Abstract

Background: Overweight is epidemic in adolescents and is a major concern because it tracks into adulthood. Evidence supports the efficacy of high-calcium, high-dairy diets in achieving healthy weight in adults. However, no randomized controlled trials of the effect of dairy food on weight and body fat in adolescents have been reported to our knowledge.

Objective: The aim was to determine whether increasing calcium intake to recommended amounts with dairy foods in adolescent girls with habitually low calcium intakes would decrease body fat gain compared with girls who continued their low calcium intake. Participants had above-the-median body mass index (BMI; in kg/m2).

Design: We enrolled 274 healthy postmenarcheal 13- to 14-y-old overweight girls who had calcium intakes of ≤600 mg/d in a 12-mo randomized controlled trial. Girls were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to 1 of 2 groups within each of 3 BMI percentiles: 50th to <70th, 70th to <85th, and 85th to <98th. The assignments were 1) dairy, which included low-fat milk or yogurt servings providing ≥1200 mg Ca/d or 2) control, which included the usual diet of ≤600 mg Ca/d.

Results: We failed to detect a statistically significant difference between groups in percentage of body fat gain over 12 mo (mean ± SEM: dairy 0.40% ± 0.53% > control; P < 0.45). The effect of the intervention did not differ by BMI percentile stratum. There was no difference in weight change between the 2 groups.

Conclusion: Our findings that the dairy group gained body fat similar to the control group provide no support for dairy food as a stratagem to decrease body fat or weight gain in overweight adolescent girls. This trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT01066806.

Keywords: percentage of body fat, weight, adolescence, dietary calcium intake, dairy foods, girls

See corresponding editorial on page 1025.

INTRODUCTION

An urgent need exists to identify modifiable dietary risk factors for obesity, which has become a major health threat around the world. Overweight is epidemic in children and adolescents as well as in adults. Estimates from NHANES are that 31.8% of US children and adolescents are overweight or obese (1). This is a major concern because overweight in childhood and adolescence tracks into adulthood and is associated with high rates of adult obesity and related comorbidity (2). Adolescence is recognized as a critical period for the development and persistence of overweight (3, 4).

Because of concerns about weight gain (5, 6) and the trend of greater intakes of soft drinks (7), the median dairy intake for adolescent girls is only 1.2 servings/d (8). The average calcium intake is 777 mg/d (9), considerably lower than recommendations of 1300 mg Ca/d (10) and 3 servings of dairy food/d (11, 12). Thus, the promotion of an adequate intake of dairy foods has been proposed as a stratagem for decreasing overweight. Considerable evidence exists for the efficacy of a diet high in calcium, particularly dairy foods, in preventing overweight and facilitating weight loss in adults (13–15). Although some observational studies suggest that dairy and calcium intake modulate weight in children and adolescents (16–19), others do not support these findings (20–22). We found no published reports of randomized controlled trials (RCTs)6 that examined the effect of dairy foods or calcium supplementation on weight and body fat as the primary outcome in adolescents.

A proposed mechanism for the antiobesity effect of dietary calcium is that intracellular ionized calcium plays a key role in the regulation of adipocyte metabolism by modulating adipocyte triglyceride stores. Because calciotropic hormones regulate intracellular calcium, suppression of these hormones by increasing dietary calcium may result in redirecting dietary energy from adipose tissue to lean body mass and thermogenesis (23–25). Calcium in the form of dairy food appears to be more effective than calcium supplements. Another factor that may contribute to the negative relation between calcium and weight is that dietary calcium in the gastrointestinal tract leads to precipitation of insoluble fatty acid–calcium soaps making fat less available for absorption (26). Lastly, ingesting food of a mixed nutrient composition, such as milk, may lead to greater energy expenditure and feelings of satiety than ingesting sugar-only food (27).

An effective dairy intervention would be an economic, low-risk stratagem in prevention of adiposity (28). Thus, the purpose of this 1-y randomized, controlled clinical trial was to determine whether increasing calcium intake to recommended levels with dairy foods in adolescent girls with habitually low calcium intake and above-the-median BMI (in kg/m2) for sex and age would decrease body fat gain compared with similar girls who continued their low calcium intake.

METHODS

Participants

Recruitment for the study started in May 2008. We enrolled 274 healthy girls aged 13 or 14 y and ≥1.5 y postmenarche in a 12-mo RCT. Other inclusion criteria included habitual dietary calcium intake of ≤600 mg/d, willingness to increase dietary calcium intake (low-fat milk or yogurt) for 1 y, and BMI >50th and <98th percentiles for age and sex based on CDC growth curves. We enrolled girls above the median BMI because most of the increase in BMI is seen in the heaviest portion of the pediatric population (29). For potential subjects >85th percentile for BMI, their primary care providers were contacted for approval before we enrolled the girl in the study. Exclusion criteria included menarche before age 10 y; history of lactose intolerance or milk allergy; dieting behavior with weight loss >4.5 kg in the last 3 mo; weight >136 kg or metal in the skeleton (pins, rods) because of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) limitations; current pregnancy; chronic disease or disorder, such diabetes, polycystic ovarian syndrome, thyroid disease, eating disorder, seizures, or cancer; and use of steroids, contraceptives, antidepressants, Accutane, high-dose Vitamin A, or weight-reducing or seizure medications. A total body bone mineral content (BMC) z score <−2.0 measured by DXA was exclusionary, as was the individual’s or a sibling’s participation in a dietary study in the last 5 y.

