Fig. 5A) MasR−/− mice had significantly lower EF than MasR+/+ mice (P = 0.028). This was associated with significantly lower H/R ratios (P = 0.017; Fig. 5B) in MasR−/− males at baseline. LV wall thickness (P = 0.030; Fig. 5C) and septal wall thickness (P = 0.045; Fig. 5F) were also significantly lower in MasR−/− mice compared with MasR+/+ mice at baseline.

Fig. 4.

MasR-deficient female and male mice exhibit reduced left ventricular (LV) function at baseline. Assessment of LV function in female and male MasR+/+ and MasR−/− mice at baseline by echocardiography. A and B: ejection fraction (EF) of female (A) and male (B) MasR+/+ and MasR−/− mice. C and D: fractional shortening (FS) of female (C) and male (D) MasR+/+ and MasR−/− mice fed standard murine diet. Data are means ± SE from 8–10 mice/genotype. **P < 0.01 compared with MasR+/+ mice.

Fig. 5.

MasR−/− male mice exhibit higher LV wall thickening than MasR+/+ mice after 1 mo of HF feeding. Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging was performed on male MasR+/+ and MasR−/− mice before and after 1 mo of HF feeding. A: EF. B: ratio of LV wall thickness (H) to diastolic LV radius (R). C: LV wall thickness. D: posterior wall thickness. E: anterior wall thickness. F: septal wall thickness. Data are means ± SE from 5 mice/genotype. *P < 0.05 compared with MasR+/+ mice within time point. #P < 0.05 compared with baseline within genotype.

There was a significant main effect of diet (P = 0.035) on EF in MasR+/+, but not MasR−/−, mice (Fig. 5A). At 1 mo of HF feeding, EF was decreased significantly compared with baseline in MasR+/+ (P = 0.019), but not in MasR−/−, mice (P = 0.515; Fig. 5A). Furthermore, in response to HF feeding, MasR−/−, but not MasR+/+, mice displayed an increase in the H/R ratio (P = 0.043; Fig. 5B) that was associated with increased LV wall (P = 0.005; Fig. 5C) and septal wall (P = 0.007; Fig. 5F) thickness. Additionally, there was a trend to increase posterior and anterior wall thickness in MasR−/− mice after 1 mo of HF feeding (Fig. 5, D and E). Changes in wall thickness of MasR−/− mice in response to HF feeding were observed in the absence of cardiac hypertrophy, since there was no difference in heart weight (MasR+/+: 0.15 ± 0.1 g; MasR−/−: 0.15 ± 0.01 g, P = 0.502) or heart weight as a percentage of body weight (MasR+/+: 0.33 ± 0.01%; MasR−/−: 0.37 ± 0.02%, P = 0.119) between genotypes after 1 mo of HF feeding.