Participants were recruited from the community by using a wide range of methods, such as direct mailing to parents, advertisements in the media, flyers placed in various community locations, and recruitment collaboration with schools, health care providers, and the Girl Scouts. Extensive efforts were made to recruit girls from all racial-ethnic groups in the community. Interested families were encouraged to call the research center at which time a telephone screening was completed to determine eligibility. Those who passed the telephone screening were mailed a 3-d diet diary, which was completed and returned. If eligible by dietary analysis, the girl and her parent were scheduled for a screening study visit.

The Creighton University Institutional Review Board approved the protocol. Written, informed assent and consent were obtained from the participants and parents or guardians, respectively. Study visits were conducted at 3-mo intervals for a total of 5 visits.

Anthropometric and body composition measurements

These measurements were obtained at baseline, 6 mo, and end of study (12 mo). Fat mass was assessed as a primary outcome, whereas BMC was monitored for safety in light of the low calcium intake of the control group. If any participants showed a BMC z score <−2.0, they were withdrawn from study and referred to their primary care provider, but no participant fell to <−2.0. Lean mass was an exploratory outcome.

Participants were given a set of surgical scrubs to wear to all study visits for consistency during weight and DXA measurements, and shoes were removed. Total body fat mass, lean mass, and BMC were measured with DXA by using a Discovery 4500A densitometer (Hologic Inc.). Scans were done following the manufacturer’s guidelines for patient positioning and in compliance with the International Society of Clinical Densitometry guidelines. All scans were analyzed by using Hologic software release 12.3. To improve DXA precision, we scanned each study participant 2 times at baseline and at the final visit and used the average of the 2 scans as the value. By using that approach, short-term precision of percentage of body fat in our center in adolescents aged 13–16 y is 1.4%, leading to an operational least significant change of 1.1% of body fat (30).

Weight was measured with an electronic scale that is accurate to ±0.l kg and weights ≤400 kg (Scale-Tronix Inc.). The scale was calibrated daily. Two measurements were obtained, and if the difference between the 2 values was >1.0 kg, a third measurement was taken and the average of the 2 closest values was used (31). A wall-mounted Harpenden stadiometer was used to measure each participant’s height. Calibration with a measuring stick was done daily. Two measurements of height were obtained, and if the difference between the 2 values was >1.0 cm, a third measurement was taken and the average of the 2 closest values was used. The reliability of the stadiometer at our center is 0.9995.

To determine changes in abdominal fat deposition, abdominal girth was assessed by using an abdominal caliper (Seritex Inc.). Girth was determined with the participant lying supine on the DXA table. The calipers were placed under the lumbar spine and positioned so that the measurement was obtained just above the iliac crest at approximately the level of the L4–L5 space. Participants were instructed to inhale and exhale gently. The measurement was taken to the nearest 0.1 cm. The abdominal caliper was calibrated daily with an inflexible rod of known size.

Waist and hip circumferences were also measured to characterize changes in fat deposition. The average of 2 readings was recorded. Measurements were obtained in accordance with WHO standards (31, 32) by using a Gulick II Tape Measure (HOSPEQ Inc.). Measurements were made to the nearest 1.0 cm. Waist circumference was obtained midway between the lateral lower rib margin and the iliac crest at midexhalation with the participant in the standing position. Hip circumference was obtained while the participant was standing and at the point yielding the maximum circumference over the buttocks.

Pubertal status was determined at baseline and the end of the study by using Tanner staging of the breast (33) to use as a potential cofactor in the analyses. The Tanner stages range from 1 to 5, with 1 being no pubertal development and 5 being the adult level of development. An endocrinologist and a registered nurse with extensive training and experience with Tanner staging performed the assessments.

Assessment of dietary calcium intake and physical activity

These assessments were completed at baseline and every 3 mo. Dietary intake was assessed with the multiple-pass 3-d dietary recall by using the Nutrition Data System for Research software, supported and updated by the Nutrition Coordinating Center at the University of Minnesota. Research dietitians and nurses administering the dietary recalls attended training sessions at the University of Minnesota and obtained certification to use the Nutrition Data System for Research. Three recalls were obtained, 1 on a weekend day and 1 on each of 2 weekdays, and the average of the 3 recalls was recorded as the intake at that visit. Before the first recall was administered, food models were used to teach each participant how to estimate portion sizes. During the recall, the participants were prompted to list in sequence the foods and beverages consumed during the previous day and then provide details, such as portion sizes and brand names, concerning each reported item. Intake was reviewed and confirmed at the end of each recall.

Usual physical activity was assessed by using the Modifiable Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents (34–37). The questionnaire provides an estimation of participants’ total daily energy expenditure. It combines dimensions of intensity, duration, and frequency of activity into a single measure, metabolic equivalents.

Intervention for dairy calcium

The study statistician (DJM) used a computer-generated scheme to randomly assign eligible girls in a 1:1 ratio to 1 of 2 groups within each of 3 BMI percentile categories: 50th to <70th, 70th to <85th, and 85th to <98th. The intervention assignments were 1) the dairy group, asked to consume low-fat (skim, 1%, or 2%) milk or low-fat yogurt servings providing ≥1200 mg Ca/d, or 2) the control group, asked to continue on their usual diet of ≤600 mg Ca/d. The girls were asked to avoid taking calcium supplements during the study. The study nurses enrolled participants and assigned them to the intervention group. Study visits were held in the Creighton University Osteoporosis Research Center. Participants and their parents selected and purchased the yogurt and milk and submitted the receipts for reimbursement by the study funds. All participants in the dairy and control groups were given a gift card at each visit 2 through 5. Before random assignment, all eligible girls who consented to the study were enrolled in a 2-wk pretreatment phase, or run-in, during which they were asked to consume 4 servings low-fat milk or yogurt/d. This was done to reduce dropout rates after random assignment. During these 2 wk, we identified and removed from the study those who were <85% adherent to the prescribed dietary intervention. After random assignment, the study dietitian met with each participant and her parent(s) to instruct on details of the intervention. The goal for the dairy group and their parent(s) was to teach them about the calcium content of various milk and yogurt products and to counsel the girls about ways to include the dairy into their diets without increasing calories. The goal for the control group was to advise them about consuming a well-balanced diet that provides adequate essential nutrients, while keeping fats and calories within the recommended levels. The girls and their parent(s) were informed that their calcium intake was below that recommended for bone health, and they were provided information about sources of dietary calcium. Each participant in the dairy group was asked to record the type and number of dairy servings each day. The study nurse and research dietitian reviewed the diaries of participants in each group, Dairy and Control, at each study visit to assess compliance and provide review of the protocol as needed. In addition, diet recall data were reviewed monthly by the study nurse and principal investigator to identify any girl in either group who was noncompliant. The study nurse reinforced the dietary goals with noncompliant girls. The final study visit was completed on 21 September 2013.

Statistical analysis

All continuous variables were tested for normality and transformed before analysis when indicated. Differences from baseline were calculated for all primary, secondary, and exploratory outcomes.

An intent-to-treat analysis used a mixed-model analysis of variance in which the 1-y change from baseline was modeled by the fixed effects of treatment assignment (dairy compared with control), BMI-percentile stratum (50th < 70th compared with 70th < 85th compared with 85th < 98th), and their interaction. The primary outcome was change in percentage of body fat, whereas secondary outcomes were change in BMI percentile and weight. Trunk fat mass, percentage of trunk fat, and lean mass were exploratory outcomes. For secondary and exploratory outcomes, the baseline level of the dependent variable was added to the model as a continuous covariate. Because 5 subjects failed to provide endpoint data, we evaluated the missing data mechanism (38) and determined the data met criteria for missing at random. We therefore performed a multiple imputation with fully conditional specification and the predictive mean-matching method (39, 40), with 20 burn-in iterations and 5 imputations, where the imputation model was identical to the analytic model, and adjusted df were used for inferential testing (41).

To further assess the between-group difference in the within-subject trajectory of the raw value of a dependent variable over the course of the year, we used a linear mixed model for repeated measures with fixed effects for treatment assignment (dairy compared with control), time (0, 6, and 12 mo), and assignment-by-time interaction. The covariance structure for the autocorrelation of the repeated measures was assessed before inferential testing, and either an autoregressive (42) or spatial-linear structure was found to fit all variables tested. The primary, secondary, and exploratory outcomes above were tested with this approach. Spearman correlations among various diet nutrient levels and body composition outcomes were explored.

Results in the tables are presented as means ± SDs and in Results as means ± SEMs in the units indicated. P values for fixed effects of group and group-by-time interaction are reported whereas differences between times within groups or between groups at a specific time are model-estimated differences based on simultaneous 95% CIs by using a Scheffé adjustment. No adjustment for multiple comparisons was made for the assessment of different outcomes.

This study was designed to detect a 2.8% between-group difference in percentage of body fat measured at 1 y and assumed a 4% SD with 90% power, a 5% type I error rate, and a 2-factor fixed-effects ANOVA with covariate adjustment for baseline percentage of body fat correlating with outcome at an r value of 0.50. The design called for 2 arms, dairy compared with control, and 3 baseline BMI-percentile strata to form a 3 × 2 six-cell design. Sample size calculations under these assumptions required 38 participants/cell for a total of 228 participants. The recruitment goal was expanded to 274 participants to accommodate a projected 20% attrition rate.

RESULTS

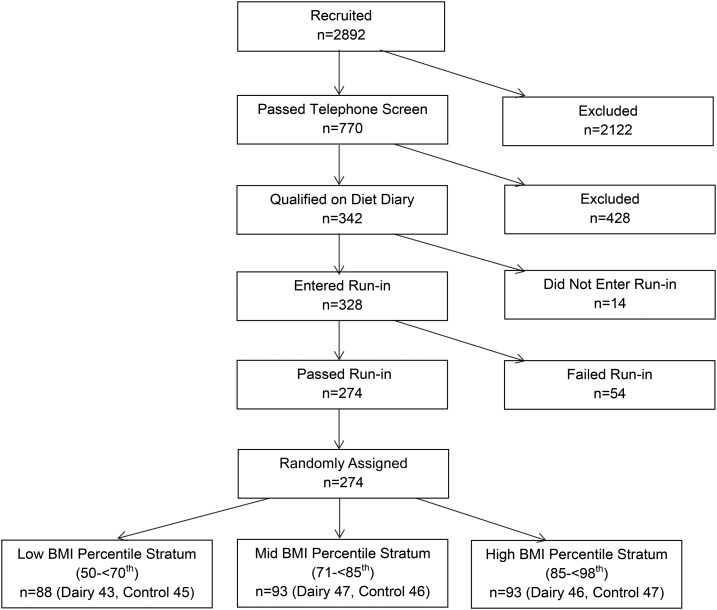

The analyses included a baseline of 274 participants (Figure 1). Five participants dropped out from the study, 4 from the dairy group and 1 from the control group, and 1 control did not have a final DXA because of pregnancy. One control had no DXA at visits 3 and 4 because she missed those visits. Baseline characteristics by the randomly assigned groups are shown in Table 1. The groups were generally well balanced at baseline with respect to anthropometry, diet, and physical activity. There were more Caucasians and a clinically small 1.7-cm-greater hip circumference in the dairy group. Race and ancestry were determined by self-report of each girl and her parent(s). Seven in the control group (5.1%) and 12 in the dairy group (8.8%) reported Hispanic ancestry. All but 11 of 138 (8%) in the control group and 20 of 136 (15%) in the dairy group started the study at Tanner stage 5. In each group, all but one of the remaining girls advanced to Tanner stage 5. There were no study-related adverse events.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of the progress through the phases of the parallel randomized trial of the 2 groups.