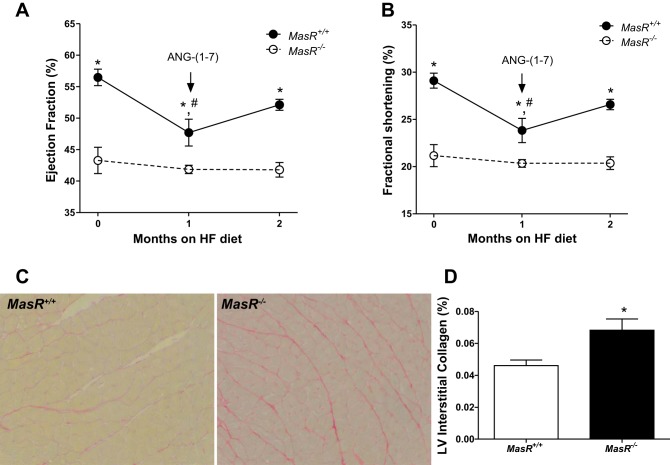

ANG-(1–7) infusion restores LV function of HF-fed male MasR+/+ but not MasR−/− mice. Because EF was decreased in male MasR+/+ mice after 1 mo of HF feeding, we determined if these reductions were mediated through an ANG-(1–7)/MasR pathway. For these studies, we initiated ANG-(1–7) infusions at 1 mo of HF feeding in both genotypes, which was continued for an additional month while mice remained on the HF diet. There was a significant main effect of time (P < 0.001) and genotype (P < 0.001) but no significant interaction (P = 0.054) on EF in MasR+/+, but not MasR−/−, mice (Fig. 6A). Similar results were obtained for FS (Fig. 6B). MasR+/+, but not MasR−/−, mice had significant reductions in EF and FS after 1 mo of HF feeding (P < 0.001 and P = 0.002; Fig. 6, A and B). In MasR+/+ mice, infusion of ANG-(1–7) for 1 mo restored EF and FS to baseline levels (Fig. 6, A and B). As expected, ANG-(1–7) infusion had no effect on EF or FS in HF-fed MasR−/− mice.

Fig. 6.

ANG-(1–7) infusion reduces LV fibrosis and restores LV function of HF-fed male MasR+/+ mice but has no effect on these parameters in HF-fed MasR−/− mice. ANG-(1–7) was infused to male mice via subcutaneous osmotic minipump at 1 mo of HF feeding for 28 days; LV function was assessed by echocardiography. A and B: EF (A) and FS (B) of HF-fed MasR+/+ and MasR−/− mice before and after ANG-(1–7) infusion. Data are means ± SE from 5 mice/genotype. *P < 0.05 compared with MasR−/− mice within time point. #P < 0.05 vs. 0 time point within genotype. C and D: interstitial collagen content is higher in HF-fed MasR−/− than MasR+/+ mice infused with ANG-(1–7). Representative images (×40) of Picro Sirius-stained sections (C) and quantification (D) of interstitial collagen content in the LV wall. Data are means ± SE from the average of 9 fields/mouse and 3 mice/group. *P < 0.05 compared with MasR+/+ mice.

MasR deficiency is associated with extracellular matrix deposition in the heart (6), and ANG-(1–7) administration has been reported to reduce cardiac fibrosis in animal models of T2D (7, 16, 18). Therefore, we assessed cardiac fibrosis by measuring interstitial LV collagen content of HF-fed MasR+/+ and MasR−/− mice following ANG-(1–7) infusions. Following ANG-(1–7) infusion, collagen content was significantly higher in LV from MasR−/− than MasR+/+ mice (P = 0.047; Fig. 6, C and D).

DISCUSSION

MasR, the receptor for endogenous ANG-(1–7), plays an important role in maintaining blood pressure homeostasis in several experimental animal models (11, 33, 36). Although MasR deficiency in mice fed standard murine diet results in impaired heart and endothelial function, its effects on blood pressure are inconsistent (24, 33, 36). We demonstrated previously that obese female mice exhibit increased plasma ANG-(1–7) concentrations that protect females from obesity-induced hypertension through MasR activation (10). Whereas this finding suggested a possible role of MasR in obesity-induced hypertension in female mice, no studies have examined the effect of MasR deficiency on the development of obesity-induced hypertension in male or female mice. The results of this study demonstrate that MasR is a critical determinant of cardiovascular health in male and female mice fed standard murine diet, as well as in mice with diet-induced obesity. The major findings of the present study are 1) MasR deficiency resulted in increased DBP and promoted obesity-induced hypertension of female mice, 2) in contrast, MasR-deficient male mice had attenuated blood pressure responses to obesity, 3) MasR-deficient mice of either sex had reduced LV function at baseline; reductions in LV function of male MasR−/− mice were associated with reduced H/R ratios, 4) 1 mo of HF feeding reduced LV function of male MasR+/+ mice while resulting in structural remodeling of LVs from MasR−/− mice, and 5) ANG-(1–7) infusion restored HF diet-induced deficits in LV function and reduced cardiac fibrosis of MasR+/+, but not MasR−/−, mice.