TABLE 1.

Participant characteristics at baseline1

| Dairy (n = 136) | Control (n = 138) | |

| Age, y | 13.5 ± 0.5 | 13.5 ± 0.5 |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 119 (87.5) | 104 (75.4) |

| African American | 13 (9.6) | 19 (13.8) |

| Other | 4 (2.9) | 15 (10.8) |

| Height, cm | 162.6 ± 5.5 | 162.2 ± 6.1 |

| BMI percentile, n (%) | 80.9 ± 11.9 | 80.0 ± 12.0 |

| 50th to <70th | 43 (31.6) | 45 (32.6) |

| 70th to <85th | 47 (34.6) | 46 (33.3) |

| 85th to <98th | 46 (33.8) | 47 (34.1) |

| Weight, kg | 61.2 ± 8.5 | 60.4 ± 9.0 |

| Body lean mass, kg | 40.2 ± 4.6 | 40.1 ± 4.9 |

| Body fat mass, kg | 17.7 ± 5.4 | 17.0 ± 5.3 |

| Trunk fat mass, kg | 7.25 ± 2.84 | 7.01 ± 2.84 |

| Body fat, % | 30.2 ± 5.6 | 29.3 ± 5.3 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 77.3 ± 7.3 | 77.1 ± 8.0 |

| Hip circumference, cm | 94.8 ± 6.3 | 93.1 ± 7.3 |

| Abdominal girth, cm | 16.9 ± 2.0 | 16.8 ± 1.9 |

| Menarcheal age, y | 11.6 ± 0.7 | 11.6 ± 0.8 |

| Tanner Stage 5, n (%) | 116 (85.3) | 125 (91.9) |

| Physical activity, METs/d | 44.9 ± 15.1 | 44.7 ± 14.0 |

| Milk, servings/d | 0.58 ± 0.46 | 0.56 ± 0.44 |

| Yogurt, servings/d | 0.05 ± 0.13 | 0.05 ± 0.14 |

| Total dairy, servings/d | 0.63 ± 0.50 | 0.61 ± 0.45 |

| Dietary calcium, mg/d | 552 ± 173 | 531 ± 156 |

| Energy, kcal/d | 1390 ± 340 | 1441 ± 358 |

| Calories from protein, % | 14.8 ± 3.4 | 14.6 ± 3.5 |

| Calories from carbohydrates, % | 53.0 ± 6.4 | 52.5 ± 6.8 |

| Calories from fat, % | 32.2 ± 4.8 | 32.8 ± 5.3 |

| Calories from sugar | 342 ± 130 | 349 ± 138 |

Values are means ± SDs unless otherwise indicated. MET, metabolic equivalent.

Over the 12 mo of the study the dairy group averaged an intake of 1518 mg Ca/d, whereas the control group averaged 752 mg Ca/d from all food sources. All but 13 of the girls who completed 1 y of dairy intervention averaged ≥1200 mg Ca/d. Those who consumed <1200 mg Ca/d all averaged >1000 mg Ca/d except for 3. Although no participants took calcium supplements, 50 girls reported taking a multiple vitamin that included calcium on ≥1 visit. The mean calcium supplement dosage for an individual girl over the course of the study ranged from 1 to 350 mg/d. The overall mean intake during 1 y in girls taking supplementation was 93 mg Ca/d.

Average within-subject values at baseline and 6 and 12 mo for anthropometrics, nutrient intake, and physical activity are shown in Table 2. Height, abdominal girth, and waist and hip circumferences did not change differentially by treatment group. As anticipated, total dairy servings (milk and yogurt) was greatly increased in the dairy group and unchanged in the control group. Increased dairy servings translated into a near 3-fold increase in daily calcium intake in the dairy group. An increase in total energy intake (kilocalories per day) was greater in the dairy group than the control, and this difference was established by month 6 of the study. This difference in energy intake manifested as a greater intake in percentage of calories from protein and a lesser intake in percentage of calories from fat in the dairy relative to the control group. The percentage of calories from carbohydrates was unchanged and similar in the groups over the study. Energy expenditure from physical activity (metabolic equivalents per day) did not differ between groups.

TABLE 2.