Previous studies demonstrated an important role of the counterregulatory arm of the RAS, the ACE2-ANG-(1–7)-MasR axis, in the development of experimental obesity-induced hypertension. Obese male mice exhibiting reduced kidney ACE2 activity and elevated plasma ANG II concentrations compared with LF controls were susceptible to obesity-induced hypertension, whereas obese female mice exhibiting increased adipose ACE2 activity and plasma ANG-(1–7) concentrations compared with LF controls were resistant to obesity-induced hypertension (10). Notably, ovariectomy (OVX) reduced plasma ANG-(1–7) concentrations and conferred obesity-induced hypertension of female mice. Moreover, administration of 17β-estradiol lowered both plasma ANG II concentrations and blood pressure of HF-fed OVX female Ace2+/+ but not Ace2−/− mice (34). These results suggest that activity levels of ACE2, potentially adipose-derived ACE2, influence the ANG II/ANG-(1–7) balance and the development of hypertension in response to obesity. Moreover, previous results suggest that male and female mice exhibit sexual dimorphism of the ACE2-ANG-(1–7) pathway that may differentially influence obesity-induced hypertension. Results from this study are the first to demonstrate that endogenous ANG-(1–7) acts at MasR to protect obese females from obesity-induced hypertension. Notably, similar to our findings in obese female mice, previous studies demonstrated that plasma ANG-(1–7) concentrations are higher in women (nonobese) than men (28). In contrast to the hypertensive phenotype caused by either ACE2 deficiency or OVX reported previously in obese female mice (10), in this study, MasR deficiency did not increase SBP of obese female mice. Recent results indicate that the ANG-(1–7)-MasR axis may play an important role in autonomic modulation of arterial pressure (20), supporting more prominent effects of MasR deficiency to modulate DBP rather than SBP. Taken together, these results suggest that previously observed effects of ACE2 deficiency or OVX to increase SBP of obese females may have resulted from increased systemic or local concentrations of ANG II, rather than changes of the ANG-(1–7)-MasR axis.

Surprisingly, MasR deficiency in obese male mice did not augment the development of hypertension. Rather, SBP, DBP, and MAP were reduced in obese MasR−/− compared with MasR+/+ mice. Moreover, obesity-induced elevations in DBP of MasR+/+ mice were absent in obese MasR−/− mice. In agreement with previous findings (6, 24, 36), in this study MasR-deficient male mice fed standard murine diet exhibited impaired cardiac function. Moreover, our results extend previous findings by demonstrating that female MasR-deficient mice also exhibit deficits of cardiac function. Because male mice have been reported to exhibit elevations in plasma ANG II concentrations with obesity while females do not (9), it is possible that chronic increases in the ANG II/ANG-(1–7) balance of male obese MasR-deficient mice following long-term HF feeding contribute to deficits in cardiac function and reduced blood pressure.

In humans, obesity has been reported to promote hemodynamic alterations that influence cardiac morphology and predispose obese people to heart failure (14). Obese subjects are frequently reported to exhibit elevated LV filling pressure, which results in LV hypertrophy and subsequent LV diastolic dysfunction, LV systolic dysfunction, or both (14). In this study, use of CMR in male mice revealed that the reduction in LVEF of MasR−/− mice was associated with a reduced end-diastolic H/R ratio, a measure of heart thickness to radius, at baseline compared with MasR+/+ mice. Interestingly, 1 mo of HF feeding increased the H/R ratio of MasR−/− mice, consistent with an increase in wall thickness, but did not alter EF. These results suggest that MasR-deficient mice initially respond to HF challenge through compensatory remodeling of the LV. As a result, MasR−/− mice maintained EF, whereas MasR+/+ mice exhibited reductions in EF with HF feeding (despite an unaltered H/R ratio). Whereas these changes in cardiac function of MasR-deficient mice in response to HF diet may appear beneficial, MasR-deficient mice fed standard murine diet were reported to express increased extracellular matrix components in AV valves and myocardium that were associated with reduced cardiac performance (6). Because MasR−/− mice have lower LV function at baseline compared with wild-type controls, and LV remodeling is an early sign of dysfunction in heart failure, these data suggest an accelerated pathological LV remodeling early in response to HF feeding in MasR−/− mice.