Average within-subject change over 12 study months1

| Study month |

||||

| 0 (n = 274) | 6 (n = 269) | 12 (n = 269) | P2 | |

| Height, cm | ||||

| Dairy | 162.6 ± 8.3 | 163.2 ± 8.3 | 163.6 ± 8.3 | 0.50 |

| Control | 162.2 ± 8.2 | 162.7 ± 8.2 | 163.1 ± 8.2 | 0.65 |

| Waist circumference, cm | ||||

| Dairy | 77.3 ± 13.1 | 78.2 ± 13.4 | 78.1 ± 13.3 | 0.44 |

| Control | 77.1 ± 13.0 | 77.2 ± 13.1 | 77.2 ± 13.1 | 0.36 |

| Hip circumference, cm | ||||

| Dairy | 94.9 ± 10.5 | 95.5 ± 10.6 | 95.6 ± 10.6 | 0.07 |

| Control | 93.1 ± 10.4 | 94.1 ± 10.5 | 94.4 ± 10.4 | 0.56 |

| Abdominal girth, cm | ||||

| Dairy | 16.9 ± 3.3 | 17.0 ± 3.4 | 16.8 ± 3.4 | 0.78 |

| Control | 16.8 ± 3.1 | 16.9 ± 3.3 | 16.7 ± 3.3 | 0.91 |

| Total dairy, servings/d | ||||

| Dairy | 0.63 ± 1.89 | 3.26 ± 1.95*,a | 3.16 ± 1.94*,a | <0.001 |

| Control | 0.61 ± 1.88 | 0.77 ± 1.89b | 0.73 ± 1.88b | <0.001 |

| Calcium intake, g/d | ||||

| Dairy | 552 ± 729 | 1526 ± 752*,a | 1513 ± 747*,a | <0.001 |

| Control | 531 ± 724 | 768 ± 730*,b | 723 ± 727*,b | <0.001 |

| Calories from protein, % | ||||

| Dairy | 14.8 ± 8.0 | 17.6 ± 8.2*,a | 16.9 ± 8.2*,a | <0.001 |

| Control | 14.6 ± 7.9 | 15.1 ± 8.0b | 14.9 ± 7.9b | <0.001 |

| Calories from carbohydrates, % | ||||

| Dairy | 53.0 ± 15.1 | 52.6 ± 15.6 | 53.7 ± 15.5 | 0.08 |

| Control | 52.5 ± 15.0 | 51.8 ± 15.2 | 52.1 ± 15.1 | 0.56 |

| Calories from fat, % | ||||

| Dairy | 32.2 ± 12.7 | 30.0 ± 13.1*,a | 29.5 ± 13.0*,a | <0.001 |

| Control | 32.8 ± 12.6 | 33.1 ± 12.7b | 33.1 ± 12.6b | 0.002 |

| Calories from sugars, % | ||||

| Dairy | 24.4 ± 14.5 | 29.3 ± 15.0*,a | 28.7 ± 14.9*,a | <0.001 |

| Control | 24.0 ± 14.4 | 23.1 ± 14.5b | 23.3 ± 14.5b | <0.001 |

| Energy, kcal/d | ||||

| Dairy | 1390 ± 884 | 1818 ± 915*,a | 1821 ± 907*,a | 0.001 |

| Control | 1441 ± 877 | 1609 ± 886*,b | 1638 ± 881*,b | <0.001 |

| Physical activity, METs/wk | ||||

| Dairy | 44.9 ± 28.8 | 42.4 ± 29.1 | 40.2 ± 29.8 | 0.47 |

| Control | 44.9 ± 28.7 | 42.6 ± 28.7 | 42.9 ± 29.6 | 0.33 |

Values are means ± SDs. Linear mixed model for repeated measures with fixed effects for group, time, and interaction. Means within a time interval not sharing a common superscript letter are statistically different at P < 0.05 based on model-estimated differences by using simultaneous confidence limits and the Scheffé correction (see Statistical analysis). *P < 0.05, different from baseline. MET, metabolic equivalent.

P value for the effect of group above the P value for the effect of group × time interaction.

Primary intention-to-treat analysis

The primary intent-to-treat analysis showed that the dairy group gained 0.40% ± 0.53% more body fat than the control group (P = 0.45; 95% CI: −0.63%, 1.43%). The direction and magnitude of the treatment effect on the other outcomes were similar: BMI percentile, the dairy group declined 1.14 ± 1.57 percentile points more than the control group (P = 0.47; 95% CI: −1.94, 4.22 percentile points); weight, the dairy group gained 0.31 ± 0.54 kg more than the control group (P = 0.58; 95% CI: −0.90, 1.44 kg); lean mass, the dairy group gained 51 ± 352 g more than the control group (P = 0.89; 95% CI: −638, 741 g); trunk fat mass, the dairy group increased 175 ± 269 g more than the control group (P = 0.52; 95% CI: −354, 704 g); and trunk percentage of fat, the dairy group increased 0.27% ± 0.60% more than the control group (P = 0.66; 95% CI: −0.90%, 1.44%). The interaction of the treatment group with the baseline BMI-percentile stratum did not achieve statistical significance for any of these outcomes.

Exploratory analyses

Because the intervention included both milk and yogurt, we performed regression analyses by BMI-percentile stratum for milk and yogurt separately in the cohort and found no evidence that the effects of milk differed from yogurt on change in percentage of body fat or weight.

Categorical primary outcomes

Our original power and sample size analysis hypothesize that increasing calcium intake would result in a reduction in percentage of body fat of 2.8% points, and that change would imply a 0.5-kg relative reduction in weight. We assessed the group difference in the distribution of those achieving these categorical outcomes. In the control group 11 (8.2%) lost ≥2.8% of body fat after 12 mo, whereas 7 (5.3%) in the dairy group achieved this level of loss, P = 0.59. For weight, 37 (27.0%) in the control group and 20 (15.2%) in the dairy group lost ≥0.5 kg after 12 mo, P < 0.04.

DISCUSSION

Based on our literature review, this is the first report of an RCT designed to study the effects of increasing calcium from dairy food on changes in percentage of body fat or weight in adolescents. Findings from our study do not support the hypothesis that consuming dairy foods providing ≥1200 mg Ca/d would result in a smaller increase in percentage of body fat than consuming a diet of ≤600 mg Ca/d. In fact, we found that girls in both the dairy and control groups experienced an increase in percentage of body fat. Similarly, there was no difference in weight gain between the dairy and control groups.