Although 1 mo of HF feeding did not further impair LV function of male MasR−/− mice, male MasR+/+ mice exhibited reduced LV function in response to HF feeding. To define mechanisms, we infused ANG-(1–7) to HF-fed wild-type and MasR-deficient males. We chose a dose of ANG-(1–7) that has been reported to significantly increase plasma concentrations of ANG-(1–7) in mice (31). Infusion of ANG-(1–7) to HF-fed MasR+/+ male mice restored LV function to baseline levels and reduced interstitial cardiac fibrosis but had no effect on these parameters in HF-fed MasR−/− male mice. These data agree with recent studies in which long-term administration of ANG-(1–7) to db/db mice reduced cardiac oxidative stress, inflammation, fibrosis, and pathological remodeling (18). Moreover, these results suggest therapeutic benefits of ANG-(1–7) administration on cardiac dysfunction associated with obesity.

In summary, results from this study support the hypothesis that endogenous ANG-(1–7) acts at MasR to protect females from obesity-induced hypertension. In contrast, MasR-deficient obese male mice exhibited lower cardiac function at baseline and paradoxical reductions in blood pressure with chronic HF feeding. Notably, obesity-induced reductions in LV function of male mice were restored by infusion of ANG-(1–7), suggesting that reduced activity of the ANG-(1–7)-MasR axis may contribute to heart failure with obesity. Taken together, these results indicate that MasR is a critical determinant of cardiac health in both male and female lean and obese mice. Results from this study suggest that novel drugs that are able to activate MasR may afford extra benefits in obese hypertensive patients with cardiac complications.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant HL-073085 (to L. Cassis), through Cores supported by NIH Grant GM-103527 (to L. Cassis), and by an American Heart Association Grant (14PRE20380163).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.W., D.P., W.S., and S.E.T. performed experiments; Y.W. and D.P. analyzed data; Y.W., R.S., and L.A.C. interpreted results of experiments; Y.W., R.S., and L.A.C. prepared figures; Y.W., R.S., S.E.T., and L.A.C. edited and revised manuscript; Y.W., R.S., D.P., W.S., S.E.T., and L.A.C. approved final version of manuscript; R.S. and L.A.C. drafted manuscript; L.A.C. conceived and designed research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alpert MA, Lavie CJ, Agrawal H, Aggarwal KB, Kumar SA. Obesity and heart failure: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Transl Res 164: 345–356, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alpert MA, Lavie CJ, Agrawal H, Kumar A, Kumar SA. Cardiac Effects of Obesity: PATHOPHYSIOLOGIC, CLINICAL, AND PROGNOSTIC CONSEQUENCES-A REVIEW. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 36: 1–11, 2016. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barretti DL, Magalhães FC, Fernandes T, do Carmo EC, Rosa KT, Irigoyen MC, Negrão CE, Oliveira EM. Effects of aerobic exercise training on cardiac renin-angiotensin system in an obese Zucker rat strain. PLoS One 7: e46114, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boustany CM, Bharadwaj K, Daugherty A, Brown DR, Randall DC, Cassis LA. Activation of the systemic and adipose renin-angiotensin system in rats with diet-induced obesity and hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R943–R949, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00265.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong F, Li Q, Sreejayan N, Nunn JM, Ren J. Metallothionein prevents high-fat diet induced cardiac contractile dysfunction: role of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma coactivator 1alpha and mitochondrial biogenesis. Diabetes 56: 2201–2212, 2007. doi: 10.2337/db06-1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gava E, de Castro CH, Ferreira AJ, Colleta H, Melo MB, Alenina N, Bader M, Oliveira LA, Santos RA, Kitten GT. Angiotensin-(1–7) receptor Mas is an essential modulator of extracellular matrix protein expression in the heart. Regul Pept 175: 30–42, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giani JF, Muñoz MC, Mayer MA, Veiras LC, Arranz C, Taira CA, Turyn D, Toblli JE, Dominici FP. Angiotensin-(1–7) improves cardiac remodeling and inhibits growth-promoting pathways in the heart of fructose-fed rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H1003–H1013, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00803.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomes ER, Lara AA, Almeida PW, Guimarães D, Resende RR, Campagnole-Santos MJ, Bader M, Santos RA, Guatimosim S. Angiotensin-(1–7) prevents cardiomyocyte pathological remodeling through a nitric oxide/guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate-dependent pathway. Hypertension 55: 153–160, 2010. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.143255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupte M, Boustany-Kari CM, Bharadwaj K, Police S, Thatcher S, Gong MC, English VL, Cassis LA. ACE2 is expressed in mouse adipocytes and regulated by a high-fat diet. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R781–R788, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00183.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupte M, Thatcher SE, Boustany-Kari CM, Shoemaker R, Yiannikouris F, Zhang X, Karounos M, Cassis LA. Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 contributes to sex differences in the development of obesity hypertension in C57BL/6 mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32: 1392–1399, 2012. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.248559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kangussu LM, Guimaraes PS, Nadu AP, Melo MB, Santos RA, Campagnole-Santos MJ. Activation of angiotensin-(1–7)/Mas axis in the brain lowers blood pressure and attenuates cardiac remodeling in hypertensive transgenic (mRen2)27 rats. Neuropharmacology 97: 58–66, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim D, Gilson WD, Kramer CM, Epstein FH. Myocardial tissue tracking with two-dimensional cine displacement-encoded MR imaging: development and initial evaluation. Radiology 230: 862–871, 2004. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2303021213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotchen TA. Obesity-related hypertension: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical management. Am J Hypertens 23: 1170–1178, 2010. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Ventura HO. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: risk factor, paradox, and impact of weight loss. J Am Coll Cardiol 53: 1925–1932, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemos VS, Silva DM, Walther T, Alenina N, Bader M, Santos RA. The endothelium-dependent vasodilator effect of the nonpeptide Ang(1–7) mimic AVE 0991 is abolished in the aorta of mas-knockout mice. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 46: 274–279, 2005. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000175237.41573.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mori J, Patel VB, Abo Alrob O, Basu R, Altamimi T, Desaulniers J, Wagg CS, Kassiri Z, Lopaschuk GD, Oudit GY. Angiotensin 1–7 ameliorates diabetic cardiomyopathy and diastolic dysfunction in db/db mice by reducing lipotoxicity and inflammation. Circ Heart Fail 7: 327–339, 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 355: 251–259, 2006. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papinska AM, Soto M, Meeks CJ, Rodgers KE. Long-term administration of angiotensin (1–7) prevents heart and lung dysfunction in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes (db/db) by reducing oxidative stress, inflammation and pathological remodeling. Pharmacol Res 107: 372–380, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel VB, Mori J, McLean BA, Basu R, Das SK, Ramprasath T, Parajuli N, Penninger JM, Grant MB, Lopaschuk GD, Oudit GY. ACE2 Deficiency Worsens Epicardial Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Cardiac Dysfunction in Response to Diet-Induced Obesity. Diabetes 65: 85–95, 2016. doi: 10.2337/db15-0399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabello Casali K, Ravizzoni Dartora D, Moura M, Bertagnolli M, Bader M, Haibara A, Alenina N, Irigoyen MC, Santos RA. Increased vascular sympathetic modulation in mice with Mas receptor deficiency. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 17: 1470320316643643, 2016. doi: 10.1177/1470320316643643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rider OJ, Lewandowski A, Nethononda R, Petersen SE, Francis JM, Pitcher A, Holloway CJ, Dass S, Banerjee R, Byrne JP, Leeson P, Neubauer S. Gender-specific differences in left ventricular remodelling in obesity: insights from cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Heart J 34: 292–299, 2013. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Adams RJ, Berry JD, Brown TM, Carnethon MR, Dai S, de Simone G, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Greenlund KJ, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Ho PM, Howard VJ, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Makuc DM, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McDermott MM, Meigs JB, Moy CS, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Rosamond WD, Sorlie PD, Stafford RS, Turan TN, Turner MB, Wong ND, Wylie-Rosett J, Roger VL, Turner MB; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics–2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 123: e18–e209, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sampaio WO, Souza dos Santos RA, Faria-Silva R, da Mata Machado LT, Schiffrin EL, Touyz RM. Angiotensin-(1–7) through receptor Mas mediates endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation via Akt-dependent pathways. Hypertension 49: 185–192, 2007. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000251865.35728.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santos RA, Castro CH, Gava E, Pinheiro SV, Almeida AP, Paula RD, Cruz JS, Ramos AS, Rosa KT, Irigoyen MC, Bader M, Alenina N, Kitten GT, Ferreira AJ. Impairment of in vitro and in vivo heart function in angiotensin-(1–7) receptor MAS knockout mice. Hypertension 47: 996–1002, 2006. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000215289.51180.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santos SH, Giani JF, Burghi V, Miquet JG, Qadri F, Braga JF, Todiras M, Kotnik K, Alenina N, Dominici FP, Santos RA, Bader M. Oral administration of angiotensin-(1–7) ameliorates type 2 diabetes in rats. J Mol Med (Berl) 92: 255–265, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-1087-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shoemaker R, Yiannikouris F, Thatcher S, Cassis L. ACE2 deficiency reduces β-cell mass and impairs β-cell proliferation in obese C57BL/6 mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 309: E621–E631, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00054.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song X, Tabák AG, Zethelius B, Yudkin JS, Söderberg S, Laatikainen T, Stehouwer CD, Dankner R, Jousilahti P, Onat A, Nilsson PM, Satman I, Vaccaro O, Tuomilehto J, Qiao Q; DECODE Study Group . Obesity attenuates gender differences in cardiovascular mortality. Cardiovasc Diabetol 13: 144, 2014. doi: 10.1186/s12933-014-0144-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sullivan JC, Rodriguez-Miguelez P, Zimmerman MA, Harris RA. Differences in angiotensin (1–7) between men and women. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 308: H1171–H1176, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00897.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sung MM, Koonen DP, Soltys CL, Jacobs RL, Febbraio M, Dyck JR. Increased CD36 expression in middle-aged mice contributes to obesity-related cardiac hypertrophy in the absence of cardiac dysfunction. J Mol Med (Berl) 89: 459–469, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0720-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thakker GD, Frangogiannis NG, Bujak M, Zymek P, Gaubatz JW, Reddy AK, Taffet G, Michael LH, Entman ML, Ballantyne CM. Effects of diet-induced obesity on inflammation and remodeling after myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2504–H2514, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00322.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thatcher SE, Zhang X, Howatt DA, Lu H, Gurley SB, Daugherty A, Cassis LA. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 deficiency in whole body or bone marrow-derived cells increases atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor−/− mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31: 758–765, 2011. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.221614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turdi S, Kandadi MR, Zhao J, Huff AF, Du M, Ren J. Deficiency in AMP-activated protein kinase exaggerates high fat diet-induced cardiac hypertrophy and contractile dysfunction. J Mol Cell Cardiol 50: 712–722, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walther T, Wessel N, Kang N, Sander A, Tschöpe C, Malberg H, Bader M, Voss A. Altered heart rate and blood pressure variability in mice lacking the Mas protooncogene. Braz J Med Biol Res 33: 1–9, 2000. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2000000100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Y, Shoemaker R, Thatcher SE, Batifoulier-Yiannikouris F, English VL, Cassis LA. Administration of 17β-estradiol to ovariectomized obese female mice reverses obesity-hypertension through an ACE2-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 308: E1066–E1075, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00030.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams IM, Otero YF, Bracy DP, Wasserman DH, Biaggioni I, Arnold AC. Chronic Angiotensin-(1–7) Improves Insulin Sensitivity in High-Fat Fed Mice Independent of Blood Pressure. Hypertension 67: 983–991, 2016. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu P, Costa-Goncalves AC, Todiras M, Rabelo LA, Sampaio WO, Moura MM, Santos SS, Luft FC, Bader M, Gross V, Alenina N, Santos RA. Endothelial dysfunction and elevated blood pressure in MAS gene-deleted mice. Hypertension 51: 574–580, 2008. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.102764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yiannikouris F, Karounos M, Charnigo R, English VL, Rateri DL, Daugherty A, Cassis LA. Adipocyte-specific deficiency of angiotensinogen decreases plasma angiotensinogen concentration and systolic blood pressure in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 302: R244–R251, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00323.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, Yuan M, Bradley KM, Dong F, Anversa P, Ren J. Insulin-like growth factor 1 alleviates high-fat diet-induced myocardial contractile dysfunction: role of insulin signaling and mitochondrial function. Hypertension 59: 680–693, 2012. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.181867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]