Our findings are supported by a study by Weaver et al. (43) who found that doubling calcium intake with calcium carbonate or dairy calcium in overweight adolescents had no effect on energy balance. Furthermore, the mechanisms they evaluated provided no support for effects of dietary calcium on energy balance that would result in changes in body weight when controlling for energy intake and physical activity. No differences were found in energy, apparent fat, or nitrogen balances from either intervention either in the whole group or when stratified by BMI. In our cohort and that of Weaver et al. (43), participants and the intervention dose of calcium was similar and the baseline calcium intake was low. Thus, our findings are supported by a lack of mechanisms for a calcium/dairy effect on weight in adolescents.

Numerous retrospective, prospective, and cross-sectional studies have evaluated the effects of calcium supplements and/or dairy food on indexes of obesity in children and adolescents as reviewed by Van Loan (44). Many but not all of the 15 studies found that calcium or dairy intake is inversely associated with indexes of adiposity. Others found no such association, whereas only one study reported an increase in adiposity with increased dairy. A later review that had some overlap with that of Van Loan (44) synthesized findings of 23 cross-sectional and 13 prospective studies of the effect of calcium and/or dairy on weight and body composition (45). This review concluded that the evidence for the effects of milk intake on body weight and composition in children and adolescents are neutral.

Randomized trials in children and adolescents in which adiposity indexes were evaluated as secondary outcomes generally do not support the hypothesis of decreasing weight or fat gain. Eight trials with a dairy intervention found no significant effect on weight or fat change when measured (46–52). The study by Merrilees et al. (47), which used a design similar to our study, found in a secondary analysis no effects of dairy on gain in body fat. In contrast, one of the dairy trials in children aged 2.5–8.8 y found that increasing dairy calcium by ∼600 mg/d for 6 mo resulted in significantly lower gain in body fat mass (∼1.5 kg) than in a control group (53). In their review, Lanou and Barnard (54) found 18 RCTs that gave calcium supplement pills (n = 11) or dairy treatments (n = 7) to children and adolescents with bone accretion as a primary outcome and adiposity indexes as a secondary outcome. None of these found a statistically significant effect (positive or negative) of calcium on body weight or body fat when measured. Thus, observational studies of the effects of dairy and calcium on a change in weight or body fat in children and adolescents are equivocal and do not strongly support or dispute our findings. However, it is well accepted that RCTs provide a higher level of evidence than observational studies, and the RCTs with body weight as a secondary outcome find no effects. Our well-designed RCT validates those secondary findings.

Interest in the relation between calcium and dairy and weight arose from studies in adults. Several RCTs reported weight and fat loss with added dairy or calcium (55–58), whereas others found no effect (59–63). In a review of those trials, Van Loan (44) noted that 3 important elements distinguished the positive trials from the others: 1) all participants were overweight or obese: 2) baseline calcium intake was low (<600 mg/d); and 3) a moderate kilocalorie restriction was imposed on all participants. Although our study of adolescents included overweight participants with low baseline calcium intakes, it did not include a kilocalorie deficit as part of the intervention, which one might speculate as a reason our findings conflict with findings in adults.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include the randomized clinical trial of postmenarcheal girls who were above the median weight and of similar ages and had low usual dietary calcium and dairy intake. Total nutrient intake was determined with the multipass dietary recall and analyzed with the Nutrition Data System for Research. Pubertal stage was assessed by experienced clinicians. Potential confounders for increase in body fat and weight were assessed and included in the analyses. Study dropouts were minimal (<2% of those enrolled).

Limitations include the inclusion of both milk and yogurt in the intervention because it is difficult to sort out whether both dairy products have the same effect on body fat and weight. Although we used a highly recommended method, dietary recall is known to be problematic. Similarly, self-report of physical activity has limitations. There is also potential bias because of the lack of blinding of the intervention group. The dairy group received free milk and yogurt as a supplement to their diet, whereas the control group received only advice about consuming a well-balanced diet with adequate nutrients, fats, and calories within the recommended levels. Finally, the dairy group completed daily recording of dairy intake whereas the control group did nothing comparable, which may create a bias in that the dairy group focused more on their intake.

Conclusion

The findings from this study provide no support for increasing calcium intake from low-fat milk and yogurt as a stratagem to decrease gain in body fat or weight in adolescent girls who are above the median BMI. However, the importance of adequate calcium intake in adolescent girls must be emphasized because ∼45% of bone accrual occurs during early adolescence (64). This time period provides a limited window of opportunity for maximizing peak bone mass, which is a major determinant of low-trauma fractures, a major public health problem in adults. In addition to calcium, dairy foods are an excellent source of protein, fat, carbohydrates, and phosphorus and contain essential minerals such as magnesium, potassium, and trace elements such as zinc (65).

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff members in the Osteoporosis Research Center who worked to complete the study: L Danis, C Dummer, J Larsen, K Rafferty, and J Stubby.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—–JML, DJM, and AL: designed the research; JML, DJM, AL, JCD, MB, and MS: conducted the research; JML and DJM: analyzed the data and had primary responsibility for the final content; and all authors: wrote the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript. None of the authors reported a conflict of interest related to the study.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: BMC, bone mineral content; DXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA 2014;311:806–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ludwig DS, Pereira M, Kroenke CH, Hilner JE, Van Horn L, Slattery ML, Jacobs DR Jr.. Dietary fiber, weight gain, and cardiovascular disease risk factors in young adults. JAMA 1999;282:1539–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dietz WH. Overweight in childhood and adolescence. N Engl J Med 2004;350:855–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lissau I, Overpeck MD, Ruan WJ, Due P, Holstein BE, Hediger ML; Health Behaviour in School-aged Children Obesity Working Group. Body mass index and overweight in adolescents in the 13 European countries, Israel, and the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004;158:27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Packard P, Krogstrand K. Half of rural girls aged 8 to 17 years report weight concerns and dietary changes, with both more prevalent with increased age. J Am Diet Assoc 2002;102:672–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barr SI. Dieting attitudes and behavior in urban high school students: implications for calcium intake. J Adolesc Health 1995;16:458–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.French SA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Fulkerson J, Hannan P. Fast food restaurant use among adolescents: association with nutrient intake, food choices and behavioral and psychosocial variables. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001;25:1823–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.USDA. 1994–96, 1998 Continuing survey of food intakes by individuals and 1994–96 diet and health knowledge survey [Internet]. [cited 2016 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/food-surveys-research-group/docs/csfii-1994-96-1998-information-collected/.

- 9.McDowell M, Briefel R, Alaimo K, Bischof AM, Caughman CR, Carroll MD, Loria CM, Johnson CL. Energy and macronutrient intakes of persons ages 2 months and over in the United States: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Phase 1, 1988-91. Adv Data 1994; 255:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Academy Pediatrics. Recommendations for daily calcium needs [Internet]. [cited 2016 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/aap-press-room-media-center/Pages/Media-Kit-Nutrition.aspx.

- 11.USDA Food Guidance System. MyPyramid [Internet]. [cited 2016 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.cnpp.usda.gov/FGP.

- 12.Gidding SS, Dennison BA, Birch LL, Daniels SR, Gillman MW, Lichtenstein AH, Rattay KT, Steinberger J, Stettler N, Van Horn L, et al. Dietary recommendations for children and adolescents. A guide for the practitioner: consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2005;112:2061–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Astrup A, Chaput JP, Gilbert JA, Lorenzen JK. Dairy beverages and energy balance. Physiol Behav 2010;100:67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Onakpoya IJ, Perry R, Zhang J, Ernst E. Efficacy of calcium supplementation for management of overweight and obesity: systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Nutr Rev 2011;69:335–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Oliveira EP, Diegoli AC, Corrente JE, McLellan KC, Burini RC. The increase of dairy intake is the main dietary factor associated with reduction of body weight in overweight adults after lifestyle change program. Nutr Hosp 2015;32:1042–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Novotny R, Daida YG, Acharya S, Grove JS, Vogt TM. Dairy intake is associated with lower body fat and soda intake with greater weight in adolescent girls. J Nutr 2004;134:1905–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olivares S, Kain J, Lera L, Pizarro F, Vio F, Moron C. Nutritional status, food consumption and physical activity among Chilean school children: a descriptive study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2004;58:1278–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barba G, Troiano E, Russo P, Venezia A, Siani A. Inverse association between body mass and frequency of milk consumption in children. Br J Nutr 2005;93:15–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rockett HR, Berkey CS, Field AE, Colditz GA. Cross-sectional measurement of nutrient intake among adolescents in 1996. Prev Med 2001;33:27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berkey CS, Rockett HR, Willett WC, Colditz GA. Milk, dairy fat, dietary calcium and weight gain. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159:543–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin BH, Huang CL, French SA. Factors associated with women’s and children’s body mass indices by income status. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2004;28:536–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lorenzen JK, Molgaard C, Michaelsen KF, Astrup A. Calcium supplementation for 1 y does not reduce body weight or fat mass in young girls. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zemel MB, Kim JH, Woychik RP, Michaud EJ, Kadwell SH, Patel IR, Wilkison WO. Agouti regulation of intracellular calcium: role in the insulin resistance of viable yellow mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995;92:4733–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xue B, Greenberg A, Kraemer F, Zemel M. Mechanism of intracellular calcium inhibition of lipolysis in human adipocytes. FASEB J 2001;15:2527–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Claycombe KJ, Wang Y, Jones BH, Kim S, Wilkison WO, Zemel MB, Chun J, Moustaid-Moussa N. Transcriptional regulation of the adipocyte fatty acid synthase gene by the agouti gene product: interaction with insulin. Physiol Genomics 2000;3:157–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papakonstantinou E, Flatt W, Huth P, Harris R. High dietary calcium reduces body fat content, digestibility of fat and serum vitamin D in rats. Obes Res 2003;11:387–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.St-Onge MP, Rubiano F, DeNino WF, Jones A Jr, Greenfield D, Ferguson PW, Akrabawi S, Heymsfield SB. Added thermogenic and satiety effects of a mixed nutrient vs a sugar-only beverage. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2004;28:248–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCarron DA, Heaney RP. Estimated healthcare savings associated with adequate dairy food intake. Am J Hypertens 2004;17:88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Troiano RP, Flegal KM. Overweight children and adolescents: description, epidemiology, and demographics. Pediatrics 1998;101:497–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fleiss J. The design and analysis of clinical experiments. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 31.WHO. Measuring obesity: classification and description of anthropometric data. Report on a WHO consultation of the epidemiology of obesity. Copenhagen (Denmark): WHO; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heitmann BL, Fredriksen P, Lissner L. Hip circumference and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in men and women. Obes Res 2004;12:482–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in patterns of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child 1969;44:291–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aaron DJ, Kriska AM, Dearwater SR, Cauley JA, Metz KF, LaPorte RE. Reproducibility and validity of an epidemiologic questionnaire to assess past year physical activity in adolescents. Am J Epidemiol 1995;142:191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thumboo J, Fong KY, Chan SP, Leong KH, Thio ST, Boey ML. A prospective study of factors affecting quality of life in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2000;27:1414–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gordon-Larsen P, McMurray RG, Popkin BM. Determinants of adolescent physical activity and inactivity patterns. Pediatrics 2000;105:E83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valdimarsson O, Kristinsson JO, Stefansson SO, Valdimarsson S, Sigurdsson G. Lean mass and physical activity as predictors of bone mineral density in 16-year old women. J Intern Med 1999;245:489–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubin D. Inference and missing data. Biometrika 1976;63:581–92. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heitjan D, Roderick JAL. Multiple imputation for the Fatal Accident Reporting System. Appl Stat 1991;40:13–29. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schenker N, Taylor J. Partially parametric techniques for multiple imputation. Comput Stat Data Anal 1996;22:425–46. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barnard J, Rubin DB. Miscellanea. Small-sample degrees of freedom with multiple imputation. Biometrika 1999;86:948–55. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear mixed models for longitudinal data. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weaver CM, Campbell WW, Teegarden D, Craig BA, Martin BR, Singh R, Braun MM, Apolzan JW, Hannon TS, Schoeller DA, et al. Calcium, dairy products, and energy balance in overweight adolescents: a controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94:1163–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Loan M. The role of dairy foods and dietary calcium in weight management. J Am Coll Nutr 2009;28(Suppl 1):120S–9S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spence LA, Cifelli CJ, Miller GD. The role of dairy products in healthy weight and body composition in children and adolescents. Curr Nutr Food Sci 2011;7:40–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chan G, Hoffman K, McMurray M. The effect of dietary calcium supplementation on pubertal girls’ growth and bone mineral status. J Pediatr 1995;125:551–6. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Merrilees MJ, Smart EJ, Gilchrist NL, Frampton C, Turner JG, Hooke E, March RL, Maguire P. Effects of dairy food supplements on bone mineral density in teenage girls. Eur J Nutr 2000;39:256–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cadogan J, Eastell R, Jones N, Barker ME. Milk intake and bone mineral acquisition in adolescent girls: randomized, controlled intervention trial. BMJ 1997;315:1255–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lappe JM, Rafferty KA, Davies KM, Lypaczewski G. Girls on a high-calcium diet gain weight at the same rate as girls on a normal diet: a pilot study. J Am Diet Assoc 2004;104:1361–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Volek JS, Gomez AL, Scheett TP, Sharman MJ, French DN, Rubin MR, Ratamess NA, McGuigan MM, Kraemer WJ. Increasing fluid milk favorably affects bone mineral density responses to resistance training in adolescent boys. J Am Diet Assoc 2003;103:1353–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Du X, Zhu K, Trube A, Zhang Q, Ma G, Hu X, Fraser DR, Greenfield H. School-milk intervention trial enhances growth and bone mineral accretion in Chinese girls aged 10-12 years in Beijing. Br J Nutr 2004;92:159–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lau EM, Lynn H, Chan YH, Lau W, Woo J. Benefits of milk powder supplementation on bone accretion in Chinese children. Osteoporos Int 2004;15:654–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chan G, McNaught T. The effects of dairy products on children’s body fat. J Am Coll Nutr 2001;20:577 (abstr). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lanou AJ, Barnard ND. Dairy and weight loss hypothesis: an evaluation of the clinical trials. Nutr Rev 2008;66:272–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Summerbell CD, Watts C, Higgins JP, Garrow JS. Randomized controlled trial of novel, simple, and well supervised weight reducing diets in outpatients. BMJ 1998;317:1487–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zemel MB, Thompson W, Milstead A, Morris K, Campbell P. Calcium and dairy acceleration of weight and fat loss during energy restriction in obese adults. Obes Res 2004;12:582–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zemel MB, Richards J, Mathis S, Milstead A, Gebhardt L, Silva E. Dairy augmentation of total and central fat loss in obese subjects. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:391–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zemel MB, Richards J, Milstead A, Campbell P. Effects of calcium and dairy on body composition and weight loss in African-American adults. Obes Res 2005;13:1218–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thompson WG, Rostad Holdman N, Janzow DJ, Slezak JM, Morris KL, Zemel MB. Effect of energy-reduced diets high in dairy products and fiber on weight loss in obese adults. Obes Res 2005;13:1344–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bowen J, Noakes M, Clifton PM. Effect of calcium and dairy foods in high protein, energy-restricted diets on weight loss and metabolic parameters in overweight adults. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:957–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harvey-Berino J, Gold BC, Lauber R, Starinski A. The impact of calcium and dairy product consumption on weight loss. Obes Res 2005;13:1720–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wagner G, Kindrick S, Hertzler S, DiSilvestro RA. Effects of various forms of calcium on body weight and bone turnover markers in women participating in a weight loss program. J Am Coll Nutr 2007;26:456–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Major GC, Alarie F, Dore J, Phouttama S, Tremblay A. Supplementation with calcium + vitamin D enhances the beneficial effect of weight loss on plasma lipid and lipoprotein concentrations. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:54–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bailey DA, Martin A, McKay H, Whiting S, Mirwald R. Calcium accretion in girls and boys during puberty: a longitudinal analysis. J Bone Miner Res 2000;15:2245–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Armas L, Frye C, Heaney R. Effect of cow’s milk on human health. In: Wilson T, Temple N, editors. Beverage impacts on health and nutrition. 2nd ed. Clifton (NJ): Humana Press; 2016. p. 131–50. [Google Scholar]